The absolution of

non-audit services

– unravelling a nexus of

research

MASTER THESIS WITHIN:

Business Administration - Accounting

NUMBER OF CREDITS: 30 ECTS PROGRAM OF STUDY: Civilekonom AUTHOR: Oliver Fransson & Simon Sleman JÖNKÖPING May, 2020

A quantitative study of non-audit services’ impact on

financial reporting quality among private firms in

Sweden.

“Knowledge is like a garden; if it is not cultivated, it cannot be harvested.” - Unknown

i

Master Thesis in Business Administration

Title:

The absolution of non-audit services – unravelling a nexus of research: A quantitative study of non-audit services’ impact on financial reporting quality among private firms in Sweden.

Authors:

Oliver Fransson and Simon Sleman

Tutor: Timur Uman

Examiner:

Emilia Florin Samuelsson

Abstract

Non-audit services provided by audit firms have been a popular scientific topic within the fields of audit and accounting research over the past decades. Numerous researchers have attempted to provide a theoretical contribution by examining different ways of measuring the concepts of audit quality and financial reporting quality. The resulting consequences are mixed results and a lack of consensus among researchers from both research fields. The two, in other situations, rather distinctive research fields of audit quality and financial reporting quality, have, in several cases, been confounded without analytical reflection regarding their differences. In parallel to the scientific progress, regulatory bodies have noticed the increasing trend of non-audit services and how they constitute larger portions of the audit firm’s annual revenues. Their responses have been legal restrictions, both in the US and Europe, in order to cease the trend.

The purpose of this thesis is to make a pronounced investigation regarding the relationship between non-audit services and financial reporting quality in Swedish private firms. Furthermore, it will also be of interest to examine if this proposed relationship is moderated by the presence of the four global market-leading audit firms or not.

ii

The study is based on a deductive approach and a quantitative research strategy, to collect and analyze data from annual reports. To fulfill the purpose of the study, the data is analyzed by conducting binary and multinomial logistic regression tests.

The results suggest that there is an association between certain types of non-audit services and financial reporting quality. Specifically, services that are unrelated to tax have proven to be statistically significant positively correlated with financial reporting quality. No evidence was found supporting a moderating effect by the characteristics of audit firms, suggesting that the choice of an audit firm is irrelevant for attaining high financial reporting quality when purchasing non-audit services.

The study’s theoretical contribution is the novelty arising from the combination of studying non-audit services’ impact on financial reporting quality within a Swedish setting on private firms. The study also provides empirical contribution by using a proxy for financial reporting quality rarely used in previous research. The findings are of practical importance since they suggest that firms potentially benefit in their financial reporting by purchasing these kinds of services, which contradicts past actions made by regulatory bodies.

Key terms:

Non-audit services, financial reporting quality, qualified auditor report, big four audit firms, knowledge spillover effect, economic dependency and auditor independence

iii

Acknowledgment

We want to devote gratitude towards each other, our families, and Jönköping International Business School for making this project a reality. Special thanks should also be directed towards the university for these four years of valuable education.

At the time this thesis was written, the global pandemic of Covid-19 ravaged the world. Many functions of the society were harshly affected, and entire nations went into lockdown. As a consequence, almost the entirety of this thesis has been forged in the digital space. The writing process, meetings with the tutor, seminars, and data collection have all been performed digitally – which shows the strength and opportunities the digital tools provide the society in times of crisis.

Lastly, we want to thank our tutor Timur Uman for his assistance throughout the semester. He has been a great resource, where he has assisted us in generating ideas, providing rich feedback, and continually challenging us to do better. We also want to thank other teachers at the university, which have helped us throughout different stages of the project.

This thesis marks the end of an era for both of us. We are now embracing the opportunities of the future with valuable knowledge at our disposal. It is important to remember that knowledge is like a garden;if its not cultivated, it cannot be harvested…

Jönköping, 18th of May

iv

1

Introduction ... 1

1.1 Background ... 1

1.1.1 An invitation to the world of non-audit services and quality in all its forms and shapes. ... 1

1.1.2 The idea of a threat to auditor independence ... 2

1.1.3 The research’s impact on the development of regulations on international and national levels ... 3

1.1.4 The accidental research of a forgotten concept (within the given research field) ... 4

1.2 Problem Formulation ... 4

1.2.1 Putting financial reporting quality in the spotlight ... 4

1.2.2 Earlier research within financial reporting quality ... 4

1.2.3 Researching financial reporting quality in a Swedish Setting ... 5

1.2.4 How non-audit services are related to financial reporting quality ... 7

1.3 Purpose of Study ... 8

1.4 Research Question ... 8

2

Literature Review ... 9

2.1 What is Financial Reporting Quality? ... 9

2.1.1 According to prior research ... 9

2.1.2 According to IASB / FASB ... 11

2.1.3 According to Swedish legislation ... 11

2.2 What Determines the Level of Financial Reporting Quality? ... 12

2.2.1 Individual-level determinants. ... 12

2.2.2 Firm-level determinants ... 13

2.2.3 Institutional level determinants ... 13

2.3 Non-Audit Services ... 15

2.3.1 The current trends of non-audit services in relation to revenue for three of the big four audit firms ... 15

2.3.2 Non-audit services as a predictor of audit quality and auditor independence in the majority of previous research ... 15

