BA

CHELOR

THESIS

Single-subject course, English 61-90 hp, 30 credits

Etymological Elaboration versus Written Context

A study of the effects of two elaboration

techniques on idiom retention in a foreign

language.

Nina Bergstrand

English 61-90 hp, 30 credits

Abstract

The premise that idioms are an important feature in second language learning and teaching is what underpinned the present study. The aim is to investigate what teaching method is the most effective for idiom retention; etymological elaboration or context elaboration. It is a small scale study run focusing on two groups of 9th grade students were approximately 80% of the students had Swedish as their mother tongue, whilst the remaining 20% had other languages. One group of 18 students where taught 15 opaque idioms. The idioms were presented with their etymology. The preference group consisted of 19 students and the same idioms were presented to this group in context. A pre-test was given to both groups in order to establish what idioms they already knew. A post-test was run immediately after the lecture, where the idioms were presented either in context or with their etymology, in order to determine the methods’ effect on immediate retention. After three weeks, a second post-test was run in order to discover the degree to which the idioms had reached the students’ long-term memory and compare the two teaching techniques accordingly. A questionnaire was also conducted in order to gauge out the students’ idiom awareness and to what degree they

believed that the teaching method helped them to remember the idioms.

The results of the study show that both teaching techniques are beneficial on idiom retention. Context elaboration, however, turned out to be most effective on immediate- and long-term retention.

Table of contents:

1. Introduction………2

1.1 Aim and research question……….3

2. Theoretical background………..4

2.1 Idioms in L2 teaching and learning………....4

2.2 Theories on retention 2.2.1 Levels of Processing……….5

2.2.2 Dual Coding……….7

2.2.3 Learning through visualizing or verbalizing………8

2.3 Etymological elaboration………...10

2.4 Learning from context………..12

3. Methodology………13

3.1 Participants and ethical considerations………13

3.2 The target idioms……….14

3.3 Procedure……….15

4. Analysis 4.1 Pre-test and comparison………..18

4.2 Immediate post-test (1) and comparison……….21

4.3 Post-test 2 and comparison……….24

5. Conclusion………..27 6. References

Appendices

- Table of each student’s score on all tests - Questionnaire

1. Introduction

In all languages around the globe, figurative expressions, such as metaphors, idioms and pro-verbs, are used in order to express subjects that are non-concrete such as emotion and attitude. Idioms reflect culture, some are culture-specific, others are used in a similar way in different cultures.

Furthermore, idioms are difficult aspects of language. According to Collins Cobuild Idioms Dictionary (CCID), idioms are “a group of words which have a different meaning when used together from the one it would have if the meaning of each word were taken individually” (CCID 2011: p.v). Idioms cause trouble for all language learners due to their linguistic curiosities (CCID, 2011), first language learners (L1) as well as second language learners (L2).

Native speakers learn idioms mostly through exposure. To the native speaker, idioms become a “word” that evokes an image, it does not function as a sentence (Cooper, 1999). L2 learners lack exposure to the target language and idioms seldom evoke that image. This makes idioms difficult to comprehend. However, many of the L2 idioms may have

equivalents in their L1 due to cultural embedding which will make them decomposable. A large number will remain impossible to decompose and will therefore, seem utterly abstract to an L2 learner. Abstract chunks of language will most likely cause motivation issues within the L2 learner, and will therefore make them difficult to comprehend and remember.

Even though they are an important part of language, idioms have rarely been taught in second language classrooms. There might be several reasons for this. It is likely that idioms are viewed upon as rather infrequent items, and are therefore given less attention compared to other vocabulary items. This conception is not quite correct though, as they do actually occur quite frequently in everyday discourse. Journalists for example, use them in newspapers and magazines “…to make their articles and stories more vivid, interesting and appealing to their

readers…” (CCID, 2011: p. vi). Another reason why they are not taught, might be because idioms may seem abstract and arbitrary to the L2 learner making it a challenge for the teacher to address and teach them effectively. If the goal of the L2 English learner is to be as

proficient in the language as possible, however, idioms needs to be addressed and taught. The challenge for the teacher is therefore, to use attention drawing techniques and teach these expressions in such a way that enhances retention as well as comprehension of the most frequent idioms.

According to Crystal (1997), “Idioms help language learners understand English

culture, which has its roots in the customs and lifestyle of the English people, and provides an insight into English history” (Crystal, 1997 cited in Noorozi and Salehi, 2013). Therefore, teaching idioms in Swedish schools will help students develop good communicative skills as well as an understanding for English culture. This is in line with the main ideas in the

Swedish curriculum, where one of the main goals is for students to “develop knowledge about and an understanding of different living conditions, as well as social and cultural phenomena in the areas and contexts where English is used” (Skolverket, 2011: p. 32).

1.2 Aim and research question.

As discussed above, there are several reasons why English idioms should be addressed in Swedish schools. The aim of this paper is to use etymological elaboration and written context in the teaching of idioms to 9th grade students, and investigate which technique is more efficient when it comes to retention of L2 idioms.

The students were also asked to fill in a questionnaire at the end of the study. The aim of the questionnaire is to gather the students’ thoughts on working with etymological

the idioms. An in-depth explanation of these two teaching techniques will be given in Sections 2.3 and 2.4 respectively.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1 Idioms in L2 teaching and learning

In the development of a first language, cognitive maturity is an important factor. However, when exposed to a second language, cognitive maturity is no longer the most important factor. Instead, the learner is likely to transfer knowledge from their L1 to the learning of a new language. Cooper (1999) lists the principal findings of studies on L2 idiom acquisition. According to these, learners have difficulties comprehending and producing idioms in the L2. The first argument on his list states that it is easier to learn frozen idioms compared to the ones that are syntactically flexible. The reason might be that flexible idioms appear in more than one syntactic form which makes them more complex. Frozen idioms seem to be ‘internalized as a single lexical item’ (Cooper, 1998: p. 259) because they appear more frequently in only one syntactic form. Furthermore, second language learners tend to make use of their first language in order to understand and produce idioms in their L2. Idioms that have an equivalent in their L1 is apparently easier to comprehend and produce. ‘Semantic transparency can be defined as the extent to which an idiom’s meaning can be inferred from the meaning of its’ constituents’ (Glucksberg, 2001: p. 74). An example of a fully transparent idiom, from a Swedish learner perspective, is behind closed doors which in Swedish has the direct translation equivalent bakom stängda dörrar. The idiom is translatable on a word to word basis, and it has the same meaning in both languages. Second language learners tend to try to translate idioms into their mother tongue. This, however, is often problematic as many idioms cannot survive a literal translation. Idioms that are semi-transparent, such as paint the

but it offers essentially the same meaning. According to Kövesces (2002), “an idiom arises from our general knowledge of the world embodied in our conceptual system” (Kövesces, 2002: p.201) Therefore, the meaning of idioms is not totally arbitrary, they are actually to a great extent motivated. He speaks about conventional knowledge which plays a role in motivating the idiom meaning. In the example of the semi-transparent idiom above, the word

red is easily associated with danger (the colour red can be associated with blood or danger)

which makes the idiom partly decomposable to a Swedish learner. There are, however, idioms which have no conceptual motivation. These idioms are called opaque. An example of an opaque idiom is kick the bucket, where the meaning of the idiom cannot be predicted from the meaning of the constituent words. According to Kösesces’ conventional knowledge, learners should be able to learn idioms faster and retain them longer in memory if they were presented with the cognitive motivation of idioms (Kövesces, 2002: p.201). Glucksberg states that idioms must be memorized (Glucksberg, 2001). It is therefore important to teach strategies for remembering idioms.

