' '

•. .

..

ACCEPTED PRINCIPLES

OF THERAPEUTIC PROCEDURE

AND THEIR APPLICATION

TO MUSIC THERAPY

SISTER M. JOSEPHA, 0. S. F.

DE PAUL UNIVERSITY

ACCEPTED PRINCIPLES OF THERAPEUTIC PROCEDURE AND THEIR APPLICATION TO MUSIC THERAPY

A DISSERTATION

SUBMIT'rim TO T":BE GRADUATE FACULTY IN PART FULFILLMENT

OF THE REQUIREMENTS

FOR THE

DEGREE OF Mi$TER OF MUSIC DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC EDUCATION

BY

©

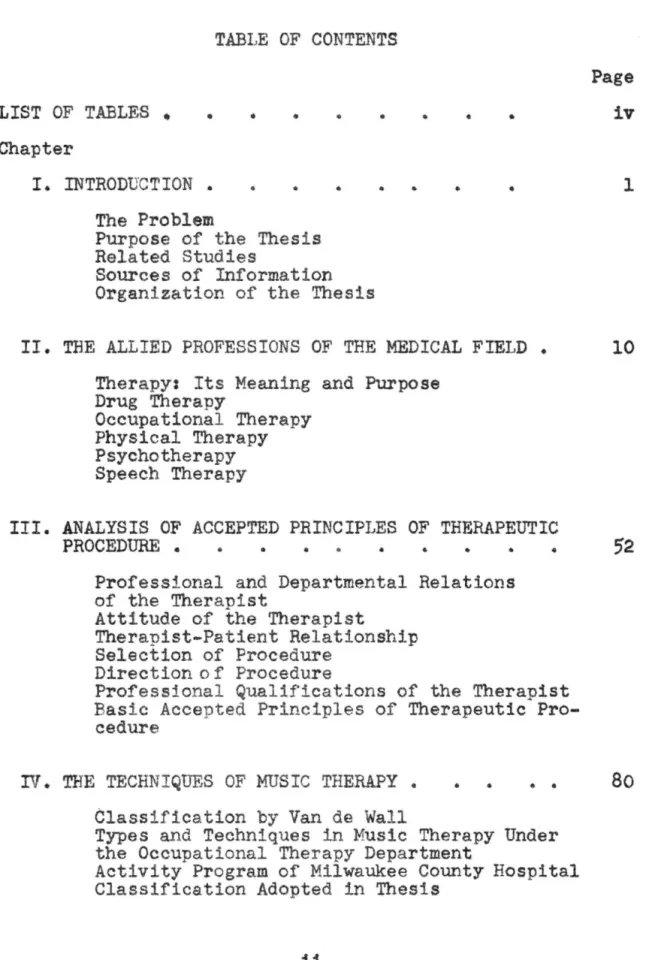

1960 by Alverno College, Milwaukee 15~ Wts:::onsinTABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES • Chapter •

I.

INTRODUCTION • The Problem • • • •Purpose of the Thesis Related Studies

•

•

Sources of Information Organization of the Thesis

• • • •. • • • • Page iv 1

II. THE ALLIED PROFESSIONS OF THE MEDICAL FIELD • 10

Therapy: Its Meaning and Purpose Drug Therapy

Occupational Therapy Physical Therapy Psychotherapy Speech Therapy

III. ANALYSIS OF ACCEPTED PRINCIPLES OF THERAPEUTIC

PROCEDURE • • • • • • • • • •

52

Professional and Departmental Relationsof the Therapist

Attitude of the Therapist

Therapist-Patient Relationship Selection of Procedure

Direction of Procedure

Professional Qualifications of the Therapist Basic Accepted Principles of Therapeutic Pro-cedure

r:v.

THE TECHNIQUES OF MUSIC THERAPY • • • • •Classification by Van de Wall

Types and Techniques in Music Therapy Under the Occupational Therapy Department

Activity Program of Milwaukee County Hospital Classification Adopted in Thesis

11

Chapter

V. APPLICATION OF BASIC ACCEPTED PRINCIPLES OF

THERAPEUTIC PROCEDURE TO THE TECHNIQUES OF

MUSIC THERAPY •

Professional and Denartmental Relations of

the Therapist ··

Attitude of the Therapist

Therapist-Patient Relationship Selection of Procedure

D:i.rection. cf Procedure

•

Professtonal Qualifications of the Therapist

VI. SUMMARY • • BIBLIOGRAPHY • • • iii Page 84 110 114

LIST OF TABLES

Table

1. Frequency of Principles of Therapeutic Proce-dure in the Literature on Drug Therapy • • 2. Frequency of Principles of Therapeutic

Proce-du·re in the Ltterature on Occupational Therapy

3.

Frequency of Principles of Therapeutic Proce-dure in the L.iterature on Physical Therapy •4.

Frequency of Principles of Therapeutic Proce-dure in the Literature on Psychotherapy • •5.

Frequency of Principles of Therapeutic Proce-dure in _ the Literature on Speech Therapy • 6. Currently Accepted Principlesof

TherapeuticProcedure: A. Professional and Departmental Relations of the Therapist • • • •

?.

Currently Accepted Principles of Therapeutic Procedure: B. Attitude of the 'l'herapist •8.

Currently Accepted Principles of Therapeutic Procedure:c.

Therapist-Patient Relationship9.

Currently Accepted Principles of Therapeutic Procedure: D. Selection of Procedure • • 10. Currently Accepted Pri.nciples of Therapeutic Procedure: E. Direction of Procedure • •11. Currently Accepted Principles of Therapeutic Procedure: F. Professional Qualifications of the Therapist e • • • • • • iv Page •

16

•26

•32

•l+l

• >+7 • •57

• 61•

•71

• ?6CHAPTER

IINTRODUCTION

Great impetus was given to the use of music in hospitals during World War II when an attempt was made

to alleviate the mental and physical sufferings of the war-injured by the provision of musical entertainment for the patients. Volunteer services of both profes-sional and amateur musicians and musical ·groups were solicited. Willem Van de Wall writes: 11Patients

ea-gerly asked for music, hospital doors were wide open for those who wanted to come and sing and play, and the :musicians streamed in to render whatever service they

saw

fitto

give.nlDuring this second World War the Armed Services also showed great interest in the use of music as treat-ment in the occupational therapy departtreat-ment.

In

1945

the N'ational Music Council set up a rather comprehensive pro-gram of music therapy.1. Objecti·, e - The objective of music in

re-conditioning is to integrate music with. the four main reconditioning activities, namely, physical training, education and orientation, occupational therapy, and diversional activities.

lw111em Van de Wall, Music in Hospitals, p.

8.

New York: Russell Sage Foundation,

1946.

12. Personnel

a. At least two music technicians, enlisted men of the hospital detachment, are nec-essary in each General Hospital. They function under the Reconditioning Educa-tion Officer.

b. The success of the program lies largely in the vision, initiative, adjustability, cooperation, willingness and music_anship of the personnel assigned to music. Care is taken in finding the right men for this

work.

3.

