TRACKING THE FOOTBALLING SELF

An ethnography of the tensions between analog and digital expertise in a football team’s self-tracking practices

Author Eveliina Parikka Supervisor Martin Berg Examiner Suzan Boztepe

Media Technology: Strategic Media Development Master’s Program Thesis, 15 credits, advanced level

Abstract

In the digitally mediated world that we live in, self-tracking and monitoring technologies have been observed to become part of the various realms of our social lives, shaping and even disturbing relations that we take part in. This thesis has sought to explore how tensions emerge between digital tracking technologies, players and other human members of an elite football team and, thus, to address how those tensions are dealt with. By applying the ethnographic research methodology and adopting the theoretical framework of Actor-Network Theory (ANT), the study has pursued to investigate how the technologies participate in the players’ everyday practices as well as how the players navigate between the expertise of different human and non-human sources in the team. The results indicate that the involvement of tracking technologies can increase the possibility of tensions to arise between different participants in a network such as the studied football team. To deal with these tensions, this thesis has contributed with a prototype of a system around a player monitoring technology. It suggests roles, relations, factors and actions in order to enhance the understanding among those who manage such a technology, helping them to acknowledge and overcome possible tensions in the social process of tracking a football team. This service blueprint is constructed through co-design workshops together with the player participants.

Acknowledgments

Before delving into the world of intertwined relations between tracking technologies and elite athletes, I would like to thank those who have supported my efforts to conquer this thesis project. First, I owe my supervisor, Martin Berg, a debt of gratitude for offering ever so understanding and firm guidance for my work. Your belief in me and my abilities has kept me pursuing my personal best. To my family, that has stood behind me, helping me through the anxiety and struggle, encouraging me in the smallest breakthroughs and success: thank you from the bottom of my heart. Last but not least, I am beyond grateful for my friends, teammates, and classmates, who have contributed to the project in so many ways. You guys have provided me love, support, care, and, I must say, endless patience throughout one of the most challenging missions in my life. Thank you!

Table of contents

1 Introduction ... 1

1.1 Aim of the study ... 4

1.2 Research question ... 4

2 Literature review ... 6

3 Theory and methodology ... 13

3.1 Actor-Network Theory ... 13

3.1.1 Agency of non-human actors ... 16

3.1.2 Translations between human and non-human actors ... 18

3.2 Ethnography ... 20

3.3 Data collection procedures ... 22

3.3.1 Digital autoethnography, reflective diary and self-observation ... 23

3.3.2 Participant observation ... 24

3.3.3 Semi-structured interviews ... 26

3.3.4 Service design and co-design ... 27

3.4 Sampling, participants and site ... 29

3.4.1 Tracking technologies used by the researcher and by the participants ... 30

3.5 Analysis ... 32

3.6 Ethical considerations ... 33

3.7 Delimitations ... 34

4 Findings ... 36

4.1 Becoming part of the players’ everyday lives ... 37

4.1.1 Feeling the data in daily activities ... 38

4.1.2 Adding meaning to the athletic activities ... 44

4.2 Navigating between different analog and digital expertise ... 50

4.2.1 From a device to a player and back ... 50

4.2.2 The self, devices and other members of the team ... 56

4.3.1 Individual aspects of tensions ... 61

4.3.2 Collective aspects of tensions ... 63

5 Analysis & discussion ... 68

5.1 Agential roles of tracking technologies ... 68

5.2 Connections between players, technologies and coaches ... 71

5.3 Tensions as disturbed translations ... 77

6 The prototype ... 83

6.1. Individual workshops: Brainstorming with paper models ... 83

6.2 Focus group workshop: Problem-solving through storyboarding ... 85

6.3 Prototyping the system into a blueprint ... 90

7 Conclusion ... 95

References ... 96

Appendix A: Interview questions ... 102

Appendix B: The participants ... 103

List of figures

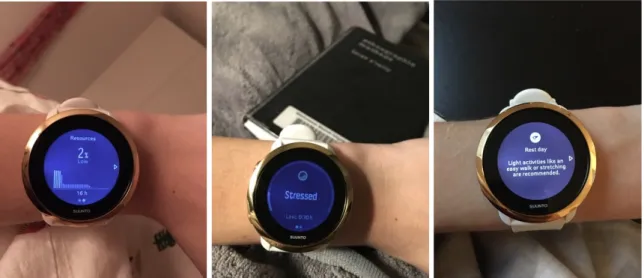

Figure 1. Nova and Leila interacting with their sleep and activity data ... 39

Figure 2. The researcher’s sports watch displaying recovery-stress data ... 41

Figure 3. Maya helping Josephine to place the GPS pod into the tracking vest ... 45

