Profitability analysis of a strategy to increase housing quality in

socially disadvantaged large housing estates

Gunnar Blomè

Malmö University, Department of Urban Studies, P.O. Box 205 06 Malmö Department of Real estate and Constructive management

Royal institute of technology Email: Gunnar.blome@mah.se

Abstract

The purpose of this study is to analyze the profitability of a strategy to increase housing quality in socially disadvantaged large housing estates. The primary issue is to identify costs affected by poor management and neighbourhoods’ social problems. Based on detailed case study material from a socially deprived area in the city of Malmö (Sweden), detailed economic data is discussed and analyzed. The empirical data indicates that it is profitable to have a clear and active housing management strategy. The value of the study, from a practical perspective is a deeper knowledge of difficulties and possibilities to stabilize these housing areas and to find sustainable work methods. From a research perspective this provides information that can be used for improved knowledge of comparative management studies.

Key words; Large housing estates, social disadvantaged, Profitability, Strategy, Sweden.

Introduction

Housing standards and living conditions were poor in Sweden in the beginning of the 20th century. The urbanization led to problems with housing shortage without improvement of infrastructure. City live was many ways characterized by misery, health problems and issues with overcrowded buildings. The Swedish government decided in the middle of the 1940’s, that every single municipality should own their own housing company. This new idea was later described as a type of public housing, creating social values by providing better housing conditions to affordable costs to all kind of social groups (Ramberg 2000).

Large housing estate neighborhoods were in the beginning inhabited by Swedish working class people, followed by work immigrants and refugees. Some of these estates are today popular and are functioning well. But with some areas, you find significant social problems and segregated areas in bad condition. These neighborhoods have a large number of

low-income households, unemployment rates are above average and they have become concentrated areas for ethnic minorities (Andersson 2002). The same Pattern has emerged all over the Western Europe (Van Beckhoven 2006). In extreme cases parallels can be drawn to the general housing standards in the Swedish cities back in the beginning of the 20th century with problems of overcrowding, bad health and social deprivation (Nordström 1984, Ramberg 2000).

Background

In Malmö, Sweden, the area Herrgården has become a prime example of a non-functioning large scale neighbourhood. Herrgården, described as the worst part of the more famous

district called Rosengård, a typical million dwelling program area built at the end of the 1960s. The general picture is major social problems, poverty and a deteriorated physical environment reflected in bad school performance, poor health, riots, fires and high crime rates. One of Herrgården´s characteristics is the multi-cultural mix with residents from different Parts of the world. Of the entire population, 98 percent are of foreign origin, 50 percent are the age of 18, only 16 percent of the adult populations have a post-secondary education and the

unemployment rate is 87 percent. Herrgården is one of Sweden's most overcrowded neighbourhoods with 1360 rental dwellings and 4878 documented residents (Malmö City Office 2008). Recent calculations by police and social workers estimated that up to a total of 9 000 people could be accommodated in the neighbourhood.

Research problem

Herrgården is divided among several private property owners and a large proportion of the properties have changed ownership several times over the last 15 years. This situation has adversely affected the neighbourhood with an absence of sustainable efforts over time. Malmö municipality has been concerned with this situation and let the municipal housing company acquire 6 properties in 2006 with 294 dwellings. Market value was set at 132 million SEK (449 000 SEK per apartment) which many considered too high based on the lack of

maintenance and the neighbourhoods’ social situation. The objectives behind this purchase was to try to change the negative situation and to create a good example in order to motivate other private property owners to renew their buildings, improve maintenance and housing management. Large amounts of resources have been invested to change this neighborhoods: poor social- and physical condition. In addition there are several reasons behind today’s situation and many questions have to be answered on how effectively solve problems and how to clarify responsibilities. An interesting question is whether the presented example is

profitable and if there are concrete alternatives to deal with the social deprived situation and still achieve lasting positive effects in Herrgården.

The aim of this paper is to identify costs affected by poor management and

neighbourhoods’ social condition and to analyze and discuss profitability and different investment strategies.

Research methodology

The empirical data used in this study is based on a detailed four year case study in one of Swedens (Malmö) most deteriorated neighborhoods. The research project started as a project documenting MKB fastighets AB, Malmo’s municipality housing company’s renewal process in Herrgården. Documentation material has been collected by passively participating in the

change during process the first year, and then returning with monthly visits and interviews with staff and tenants the following years. The interviews were done individually or in small groups depending on circumstances and staff availability. The employees were asked about their overall strategies, investments and approaches, company financial data, working roles, how everyday tasks were handled and the tenant relationships. The interviews lasted between one and three hours depending on staff work situation and participants' responses.

These interviews where conducted with local staff and management and were organized as open discussions. According to Gummesson (2004) a case study approach is suitable when a phenomenon is complex or knowledge is missing. For that reason a case study approach could be useful. A new method has been tested to identify administrative costs and to show what actions that can be counted as extra investments or as a part of the normal operation- and maintenance.