2.3.3 Non-audit services as a predictor of other concepts ... 16

2.3.4 Why do audit clients purchase non-audit services? ... 16

2.4 Prior Research Regarding the Relationship Between Financial Reporting Quality and Non-Audit Services ... 17

2.5 Audit Quality’s Relation to Financial Reporting Quality ... 18

v

3

Constitutionalia ... 24

3.1 The K-series Regulatory Framework ... 24

3.2 Retriever / CreditSafe ... 24

3.3 The Swedish Inspectorate of Auditors ... 24

4

Methodology and Empirical Method ... 26

4.1 Research methodology ... 26

4.1.1 A philosophical view of science ... 26

4.1.2 Scientific reasoning ... 26

4.1.3 Research strategy ... 28

4.2 Empirical research design and method ... 29

4.2.1 Sample selection ... 32

4.2.2 Delimitations of the sample selection ... 32

4.2.3 Data collection ... 32

4.2.4 Dropouts in the sample ... 34

4.2.5 Data processing and matching of samples ... 34

4.2.6 Operationalization ... 36

4.3 Evaluation of the method ... 41

4.3.1 Reliability ... 41

4.3.2 Validity ... 41

4.3.3 Generalizability ... 42

4.3.4 Replication ... 43

4.4 Method for data analysis ... 44

5

Empirical Analysis ... 46

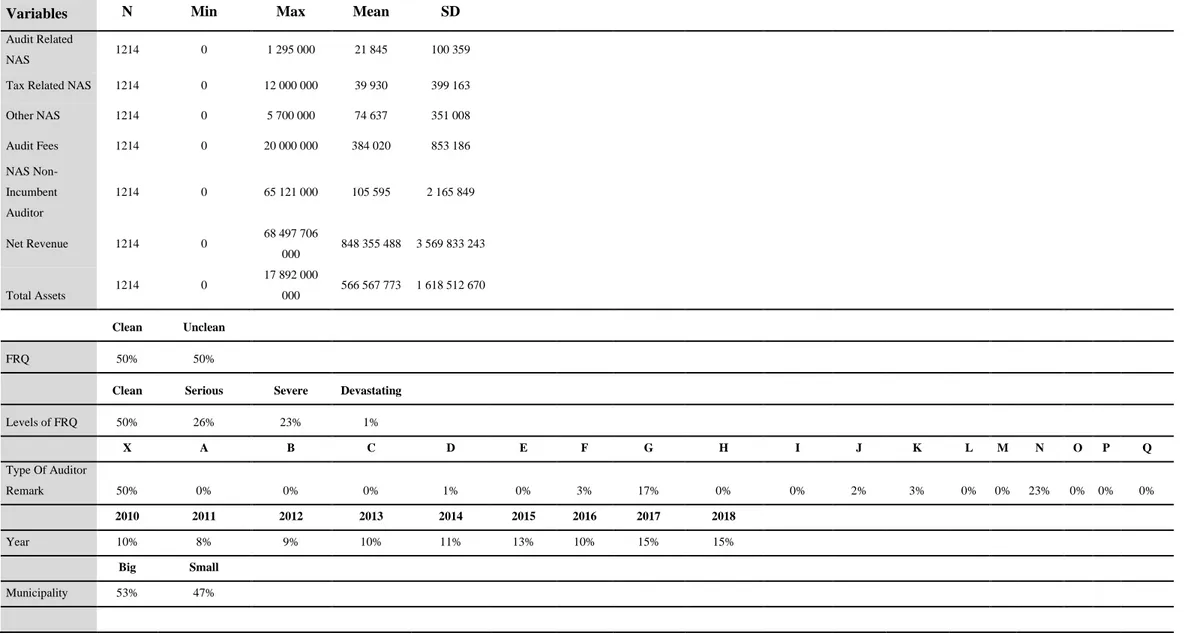

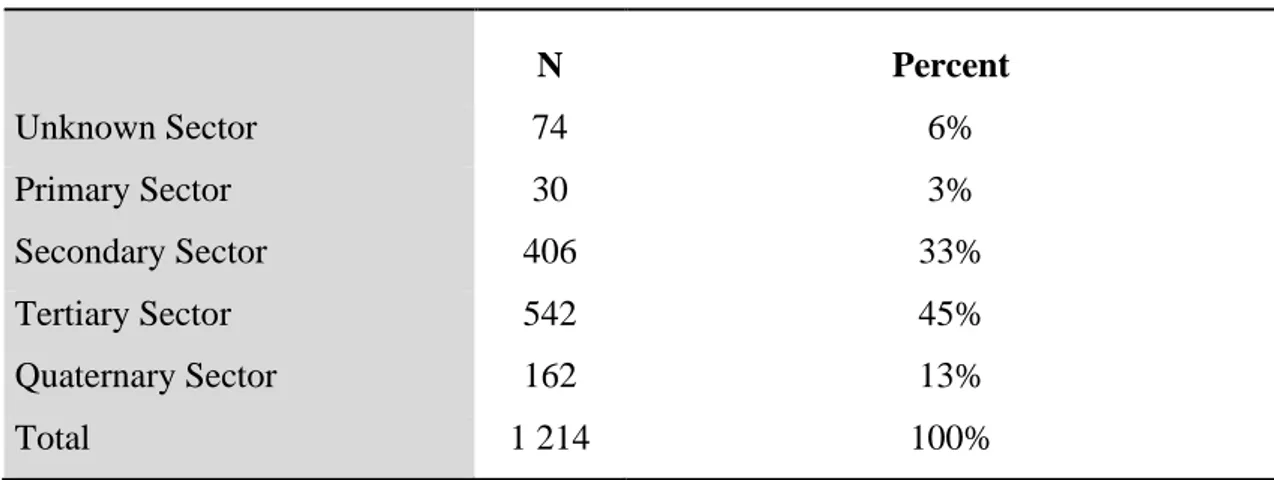

5.1 Descriptive statistics ... 46

5.2 Dependent variable ... 50

5.3 Correlation matrix ... 50

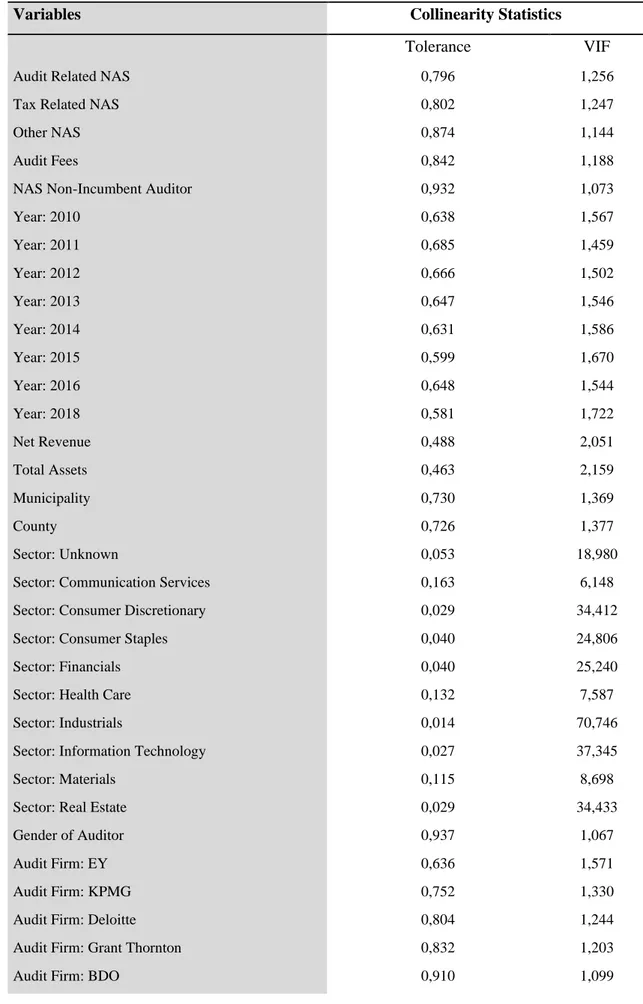

5.3.1 Controlling for multicollinearity ... 53

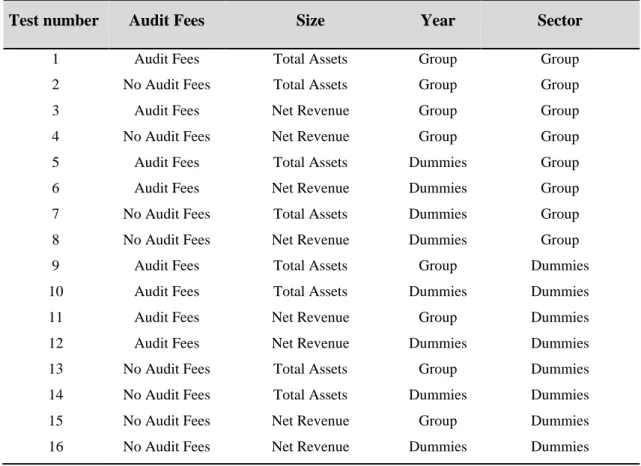

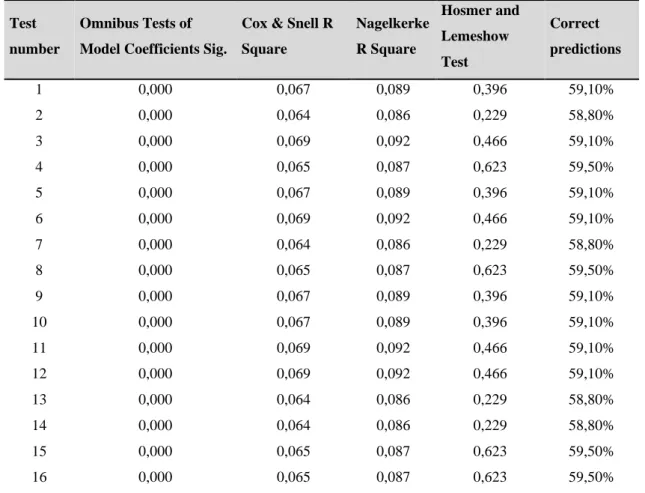

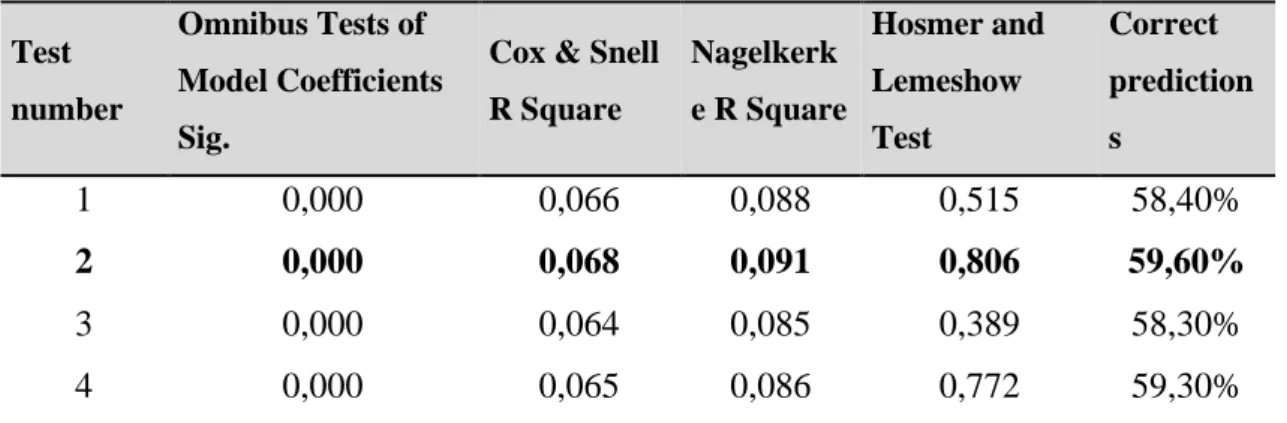

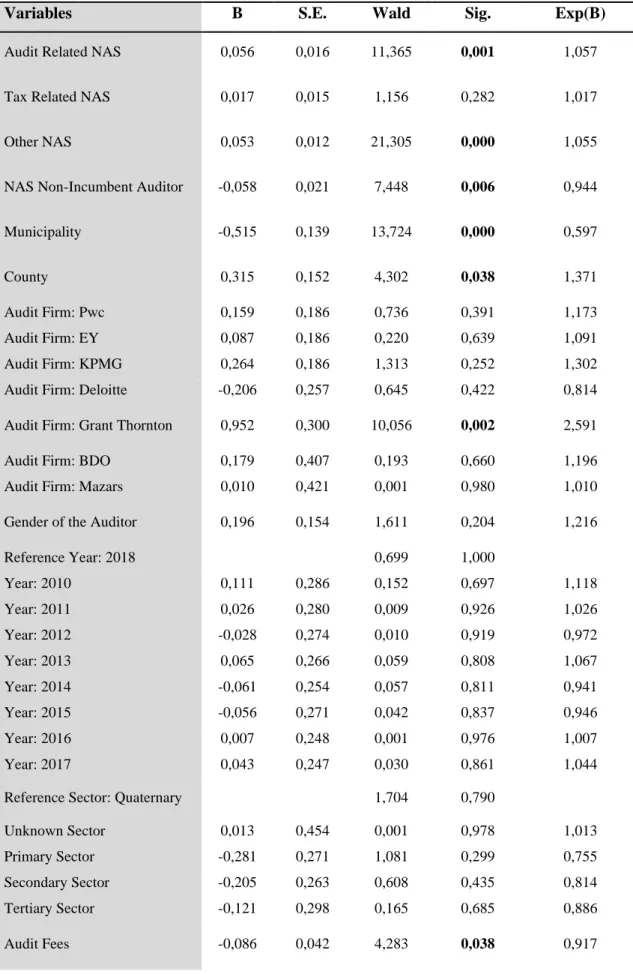

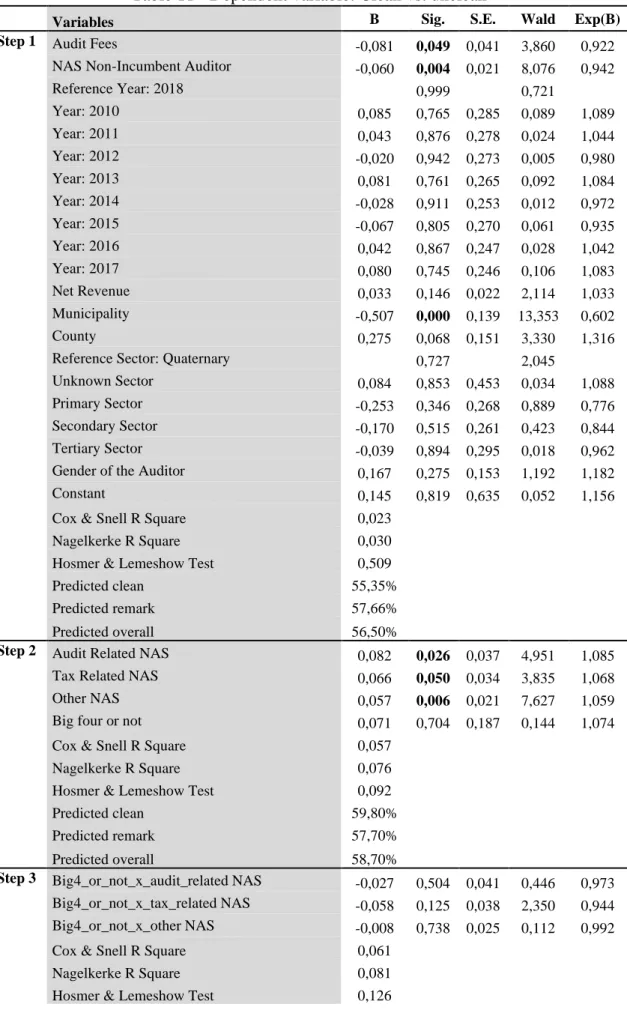

5.4 Regression Analysis – Clean vs. Unclean ... 57

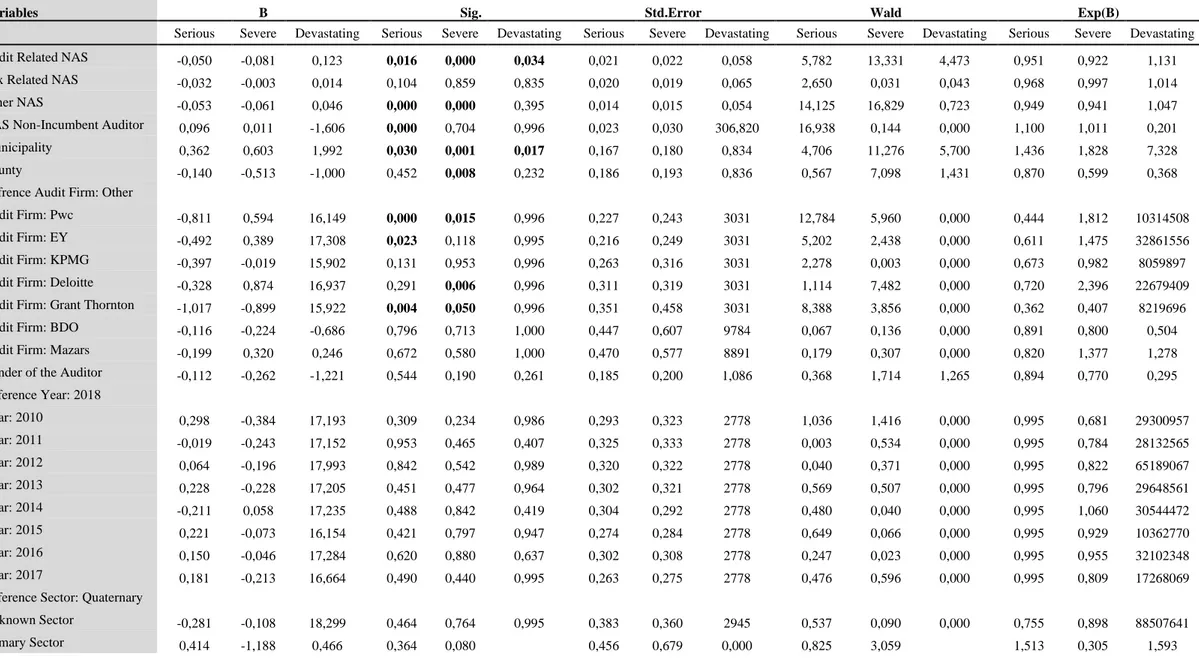

5.5 Regression Analysis – Clean vs. sublevels of low financial reporting quality ... 64

5.5.1 Serious ... 67

5.5.2 Severe ... 67

5.5.3 Devastating ... 68

5.6 Binary Logistic Regression test with big four audit firms as moderating variable ... 68

5.6.1 Clean vs. unclean ... 69

5.6.2 Serious ... 71

5.6.3 Severe ... 73

vi

5.7 Consequences for the hypotheses ... 75

6

Discussion ... 79

6.1 General discussion ... 79

6.2 Deviating findings regarding tax-related NAS ... 81

6.3 Discussion regarding the moderating effect by big four firms ... 83

6.4 Location as a significant control variable ... 85

7

Conclusions ... 86

7.1 Implications and criticism ... 86

7.2 Contribution of the study ... 87

7.3 Suggestions for future research ... 92

7.4 Ethical considerations ... 94

8

Reference List ... 96

9

Appendix ... 106

9.1 Tables ... 106 9.1.1 Table 14 ... 106 9.1.2 Table 15 ... 108 9.1.3 Table 16 ... 109 9.1.4 Table 17 ... 111 9.1.5 Table 18 ... 113 9.1.6 Table 19 ... 113 9.2 Figures ... 114 9.2.1 Figure 2 ... 114 9.2.2 Figure 3 ... 114 9.2.3 Figure 4 ... 115vii

Definitions

