The Twitter Posts of the Brexit Campaigns:

A Comparative Assessment

Malmö University

Media and Communications MA Thesis

Authors: Arnold Eric Craven and Christopher Whitwood

Word Count: 23,170

Table of Contents

Abstract 3 1 Introduction 4 2. Research Problem 5 2.1 Research Questions 6 3. Literature Review 83.1 What relationship exists between political campaigns and the media, and how can that impact on

society? 9

3.2 What impact can the media, including social media, have on political discourse? 10 3.3 What impact can social media have on voter behaviour? 11 3.4 What motivates voters to participate in elections and referendums? 13 3.5 How do propaganda and ‘fake news’ play a role in political communications? 17

3.6 Literature Review Summary 20

4. Methodology 22

4.1 Research Strategy 22

4.3 Research Paradigm 25

4.3 Ethics 26

5. Results 27

Theme 1: Engagement - How did the engagement of the two campaigns compare? 27 1. How did the online engagement compare between campaigns? 27 2. How does the frequency of tweets compare between the two campaigns? 30

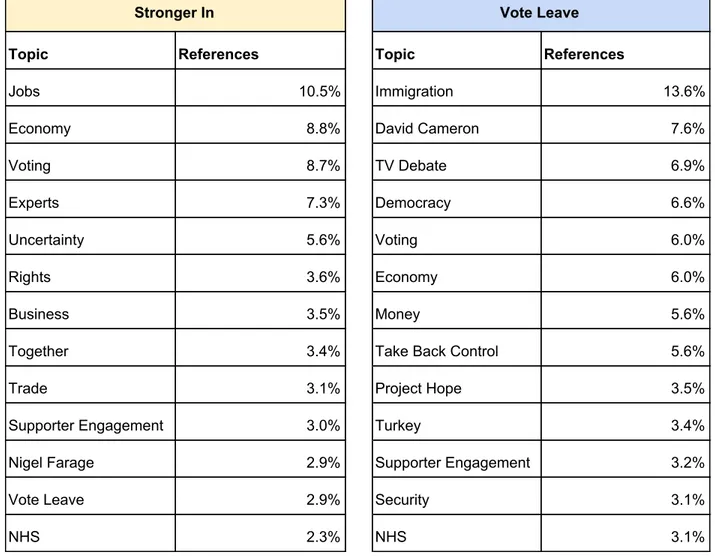

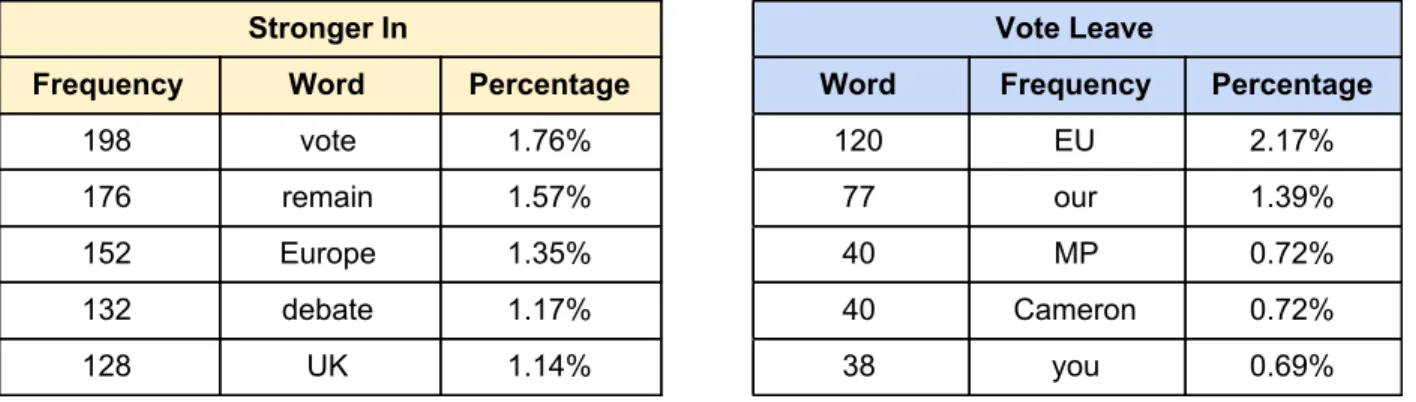

3. What topics received greatest engagement? 33

4. How did engagement levels change over the course of the campaign? 36 Theme 2: Messaging - How did the messaging of the two campaigns compare? 39 5. What were the key themes of each campaign in the run up to the referendum? 39 6. How does keyword repetition between the two campaigns compare? 43 7. How regularly did the two campaigns share links to external sources and how broad was

the range of sources? 46

8. How did the messaging of the official campaigns change over the course of the referendum

campaign? 51

9. To what extent did the use of hashtags relate to the content of tweets? 55

6. Analysis 57

6.1 Opportunities for further research 61

7. Conclusion 62

Abstract

This thesis discusses what some commentators and academics regard as one of the most contentious political issues of the 21st century: The United Kingdom’s vote to leave the European Union, now known as Brexit.

As Goodwin and Ford explain, the United Kingdom’s decision to vote to leave the European Union in the 2016 referendum ‘sent shockwaves around the world, rocking financial markets and rekindling global debates about the power of populism and nationalism, as well as the long-term viability of the EU. Aside from calling attention to challenges to mainstream liberal democracy and international integration, the vote for Brexit also highlights the deepening political divides that cut across traditional party lines in Britain and now threaten to further destabilize an already crumbling two-party system’ (2017: 17).

It is this topic, something which sent shockwaves around the world, impacted on the financial markets and rekindled ideological debates many thought of as closed, which is studied here. This study takes the form of a comparative assessment of the two official Brexit campaigns’ Twitter accounts, making use of the interpretivist paradigm.

Whilst this thesis does conclude that the successful leave campaign - Vote Leave - did run an effective campaign, this is perhaps not the most striking conclusion of the thesis. Instead, it is the poor quality of the Stronger In campaign (the campaign that was in many ways the favourite to win the referendum) and the failure to take advantage of the opportunities offered by social media.

This failure by Stronger In to engage on Twitter in a way comparable to Vote Leave - through nearly every metric illustrated in section 5 of this thesis - is a stark discovery, and one which perhaps warrants more research, both through sampling further tweets and potentially undertaking a similar, Facebook-based study.

1 Introduction

In 2016, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland held a referendum on the country’s membership of the European Union.

This was not the first such referendum to be held. The UK joined the European Union (then the European Economic Community) in 1973. The following year the Labour Party formed a

minority government and in the Autumn of 1974 held a referendum, in which 67% of voters supported the UK’s continued membership of the community (Butler and Kitzinger, 1996). Subsequent decades saw an increase in Eurosceptic voices both in the UK Parliament and the European Parliament. Following the success of the UK Independence Party (UKIP) in the 2014 European Parliamentary Elections, in which under the leadership of Nigel Farage the party secured more MEPs than any other party (Reuters; 2014), the then Prime Minister, David Cameron, made a manifesto commitment that, if the Conservative Party were to win the 2015 general election, a referendum would be held on the UK’s membership of the EU. The general election saw the Conservative Party win a majority in parliament and the manifesto commitment was passed into law in the form of the European Union Referendum Act 2015 (British and Irish Legal Information Institute, 2015).

The date for the referendum was set for 23 June 2016 and the Electoral Commission - the independent body which regulates elections in the UK - announced the official campaign for each side. On 13 April 2016, Britain Stronger In Europe (Stronger In) was announced as the official group campaigning for the country to remain a member of the European Union and Vote Leave was selected as the official campaign advocating for the UK to leave the bloc (Stewart, 2016).

The referendum resulted in 52% of voters wanting Britain to leave the EU. At the time of writing, the outcome of Britain’s exit from the EU (Brexit) is still unclear. However, by undertaking a social media content analysis of the Twitter messages of these two campaigns, this paper will seek to offer an insight into the reasons behind the referendum result.

2. Research Problem

On 23 June 2016, the United Kingdom voted 52% to 48%, to leave the European Union. This departure has since become known as Brexit - a combination of British and Exit.

