What Would Middle

Managers do?

A Case Study of a Culturally Shifting

Global Pharmaceutical Company

AUTHORS: Ata Günes and Leonardo Arboleda Sarmiento

PROGRAM: Master Thesis in Business Administration - Digital Business TUTOR: Ryan Michael Rumble

Master Thesis in Business Administration – Digital Business

Title: What would middle managers do? A Case Study of a Culturally Shifting Global

Pharmaceutical Company

Authors: Arboleda & Günes

Thesis supervisor: Ryan Michael Rumble Date: May 24th, 2021

Key words: Digital Tool Usages, Internal Innovation Processes, Innovation Culture,

Leadership for Innovation, Middle Managers.

Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this paper is to explore how middle managers attempt to enhance internal innovation processes with digital usages. To do so, this research aims to open up an internal innovation process improvement ‘black box’ by looking not only at issues related to digital delivery but also at elements related to innovation culture and leadership.

Design/method/approach

To fulfill this purpose, this qualitative research develops a case study employing the lenses of middle managers to generate empirical data based on an interpretative approach and an in-depth semi-structured interview methodology.

Findings

Middle managers' attempt to enhance internal innovation processes with digital usages involves major elements related to influencing people’s mindset, motivating and embracing ideation, as well as collaboration across units leveraged by digital usages. Nonetheless, the core element of the attempt stands for the ability to root the digital tool usages not only at the individual or team level but also at the innovation process level.

Contributions

This study mainly contributes to theory extension by putting the individual at the heart of the organization's innovativeness culture and enlightening the leadership role of middle managers to influence innovative behaviors to embrace digital tools in the line of the organization’s strategy with major demands for change management.

Originality/value

By integrating the perspective of middle managers to the conceptual, this case study brings an additional piece to the puzzle of how digital tools nurture the internal innovation processes.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our most sincere gratitude to our thesis supervisor, Ryan M. Rumble, for being always supportive during this academic journey. It was a privilege for us to count on his insightful guidance and unique ability to immerse ourselves in the research field. We also extend this appreciation to our case company for letting us interact and dialogue with the most important asset of the organization: Human talent. Special recognition to Özgül Ergüler and the group of middle managers for bringing the best of their expertise to enrich the research value of this case study. Last but not least, an appreciation to Beyza Gürel, research assistant at İzmir University of Economics, as well as to our class and seminar fellows, Dennis Van Den Bosch, Lea Sophie Lindemann, Marcel Wiegand, Niek Van Vonderen, Philipp Czarske, Tim Jonas Dumath, Ting Yang, and Yang Wu, who kindly contributed not only with their time but also with their valuable feedback to make this research project evolve in the way we expected.

Sincerely,

Ata Günes and Leonardo Arboleda

4

Table of Contents

Key Definitions 6 1 Introduction 7 1.1 Background 8 1.2 Problem Discussion 91.3 Purpose and Research Question 10

1.4 Contributions 11

1.5 Delimitations 11

1.6 Outline 12

2 Frame of Reference 13

2.1 Internal Innovation 14

2.1.1 Definition of Internal Innovation 14

2.1.2 Innovation Processes 14

2.2 Digital Tool Usages 17

2.2.1 Digital Tools Usage Definition 17

2.2.2 The Role of Digital Tools Usages 17

2.3 Innovation Culture 18

2.3.1 Definition of Innovation Culture 18

2.3.2 The Role of Digital Tools and Innovation Culture 19

2.4 Middle Managers 19

2.4.1 Strategic Role of Middle Managers 19

2.4.2 Leadership for Innovation 20

3 Method 22

3.1 Research Philosophy and Approach 23

3.2 Methodological Choice 23

3.3 Research Strategy 24

3.3.1 Case Study 24

3.3.2 Grounded Theory 25

3.4 Empirical Setting 26

3.4.1 Sample Selection: Snowball Sampling 26

3.4.2 Data Collection: In-Depth Semi-Structured Interviews 27

3.5 Data Analysis Procedure 28

3.6 Trustworthiness 29 3.6.1 Credibility 29 3.6.2 Confirmability 29 3.6.3 Dependability 30 3.6.4 Transferability 30 3.7 Research Ethics 30 4 Empirical Findings 32

4.1 Middle Managers’ Attempt at the Organizational Level 35

4.1.1 Innovative Organizational Culture 35

4.1.1.1 Effective Communication 35

4.1.1.2 Culture Where Ideas Can Be Voiced and Embraced 36

5

4.1.1.4 Collaboration and Knowledge Flows Across Units 38

4.1.1.5 Culture as a Domain of Change 39

4.1.2 Tactical Leadership of Middle Managers 40

4.1.2.1 Visionary and Problem-solving Mindset 40

4.1.2.2 Operational Role of Middle Managers 41

4.2 Middle Managers’ Attempt at the Process Level 42

4.2.1 Perceived Value of Digital Tool Usages 43

4.2.1.1 Process-Level Value of Digital Tool Usages 43

4.2.1.2 Collective Value of Digital Tool Usages 44

4.2.2 Digital Integration 44

4.2.2.1 Integrating Digital Tools to the Innovation Processes 44

4.2.2.2 Simplification and Automation of Existing Systems 45

4.2.2.3 Lack of Digital Tools Integration 46

4.3 Combined Level 46

4.3.1 Change Management 46

4.3.1.1 Digital Adoption at the Individual Level 47

4.3.1.2 Practical Training and Orientation 47

4.3.1.3 Strategic Alignment 48

5 Discussion 49

5.1 Theoretical Contributions 50

5.2. Managerial Contributions 52

6 Conclusion, Limitations, and Suggestion for Further Research 54

6.1. Conclusion 55

6.2 Limitations and Suggestion for Further Research 55

Appendices 57

Appendix 1. Sample and Interview length details 57

Appendix 2. Interview Protocol 58

6

Key Definitions

Chief Executive Level: from a strategic role perspective, the chief executive level envisions

the sense of identity and mission for the organization (Hart & Quinn, 1993) and crafts the organization’s strategy while shaping the organization as the external landscape change (Galambos, 1995)

Digital tool Usage: it refers to the use of digital tools within life and work-related situation to

seek, find and process information, and then to develop a solution addressing the task or problem (Martin & Grudziecki, 2006).

Internal innovation: effective changes in products, services, or processes within the

boundaries of the firm. It is generally based on internal communication, collaboration, and coordination among employees to create valuable ideas (Lassen & Laugen, 2017).

Middle Managers: oftentimes referred to as "general, regional, and divisional manager,

middle managers are the ones having roles between the strategic chief executive level and the operating core of an organization. Middle managers are recognized for contributing to implement strategic decisions and facilitate information flows between top managers and operating-level managers (Ren & Guo, 2011).