The following list grants the reader an overview of relevant laws and abbreviations that will be encountered throughout the text.

• ABL = Aktiebolagslag (2005:551) / Swedish Companies Act

• AQ = Audit Quality

• BFL = Bokföringslag (1999:1078) / Book-keeping Act

• BFN = Bokföringsnämnden / The Swedish Accounting Standards Board

• FRQ = Financial Reporting Quality

• NAS = Non-audit services

• Revisorslag (2001:883) / Public Accountants Act

• Revisionslag (1999:1079) / Auditing Act

• ÅRL = Årsredovisningslag (1995:1554) / Annual Accounts

The list bellow explains which audit firms that belong to the big seven in Sweden. Firms in bold belong to the big four.

• Price Waterhouse Coopers (Pwc) • EY • KPMG • Deloitte • Grant Thornton • BDO • Mazars

1

1 Introduction

The introduction provides the thesis’s background and problematization. The research purpose and question are subsequently introduced.

1.1 Background

1.1.1 An invitation to the world of non-audit services and quality in all its forms and shapes.

Non-audit services, financial reporting quality, and audit quality are three terms that have been flooding the academic world of accounting since the 1960s until today. In contrast, the two latter have been the subject of dependency influenced by the former. Non-audit services are, as the terminology suggests, services provided by an audit firm that are not related to the audit services; such as tax consultancy, advisory services, and corporate finance services. Each paper in the established literature has attempted to refine their studies from their peers, arguing for how their incremental improvement would shed new light on the subject. The paradoxical consequence of the massive library of research is that the outcome is still unclear; the determinants of audit quality and financial reporting quality are numerous, and there is low consensus on their respective effects. The endgame of the most papers has been to conclude the auditor’s position; has the auditor’s independence been compromised, and how? This thesis is aiming to shift the focus from audit quality in the analysis and examination, and instead target different non-audit services and how they affect the financial reporting quality in various ways. The main argument can be found in the various conclusions from previous papers investigating audit quality; they are having difficulties in making statements whether audit quality actually has been investigated or if there are other factors present (Craswell, 1999; Hay, Knechel, & Li, 2006; Wines, 1994). By shifting to financial reporting quality, we believe that more accurate examinations can be made, and it also creates an alternative approach to investigate the impact of non-audit services. Initially, a walkthrough of the history of non-audit services and auditor independence is required since this has been the seed that has grown to the immense jungle of research it is today.

