Thesis in Nursing Malmö University

61-90 hp Faculty of Health and Society

Bachelor Programme in Nursing 205 06 Malmö

January 2021

AN EXPLORATION OF HOW

PERSONS WITH PSYCHIATRIC

DIAGNOSES EXPERIENCE CARE

AS A PATIENT WITHIN GENERAL

HEALTH CARE

A LITERATURE REVIEW

STEPHANIE BUENAFLOR

AN EXPLORATION OF HOW

PERSONS WITH PSYCHIATRIC

DIAGNOSES EXPERIENCE CARE

AS A PATIENT WITHIN GENERAL

HEALTH CARE

A LITERATURE REVIEW

STEPHANIE BUENAFLOR

CHARITA SONGCOME BERGLUND

Buenaflor S & Songcome Berglund C. An exploration of how persons with psychiatric diagnoses experience care as a patient within general health care. A literature review. Degree project in nursing 15 credit points. Malmö University: Faculty of Health and Society, Department of Health Care Science, 2020.

Background: Statistics reveal that approximately 10.7% of the global populations

have mental health disorders. In Sweden, 14% of persons with psychiatric diagnoses have had direct contact with a registered nurse. Based on studies, it is evident that registered nurses experience lack knowledge regarding psychiatric diagnoses, which negatively affect their ability to provide person-centered care. Furthermore, there is also a desire among registered nurses for increased

knowledge regarding psychiatric diagnoses. The aim of this study was to explore how persons with psychiatric diagnoses experience care as a patient within general health care. Method: A literature review based on qualitative research results was performed and data was analyzed through a content analytical technique. It emerged three themes in the results: (1) Feeling subjected to prejudice, (2) Variations in the quality of support, and (3) Impression of the environment. The themes are presented with two sub-themes each. The

participants’ experiences were mostly negative, grounded in discrimination, lack of support and knowledge from caregivers, and stressful surroundings.

Conclusion: This study highlights persons with psychiatric diagnoses experiences

within the general health care setting. Results can give an insight on how a registered nurse can provide a better person-centered.

Keywords: general health care, mental health, nursing, patient experience,

EN UTFORSKNING AV HUR

PERSONER MED PSYKIATRISKA

DIAGNOSER UPPLEVER VÅRD

SOM PATIENT INOM ALLMÄN

HÄLSO- OCH SJUKVÅRD

EN LITTERATURSTUDIE

STEPHANIE BUENAFLOR

CHARITA SONGCOME BERGLUND

Buenaflor S & Songcome Berglund C. En utforskning av hur personer med psykiatriska diagnoser upplever vård som patient inom allmän hälso- och sjukvård. En litteraturstudie. Examensarbete i omvårdnad 15 högskolepoäng. Malmö universitet: Fakulteten för hälsa och samhälle, institutionen för vårdvetenskap, 2020.

Bakgrund: Statistik visar att ungefär 10,7% av världens befolkning har en

psykiatrisk diagnos. I Sverige så har 14% av personer med psykiatriska diagnoser haft direktkontakt med en grundutbildad sjuksköterska. Tidigare forskning visar att det finns en upplevd kunskapsbrist bland grundutbildade sjuksköterskor angående psykiatriska diagnoser, vilket påverkar deras förmåga att ge

personcentrerad vård negativt. Forskning visar även på att det finns en önskan för utökad kunskap om psykiatriska diagnoser bland grundutbildade sjuksköterskor.

Syfte: Att utforska hur personer med psykiatriska diagnoser upplever vård som

patient inom allmän hälso-och sjukvård. Metod: En litteraturstudie baserade på kvalitativa forskningsresultat utfördes, och data analyserades med en

innehållsanalytisk teknik. I resultatet framkom tre teman: (1) Känsla av att vara utsatt för fördomar, (2) Variationer i kvalitén av stöd, och (3) Intryck av

omgivningen. Teman presenteras med två underteman var. Upplevelserna var mestadels negativa baserade på diskriminering, brist på stöd och förståelse, samt stressig miljö. Konklusion: Den här litteraturstudien belyser personer med psykiatriska diagnosers upplevelse av vård. Resultatet kan ge en inblick i hur en grundutbildad sjuksköterska kan förse en bättre personcentrerad vård.

Nyckelord: allmän sjukvård, omvårdnad, patientupplevelse, person-centrerad vård,

TABLE OF CONTENT

INTRODUCTION ... 1

BACKGROUND ... 1

Mental Health and Psychiatric Diagnosis ... 2

Term used for this study ... 2

Nursing care ... 2

The responsible nurse ... 3

Person-centered care ... 3

PROBLEM FORMULATION ... 4

AIM ... 4

METHOD ... 4

Data collection process ... 4

POR-model ... 4 Inclusion criteria ... 5 Exclusion criteria ... 5 Database search ... 5 Quality review ... 6 Data analysis ... 6 RESULT ... 7

Feeling subjected to prejudice ... 8

Actions of discrimination ... 8

Reluctance of opening-up ... 9

Variations in quality of support ... 9

Manifestations of support or the lack thereof ... 10

Perceived competence of the caregivers ... 11

Impressions of the environment ... 12

A stressed surrounding ... 12

Feelings of discomfort ... 12

DISCUSSION ... 13

Method discussion ... 13

Data collection process ... 13

Quality review ... 14

Data analysis ... 15

Result discussion ... 15

Feeling subjected to prejudice ... 16

Variations in quality of support ... 17

Impressions of the environment ... 18

SUGGESTION OF IMPROVEMENT AND QUALITY DEVELOPMENT ... 19 REFERENCES ... 21 APPENDIX ... 25

1

INTRODUCTION

In order to obtain a deeper understanding and knowledge, and to enhance the registered nurse’s ability to give person-centered care, this study will focus on persons with psychiatric diagnoses and their experiences of care within general health care. When working as a registered nurse, the workplace could be of importance relating to what specific qualities that might develop. A registered nurse in an orthopedic ward is more likely to possess certain knowledge about fractures, while a nurse in a psychiatric ward may be more prepared in assisting persons who have psychiatric diagnoses. Regardless of the workplace, it is not uncommon for a registered nurse to meet and tend to persons who have multiple diagnoses, such as psychiatric and medical. Symptoms such as tachycardia, headaches, tremor, hyperhidrosis, hyperventilation, abdominal and/or chest pain, can be challenging for both the registered nurse and patients to distinguish if it is due to a medical problem or generated of the psychiatric diagnoses. This could cause a problem when a registered nurse does not know what appropriate measures should be taken to provide person-centered care for those patients. Through the authors’ own experiences, some registered nurses seem insecure, anxious, or judgmental when it comes to encounter patients who, except for medical needs, also have specific psychiatric needs. These behaviors could negatively affect the way the registered nurses give care. Therefore, this study is going to explore the experiences of the care given in non-psychiatric wards, from the perspective of persons with psychiatric diagnoses. Having a deeper

understanding of the patient’s experiences, and integrating that knowledge while providing nursing care, could lead to more person-centered care which is one of the registered nurse’s core competencies.

BACKGROUND

According to Ritchie & Roser (2018), 10.7% of the global population lives with a mental health disorder. During 2019 the most common reason for hospitalization among people aged between 15 to 44 years old in Sweden was due to psychiatric disorders (National Board of Health and Welfare 2020). Statistics presented in a project about mental health called “Uppdrag Psykisk Hälsa”, which is a

collaboration between the Swedish government and the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions, reveals that approximately 14% of persons with psychiatric diagnoses have had direct contact with a registered nurse (RN) within the public sector in 2019 (Wieselgren & Malm 2020). A study made at an

emergency department by Richmond et al. (2007) showed that 45% of all who sought medical assistance due to a minor injury, had a history, of or a current psychiatric diagnosis.