Following the referendum, studies have assessed the impact the media had on referendum voting behaviour. Gavin discusses this, where he states, having assessed the media’s impact on the Brexit vote, that there ‘is literature evidencing the actual impact of media coverage on economic perceptions, and on attitudes towards which party best handles the economy...it finds very strong confirmation of the general agenda-setting power of the media, as well as some supporting evidence on the impact of UK media stories about the EU on the salience for the public of the EU as an issue’ (2018: 840). A similar argument is proposed by and Goodwin, Hix and Pickup (2018) and Walter (2019).

These arguments utilise on the notion that the media, especially what is usually considered traditional media (Schudson, 1989), influenced voting behaviour and encouraged more support for the ‘Leave’ side of the debate. Similarly, several studies, including those undertaken by Vicario, Zollo and Caldarelli (2016) and Bossetta, Dutceac and Trenz (2017) contend that political posting on social media, both in terms of content sharing and promoted advertising, potentially impacted on voter behaviour ahead of the referendum.

However, while these studies do seek to assess what impact social media postings had on voting behaviour, little research appears to have been done from a comparative perspective. This comparative assessment studying not just what the two campaigns (Stronger In and Vote Leave) posted and how this may have impacted on voter behaviour, but the variance in

approaches between the two campaigns, and how this may have impacted on the referendum outcome.

This thesis seeks to offer that comparative assessment. First, it will review literature dealing with key relevant issues - including theories of mediatization, an assessment of how social media posting can impact on political discourse and elections, a review of what drives people to vote, followed by a theoretical discussion on the impact of propaganda / fake news. Second, it outlines research questions, a research methodology and paradigm centred around the content analysis and the interpretivist approach - realised, in this case, by the sampling of tweets from crucial moments in the Brexit referendum campaign posted by the two official campaigns. Finally, this thesis goes on to present its findings and offer an assessment of the Twitter postings of the two campaigns.

By adopting the above approach, this thesis seeks to both reaffirm the academic basis for the belief that social media impacted on the Brexit referendum and offer new insight into the different approaches the two campaigns undertook in their Twitter activity.

2.1 Research Questions

Theme 1: Engagement - How did the engagement between the two campaigns compare?

1. How did the online engagement compare between campaigns?

2. How does the frequency of tweets compare between the two campaigns? 3. What topics received greatest engagement?

4. How did engagement levels change over the course of the campaign?

Theme 2: Messaging - How did the messaging of the two campaigns compare?

5. What were the key themes of each campaign in the run up to the referendum? 6. How does keyword repetition between the two campaigns compare?

7. How regularly did the two campaigns share links to external sources and how broad was the range of sources?

8. How did the messaging of the official campaigns change over the course of the referendum campaign?

9. To what extent did the use of hashtags relate to the content of tweets?

To undertake this study, two key themes were identified, namely engagement and messaging. In order to answer the two core questions in a structured manner, nine sub-questions above were selected. The decision to break the two core questions down into a series of sub-questions was driven by the need to develop a quantifiable approach as outlined in the methodology and to generate questions specific enough that they may be answered within the scope of this paper. The selection of these questions was informed by Blaikie, who states ‘research questions are the foundations of all research; they make a research problem researchable’ (2007: 6). When considering the appropriate questions for this study, Blaikie’s notion that three forms of research questions exist - what, why, and how, was considered (2007). This study makes use of two of those forms - what and how. As explained by Blaikie, ‘it is not necessary for every

research project to address all three kinds of RQs’ (2007: 7). Instead, this study seeks to address to ‘what’ questions, to build an understanding of the Twitter behaviour of the two campaigns, and to look at ‘how’ - mainly, how that behaviour developed in the run-up to the referendum date. This approach seems best suited to a topic of study where the ‘why’, both in terms of political motivation and the theoretical context for why political tweets impact on society, have already seen significant research focus.

The questions outlined above have a profound impact on the form that this study takes. As Greener explains in his book ‘Designing Social Research: A Guide for the Bewildered’, ‘If you begin questions with ‘What’ then you seem to be putting together a descriptive question – you are trying to find out ‘what’ something is like. This is an open question that can be answered

to find out the characteristics of those included.’ (2013: 10). He goes onto explain that ‘how’ questions are ‘more amenable to qualitative than quantitative research’ (2013: 10).

Considering Greener’s approach, the two identified themes and associated sub-questions appear to best lend themselves to a mixed approach for the study. The two ‘what’ sub-questions are suitable for quantitative analysis, reviewing all tweets and identifying both recurring themes and level of interaction. The seven ‘how’ sub-questions, on the other hand, is more suitable for qualitative study - assessing how tone and content of individual tweets have developed over time. Given this, to support the best research outcomes, this study will undertake a mixture of quantitative and qualitative research - the ‘mixed-methods’ approach outlined by Collins (2010: 48), along with Dunning, Williams, Abonyi and Crooks (2008).

3. Literature Review

To develop a comprehensive comparative assessment of the Twitter posts of the two Brexit campaigns, it is important to first assess literature regarding a number of key theoretical topics. These topics tend to fall into three categories:

● Media theories regarding the interplay between the media, politicians and society - so as to understand the relationship between the actions of the campaigns and potential impacts on voter behaviour

● Political Science theories regarding the referendum itself, particularly around direct democracy and propensity to vote - to understand how theoretically the use of a referendum is justified, what drives people to vote in referendums

● Media theories regarding propaganda and fake news - ensuring that this thesis has a theoretical basis for addressing questions around the content of the two campaigns’ Twitter posts

These three categories are dealt with sequentially below, with sections 3.1 and 3.2 addressing issues around the interplay between media, politicians and society, sections 3.3 and 3.4 addressing what drives people to vote in the way they do, and section 3.5 discussing what impact ‘fake news’ and propaganda can have.

Overall theoretical framework

The literature reviewed in this thesis, between sections 3.1 and 3.5 allows for an overall theoretical framework for this research. The thesis takes the concept of mediatization (section 3.1), establishing the two campaigns as media producers, before in sections 3.2 and 3.3 reviewing literature which theoretically establishes the notion that media producers can

influence both discourse and voter behaviour. Connecting media producers with the impact the media can have is key for the theoretical basis of this research. In section 3.4 theories of what drives people to vote the way they do, both generally and in referendums, are reviewed, to critically discuss how the actions of the two campaigns could meaningfully impact on the choices made on the electorate - and provide a framework for assessing those actions. Finally, to allow for a discussion around the discourse contained within the two campaigns’ tweets, assessing theories of propaganda and ‘fake news’ in section 3.5 creates a suitable theoretical basis.

This approach provides for a theoretical basis which means it can be confidently asserted that mediatization means the two campaigns can be seen as media producers, the media can influence political discourse and voting, the campaigns could affect voter behaviour not just through the prism of mediatization but also through a political science paradigm, and that theories of propaganda and ‘fake news’ mean that the words and messages promoted by the

3.1 What relationship exists between political campaigns and the

media, and how can that impact on society?

To properly study the tweets of the two EU referendum campaigns, it is essential first to address the theoretical context through which the societal impact of media is assessed - mediatization. Ekman and Widholm, in their paper which discusses politicians as media producers, define mediatization as ‘a process that changes the modes of interaction between various social and cultural institutions as a consequence of the media’s major role and influence in society.’ (2015: 82). In Deacon and Stanyer’s work on mediatization, it is suggested that the concept relates to a process ‘in which non-media social actors have to adapt to ‘media’s rules, aims, production logics, and constraints’ (2014: 1033).

Similarly, Strömbäck offers a more explicitly political definition by arguing that mediatization in a political context must ultimately relate to the notion that ‘the media are highly influential in political processes’. (2011: 424).

Utilising these definitions, this study works on the basis that mediatization relates to the changes in the relationships and interactions between both individuals and institutions as a result of the role the media plays in society.

To understand how the two campaigns’ tweets fit within this theoretical framework of

mediatization, it is essential to refer back to Ekman and Widholm’s 2015 work on politicians as media producers. This thesis looks to address relationships between politicians and journalists and what impact that has on political news journalism. Ekman and Widholm’s ultimate

contention appears to be that a ‘mediatized interdependency’ exists between politicians and journalists - that is, ‘where both parties are reliant on each other in order to get their work done properly’ (2015: 81).