2.2 Theories on retention

In the following sections, different theories regarding retention will be presented and discussed. It starts with the Levels of Processing Theory, which aims to explain the system of memory. A presentation of theories that aims to explain what strategies that benefit retention will follow, then finally, theories regarding individual differences among learners will be presented.

2.2.1 Levels of processing theory

The Levels of Processing Theory (LOP) was developed by Craik and Lockhart in 1972, and states that remembering is an activity of mind and the result of processing information.

The act of remembering goes through different levels. It is a process, from perceptual processing to semantic processing, where the first is regarded as the shallow level of

processing, and the latter a deeper level of processing which is associated with higher levels of retention (Craik & Lockhart, 1972). In 1975, Craik and Tulving ran a series of experiments in order to explore LOP and explain the “system of memory”. The subjects used for the experiment were presented with a list of words. Guided tasks came along with the lists and were adopted to control the “depth” of processing used to encode the words. One task would be to answer questions concerning typeface, the method is called perceptual processing, which is regarded as a shallow level of processing by Craik and Lockhart. With the word tiger as an example, the question could be concerned with whether it was written with capital letters. The next level is phonemic processing, and the task that might be given for this level was to consider whether the word train rhyme with Spain. The subjects were also asked questions directed toward semantic content. With the word bird, the question might be whether the word fits into to the sentence “A _____ has wings”. Craik and Lockhart found that if a word was congruent with the orienting question it was better encoded and recognised compared to those that were not congruent. As in the examples above, train rhymes with

Spain, making the question and answer congruent. Further, Craik and Lockhart considered

semantic analysis (Does bird fit into “A______has wings”?) as more elaborate and the results showed that the words were better recalled (Craik, 2002). Semantic processing involves elaboration rehearsal which is characterized by analysing and thinking about meaning, processing by engaging new material with existing schematic structures and by regarding the importance of the new material. According to LOP, it is only semantic processing that will lead to an improvement in memory (Craik, 2002). When taking LOP into consideration, learning vocabulary, such as idioms in L2, will most likely be more successful if processed

semantically giving the students the opportunity to relate the target idiom to prior knowledge as well as analysing and thinking about its meaning.

2.2.2 Dual Coding theory

Another theory that enlightens the significance of elaboration in retention is the Dual Coding Theory (DCT). DCT was first coined by Mark Sadoski and Allan Paivio. It was the leading cognitive theory in the 20th century, and had a huge impact on education and

especially language teaching. Dual coding theory implies that abstract language is harder to recall than concrete language. A heavy hammer is an example of concrete language as it has direct sensory referents. The word love, on the other hand, is an example of abstract language which has no physical referents. Concrete language tends to evoke mental imagery which is an important factor in retention and recall. According to DCT, cognition involves two

different mental codes: one for dealing with language which is called logogens and represents the verbal system in our mind. The imagens, however, represent the non-verbal system which deals with non-linguistic objects and events in the form of mental images. DCT suggests that concrete words are dually coded, as they can more easily evoke mental pictures. Therefore, concrete words are easier to comprehend and remember. The concrete word car, for example, is dually coded in our mind: the word car (logogen) and the image of a car (imagen). Abstract words, however, “are difficult to image and hence are least likely to be dually coded” (Paivio, 2006: p. 4). Idioms are abstract chunks of language and are difficult for all learners, especially for L2 learners. It is hard to guess their meaning from the words they consist of, and they are typically used in a figurative sense. Therefore, it is unlikely that they are dually coded and this makes them difficult to learn.

The essence of DCT is its effects on memory, and the theory holds that there are

creating mental images about what one is supposed to learn and remember will benefit retention because they help the chunking of information in our memory. Sadoski and Paivio (2001) call this the conceptual peg hypothesis. The mental images created are central “in organization and retrieval from memory by serving as mental ‘pegs’ to which at least some of the other parts of the episode are ‘hooked’” (Sadoski & Paivio, 200: p. 106). Allan Paivio explains this by giving the following example: If a monkey-bicycle is presented and one tries to image this as a monkey riding a bicycle. Then when the target word/sentence is to be recalled one stimulus (monkey for instance) is likely to increase the probability of recalling the response which is the bicycle. (Paivio, 2006).

In regard to the levels of processing and dual coding theory, it would be possible to draw the conclusion that, in idiom teaching and learning, it would benefit the learning process if the students were guided and given the opportunity to elaborate through reflecting on the meaning of the target idiom as well as be guided in and given the opportunity to create internal images of idioms and their meaning. In line with the levels of processing theory, it is important to consider elaboration as a part of the teaching technique, as this is likely to enhance knowledge to be stored in long term memory. According to Craik, creating a

meaningful process contributes to deeper levels of processing. He states that, what facilitates retention is “the meaningfulness extracted from the stimulus rather than in terms of the number of analyses performed upon it” (Craik, 1973: p. 48). According to DCT, learning strategies that give the students opportunities to create mental images will also facilitate retention.

2.2.3 Visualizers and verbalizers

That creating mental images will facilitate retention relies on students’ ability to do so. A person’s practical ability to adapt what is taught might differ. Howard Gardner assumed

that there is a diversity of skills among individuals when he introduced his multiple

intelligences. According to Gardner, the eight intelligences are universal which means that everyone possesses them, however, no one exhibit them in the same proportions. Garner’s eight intelligences are the linguistic-, logical-mathematical-, spatial-, bodily kinaesthetic-, musical-, interpersonal-, intrapersonal- and naturalist intelligence. A person who has a highly developed linguistic intelligence can be referred to as word smart, while a person who has a highly developed spatial intelligence can be referred to as picture smart (Gardner & Hatch, 1989). In line with Garner’s theory, some individuals might prefer learning by using images due to their ability to visualize, while others might prefer learning through words due to their ability to verbalize. In their study Kraemer, et al hypothesized ‘that visual brain regions subserve the visual cognitive style and that the verbal cognitive style relies on brain areas linked to phonology and verbal working memory’ (Kraemer, et al., 2009: p. 3792). In order to check their hypothesis, the subjects were presented with stimuli either as images or words. The experimental conditions were picture-picture, word-word, picture-word and word-picture. It was possible for the subjects to complete the task by using a verbal strategy or a visual strategy. Further, it was possible for the subjects to convert from a non-preferred modality to a preferred modality. Kraemer, et al studied the subjects’ brain activity and focused on brain regions in verbal and visual working memory. Their findings demonstrate that subjects who are associated with the verbal style have a tendency to convert pictorial information into linguistic information, while linguistically presented information is converted into a visual mental representation among those who have a tendency towards the visual style. The study also shows that ‘when one encounters a stimulus that is presented in a non-preferred modality, one mentally converts that information into his or her preferred modality’ (Kraemer et. al 2009, pp 3797).