A study made in general hospital settings by Mavundla (2000) concluded that there exist stereotypes and stigma towards patients with psychiatric diagnoses among RNs. Furthermore, the RNs admitted that they had feelings of frustration and fear toward these patients and that it affected their way of giving nursing care (ibid.). Similarly, Lord et al. (2010) suggested that there is a lower quality of preventive medical care and medical screening for persons with psychiatric diagnoses. In another study, Arvaniti et al. (2008) claimed that psychiatric staff

2

who are more familiar with psychiatric patients have more positive attitudes towards them, compared to RNs with less psychiatric exposure, and further suggested that education might reduce stigmatizing views. Shirilee et al. (2006) had similar results where lack of knowledge seemed to play a big role in RNs’ negative approach and nursing care.

Mental Health and Psychiatric Diagnosis

In a study where they attempted to clarify the meaning of mental health, Manwell et al. (2015) concluded that there is a current lack of consensus regarding the core definition of mental health. However, the study found that there were significant subcomponents of the definitions involving factors relating to the individual’s ability to interact with society and cope with changes in life. Crucial factors such as autonomy, freedom to choose and regulate their own lifestyle, and to be able to contribute to a society where vital components for the participants to define their mental health status (ibid). Furthermore, mental health refers to a state of well-being, the emotions, how the person views themselves, and how they interact with others (ibid.).

The World Health Organization (WHO) uses the term mental disorders and defines it as an umbrella term describing “a clinically recognizable set of

symptoms or behavior associated in most cases with distress and with interference with personal functions” (WHO 1992, p. 5). Psychiatric diagnoses can be based on diagnostic manuals like DSM-5 or ICD-10. The concept includes conditions like depression, personality disorder, anxiety disorder, eating disorder, and psychotic disorder (American Psychiatric Association 2013; WHO 2015a). To summarize the above, mental health is a subjective reality that all humans can experience, whereas psychiatric diagnoses are observable manifestations that must meet certain criteria. Despite being two different concepts, persons with

psychiatric diagnoses could experience mental health illness due to their diagnosis as well as mental health.

Term used for this study

A term like mental health illness is more subjective and an experience of well-being, hence being a broader and vaguer concept. Therefore, this study will limit the focus to persons who have a psychiatric diagnosis. As the terms mental

diagnosis and psychiatric diagnosis are frequently used interchangeably, this

study will mention these conditions as psychiatric diagnoses to prevent confusion and make it consistent throughout the text.

Nursing care

Watson (1985, p. 7) defines nursing as a “caring process that helps the person attain (or maintain) health or die a peaceful death”, where the RN promotes and restores health as well as prevents illness. Having a humanistic caring approach, Watson (1985) discusses that nursing is about caring, not curing, and stresses the importance of seeing and looking after all the aspects of the person to reach the aim of nursing. This can only happen if the RN is fully present, as each human possesses an inner center that only can be reached through a connection between the persons involved (Watson 1988). Through that connection, the RN’s intention becomes visible and enables the patient to feel dignified or not (ibid.). Similarly, in a study that focuses on fundamental care, Kitson et al. (2014) stresses that nursing care must be provided while integrating a humanistic holistic perspective

3

and highlights the importance of the RN’s genuine commitment to the patient. This means that the RN has an important role for the patients’ well-being when meeting their needs of safety, prevention, medication, education, support,

communication, respiration, eating, drinking, dressing, elimination, and personal hygiene (ibid.).

The responsible nurse

Specialized nurses who possess the expertise of working with persons with psychiatric diagnoses are called mental health nurses (MHN), and to be qualified they need a specialist education in mental health nursing (WHO 2003). Except doing the generalist nursing, the MHN’s role is to provide support to the individual and/or their family in the adaptation to and coping with the manifestations of mental health illness (ibid.). Even though the RN may not possess the same theoretical or practical knowledge about psychiatric diagnoses, they still need to strive towards providing person-centered nursing care while attending to patients with psychiatric diagnoses.

Person-centered care

The Swedish Society of Nursing (SSN) argues that person-centered care is one of the RN’s core competencies, along with teamwork and collaboration, evidence-based practice, quality improvement, safety, and informatics (SSN 2017). Person-centered care can be defined as:

“... an approach to care that consciously adopts the perspectives of

individuals, families and communities, and sees them as participants as well as beneficiaries of trusted health systems that respond to their needs and preferences in humane and holistic ways” (WHO 2015b, p. 10-11).

Similarly, Cronenwett et. al. (2007) talks about person-centered care as an attitude based on the RN’s knowledge and skills which contribute towards a more specific nursing care to the patients. A professional partnership should be established between the RN and the patient, and this can be accomplished by respecting and understanding the patient (ibid.). Genuine communication is a key component in gathering understanding for the patient, both through asking and listening. By understanding the patient’s value and preferences, and recognizing what is said beyond the spoken words, the RN shows their respect and a genuine desire to help and support the patient, hence being able to give person-centered care (ibid.). As previously mentioned, teamwork is one of the core competencies of a RN. Regardless of the workplace, there are other professionals and relatives involved in the patient's care, whom the RN must collaborate with. One of the roles of being a RN is to guide the patient through the network of different health care professionals. Therefore, in order to assist the patients in the best way, the RN must understand the different roles each team member has, show respect for specific expertise each member has and understand the value of teamwork and its effect on the patient’s health outcome (SSN 2017; Cronenwett 2007).

4

PROBLEM FORMULATION

Data reveals that psychiatric disorders are common diagnoses among the world population and that the chances are high that persons who seek non-psychiatric care have a psychiatric diagnosis. This means that the RN, regardless of where they work, will meet patients who have a psychiatric diagnosis. Unfamiliarity and lack of knowledge with psychiatric conditions among RNs may lead to

stereotypes, stigma, and fear towards persons with psychiatric diagnoses, which in turn might lead to a negative influence on the outcome of nursing care. In order to avoid the risk of mistreating a patient and giving deficient fundamental and holistic nursing care, it is of importance for the RN in a non-psychiatric ward to become more familiar with psychiatric diagnoses. The knowledge obtained by highlighting the patients’ experiences in reflection with nursing care theories, could lead to a deeper understanding in how to give person-centered care and meet the needs of persons with psychiatric diagnoses.

AIM

The aim of this study was to explore how persons with psychiatric diagnoses experience care as a patient within general health care.

METHOD

In order to get an overview of the patients’ perspectives on how they experience care within general health care, a literature review of scientific articles’ results was conducted where existing data on the subject was compiled (Henricson & Billhult 2017). As experiences are subjective, the results of qualitative articles were used to capture the phenomena (ibid.).

Data collection process

The chosen databases to search for relevant articles were CINAHL, PubMed, and PsycINFO. CINAHL (Current Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature) was chosen considering its focus on nursing care (Willman et al. 2016). PubMed was selected due to its collection of medicine and nursing among other sciences (ibid.). Lastly, PsycINFO was chosen due to its selection of articles within psychology and psychiatry (ibid.).