This contention is explained through the statement: ‘Political actors often make official

statements through Twitter, where they “correct” publications they consider problematic. When doing so, they become media producers themselves who, in turn, use journalism as a source and vehicle for promoting their own agenda.’ (2015: 81).

Whilst it is true that Ekman and Widholm’s 2015 work focuses primarily on the interplay between politicians and the media, rather than issue-based campaigns and the media, given the nature of the EU referendum as an issue-based campaign led by politicians, advocating for political change, this thesis contends that the conclusions of Ekman and Widholm remain valid for this study.

Theoretically, it could be said to be the case, then, that the two EU referendum campaigns, through their activities on social media, became media producers in their own right - which used journalism both as a source and a vehicle for promoting their agendas.

The comparative nature of this study allows for an assessment of how the two campaigns approached this role of media producer, and what similarities and differences can be noted.

3.2 What impact can the media, including social media, have on

political discourse?

While this literature review has so far addressed mediatization in a broad sense, it has yet to discuss in detail how media, including social media, can influence political discourse.

When discussing this, it is first essential to reflect on the impact discourse can have on public opinion. Simon and Jerit address this directly when they contend ‘important models and studies imply that political discourse essentially determines public opinion’ (2007: 254). Whilst, Simon and Jerit, in their paper regarding the interplay between politics, the media and public opinion, argue that not every theory regarding the subject suggests political discourse impacts on public opinion, they also propose theories which dismiss a link between the two leave little room for an understanding of the evident role political leadership plays in society (2007: 254).

Given this, and similar arguments evident in Fan’s 1988 work on public opinion and the mass media, this thesis accepts that political discourse can impact on public opinion. The bigger question to be addressed is what impact media has on that discourse - whether it merely acts to report political discourse to the public, or whether it in some way impacts on that discourse. The former approach is illustrated in Fetzer and Lauerbach’s work on political discourse in the media, where, when describing the media using the analogy of a theatre performance, they state ‘the presentation of politics...takes place on the public stage that the media provides’ (2007: 5). The media acts, through this prism, only as a mechanism for politicians to communicate with the populace.

An articulation of the impact the media can have on public discourse, with a potential impact on the political, is evident in Simon and Jerit’s 2007 study on discourse and public opinion

regarding abortion. In this, data was collected on responses to public opinion surveys regarding critical political issues and segmented based on the individual media sources consumed by the individual. Simon and Jerit report, in their conclusion, that ‘media’s word choice drives citizens’ survey response’ (2007: 265 - 266). As well as potentially impacting directly on the discourse of politicians, Simon and Jerit’s research shows word choice in the media can impact on the discourse of individuals when dealing with political issues.

These theories are perhaps best understood when considered through the prism of Scheufele’s 1999 work on framing as a theory of media effects. In his piece, Scheufele describes how media postings can, both consciously and unconsciously, create ‘frames’ in which the thoughts of those who consume that media reside. By adopting this model for addressing questions around the media’s impact on political discourse, it could be seen that the media’s impact could be broader than merely affecting what people say - it could indeed be affecting what people think. Despite this, from the literature reviewed here, it is clear that academic opinion exists which suggests the media can have a profound impact on political discourse - either influencing the views of those who consume the media for political ends or even reshaping political debate altogether - media, including social media, is likely to have a significant role to play in shaping political discourse.

3.3 What impact can social media have on voter behaviour?

To properly study the Twitter output of the two Brexit referendum campaigns, it is vital to address issues around the impact social media has, not on just political discourse, but voter behaviour more directly. Lassen & Brown (2010) address this directly in their paper on how campaign strategists now use social media to target voters directly, while some studies have directly attributed the 2012 electoral success of Barack Obama in the USA Presidential Election of that year to his online strategy (Tumasjan et al. 2011). In a similar vein, social media’s rise to prominence in elections has been noted in Britain, with Arthur’s 2010 work suggesting that the UK Parliamentary elections of that year were the ‘first social media elections’ (2010).

To adequately address this issue, however, it is essential first to develop a theoretical basis, to scrutinise claims around the efficacy of social media in impacting on voter behaviour.

The work of Tolbert and McNeil (2008) is useful in this regard, given their focus on the internet and social media as a tool for gathering political information. Through their study, they contend that access to the internet - and through it, social media - provides a new avenue for political information gathering and that this new avenue builds a populace who are better informed, and therefore more likely to participate in the political process.

Another study exploring a similar issue was that of Kushin and Yamamoto (2010). This study focussed on establishing if social media had an impact on political involvement in the 2008 US Presidential election. Their study illustrated that between 1996 and 2008, the percentage of Americans who were exposed to political information online increased from 4% to 40% and that this growth in the internet as a resource for political information was more profound in younger generations. To illustrate this, focussing on social media particularly, the study suggested that 27% of those under the age of 30 read campaign information regarding the 2008 US

that way (2010: 612). Of course, this study relates to an election eight years before the 2016 Brexit referendum, but it nevertheless offers an interesting perspective on the growth of social media as a resource for consuming political information.

It is clear, then, that social media is increasingly used by voters to consume information.

However, what this thesis has yet to do is ascertain whether social media can directly impact on voter behaviour.

Previously, researchers have attempted to establish whether likes and followers on social media had a positive correlation with electoral performance (Towner & Dulio, 2012). One such

example of this was the Cameron, Barrett and Stewardson’s study of the Twitter and Facebook accounts of New Zealand politicians (2016). This study compared electoral success with the performance and social media accounts and concluded that while there was a positive

relationship between social media presence and electoral success, it was a relatively small one. In the United States, studies have instead considered whether the real impact in voter behaviour social media precipitates is increased on the ground campaigning and activism (Smith, 2013). Perhaps then, alongside the direct impact of impacting on voters who are consuming

information, the secondary impact of social media is generating further campaign activity. The question of impact on voter behaviour from social media engagement has also been studied at a local level, for example, through Moss, Kennedy, Moshonas and Birchall’s (2015) study. This study, which focussed on the digital engagement of public sector organisations in the United Kingdom, found that the public sector organisations could use social media as a platform to gather data, which allowed the organisations in question to amend their approach and see better engagement outcomes. It is not difficult to see how this learning could be applied to the question of voting - with social media’s function being not just one for a campaign to distribute information and persuade supporters, but also to gather information on what messaging is attractive and what isn’t, thereby allowing the campaign to develop over time. Ultimately, several conclusions can be drawn when it comes to the question of social media impacting on voting behaviour. First, a growing number of voters rely on social media channels to gather political information. What is not clear from that fact, however, is whether this is impacting directly on voter behaviour. On this question, the literature is less clear. Cameron, Barrett and Stewardson’s 2016 study of New Zealand politicians suggested a relationship existed between social media popularity and electoral success - the more friends / followers and interactions a politician had - the better they did in elections. However, this relationship was found to be a weak one.

A more tangential approach was suggested by Smith’s 2013 work, with the idea that the real impact social media had was stimulating more ‘on the ground’ campaigning - less directly influencing voters, but having an indirect influence on them through potentially exposing them to

Birchall in their 2015 work on digital engagement are worth noting - that perhaps one impact of social media on voter behaviour comes from interactions on social media platforms providing political campaigns with better quality information on public mood, allowing them to adjust their approach accordingly.

In summary, several different theories have been proposed in terms of social media impact on voters - from the direct to the indirect. However, given the reality of a populace which engages more with political content through social media than ever before, from the literature reviewed, it seems likely that some form of impact is taking place.

3.4 What motivates voters to participate in elections and

referendums?

To formulate a plan to investigate why people chose to participate in the EU referendums, it is necessary to discuss previous academic work concerned with voter turnout. More specifically, it is important to discuss both works which focus on general theories discussing why voters participate in any election and works more tightly focused on referendums themselves. As such, this literature review proposes to provide critical analysis of arguments proposed dealing with the question: Why do people vote?

In terms of beginning a discussion of theories of turnout, it is immediately important to consider Downs' Theory of Rational Choice (1957). This is best articulated through Riker and

Ordeshook's discussion of the mathematics behind Downs' theory (1968: 25). They postulate the following formula, to explain the Rational Choice view of voting:

R = (BP) - C

In this formula, R represents the utility an individual one gains from the act of voting, B the individual utility gained from the success of the individual's supported candidate winning, P the probability that a citizen will bring about B by their vote, and C the cost of voting.