What Kraemer et. al found in their study, does not fully correlate with DCT and Paivio’s (2006) assumption that creating mental images about what one is supposed to learn and remember will benefit retention. Students who are verbalizers might not be able to create mental images. Gardner’s theory validates this as well, not all learners have a developed spatial intelligence.

2.3 Etymological Elaboration

Etymological elaboration is a teaching and learning technique where the students are presented with the origin of an idiom. According to Lakoff and Johnsson; “Many abstract words are ‘dead’ metaphors, i.e. terms that were once meant more literally” (1980, 1999 cited in Paivio, 2006: p. 229). The meaning of many metaphors and idioms are “motivated” rather than arbitrary. The duo also states that teaching the roots of specific vocabulary is likely to present meaning to something that might seem abstract to the learner. Accordingly, teaching idioms with the method called etymological elaboration will contribute to retention because it encourages learners to concretize abstract language.

Idioms often arise from specific source domains. In English a common source domain to idioms is for example boats and sailing. Expressions that can be traced back to a specific source domain are more likely to engender an image in line with the dual coding theory. The cognitive effort used when trying to understand idiom usage based on the origin of an idiom, probably occurs at a deeper level in accordance with LOP and therefore facilitates retention. Boers, et al. have run a series of studies to investigate the effect of etymology in the teaching of idioms. These studies inspired other researchers to conduct studies within the same field. Bagheri and Fazel (2010) studied the effect on Iranian learner’s comprehension and retention of idioms. They found that etymological elaboration helped the learners in figuring out the meaning of idioms as well as having a positive effect on retention. In a study conducted by

Noroozi and Salehi (2013), two groups of Iranian female students were taught idioms in two different ways. The experimental group was presented with the idioms’ original usage and etymological notes. The control group was encouraged to learn the idioms without any etymological elaboration. The results revealed that the etymological elaboration group performed significantly better than the control group when learning idioms. Razmojoo, Songhori and Bahremand (2016) wanted to see the effect of two attention drawing techniques and added typographic salience to their research on etymological elaboration on Iranian students. The results of this test also favoured etymological elaboration.

Furthermore, Boers, et al found in their 2002 experiment that the effect of etymological elaboration was strongest when the target idioms were transparent. With opaque idioms however, the effect seemed negligible. Boers, et al (2004) questioned these findings and implied that this might be because of their task design. It consisted of a comprehension task and an identify-the-source task. It seemed that the latter task was the one causing the negative result. In the way it was conducted, the students might have lost their motivation due to the lack of reward when they tried to klick on what they believed to be the source domain of the given idiom. This might have resorted to random clicking. Boers, et al also implied that the origin might seem too far-fetched, causing the students to lose their motivation because it all became frustrating. According to the test findings, ‘idioms that required one or two clicks were easier to remember compared to those that required more than two clicks which

confirmed the conclusion that motivation was lost (Boers, Demecheleer & Eyckmans, 2004). According to Frank Boers (2008), linguistics used to believe that idioms were completely arbitrary. Therefore, in school, students were told that in order to learn idioms they would have to memorize them. The results of the research mentioned above, show that this is not true, etymological elaboration is an effective technique when learning idioms compared to memorizing them.

2.4 Context Elaboration

A favoured vocabulary learning strategy is to make inferences of word meaning based on written context. According to Haastrup, this “involves making informed guesses as to the meaning of a word in the light of all available linguistic clues in combinations with the learner’s general knowledge of the world, her awareness of context and her relevant linguistic knowledge” (1991 cited in Çetinaci, 2013: p. 2670). In an L1, on the other hand, idioms are more likely to be acquired through exposure and given relevant situations in everyday discourse. In second language learning, learners often lack the skills to take advantage of contextual clues. According to Nation, 95% - 98% of all words have to be understood in a text if inferencing is to be successful (Nation, 2001). The context might also not be rich enough for learners to infer the meaning. However, if the context contains high textual support for the idiom meaning, comprehension is more likely to occur. For opaque idioms, textual support is crucial in order for the learner to comprehend meaning. Second language learners frequently use context in order to interpret idioms, alongside searching for expressions in their first language, which could help them interpret the target idiom (Karlsson, 2013). The latter method does not apply to opaque idioms, and the learner needs to rely on context. In several studies, researchers have shown that using contextual clues is an effective strategy in idiom comprehension. Cooper (1999) tested what kinds of strategies were used in idiom

comprehension. The participants were presented with idioms, where each idiom was incorporated into a one- or two-sentence context. In his research, he used think-aloud protocols (TA) where participants were asked to verbalize their thoughts. Cooper states that “TA data provide evidence of what is on the subject’s mind during the task” (Cooper, 1999: p. 241). This research showed that guessing from context was used 28% of the time, followed by analysing and discussing the idiom which was used 24% of the time. Afram (2016) compared

teaching idioms to Swedish upper secondary school students by presenting the idioms in written context versus visual context in the form of pictures. The written context group

performed better after one week, while the visual group, however, performed better after three weeks. So, context teaching seemed to be favourable when it comes to comprehension. Visual context, on the other hand, seemed to have more effect on retention.

3. Methodology

3.1 Research question addressed.

The aim of this study is to investigate whether etymological elaboration has a better effect on retention of English idioms than written context.

3.2 Participants and ethical considerations.

The present study was run on two groups of 9th grade students. The number of students who participated in all parts of the experiment was 18 in the etymology group (ETY-group), and 19 in the written context group (CTX-group). Prior to the experiment, teachers were asked if they wanted to participate and the students were first informed by their teacher. On paper, the etymology-group consisted of 22 students (there were only 18 who actually participated in the test, as 4 students were not present on more than one occasion). The context group consisted of 16 students only. Therefore, 6 students from another group were added in order for the test results to be as reliable as possible. 19 students in the written context group participated in all parts of the test.

In regards to ethical considerations, the students were told to write a code next to their number, ETY for the etymology group and CTX for the context group. Each student was given a number (e.g. CTX01, ETY17) by their teacher to write on their answering sheets. The participants and their codes are presented in table 1 and 2 below. The number they received

was not known to the present researcher. The students were informed that all data was anonymous and that their answers would not in any way be graded.

