A Comparison of Ecological, Social and

Economic Sustainability in Adaptation

Strategies in The Maldives and Kiribati

Charlotte Blomberg and Sandra Blomvall

Environmental Science Bachelor Thesis 15 credits Spring 2020

2

Abstract

Sea levels are rising around the globe due to thermal expansion and melting glaciers caused by global warming. The Maldives and Kiribati are some of the lowest lying atoll countries in the world, which makes them particularly vulnerable to the projected sea level rise. This thesis investigates what differences exist in the adaptation strategies for the Maldives and Kiribati, in terms of ecological, social and economic sustainability, through a qualitative content analysis of their respective National Adaptation Programme of Action (NAPA) documents. The NAPAs identify and describe the most urgent adaptation projects in each country. By identifying whether the adaptation projects are sustainable, more effective strategies can be implemented in the future. The results show that several adaptation projects fail to incorporate all three aspects of sustainable development, which may have contributed to unsustainable implementation of climate change adaptation measures, whereas some projects also show that it is possible to successfully integrate all aspects of sustainable development.

Keywords: Maldives, Kiribati, sustainable development, sea level rise, climate change, adaptation, SIDS, NAPA

3

Sammanfattning

Havsnivån stiger över hela världen på grund av termisk expansion och smältande glaciärer orsakade av den globala uppvärmningen. Maldiverna och Kiribati är några av de lägst liggande atolländerna i världen vilket gör dem särskilt utsatta för den förväntade havsnivåhöjningen. Denna uppsats undersöker vilka skillnader som finns i Maldivernas och Kiribatis klimatanpassningsstrategier vad gäller ekologisk, social och ekonomisk hållbarhet genom en kvalitativ innehållsanalys av deras respektive National Adaptation Programme of

Action-dokument (NAPA). NAPA identifierar och beskriver de mest angelägna anpassningsprojekten

i varje land. Genom att identifiera huruvida anpassningsprojekten är hållbara kan mer effektiva strategier implementeras i framtiden. Resultatet visar att flera anpassningsprojekt har misslyckats med att integrera alla tre aspekter av hållbar utveckling, vilket kan ha bidragit till ett ohållbart genomförande av klimatanpassningsåtgärder, medan vissa projekt även visar att det är möjligt att framgångsrikt integrera alla aspekter av hållbar utveckling.

Nyckelord: Maldiverna, Kiribati, hållbar utveckling, havsnivåhöjning, klimatförändringar, klimatanpassning, SIDS, NAPA

4

Table of Contents

1. Introduction ... 5

2. Aim of Study ... 6

3. Methodology ... 7

4. Sea Level Rise ... 8

4.1. Main Consequences of Sea Level Rise on Atoll Islands and Coastal Regions ... 9

4.1.1. Erosion ... 10

4.1.2. Groundwater Availability and Saltwater Intrusion ... 11

4.1.3. Biodiversity ... 11

5. Sustainable Development ... 13

6. Vulnerability ... 15

7. Development of Climate Change Adaptation Policy ... 16

8. Climate Change Adaptation ... 17

8.1. National Adaptation Programme of Action ... 19

8.2. Adaptation Measures for Coastal Protection ... 19

9. The Maldives ... 21

9.1. Climate Change Politics and Adaptation in The Maldives ... 22

10. Kiribati ... 25

10.1. Climate Change Politics and Adaptation in Kiribati ... 25

11. Results and Analysis ... 29

11.1. Maldives National Adaptation Programme of Action ... 31

11.2. Kiribati National Adaptation Programme of Action ... 33

11.3. National Adaptation Programme of Action Comparison ... 34

12. Discussion ... 37

13. Acknowledgements ... 41

5

1. Introduction

Sea levels are rising around the world due to thermal expansion and melting glaciers caused by global warming (Bellard, Leclerc, & Courchamp, 2013; Carvalho & Wang, 2019). Recent projections estimate that more than 160 million people around the world are currently living in areas that will be affected by sea level rise (SLR) by 2050 (Carvalho & Wang, 2019). Low-lying coastal areas are recognised as particularly affected by climate change, especially SLR. More specifically, atoll islands are considered the most affected, where human communities and infrastructure lies in coastal areas and where relocation opportunities are limited due to the small size and low-lying nature of islands. There are four countries made up exclusively of coral atoll islands (Barnett, 2017). Of these, the Maldives and Kiribati have the highest populations and thus, SLR here poses a great risk for a large number of people. SLR can have negative consequences for societies, such as loss of livelihoods, infrastructure, coastal settlements, economic stability and ecosystem services (Arnall & Kothari, 2015). As societies adapt to these changes, environmental degradation may occur, for example through changes in resource use or infrastructure and land use changes that negatively impact the natural environment (Stojanov, Duzi, Kelman, Nemec, & Prochazka, 2017). Human practices can thus exacerbate future risks and it is important for countries to prepare for the future to ensure the safety of citizens, minimise impacts on the environment and ensure sustainable development. There is evidence from both the Maldives and Kiribati that some adaptation measures implemented in the past have been unsustainable, especially from an ecological point of view (e.g. Stojanov et al., 2017; Weiss, 2015). This could be either due to the documents guiding the adaptation not being adhered to, or because the documents themselves are incompatible with sustainable development.

This thesis begins by explaining the aim of the study, followed by a description of the methodology used to answer the research question. Chapter 4 provides information about SLR and its consequences after which the concepts of sustainable development and vulnerability are introduced. In chapter 7 and 8 adaptation is explained in detail followed by a profile of the countries researched in this study: the Maldives and Kiribati. Finally, the results of the thesis are presented followed by a discussion of the findings.

6

2. Aim of Study

This study investigates how the adaptation strategies for the Maldives and Kiribati differ in terms of sustainability by answering the research question “what differences exist in the adaptation strategies for the Maldives and Kiribati, in terms of ecological, social and economic sustainability?”. The purpose is to identify if the respective adaptation strategies are sustainable so as to help inform more effective policies in the future. Striving for sustainable development is an important part of international agreements and hence it is essential that guiding documents on the national level encourage sustainable development too.

7

3. Methodology

In content analysis, documents are systematically coded based on predetermined categories (Bryman, 2018) and we deemed this to be a suitable method to answer the research question. Applying the method of content analysis as described by Bryman (2018), ecological, social and economic sustainability in the adaptation strategies for the Maldives and Kiribati were identified and compared. Through what Bryman (2018) calls strategic sampling, the National Adaptation Programme of Action (NAPA) for each country was chosen as the basis for analysis. NAPAs are implemented through the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and is a process for Least Developed Countries (LDCs) to identify adaptation activities of priority in response to climate change with the aim of reducing the economic and social costs of climate change (UNDP, 2020a). Although both countries have several documents and programs concerning adaptation, the NAPAs were selected because they were available for both countries which enables comparison between them. Moreover, both documents were published in 2007, which adds to ease and relevance of a comparison as opposed to comparing documents from the countries published several years apart. Some previous studies have analysed NAPAs (e.g. Lama & Becker, 2019) but to the best of our knowledge none have previously analysed the documents from a sustainability point of view. The NAPAs were found on the website of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) by searching for “Maldives NAPA” and “Kiribati NAPA” (UNFCCC, 2020a; UNFCCC, 2020b). These documents were also chosen for this thesis because they have been the foundation for the most urgent adaptation measures on the national level in each country and were thus appropriate for answering the research question. Additionally, they were possible to work through within the scope of the study. The part of the documents containing project descriptions were coded in accordance with methods described in Hjerm, Lindgren and Nilsson (2014). The codes were categorised into the three different aspects of sustainability: ecological, social and economic. What Bryman (2018) refers to as the manifest and the latent content was analysed. A qualitative analysis of the occurrence of categories then determined how ecologically, socially and economically sustainable each NAPA was, and a comparison was made of projects within and between the NAPAs.

