DECISIONS MADE IN THE FRAME

Rational Choice, Institutional Norms and Public Ethos Against

Corruption in Mauritius

Teodora Heim

Malmö University, Kultur och Samhälle

Leadership and Public Organization: One-year master programme Masters’ Thesis, 15 HP

VT2019

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1. ABSTRACT ... 4

2. INTRODUCTION ... 6

2.1. The purpose of this study and the research questions ... 6

2.2. A short research overview ... 7

2.3. Definitions ... 9

2.3.1. The definition of corruption in this study ... 9

2.3.2. The definitions of the public officers ... 10

2.4. Disposition of the report ... 10

3. THEORETICAL DISCUSSIONS ... 10

3.1. Rational Choice + New Institutionalism = Rational Choice Institutionalism ... 11

3.2. The public ethos ... 13

3.3. The theory about social construction of the institutional reality ... 15

3.4. A model for the analysis ... 17

4. METHODOLOGICAL CONSIDERATIONS ... 20

4.1. Selection of the departments ... 20

4.2. Selection of the interviewees ... 21

4.3. The documents ... 22

4.4. Delimitations ... 22

5. EMPIRICAL DATA ... 23

5.1. A reasoning about the choice of Mauritius ... 23

5.2. The society ... 25

5.3. The tools of the policy-makers ... 26

5.3.1. The Prevention of Corruption Act (POCA) ... 26

5.3.2. The Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC) ... 27

5.3.3. The Public Service Commission & Disciplined Forces Service Commission (the PSC) . 29 5.4. The public sphere ... 29

5.5. The local governments and their organizational design ... 29

5.5.1. The workflow at the departments ... 30

5.5.2. The control system in the public administration ... 32

5.5.3. Observations from the interviews with the public officers ... 33

6. ANALYSIS AND CONCLUSIONS ... 37

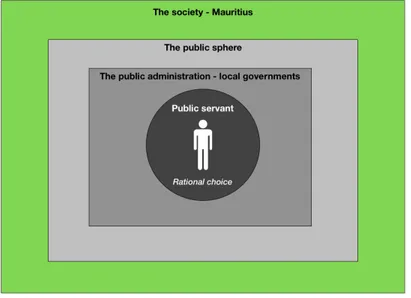

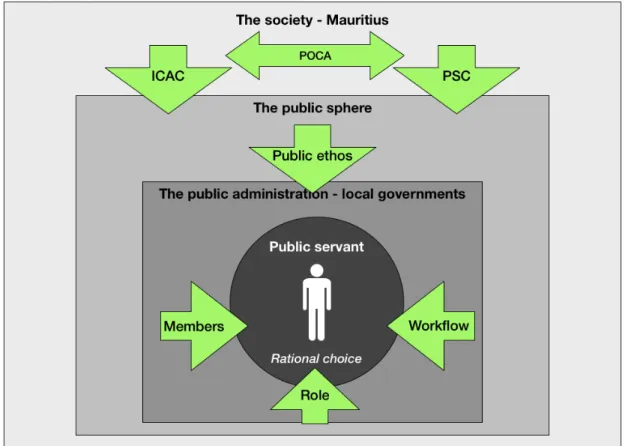

6.1. The layers of the institutional frame ... 37

6.1.1. The society and its influence on the public sphere ... 38

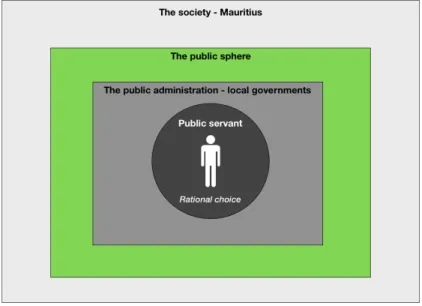

6.1.2. The public sphere and the question if the public ethos is present ... 40

6.1.3. The public administration and its impact on the public servant’s choices ... 42

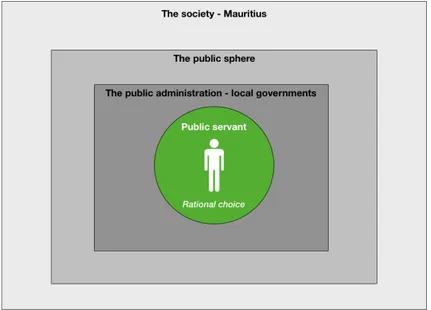

6.2. The individual’s rational calculation and choice ... 46

6.3. What is the role of the public ethos in the rational calculation? ... 48

7. CLOSING DISCUSSIONS ... 51

REFERENCES ... 54

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ... 57

APPENDIX 1 – The Interview Questions ... 58

FIGURES

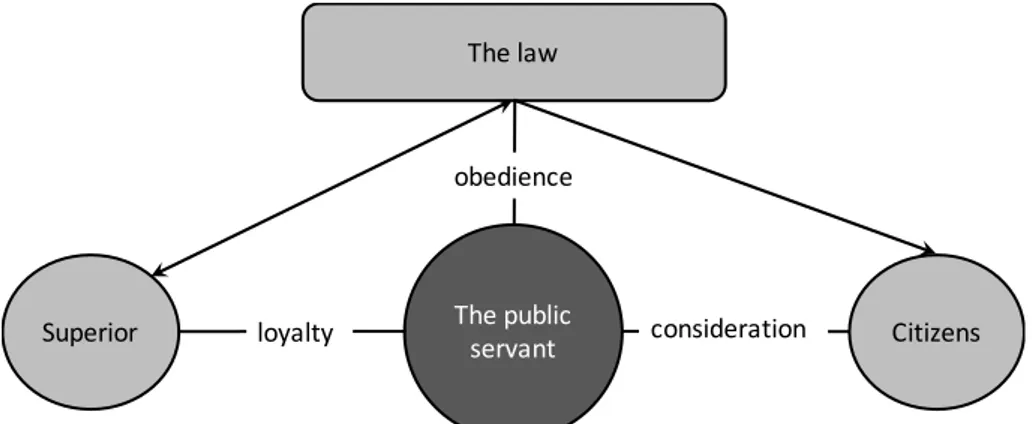

Figure 1: Lundquist's concept of the public ethos (1998:106) ... 14

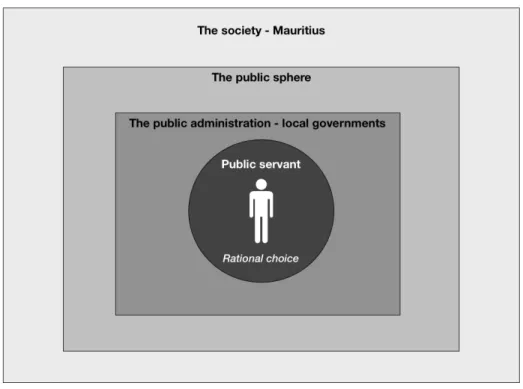

Figure 2: The analysis model ... 18

Figure 3: The analysis model highlighting the layer of the society ... 38

Figure 4: The analysis model highlighting the layer of the public sphere ... 40

Figure 5: The analysis model highlighting the layer of the public administration ... 42

Figure 6: The analysis model showing the influence of the layers on the institutional frame ... 44

Figure 7: The analysis model highlighting the public servant in the institutional frame ... 46

I would like to express my gratitude to the Mauritian team of Transparency International and especially to Mr. Rajen Bablee for the help and support I got when working in Mauritius and during the whole project.

