School of Education, Culture and Communication

Learning by gaming?

A comparison of how Swedish upper secondary male and

female students learn English

Degree Project in English

Annette MattssonSupervisor: Thorsten Schröter Spring 2020

Abstract

Earlier research has suggested that online gaming can be an effective way of acquiring English as a second or foreign language. It can both increase language proficiency (vocabulary or oral proficiency) and have a positive impact on affective filters such as motivation or willingness to communicate. The present study further investigates if habitual playing of massively multiplayer online (MMO) games results in achieving higher grades in English as a foreign language (EFL) for the Swedish upper secondary students. Possible gender differences regarding the acquisition of English and grades in the subject are also investigated to see if the female students play MMOs to the same extent as the males do and if the female students’ higher grades can be connected to gaming.

78 upper secondary school students answered a questionnaire about their English-language-related activities in their spare time and their online gaming habits in particular. The students’ most recent grades in the English subject were gathered to see if the habitual gamers achieved higher grades.

The results show that most of the males play MMOs and that most of the females do not. The males also engage more in other English-language-based activities in their spare time than the females do. Still, the informants’ English grades are similar between the genders. Females seem to learn more English in school and the males more in their spare time. However, the group of gamers playing MMOs 4-8 hours a week or more achieved higher grades than the rest of the student informants.

Keywords: upper secondary school, Sweden, EFL, gender differences, language acquisition,

Table of Contents

1. Introduction ... 1

2. Background ... 2

2.1 English in Sweden and in Swedish schools ... 2

2.1.1 Grades and gender in Sweden ... 3

2.2 Second and foreign language teaching and learning ... 3

2.2.1 Explicit and implicit learning ... ..3

2.2.2 Interaction and learning ... 4

2.2.3 Affective filters ... 5

2.3 Swedish youth and media habits ... 5

2.4 Online games – background and categorization ... 6

2.5 Learning by gaming ... 7

3. Methods and material ... 9

3.1 Data collection ... 10

3.2 Analysis……….…….10

3.3 Ethical principles……….……….…12

4. Results ... 12

4.1 The questionnaire..…….……….………12

4.1.1 Internet use, Online gaming and gender……….……….….………..…12

4.1.2 Variables that affect learning……….……….…14

4.1.3 Gender and grades……….……….………14

4.1.4 Male online gamers and grades……….………..…..…15

4.1.5 Females, grades and language acquisition……….………..….…....…..17

4.1.6 Gamers, non-gamers and grades………..……18

4.1.7 Summary of the findings.……….……….……….……18

5. Discussion……….……….……19

6. Conclusion……….……….…22

List of references ... 23

Appendixes……….26

Acknowledgements

Completing a degree project essay of this type while having a fulltime job, house and family, has been proven tough. Therefore, I would like to thank my family, friends and colleagues for cheering me on and not allowing me to give up. Appreciation and gratitude is given to Thorsten Schröter for supervising this study and for the feedback I received – thank you for all the hours you put in. I am grateful to Filippa Bogen for her advice on layout issues and Carol Farber for proof-reading my work. I also give thanks to a frequent gamer I know, for providing information on online games. Last, but not least, a great thank you to my son for giving me the inspiration to write about online games and English acquisition and also for the detailed information about different types of on- and offline games.

1

1. Introduction

This degree project aims to look more closely at online gaming and English as a Second Language (ESL). The subject caught my interest because my son learned to speak English before he had one single English class. At the age of six, he started playing online games on his

Playstation and watching many hours of Youtube videos on the Internet. One day, when he was

around seven years old, while I was speaking to my American friend over dinner, my son said in perfect English: “I can understand what you are saying, you know”. I was fascinated. He had spent hours playing with gamers worldwide – reading, speaking, listening and writing in English. According to Sundqvist (2009), though based on an even earlier source, Swedish students’ spare time activities involving English increased dramatically in the mid 1990’s (Sundqvist, 2009, pp. 2-3). This included online games, which attracted players worldwide. The fact that I focus on online gaming in particular in this study is due to the features of online games. It is most often conducted in English, so the player will have to read and listen to instructions and dialogue in English, write in the chat, talk and listen to other gamers in English, in order to participate in the game with gamers from across the world. Sundqvist confirms that English is the dominant language on the Internet and the lingua franca when playing video/computer games online (Sundqvist, 2009, p. 28). Gaming is a potentially highly interactive activity, unlike more passive activities such as watching TV or listening to music. Sundqvist found that online gamers were mostly boys, especially when it comes to the more interactive type of games, and that this might give them an advantage with respect to English proficiency (Sundqvist, 2009, p. 131).

The aim of this study is to investigate if online gaming (video or computer games with multiple players) has had an impact on the Swedish upper secondary school students’ grades, and if there is a noticeable difference between the genders. To investigate this, I distributed a questionnaire in four English classes and interviewed the students’ teacher. In addition, the students were asked to reveal their latest English grade by answering a question in the questionnaire. The grade was used for comparison to the students’ online gaming habits.

The concrete research questions I am looking at are:

RQ1: Do habitual massively multiplayer online gamers achieve higher grades than the non-gamers?

2

2. Background

A presentation of English in Sweden and English as a subject in Swedish upper secondary schools will initiate the background section of this study. It is followed by an account of Second Language Acquisition (SLA) theories and their relevance to research on online games and second or foreign language learning. Thereafter, Swedish children’s and adolescents’ use of the English language and use of media in their spare time is accounted for, followed by a background on online/offline video and computer games and the categorization of them. Finally, earlier research on gaming and language proficiency is presented.

2.1 English in Sweden and in Swedish schools.

The English language is believed to have grown into a world language because of British and American influence in the world, becoming the main language for e.g. science and business and used nowadays as a global lingua franca (Sundqvist, 2009, p. 27). The influence of English on the rest of the world has increased even further in the last 20 years since English is the major language on the Internet. Needless to say, the Swedish population today experience massive exposure to English in their everyday lives.

As described in the curriculum for the English subject at upper secondary school in Sweden, published by the Swedish National Agency of Education (Skolverket, 2011-2018), the English language surrounds us in our everyday lives and is used in diverse areas such as culture, politics, education and economics. According to the curriculum, knowledge in English can also give new perspectives of the world, increased possibilities for contacts and a greater understanding for different ways of life. This corresponds well with the online gamers international environment where the gamers learn from each other.

The curriculum (Skolverket, 2011-2018) further states that the purpose for the teaching of English is to have the students develop their language and knowledge of our environment so that they can, want and dare to use English in different situations for different purposes. Students shall be given opportunities to express themselves, interact with others in speech and writing and also adjust the language to different situations, purposes and receivers.

Online gamers experience hours of opportunity to develop their language competences in a world full of natural English speech in different situations (different games offer different sets of environments, words, tasks etc.) and gaming has also been shown to reduce anxiety of speaking (Horowitz, 2019, p. 388). Since online gaming is closely linked to the students’ own interests, it is likely to increase motivation for learning English (Olsson, 2016, p. 50).