During the first lesson, the introductory lesson, the students were given a short presentation of what idioms are, alongside a short idiom ‘teaser’ video. The purpose of this video clip was to motivate the students. None of the idioms chosen for this study was a part of the video. They were further informed about the aim of this study. This introductory lesson was given in English, but translated into Swedish to make sure that everyone had understood the experiment and felt comfortable in participating.

As mentioned before, the written context group turned out to be a mix of two groups because more students were added to a small group of students. It was observed by the present researcher, that this smaller group of students seemed more self-confident when it came to interaction in English in the classroom as compared to the other groups. The majority of the group were participating during the introduction and seemed to possess more idiom knowledge. There was a permissive climate in the group and they were easy to motivate. The etymology group was quieter and did not participate to the same extent. It was a positive group, however, they seemed to be less self-confident. The last 6 students who were added to the context group, was a part of a class with many students who had difficulties learning English. This group seemed to feel very uneasy speaking English in class and most of the students spoke only Swedish.

3.3 The target idioms

The 15 idioms chosen for this experiment are all considered by the present author to be opaque. This makes it hard for the student to decompose them as the idioms have no equivalent in Swedish, they cannot be analysed on a word-to-word basis and many of them are culture-specific. It is important to point out that the questionnaire showed that 22.2% of

the students in the etymology group and 26.3% in the written context group had another mother tongue than Swedish. Therefore, it is a possibility that all idioms might not be opaque to some students as there might be idioms that are transparent or semi-transparent depending on their L1.

As the aim of this experiment is to investigate which elaboration technique is most efficient on retention, the present researcher wanted the students to rely on context or etymology only. A problem with this approach is that the students might lose interest due to the task being too difficult for them. Motivation was therefore considered important. When considering what idioms to choose, these considerations were made:

- Does the idiom have an appealing etymology that the students might regard as interesting?

- Does the idiom function well in a context that the students are able to comprehend?

- Is the idiom frequently used in English?

Interesting etymology was first searched for, followed by looking up the idiom in Collins Cobuild Idioms Dictionary in order to investigate frequency. All idioms are considered frequent except a canary in a coal mine which is chosen for its interesting etymology. To be able to insert the idioms in contexts that the student could relate to, was also given attention and consideration.

3.4 Procedure

The experiment consisted of 3 parts: 1. Introduction and pre-test

2. A teaching lesson and an immediate post-test. 3. A second post-test and a questionnaire.

The pre-test was used to figure out the students’ prior knowledge of the target idioms. These tokens were then excluded from the post-tests. The purpose of the immediate post-test was to register immediate retention. The second post-test was given after three weeks to check long term retention. The only thing that differed between the three tests was the order in which the test items were presented.

Example:

1. A gravy train

I don’t know what this idiom means. I think I know what it means. My guess is:

___________________________________________________________________________ I know what this idiom means. It means:

___________________________________________________________________________

During the lesson a PowerPoint slide was used to introduce the idioms. The students were presented with each idiom either in a context or with its etymology. Each student was to reflect on their understanding of the idiom, which had just been presented, individually and fill in a work-sheet. The work-sheet was designed with three options, either I don’t

understand this idiom, I think I understand this idiom or I’m quite sure I understand this idiom. The reason for this procedure was that it would hopefully influence the student to try to

draw a conclusion from what had been presented and not just rely on someone else’s

interpretation. They were given some time to do this with each presented idiom and then they were told to discuss and try to interpret the idiom in pairs. The groups were then asked to participate in class and present their interpretation. Finally, they received the correct answer.

4. Analysis

The results of the pre-test, the immediate post-test (post-test 1) and post-test 2 will be presented and discussed in the following section. The results are included in the discussions. They will be presented starting with the etymology group in each subsection and be followed by the context group’s results and then a comparison of the two will be offered.

4.1 Results on pre-test and discussion.

There were 18 students who participated in all parts of the test and were taught the idioms with their etymology. The students who missed the teaching lesson was omitted form the pre-test results. Table 1 shows the number of students who gave correct-, wrong-, or no given answers out of the total of 18 students. The percentage is written in bold.

Table 3: Pre-test ETY- group

The idioms Correct

answer % Wrong answer % No given answer %

To have a chip on one’s shoulder 0/18 0 2/18 11.1 16/18 89

To show someone the ropes 1/18 5.5 1/18 5.5 16/18 89

A gravy train 0/18 0 0/18 0 18/18 100

Under the weather 0/18 0 2/18 11.1 16/18 89

A red Herring 0/18 0 1/18 5.5 17/18 94

Play gooseberry 0/18 0 0/18 0 18/18 100

A canary in a coal mine 0/18 0 1/18 5.5 17/18 94

To have someone over a barrel 0/18 0 0/18 0 18/18 100

Get the sack 0/18 0 1/18 5.5 17/18 94

Hear it on the grapevine 0/18 0 0/18 0 18/18 100

Jump on the bandwagon 0/18 0 0/18 0 18/18 100

When the chips are down 0/18 0 1/18 5.5 17/18 94

Bite the bullet 2/18 11.1 1/18 5.5 15/18 83

Stick to your guns 0/18 0 2/18 11.1 16/18 89

Kick the bucket 0/18 0 0/18 0 18/18 100

Total 3/270 1.1 12/270 4.4 255/270 94

The test results show that the idioms are, to a large extent, unknown to the students. Only 3 students (1.1%), were able to offer the correct idiom meaning. None of these students marked that they knew the target idiom, but that they guessed the meaning. 4.4% tried to guess some of the idioms, but were unable to guess them correctly. 94% gave no answer. Table 4 shows the result of the written context group which consists of 19 students.

Table 4: Pre-test CTX-group

The idioms Correct

answer %

Wrong

answer %

No given answer % To have a chip on one’s shoulder 0/19 0 2/19 10.5 17/19 89.5 To show someone the ropes 1/19 5.3 2/19 10.5 16/19 84 A gravy train 0/19 0 2/19 10.5 17/19 89.5 Under the weather 1/19 5.3 3/19 15.8 15/19 79 A red Herring 1/19 5.3 0/19 0 18/19 95 Play gooseberry 0/19 0 2/19 10.5 17/19 89.5 A canary in a coal mine 0/19 0 3/19 15.8 16/19 84 To have someone over a barrel 0/19 0 3/19 15.8 16/19 84 Get the sack 1/19 5.3 1/19 11.1 17/19 89.5 Hear it on the grapevine 0/19 0 0/19 0 19/19 100 Jump on the bandwagon 2/19 10.5 3/19 15.8 14/19 74 When the chips are down 0/19 0 2/19 10.5 17/19 89.5 Bite the bullet 4/19 21 3/19 15.8 12/19 63 Stick to your guns 0/19 0 8/19 42 11/19 58 Kick the bucket 1/19 5.3 1/19 11.1 17/19 89.5

Total 11/285 3.9 35/285 12.3 240/285 84

The results show that the idioms were unknown to this group as well. They were able to identify 3.9% of the idioms. 1 student actually knew 3 of the idioms (to show someone the

ropes, under the weather, a red herring) and guessed 2 correctly (jump on the bandwagon, kick the bucket). 5 students were able to guess idiom meaning. 12.3 % gave wrong answers

and 84% gave no answer.