Figure 4. Freya and Anna interacting with their data after training ... 54

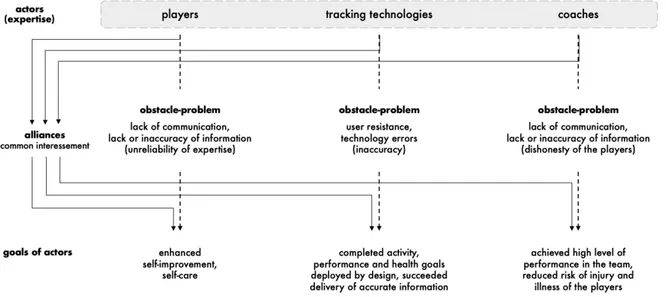

Figure 5. System of alliances between the network actors ... 74

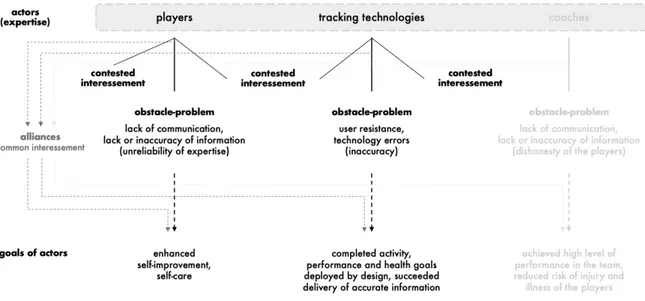

Figure 6. Emergence of tensions between players and technologies ... 78

Figure 7. Emergence of tensions between players, technologies and coaches ... 80

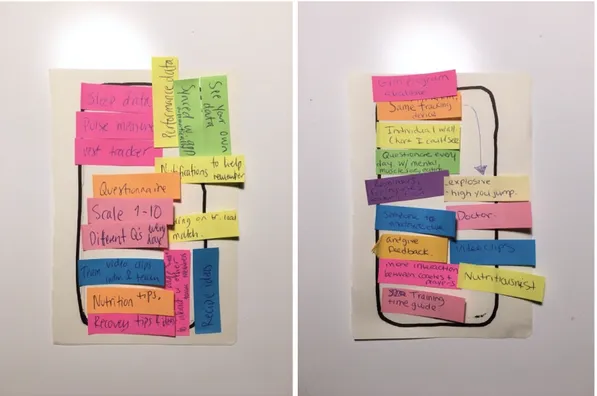

Figure 8. Players brainstorming during the individual workshops ... 84

Figure 9. Paper model designs done by the players ... 85

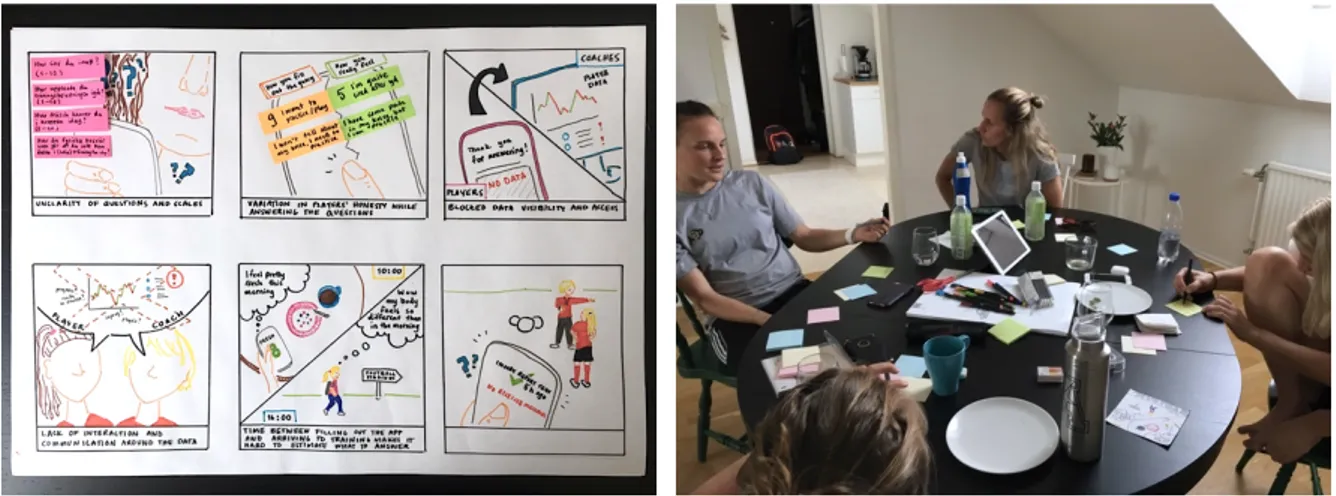

Figure 10. The problem cards ... 86

Figure 11. The focus group solving a problem ... 86

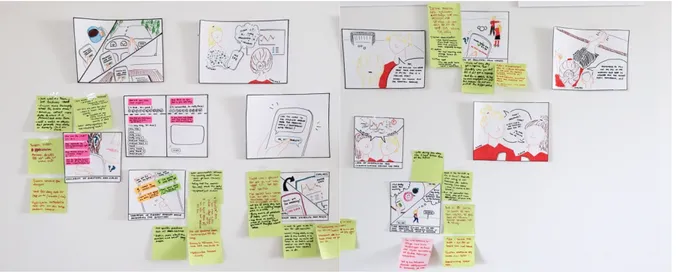

Figure 12. The storyboard, problem cards and solutions in post-it notes ... 87

Figure 13. The service blueprint ... 92

1 Introduction

Behind the rooftop window, the sun has slowly started to set. I recall my coach’s words from two days ago, stressing how I should do nothing this weekend, no training whatsoever. I glance at my watch and start pushing the buttons to navigate through the interface, ending up scrolling down the training log. The device has planned a hard training of 30 minutes for today. I ignore it, the watch should know better. We have had a whole week of intense football practices, and I have kept my focus on prioritizing recovery during these off-days – just like the coach told me to. There is no need to exercise. I know this.

I check my recovery time; zero hours. Good.

As I set myself on the sofa, a beam of sunlight touches my face. The warmth of it cannot reach my cheeks through the glass. I feel an urge to take a brisk stroll. Come to think of it, my watch also needs to be calibrated. Hitting the buttons again I find instructions; calibration can be done by recording a short walking exercise. Sounds easy. And I do feel fresh. The coach will not mind if I just walk, right?

(Personal communication, February 24, 2019)

As a player in an elite football team, I am constantly surrounded by different voices of expertise. Coaches plan, decide and communicate how often, how intense, how long and what way we players practice, they give us feedback on how we perform, tell us when to rest and advice how to recover. Medical staff directs the players on how to load and take care of our bodies or to treat injuries, whereas a sports psychologist might help to organize one’s thoughts right. We players, above all, influence ourselves and each other by reflecting on our bodily experiences and by sharing knowledge on how to be better football players. Simultaneously, the scope of digitalization extends to the team locker room, bringing in voices of different technologies that track our bodies and minds, turning them into data, while guiding the players individually or even the team collectively. From a socio-material perspective, such tracking technologies and practices tend to become part of people’s everyday lives by engaging in the social dimensions, bringing together diverse actors – human and non-human, analog and digital (Lupton & Smith, 2018). However, sometimes these different actors present information that is contradicting to the players, making them navigate, evaluate, balance and decide between the sources of

expertise and what of their knowledge to absorb, follow or use. As an effort, this is not only mentally demanding but can create situations that challenge the social relations between the different actors.

Since the early days of initial monitoring techniques and wearable technologies which first enthusiasts experimented with on themselves in the 1990s, the landscape of self-tracking practices has expanded further into the various aspects of human life. The rise of digitalization and datafication (Schäfer & van Es, 2017) has boosted the development of technology, providing both consumers and professionals with easier access to diverse devices than ever before (Lupton, 2016). Equipped with sensors or other features of digital tracking, these wearable technologies are automatized to constantly gather data of people’s bodily functions and guide their daily actions. Indeed, today’s self-trackers operate in a wide range of different fields – from health, sports, education, culture and entertainment to economy, politics and so on – giving new purposes and meanings to technologies and data through their everyday activities (Lupton, 2016). In research, the growing interest in monitored reflection, self-care and self-improvement practices has gradually shifted the focus from merely studying people’s engagement with different technologies to in-depth explorations of the social, narrative and affective dimensions of self-tracking cultures (e.g. Fiore-Gartland & Neff, 2015; Lomborg & Frandsen, 2016; Smith & Vonthethoff, 2017). However, few studies have yet been published on the possible points of tension or internal contradiction related to self-tracking (Ruckenstein & Shüll, 2017).

The motivation for this thesis to study possible tensions between human and non-human expertise has been evolved from the first participant observations I did with the team of female football players under study. By entering the research field with an idea to investigate the social aspects of the players’ self-tracking practices, I noticed that the coexistence of different analog

and digital expertise enabled the team members to interpret and use player-generated data in diverse ways. Some of these situations were observed to result in temporary, yet recurring, tensions within the team, among and between its members and technologies, raising questions such as: How do the players experience the coexistence of different analog and digital expertise? What kinds of roles do self-tracking technologies play in the state of affairs? How the players navigate between different expertise? How the possible tensions around these expertise are dealt with?