While this literature review will not undertake a detailed review of the maths behind Downs' theory (articulated by Riker and Ordeshook), it is worth briefly considering the implications of this formula. In particular, the variable P, the probability of bringing about the value B through an individual act of voting. Immediately, this can be assumed to be an insignificant value, as

relatively few elections are decided by one vote.

As such, this leads to the conclusion that the (BP) section of the formula would result in a

B would rationally represent a large number. As such, while C can be assumed to be relatively constant, and not particularly high, the formula would still nearly always result in R being a value less than 0, so an individual would not gain any utility from voting. As Rational Choice Theory suggests that all human behaviour is engaged in to maximise utility, this theory appears to suggest that voting is always irrational, and seemingly predicts a turnout of 0%.

Despite this flawed initial appearance, Rational Choice theory is still worth discussing, due to a refinement made to Downs' theory by Riker and Ordeshook. They conclude that R = (BP – C) cannot properly represent human behaviour. However, instead of abandoning Rational Choice theory, they instead revise the formula, and suggest this:

R = (BP) – C - D

Note the new variable D. D is defined as the following 'satisfactions': ● The satisfaction from compliance with the ethic of voting

● The satisfaction from affirming allegiance to the political system ● The satisfaction from affirming a partisan preference

● The satisfaction from deciding, going to the polls, etc

● The satisfaction from affirming one's belief in the efficacy in the political system (Riker and Ordeshook, 1968: 28)

It is possible to imagine how, with the addition of the D variable, Downs' Rational Choice Theory could explain (or at least help to explain) reasons for voting. In particular, the 'satisfactions' introduced in variable D could be measured to see if they do have an impact on voting.

While Rational Choice theory addresses certain parts of this enquiry, particularly regarding the reasons voters have for participating in elections in a broad sense, it does not provide clarity on what may drive voters to behave differently when participating in a referendum. Addressing this question, Jacobs explains 'Referendum research trying to explain why referendum voters vote what they vote mainly focuses on three interrelated topics: the role of political discontent, cues and referendum-specific factors.' (2018: 489).

Addressing these in turn, it is first essential to consider the role political discontent can have on voter behaviour in referendums. In their seminal 1980 work on contrasting voter behaviour between different elections, Reif and Schmidt explain that "There is (in Europe) a plethora of 'second-order' elections: by-elections, municipal elections, various sorts of regional elections, those to a 'second chamber' and the like. The specific significance of these lies in the particular arena in which public positions are filled according to the respective electoral outcomes.

Side-effects of these outcomes are nevertheless felt in the main arena of the nation. Many voters cast their votes in these elections not only as a result of conditions obtaining within the

specific contest of the second-order arena but also on the basis of factors in the main political arena of the nation' (1980: 8-9).

This notion of 'second-order elections' is key to understanding issues around referendum turnout, with Reif and Schmidt's 1980 work categorising referendums as one such second-order election.

Taking a slightly different approach, Denver explains that 'The electorate, then, differentiates between different levels and types of elections. In general, these variations can be explained by the importance that is attached to the body being elected' (2007: 26).

However, while Reif and Schmidt and Denver both support the idea that patterns of turnout can be considered different between first and second-order elections, it is immediately apparent that their explanations of why this is the case are incompatible. After all, Reif and Schmidt assert that many voters cast their vote because of national-level factors, seeming to suggest that votes for second-level elections are merely a reaction to the performance of first-level bodies. On the other hand, Denver appears to be suggesting that the difference in turnout between first and second level elections are more related to the value which people place on the first and second level bodies. This leads to conflict, as it is possible to imagine a situation where, under Denver's theory, a powerful second-level body is considered more important than a weak first level organisation, yet according to Reif and Schmidt, voters would still turnout because of first-order concerns.

Following on from the contradictions in explanations between Denver and Reif and Schmidt, it is possible to identify how other literature suffers from a similar division. In particular, Rallings, Thrasher and Denver assert that second-order election results are 'interpreted as reflecting a national response to national concerns and hence are viewed as reliable indicators of the current popularity of the parties among the electorate' (2005, p. 393). Perhaps, however, this is not quite as strong an assertion as that of Reif and Schmidt, in any case.

After all, Rallings, Thrasher and Denver assert only that second-order results are 'interpreted as reflecting a national response to national concerns', rather than plainly saying that second-order results do reflect a national response to national concerns.

Much academic work around political discontent driving voter behaviour in second-order elections appears to relate primarily to second-order contests where politicians are elected, rather than referendums. However, unambiguous conclusions can be drawn from the literature. First, as illustrated above a consensus exists that many voters are driven to participate in second-order electoral contests, at least partially, because of political discontentment at a national level. Second, questions of value persist - voters are more likely to participate in a second-order electoral contest if they perceive the political body they are either electing representatives to or voting on the future of, is one with power and value.

Concluding this line of enquiry, then, voters appear to choose to participate in referendums partially because of national political discontentment, and partially because of the value the voter places on the body / issue that the second-order electoral contest relates to.

Moving back to Jacobs' 2018 work, it is still important to address two other factors he identified as driving referendum participation - cues and referendum specific factors.

A significant amount of academic literature, including Donovan and Bowler's 1998 work on participation in referendums and Colombo and Kriesi's 2017 study addressing partisan voter behaviour in direct democracies addresses the notion of 'cues'. In short, the 'cue' is the direction given to the voter by their political party of choice to vote in a certain way in a referendum. In summarising their study, Colombo and Kriesi explain 'We found that both policy arguments and party cues have an independent effect on voting intention. This means that voters do not blindly follow their party's line: their decisions are also affected by policy arguments. However, we also found strong evidence for partisan-biased processing of policy arguments. This means that, during the referendum campaign, voters tend to align their arguments with their preferred party's position. In other words, voters in the referendums we analysed did pay attention to policy arguments. However, during the referendum campaign, they came to agree more and more with the arguments supported by their preferred party.' (2017: 2).

The notion that cues, to an extent, drive voter behaviour - with partisan voters giving regard to policy issues but processing them through the partisan prism of their political party of choice, is echoed in Donovan and Bowler's 1998 work.

This does raise something of a question when addressing the 2017 referendum, however. After all, no Great Britain based-party with more than two Members of Parliament advocated leaving the European Union in the 2016 referendum. The United Kingdom Independence Party (Ukip) had secured 12% of the vote in the 2015 United Kingdom General Election, however, no other party which scored more than 1% in that election supported leaving the EU.

The theory of cues, at least in terms of the 2016 Brexit referendum, may then need to be considered through the prism not just of the question of leaving the EU, but of other issues raised through the referendum - and how these related to existing partisan preference. For example, taking Colombo and Krieisi's work, their overall contention seems to be that voters will consider issues independently, then align their arguments with their preferred party's position. However, were a referendum campaign to take issues not directly related to the matter at hand - leaving the EU, in this case - but issues which closely matched the partisan preferences of voters in terms of topics such as immigration or the economy, it appears to follow that the theory of cues could suggest focussing on those topics through the referendum could significantly influence voter behaviour.

Finally, it is crucial to address referendum specific factors. These factors can be split into two major categories. First, the actual issue being discussed, as illustrated in Hobolt's 2009 work on European immigration. Second, the efficacy of the referendum campaigns, as per Bernard (2012) and Farrell and Schmitt-Beck (2003). To take the former, Hobolt explains that studies find that referendum voters "do consider the issue at stake" and "make use of the information provided by parties and the campaign environment" (Hobolt 2009: 249). Discussing the latter, Bernard's 2012 work addresses how the strategy employed by a referendum campaign - and the quality of its output - can have a significant impact on voter behaviour.

To refer back to the original question posed at the start of this question - what motivates voters to participate in elections and referendums? - several conclusions can be drawn from the literature. First, Rational Choice theory suggests people may vote to secure a 'satisfaction' - whether that is a satisfaction in affirming allegiance to the political system, the satisfaction of expressing a preference, the satisfaction in the act of choosing, or the satisfaction in expressing one's belief in the efficacy of the political system.