Organizational innovativeness: a sense of openness to new and valuable ideas as an element

7

1 Introduction

This paper explores the attempt of middle managers to enhance internal innovation processes with digital tool usages. To familiarize the reader with the aim of this research, it is introduced the internal innovation pattern bridging the connection with organizational dimensions. Moreover, it is also introduced the role of digital tools as enablers for knowledge creation in pursue of internal innovation at the organizational and process level. Context-wise, it is added a reference both to the opportunity and uncertainty that the variety of digital tools bring to organizations.

8

1.1 Background

The organization's ability to generate ongoing innovations stands as a key dynamic capability in the digital age (Giniuniene & Jurksiene, 2015; Wu et al., 2016). Cassiman and Veugelers (2006) found that innovating organizations perform better when tightly integrating internal innovation activities with external technology sourcing (Cassiman & Veugelers, 2006).

Therefore, organizations deploy external technology, such as digital tools, to help employees create and share the ideas and knowledge needed to innovate within and outside their organizational boundaries (Benitez et al., 2018). With the rise of digitalization, the introduction of entirely new digital tools is a far more substantive change of innovation than previous generations of tools enabled. These tools, including communication web and mobile-based applications, can foster the creation of knowledge. For example, via rapid dissemination of ideas or faster problem-solving with an impact on the quality and pace of the output. (Marion & Fixson, 2021). But the potential of these digital tools needs to be tempered (Thomke, 2006) and investigated in the context of organizational management. A 2014 McKinsey digitalization survey with chief-level executives (C-level) of large companies found that organizations must tackle key organizational issues before digital can have a truly transformative impact on their business (Gottlieb and Willmott, 2014).

In this paper, innovation is referred to as the life blood of organizational survival with a central role in terms of value creation (Zahra & Covin, 1994). As for Bessant et al. (2005) innovation represents the key renewal process in any organization. Therefore, innovation is tightly related to change, as organizations use innovation as an element to influence, for example, their internal environment (Damanpour, 1991). Furthermore, innovation appears as the most knowledge-intensive organizational process, which depends on the communication of individual members and the collective knowledge of the firm (Adamides & Karacapilidis, 2006). Communication has a role in creating and sustaining a culture for innovations (Ahmed, 1998) as well as in maintaining organizational efficiencies (Moenaert et al., 2000). That said, this research embrace a broad perspective of innovation with a focus on value creation, organizational change, communication and collaboration within the internal environment, as well as knowledge creation in pursue of internal innovation improvement.

9

1.2 Problem Discussion

As outlined in the background, digital tools are already reshaping existing work-related practices and will do so even more in the future, allowing organizations to rethink their business processes (Allen 2015; Matt et al., 2015). But what are the concrete implications of a dynamic digital tool landscape on internal innovation processes? Empirical research has shown that the use of digital tools tends to be related to the level of communication and collaboration (Peng, Heim, and Mallick, 2014), which in itself is correlated with the creation and distribution of knowledge. Previous studies go beyond and suggest that the implementation of digital tools supports work activities needed for fast-paced innovation (Dery et al., 2017) and has a major impact on innovation processes (Nambisan et al., 2017). It is also known by the existing literature that the use of digital tools represents how this usage is organized (DeSanctis & Poole, 1994; Markus & Silver, 2008) and how digital tool usages support individual and collective-level innovative goals (Burton-Jones & Gallivan, 2007; Nambisan et al., 2017; Orlikowski, 2000; Pentland & Feldman, 2007). However, digital delivery is as much about cultural change as it is about bringing new technology (Accenture and HMRC, 2016). Therefore, having the digital tools (technological capability) and the innovation cultural mindset are key enablers of innovation. But it is also important to have an effective leadership style to drive the innovation process efficiently and effectively (Oke et al., 2009).

Despite existing research has already framed the role of digital tools and innovation cultural mindset as enablers for innovation, it is still neglected in the literature how digital tools are used and organized at the operational level to enhance internal innovation. Moreover, academic literature and trending studies have focused largely on the chief-level executive perspective rather than on the middle or operational level management (Chuang et al., 2011). Therefore, there is a window of opportunity to explore the way the digital tools contribute or inhibit the ability of middle managers and their teams to execute their aspirations to internally innovate. In consequence, middle managers are considered as the unit of analysis for this study due to their contribution to implementing strategic decisions and facilitating flows between the top and operating-level managers, as well as their leadership managerial role model towards innovative behaviors (Ren & Guo, 2011).

Bridging the above-mentioned gap in the literature is relevant as the rise of digital has been increasing pressures that demand new business capabilities to adapt to new market realities (Jordan Bar Am et. al, 2020). However, and as outlined in the background, there is a

10 latent need for a better understanding of how these digital tools have a truly transformative impact. A 2014 McKinsey & Company study, for example, found that only 7% of 850 C-level executives believe that their teams understand the value that digital tools bring to the organization (Gottlieb and Willmott, 2014). On top of that, the Covid-19 pandemic has led to an inevitable surge in the use of digital technologies (De’ et al., 2020), bringing this uncertainty to a massive level. The 2020 McKinsey Innovation through Crisis Survey found a decline in focus on innovation across industries –except for pharmaceuticals– during the Covid-19 crisis. That said, managers face a crucial decision around embracing innovation-driven development in the short term with major implications for their organizations’ ability to sustain growth in the years to come (Jordan Bar Am et. al, 2020).

1.3 Purpose and Research Question

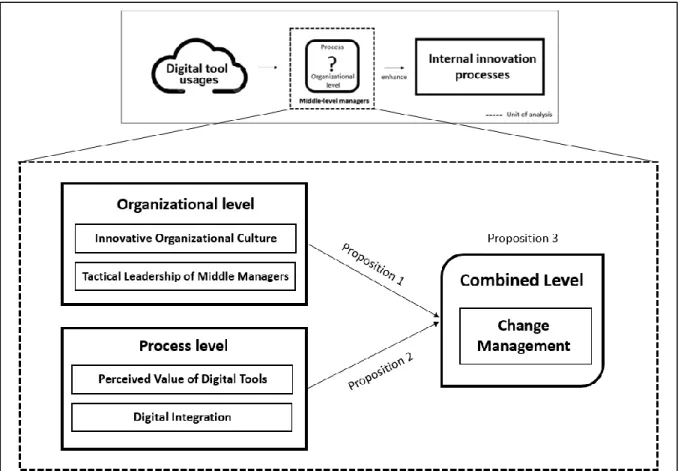

As outlined in the previous discussion, there is a latent need to understand how digital tools are used and organized at the operational level. That is why, and as depicted in figure 1, this research proposes to open up an internal innovation process improvement ‘black box’ faced by organizations due to the increased number of emerging digital tools (Denner et al., 2018), as well as the variety of digital usages (Martin & Grudziecki, 2006) with an impact at the organizational and process level. To fulfill this purpose, this paper develops a case study research employing the lenses of middle managers to generate empirical data based on their perceptions and interpretations towards the attempt to enhance the internal innovation processes with digital usages. That said, several angles surround the ability of middle managers to internally innovate which might include not only the digital delivery but also elements related to innovation culture and leadership such as a high level of communication, collaboration, out-of-the-box thinking, and problem-solving. Hence, this study aims to answer the following research question:

How do middle managers attempt to enhance internal innovation processes with digital tool usages?