In this study, the term ‘expertise’ describes an organized body of specialized knowledge that has been acquired through extended learning and experience (Chi, Glaser & Farr, 1988). An expert, in this sense, often displays more ability in particular domains of knowledge and skill (Chi, Glaser & Farr, 1988). Whether the expertise is demonstrated through a player’s motor skills and experience of athletic body, a coach’s understanding of the varied aspects of football or a tracking device’s ability to display biometric insights, the actors are considered to carry out combinations of expertise that are put into work through different means of expression, like performances, discourses or technological designs and features. While the different expertise come to act together in the common practices of the football team, it is not given that they always resonate with each other. The term ‘tension’, thus, is understood and used as the New Oxford American Dictionary (2010) defines it: “a relationship between ideas or qualities with conflicting demands or implications”. Simply, tension means contradiction in how actors think or feel about, interpret, expound or execute a shared matter or a situation through their expertise. That is, this thesis is an ethnographic study that investigates how tensions, if any, come to emerge between different human and non-human actors within an elite-level football team and how those tensions are dealt with. The socio-material perspective adopted in this thesis has been supported by using Actor-Network Theory as the theoretical framework. The methodological and theoretical tools of choice have allowed the researcher to approach digital

technologies as social actors. By co-designing together with the research participants, a prototype has been created into a form of a service blueprint. This blueprint aims to illustrate a system around a monitoring technology for the purpose of acknowledging and overcoming possible tensions in the social process of tracking team athletes.

1.1 Aim of the study

This study aims to investigate how tensions, if any, can emerge between players, digital tracking technologies and other team members, as they act and intertwine within the same football team. To reveal how the players deal with these tensions, the thesis focuses on exploring the ways self-tracking technologies and practices take part in the players’ everyday lives and in the process of the players navigating between their own, the technologies’ and other team members’ expertise.

1.2 Research question

The goal for this study will be achieved by exploring the aspects defined in the overall research question. In order to investigate these aspects in more detail, sub-questions have been added to structure the study. The research questions are designed as follows:

Overall research question: How do players deal with tensions between different analog and

digital expertise existing within their football team?

Sub-questions:

- How do digital self-tracking technologies and data become part of players’ athletic everyday lives?

Next, the study proceeds to introduce the existing literature as well as the theoretical framework and the methodological means adopted in the project. As the text moves further, the research questions presented above will be approached and addressed by unveiling the different empirical and analytical dimensions produced through this research.

2 Literature review

Self-monitoring has become a common practice with the emergence of digitized, wearable technologies. Diverse devices and mobile applications, such as sensored bracelets and sports watches as well as health, fitness and wellness applications, enable people to observe and record details of their bodies and lives to achieve self-knowledge, self-reflection, self-improvement, and self-care (Lupton, 2014; Nafus & Neff, 2016). Prior to the development and expansion of these technologies, self-tracking was practiced by computing engineers in the 1990s, who started the experiments of monitoring different aspects of their own lives through the early ‘wearables’ they invented (Lupton, 2016). And yet, the traditional forms of tracking one’s own life, such as keeping a journal or writing a diary, are ages-old strategies (Lupton, 2014).

Over the years and along with the technological development, self-tracking practices have been described with a variety of names: lifelogging, personal informatics, personal analytics, self-quantification. Today, many social scientists talk about the ‘quantified self’ movement (Christiansen, Kristensen & Larsen, 2018; Kristensen & Ruckenstein, 2018; Lupton, 2016; Pink & Fors, 2017b; Schüll, 2016). It is a popular term used to describe not only an international community of enthusiasts who use and make self-tracking tools in order to share those experiences with each other (Quantified Self, 2015) but also the various ways people practice self-monitoring in the current age. The emergence of the Quantified Self (QS) community dates back to 2007. Back then, two former editors of the Wired magazine created the foundation for this collective that today gathers people together to share their self-tracking projects and experiments in online forums and arranged meetings around the world (Bode & Kristensen, 2016; Quantified Self, 2015). According to Kristensen and Ruckenstein (2018), the QS community has developed into “a rich ethnographic site for thinking about this co-evolving and the contributions made by technologies to the shaping and modeling of human aims and values, and the capacities and collaborations that define them” (p. 3625). That is, the

community has both become a source of inspiration for several recent studies (e.g. Lupton, 2016; Pink & Fors, 2017b; Ruckenstein & Pantzar, 2015) and sparked the use of the term ‘quantified self’ in characterizing the current trend of self-tracking.

Self-tracking involves individuals using and engaging with digital technologies to monitor, measure and analyze themselves, their bodies, behavior and the diverse aspects of their active lives (Lupton, 2015; Pink & Fors, 2017b). Lupton (2015) states that all forms of self-tracking consist of data practices, yet not all practices are based on merely numerical metrics. The ways people generate, collect, engage with and interpret their personal data relate to how they develop individual insights from both quantitative and qualitative forms of information. Thus, self-tracking is strongly associated with reflexivity. According to Lupton (2014), the data that people generate through self-tracking can be seen as pedagogical and motivational because the technologies and the practices around them are designed to achieve behavioral change in their users. By reflecting on the data they collect of themselves, people work towards “the goal of becoming” (Lupton, 2014, p. 12) – becoming more fit, healthy, aware, or, in some other way, better versions of themselves.

That is, self-tracking is theorized and conceptualized by many as a form of embodiment and a practice of selfhood. People experience the world with and through their bodies, as embodied subjects learning and acting, as well as responding to other bodies and objects with their emotions and senses (Lupton, 2017). Today, embodiment is mediated through digital technologies, such as monitoring devices and data, that people regularly carry on or with them and that generate new meanings of their being in the social world (Lupton, 2017). According to Lupton (2014) self-tracking “conforms to cultural expectations concerning the importance of self-awareness, reflection and taking responsibility for managing, governing oneself and improving one’s life chances” (p. 12). Adopting a Foucauldian perspective (Foucault, 1988), she argues that self-tracking cultures build on practices of collecting, interpreting and reflecting

on data of the self to reach the goal of becoming, and, furthermore, achieving the ideal version of the self, accorded with the contemporary ideas of good citizenship. Both Ruckenstein and Pantzar (2015) as well as Lomborg and Frandsen (2016) observe that self-tracking devices and data shape the ways of seeing, understanding and expressing the self. They suggest that in addition to selves, bodies, and socialites, these technologies affect communication and learning. In turn, Kristensen and Ruckenstein (2018) see self-tracking practices as part of the transformation of self-experience, operating as a laboratory of the body and self in which “the relevant technologies are used as resources and collaborative possibilities in the course of self-making and self-improvement” (p. 3625-3626). Their study on the Danish QS community observes how people co-evolve with self-tracking technologies. They demonstrate how the self, emerged through and brought to the fore by tracking practices, may be used to explore the co-developing and coupling of human and non-human actors.

Building on the idea of the entanglements between humans and technologies, scholars in anthropology, sociology, science and technology studies, as well as media and communication studies have recently focused on examining self-tracking and data practices in the context of health. In the Annual Review of Anthropology: Datafication of Health, Ruckenstein and Shüll (2017) separate three thematic clusters – ‘datafied power’, ‘living with data’ and ‘data-human mediations’ – to characterize the recent research work in the field of self-monitoring. Many scholars have paid attention to the asymmetric power relations between those who collect data and those who are targeted by data collection (e.g. Andrejevic & Burdon, 2015; Crawford, Lingel & Karppi, 2015; Van Dijck, 2014). In turn, a growing collection of ethnographic studies have drawn attention to how a more intimate level of surveillance, sociality, making, and experiential aspects of datafication are practiced through self-tracking (e.g. Fiore-Gartland & Neff, 2015; Kristensen & Ruckenstein, 2018; Smith, 2016; Timan & Albrechtslund, 2015). Enhancing the mediating power of non-human components,

scholarships in science and technology studies and media studies have instead focused on how digital devices, algorithms, data infrastructure, data itself, as well as the processes and practices around them act in relation to human actors (e.g. Berg, 2017; Pink & Fors, 2017a; Schüll, 2016).