Program2

a. Participation by Surgical and Medical Patients

Music orkshop, orchestra, small instrumentsj group s1nging1 chorus, music with calisthenics b. Listening by surgical and Medical Patients

A room for music appreciation, records,

Lt-brary, balanced recorded programs over public address system, contact with symph ny orches-tras, etc.

(Participation is prescribed by medical

of-ficer)4.

Neuro-Psychiatric Section a. Participationb. Listening

;. Participation by all patients

6. Orientation lectures

? • Libr.~ry

8. Advertising of musical activities to patients)

9.

Recreational music for persons free. frommedi-cal treatmentl.

It ·is not to be assumed that this ras "tie fil"'"'t

introduction of music into hospitals. Histor · dates. th~ use of music 1n healing to ancient times and~_although the

use of music for illness remained in .a .s.tatic . position

throughout the centuries, modern inven

ion

and bot,h WorldlDoris Soibelman, ra eutic and Industria Uses of Mus~c, p.

i;3.

New York: Columbia. University Press, 18.

3

War I

and World War II contributed to the rapid expansion of' the hospital music program. The title, "music thera-pist," however, seemed to grow out of the numerous activ-ities that were carried on in Veterans' Hospitals duringWorld

War

II, since at that time the title was adopted byalmost every type of hospital music worker.

Th~ so-called "music therapist" has been in many

instances , a trained occupational therapist, but sometimes ne has been a professional musiciai.1, supervised by any one

of the several departments in the hospital organization. It was discovered, in a recent ctivity Survey of the American Occupational Therapy Association, that music was among the several activities that were frequently

con-~ucted by departments other than the occupational therapy

department. This raised the question as to taiether the occupational therapist should be trained to take care

or

music therapy om efficiently or whether this field of

therapy should be left to specialists in musicol It seems

that the second alternative is the preferable one,

pro-vided the music:!.an has had the same medical formation which the occupational therapist has received. In that

case the title , 11..iiusic therapist,.n would have signifi-cance.

lnActivity Survey Report of the Education Office of .the .American Occupational 1~1erapy Association for the

Year 194-8,"

.P•11.

New Yorks American Occupational TherapyThe de s:l.r ability of music therapy as a specialty

of its own has been stressed by a recent survey of the

Wisconsin Hospitals, conducted for the National Associa-t i on for Music Therapy under Associa-the auspices of Associa-the Milwaukee County Hospital for Mental Diseases.

The duties of the individual conducting t he music program are vague and the demands are var-i ed , obvvar-iously due to the var-incvar-ipvar-ient character of t he field. The fundamental need that present s i t self to us is the establishment of music thera-py as a recognized profession with similar high st andards of qualification in preparation and t rai ni ng, as are found in the medical and alli ed prof essions.1

The survey, The Use of Music in Hospitals for

Mental and Nervou~ DiseasE?..§., ma.de by the National Music

Council in

1941+,

revealed two outstanding practical needs in music therapy: first, "The medical testing of music as to i ts therapeutic ual:lties,u and second, the devel-opment of standards and curricula for training of quali-fie d personnel by educational institutions on the basisof car eful planning and cooperation with hospitals .112

Although some p~cogress has been made with respect

to the medical testing f ~usic, there is still a defi nite

need for standards of therapeutic proced re.

______________________

...,,_________________________________ ___

lLeo Muskate tr<.!, "Music '11herapy in Wisconsi n

Hospi-tals . " Paper read at the annual convention of the Nat.ional Assoc iation of Music Therap , CL cago, Illinois, November

9,

1951 .2willem Van de Wall, Report on a Survey of the Use of Music in Hospitals for Mental and

Nervous

Diseases,In view of the fact that music has proven

itself an established therapeutic medi.um that reaches a greater number of patients more

ef-fectively than any other modality, it would seem a worthy project to provide researchers so that more effective methods of application may be provided.l

Each of the three sources quoted above recognizes a need for more effective methods of application in the

field of mus:i.c therapy. It would seem that this need could be partially satisfied by a. list of basic

princi-ples of therapeutic procedure to guide the therapist in hj_s administration of music as therapy.

The

purpose of this thesis is to collect, examine, and evaluate the currently accepted principles of thera-peutic procedure and to make deductive application of these principles to the procedures of music therapy.Several published books trace the historical de-velopmen.t and the practices of music therapy in detail.

Among these are Music for Your

He~. tr~,

2 Music in Medicine,34

5

Music and Medicine, and Music in Institution~~ The

lEsther Goetz Gilliland "Present Status and Needs

in Music Therapy, 0 &nerican ...

J:tY.~J9

Teacher.,I(November-December, 1950), 22. ~

,;.Edward Podolsky, Muslc for Your Health, New York: Bernard Ackerman Inc~,

194r.

3

Sidney Licht, 11Y.§J_CL~n r,~, Boston, Massa-chusetts: New England Conservatory of Music, 194-6.l+schullien

&

Schoen, Music and Medicine, New York: Henry Schuman, Inc.,1948.

5willem Van de Wall, Music in Institutjons, New York: Russell Sage Foundation,

1936.

6 volume, Therapeutic and Industrial Uses of Music,l is a

review of the literature in the field. According to the. BipliographY of Research Studies in Mu.sic .Education,

l932-19!t·8,

published by the Music Educators' National Conference, and the list of theses published in theJan-uary and the April-May, 1951 and the April-May, 1952 is-sues of the Music Educators Journal, the investigations in the form of master theses either present the develop-ment of music therapy in a specific disability area or

survey the activities of a particular institution. The

majority of them are concerned with the therapeutic qual-ities of music itself, as evidenced by the following and

similar titles: ''The Therapeutic Value of Music, n2

"Music A.s a Therapeutic,"3 °The Healing Power of Music,"l+

and "Music As an Adjunct to Medical Therapeutics and Prognosis.n5'

lsoibelman, op . cit.

2 Robert Hess, "The Therapeutic Value of Music," Unpublished Master's Thesis, Dep't of Ed., Illinois

Wesleyan University, Bloomington, Illinois, 1938.

3Martha Griffin, "Music As a Therapeutic," Unpub-lished Master's Thesis, Dep't of Ed., Arthur Jordan

Con-servatory of Music, Indianapolis, Indiana,

1945.

4

Arthurw.

Zehetner, "The Healing Power of Music," Unpublished Master's Thesis, Dep't of Ed., Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio, i91;.3.?Hugo Lambach, "Music As an Adjunct to Medical Therapeutics and Prognosis,n Unpublished Master's Thesis, Dep't of Ed., Northwestern University, School of Music,

7

Among thes~, only one bears a title that might

suggest some relationship to the problem of this paper. It was written at the College of the Pacific in Stockton, California, and the problem is stated a; follows: "Some

Principles, Practices and Techniques in Music Therapy.ul This dissertation seems to deal with the principles, prac-tices and techniques of music therapy as already existing while the present study is concerned with enlarging the field of music therapy by adapting and incorporating .into

music therapy the principles

or

therapeutic procedure con-tained 1n the literature of the medically approved associ-ations of Drug Therapy, Occupational Therapy, PhysicalTherapy, Psychotherapy, and Speech Therapy.