Two nearby large housing estate neighbourhoods comparable with regard to geographic location, construction year, social situation, demography and household- and apartment size was used as reference objects. These estates were well- functioning, together with the estates in Herrgården and were owned by the same housing company. This simplified the data collection process. Final interviews were to gain empirical information from the reference objects containing comparative data targeting management experience, operation- and maintenance costs and rental income. These interviews were conducted with the responsible managers together with frontline staff. Based on the Blomè (2009) example, operation costs associated with the neighbourhoods’ deprived social situation were separated from other costs. These additional expenses, assumed to be an extra social cost for the housing company to maintain and operate a none functioning neighbourhood. To find out the level of extra spent resources has the reference objects average operation- and maintenance costs put side by side with Herrgårdens costs and levels above the reference objects is assumed to be extra invested resources. The analysis compares two alternative strategic profitability options: First option (a) is new invested resources and the second option (b) is no new invested resources. Some assumptions are made and discussed. Calculations are made for 15 years and discounted at a real interest rate of 4 percent and figures are reported in SEK per apartment. As the calculations are forward looking and focusing on two management alternatives, the price paid for the estate will be disregarded as this is the same in both alternatives. A remaining value at the end of the 15 years period is estimated. Finally is also an alternative investment approach presented.

Used calculation formula =

Renewal work in large housing estates in Sweden

Over the years there have been several attempts to solve problems in the large housing estates produced in the million dwelling program between 1965-1975, such as building

improvements and social countermeasures. One example is the turn around projects back in the 1980s in Sweden, which in many ways resembles other projects around Western Europe. The Swedish government gave subsidies to municipal housing companies for renovation and rebuilding in socially disadvantaged areas. Of course this led to improved housing quality in some aspects, although it was a lack of local participation, and the cost was clearly higher than the economic and social outcome (Johansson et al 1988; Carlén and Cars 1990; Jensfelt 1991; Johansson 1992; Ytterberg 1992; Ericsson 1993). The idea behind these turn around projects was to rapidly increase the attractiveness and attract more resourceful households.

One social side effect was that unwanted households instead moved to other parts of the city transferring the problems to other neighbourhoods (Öresjö 1996).

The international recession in the early 1990s also hit the Swedish economy affecting the housing market in a negative way. These negative effects were particularly explicit in the large housing estates and led to increased unemployment, social exclusion and high vacancies. During those years many of these large housing estates neighbourhood such as Herrgården had received many new immigrants and many of those did not enter the labour market. This resulted in increased poverty and crime and led to further deterioration. In the second half of 1990s unemployment rates decreased which again changed the situation in the housing market to a shortage of housing in Swedish large housing metropolitan areas. This is also the case for areas characterized as disadvantage neighbourhoods (Andersson et. al. 2003), but there are significant socioeconomic, cultural and demographic differences between households living in large housing estates and those living in housing cooperatives or in single-family houses (Andersson et. al. 2003).

Back in the 1990s there was still an opportunity for housing companies to get

governmental subsidies for renewal projects in large housing estate areas. In the socially weak neighbourhoods in Stockholm that received governmental subsidies the primarily focus was on improving education, the built environment and peoples sense of security. The goal was to involve key actors and particularly tenants, but the participation was not very representative which reminded of the 1980s turn around projects. Some explanation could be found in language difficulties and the methods the housing companies used (Öresjö et. al. 2004). Identifying and selecting a poor neighbourhood may also lead to further stigmatization e.g. that the neighbourhood wasn’t treated as a normal area. Experiences show that projects that are carried out during a limited time are not likely to be successful because of distrust from the residents and the lack of long term perspectives (Öresjö et. al. 2004). The earlier negative experience from renewal projects in Sweden led to a political debate about suitable work methods and financial responsibility etc. This explains why the government today does not have any subsidies for these types of projects, even though it is now under discussion again because of the negative social progress in many large housing estates.

Employment seemed to be the most important parameter to improve living condition, the individual household’s economic situation and led to better access to the Swedish society in general. An obvious conflict however is when unemployment rates dropped, it might result in out-migration. This of course could be a success for an individual but not necessary for the large housing estates when better economic households leave and new weak households moves in stigmatising the social economic situation further. An interesting result is that regardless of which large housing estates in Sweden are discussed, the majority of tenants seemed to be rather satisfied although there is a common demand for improved security, playgrounds for children, higher quality of schools, maintenance of buildings and public and commercial services (Andersson et. al. 2005).

Presentation of the empirical data

This part of the paper contains five sections. The first section presents the rental income, second section shows the investment, operation- and maintenance costs and the third section contains the amount of invested social efforts. The last two sections contain data over operation costs associated with the neighbourhoods’ deprived social situation and these are separated from other costs. See more details about how data was gathered in the methodology. The results are presented in SEK per apartment.

Rental income

Based on the deprived situation in Herrgården and general bad living standards it is particularly remarkable that rental level are relatively high compared to other similar well functioning neighbourhoods. Two variables that may affect the level of rental income are unpaid rents and vacancies. These variables indicate problems, that are important to respond to, and are instead, in this section presented as costs. The reason behind this is to gather common variables that can indicate different problems. The staff argued that it is difficult to change the rent level.

