From the

AERA Online Paper Repository

http://www.aera.net/repositoryPaper Title

"I Have Read Some Articles on the Subject":

Selective Truths in the Education Debate

Margareta Serder, Malmö University; Christian Jan

Lundahl, Örebro University

Author(s)

Teacher Effectiveness and Teacher Accountability

Session Title

Roundtable Presentation

Session Type

4/7/2019

Presentation Date

Toronto, Canada

Presentation Location

Data use, Educational Reform, Politics

Descriptors

Mixed Method

Methodology

Division L - Educational Policies and Politics

Unit

Each presenter retains copyright on the full-text paper. Repository users should follow legal and ethical practices in their use of repository material; permission to reuse material must be sought from the presenter, who owns copyright. Users should be aware of the .

Citation of a paper in the repository should take the following form:

[Authors.] ([Year, Date of Presentation]). [Paper Title.] Paper presented at the [Year] annual meeting of the American Educational Research

Association. Retrieved [Retrieval Date], from the AERA Online Paper Repository.

AERA Code of Ethics

10.302/1430966

1

Objectives

Scientists and philosophers should be shocked by the idea of post-truth, and they should speak up when scientific findings are ignored by those in power or treated as mere matters of faith. Scientists must keep reminding society of the importance of the social mission of science – to provide the best information possible as the basis for public policy (Higgins, 2016, p. 9).

The above quote was published in one of the most prestigious scientific journals of our time,

Nature, on 18 November, 2016. It illustrates that even to the seldom-contested ‘hard

sciences’, the way in which research is received by society has become a critical issue. The concerns that we raise in this paper are linked to the theme of this conference – the notion of

post-truth and especially how it has challenged scholars of education and contributed to “the double bind of a disrespected craft in a disrespected field,” as it is expressed in the call for the

conference. This paper is concerned with the position of ‘truth’ in contemporary educational

debate: what is claimed to be ‘true’ about schools, by whom, and with what type of evidence? And further, how is educational research positioned in the public educational debate?

Post-truth is defined as “relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief” (Oxford Dictionary 2016). However, to Kathleen Higgins, quoted above, post-truth is also about the place of honesty (Higgins 2016). Even in politics, the cliché still “expects honesty to be the default position, but in a post-truth world, this no longer holds” (ibid). Antonyms of honesty are corruption, distrust and the like. This suggests that post-truth is highly linked to questions of morality. Keyes, one of the first to publish academic work on truth, saw

post-truthfulness as a kind of alt.ethics that “exists in an ethical twilight zone” (Keyes 2004, 13). According to Keyes, the ways that these alternative ethics come about are not as

straightforward lies: “Instead we ‘misspeak’. We ‘exaggerate’. We ‘exercise poor judgement’” (ibid).

We believe that it is vital to understand how (post-)truth is constructed in our societies and how we, as researchers, might be able to become more skilled at addressing it as we are communicating our research. To denote the ways truth comes about in the education debate studied for this paper, we use the term selective truths.

In the present study we are interested in how educational research (and its data and facts) are used as arguments in the education debate and, in particular, compared to how PISA results are used. Our case looks at how PISA and educational research have been used in media and in parliamentary debates in Sweden since the beginning of 2000. Sweden is an interesting case due to the decline in PISA results from 2003–2012 that sent Sweden into so-called ‘PISA shock’, which we also recognise from other countries with poor trends. This ‘shock’ could lead to a ‘politics of crisis’, producing a relatively high normative impact of PISA on education policy (Breakspear 2012). Several studies have been conducted on the impact of

2 PISA on policy making (e.g., Bieber and Martens 2011; Breakspear 2012; Hultqvist et al. 2018; Pizmony-Levy and Bjorklund 2018). However, there have not yet been any

explorations of how the talk about PISA co-exists with other ways of knowing about education within the education debate.

Theoretical framework

In both the Swedish press and in the Swedish Parliament, the education debate has focused on the call for reforms. In the present paper, we use “policy borrowing and lending” (e.g.,

Steiner-Khamsi and Waldow 2012) as a concept for understanding education policy reforms. A central aspect is how selective references to other countries’ policy can be used to

legitimise (justify) the own country’s policy changes (Schriewer and Holmes 1988, Andersen 2009). Who a policy refers to may change over time (Schriewer and Martinez 2004), but it is often about seeking legitimacy for (political) changes by referring to other countries or

international organisations. Referring, or externalising, to what it looks like in other countries, or to what research (or PISA) says, are examples of possible effective ways of justifying a new reform. When an externalisation is very specific we call it a selective truth, since one specific answer to a problem is chosen from among several available alternatives. Our assumption is that the way in which externalisations are used in media and politics signals what counts as valid knowledge about education (cf. Waldow 2017).