I would also like to thank all the officers at the municipalities in Port Louis and in Rivière du Rempart who took their time to meet me and shared their thoughts. A special thanks to the officers at the ICAC who helped me by sharing their expert knowledge.

1. ABSTRACT

The purpose of this thesis is to increase our knowledge about corruption issues. It examines the connection between the institutional frame and the individual’s choice made in his institutional role. The study is based on the theories of rational choice institutionalism and public ethos and the empirical data is analyzed from a social constructivist perspective. The addressed research questions are:

- How is the institutional frame within the Mauritian public sphere being created, with special focus on shaping the norms saying that corruption is not accepted?

- Does the institutional frame, and specifically the public ethos as a norm, influence the individual’s rational choice when deciding not to act corruptly?

The empirical material has been collected in Mauritius, and the study uses the Mauritian local government as the example for the institution.

According to the theory of rational choice institutionalism, public servants make rational choices, within the frames of the institution. Institutions are to be seen as a wider concept, where both the formal and informal institutions are included, such as norms, institutionalized actions and processes. The public ethos, a norm specifically connected to the democratic, public areas of the society, states that the public servant’s institutional role is different from a private person’s role. According to the theory about the social construction of the reality, the individual’s perception and understanding of his surroundings, the image of his reality, is shaped by the institutional frame and this frame delimits the options to choose among.

The analysis is made with the help of a model which illustrates the layers of the institution, and the individual in the institutional frame, which thereby affects his rational calculations. The model is also used to illustrate the result of the analysis, by showing the factors that influence the norm-shaping process.

The analysis and the conclusions of the study indicate that the creation of the institutional frame is strongly influenced from the society with an anti-corruption agenda, in form of legislation and government agencies, which have a resilient effect on the norm-shaping. Further, the presence of the public ethos norm is shown as an element of the institutional frame. The public servant, when making a rational calculation to decide to act or not to act

corruptly, is situated within this institutional frame. The conclusion of the thesis indicates that the individual’s rational choice is strongly affected by the institutional frame, showing that the public servant does take in consideration the public ethos norms in his institutional role. Even though economic reasons influence how the public servant decides to act, those are reinforced by the institutional norms.

2. INTRODUCTION

Preventing and fighting corruption is one of the Sustainable Development Goals set by the United Nations’ General Assembly in 2015 to be achieved by the year 2030. Goal 16.5 states: ”substantially reduce corruption and bribery in all their forms”1. Anyone you ask would agree that corruption is something unaccepted, unwanted and harmful for the society. But then again, is there a need for one more study about corruption?

2.1. The purpose of this study and the research questions

The aim of this thesis is to increase our knowledge about corruption issues. It will contribute to the research area by examining the connection between the institutional frame and the individuals’ choice made in his institutional role as a public servant. The study is based on the theories of rational choice institutionalism and public ethos and the empirical data is analyzed from a social constructivist perspective. The intention is to explain how the institutional frames and within the frames also the norms are being created and see if the individual’s decision, based on a rational calculation, is influenced by the institutional frame.

This is a qualitative study where the following research questions will be addressed:

• How is the institutional frame within the Mauritian public sphere being created, with

special focus on shaping the norms saying that corruption is not accepted?

• Does the institutional frame, and specifically the public ethos as a norm, influence the

individual’s rational choice when deciding not to act corruptly?

The thesis is completed with the help of a Minor Field Studies scholarship from SIDA (the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency). I spent two months in Mauritius, to carry out the field studies in the period April - May 2019. The study uses Mauritius as an empirical example. The Mauritian society is considered to be the institutional frame wherein the public servant’s rational choice is examined. The institution as a frame has an important role to play when putting the concept of corruption in an organizational perspective.

1 Sustainable Development Goal number 16.5, from the web site https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/peace-justice/

2.2. A short research overview

Studying corruption is a challenging research area. It is demanding, because there is a difficulty in the sensitivity of the question, since corruption is most often an obscure phenomenon, a criminal act. There is also a challenge laying in the complexity and the abstraction of the problem that the researcher needs to handle. Maybe that is the reason why scholars who do research in the corruption field are from so many different research

disciplines such as economics, criminology, law, international relations.

Several studies focus on a principal understanding of the concept of corruption, putting it in the field of political science studies (see for example Rothstein & Varraich 2017). Similarly, many of the studies made about corruption has long time focused on and still do focus on corruption issues at the political level, making connections to and sometimes using corruption as one of the many parameters to explain democratic issues, legitimacy and good governance (Nye 1967, Rose-Ackerman 1999, Rothstein 2011, Rothstein 2012, etc.). Some of the

research within the field aims to highlight the existence of corruption and to explain differences in a particular country or area, for example Berg et al. use the Swedish municipalities, trying to find an explanation for why corruption is more common in some places than in others (Berg et al. 2016). Another interesting, though older, article is Collier’s study (2002). The author aims to find a systematic way to explain the concept of corruption by developing an interdisciplinary theory of the causes of corruption.

Organizational studies as well as the research field within political science has been used to approach the issue from an implementation perspective, where the policy or the policy making process is in focus rather than concept of corruption (see for example Sannerstedt 2001, Hall & Löfgren 2006, Johnston 2012, Winther 2003). Several corruption studies have a normative and constructivist approach, aiming to give advice rather than to explain the context behind corruption (see for example Rose-Ackerman 1999 or several of the

implementation studies mentioned above, trying to analyze possible actions to get the desired result of a policy).

Some studies deal with corruption from an institutional approach. The article of Hoadly and Hatti (2016) puts the problem in a perspective where the norms, including values and

values influence the individual’s rational calculation to condone or condemn corruption. The collection of studies edited by Kubbe & Engelbert (2018) approaches the issue about the social norms which might affect corruption. The articles highlight the impact of the informal rules as an important factor to consider when studying corruption. However, when talking about the norms, the studies do not consider those to be a part of the institutional frame. On the contrary, they are described as an additional ingredient to the mix that had been studied earlier (for example Johnston’s article in Kubbe & Engelbert 2018:15). Therefore, even the social approach, where a social psychological perspective is applied, disregards the norms as a part of the institutional environment. However, the chapters in the book do give a relevant perspective to my study, when stressing the important influence of the informal rules on corruption (Kubbe & Engelbert 2018).

