Challenges in Challenging Menstrual Discourse

An Inquiry into the Nature of Dominating Social Discourse on

Menstruation, and the Human Rights Agenda to Challenge its Effects

Antonia Sophia von Buttlar

Human Rights Bachelor of Arts 15 credits

Spring semester 2020 Supervisor: Mikael Spång

ABSTRACT

Recent developments have seen a rise in empirical attempts to challenge the persistently negative sociocultural attitudes toward menstruation. The thesis proposes a Foucauldian feminist conception, as well as the identification of the three elements stigmatization, medicalization and commercialization, to provide a comprehensive theoretical framework conceptualizing dominant menstrual discourse and its effects, based on which the empirical contemporary UN human rights agenda on the topic is approached. The findings, methodologically arrived at through the means of Directed Content Analysis, thereby generate both, an understanding of strengths and weaknesses in contemporary empirical attempts to challenge the effects of dominant menstrual discourse on women, and an exemplification of the utility of social science theory for human rights research in the realm of menstruation. Most importantly, the theoretical framework on dominant menstrual discourse indicates the need of holistically addressing all three formative elements, in order not to risk a perpetuation of its effects.

Keywords: Menstrual Discourse, Stigmatization, Medicalization, Commercialization, United

Nations Human Rights Agenda.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

LIST OF ABB REVIATIONS ... 1

1. INT RODUCTION ... 2

1.1INTRODUCTION TO THE TOPIC ... 2

1.2INTRODUCTION TO THE THESIS ... 3

1.2.1 Research Context a nd Gap ... 3

1.2.2 Research Aim and Contribution to the Field of Human Rights ... 3

1.2.3 Research Question ... 4

1.2.4 Delimitations ... 5

1.3CHAPTER OUTLINE ... 6

2. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK: DOMINANT MENSTRUAL DISCOURSE... 6

2.1MACRO DIMENSION:AFOUCAULDIAN FEMINIST CONCEPTION ... 7

2.2MICRO DIMENSION:THREE FORMATIVE ELEMENTS... 8

2.2.1 The Stigmatization of Menstruation... 9

2.2.2 The Me dicalization of Menstruation ...11

2.2.3 The Commercialization of Menstruation ...14

2.3DOMINANT MENSTRUAL DISCOURSE THEORY AND ITS IMPLICATIONS ...17

3. METHODOL OGICAL FRAMEWORK ...18

3.1METHOD ...19

3.1.1 Directed Conte nt Analysis...19

3.1.2 Methodological Research Context ...19

3.2RESEARCH DESIGN ...20

3.2.1 Qualitative Research...20

3.2.2 Case Study Design ...20

3.3METHODOLOGICAL LIMITATIONS ...21

3.4DATA COLLECTION AND CODING...21

3.4.1 Sampling of Material ...21

3.4.2 Operationalization and Coding Frame ...23

4. ANALYSIS: UN HUMAN RIGHTS ENTITIES’ MENSTRUAL AGENDA ...25

4.1PART I:DCAFINDINGS ...26

4.1.1 Element I: A Unanimous Call for De-Stigmatization ...26

4.1.2 Element II: A Divergent Use of Medicalized Language...28

4.1.3 Element III: An Ambiguous Account of Commercialization Critique ...29

4.2PART II:ASSESSMENT...31

4.2.1 Relating Findings and T heory: Correlations and Discrepa ncies...31

4.2.2 The Danger of Perpetuating the Effects of Dominant Me nstr ual Discourse...32

5. CONCLUSION ...34

5.1ANSWERING THE RESEARCH QUESTION ...34

5.1.1 The way in which UN human rights e ntities approach menstrua tion, … ...34

5.1.2 …and how this may be understood...34

5.2RESEARCH EVALUATION AND IMPLICATIONS ...35

5.3OUTLOOK:FUTURE RESEARCH ...36

1

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

CEDAW United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against

Women

ECOSOC United Nations Economic and Social Council

DCA Directed Content Analysis

MHM Menstrual Hygiene Management

OHCHR United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights

UN United Nations

UNESCO United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

UNFPA United Nations Population Fund

UNGA United Nations General Assembly

UNHRC United Nations Human Rights Council

UNICEF United Nations Children’s Fund

UNSR United Nations Special Rapporteur

UN Women United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women

2

1. INTRODUCTION

“How a society deals with menstruation can reveal much about how it perceives women.”

(Lahiri-Dutt, 2015:1166).

1.1 Introduction to the Topic

Over the course of life, women and girls1 spend approximately 3500 days menstruating (Zivi,

2020:119; Winkler & Roaf, 2014:3). While menstrual bleeding is part of the natural monthly experience of around a quarter of the world’s population (Winkler & Roaf, 2014:3; Newton, 2012:394), the prevailing sociocultural attitudes on menstruation still constitute a source of gender inequality, oppression, and the denial of dignity (Johnston-Robledo & Chrisler, 2011:14; UNICEF, 2019:13). Accounts of menstruation-related exclusion of women from full social participation, together with the persistence of social prejudices on the matter, continue to dominate the way in which societies worldwide deal with menstruation (Zivi, 2020; Jackson & Falmagne, 2013; Patterson, 2014; Johnston-Robledo & Chrisler, 2011). This reiterates the fact that the natural process of cyclical discharge of blood constitutes a topic not only of biology, but more significantly, one of social construction with an effect on women’s physical and psychological well-being (Newton, 2012:392).

Recent trends show an increasing recognition of this social realm in which menstruation continues to pose an obstacle for women to equality: Not only did growing numbers of social activists lately become concerned with challenging the detrimental effects resulting from negative sociocultural attitudes toward menstruation, but moreover, international development agencies and human rights entities integrated the goal of challenging negative social discourse in their agendas. Recent third wave feminist movement, for instance, includes both radical activism and moderate advocacy in approaching the topic through civil society engagement (Patterson, 2014:105-106). Moreover, international development entities include menstruation in their so-called “WASH” agenda (Winker & Roaf, 2014:11; Lahiri-Dutt, 2015:1158&1163; Bobel, 2018:297-298), and the UN Human Rights Committee has recently issued the first ever explicit recognition of the necessity to address persisting negative social norms on menstruation in an authoritative document, due to their detrimental impact on the enjoyment of fundamental human rights (A/HRC/RES/39/8:preamble & para.8(e)).

1 Most of the contemporary empirical and academic approaches to the topic of menstruation consider it to be one of girls’ and women’s experience. However, as Zivi has argued, menstruation is not necessarily a female realm, but includes experiences of individuals in the LGBTQ community (Zivi, 2020:120). Nevertheless, as the research to be undertaken in this thesis relates to the UN human rights approach to menstruation, which has mainly been framed in terms of it as a women’s rights issue, I will use the category of “women” when speaking about menstruating individuals for better clarity (as done by Zivi, 2020), while recognizing the existence of non-female individuals among menstruators.