If generating personal satisfaction is one driver for choosing to participate in elections, the nature of referendums as second-order elections is also crucial for considering why people choose to vote. The literature studied illustrates how people may choose to vote particularly in referendums as they offer a mechanism for expressing their views on the national government, and for articulating the value they place on the body which the referendum / election relates to. Finally, partisan preference in terms of validation of each voter's existing ideas, the actual issue at stake, and the quality of the campaign, all also appear to play a role in determining voter behaviour.

3.5 How do propaganda and ‘fake news’ play a role in political

communications?

‘The so-called ‘fake news’ crisis has been one of the most discussed topics in both public and scientific discourse since the 2016 U.S. presidential campaign.’ (Egelhofer and Lecheler, 2019: 97). ‘Fake news’ is a term which seems to almost dominate media discourse in 2019 - barely a week seems to go by without it being referenced by Donald Trump in his press conferences or debated on major news channels.

Given the regularity of debate around the topic, and the regular linking of the election of Donald Trump and Brexit (Dodd, Lamont and Savage, 2017), to properly study the Twitter posts of the two Brexit campaigns, it is important to address what impact their content could have - through the prism of both fake news, and more traditionally, propaganda.

This section of the literature review will begin by assessing the facets of the concept of

propaganda and the impact it has on voters, then discuss modern theories around fake news. Qualter, in his work on opinion manipulation in western democracies, defines propaganda as being ‘The deliberate attempt by the few to influence the attitudes and behaviour of the many by manipulation of symbolic communication’ (1985: 124). Meanwhile, O’Shaughnessy and Baines offer the insight that to some, propaganda simply referred to ‘any term with which we disagree’ (2014: 2). They go on to, perhaps more helpfully, suggest that ‘Propaganda is often a)

simplistic, b) didactic’ (2014: 3).

From these definitions, we can theorise that propaganda as an attempt by a small number of people to influence the many through communication - communication which is often simplistic and designed to inform. It could also be suggested that propaganda really is any communication with which we disagree, however pursuing that avenue of enquiry may be of limited utility for this thesis.

In their work on propaganda, O’Shaughnessy and Baines go on to categorise forms of propaganda into the following:

Type of Propaganda Explanation

Propaganda of enlightenment The negation of false information Propaganda of despair The inducement of fear and death and

disaster

Propaganda of hope Presenting to the enemy the hope of a better life if they cease hostilities or surrender

Particularist propaganda Seeking to divide the enemy into individual groups and attack them separately

Revolutionary propaganda Aiming to break down an enemy from within

Integration propaganda Aims at unifying and reinforcing society Agitation propaganda Aims at fomenting revolution within

society

Atrocity propaganda Material containing graphic images of an adversary’s savage or barbaric behaviour

sympathies towards the propagandist Sociological propaganda The penetration of an ideology into a target

audience through its sociological context Political propaganda The penetration of an ideology into a target

audience through its political context Vertical propaganda That propaganda which makes use of the

mass media

Horizontal propaganda That propaganda made by a central organisation which disseminates it for use by small groups

Source: O’Shaughnessy and Baines (2014: 3)

Whilst it is clear that many of the forms of propaganda outlined above are not relevant to a study on Brexit related tweets, the propaganda of enlightenment, despair, political propaganda and vertical propaganda may be of interest for this research study. Particularly, propaganda which seeks to either negate false information, create fear, promote an ideology or leverage the mass media all appear relatively likely as potential forms of communication that the two Brexit

campaigns could’ve employed.

When it comes to fake news, definitional problems exist. Egelhofer and Lecheler explain that ‘research has begun to show that ‘fake’ news is often understood as news one does not believe in – thereby blurring the boundaries between facts and beliefs in a confusing digitalized world’ (2019: 98). This argument is also advanced by Nielsen & Graves (2017), amongst others. Egelhofer and Lecheler do, however, go on to suggest that ‘There is the fake news genre, describing the deliberate creation of pseudojournalistic disinformation, and the fake news label, namely, the instrumentalization of the term to delegitimize news media’ (2019: 98).

Questions of the role of propaganda in terms of influencing discourse and voting patterns are broadly dealt with in sections 3.1 - 3.4 of this literature review, through the prism of general impacts on voter behaviour and political discourse.

However what is clear from the literature is that certain forms of propaganda do exist, which may manifest themselves in the review of the two Brexit campaigns’ tweets. This will be

addressed as part of the research results in section 5 of this thesis. Likewise, section 5 will seek to address examples of what could be considered ‘fake news’ promoted by the campaigns - either the dissemination of disinformation, or the delegitimization of the news media.

3.6 Literature Review Summary

To build an academic basis for this research project, this review sought to assess literature focussed on topics relating to the interplay between media and politics - with a particular focus on how media can affect political discourse and voting behaviour, what drives people to participate in elections, and the role propaganda and fake news can play in political communications.

From this review, a number of conclusions can be summarised. First, the work of Ekman and Widholm (2015) and Deacon and Stanyer (2014), amongst others, provides a conceptual basis for the notion of the two Brexit referendum campaigns as media producers in their own right - the idea of mediatization. This theory allows us to conclude that the conduct of the two campaigns on Twitter at least partially reflects their role as media producers in a mediatized world. A conclusion which allows for the Twitter output of the two campaigns to be considered through the prism of their media impact.

As section 3.1 of this review established the theory of the two campaigns as ‘media producers’, sections 3.2 and 3.3 addressed more directly the impact media can have on politics - in section 3.2 on political discourse, and section 3.3 on voting behaviour. Section 3.2, through the work of Simon (2007) and Jerit and Fan (1988) focusses on political discourse, with Scheufele’s 1999 work on ‘framing’ also playing a role here. Through studying literature relating to impact on discourse, it becomes increasingly apparent that, whilst debate on exactly what form this media impact on political discourse takes, there is a relative consensus that the media does affect political discourse.

Similarly, section 3.3, studying impact on voter behaviour more directly, suggested a relative academic consensus on the topic. Whilst the exact notion of potential impact varies - from Towner & Dulio’s 2012 work on the relationship between social media followers and electoral performance to Smith’s 2013 study on social media as a mechanism to stimulate more

traditional political campaigning, studies appear to suggest that social media can and does, to some degree, impact on voter behaviour.

Section 3.4 reviewed voter behaviour more directly, seeking to take the findings from sections 3.1 to 3.3 - as to how the two Brexit campaigns could be considered ‘media’, and how media can impact on both political discourse and voter behaviour - then reviewing more fundamentally why people choose to participate in elections and referendums. This began with a review of Downs’ 1957 work on Rational Choice theory, before discussing Riker and Ordeshook’s 1968 proposed revisions of that theory. By taking that general research into what drives people to vote, in particular questions of generating personal satisfaction, and adding more detailed literature on the nature of referendums, a number of conclusions were drawn.

First, if generating personal satisfaction is one driver for choosing to participate in elections, the nature of referendums as second-order elections is also key for considering why people choose to vote. The literature studied illustrates how people may choose to vote particularly in

referendums as they offer a mechanism for expressing their views on the national government, and for articulating the value they place on the body which the referendum / election relates to. Together with this, partisan preference in terms of validation of each voter’s existing ideas, the actual issue at stake, and the quality of the campaign, all also appear to play a role in

determining voter behaviour.

Finally, having discussed the theoretical framework for both the campaigns as media, how they may impact on politics, and what drives people to vote the way they do, this review, in section 3.5, assessed propaganda and conceptions of ‘fake news’. Discussing the work of, amongst others, Egelhofer and Lecheler (2019), Dodd, Lamont and Savage (2017) and O’Shaughnessy and Baines (2014), the literature illustrated that certain forms of propaganda do exist, which may manifest themselves in the review of the two Brexit campaigns’ tweets across sections 5 and 6 of this thesis.

The overall conclusions of this literature review will be reflected in section 6 of this thesis, where the research outcomes detailed in section 5 of this thesis will be contrasted against the

4. Methodology

Before comparatively assessing tweets between the two Brexit campaigns, it was essential to identify exactly which Twitter accounts to scrutinise. Given the significant interest in the Brexit debate, as outlined throughout this thesis, and the corresponding social media content

generated on the issue, sampling from two Twitter accounts which could be fairly compared was identified as an essential first step in developing a research methodology.