In our analysis, we trace two aspects of the public debate in relation to PISA and educational research. In a first instance, we map the occurrence of references to PISA and to educational research over time. In the second instance, we study how PISA and educational research are used to legitimise or delegitimise certain positions, decisions and reforms in media and in parliamentary debates.

Methodology

The study is based on two data searches: one media search, reduced to covering the eight largest Swedish newspapers (data source: Retriever Mediaarkivet), and one covering protocols from parliament debates (data source: Sveriges Riksdag open data).

We conducted a content analysis noting the distribution of articles/protocols over time, and categorised them with respect to their content, based on their main arguments. The content analysis was then used as a point of departure for a further analysis, in which we analysed whether the references to PISA or educational research were used mainly in an externalising (legitimising) way, or whether the references was used in a way that actually indicated an interest in learning something from PISA or from educational research.

3

Data sources

As mentioned, we use two sets of data: media sources and parliamentary debates. The media

search aimed to find all published education-related articles from 2000 to 2016 that made

references to both PISA and scientific research. The final data material comprises 380 articles.

In parliamentary protocols from 2001 to 2017, we searched the occurrence of the terms

‘PISA’ (used in 151 parliamentary debates) and ‘educational research’ [pedagogisk forskning] (mentioned in 27 parliamentary protocols). In each debate PISA or educational research are used several times. For example, in a debate on the national budget, several political parties referred to falling PISA scores to encourage different but specific reforms. In total, our analysis is based on more than 800 uses of these terms in Parliament.

Our preliminary analyses have shown that references to PISA in the education debate peaked during the elections in Sweden in 2014. To see whether this intensification repeats, we will conduct an additional data search and analysis to include the elections that will take place in Sweden in September 2018.

Preliminary results and conclusions

The political context in which our results are to be interpreted is the parliamentary situation in Sweden, where the Social Democrat party was in government from 2000–2006, followed by a coalition between liberals and conservatives (Folkpartiet, Centerpartiet, Kristdemokraterna and Moderaterna) in 2006–2014 and, finally, a new Social democratic government in

coalition with the Green party (Miljöpartiet) since 2014. During this period, the PISA results in mathematics, reading and science declined from 2000 to 2012, from average/above average to below the OECD average. In PISA 2015, the results for all subject areas were back at the OECD average.

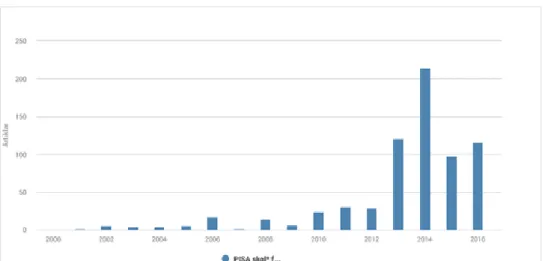

In both the parliamentary protocols and in the media articles up to 2016, we find an increasing number of articles mentioning both ‘PISA’ and ‘scientific research’. The number peaked during the Swedish election year 2014 and declined thereafter, but to a proportionately high number (Figures 1 and 2). The additional results from 2017 and 2018 will show whether this trend is ongoing or has changed.