3

1.2 Introduction to the Thesis

1.2.1 Research Context and GapWhile the aforementioned recent developments in terms of the recognition of the need to challenge persisting negative social discourse on menstruation show the increasing acceptance of the topic’s importance, there continues to be a general lack of scholarly research in the area. The review of literature within the field shows that there is research on how the dominating discourse on menstruation affects women2, how it is entrenched in sociocultural attitudes and

furthered by economic entities3, and how this has historically and contemporarily been

challenged by feminist and international development entities4. However, the concepts used to

analyze menstruation are rarely connected to each other, resulting in the lack of a comprehensive approach to the topic. Moreover, theoretical concepts on discourse were not taken up by human rights literature on the topic. Instead, this literature continues to approach the topic in legal and philosophical terms, rather than through the theoretical lens of menstrual discourse 5. Due to this gap in research, a lack of theory-based analytical assessment by human

rights scholars, in terms of their evaluation of the current empirical human rights entities’ engagement with the effects of the persisting discourse on menstruation, can be identified.

1.2.2 Research Aim and Contribution to the Field of Human Rights

Based on the identification of this lack of theory-based research in the understanding of contemporary human rights entities’ agenda in the realm of menstrual discourse, the research

problem underlying this thesis is how the dominating social discourse on the topic of

menstruation can be theoretically characterized, and how the way in which its effects are currently challenged may be understood.

Thus, what is aimed to be achieved is the contribution of a comprehensive theoretical framework characterizing both the dominating discourse and its effects, the provision of a theory-based assumption on the elements which need to be addressed by empirical actors in their approach to challenge these effects, and the analysis of the way in which this is undertaken within the contemporary agenda of UN human rights entities.

2 Inter alia, Bra nsen, 1992; Ja ckson & Fa lma gne, 2013; Lee, 1994; Shipma n Gunson, 201 0; de Wa a l Ma lefyt &

McCa be, 2016; Kissling, 1996; Oina s, 1998, Pa tterson, 2013&2014.

3 Inter alia, Johnston-Robledo & Chrisler, 2011; Ma cDona ld, 2007; Kissling, 1996; Winkler & Roa f, 2014; Zivi,

2020; Newton, 2012, Merskin, 1999, Pa tterson, 2013&2014.

4 Pa tterson, 2014; Bobel, 2006,2008,2019; Johnston -Robledo & Chrisler, 2011. 5 e.g. Winkler & Roa f, 2014; Hennegen, 2017; Zivi, 2010.

4 Not only will this thesis thereby contribute to existing scholarship on menstruation in discourse, by providing a conceptualization thereof through the use of previous accounts, but moreover, it will aim to provide a comprehensive account and the theoretical tools to assess contemporary engagement by empirical human rights entities in the area. Thereby, it will be possible to identify strengths and weaknesses of this engagement, which may have been neglected by previous human rights scholarship’s assessments in the field.

Thus, the purpose of this research lies in the connection of menstrual discourse research and the empirical dimension of human rights. The assessment of the case of UN human rights entities’ dealing with the topic of menstruation will moreover provide the basis for future human rights research in the realm of menstrual literature. In this sense, this thesis will provide an account of “how the society [currently] deals with menstruation”, namely on the example of how entities in the empirical human rights realm deal with the topic, in accordance with the opening assumption of this chapter that this may “reveal a great deal about how it perceives women” (Lahiri-Dutt, 2015:1166; Kissling, 1996:482).

1.2.3 Research Question

Given the identified research gap and problem, the following more specific research question can be proposed:

How is the topic of menstruation approached in the contemporary agenda of UN human rights entities, and how can we understand this approach based on a theoretical conceptualization of the dominating social discourse on menstruation?

Two steps will be necessary to answering this two-part question. The first part relates to the establishment of an analytical account of the way in which UN human rights entities currently

approach the theme in their agenda, based on the identification of a lack of research in this area.

To do so systematically, a comprehensive theoretical framework conceptualizing the character and elements of dominant menstrual discourse will be proposed . On this basis, the analysis will be undertaken, and an understanding of the findings will be generated in accordance with the second part of the research question. In accordance with this two-fold analytical process, first the establishment of a theoretical understanding, and second the identification and assessment of the empirical UN human rights agenda in their approach to menstruation, the research will be able to fulfil its aims to contribute to not only to the “intellectual conversation” on the topic (Luker, 2008:52), but more importantly, will contribute to the raising of awareness for the

5 necessity of assessing the ways in which contemporary entities challenge the discursive ef fects through a theory-based analytical approach.

1.2.4 Delimitations

Two main delimitations relating to the overall aims and the proposed research question can be stated to provide a consistent analytical account6.

First, based on the aim of providing a comprehensive theoretical framework conceptualizing the effects, manifestations and overall character of the dominant discourse on menstruation, there are some natural limits to the discussion of each theoretical concept to be introduced: It can be recognized that the theoretical propositions on how one may understand this discourse will derive from a range of theoretical concepts in the research context, all with their own theoretical origins, including Foucauldian discourse theory, feminist theory, socio-psychological theories and socioeconomic Marxist theory. While each of these theoretical concepts may thus follow different logics, e.g. in their understanding of power and resistance (Jones et al, 2011), the aim will be the provision not of a theoretical discussion, but of a theory-based analysis of an empirical case. Thus, in order to meet the aims of this research in a consistent and straightforward way, the comprehensive discussion of the exact relations and contradictions among the concepts to be introduced will be alleviated by the proposition of an overall underlying Foucauldian feminist understanding, and theoretical discussions exceeding this understanding will be left for future research to be taken up. Second, the thesis is limited to the consideration of the empirical case mostly in terms of the proposed social science theoretical framework to provide a convincing analytical account, which might omit legal and philosophical human rights literature related considerations on the analytical findings - for instance, in terms of the more pragmatic and practical mechanisms of rights claiming and balancing of possible dangers entailing strategic decisions. While this delimitation may make the undertaken research of this thesis less closely connected to some traditional discussions in human rights scholarship, the provision of a theory-based analysis may simultaneously exceed the existing literature by identifying possible strategical flaws currently not taken into account in human rights literature. This limitation will thus henceforth be considered a strength, and aim, of this thesis, rather than a weakness.

6

1.3 Chapter Outline

The following second chapter will provide the theoretical framework through which the empirical case will be approached and understood. This will be undertaken by conceptualizing dominant menstrual discourse through the identification of its character given in previous literature within the field (chapter 2), by generating a Foucauldian feminist macro dimension of conceptualization (chapter 2.1), and a micro dimension of characterization that will propose the elements of stigmatization, medicalization and commercialization to be formative of the discourses’ manifestations and effects (chapter 2.2). Based on this theory, it will be proposed that a holistic addressing of each of these elements seems necessary to comprehensively challenge the persisting menstruation-related oppression of women (chapter 2.3). Subsequently, Directed Content Analysis (DCA) will be introduced to underly the methodological approach to the empirical case of UN human rights entities’ challenging efforts (chapter 3). To provide a comprehensive understanding of method and research design choices, a brief delineation of methodological research context, research design aspects, and methodological limitations will be established (chapters 3.1,3.2,3.3), followed by the more specific display of sampling and operationalization (chapter 3.4). Lastly, the findings of the conducted analysis will generate the theory-directed account of the way in which the UN human rights entities contemporarily approach the topic of menstruation (chapter 4.1), and how these results can be understood based on assessment both in terms of theoretical and contextual implications (chapter 4.2).