The areas of occupational therapy, physical thera-py, psychotherapy, and speech therapy were selected for this investigation because they themselves have accepted music either as a specific therapeutic agent or as a mo-dality for their respective therapy.

Physical therapy includes the use of guided exer-cise. Occupational therapy is exercise through work --purposeful, producti've work with an incentive to produce something useful and to hasten recovery. Music can be of value to both of these groups. Instrumental manipulation 1 Wilhelmina Harbert, "Some Principles, Practices,

and Techniques in Music Therapy," Unpublished Master's Thesis, Dep·' t of Ede , College of the Pacific, Stockton,

can be a means of developing strength and cqord.1nation.

In

addition to the mobilization of joints and muscles, music can also be used to increase the use of the lungs and larynx.18

Psychotherapy 1 a term that is "broader than counseling , meaning the treatment of disorders by psycho-logical me_thods . Strictl y speaki g it can include non-verbal activities uch as the playing of music.tt2

In

speech therapy, the rhythmic patterns of music have often been used to stimulate speech, by promo.ting physical coordination . Patients suffering from dysphonia, stuttering, show a lack of coordination in other functions besides speech. It has been found of great value to them to coordinate their actions to the rhythm of a musical composition.3The area of drug therapy was included in this in-vestigation because music can of ten produce physiologic reactions that are similar in result to the use of drugs. As measured by instruments, music can influence

metabo-lism, respiration, muscular energy, and cardio-vascular functions.

4

lLicht, QP• cit., PP•

45, 47.

2w1111am U. Snyder, "The Present Status of Psycho-therapeutic Counseling," p.

298,

Psychological Bulletin,Vol. XLIV No •.

4.

3s .J·. Wo~lf, "Spee·ch Doctor," New York Times Hagazine, (November, 19~7)

9

The potentialities of music as a therapeutic

agent

have been recognized in these groups of drug, occupationa+, physical, psycho, and speech therapy. Since the basic

considerations underlying therapeutic procedure in these groups have been developed into medically accepted stand-ards of therapeutic procedure, it might be assumeg that the application of these standards to the techniques of music therapy should be an effective means of

establish-ing a science of procedure in music therapy, thereby raising the standards of the so-called music ~herapist.

The technique followed in this investigation is predominantly analytical. The sources are texts, syllabi, periodicals, and bulletins of the various therapy groups and of music therapy.

CHAPTER II

THE ALLIED PROFESSIONS OF THE MEDICAL FIELD

Therapys Its Meaning and Purpose

Therapy signifies treatment. It includes all the means used to aid in the recovery from disease.l This recovery may be complete, as with ordinary diseases and injuries, or it may be only partial, as with many ne,rvous diseases and wasting diseases or the body. When the dis-ease or injury results in the loss of a limb or in some other disability, recovery includes mental and physical compensation and rehabilitation. In many instances, re-covery is conditioned by the psychological adjustment of the individual to the unalterable condition of his parti-cular case.

Whether

the recovery involves complete or partial organic restoration, the real purpose of thetherapeutic treatment is to promote a mental and physical adequacy in the patient.

Treatment may be classified in a general way as

empirical, rational, specific, symptomatic; and supportive.2 laui11 L. Muller and Dorothy E. Dawes Introduction

to

Medical Science, P•319,

Philadelphia:w.!.

SaundersCo., 194$.

2Ib1d., pp.

319, 320.

11 The empirical type of treatment, as experience has shown, makes use of remedies to exert a favorable influence in

similar conditions.

If

the treatment is based upon cor-rect interpretation of symptoms and on an understandingor

the physiologic effect of the remedy employed, it is said to be rational. In some illnesses the treatment ~aycon-sist in the application or administration of a specific remedy, in which case the treatment is also specific. A treatment is supportive if it is directed oward keeping the patient in good condition.

Treatment may also be elassi.fied·according to .the therapeutic medium used, as in physical therapy, occupa-tional therapy, drug therapy, and psychotherapy, or ac-cording to the area of disability in hich it is used, as in speech therapy. Each individual therapy group of this second classification may include any one or more of the types of treatment mentioned in the first or general classification.

Physical therapy will be understood to include light therapy, x-ray therapy, hydrotherapy, fever therapy, and any other of the numerous divisions of the field. Al-though occupational therapy is strictly a part of physical therapy , it will be given separate consideration because of the expansiveness of its program.

The use of any of the drugs developed in the sci-ence of pharmacology will be referred to as drug therapy.

12 Here are also possible

many

subdivisions, such asimmuno-therapy, which is treatment by vaccination, and

substitu-tion therapy, which is the administrasubstitu-tion of endocrine extract as treatment for physical conditions resulting from endocrine dysfunction.

Psychotherapy will be viewed, both as an influence exercised .over the patient by the doctor . and the nurse .. , and as a special form of treatment used in an attempt to remove emotional factors that contribute to some diseases. It appears in such forms as psychoanalysis, non-directive counseling, play therapy, and group therapy.

Speech therapy embraces all the methods of treat-ment that are directed toward speech correction in the otherwise normal person and in the spastic type of pa-tient. It is a firmly established therapy, both ·in the school system and in the hospital. There is no question

or

its importance 1n the total treatment program espe-cially in the area of cerebral palsy conditions.Treatment in each of these various therapy groups has been developed to a high degree of skill and eff

icien-cy. Therefore, each field should have much to contribute to the solution of the problem of this thesis by way of

suggested principles of therapeutic procedure. Because of their medical recognition, these groups have been re-ferred to as the "allied professions" of the medical field.

13

Drug Therapy

The physician prescribes medication, the pharma-cist compounds and dispenses it , but it is ordinarily the nurse who administers it. According to McGuigan and Krug, the administration of medicines is one of the most impor-tant dut ies of the nurse ho, though she never prescribes a medicine, has the responsibility to see that the doctor' s

orde1~s are carri ed out accurately and promptly.J. She

should be able to administer a drug in such a way as t o

insure the best results for the patient. This means that she will have to know something about the drug, the pa-tient, and factors which modify the dosage. These re-quirements for t e proper administration of drugs can be expressed as several principles:

1. Medicine should lways be given under the pre-scription of the phys1cia.tla

2. The doctor's prescription must be followed "exactly. n

3

41 The nu se should be a.ble to recogni.ze themedicine she. 1c administering.

4.

The nurse should know he local and systemic action of the drug in the bodye5.

Caution should be taken to keep within thema.xim1:un and minimum osage of the particu-lar drug.

6. Consideration should be given to all t he factors which tend to modify he dosage.

. lMcGuigan, H. and Krug , E. An Introcluction_ to Materia Medi~a and ·Pharmacologl, p~

80.

St. Louis :7.

The nurse should know the conditionor

the patient.a.

The drug should be administered for a definite therapeutic effect.9.