POR-model

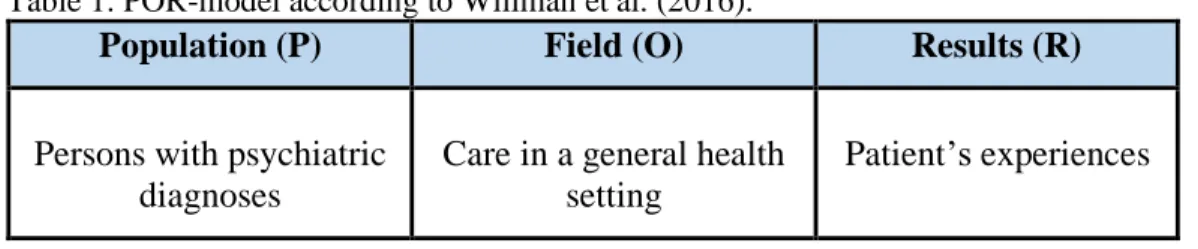

By using the POR-model, three areas (population, field, and outcome) were selected to facilitate and specify the search of relevant data (Willman et al. 2016). The first area, population (P), became persons with psychiatric diagnoses. The second area, field (O), was the care, given in a general health care setting. The third area, outcome (R), landed in the patient’s experiences (Table 1, p. 5).

5

Table 1. POR-model according to Willman et al. (2016).

Population (P) Field (O) Results (R)

Persons with psychiatric diagnoses

Care in a general health setting

Patient’s experiences

Inclusion criteria

Articles were included if they were: • Peer-reviewed.

• Written in English or Swedish, to be able to read and understand.

• Based on adults with psychiatric diagnoses, regardless of gender, to match an adult population who can give a detailed description of experiences.

Exclusion criteria

Articles were excluded if:

• They focused on care within a psychiatric ward, due to this study’s chosen field specifically involving non-psychiatric health care.

• They focused on care given from specialized psychiatric health care professionals, as the results aim to be applicable on registered nurses.

• The perspective is based by proxy, considering the focus is the patient’s experience.

Database search

After specifying three areas according to Willman et al.’s (2016) POR-model, the areas were condensed into three keywords. The population, persons with

psychiatric diagnoses, became the keyword psychiatric diagnoses. The field, care in general health care, was compressed to the keyword general health setting. The outcome area, patient’s experiences, was already as condensed as it could be, so the last keyword became patient’s experiences. In order to widen the search and to capture all articles that could possibly cover the aim of this study, the next step was to assemble the synonyms and the variations of each keyword. Furthermore, suitable subject terms related to the keywords were identified in each database. The assembled synonyms and variations (search terms) were then divided into three search blocs. The assembled search terms in each bloc were then searched together with the Boolean term OR. In order to combine the three blocs, a Boolean search with the term AND was made. Asterisks (*) were added on certain search terms to include different suffixes. The same keywords and blocs were used in CINAHL, PubMed, and PsycINFO, although the used subject term has differed depending on the database. The selection process of relevant articles on PubMed and PsycINFO can be seen in table 2, p. 6. Due to no relevant findings in

CINAHL, this database was excluded. For a full description of the search blocs and search results, see appendix 1.

6 Table 2. Selection process.

Database Search results Read titles Read abstract Read articles Quality review Chosen articles PsycINFO 403 403 151 12 7 5 PubMed 519 519 163 15 12 7 Total 922 922 314 27 18 12 Quality review

The Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services’ (SBU) review template for qualitative studies was used to assess the quality of the articles (SBU 2017). A quality review of 15 articles was

independently conducted to ensure reliability. After the separate reviews, a joint evaluation was made to discuss and argue the articles’ accuracy. The SBU’s (2017) criteria for the assessment of the scientific quality were used to decide the high, medium, or low quality of each article. According to these criteria, an article with high quality had to meet a few crucial points, for example, a well-defined aim, a clear presentation, a well-described method, and a logical result (ibid.). Twelve articles passed this quality review process, whereas eight met all the criteria for high quality and four reached medium quality (Appendix 2).

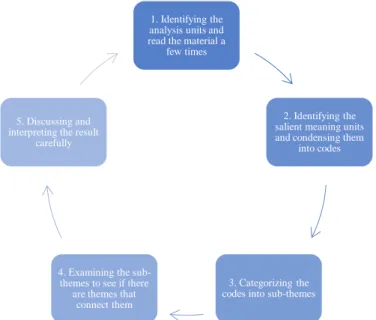

Data analysis

To analyze the results from the scientific articles, a qualitative content analysis method was used for this study. According to Danielson (2017) content analysis is a technique that, through a systematic process, enables the researcher to capture and identify patterns in the gathered data. The process includes (1) identifying the analysis units and read the material a few times, (2) identifying the salient

meaning units and condensing them into codes, (3) categorizing the codes into sub-themes, (4) examining the sub-themes to see if there are themes that connect them, and (5) discussing and interpreting the result carefully (Danielson 2017). The content analysis process is presented in figure 1 (p. 7). According to these steps, the analysis of this literature review started with identifying the analysis units. As this study wanted to explore the patient’s experiences, the identified analysis units were the results of the chosen articles that described patients’ experiences. In the next step, the material was independently read thoroughly, one article’s result at a time, and meaning units were extracted. As the meaning units were identified, the authors together condensed them into codes. After that, in an independent process, the codes were condensed into sub-themes that captured the essence of each code. The attempt to identify themes that connected the sub-themes were then made, to find possible patterns in the patients’ experiences. Lastly, the findings were compared and discussed. This analysis process was made a couple of times more until the agreement of three themes and six sub-themes emerged (Table 3, p. 7).

7

Figure 1. The content analysis process as illustrated by the authors of this literature review, according to Danielson (2017).

RESULT

This literature review is based on the results of 12 articles that explore persons with psychiatric diagnoses’ experience of health care in non-psychiatric facilities. Seven articles were conducted in the USA (Keeley et al. 2014; Sternke et al. 2016; Weissinger et al. 2019; Richards et al. 2019; Harris et al. 2015; Byatt et al. 2013; Cabassa et al. 2014), two in the United Kingdom (Kadam et al. 2001; Campbell et al. 2007), one in Canada (Roberge et al. 2016), one in South Africa (Myers et al. 2018) and one in Sweden (Dahlöf et al. 2014). Most of the studies used a strictly qualitative method, where data was collected through individual interviews or focus groups interviews, three studies used mixed-method research, and two were secondary analyses of qualitative data. Each study had between 9 to 37

participants, leading to a result built on a total of 268 participants (192 women and 76 men) in this literature review. The age of the participants ranged from 18 to 95 years old. The results that emerged from the content analysis method are presented in three themes: (1) feeling subjected to prejudice, (2) variations in quality of support, and (3) impression of the environment. Every theme has two sub-themes, as shown in table 3.

Table 3. Themes and sub-themes.

Themes Sub-themes

Feeling subjected to prejudice Actions of discrimination Reluctance of opening up

Variations in quality of support Manifestations of support or the lack thereof Perceived competence of the caregiver

Impressions of the environment A stressed surrounding Feelings of discomfort

1. Identifying the analysis units and read the material a

few times

2. Identifying the salient meaning units and condensing them

into codes

3. Categorizing the codes into sub-themes 4. Examining the

sub-themes to see if there are themes that

connect them 5. Discussing and interpreting the result

8

Feeling subjected to prejudice

The participants experienced that caregivers had prejudice towards them because of their psychiatric diagnosis (Keeley et al. 2014; Kadam et al. 2001; Roberge et al. 2016; Sternke et al. 2016; Weissinger et al. 2019; Campbell et al. 2007; Richards et al. 2019; Harris et al. 2015; Byatt et al. 2013; Cabassa et al. 2014). According to Sternke et al. (2016), participants felt stereotyped and were labeled as drug users due to having both pain and depression. Similarly, Weissinger et al. (2019) raised the unfair feeling of being falsely associated with physical violence just because they had a psychotic disorder. Furthermore, Harris et al. (2015) and Roberge et al. (2016) mentioned that participants felt they were being negatively judged and stereotyped due to their mental health issues. This feeling of being stigmatized was found as a barrier when participants were seeking health care (Keeley et al. 2014) and influenced what they disclosed in the meeting with caregivers (Roberge et al. 2016).