By doing so, this thesis will provide a comprehensive and applied theoretical account of how the detrimental effects of the dominating social discourse on menstruation are challenged through the contemporary human rights agenda, and will thereby be able to establish both, some more practical case-specific implications, and the basis for future research in the field.

2.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK: DOMINANT MENSTRUAL

DISCOURSE

In this chapter, existing scholarly literature within the field will be reviewed to identify the key elements to the dominant menstrual discourse7.

7 The to revea l the cha ra cter of “dominant discourse on menstrua tion” is limited to a discourse dominant within

the Globa l North, a s most of the schola rs who ha ve written within the resea rch field ha ve been concerned with Western societies a nd their discourse. However, a ccounts by non-Western schola rs show the a pplica bility of ma ny of the a spects identified within the hereina fter proposed theoretica l fra me work (e.g. La hiri-Dutt, 2015), which is why a more extensive considera tion of possible fla ws in this respect will be left to future resea rch, a nd the a ccount given here will be proposed to esta blish a first step for future concern with the topic.

7 This will be done by approaching the theme of menstrual discourse from a macro to a micro dimension of characterization: First, a more general Foucauldian feminist theoretical conception of discourse will be introduced as underlying the understanding of dominant menstrual discourse (2.1). Second, three formative elements of this discourse will be identified to provide a more concrete understanding of its inherent mechanisms: stigmatization, medicalization, and commercialization (2.2). And finally, implications of this theoretical framework underlying the approach to the empirical case of the contemporary UN human rights entities’ menstrual agenda will be forwarded, in order to propose a comprehensive understanding of the theoretical framework and its use for the analysis (2.3).

2.1 Macro Dimension: A Foucauldian Feminist Conception

Given the interest in dominant menstrual discourse, this indicates the social science theory camp this theoretical framework relates to: Poststructuralism and its preoccupation with discourses. The poststructuralist assumption that knowledge and language systems produce reality, and the understanding that discourses, as “system[s] of meanings, practices, and values that organize social life and individual experiences” (Wetherell in Jackson & Falmagne, 2013:385), have the power to constitute the individual itself, underlies this thesis’ theoretical approach to menstruation as a discursive realm (Jones, Bradbury & LeBoutillier, 2011:110-112). Theoretically, the interest in characterizing the dominant menstrual discourse thus derives from the assumption on the existence of a social discourse around menstruation that regulates the way in which individuals and society act upon menstruation, through the generation of knowledge about it: Due to the powerful mechanisms underlying discourses, it has been argued that to be able to challenge them, “dominant” social discourses with negative effects on individuals need to be “discovered” to be properly understood (Jones et al, 2011:113). The discovery of the mechanisms and features of the dominant menstrual discourse is the aim of a number of scholarly studies within the menstrual social science research field, and their findings will hereinafter be identified in order to generate the conceptual basis for the approach to the way in which UN human rights entities are currently attempting to challenge it.

In the realm of menstrual discourse, the understanding of dominant discourses as powerful in their creation of knowledge is enriched by the theoretical concepts underlying Foucauldian feminist scholarship, which is the main scholarly camp preoccupied with the discovery of this discourse and its features. Foucauldian feminist theory, the hybrid of Michel Foucault’s contributions on the “productive” power-knowledge interplay underlying social discourses, and the feminist understanding of society as being structured through patriarchal power exercised

8 by “men [to] dominate, oppress and exploit women” (Walby in Jones et al, 2011:182), operates under the assumption that “discourses regulate women’s body and personality” and thus effect the construction of female identity (Jones et al, 2011:111&189; Manokha, 2009:430; Foucault, 1997:38). In accordance with these conceptions, dominant menstrual discourse can be considered to comprise such powerful mechanisms, and thereby contribute to the social and individual perception of female identity (Jackson & Falmagne, 2013:380 Lahiri-Dutt, 2015:1170): In terms of Foucauldian theory, menstrual discourse is part of the “body politics”8

disciplining and regulating the individual in modernity, through the constitution of a system of knowledge internalized and acted upon9 by the subjugated female individual, as well as its

social environment (Jones et al, 2011:111-114; Patterson, 2014:95-96; Lahiri-Dutt, 2015:1171; De Waal Malefyt & McCabe, 2016:556; Newton, 2012:399-401; Lee, 1994:344-345)10. In other

words, the dominating social discourse on menstruation, which has been characterized as “highly negative” in its conveyance of knowledge about this natural biological process, has been found to affect the way in which women create their individual and social identity through the experience of their menstruating body (Jackson & Falmagne, 2013:380 Lahiri-Dutt, 2015:1170; Patterson, 2014:97; Johnston-Robledo & Chrisler, 2011:13). Or to cite Patterson, “through [the] internalization of the panoptical [menstrual] gaze […], women self-objectify and self-police their bodies, resulting in disciplined attempts to avoid the public spectacle of bleeding femininity” (Patterson, 2014:97) .

2.2 Micro Dimension: Three Formative Elements

Based on the preceding macro-understanding of dominant menstrual discourse and its mechanisms, three elements will be introduced to provide a more detailed “micro -understanding” thereof. Utilizing Patterson’s theoretical account (2013&2014) as the so-called “nodal point” for the theoretical framework proposition of this thesis (Luker, 2008:84-85), the concepts of stigmatization (2.2.1), medicalization (2.2.2), and commercialization (2.2.3) will be discussed in relation to menstruation, and suggested to be formative of dominant menstrual discourse. In the context of this theoretical proposal, the term “dominant” corresponds not to a homogenous and static discourse, but is rather understood as a dynamic interplay of its formative elements in their variations and disparities across time and space, and relates to the aforementioned phrasing of the assumption that “dominant discourses must be discovered”

8 Refers to Fouca ult’s theory on the “biopower”, consisting of “a na tomo-politics” a nd “bio-politics”, Fouca ult,

1978; Fouca ult, 1997; Fouca ult, 1975; Jones et a l, 2011; Pa tterson, 2014.

9 Refers to the Fouca uldia n concepts of self-surveilla nce, self-policing a nd pa nopticism. 10 Fouca ult, 1975; Fouca ult, 1978; Fouca ult, 1997.

9 (Jones et al, 2011:113). The “discovery” of the three elements will provide a more holistic understanding of the exact knowledge on menstruation conveyed through this discourse, the manifestations and origins of the resulting social construction of menstruation, as well as its consequences and effects on the female subject. This will constitute the conceptual basis for the analytical approach to the empirical case of interest in this study.