11

1.4 Contributions

This paper employs the theoretical lenses of leadership and innovation culture with the insights of a case study within a company operating in the pharmaceutical industry. Data has been collected through a careful in-depth semi-structured interview process with a set of middle managers. Based on the inputs gathered from the empirical data, the outcome of this research is to open a process improvement back box, as outlined in the research purpose, and generate a conceptual framework contributing with knowledge within the literature. Therefore, with this framework, we intend to enlighten the unseen roads that middle managers take and comprehend the significance of the implementation and execution role throughout internal innovation processes with digital tool usages. In doing so, this paper contributes to theory by bringing a viewpoint of the operational actions and attempts towards organizational innovativeness from the angle of middle managers. Managerial-wise, this research contributes to enrich the understanding of the leadership role of middle managers with digital tool usages and its implications at the process and organizational level.

1.5 Delimitations

Our primary aim, as researchers, is to gather the most relevant information and, capture the most valuable empirical insights within the limited time of this Master thesis period. That is why, this case study was based upon some specifications and delimitations. First, due to the pandemic period, every single interview was conducted remotely. Even the researchers have been working physically separated but mentally together. Second, it was selected one of the most-used apps-based communication and meeting tools, Zoom, to conduct the interviews in the most effective way possible. Although it could not substitute a physical interview, Zoom allowed us to examine and analyze our data over and over again with its recording feature. Third, this case study excludes C-level managers as this level is not in charge of the implementation of digital-related tools. Instead, it focuses on middle managers because of the pivotal role of this target group when concerning the implementation and, way more significantly, the integration of the digital tools at the process level. Moreover, the total number of interviews was limited to 10 middle managers currently working at Case Company operating in the pharmaceutical industry. Fourth, the choice of “digital tools” was primarily specified as web and mobile-based communication and collaboration tools, excluding those not related to

12 the nature of this research like marketing, financial, and/or operational related digital tools. Last and not least, since there is extensive literature regarding tool selection, this case study focuses on the adoption and integration of digital tools at the process level.

1.6 Outline

This thesis is structured as follows. Section 2 is framed based on existing theory related to the 3 constructs of this research: internal innovation, digital tools in use, and middle managers, as well as innovation culture and leadership for innovation. Section 3 describes the research philosophy and approach adopted for this study, the method used for the empirical analysis, as well as elements related to trustworthiness and research ethics. Section 4 reports the empirical findings of this case study research. Section 5 elaborates on the discussion bringing the contributions from the theory and managerial perspective. Finally, section 6 draws the conclusion and limitations of this study, as well as the suggested future research avenues.

13

2 Frame of Reference

This section brings together the theoretical underpinnings for this case study. Firstly, it is elaborated the foundations and rationale of the internal innovation processes. Secondly, it is provided an understanding of digital tool usages bridging the connection with the innovation culture mindset. Thirdly, it is reviewed the literature on leadership for innovation highlighting the strategic leadership role of middle managers to enrich the innovation culture within the organization.

14

To outline and develop the frame of reference for this study, a first literature review was performed using the Web of Science database and Google Scholar as sources of information. Both search engines were used targeting peer-reviewed articles written in the last 10 years containing the combination of one or more of the following terms: digital tools in use AND internal innova* AND middle managers. As an output of this preliminary search, it was identified the need of targeting the term digital usages to get more accurate results in the line of the scope of this study. Browsing the papers, it was identified a broader range of keywords relevant for the theoretical lenses utilized for this study including innovation culture and

leadership for innovation. As part of an advanced search targeting the aforementioned terms,

researchers have managed to focus on 45 peer-reviewed articles related to this study, as well as non-academic studies conducted by McKinsey & Company and Deloitte.

2.1 Internal Innovation

2.1.1 Definition of Internal Innovation

Internal innovation means effective changes in products, services, or processes within the boundaries of the firm. It is generally based on internal communication, collaboration, and coordination among employees to bring and embrace valuable ideas (Lassen & Laugen, 2017). In the same line, Hameed et al. (2018) emphasize the role that these 3 constructs represent to positively influence internal innovation through design thinking and brainstorming sessions, as well as follow-up mechanisms (Hameed et al., 2018). As an extension of this reasoning, Zhang and Tang (2017) bring the perspective of knowledge management by reiterating the direct relationship between collaboration and innovation as part of the organizational strategy. This is argued by claiming that employee coordination and collaboration set the foundation for multiple forms of knowledge creation with the ultimate goal of fostering innovation (Zhang & Tang, 2017). From a managerial perspective, Santos-Vijande et al. (2016) bring the role of empowerment, involvement, and engagement that managers should grant to their employees to develop and sustain innovation from an internal perspective. (Santos-Vijande et al., 2016).

2.1.2 Innovation Processes

Recent research approaches recognize that innovation should not be seen as a stand-alone affair, but rather as a process. Therefore, innovation as a process demands the integration of activities and duties in a highly structured way. Furthermore, existing literature highlights

15 the significance of identifying the interrelations between these activities and promoting work routines that contributes to accelerating the pace of any innovation process (Tidd et al., 1997). For the purpose of this research, this paper focuses on the following innovation processes: Ideation

Creating new ideas is fundamental to organizations as they constitute the starting point of innovation endeavors (Björk et al., 2010). In other words, it stands as the raw material for innovation. Hargadon & Sutton (2000) relate this as the creation stage but emphasizing the structure behind this process. Oftentimes, it also involves searching and processing data from different sources as a way to create and assess ideas (Hargadon & Sutton, 2000). In the line of

Hameed et al. (2018), Nagano et al. (2014) point out the importance of having collaboratives mechanisms to bring perspectives from different organizational units enriching the process of finding the solution to a problem or opportunity of improvement (Nagano et al., 2014). Chesbrough (2004) also acknowledges the complexity of the ideation process in the context of the digital age. As a consequence of the increased development of information and communication technology including communities, there is a growing potential of idea sources outside organizations which are becoming increasingly important (Chesbrough, 2004). This point is particularly relevant as the identification of ideas depends not only on the inspiration and creativity of employees but also on the organizations' capability to stimulate the explicit generation and formulation of ideas. The use of different collaboration tools appears to be a central concept. By allowing idea providers to post their ideas in a tool accessible by others, new ideas can be fostered. Björk et al. (2010) state in absence or less focus of an IT capability can be compensated by cross-functional teams for ideation, or the combination of internal and external parties (Björk et al., 2010). Despite the difficulty of structuring the ideation work, it can be done in a disciplined way. The following stand as good practices: keeping old ideas on track and following up on the progress, envisioning new purposes for old ideas, as well as developing proof of concepts (Hargadon & Sutton, 2000).