The procedure of administration should be the best for the desired therapeutic effect.10. The nurse should observe and recognize symptoms indicating success or failure of attainment of the desired effect. 11. The nurse must have a thorough knowledge

of how to administer drugs.

12. The nurse must be aware of the fact that constant small quantities may eventually set up symptoms of poisoning.

lit-Similar principles of administration in the thera-peutic use of drugs are either directly stated or implied in the additional works investigated in this study. The principle that the nurse should have a thorough knowledge

ot

how to administer drugs is implied in all of the refer-ences that were consulted. Nine of the eleven sources suggest that consideration be given to the factors which tend to modify dosage, such as the condition of the pa-tient, the time, and the weather. The majority of the authorities in drug therapy also agree that knowledge of the maximum and minimum dosage is necessary if the nurse is to take ordinary precautions in the administrationor

drugs. The extent to which the several authorities agree on these points and on others is illustrated in Table 1.The several principles of therapeutic procedure in drug therapy are listed in Table 1 according to the

17

rank of the frequency of their appearance in the litera-ture of the fiel d. They are expressed in an abbreviated form in order to facilitate charting. The references proceed from left to right in chronological order. The figures that appear after each principle, in the refer-ence columns, indicate the number of the page on which the principle

occurs .

To provide a complete picture of the emergence of these principles in the literature that was investigated, both the number of references in which each principle occurs and the numberor

principles occurring 1n each text are expressed in total. This arrangement is also followed in Tables 2,3,

~7 and5

ich deal withprinciples of therapeutic procedure intle fields of oc-cupational, physical, psycho, and speech therapy, respec-tively.

It may be noticed in Table 1 that some authori-ties fail even to mention the physician. This omission probably can b explained by the fact that these particu-lar texts deal primarily with specific techniques in the application of drugs. They are accepted as references for this study inasmuch as th.ey definitely imply the need of certain fundamen~al principles in the use of these

TABtE 1

FREQUENCY OF PRINCIPLES OF THERAPEUTIC PROCEDURE IN THE LITERATURE ON DRUG THERAPY

cipl--1: K o b">V to ad.minister

drug<-:-;1.90

sider factors that modify dos "El.I

~ -~o·1

i~1

•r

r~

0 • t<.~s

~ ll.6* 117 ll7 ll7 ~ 19 25 lS 23. 25 l 23 23 19 19c dit for lar e part of

·---t-"

- ' 1 -... ...._ ... ...__,_,,, _ _ _ . . . _ _

---"""'"-~_L_1_1__,,,_

__ _

14. Con ider o .. ,h r tYr · of therapy wh ch JT-iL'Y

bo Ile~ SP.t'.rl

Total

Nlll!I~ ~inciples 0e"11.r~

in Z~~ Te~]

*Number of pag on which principle occuree 16

-en ~ ~ ~

.,.

..

Goostray, !f!teria Medic.a, 4th ed. A!'! Introduction to J 1959.en en

""

~..

(II~ Faddis & Hayman, Textbook

o,t

""'1 CJ) t» -..J tn ...:. fP.a.rlnAcoloa, 1940.

MeGuigan & Krug, AA In~oduc·

...,,

a> Q)~ ~ Q) ~

g

Q.l <» ~g

Ql tion to Ma.teria Medic! AP.aN 0 0 0 0 0 0

Pharma~ologz:, 1945.

:t'

~~

•

"""1

...

...,

~ ~ Cutting, Action! !S9 Uses of<n l\"J Q) Cl) ~. 1946.

~ Dooley & Rappaport,

P~-~

t

01 <:,;t

t

qo~oJIX.ffe Therl!Pautiqf_ipOl en

"

a>C>t Nur1ing. 1948.

"11 ~ ~ Cit (>1 (>t cq Muller & Dana, J.n.t..t.odj!gtion

....,:: t\) m 0) !\) 0) N) c:» l\) l\) N to Medi .. c1,l Scien.,c~, 1948. 0) m m ti 0 : Ii

i

... II

Q,(0 a> en CD en Bennet., ~tei;.~! .Met\,ic~ foJ:_

en t{ursy, 1949.

().) ())

~ a> ~ ~ ~ ~ Wright & Montag, Pha.rgcologr;

co ... f-S ... §:_TberaEentics, 1949.

~ Total Number of Ref erenoes in

18

Further study or this table reveals only one advo-cate of the principle, "Nature should be given credit for a large part of the improvement."1 It is most interesting to observe that this same basic thought is expressed 1n an · excerpt on Hippocrates, "He [

Hippoerate~

also believed that nature had the power to cure disease and that the physician ,should aid the recuperative powers of the pa-tient with drugs, diet, sunlight, or by other means."2 A principle that has endured for 2500 years must be basic. Therefore, it is accepted in addition to the above list of principles.According to Windsor C. Cutting, "other types of therapy may often be as necessary.n3 Although the prin-ciple implied in the above statement does not appear in the other texts on drug therapy, it is significant, since it occurs 1n a recent publication and implies the need of cooperation with the several therapy groups that today are medically recognized.

Occupational Therapy

Occupational therapy has been defined as ttany

ac-tivity, mental or physical, medically prescribed and

1Hobart A. Hare,

A

Textbook of PracticalTherapeu-llsa,

21st ed.; p.17.

Philadelphia: Lea and Feb1ger,1930.

2Krueger, op. cit., P•

19.

3w1ndsor

c.

Cutting, Actions and Uses of Drugs, p. 2. California: Stanford University Press,1946.

19

professionally guided to aid a patient in recovery from l

disease or injury." In occupational therapy, activi-ties are directed towardf!Pecific problems resulting from disease or injury. Because of the great number and vari-ety of human problems of both a physiologic and psycho-logic nature , these activities are manifold.

To provide basic mate 1al for a questionnaire used 1n an Activi y Survey conducted by the Ai:~erics.n Oecu·

pational Therapy Association , a committee of practicing therapists assisted the Education Office in compiling a list of activities believed to be currently employed 1n

occupational therapy departments.. The survey contained

70·

activities of which31

had subtypes and techniques · to-talling 205' in all. Provision was also made on the qes-.tionnaire for recording and reporting on any otheractiv-ity used by occupational therapists but not included in the basic 11st.2

This great number of therapeutic procedures makes the field of occupational therapy almost oundless, limi-tations being indicated only b the required direction

for the solution of the spec:tfic problem of the

indivi-dual patient o The specific problem may be related to one 1Willard,

H.So

and Spackman,c.s.

Principles of Occunational Therapx, p. 10. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippin-cott Co.,·1947.

2Act1v1tY Su:rvey Report of the Education Office of the American Occupational Therapy Association, p. 1.

20 or more of the several disability areas, i.e., mental diseases, physical disabilities, cardiac conditions,

tuberculosis, pediatrics, gereatrics, and general medical and surgical conditions.