2.2.1 The Stigmatization of Menstruation

It is widely agreed that menstruation is closely associated with social stigmatization11. As

Patterson points out, the concept of stigmatization can be assigned to the “social-psychological” realm of “theoretical micro-analyses” and “symbolic interactionalism” (Patterson, 2013:4). It has been used by – predominantly feminist – scholars to increase the understanding of the way in which social attitudes on menstruation influence women’s own sentiments toward their menstruating bodies and selves, thus serving the establishment of accounts on women’s internal experiences of menstruation. In this theoretical framework, the concept of menstrual stigma will be included for two reasons: Firstly, to draw a better picture on how social stigmatization of menstruation affects women in their perception of the self. And secondly, to establish it as a formative element in the proposed theory on dominant menstrual discourse, which will both deepen the feminist-foucauldian characterization given already, and provide an aspect to be conceptualized for the analysis of UN human rights entities’ menstruation-related agenda. According to Ervin Goffman (1963), the term “stigma” goes back to the ancient Greek practice to brand slaves and criminals with physical marks in order to display their “devalued” status and spoil their identity, leading to social distancing and avoidance (Patterson, 2014:93; Johnston-Robledo & Chrisler, 2011:9). Goffman introduces three categories of stigmatization:

1. “Abominations of the body” through “physical scarring and deformities”, 2. “Blemishes of individual character”, e.g. psychological disorders,

3. “Tribal stigmas […] attributed to marginalized groups based on characteristics, [including] gender”. (Patterson, 2014:93)

These categories can be considered the manifestation of stigmatization, thus providing the basis for an understanding of the way in which social stigma is revealed, and the levels of stigmatization that can exist. As Patterson (2013&2014) points out, a stigmatic condition can either be “visibly observable”, leading to direct social discreditation, or “deeply concealed and

11 Inter alia McCa be, 2016; Ja ckson & Fa lma gne, 2013; Johnston -Robledo & Chrisler, 2011; Kissling, 1996;

La hiri-Dutt, 2015; Lee, 1994; Ma cDona ld; 2007; Ma mo & Fosket, 2009; Merskin, 1999; Newton, 2012; Pa tterson, 2014; Winkler & Roa f, 2014; Zivi, 2020; Oina s, 1998; Bobel, 2018.

10 invisible” when there is a “social environment of potential discreditation” which requires the stigmatic individual to strive for the best possible concealment of her potentially socially discrediting mark (Patterson, 2014:93; Johnston-Robledo & Chrisler, 2011:10). Thus, while social stigmata may be “enacted” or “felt” (Scambler in Newton, 2012:394), it can be concluded that in both cases, they would affect the stigmatized individual’s social actions.

As mentioned before, it is consensually agreed upon in scholarship that menstruation is an area of stigmatization, which can be interpreted through the Foucauldian feminist lens as an aspect of knowledge on menstruation conveyed through d ominant menstrual discourse. Myths and prejudices around menstruation, such as the belief that menstruating individuals have dark magical powers or are poisonous, have been found to be integral to cultures of most societies around the world (Patterson, 2014:97-99; Merskin, 1999:944; Zivi, 2020:120). Anthropological studies identified the function of superstitious beliefs around menstrual bodies as one of patriarchal power and female subordination, creating social order by women’s exclusion from meaningful social participation (Patterson, 2014:98-99, Merskin, 1999:944).

This socio-historical account of menstruation may explain the origins of the contemporary persisting social stigmatization of menstruation in accordance with the stigma theory by Goffman. In application of his aforementioned account, menstrual blood can be considered a “stigmatizing mark” matching all three of Goffman’s categories: bodily abomination is given through the social perception that menstrual blood is “repugnant”, that it “taints women’s femininity” and constitutes an “emblem of contamination” (Patterson, 2014:94; Johnston-Robledo & Chrisler, 2011:10). The blemishing of identity is established by negative social reactions like distancing and avoidance to the leakage of menstrual blood, thus to the visibilit y of the stigmatizing mark (Johnston-Robledo & Chrisler, 2011:10; Patterson, 2014:94). And a

tribal identity stigma is likewise given, due to the sole fact that menstruation is limited to the

female body and thus socially considered an indicator of womanhood, thereby marking the line between the two sexes (ibid).

Scholarly accounts on menstrual stigma have found this condition to be manifest both in public social discourse, and, resulting therefrom, in women’s own experience of menstruation. Most compellingly, menstrual stigmatization is manifest in the physical, linguistic, and theoretical taboo remaining around it (MacDonald, 2007:346-347; Zivi, 2020:120; Kissling, 1996:483; Patterson, 2014:98). Furthermore, social attitudes toward menstruation can be characterized as discriminating, which is e.g. visible in the frequent resort to the use of linguistic euphemisms like “the curse”, and the conveyance of negative stereotypes (Winkler & Roaf, 2014:3-6; Zivi, 2020:120; Johnston-Robledo & Chrisler, 2011:10-12; Merskin, 1999:944; Oinas, 1998:56;

11 Jackson & Falmagne, 2013:379-380). This discursive stigmatization can be said to further, and be furthered by, the way in which menstrual taboo is taught in sex education, which was found to be emphasizing negative experiences as well as the necessity of concealment, with the effect that the internalization of the knowledge of menstrual stigma is already undertaken at an early stage of life (Newton, 2012:397-398; Johnston-Robledo & Chrisler, 2011:11-12; Winkler & Roaf, 2014:3).

Not surprisingly, the consequences of the stigma on menstruation have been characterized as “negative for women’s health, sexuality, well-being and social status” (Johnston-Robledo & Chrisler, 2011:12), which is manifest in both internal and external restrictions of women’s behaviour: Women’s internal experiences are negatively shaped through “hypervigilance associated with concerns about the revelation of the menstrual status”, ”lowered self-esteem”, and feelings of “ambivalence” and “rejection” toward the own menstruating body (Oinas, 1998:56; Lee, 1994:347; Jackson & Falmagne, 2013:386-392; Johnston-Robledo & Chrisler, 2011:11-12). External restrictions include the social pressure for concealment, often resulting in the avoidance of certain social activities and general social participation12, which seems to

mirror the norms of silence and taboo conveyed through the menstrual stigma. Hence, menstrual stigma is both “felt” and socially “enacted”, and thereby contributes to the inferior social position of women within society (Johnston-Robledo & Chrisler, 2011:4).

Stigmatization can thus be concluded to constitute a formative element of the dominant menstrual discourse established, based on a Foucauldian feminist conception: It produces a knowledge about concealment and social sanctioning manifest in the public sociocultural attitudes and internalized by women, and thus transmits the power working within and through this discourse by shaping female identity both in its internal psychological and in its external social realm.