Strategy & Early Checks

While the ideation stage tackles the issue of “what” the strategy and early checks address the “how”. The stage at this point is split into three main constructs: understanding the concepts, selecting the most appropriate ones and identifying resources needed, and deciding how the innovation should be managed (Tidd et al., 1997). The raw material for the strategy

16 development process is information. At this point, a generated proof of concept needs to be evaluated. A fundamental part of the strategy development process is agreeing on what the organization envisions for the future. That said, at this stage is fundamental to embrace the organizational strategy. An important strategy tool for this stage is to design roadmaps (Phaal et al., 2004).

Resources Allocation

Between drawing up the strategy & early checks and implementing the concepts, there is an important step of defining which resources will be needed for the development of the innovation endeavor. At this stage, the organization defines if the endeavor can be developed in-house or outsourced. This type of decision has to do with the organization strategy in the sense of transferring the innovation development into, for example, internal know-how. The exitance of multiple sources of knowledge needed to innovate and oftentimes the challenge of managing the endeavor internally make the case for further collaboration not only within the boundaries of the organization but also externally (Powell, 1998).

Implementation

Implementation is the stage in which ideas are turned into final concepts. Strategies and resources are combined to make the innovation attempt occur (Tidd et al., 1997). This stage is also highly intense in terms of cross-functional coordination as it still stands for achieving problem-solving. Nagano et al. (2014) elaborate more on the problem-solving duties and claim the importance of experimentation as part of the process of turning an idea into a solution (Nagano et al., 2014). In the line of Nagano et al. (2014), Cooper (2009) brings a perspective from the implementation point of view by claiming this process is oftentimes organized in a gate format. The gate process allows a linear dynamic in which every gate is initiated as long as the previous one reports meeting the minimum requirements. Otherwise, it should be reoriented (Cooper, 2009).

Monitoring and Evaluation

As for Cordero (1990), the innovation performance needs to be measured, monitored, and evaluated. This performance indicator needs to be constantly analyzed so the organization can enhance its innovation process on an ongoing basis (Cordero, 1990). Nagano et al. (2014) identify two aspects concerning the monitoring and evaluation process: i) Evaluating results

17 and bringing lessons learned to the knowledge flow in the organization; ii) Monitoring the implementation to identify opportunities for improvement (Nagano et al., 2014). The first aspect stands for the best practices that aim for the monitoring stage of the project after being launched. This is an ongoing activity that enables the organization to gain lessons learned from previous endeavors (Koners & Goffin, 2007). The second aspect concerns the evaluation dimension and stands for the indicators that allow the monitoring of the performance (Nagano et al., 2014).

2.2 Digital Tool Usages

2.2.1 Digital Tools Usage Definition

The informed uses of digital competence within life and work-related situations are called digital usages. These involve using digital tools to seek, find and process information, and then to develop a product or solution addressing the task or problem (Martin & Grudziecki, 2006).

2.2.2 The Role of Digital Tools Usages

The digital tools usage phenomenon has been increasingly caught the attention of innovation researchers (Verstegen et al., 2019), and explored from the perspective of use and implementation of digital tools to nurture the innovation activity of companies (Yoo et al., 2012).

Mainstream studies recognize that information technology, and more importantly, digital tools, play a major role in the way individuals interact, communicate and collaborate (Hinds and Kiesler 2002). Practitioners and researchers have revealed that these digital tools are the core factor to make “information” as explicit and effective as possible (Maiolini et al., 2016). Regardless of the physical or distant employees can readily exchange any sort of information as sheets, reports, documents, events, drawings, critics, suggestions, schedules, opinions, and else (Kiesler & Cummings, 2002). As for Burton-Jones and Gallivan (2007) organization of digital tools usage involves the coordination of interactions by individual actors, working towards collective-level goals through performing interdependent tasks (Burton-Jones and Gallivan, 2007). It may include benefits, such as increased revenue or reduced workload, as well as flexibility in creative design (Boland et al., 2007). Digital tools can be combined to

18

generate new usage potential (Henfridsson et al., 2018), activating new ways of fostering innovation. (Boland et al., 2007). As a fact, people are often eager to use new digital tools in their work duties when they perceive these tools bring additional value to their tasks (Leonardi, 2011), and positively affect the coordination of work within the organization (Barley, 1990).

Digitals tools can significantly increase users’ problem-solving capacity and enhance their communication and interaction, as well as hold the promise of faster, better, cheaper

(Thomke, 2006). But that potential should be tempered by understanding that the rate of technological change often exceeds that of behavioral change. Nambisan and Baron (2019) also raise awareness about extended costs that adaptation to digital tools involves. That said, additional efforts in terms of immersion, adaptation, and learning are expected to be managed so individuals successfully embrace the digital change (Nambisan and Baron, 2019). Thomke (2006) exemplifies this challenge from the perspective of interfaces iterative problem solving which oftentimes involves different organizational units. For the process to successfully work, these efforts must be coordinated. The same author also pointed out that when the knowledge flow of an organization is dependent on a single digital tool, it takes time for the employees to disclose what they know. That said, the expected change through digital tool usages does not occur overnight (Thomke, 2006).

2.3 Innovation Culture

2.3.1 Definition of Innovation Culture

Innovation culture is defined as a multidimensional setting that includes the shared values, assumptions, and beliefs of the members of an organization that enables the exploration of new opportunities and knowledge and generates innovation (Naranjo-Valencia & Hernández, 2018). Sattayaraksa and Boon-Itt (2016) expand on Naranjo-Valencia and Calderon-Hernandez’s definition and bring the importance of facilitating the employees’ innovative behaviors (Sattayaraksa & Boon-itt, 2016). As an extension of these definitions, Michaelis et al. (2018) expand on the entrepreneurial mindset that facilitates activities including, but not limited to, the pursuit of novel products, services, and/or processes (Michaelis et al., 2018).