8

4. Sea Level Rise

Global warming contributes to the thinning of glaciers, and increased melting of ice in Greenland and Antarctica since the 1990s is now causing noticeable climatic problems. The resulting increase in water flow together with thermal expansion causes sea levels to rise (Bellard et al., 2013; Carvalho & Wang, 2019). Thermal expansion is the relationship between heat and volume, meaning that as the sea warms due to global warming, the water increases in volume and contributes to SLR (Carvalho & Wang, 2019).

According to Bellard, Leclerc and Courchamp (2014) the sea level will increase by at least one meter by 2100. Today, an estimated 160 million people live on islands and in coastal regions situated less than one meter above sea level (Carvalho & Wang, 2019). The projected increase in sea level has led to a fear that many low-lying islands will disappear entirely (Palanisamy et al., 2014). SLR has accelerated since 1870, and while the sea level increased at a rate of between 1.3 and 1.7 mm per year during most of the 20th century, from 1993 the rate of global mean sea

level increased by between 2.8 and 3.6 mm per year. Even though sea levels have increased, there have been regional variances globally, including in the tropical Pacific and Indian Ocean, where SLR rates in some parts have been notably higher in comparison to the global average (Nurse et al. 2014; Perrette, Landerer, Riva, & Meinhausen, 2013). This variance is attributed to regional differences in salinity, depth, wind forcing and water temperature (Wyett, 2013). However, the Palanisamy et al. (2014) study showed that for the past 60 years the Maldives have had an increase in sea level, but that the variation around the annual sea level has been lower in the Maldives than on other islands in the Indian Ocean. Kiribati, on the other hand, will be affected by a variability in sea level due to El Niño/Southern Oscillation (ENSO) events (Donner & Webber, 2014). ENSO impacts both freshwater lenses and shorelines in Kiribati and generates westerly storms that can drive big waves into the lagoons that can intensify flooding and erosion (Donner & Webber, 2014). During ENSO periods the sea level can rise 30 cm higher than the normal sea level (Duvat, 2013). Due to climate change the intensity of ENSO events may increase, causing more extreme weather events and higher sea levels (Murphy, 2015). Therefore, while global SLR of the kind suggested by Bellard et al. (2014) is a global problem, particularly for densely populated low-lying island states, the situation is specific for each island group and adaptation measures need to be tailored for each specific situation.

9

4.1. Main Consequences of Sea Level Rise on Atoll Islands and

Coastal Regions

An atoll consists of small coral reefs and islands that form a chain around a lagoon (Deng & Bailey, 2017; Duvat, 2018). These islands are low-lying and generally sits less than five meters above sea level (Duvat, 2018). The foundation of the lagoon consists of carbonate platforms that were once a volcano (Deng & Bailey, 2017). Figure 1 shows the formation process of an atoll.

Figure 1. Atoll formation process. A coral reef is formed around a volcanic island. As the island subsides a fringing reef is created. In the last stage the volcanic island disappears and the barrier reef surrounds and protects the lagoon (Blomvall, 2020a).

SLR can have negative effects on atoll islands such as increased coastal erosion (Bulteau et al., 2015; Perry et al., 2011), changes in wave climate and marine ecosystems (Chowdhury, Behera, & Reeve, 2019), saltwater intrusion (Deng & Bailey, 2017; Perry et al., 2011) and loss of habitat for plant and animal species (Bellard et al., 2013, 2014). Saltwater intrusion can have serious effects on the use of agricultural land and drinking water (Perry et al., 2011) and a changed wave climate can reduce sediment deposition and the capacity of reef ecosystems to protect islands from storm waves (Duvat, 2018). There is, however, no consensus in the research regarding the vulnerability of atoll islands to SLR as some research show that islands have remained stable or even increased in area despite SLR (Bulteau et al., 2015; Duvat, 2018; Duvat, Salvat, & Salmon, 2017; Ford, 2013; McLean & Kench, 2015; Perry et al., 2011), whereas other research show that islands risk disappearing (Bellard et al., 2014; Deng & Bailey, 2017). More specifically, Bulteau et al. (2015) found that islands larger than ten hectares did not show signs of reduction in size, which is attributed to natural processes of sedimentation (Purkis, Gardiner, Johnston, & Sheppard, 2016).

10

4.1.1. Erosion

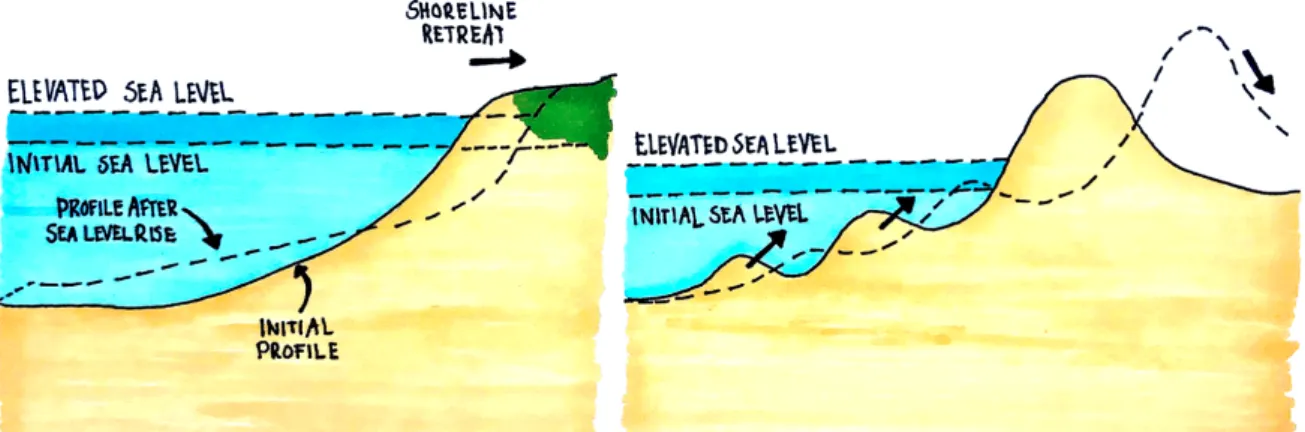

SLR is expected to generate faster coastal erosion (Aslam & Kench, 2017; Jeanson, Dolique, & Anthony, 2014), which contributes to a changing coastline (Bulteau et al., 2015). The relationship between SLR and erosion is illustrated in Figure 2. Continued SLR can create chronic erosion on the coasts of islands (Ford, 2013). Chowdhury et al. (2019) highlight that future wave climate will change due to SLR and hence marine ecosystems will change and coastal resilience to erosion will decrease.

Figure 2. The relationship between SLR and erosion. Both illustrations show how the initial profile changes and pushes land further inland due to the elevated sea level (Blomvall, 2020b).

In a study by McLean and Kench (2015), coastline and land area were analysed on more than 200 islands and 12 atolls located in the Pacific Ocean. There, the SLR has been three to four times higher than the global average in recent decades, but despite this, no major erosion has occurred (McLean & Kench, 2015).

Human activity is also a factor in a changed coastal system and these changes are mainly seen on coastal landscapes of islands (Gomez et al., 2019). Main factors are for example land reclamation (Aslam & Kench, 2017) and infrastructure, hence there is a clear link between erosion and human activity (Purkis et al., 2016). Coastal erosion affects settlements, facilities, utilities and infrastructure for tourism and is widespread on many small islands. Especially small islands in the Indian, Pacific and Atlantic Oceans and the Caribbean are vulnerable to erosion due to human impacts (Nurse et al., 2014).