In spite of the vastness of the field

or

occupa-tional therapy, it has undergone a progressive development during the past thirty years and is today recognized as a definite therapy group. This is evidenced by the greatnumber of institutions in which it forms an integral part

or

the total treatment program. There are some 700 hospi-tals in the United States that can boast. an occupational therapy department.1 The present status of this wide field of endeavor suggests the existence of certain basic principles that have served as guides to the therapists in their selection and administration of occupational treat-ment. It might be assumed, therefore, that such definit basic considerations have influenced the methods of appli-cation in occupational therapy.Exploration of the literature concerning occupa-tional therapy reveals that, as early as the year 1920, a list

or

principles of therapeutic procedure was recom-mended to the therapists by the Committee on Principleslibid., p. 1. This number includes approximately one half of the country's hospitalsi as estimated from

of the Occupational Therapy Association. 1 These prin-ciples may be stated as follows:

1. System and precision are as important in occupational therapy as in other forms of treatment.

2. The treatment should be directed toward the individual need of the patient.

3.

The activity selected as treatment should be within the patient's interests and capabili-ties.4.

The treatment should be regulated and graded according to the increase of the patient's strength and ability.5.

The activity should be directed primarily toward its effect on the patient.6. The treatment should be based on normal standards of achievement in the activity.

21

This is, perhaps, the earliest record

or

a definitely for-mulated list of principles of therapeutic procedure in oc-cupational therapy. Examination of the content of oneor

the most recent texts dealing with principles and practices in this field shows a reiteration of the suggestions in the·. .. 2

original recommendation with, however, several additions. Whereas, formerly, stress was placed on the selec-tion and use of an activity, later thought on the subject appears to be more therapist-centered. For example, at-tention is drawn to the attitude of the therapist as having

luprinciples of Occupational Therapyn Occupationa).. Therapy and RehabJ;titat.ipn. XIX (February

1940),

19, 20.2nunton and Licht~ Occup~tional Thera.RYJ ?f~pciples

and Pra .. ctice1 pp.

16, 17.

Springfield, Illinois: Charles22 a direct influence on the therapeutic results of the

treatment. "The therapist must accord to the work projeet the respect and dignity of the healing process which will convince the patient that the work is being guided pur-posefully. n1 It is also the duty of the therapist to

mo-tivate the patient by "stimulation o·f the desire to attain an achievable objeetive."2 Emphasis also seems to be

placed upon the professional training of the therapist to insure therapeutic use of the activity selected. "The finest equipment ••• cannot be properly utilized without adequately trained and guided personnel.11

3

Final, but notleast in importance is the principle that the occupational therapist work unde the supervision of and in cooperation with the physician.4

Medical supervision for the occupational therapist is advocated in ten of the thirteen works consulted for this paper. It is probably significant that the three sources in which it is omitted date back to the beginnings of occupational therapy when the average physician was not yet educated to the therapeutic possibilities of directed occupation and was, therefore, unwilling to supervise such a project.

Several more principles are advocated in what seems the most comprehensive recent text o~ occupational

llbid. t P• 10.

3

.:tb!d. '

p. 17.2Ib1d.' p.

4.

therapy, ,frinciples Qf .Pc~upj! tional ~.er§JJ'!l, by Willard

and. Spackman. These principles are:

1 . The study of the case history of the pati~nt

is necessary for an intelligent approach.I 2. Progress reports are essential to the

evalu-at:f.on and imp1"ovement c1f the treatment.2

23

3.

There should be a defil1ite therapeutic objec-tive for the treatment.34.

The treatment should be . ~opped before thefatigue point is reacheds.

5.

The treatment should be cotrelated with other treatmentsor

the pat1ente~6. The activity shoul.d be presented in sueh a

way that j.t brings pleasure to the1 parti-cipant.6

It would seem that the first three of the.se suggestions indicate a tendency to work toward a definite rationale in treatment . Study of the case history of the patier1t and evaluation of the treatment by means of progress notes

might lead to a more correct interpretation of symptoms and to a more specific knowledge of the physiologic action of the remedy employed. If these suggestions were fol-lowed conscientiously, "rationaln treatment in occupa-tional therapy would soon replace the few remaining traces of ··the 0empirical" type of treatment which prevailed prior

to the nineteenth century.

lw111ard and Spackman, 5a.12• .. Q.~., p. 124. 2Ib1d . , P• 9l e

!+Ibid •. ' p.

89.

3Ibig..!., p $. 88.

Because of the present-day advantages with regard to knowledge of causes

or

disease, it is essentiai for the modern therapist to administer treatment in the lightor

definite therapeutic objectives. These objectives would be frustrated, however, were the therapist to carry on an activity to the point of fatigue, since physical fatigue can produce a psychic reaction that may hinder the pro-gress of the patient.The suggestion to correlate the treatment with the other treatments of the patient comes almost as a warning to those who are in line with the present trend toward

over-specialization, in which intensive study of one aspect of knowledge can easily lead to the exclusion of all others. Seldom, if ever, does a specific disease depend entirely upon an isolated therapeutic medium for its cure. Treat-ment by means of directed occupation has its place among

the other therapies as a part of the total treatment pro-gram and not as the total treatment. Therefore, the thera-pist should strive to correlate the occupational treatment with the other treatments of the patient.

The activity should bring pleasure to the partici-pant. In order that this may be realized, the therapist might promote . certain external and internal conditions,

sueh as the absence of fatigue by the provision of inter-spersed rest periods, opportunity for comfortable group feeling, and· the realization of pride in the product, and

a conviction that t he wor is useful and appreeiat ed. l

Haas comes to a similar conclusion when he says that the ae-tivi ty must be so presented as to give satisfaction to the patient.2 Fulfillment of the above conditions implies the use of group activities . Slagle and Robeson, however, make t his reco endation specific in the statement that employment in groups is advisable.3

To a lar e exte t the authorities agree ~~th regar d

to the pr inciples of occupational therapy. This can be seen in Table 2. Patterned after Table 1, Table 2 pre-sents the principles in the order of the rank of their frequency, and the r eferences in the 01,.der

or

their publi-cation. Again, both the horizontal and vertical column are expressed in total.A study of Table 2 shows that ther is a majority

of' agreement among the several authorities on nine

or

the sevent een suggested principles. Further study of this table r eveals that the principles occurring in the minori-t7 appear in recent literature on the subject. This is es-pecial ly t rue 1th regard to the training .of the therapist and the determination of a deflnite therapeutic objecti vel Willard and Spackman, op.

cit.,

p.89.

2t.J.Haas, Occupational Therapy, p. 132$ Milwaukee: Bruce Publi shing

co·. ,

192;.3s1agle and Robeson, Syllabus for Training of Nurses in Occupational TherapY,2nd ed.; New York : St at e Hospital Press, 194'.l.

Bo. ~ 1. 2.

s.

'·

s.

6. 7.s.

9. 10~ ~~ ll. 12. 1~& 14. lS. 16. 17. TABLE 2PBEQUE!lCI OF PRINCIPLES OF THERAPEUTIC PROCEDURE Ilf THE LITERATUllE ON OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY

•

-lQ · • t'O 'N ~ ~ a> ,.... ~..., .-f ""-

.

~

\.t,., g

oe .._,,.8

QM #l· •.,.. H E-f !"4 r,.. • CQ .. Principl si

0 +> •i"'

:/:J.: .