3

2.1.1 Grades and gender in Sweden.

According to a government report on gender equality at school (DEJA, 2009), girls have for a long time tended to achieve higher grades than boys in most subjects in Swedish schools. This is also true for English, but boys have caught up with the girls’ results in that subject, while other subjects like Swedish or math have had stable gender differences over time (DEJA, 2009, pp. 127, 148). For example, in the school year 2018/19, the formerly substantial gender difference regarding the highest grades had decreased to 4.7 % percentage points, with 38.8 % of the girls and 34.1 % of the boys receiving an A or B in English, almost a 15 % improvement for the boys since the year 1996/97 (Skolverket, Sveriges officiella statistik). This begs the question: if the girls still outperform the boys in most subjects, why are the boys catching up in English specifically?

2.2 Second and foreign language teaching and learning.

Tornberg (2005) states that Second Language Acquisition (SLA) theory has come to consider the oral part of language learning increasingly important. Further, she argues that collaborative learning (groupwork) and interaction is beneficial for knowledge and proficiency development (p. 135). Tornberg also claims that discussions, dialogues and conversations should be natural and authentic, not created (p. 138).

Lightbown & Spada (1999) state that communicative language teaching is considered an effective way of learning (p. 40). There are learner variables that interact with each other, including intelligence, aptitude, motivation, attitudes, personality and age (pp. 49-68). They further state that the difference between a natural and an instructional language learning environment is that the natural setting (e.g. workplace, other country, talking to native speakers) entails authentic language and situations, without correction, and that language is not presented step by step, that there is plenty of exposure to the language in many situations with many people and what is important is getting the meaning (content) across, instead of focusing on form and structure (pp. 91-95). This is an exact description of the environment in Massively Multiplayer Online (MMO) games.

2.2.1 Explicit and implicit learning.

Olsson (2016) differentiates between explicit (conscious) and implicit (unconscious) learning, stating that implicit learning mostly occurs outside of school and explicit learning in school, claiming that implicit learning is a more effective way of acquiring new knowledge (pp. 23-26). Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) is the concept of school subjects being

4

taught using English as the medium of instruction (Olsson, 2016, p. 13). The CLIL concept is used in certain Swedish schools to raise the amount of authentic English the students are exposed to. Furthermore, there are certain similarities between the CLIL classroom and the online gaming environments. The concept of immersion means being placed in an environment where one is surrounded by and cannot avoid contact with the target language (here the English language). Immersion is a quality found in the online gaming environment, and supposedly in the CLIL classroom as well, as Sylvén and Sundqvist (2012) had found when their research compared the two separate environments (Sylvén & Sundqvist, 2012b, pp. 113, 126).

2.2.2 Interaction and learning.

The proponents of the interactionist theory argue that language is learned through social interaction (Lightbown & Spada, 1999, pp. 42-46). Vygotsky (1978) claimed that one can reach The Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) by learning from an interlocutor who has more knowledge (pp. 23, 44), and according to the Interactionist theorists, the best way to acquire a second language is by conversational interaction (Lightbown & Spada, 1999, p. 43). Waring (2018), however, argues that: “while theoretical arguments for interactional competence have played a decisive role in reconceptualizing the field of language teaching, to reap the benefits of such arguments in actual teaching would require greater specification, at the level of visible conduct, of what such competence entails” (p. 59).

Sylvén & Sundqvist (2012a) refer to contemporary researchers inspired by sociocultural theory (SCT) and imply in their research that the online gaming environment is an excellent place for SLA. Players have to communicate in order to be able to participate in the game (receive input and produce output) and also be successful in it (gain property, weapons and armour, win battles, advance to the next level etc). Sylvén & Sundqvist (2012a) claim that the environment in Massively Multiplayer Online Role Playing Games (MMORPGs) offer several factors that are important in SLA theory and for what is considered effective second language (L2) learning. MMORPGs provide comprehensible input and scaffolding opportunities (a learner receiving support from someone that has more knowledge, in order to learn to master the new knowledge), through interaction as well as high motivation for the gamers according to Sylvén & Sundqvist (2012a, p. 305). Olsson (2016) reasons that: “Students may be pushed to develop their language output in communication with peers, e.g. when playing multiplayer games or

5

2.2.3 Affective filters.

According to Lightbown & Spada (1999), Krashen’s Affective Filter Hypothesis (pp. 39-40) refers to a learner’s motives, needs, attitudes and emotional states. Affective filters can determine whether or not we are successful in learning a second language. A learner’s emotions can for instance affect motivation and the willingness to communicate (WTC). According to Olsson (2016), the learning environment seems to affect learning to a great extent, meaning that learners may be more or less enthusiastic and motivated to learn in different environments. Youth choosing to spend their personal time on activities where they use English are more likely to have high motivation, because engagement in such activities are voluntary (p. 50). In short, online games offer a learning environment through interaction with interlocutors sharing a common interest, whom the learner collaborates with to solve authentic problems. This is usually done in English. The gamers play willingly in their spare time which also creates affective outcomes such as high motivation, lower anxiety, increased willingness to communicate and positive attitudes towards learning. Learning the language might not be the gamers primary goal, but is a welcome bonus.

2.3 Swedish youth and media habits.

Swedish youth in general, spend a considerable amount of time engaging in spare time activities conducted in English, a concept named Extramural English (EE) by Sundqvist (2009), referring to e.g. watching films, using social media, listening to music or playing online games in English. Statens medieråd1 published a report in 2019 on Swedish children’s and adolescents’ media habits. According to the report, to engage in social media is one of the most common daily activities, as is listening to music, watching Youtube clips, playing computer or video games and playing on Ipads/tablets or mobile phones (pp. 10, 28). Swedish youth between the ages of 9-18 years also seem to be reading less books and magazines than earlier years (p. 30).

There are considerable gender differences, in that boys tend to play more video or computer games than the girls (p. 10), for example, among 13-16-year-olds, 52 % of the boys play online games every day compared to 5 % of the girls (p. 28). The girls use social media to a higher degree than the boys, however (p. 27). There is also gender segregation when it comes to what types of games girls and boys choose to play in all age groups (pp. 44-45).

6

Boys in all age groups (9-18 years old), played online games, mostly of the MMO type, with the most commonly played ones being Fortnite, Overwatch, League of Legends and

Counterstrike. World of Warcraft seemed to have lost popularity. The girls more usually played The Sims, Minecraft or Candy Crush Saga. It seems very rare for girls to play MMO type games

(p. 44). The gaming world thus appears to be largely gender segregated, with only Minecraft being played by both genders to a considerable extent, but only in the age group 9-12 years. In the other games, girls and boys very seldom seem to meet because of their different gaming preferences (p. 45).