19

2.3.2 The Role of Digital Tools and Innovation Culture

The accelerated pace of technology has enabled organizations to with additional means to generate new ideas and share knowledge in a faster way. Therefore, organizations face the challenge of reshaping their digital capabilities and innovation culture to leverage the ability to continue innovating (Bourdeau et al., 2020; Cohen & Ehrlich, 2019; Rujirawanich et al., 2011). Digital tools that have a use within the boundaries of the organization enable the process of exchange of information not only among employees but also across internal units (Bourdeau et al., 2020). Nonetheless, several authors raise awareness about the fact that information exchange is not the only driver for innovation. Existing literature reinforces a claim that states that innovation is the result of coordinated efforts, encouraged habits, and rewarded actions. Therefore, the organization’s values and beliefs stand as an enabler for employees to cultivate exploration, foster idea and knowledge exchange and, successfully accept success and failure (Michaelis et al., 2018; Sattayaraksa & Boon-itt, 2016). To make employees’ efforts more effective, oftentimes digital tools are incorporated to leverage information exchange endeavors so a culture for innovation is stimulated (Kohli & Melville, 2019; Nambisan et al., 2017; Tian et al., 2018). In consequence, innovation-driven organizations not only secure and deliver adequate digital tools to employees but also flourish an organizational environment that embraces innovation (Anderson et al., 2014; Nambisan et al., 2017).

2.4 Middle Managers

2.4.1 Strategic Role of Middle Managers

Middle managers gain their importance by fundamentally managing the key activities and practices to generate and explore new opportunities and mainly retain support within the organizational context. Yet, when there is an incompatibility between the expected and existing work techniques and settings, their judgment and eagerness to change will be highly critical to promote innovation (Krause, 2004). Practically applying a risk-taking attitude, idea sharing, listening to others, and else will determine the overall level of innovative behavior and individual creativity (Krause, 2004; Mumford et al., 2002; Taghipour & Dezfuli, 2013).

Under fixed conditions, middle managers are positioned as a mediator of the top-level management within the innovative nature of organizations (Amo, 2006). Due to their high

20

range of connection with the different layers of the organization, they could readily be way more interacted and involved within the innovative processes, therefore, this situation leads positioning themselves in the middle of the idea and creativeness flow, thereby, they are the primary source of the creation, implementation, and control of the innovative ideas and behaviors (Ong et al., 2003)

To more effectively and smoothly encourage and empower the individuals, (Robson & Tourish (2005) suggested that, the greater usage of internal communications as face-to-face meetings, improved email communication and newsletter, more appreciation and openness, better listening and interaction, and most importantly communication training are the core elements. While tackling either physical or remote internal communication, these elements should be promoted by especially the middle managers (Robson & Tourish, 2005).

2.4.2 Leadership for Innovation

Rosing et al., (2011) point out that a combination of different leadership styles with the ability to be adjusted to the situation is needed to successfully tackle the complex nature of innovation creation and development. Many organizations’ attempt for a smooth transition to a digital business model requires more employees’ participation to contribute positively to a digital business value chain (Haddud & McAllen, 2018). It is suggested that leaders should develop an environment that is deeply functionalized by innovativeness to readily encourage team members and boost their willingness and motivation to be involved in innovation processes, and subsequently develop innovative perspective and behavior in the digital workplace (Kör et al., 2021). When it comes to the innovation process and its implications for leadership behaviors, it is mostly the aim of a leader to increase exploration and reduce exploitation variances depending on the situation within followers' behavior. This ability to adjust leadership behaviors in a flexible way or even goes beyond this by concerning a balance between exploration and exploitation to successfully promote innovation (Rosing et al., 2011). Moreover, an innovative environment should collaboratively be operated with the digital technologies where these digital technologies have precisely explained as from e-mail, instant

messaging, and enterprise social media tools to human resources applications and virtual meeting tools (Deloitte, 2012). Alongside providing necessary training for individuals who will have direct or indirect interaction and interest with the digital technologies, leaders also monitor and review the occasional feedback processes to have in-depth insights and ideas

21

regarding how these digital tools are operated and what are the individuals’ experience and reaction through them (Haddud & McAllen, 2018).

Even though some of the researchers have touched upon the importance of managerial support in innovation processes (i.e.: Veenker et al. 2008), instead of diving deep into the importance of the middle or operational level management (Chuang et al., 2011), the main focus on the literature was mostly about the executive side of the leadership which contains top, strategic, or C-level leaders and their management practices. Nowadays, what should not be overlooked is the major role of the middle and operational-level managers and inherently their perspective through the innovation processes and individual creativity (Deegahawature, 2014).

22

3 Method

This section discusses the interpretive research philosophy and inductive approach to theory development highlighting the exploratory nature of this study. In pursuit of consistency with these elements, it is bridged the relationship with the qualitative exploratory methodological choice in the line of a case study research strategy. Furthermore, it is described the empirical setting, as well as the data collection and analysis in compliance with the research trustworthiness and code of ethics followed by this research.

23

3.1 Research Philosophy and Approach

Research philosophy refers to systems of beliefs and assumptions about the development of knowledge (Saunders et al., 2016). Johnson and Clark (2006) note that researchers need to be aware of the philosophical commitments made through the choice of research strategy, as this shapes the whole research (Johnson and Clark, 2006). Three major reasons led researchers to adopt an interpretive research philosophy for this case study, assuming an ontology from a socially constructed perspective as well as an epistemological focus based on perceptions and interpretations. First, this study takes middle managers as a unit of analysis to investigate the research question which implies that the primary source of data comes from the ground setting where the phenomenon subject of study occurs. Second, researchers are highly engaged in the collection and interpretation of data which brings some sort of subjectivism to the research. Third, the research dynamic is pretty reflexive based on the meanings that researchers give to the inputs of the interviews. Therefore, interpretivism makes the case as an assumption for the reality, acceptable knowledge, and values of this research. As an approach to theory development, this study adopts an inductive approach. Therefore, this research intends to develop knowledge by making sense of the meanings expressed by middle level-managers in the line of Saunders et al. (2016), who points out that an inductive approach is intended to allow meanings to emerge from data to identify patterns and relationships to build a theory –without preventing the use of existing theory to formulate the research– (Saunders et al., 2016).

3.2 Methodological Choice

Qualitative research studies participants’ meanings and the relationships between them, using a variety of data collection techniques and analytical procedures, to develop a conceptual framework and theoretical contribution (Saunders et al., 2016). Therefore, it is adopted as a qualitative research method with the ultimate goal of contributing to theory and practice by developing a framework that opens up the process improvement ‘black box’, as stated in the introduction. This methodological selection proves alignment with the research philosophy as qualitative research is often associated with an interpretive philosophy (Denzin and Lincoln, 2011). This study is also exploratory in nature as the researchers aim to gain insights about the topic subject of research through literature search and investigations in the field. As for Saunders et al. (2016), exploratory research is flexible and adaptable to change and enables

24 researchers to change direction as a result of new data that appear. This point is particularly relevant for the research strategy, as outlined in section 3.3.