However, few studies have yet been published (e.g. Bode & Kristensen, 2016; Bloomfield, 1991; Fiore-Gartland & Neff, 2015) on the possible points of tension between people and monitoring technologies or internal contradiction in the context of tracking the self and, let alone, related to elite team sports (Lupton, 2016; Millington & Millington, 2015; Ruckenstein & Shüll, 2017). For instance, Fiore-Gartland and Neff (2015) discover that tensions emerge among people in formal health care institutions, consumer health and wellness communities due to different expectations the stakeholders have for the same data. Observations like this are important for my thesis in reasoning why tensions possibly arise in human and non-human interactions. However, the existing research has mainly focused on data and its or devices’ roles as objects, rather than positioning monitoring technologies as social actors that participate in and shape the processes where tensions can arise. Neither do they go deeper into the aspects of how people deal with the tensions.

In the case of health, self-tracking technologies and practices have been noticed to render human bodies observable to a broader assemblage of different actors than before, constructing private lives as objects of surveillance and persuasion, yet harnessing individuals with new kind of information and expertise. As Lupton (2012) states:

The notion of patients placing themselves under the care of a doctor and seeking their expert advice has moved to the concept of patients as producing health knowledges and as acquiring expert knowledge so as to manage their illness themselves. (p. 233)

At the same time, various actors and agencies from health care professionals to technology designers are granted remote access to these private domains of people. Lupton (2012) argues that digital tracking tools do not only pose as an example of the medical gaze but

more generally of the surveillance society we live in. This notion of transforming health care into self-care constructs of subjecting oneself to data tracking and thus performing ideal, healthy and desirable citizenship (Ajana, 2017; Lupton, 2012; Nafus & Neff, 2016; Ruckenstein & Shüll, 2017). In sports, this could be translated into living by the rules of desirable athleticism. As athlete monitoring has become a common practice in today’s high-performance sports, digital tools and athlete-generated data enable athletes themselves to reflect on their performances and coaches to improve the training process, enhancing athletes’ readiness to perform and reducing injury risk (Kellmann & Beckmann, 2017).

Like many other scholars (e.g. Lupton, 2014; Rose, 2001; 2007; Schüll, 2016), Ajana (2017) refers to Michel Foucault (1978) when using the term biopolitics to describe this data-driven aspect of control over oneself and population. Biopolitics is “the mechanisms, techniques, technologies and rationalities that are put at work for the purpose of managing life and the living, and governing their everyday affairs” (Ajana, 2017, p. 5) through the power enacted upon human body. In relation to biopolitics, biomedicalization, as Nafus and Neff (2016) call the recent cultural change in the development of self-tracking, demonstrates how “it is now hard to find corners of life that are not subject to biomedical interpretation, from moods to feelings to life success itself” (p. 18-19). This has observed to add social pressure on people who track themselves, to live by the rules of healthy and efficient life. Albeit many researchers have adopted the Foucauldian perspective in studying self-tracking, this thesis will take another approach from the aspects of biopolitics and biomedicalization, focusing on the ways tracking technologies transform into social actors and practices around them become part of people’s everyday lives.

According to Ruckenstein and Shüll (2017), the methods and practice-based analysis of ethnography can enhance a more comprehensive understandings of how self-tracking technologies and data “are taken up, enacted and sometimes repurposed” (p. 265). A range of

ethnographic studies has observed self-tracking practices and experiences to immerse into the social, narrative and affective aspects of people’s daily lives. In their study on communication, mediation and expectations of data within health and wellness communities, Fiore-Gartland and Neff (2015) report tensions around “how different people talk about what they want from data and how they expect that data to perform in interaction with others” (p. 1467). In this sense, data can be expected to work variously in the use of different actors, across social settings and interactions. For instance, a doctor may want a patient to track oneself to expand the information about the patient’s condition. The patient, in turn, may this way feel more informed, cared and secure about the decision-making process related to one’s body. However, the health care process can be simultaneously complicated and prolonged due to the possibility that the data gets interpreted differently from the professional and amateur perspectives (Fiore-Gartland & Neff, 2015).

In the context of day-to-day practices and through data, people are also observed to reflect on their bodies in experiential and emotional ways – feeling the data rather than living by the metrics (Pantzar & Ruckenstein, 2017). By studying how people engage with their personal stress and recovery measurements, Pantzar and Ruckenstein (2017) demonstrate that data changes constantly with different values and interpretative forces: “The understandings of physiological measurements are informed by various types of expertise, personal and professional, and the interpretations are flexible, contextual and idiosyncratic” (p. 7). Both Fiore-Gartland and Neff’s as well as Pantzar and Ruckenstein’s findings concern narrative and social aspects that are important for this thesis in exploring how players navigate between analog and digital expertise and how technologies participate in shaping the dynamics of the social relations in the team. Yet, these studies leave room for deeper investigations of the ways these entanglements between human and non-human may be challenged or disturbed.

Shüll (2017), instead, finds in her research that most self-trackers engage digital devices with ambivalence, wishing both to take charge of themselves and to delegate the task to these technologies. She observes a tendency in people’s willingness to feel cared for by their devices. That is, digital tracking technologies and their algorithmic power are observed to be used not only to detect and predict but also to modify human behavior (Ruckenstein and Shüll, 2017). As Kettunen, Kari, Makkonen, and Critchley (2018) refer to ‘digital coaching’ in their research on tracking devices and athletes’ self-efficacy, the newest realm of sports and wellness technologies does not just aim to improve people’s awareness based on their activity data, but tends to learn about their users in more comprehensive ways by, for instance, generating adaptive training plans based on the information received from the users – acting as real-life digital coaches. Indeed, Lupton (2012) argues that, from the perspective of socio-cultural studies of science and technology, self-tracking technologies “are viewed as ‘actants’ in a network of configuration in which non-human objects are viewed as equally as agential as are humans” (p. 232). She states that just as people incorporate technologies into their everyday practices by shaping and giving them meanings, these digital devices bestow meaning and subjectivity upon their users.

This thesis adopts an approach that positions technologies alongside people in being able to create and transform social relations. In studying how the connections between human and non-human come to form, how they are navigated and, especially in the case of this research, disturbed, I have chosen to employ methodological and analytical tools that allow the research to expand the scope of social actors and their agencies. The next chapter will explain the theory and methodology adopted in this study.

3 Theory and methodology

This thesis aims to understand the coexistence of different analog and digital expertise, human and non-human actors, within the everyday life of the studied football team and the players’ self-tracking practices. Above all, it has investigated the tensions around these expertise, experienced by the players. This thesis adopts ethnography as the research methodology and works in the theoretical framework of Actor-Network Theory (ANT). In the context of the study, the combination of ethnography and ANT provides a competent way to investigate a culture where human and non-human entities intertwine, allowing technologies to be seen as social actors that actively participate in people’s lives. I have chosen to apply these two in order to derive and analyze results from real-life situations, activities, and experiences.