Actions of discrimination

As a result of being subjected to prejudice, participants experienced being discriminated against by the caregivers (Cabassa et al. 2014). Campbell et al. (2007) reported experiences of inequities in how patients were treated by the staff depending on their background, which left participants with depression, feeling they were treated differently compared to other patients in a negative way. Likewise, Weissinger et al. (2019) brought up that participants felt they were being treated differently from other patients, based on caregivers’ less friendly approach and their apparent avoidance and ignorance. Participants in the other studies also felt they were being ignored by the caregivers when accessing care (Byatt et al. 2013; Cabassa et al. 2014). Similarly, participants in Harris et al.’s (2015) study experienced that caregivers made minimal eye contact with them, which increased the feeling of being invisible and negatively judged. Relating to being treated differently, participants experienced that caregivers tended to generalize them and treat them as a group instead of individuals (Sternke et al. 2016; Campbell et al. 2007). This left participants with a sense of not being regarded as a person (Harris et al. 2015).

In addition to being treated differently by the caregivers, discrimination was experienced by participants in situations where medical complaints were

dismissed and mistrusted due to their psychiatric diagnosis (Cabassa et al. 2014; Campbell et al. 2007). In some cases where physical symptoms were dismissed, participants were left being untreated for months before being taken seriously (Cabassa et al. 2014). The feeling of being distrusted was reinforced by actions like being frequently checked without verbal interactions during hospital visits (Harris et al. 2015). The caregivers’ behavioral patterns of ignorance, mistrust, and dismissal made participants feel disrespected (Cabassa et al. 2014; Weissinger et al. 2019; Byatt et al. 2013; Harris et al. 2015). A feeling of being dehumanized and disrespected was felt by the participants in Cabassa et al.’s (2014) study, due to caregivers' rudeness and impersonal behavior. This was also shown in Harris et al.’s (2015) result, where participants experienced carelessness and judgmental demeanor from caregivers. The participants’ experience of being disrespected was also mentioned by Weissinger et al. (2019) and Byatt et al. (2013). Furthermore, if participants with psychotic disorders happened to act violently, it was due to the feeling of fear, frustration, or being disrespected that the caregiver exposed them to (Weissinger et al. 2019).

9

Another common experience related to prejudice among the participants was that caregivers evaluated psychiatric symptoms as less important than medical

symptoms (Harris et al. 2015; Weissinger et al. 2019; Kadam et al. 2001; Sternke et al. 2016). Participants had been in situations where medical complaints

received faster help than if they were to express mental health symptoms

(Weissinger et al. 2019; Kadam et al. 2001). Weissinger et al. (2019) reported that some participants developed a strategy where they put all their efforts towards focusing on their medical symptoms to get help in time, even though they might also experience symptoms of their psychiatric diagnosis. To be received as less prioritized made participants feel marginalized and less worthy of care (ibid.).

Reluctance of opening-up

The participants were well aware of what kind of prejudice that might be applied to them and, based on past negative care experiences, they felt vulnerable and reluctant to what they shared with caregivers due to the consequences that might come out of it (Byatt et al. 2013; Harris et al. 2015; Richards et al. 2019;

Campbell et al. 2007; Weissinger et al. 2019; Keeley et al. 2014). The participants, in both Byatt et al.’s (2013) and Campbell et al.’s (2007) study, feared that the caregiver would interpret them as a danger to their own children if they would open up about mental health symptoms and that, therefore, they were at risk of losing custody over their children. Similarly, Harris et al. (2015) and Richards et al. (2019) mentioned a fear among the participants of being held against their will if they open up. Participants would therefore try to carefully monitor each word they said or did not say, to prevent potential restrictions being placed on them, which was difficult due to being in an unstable situation (Harris et al. 2015).

In Myers et al.’s (2018) result, participants expressed being scared of doctors and RNs when it came to opening up about mental health issues, due to a fear that these professionals are unable to manage psychiatric problems and what consequences that might lead to for the patients. The same applies to the

participants in Keeley et al.’s (2014) study, where they discussed that opening up to the wrong caregiver could potentially be harmful to the individual seeking care. Furthermore, participants felt ‘pressured’ to cultivate good relations with RNs, in order to receive the care and medication they needed (Weissinger et al. 2019). Thus, because of shame, pressure, and vulnerability as well as the fear of stigma and consequences associated with a psychiatric diagnosis, participants felt hesitant about what they disclosed in the meeting with caregivers (Byatt et al. 2013;

Richards et al. 2019; Campbell et al. 2007; Harris et al. 2015; Weissinger et al. 2019).

Variations in quality of support

An aspect that was discussed by participants, was the perception of the received support from their caregivers, as well as of the caregiver’s capability of managing the needs of persons with psychiatric diagnoses (Cabassa et al. 2014; Byatt et al. 2013; Harris et al. 2015; Myers et al. 2018; Dahlöf et al. 2014; Richards et al. 2019; Campbell et al. 2007; Weissinger et al. 2019; Sternke et al. 2016; Roberge et al. 2016; Kadam et al. 2001; Keeley et al. 2014). Participants stressed that the perceived support, or the lack thereof, had an impact on the care experience and its outcome, as well as for participants’ behavior (Campbell et al. 2007; Byatt et al. 2013; Weissinger et al. 2019; Richards et al. 2019).

10

Manifestations of support or the lack thereof

Except being subjected to prejudice, some participants experienced uplifting feelings associated with being supported by the caregivers (Byatt et al. 2013; Dahlöf et al. 2014; Cabassa et al. 2014; Richards et al. 2019; Sternke et al. 2016). In cases where caregivers had created an open and welcoming atmosphere for participants to raise concerns and questions, participants felt motivated and invested in their own treatment (Cabassa et al. 2014). Open communication between caregivers and caretakers also facilitated honesty and alleviated

vulnerability (Richards et al. 2019). Furthermore, Dahlöf et al. (2014) alluded to how the RNs’ warmth and security provided participants with the strength and energy needed to get through hard times. Similarly, Byatt et al. (2013) brought up how participants with experiences of supportive and empathetic caregivers

resulted in them feeling stronger and alleviated. In addition, Sternke et al. (2016) emphasized that empathetic actions from caregivers made participants feel believed and understood, thus felt supported.