3.3 Research Strategy

3.3.1 Case Study

As for Yin (2018), a case study investigates a contemporary phenomenon (case) in-depth and within its real-world context (Yin, 2018). Sekaran and Bougie (2013) point out that a case study is concerned with the meanings people bring to a subject matter in a natural environment. A single case study is an in-depth analysis within a small number of units, gathering information “about a specific object, event or activity, such as a particular business unit or organization.” (Sekaran and Bougie, 2013. p.103). Since this study employs the perceptions and interpretations of middle managers to investigate a “how” towards the aim of this research, and to limited to the contextual operational organizational level, it is used as a single case study as the main research strategy. This choice is appropriate as case studies primarily concern a ‘how’ or ‘why’ question about a contemporary set of events, over which researchers have little or no control (Yin, 2108). As for Yin (2018), despite some typical weaknesses of this methodological approach that deal mainly with selection bias, case studies have numerous upsides such as:

▪ Depth of the analysis: particularly because of using the empirical lenses of middle managers who know the technical complexity behind the phenomenon of digital tools usages at the implementation level, this case study brings insightful information beyond what is visible at the surface level.

▪ High conceptual validity: by diving into the operational level, this case study explores the heart of the organization so data collected from middle managers is well-grounded and provides a high level of quality and meaningfulness.

▪ Understanding of context and process: researchers took the wise decision of giving relevance to the use of digital tools at the process level to gather in-depth inputs. The following are examples of questions that address this dimension: i) Can you give me an

25 example of the output that these digital tools bring to your internal innovation process?; ii) How do these digital tools are integrated within your internal innovation processes? ▪ Fostering new research questions: this case study sticks and commits with one research question through a single case study so it deepens the analysis and comprehension of a particular context. Based on this contextual immersion at the operational level, this research can suggest future research avenues with a broader scope and beyond this organizational level.

Last but not least, one more reason for selecting a case study as a research strategy is because being compatible with the grounded theory, enabling all data to be analyzed towards answering the research question.

3.3.2 Grounded Theory

In pursuit of consistency with the exploratory nature and inductive approach of this study, a grounded theory is used to organize, process, and analyze the data collected. The heart of the grounded theory is engaging a phenomenon from the perspective of those living it. This engagement with those living the phenomenon and attempting to understand it from their perspective is why grounded theory is such a powerful approach for gaining new theoretical insights and pulling back the curtain on the complexities of modern life (Corley, 2015). Corley’s argument stands as the major reason why the grounded theory was selected as a strategy to analyze the data and develop the theory. As previously explained, this case study aims in-depth understanding of the organizational context and process level through the eyes of the ones dealing with the complexity of backstage. As for Easterby-Smith et al. (2018), authors like Glaser (1992) imply that the researchers need to approach the research work with no preconceptions and should let the insights emerge from the data. In contrast, authors like Corbin and Strauss suggest getting familiar in advance with the field of research to support the process of making sense of the data. As an extension to this debate, Charmaz (2000) questions these approaches by implying a separation of the researchers from the experience subject of investigation. In consequence, Charmaz (2000) proposes a more constructionist perspective in which viewers (researchers) generate the data and ensure analysis through interaction with the viewed Charmaz, 2000). As for Corley (2015), the power of grounded theory is partly derived from the potential to let those closest to the phenomenon influence how it is studied (Corley, 2015). In this sense, and consistent with the exploratory nature of this study, researchers adopt

26 a grounded theory approach aligned with Charmaz and Corley’s viewpoint. This choice proves also alignment with the interpretative research approach and selection of a case study to immerse in the operational context in a hand-by-hand interaction with middle managers.

3.4 Empirical Setting

According to the Innovation Maturity Index 2019, organizations still view innovation as an ad-hoc “creative” process. But real innovation requires a persistent effort, well-defined processes, and true commitment (Accenture, 2019). That is way, this research concerns the way internal innovation processes are enhanced with digital tool usages in a global pharmaceutical company committed to revitalizing its research and development operation model (Idrus, 2020). The selected organization is currently in a cultural transformation process which the Chief Executive Officer claimed as an overall strategy alteration across continents where every single individual should be involved and contributed. The main stages are reinventing the way of work, leading with innovation, enhancing efficiency, and focusing on growth. Furthermore, researchers believe that the liaison between remote working and the health industry within the pandemic period would be deeply interesting to explore any changing methods and procedures conducted by the middle managers. A middle manager was defined as an individual with at least 5 years of relatable experience and currently responsible for the management of a team at the operational level. Researchers selected 10 participants out of 50 middle managers (in the same level) mainly from Turkish Headquarters. Last but not least, after carefully making sure that the main variables, parameters, and dynamics would fit our research philosophy and approach, and method, researchers decided to proceed with this organization.

3.4.1 Sample Selection: Snowball Sampling

The sample selected concerns the population subject of research. Consequently, the researcher may redefine the population as something more manageable. (Saunders et al., 2016). As this research employs middle managers within a single Company (the Case) as the source of empirical material, it is selected a non-probability sampling. As for Saunders et al. (2016), case study research does not have a sampling frame which means that the sample must be selected through non-probability sampling.

27 As outlined in the delimitations section of this paper, this research employs the empirical lenses of middle managers currently working at a globally operating pharmaceutical company. Due to the large size of the Company, individual cases were difficult to identify and reach. That is why, researchers managed to gain interest in the topic subject of this study within a business unit in the Turkish Headquarters. That said, a point person with a key role in the digital side, was first approached to be interviewed. Consequently, this point person referred subsequent interviewees with the potential of bringing insightful inputs about internal process and development, digital management, among other roles with relevance for this research. That way, researchers employed the snowball sampling procedure to gradually reach and bring the perspective of middle managers with a high correlation to the approach of this research.

Sample-wise, researchers managed to have representation of 3 different units including the Business Operations, various business units (medical units), as well as cross-functional roles at Turkish Headquarters (some include France, Iran & Levant). Researchers found the cross-functional roles relevant for the nature of the research to gain insights from managers supporting different operations across the organization. The sample included inputs from Human Resource to Digital Governance and even from Data Management to Internal Control and Process departments. However, to keep participants’ identities anonymous, their position within the organization was renamed as shown in appendix 1.

3.4.2 Data Collection: In-Depth Semi-Structured Interviews

The empirical data for this case study was collected using an in-depth semi-structured interview protocol (see appendix 2). By conducting this type of interview researchers got the opportunity to clarify responses and expand on points of interest in pursuit of a better understanding of the interviewees’ insights. The protocol was carefully designed to smoothly immerse interviewees into the topic, relate each question to their personal experience, as well as to give them the freedom to freely express themselves. To do so, the protocol was divided into 4 stages. First, a welcoming greeting and interview consent highlighting the interviewees' right to privacy and anonymity. Second, general questions on innovation perception within the company subject of analysis touching at the research constructs at the surface level. Third and fourth covered in-depth open-ended questions relevant to the three (3) constructs of the study’s

28 research question. Researchers carefully listened to the opinions, positions, and thoughts expressed by the middle managers interviewed as part of the data collection phase.