The results show that the idioms are fairly unknown to the students, and that the meaning of them is hard for them to predict. The questionnaire that was given to the students by the end of the project, also confirmed that idioms in general were unfamiliar to most of the students and that they do not use them often or are unsure whether they do. The students were

to consider whether they had been taught idioms prior to this; 83.3% of the etymology group answered that they had not been taught idioms or did not know if they had been taught

idioms. The correspondent figure for the context group was 68.4%. These results indicate that the students lack prior knowledge and experience regarding idioms. Furthermore, the context group performed slightly better than the etymology group on the pre-test. As mentioned in Section 3.1, there seemed to be differences between the groups. This was reflected in the answers on the pre-test slightly. As mentioned, the context group, with students who came across as more-confident in using the English language, performed slightly better than the etymology group on the pre-test, 2.8 percentages. They also tried to guess the idioms’ meaning to a greater extent. They guessed 16.2% of the idioms, 3.9 of which were correct guesses. The etymology group guessed 5.5%, where 1.1% were correct guesses. The idiom that most students were able to guess the meaning of was bite the bullet (no one claimed to know this idiom). The initial word of the idiom bite, seems to have made the students think of the Swedish equivalent bita i det sura äpplet, which some of the student used as an

explanation. One student wrote; “bita ihop, ta skiten” as an explanation. The idiom to show

someone the ropes was guessed by another student in each group where the initial words to show someone seemed to have led the students into believing that it meant to show/teach

someone how to do something. Jump on the bandwagon was guessed by a student who seemed to relate the words jump on to “join in on something, doing what everyone else does”. So, to some of the students, there is semantic transparency.

4.2 Results on immediate post-test (1) and discussion

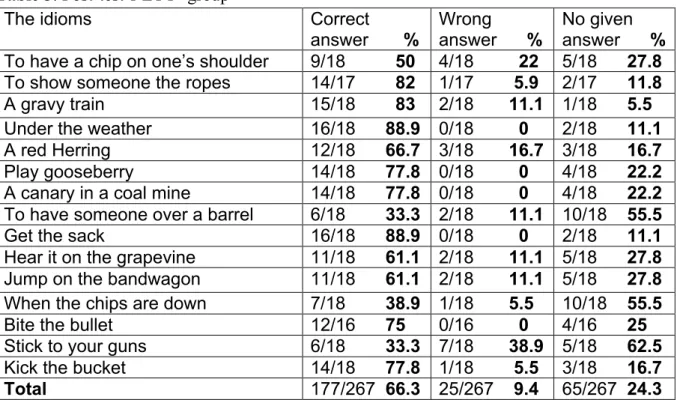

The first post-test was structured in the same way as the pre-test. However, as mentioned earlier, the idioms were presented in a different order from the pre-test and in a different order than presented during the lesson. 18 students in the etymology group took the test. Their results are presented in Table 5.

The results of the immediate post-test show that 66.3% of the etymology group were able to give correct answer, 9.4% gave incorrect answers and 24.3% gave no answer. This shows an improvement of 65.2 percentages.

Table 5: Post-test 1 ETY- group

The idioms Correct

answer %

Wrong

answer %

No given answer % To have a chip on one’s shoulder 9/18 50 4/18 22 5/18 27.8 To show someone the ropes 14/17 82 1/17 5.9 2/17 11.8 A gravy train 15/18 83 2/18 11.1 1/18 5.5 Under the weather 16/18 88.9 0/18 0 2/18 11.1 A red Herring 12/18 66.7 3/18 16.7 3/18 16.7 Play gooseberry 14/18 77.8 0/18 0 4/18 22.2 A canary in a coal mine 14/18 77.8 0/18 0 4/18 22.2 To have someone over a barrel 6/18 33.3 2/18 11.1 10/18 55.5 Get the sack 16/18 88.9 0/18 0 2/18 11.1 Hear it on the grapevine 11/18 61.1 2/18 11.1 5/18 27.8 Jump on the bandwagon 11/18 61.1 2/18 11.1 5/18 27.8 When the chips are down 7/18 38.9 1/18 5.5 10/18 55.5 Bite the bullet 12/16 75 0/16 0 4/16 25 Stick to your guns 6/18 33.3 7/18 38.9 5/18 62.5 Kick the bucket 14/18 77.8 1/18 5.5 3/18 16.7

Total 177/267 66.3 25/267 9.4 65/267 24.3

As explained before, the context group went through the same procedure as the

etymology group. The results of the 19 who were chosen to participate in the test is presented in table 6.

Table 6: Post-test 1 CTX-group

The idioms Correct

answer %

Wrong

answer %

No given answer % To have a chip on one’s shoulder 12/19 63.2 5/19 26.3 2/19 10.5 To show someone the ropes 16/18 88.9 2/18 11.1 0/18 0 A gravy train 14/19 73.7 2/19 10.5 3/19 15.8 Under the weather 16/18 88.9 0/18 0 2/18 11.1 A red Herring 8/18 44.4 2/18 11.1 8/18 44.4 Play gooseberry 15/19 78.9 2/19 10.5 2/19 10.5 A canary in a coal mine 10/19 52.6 5/19 26.3 4/19 21 To have someone over a barrel 15/19 78.9 1/19 5.3 3/19 15.8 Get the sack 13/18 72.2 1/18 5.5 4/18 22.2 Hear it on the grapevine 12/19 63.2 0/19 0 7/19 36.8 Jump on the bandwagon 12/17 70.6 2/17 11.8 3/17 17.6 When the chips are down 7/19 36.8 1/19 5.3 11/19 57.9 Bite the bullet 12/15 80 3/15 20 0/15 0 Stick to your guns 14/19 73.7 2/19 10.5 3/19 15.8 Kick the bucket 13/18 72.2 2/18 11.1 3/18 16.7

Total 181/274 68.9 30/274 10.9 63/274 23 The results show that 68.9% were correct answers, 10.9 were incorrect and 23% gave no answer. Compared to the pre-test, the group showed an improvement of 65 percentages. Post-test 1 shows that the group who received etymological explanations for the idioms, did not perform as well as the group who were presented with the idioms in a written context. Even though the etymology group’s total score was poorer, they did show better results on two of the idioms. They gave 22.3 percentages more correct answers on a red herring and 25 percentages more correct answers on a canary in a coal mine. One reason for this might be that, the particular etymology presented for these idioms contributed more to the creation of internal images than the other idioms did. Therefore, these idioms became concrete rather than abstract which is in line with DCT theory. Another reason might be that, these two idioms were the only ones including animals. As idioms connected to the world of animals are common in many languages, it is also possible that the students found them easier to

understand. Finally, it is possible that idioms containing animals might arouse sensory referents in form of e.g. sympathy, which contributes to them being easier to remember.