~s

~ ,.... Pit ard Q..=

6

p.. . . . <4 ..., ~8

=

i

- 0 +>..

i

~"S.

(1l~

~~ floe ~ ~ Work under medical sunervision 115*Tres.t individ1JAl nead or natient 153 528

Observe tmJ.datioa

or

work in activities 119 328 Sti11ulate in patient d ire to attainachievable obiactive 528

Direct activity toward effect on Patient Keep within patient's interests and

capabilities 136 328

Aim at normal standards of achievement 143 528 Emt>lov sYstem and t>reoieion 142

Correlate treatment with other treatments

. ot· ·na. tient

..

1 5 328Accord to work project respect and dignity

of healintl process

KeaD »ro~ss notes to evaluate treatment 119 Have adAOWlte trainirur

Ston hAfore f'Rt.iDu~ uoint is ren.~bNl

Study case history ot Patien+, 328

Have definite thera;eeutic o,Pjecti...§

Present activity so as to give satisfaction

to Patient 152

Emoloy in Q'roUJ>s when advisable

Total Nur.aber ot Principles Occurring in Ea.oh Text 9 7

*Humber of page on which prineiple oooura.

26

k-;;

"'

8~ of"f -. +' ...~i

o< (.)..., OH I)!;!....

• -~H~§~

= 0 "= IQ~]!

+> IS ll8 118 117 .-

116 11? 118 -ll8 70) ...

...

~ 01 ....;a .. 0) ~·"'

?\? ~"'

en en t:; ~ ~ ~to

lO

lO

t;

en C1t~

Ot en~

s

ft

~s

lt

§; §; . ~I

ti

t1

~ ~ "'1 ~ ~ ~ t; 0) CH ~ '"'1 ~ ~ cot:·

::