3.1 Actor-Network Theory

As the central idea of Actor-Network Theory is to understand connections that link human and non-human actors (Desai et al., 2017), it provides a useful theoretical framework and a conceptual approach to be applied in the ethnographic way of studying interactions between team athletes and digital tracking devices. Evolved from the work of Bruno Latour (2005), Michel Callon (1986) and John Law (1986), ANT is seen as a set of both theoretical and practical methods for tracing how the connections between different actors come to be formed, what holds those connections together, what is produced through them and, thus, how this process constructs or fails to construct social networks that constitute the world (Cresswell, Worth & Sheikh, 2010). In its simplicity, ANT is an approach for mapping how technologies participate in people’s everyday lives (Cresswell et al., 2010; Macleod, Cameron, Ajjawi, Kits & Tummons, 2019).

Latour (2005) characterizes Actor-Network Theory with three principle ideas; that of, non-human actors can possess an equally active role as humans in shaping social processes,

that the social is not a stable process but rather reforms continuously in relation to the connections between different network actors, and that before the social can be reassembled, it must go through dispersion, destruction, and deconstruction.

ANT sees social life as an outcome of interactions between human and non-human entities, that everything existing in the world “is made up through a wide variety of shifting associations (and dissociations)” where different actors – like people and technologies – constitute each other mutually (Prout, 1996, p. 200). An actor is viewed as “the source of an action, regardless of its status as a human or non-human” (Doolin & Lowe, 2002, p. 72). However, an actor always needs other actors in order to be able to act. In Actor-Network Theory, non-human actors are endowed with the agency to transform, as well as to be transformed by, the action of other actors (Desai et al., 2017; Latour, 2005). Instead of viewing technologies merely as an external force impacting on humans, ANT considers digital devices to be able to interact with people in dynamic relationships (Cresswell et al., 2010; Latour, 2005). According to Latour (2005), “the most powerful insight of social sciences is that other agencies, over which we have no control, make us do things” (p. 50). These agencies, as van Dijck (2013) argues, are involved in shaping the interactive process between people and technology, “a process characterized by contingency and interpretive flexibility” (p. 26).

Indeed, a key activity for ANT researcher is to trace connections, associations or relationships between different network actors (Cresswell et al., 2010). Through these discovered links, ANT can be used to theorize about:

How networks come into being, to trace what associations exist, how they move, how actors are enrolled into a network, how parts of a network form a whole network and how networks achieve temporary stability (or conversely why some new connections may form networks that are unstable). (Cresswell et al., 2010, p. 2)

That is, ANT considers social world primarily uncertain and unstable, since it assumes that the functioning of a network will be affected if any actor is moved around, removed from

or added to that network (Callon, 1986; Latour, 2005). This means that networks are constantly evolving in relation to the movements of actors, their agencies and connections with each other and can achieve only momentarily stability (Callon, 1986; Cresswell et al., 2010). According to Ruckenstein (2015), self-tracking technologies tend to become part of people’s social practices in seeing, treating and communicating with other people, allowing them to assess and broaden their sphere of influence and activity: “When people do things, they are not subjects separate from objects, but part of chains that distribute competences and actions” (p. 32). In studying a network where human expertise, presented in a form of players and coaches, interact with non-human expertise of digital tracking devices, ANT can be used to gain understanding of how different actors experience and enact different realities and, thus, to uncover the dynamics of these relations in a more extensive way (Cresswell et al., 2010). For instance, as Cresswell et al. (2010) suggest, ANT is a tool for examining how power relations may change in situations where people interact with each other in co-operation with digital devices and how active of a role do technologies play in shaping these kinds of social processes. If a digital player monitoring technology, fueled by self-reported data and intended primarily as a tool for coaches to observe players’ physical fatigue and readiness to perform, transforms in the players’ hands into a mediator for them to give a certain impression of their athletic form and wellbeing, who actually holds the power then? How does the power move from one actor to another in different social everyday situations? What kind of tensions does this movement create?

In Actor-Network Theory, a single entity or actor can also be seen as a network, a process of its own (Callon, 1986). By viewing this through the lens of dispersion, destruction, and deconstruction, John Law (1997) demonstrates the network process with the help of his well-known parable of the powerful manager. In the parable, Law disarms the manager from his powers by removing all of the human and non-human actors around him, leaving the manager ‘naked’ and powerless without his computer, phone and other materials from his

office, abandoned from his secretary and colleagues too. The manager is a network that is unable to work, plan, document, communicate, act or manage without its human and non-human entities that these actions, and thus power, are distributed to. By these means, networks are formed and functioned through social and technical relations between different actors that are spread out in the network.

Cresswell et al. (2010, p. 4) argue that “the essential value of ANT lies in challenging assumptions of separation between material and human worlds”. Indeed, many of today’s social encounters take place in the context of digitally mediated everyday life. In the network of the studied football team, the group of actors does not limit to solely human participants but involves non-human technologies that are observed to play an active role in shaping social processes in the team. Thus, in order to reveal these roles, to trace the connections and analyze the relations between players, coaches and different tracking devices, ANT is used in the ethnographic practice of this study by utilizing two conceptual tools characteristic of the approach: agency of non-human actors and translations between human and non-human actors.

3.1.1 Agency of non-human actors

Latour (2005, p. 71) explains and reasons the agency of non-human actors by pointing out that “if action is limited a priori to what ‘intentional’, ‘meaningful’ humans do, it is hard to see how a hammer, a basket, a door closer, a cat, a rug, a mug, a list, or a tag could act.” And yet, hitting a nail with a hammer is not exactly the same activity as hitting a nail without a hammer, neither is shopping for groceries with a basket quite comparable to doing it without a basket. The realizations of the tasks described above are changed by the introduction of the mundane implements, as they transform the course of action of their users and make a difference in the situations they participate in (Latour, 2005). This ability to influence the ways other actors’ act is what grants non-human, as well as human, actors their agency (Latour, 2005). However,

while ANT adopts this perspective of symmetry in theorizing humans and non-humans, it does not necessarily mean that non-human agencies operate as human agencies do (Macleod et al., 2019). This means that as “we posit ontological, epistemological, and methodological symmetry, we refrain from passing judgment on the extent to which this symmetry is concretely actualized” (Macleod et al., 2019, p. 179). Nevertheless, a system of people and things mutually influencing each other is what ANT calls an actor-network, and in and through these patterned networks of heterogeneous materials the social world is being produced (Desai et al., 2017; Prout, 1996).

With the concept of non-human agency, it is possible to follow the traces that technologies leave when they connect and interact with people and other objects. Yet, as Latour (2005, p. 79) points out, non-human “objects, by the very nature of their connections with humans, quickly shift from being mediators to being intermediaries, counting for one or nothing, no matter how internally complicated they might be.” Both intermediaries and mediators can form connections between actors, but the difference between them is that intermediaries transform inputs into predictable whereas mediators into unpredictable outputs (Cresswell et al., 2010). As Cresswell et al. (2010, p. 3) bring to the fore, “ANT assumes that the social world consists of many mediators, which tend to be the focus of analysis as they impact on social outcomes in often unpredictable ways, and very few intermediaries.” Due to their tendency to quickly transform from one into another, non-human actors and their agencies have to be made to talk, “to offer descriptions of themselves, to produce scripts of what they are making others – humans or non-humans – do” (Latour 2005, p. 79), in order to make the traces of their connections with other actors visible. One way to do this is to keep an eye on possible conflicts (or tensions) appearing in the studied network, since “the composition of networks tends to become particularly apparent when things in a system go wrong” (Cresswell et al., 2010, p. 3).