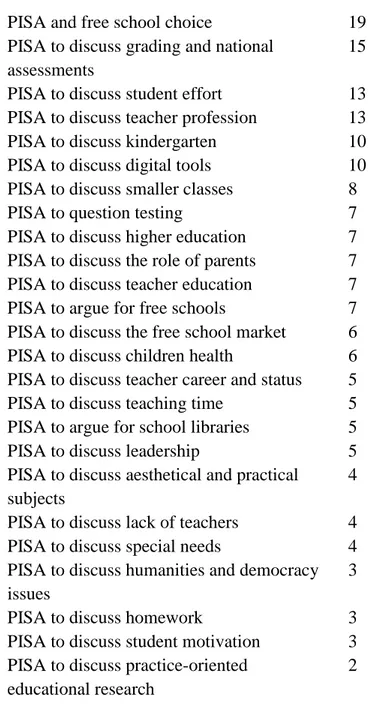

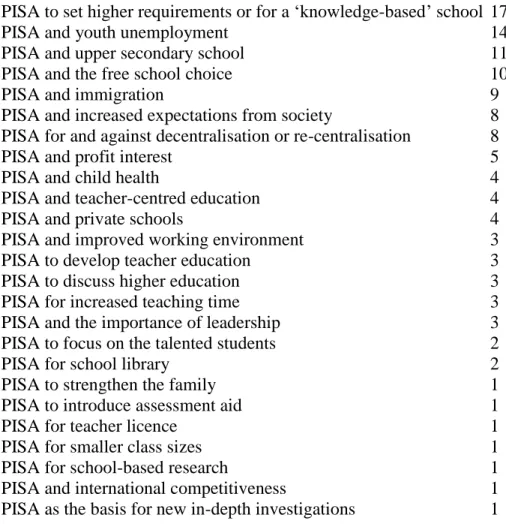

Our content analysis provides a picture of what topics that have been mobilised into the education debate until recently, using PISA results as an argument for or against various school-related causes. We view this as a way for the authors/politicians to legitimise or delegitimise various reforms or actions. Unsurprisingly, the overall picture is that more and more topics were added so that more or less all subjects related to school could be debated under the PISA umbrella by the end of period. The most frequent topics are shown in Tables 1

4 and 2. We see that PISA has been used as an argument for around 40 different causes, and more often related to national party politics than to an actual attempt to learn from other countries. Thus, we find that the PISA references have clear political colour, but so do the references to educational research. In the material, we note that the left-wing parties regularly refer to educational research as a valid knowledge source, whereas this is not the case for the conservative parties.

The references to educational research increase slightly, but much less than the references to PISA. If/when researchers are referred to in the debate, educational researchers appear as less legitimate than researchers from other fields, such as scholars in economics or neuroscience. Educational researchers who have tried to stress critical points about matters such as PISA have been severely criticised in the debate.

We have not found evidence of pure post-truth actions or arguments, but a highly selective use of PISA data and of educational research. As stated, it is related to national party politics where, for example, Social Democrats refer to PISA to refute demands on tax cuts, whereas the conservatives can refer to PISA in a plea for control and accountability reforms.

Generally, we find that PISA is mainly used to point at problems, not solutions.

Comparing the uses of PISA and of educational research in the debate, it is clear that PISA becomes an increasingly convenient externalisation that can be selectively used for almost any educational cause. It is seldom used as learning from others, but rather to strengthen the legitimacy of traditional Swedish educational right- or left-wing politics in education. At the same time, educational research becomes less convenient than PISA to use as an

externalisation (even if the Left Party still does). Rather, educational research becomes an object of politics in itself. Our analysis shows that instead of valuing different sources of knowledge as just that – different – the political education debate has turned into a questioning of their legitimacy.

Scientific and scholarly significance of the study or work

As noted in our introduction, post-truth is also about ‘misspeaking’, ‘exaggerating’ and ‘exercising poor judgement’ acted out in an ethical twilight zone (Keyes 2004). In a recent interview, Bruno Latour (in de Vrieze 2017) was asked to “explain the rise of antiscientific thinking and ‘alternative facts’”. He replied:

To have common facts, you need a common reality. This needs to be instituted in church, classes, decent journalism, peer review. … It is not about posttruth, it is about the fact that large groups of people are living in a different world with different realities,

where the climate is not changing. http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2017/10/latour-qa

The ‘selective truths’ that we identify in our study are not just a matter of antiscientific thinking; they are ultimately a matter of ethics and how ethical institutions such as

5 government, research and media, which were formerly closely bound together, have

de-coupled and started to produce different ethic realities. We argue that we as researchers in the social sciences, have an overarching responsibility to realise, understand and comprehend these different realities and restore faith in research and challenge selective uses of truths. This is a major challenge, methodologically, theoretically and even socially. Researchers will always have to accept the selective and legitimating strategic use of their data by others, but science also has a politics of its own; a politics of transparency when it comes to production, interpretation and uses of facts and knowledge. Such is the ethics of science.

References

Andersen, J. A. 2009. Organisasjonsteori. Fra argument og motargument til kunnskap. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

Bieber, T., and Martens, K. 2011. “The OECD PISA Study as a Soft Power in Education? Lessons from Switzerland and the US.” European Journal of Education, 46 (1): 101–116.

Breakspear, S. 2012, “The Policy Impact of PISA: An Exploration of the Normative Effects of International Benchmarking in School System Performance.” OECD Education Working Papers, No. 71, OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5k9fdfqffr28-en

De Vrieze, J. 2017. “Bruno Latour, a veteran of the ‘science wars,’ has a new mission.” http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2017/10/latour-qa

Higgins, K. 2016. “Post-truth – a guide for the perplexed.” Nature, 540(7631), https://doi.org/10.1038/540009a

Hultqvist, E., Lindblad, S., and Popkewitz, T. S. 2018. Critical Analyses of Educational Reforms in an Era of Transnational Governance. Switzerland: Springer.