2.2.2 The Medicalization of Menstruation

A second underlying aspect of dominant menstrual discourse commonly identified in related scholarship13 is medicalization. Medicalization can be considered a theoretical Foucauldian

feminist hybrid, which, in contrast to stigmatization, has been applied to menstrual discourse within the “theoretical macro-analytical”/”macro-discursive” (Patterson, 2013:19) social realm of power and language. It is commonly used to explain the more specific ways in which women

12 For more deta iled ela bora tions, see Winkler & Roa f, 2014; Zivi, 2020; Johnston -Robledo & Chrisler, 2011. 13 Inter alia Bra nsen, 1992; Shipma n-Gunson, 2010, de Wa a l Ma lefyt & McCa be, 2016; La hiri-Dutt, 2015;

12 relate to their menstrual body, and the power dynamics underling this relationship. Accordingly, the inclusion of medicalization extends the conceptual understanding of the effects and mechanisms of dominant menstrual discourse beyond stigmatization: Firstly, it provides an additional, explicitly Foucauldian feminist, understanding of how stigmatized menstrual discourse manifests itself and the power dynamics it entails. And secondly, its inclusion provides the grounds for the establishment of a more in-depth characterization of the exact features of dominant menstrual discourse.

Medicalization can be defined as “the rendering of life experiences as processes of health

disorders, which can be discussed in medical terms only and to which only medical solutions can be applied” (Bransen, 1992:98). In addition to this rather general definition, Foucauldian

feminist theory provides a more extensive understanding of medicalization as the “power of the

medical gaze in modernity” and medical discourse as “among the most important modern discourses regulating social and individual bodies” (Jones et al, 2011:114-116).

In accordance with the Foucauldian feminist understanding of menstrual discourse provided before (see 2.1), the specific medicalized discourse within the menstrual realm can be seen as constituting one of the power-transmitting discourses regulating and disciplining bodies (Foucault, 1997:244; Jones et al, 2011:114; Shipman Gunson, 2010:1325). Moreover, an important characteristic of medicalization can be identified to be the assumption of the hegemonial role medical institutions play in the normalization of knowledge, by defining illness and health, which can be considered “analogous [to the definition of] right and wrong” (Foucault, 1997:244; de Waal Malefyt & McCabe, 2016:559; Shipman Gunson, 2010:1325; Jones et al, 2011:114). In his work “The Birth of the Clinic” (1994), Foucault “provides an understanding of medical knowledge not as objective facts but as belief systems shaped through social and political relations” (Lupton, quoted in Shipman Gunson, 2010:1325). Medical discourse is assumed to work on subjugated individuals through a “gaze” internalized and complied by (Jones et al, 2011:114-116; Shipman Gunson, 2010:1325), a mechanism presumed to be underlying dominant menstrual discourse. Thus, medicalization theory and its Foucauldian feminist assumption on the creation of a knowledge on right and wrong, normality and deviance, provides a better understanding of the way in which the dominant menstrual discourse works on the female subjugated individual, despite the social stigmatization identified before. In Foucault’s own words, “hysterization of women […] involved a thorough medicalization of their bodies and their sex” (Foucault, 1998:146-147), thus contributing to the social construction of female identity (Bransen, 1992:98).

13 More specifically, it can be pointed out that menstruation, as an aspect of female bodily identity and social gender-related discourse, can be considered a prime example of a medicalized discourse in the Foucauldian feminist sense of it, visible already in its historical emergence: In contrast to the long history of stigmatization, the emergence of menstrual medicalization correlated with the emergence of those social discourses Foucault has identified to be related to the modern age of biopower. As Patterson genealogically traces, the shift in the approach toward menstruation as understood in medical terms took place at the end of the 19th century,

when (male) medical experts became the main authoritative educators of the female “medical condition” (Patterson, 2014:99-100). Thus, by the 20th century, pathologization and a powerful

hygiene discourse came to substitute alternative menstrual management means (Lahiri-Dutt, 2015:1163; Kissling, 1996:481-482). This development can be seen in connection with the overall Foucauldian understanding on the rise of scientific and medical language used in modernity as a means to overcome previous religious beliefs and superstitions under the umbrella of facts and objectivity, concealing however simultaneously the d isciplinary and all-encompassing power inherent in this new discourse of modernity (Foucault, 1975:99; Foucault, 1997:244; Jones et al, 2011:114-116).

Findings of scholarly analyses around the contemporary manifestation of the medicalization of menstruation reveal its persistence in the discursive framing of menstruation as “the feminine handicap” and a “medical condition” (Patterson, 2014:99), thus making the “menstrual cycle […] a key area identified by feminists as having been medicalized” (Shipman Gunson, 2010:1326). Evidence for that is manifold: For instance, medicalization was discovered in the way in which medical institutions, as continuing “omnipotent” sovereign expert authority of menstrual education (Oinas, 1998:58-65; Kissling, 1996:481), convey the information on menstruation. Furthermore, menstruation is commonly framed as a “hygienic problem that needs to be managed”, with strong emphasis on cleanliness (Newton, 2012:398), which implies for menstrual blood as an uncontrollable bodily function to be dirty and unclean – a “matter out of place” (Lupton quoted by Newton, 2012:400). In combination with medical descriptions that “privilege the male gender and diminish the female gender [such as the portrayal of] menstruation as the ‘failure’ of an egg” (de Waal Malefyt & McCabe, 2016:568), the knowledge transmitted about menstruation thus involves the creation powerful norms affecting women’s experience of their bodily identity.

These effects, just like the effects of menstrual stigmatization, include internal and external restrictions on women. For instance, the internalization of medicalized knowledge about menstruation, such as the perception that menstrual blood is “unhygienic” and “dirty”,

14 frequently results in the relation to the own menstrual body as “gross” and “disgusting” (de Waal Malefyt & McCabe, 2016:566). And the determination of menstruating as deviance from the male norm (Johnston-Robledo & Chrisler, 2011:14) potentially leads to a diminished self-conscience with “powerful implications for gender relations” (Shipman Gunson, 2010:1324). Despite these psychological effects, medicalized knowledge also translates into direct practices, such as the reliance by women on medical experts to learn about menstruation, thus letting the “medical gaze” govern their relationship to the own body, which was found to exemplify the mechanisms of the Foucauldian concept of the “technologies of the self” (Oinas, 1998:53-58). Further external effects are, again, the concealment of hints to the menstrual condition in order not to be exposed as socially “norm-deviating”, thereby making the medicalization of menstruation as restraining in its effects as stigmatization. Generally, the connection of stigmatization and medicalization in the realm of dominant menstrual discourse can be considered one that is mutually reinforcing, since the stigma-related taboo and resulting silence on the topic of menstruation reiterates the impression of menstruation as deviating from the medical norm (Newton, 2012:399). Likewise, the medicalized language on menstrual hygiene and (un)cleanliness can be said to reiterate the social stigmatization of menstruation by constituting a new modern form of social stigma in the Foucauldian sense; substituting old myths with scientifically framed normalizing knowledge (Foucault, 1978:139; Foucault, 1997:246; Foucault, 1975:99; Jones et al, 2011:111).

It can therefore be concluded that the medicalization of menstruation not only constitutes a prime example of Foucauldian feminist power and discourse theory, but also a key element shaping and generating the features and effects of dominant menstrual discourse. In combination with stigmatization, medicalization thus provides an increased understanding of the mechanisms of dominant menstrual discourse, and will hence be integrated as a formative element in the theoretical framework proposed to establish the basis for an analytical approach to the contemporary empirical case of interest.