Sundqvist & Sylvén (2014) used a questionnaire and a language diary with English learners in grade 4 in order to investigate their L2 related activities outside of school, specifically looking at their online digital gaming habits. In doing so, they found that boys spent statistically significant more time on playing digital games in English and watching English films than the girls, who preferred activities in Swedish (Sundqvist & Sylvén, 2014, pp. 3, 8).

2.4 Online games – background and categorization.

There are different genres of online games. The term FPS stands for First Person Shooter and games like Counter-Strike (CS), Overwatch and Call of Duty belong to this category (Ray, 2012; Wikipedia). One of the largest online games with the most players, used to be World of

Warcraft (WoW) (Löfving-Johansson, 2013, p. 11). WoW belongs to the category of MMORPG

games (Massive Multiplayer Online Roleplaying Games) and is a fantasy game played from a third-person perspective. WoW had around 12 million players between the years 2008-2010 and by 2015 there were approximately, 5.5 million active players left, but since an update of the game was released in 2019 the number of players are now increasing again (Myrén, 2020). A more recent Massively Multiplayer Online game (MMO) is Fortnite which has gained in popularity with over 125 million players (Epic Games, 2017).

Online games, no matter what category, offer the players the possibility to chat with each other through writing and sometimes also talking through a headset. The exception to this is offline single-player games such as The Sims, a strategic life-simulation Real-Time Strategy (RTS) game (Museum of Play, Wikipedia). According to Löfving-Johansson (2013), WoW and CS were mostly reported being played by boys and games like Sims or Burnout by girls, and since girls more often play offline, they do not experience the same input and output as the boys do (Löfving-Johansson, 2013, p. 11). Some of the online games one can choose to play in teams, which means that one needs to cooperate and communicate with teammates in order to be

7

successful in a mission. An online game can have as few as 2 players and up to over 30 players in one team (Horowitz, 2019, p. 387).

Löfving-Johansson (2013) stated that it was impossible for gamers to avoid English if they wanted to play online video or computer games. The dialogues and instructions are all in English, which made her believe that students may learn a lot from such games (Löfving Johansson, 2013, p. 5).

2.5 Learning by gaming.

Sylvén & Sundqvist (2012a) conducted an investigation on younger Swedish children (39 boys and 47 girls) and their English proficiency and compared it to their online gaming habits. The children were 11 to 12 years of age and the data collected consisted of a questionnaire, a language diary and three proficiency tests. Special attention was payed to certain forms of online gaming, namely MMORPGs. By differentiating between non-gamers, moderate gamers and frequent gamers, Sylvén & Sundqvist found that the frequent gamers were mostly boys and that they had better results than the others on all of the proficiency tests (pp. 311-313). Sundqvist (2015) interviewed a 14-year-old boy in Sweden who had taught himself English by playing online games in his spare time (p. 352). Sundqvist stated that: “Elements of gaming (in particular, competition, stories, and escapism) appealed to Eldin, thereby indirectly contributing to his successful learning of English” (Sundqvist, 2015, p. 352).

Sylvén & Sunqvist (2012a) differentiated between two types of games in particular: MMORPGs and offline single player games (Sylvén & Sundqvist, 2012a, pp. 304-305). Hou (2011) had found that certain elements in digital games such as rules, competition, goals, fantasy, entertainment and challenge were beneficial to learning motivation (p. 191). Results indicated that the informants engaged in peer and learning interaction to a certain extent and that the game Talking Island (multiplayer online) combined with situated problem-solving tasks could have potential for educational games in the future (Hou, 2011, p. 193).

Puimège & Peters (2019), studying Flemish children aged 10-12 years, found that frequent gamers knew more English words than non-gamers and that the boys played more games in English than girls, which was a probable cause for them having a larger English vocabulary (pp. 945, 967). Based on their research, Puimège & Peters claimed that: “This finding attests to the effectiveness of extramural English for incidental vocabulary acquisition even without formal instruction. […] The factor Gaming and Video Streaming was the only predictor of word

8

knowledge in the meaning recall test, which supports previous claims that computer games have

great potential for L2 vocabulary learning in young learners” (p. 966). Butler, Someya & Fukuhara (2014) investigated the online instructional games and learning kit

connected to a standardized English proficiency test for 4-12-year-old English learners in Japan, to find out how the student’s prior English abilities and online experiences affected their learning, performance and anxiety. Butler et al. claimed that Computer Assisted Language Learning (CALL) and computer-based assessment held promise for young learners up to the age of 12, due to possibility of presenting contextualized cues via animation, audio, video and other multimedia. The various types of non-verbal information and instant feedback that computers offer may hold children’s attention, motivate them, and in the process benefit their learning. The authors’ findings suggested that a contextual game-based learning environment could be exploited as a useful tool to support language learning. The learning performance and anxiety created by the environment, however, were affected to various degrees by the levels of students’ prior knowledge (Butler et al., 2014, pp. 265-268). They also found that a few of the games did not seem to be effective learning tools, even if they were popular among the students (p. 273).

Yang & Quadir (2018) created an MMORPG-type educational game to support English learning, with the purpose of investigating if the students’ prior knowledge of English and gaming affected their performance. They found that the students’ prior knowledge in both areas affected their language learning and anxiety levels to varying degrees (Yang & Quadir, 2018, pp. 174-186).

Hung, Yang, Hwang, Chu & Wang (2018) analyzed 10 journals in Digital Game Based Language Learning (DGBLL) earlier literature, including 47 different studies (p. 89) to supply a summary of the so far existing empirical evidence regarding the impact of digital games on language education between 2007 and 2016. Hung et al. (2018) found that most research showed positive results in regards to student learning (most commonly related to psychological or affective states and language acquisition). The DGBLL environment offered immersive exposure to the target language, showed lowered anxiety of using the language and also impacted other affective barriers. Studies revealed increased use of the target language through interaction in the games (p. 90). Hung et al. found that: “The nature of digital games can be of vital importance in shaping the processes and outcomes of learning by gaming” (Hung et al., 2018, p. 90).

9

Finally, gaming was found to show positive results on communicative competence, collaboration, general attitudes and perceptions, motivation, engagement, and willingness to communicate (p. 99). The research overview also showed that MMORPG players outperformed their counterparts when it came to effective communication strategies, (including politeness or humor) showing development of sociolinguistic competence (p. 100).

According to Sykes (2018): “Research have shown that digital games support learning in a variety of areas. Benefits include the creation of a learning community, the opportunity for intercultural learning, access to a diversity and complexity of written texts, evidence of authentic socioliteracy practice, and affordances for the sociocognitive processes of learning and language socialization, especially of lexis” (p. 220).