Post-test 1 shows that written context gave slightly better results on immediate retention than did etymological elaboration. The context group gave more correct answers on a total of 9 idioms out of 15. They showed remarkably better results than the etymology group on two idioms; to have someone over a barrel which got 45 percentages more correct answers and

stick to your guns which got 40 percentages. The reason why these idioms turned out to be

easier to recollect, might be because the written context in which they were presented was easier to comprehend compared to the etymology. It might also be that, these idioms are more used in the world of computer and TV games which is a huge interest among many of the students in the written context group. This was confirmed by their teacher and in the last question of the questionnaire, as many of the students in this group wrote that they learnt vocabulary while playing computer- and TV games.

When considering the performance of the etymology group on the idioms to have

someone over a barrel and stick to your guns, it is quite obvious that the students who

received the etymological explanations found them hard to comprehend. They had a hard time predicting and explaining the idioms’ meaning. This was noticed on their worksheet where they marked that they did not understand the idiom meaning, as well as when they were to speak out their thoughts. Many students in the etymology group marked that they felt unsure whether they had understood the idiom stick to your guns and wrote that they thought the meaning of this idiom was “hold your position”. This shows that the students had a hard time connecting the etymology with the usage of this idiom, thus, the students had difficulties creating an “image” and the idiom remain abstract. Written context seems to function in the same way, i.e. the context in which the idioms are delivered might not present the needed amount of information in order for the student to comprehend the idiom correctly, but

according to these results it does so to a greater extent than presenting its etymology. Context- elaboration seems to have a better effect on immediate retention. Both teaching techniques

seem to some extent, however, to have created meaningful processes which has contributed to deeper levels of processing.

4.3 Results on post-test 2 and discussion

The students took the second post-test exactly 3 weeks after the idiom lesson. The test was the same as the pre-test, however, as mentioned before, the idioms came in a different order than presented during the lesson and in a different order than the first post-test. These students’ results are shown in Table 7.

Table 7: ETY- group

The idioms Correct

answer %

Wrong

answer %

No given answer % To have a chip on one’s shoulder 7/18 38.9 2/18 11.1 9/18 50 To show someone the ropes 9/17 52.9 3/17 17.6 5/17 29.4 A gravy train 1/18 5.5 2/18 11.1 15/18 83.3 Under the weather 5/18 83.3 3/18 16.7 10/18 55.5 A red Herring 3/18 16.7 4/18 22.2 11/18 61.1 Play gooseberry 7/18 38.8 1/18 5.5 10/18 55.5 A canary in a coal mine 11/18 61.1 0/18 0 7/18 38.9 To have someone over a barrel 3/18 16.7 1/18 5.5 14/18 77.8 Get the sack 8/18 44.4 0/18 0 10/18 55.5 Hear it on the grapevine 8/18 44.4 2/18 11.1 8/18 44.4 Jump on the bandwagon 10/18 55.5 1/18 5.5 7/18 38.9 When the chips are down 2/18 11.1 1/18 5.5 15/18 83.3 Bite the bullet 10/16 62.5 2/16 12.5 4/16 25 Stick to your guns 2/18 11.1 4/18 22.2 12/18 66.7 Kick the bucket 6/18 33.3 2/18 11.1 10/18 55.5 Total 92/267 34.5 28/267 10.5 147/267 55.1 The results show that the etymology group gave 34.5% correct answers. This means that they forgot 31.8 percentages of the idioms. 10.5 % gave an incorrect answer, and 55.1% gave no answer.

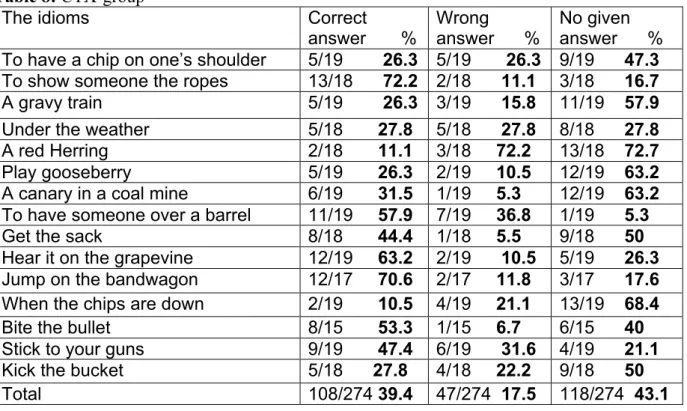

The written context group also took the second post-test exactly 3 weeks after they took the first post-test. The procedure was the same as for the etymology group, explained above. Table 8 shows their result.

Table 8: CTX-group

The idioms Correct

answer % Wrong answer % No given answer % To have a chip on one’s shoulder 5/19 26.3 5/19 26.3 9/19 47.3 To show someone the ropes 13/18 72.2 2/18 11.1 3/18 16.7 A gravy train 5/19 26.3 3/19 15.8 11/19 57.9 Under the weather 5/18 27.8 5/18 27.8 8/18 27.8 A red Herring 2/18 11.1 3/18 72.2 13/18 72.7 Play gooseberry 5/19 26.3 2/19 10.5 12/19 63.2 A canary in a coal mine 6/19 31.5 1/19 5.3 12/19 63.2 To have someone over a barrel 11/19 57.9 7/19 36.8 1/19 5.3 Get the sack 8/18 44.4 1/18 5.5 9/18 50 Hear it on the grapevine 12/19 63.2 2/19 10.5 5/19 26.3 Jump on the bandwagon 12/17 70.6 2/17 11.8 3/17 17.6 When the chips are down 2/19 10.5 4/19 21.1 13/19 68.4 Bite the bullet 8/15 53.3 1/15 6.7 6/15 40 Stick to your guns 9/19 47.4 6/19 31.6 4/19 21.1 Kick the bucket 5/18 27.8 4/18 22.2 9/18 50 Total 108/274 39.4 47/274 17.5 118/274 43.1

The total score shows that 39.4% of the students gave correct answers which is a decrease of 29.5 percentages. 17.5% gave an incorrect answer and 43.1% gave no answer. The results of the second post-test imply that written context, to some extent, has a better effect on long-term memory as compared to etymological elaboration. However, the groups differ only by 4.9 percentages. The etymology group has forgotten 2.3 percentages more of the idioms in comparison to the written context group, and they have a decrease in all idioms whilst the context group maintained their results on 3 of the idioms; to show someone

the ropes, hear it on the grapevine and jump on the bandwagon. The fact that these idioms

were the ones which turned out to be the easiest to remember for many students in the group, might be due to their initial words. They seemto help the students interpret and remember them more easily. Both hear it on the grapevine and jump on the bandwagon have similar initial words to höra det ryktesvägen and hoppa på trenden. This connection seems to have helped the students remember these idioms which is in line with other research findings (Cooper, 1999 and Vasiljevic 2015). Searching for expressions in their first language which

might help them interpret the idiom, is a frequently used strategy among L2 learners