~ ~St

·-~

~E

~t

t

t

m

~ ~ (J}f8

en CD Ol ti,) (J) ~b

... ~MIN

-

~~~

N> N CJQ CM ~°'

CP.t:

~ ~ to ·~~

N tn 013

t;;tr:

E

E E

E

M~

... ... Q1°'

-..; ~ ~ ~ti:

-,_.

(f):s

~I

...., N N ~ (Ii ... ...ti:

~ ~ U> CD fDe;

Craven, "Some Suggested Prinoi-ples tor O.T.," O.T.R., XVIII

(Feb., 1940)

Neuatadt, '1The Relationship ot

o.r.

to Current Ed. Trends,"O.T.R., XVIII(Aug.,1940)

"Principles of O. T. , n ~T. R. ,

XVIII (Feb•, 1940)

Slagle & Robeson, ,8.t;llaby, 2nd ed.J 1941.

. ...:~.

Davis, ~haQ.1ll~tion2' .Its

Prill-_gi;ales & _P~actices, 1946.

-Franciscus, 110.T"t Where? How?

\fh1'ftt O.T .. R~,XXIV(Aug., 1946)

-·Haas, Praotieal O.T_. ,2nd cd.;1946

-

-"""--~Willard & Spaokman, Princi2l11.

!d

o.

tt:.t.,

194 7.-ttQomplimentary Roles of O.T. and

Ps7cholog.Measurement in Rehab." A•J.O.T.,III(Sept.·Oct.,1949) Dunton & Licht, .2~··T· ,P.riuci:elu

.N!d Pn.ctic!!, 1950.

~- All!Wl ...

Total Number of References in

which Principle Occurs.

~

::

pa

•

l

E

g;

~I

28

tor the treatment . These two thoughts are interrelated: the therapist will have to be adequately trained if he is to make the proper use of the

many

discoveriesor

mod-ern science and medicine; and their proper use, 1n turn, demands direotionct the treatment toward a definite thera-peutic objective .Physical The.rapy

Physical therapy has been used primarily with the orthopedically handicapped. Recently, however, it has been included in the treatment of medical and surgical conditions, such as tuberculosis and the chest surgery

pa-l

tient. Each of the currently recognized procedures in physical therapy has had to go through a period of expert observation in order to be accepted by the medical

pro-ression.

Its practices have had to meet definitestand-ards of therapeutic procedure. Many of the underlying thoughts or principles influencing these procedures are expressed in the literature of the field. Several sug-gestions re offered by Richard Kovacs, Clinical Profes-sor and Director of Physical Therapy at the New York Poly-clinic Medical School and Hospital, and first full-time professor of physical therapy at any medical school in the United States. They may be summarized in six principles. 2

lMildred Elson "Physical Therapy." American Journal of 0£cupa.tionai Therapx;, !(October

1947),

2?J.2Richard Kovacs, Phx~ic1l 1'herapY for Nurses,

l. The treatment should be directed toward existing conditions.

2. The treatment should be applied according to the prescription of the physicianft

29

3.

The procedure should be formulated definitely, that is, the teps involved and the underlying reasons ~or those steps.~. The method of treatment that is selected

should be adapted to · the individual equation of' the patient.

$.

Careful technique and measured dosage should be employed in treatment.6. For successful treatment the therapist should be well trained.

A.C. Ivy also states that the therapist &.~ould be

well trained if the treatment is to be therapeutic, but suggests three additional factors as essential for success in therapy: first, that ·the treatment be directed toward the removal

ct

cause; second, that the treatment be di1~ectedtoward helping the pa tien.t to cure himself; and third, that when one gives a tteatment, the heart should be used as

1 much as the head and hands~

These are worthy precautions against the material-istic tendencies of the present day. Respect for the dig-nity of the patient as a person can be easily overlooked in a treatment which appears to be directed entirely toward improved bodily mechanics

or

the effect of physiologic changes.lA.C_. Ivy, ''The Essentials for Success in Therapy,", The PhY§iotherapY Review,

XX

(September-October1940),

2,9,

30 S.ince the patient is by nature social, it can be assumed that the good of a physical therapy treatment de-pends upon the technician's having a genuine interest in

the patient.1 This interest can be augmented through inter-patient relationships. Group contact often stimulates the progress

or

the patient. Therefore, whenever possible, group work should be used in treatment.2According to Mildred Elsont Executive Secretary of the American Physiotherapy Association, the techniques of treatment in physiotherapy should be applied "upon medical prescription so that maximum functional recovery of the patient will be obtained in the shortest period of time.11

3

Unless the physical therapist, however, has amedical background and understanding and a knowledge

or

specific techniques in the application of physical medi-cine he will not be able to fulfill this formula. There is need, therefore, for the therapist to be well trained in the field of physical therapy. Aecording to Elson, "The importance of a well-trained personnel has not been mentioned, since it is an accepted principle.nl+1Frank Krusen, fhysica} Medicine, P•

771.

Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Co . ,1941.

2Barbara White "Physical Therapy in a Rehabilita-t;ion Center, 11 l'.Pe Physiotherapy Reviey,

x.xx·

(February 195'0),o.

3Elson,

op. cit., p.273.

it-Ibid.' p. 276.31

Several additional principles that pre-suppose a well-trained therapist are recommended by some

authori-ties. Krusen believes that the therapist hould know the effects of the medium used.1 In the opinion of White, the therapist should keep progress notes and evaluate the

treatment.2 Abbot, Moor, and Nelson 1arn the therap st to conform the treatment to physiologic law. They also advise the treatment of symptoms which, in their everity, become causes.3 In the light of these several principles, the training of the therapist m ght be said to1:e a fore-gone conclusion. It is almost unanimously implied in the literature of the field, as can be .seen in Table

3,

con-structed after the manner of Tables 1 and2.

It is evident in Table

3

that the trainingor

the physical therapist is considered of prime importance bythe several authorities in the field. They also seem to place emphasis on the idea that the treatment should be applied according to prescriptiono The reciprocal rela-tion of these two principles to each o·ther might explain their dominance among the total principles discovered.

lFrank Krusen, L gh Therapy, 2nd ed.,,i ( evised and enlarged); p. 204-. New York: Paul B. Roeber me.,

1937·

2Wh.ite, op, cit., P•

50.

3Abbot, Moor and Nelson, Physical Therapy in Nursing Care, p. 50. Washington D

.c.:

Review and Harold..

I

Mo. ._1. 2.s.

"' 4 •..

5. 60..

7.a.

-

9. 10...

1.1.J2.

J3.

.,14. .:15. _16. 17. TABIE 3FREQUENCY OF PRINCIPLES OF THERAPEUTIC PROCEDURE IN THE LITERATURE ON PHYSICAL THERAPY

~

..

~

Principles;

;t-!

tQ ... m d ri (!)H

-Have adeQua.te training 204*

Apply treatment according to prescription Direct treatment toward existing conditions Formulate treatment definitely

Work in coordina. ti on ri th other dePart1nents

Adapt method to need of Patient

Use careful techniaue and measured dosa2e 204

Direct treatment toward removal of cause Direct treatment toward maximum functional recover:v in shortest Period of tLiie

Direct treatment toward helping patient cure

himself'

-·

Use heart as much a.a head and hands Have £enuine interest in n~tient Use group work whenever Eossible

Know eff eats of mediwn used 204

Keep progress notes to evaluate treatment Conform treatment to EBzSiologic law

Direct treatment toward symptoms th.i:it become

~A.uses

Total Nwnber of Principles Occurring in Each Text 3 ...

*Number of page on which principle occurs. 32 • «> tO o8~ ~ · ~ s., (1) ~

::3

tQ 0.!3

~ (,)~

~ ,_. r:a!l (!)-ES

Ul()...,

~-§ ~3 24 24 24 24 24 5(,,,:a o;; t ~ 0) ~ (>1 ~ ~ CJ) (111 t--t en ... -.;) ""1 ... C1& ..., C>1 C11 (11 0 0

....

....

....

""'

... ~ ~ l\:) ~ N> 0) (J1 0 (.0 Ul (A ... c.n N -..:. l\? ..., ~ ~tit

C1. 0....

... Z\) l\) to Z\l CM.... ....

:;;: IP- en -"'I 0 O;>....

....,....

...., Q) Q) CJ) co N en co ..:a ~ ...., ""3....

....

CM I-' en N !\') ~ ~°'

t

"'

CA ())...,

Ewalt, Parsons, Warren &

Os1>orne, Fever Ther aI?Z Tega-nigue, 1939.

Kovaos , Phzsieal TheraJ?.l for Hurseaj 1940.

Ivy, "Essentials for success

in Therapy,'' Pvsiotherapz Revi,Jt,XX(Sept.•Oot., 1940)

-·-Krusen, P!:!.!sio~ Maj.ioine,

1941.

Abbott, Moor & Nelson, PhYsical Thera:ez in Nursing

~' 1945.

Elson, "Physical Therap7,"

A.J . O~T., I(Oct., 1947)

White, "Physical Therapy in a Rehabilitation Center,•

~siothe.r~f Review, IXX

b., 1950

Total

N'ulilber of References in which Pri nciple Occurs.i1

~ ~111

i

~ II

Although the remaining fif''teen p1 .. inciples are in a decided

minority, they are similar to many of the principles pre-sented in the earlier chapters of this thesis. Therefore, they are accepted for later analysis and comparison with those of the other therapy groups.

Psychotherapy

Psychotherapy is the oldest of the therapeutic

measures~ According to Harriet Bailey, it is 0based on

the principle that a disorder the mind has produced, the mind can cure. It includes all the methods of influencing both the physical and mental condition by the use of

psy-chological means, such as simple explanations, encourage-ment, reassurance, suggestion, persuasion and re-education."1

Some of the past and current methods of

psychother-apy are enumerated by Carl Rogers in his study on

counsel-ing and psychotherapy. 2 He refers to the technique of or-dering and forbidding as one of the oldest. In this pro-cedure , personal forces were brought to bear on the indivi-dual. The procedure has long been discarded and, according to Rogers, 11is now only a museum piece in psychotherapy."3

Another · approach as exhortation. This procedure consisted 1Harr1et Bailey, Nu sing Mental Diseases,p.

167.

New York: The MacMillan Co.,

1939.

2

carl