2

1.1.2 The idea of a threat to auditor independence The idea that non-audit services (hereafter denoted as “NAS”) may pose a threat to the

independence of auditors can be traced back to the 1960s. One of the earliest papers made an experimental study on whether the joint provision of managerial services and audits could pose a potential threat to the appearance of audit independence. The surveys were, among others, handed out to people working within the profession of financial services, where a majority of the answers thought that the joint provision should be discouraged and restricted since they posed a threat to auditor independence (Briloff, 1966). Throughout the following decade, more research was conducted to find further evidence regarding the proposed threat to audit independence. One common denominator between the studies was the focus on stakeholders’ perception of audit independence, and the research methods used were dominated by experimental studies consisting of surveys and case studies (Hartley & Ross, 1972; Lavin, 1976; Pany & Reckers, 1984; Pany & Reckers, 1983; Titard, 1971).

Looking forward in time, new research regarding the joint provision of managerial services and auditing reached the surface in the 1980s until the beginning of the 21st century. The notion of “auditor independence” decreased in frequency and was replaced with the terminology of “audit quality.” The conceptual idea behind this new terminology was initialized in a well-known paper by DeAngelo from 1981. Audit quality was defined as a concept consisting of two dimensions; 1) whether the auditor manages to find material errors and mistakes, and 2) whether the auditor, once identified the error, chooses to report this (Deangelo, 1981). Approximations of audit quality took new directions compared to earlier research, and now the focus had transitioned from the stakeholders’ perceptions of auditor independence to actual audit quality. The research design went from collecting ideas and opinions to archival methods; collecting outputs of the auditing process. Two major approximations made its appearance in several research papers; earnings management (consisting of meeting financial benchmark targets and measuring the magnitude of discretionary accruals) and the auditor opinion regarding the financial statements (Ashbaugh, LaFond, & Mayhew, 2003; Callaghan, Parkash, & Singhal, 2009; Frankel, Johnson, & Nelson, 2002; M. A. Geiger & Rama, 2003; Wines, 1994).

3

These two fundamental ways of measuring audit quality and auditor independence; in fact, and appearance, continued to be of interest until today. Non-audit services managed to stay relevant as an independent force affecting the outcome of the audit. Recent papers have tried to make fine adjustments on these well-established foundations, such as changing the environment to low litigation environments such as Norway and Sweden, and only checking for private firms (Hope & Langli, 2010; Svanström, 2013). In both cases, there is no evidence that NAS impairs auditor independence. Another paper attempts to separate companies from low performing and high performing and finds that firms of low performance indicate a negative association between NAS and auditor independence (Kang, Hwang, & Hur, 2019). Apart from the continuation of old praxis, there has also been a rise in papers that attempt to collect and review the vast amount of previous research (Habib, 2012; Schneider, Church, & Ely, 2006; Tepalagul & Lin, 2015).

1.1.3 The research’s impact on the development of regulations on international and national levels

In parallel to the vast quantity of research conducted in the area of NAS’s relationship with audit independence, regulatory bodies carefully monitored the development of NAS, and several actions have been made throughout the last decades. Partly because of origin of the most research papers, the Sarbanes Oxley Act covered the introduction in several papers from the period of 2003-2004 (Ashbaugh et al., 2003; Chung & Kallapur, 2003; Frankel et al., 2002; Krishnan, Su, & Zhang, 2011; Reynolds, Deis, & Francis, 2004). The act prohibited the joint provision of certain NAS and audit services, being the ignition of an era of monitoring and regulation of the business model. Years later, the other side of the Atlantic Ocean turned their attention to the matter.

In 2014, there was a regulatory audit reform in the EU, which brought several changes. One of these changes was the introduction of the so-called “Blacklist,” which prevents the joint provision of certain non-audit services and audit services to audit clients, which are classified as “Public Interest Entities” (PIE’s) (European Commission, 2014). Those entities that are classified as PIE’s, according to European Union Law, are publicly traded companies that are traded on an exchange governed by an EU member state, credit institutions, and insurance undertakings. A respective member state can also determine whether an entity shall be regarded as a PIE or not (Regulation, No537/2014).

4

Up until this point (2014), there was no restriction regarding this joint provision of NAS and audit services in the EU (Green Paper, 2010). There was also an introduction of a cap in how much non-audit fees audit firms are allowed to collect in relation to audit fees (no more than 70% of the average of the fees paid in the last three consecutive financial years) (European Commission, 2017).

1.1.4 The accidental research of a forgotten concept (within the given research field) After the stream of research that created the rich library of knowledge there is today, the latest research within the field is attempting to freeze the momentum in order to review the existing bibliography. So far, in auditing research, the concept of financial reporting quality (from now on denoted as “FRQ”) has not been carefully taken into consideration (Gaynor, Kelton, Mercer, & Yohn, 2016). At times, it has been synonymously used with audit quality or assumed to have a direct positive correlation with audit quality (Gaynor et al., 2016). From an empirical standpoint, similar proxies have been used for both audit quality and FRQ within the respective research field, most notable; earnings management (meeting or just beating analysts’ forecasts, measuring discretionary accruals), timely loss recognition and financial statement restatements (Gaynor et al., 2016).

1.2 Problem Formulation

1.2.1 Putting financial reporting quality in the spotlight

One paper within audit quality research suggests that future research should be more precise and aware of distinguishing FRQ from audit quality (Gaynor et al., 2016). With that in mind, not much research has indeed been done with a focus on NAS’s effects on the quality of financial reporting, without having the auditor independence as the primary investigation concept (Craswell, 1999; Hay et al., 2006; Wines, 1994). This leaves an opportunity which this paper aims to embrace.

1.2.2 Earlier research within financial reporting quality

Similarly, as the field of audit quality has not paid much attention to FRQ, the field of financial reporting research has not paid much attention to the auditing side of things. Unintentional crossovers of proxies do, however, exist as mentioned earlier (Gaynor et al., 2016).

5

There is no unison definition of what precisely FRQ is, and therefor different approximations are used when operationalizing the concept (McDaniel, Martin, & Maines, 2002). The broad nature of FRQ (denoted accounting quality in certain papers) has allowed a diverse set of research approaches, such as the association to international accounting standards (Ahmed, Neel, & Wang, 2013; Muller, Riedl, & Sellhorn, 2015), companies’ reputations (Cao, Myers, & Omer, 2012) and the characteristics of CFOs (Aier, Comprix, Gunlock, & Lee, 2005). From an empirical standpoint, auditors’ opinions have surprisingly not been used to a greater extent as a proxy for FRQ. The auditor’s word is the accumulation of the audit process, which has the objective of determining whether the financial reporting is following legal obligations and representing the underlying economics of the firm (M. Geiger & Raghunandan, 2002). Whenever the qualified auditor opinions have been used in previous papers, it has been to proxy the independence of the auditor and not FRQ.

1.2.3 Researching financial reporting quality in a Swedish Setting

By performing this study in a Swedish context, the narrow portfolio (which is currently dominated by the US, UK, and Australia) of examined countries will be expanded. Furthermore, Swedish legislation requires the so-called bigger private companies to disclose their information regarding audit fees and non-audit service fees (Årsredovisningslag, SFS 1995:1554). This opens a new empirical domain, namely the ability to investigate other firms than public ones. Aside from the empirical arguments, Sweden is considered, recently, on an international level to have relatively high national FRQ. It should be noted that studies within this domain are few, and those who are referred to down below have only examined public companies. Thus, it must be assumed that the findings apply to private companies as well. There is no empirical evidence that can support the statement.

Two papers, both using earnings management measures to approximate FRQ, ranked Sweden #14 and #7 respectively (the U.S was ranked #1 in both papers) (Bhattacharya, Daouk, & Welker, 2003; Leuz, Nanda, & Wysocki, 2003). It is not considered to be very high; however, a much more recent paper placed Sweden at fifth placement among the studied countries of having high overall FRQ, including audit factors in addition to earnings management measures (Tang, Chen, & Lin, 2016).

6

From a conceptual perspective, this alters the current perception of the findings' FRQ since the interest of shareholders is out of the equation. The major stakeholders who are of interest are mainly governmental tax authorities and institutional providers of credit. Greater capital providers usually have a more active role and in private firms (Chen, Hope, Qingyuan, & Xin, 2011).