The paper of Erlingsson and Kristinsson studies the connection between public ethos and corruption within an institutional frame, similarly to this thesis. They also use the ideas of Lundquist, and examine how accepted corruption is in low-corrupt countries, by using the public ethos and its ethical standards as an explanation for a lower acceptance for corruption among civil servants than among citizens and also politicians (Erlingsson & Kristinsson 2018:9).

Other relevant studies are presented in the volume of Andersson et al (2010). The articles in the book give both an empirical and a theoretical frame to the studies of the research field. The book covers several perspectives, and illustrates the challenge laying in the complexity of the matter. The authors analyze the connection between the institution and the individual when discussing issues of abuse of power and the issues of legitimacy. The analysis also includes ethical perspectives, mentioning the public ethos as an ethical perspective. When concluding that corruption is per definition an issue that has to be approached by a normative perspective, they also touch the constructivist perspective where the shaping of norms is a part of the reality shaping process (Andersson et al. 2010).

Despite the large number of studies and the multifaceted perspectives used to examine the research field, this short review indicates that there is a lack of studies which analyzes corruption issues with the help of a mix of individual’s rational choice, the public ethos as norm and the institutional frame in a constructivist perspective. This thesis aims also to fill a gap where corruption issues are seen as a part of the institution, affecting the institutional

norms and thereby the decision making of the individual, and also taking ethical aspects in consideration, within the institutional frames.

2.3. Definitions

2.3.1. The definition of corruption in this study

Since corruption is the main topic of this study, there is a need for a discussion about the term. There is not an overall accepted definition of corruption, and among scholars there is an on-going debate about it. The challenge is well illustrated by the following note: “[o]ne sign of

the difficulty of defining corruption is that almost everyone who writes about it first tries to define it” (Jain 2001:73 and 2001:104). There are several papers which aim to discuss the

conflicts in creating a common understanding of the phenomenon and also trying to

summarize the existing definitions (see for example Bautista-Beauchesne & Garzon, 2019, for a recent review or Johnston 2001 for a discussion about some factors that may have an impact on the debate). Andersson et al. devote a whole chapter to the issue, explaining also the inherent normative attribute of the term (Andersson et al. 2010:31-39). A different approach to the challenge is asking the question what the opposite of corruption is (Rothstein 2014).

Transparency International defines corruption as the “abuse of entrusted power for personal

gain”2. The Mauritian Prevention of Corruption Act defines corruption more detailed by listing the acts which are seen as a corruption offence (POCA 2002 Part I § 2).

For the purpose of this research, the definition needs to focus on the role of corruption, since the study will place the concept in the institutional frame and examine the norms connected to corruption within the institution. Corruption is an abstract social phenomenon, and seen from a social constructivist perspective, corruption is a part of the reality that is being shaped. Whether corruption is accepted or not depends on the norm of the society and of the

institution. The interesting thing in this study is therefore not whether one certain act can be considered corrupt or not. What is interesting is rather the actions and reactions of the society connected to corruption. Therefore, in this thesis, corruption is seen as an act, where an

individual in his institutional role choses to abuse his position for a personal gain.

2.3.2. The definitions of the public officers

The public officers mentioned in this study is a common term referring to all employees within the Mauritian public administration. The public servant refers to a person with the duties to handle building applications and inspections at building sites in a Mauritian local government. The public officers called supervisors are the public servants’ managers. The officers in higher positions are called chief executive, chief deputy and chief of department.

2.4. Disposition of the report

The following chapter is going to discuss the choice of the theories and explain both the what the theories say and how they will be used in the study. The chapter concludes by presenting an analysis model. The theoretical discussions are followed by some methodological

considerations, where both the delimitations and the choice of the place and the object of the study will be problematized. All the empirical data is presented in one separate chapter, to clearly show and distinguish it from my discussions and considerations. The analysis and conclusions are presented in the following. In this chapter the answers to the research questions are answered. The report is finished by some putting the result of the study in a context among other corruption studies and by discussing possible further research connected to the issue.

3. THEORETICAL DISCUSSIONS

Theories are used to help the study of the empirical material. Theories can be seen as a kind of glasses that the author has chosen to see the world through. The theories are needed in order to be able to analyze the material in a structured manner.

This study has an inductive approach. Alvesson and Sköldberg (2008:54-55) write that induction involves finding connections in what the collected material shows and based on it find the suitable theory. The theoretical framework for this study has thus been chosen based on the empirical data, with the aim to be able to explain how the institutional frames are being created and how the institutional norms influence the public servant’s behavior.

In many ways, working with an already existing empirical material is a process of creation. The amount of information makes it possible to chose different approaches and to ask

though I had a clear idea from the beginning about the aim to contribute to the knowledge about corruption. However, some observations strongly affected the choice of theories. First of all, every public officer I interviewed said that the reason why they chose not to act corruptly was mainly the fear of the consequences. Secondly, the observations showing that the institution of the ICAC3 had an important role became evident early in the study. Those two empirical evidences led me to the choice of rational choice institutionalism with the aim to study the connection between the institution and the individual’s rational calculation. The table below will highlight how some of the observations led me to the choices of the theories, by showing some examples which in their turn can logically be connected to the theories.

Observations Theories

“I don’t act corruptly, because I am afraid of

loosing my job, I am afraid of the consequences”

(interview 1)

The individual’s rational calculation – rational choices based on a risk assessment.

The ICAC – literary everyone I spoke with mentioned the ICAC.

Institutionalization, creating norms

Public ethos – giving the norm a democratic aspect

“There are some old stories that are told about

officers here at the department, who was caught for corruption. And some colleagues, who have been working here like forever, they tell us what happened, they lost their jobs and they can never get a new job within a public office again”

(interview 4)

Socialization, shaping the norms

In the following the theories about rational choice institutionalism, about the public ethos, and about the social construction of reality are described, and their relevance to this study is explained.

3.1. Rational Choice + New Institutionalism = Rational Choice Institutionalism

The core of the rational choice institutionalism is the hybrid of the basic assumptions of the two theories, rational choice and new institutionalism. This theory “examines the extent to

which institutions might provide solutions to collective action problems and, more generally, the institutional context-dependence of rationality” (Hay 2002:13).

When talking about institutions in the rational choice institutionalism, the definition of the ‘institution’ is in line with the new institutional ideas. Therefore, it refers to a wider concept, where both the formal and informal institutions are included, such as norms, institutionalized actions and processes (Hay 2002:7 ff). As March and Olsen explain, within institutional theory “[a]n institution is a relatively enduring collection of rules and organized practices,

embedded in structures of meaning and resources” (March & Olsen 2005:3). There are two

important assumptions made in the institutional perspective: the first is that institutions create order and predictability and the second is that there are routines for the interaction between the individuals and the institutions that translate the structures into actions and vice versa, the individuals’ actions into institutional continuity (or change). The theory has its focus on the institution and its structures, norms rather than on the individual’s actions and therefore, it needs a supplement. One alternative to complement the perspective is by including the rational choice (or rational actor) theory (March & Olsen 2005:5).