“It is not possible to lower rents when we need all resources we can get to turn this poor neighbourhood situation around” (quoted from Manager).

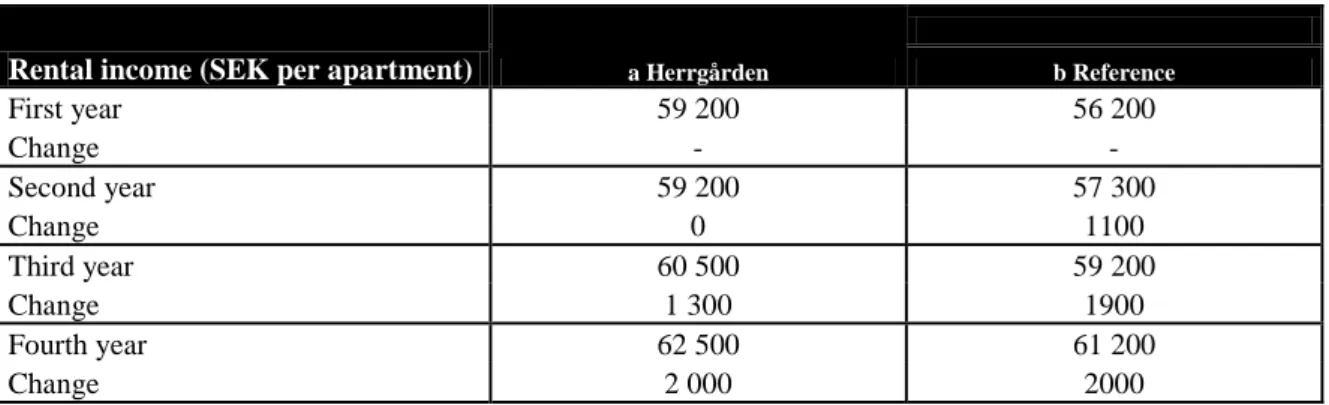

An important condition is that the estates have to carry their own costs, e.g. that rent-income cover all costs. The table below shows how rent levels have changed during the four year research period in comparison to the reference objects level.

Table 1: Rental income

Rental income (SEK per apartment) a Herrgården

b Reference First year 59 200 56 200 Change - - Second year 59 200 57 300 Change 0 1100 Third year 60 500 59 200 Change 1 300 1900 Fourth year 62 500 61 200 Change 2 000 2000

From the beginning rents were at a relatively high level and have not increased much since then.

Investment, operation- and maintenance costs

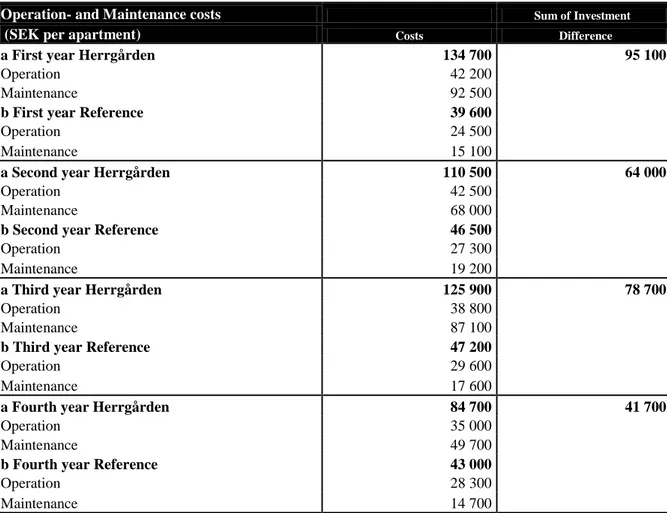

There have been a large amount of resources spent on extra activities in the local housing administration and maintenance measures were large. These measures include apartment repairs, technical maintenance, real estate and outdoor environmental improvements as well as extra organizational human resources.

The table below explains the operation- and maintenance costs separately to illustrate the amount of the total investments carried out. Due to neglected maintenance, a large

proportion of the total resources have been invested to improve the overall building standard. The figures presented, are compiled from company statements in addition to interviews with responsible managers.The cost difference is the housing company’s annual extra investments to change Herrgårdens deprived situation.

Table 2: Investment, operation- and maintenance costs

Operation- and Maintenance costs Sum of Investment

(SEK per apartment) Costs Difference

a First year Herrgården 134 700 95 100

Operation 42 200

Maintenance 92 500

b First year Reference 39 600

Operation 24 500

Maintenance 15 100

a Second year Herrgården 110 500 64 000

Operation 42 500

Maintenance 68 000

b Second year Reference 46 500

Operation 27 300

Maintenance 19 200

a Third year Herrgården 125 900 78 700

Operation 38 800

Maintenance 87 100

b Third year Reference 47 200

Operation 29 600

Maintenance 17 600

a Fourth year Herrgården 84 700 41 700

Operation 35 000

Maintenance 49 700

b Fourth year Reference 43 000

Operation 28 300

Maintenance 14 700

The cost difference illustrates annual invested amount of resources. Social efforts

Social efforts have been a fundamental strategy in order to create conditions for efficient real estate management and are included as part of the operation costs reported in the section above. Social efforts include neighbourhood related activities, sponsorship and networking with e.g. tenants, community organizations, schools, private businesses, other estate owners and non-profit organizations. Serious real estate managers use social efforts to reduce field problems, improve tenant relations and increase profitability. On the contrary a well-functioning neighbourhood needs less of this kind of extra resources.