Horowitz (2019) examined the relationship between the informal environment of MMOs and anxiety of using English as a foreign language for Spanish-speaking Puerto Rican students. He also investigated how many hours the informants spent on playing such games (p. 379), in order to map out how it affected the students’ willingness to communicate (WTC) in the English classroom. Horowitz stated that: “The lack of emphasis on practice within the classroom, as well as the lack of an authentic environment outside, can potentially reduce the willingness to communicate (WTC) and increase foreign-language anxiety (FLA)” (Horowitz, 2019, p. 382). He claimed that “motivation is key” (p. 383). Horowitz reasoned that the online gaming environments are immersive, due to the fact that the gamers have experiences that are like real-life situations (p. 385), that gamers belong to online teams, clans or communities (pp. 387-388), and that they actually consider their online friends as important as friends they have and meet in real life (p. 389). Horowitz argued that: “It is likely that the communal nature of many online games, such as MMORPGs, along with the high degree of interactivity in authentic situations, helps lower player language anxiety and increase a player’s willingness to communicate” (Horowitz, 2019, p. 388).

3. Methods and material

The main aim of this study is to identify if habitual gamers of the interactive MMO type games achieved higher grades in the English subject. The study also investigates if females played these types of online games to the same extent as the males and therefore partly shows if the females learned English differently from the males. To achieve this aim, I have administered a questionnaire (see Appendix 1) to upper secondary students in a medium-sized city in central

10

Sweden and interviewed their teacher (see Appendix 2). The students also provided me with their latest English grade by writing it in the questionnaire.

3.1 Data collection.

The study is both qualitative and quantitative (Denscombe, 1998, p. 203) and results accounted for through descriptive statistics. Written statements from the students, which have been incorporated into the analysis are also included. The data collection started when I contacted a teacher in an upper secondary school, asking for his assistance and permission to use his students as informants for this study. The teacher also asked permission from the principal of the school. When permission was granted, a questionnaire was distributed in English classes on booked dates. The students were asked if they were willing to participate in the study, and it was emphasized that it was voluntary. The teacher also agreed to be interviewed.

3.2 Analysis.

The questionnaire was computer written and handed out by me in paper form in the informants’ English classes. Since I was present during the data collection, the students had the possibility to ask questions if they were confused about any parts of the inquiry. They were also allowed to answer in Swedish if they wished to do so. Information was given before they filled in their answers. A total of 100 students in upper secondary English courses 5, 6 and 7 participated. The questionnaire took around 20-30 minutes to fill out and was brought in before I left the classrooms.

Among the participants, there were 58 students from the basic English course 5 (two classes), 28 enrolled in course 6 (one class) and 14 from the most advanced course 7. Eight of the informants did not answer the questionnaire properly (having given obviously dishonest answers or by not answering a large share of the questions), so I decided to exclude those questionnaires from my study. English courses 5 and 6 are compulsory in the students’ study program, while English 7 is optional, and the students taking it are particularly motivated to improve their English. Because of the special status of this course, and since there were only 14 students enrolled in it, I decided to exclude this group from the analysis. I thus ended up with 78 fully answered questionnaires, representing 36 male and 42 female informants from the courses English 5 and 6.

A semi-structured interview with the student informants’ English teacher, henceforth referred to as Mr Andersson, was conducted to investigate his experience regarding online gaming in

11

relation to English language learning and teaching. I also asked about gender differences in this respect. The interview was carried out in Mr Andersson’s office at the school and lasted 45 minutes. The answers were recorded and also written down to some extent during the interview. Since I did not perform a content analysis of the interview, it is not included in the data, but merely just a few of Mr Anderssons views on the matter, mentioned in the discussion section (section 5).

The main purpose of the research was to investigate if online gamers achieved higher grades in English, as well as gender differences in gaming habits and the connection to the students’ results (grades). However, I also needed to ask the students about other factors that can be a reason for why a student achieves a higher grade. The variables I investigated were high motivation, other EE activities apart from interactive online games or previous knowledge of English (e.g. achieved from living in an English-speaking country).

The quantitative analysis includes calculating basic descriptive statistics, mainly frequencies or relative frequencies in the form of percentages of occurrence (Perry, 2005, p. 207). The quantitative data from the questionnaire was manually retrieved and was accounted for through bar graphs (Denscombe, 1998, p. 218). The percentages of the males’, females’, gamers’ and non-gamers’ grades were manually calculated for comparisons between the genders, between gamers and non-gamers, as well as with the Swedish grade statistics for the subject of English in upper secondary schools. Earlier research on online gaming and language proficiency, as well as statistics on Swedish children’s and adolescents’ media habits in 2019, provided empirical data to compare with this study.

In the analysis of the questionnaire, the respondents were put into categories according to the amount of time spent on gaming each week: gamers (4-8 hours/week or more) and low

frequency gamers/non-gamers (0-4 hours/week), who reported playing very rarely, never

having played computer games at all or never played them in English online together with others. To find different perspectives I have looked at phenomena separately. The aspects investigated further are gender differences in online gaming, differences in grades for gamers and non-gamers, gender differences in grades, gender differences regarding EE activities, the students’ motivation and other factors that can affect English proficiency. I did this in order to be able to find factors affecting the students’ English grades. I categorized grades A, B and B-C as higher results. The category lower results correspond to grades D, E and F (A being the highest grade in Sweden, E the lowest and F means Fail). Early contact with English is considered to be between the ages of six to seven years at the latest and late language contact

12

in school (when students start taking English in school as subject) is considered to be at the age of 11 years or later. High motivation is the same as “very important” in the questionnaire, quite

high motivation is “pretty important” and the lower scale of motivation some motivation is

“somewhat important”. No student reported having low motivation (“not important”). The term Massively Multiplayer Online (MMO) was used for the online games since it is a more accurate description of the online games the students played.

Qualitative data was also retrieved from the questionnaire, which were analyzed individually, to provide certain details on SLA (second Language Acquisition) variables such as early contact with English, motivation or EE activities other than online games.

3.3 Ethical principles

According to the Swedish Research Council (Vetenskapsrådet, 2017), a researcher must work in agreement with the ethical principles of social study (pp. 8, 69), conducting honest and fair research, not falsifying or altering results or plagiarizing or stealing earlier researchers results (p. 65). The individual informant’s identity, integrity and personal affairs are protected and respected (p. 40) and universal human rights (pp. 29, 72) are abided by at all times. Guidelines concerning informed consent are followed (pp. 74-75). I have achieved this by giving information about the purpose of the study to the students and informing them that participation was voluntary and anonymous (no names were disclosed in the questionnaires) and also that participation could be terminated by the student at any time. I assured the students that the information retrieved would only be used for this study.

4. Results

The results of the questionnaire will be divided in several subsections, based on the themes.

4.1 The questionnaire.

The following sections provide statistical data drawn from the questionnaire. Detailed qualitative data is also accounted for when it is relevant to the study.