To absorb the most detailed insights from the interviews and ensure data reliability, the interview material was recorded, in compliance with the interviewer’s consent, and transcribed to facilitate the analysis of the material as part of the grounded theory coding process. That said, researchers acknowledge that interpretations derived from the empirical data comply with high levels of quality and reliability. As outlined in the delimitations section of this paper, the Covid situation forced researchers to conduct interviews remotely. However, researchers managed to leverage digital tools like Zoom, as well as recording features to gather the most detailed insights from the interview material. That said, a total of 11 hours of interview material was collected from 10 interviewees.

3.5 Data Analysis Procedure

In the line of the research inductive approach and strategy, grounded theory was used to review the data collected. The data analysis procedure began with the raw empirical data collected by immediately transcribing the audio recorded after every single interview. That way, researchers managed to capture the best of the raw data and also ensuring high quality and fidelity of the inputs provided by the middle managers. Despite the round of interviews was developed in an intense period of 2 weeks, researchers also managed to start highlighting pieces of the interview with high relevant insights for the research. The coding itself, in a rigorous way (initial coding), started right after all of the interviews were conducted. This process involved an initial coding developed by extracting detailed chunks from the data and generating a set of records in an Excel file which can be provided upon request. This initial coding included a process of contrasting the codes to find repeated or similar ideas that derived in the construction of the rich codes. This way the analysis became more profound and, in consequence, codes became more detailed. As for Easterby-Smith et al. (2018), and in the line of Glaser & Strauss (1967), the second stage in coding is the restriction of the initial set of coding categories. Then, the process of coding and analysis of empirical data can be more selective and focused. In the line of this approach, the codes were categorized into categories, contributing to making sense of what interviewees meant, as well as bringing narrower perspectives towards the generation of meaningful themes. The data was re-reviewed (iteration) to make sure that

29 no additional data could be found to develop new categories. The output of this iterative process will represent the foundations for opening up the process improvement ‘black box’ and the development of a conceptual framework.

3.6 Trustworthiness

To guarantee a high level of reliability, examination of trustworthiness is fundamental in qualitative studies. Within the research methods literature, the concepts of reliability and validity are essential criteria for quality in quantitative paradigms. However, in qualitative research, the terms credibility, confirmability, dependability, and transferability embrace better the criteria for quality in this type of research (Golafshani, 2015).

3.6.1 Credibility

Credibility refers to the truth of the data and the interpre-tation and representation of them by the researcher (Cope, 2014). Credibility is enhanced by the researcher describing his or her experiences as a researcher and verifying the research findings with the participants. A qualitative study is considered credible if the descriptions of human experience are immediately recognized by individuals that share the same experience (Sandelowski, 1986). Since this case study adopts an epistemology from a socially constructed perspective, researchers used the method of triangulation to record the construction of reality based on close interaction with the interviewees. This interaction was supported by the in-depth process that both the semi-structured interviews allow, as well as in the data analysis through the iterative process that the grounded theory enables.

3.6.2 Confirmability

Confirmability, also known as neutrality, refers to the researcher’s ability to demonstrate that the data represent the interviewees’ responses and meanings and not the researcher’s biased perspectives (Tobin & Begley, 2004). To demonstrate that the meanings and interpretations were well-grounded and derived from what interviewees claimed, the empirical findings of this study are presented and supported based on rich quotes from the middle managers interviewed.

30

3.6.3 Dependability

Dependability, also known as consistency, refers to the constancy of the data over similar conditions (Tobin & Begley, 2004). As for Yin (2018), it is inappropriate to generalize case studies to a population, and eligible to generalize it to theory. Therefore, it is not the aim of this research to suggest the existence of a black and white attempt from middle managers to enhance internal innovation processes with digital usages. Instead, this case study shows an attempt from middle managers which could be contrasted with similar case studies in the field.

3.6.4 Transferability

Transferability, also known as applicability, refers to findings that can be applied to other settings or groups (Cope, 2014). As stated in the previous point, the theory is built based on the attempt of middle managers. It is also part of this study to acknowledge what this case study reconfirms from the existing theory, as well as the elements that could be understood as an extension of the existing literature.

3.7 Research Ethics

In pursuit of trustworthiness as part of this case study, researchers carefully followed a set of ethical codes and principles commonly adopted under business and management research. As for Easterby-Smith et al. (2018), and in the line of Bell and Bryman (2007), this is mainly intended to guarantee the right protection of research participants as well as the integrity of the research community. For the purpose of this case study, the research participants refer to the group of 10 middle managers interviewed as part of the empirical fieldwork, and the community refers to the organization itself subject of this study. The following actions describe the ways researchers applied this set of ethical codes:

▪ Protection of research participants: since the beginning researchers managed to develop a relationship with a point person within the organization so the first approach to all of the remaining 9 interviewees occurred through this person. That way, researchers ensured that no one was harmed by respecting interviewees' availability, time preference, and online environment (platform) to be interviewed. Therefore, all of the interactions with the middle managers were performed in a highly professional way.

31 As a result, both interviews and researchers developed a dialogue with respect and ensuring dignity for both parties.

▪ Protection of the integrity of the research community: As stated in the previous point, one of the researchers conducted a kick-off online session with the point person in the organization to explain the purpose of the research and the scope of the case study. By pointing out the exploratory nature of this research, it was agreed to interact exclusively with middle managers as a unit of analysis. That way, it was clear for both parties that the outcome of the research would be rooted in an exploratory case focused on the aforementioned target of managers. Researchers also acknowledge that this study concerns an academic-related interest with no other motivation or affiliation that could represent a conflict of interest.

As an extension of the above-mentioned protection of rights, researchers carefully ensured the right to privacy, confidentiality, and anonymity through an informed consent (stage 1) that served as an opening for every single interview, as depicted in appendix 2. All of the interviews followed the same interview protocol so stage 2 was not reached until researchers got informed consent from the interviewees. The protection of these rights was ensured not only at the data collection phase but also through the whole research process. Furthermore, any verbal and written reporting of empirical findings and research, in general, was managed with honesty and transparency avoiding any misleading information. An example of this way to proceed is this manuscript which is a representation of how the code of ethics was adopted.

32

4 Empirical Findings

This section reports the major empirical findings of this case study. By going through the codes to categories and themes in the line of the grounded theory, it is elaborated analysis supported by direct and rich quotes that prove reliability on the interpretation of findings. The content of this section represents the foundations for further discussion and contribution to theory and practice.