More over, one current issue for the local administration in Herrgården was to take action against the overcrowded situation and to highlight the neighbourhood’s diverse needs. In this process, particular focus was given to activities for children and adolescents.

“These groups are large and are responsible for much of the

neighbourhood’s trouble” (quoted from Manager).

To create good relations between tenants and staff the real estate company has invested sustainable financial recourses to the local community. The level of efforts were unchanged during the first two years. However, as a consequence and adaptation to a more stable

real estate companies do not necessarily use some form of social efforts in their strategy. Comparable neighbourhoods (Reference) spend considerably fewer resources.

Table 3: Cost of social efforts

Social Projects a First and second year a Third and fourth year b Reference

(each apartment) Herrgården Herrgården Normal

Staff 1769 884 35

Projects 272 272 65

Sum 2041 1156 100

Social efforts during the first period. Extra operating costs

In addition to the social efforts extra operating costs are also included as a part of the operation costs (social extra cost). These costs are defined as extra costs caused by tenants misbehaviour and the current social situation. They are more common in socially deprived non-functioning neighbourhoods and are described in more detail below.

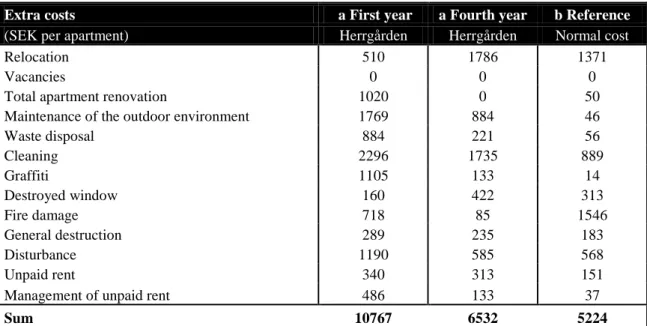

Table 4: Extra social costs in Herrgården

Extra costs a First year a Fourth year b Reference

(SEK per apartment) Herrgården Herrgården Normal cost

Relocation 510 1786 1371

Vacancies 0 0 0

Total apartment renovation 1020 0 50

Maintenance of the outdoor environment 1769 884 46

Waste disposal 884 221 56 Cleaning 2296 1735 889 Graffiti 1105 133 14 Destroyed window 160 422 313 Fire damage 718 85 1546 General destruction 289 235 183 Disturbance 1190 585 568 Unpaid rent 340 313 151

Management of unpaid rent 486 133 37

Sum 10767 6532 5224

The costs reduced from first year (a) to fourth year (a) by 39 percent approaching the reference costs (b) for similar areas.

The relocation cost includes expenses for the local administration to handle inspection and minor renovations. This cost has increased dramatically which can be explained by the fact that some of the tenants started a housing career (510-1786 (SEK) per apartment). A Project, to reduce overcrowding, was implemented and tenants were given an opportunity to move to other parts of the company's housing stock. This increase is natural but still a bit more than what can be considered as normal.

“We are trying to find solutions to reduce the problem with particular

overcrowded households. Our new estates in Herrgården have become a part of the housing companies letting system, which increases the opportunities for our tenants to reside elsewhere” (quoted from Manager).

Moreover, there are no vacancies caused by empty apartments due to a declining demand (0 (SEK) per apartment). In recent years the pressure on growing regions in Sweden has been substantial, especially in a big city as Malmö. That explains why the demand is constantly high and housing shortages rather have increased in recent years. Upcoming vacancies are mostly due to the short time period between tenants moving out to new tenant moving in.

“It is a huge pressure on the housing market in Malmö compared to previous

years when we used substantial resources just to keep apartments occupied”

(quoted from Manager).

Total apartment renovation costs have decreased much due to the increased number of non-functioning household. A few total renovations of destroyed apartments are very expensive for the management. This has dropped from a normal level (one percent of all apartments) to a zero-level (1020-0 (SEK) per apartment).

“There is a major mental illness among tenants in socially deprived areas. Some

are depressed and living in alienation, and others are satisfied. Even if this problem sometimes happens, is this occurrence of completely destroyed apartments caused by tenants unusual” (quoted from Manager).

These parameters seem to vary randomly and should not be used without reflection.

The maintenance cost of the outdoor environment has decreased much but remains on a high level compared to the reference cost (1769-884 (SEK) per apartment). A priority for the housing company has been to keep the outdoor environment clean from litter. In addition tenants have been involved in management work, e.g. that children and adolescents help staff with various chores after school.