Rational choice theory assumes that “individuals are rational and behave as if they engage in

a cost-benefit analysis of each and every choice available to them before plumping for the option most likely to maximise their material self-interest. They behave rationally, maximising personal utility net of cost while giving little or no consideration to the consequences, for others, of their behaviour” (Hay 2002:8). When adding institutionalism to the theory, it will

lead to the statement that the individual’s choices are influenced by the institutional

environment. The frame is important for the individual’s choice, since it affects the possible alternatives to chose among and to evaluate. For example, the punishment for breaking the law is one of the parameters that has to be taken into account when rationally calculating the cost of committing a crime. The institution seen as the rules of the society also gives a frame to the individual’s private life, adding social effects to the decision making in form of for example shame if convicted for a crime.

The rational choice in this study is going to be simplified to include two choices – to act or not to act corruptly. This delimitation is made to be able to focus on the structure of the choice and on the external input that affect the choice rather than on the possible options to chose among. In the reality, there are of course much more possibilities and aspects to

consider. However, this study is going to focus on the one where the public servant chooses not to act corruptly. This will simply be put in opposite to the choice to act corruptly. Not least since the definition of corruption is problematic, I am going to disregard all other possibilities. Also, when discussing the calculation and the choice of the public servant, it should be noted that the calculation is more a theoretical explanation than a conscious act of the public servant. The calculation might not be made on a paper or even in the head of the individuals as a planned act. It is only a way to explain how the components that this study analysis affect the outcome.

The rational choice institutionalism, where both the institutional frame and the individuals’ choices related to those frames are taken into account, complement each other and thereby it supplements what critics mean are needed in both theories. New institutional theories are criticized for not taking in consideration the individuals’ actions and rational choice theories lacking in taking in consideration that the individual can not be seen as “free” from his environment and from its context (March & Olsen 2005:4).

In this study I accept and use the statements of the rational choice institutionalism, by making the assumption that the individuals’ choices are determined by the institutional frame, since the institution decides the possible options for the choices. The individual does a rational calculation but the calculation can only take into account options that are defined by the institutional frames.

3.2. The public ethos

The public ethos is a concept introduced by Swedish scholar Lennart Lundquist. I am going to rely on the studies of Lundquist concerning public servants explained in his basic work

“Demokratins väktare” (“The guard of the democracy”) (Lundquist 1998). It has to be noted that Lundquist’s studies are made in a Swedish context, however, since the basic idea of how democracy works and democratic values are universal, the reflections are applicable in any democratic society.

The concept of public ethos can be described as the society’s expectations on the public administration. The public servant’s role is different from an officers’ role in the private sector, since the public sector relies on democratic values (Lundquist 1998:18). The

democratic dimension and values are added to the economical values (which are relevant for all social sectors) (Lundquist 1998:63):

Democratic values Economical values Political democracy Legal certainty Public ethics Functional rationality Cost efficiency Productivity

Both the democratic and the economical values have to be taken into account within the public administration. Therefore, the public servant’s role includes different ethical relations: he has to obey the law, has to be loyal to his supervisors and to his organization and has to show consideration to the citizens whom he serves. The relations are explained in the following picture (Lundquist 1998:106, my translation):

Figure 1: Lundquist's concept of the public ethos (1998:106)

The described ethical relations introduce a moral dimension into the public servant’s actions, since he needs to take into account values that can be, and in many cases are, contradictory. Therefore, when the public servant fulfills his duties, there are ethical dilemmas present. An illustrative example is the case where Nazi servants were loyal to their superiors by following their orders and killing millions of Jews. However, it is impossible to agree that they did the right thing, since their actions did not take in considerations the citizens’ needs and rights. When they blindly followed their loyalty towards their superiors they disregarded the ethical relation towards the citizens. The example illustrates well how a public servant needs to balance his decisions and why this balance needs to include the democratic values.

The public ethos has a ground in the existence of a public common will, with its roots in Aristotle’s philosophy. The public ethos is related to a higher level than the individual person

The law

Superior loyalty The public servant consideration Citizens obedience

who has the role of a public servant (Lundquist 1998:32 ff). This leads to a normative perspective, where certain ethical values are accepted and others are not. The common good becomes important within the society, and a public servant needs to take this perspective in account.

3.3. The theory about social construction of the institutional reality

The above presented theories say that the public servants’ rational calculation is made within the institutional frame and it is influenced by the institutionalized norms, including the public ethos. Berger and Luckmann’s theory (1967) about the social construction of the reality is a theory explaining the process where the institutional frame is being created.

Berger and Luckmann explain how individuals learn and accept norms and by this process create them at the same time. Their assumption is that the social order is being created by individuals: “social order is a human product, or, more precisely, an ongoing human

production” (1967:70). The process is explained as steps. First of all, all human activity is

subject to habitualization (or repetition). Those habitualized actions become institutions (Berger & Luckmann 1967:70-72), just as it became accepted in new institutional theories later on. And those institutions, “by the very fact of their existence, control human conduct by

setting up predefined patterns of conduct, which channel it in one direction as against the many other directions that would theoretically be possible” (1967:72). This means that the

institutions give the individual the possible choices to choose among. And therefore, the individual experience this institution as an objective reality, knowing no other possible ways to act (1967:77). Thereby the institution not only gives options, it also delimits the possible options, just as it is explained when talking about the new institutional theory above.

This reality of the social world has to be re-shaped and re-produced from generation to generation, from individual to individual to persist: “the reality of the social world gains in

massivity in the course of its transmission” (1967:79). So far Berger and Luckmann explain

what social constructivist theories explain. However, they also go further when explaining how the individual is being taught to accept the norms. Very simplified, the process can be described be the following steps: The first is the institutionalization, described as the step where child learns and forms his self, through his environment. This person, formed after the

environment, not only accepts the way of being but also becomes a part of this environment and institution and this reality becomes objectified or self-evident (1967:65 ff).

The second step is the legitimation, when the conduct of being that is objectified is put in the institutional frame: “[l]egitimation justifies the institutional order by giving a normative

dignity to its practical imperatives” (1967:111). Where the way of acting was just learned by

the individual before, now it becomes the right or the wrong way to act.

Step three in the process is the internalization of the reality. As Berger and Luckmann show, the internalization is a necessary step where the individual’s reality (which has been created and legitimated) gets a social aspect: “internalization […] is the basis, first, for an

understanding of one's fellowmen and, second, for the apprehension of the world as a

meaningful and social reality” (1967:150). It means that the individual will accept and play a

role in the society, by reflecting the attitudes of others and he becomes what he is seen and recognized by the other members of the society. Therefore, it can be seen as a primary socialization, that “internalizes a reality apprehended as inevitable” (1967:167).