(Karlsson, 2013, see section 2.1). The initial words of the idiom to show someone the ropes seem not to have been as hard to comprehend and remember either, as the initial words are well known to the students, and this helps them to draw a conclusion as the meaning can be inferred from the meaning of its constituents (Glucksberg, 2000, see section 2.1). Other idioms seem to have been harder to comprehend and therefore in many cases even hard to remember, e.g. a gravy train, a red herring, kick the bucket and get the sack. These were the idioms that were the hardest for the etymology group to remember. These idioms seem to be more culturally embedded, which might be the reason why many students were unable to remember them for long. A canary in a coal mine is the idiom which was easier for the etymology group to remember, and which seems to have been stored in the long-term memory in many of the students. This might be because the etymology of this particular idiom adds sympathy; it actually evokes sensory referents. This is likely to add to the creation of an inner image that will help retention, which is in line with DCT i.e. the idiom becomes dually coded (see section 2.2).

The results shown in table 5 and 6 as well as 7 and 8 above, show that written context elaboration turned out to be the most effective technique on immediate, as well as long term retention, when teaching idioms among Swedish 9th grade students.

Boers, et al found in their 2002 experiment that, etymological elaboration had the greatest impact on transparent idioms and insignificant on opaque idioms. Boers, et al (2004) implied that, the origin of many opaque idioms might seem too far-fetched causing the students to lose their motivation. This is a likely scenario among the students in this study as well. There is a possibility that, the students were unable to fully understand the etymology given, or was unable to see the connection between origin and usage. According to DCT, etymological elaboration should contribute to a creation of mental images which helps

retention. However, when regarding the results in Kraemer et. al (2009), which is described in more detail in section 2.2.3, it is possible that there is a majority of verbalizers among the students in the etymology group and that they lack the ability to visualize what is presented to them. The present study shows, however, that etymological elaboration does benefit retention, though not as much as when the idioms are placed in written context.

In Afram’s study (2016), written context also turned out to be a successful strategy when it comes to comprehension. Even though the aim of this study is to consider the most effective strategy for idiom retention, comprehension is still an important factor in retention. There is a possibility that, the students who were presented with the idioms in written context found the given context more helpful compared to the group who received etymological explanations. The students’ confidence when speaking English and their language maturity might also have had an impact on the results.

5. Conclusion

The aim of this paper was to use etymological elaboration and written context in the teaching of idioms to 9th grade students and consider which technique was more efficient

when it came to retention of the target idioms. Two groups participated in the study; one with 18 students, the other with 19 students. The first group was taught the idioms together with their etymology, the other group was taught the idioms in written context. The results show that written context seems to be more effective on retention than etymological elaboration, immediate as well as long-term. According to Lakoff and Johnsson (1980, 1999 cited in Paivio, 2006), teaching the roots of specific vocabulary is likely to present meaning to something that might seem abstract to the learner. The present study show that this is true to some extent, as etymological elaboration benefits retention. However, many idioms seem to remain abstract to the students even if they are presented with the idioms’ etymology.

The generalizability of the findings in this study is, however, limited due to the small number of participants. Another important factor to consider, is whether the opaque idioms used in this study might not be opaque to all students due to the fact the not all students had Swedish as their mother tongue. Both teaching and learning strategies did, however, have a positive effect on retention and should be adapted when teaching idioms in school. Many of the students believed that the strategy helped them remember.

Not only is this a small scale study, and the strategies’ effect on retention needs to be investigated further, but in addition it is worth considering whether 9th grade students need

more time, that it is too soon in their L2 language development. It would therefore be possible to conduct a similar study on older students, for example students over the age of 19, to see whether the results come out differently. Preferably, the study should be run on a larger group in order to get a more reliable support for the findings and on an L1 homogenous group. Another research angle might be to investigate whether it would further enhance retention of English idioms on 9th grade students if they were given more idiom knowledge and awareness in their L1 before being taught opaque idioms in another language. In the present study, gender has not been an issue and the researcher did not ask about gender in the questionnaire. However, considering the groups, there was a clear majority of male students in the context group. In the etymology group there seemed to be a more even number. Regarding the results on post-test 1, on stick to your guns, the context group gave more than twice as many correct answers compared to the etymology group. A canary in a coal mine, however, received considerably more correct answers among the students who were given its etymology. A possible approach would be to investigate whether there is a difference between what idioms male students more easily remember, compared to those female students remember.

6. References

Afram, E. (2016). Contextualization of L2 idioms (written context versus still pictures) and its effect on students’ retention. Halmstad University, Halmstad

Bagheri, M. S., & Fazel, I. (2010). Effects of Etymological Elaboration on the EFL Learners’ Comprehension and Retention of Idioms. Journal of Pan-Pacific Association of Applied

Linguistics, 14(1), 45-55.

Boers, F. (2008). Understanding Idioms. Med Magizine. 49 [online]

http://www.macmillandictionaries.com/MED-‐Magazine/February2008/49-‐LA-‐Idioms-‐ Print.htm [Accessed 14 December 2016].

Boers, F & Demecheleer, M & Eyckmans, June. (2004). Vocabulary in a Second Language:

Selection, Acquisition, and testing. Etymological elaboration as a strategy for learning idioms.

Ch. 4. Philadelphia, NL: John Benjamins Publishing Company. ProQuest ebrary. Web. 15 September 2016

Kraemer, J.M., & Rosenberg, L.M., & Thompson-Schill, S. (2009). The Neural Correlates of Visual and Verbal Cognitive Styles. The Journal of Neuroscience, 29(12), 3792–3798.

Liontas, J,. 2003. Killing Two Birds with One Stone: Understanding Spanish VP Idioms in and out of Context. American Association of Teachers of Spanish and Portuguese, 86 (2), p.289-301.

Çetinavcı, B.M., 2013. Contextual factors in guessing word meaning from context in a foreign language Uludag University School of Foreign Lanuages, Turkey

Collins Cobuild. (2012). Idioms Dictionary. Glasgow: HarperCollins Publisher.

Cooper, T. (1999). Processing of Idioms by L2 Learners of English. Teachers of English to

Speakers of Other Language, Inc.,p. 233-262.

Craik I.M.F., 2002 Levels of processing: Past, present... and future?, Memory, 10(5-6), p.305-318.