“A key factor is to let local staff work actively, to involve, and also build good

relationships with the tenants and especially their children. A person who is actively involved obviously increases loyalty. A good relation reduces problems of e.g. vandalism and littering” (quoted from Manager).

The cost of garbage disposal has decreased and three explanations could be found; tenants enlarged responsibility, improved management routines and better technical solutions for the disposal of garbage (884-221 (SEK) per apartment). When the housing company started the renewal work the garbage disposal had too little capacity and was handled in a large container that was emptied once or twice each week.

“From the beginning we only blamed the tenants for not taking responsibility, but

after we created a relation to the tenants and built a new facility to handle garbage, the problems more or less disappeared” (quoted from Manager).

The cleaning cost contains the total contractor fee to clean the estates common areas. The cost has fallen to some extent but is still a bit from the reference price which indicates a need for a higher cleaning frequency (2296-1735 (SEK) per apartment).

“Cleaning has been adapted after each estates specific need. It is a sort of a

tenants’ behaviour indicator” (quoted from Manager).

In comparison, the local administration in principle had doubled the cleaning frequency, some week tripled, compared to the reference areas.

Graffiti can be very expensive for the local administration to manage. The cost to remove graffiti has decreased a lot and is moving towards the reference cost levels (1105-133 (SEK) per apartment). Both children and adolescents have been involved in the graffiti-process, a zero-tolerance level means that all graffiti is removed immediately. In the beginning the frontline staff spent several hours each day in order to remove graffiti.

“Children and adolescents are important to involve in this process. Otherwise, all

hours spent on cleaning walls from graffiti would be pointless. It took several hours each day compared to today’s situation, a few hours each week” (quoted

from Manager).

The cost of destroyed windows has increased and one explanation is poor management decisions (160-422 (SEK) per apartment). The use of plastic windows turned out to be a bad idea because they were scratched and became ugly in direct sunlight. Tempered windows were installed after the frontline staffs tested ordinary windows. It may be added that the divergence is not significantly large in comparison to the reference cost.

“Many broken windows are caused by accidents, bad technical solution, and the

overcrowded situation. Some windows are destroyed with intention but I believe that most of today’s damaged windows can be explained as unintentional”

(quoted from Manager).

A slight decline of the general destruction cost has been quoted (289-235 (SEK) per

apartment). It includes costs to repair general sabotage, various carpentry damages, destroyed locks and lightning etc. The cost of general destruction approaching the reference cost (183 (SEK) per apartment.

“The strategy is to repair immediately and not let the estates deteriorate due to

vandalism” (quoted from Manager).

Subsequently cost of fire damage has decreased (718-85 (SEK) per apartment). One reason could be that tenants pay more attention to what is happening around the neighbourhood. The reference costs are significantly higher and if it depends only on a single trend or other things are difficult to determine. The housing managers’ observation strengthens the hypothesis that the extra efforts to change situations really makes a difference.

"When riots were spread across nearby neighbourhoods our tenants have

defended the estates and thrown out unauthorized persons” (quoted from

Manager).

Unlike the situation in the beginning of the process this evidence suggests that tenants started to feel a great loyalty to the real estate company. This type of parameter alike the total

apartment renovation cost seems to vary randomly and should as well not be used without reflection.

The disturbance cost has decreased from a high level to a normal level (1190-585 (SEK) per apartment). This includes both contractor costs (responsible evenings, nights and weekends) and working time local staff administration use on cases. Time spent on disturbances has dropped from 20 hours to 4 hours each week.

“We spend far less time on disturbances and repeated home visits help us handle

problems before they become a real issue” (quoted from Manager).

Furthermore the expenses of unpaid rent lie on a virtually unchanged level (340-313 (SEK) per apartment). The majority of the tenants are dependent on various types of governmental social support in order to pay rent.

"Although the willingness to pay has improved, many lack resources and are still

living on a minimum level (quoted from Manager).

In addition managing unpaid rent includes administration of around tenants’ personal payment files. When these special cases are reduced, naturally these costs will drop off (486-133 (SEK) per apartment).

“The time spent on payment issues has changed and we think it could have

something to do with the improved tenant relationship” (quoted from Manager).

Previously the tenants were anonymous for the local administrators and they only had a huge number of addresses which made it difficult for personnel to identify whom actually lived in the apartments. Finally in order to refine estimations has fire- and total apartment renovation costs excluded in this alternative operation calculation. These parameters seem to vary randomly and could have a significant impact on calculation in relation to other variables. Table 5: Alternative social extra costs in Herrgården

Extra costs a First year a Fourth year b Reference

(SEK per apartment) Herrgården Herrgården Normal cost

Relocation 510 1786 1371

Vacancies 0 0 0

Maintenance of the outdoor environment 1769 884 46

Waste disposal 884 221 56 Cleaning 2296 1735 889 Graffiti 1105 133 14 Damaged window 160 422 313 General destruction 289 235 183 Disturbance 1190 585 568 Unpaid rent 340 313 151

Management of unpaid rent 486 133 37

Sum 9029 6447 3628

The costs reduce from first year (a) to fourth year (a) by 28 percent approaching the reference costs (b) for similar areas.