The final step in constructing the reality is what the authors call for secondary socialization or internalization. The secondary socialization is where the common knowledge becomes

impersonal, detached from the individual performers. The role-specific knowledge gets common, and a person becomes his role in the society (1967:157 ff). An illustrative example is how a horseman as a concept gets attributes: the “process of internalization entails

subjective identification with the role and its appropriate norms - ' I am a horseman', 'A horseman never lets the enemy see the tail of his mount'” (1967:159).

The theory explains thus that the institutional reality is something that is taught and the first step of the process is when the individual learns a certain behavior. Later the individual understands that the behavior is general and not only applicable on one situation. Thereby, the behavior gets socialized, and when it is accepted by the members of the institution, it gets internalized – it becomes the norm (1966:152-153).

The theory lays on the assumption that learning is the key for creating the norms and the institution itself. At the individual level (within the family) this is the primary socialization and at the social (institutional) level it is the internalization process (1966:149 ff). The

analysis of this study will focus on the process within the institutional level, the public sphere – the secondary socialization or the internalization process.

Just as Berger and Luckmann, also Lundquist notes that the actors in a process act in a social context that is based on construction of ideas (Lundquist 1998:135 ff). Thus, the three theories presented above, about the rational choice institutionalism, the theory on social construction of reality and the theory about the public ethos are all connected and complement each other: the public ethos is seen as one of the norms in the institutional frame, within which

individuals are institutionalized and make rational choices. However, the possible choices are limited by the institutional environment, by defining what options there are to choose among.

3.4. A model for the analysis

With the help of the theories, the analysis will process the empirical material to show and to explain how the institutional frame is being created and how the institutional norms influence the individual’s rational calculation. The aim of the analysis is thus to put the empirical data within the theoretical frame to be able to answer the research questions. To do this, an analysis model is devised for a structural study of the institution and of the individual in his institutional frame. The model is used when the observations are explained from a social constructivist perspective.

The analysis model describes the public servant’s position within the institution, which is his institutional reality. It also shows how the institution’s different layers are seen in the

analysis. Putting the public servant in the center, the model gives a tool to explain how his rational choices are influenced by the institutional frame:

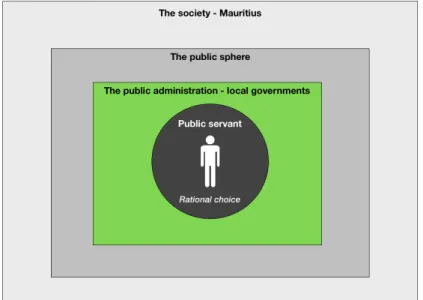

Figure 2: The analysis model

• The institutional frame

The institutional frame in the model consists of different layers to describe the

individual’s environment in a structured way. In the picture, those are symbolized by the squares in different shades around the public servant.

- The country of Mauritius is the society in the model.

- The society includes a public sphere. The public sphere is defined as the part of the society that relies on democratic values (see Lundquist’s theory described in chapter 3.2). - The public sphere includes the public administrations, in this study the local

governments in Mauritius are used as example, more precisely the departments of land use and planning in two different locations in Mauritius.

- The public servant is placed in the institutional frame. The public administration is the physical workplace of the public servant, his visible environment.

• The individual’s rational choice and the components of the calculation

- The public servant, when deciding to act or not to act corruptly, makes a rational choice, a calculation where he takes in consideration the possible wins and the possible costs for his action.

- However, the possible options to choose among in this calculation are determined by the individual’s institutional reality, including the institutional norms. The norms are both

including and excluding: they make a certain behavior desirable but at the same time they also make it impossible to imagine, or at least will strongly question, all other kinds of behavior. Thereby, the institutional defines gives the components of the individual’s rational choice.

The analysis model uses the concept of institution in a wider perspective, where both the formal and informal institutions are included, such as norms, institutionalized actions and processes.

A model is always a simplification of a complex reality. My model simplifies by excluding many elements of the society, such as religious beliefs, ethnical aspects, cultural and traditional values. The model also disregards from taking the public opinion in form of political elections as well as the important role of the media in consideration. All those elements are seen in the model as part of the social norms in the private sphere.

The model uses Lundquist’s idea, when simply complementing the private sphere with the public sphere in the institution, by adding the democratic values (for references, see chapter 3.2 where the theories about public ethos is described). However, this division between private and public could be seen as problematic, since there is not a clear border between the two. The two interact and this interaction can for example be evident when a private person is a part in a corrupt act, being the one who is offering the bribe or the gift to a public servant. However, to explain the public servant’s rational choice, the private person and his act is in this example would simply be seen as the “win” of the action in the rational calculation in the model.

Also, the model disregards the surroundings of Mauritius: the African continent or the entire world, even though one has to be aware of the fact that other countries and international organizations do affect the Mauritian society, for example by giving a strong incitement for choosing to make efforts to prevent and to fight corruption.

4. METHODOLOGICAL CONSIDERATIONS

To collect the empirical material, I used document studies and semi structured interviews. The interviews were conducted in Mauritius during the period April – May 2019.

As described above, this study has an inductive approach where the theories have been chosen based on the empirical data, with the aim to be able to explain how the institutional frames are being created and how the institutional norms influence the public servant’s behavior

(Alvesson and Sköldberg 2008:54-55).

Andersson et al. states that corruption studies necessarily have a normative approach. As they explain, this is because of the nature of the topic: the definition of corruption relies on the assumption that there is a correct way to act (2010:36 ff). They mean that corruption basically is an ethical issue, which leads to the question how we can define what is correct or not (Andersson et al. 2010:38). Therefore, when it comes to corruption studies, it is per definition a normative problem since the definition of corruption can be seen as defining the right way and the aim of the society is to control the public servants’ behavior in a certain way. This normative approach is also the way into the deeper parts of the research area, where the creation of the norms is being studied. However, the conclusions of this study are not to be considered as normative results. The focus is rather on explaining the creation of the

institutional norm which condemns corruption than to discuss if corruption is harmful for the society or not.

To analyze the empirical data, the above described analysis model is used. The model relies on the theories and as well as be seen as a methodological tool, it is also a model for a practical use of the chosen theories and perspective.

4.1. Selection of the departments

When selecting a department for the purpose of this study in the local governments in Mauritius, it was based on the idea about finding situations where public servants face situations where corruption issues can be present and therefore needs to be handled.

Therefore, I looked for a department where public servants meet citizens directly, and where the citizens can be in a depending situation. Discussions with the officers at ICAC and with the executive director at Transparency International led me to choose between the department for land use and planning or the health department, where licenses are being issued for

option, since it would involve citizens in their professional sphere, which at the end could affect the relationship between the applicant and the institution of public administration.