4.1.1 Internet use, online gaming and gender.

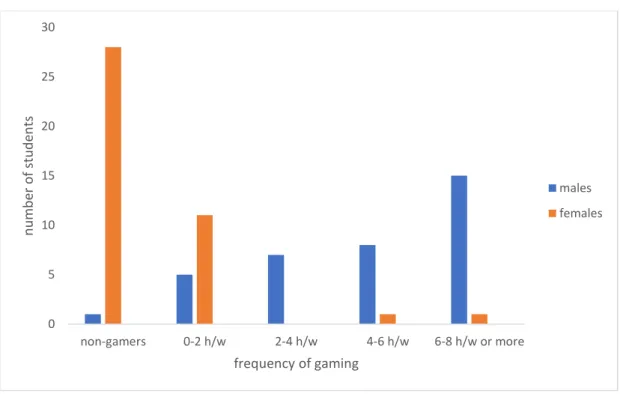

As can be seen in Figure 1, of the 36 males, there were 23 that reported being gamers, playing online games 4-8 hours a week or more. Further, 12 reported playing 0-4 hours a week and only one male could call himself an absolute non-gamer because he had never played online at all (he played other games).

13

The females in the group consisted of 42 students and 28 of them reported being non-gamers. Of the female informants, 11 reported playing 0-2 hours a week at some point in their life for 0-4 years regularly on average and one reported “used to play”. There was only one female reporting to be a gamer playing 6-8 hours a week and only one female gamer playing 4-6 hours a week (see Figure 1).

Of the male gamers (4-8 h/w or more), 17 out of 23 reported using Youtube frequently in English 6-8 hours a week or more (a few wrote up to 30 hours a week or all the time) which seemed to be a common denominator and seemed to be linked somehow to frequent gaming. The female students (the entire group of 42), reported use of social media as their most common English activity, listening to English music and watching TV/movies. If one looks at the overall answers, all the males have played online games to some extent (except one) and the females can mostly be categorized as non-gamers with the exception for three students (two gamers and one used to play).

Figure 1. Online gaming and gender

The Massive Multiplayer Online game (MMO) played together with others most commonly reported as being played in this group was Fortnite. As can be seen in Table 1, males played MMOs and females very seldom did.

0 5 10 15 20 25 30 non-gamers 0-2 h/w 2-4 h/w 4-6 h/w 6-8 h/w or more n u m b er o f stu d en ts frequency of gaming males females

14

Table 1. Games played and gender

game number of females playing number of males playing

Call of Duty 5 17 CS 2 17 FIFA 0 17 Fortnite 7 20 Minecraft 6 0 The Sims 13 0 WoW 1 1

4.1.2 Variables that affect learning.

Out of the 36 male informants, 4 claimed to learn English in school, 28 in their spare time and 4 both in school and spare time. Out of 42 female informants, 10 claimed to learn in school, 22 in their spare time and 10 both in school and spare time. The questionnaires show that 26 out of 36 males stated that they had high motivation and 8 quite high motivation. Two had some motivation. Further, 10 out of 14 males with grades A and B reported high motivation and 15 out of 18 females with grades A and B had high motivation. A majority of the students with grades D and E also reported high motivation (13 of 17 students), so motivation is not always a factor for success in acquiring the L2 and achieving higher grades. Since I have not investigated aptitude in this group of students and in this study, I cannot answer to which students achieve higher grades because of aptitude. When no other explanation is found like extensive online gaming, extensive EE activities of other types (passive and active), early contact with English, high motivation or living in an English speaking country, aptitude seems to be one reasonable explanation, often in combination with one or maybe two other variables that are factors for success in reaching higher language proficiency. The students’ number of books in the home was not connected to how much they read in English, and in general, the

students did not seem to read much at all, with the exception of a few students.

4.1.3 Gender and grades.

Out of 36 male students, 7 achieved the latest grade A, 7 achieved the grade B, 2 achieved grade B-C (they were not sure) and 13 achieved the grade C. Only 2 of the males had the grade D and 4 the grade E. One male was an exchange student and had not received a grade in English yet.

15

No male student had the “grade” F (fail). Out of the females 12 achieved an A, 7 a B, 1 a B-C, 10 achieved C, 3 had D and 8 females had an E. One student reported not having a grade yet because she was an exchange student. No female had an F. To conclude my findings: the grades are quite even between genders, suggesting that the males have caught up with the females’ earlier higher achievements, if all grades from A to C are considered (males approximately 82.8 % and the females around 72.9 %). Approximately 40 % of the males received the grade A or B and around 46.2 % of the females. See figure 2.

Figure 2. Gender and grades

4.1.4 Male online gamers and grades.

Out of the 23 male gamers playing 4-8 hours a week or more, 9 individuals had achieved the grade A or B, and out of the 13 male low frequent/non-gamers (0-4 hours a week), 5 had achieved the grade A or B. See Figure 3.

The higher grades of the male students who game less frequently can easily be explained in this case. One of them had spent 14.5 years in two different English-speaking countries, knew English since he was born and used to be a gamer playing regularly for 6-8 years. The second male spent four months in an English-speaking country, came in contact with English at the age

0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 A B B-C C D E stu d en ts in % grades males females

16

of five, considered himself a non-gamer now but used to play regularly for 4-6 years. He also had high motivation and claimed to use English every day. The third male (grade B) used to game MMORPGs on a regular basis for 6-8 years, had high motivation and claimed to love English and wanted to work in an English-speaking country in the future. The fourth male also used to play online games regularly for 4-6 years (grade B) and started doing so at an early age. He claimed to have high motivation. So even if the male students claim to be gaming 0-4 hours a week now or say they don´t play anymore, they used to play MMOs or FPS online regularly for several years, often starting at an early age. The only real non-gamer among the males achieved the grade E. This male came in contact with English late at the age of 13 and hardly never used English in his spare time. Even if he claimed having high motivation, my assumption is that he probably does not have enough contact with the target language English.

Figure 3. Male online gamers and grades

Since most of the gamers seemed to have achieved higher grades, it was important to investigate the gamers playing 6-8 hours a week or more that achieved lower grades, to see if a reason can be found for their lower grade. Of these 15 gamers, 2 received the grade D. These two individuals are similar to each other in many respects. They both started gaming late, between the ages of 11-14 years. They played regularly between 0-4 years, which is not that long. One of these informants came in contact with English for the first time at the age of 12, and started

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 A B B-C C D E n u m b er o f male s tu d en t game rs grades 6-8 h/w or more 4-6 h/w 0-4 h/w non-gamers

17

taking it as a subject in school at the age of 14 years, which can explain why he has not achieved higher grades. These two individuals both claim to have high motivation. Summing up, frequency of gaming, longer amount of years spent playing regularly and debut of online gaming at an early age seems to affect the grade for the male gamers. Only one gamer had the grade E and none the grade F.