In studying tensions between analog (human) and digital (non-human) expertise (actors) in a network of a football team, the concept of non-human agency can be useful in a couple of ways. To begin with, it helps to address the first sub-question of this thesis – ‘How do digital self-tracking technologies and data become part of the player’s athletic everyday life?’ – by providing a tool for tracing what agencies the tracking devices and data have regarding the players, how these technologies and the players possibly change each others’ actions and, thus, how active roles these technologies come to play through their connections with the players. The concept is also helpful in analyzing how a collectively used player monitoring technology mediates and influences social relationships between different team members. This way, the tool adds insight into understanding the different forces at play in the football team and aids to answer the second sub-question of the thesis: ‘How do players navigate between different analog and digital expertise?’

3.1.2 Translations between human and non-human actors

The translation concept is one of the central tools in Actor-Network Theory. Translation produces phenomena through the ongoing work of different human and non-human actors, fueling the making and remaking of connections between them (Macleod et al., 2019). It is a process before being a result, “during which the identity of actors, the possibility of interaction and the margins of maneuver are negotiated and delimited” (Callon, 1986, p. 201). The actors in the network “are all being domesticated in a process of translation that relates, defines and orders objects, human and otherwise” (Law, 2009, p. 145). The actors and their connections hold themselves together but in a very uncertain manner, meaning that failure even in one translation can unravel the whole network (Law, 2009). That is, tensions between the expertise of players, coaches, and tracking technologies can be understood as a result of failed translations that may disturb the flow of connections and relations in the studied football team.

To make it easier to explain and work with this conceptual tool, Michel Callon (1986) separates four phases that constitute the process of translation: problematization, interessement, enrolment, and mobilization. The four phases can overlap as the translation constructs. In ‘problematization’ actors establish themselves as agents who build alliances “by defining, mobilizing and juxtaposing a set of materially heterogeneous actors, obliging them to enact particular roles and fitting them together to form a working whole”, that is to say, a network (Doolin & Lowe, 2002, p. 72). The agent works as a spokesman, a representative or a translator of this set of actors, aiming to persuade other actors who share a common problem and to enroll them into the network (Callon, 1986). An important part of problematization is to define the identity of different actors, their goals, projects, orientations, motivations, or interests that determine how the connections between them can be established and made stronger. This information helps with the agent’s efforts of persuasion which are done by presenting a solution to the problem, an ‘interessement’, that can be understood as a set of actions or a device performed between the actors to make ‘enrolment’ successful (Callon, 1986). Connections or relations between actors are achieved through mutual enrolment, that, however, is contested by other actors outside the network and, thus, is an unstable process of configuration and reconfiguration (Prout, 1996). This is why translation considers ‘mobilization’, by which “actors are first displaced and then reassembled at a certain place at a particular time” (Callon, 1986, p. 209) through the whole process described above. Hence, mobilization means putting all these equivalencies into place suitable for the network to work (Callon, 1986).

As Doolin and Lowe (2002, p. 72) point out, however, “resistance is possible and translation is only achieved when actors accept the roles defined and attributed to them”. In the case enrolment gets resisted, usually, an actor has chosen to define itself differently. This can result in a modified or disintegrated actor-network system (Callon, 1986; Doolin & Lowe, 2002). That is, the concept of translation poses as a useful tool for investigating how tensions

come to emerge between digital tracking devices, players and coaches and what kind of effects these tensions have in the network of the studied football team. In combination with the tool of non-human agency, it is possible to demonstrate how self-tracking technologies become part of the players’ everyday lives through their linked agencies, trace how the players move between the technological and other human actors and, finally, reveal how these connections and movements are both formed and disturbed in the process of translations between the tracking technologies and the different team members. As Shiga (2007, p. 42) observes, the notion of translation “raises the question of why actors come to accept others’ definitions of the problem and the prescribed actions and roles within it.” Even more interesting question for this thesis to address is, however, what happens if and when the actor does not accept the enrolment and the translation fails.

3.2 Ethnography

Given the principles, concepts, and approaches of Actor-Network Theory described above, it is quite logical, that ethnography is applied as the methodology of choice in this thesis (Macleod et al., 2019). As the origins of ethnography lie in anthropology, it is concerned with “first-hand empirical investigation” and “theoretical and comparative interpretation of social organization and culture” (Hammersley & Atkinson, 2007, p. 1). Evolved from the early days of Bronislaw Malinowski’s – considered as the founder of contemporary ethnographic fieldwork methods – anthropological adventures around the Pacific Islands (O’Reilly, 2005), modern ethnography touches more often local, near and, perhaps, familiar communities, rather than ones that are globally exotic and distant. It is interested in the routine of people’s everyday life, the ways their daily practices, experiences, and situations are understood and accounted for, and the different participants attending these occasions (Draper, 2015).

To do ethnography literally means to study people in their social and cultural context, to investigate the ways of understanding and being in the world, to write culture (Hammersley & Atkinson, 2007; Draper, 2015). Thus, at the heart of this qualitative approach to do research is to describe people and “how their behavior, either as individuals or as part of a group, is influenced by the culture or subcultures in which they live and move” (Draper, 2015, p. 36). Learning about people, their lives and culture ethnographically is, then, done by the means of participating in and observing the everyday. Indeed, as O’Reilly (2005) describes it, to comprehensively understand, explore, reveal and present a culture under study, an ethnographer is allowed and expected to take part in the daily activities and practices of the research participants. In ethnography, the researcher aims to immerse oneself into the studied community, learn from and with the participants, rather than just sit and watch. That is, a culture unfolds by talking to people, asking questions about their experiences, watching them and, actually, doing things with them in their day-to-day settings (O’Reilly, 2005). These key methods of ethnography link it with the theoretical framework of ANT. As Macleod et al. (2019) put it, “a fundamental connection between actor-network theory and ethnography is their focus on practices: everyday sayings, doings, and relations with objects that make up what people do in their everyday lives” (p. 180).

Through ethnography, technology can be approached as actively social. Combined with ANT, this research methodology facilitates a researcher to uncover and map the nuanced ways technologies participate in people’s daily practices. As Kien (2008) describes, “the intimacy of technology, the relationships and feelings it is bound up in, and the understanding that technology contributes dynamically and dramatically to the performance of everyday life rather than one-dimensionally serving as its backdrop and container” (p. 1103). To trace and reveal the relations between technologies and people, it requires, however, that the researcher is able to “attune to the mundane”, to view and present “everyday objects and practices that we may

otherwise not notice, nor bring to the fore” (Macleod et al., 2019, p. 180). According to Pink and Fors (2017b), the ways technologies take part in the constitution of people’s lives are often unspoken and unseen. Therefore, to properly understand their part in the studied culture, it is needed to view technologies more than as objective devices separated from the people and environments they are employed in. Rather should they be seen as participants possessing an active role in shaping social realities as they take part in people’s lives.