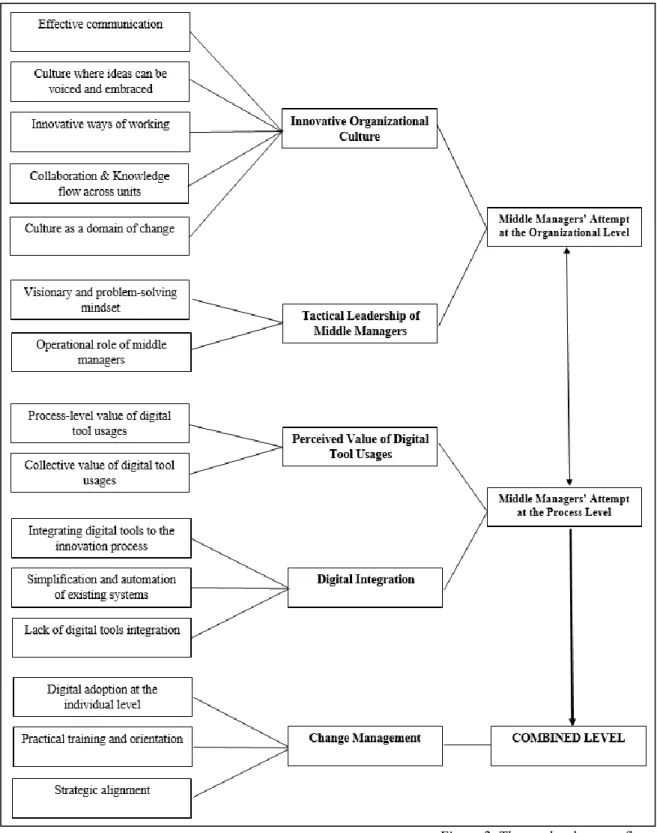

33 As described in the data analysis subsection, a 2-stage grounded theory procedure was developed to inductively generate the theory based on the data collected. This iterative procedure enabled researchers to narrow down the set of codes from 40 to 15. This set of 15 codes was carefully selected as the most accurate representation of the meanings expressed by the interviewees. Despite some sort of overlapping between some codes (i.e.: meanings that might relate to innovation culture or leadership for innovation), researchers managed to make sense of categories that successfully embraced the group of codes towards the answer of the research question. Then, the criteria to define the themes was led by the 2-level of analysis defined in the research purpose: process and organizational levels. For a better understanding of this reasoning it is presented below a theory development flow (see figure 2) that shows, on the left side, the set of 15 codes followed by the 5 categories that embrace every single coding group, as follows: 1. Innovative organizational culture, and 2. Tactical leadership of middle managers, falling into the theme of middle managers’ attempt at the organizational level. Then, 3. The perceived value of digital tools, and 4. Digital integration, falling into the theme of middle managers’ attempt at the process level. Finally, 5. Change Management, emerging from the articulation of the process and organizational level, and standing as the combined

34 Figure 2. Theory development flow

35

4.1 Middle Managers’ Attempt at the Organizational Level

Middle managers' attempt to enhance internal innovation processes with digital tool usages involves two major organizational-related categories clustered as innovative organizational culture and tactical leadership of middle managers. These 2 categories stand as the heart of the organizational level attempt and explain pivotal elements related to innovation culture and leadership that impact the internal innovation processes with the support of digital tool usages.

4.1.1 Innovative Organizational Culture

In an organizational structure, culture is the most variable asset embedded in layers of an organization. No matter what sorts of dynamics that any culture has, it is identified 5 different ways to connect the nature of organizational culture with managerial acts. By doing that, it can be outlined the critical position of the individuals and enlighten the fact that why any kind of change starts from and depends on the individual level.

4.1.1.1 Effective Communication

When it was asked our research question to ourselves, communication was the most obvious possible answer in our minds. But after analyzing participants’ notions, some interesting findings emphasize the substantial position that the element of communication has within the organizational culture. “Communication is a seriously classic element in a corporate market. When there is a problem anywhere, it occurs due to the lack of communication, the right way to express and explain is the key” (INT3). With remote working, the role of face-to-face communication is mostly recognized by the managers whenever they want to listen, explain, discuss, or evaluate anything with team members. However, due to the increasing frequency of meetings, none of the managers can maintain a prior relationship with their team members. “I created Microsoft Teams channel where every team-specific communication is carried out and also one-to-one channels for every member to reach out to me or I reach out to them any time” (INT6). “For the times when you cannot organize a meeting due to the busy schedules, we apply WhatsApp’s assistance for sharing private, not-work-related things, or brainstorming, shortly, to have more informal conversations”(INT1). That proves, managers

36 realized the fact that they should tackle this lack of communication as soon as they can to become aware of team members’ wellbeing and performance. During these challenging days where the connection between people is missing, individuals’ well-being is being the hottest topic for the organizations and managers try to be more intense about their interaction with the assistance of digital tools. Digital tool usages play an effective role here with their collaborative nature. Managers use collaborative tools to interact with their followers by using organizational tools such as Microsoft Teams or Zoom, on top of that, they also use way more personal tools such as WhatsApp. “I make sure to maintain a mutual communication with my team: we set up weekly one-to-one meetings constantly and within these meetings, an additional thing that I want from a team member is to generate feedback about me, team, or anything that they think went positive or negative throughout that week” (INT4). To get rid of the tunnel vision which every person might fall into, managers should also listen to their followers carefully and ask relatable questions to understand and recognize any possible threats, issues, or opportunities.

4.1.1.2 Culture Where Ideas Can Be Voiced and Embraced

After touching upon the fragile cultural factors belonging to the organization, there are some steps to efficiently use these independent and diversified organizational layers. The first step depends on the organizational level as top management by creating and supporting an open and flexible environment where individuals can bring any idea and perspective without hesitating thus, the essence of the innovative ideas can flourish. The second step is highly dependent on middle managers due to their critical position between the top level and their followers. To make it possible we identified two main strategies as (1) Give your team a maximum level of freedom and support “which pushes them to try something new fearlessly” (INT2). (2) Let people do and encourage them by giving activities to perform in real life, then “this attitude will bring internal and external discussion, collaboration, cross-functionality, and exchanging of thoughts” (INT10).

After analyzing the data, it was found that this open community or environment could be used as a major problem-solver when every individual of the company is involved with a different opinion and makes their contribution. “The wider and more diverse ideas and points of view you can bring to the table, the better the solutions are” (INT2). However, when miscellaneous ideas are voiced, organizations should also embrace them. Our case company initiated one event where innovative projects are presented regarding the pharmaceutical