Keyes, R. (2004). The Post-Truth Era: Dishonesty and Deception in Contemporary Life. New York: St Martin’s Press.

Oxford Dictionaries. 2016. https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/word-of-the-year/word-of-the-year-2016. Pizmony-Levy, O., & Bjorklund Jr, P. (2018). International assessments of student achievement and

public confidence in education: evidence from a cross-national study. Oxford Review of Education, 44(2), 239–257.

Schriewer, J. and Holmes, B. (eds) 1988. Theories and Methods in Comparative Education, Frankfurt am Main etc.: Peter Lang.

Schriewer, J. and Martinez, C. 2004. “Constructions of Internationality in Education.” In The Global Politics of Educational Borrowing and Lending, edited by Steiner-Khamsi, G. New York: Teachers College Press.

Steiner-Khamsi, G. and Waldow, F. 2012. World Yearbook of Education 2012: Policy borrowing and lending in education, London: Routledge.

6 Waldow, F. 2017. “Projecting images of the ‘good’ and the ‘bad school’: top scorers in educational

large-scale assessments as reference societies.” Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, DOI: 10.1080/03057925.2016.1262245

Figures and tables

Figure 1. Number of articles found in media search up to 2016 (total 695). Source: Retriever Mediaarkivet.

Figure 2. Number of parliamentary debates (N = 176) where the term PISA is used in the 2001/02 to 2016/17 (quarter 1). All parliamentary debate protocols since 1971 have been digitalised; thus, the increase in references to PISA reflects an actual change.

Nodes Number of items

coded

PISA to discuss equity 33

PISA to discuss PISA ranking 20

0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45 2001/02 2002/02 2003 /04 2004/05 2005/06 2006/07 2007/08 2008/09 2009/10 2010/11 2011/12 2012/13 2013/14 2014/15 2015/16 2016/17( q 1) Riksdagsår

Parliamentary debates

7

PISA and free school choice 19

PISA to discuss grading and national assessments

15 PISA to discuss student effort 13 PISA to discuss teacher profession 13

PISA to discuss kindergarten 10

PISA to discuss digital tools 10 PISA to discuss smaller classes 8

PISA to question testing 7

PISA to discuss higher education 7 PISA to discuss the role of parents 7 PISA to discuss teacher education 7 PISA to argue for free schools 7 PISA to discuss the free school market 6 PISA to discuss children health 6 PISA to discuss teacher career and status 5 PISA to discuss teaching time 5 PISA to argue for school libraries 5

PISA to discuss leadership 5

PISA to discuss aesthetical and practical subjects

4 PISA to discuss lack of teachers 4 PISA to discuss special needs 4 PISA to discuss humanities and democracy issues

3

PISA to discuss homework 3

PISA to discuss student motivation 3 PISA to discuss practice-oriented

educational research

2

Table 1. Number of press articles coded in which PISA has been used to argue for or against various school-related causes. 2000-2015. Encoding completed with NVivo 11.0.

Nodes Number of coding references

PISA for increased equivalence in education 59

PISA to focus on the teachers 45

PISA in order not to lower the taxes but invest more in education 26

PISA for early grading 23

PISA for increased order and discipline 22

PISA for students in need of support 21

PISA and digital skills 20

8 PISA to set higher requirements or for a ‘knowledge-based’ school 17

PISA and youth unemployment 14

PISA and upper secondary school 11

PISA and the free school choice 10

PISA and immigration 9

PISA and increased expectations from society 8 PISA for and against decentralisation or re-centralisation 8

PISA and profit interest 5

PISA and child health 4

PISA and teacher-centred education 4

PISA and private schools 4

PISA and improved working environment 3

PISA to develop teacher education 3

PISA to discuss higher education 3

PISA for increased teaching time 3

PISA and the importance of leadership 3

PISA to focus on the talented students 2

PISA for school library 2

PISA to strengthen the family 1

PISA to introduce assessment aid 1

PISA for teacher licence 1

PISA for smaller class sizes 1

PISA for school-based research 1

PISA and international competitiveness 1

PISA as the basis for new in-depth investigations 1 Total number of coding references 356

Table 2. How often PISA has been used to argue for (and occasionally against) specific reforms and other political measures, 2002–2017 (quarter 1). Encoding completed with NVivo 11.0.