In April 2016 the United Kingdom Electoral Commission reviewed applications from different organisations to be designated as the official leave and remain campaigns. Securing this designation would grant a campaign £600,000 in state funding, and allow for a further £6.3 million to be legally spent ahead of the date of the referendum (Stewart, 2016).

This designation process led to the selection of Stronger In as the official remain campaign, and Vote Leave as the official leave campaign. Stronger In was the only body to apply for official designation as the remain campaign, whilst Vote Leave faced competition from the Nigel Farage backed Grassroots Out! (BBC, 2016).

Whilst Grassroots Out! did undertake a notable Twitter campaign (Usherwood and Wright, 2017), due to the comparative nature of this study they were excluded from the scope of this study as no equivalent ‘second’ remain campaign operated.

4.1 Research Strategy

To address the questions outlined in section 2.1, building on the outcomes of this thesis’s literature review, this thesis makes use of the Content Analysis approach. Taking the work of Skalski, Neuendorf and Cajigas (2017), this research project focusses on cataloguing tweets posted by the two official Brexit campaigns (Stronger In and Vote Leave) on the dates outlined below. These dates were chosen to offer an insight into the communications approach of both campaigns at key moments through the referendum campaign:

● 13 April 2016: the announcement of the Official Referendum campaigns (Stewart, 2016) ● 7 June 2016: the first major televised debate, in which Prime Minister, David Cameron

(remain) and leader of the UK Independence Party, Nigel Farage (leave), took part in consecutive interviews broadcast on ITV (Kirkup, Daley and Samuel, 2016)

● 15 June 2016: first airing of BBC Question Time ‘EU Special: The Case for Leave’ ● 22 June 2016: Final day of campaigning and the broadcast of ‘Europe: The Final Debate

with Jeremy Paxman’ on Channel 4 ● 23 June 2016: Polling day

This strategy, therefore, utilises a non-probability, purposive sampling approach. As Tansey explains, ‘the basic assumption of purposive sampling is that with good judgement and an appropriate strategy, researchers can select the cases to be included and thus develop samples that suit the needs of the study’ (2007: 18). Put briefly, to develop the sampling strategy, the above dates for data collection were selected using the judgement of the researchers - with the researchers applying their judgement and understanding of key dates within the Brexit

campaign to select suitable dates for sampling.

To ensure the samples taken accurately reflected the output of those two dates, and to avoid, as Tansey explains ‘selection bias can easily be introduced (in non-probability samples), compromising the possibility of arriving at robust findings and generalisations’ (2007: 14), the sampling took the form of recording every tweet posted by both campaigns on those two dates. This approach then allowed the researchers to apply their existing understanding of the Brexit referendum process, and to remove the risks Tansey explains in terms of other forms of sampling leading to potentially misleading data, or data which fails to account for significant events (Tansey, 2007), whilst ensuring that researcher bias did not lead to sampling which failed to represent the output of the two campaigns accurately.

Developing this approach, the research strategy employed here was informed by the work of Castro, Kellison, Boyd and Kopak (2010), who explain there are three primary kinds of approach to mixed methods research which can be applied to content analysis:

● Sequential mixed methods - where data is collected sequentially, either qualitative or quantitative first, followed by the other

● Concurrent mixed methods - where both types of data are collected concurrently

● Integrated mixed methods - which seek to integrate qualitative and quantitative data as it is collected

Given the nature of this research, the study is based on the concurrent mixed methods approach. Notably, the concurrent triangulation strategy, where, as explained by Castro, Kellison, Boyd and Kopak, ‘the purpose of concurrent triangulation designs is to use both qualitative and quantitative data to more accurately define relationships among variables of interest.’ (2010: 3).

Applying the concurrent triangulation strategy to the overall content analysis approach allowed for the creation of a strategy that would sample the two campaigns’ tweets from both a

quantitative and qualitative perspective, and allow for a deeper understanding of the

relationships between the two types of data. It is such an approach that this study advocates for best answering the questions outlined in section 4.1 of this thesis.

Employing Burghardt’s 2015 work on analysing data from Twitter, this study adopted a three-stage approach to data collection. First, individual tweets were identified. Second, they

were annotated - marking their date, number of retweets, likes, hashtags and other vital data. Finally, they were analysed - with the researcher making a judgement as to what the key topics of the tweets were, and identifying keywords for further analysis. Furthermore, the tweets analysed only included posts originating from the official campaign accounts - posts retweeted from other accounts were not considered as part of this study as, coming from a different account, it cannot be guaranteed that retweets fully reflect the messaging communicated by the official campaigns.

It is important to note that the strategy outlined here is predicated on a mixture of the inductive and deductive approaches. As explained by Collins, ‘an inductive approach means you will collect data and develop theory as a result of that data analysis’ (2010: 42). While Blaikie

defines a deductive approach as one beginning with a ‘tentative idea, a conjecture, a hypothesis or a set of hypotheses that form a theory’ (2007: 71).

This mixed approach has been selected in part because of the theories regarding the impact social media has on political discourse, as outlined in section 3. This research seeks to develop a greater understanding of the applicability of those theories through the Brexit referendum (the inductive approach) while offering space for new hypotheses to emerge through the analysis of data (the deductive approach).

In order to reduce subjectivity in this paper and offer a more objective perspective on the two campaigns, the sub-questions chosen analysis were selected in order to provide quantitative data on what were otherwise potentially qualitative themes. The use of qualitative data, such as likes, for social media analysis has been explored by Lipsman et al. (2012) who used such data to explore brand marketing and influence through Facebook. The social media efforts of the two official Brexit campaigns can be viewed as a form of brand reach and influence (albeit in a political rather than a commercial sense). Therefore, this paper applied a similar approach when selecting questions for the content analysis of Twitter posts. The use of more precise

sub-questions also ensured that a broad theme could be addressed whilst simultaneously providing answers to poignant questions within the scope of this paper.

The analysis of findings will follow a comparative methodology approach, described by Hall as the “search for systematic patterns of similarity and difference in the features of political systems transcending idiographic studies” (2003: 378). By presenting a comparison of the two

referendum campaigns, it is hoped that this paper may employ methods outlined by Mahoney (2007) in order to generate new hypotheses whilst avoiding the limitations highlighted by Lijphart (1971) through increasing the number of cases by means of a longitudinal extension. Adopting this strategy led to the creation of a codebook and data table, which are attached to this thesis as appendices.

4.3 Research Paradigm

Having identified a research strategy and approach, it is essential to address the theoretical paradigm in which the research process resides. Given the nature of this study as taking both a qualitative and quantitative approach, determining a paradigm upon which to understand the research findings is essential - as is ensuring that the ontological and epistemological underpinnings of such a theory render it suitable.

Blaikie, when discussing research paradigms, explains that ‘social researchers approach

research problems from different theoretical and methodological perspectives by using what are referred to...as research paradigms’ (2007: 109). Collins goes further, explaining that ‘a

paradigm can be thought of as a lens through which we view the world.’ (2010: 38).

As outlined in Blaikie’s 2007 work, it is evident that this study could use one of ten research paradigms to support the study outcomes - Positivism, Critical Rationalism, Classical

Hermeneutics, Interpretivism, Critical Theory, Ethnomethodology, Social Realism, Structuration Theory, Contemporary Hermeneutics and Feminism.

Having assessed these paradigms, interpretivism is the paradigm selected by this study. This decision was informed by a review of the literature discussing research paradigms and their relationship with both content analysis and the mixed methods approach, including Blaikie (2007) and Collins (2010). Collins explains that ‘interpretivism does not aim to report on an objective reality, but instead understand the world as it is experienced and made meaningful by human beings’ (2010: 39). Similarly, Blaikie explains that according ‘to interpretivism, the study of social phenomena requires an understanding of the social world that people have constructed and which they reproduce through their continuing activities’ (2007: 124).

Given the nature of this study, as one which seeks to understand the outcomes of human behaviour (in this case, the tweets of the two official Brexit campaigns), and the world in which the objects of study operate, the interpretivist approach, with its ontological and epistemological assumptions, seems suitable as a theoretical context in which to undertake this research. That is not to say other paradigms would not be necessarily suitable for this study, however, to take the example of Critical Rationalism, its focus on testing theories against reality (Blaikie, 2007) would not lend itself to the inductive approach laid out above. The nature of this study potentially inherently further reduces the utility of other paradigms such as Feminism and Critical Theory.