R. Rogers, Counseling and Psychotherapx,pp. 20-27. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co.,

1942.

3

I}? id. , p • 20.in working up the individual to a point where he would sign a pledge or make a promise. This technique has been almost completely dropped because it was invariably fol-lowed by a relapse. The third approach was the use of

suggestion, both by the therapist and by way of autosug-gestion. In this method~ excessive reassurance and

en-couragement were given to the s.tbject in an attempt to strengthen his motivation in a definite direct_on. Rre-quently, however , he was actually impeded an.d did not feel free to bring his less acceptable impulses to the clinical situation. Faith in this procedure has been on a steady decline. Rogers cites the psychotherapeutic approach of catharsis, or release, as of ancient o~igin. It has not

only not been discarded, but it has gone through a period of development and is widely used today 1n various forms, such as psychoanalysis, finger paints, psychodrama, puppet shows, and play therapy. Advice and persuasion also form a type of psychotherapy*

In

this approach the therapist intervenes in the client• s life to make sire that he moves 1n the direction of the goal wb1.ch the therapist hasSG-lected. Today this technique is frequently seen 1r1 actual practice. The cc!lnselor , however, is often unaware of the amount of advice he gives. Rogers menti.ons one more psycho-therapeutic approach. This last approach assumes that ·all that is needed to help the individual is to explain to hj.m the causes of his behavior. It has come to be recognized,

however, that the client's behavior cannot be changed very effectively simply by giving him an intellectual picture

of its patterning. The new approach has a genuinely dif-ferent goal than the older ones mentioned above. Accord-ing to the explanation of Rogers:

It aims directly toward the greater inde-pendence and integration of the individual rather than hoping that such results will accrue if the counselor assists in solving the problem. The in-dividual and not the problem is the focus. The aim is not to solve one particular problem, but to assist the individual to grow, so that he can cope with the present problem and with later prob-lems in a better-integrated fashion o•- For the first time this approach lays stress upon the thera-peutic relationship itself as a growth experience a•• this type of therapy is not a preparation for change, it

i!

change.lIn

his latest publication, Rogers supplements and expands this view. The later work does not replace the earlier volume.nrn

some respects the older work still provides certain essential steps of introduction to the basic concepts of modern counseling, which are not repeat-ed in the same detail in this book. u2 In the recentv·ol-ume, Rogers gives a. "current cross section of a developing field of therapy, with its practices and theory, indicating the changes and trends which are evident, making compari-sons with earlier formulations and, to a limited extent, with viewpoints held by other therapeutic orientations•"3

1 Ibid., pp.

29,

30.2carl R. Rogers1 .Client-Centered

Thera~z,

p. viii. Boston: Houghton Miffll.n Co.,1951.

37 Although Rogers provides an overview

or

the factorsthat

have influenced the course of thinking in this type of therapy during the past decade, he actually presents

only

one viewpoint , or school of thought on the subject. He recognizes the influence of several bas:f.c principles in most of the cases of ucces ful client-centered treatment?

which are: the counselor should see each person as having worth and dignity in his own r1ght;1 the counselor should act upon the recognition of the individual's capacity to deal constructively with all those aspects of h:i.s life

2

which

can

potentially come into conscius

awarenes~; thecounselor should think, feel, and explore ~nth the elient;3 the col.Ulselor should be someone with a mth and interest for the client;

4

the client should be made to experience responsibility .:for his problem;5·

counselirlg should provide. 6·

the client experience of re-crganizin~ self; counsel

r-eliant relationship should

be

impersonal and secure;7

and, the counselor should p~ovide the conditions in which theclient is able to make, experience, and to ac~ept th .

diag-nosis of the psychogenic aspects of his maladjustment.8 Ob ervance of the above principles requires def i-ni te qual1f1cat1011s in 'the therapist. In regard to the training of the therapist, various current opinions show

1 Ibid.' P• 20. 2

ll21d!'

PP• 24,25.

3Jb1do 9 P•3l.~

mq.,

69.

;

72.

6:tb1cL, , · p. 77.P• ~., P@

a steady trend away from technique, "A trend which focuses upon attitudinal orientation of the counselor.n1 Another trend is to give the student the opportunity of personal therapy, in order to sensitize him to the kind of attitudes and feelings the client is experiencing that he may become empathic at a deeper and more significant level. The prac-tice of therapy as a part of the training experience from the earliest practicable moment is also advoca:ted. 2

Having considered these

current

trends and opinions, Rogers suggests the following as a desirable preparation for the counselor: broad experimental knowledge of the hu-man being in his cultural setting; background of empathic experience with other individuals through literature, drama, .dynamic psychology courses, or through living; op-portunity to consider and formulate his own basic philos-ophy; personal therapy; deep knowledge of the dynamics of personality; and knowledge of research design, scientific methodology, and of psychological theory.3 It is evident, therefore, that the psychotherapist must be well trained.The personal qualities of the counselor can also have a direct bearing on the success of the counseling,

l+

according totl.e recent study made by Curran. Success libdJi., p~ 432. 2Ibid., P•

433.

3~.,

pp.437, 438.

4 Charles A. Curran, Qouns~ing ~ in Catholic Li,ie

39

of the counseling can be effected by the counselor'

back-ground, personality, and his own psychological needs and weaknesses.1 Similar to Rogers, CUrran believes that the knowledge of the counselor should extend to the general characteristics that go into personal problems. This would include a background 1Il the fundamentals of' such

subjects as psychology, sociology, social case work, phi-losophy, and theology. Curran differs from Rogers, how-ever, inasmuch as he does not specifically recommend per-sonal therapy f'or the student counselore Rather, he cau-tions the counselor to be aware of his own personality blind spots in order to be consistent in his counseling role; a tendency to dominate, on his part, may lead to an

2

unwise psychological and spiritual attachment. The train-ing or the counselor, therefore, should be directed toward helping him to understand and promote proper client-counse-lor relationship . Curran clarifies the natur of this re-lationship. It s one in which the counselor helps the client to view his personal confusions and conflicts

ob-jectively. This in turn enables the client to reorganize his emotional reactions so that he not only chooses the proper solution to his problems, but has sufficient confi-dence to act on his choice.3 That he may improve kill in

1 Ibid.' p.

332.

3Ib1Ji.'

p.1.

promoting and maintaining this relationship, the couns -lor is advised to make careful study of interview excerpt • Although the interview cannot be changed once it has taken place, the counselor can, by this study, grow alert to his mistakes and improve his subsequent counseling.1 Conscious of his own 11mi.tations, however, he should be 11ling to accept help from psychologists, psychiatrists, physicians, sociologists, social workers, and priests. 2

Finally, Curran recommends that the counselor es-tablish a definite relationship with respect to the time, length, and date of the intervie •

3

Such a systematic ap-proach mi-ght help the client to recognize that counseling!t-is not a permanent relationship.

Both Rogers

and

Curran admit that some problems require group therapy, in which case the above principles are also applicable~ JHdging from the opinions of severalauthorities in the field of psychotherapy, the influence of these basic principles is evident in mental hygiene inter-viewing, non-directive counseling, practical psychiatry, and nurse-patient rela ionships in psychiatry. The extent of the similarity of' opinion among the several authorities can be seen in Taole

4,

which is arranged according to the patternor

the tables in the previous chapters.l..Il>..!9..,

p.235.

2 Ibid., P•333·

-...

TABIE 4

FREQUENCY OF PRINCIPLES OF THERAPEUTIC PROCEDURE IN THE LITERATURE ON PSYCHOTHERAFY

Princ:f p1es

Have a!,lf-knowledge ~ View client as ha.vin

5. Esta.blish impersonal and secure ti one hi

I :

66 Make uue of subtle su estion

~---~---+----+---1 o Be s stematio and orderl

a.I cooperate \fith physician, psychiatrist, soeiolo3ist

... · ..._ ... 12 ... r1 __ M_!=Lt __

-=··

==,--...

-:~----~h

... ·e-_n_e_v-... e-r._-_n-e ... _,,c __ e-... s-s ...~---_-:__--_-_=-.---_

...

r-=_-_·:1~~:-=.:-.-=:

~kill

l4o Provide cli~n~ a erience of reor anizi

15. ht..ake client e2m.eri~nce re.~~j_l;_i ... t~ ... · ... f ... o .... r_...,,._.._..._.. ... _....,_-'"'4 __

lSofView counsel.in as terminable ralationshi

17 o E lore aim le er-s.onali ty me_c __ har_d_sm_s _____ ,

18. Have lon .,_term contact with p~tia.-.!'L_ _________ _,,. __ +--_19_· _7_

19. Do not limit tre tment to ~i.ngle.me,...,· t.,....' h...,o .... d...__. ___ ,

20c Provide client opportun..tty to make, experience, and

__ jacceEt own dia.gl'.losis

Total ~"umber of Principles Occurring i n Each Text *Nl.llilber of page on which principle occurs.

41