2.2.3 The Commercialization of Menstruation

The third theoretical concept to be identified from the literature on menstrual discourse is the concept of commercialization. Belonging to Marxist feminist power theory, this element can be attributed to the “theoretical macro” realm of “materialist” socio-economic approaches (Patterson, 2013:32). In the context of menstrual discourse, scholars14 have been using the

14 Inter alia, La hiri-Dutt, 2015; de Wa a l Ma lefyt & McCa be, 2016; Merskin, 1999; Kissling, 1996; Winkler &

15 concept of commercialization to analyze the ways in which the capitalist corporate economy gains profit out of women’s menstrual cycle, thereby giving insight into the role of the economy as a carrier and actor within the mechanisms of dominant menstrual discourse. The assumptions around the commercialization of menstruation will likewise be included to contribute to an increased understanding of how social discourse works on women within the menstrual realm, and to complement the theory of dominant menstrual discourse as comprising stigmatization and medicalization mechanisms, in order to provide a deep and holistic comprehension of its workings to be utilized in the later analysis.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, commercialization means “to render something

commercial, make a matter of trade; to subject to commercialism” (Oxford English Dictionary

webpage). Patterson adds that the related commodification concept is the “process of

transforming objects, ideas and even people’s labour power into exchange values”, thus

integrating them into the capitalist economic system (Patterson, 2013:32).

The theory underlying commercialization is one deriving from a Marxist perception of society, assuming the existence of social conflict generated through the capitalist economic mode of production (Jones et al, 2011:39). Patterson, who provides the link between stigmatization, medicalization and commercialization in the realm of menstruation, introduces the commercialization of menstruation by stating that “the drive for profit makes any labour and goods potentially commodified for profit” (Patterson, 2014:101). In accordance with that, Marxist feminism is concerned with the economic system as an origin of women’s social inferiority (Jones et al, 2011:177). The role of advertising and product marketing language in reinforcing the related socioeconomic ideology15 is considered detrimental to women by

conveying powerful messages, which are internalized by individuals and thereby shape their sense of identity and make femininity a commodity (Merskin, 1999:942-943; De Waal Malefyt & McCabe, 2016:556-557; Jones et al, 2011:39-41). Thus, the Marxist feminist theory around the effects of the commercialization provides an increased understanding of the mechanisms of dominant discourse in the menstrual realm.

More specifically, the rising importance of “femcare industry” through the commercialization of menstruation has been revealed to be closely connected to the previously introduced medicalization of menstruation and its focus on hygiene. This is due to the related arising need for clean menstrual materials, which created the possibility for a “lucrative investment” and the

15 As this would exceed the fra me of this cha pter, the concept of ideology within its Ma rxist theoretica l rea lm

will not be defined. Ra ther, a n understa nding combining the tra ditiona l Ma rxist theory with a Fouca uldia n understa nding of ideology a s inherent in a nd working through powerful public discourses will be relied on.

16 potential of a market of prospective consumers encompassing around a quarter of the world’s population (Winkler & Roaf, 2014:3; Patterson, 2014:101). Historically, it has accordingly been argued that the commercialization of menstruation correlates with the terminology of “feminine hygiene”, which became part of the advertising language after World War I, and stayed ever since (Patterson, 2014:101-104; Merskin, 1999:947-948). Through the introduction of “menstrual hygiene” products on the market, and the extensive advertising of them in mass media (Patterson, 2014:102-104; Merskin, 1999:947-948), women’s relationship to their menstruating body became increasingly “mediated by consumption” (de Waal Malefyt & McCabe, 2016:559). As Lahiri-Dutt moreover states, “pharmaceutical companies [continue to] preside over the feminine domain [of menstruation]” (Lahiri-Dutt, 2015:1161). Hence, the commercialization of the biological process of menstruation can be concluded to shape the way women experience their cycle, by connecting menstruation to the consumption of commercial goods necessitated through the socio-economic delegitimization of traditional menstrual management means not relying on capitalist merchandises (Lahiri-Dutt, 2015:1162).

Menstrual product advertising, and the related marketing efforts of corporate capitalist enterprises, thus transmit not only the economic capitalist structures and patriarchal exploitative mechanisms, but in relation to menstruation, they also further – and are influenced by – the workings of both, menstrual stigmatization and medicalization inherent in dominant menstrual discourse. Regarding stigmatization, the role of advertising has been emphasized as formative of the conveying of menstrual stigma in public discourse. Namely, ads depict menstruation as a “burden” in need of attention (Patterson, 2014:104), and stress the importance of concerns for secrecy and concealment through the characterization of menstrual products as “protection”, implying the threat of blood leakage as connected with the exposure of the stigmatizing condition, and the risk of shame of social embarrassment (Patterson, 2014:104; Merskin, 1999:941-954; De Waal Malefyt & McCabe, 2016:559; Newton, 2012:394-403; Winkler & Roaf, 2014:6; Johnston-Robledo & Chrisler, 2011:10-12). Likewise, corporate advertising has been found to mirror and further the stigma-related social taboo on menstruation, for instance by portraying blood with blue liquids, or through the use of allegorical images on product packages, which serves the concealment of the true reality of menstruation and implies the notion of menstruation as something to be kept secret (Winkler & Roaf, 2014:6; Johnston-Robledo & Chrisler, 2011:11). Similarly, medicalized discourse on menstruation can be considered to be furthered by product advertising: As stated above, the term “hygiene” continues to dominate in the labelling of menstrual products as “feminine hygiene products”, implying the existence of an unhygienic and dirty condition for which companies offer

17 treatment (Lahiri-Dutt, 2015:1161-1171). This was revealed to transmit classifications of bodily norm and deviance, the menstrual body being depicted as one in a “hygienic crisis”, in need to be rescued by the advertised product (De Waal Malefyt & McCabe, 2016:559).

For reasons of profit, menstruation thus has become commercialized with the effect of exploiting women economically through the pricing of disposable and unsustainable products and lack of alternative materials available through other means than consumption. More importantly, it leads to a furthering of the internal and external restrictive effects of stigmatization and medicalization on women. Thus, the commercialization of menstruation constitutes a third element of dominant menstrual discourse by providing an economic Marxist feminist inspired realm of understanding, thereby contributing to the establishment of a holistic account of the mechanisms and effects of this discourse.

2.3 Dominant Menstrual Discourse Theory and its Implications

In combination, the Foucauldian feminist understanding of menstruation as socially constructed through a dominant menstrual discourse that powerfully conveys a certain knowledge internalized by the subjugated individual, and the three formative elements identified to generate an in-depth account of the specific mechanisms and effects of the discourse, constitute the theoretical proposal to be underlying the theoretical understanding in this thesis. In other words, the theory to go forward to the analysis of the empirical case is the understanding that menstruation is socially constructed through dominant menstrual discourse, and dominant menstrual discourse is constituted by the three formative elements of stigmatization, medicalization and commercialization. Based on the acknowledgement of their inter-relation, the conceptualization of the character of the dominant social discourse on menstruation can be understood as depicted in the figure below:

18 While it can be stated that not every one of the identified elements has been equally recognized in existing research interested in the discovery of dominant menstrual discourse16, Patterson’s

holistic account of all three elements (2013&2014) was utilized to propose their inherent interconnection. Thus, while it can be acknowledged that the elements vary across time and space, and may at times stand in independent or even contradictory relationships, it can also be re-emphasized that they inter-dependently coexist in the realm of the dominant menstrual discourse characterized in this theoretical framework. This clarification gives way for the theoretical assumption to be underlying the research interest and case investigation: Based on

the theoretical framework of dominant menstrual discourse as constituted in its effects by three inter-related formative elements, stigmatization, medicalization and commercialization, it can be assumed that empirical attempts to challenge this discourse need to holistically address each one of these elements equally, in order to effectively change the detrimental effects of dominant menstrual discourse on women.