4.2. Selection of the interviewees

The choice of the public servants who have been interviewed was mainly made by the supervisors. Both with respect to the work situation and in lack of knowledge about the staff at the departments it could be considered as a random selection. There can of course be

discussed some ethical issues, and the question can be posed if the chosen persons can be seen to represent a certain interest or a certain opinion. However, the number of interviewees is a significant part of the total number of public servants at the studied departments. They should be considered as a selection that represents the individual's perspective - they represent the officials but should not be considered as a representative sample for all public servants.

Totally five public servants were interviewed from the local government in Port Louis and three public servants from Rivière du Rempart. In Port Louis the supervisor of the public servants was interviewed, as well as the head of department. In Mapou the head of department is also the direct supervisor of the public servants. I had the possibility to conduct interviews with the chief executive of the local government in Rivière du Rempart and the chief deputy of the local government in Port Louis. The internal auditor as well as the responsible external auditor of the local government in Port Louis was interviewed.

I conducted interviews with the officers at the ICAC on two occasions. The first occasion was the first interview of the study, with the aim to get help with orientation and to find the

possible options for the choice of the local governments and departments. IT also had the aim to get a basic knowledge about the corruption situation in the country. The second occasion was in the end of my data collection, where I presented my observations and got an informal discussion about both the quality of the data and about the possible conclusions.

The executive director of Transparency International in Mauritius gave me several

opportunities for discussions about the subject, and also contributed to the empirical material by written comments.

All interviews were conducted personally. The interviews were conducted as semi-structured interviews, where the same questions were discussed with all the interviewees. The questions were more used as guidelines for the discussion than yes-no options. A list of the interview questions is in appendix 1.

The interviewees had the possibilities to explain certain issues and when needed also to develop their answers. I also had the opportunity to ask additional questions to follow up the answers and to get a deeper understanding. The interviewees also had the opportunity to chose not to answer any of the questions.

4.3. The documents

The study involves examination of some documents, mainly the law text from the relevant legislation, such as the POCA and information from the authorities. Publications from the ICAC and policy documents from the local governments were also studied. Also information published at the official web sites of the authorities were studied.

4.4. Delimitations

Within the frame of this study, besides the ones which are already described above, some additional delimitations had to be made to be able to get a deeper rather than wider understanding of the research area. The study is based on empirical data collected in Mauritius in March-April 2019. The local governments in Port Louis and in Rivière du Rempart (with office in the city of Mapou), more specifically both their departments for land use and planning, were studied.

There is an important difference between political and administrative corruption, because they concern different procedures: one where the policy is made and one where the policy is

implemented (Andersson et al. 2010:37). The policy making process itself is an important part of how the norms are created. However, this study is delimited to corruption issues at the administrative level and will not include any discussions about corruption issues at the

political level. This delimitation is made because there is a need for a defined and demarcated research environment. Therefore, the anti-corruption legislation as such is not going to be discussed, neither will I discuss the policy making process on the political level. The fact that

there is a wish from the political leadership to prevent and to fight corruption is simply accepted.

5. EMPIRICAL DATA

This chapter describes my observations made during the study. The word “observation” is not to be confused with the scientific method of observation. Observation is used in this thesis as a substantive, a synonym for the collected material, the empirical data.

The chapter starts by a discussion about the choice of Mauritius as the institutional frame. Thereafter the chapter describes the background of the study, by giving a general picture of the Mauritian society. This section starts with some information about the “outer frame” in form of the surroundings which are not a part of the analysis, however, some knowledge about it is necessary for the understanding of the analysis. It is followed by the observations made about the tools used by the society to influence the public sphere. This section is mainly based on the document studies and on the interviews made with the officers at the ICAC, with the Executive Director of Transparency International in Mauritius and with the Chief Deputy and the Chief Executive in the local governments and also the observations from the

interviews made with the internal and the external auditors. The next section describes the observations made about the public sphere, including the organization of the local

governments involved in this study. Finally, the chapter depicts the observations made during the interviews conducted with both the public servants and with the supervisors, with more focus on the individual’s perspective.

5.1. A reasoning about the choice of Mauritius

Why choose Mauritius for a corruption study? Mauritius is a country in Sub Saharan Africa with a comparatively low grade of corruption. According to Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index from 20184, Mauritius scores 51 at the CPI-index and ranks number 56 (approximately like Slovakia and Italy in Europe). To put it in a more local context, out of the 49 countries in Sub Saharan Africa only 6 scores over 50 in the index and in this group Mauritius is number 6. At the same time, the countries with the lowest scores are from the same area, such as Somalia and Sudan. The following table shows the scores and the

ranks of Mauritius in the CPI the last six years (the number of countries that were measured is shown within the parenthesis.)

Last Six Years of Corruption Perception Index Year Mauritius’ Score Mauritius’ World Rank

2013 52 52 (175) 2014 54 48 (174) 2015 53 45 (167) 2016 54 50 (176) 2017 50 54 (180) 2018 51 56 (180)

One could ask if a good example is necessary for this study, given the research questions. I argue that it is, even though the study as such, as well as the analysis model, can be applied for a case study in other institutional environments. However, to be able to show that the existence of the public ethos does have an impact on the individual’s rational calculation, it is necessary to prove by showing its presence before a possible hypothesis about the opposite can be tested.

But is Mauritius a good example? This statement was questioned already on my way from the airport. Just mentioning the word “corruption” makes Mauritians talk about all the scandals in the country, where politicians in high positions got involved in bribery. When trying to

explain that this study concerned the administrative level, I still got some skeptical comments.

Therefore, my first question to my interviewees, the experts at the ICAC and at Transparency International, was what they consider being the correct picture. Their answers, as well as many other observations I made among Mauritian people, indicates that there is not a simple answer. Corruption is a complex phenomenon – and it is probably simplifying and misleading to phrase the question whether Mauritius is a corrupt country.

During my time in Mauritius I did not meet anyone who admitted knowing about an actual recent corruption case at the administrative level. One could clearly argue that it is just as expected, since nobody would admit a crime to me. And that is, of course, true. However, all

deeper discussions did lead to the conclusion that with corruption they meant something that occurred at the political level.

A recently published report5 also supports my statement, meaning that “Mauritians benefit

from some integrity in public institutions and some very effective anti-corruption strategies”.

However, the authors also point out some serious scandals at high political level, that did not lead to proper actions. That can explain why “Mauritians still see institutions and groups like

parliamentarians, the police and the prime minister as corrupt” and why Mauritians have a

negative attitude when talking about problem with corruption in their country. Further, several studies made on corruption in Mauritius highlight the country’s success, often with focus on the country’s economical development (for example Frankel 2016). Connecting the

economical situation to corruption issues can explain many factors, which are relevant also in an institutional perspective.