Another consequence of the removal of external shareholders is the diminishing effects of the tenets of agency theory. Since public firms are owned by shareholders, but controlled by a board of directors and CEO, there is a situation where agents can be used to monitor the operations, so they fall in line with the visions of the principals. In private firms, the agency cost, which arises because of the separation of ownership and control, is no longer an argument for a high qualitative financial report (Hope, Thomas, & Vyas, 2013). With that said, there are lesser incentives for private firms to have high FRQ than public firms (Hope et al., 2013). Simultaneously, firms with low agency costs, such as private firms, have shown to be keener to purchase NAS from their incumbent auditors since they are not as dependent on external stakeholders’ perception of the auditor’s independence (Firth, 1997).

The results generated by past research have, in the clear majority of the cases, been based on publicly listed companies (Craswell, 1999; Firth, 2002; Hay et al., 2006; Lennox, 1999; Wines, 1994). Drawing conclusions from these with the intention to make them generally applicable is biased since the sample does not represent the majority of the population of firms. It is equally important to investigate the association for private firms in order to capture a more substantial portion of the population. The same argument was once brought up as a criticism towards the accounting theory Positive Accounting Theory, stating that the theory lacked external validity because of excluding private firms in the sample (Chambers, 1993; Watts & Zimmerman, 1978). This background strengthens the importance of this paper by contributing to the broader discussion. An additional empirical benefit from conducting the study in Sweden is the outline of the auditor’s reports. Auditor reports with qualifications are detailed in the sense that it must be specified of what is lacking with the financial reporting, which levitates the discussion from “low” or “high” to a spectrum of “low quality” measures.

7

This has been taken into consideration before in New Zeeland, but with a fewer amount of dimensions than what is possible in Sweden (Hay et al., 2006). From a conceptual viewpoint, this enables a new way of analyzing the results and provides an opportunity to examine how certain non-audit services are correlated with different reasons behind a qualified auditor report. This enables differentiation between pre-audit and post-audit FRQ, which provides even more in-depth analysis and nuanced discussion, which have not been done in previous research (Gaynor et al., 2016).

1.2.4 How non-audit services are related to financial reporting quality

The fundamental discussion which underlies this paper is the cult-like behavior from the academic world to find evidence for the proposed detracting effect NAS poses on auditor independence. Since history displays results of mixed nature, innovative ideas are necessary in order to shed light on new areas within the topic. We will attempt to investigate, not the negative effects of NAS on the auditor’s independence/quality, but whether the provision of NAS can be relatively high even if there is a low factual quality of FRQ. In other words, we will not attempt to evaluate of quality of the audit. Furthermore, it is of interest to investigate if this varies depending on if the NAS has been provided by one of the big four firms or a smaller audit firm in Sweden. Previous research suggests that the quality of big four audit firms’ audits are of higher quality (Eshleman & Guo, 2014) compared to non-big four audit firms. These findings do not cover non-audit services. Since the Swedish setting allows us to explore several layers of “low FRQ,” we can investigate how different types of auditor remarks are correlated with FRQ.

The proposed relationship between the two concepts does not rely on much theoretical foundation. In previous research on auditor independence and quality literature, two theoretical mechanisms have been identified. Knowledge spill-over speaks for a positive association between NAS and audit quality since the audit firm grants greater insight of the client’s underlying business and can thus perform a better audit (Beck & Wu, 2006; Chan, Chen, Janakiraman, & Radhakrishnan, 2012; Lim & Tan, 2008; Palmrose, 1986; Robinson, 2008; Simunic, 1984; Svanström, 2013). Economic dependence implies a negative association between NAS and auditor independence (and thus audit quality) since NAS fees usually have higher margins than ordinary audit fees.

8

It results in audit firms being dependent on the revenue generated from NAS to such a degree that the objectivity becomes threatened (Burgstahler & Dichev, 1997; Frankel et al., 2002; Reynolds et al., 2004; Ruddock, Taylor, & Taylor, 2006). These are heavily focused on the audit problematization, but it has been implied that they ultimately affect the FRQ (Tepalagul & Lin, 2015). These competing theoretical standpoints may thus apply to the analysis of results generated by this study.

1.3 Purpose of Study

The main purpose of this study is to explore whether and how the provision of non-audit services from incumbent auditors influence private company’s FRQ. Furthermore, the study aims to develop an understanding of how the value of the provided non-audit services may be different depending on if a big four audit firm provides them or not. 1.4 Research Question

How does the provision of non-audit services from incumbent auditors relate to Swedish private company’s FRQ? Does this vary depending on the type of provider; a big four audit firm, or not?

9

2 Literature Review

In this section, the wide array of available literature within the given research field is introduced and thoroughly explained. The section’s purpose is to provide a frame of reference and establish theoretical foundations that the thesis is built upon. Finally, based on previous research and theoretical mechanisms, several hypotheses are developed to fulfill the purpose of the study.

2.1 What is Financial Reporting Quality?

2.1.1 According to prior research

The literature within the area of FRQ has not provided a clear definition of the concept (Habib, 2012; McDaniel et al., 2002). This has been acknowledged to be an issue since this has created difficulties in attempting to operationalize and measure the quality of financial reporting (Beest, Braam, & Boelens, 2009). Researchers have bypassed this by making indirect measurements of FRQ in order to grasp the concept, such as earnings management, financial restatements, and timeliness (Ahmed et al., 2013; Aier et al., 2005; Barth, Landsman, & Lang, 2008; Cao et al., 2012).

These indirect ways of measuring the concept have led to inconsistent results in what determines the quality of financial reporting. These are expected outcomes since financial reporting is a broad concept which is not solely about financial information, but also about non-financial information and how these are disclosed in order to satisfy the demand of stakeholders (Beest et al., 2009). To have earnings management as an indicator of FRQ deserves elaboration since reporting incentives and the forces shaping them are an integral part of FRQ (Watts, 1986). This is because the reporting is based on information that is privately held within the firm, and managers are in a position where they can adjust information presented (Watts, 1986).

Earnings management’s origin of being a proxy for FRQ can be traced to the field of audit quality research and the idea of economic dependence. When an economic bond exists between the audit firm and a client of theirs, incentives exist to permit earnings management, which results in biased financial reporting (Deangelo, 1981; Magee &

10

Tseng, 1990). Since economic dependence is required to be proven or assumed for this proxy to hold, it does not satisfy the purpose of this thesis. The deep anchoring in the auditor independence literature further diminishes its applicability.

Since the concept of FRQ is undefined (Habib, 2012; McDaniel et al., 2002), it is required to be proxied in order to measure it. Our choice of proxy will be the qualified audit report. This has previously been used in the audit quality research field. In one paper, the qualified auditor’s report is used as a proxy for auditor independence in appearance, and the main argument is founded in the definition of auditor independence - the conditional probability that a breach will be reported by the auditor or not (Wines, 1994). That is, if there are less qualified audit reports in the presence of high NAS fees (the independent variable in this paper), this may cause the perceived auditor independence to decrease. Some of the following papers which investigate the similar relationship base their argumentation on the same principle (Firth, 2002; Hay et al., 2006). However, another paper states that the perceived independence problem is inconsistent and indirect and that the testing for the same relationship instead is a direct measurement of auditor independence (Craswell, 1999).

Despite the argumentation done in the audit research field, this is not the argumentation for our choice of proxy (since we do not test for audit independence). Our argument for using the auditor report as a proxy is because the fundamental objective of the auditor report is to provide a statement whether the annual report has been prepared in accordance with applicable law on annual accounts, and also whether the annual report gives a true and fair view of the company’s result and position - according to 9 kap 31§ (Aktiebolagslag). Furthermore, the audit report shall contain statements about whether the general meeting shall approve the balance sheet and income statement. The auditor’s acceptance or rejection of the balance sheet and income statement must also be included. Finally, he auditor must note whether and how the general meeting has decided to to allocate the company’s profit or loss (ABL 9 kap 32§).

11

However, attempts have been made to create a definition of FRQ. In the paper by Gaynor et al. (2016, p. 2), the authors define higher FRQ as reports which “are complete, neutral, and free from error and provide more useful predictive or confirmatory information about the company’s underlying economic position and performance.”

2.1.2 According to IASB / FASB

The notion that financial reporting is a broad concept originates from the stated objectives of financial reporting, according to FASB and IASB. The purpose of financial reporting is to provide stakeholders such as providers of equity with financial information that truthfully reflects the underlying economics of the entity. The aim is to create a market with an efficient allocation of capital (FASB, 1999; IASB, 2008). Another part of the complexity of the concept is the qualitative characteristics that are difficult to operationalize. Fundamental pillars of financial reporting are relevance and faithful representation (IASB, 2008). The meaning of relevance is to provide users with financial information that makes them capable of making decisions based on the provided data (FASB, 2010). Reliable information is information that does not contain errors, is complete and neutral (FASB, 2010). Financial reporting should also possess the characteristics of understandability, comparability, verifiability, and timeliness (IASB, 2008).

2.1.3 According to Swedish legislation

In Sweden, the basis for financial reporting can be found in the legislation. Two mandatory accounting acts exist in Swedish law, the Annual Accounts Act of 1995 (Årsredovisningslagen) and the Book-keeping act of 1999 (Bokföringslagen).