Having thus conceptualized the research problem and question through an extensive review of literature on menstruation in discourse, the theoretical framework given in this chapter will be operationalized in the following methodological chapter to set the scene for the analysis.

3. METHODOLOGICAL FRAMEWORK

Based on the preceding conceptualization of dominant menstrual discourse, this chapter provides the methodological basis for approaching the case of UN entities’ menstrual agenda in relation to this theory. In the following pages, a two-step theory-guided directed qualitative content analysis (DCA) will be introduced as the method to approach empirical material related to the case of the UN menstrual agenda. The methodological basis of the research strategy choices underlying the thesis’ analytical process will thus be provided by introducing DCA method and locating it in the research context (3.1), discussing some distinct research design choices (3.2), and considering limitations inherent in method and research design (3.3). Subsequently, the specific implementation of DCA in this research will be introduced by presenting data collection related sampling criteria and the chosen material, as well as the operationalization of the theoretical framework for the analysis (3.4).

16 e.g. stigma tiza tion ha s been empha sized more in socio -psychologica l schola rship, medica liza tion in

19

3.1 Method

3.1.1 Directed Content Analysis

Qualitative content analysis, the systematic categorical sampling of data by coding and classification, delivers the tools for approaching, primarily textual and linguistic, data based on an interest in the finding of patterns deriving from an understanding that they are “indications of something else” (Boréus & Bergstrom, 2017b:24-25; Hsieh & Shannon, 2005:1278; Mayring 2000:5). In the interest in how UN human rights entities approach menstruation in their contemporary agenda, content analysis can therefore be considered to provide the instruments for a systematic approach to related material in its connection with the preceding theoretical framework: Using the systematizing process inherent in content analyses enables the approach to empirical material in direct relation to the three elements previously identified as underlying dominant menstrual discourse, in accordance with the aim of providing a theoretical account of the case of interest. This reliance on theoretical concepts for the systematization indicates the specific type of qualitative content analysis relevant to this research: a directed content analysis (DCA), as proposed by Hsieh and Shannon (2005). DCA is theory-guided, meaning that the coding frame (see 3.4), as a core step in the conducting of content analyses, is guided by theoretical considerations, which provide the main categories of analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005:1281-1293).

3.1.2 Methodological Research Context

In consideration of alternative methodological choice that could have been made, it seems relevant to locate this study within the methodological research context. Literature concerned with the research area of menstruation as a socially constructed phenomenon in discourse can be identified as having predominantly approached empirical material by conducting discourse analyses, mostly with the aim of revealing certain invisible features and forces underlying the dominant menstrual discourse, furthered by the discursive acts of different actors, and internalized by the subjugated individual17. While this choice of method seems appropriate for

their discovery aims, the analysis undertaken in this research relates to dominant menstrual discourse as a given: Through the reviewing of secondary literature, the character of dominant menstrual discourse was identified not only generally, as understood in Foucauldian feminist terms, but also specifically, as being constituted of the three formative element s of

17 Inter alia, Bra nsen, 1992; Bobel, 2018; Kissling, 1996; Newton, 2012; Shipma n Gunson, 2010; Ja ckson &

Fa lma gne, 2013; de Wa a l Ma lefyt & McCa be, 2016; Ma mo & Fosket, 2009; La hiri-Dutt, 2015; Zivi, 2020; Oina s, 1998; Kissling, 2013.

20 stigmatization, medicalization and commercialization (see chapter 2). The aim of analysis in this thesis is accordingly not the discovery of discursive features through empirical observations, as this was done through the proposition of the theoretical framework, but rather lies in the investigation of how the already established elements formative of this discourse are related to by empirical entities in their menstrual agenda. Therefore, the data in this thesis are examined through the means of qualitative content analysis, as introduced before, since this method serves the research aims better than discourse analysis.

3.2 Research Design

3.2.1 Qualitative ResearchIn the context of the scholarly controversy around qualitative research designs, (Kohlbacher, 2006:1-2), it seems necessary to elaborate briefly on the choice in this thesis for a qualitative research design. In addition to DCA’s utility regarding the tools for a theory-guided analytic approach, the qualitative design was chosen for its distinct advantages over quantitative content analysis method. For instance, it enables the provision of a more in-depth account of an understanding of findings through the tool of interpretation, thus addressing frequent content analysis neglect in this respect (Boréus, 2017b:45; Kohlbacher, 2006:37-38; Schreier, 2014:173; Bengtsson, 2016:10). Moreover, “the qualitative paradigm [negates] the existence of objectively true knowledge and [proposes] an interpretative approach to social knowledge which recognizes that ‘meaning emerges through interaction’” (Rubin & Rubin, in Kohlbacher, 2006:45), which brings the research design in line with the poststructuralist, discourse-focused theoretical framework provided before.

3.2.2 Case Study Design

This introduces another research strategy feature of this thesis, the case study design. In this study, what is meant by case study is the focus on the UN human rights agenda on menstruation as a case and the “unit of analysis” (Kohlbacher, 2006:19; Gerring, 2007a:1). Despite its value for the addressing of the research gap in approaching the UN human rights engagement with the topic through theoretical means, the case was chosen to be of relevance as exemplifying the character of the global movement for change in this context, and due to the agenda-setting power one may attribute to its global role in shaping the understanding of social norms in the area of gender equality. The design of this case analysis can hence be considered to belong to the camp of “crucial-case” single-case studies (Gerring, 2007b). In combination with content analysis tools, the case study design thus reflects the interest of this thesis in generating a

21 theoretical understanding of the ways in which dominant menstrual discourse can be, and is, challenged.

3.3 Methodological Limitations

To provide a valid methodological choice and arrive at reliable analytical results, some limitations of the method and research design choices need to be stated. The main weaknesses of DCA are potential bias deriving from the theoretical direction of the analysis and entailing “possible blindness” to the non-theoretical contextuality of findings (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005:1293). This must be recognized to be a methodological limitation that cannot be avoided considering the research aim to provide exactly a theoretical account. However, this weakness was partly addressed in the proposition of a two-step analytical process: After presenting the strictly theory-directed findings of the DCA in part one (chapter 4.1), part two will provide an understanding of these results in line with the overall methodological guidelines on content analysis (chapter 4.2) (Bengtsson, 2016:9-10; Mayring, 2000:14; Kohlbacher, 2006:22-31; Schreier, 2014:177). Thereby, practical implications beyond the theory will be proposed, which will not only strengthen the utility of the theoretical understanding, but also constitute the starting point for future more contextual human rights scholarship in the area. This two-part design furthermore aims at alleviating the shortcomings of solely descriptive research designs, as it provides not only the inventory taking of data on the case in question, but also has an understanding-generating function beyond manifest descriptions through the theoretical assessment of the findings in the second analytical part.