Fire damage and total apartment renovation recurs occasionally and is very expensive to correct. We see that even if fire cost and total apartment renovation cost is removed from the table above are the change in table 1 and table 2 calculations similar.

A possible assumption after 4 years of extra efforts are normalized operation costs. The difference in table 4 and table 5 between the initial first year costs compared with the

reference cost is 5543 SEK respectively 5401 SEK per apartment. Therefore, an average cost saving ca. 5500 SEK is a suspected reasonable level. The negative progression for relocation- and broken window costs are confirmed as natural or as incorrect management decisions. Go to the methodology for more details about the different variables and the used calculation method.

Calculation of profitability

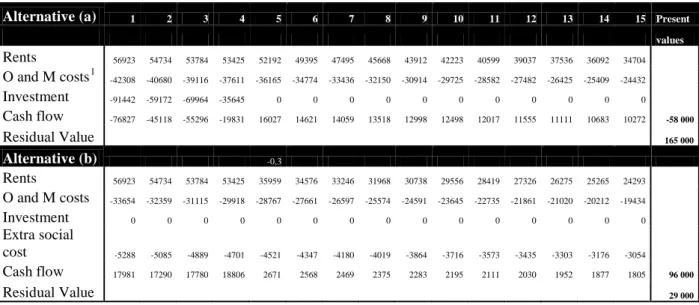

The housing company’s strategy in Herrgården is analyzed on the basis of potential investments, rental income, maintenance- and operating costs and residual value. The analysis examines two alternative approaches and also discusses a third alternative investment option. Calculations are made over 15 years and discounted at a real interest rate of 4 percent and figures are reported in SEK per apartment. As the calculations are forward looking and focusing on two management alternatives, the price paid for the estate will be disregarded as this is the same in both alternatives. A remaining value at the end of the 15 years period is estimated. Presented below are two different scenarios; one real (a) and one fictitious (b).

a. New invested resources. This strategy is a real scenario based on the actual efforts invested by the housing company.

b. No new invested resources. This example is based on fictitious situation with no new investments and operation- and maintenance costs kept at a minimum level.

Economic scenarios

The real resources put in Herrgården´s estates (a) are calculated from the first four years efforts to restore and improve neglected operation- and maintenance (reported in Table 2). The other strategy, alternative (b) does not include any new investments. The total

investment for alternative (a) is -256 223 SEK compared with 0 (b) per apartment. To provide such extensive resources for a limited time is a parallel approach to the Swedish turn around projects in large housing estates back in 1980 - and 90's. The difference is that these earlier projects were governmental-subsidized unlike this case only supported by the municipal housing company. However is the approach in (a) to continuing to fulfil future needs and not only carry out a limited time project. The similarity is extra economic resources put in the large housing estates for a short period of time which could end up in related problems to the 1980- and 90s projects e.g. lack of tenant participation, unwanted household instead moved to other parts of the city transferring the problems to other neighbourhoods and that limited time projects led to resident distrust and lack of long term perspective. European cities have a large number of deprived large housing estates and many of these are in need of new investments. Unfortunately a common worldwide alternative approach is to either choose pioneer large scale projects or no extra investments at all. Another possible investment strategy beyond the ones presented above to reduce negative side effects is adapted resources over several years instead of large scale projects trying to change situation over a few years. Experience from socially weak well-functioning large housing estates in Sweden indicates positive effects e.g. that extra social projects are continuously carried out to reduce field problems (Blomé 2009).

This strategy however requires fairly well maintained estates which was not the case in Herrgården.

Rent levels are calculated from the first four years (reported in Table 1) and then assumed to remain constant in (a) compared with (b), which instead expects to drop 30 percent after four years. Swedish rents are negotiated through the tenants' association and municipal housing companies are normative for other private companies. In addition, tenants' association is able to negotiate down rent levels, which is likely to occur in Herrgården, if the operation- and maintenance quality is not consistent with reasonable level. A large media and public interest gives extra attention to this case which is seldom a reality for most of these types of deprived neighbourhoods. The total rent income for alternative (a) is 687 719 SEK compared with (b) 546 488SEK (per apartment). Neither of these calculations include vacancies and that is not likely to happen in a near future because of the overheated local housing market. However, housing market is more sensitive to cyclical fluctuations in socially deprived estates compared with more socially stable neighbourhoods. The reason behind the rents is assumed to be constant after the fourth year in alternative (a) is because new local Swedish rent regulations contributes to preserved- or lower rents in residential areas located far from city centre or in less attractive parts of the city.