In contrast, some participants had experienced discouraging feelings associated with being unsupported in the meetings with caregivers (Byatt et al. 2013; Harris et al. 2015; Weissinger et al. 2019; Cabassa et al. 2014; Campbell et al. 2007). Participants mentioned feelings of being isolated and unsure who to ask for help regarding mental health symptoms and that when they did reach out for help, caregivers did not act upon it, hence the feeling of being discouraged and unsupported (Byatt et al. 2013). Likewise, participants in Weissinger et al.’s (2019) study experienced that psychiatric concerns were forgotten by caregivers, which left them feeling alone and not knowing who to speak to about these concerns. A loss of control could be experienced in these kinds of situations, where there was a non-availability of resources (Harris et al. 2015). Another indicator of unsupportiveness was when the participants experienced feelings of frustration (Weissinger et al. 2019; Cabassa et al. 2014). Frustration could emerge in situations where the participants felt a loss of control due to an interruption in their daily routines, that otherwise made them feel safe (Weissinger et al. 2019). Situations, where there was a lack of personal attention or an inability to get timely appointments, were also a source of frustration, leading to participants feeling unsupported (Cabassa et al. 2014). To have negative relationships or experiences with caregivers based on unsupportiveness affected participants' compliance and their behavior in the care encounter (Campbell et al. 2007; Cabassa et al. 2014).

Through actions, caregivers appeared to be supportive or unsupportive (Keeley et al. 2014; Kadam et al. 2001; Sternke et al. 2016; Weissinger et al. 2019; Campbell et al. 2007; Richards et al. 2019; Dahlöf et al. 2014; Harris et al. 2015; Cabassa et al. 2014). Some participants had experiences of feeling acknowledged when caregivers behaved in certain ways (Keeley et al. 2014; Sternke et al. 2016; Weissinger et al. 2019; Dahlöf et al. 2014). Participants felt supported when the genuineness of the caregiver shone through in the provided care and when they felt they were treated with respect and dignity (Weissinger et al. 2019). This could be shown when caregivers spent time listening to and discussing relevant matters with the participants (Keeley et al. 2014). Furthermore, the RNs’ non-judgmental, equal, friendly, and helpful approach was appreciated by participants and made them feel supported (Sternke et al. 2016; Dahlöf et al. 2014).

11

Contrarily, a perception of being unsupported was experienced by participants when there was a lack of invitation to discuss psychological problems among caregivers (Kadam et al. 2001). It was brought up that participants felt that the psychosocial aspects of them were forgotten, ignored, or even avoided when forming the treatment (Byatt et al. 2013; Cabassa et al. 2014; Weissinger et al. 2019). Additionally, the participants perceived caregivers as unsupportive when they expressed a lack of engagement (Cabassa et al. 2014; Richards et al. 2019; Campbell et al. 2007). Participants in Richards et al.’s (2019) study experienced this when they felt that caregivers only asked about their mental health out of obligation, without any interest in the answer. Campbell et al. (2007) also discussed lack of engagement, where participants felt trapped in a treatment model that was supposed to fit all and caregivers failed to see them as a complex persons behind their symptoms. Lack of engagement could also be perceived in situations when participants felt that, during their appointment, the caregiver gave them minimal attention and was rushed (Cabassa et al. 2014). Participants

experienced that support was only given in acute situations and that they were left alone until that happened (Campbell et al. 2007).

Perceived competence of the caregivers

Although caregivers could be genuine and respectful, they also had to possess certain fundamental skills and competencies to be able to make caretakers feel fully supported (Byatt et al. 2013; Harris et al. 2015; Dahlöf et al. 2014; Richards et al. 2019; Campbell et al. 2007; Weissinger et al. 2019; Keeley et al. 2014). Some participants spoke of how there existed a lack of communication skills among caregivers (Campbell et al. 2007; Dahlöf et al. 2014; Byatt et al. 2013; Harris et al. 2015; Keeley et al. 2014). In the study made by Byatt et al. (2013), participants brought up how caregivers failed to inform them about the effects and side effects of medications, as well as what withdrawal symptoms that could occur if they stopped the medication. Lack of information was something that Harris et al. (2015) also mentioned, but in their study, participants experienced that they did not get information regarding waiting times. These missing bits of information made participants feel uncertain and powerless in their own care (Campbell et al. 2007; Dahlöf et al. 2014). Additionally, a few participants perceived that there was a lack of communication between care team members (Keeley et al. 2014). On the contrary, there were also situations where participants experienced that caregivers had communication skills. Those situations were when caregivers broached the subject of mental health and took participants’ consideration into account in the discussion of their care (Sternke et al. 2016; Richards et al. 2019; Weissinger et al. 2019; Keeley et al. 2014).

In two studies there was also a perception that caregivers lacked preparedness (Campbell et al. 2007; Byatt et al. 2013). Participants in Byatt et al.’s (2013) study felt that caregivers lacked the tools and preparation to discuss and manage

depression, and therefore they could not support in a good way. Campbell et al. (2007) raised that caregivers had too rigid focus, only giving reactive care and focusing on symptoms rather than gathering enough vital background information. It was also mentioned by the participants that they experienced the health care system as fragmented, which failed to meet the needs of persons with medical and psychiatric comorbidities (Keeley et al. 2014; Weissinger et al. 2019).

Nevertheless, both Dahlöf et al. (2014) and Byatt et al. (2013) brought up participants’ positive experiences of RNs’ helpfulness and readiness to act as a sign of preparedness.

12

Participants experienced that caregivers’ capability to support was affected by their possessed knowledge about psychiatric diagnoses (Roberge et al. 2016; Keeley et al. 2014; Weissinger et al. 2019; Campbell et al. 2007; Harris et al. 2015; Myers et al. 2018; Byatt et al. 2013). Many participants stressed that there was a lack of understanding and knowledge about their psychiatric diagnoses (Byatt et al. 2013; Harris et al. 2015; Myers et al. 2018; Campbell et al. 2007). The lack of knowledge among caregivers made them become perceived as

uncomfortable in the meeting with persons with psychiatric diagnoses, and it also made participants feel misunderstood (Weissinger et al. 2019). This led to

participants lacking confidence in caregivers’ capability to manage and treat mental health issues (Myers et al. 2018; Keeley et al. 2014).

Impressions of the environment

A third theme that emerged involved participants experiences of external and internal atmosphere.

A stressed surrounding

A common experience among participants was that they were surrounded with stress when they were seeking help (Cabassa et al. 2014; Myers et al. 2018; Richards et al. 2019; Kadam et al. 2001; Harris et al. 2015; Weissinger et al. 2019). Cabassa et al. (2014) described the caregivers as overburdened and stressed, and the clinic as overflowing with patients. Similarly, Richards et al. (2019) mentioned that participants experienced being rushed through their visits due to time limitations. Caregivers were perceived as being too busy to provide the psychiatric care that might have been needed (Kadam et al. 2001; Myers et al. 2018). Furthermore, participants found the surroundings to be loud and fast-paced with a constant change of staff (Weissinger et al. 2019). The lack of privacy participants experienced when doors and curtains were opened, and the bright lights were also aspects that increased the stress they experienced (Harris et al. 2015). Participants spent a long time in this environment, waiting to get help (Kadam et al. 2001; Weissinger et al. 2019). The stressed health care system that surrounded the participants, increased their distress and confusion leading it to become an intense experience (Weissinger et al. 2019; Harris et al. 2015; Cabassa et al. 2014).