11

4.1.2. Groundwater Availability and Saltwater Intrusion

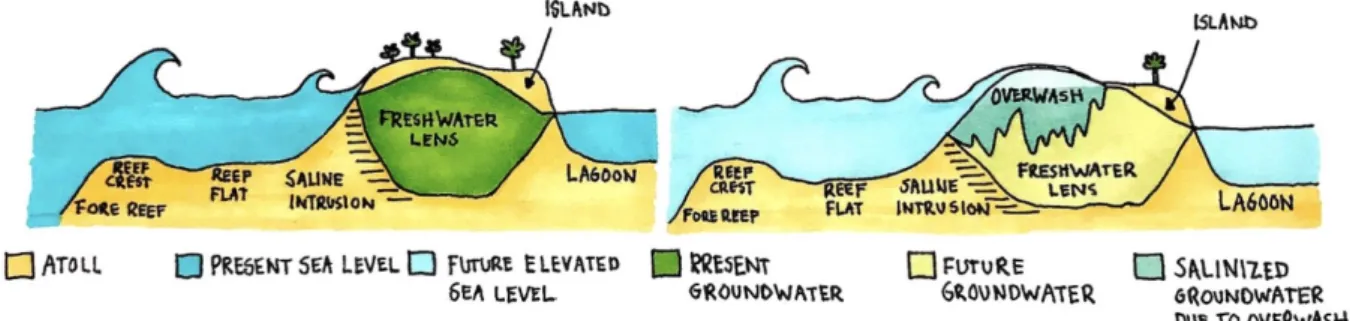

Flooding in connection with SLR is a serious threat to groundwater reservoirs on small coral islands (Alsumaiei & Bailey, 2018). When a small area is rapidly flooded, saline water is infiltrated into the groundwater, which makes it unfit for use (Alsumaiei & Bailey, 2018; Perry et al., 2011), creating problems for humans depending on clean water (Deng & Bailey, 2017). Ways in which SLR can impact the freshwater lens is described in Figure 3. Deng and Bailey (2017) exemplify that the use of clean water is estimated to be 50 to 100 litres per person per day in the Maldives. If sea levels increase by 5 mm per year from 2011 to 2050 combined with changing rainfall patterns, groundwater availability will decrease drastically.

Figure 3. Before (left) and after (right) SLR and the impact on the freshwater lens. As the sea level rises, more saltwater will infiltrate underneath the freshwater lens, but it will also create more overwash and flooding resulting in infiltration from above (Blomvall, 2020c).

Alsumaiei and Bailey (2018) show in their study that small islands are more affected by saltwater intrusion. Chattopadhyay and Singh’s (2013) study highlights how aquifers, which is the geological formation that stores groundwater, becomes more vulnerable if the saline infiltration occurs during the dry season.

Groundwater availability is also affected by humans. Population growth on small islands causes increasing pressures on water reserves and can also cause increased pollution (Storey & Hunter, 2010).

4.1.3. Biodiversity

A one meter increase in sea level by the year 2100 means that large parts of low-lying island ecosystems run the risk of falling below sea level which may contribute to reduced biodiversity (Bellard et al., 2013, 2014). A study of 4,447 oceanic islands conducted by Bellard et al., (2014)

12

showed that with a one meter SLR, 267 of these island would be permanently submerged. On the other hand, a scenario of six meters SLR will result in 826 submerged islands. Bellard et al. (2014) also estimate that the one meter SLR scenario will threaten about 28 animal and plant species, whereas the six meter SLR scenario threatens approximately 337 animal and plant species.

Perera, De Silva and Amarasinghe’s (2018) study in Sri Lanka showed that flooding related to SLR resulted in a reduced carbon sink function of mangrove trees. Thus, SLR contributes partly to direct negative effects but also to indirect effects that affect climate change globally (Perera et al., 2018). The world's mangroves and coral reefs had lost 35 percent and 20 percent of their areas, respectively, as of the year 2000 (Yohe et al., 2007).

An increase in coral mortality may occur due to acidification and warming of the ocean as a result of climate change. Because coral reefs act as a natural protective barrier for atoll islands, a loss of coral would not only mean a direct loss of biodiversity but could also worsen the effects of SLR (Kelman, 2018). Anthropogenic impacts on corals through for example destructive fishing practices, coral mining, reef blasting, dredging and sewage disposal will further contribute to these negative effects (Kelman, 2018; Ministry of Environment, Energy and Water [MEEW], 2007).

In summary, effects of SLR and human practices are closely linked, and anthropogenic influences are a key factor in morphological and environmental change in atolls (Duvat, Magnan, & Pouget, 2013).

13

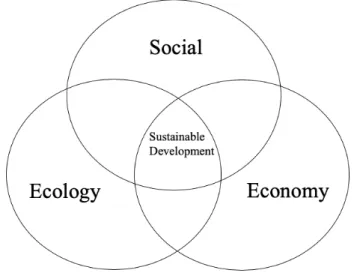

5. Sustainable Development

Climate change is recognized as a key factor affecting sustainable development, for both developed and developing countries (Yohe et al., 2007). During the 1980s the Brundtland Commission provided a frequently cited definition for sustainable development as: “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (Brundtland Commisson, 1987, p. 41). In the report, the separate aspects of nature conservation, economic development and pollution concerns came together. The argument was that issues of human development could not be separated from environmental issues and therefore incorporation of ecological sustainability with economic and social development was necessary (The Energy and Resources Institute [TERI], n.d). The model in Figure 4 shows how these aspects are incorporated to create sustainable development.

Figure 4. Model of how the ecological, social and economic aspects need to be incorporated to achieve sustainable development.

The United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, held in Rio de Janeiro in 1992, is seen as a milestone for sustainable development (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs [UN DESA], 2004). At the conference, the Rio Declaration was created as a guide for countries to future sustainable development. The document contains 27 principles and highlights, for example, the importance of integrating environmental protection in the development process and ensuring equity for both present and future generations. It also emphasizes the special needs of developing countries and the need for global cooperation to conserve, protect and restore ecosystems. States should also implement effective environmental legislation (United Nations, 1992). The participating states assumed a collective responsibility

14

to strengthen and advance the three pillars of sustainable development (ecological, social and economic) on global, regional, national and local levels (UN DESA, 2004).

According to Bonnedahl (2012), achieving balance between the three aspects of sustainable development is, however, more complicated than it may seem, as conflict between the aspects can arise. The economic aspect is dominant in today’s society and the focus on economic growth through continuous consumption provides a framework for how society is organised. Rapid population increase and economic growth poses threats to the ecological aspect of sustainable development through, for example, pollution, land conversion and overexploitation (Bonnedahl, 2012). The Brundtland Commission (1987) states that environmental maintenance and economic development can go hand in hand, but only if the economic aspect is secondary. However, economic growth has positive effects on the social aspect, reducing problems of, for example, malnutrition and access to clean water. It can also have positive effects for the environment, although these effects are more common in the later stages of development after environmental degradation may have already occurred (Bonnedahl, 2012).

15

6. Vulnerability

A key concept related to climate change impacts is vulnerability, which Wilby (2017) defines as “the predisposition to be adversely affected by climate variability and change” (p. 103). Vulnerability is determined by the level of exposure to climate hazards, the receptor’s sensitivity to harm and the capacity to adapt. Vulnerability can apply to, for example, individuals, communities, nations or natural systems and is multi-faceted and socially and geographically differentiated. Poverty can raise exposure and sensitivity and thus increase vulnerability. Nurse et al. (2014) describe four key stressors that are often mentioned as the function of island vulnerability: climate-induced, physical, socioecological and socioeconomic. These functions are central when it comes to determining the magnitude of impacts. Therefore, all the dimensions of vulnerability need to be evaluated to understand the climate vulnerability of islands. In the case of coral reef ecosystems for example, coral reefs that are already stressed due to non-climate factors become more vulnerable to climate change in comparison to those that are not experiencing other stresses (Nurse et al. 2014). Atoll countries are considered especially vulnerable to climate change, especially SLR, not only due to their low-lying nature and small size (Barnett, 2017), but because of the lack of economic resources and weak social support systems (IPCC, 2001).