Another methodological weakness, the choice of a qualitative research design and the resulting difficulty to generalize the results, can be met with the assertion by Luker, who states that on a “voyage of discovery”, generalizability criteria are responded not through random sampling, but in terms of their logical implications and their theoretical consistency (Luker, 2008:43-46), which was taken into consideration throughout the operationalization process and the findings assessment (see 3.4&4.2).

3.4 Data Collection and Coding

3.4.1 Sampling of MaterialBased on the methodological framework, this section will provide an understanding of the sampling decisions made in the collection of the analytical data.

22 The chosen empirical material for the DCA is, without exception, constituted through textual sources produced by UN human rights related entities, in accordance with the assumption that “when [social phenomena] are studied, texts are crucial artefacts” (Boréus & Bergström, 2017a:1). In line with the qualitative research design and the relevance sampling method proposed by Krippendorff, the focus of sampling was lying not in the gathering of large amounts of quantitative data or the systematic random sampling, but in the collection of a small sample of particularly relevant material directly relating to the research interest (Krippendorff, 2004:119). Thus, conforming with the research aim to generate an account of contemporary UN menstrual agenda, the sample arrived at for analysis is comprised of 12 textual sources produced over an inductively established time frame of 8 years, 2011-2019, with the majority of sources having been published towards the end of this period. Main sampling requirement for these sources was the explicit mentioning of menstruation, as the goal of the analysis is the inquiry into the way in which menstruation is related to by the data-producing entities. The structure of the UN institution as made up of a network of different agencies posed a second requirement, namely the sampling of data from a range of different UN human rights related

entities in order to generate an understanding of the overall menstrual agenda within the

institution. The final sources thus are produced by various UN entities, from the UNHRC as the most authoritative agency in the setting of the UN human rights agenda, over UNSRs as experts in certain areas of this agenda, and CEDAW and UN Women as UN actors concerned specifically with the gender equality agenda, which seems important as menstruation was introduced in this thesis as an inherently female topic. This was added by supporting documents produced by entities like UNFPA, UNICEF, CESCR and UNESCO, which all published material relating to menstruation and thus added accounts to understand the overall UN menstrual agenda. Likewise, the genres of textual material sampled vary among the 12 sources, from official reports (A/HRC/18/33/Add.2; A/HRC/33/49), general comments (E/C.12/GC/22) recommendations (CEDAW/C/GC/36), and resolutions (A/HRC/RES/27/7; A/HRC/RES/39/8), to infographics (UN Women, 2019), guidelines (UNICEF, 2019), news publications (OHCHR, 2019; UNFPA, 2018; UNFPA, 2019) and policy booklets (UNESCO, 2014). This reflects the range of strategies applied by the entities in their menstrual agenda, from authoritative calls on states to change their behaviour in resolutions, to more information generation focus through e.g. infographics. Moreover, half of the sampled documents approach the theme of menstruation explicitly, by dedicating the whole text to the menstrual agenda18,

while the other half touches upon menstruation only in some paragraphs and include it into

23 other rights agendas19. These variations can be considered to valuably show the fact that the

contemporary agenda is increasingly integrated into the overall UN human rights agenda in many ways, and to enable the presentation of a cross-agency UN preoccupation with the theme. Recognizing the fact that the variety of data-producing entities, and that the diversity of different text genres may pose some interpretative validity issues (Boréus & Bergström, 2017b:46-47), the validity of the sampled texts is given through the aim of providing an overall

understanding of the UN agenda in relation to the theoretical framework.

3.4.2 Operationalization and Coding Frame

To systematically approach the sampled material, the conceptualization of the dominant menstrual discourse provided through the theoretical framework was operationalized in terms of DCA by the development of a suitable coding frame20.

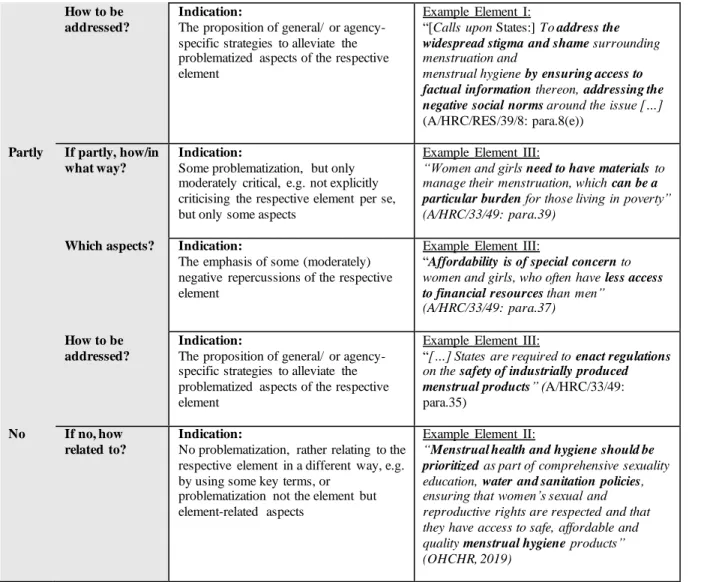

Accordingly, based on the identification of the three elements of stigmatization, medicalization, and commercialization as formative of dominant menstrual discourse (2.2), these three elements constitute the basic categories of analysis in approaching the data. Their operationalization and the development of analytical indicators of a relation to either of them was done both inductively, through the reading of the textual material and assigning them to the categories through interpreting their belonging to one of the elements, as well as deductively, through the already established scholarly findings on manifestations and effects of the respective elements (Boréus & Bergström, 2917b:24-28; Mayring, 2000:13; Kohlbacher, 2006:60-65). The chart below constitutes the operationalization of each of the three analytical elements, established to generate an analytical, empirically-based understanding of the UN human rights menstruation-related agenda in connection with the theoretical assumption of a necessity to address the three formative elements of menstrual discourse in order to alleviate its detrimental effects. The analytical points of interests were accordingly, whether the sampled textual material relates to each respective element (code a), and if it problematizes it (code b). By coding in these terms, a detailed account of how UN human rights entities approach menstruation in their contemporary agenda, and how they relate to each formative element of dominant menstrual discourse, can be generated in order to identify if they can be argued to act in line with the theoretical assumption on a holistic approach addressing each of these elements. This will not only exemplify the utilization of the comprehensive theoretical framework proposed, but also

19 A/HRC/18/33/Add.2; E/C.12/GC/22; A/HRC/33/49; CEDAW/C/GC/36; A/HRC/RES/27/7;

A/HRC/RES/39/8.