Feelings of discomfort

Apart from participants having feelings involving support and being subjected to prejudice, the care environment was associated with various emotions of

discomfort (Cabassa et al. 2014; Harris et al. 2015; Weissinger et al. 2019; Dahlöf et al. 2014). Some participants experienced that being in a stressful atmosphere resulted in their discomfort of asking questions, hence leading to them taking on a passive role in their meeting with caregivers (Cabassa et al. 2014). Feelings of discomfort in this kind of environment were also raised by Harris et al. (2015), where participants felt distressed and pressured by routine care-related requests, like changing to a hospital gown, and by routine communication where they felt they could give wrong answers. The use of medical terminology and lack of eye contact by caregivers increased participants’ feelings of stress (ibid.) Likewise, Weissinger et al. (2019) brought up participants’ experiences of pain, difficulty, fear, and discomfort associated with hospitalization. To be at the hospital, away from their stability, resulted in participants' loss of control and a fear of receiving the wrong medication and therefore risking ending up having an outbreak in their psychiatric diagnosis (ibid.). Participants expressed that having a psychiatric

13

diagnosis resulted in more experiences of vulnerability than others, thus seeking help may be associated with feelings of discomfort (Dahlöf et al. 2014;

Weissinger et al. 2019).

DISCUSSION

This part includes method discussions and results discussions. In the method discussion, the chosen method’s strengths and weaknesses, as well as its trustworthiness are discussed. The result discussion will mainly focus on the results of three themes in relation to nursing care theories, the Swedish laws and the RN’s core competencies, along with the authors’ reflection regarding the subject.

Method discussion

As the aim of this study was to explore experiences of care from a patient perspective, a literature review based on qualitative articles was chosen as the most suitable method. In accordance with Henricson & Billhult (2017), a

literature review could enable a descriptive compilation of the articles’ results. An empirical study might have been of use when there is little material to offer regarding a subject (Mårtensson & Fridlund 2017), as the case was in this study. By conducting interviews based on open and/or structured questions, new salient first-hand data might have emerged (Danielson 2017b), that could have

contributed to a deeper understanding of the patient’s experiences. Due to time limitations, but also due to the recommendation and restrictions of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic (Public Health Agency of Sweden 2020), an empirical study was not conducted. Instead, a literature review was chosen as the best method to explore patient experiences, where results of scientific articles with a similar aim could be systematically compiled (Henricson & Billhult 2017). Through

compiling already existing data, this literature review resulted in an overview of the patients’ experiences of care. Even though this study cannot qualify as a systematic review, there was a systematic approach throughout the process.

Data collection process

According to Willman et al. (2016), the literature search should be made in more than one database to reach a valid number of results. Initially, this study was going to use three databases (PubMed, PsycINFO, and CINAHL), but there were only 15 search results on CINAHL, of which none could be applied to this study’s aim. Therefore, the CINAHL database was excluded from this study, but the use of two databases is still considered to increase the trustworthiness of the data collection.

After choosing databases, the keywords and their synonyms were identified. By identifying the different areas, based on Willman et al. 's (2016) description of the POR-model, the search was delimited and most of the quantitative search results could be avoided. In order to precise the search results further and avoid irrelevant articles, exclusion and inclusion criteria were formulated. There were some

difficulties in finding the right search for this study, as the aim was very specific with many salient components that had to be included in the content of the articles. As a result, Malmö University’s library personnel were contacted by the authors to see if they could provide some suggestions that could lead to a higher

14

number of relevant articles. The time set to find data was doubled compared to what was intended. Due to the difficulty of finding twelve relevant articles, it could be questioned whether the search method was inadequate or if there is simply a lack of research regarding the research topic. Accordingly, the authors performed a structured exploration of possible variations of the three

keywords psychiatric diagnoses, general health care, and patient’s experiences, and avoided the terms that were irrelevant for this study, to attain a high

sensitivity (Willman et al. 2016). Keywords, blocs, subject terms, Boolean terms, and asterisks were all used to maximize the number of relevant articles, see appendix 1.

It is worth mentioning that the original aim of this study was to explore how persons with psychiatric diagnoses experienced nursing care within somatic care, where the focus would have been on patients who were hospitalized due to a medical problem but also happened to have a psychiatric diagnosis. The authors had a particular interest in how these patients perceived how their psychiatric diagnosis affected the way they received care from RNs. As a difficulty of finding enough articles that embodied this topic was encountered, the aim had to be modified to also include patients' experiences of care from other health care professionals, although, not from an MHN and not in a psychiatric facility as stated in the exclusion criteria.

Quality review

In this study, the quality review was independently conducted to avoid influencing one another and interpretations were later discussed. According to Willman et al. (2016), this method increased the trustworthiness of the review. By using SBU’s (2017) review template with the quality assessment based on their criteria (SBU 2017), eight articles reached high quality and four reached medium quality. In a few studies made in the USA (Sternke et al. 2016; Byatt et al. 2013; Harris et al. 2015), the participants were given money as compensation, but no more than $40. In the South African study (Myers et al. 2018) the participant received a grocery voucher. Due to the monetary compensation and the already existing power balance between participants and researchers, the participants may feel obliged to answer in a certain way that is in favor of the researchers. Given the situation, it could be argued that there might be a different system compared to Sweden versus in the USA, where the participants expect monetary compensation for time. On the other hand, $40 might just be enough for transport costs and a meal. However, the compensations were in mind when making the assessment of the articles. Two studies were secondary analyses (Sternke et al. 2016; Harris et al. 2015), which affected the assessment to reach medium quality, as they could not attain data saturation. Kadam et al. (2001) failed to attain data saturation as well, which reduced the quality to medium. What affected Byatt et al.’s (2013) article to become of medium quality, was that they failed to mention their own pre-understanding of the subject.

As experiences are personal and different for each person, the results from qualitative studies cannot be generalized (Henricson & Billhult 2017). However, as the results could generate patterns of experiences, they might still be

transferable to groups, contexts, or situations (Mårtensson & Fridlund 2017). The intention for this study was to produce results based on persons with psychiatric diagnoses’ experiences of care within general health care, although intersecting

15

identity factors, such as gender or ethnicity, may have a significant impact on how the patient perceives the care. From an equality perspective, it is worth

mentioning that 64.4% of the 298 participants were women, which could have an effect on the result’s transferability as there might be gender differences in how needs are expressed, and the care is perceived. The majority of women could also be mirrored with the statistics according to Ritchie & Roser (2018), which reveals that it is more common among women to have been diagnosed (11.9%) compared to men (9.3%). The gender differences were not further explored by the studies included in this literature review.

Furthermore, six of the studies contained information about the participants’ ethnicity (Weissinger et al. 2019; Cabassa et al. 2014; Byatt et al. 2013; Harris et al. 2015; Sternke et al. 2016; Richards et al. 2019). One of these studies only included participants who were Hispanic (Cabassa et al. 2013) and one only had participants who were white (Byatt et al. 2013). Even though there were some differences between the studies, the totality showed a diversity of the participants’ ethnicity. The differences in the experiences regarding ethnicity was not further discussed by the studies. The other six studies did not mention any demographics other than gender and psychiatric diagnosis. As the result is based on a wide range of countries, ages, and ethnicities, it could be argued that there is a common pattern of experiences among a heterogeneous population with psychiatric diagnoses. Therefore, these commonalities of patterns could be transferable to similar situations.

Data analysis

Before starting with the analysis of data, a discussion and a reasoning was created regarding biases and pre-understandings about the subject. By increasing

awareness of how these factors could affect the analysis process, it might prevent the authors from intervening with and influencing the data. In order to ensure trustworthiness and avoid influencing one another, all articles were read separately and the extraction of meaning units were made individually. The meaning units were then compared, and a consensus was acquired between the authors, therefore, being a strength of this study. In the step of condensing meaning units into codes, only the words mentioned in the articles were used, as an attempt to maintain neutrality and not letting own values influence the

formulations. The process of categorizing codes into sub-themes was made several times until a consensus was reached and there was a clarity of a common thread among the themes. A weakness of content analysis is that it can be limiting in cases where a code fits in two or more themes, which forces the researcher to choose where it fits best, although, the meaning behind the code might be more complex. However, the data analysis could have continued for a longer period, but due to time limitations, this literature review had to progress.