Operation- and maintenance costs for alternative (a) is calculated based on reference objects average costs (reported in Table 2) which is a reasonable level to maintain a high quality real estate management ( -44 000 SEK per apartment each year). The total operation- and

maintenance costs for this option is -489 209SEK (per apartment). Although costs vary from year to year depending on external or local conditions, is basic management needs constant over time e.g. resources needed to maintain housing quality etc. Operation and maintenance cost for alternative (b) is -389 144 SEK per apartment (-35 000 SEK per apartment each year). In this option management costs are kept at a minimum level barely keeping estates from falling a part e.g. only necessary operation- and urgent maintenance. In addition this strategy implies no planned maintenance, also ignoring future needs which could be devastating for estates condition as well as the tenants leaving environment.

Extra social cost is defined as extra costs caused by tenants misbehaviour and the current social situation. This cost was assumed to drop as a consequence of the invested resources in alternative (a) after the fourth year. Additionally following cost variables have been identified; relocation, vacancies, total apartment renovation, maintenance of the outdoor environment, waste disposal, cleaning, graffiti, destroyed window, fire damage, general destruction, disturbance, unpaid rent, management of unpaid rent. Variables as e.g. fire damage and total apartment renovation vary randomly and should not be used without reflection. Other presented variables turned out to be more suitable even thought incorrect operating management decisions could end up in an opposite effect. Due to lack of preventive measures in (b) is this cost -5 500 SEK (per apartment each year) which is about one month's rent for an average apartment. Poorly functioning estates have an extra social cost and active management is needed to retain estimated cost reduction depending on housing company's future action. In the beginning gave the municipality the municipality housing company a clear mandate to start and continue Herrgårdens renewal process. That indicates a long term commitment and was important for the housing company’s choice of strategy. The scale of the social project is based on first four year efforts (Table 3) which is not much in proportion to the savings above 5 865 SEK (per apartment for the entire period). In addition is this figure included in above presented investments and identify the total amount of social effort from the physical building improvements.

The residual value is calculated from a direct rate of return of 6 percent. Furthermore, are the residual value calculated according to praxis and clearly shows a major difference between alternative (a) 165 000 SEK (per apartment) and alternative (b) 29 000 SEK (per

apartment). Option (b) gave a larger cash flow at the end of the investment period 96 000 (per apartment) than option (a) -58 000 (per apartment) and if the rent levels is maintained at current levels and not dropped could this even improve regard to only cash flow. However is the residual value estimated to be low in alternative (b) due to lack of investments, lower rents, neglected estates and poor cash flow at the end of the financial period unlike option (a), which is valued much higher. In a well functioning market should option (b) disqualify itself but there are unfortunately several examples in Sweden when large housing estates have been market valued above reasonable profitability value and Herrgården is an obvious example of that. It is difficult to justify (a) from a strictly business perspective unless there are other aspects to take into account because no private landlord will defend an economic investment with negative figures, a poor cash flow and a low residual value. Although (b) could be profitable initially is that alternative in contrast to (a) very sensitive to changes in the local housing market and also to rent reductions.

Finally two strategic options have been compared in this analysis based on collected empirical data; (a) new invested resources and, (b) no new invested resources. In addition are these two different investment alternatives summarized in the table below.

Table 6: Alternative (a) and alternative (b)

Alternative (a) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Present

values Rents 56923 54734 53784 53425 52192 49395 47495 45668 43912 42223 40599 39037 37536 36092 34704 O and M costs1 -42308 -40680 -39116 -37611 -36165 -34774 -33436 -32150 -30914 -29725 -28582 -27482 -26425 -25409 -24432 Investment -91442 -59172 -69964 -35645 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Cash flow -76827 -45118 -55296 -19831 16027 14621 14059 13518 12998 12498 12017 11555 11111 10683 10272 -58 000 Residual Value 165 000 Alternative (b) -0,3 Rents 56923 54734 53784 53425 35959 34576 33246 31968 30738 29556 28419 27326 26275 25265 24293 O and M costs -33654 -32359 -31115 -29918 -28767 -27661 -26597 -25574 -24591 -23645 -22735 -21861 -21020 -20212 -19434 Investment 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Extra social cost -5288 -5085 -4889 -4701 -4521 -4347 -4180 -4019 -3864 -3716 -3573 -3435 -3303 -3176 -3054 Cash flow 17981 17290 17780 18806 2671 2568 2469 2375 2283 2195 2111 2030 1952 1877 1805 96 000 Residual Value 29 000

Presented values for alternative (a) cash flow is -58 000 SEK and residual value 165 000 SEK. Alternative (b) cash flow is 96 000 SEK and residual value 29 000 SEK (per apartment).

This type of investment analysis gives a balanced picture of how difficult it is to motivate large-scale renewal projects from a business profitability perspective without governmental subsidies. One issue that is not analyzed in this paper is the socio-economic perspective. Some of these variables are e.g. frequency of police- and fire department operations and crime rate. Furthermore are number of sick-listed people, children and adolescents school performance and labour market changes difficult to measure in the short term and also dependent on several aspects such as structural policy actions and not just related to local neighbourhood related efforts.

1

A third alternative strategy is to reduce initial investments while management continuing to carry out social projects. This alternative strategy allow option (a) to be more profitable and also more suitable for a private landlord instead as now only encouraged by the municipality to create a ideal local renewal example to inspire other landlords and policy makers.