4.1.5 Females, grades and language acquisition.

The only gamer of the females that reported playing (Fortnite) regularly 6-8 hours a week, for 6-8 years, received the grade C. Her first contact with English was at the age of 11 which seems relatively late in Swedish terms speaking (English as a subject is usually introduced already in grade 1 for seven-year-olds in Swedish schools according to the curriculum for the English subject 2011). The female that “used to play” achieved grade B and used to play WoW. The female gamer (4-6 hours a week) played many MMOs regularly and had done so for 6-8 years. She had early contact with the English language and spent a large number of hours on other EE activities as well. She achieved grade A. Out of the 6 females that reported playing 0-2 hours a week (some type of MMORPG or at least multiplayer online games of FPS-type), 2 females achieved grade A, 2 grade B, one grade C and one grade E. Only 2 of 6 females in this group spent more than 6-8 hours a week or more on EE activities, which seems to suggest that the females EE activities are lower in frequency than the male students in general. The same goes for the entire group of the females EE activities - (42 students) achieving various grades. In general, the whole group of females reported lower amounts of EE than the males. Accounted is 18 out of 36 males who claimed that they used English in their spare time, conducting various EE or playing online games 6-8 hours a week or more. In the entire group of females, only 11 of 42 females reported engaging in EE activities 6-8 hours a week and none of them reported more.

Out of the entire group of females gaming 0-2 hours a week (13 in total), 6 achieved the grade A. These females’ EE seemed to mostly consist of social media, watching TV/movies and listening to music. Most of them had first contact with English at an early age. The females with the higher grades must have an explanation for how they learn English found elsewhere. Out of 12 females, 6 with notably few hours of EE activities and the grade A, their high grade would have to be explained being due to other reasons than EE. One female had lived in England for three months and had an English father. She had known English her whole life. Another female had early contact with English and high motivation. The third female used to be a CLIL-student and had high motivation. The fourth female spent a summer in England, had

18

high motivation and wanted to live abroad in the future. The fifth female has no other explanation for her high grade than high motivation, early contact and I am guessing – maybe aptitude for the subject. The last student in this group (number six) high grade, has the only possible explanations being the same as student number five in this group – maybe aptitude matters here. The females’ higher grades did not seem to be connected to EE activities as clearly as the males’ higher grades seemed to.

4.1.6 Gamers, non-gamers and grades.

Since frequency of gaming and years spent on regularly playing seem to have an effect on the students’ grades, therefore all gamers (even those who used to play) that play/played MMOs 4-8 hours a week or more (both genders), are compared to the rest of the group (0-4 hours of gaming – non-gamers), to see if the gamers tend to have higher grades. Calculations show that gamers of both genders, playing 4-8 hours a week or more (on a regular basis some part of their life), 92 % achieved the grade C or higher, while in the group “non-gamers”, 70.6 % achieved the grade C or higher. That is a 21.4 % difference. See Figure 4.

Figure 4. Gamers, non-gamers and grades

4.1.7 Summary of the findings.

The grades received by different genders in the informant group can be interpreted as relatively similar if one considers the grades A, B, B-C and C. More females than males had achieved grade A and more females than males had the lower grade E. The most common grades for the

0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45 A B B-C C D E stu d en ts in % grades 4-8 h/w or more 0-4 h/w

19

males were A, B, B-C or C. The higher grades of the male students could be connected to extensive online gaming (gamers playing 4-8 hours or more) in combination of many hours spent on other EE activities, especially Youtube. The females did not engage in EE activities to the same extent as the males and the females’ higher grades could not be connected to online gaming or other EE activities. The females were mostly non-gamers, while the males were mostly gamers to varying extents. The female’s mostly used EE activities were social media, music and TV/movies.

Females tended to more often learn English in school and males more in their spare time. Almost all students reported high motivation or pretty high motivation and it was not always correlated to a higher grade, because even D and E students claimed to have high motivation.

Some common reasons for lower grades in English for these informants seemed to be late first contact with English, low number of hours conducting EE activities (including gaming) and late start in learning English at school (after the age of 11 or later). Reasons for higher grades (A, B, B-C) could be connected to online gaming at least 4 hours a week (mostly the males benefited from this since the females were mostly non-gamers), preferably since an early age on a regular basis for at least 4-6 years, extensive EE other than gaming, having lived in an English speaking country, being a former CLIL-student, high motivation in some cases or maybe aptitude in students, where no other explanations could be found.

5. Discussion

Firstly, the questionnaire revealed that the males were mostly gamers and most of the females non-gamers. If the questionnaire is compared to earlier researchers’ findings, (e.g. Puimège & Peters, 2019, p. 945; Sundqvist, 2009, p. 131), results show the same indications. Media statistics in Sweden (Statens medieråd, 2019) also revealed that it was mostly the boys that played interactive MMOs like Fortnite (the MMO type games being the relevant type in a learning context), while girls, to some extent, mostly played offline single-player games like

The Sims (Statens medieråd, 2019, p. 44). The teacher, Mr Andersson, too, seemed to believe

that females are not gamers, stating that he believed the female students were more engaged in social media instead. He estimated that probably 80-90 % of the male students play online games. Mr Andersson expresses: “I don´t believe that the girls play interactive online games. They do other things on the Internet and do not communicate through online games like the boys do”. All sources are therefore in agreement that girls very seldom play MMOs. The girls

20

also seem to prefer using Swedish to a higher degree in their spare time activities (Sundqvist & Sylvén, 2014, p. 3). The MMO games are also mostly played by boys, as has been accounted for by statistics on Swedish Youth’s media habits (Statens medieråd, 2019). The MMO environment can therefore be said to mostly be useful to the boys as an environment where one can learn English (Sundqvist & Sylvén, 2014, p. 3; Sylvén & Sundqvist, 2012a, pp. 311-313). Girls seem to learn English elsewhere.

The questionnaire in this study revealed that the males played more hours of online games and also spent more time on other EE activities than the females, especially watching Youtube videoclips on the Internet. According to Statens medieråd, boys also reported playing considerably higher amounts of hours on a regular basis (Statens medieråd, 2019, p. 10). The questionnaire and largescale Swedish statistical data seem to be in agreement here as well. The males had a tendency to more often state that they learned English outside of school in this study, while the females more often stated learning in school. Furthermore, the findings in the questionnaire also seemed to indicate that frequency of online gaming, online gaming starting at an early age and how many years a person had been playing regularly, seemed to be of vital importance, if it was to have an impact on the students’ grades. Earlier research had found the same indications (Sylvén & Sundqvist, 2012a, pp. 311-313).