Result discussion

The results in this study were based upon patients’, with psychiatric diagnoses, experiences of care within general health care and, which were presented in three themes: Feeling subjected to prejudice, Variations in quality of support, and

Impressions of the environment. In this part, the results will be discussed in

relation to Jean Watson’s and Kitson et al.’s (2014) nursing theories, the Swedish law, the RN’s competence description, and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, in the light of a nursing care focus.

16

Feeling subjected to prejudice

In the result, it became evident that persons with psychiatric diagnoses shared a feeling of being subjected to prejudice by caregivers which could have severe implications on the individual’s life, health, and general wellbeing. Participants in this literature review shared experiences of caregivers displaying discriminating behaviors towards them, which can be confirmed in Mavundla’s (2000) study of the RN’s perspective on treating patients with psychiatric diagnoses. This study also revealed that the RN’s preconceived ideas about this patient group negatively affected their way of providing care (ibid.). Several instances were found in our results where treatment was inadequate, overlooked, or withheld by caregivers. Discriminating behaviors could be manifested by caregivers when they ignored or avoided contact with participants (Byatt et al. 2013; Cabassa et al. 2014;

Weissinger et al. 2019; Harris et al. 2015), as well as when they dismissed and mistrusted the participants when they sought help (Cabassa et al. 2014; Campbell et al. 2007; Harris et al. 2015). This, in combination with impersonal behaviors, such as rudeness or carelessness, led the participants to feel that they were less important and trustworthy compared to those without a psychiatric diagnosis (Byatt et al. 2013; Weissinger et al. 2019; Harris et al. 2015). General distrust in the health care system due to previous experiences resulted in some individuals abstaining from seeking care or withholding important information from their caregivers, fearing potential consequences or repercussions (Richards et al. 2019; Byatt et al. 2013; Harris et al. 2015; Campbell et al. 2007; Weissinger et al. 2019; Keeley et al. 2014).

The revealed discriminating behaviors of caregivers goes against the Swedish Discrimination Act, 2008:567 (DL), which states that discrimination against persons on the grounds of their [mental] disability, along with other factors such as gender, sexuality, and ethnicity, is prohibited. In addition, all patients have the right to equal health care and to be treated with respect and dignity according to the Swedish Health and Medical Services Act, 2017:30 (HSL). This is also in line with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which insists on every human’s right to equal treatment and dignity (United Nations 2020). A reflection on discrimination is that it rarely happens with the intention to cause harm. Rather, it may be subtle, repetitive, seemingly insignificant singular events that are part of a systematic process. These accumulated past experiences may inform a person’s interpretations of subsequent interactions, meaning they may have a heightened awareness of discriminatory actions. There may be a difficulty for the individual patient to report singular instances as an act of discrimination, therefore, it is important that the RN raises awareness of anti-discriminatory practice within themselves and their workplace, especially for people who fall under the protected grounds of discrimination. The authors propose that anti-discriminatory practice is not merely the absence of discrimination, but rather a commitment to

continuously work towards greater inclusivity and equality.

Watson (1985) emphasizes that the RN must aspire towards developing a

humanistic-altruistic system of values in order to provide human-centered care of a high ethical standard. Psychological presence and open-mindedness allow for greater awareness and thus minimizes the risk of letting perceptions, such as stereotypes, have a negative effect on communication (ibid.). It could be believed that when certain values or preconceived ideas about a group are identified, it may permit the RN to see past a simplistic representation of a person and instead value them as a unique and multifaceted individual. The patient’s experiences in the

17

meeting with caregivers should be founded on trust and a feeling of safety, where the patient is an active participant in the care process. In accordance with Watson (1985) and Cronenwett et al. (2007), this could be established through adopting a person-centered approach by implementing caring attitudes such as genuineness, empathy, and unconditional acceptance. A person-centered care approach would align with the United Nations’ (2020) Universal Declaration of Human Rights as well as with HSL (2017:30) and DL (2008:567), and it would help the RN to uphold these values that ensure fair treatment of all patients.

Variations in quality of support

According to the HSL (2017:30), one of the health care system’s goals is to provide the population with equal health care, with the same conditions applied for everyone. As seen in the results of this study, the support participants received from caregivers varied. Most of the participants reported that caregivers displayed a lack of support towards the participants and that there was a lack of competence among caregivers (Byatt et al. 2013; Harris et al. 2015; Weissinger et al. 2019; Cabassa et al. 2014; Campbell et al. 2007). However, the results also showed that some participants experienced positive and uplifting feelings relating to the support they received, when caregivers allowed for open communication, a welcoming atmosphere, warmth, feeling of security, and empathy (Byatt et al. 2013; Dahlöf et al. 2014; Cabassa et al. 2014; Richards et al. 2019; Sternke et al. 2016). Contrary to negative experiences, this led to participants feeling more motivated to be active in their own care and increased their compliance with the treatments (ibid.). This is in accordance with the altruistic-humanistic views of Watson (1985), who argues that the patient’s trust in the RN is established when they feel that the RN communicates with empathy, genuineness, and

non-judgment. In agreement with Watson (1985), the authors of this literature review believe that the faith and hope that might entail from the given support is

fundamental for the healing process. Therefore, it is the RN’s responsibility to build a nurse-patient relationship based on these values, in order to enable optimal recovery.

Lack of knowledge amongst caregivers was often mentioned by participants, which led to them feeling hesitant towards the caregivers’ capability to assist them in a proper way (Weissinger et al. 2019; Myers et al. 2018; Keeley et al. 2014). Interestingly, in a study made by Shirilee et al. (2006), it was confirmed that RNs did experience a lack of knowledge about psychiatric diagnoses and that it

negatively affected the provided nursing care. Therefore, it could be argued that a lack of knowledge could have a negative impact on the patient's safety, as the patient might not get sufficient care that is needed. According to the RN’s competency description (SSN 2017; Cronenwett 2007), as well as the Patient Safety Act, 2010:659 (PSL), the RN has an obligation to practice nursing care and provide patients with adequate support and information based on research and scientific evidence. It could be argued that not all RNs received sufficient education covering psychiatric diagnoses and, therefore, the RN may feel that they lack knowledge regarding how to properly assist a person with psychiatric diagnoses. In these situations, as one of the core competencies is collaboration in teams, the RN has a responsibility to be attentive to the patient’s needs and to guide them towards other health care professionals, that could provide and tend to the patient's specific needs (SSN 2017; Cronenwett et al. 2007).

18

Providing proper nursing care is the RN’s main responsibility, and it should be based on the RN’s core competencies (SSN 2017). One of these core

competencies is to provide person-centered care (ibid.), and a belief is that it can be one of the solutions to counteract the participants' experience of the lack of support. Kitson et al. (2014) suggest that care and compassion are the main components of person-centered care. As seen in the results, participants valued and appreciated when caregivers took their time to discuss relevant matters (Keeley et al. 2014), which is one of many ways a RN can, through their actions, communicate patient-centered care. Empathic behaviors displayed by the

caregivers seem to play a big role in how the participants experienced the support they received (Dahlöf et al. 2014; Byatt et al. 2013). Furthermore, when

participants experienced a genuine act from the caregiver, the participants felt treated with respect and dignity. This shows that Kitson et al.’s (2014) and Watson’s (1985) theories on the empathic and genuine behavior of a RN are vital to how a patient might experience the provided care.