Furthermore, the Swedish Accounting Standards Board (also called BFN, Bokföringsnmämnden), which is a governmental body under the Ministry of Finance, is responsible for the development of the “generally accepted accounting principles” since 2004 (Bokföringsnämnden, 2020). The Annual Accounts Act of 1995 is based on EU directives and contains requirements on qualitative characteristics (similar to the IASB and FASB). Every financial report which is created following the named accounting act must be presented in a perspicuous manner, provide a fair representation of the business’s financial position and results, and obey the principle of “good accounting practice.”

12

2.1.3.1 Generally Accepted Accounting Principles

Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (“God redovisningssed” in Swedish, denoted as GAAP hereafter)) is a special practice unique to Sweden. It was introduced in the Book-keeping act of 1976, where the idea was to create a praxis for a lesser circle of entities required to keep accounts. This had a crucial role in the development of the concept, which it is today (Skatteverket, 2019). At the same time, BFN was created to make recommendations and statements, and by doing this, codify and establish the concept of GAAP for economic entities to follow (Skatteverket, 2019). GAAP underwent the next major overhaul with the introduction of the Annual Accounts Act of 1995. In a comment from the Swedish government during the introduction of the law, it can be read that GAAP will be a way of making sure that financial entities follow standard and praxis’ set by authorities.’ Examples of authorities are the Swedish Accounting Standards Board and Finansinspektionen (Sweden’s financial supervisory authority). GAAP will never be possible to use as an excuse to avoid other legislations set in the Swedish law (Skatteverket, 2019). This is done by having companies obligated to follow GAAP (2 kap. 2§ ÅRL).

2.2 What Determines the Level of Financial Reporting Quality?

Because the concept of FRQ has been indirectly measured in previous research, consequently, there are no clear answers in what causes the quality to be either high or low. Quality is, in a sense, also dependent on the user. Different users may find different kinds of information useful in different contexts (Botosan, 2004). Nevertheless, researches have been keen to find answers to the question in different forms and different results. The weight of importance is allocated to these different kinds of measures since they are supposed to indicate or indirectly represent FRQ. The determinants can be divided into different levels; individual, firm, and institutional levels.

2.2.1 Individual-level determinants.

Domains of accounting research have investigated whether the qualitative characteristics of the firm are determinants of FRQ. Research suggests that the number of restatements (a proxy for FRQ) is negatively associated with a firm’s CFO’s financial expertise (Aier et al., 2005). Financial expertise comprises components such as CPA certification, a higher amount of experience, and education (such as an M.B.A) (Aier et al., 2005).

13

Putting the CFO aside, other research has investigated the correlation between earnings management and managers’ equity incentives (such as stock-based compensation and stock ownership) (Cheng & Warfield, 2005). They find that managers are more likely to report earnings that meet or just beat analysts’ forecasts in the presence of high equity incentives, concluding that high equity incentives may indicate earnings management, which in turn impair FRQ (Cheng & Warfield, 2005). Other research nuances the compensation discussion, suggesting that fair value accounting regulations for securitization gains provide CEOs with a suitable tool for managing earnings, and thus risking the quality of FRQ (Dechow, Myers, & Shakespeare, 2010).

2.2.2 Firm-level determinants

Aside from individual positions in a firm, the overall firm’s reputation has been found to have a positive association with FRQ (Cao et al., 2012). The potential reason behind the findings is that companies with high reputations are more careful in not committing mistakes and errors in their financial statements, which would lead to restatements and thus risk to decrease the perceived value of the firm (Cao et al., 2012). One goal of FASB’s conceptual framework is to provide guidelines that implicate and create financial information that is useful for business decisions (FASB, 2010). (Schipper & Vincent, 2003) discuss and relates the measures used to measure earnings quality and tie those measures to the FASB’s conceptual framework. Earnings quality is a vague concept, and authors have used different measures when trying to define and measure it. In a literature review within the field of earnings quality, (Dechow, Ge, & Schrand, 2010) find no single conclusion to what defines earnings quality, since quality is dependent on the decision context. Their definition of earnings quality shows that higher earnings quality illustrates a more accurate picture of the company’s performance and provide relevant information in specific decision-making areas. They also point out that earnings quality has a positive association to the firm’s fundamental performance (Dechow et al., 2010).

2.2.3 Institutional level determinants

Lastly, institutional forces have also appeared to be determinants of FRQ. From an institutional theory perspective, two primary actors shape the environment that surrounds organizations: the state and professional bodies (Scott, 1987). The chairman of the U.S Securities and Exchange Commission commented in 1998 that international accounting standards are the primary input to secure high accounting quality; that it decreases the

14

cost of capital and increases the confidence of investors (Levitt, 1998). In the EU, this became a reality with the regulation in 2002, which required companies listed on a European exchange to comply with IFRS (Regulation, No 1606/2002). Within academia, this was later investigated whether international standards increased the quality of FRQ.

It has been suggested that the voluntary application of International Accounting Standards (IAS) has a positive correlation with FRQ. Companies have shown less earnings management, more timely loss recognition, and that accounting has had more value relevance when voluntarily applying IAS (Barth et al., 2008). This, in comparison with companies that followed the Generally Accepted Accounting Principles of the US (US GAAP) (Barth et al., 2008).

In attempting to mitigate the effects of the economic environment and incentives to adopt the IAS regulations, the findings are still potentially misleading because of these forces (Barth et al., 2008). Later research suggests the opposite of the findings from Barth et al. (2008), investigating the effects of IFRS on the company’s FRQ using the same indirect measurements (Ahmed et al., 2013). The results suggest that after the adoption of IFRS, companies experience higher income smoothing, more aggressive reporting regarding accruals, and delayed loss recognition. However, management actions to meet or just beat earnings forecasts where not negatively affected (Ahmed et al., 2013). The paper states that the critical difference lies in the adoption, whether it is voluntary or mandatory. In the case of IFRS, they investigate mandatory adoption and suggest that it has an overall negative effect on FRQ (Ahmed et al., 2013).

Finally, none of the determinants mentioned above are non-financial services. Referring to the problematization chapter, in the most cases non-audit services have not been investigated as a determinant of FRQ in solitary, but audit quality has been present as well (Craswell, 1999; Firth, 2002; Gaynor et al., 2016; Hay et al., 2006; Wines, 1994).

15 2.3 Non-Audit Services

2.3.1 The current trends of non-audit services in relation to revenue for three of the big four audit firms

The term “non-audit services” (hereafter denoted as “NAS”) is used for services provided by audit firms that are not part of the regular audit process (European-Commission, 2017). In Sweden, these are categorized into audit-related services, tax-related services, and other services, and the fees paid for respective categories must be disclosed in bigger company’s annual report according to 5 kap 21§ ÅRL (Årsredovisningslag, SFS 1995:1554). The development of NAS has, over the years, been in an increasing trend, but after the EU audit reform came into effect in June 2016 the trend has reversed, as can be seen in figure 2 in the appendix (European-Commission, 2017). The average non-audit fees earned by the incumbent auditor in the EU PIE-market has decreased significantly between the period of 2015 and 2017.

Comparing this to the international development of NAS as a percentage of total revenue for the three of the biggest global audit firms, the trend does not break but continues. This can be seen in figure 3 in the appendix. The three audit firms are EY, Pwc, and KPMG, where EY has been the global leader in terms of NAS to total revenue ratio from 2012 until 2019. In Sweden, the development of NAS in relation to total revenue has declined in growth during 2018 for EY and Pwc. For KPMG, the trend of increasing NAS is continuing. EY still stands as the leader in this regard though, see figure 4 in the appendix. 2.3.2 Non-audit services as a predictor of audit quality and auditor independence in

the majority of previous research

In prior literature, NAS has been acquainted with the work of the auditor, namely if the provision of NAS risks to impair the auditor’s independent position and thus the quality of the performed audit (Callaghan et al., 2009; Defond, Raghunandan, & Subramanyam, 2002; Fargher & Jiang, 2008; Robinson, 2008; Sharma & Sidhu, 2001). The resulting research has given rise to mixed results, and it is still unclear whether auditor’s independence is impaired by the joint provision of audit services and non-audit services (Tepalagul & Lin, 2015).

16

Regulatory bodies have nevertheless been focusing on prohibiting and restricting the phenomena, with the introduction of the Sarbanes Oxley Act in 2002 and the EU directive 2014/56/EU.

2.3.3 Non-audit services as a predictor of other concepts

There have been other cases where the provision of NAS has been predictors of other concepts than only auditor independence and quality. For example, it has been tested whether the provision of NAS has an impact on a firm’s rating in the bond market. The regression analysis showed that high levels of NAS are negatively associated with a firm’s bond rating (Brandon, Crabtree, & Maher, 2004). Another paper tests if the provision of NAS influences the quality of FRQ (proxying with the ability of financial statements to predict firm’s future cash flows) and information risk, a part of capital markets. (Nam & Ronen, 2012).

The information risk is proxied by the cost of capital and bid/ask spread. The findings suggest that the provision of NAS improves the quality of the financial statements and reduces the information risk, thus fortifies the idea of using NAS as a predictor of FRQ (Nam & Ronen, 2012).