Secondly, the effectiveness of the MMOs learning environment is well founded in previously published research (e.g. Horowitz, 2019; Olsson, 2016; Sykes, 2018; Sylvén & Sundqvist, 2012). The MMO gaming environment has been found to offer several elements that are considered to be effective learning tools in SLA theory. Elements found in MMOs are interaction with many players all over the world, massive exposure to authentic English in a natural speaking environment, collaboration, problem-solving, immersiveness and impact on affective filters (e.g. Horowitz, 2019, pp. 385-388; Sykes, 2018, p. 220; Sylvén & Sundqvist, 2012a, pp. 304-305). Offline single-player games do not have the same elements. The questionnaire of this study reveal that the gamers (4-8 hours a week or more) achieved higher grades than the rest of the group, which might be an indication that these students have reached higher language proficiency. To have proven this, I would have needed to carry out English language proficiency tests, testing the students’ proficiency in areas like vocabulary or oral proficiency. Unfortunately, there was not enough time or space to include such data in this study. Never the less, these findings have made me believe that MMO type games might be effective learning environments for EFL students as well as the fact that MMO type games are interactive and gamers play with team-mates from across the globe communicating in English

21

– the common lingua franca. The type of game played is relevant to its’ effectiveness on EFL learning (Sylvén & Sundqvist, 2012a, pp. 304-305, 311-313). Mr Andersson had noticed that the students that are very active online, most often are very advanced in their English proficiency, but that these are just a small share of all students. This specific group is known by Mr Andersson to play online games or belong to different communities (he calls them subcultures), and according to Mr Andersson, these students chat frequently in English online. Finally, the informants’ grades seemed to be quite even between genders among the informants, showing that, at least in this study, the males had caught up with females earlier higher grades in the subject English (Skolverket, Sveriges officiella statistik, 2018/19). Looking at the online gamers (the ones who played 4-8 hours a week or more, both genders) and comparing them to the rest of the group, gamers were found, in the questionnaire, to have achieved higher grades than the rest of the group and non-gamers. In the gamers (referring to results in Figure 4) group, 92 % achieved the grade C or higher, while the “non-gamers” that achieved grade C or higher landed on 70.6 % - a 21.4 % difference. There seems to be a magic hour of frequency that indicates impact on the students’ grades: gaming at least 4 hours a week. Obviously, other factors such as other EE activities, early contact with English or aptitude affected this study’s results, and I am therefore not claiming that online gaming of the MMO type is the sole reason for higher grades in the subject English.

Researchers like Sundqvist & Sylvén, 2014; Olsson, 2016; Sykes, 2018; Horowitz, 2019; Puimège & Peters, 2019, found that online gaming had a positive effect on English vocabulary acquisition, communication skills, oral proficiency and affective filters because the activity occurs in the childrens’ and adolescents’ spare time and is optional and chosen, offers massive exposure and opportunity to practice the target language and contained effective elements for learning English, with its base found in SLA theory. Mr Andersson is in agreement that: “You need to do something at home too in English to reach the higher grades. Two classes a week in school does not cut it.” As Horowitz (2019) argued, lack of practicing the target language, and lack of authentic speaking environments, can potentially reduce WTC and increase FLA (Horowitz, 2019, p. 383). Sundqvist & Sylvén (2014) state that: “Phrased differently, youths who spent a great deal of time on EE activities reported feeling less anxious about speaking English than those who spent less time on such activities. Interestingly reduced anxiety levels were particularly salient among digital gamers” (p. 6).

22

6. Conclusion

This study investigated the participating students’ online gaming habits to see if the gamers achieved higher grades in the subject of English. The aim was also to find out if there were differences in the female students’ gaming habits and how the females learned English compared to the males in this group of informants.

I can conclude that the gamers in this study are mostly males, the informants’ grades are in general even between gender (except for the fact that more females than males achieved grades A and E), and that gaming online, 4-8 hours a week or more seemed to affect the students’ grades. The fact that the gamers playing 4-8 hours a week or more had achieved higher grades might be an indication that these particular students had reached higher language proficiency. However, since I did not conduct any proficiency tests, it would be necessary to investigate this further.

Since there seems to be gender segregation in the gaming world, further research on developing effective, interactive instructional (or commercial) online games for EFL students and youth, which appeal to both girls and boys, would be of vital importance to further develop the subject of English, both in and outside of school. The school environment needs to keep up with society and use tools that are up-to-date. There also seems to be a lack of a common categorization method for online games in research on the subject, so creating such a common method would be beneficial for future researchers.

23

List of references

Blizzard (manufacturer of World of Warcraft). Retrieved 5 March 2020, from

https://warcraft.blizzplanet.com

Butler, Y. G., Someya, Y., & Fukuhara, E. (2014) Online games for young learners’ foreign language learning. ELT Journal, 68 (3), 265-275. https://academic.oup.com/eltj/article-abstract/68/3/265/454300

Denscombe, M. (1998) Forskningshandboken. Lund: Studentlitteratur Epic Games (manufacturer of Fortnite 2017). Retrieved 5 March 2020, from

https://www.epicgames.com/fortnite

Frost, M. (2015) Detta är sista gången vi får veta hur många som spelar World of Warcraft. FZ (formerly named Frag Zone). Retrieved 5 March 2020, from

https://www.fz.se/nyhet/224215-detta-ar -sista-gangen-vi-far-veta-hur-manga-som-spelar-world-of-warcraft

Horowitz, K. S. (2019) Video Games and English as a Second Language: The Effect of Massive Multiplayer Online Video Games on The Willingness to Communicate and Communicative Anxiety of College Students in Puerto Rico. American Journal of Play, 11 (3), 379-410. https://www.journalofplay.org/sites/files/pdf-articles/11-3-Article%204.pdf Hou, H.-T. (2011) Learning English with Online Game: A Preliminary Analysis of the Status of Learners’Learning, Playing and Interaction. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 6872, 191-194. https://link-springer-com.ep.bib.mdh.se/content/pdf/10.1007%2F978-3-642-23456-9_35.pdf

Hung, H.-T., Yang, J. C., Hwang, G.-J., Chu, H.-C., & Wang, C.-C. (2018) A scoping review of research on digital game-based language learning. Computers and Education, 126, 89-104.

https://doi-org/10.1016/j.compendu.2018.07.001

Lightbown, P., & Spada, N. M. (1999) How Languages are Learned. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Löfving-Johansson, L. (2013) The games improved my English skills – playing video and

computer games in relation to Swedish pupils’ English vocabulary. (Unpublished degree

24

Museum of Play (2020) History of online games and game consols. Retrieved 5 March 2020, from https://museumofplay.org/about/icheg

Myrén, J. (2020) Antalet World of Warcraft-spelare har mer än fördubblats. FZ. Retrieved 5 March 2020, from https://fz.se/nyhet/282230-antalet-world-of-warcraft-spelare-har-mer-an-fordubblats

Onlinespel/Dataspelshistoria/The Sims/Fortnite/World of Warcraft/online games categories.

Retrieved 12 December 2019, from https://sv.wikipedia.org/wiki/Onlinespel

Olsson, E. (2016) On the impact of extramural English and CLIL on productive vocabulary. Gothenburg: Göteborgs Universitet.