16

7. Development of Climate Change Adaptation Policy

As early as 1989, island countries met in the Maldives for the Small States Conference on Sea Level Rise, where the development challenges facing small island states as a result of climate change were discussed. The countries called for support from developed countries in dealing with climate change through means of technology, funds, and training (Kelman, 2018).

The UNFCCC, established at the Rio Conference, entered into force in 1994 and today most countries are Parties to the Convention. It calls for special efforts to reduce the consequences of climate change and acknowledges the vulnerability of countries to these changes (UNFCCC, 2020c). According to UNFCCC there are two fundamental response strategies to climate change: mitigation and adaptation. Mitigation are the measures taken to reduce greenhouse gases (GHG) to limit climate change impacts (Fussel & Klein, 2006) and adaptation is “the process of adjustment to actual or expected climate and its effects” (Wilby, 2017, p. 221). According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 2001) strategic, proactive adaptation may make a huge difference in reducing vulnerability and understanding the opportunities linked to the effects and hazards of climate change.

Initially, mitigation measures were the main focus of the UNFCCC (UNFCCC, 2020c). Although adaptation was discussed, for example in IPCCs Second Assessment Report in 1996 (Nurse et al., 2014), it was not until 2001 that the Marrakesh Accords, a policy focus on adaptation within the UNFCCC, developed (Yohe et al. 2007). Thereafter, Parties to the UNFCCC agreed to establish funding arrangements specifically for adaptation (UNFCCC, 2020c).

Building on the UNFCCC, The Paris Agreement defines a global goal on adaptation, which is:

To enhance adaptive capacity and resilience; to reduce vulnerability, with a view to contributing to sustainable development; and ensuring an adequate adaptation response in the context of the goal of holding average global warming well below 2 degrees C and pursuing efforts to hold it below 1.5 degrees C. (UNFCCC, 2020d, first paragraph)

It requires all Parties to participate in adaptation planning and implementation through means such as national adaptation plans (UNFCCC, 2020d).

17

8. Climate Change Adaptation

Adaptation is now a key component of handling long-term climate change on a global scale. According to UNFCCC:

Adaptation refers to adjustments in ecological, social, or economic systems in response to actual or expected climatic stimuli and their effects or impacts. It refers to changes in processes, practices, and structures to moderate potential damages or to benefit from opportunities associated with climate change. (UNFCCC, 2020e, second paragraph)

Adaptation to climate change will enhance protection for people, livelihoods and ecosystems. Parties to the UNFCCC agree that adaptation strategies should follow a country-driven, gender-responsive, participatory and transparent method to be more considerate towards vulnerable communities, groups and ecosystems. Therefore, it should be guided and based on existing science and suitable traditional knowledge. The aim is to integrate adaptation into relevant environmental and socioeconomic policies and actions (UNFCCC, 2020e). Yohe et al. (2007) explain that climate change policies (including adaptation) and sustainable development measures could strengthen and reinforce each other.

The use of adaptation measures, as opposed to mitigation, has four convincing arguments according to TERI (n.d.): (1) some degree of climate change is unavoidable because of historical emissions despite powerful mitigation measures, (2) even if the results from positive mitigation measures can take decades to be noticeable, the effect of most adaptation actions occur almost immediately, (3) measures can be used on both a local and regional scale and one positive effect is not dependent on actions of others, and (4) adaptation may reduce risks related to current climate variability while also tackling the risks of future climate change.

Barriers to adaptation strategies in small island developing states (SIDS) have been widely discussed since IPCCs Second Assessment Report was published in 1996. According to Nurse et al. (2014), these barriers include; insufficient access to technological, financial and human resources; problems related to social and cultural acceptability of measures; legal and political frameworks imposing restrictions; a focus on island development rather than sustainability; more emphasis on short-term climate variability instead of long-term climate change; and the society’s preferences for ‘hard’ adaptation measures such as seawalls instead of using ‘soft’

18

measures like beach nourishment (Nurse et al. 2014). Furthermore, economies that are more diversified respond better to climate stress, but most SIDS specialise in developing monocultures (e.g. bananas or sugar) and in niche markets that increase their vulnerability (Nurse et al. 2014).

Even if drastic measures to reduce future emissions of GHGs are taken today, the need for climate change adaptation in small island states is urgent due to historical emissions (TERI, n.d). The risk of damage and losses are expected to increase under climate change, yet many small islands do not address high future risks but focus more on current risks (Nurse et al., 2014). According to IPCC (2001), adaptation options in coastal zones are more effective and more widely accepted if they are integrated with other policy initiatives such as disaster risk management and sustainable development strategies. For adaptation to be sustainable it is important that measures are planned and anticipatory as relying on reactive adaptation may have substantial ecological, social and economic costs. Further, they suggest that the adaptive capacity of coastal systems is related to the morphological, ecological and socioeconomic components of coastal resilience and that enhancing technical, institutional, cultural and economic resilience is, given future uncertainties, an appropriate adaptive strategy.

When infrastructural work is involved in adaptation to climate change, there is often big up-front operating costs. When applied to small islands, those costs are hard to minimise due to the size of the territory and population. The socioeconomic aspect is a reality that numerous SIDS have to deal with, even though the benefits can accumulate to island communities when adaptation is being implemented (Nurse et al., 2014). According to Nurse et al. (2014) countries with small areas and populations, particularly geographically isolated ones, have a higher adaptation and disaster risk reduction cost per capita due to high transport costs and access to a smaller resource base. Thus, communities lacking economic resources, with weak social support systems and poor infrastructure are more vulnerable and have less access to adaptation options, which stress the need for external assistance for many SIDS (IPCC, 2001). Furthermore, lack of awareness and knowledge act as barriers to effective implementation and success of adaptation programs. In Kiribati for example, researchers have found that traditional governance structures, religious beliefs and short-term planning approaches were obstacles to community engagement in climate change issues (Nurse et al., 2014). Regional cooperation and pooling of resources can help increase adaptive capacity for small island states (IPCC, 2001)

19

but Nurse et al. (2014) emphasize the importance of using caution when transferring adaptation experiences from one island to another to ensure that the specific biophysical, economic, social and political aspects of the island is considered and to avoid maladaptation.

8.1. National Adaptation Programme of Action

Parties to the UNFCCC carry out adaptation through a number of channels. The NAPA is one such channel (UNFCCC, 2020e). Because LDCs have a limited capacity to adapt to impacts of climate change, NAPAs have been introduced as a process in which LDCs identify adaptation activities of priority to reduce vulnerability and the economic and social costs of climate change (UNDP, 2020a). In the NAPA process, the importance of community-level input is emphasized as well as the recognition of grassroots communities as main stakeholders. Furthermore, the NAPAs should be action-oriented, flexible and based on national circumstances. The document lists and describes the activities of highest priority in a way designed to facilitate the implementation of the NAPA and development of adaptation projects (UNFCCC, 2020f).

8.2. Adaptation Measures for Coastal Protection

Coastal adaptation measures are commonly grouped into ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ measures. Hard measures include actions such as land reclamation and engineered structures like seawalls. These measures can be well suited for immediate protection but because they generally do not reduce wave energy, they can have adverse effects on beach erosion. They also hinder the creation of new landmass and are often made using coral rock which can amplify the effects of SLR. Many SIDS also do not have enough resources to adequately implement, maintain and monitor the construction. However, due to lack of knowledge of the adverse effects, seawalls and land reclamation projects are continuously being implemented in for example Kiribati (Donner & Webber, 2014).