Impressions of the environment

In several studies, it emerged that the participants felt stressed in relation to their contact with the health care system. This was in part due to environmental factors (Cabassa et al. 2014; Richards et al. 2019; Myers et al. 2018; Kadam et al. 2001; Harris et al. 2015; Weissinger et al. 2019), such as lack of privacy, loud and fast-paced surroundings, and bright lights. Based on the philosophy and science of caring of Watson’s (1985), a RN has a duty to support, provide and protect the patient in a holistic way, caring for both physical and mental health. As the care takes place in a particular context, where external variables may impact the patient’s overall experience, it is also the RN’s responsibility to take these factors into consideration (ibid.). By practicing nursing care with a person-centered care approach, the RN should try to create a comfortable environment that is adapted to the patient’s needs (Kitson et. al. 2014). Even though there are limitations in what a RN can do to amend external variables, a belief is that the RN can still try to reduce the patient’s stress level by providing calmness, security, and kindness.

Participants also mentioned that they felt caregivers were rushing them through their appointment, presumably due to lack of time, and that the caregivers seemed too overburdened and busy to provide psychiatric care (Cabassa et al. 2014; Kadam et al. 2001; Myers et al. 2018). Furthermore, increased distress was experienced by the participants during hospitalization, due to the sudden change in their daily routines and the fear of losing the continuity of their pharmaceutical treatment (Weissinger et al. 2019). Certain interactions with caregivers also increased the participant’s feelings of distress, partly due to how the routine communication was managed and due to the staff’s use of medical terminology (Harris et al. 2015). Kitson et al. (2014) point out that it is vital to acknowledge that there is a power dissemblance that occurs during nurse-patient interaction, where the patient is dependent on the RN. The patient's position of being disempowered may increase their feeling of vulnerability and passiveness and, therefore, it is of importance that the RN fosters a nurse-patient relationship where both parties are equal. In agreement with Kitson et al. (2014), a suggestion is that good communication between the RN and their patients is essential in order to uphold a therapeutic alliance. This could prevent misunderstanding and

disappointment, increase the patient’s trust in the RN, and stimulate the patient’s participation in their own care.

19

CONCLUSION

This literature review explored the experiences of care within general health care from the perspectives of persons with psychiatric diagnoses. Findings revealed that the participants shared experiences of being discriminated against by caregivers on the grounds of their psychiatric diagnoses. This goes against the Swedish Discrimination Act, which aims to prevent discrimination against persons on certain grounds. Furthermore, participants experienced receiving insufficient care as a result of caregivers’ lack of knowledge and support. In accordance with the RN’s core competencies, the RN has the responsibility to present their patients with personalized information and to provide evidence-based care, as well as collaborating with other health care professionals who may possess specific knowledge. Participants portrayed a need for validation,

acceptance, safety, and to feel cared for. When these needs were not met, the participants expressed that it had a negative effect on their compliance and

attitudes regarding the care, but also on their feelings of worth. What also became evident in the results was that when the participants had good experiences with caregivers, it was due to the openness, warmth, and empathy that was displayed towards the patients, which is in line with the caring attitudes of the person-centered approach. The RN’s morals and ethics are founded on the philosophy that all humans should be treated as equals and individuals, while also attending to the patient’s specific needs and considering the patient’s feelings of vulnerability when providing care. It is, therefore, the RN’s responsibility to care for a person with psychiatric diagnoses as a whole human, not symptoms, who has their own freedom, rights, abilities, beliefs, integrity, and dignity. The authors believe that nursing care should be provided with respect for the patient’s autonomy, where the patient is not merely included, but the center of the team.

SUGGESTION OF IMPROVEMENT AND

QUALITY DEVELOPMENT

The results from this literature review have contributed with an insight into how persons with psychiatric diagnoses experience care in a non-psychiatric setting. Stigma and discriminatory behavior towards persons with psychiatric diagnoses seem to be an existing problem among health care professionals due to lack of knowledge. Therefore, in order to prevent this from happening, an awareness of these issues must be raised. The authors suggest that further education on psychiatric diagnoses, stigma, and discrimination is needed among RNs.

Furthermore, an implementation of anti-discriminatory practice at all workplaces should be established, where the practice is continuous and informed by the RN’s self-reflection on their perceptions, especially in the meeting with patients who fall under the protected grounds of discrimination. This, together with a person-centered approach, might be the key to uphold the RN’s values and the goals of nursing care.

There is a limited amount of available research on the experiences of persons with psychiatric diagnoses, especially in relation to the patient’s perspective on the received care from RNs outside of specialized psychiatric care. Further research on this topic is crucial in order to gain a broader understanding, knowledge, and

20

insight, which can be used to develop and improve the provision of health care. Future research would benefit from an intersectional analysis, where overlapping experiences of oppression and marginalization might lead to an increased risk of discrimination within the health care system.

21

REFERENCES

American Psychiatric Association, (2013) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of

Mental Disorders fifth edition. Arlington, American Psychiatric Association.

Arvaniti A, Samakouri M, Kalamara E, Bochtsou V, Bikos C, Livaditis M, (2008) Health service staff’s attitudes towards patients with mental illness. Social

Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 44, 658-665.

Byatt N, Biebel K, Friedman L, Debordes-Jackson G, Ziedonis D, (2013) Patients’ views on depression care in obstetric settings: how do they compare to the views of perinatal health care professionals? General Hospital Psychiatry,

35(6), 598-604.

Cabassa LJ, Gomes AP, Meyreles Q, Capitelli L, Younge R, Dragatsi D, (2013) Primary health care experiences of hispanics with serious mental illness: a mixed-methods study. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health

Services Research, 41(6), 724-36.

Campbell SM, Gately C, Gask L, (2007) Identifying the patient perspective of the quality of mental healthcare for common chronic problems: a qualitative study.

Chronic Illness, 3(1), 46-65.

Cronenwett L, Sherwood G, Barnsteiner J, Disch J, Mitchell P, Sullivan DT, Warren J, (2007). Quality and safety education for nurses. Nurse Outlook, 55, 122-131.

Dahlöf L, Simonsson A, Thorn J, Larsson ME. (2014) Patients' experience of being triaged directly to a psychologist in primary care: a qualitative study.

Primary Health Care Research & Development, 15, 441-51.

Danielson E, (2017a) Kvalitativ innehållsanalys. I: Henricson M, (Eds)

Vetenskaplig teori och metod: från idé till examination inom omvårdnad (1st

edition). Lund, Studentlitteratur AB.

Harris B, Beurmann R, Fagien S, Shattell MM. (2015) Patients' experiences of psychiatric care in emergency departments: A secondary analysis. International

Emergency Nursing, 26, 14-19.

Henricson M, Billhult A, (2017) Kvalitativ metod. I: Henricson M (Eds).

Vetenskaplig teori och metod: från idé till examination inom omvårdnad (2nd

edition). Lund, Studentlitteratur AB.

Kadam UT, Croft P, McLeod J, Hutchinson M. A, (2001) qualitative study of patients' views on anxiety and depression. British Journal of General Practice,

51(466), 375-80.

Keeley RD, West DR, Tutt B, Nutting PA, (2014) A qualitative comparison of primary care clinicians' and their patients' perspectives on achieving depression care: implications for improving outcomes. BMC Family Practice, 15:13.