2.3.4 Why do audit clients purchase non-audit services?

One might wonder why audit clients purchase NAS in the first place; why has it become a pillar of attention for decades within accounting research? NAS is a broad concept, but by splitting it into its components, perhaps some of these can be traced to motivations as to why firms purchase these services. One idea originates from a paper which suggests that the purchase of management advisory services (in general, not specifically from audit firms) increases financial performance, at least for small firms (Kent, 1994). This may imply that there is a belief that such services from audit firms will generate at least the same results, especially when combining these findings with other evidence. This suggests that the provision of NAS related to financial information systems is positively associated with a higher market value of equity (Lai & Krishnan, 2009).

17

Another reason why firms purchase NAS, as already mentioned in the section regarding agency costs, is that firms with high agency costs are keen to purchase less NAS from the incumbent auditor since it may jeopardize the auditor's independence in appearance (Firth, 1997).

2.4 Prior Research Regarding the Relationship Between Financial Reporting Quality and Non-Audit Services

Recall the previous discussions where the most research of NAS has been as a predictor of audit independence and audit quality. When researchers have investigated NAS’ effect on the auditor’s independence, the proxies used have, for the most part, been proxies for FRQ such as earnings management, qualified audit opinions, earnings conservatism/restatements and capital market perception studies (Habib, 2012). However, the concluding remarks are not about the level of quality for the financial reporting, but of the impairment of auditor independence (Agrawal & Chadha, 2005; Brandon et al., 2004; Dhaliwal, Gleason, Heitzman, & Melendrez, 2008; Frankel et al., 2002; Ruddock et al., 2006; Wines, 1994).

Two hypotheses dominate the research of NAS’s effect on FRQ. The first one is about knowledge spillover effects, which states that NAS is positively correlated with FRQ. When professional service consultants are offering their services to the client firms, they develop internal knowledge and understanding of the underlying businesses. This is later “spilled over” to the auditors when they audit, which can use the knowledge when planning the audit and making risk assessments. It ultimately improves the performed audit, and thus the FRQ (Tepalagul & Lin, 2015).

The second hypothesis is about NAS having a negative association with FRQ because of economic dependence. The idea argues that higher NAS fees make the auditor dependent on the revenue generated, and this puts the auditor’s objectiveness at risk. If the auditor becomes less independent, then the audit will be misguiding, and there is a risk that the FRQ decreases as a consequence (Tepalagul & Lin, 2015).

Since there are two hypotheses, or theoretical mechanisms, which are contradicting each other, our findings have the potential to support either one.

18

There is, however, not possible to correctly, or with high confidence, state that for example a positive association between high levels of NAS and high FRQ signifies knowledge spillovers. The tension also clearly shows the lack of consensus in previous research.

Some research has found evidence that supports the first hypothesis of knowledge spillover, and denies the second hypothesis – for both actual FRQ and perceived (Koh, Rajgopal, & Srinivasan, 2013). This is contradicting earlier research, which found that the market tends to value quarterly earnings surprises less if a high amount of NAS has been disclosed (Francis & Ke, 2006). There is, however, is no rule which dictates that actual FRQ and perceived must be consistent, and that perceived quality can vary depending on the circumstances (Church & Zhang, 2011; Dopuch, King, & Schwartz, 2003).

2.5 Audit Quality’s Relation to Financial Reporting Quality

It is essential to be aware that audit independence and FRQ are two different concepts, and that this has not always been entirely clear in previous research (Gaynor et al., 2016). To distinguish FRQ from audit quality, the differences and similarities must be sorted out and understood. The relationship has historically been seen as direct and almost the same, especially among legislators and regulators. In turn, this has led to the overhauling changes in the legislation regarding NAS (Church & Zhang, 2011). Aside from the mixed results in how NAS affects FRQ for public firms, previous research suggests that – in general – FRQ is affected by the overall quality of the firm’s external audit (Behn, Choi, & Kang, 2008; Teoh & Wong, 1993).

External audit quality has been examined by for example looking at the characteristics and industry specialist knowledge of the auditors, resulting in evidence which suggests that these characteristics are associated with higher levels of FRQ (Balsam, Krishnan, & Yang, 2003; Carcello & Nagy, 2004; Dunn & Mayhew, 2004; Yanyan, Lisheng, & Yuping, 2015). Lower reporting quality is a product of auditor rotation (mandatory under the new EU directive), which in turn results in shorter audit tenure. Shorter audit tenure has been found to negatively impact the quality of the financial reporting (Carcello & Nagy, 2004; Geiger & Raghunandan, 2002; Litt, Sharma, Simpson, & Tanyi, 2014).

19

The direct relationship between the two concepts goes further where for example literature reviews create theoretical frameworks where the effect on audit quality directly impacts the quality of financial reporting (Habib, 2012; Tepalagul & Lin, 2015). It is thus vital to nuance the two concepts and examine more carefully into their dynamic relationship, and how one affects the other on a multi-dimensioned level.

The results from the characteristics of the audit and its effect on FRQ must be interpreted with skepticism. There is a potential endogenous relationship where high pre-audit FRQ may lead to the hiring of higher quality audit, and that the characteristics of the audit do not affect the FRQ (Gaynor et al., 2016). Similarly, low pre-audit FRQ may lead to the hiring of low-quality auditing, once more removing the one-way effect of AQ on FRQ (Gaynor et al., 2016). In situations where there is low pre-audit FRQ, then there may be a correlation with AQ if the post-audit FRQ is significantly higher (Gaynor et al., 2016). This discussion has been lacking in previous research. Therefore future studies are encouraged to consider these findings to make a more coherent and accurate study and analysis.

2.6 Development of Hypotheses

FRQ has been investigated heavily for similar reasons as audit quality (Biddle, Hilary, & Verdi, 2009). Both areas are of high importance in the capital markets (Defond & Lennox, 2011). They have also become the center of attention in the aftermath of past accounting frauds and financial crises (Lennox & Pittman, 2010). However, the relationship between NAS and FRQ is yet still to be thoroughly explored. Previous research suggests that there is an endogenous relationship between FRQ and audit quality, which indicates that certain findings and assumptions regarding the audit research field could possibly be applicable in the FRQ field (Gaynor et al., 2016). What previous research has failed to consider is this relationship and mixed the two concepts without further reflection of the similarities and differences (Gaynor et al., 2016). In light of this, we assume that the knowledge spillover effects and economic bonding theory are present in the case of FRQ as well, and these will be the foundation in which the hypotheses are developed. Recall the discussion from the literature review. The two theoretical hypotheses conflict with each other as they predict different relationships between FRQ and the provision of NAS.

20

There is as well no unison research which either accepts or rejects either one (Francis & Ke, 2006; Koh et al., 2013). One possible hypothesis developed from this can be done similarly to (Svanström, 2013) which because of the opposing effects predicts no relationship between FRQ and NAS.

However, this paper aims to target a different approach and take the apparent increase in provided NAS worldwide and Sweden into account (Appendix Figure 3 & figure 4). In other words, their clients keep purchasing these services. In light of this, the economic theory of marginal utility could potentially predict the direction of a proposed relationship between the two concepts. Marginal utility is the economic term of the utility a consumer gains by consuming one additional unit of a good or service (Kauder, 2015). In decision making, it also implies that a consumer is willing to purchase a good or service if the marginal benefit is larger than the marginal cost (Kauder, 2015). If firms are considered analogically to consumers, they purchase services with the expectations that their benefits will outweigh the costs. Clean audit reports could potentially be assumed to be a side effect (impossible to identify the main purpose behind the purchases) of this, and thus support the prediction of increased levels of provided NAS correlates with higher FRQ.

Other potential factors driving this increase has been suggested in the literature review to be expectations from firms to increase their financial performance by purchasing these services (Kent, 1994). Furthermore, since companies with higher agency costs have been suggested to purchase less NAS, the absence or lower agency costs could potentially make companies keener to obtain these services (Firth, 1997).The discussion leads to the expression of our first hypothesis:

H1: The provision of NAS by an incumbent audit firm has a positive association with FRQ.

Previous research has emphasized separating NAS into the three categories; audit-related services, tax consultancy, and other services (Kinney, Palmrose, & Scholz, 2004). Conveniently, these three categories are also disclosed in the annual reports as a legal requirement in Sweden.

21

By testing for these different categories, the research questions become more nuanced (Abbott, Parker, Peters, & Rama, 2007; Beck, Frecka, & Solomon, 1988; Chung & Kallapur, 2003; Deberg, Kaplan, & Pany, 1991; Joe & Vandervelde, 2007; Parkash & Venable, 1993).