Craik , I.M.F., & Lockhart R.S., 1972. Levels of Processing: A Framework for Memory Research. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behaviour. 11, p.671-684

Craik, I.M.F., & Lockhart R.S., 2008. Levels of Processing and Zinchenko's Approach to Memory Research, Journal of Russian & East European Psychology, 46(6), p.52-60. Gardner, H., & Hatch, T., 1989. Multiple Intelligences Go to School: Educational Implications of the Theory of Multiple Intelligences. [online]

idiom comprehension. Halmstad University: Halmstad.

Kovecses, Z., 2002. Metaphor. A practical introduction. Oxford University Press

Lakoff, G., 1992. The Contemporary Theory of Metaphor. To Appear in Ortony, Andrew

Metaphor and Thought (2nd edition), Cambridge University Press

Nation, P. (2001). Learning Vocabulary in Another Langauge. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Noroozi, I., & Salehi, H., 2013. The Effect of the Etymological Elaboration and Rote Memorization on Learning Idioms by Iranian EFL Learners. Journal of Language Teaching

and Research, 4, 845-851.

Paivio, A., 2006. Dual Coding Theory and Education. [online]

http://www.csuchico.edu/~nschwartz/paivio.pdf [Accessed 5 October 2016]. Razmjoo, S. A., & Songhori, M. H., & Bahremand, A., 2016. The Effect of Two

Attentiondrawing Techniques on Learning English Idioms. Journal of Language Teaching

and Research, 7(5), p.1043-1050.

Sadoski, M. & Paivio, A.,2001. Imagery and Texts. A dual Coding Theory of Reading and

Writing. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers. Mahwah, New Jersey.

Swinney, D. A. & Cutler, A., 1979. The access and processing of idiomatic expressions.

Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 18, p. 523-534.

Electronic sources:

Ginger, 2013. [online] Available at: http://www.gingersoftware.com/content/phrases/under- the-weather/#.V-5zlZOLSt8

http://www.gingersoftware.com/content/phrases/jump-on-the-bandwagon/#.V-4jepOLSt8

Idiom Origins, 2016. [online] Available at: http://idiomorigins.net/ [Accessed 20 September 2016].

Macmillan Education, Tim Bowen. [online] Available at:

http://www.onestopenglish.com/community/your-english/phrase-of-the-week/phrase-of-the- week-i-heard-it-through-the-grapevine/145660.article [Accessed 26 September 2016]. Share America, Dough Thompson. 2014. [online] Available at:

https://share.america.gov/english-idiom-canary-coal-mine/. [Accessed 20 September 2016]. Skolverket. (2011) Curriculum for the compulsory school, preschool class and the

leisure-time centre 2011. [online]

http://www.skolverket.se/om-skolverket/publikationer/visa-

enskild-publikation?_xurl_=http%3A%2F%2Fwww5.skolverket.se%2Fwtpub%2Fws%2Fskolbok%2 Fwpubext%2Ftrycksak%2FRecord%3Fk%3D2687. [Accessed 21 October 2016].

Team of Lalit Kumar, 2015. [online] Available at: http://techwelkin.com/when-chips-are- down-meaning-and-origin-of-phrase-idiom [Accessed 26 September 2016].

The Free Dictionary.[online] Available at: http://idioms.thefreedictionary.com/over+a+barrel

[Accessed 20 September 2016].

The Guide to Grammar and Writing, John Friedlander. [online] Available at:

http://grammar.ccc.commnet.edu/grammar/composition/abstract.htm [Accessed 29 October 2016].

The Free Dictionary.[online] Available at: http://idioms.thefreedictionary.com/over+a+barrel

[Accessed 20 September 2016].

Etymology group:

Student: Mother Tongue Results pre-‐test Results post-‐

test 1 Results post-‐test 2 01 Swedish 0/15 15/15 4/15

04 Swedish 1/15 5/14 0/14 05 Swedish 1/15 13/14 8/14 06 Swedish 0/15 9/15 6/15 07 Swedish 1/15 14/14 11/14 08 Swedish 0/15 11/15 6/15 09 Greek 0/15 14/15 10/15 10 Swedish 0/15 9/15 6/15 11 Swedish 0/15 2/15 0/15 12 Arabic 0/15 3/15 0/15 14 Swedish 0/15 15/15 10/15 15 Swedish 0/15 10/15 4/15 16 Swedish 0/15 3/15 1/15 17 Arabic 0/15 14/15 7/15 18 Armenian 0/15 13/15 5/15 19 Swedish 0/15 9/15 7/15 20 Dari 0/15 9/15 4/15

Written context group:

Student: Mother tongue Results pre-‐test Results post-‐

test 1 Results post-‐test 2 01 Swedish 0/15 12/15 5/15 02 Swedish 1/15 9/14 3/14 03 Swedish 0/15 12/15 5/15 04 Swedish 1/15 9/14 3/14 05 Arabic 0/15 10/15 4/15 06 Somali 0/15 10/15 7/15 07 Swedish 0/15 9/15 7/15 09 Swedish 1/15 14/14 10/14 10 Pushto 0/15 15/15 11/15 11 Arabic 0/15 13/15 9/15 12 Pushto/Dari 1/15 7/14 4/14 13 Swedish 0/15 14/15 8/15 16 Swedish 1/15 14/14 8/14 22 Swedish 0/15 2/15 1/15 23 Filipines 0/15 4/15 2/15 24 Swedish 0/15 3/15 3/15 26 Swedish 0/15 9/15 7/15 32 Swedish 0/15 8/15 3/15 33 Swedish 1/15 11/14 6/14

Questionnaire

1. What is your mother tongue? Swedish

Other_______________________

2. Do your parents have Swedish as their mother tongue? Yes, both of them.

One of them. None of them.

3. Have you been living in an English speaking country for more than 3 months? Yes

No

4. Do you use idioms when you speak Swedish or your mother tongue? Yes

No

Not that I’m aware of.

5. If you answered yes in question 4. Please grade to what extend you believe you use them.

1 2 3 4 5 seldom Very often 6. Do you use English idioms when you speak?

Yes No

Not that I’m aware of

7. If you answered yes in question 6. Please grade to what extend you believe you use them.

1 2 3 4 5 seldom Very often

8. Have you ever been taught English idioms in school prior to this? Yes

No

9. How important do you think it is to learn idioms? Please grade your answer. 1 2 3 4 5

Not important Very important

10. How difficult did you find the target idioms when you saw them for the first time? Please grade your answer.

1 2 3 4 5 Very difficult Very easy

11. If you are to guess how many of the target idioms you have learnt. Please grade you knowledge on a scale from 1-5.

1 2 3 4 5

None almost all

12. To what extend do you believe that the method of presenting the idioms have helped you in order to remember them?

1 2 3 4 5 Not at all Very much 13. What method do you normally use when you practise vocabulary? Please describe your method in your own words:

___________________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________

Thank you for your cooperation😃

PO Box 823, SE-301 18 Halmstad Nina Bergstrand