Particularly among anthropologists, there has been a tendency to consider ethnography as a prolonged, long-term process and methodology of research. However, Pink and Morgan (2013) argue that engaging with other people’s lives in an ethnographically justifiable way does not always have to be a result of a year-long fieldwork. Rather it can involve shorter, yet, intensive, “interventional as well as observational methods to create contexts through which to delve into questions that will reveal what matters to those people in the context of what the researcher is seeking to find out” (p. 352). The authors state that ‘short-term ethnography’ is characterized through intense participant observation, implicating oneself as a researcher at the center of the action and engaging participants in the process from the very beginning – doing research with, rather than about, people (Pink & Morgan, 2013). Thus, it is a competent way to study “the unspoken, unsaid, not seen, but sensory, tacit and known elements of everyday life” (p. 353).

3.3 Data collection procedures

In order to provide empirical results that derive from real-life experiences, this study has employed different methods to collect and produce data. These methods are characteristic of ethnographic research, including the researcher’s own reflective diary and self-observation, participant observation as well as semi-structured interviews. To create a prototype, the

research has also employed service design methods regarding co-design workshops conducted in combination with semi-structured interviews and as part of a focus group.

3.3.1 Digital autoethnography, reflective diary and self-observation

Autoethnography is a qualitative research method that combines autobiography and ethnography, the art of writing and the science of research (Ellis, Adams & Bochner, 2011). It involves “reflexive self-observation and an exploration of the experiential interrelationship between researchers and the social world in which they are situated” (Pink, Fors & Berg, 2017, p. 531). The purpose of autoethnography is to extend sociological understanding, by giving personal experience a voice that has a simultaneous tone of engaging narrative and systematic analysis (Wall, 2008; Ellis, Adams & Bochner, 2011).

Autoethnography is commonly criticized for being biased in using personal experience as data and for “social scientific standards as being insufficiently rigorous, theoretical, and analytical, and too aesthetic, emotional, and therapeutic” (Ellis, Adams & Bochner, 2011, p. 283). However, the practitioners of the method state that research can be both evocatively written and scientifically sound (Ellis, Adams & Bochner, 2011). As Pink and Morgan (2013) argue, ethnography in itself poses as a research methodology for “knowing about and with people and the environments of which they are part” (p. 359), and thus involving oneself in the research is necessary.

Merged into ethnographic research practice, autoethnography can help to create a more comprehensive understanding of the experiences, feelings, and meanings of living the shared everyday life. Pink, Fors and Berg (2017) state that autoethnographic methods are particularly useful to be employed in studying the physical activities of people in the context of a digitally mediated world. That is, “engaging body monitoring technologies as part of an autoethnographic research methodology implies that ethnographic self-observation thus

involves yet another observer and a mechanism that partakes in writing the narrative of the self and body” (Pink, Fors & Berg, 2017, p. 531). In this sense, tracking technologies are viewed as research participants that can be interviewed with the help of digital autoethnographic methods. A diary can be considered as a valuable data source in qualitative research, enabling the researcher “to keep in touch with feelings and emotions that participants in the field may well share” (O’Reilly, 2005, p. 100). In order to reflect upon practices and experiences, record my thoughts and feelings and document everyday use, I entered the research field by starting to keep a reflective diary of my own self-tracking experiments with three different monitoring technologies that were already part of my athletic everyday practices. These digital devices were used daily during three weeks of active self-observation and reflected on in parallel with the participant observation and interviews. Since I was part of the team as one of the players, I kept observing myself and my tracking practices in relation to the other participants over the whole time in fieldwork.

To accurately capture my prevailing thoughts and feelings on the self-tracking practices and data, the diary was first audio-recorded, later transformed into written form and concurrently supported with screenshots and pictures. The self-observation data worked as a vital part in conducting the digital autoethnographic method as well as in understanding and investigating the research questions from an individual player perspective and a self-tracking aspect. Besides, the material provided a basis for the participant observation and functioned as a supplementary, yet important, contact point in the in-depth interviews with the players.

3.3.2 Participant observation

The participant observation and semi-structured interviews were conducted in an overlapping and partly simultaneous manner. Participating and observing are key elements in ethnographic research, considered to be linked to each other in an inseparable way (O’Reilly, 2005). An

ethnographer is expected to be actively involved in the research process, “participating, overtly or covertly, in people’s daily lives for an extended period of time, watching what happens, listening to what is said, and/or asking questions through informal and formal interviews, collecting documents and artefacts”, as Hammersley and Atkinson (2007, p. 3) describe. Since I already was a natural part of the football team as one of the players, there was no need to spend time and effort to obtain access to the group or immersing in its cultural everyday habits. Regarding the characteristics of short-term ethnography, my already existing immersion in the group allowed me to involve myself in the flow of daily actions of the team as well as include the participants in the research process from the beginning of the project (Pink, Fors & Berg, 2017). Thus, participating and observing became more a matter of making “the familiar strange”, rather than “the strange familiar” (O’Reilly, 2005, p. 102). Therefore, I began to unfold the self-tracking practices of the group by doing ‘quick and dirty’ interviews (Hughes, King, Rodden & Andersen, 1995), starting conversations around the locker room about different digital devices the players owned, while simultaneously observing the ways they used them in their day-to-day activities around the football environment.

This initial phase was followed by observation and participation over a period of eight weeks. During this time, I was part of the site as often as the participants. However, due to my role and responsibilities as a player in the team, I was not doing active participant observation daily. This allowed the participants “to forget I was researching them” (O’Reilly, 2005, p. 87) and, hence, let me preserve an ethnographically important semi-overt role in studying their natural habits and settings. In order to capture the atmosphere of the site, what was said, heard, seen and done around the team and its tracking technologies and practices, I recorded my observations, thoughts, and feelings by keeping notes, writing them up into ethnographic accounts and taking pictures throughout the time in the fieldwork.

3.3.3 Semi-structured interviews

In parallel with observation, I conducted in-depth interviews with seven player participants. The interviews were semi-structured, building on themes and a set of directive open-ended questions (see the questions in Appendix A) that allowed me to discuss freely with the respondents. As O’Reilly (2005, p. 122) describes, “you are likely to have a list of areas to cover and maybe a few questions already predetermined, but otherwise you will want to be free to introduce ideas as they occur to you or as the interviewee introduces them”. Hence, I used questions around three different themes to guide the discussions, yet, encouraging and allowing the players to elaborate on the topics with the help of follow-up questions that were not determined in advance. The themes included the following topics; ‘experiences and feelings related to self-tracking data and practices’, ‘ways self-tracking becomes part of everyday life’ and ‘tensions between the analog and digital expertise’.

By asking the players to bring their self-tracking technologies with them to the interviews and allowing them to explain, show and teach me the ways they navigate through their personal data, I was able to spur the discussions further and, most importantly, to see and understand better the habits behind their self-tracking practices. That is, “data evokes the past without fully predefining it, and that opens up conversations between researcher and the participants who understand the context behind it” (Nafus, 2018, p. 233). The presence of their digital devices and data made it possible for the players to recall and go back to different moments, happenings and feelings from both near and far past. Thus, apart from their vital contribution to the data collection in this research, the in-depth interviews helped me to expand my understanding, interpretations, and conclusions of the events, experiences, and practices observed around the team and its technologies.

The interviews took place either at the football stadium, the homes of the players or the home of the researcher. They lasted for 60–95 minutes, each including a 15–30-minute long

co-designing session where a paper model prototype of a player monitoring application was designed together with the researcher. By directing the players to think about the topic and engage with it in a practical and concrete way, the purpose of combining short co-design workshops with the interviews was to gather data for both the overall research and the later creation of the prototype. To be able to adequately transcribe and analyze the material, the discussions were audio-recorded.