In summary, the interpretivist paradigm, with its focus on the world in which the subject of study operates, and the understanding of human experience, appears to tend itself well to this study.

4.3 Ethics

The ethical considerations involved in delivering this research are kaleidoscopic. Somekh and Lewin explain that ‘Ethical decisions are the result of a weighing up of a myriad of factors in the specific complex social and political situations in which we conduct research’ (2004: 56). Given the nature of this thesis as one which addressed a multifaceted and often controversial political issue, this statement felt particularly apt.

Given the authors of this thesis voted against Brexit in the 2016 referendum, and have individual political interests, it was ethically challenging to ensure the personal views of the authors were disaggregated from the research project itself. Somekh and Lewin address issues such as this in the ‘Ethics for the Researcher’ (2004: 58) section of their book, where they speak of the ethical dangers a researcher may face when studying a social context different from their own - as was the case for the researchers in this thesis when studying the tweets of campaigns with divergent political views. These ethical considerations are further discussed by Lee-Treweek and Linkogle (2000), in their work on the ethical dangers facing social researchers.

Sixsmith and Murray, in their 2001 exploration of the ethical issues around data analysis of internet posts, discuss further issues. They explain ‘the analysis of data and the consequent interpretation of meaning are not without their own ethical implications’ (2001: 12) when discussing the challenges of interpreting data gathered electronically from an online source. To summarise, ethical considerations when undertaking research such as this are evident. These take the forms of the researcher needing to consider the context the research is taking place in, the ethical dangers of research in an area in which they may have personal biases, and how these biases could impact on the interpretation of the data gathered. Similar critical ethical issues such as anonymity are not considered relevant in this study, given the public nature of the platform on which two Brexit campaigns promoted their messages.

5. Results

Theme 1: Engagement - How did the engagement of the two campaigns

compare?

To provide a comparative assessment of the Twitter posts of the Brexit campaigns, the analysis was divided into two themes, each of which generate a core research question. The first of these questions focuses on engagement. In the case of Twitter, as with all methods of social media, there are many different metrics that may be employed to measure engagement. In order to provide a structured and quantifiable approach, the first core question has been subdivided into four sub-questions. These questions will initially focus on the nature of how online engagement compared between the two campaigns. Next, the frequency of tweets will be analysed before considering the topics of each campaign which received the greatest levels of engagement. Finally, combining elements of the above, the changing engagement level witnessed across the course of the campaign will be analysed.

1. How did the online engagement compare between campaigns?

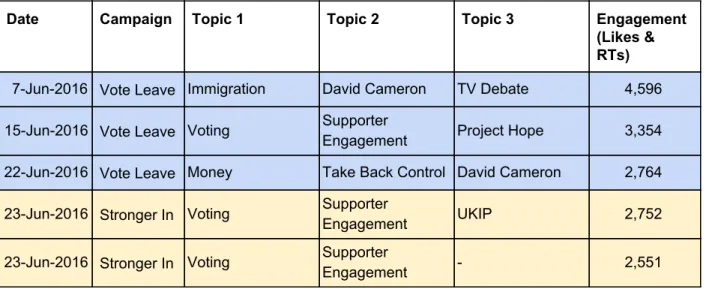

In answering this question it is first necessary to understand what is meant by the phrase ‘online engagement’. For the purpose of this thesis, ‘online engagement’ will be considered to be a combination of likes and retweets that each tweet received, with a numerical figure for engagement being derived by calculating the sum of the two. The table below (Figure 1)

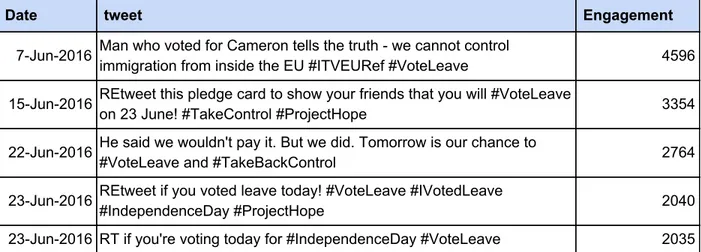

highlights the ten most tweets which received the greatest engagement alongside the key topics contained within each tweet.

Figure 1: Ten tweets to receive most engagement across the two campaigns.

Date Campaign Topic 1 Topic 2 Topic 3 Engagement

(Likes & RTs)

7-Jun-2016 Vote Leave Immigration David Cameron TV Debate 4,596 15-Jun-2016 Vote Leave Voting Supporter Engagement Project Hope 3,354 22-Jun-2016 Vote Leave Money Take Back Control David Cameron 2,764 23-Jun-2016 Stronger In Voting Supporter Engagement UKIP 2,752 23-Jun-2016 Stronger In Voting Supporter Engagement - 2,551

23-Jun-2016 Vote Leave Voting Supporter Engagement - 2,040

23-Jun-2016 Vote Leave Voting - - 2,035

22-Jun-2016 Stronger In Experts - - 1,931

22-Jun-2016 Vote Leave Democracy Sovereignty - 1,831

23-Jun-2016 Stronger In Voting Jobs Rights 1,626

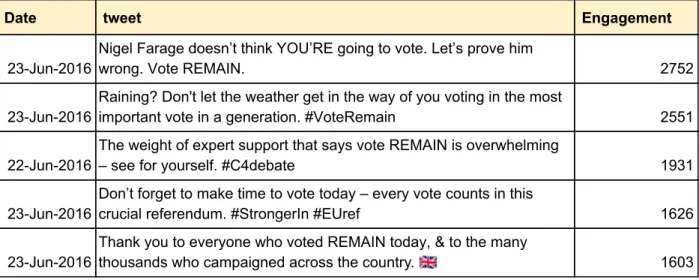

Perhaps the most immediate observation that may be drawn from the table is the fact that the three tweets to receive most engagement were posted by Vote Leave. Yet, given the fact that four of the top ten tweets were posted by Stronger In, one might assume a level of parity between the leave and remain campaigns when it comes to voter and supporter engagement. An interesting additional factor to consider is that remain supporters on Twitter were more likely to like a tweet - despite the most liked tweet of the referendum campaign being one being by Vote Leave, six out of the ten most liked tweets were posted by Stronger In. By contrast, the data sampled demonstrates a greater readiness amongst Vote Leave supporters to retweet posts - seven out of the ten most retweeted posts came from the Vote Leave account, including all of the top five. The tables below (Figure 2) offer a comparative view between the likes and retweets that each of the official campaigns received.

Figure 2: Ten tweets to receive most likes and the ten tweets to receive most retweets across the two campaigns.

Date Campaign Likes Date Campaign Retweets

7-Jun-2016 Vote Leave 2424 15-Jun-2016 Vote Leave 2179 23-Jun-2016 Stronger In 1579 7-Jun-2016 Vote Leave 2172 23-Jun-2016 Stronger In 1529 22-Jun-2016 Vote Leave 1513 22-Jun-2016 Vote Leave 1251 23-Jun-2016 Vote Leave 1217 15-Jun-2016 Vote Leave 1175 23-Jun-2016 Vote Leave 1185 23-Jun-2016 Stronger In 1164 23-Jun-2016 Stronger In 1173 23-Jun-2016 Stronger In 1077 7-Jun-2016 Vote Leave 1122 23-Jun-2016 Stronger In 921 22-Jun-2016 Vote Leave 1121 23-Jun-2016 Vote Leave 850 22-Jun-2016 Stronger In 1104 22-Jun-2016 Stronger In 847 23-Jun-2016 Stronger In 1032

This subtle difference between the Twitter activity of the supporter of the two campaigns may offer an insight into the wider performance of the two campaigns in the run up to an on polling

a like is generally used as an expression of agreement or at least acknowledgement that a tweet has been read. On Twitter, likes (a term adopted from Facebook) were previously referred to as favourites and can also be used to log tweets that a user may wish to return to in the future - a 2014 study (Warzel, 2014) “one of the most complex and cryptic forms of online communication”.