Soft measures include for example reef restoration, beach nourishment and mangrove planting. These are potential ‘no regrets’ or ‘bottom- up’ alternatives to more resource-intensive measure. ‘No regrets’ refer to measures that would “improve living standards and reduce disaster risk regardless of the magnitude of climate change” (Donner & Webber, 2014, p. 339). Planting or restoring mangrove is fairly reasonable in cost and may decrease the occurrence of

20

erosion by creating sediment stability and lowering wave energy, which can minimise flooding by constructing land across sediment accretion. Due to the benefits associated with these measures, Kiribati's outer atolls have been encouraged to plant mangroves, because resources are limited, and the population tend to live further away from the shore. However, even soft measures can have unintended consequences. They are for example unsuitable on open ocean shorelines, and during the first years or decade of growth the mangroves do not protect against erosion and are thus only suitable for long-term protection. Therefore, adaptation planners in Kiribati’s capital recommend a combination of hard measures, to enhance the protection for key assets from land loss and flooding, and soft measures, which will protect from erosion, including that caused by hard measures (Donner & Webber, 2014).

There is also a third adaptation option: migration. It is however debated whether migration should be considered an adaptation option or if it is a last resort after all adaptation measures have failed. Migration can be used as a deliberate strategy to diversify income sources and thus provide opportunity to increase resilience and adaptation capacity in the long-term. However, it can also be argued that framing migration as a solution may lead to a reduced international effort to curb GHG emissions and urgent in-situ adaptation measures may be neglected. Other concerns about migration relate to the scale, numbers and location as well as the protection for migrants under international law (Allgood & McNamara, 2016). Research also show that opinions about migration are often diverging. A common finding in the migration literature is that a sense of identity associated with place is often a barrier to migration (Arnall & Kothari, 2015; Blomme, 2017; Kelman et al., 2019; Ratter, Hennig, & Zahid, 2019), but on the other hand many people on affected islands have a long history of migration for other purposes than climate change, such as employment or education (Kelman et al., 2019; Speelman, Nicholls, & Dyke, 2017; Stancioff et al., 2018, Stojanov et al., 2017). Often citizens of the affected countries have more immediate livelihood concerns and do not consider migration as a current worry. Therefore, terms like climate refugees or forced migration that are often used in external climate change discourse, are not terms that the general population identify with (Speelman et al., 2017; Farbotko & Lazrus, 2012).

21

9. The Maldives

The Maldives is a SIDS in the Indian Ocean (Figure 5) made up of 26 coral atolls. The country consists of 1,190 islands of which 200 are inhabited and another 80 are used for tourist resorts. No island is larger than 10 km2 and over 80 percent of the islands sit less than one meter above

sea level (Stojanov et al., 2017). Of the 380,000 inhabitants, 104,000 live on the capital island Malé, which is one of the most densely populated cities in the world (Arnall & Kothari, 2015).

The Maldives is extremely vulnerable to climate change and other natural hazards because of the geographic and geophysical features of the country such as the low elevation, small size, limited width and unconsolidated nature of its coral islands. In the past the Maldives have shown substantial natural resilience to varying climate conditions, changing sea levels, events from extreme weather, wave action and other major hazard events. Coral reefs, coastal sand ridges, natural vegetation and other natural features play an essential role in protecting the islands from extreme weather events and their impacts. The value of coral reefs in both biological and economic terms have long been acknowledged (UNDP, 2020b).

Figure 5. Location of the Maldives in the Indian Ocean (Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2020a).

22

9.1. Climate Change Politics and Adaptation in The Maldives

The Maldives announced in 2011 that they had signed the world's first Strategic National Action Plan, which included disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation. Broad consultations with important sectors formulated the policy and the focus lies on governance and decentralisation to successfully deal with risk reduction and adaptation. The policy is seen as a landmark initiative regarding adaptation and disaster risk reduction (UNDP, 2020c).

Hirsch (2015) conducted a study to portray the years of Mohamed Nasheed’s presidency in the Maldives between 2008 and 2012. Nasheed was the first democratically elected president after 30 years of dictatorship but he was abruptly overthrown in 2012, which has caused political instability in the country. The years between 2008 and 2012 were years of climate mobilization where climate change was seen as a national security issue and the country pledged to become carbon neutral by 2020. Hirsch (2015) claims that the threat of disappearance and the ‘war’ against emissions “organized an internal sense of shared futurity” (p. 194). But the political culture in the Maldives has always been tense between city and outer atolls (Hirsch, 2015; Speelman et al., 2017), so although Nasheed’s goal of Maldivian carbon neutrality gave a sense of community to the people in the core (i.e. urban areas), his climate agenda failed to resonate with many in the periphery (i.e. rural areas) due to the potential impacts on more immediate development goals.

Many Maldivians believe it is important to adapt to future climate change impacts (Kelman et al., 2019, Stojanov et al., 2017) and even though SLR is rarely seen as a main reason for migration by the local population, it has been an important part of the climate change adaptation strategy in the Maldives (Arnall & Kothari, 2015). The government of the Maldives have long wanted to consolidate the population onto a few islands (Speelman et al., 2017), and have encouraged migration to the capital partly to reduce government costs of service delivery (Magnan et al. 2016; Shakeela & Becken, 2015). Thus, to prepare for SLR the country has adopted the Safer Island Strategy. The project aims for the larger islands of the country to adapt to climate change through land reclamation and other hard measures to enable Maldivians to migrate there. The main example is Hulhumalé, which is a 100 percent reclaimed island that is set to be inhabited by 100,000 new people by 2030. However, the creation of artificial environments can have negative impacts on the ecosystem by for example contributing to the

23

destruction of ecologically important coral reefs and the interruption of sediment movements (Stojanov et al., 2017). Furthermore, the consolidation projects have not always been supported by the local population (Shakeela & Becken, 2015) who instead feel that there should be investments made on other islands so as to increase development there and to relieve population pressure on the core islands (Speelman et al., 2017). Additionally, Bisaro (2019) found that ensuring equitable distributional outcomes in land reclamation projects were challenging as they often are associated with prestige developments.

Erosion is reported as a serious problem in the Maldives that will be further exacerbated by SLR. Kothari and Arnall (2019) attribute some environmental changes to the rapid growth of the guest-house industry, which is a result of a 2009 government ruling allowing tourists to vacation on inhabited islands. Tourism was previously only allowed on designated resorts separated from the Maldivian population. It is believed that this ruling will lead to a more equal economic development providing younger people with local employment and thereby reducing the migratory pressure on Malé. However, human practices associated with increased tourism, such as infrastructure development, land reclamation, removal of seagrass, as well as dredging of sand to create swimming lagoons can exacerbate erosion (Kothari & Arnall, 2019; Sovacool, 2012a). Integrating tourism with sustainable development can thus be challenging for SIDS (Robinson, Newman, & Stead, 2019).