3.3.4 Service design and co-design

Service design is an approach to designing service processes in a comprehensive, creative and human-centered way. It has been employed as a set of tools in helping to create a prototype as part of this research project. To be able to not only think through the technological solutions but to also regard, analyze and describe the processes as a whole, involving different stakeholders, their roles and actions, I have chosen to use service design instead of other design approaches. Service design aims to “break down silos and help people to co-create” (Stickdorn, Lawrence, Hormess, & Schneider, 2018, p. 21) by providing a process, a mindset and a language for using certain design tools in sparking meaningful conversations as well as creating common understandings and explicit knowledge. That is, for its collaborative nature, co-design is considered as one of the principal methods in service design thinking (Steen, Manschot & De Koning, 2011; Stickdorn et al., 2018). The main idea behind co-design is a group of people which generates a process of creation together with the help of design tools, such as journey or service maps, service blueprints, spreadsheet templates or even simple post-it brainstorming (IDEO, 2015; Stickdorn et al., 2018).

In order to bring the participants deeper into the research process and get needed feedback for the prototyping, the service design approach was deployed by using sketches, paper models and storyboarding in co-design workshops both as part of the separate interviews

with seven different players and in a focus group with four players. The individual co-design sessions constructed of brainstorming ideas and functionalities for a mobile application that could improve or replace the existing player monitoring technology in the team, helping to avoid possible tensions in tracking the team. This was done by giving the participants the possibility to use their imagination and to design freely with the help of simple paper models and post-it notes (see the designs in Appendix C), yet within the framework of given instructions. The sessions provided important information about the possible points of tension that continued to come to the fore and were challenging to be solved with the design. This both enlightened the research process and aided the decision to abandon the idea of building a prototype into a form of another digital tracking device that could risk recreating old and emerging new tensions in the football team.

Thus, the feedback and data gathered from the first workshops directed the process forward, followed by a co-design session with a focus group. The focus group consisted of four players, of whom two were part of the individual interviews earlier in the research process. The co-design workshop took place in the home of the researcher and lasted for 130 minutes. It included a short introduction to the topic and a discussion about a storyboard scripted by the researcher beforehand, a problem-solving session deploying problem cards, as well as a moment of sketching one’s own design of a tracking technology or a monitoring system that the members of the football team could use together. Material and findings from the other data collection procedures were used to facilitate this co-design workshop.

As the final prototype, a service blueprint of a system mapping the roles, relations and actions between different team members and illustrating the possible points of tensions around a player monitoring technology has been designed and produced. Blueprinting is a primary mapping tool for a service design process, which aims to plan and organize different resources, from people and technologies to other solutions and processes, so that both the organization’s

and the individual’s experience could be improved (Bitner, Ostrom & Morgan, 2008). Service blueprints are commonly used for illustrating business processes to make the most effective use of situations where a customer experience is delivered. “That is, service blueprinting can facilitate the detailed refinement of a single step in the customer process as well as the creation of a comprehensive, visual overview of an entire service process” (Bitner, Ostrom & Morgan, 2008, p. 69). In this thesis, it has been employed to visualize the social process around a player monitoring technology, demonstrating its possible pitfalls in the relations between the technology, the players, the coaches and other members of the team. Through enabling the depiction of the process characteristics, blueprinting has allowed me to ensure that the different team members can know in concrete terms what the process involves and understand their roles in its operation (Bitner, Ostrom & Morgan, 2008).

3.4 Sampling, participants and site

The participants in this study were recruited through non-probability, convenience sampling, consisting of people in the elite football team that the researcher herself played for during the time of the study. The total number of participants, involved either actively or passively in the observational part of the research, was 27, including 24 players (excluded the researcher) and three coaches. The participants were 25 women and two men. Ranging from 17 to 31, the average age of all the participants was 23 years old. 11 of the players were part of ‘quick and dirty’ interviews during the participant observation, which of seven attended to in-depth interviews. The ages of the players who were part of the in-depth interviews ranged from 18 to 28, leading to the average age of 25 years old.

The research site focused on the Malmö area, located in the south of Sweden. The football club’s stadium and the facilities around it, including the training field especially,

remained as the main location. However, while conducting the fieldwork, there were temporary changes in the site according to the movements of the team and the players.

3.4.1 Tracking technologies used by the researcher and by the participants

The researcher has had three different tracking devices in her personal use during the fieldwork of this research. The participation of Suunto 3 Fitness sports watch as well as two digital questionnaire tools, Quanter (used only by the researcher) and My TPE (used collectively in the team), has considered the researcher using, interacting and reflecting on the experiences with these devices on a daily basis.

Suunto 3 Fitness is a training watch for performance monitoring and round-the-clock activity tracking including sleep, stress, and recovery (Suunto, 2019). Besides measuring heart rate, distance, speed, intensity, duration, feeling, steps and calories, the watch has fitness-related features such as adaptive training guidance that generates a plan for training aerobic fitness (Suunto, 2019). Equipped with an integrated sensor system the device measures heart rate from its user’s wrist, enabling the user to record exercises or sleep quality without additional heart rate belt. To maintain a healthy lifestyle desirable for an elite athlete and to improve my everyday performances in football, the main purposes to use this device have been to keep track of my sleep, recovery as well as the level of training through specific records, especially heart rate zones, and distance.

Quanter mobile application is designed to connect coaches to the daily stream of players’ training load and recovery data (Quanter, 2019). Based on self-reporting practices, the application collects data through a training load query, sent to the player after every training session and match, and a recovery query, sent to the player every morning. These questionnaires include questions about physical and mental sensation of fatigue, injury, health, wellness, sleep, nutrition, and hydration. The application enables the user to assess the impact of training and

matches in a visual data summary of daily training loads and readiness scores over the last seven days (Quanter, 2019). Furthermore, it provides the player with immediate feedback by recommending extra recovery activities according to the answers. While Quanter is designed for team use, I have employed the application for individual use. Unlike My TPE, Quanter has enabled me to observe my daily readiness to train football and perceive the patterns in my recovery through the access to my own data.

My TPE is a web-based, yet mobile-friendly, platform for managing, monitoring and exchanging team related data. It enables coaches to share messages, files, and data with players and other members of the team, to plan and build schedules as well as to observe players with the help of a questionnaire feature (My Team Performance, 2019). As used collectively by the coaches, the medical team and the players in my team, the questionnaire’s main purpose is to generate daily self-reported recovery and readiness data of the players for the coaches to utilize in managing training loads, evaluating individual readiness and preventing injuries. The players do not have access to their own data. They are obligated to fill out the questionnaire every morning before noon. There are three multiple-choice questions about sleep, readiness and fatigue with a scale from 1 to 10 and one question about injuries to comment on.

The self-tracking technologies used by the player participants in the studied football team consisted mainly of different wearable devices, varying from sports and smart watches and fitness bracelets to tracking vests and pods. Mobile applications used for tracking purposes were mainly applications associated with the wearable device in the players’ personal use. In regard to team monitoring, the questionnaire tool was ordered to be used according to the team policy. Overall these technologies included, for instance, Apple Watches, Polar sports watches, Playertek tracking vests, and the My TPE questionnaire tool (see the full list in Appendix B). The participants’ motivations for using particular digital devices were characterized by a