On the other hand, retweets are a reposting of another tweet. This makes the original tweet immediately visible to the retweeters followers as well as the people who follow the account which posted the original tweet. As a result, unlike the more passive like, retweets can be described as an active form of twitter use and demonstrate greater engagement in the original tweets as “users must be excited to spread a message to their own followers in order to retweet a post” (Encore, 2015)

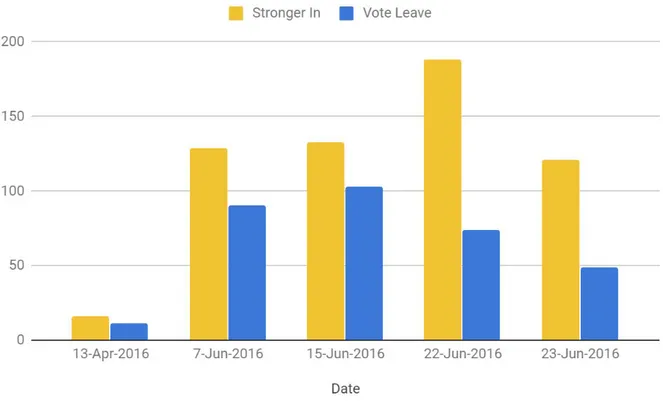

Another factor that should be considered is the average engagement achieved by each of the campaigns. Although the top ten most liked tweets suggest similar levels of engagement, looking at the average number of likes, retweets and total engagement across all of the tweets sampled tells a different story.

On the days sampled, Vote Leave posted a total of 327 tweets whereas Stronger In posted 588. One impact of this dramatic difference in the number of tweets posted becomes apparent when considering the average engagement for each campaign (calculated by dividing the sum total engagement for all tweets by the number of tweets posted). Whilst Vote Leave gained an average of 217 retweets and 181 likes (a total engagement score of 398), Stronger In only received an average of 93 retweets and 84 lives (an engagement score of 177). This disparity can be put down to the fact that Stronger In posting significantly more low-performing tweets, the poorest of which had an engagement score of nine (six retweets and three likes).

In summary, whilst both campaigns had a similar level of reach (due primarily to the fact they were the official campaign organisations for a nationwide referendum that drew international coverage). This reach is demonstrated by the comparable figures achieved in terms of total engagement in the most popular tweets in the run up to the referendum. However, the nature of this engagement suggests a difference in behaviour between the Stronger In and Vote Leave campaigns. Vote Leave supporters appear to have been more engaged in the campaign - willing to retweet posts to their own followers and engage with more of the campaign’s tweets, leading to a significantly higher average engagement score. On the other hand, Stronger In supporters appear to have been more passive in their support (liking rather than retweeting), perhaps an indicator of lower level of engagement in the campaign message.

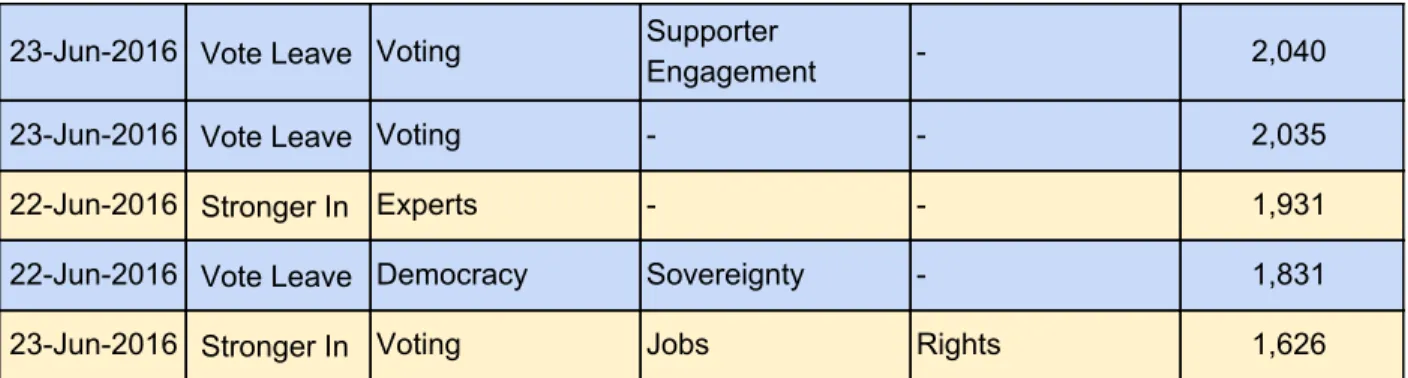

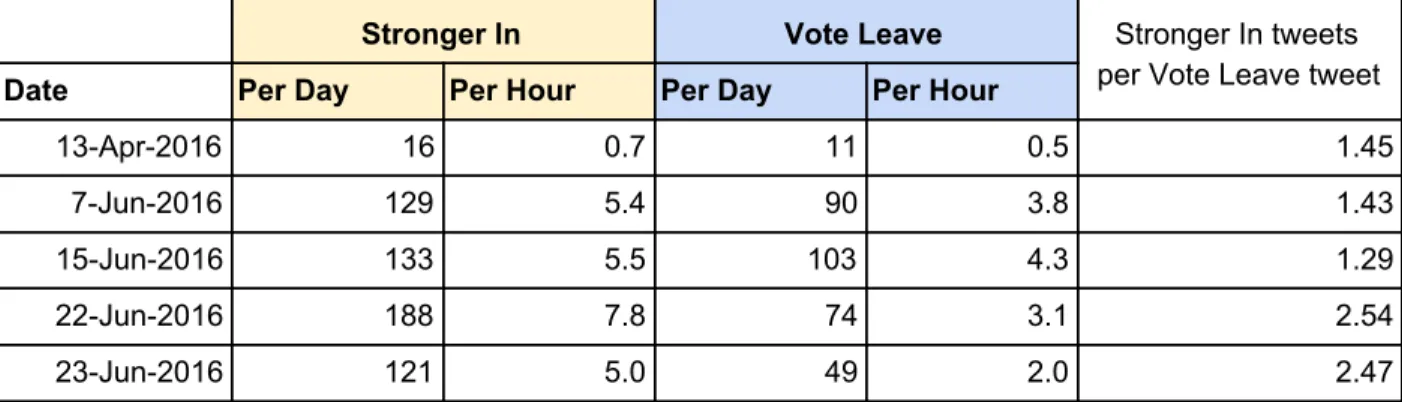

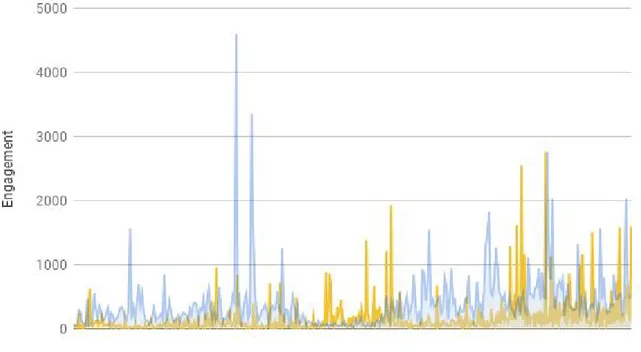

2. How does the frequency of tweets compare between the two campaigns?

As highlighted in the research analysis articulated so far, there is a significant disparity in the number of tweets posted by the two campaigns. The Stronger In campaign tweeted 587 times on the five days sampled whilst in the same period of time the official Vote Leave Twitter account posted only 327 times.

The point at which this difference became most pronounced was at the end of the campaign. On both the final day of polling and the day of the referendum itself, Stronger In tweeted around two and a half times as many times as Vote Leave.

Figure 3: A comparison of the number of tweets posted by the two campaigns on each of the days sampled.

The graph above visually demonstrates the number of tweets posted by each of the campaigns and clearly shows that Stronger In posted far more than Vote Leave. The comparatively low number of tweets on the 13th April 2016 may be attributed to the fact that that was the day on which the official campaigns were announced and the campaigns were yet to get fully

underway. By the 7th June 2016, both campaigns were in action and frequently posting tweets, although even at this stage the difference between Stronger In and Vote Leave was becoming apparent. The former posted 129 tweets on that day whilst the latter posted 90. The following week, on the 15th June, the story was much the same with the remain campaign tweeting 133