To reduce the environmental risks associated with hard coastal adaptation measures, Sovacool (2012a, 2012b) recommends a shift to soft coastal adaptation measures. However, these measures are currently largely absent in the Maldives as hard measures generally have a higher credibility (Ratter et al., 2019; Sovacool, 2012a). Ratter et al. (2019) believe that to sustainably deal with the coastal erosion expected in SIDS in the future, a fundamental shift in adaptation management will be needed. The contrasting paradigms of environmental governance, caused by the political situation in the past decade, have led to uncertainty among local authorities and communities as to what their role and power is in relation to the national government (Ratter et al., 2019). They found that even though a Decentralisation Act was adopted in 2010, decision-making continues to happen at the national level. People at the decision-decision-making level were surprised to hear that the local population had a positive attitude towards soft measures as they assumed locals preferred hard measures to be implemented. The local community showed concern about preserving the environment and wished to be included in the decision-making

24

process. The lack of community involvement was attributed to the top-down centralised national politics and to the fact that no funds are allocated for local governments to implement adaptation measures (Nunn, Aalbersberg, Lata and Gwilliam, 2014; Ratter et al., 2019). Sovacool (2012a, 2012b) identified inconsistent political commitment, lack of coordination and competing priorities as barriers to effective adaptation management. Furthermore, public participation is not practiced as part of the Environmental Impact Assessment process in the country (Ratter et al., 2019; Shakeela & Becken, 2015), but local voices require much more prominence if policy is to be effectively executed (Ratter et al., 2019; Stancioff et al., 2018). The low level of trust in the government was seen as another major barrier (Ratter et al., 2019). Additionally, the diversity of the islands requires tailored measures for different islands as patterns of sedimentation, coral reef composition and sociodemographic variables all vary (Sovacool, 2012a).

25

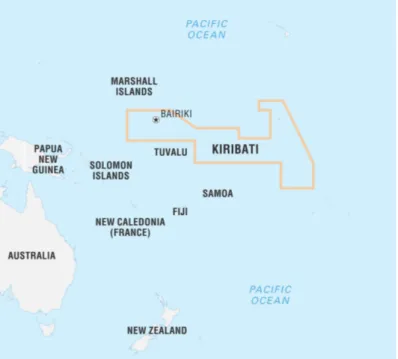

10. Kiribati

Kiribati is a SIDS in the Pacific Ocean (Figure 6) consisting of 32 low-lying coral atolls grouped into three island chains as well as a single raised limestone island (Storey & Hunter, 2010). The country gained independence from British rule in 1979. Although the land area is less than 811 km2 the country has the largest Exclusive Economic Zone of Pacific Ocean island states at 3.5

million km2 (Mallin, 2018). The majority of the country lies below three meters above sea level

(Ellison, Mosley, & Helman, 2017) and it is estimated that 55 percent of the country may be vulnerable to inundation by 2050 (Allgood & McNamara, 2017).

The country has a population of approximately 110,000 of which half reside in the capital Tarawa (Smith, 2019). It is one of the poorest countries in the Pacific and foreign sources support approximately half of the economy (Donner & Webber, 2014).

10.1. Climate Change Politics and Adaptation in Kiribati

Much like the Maldives, former president of Kiribati, Anote Tong, made efforts to position the country as a global icon for SLR consequences (Mallin, 2018). Wyett (2013) claims that Kiribati will be one of the first countries to face relocation due to climate change. Tong’s

Figure 6. Location of Kiribati in the Pacific Ocean (Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2020).

26

strategy was to plan for the worst and hope for the best by firstly promote a reduction of GHGs, secondly implement adaptation and thirdly prepare for relocation (Barnett, 2017). The ‘Migration with Dignity’ policy aims to identify countries where young Kiribati citizens can fill labour needs or provide skills and gradually transition to society through seasonal work programs (Donner & Webber, 2014) and thus more easily become established in the host country (Hermann & Kempf, 2017). Wyett (2013) suggests that a failure to create a practical migration strategy would be a disaster in which the population would gradually lose livelihoods, agency and land and become humanitarian refugees. Barnett (2017) highlights the importance of planned migration as it is less traumatic when there is sufficient time to familiarize with the place and the idea of relocation, and when there is time to control and plan the move.

The Tong administration approached “in-situ adaptation as a transitory solution” (Mallin, 2018, p. 247) whereas migration was seen as the key solution, eventually leading to a 22 km2 land

purchase in Fiji in 2014 (Hermann & Kempf, 2017). The land purchase was, according to the government, made as a way to ensure food security for Kiribati, but many citizens nonetheless associate it with a possible future relocation (Hermann & Kempf, 2017). Allgood and McNamara (2017) found that most participants in their study supported the government finding a new place for resettlement with in-situ adaptation coming second, accepting that migration is a likely future outcome. Barnett (2017) cautions however, that focusing on relocation may compromise the commitment to mitigate emissions and adapt, as well as undermine the sustainable management of environments. Another critique is that by planning for the distant future, the government has ignored more urgent problems (Barnett, 2017; Mallin, 2018).

Although Kiribati is a Party to the UNFCCC, Nunn et al. (2014) believe there is a gap between declaration and implementation. Even though adaptation is considered vital for atoll islands, the implementation has so far been fairly limited (Barnett, 2017). Some small-scale adaptation projects to limit the effects of climate change have been implemented, such as improving water supply management, protecting public infrastructure, replanting mangroves and constructing seawalls (Wyett, 2013). Duvat, Magnan et al. (2017) claim, however, that the natural sensitivity of islands in Kiribati to inundation have been made worse by unsustainable development practices leading to environmental degradation, which has undermined any natural resilience and thereby increased the vulnerability of the country to climate change.

27

Kiribati has seen a rapid increase in population in recent years, which together with economic and social weaknesses, such as high unemployment, agricultural instability, a small and unstable export base, and a dependence on foreign aid, further exacerbate the country’s vulnerability (Wyett, 2013). The most rapid population growth is seen on the capital island Tarawa due to migrants arriving from periphery islands in search of work, which has resulted in huge challenges to sustainable development. The overcrowding has led to inappropriate settlements and increasing pressures on, and pollution to, water reserves, but the country has few resources to adequately address these issues (Storey & Hunter, 2010).

Land reclamation and shoreline construction have taken place as a way to accommodate the growing population on Tarawa (Donner & Webber, 2014) but materials for reclamation are often collected from adjacent areas, which disrupts coastal processes and contributes to erosion (Duvat, 2013). Additionally, coral reefs that act as natural protective barriers from SLR are threatened through other effects of climate change, namely, acidification and warming of the ocean, which could potentially exacerbate the effects of SLR (Murphy, 2015). This is further worsened through the traditional practice of using lagoon sediment and coral rock to construct seawalls and fish traps. The negative effects of seawalls are not clearly understood in Kiribati and hence these measures are continuously being implemented (Donner & Webber, 2014). A majority of respondents in Allgood and McNamara’s (2017) study had built some sort of coastal protection such as seawalls or mangroves. Donner and Webber (2014) showed that even when extensive planning, technical studies and consultation is in place, adaptation measures may still be implemented inadequately. These actions have together contributed to additional population exposure to coastal hazards like erosion and flooding and thus increased the vulnerability to SLR impacts (Donner & Webber, 2014; Storey & Hunter, 2010). Kumar and Taylor (2015) found that 97 percent of infrastructure in Kiribati was located within 500 m of the coast, with 67 percent within 100 m. Previous policies to reduce population pressure by encouraging migration to less populated atolls have failed (Donner & Webber, 2014).

Apart from the NAPA, Kiribati has several documents and programs concerning adaptation. Most notably, the Kiribati Adaptation Program (KAP), adopted in 2003 and facilitated by The World Bank (Webber, 2013), has supported the understanding of climate change impacts, development of adaptation measures as well as the integration of adaptation into policy. The third phase of the KAP aims to support implementation of the actions identified in the NAPA

28

(UNDP, 2020d). Barnett (2017) argues that the KAP possibly is the most sustained effort by any developing country to manage adaptation. But the program has also received some criticism, describing it as a failure (Storey & Hunter, 2010) and as a ‘performance’ of vulnerability rather than actually addressing the risks of climate change (Webber, 2013). Donner and Webber (2014) found that the coastal protection implemented through the KAP had been poorly designed and none had provided completely effective protection (Wyett, 2013). The unsuccessful outcome of the KAP is, according to Cauchi, Correa-Velez and Bambrick (2019), due to the lack of community involvement. Nunn et al. (2014) believe that the failure of the KAP is largely due to other threats to sustainability the country is facing but also attribute it to the low number of qualified government professionals and the difficulties of reaching periphery communities. There is also a belief among the rural population that there is a lack of government will to pursue equitable adaptation across the country.