Furthermore could the amount of investment be allocated over several years to minimize negative side effects e.g. unwanted household instead moved to other parts of the city transferring the problems to other neighbourhoods and also that limited time projects led to resident distrust and lack of long term perspective.

This alternative can be successful if the renewal strategy is sustainable, allows tenant participation and not only focusing on a limit project time. In addition, is the housing company’s challenge (a) to continue to engage/motivate local frontline staff and to avoid estates from turn into slum again after the initial four-year investment period.

Conclusion

This papers aim is to identify costs affected by poor management particularly responsive to neighbourhoods’ social condition and also to discuss profitability and different investment strategies. The following variables have been identified as responsive to management strategies; relocation, vacancies, total apartment renovation, maintenance of the outdoor environment, waste disposal, cleaning, graffiti, destroyed window, fire damage, general destruction, disturbance, unpaid rent, management of unpaid rent. Two investment options were presented and analyzed from a 15 years forward looking calculation discounted at a real interest rate of 4 percent.

a. New invested resources. This strategy is a real scenario based on the actual efforts invested by the housing company.

b. No new invested resources. This example is based on fictitious situation with no new investments and operation- and maintenance costs kept at a minimum level.

None of these two options were considered to be profitable from a business economic perspective. Alternative (a) could possible be justified by e.g. the socio-economic aspects not further analyzed in detail in this paper. Alternative (a) gave a better residual value (165 000 per apartment) than (b) (29 000 per apartment). However, gave (b) a better cash flow (96 000 per apartment) than (a) (-58 000 per apartment). Given alternative (a) presented values is this type of large scale investments projects not interesting for private landlords without any governmental subsidies. A third alternative strategy is discussed and implies less economic efforts than alternative (a) but keeps a clear focus on social projects adapted throughout the hole investment period. In addition are social projects cheap to carry out on the local field compared to physical building improvements. This alternative strategy could also reduce undesirable effects such as lack of tenant participation, unwanted household instead moved to other parts of the city transferring the problems to other neighbourhoods and that limited time projects led to resident distrust and lack of long term perspective.

Finally, experience from this renewal project show that it is important to keep a consistent policy in the company after the investment period to avoid estates from turning into slum again. This research project will continue to focus on profitability strategies carried out by the housing company in socially disadvantage large housing estates with particular focus on the driving forces of alternative strategies.

References

Andersson, Roger (2002) Boendesegregation och etniska hierarkier (Housing Segregation and Ethnic Hierarchies). Det slutna folkhemmet – om etniska klyftor och blågul självbild, Stockholm.

Andersson, R, Molina, I, Öresjö, E, Petersson, L, Siwertsson, C (2003) Large housing estates in Sweden. Overview of develoments and problems in Jönköping and Stockholm. Ulrecht University.

Andersson, R, Öresjö, E, Petersson, L, Holmqvist, E, Siwertsson, C, Solid, D (2005) Large housing estates in Stockholm and Jönköping, Sweden. Opinion of residents on recent development. Ulrecht University.

Blomè, G (2006) Kundnära organisation och serviceutveckling i bostadsföretag. Kungliga tekniska högskolan. Blomé. G (2009) Lönsamhetsanalys av Stena Fastigheter förvaltningsorganisation. Kungliga Tekniska Högskolan

Carlèn, G, Cars, G (1990) Förnyelse av storskaliga bostadsområden. En studie av effekter och effektivitet. Byggforskningsrådet.

Johansson, I, mattson, B, Olsson, S (1988) Totalförnyelse – Turn around – av ett 60-talsområde. Chalmers Tekniska Högskola.

Ericsson, O (1993) Evakuering- och inflyttningsprocessen vid ombyggnaden av saltskog i Södertälje. Statens institution för byggnadsforskning.

Jensfelt, C (1991) Förbättringar av bostadsområden. Formators omvandlingar i miljonprogrammet. En tvärvetenskaplig utvärdering. Byggforskningsrådet.

Johansson, I (1992) Effekter av förnyelse i storskaliga bostadsområden. Göteborgs universitet. Kulturgeografiska institutionen.

Malmö City Office (2008) Områdesfakta Herrgården. Malmö. Nordström, L(1984[1938]). Lortsverige. Sundsvall. Tidsspegeln. Ramberg, R (2000) Välfärdsbygge 1850-2000. SABO.

Van Beckhoven, E (2006) Decline and Regeneration. Policy respnses to processes of change in post-WW11 urban neighbourhoods. Netherlands Geographical Studies.

Ytterberg, C (1992) Ombyggnad i Saltskog. Statens institut för byggnadsforskning.

Öresjö, E (1996) Att vända utvecklingen. Kommenterad genomgång av aktuell forskning om segregation i boendet. SABO.

Öresjö, E, Andersson, R, Holmqvist, E, Petersson, L, Siwertsson, C (2004) Large housing estates in Sweden. Policies and practices. Ulrecht University.