Also, everybody I talked with did agree that Mauritius has made immense progress in

preventing corruption. Putting the question in that perspective, when comparing the situation both with the past but also with other countries, also Mauritians consider their country to be a good example. Therefore, taking all aspects into consideration, I make the assessment that Mauritius should be considered a good example and therefore is a suitable case for this thesis.

5.2. The society

To understand the institutional reality of the public servants it is necessary to have some knowledge about the country of Mauritius. Even if the study does not aim to analyze the society as such, it is relevant in some aspects to highlight the impact of the general situation.

Mauritius is an island state, situated in the Indian Ocean, East from Madagascar. Mauritius is a constitutional democracy and got its independence in 1968. The country is concerned to be a stabile democratic state, with free elections. Being an island, Mauritius has no natural

neighbors and a delimited areal, which leads to strong personal relations and also to strong pressure from the society. Historically, the Mauritian territory was colonized first by the Dutch, later by the French and finally by the British. This heritage resulted in a mix of

5 The report was published by Transparency International on July 11th 2019:

ethnicities and religions. People with Indian, African, Chinese and European roots living together in a delimited area. This can lead to a strong feeling for the own group, and also to contradictions between the groups. As one of my interviewees explained

“it may be argued that the country suffers from a lack of discipline which, in turn, opens space for unethical thoughts and actions. It is a situation which is prone to a culture of corruption and is linked, in some way, to our insularity and our mostly Asian and African origins.”

It is clear that Mauritians themselves do see some challenges in preventing and fighting corruption in their country. However, the political leadership shows a strong motivation for preventing corruption, even though many Mauritians do not think it is enough. The political will to prevent corruption is most visible in the legislation (the POCA). Other examples are the Code of Ethics for Public Officers6 or the many booklets and guidelines published by the

ICAC7.

Mauritius is a constitutional republic with three tiers of government: central, local and village. Local government in Mauritius is legislated by the Local Government Act from 2011. Local government on the island is divided into urban and rural authorities. In the urban areas there is the city council of Port Louis (the capital), and there are four municipal councils. In the rural areas there are seven district councils and 130 village councils8. The political level of the Mauritian local governments is appointed by free elections. The administration of the local governments has executional duties.

5.3. The tools of the policy-makers

5.3.1. The Prevention of Corruption Act (POCA)

The Prevention of Corruption Act from 2002 is a legislative that makes corruption illegal in Mauritius. The Act is very detailed and defines point by point which actions should be considered corruption.

The legislation makes it illegal both to take or to offer a bribe or any other gratification. Thus, also the person who tries to offer a gratification can be punished (POCA 2002 Part II § 14):

6 Published in 2016 by the Ministry of Civil Service & Administrative Reforms.

7 The publications can be found at the homepage https://www.icac.mu/publications/ (last visited 2019-07-23). 8 According to the Commonwealth Local Government Forum,

“Any person who, while having dealings with a public body, offers a

gratification to a public official who is a member, director or employee of that public body shall commit an offence and shall, on conviction, be liable to penal servitude for a term not exceeding 10 years.”

The POCA stipulates that there shall be a national anti-corruption authority:

“There is established for the purposes of this Act a Commission which shall be known as the Independent Commission Against Corruption” (POCA 2002 Part II § 1).

5.3.2. The Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC)

The Commission’s duties are stipulated in the Act and include both the prevention and the investigation of corruption. Therefore, the ICAC consists of two main branches: the one for the prevention, where the focus is on education, information and co-operation with public organizations to help them in their work with corruption prevention; the other one is the controlling area, where suspected corruption cases are being investigated.

The branch for prevention works by issuing guidelines, best practice guides and codes of conduct for public servants. They also issue general guidance, both via their home page and via other communication channels, such as booklets, advertisements, etc. The ICAC is visible in public organizations and in several cases I did notice information about corruption issues in public locations, issued by the ICAC. It can be a question of posters hung up on the walls, informing about the hot-line where anyone can report corruption or about the simple fact that corruption is illegal. According to the officers I met at the ICAC, the ICAC also works with information campaigns in schools and universities, both for students and teachers, with the aim to bring conciseness about corruption issues among young people.

The ICAC also helps public organizations, among them local governments, by conducting corruption prevention reviews. The idea is to study the organization systematically, to revel weaknesses concerned corruption issues. It can be for example the design of work processes, or of the existing control mechanisms. According to one of the officers at ICAC, the emphasis is on corruption issues when conducting those reviews. The review is made in co-operation between the organization’s leadership and the ICAC and it results in a report, which includes

recommendations for the organization to help them achieve a better performance in corruption prevention.

The work done by the ICAC in regard of information and education about corruption issues has to be considered as successful, since all the interviewees were aware about ICAC and its role and they were all very aware of and showed high competence about corruption issues. Also, other Mauritians I met in everyday life did show understanding and interest for corruption issues, and also asked questions about my study showing awareness in these issues.

The other branch of the ICAC works with investigation of corruption cases. The ICAC is the authority with the responsibility for maintaining a whistle blower function where anyone can report a corruption case. According to the ICAC’s web page there are several possibilities to do so:

“To report a case of corruption, you can: 1. Come to the ICAC in person to report the case to ICAC officers; 2. Write to the Commission by email or by using this form9. If you choose to report in writing, you can do so without disclosing your identity, or by giving your name, address etc.; 3. Phone us at 402-6600 or on our Hotline number 142” (from the ICAC’s website

www.icac.mu).

It should be noted that the legislation makes it obligatory for public officers to report corruption cases to the ICAC:

“Where an officer of a public body suspects that an act of corruption has been committed within or in relation to that public body, he shall forthwith make a written report to the Commission” (POCA 2002, Part V § 44).

Also the ICAC itself can start an investigation if it becomes aware that a corruption offence or a money laundering offence may have been committed.

According to the interviews conducted with the officers at the ICAC, there are about 1800 cases reported yearly. Many of the cases are not relevant or leave too little information to

carry on an investigation. Yearly, there is a dozens of investigations that lead to prosecution and some convictions occur annually.

In this connection it has to be mentioned that there is also some criticism of the ICAC. One of my interviewees pointed out that the Commission’s Board members, including the Director General, are all political nominees. This question, however, is out of the limit of this study, since the policy is not being the subject of the study.

5.3.3. The Public Service Commission & Disciplined Forces Service Commission (the PSC)

All public officers are recruited by a central authority, the Public Service Commission & Disciplined Forces Service Commission. All vacancies are reported to the Commission who advertises those publicly and carries out the recruitment process. The public servants are appointed by the Commission. The idea is to keep an open competition about nominations and, through this transparent process, make sure that the risk for nepotism is minimized.

5.4. The public sphere

The definition of the public sphere in this essay is based on the public ethos theory. The word ‘public’ refers to the common within the society, which relies on democratic values. It

includes the democratic institutions, and thus also the local governments and their administrations, which are involved in the study.