Decision-makers in Kiribati have to consider the social and political aspects of adaptation as well as balance trade-offs between short-term and long-term costs. Even if the long-term outcome of future SLR is uncertain, delaying adaptation risks near-term harm due to the sea level variability caused by El Niño. However, inexpensive measures implemented now may be inadequate for long-term protection from SLR (Donner & Webber, 2014). According to Storey and Hunter (2010) “tension between a lack of available resources and demands for development means that SIDS such as Kiribati face careful balancing acts between ‘development’ initiatives and environmental impacts” (p. 177) but state that strategies that strengthen both biophysical and social resilience is of utmost importance.

29

11. Results and Analysis

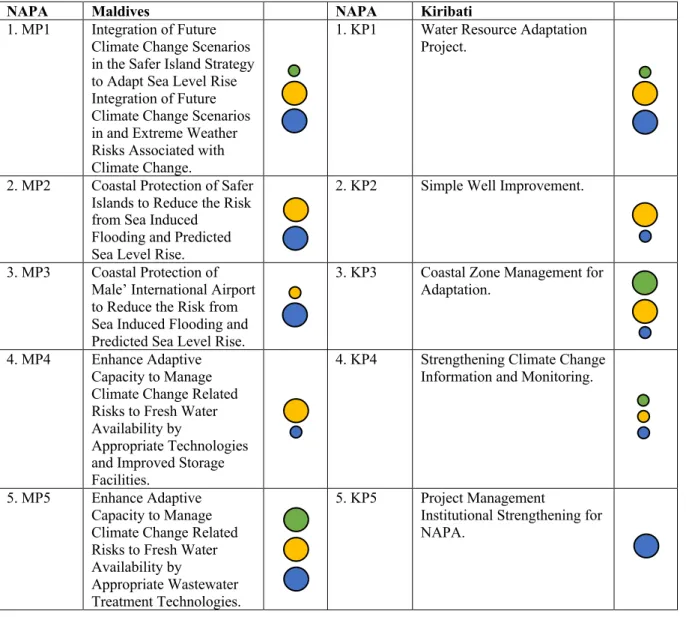

The following results describe the adaptation needs identified in each NAPA and how the ecological, social, and economic aspects are considered in each project. The NAPA of the Maldives (MEEW, 2007) describes 12 urgent adaptation projects and the NAPA of Kiribati (Ministry of Environment, Land, and Agricultural Development [MELAD], 2007) highlights 9 urgent adaptation projects. Table 1 below shows the results of the qualitative analysis, with coloured circles indicating if the project considered the ecological (green circle), social (yellow circle) and/or economic (blue circle) aspects of sustainable development. The circle is larger if the aspect is more dominant in the project.

Table 1. Adaptation projects identified in the NAPAs of the Maldives and Kiribati and which aspects of sustainability that have been considered.

NAPA Maldives NAPA Kiribati

1. MP1 Integration of Future Climate Change Scenarios in the Safer Island Strategy to Adapt Sea Level Rise Integration of Future Climate Change Scenarios in and Extreme Weather Risks Associated with Climate Change.

1. KP1 Water Resource Adaptation Project.

2. MP2 Coastal Protection of Safer Islands to Reduce the Risk from Sea Induced

Flooding and Predicted Sea Level Rise.

2. KP2 Simple Well Improvement.

3. MP3 Coastal Protection of Male’ International Airport to Reduce the Risk from Sea Induced Flooding and Predicted Sea Level Rise.

3. KP3 Coastal Zone Management for Adaptation.

4. MP4 Enhance Adaptive Capacity to Manage Climate Change Related Risks to Fresh Water Availability by

Appropriate Technologies and Improved Storage Facilities.

4. KP4 Strengthening Climate Change Information and Monitoring.

5. MP5 Enhance Adaptive Capacity to Manage Climate Change Related Risks to Fresh Water Availability by

Appropriate Wastewater Treatment Technologies.

5. KP5 Project Management

Institutional Strengthening for NAPA.

30 6. MP6 Increase the Resilience of

Local Food Production Through Enhancing the Capacity of Local Farmers and Communities to Address Food Security Issues Caused by Climate Change and Climate Variability.

6. KP6 Upgrading of Meteorological Services.

7. MP7 Improve the Health Status of the Population by the Prevention and

Management of Vector-borne Diseases Caused by Changes in Temperature and Flooding due to Extreme Rainfall.

7. KP7 Agricultural Food Crops Development.

8. MP8 Improve Resilience of Island Communities to Climate Change and Variability Through Sustainable Building Designs.

8. KP8 Coral Monitoring, Restoration and Stock Enhancement.

9. MP9 Investigating Alternative Live Bait Management, Catch, Culture and Holding Techniques in the Maldives to Reduce Vulnerability of the Tuna Fishery Sector to the Predicted Climate Change and Variability.

9. KP9 Upgrading of Coastal Defenses and Causeways.

10. MP10 Protection of Human Settlements by Coastal Protect Measures on Safer Islands.

11. MP11 Increase Resilience of Coral Reefs to Reduce the Vulnerability of Islands, Communities and Reef Dependant [sic] Economic Activities to Predicted Climate Change. 12. MP12 Flood Control Measures

for Vulnerable Islands.

In the following results, the projects will be described using the abbreviations in Table 1, MP1-MP12 for the Maldives and KP1-KP9 for Kiribati.

31

11.1. Maldives National Adaptation Programme of Action

The NAPA of the Maldives describes 12 adaptation projects. In the project description of MP1, concerning the integration of climate change scenarios into the Safer Island Strategy (see p. 22 for brief information about the strategy), the aspects of sustainable development are not easily distinguishable. Some activities proposed for the project mention environmental aspects, such as “develop environmental guidlines [sic] for land use planing [sic] at island level” (MEEW, 2007, p. 48), but in general the project appears to have more of a social and economic focus to reduce climate change impacts on society. Similarly, the goal of MP2 is to “enable the communities to sustain social and economic development in times of emergencies and disasters” (MEEW, 2007, p. 50). Thus, the focus on the social and economic aspects of sustainable development is evident. Through technical and engineering studies for the implementation of adaptation options on the Safer Islands, it is possible that the ecological implications have been considered in later stages of the project, but it is not explicitly mentioned. The high financial investment cost is mentioned as a barrier to the project. Interestingly, MP10 is almost identical to MP2, but adds the importance of implementing innovative coastal protection measures for the Safer Islands. Whether these innovative measures are going to be sustainable is not mentioned. In all other regards, the project has the same social and economic focus as MP2.

Sustainability is mentioned in the title of MP8, but there is no further description of what this sustainable building design would be and how this would possibly affect the environment. The main focus is on strengthening buildings and infrastructure for social and economic sustainability, but it is possible that ecological sustainability will be incorporated.

MP3, regarding coastal protection for the international airport, has no mention of ecological sustainability, but rather economic sustainability is the main aspect being discussed due to the reliance on tourism in the country. The importance of protecting the airport infrastructure for food security is also stated. MP6 is also related to food security by aiming to strengthen local food production. There is an emphasis on sustainable food production, which should thereby include all three aspects of sustainability, although no further information regarding this is provided.