For the first type of non-audit service, there are mixed findings in previous literature regarding audit-related NAS’s correlation with FRQ. According to two American papers, Kinney et al. (2004) and Paterson et al. (2011), the provision of audit-related NAS increases the risk of financial restatements, which they argue is a measure of FRQ. These findings are challenged by Wahab (2014), who conducted a study in Malaysia and found that audit-related NAS decreases the probability of financial restatements. Svanström (2013) also found supporting evidence of audit-related fees positive correlation with knowledge spillover effects, causing an indirect impact on FRQ. Even though his discussion surrounds the concept of audit quality, the indicative knowledge spillover effect may suggest an effect on FRQ as well. Robinson (2008) finds no correlation between audit-related NAS and audit quality and attempts to reject its causative relationship with the knowledge spillover effect. The hypothesis developed with the background of these various findings predicts that there is no correlation between the provision of NAS by the incumbent audit firm and FRQ:

H1a: There is no association between the provision of audit-related NAS by an incumbent audit firm and FRQ

Tax-related NAS has proven to constitute the greatest proportion of provided NAS by audit firms (Arruñada, 1999). Several papers have investigated the proposed effect on audit quality and FRQ, and as described above the suggested relationships with the knowledge spillovers effects will be considered as potential effect on FRQ. Huang, Mishra, and Raghunandan (2007) find no systematic evidence regarding a correlation between tax-related NAS and FRQ, this rejecting the proposed knowledge spillover effects. Their findings are further supported by Koh (2012). There is however a large stream of research which finds evidence that supports the knowledge spillover effect caused by the provision of tax-related NAS (Becker, Defond, Jiambalvo, & Subramanyam, 1998; Gleason & Mills, 2011; Kinney et al., 2004; Paterson & Valencia,

22

2011; Robinson, 2008; Simunic, 1984; Svanström, 2013; Wahab, Gist, & Majid, 2014). The overwhelming consensus from previous research causes the hypothesis to predict a positive correlation between tax-related NAS and FRQ.

H1b: The provision of tax-related NAS by an incumbent audit firm has a positive association with FRQ

Other NAS services are undefined services, which can include services such as corporate finance, investment advisory, and legal counseling (Svanström, 2013). In previous research, there are somewhat mixed findings regarding their correlation with the knowledge spillover effect. Kinney et al. (2004) finds a negative association with FRQ and thus suggesting a relationship with the theoretical mechanism of economic dependence. Svanström (2013) find somewhat mixed results and reserves himself from drawing a conclusion regarding the relationship. Robinson (2008) and Huang et al. (2007) find no evidence which supports the correlation between other NAS and FRQ. Because of the mixed findings, the argumentation will be in line with the argumentation of hypothesis 1. Since this classification of NAS consists of the undefined services - “the leftovers” - the reason why companies purchase these services are to gain a marginal benefit for the firm.

One potential goal of these services may be to avoid receiving remarks from the auditor and thus enhance the FRQ. Based on this argumentation, the third class of NAS is expected to be positively correlated with FRQ:

H1c: The provision of other NAS by an incumbent audit firm has a positive association with FRQ

Refer to the purpose of our thesis. Aside from testing the relationship between FRQ and the provision of NAS, it is also of interest to explore whether this relationship is affected depending on if the incumbent audit firm belongs to one of the big four or not. In previous research, there has been concluded that the quality of audit services provided by a big four firm is generally of higher quality compared to non-big four audit firms (Eshleman & Guo, 2014).

23

More specifically, it has been found that there are higher earnings response coefficients for clients that use Big Six audit firms (at that time, there were six instead of four) compared to the opposite. This indicates that investors perceive earnings reports generated by Big Six audit firms as more credible (Teoh & Wong, 1993). Another study reports the existence of an audit fee premium for services conducted by Big Six auditors, suggesting that these audit services are perceived as higher quality since industry experts conduct them. Thus there is a demand for these higher-quality services and the fee premium attributed to them (Craswell, Francis, & Taylor, 1995). From the client’s perspective, they are facing a lesser risk of their audit firm to be involved in litigation if it belongs to the Big Six (Pierre & Anderson, 1984). Lastly, it has been found that clients of Big Six firms are less likely to file reports containing errors and irregularities, indicating that the post-audit FRQ is high when audited by a Big Six firm (Defond & Jiambalvo, 1991).

Referring to this research, we assume that the quality of the provided NAS will thus also be of higher quality. Previous research has yet to explore this assumption; this thesis will attempt to fill this void.

From this, one additional two hypotheses will be tested:

H2: The provision of NAS by an incumbent audit firm has a stronger positive association with FRQ if the incumbent audit firm belongs to one of the big four audit firms.

24

3 Constitutionalia

This section concerns constitutional actors who are a part of the thesis’s frame of reference but are not anchored in academic work. These are explained to the reader for an easier understanding of the several regulatory and business actors the contribute to the thesis.

3.1 The K-series Regulatory Framework

The generally accepted accounting standards of Sweden consist of a collection of standards; K2, K3, and K4 (Bokföringsnämnden, 2020). There is a fourth one, but this is dedicated to non-profit organizations and registered religious communities, which presents simplified annual reports (BFNAR:2010:1). The K3 framework is the main regulatory framework within the K-series but shall not be applicable by companies which may apply K2 or K4 (BFNAR 2012:1). Lesser companies are supposed to follow the K2 regulatory framework (BFNAR 2016:10).

The definition of a lesser company is a company that does not fulfill at least two of the following criteria: annual net revenue of at least 80 million SEK, total assets of at least 40 million SEK and / or at least 50 employees (1 kap. 3§. 4p. ÅRL). Companies which are publicly listed are supposed to follow the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), and are sometimes called K4 companies, according to 7 kap. 32§ ÅRL (Årsredovisningslag, SFS 1995:1554). BFN is only setting the norms for the ongoing accounting for these companies (Drefeldt & Törning, 2020).

3.2 Retriever / CreditSafe

Retriever is a business database containing data on all Swedish companies. The database includes company numbers, number of employees, board composition, group structures, annual reports, income statements, and balance sheets (Retriever, 2020).

3.3 The Swedish Inspectorate of Auditors

Swedish Inspectorate of Auditors (Revisorsinspektionen) is the Swedish government’s expert authority in matters regarding auditing and auditors.

25

The authority supervises authorized and approved auditors and auditor firms. They also examine and authorize auditors in Sweden. Their role is to ensure that generally accepted accounting principles (god redovisningsed) are practiced and developed properly and ensure that there are enough accountants in business performing audits of high quality, which meets high ethical requirements (Revisorsinspektionen, 2020).

26

4 Methodology and Empirical Method

This section provides an overview of the methodological foundations for this thesis and the methods utilized for data collection. Furthermore, the operationalization of concepts is made and explained, which prepares the reader for the empirical analysis.

4.1 Research methodology

4.1.1 A philosophical view of science

To fulfill the purpose of this study and explain NAS’ effect FRQ, we embrace a positivistic research philosophy. These are the practices and norms of the natural scientific epistemological orientation (Bryman, 2015). This implies that general assessments are made by finding causative relationships between concepts (Saunders, 2012).

4.1.2 Scientific reasoning

It entails that with a positivistic standpoint that the deductive theory, regarding the linkage between theory and research, is in order. What this means, is that the theory leads the research; the research is deducted from existing theory. Hypotheses and ideas are built based on what is previously known, which shall then be tested for causal relationships (Bryman, 2015). In order to test the relationship between concepts, they need to be transformed from their abstract nature into measurable components (also known as variables) (Bryman, 2015). This transformation process brings certain risks.

Primarily, the first risk identified when transforming abstract concepts to measurable variables is that those variables are not truly representable of the concepts of interest. There will be subjective judgment involved in this process, even though using previous research as reference points (there is not always a prevailing consensus in the academic world), and this subjectivity brings risk to the validity of the testing of the hypotheses (Bryman, 2015).

Another risk associated with the testing of the relation between two variables is that the relationship is spurious; both variables are related to a third variable (Bryman, 2015).

27

Similarly, other variables might be associated with the dependent variable, which the test does not account for. This puts emphasis on collecting data for so-called control variables and include these in the analysis to mitigate this risk (Bryman, 2015). A third risk associated with the transformation process is the initial hypothesis development and assumptions associated with these; do the hypotheses rest on reliable assumptions that capture the concepts of interest?

To counter these risks, it is important to base the assumptions on established theory or theoretical mechanisms that could potentially explain the assumed relationship (Bryman, 2015).

The last risk worthy of mentioning, which is associated with a deductive approach, is the final stage of the analysis, the inference of the proposed relationship between the dependent variable and the independent variable(s). Since the data underlying the variables are collected simultaneously and at a single point in time, it is difficult to know the direction of the relationship. The analysis must refer to previous research and – in some instances – common sense when stating which concept acts as the dependent variable (Bryman, 2015).

Before presenting the argumentation to why this thesis possesses the deductive characteristics, it serves its purpose to contrast the deductive approach with its contrariety; induction. Inductive theory entails that theory is developed from observations and findings (Bryman, 2015). The approach is more closely related to the world of social science, compared to the deductive approach, which is more dominating within natural science (Saunders, 2012). The reason is that in the inductive approach, premises are not set beforehand but rather after observing a potential problem. The criticism of the deductive approach - that human’s understanding and reflection of the world are not taken into consideration - is one of the strengths of the inductive approach (Saunders, 2012).

Comparing what has been written regarding deductive vs. inductive within the premises of this paper, the deductive approach is the most applicable. The paper aims to investigate whether there is a positive relationship between FRQ and the provision of non-audit services by an incumbent auditor. “Relationship” should be heavily emphazised.