Perry, Jr., F. L. (2005) Research in applied linguistics: becoming a discerning consumer. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, publishers.

Playstation. (1994-2020) History of Playstation. Retrieved 25 February 2020, from

https://www.playstation.com/sv-se/explore/ps4/playstation-through-the-years/

Puimège, E., & Peters, E. (2019) Learners’ English Vocabulary Knowledge Prior to Formal Instruction: The Role of Learner-Related and Word-Related Variables. Language Learning, 69 (4), 943-977. (Language Learning Research Club: University of Michigan).

https://onlinelibrary-wiley-com.ep.bib.mdh.se/doi/full/10.1111/lang.12364

Ray, M. (2012) Online gaming. Electronic Games. Retrieved 25 February 2020, from

https://www.britannica.com/technology/online-gaming

Skolverket. (2011-2018) Läroplan, kursplan I Engelska årskurs 1-3. Stockholm: Skolverket. Retrieved 16 June 2020, from www.skolverket.se

Skolverket. (2011-2018) Läroplan, ämnesplaner I gymnasieskolan på engelska. Stockholm: Skolverket. Retrieved 15 June 2020, from www.skolverket.se

Skolverket. (1996/97, 2018/19) Sveriges officiella statistik. Retrieved 3 February 2020, from

https://skolverket.se/skolutveckling/statistik/sök-statistik-om-förskola-skola-och-vuxenutbildning

SOU Delbetänkande av DEJA – Delegationen för jämställdhet I skolan 2009: Flickor och

pojkar I skolan – hur jämställt är det?. Stockholm: Edita Sverige AB.

25

Statens medieråd. (2019) Ungar och medier 2019. Retrieved 23 February 2020, from

www.statensmedierad.se

Sundqvist, P. (2009). Extramural English Matters – Out-of-School English and Its Impact on

Swedish Ninth Graders’ Proficiency and Vocabulary [Doctoral dissertation, Karlstad

University, Publication No. 2009:55]. Universitetstryckeriet.

Sundqvist, P. (2015) About a boy: A gamer and L2 English speaker coming into being by use of self-access. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 6 (4), 352-364.

http://sisaljournal.org/archives/dec15/sundqvist

Sundqvist, P., & Sylvén, L. K. (2014) Language-related computer use: Focus on young L2 English learners in Sweden. ReCALL, 26 (1), 3-20.

Sykes, J.M. (2018) Digital Games and Language Teaching and Learning. Foreign Language

Annals, 51, 219-224. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12325

Sylvén, L. K., & Sundqvist, P. (2012a) Gaming as extramural English L2 learning and L2

proficiency among young learners. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sylvén, L. K., & Sundqvist, P. (2012b) Similarities between playing World of Warcraft and CLIL. Apples – Journal of Applied Language Studies. 6 (2), 113-130.

Tornberg, U. (2005) Språkdidaktik. Kristianstad: Kristianstads Boktryckeri AB. Vetenskapsrådet (2017) God forskningssed. https://www.vr.se/analys/rapporter/vara-rapporter/2017-08-29-god-forskningssed.html

Waring, H. Z. (2018) Teaching L2 interactional competence: problems and possibilities.

Classroom Discourse, 9 (1), 57-67. https://doi.org./10.1080/19463014.2018.1434082

World of Warcraft (game site). Retrieved 5 March 2020, from https://worldofwarcraft.com Yang, J. C., & Quadir, B. (2018) Effects of Prior Knowledge on Learning Performance and Anxiety in an English Learning Online Role-Playing Game. Educational Technology &

26

Appendix 1

Questionnaire English

Circle answers or write your response, as required!

1. I am in English course: 5 6 7

2. I am:

Male Female Other

3. My first language is ___________________________________________________________

4. My second language is ________________________________________________________

5. I have a third language, namely _________________________________________________

6. The language I use most frequently is ____________________________________________

7. The language I know best is ____________________________________________________

8. Have you lived in English speaking countries where English is the language used, for more than three months?

yes no Country or countries ________________________________________

9. How long did you live there? ___________________________________________________

10. At what age did you first come in contact with English? ______________________________

27 __________________________________________________________________________________

12. How old were you when you first started learning English in school? ___________________

__________________________________________________________________________________

13. What is your latest grade in English? _____________________________________________

14. Do you have access to a computer with an Internet connection in your home? ___________

15. How many books do you have in your home?

0-10 books 11-30 books 31-60 books more than 60 books

16. Do you read longer texts in your spare time? (several options possible)

no books magazines blogs other sources namely ____________________________

17. In what languages do you read in your spare time? (several options possible)

I don´t read in Swedish in English in another language namely___________________

18. How many hours a week do you read in English in your spare time?

0-2 hours/week 2-4 hours/week 4-6 hours/week 6-8 hours/week more ______

19. Do you use YouTube in English?

0-2 hours/week 2-4 hours/week 4-6 hours/week 6-8 hours/week more ______

20. Do you use social media? (several options possible)

28 21. If you use social media, how often do you use English in connection with those?

0-2 hours/week 2-4 hours/week 4-6 hours/week 6-8 hours/week more ________

22. Do you watch TV or movies in English?

0-2 hours/week 2-4 hours/week 4-6 hours/week 6-8 hours/week more ________

23. Do you listen to music in English?

0-2 hours/week 2-4 hours/week 4-6 hours/week 6-8 hours/week more ________

24. Do you play online computer or video games?

0-2 hours/week 2-4 hours/week 4-6 hours/week 6-8 hours/week more ________

25. How old were you when you started playing online computer or video games?

I have never played 2-4 years 5-7 years 8-10 years 11-14 years older _______________

26. For how many years in total do you think you have played online games on a weekly basis? 0-2 years 2-4 years 4-6 years 6-8 years more __________________________

27. What games do you play? (Several options possible)

I don´t play Sims WoW Counterstrike Minecraft Fortnite Overwatch

Assassin´s Creed Rainbow Six Siege Call of Duty Other games, namely: ________________ __________________________________________________________________________________

28. Do you play online games in English?

29 29. How often do you use English in your spare time? (speaking, listening, reading or writing) 0-2 hours/week 2-4 hours/week 4-6 hours/week 6-8 hours/week more _______

30. Where do you think you learn the most English? In school in my spare time

31. How important is it for you to learn and know English?

not important somewhat important pretty important very important

32. Why? ______________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________ Thank you for participating!

30

Appendix 2

Interview questions for teacher

How long have you worked as an English teacher?

What methods do you use now/what approach?

What methods have you found being most effective for second language teaching?

Have your methods changed over the years?

Have there been any changes with regard to the students´ language skills over the years?

What students achieve the highest grades and why do you think?

Are there any gender differences compared to when you started working as a teacher?

What are the students interested in?

Do a lot of your English students play online games?

In your experience, do you think girls play online games?