32

MP4 focuses on securing freshwater resources for the human population in the country by harvesting rainwater and investing in desalination plants. Although these measures will help sustain the health and well-being of the population, the project mentions nothing about protecting the available freshwater resources that are valuable for the environment. In comparison, MP5 has a much clearer ecological focus. By upgrading wastewater treatment technologies, the project not only aims to secure the health of the citizens but also to protect coral reef biodiversity, increase the sustainability of fisheries and development of tourism, thus touching on all aspects of sustainable development.

MP7 acknowledges how anthropogenic practices can have negative impacts on the environment and how this can increase the spread of disease. Through integrated vector management the country aims to combat this issue in a way that is considered environmentally sound, cost-effective and sustainable.

The coral reefs are of great importance for the economic development of the Maldives, partly because of the tuna fishery sector, but the protection of the reefs have benefits for both the economic and ecological sustainability of the country. MP9 concerns the tuna fishery sector and does not only highlight the economic benefits, but also the ecological benefits of protecting the sector by “promoting sustainable use of the coral reefs and making them more resilient to natural disturbances caused by climate change” (MEEW, 2007, p. 69). MP11 highlights the lack of awareness in protecting and minimising human induced stresses on the coral reefs and aims to close this knowledge gap by investing in research so as to be able to adapt appropriately and ensure sustainable development. One aspect of the project is to research how land reclamation and other development measures impact the functioning of coral reefs. This is an important point of the NAPA as the projects relating to land reclamation rarely mention the ecological consequences of this adaptation measure. For example, MP12 describes that through land reclamation and backup mobile pumping systems, the vulnerability of three Safer Islands will be reduced but there is no mention of the negative environmental impacts associated with these sorts of measures. MP9 and MP11, on the other hand, demonstrate how ecological, economic and social sustainability can go hand in hand and generate positive effects for both maintaining biodiversity and sustainable use of living marine resources.

33

11.2. Kiribati National Adaptation Programme of Action

KP1 describes the social and economic impacts of reduced freshwater availability as a result of SLR, but also emphasizes how excessive withdrawal from water lenses negatively affect biodiversity and natural systems. Thus, even though the main focus of the project is to maintain freshwater supplies for human uses, all aspects of sustainable development have been considered in some way in the project. KP2 also relates to water use but aims to reduce the spread of disease by improving 500 water wells during a three-year period, under surveillance of water technicians and island-based sanitarian aides. The social aspect is evident but how the project will affect the environment is not further investigated. Apart from this project, KP6 and KP9 also fail to relate to ecological sustainability in any way. KP6 will improve the country’s meteorological services to be able to obtain more accurate weather information so as to avoid costly climate related risks to economic growth and livelihoods. By upgrading the existing seawalls and causeways, the aim of KP9 is to better protect infrastructure and public assets from climate change. There is no mention of how this measure may affect the environment or any indication that this is considered. KP7, on the other hand, describes benefits that can be associated with ecological, social and economic sustainability. The main goal is to provide food security and economic opportunities, but by diversifying food crop production and establishing gene banks, it also promotes biodiversity.

KP3 highlights that previous institutional arrangements concerning coastal development have been ineffective which could refer to an acknowledgement of potential negative environmental impacts of developments. To improve the situation the project aims to increase public awareness regarding coastal processes, to enhance the resilience of coastal assets and ensure sustainable use of coastal resources. Further, the aim is to empower local communities to manage coastal zones with a focus on soft adaptation measures such as mangrove planting. If implemented right, this could be beneficial for both social and ecological sustainability, but if unsuccessful it could have adverse effects on the environment. KP4 is another project aimed at increasing knowledge about climate change impacts on life and environment, but at the level of decision-making. Although no aspects of sustainability are mentioned explicitly, the focus on fulfilling objectives of the UNFCCC and other international conventions would implicitly mean that sustainability would be addressed and subsequently considered in adaptation. Similar to KP4, KP5 is an institutional project aimed at incorporating climate change adaptation into

34

relevant government Ministries Operational Plans. The focus is on economic development and poverty reduction by mainstreaming adaptation.

Similar to the Maldives, the economy of Kiribati is dependent on coral reefs through fisheries. The aim of KP8 is to primarily restore the health of coral in areas that are critical for maintaining the productivity of fisheries. The project will include implementing a sustainable monitoring programme, creating protected marine areas and artificial reefs, as well as raising awareness and transplanting coral. Another factor is the disease ciguatera, which affects human health through the consumption of contaminated fish. The spread of the disease is exacerbated by coral mortality and thus the protection of the reefs can reduce the spread. Hence, this project has a focus on ecological sustainability while simultaneously supporting economic and social sustainability.

11.3. National Adaptation Programme of Action Comparison

The qualitative analysis of the NAPAs shows that numerous projects have similarities in terms of adaptation goals and implementation but there are also several differences. Notably, Kiribati has a bigger focus on institutional projects (KP3, KP4, KP5), whereas the Maldives only has one project (MP1) aimed at institutional changes. These projects generally have more focus on economic and social sustainability, which may be attributed to the fact that these do not directly affect the environment in a negative way. However, if the institutional projects are inappropriately implemented and for example fail to enhance environmental knowledge (Nurse et al., 2014), it may have undesirable consequences for the environment. Of these, KP3 is the only project clearly emphasizing ecological sustainability by encouraging soft adaptation measures, although MP1 also highlights the need to develop environmental guidelines for land use planning.

A recurring theme in the NAPA of the Maldives is a focus on infrastructure, whereas this is much less evident in the NAPA of Kiribati. Five projects in the Maldives (MP3, MP2, MP8, MP10, MP12) and one project in Kiribati (KP9) are completely dedicated to infrastructure adaptation. Furthermore, there is one project in the Maldives that relates to infrastructure in some way (MP1) and one in Kiribati (KP2). The fact that the main focus in Kiribati is on institutional changes as well as upgrading the meteorological system (KP6), and the focus in

35

the Maldives is on infrastructure, could be a consequence of differences in the economic development of the countries. In terms of sustainable development, it is surprising to find that almost none of the infrastructure projects mention anything about ecological sustainability, except for MP8. This project mentions sustainable building designs, but without adequate information about what this would look like in reality. Economic development seems to be central in the majority of the projects. It is also interesting to note that two of the projects relating to infrastructure in the Maldives are almost identical (MP2, MP10) with the sole difference that MP10 highlights the importance of implementing innovative coastal protection measures on the Safer Islands.

There are three projects relating to freshwater resources (MP4, MP5, KP1). The projects MP5 and KP1 touch on all aspects of sustainable development by not only describing how the projects will secure freshwater for social and economic purposes, but also emphasize how the environment will benefit by supporting biodiversity and natural systems. MP4 however, only targets the needs of the population through desalination and rainwater harvesting without considering the ecological consequences of not adequately protecting freshwater resources. The countries have one project each relating to food production (MP6, KP7). These projects both mention the importance of sustainable food production as a way to adapt to climate change. However, Kiribati stands out by putting more weight on the ecological aspect by stressing the importance of food crop diversity and gene banks.

Both countries also have a project each to reduce the spread of disease. MP7 acknowledges that human practices can impact the environment negatively and contribute to the spread of disease but offers a solution in the form of integrated vector management as a sustainable measure to combat the issue. KP2 on the other hand aims to upgrade water wells to improve human health. Thus, the social aspect is the heart of the projects, even though the Maldives considers the ecological aspect as well.

The Maldives and Kiribati are both economically dependent on coral reefs, which is brought up in three projects (MP9, MP11, KP8). Although the economic aspect is clear in all three projects, they all address the social and ecological aspects as well. The projects highlight the importance of the well-being of the coral reefs not only for the economic gain but for biodiversity. All

36

projects aim to increase knowledge of the functioning of coral reefs but KP8 does a particularly good job of highlighting ecological sustainability by for example introducing protected marine areas. The projects demonstrate how all aspects of sustainability can be integrated in an effective way.