Some sections of the society described in the section above can also be considered to be a part of this public sphere. The political level, and thereby also the policy-makers’ tools which affect the public sphere, are within the limits for the definition. However, since the study has its focus on the institutional norms within the public administration, the following section is going to focus on the local governments.

5.5. The local governments and their organizational design

The administrative bodies of the local governments are hierarchical, with a strong

management at the top. The local governments in this study are led by a Chief Executive and by a Chief Deputy. The organizations are divided into departments with different areas of responsibilities. The departments are led by a department chief. When talking with the public

servants it is obvious that they do consider the hierarchy being leading in their actions, meaning for example that any discrepancy and conflict should be reported to the supervisor:

“If I had gotten suspicion about a colleague acting corruptly, I would go to my boss and report it […] was it my boss who did something wrong, I would go to his boss” (from several interviews with public servants in both Port Louis and in Rivière du Rempart).

Also, when I visited the higher officers, they were very formal meetings. I reported my arrival to the secretary, who, after a short wait, showed me to the officer’s room. The higher

managers’ rooms are spacious with large desks, signaling authority.

When talking with the public servants about their picture of how they are being supervised and monitored at their work, some mentioned that

“of course my boss sometimes comes and asks what I am doing and that it would really not be good if I did not do my work” (from interview no 3).

However, the supervisors said they had an “open-door-approach”, where the public servants have the opportunity to enter and discuss work related issues. Both the public servants and the supervisors affirmed having an open and collegial climate at the office.

5.5.1. The workflow at the departments

The work processes included in this study concern applications for buildings and inspections at building sites. Applications are required to build a new building at a land or to make major changes in existing buildings. The process is initiated by the citizen who wants to erect a building on his mark or make a major change. It should be noted that all procedures in public administration in Mauritius are regulated centrally, either by the legislation or by

implementing the same solution everywhere, giving no space for varieties.

The Assistant Officers handle incoming applications. Lately a new procedure has been introduced, where most of the applications are submitted on-line. The change was made to facilitate for the applicants and also to make it possible to have an overview of their

application. However, it also ensures that officers no longer face situations where they meet citizens in person when handling an application. This process does not exclude all personal

contact though, since officers are still available to help applicants filling out the application form and to explain the documents to be attached to the application. The on-line system also ensures that all applications are being documented and all work done with the application is logged. In the log it is possible to see who did any changes, when and what the change was. Also, when a change is made to an application, it is no longer possible to reverse the process. When an officer for example checks that all necessary documents are attached and sends the case further to his supervisor, this message is being logged and can no longer be called back.

When handling an application, there are always several officers involved in the process. The routine is that every public servant has a special task to complete and than the application is being sent to the next person. The last person in the chain is the chief of the department.

All applications sent for the decision of the committee. The committee is the political organ that makes the decisions to approve or reject the application. The departments leave a

recommendation to the committee, however, the committee, being a political organ, can make a decision that differs from the recommendation.

There is still a direct contact between the public servants and the citizens when inspections are made at building sites. Inspections are made to control that the erected buildings comply with the submitted drawings of the permit or, when there are some suspicions about a

construction being illegally built. According to my interviewees, normally there is more than one officer visiting the sites, for security reasons but also to avoid situations where an

inspector would face a citizen alone.

Routines to handle situations where conflicts of interest can be present are usually considered to be important for preventing corruption. Example on conflict of interest is when an officer would handle an application of a family member. ICAC released an information booklet in 2014 with the title “Managing Conflict of Interest”, where recommendations are made for routines to handle those situations. At the departments chosen for the study I asked about those routines and according to the supervisors there were clear procedures. However, when asking the public servants only a few of the interviewees had knowledge about the routines and procedures to follow. Though all the interviewees did state that they would try to avoid such a situation, by informing their supervisor about it.

5.5.2. The control system in the public administration

Basically, within all kinds of organizations, it is considered to be a need for a control system for ensuring compliance with legislation and rules and for achieving an efficient operation. Control systems can be designed in many ways. However, most commonly there is an external auditor, who independently reviews the finances and the compliance with the regulation, and an internal control system.

Internal control is a process aiming to assure an organization's efficiency, reliable financial reporting, and compliance with laws, regulations and policies. The implementation of an internal control system according to internationally accepted standards is considered to be one of the key factors to prevent and to fight corruption10.

Local governments in Mauritius have an internal auditor. When interviewing the internal auditor in Port Louis, we discussed issues concerning corruption control. She did stress that the

“main objective of the internal auditor is to ensure transparency”.

The internal auditor has focus on both operational and financial questions. However, when we discussed the departments for land use and planning, she had no example of any control to prevent corruption, but rather described the internal auditor’s work as

“verifying files, that payment […] is right”.

When discussing internal control system, and for example risk assessment (which is one of the basic processes), the observations show that there is no such procedure in place. However, the internal auditor did mention this as a future project. When discussing the internal auditors’ role with the officers at the ICAC, their opinion is that

“the internal auditor in the municipality does not go that deep, their focus is on the financial aspects”,

a statement that was confirmed by the interview with the internal auditor in Port Louis.

All public bodies in Mauritius shall have an external auditor according to the law. The external auditors are an independent body, reporting directly to the political leaders of the municipality and to the Parliament. My interview with the external auditor of the municipality

of Port Louis aimed to get information about the controls made concerning corruption and about the recommendations given by the auditors. Even though there is a client

confidentiality, I got some general information from the chief auditor that is of interest in this study. First of all, auditing is made according to international standards. This includes a check of the control environment to make sure there are sufficient procedures in place to be able to detect irregularities. The auditor did confirm that a recommendation was left to the

municipality to strengthen the internal control system, by encouraging them to have proper processes at place. At the same time, the external auditor did point out the whistler-blower service at the ICAC, where anybody can report any suspicion about corruption, to be one of the best solutions to prevent and to fight corruption.

When interviewing the Chief Deputy in Port Louis, he confirmed that recommendations were left by the auditors regarding the internal control system, however, he pointed out the problem with the implementation of such system. In Mapou, the Chief Executive is a formal officer from the ICAC, giving more focus on corruption issues. However, a systematic control

(internal control system or similar) does not exist in either Port Louis or Rivière du Rempart.

5.5.3. Observations from the interviews with the public officers

The following section will describe the observations from the interviews with the public servants and their supervisors. The description has the intention to give a summary of the answers I got.

The public servants

The first issue discussed was the public servant’s view and definition of corruption. All interviewees gave me a definition of corruption, mostly in line with the definition in the POCA. Some examples:

“somebody gains any gratification in contradiction with his duties” (officer 1); “abuse of power for personal gain, maybe money is involved” (officer 2); “easy benefit, like services, like discount in a shop” (officer 4);

“corruption, I don’t have a definition, but I have some examples, maybe when somebody offers you bribe, money, when somebody is accepting bribe or money” (officer 5).