The Peacekeepers’ Publicity

A quantitative content analysis of Swedish newspapers’

coverage of the Swedish Armed Forces in Mali.

Natalie Jansson

Peace and Conflict Studies Bachelor thesis

15 credits Spring 2020

Supervisor: Kristian Steiner

2

Abstract

The aim of this study was to get a deeper understanding of the Swedish newspapers’ coverage of the armed forces’ participation in the missions EUTM and MINUSMA in Mali during the years of 2013-2019. To concretize the aim, I formulated five research questions regarding the context, focus, sources, origin and scope of the articles. The method chosen for the study was a quantitative content analysis, which was supported by the theoretical concepts of agenda setting and framing. The data included 117 articles from four of the largest Swedish newspapers; Aftonbladet, Dagens Nyheter, Expressen and Svenska Dagbladet. The result of the analysis stated that most of the articles were published in the event of an attack and focused on injuries or casualties. These articles were often written by journalists based in Sweden, or by a news agency. Very few articles were written by a correspondent on site in Mali, but the ones that did were descriptive of the mission and included the voices of several military personnel and given a lot of space in the newspapers.

Keywords: Försvarsmakten, MINUSMA, EUTM, peacekeeping, war and media, war correspondence

3

Table of contents

1. Introduction 5

1.1 Research problem 5

1.2 Aim and research questions 5

1.3 Disposition 6

2. Background 7

2.1 The conflicted Mali 7

2.2 Establishing the EUTM 7

2.3 The Swedish contribution to MINUSMA 8

3. Previous research 9

3.1 Public perception of the military 9

3.2 Access to site 10 3.3 Challenges of MINUSMA 12 4. Theory 14 4.1 Agenda setting 14 4.2 Framing 15 5. Method 18 5.1 Selection of data 18 5.1.1 Units of sampling 18

5.1.2 Units of data collection 19

5.2 Analysis of data 20 5.2.1 Method description 20 5.2.2 Variables 21 5.3 Method discussion 23 6. Analysis 25 6.1 General 25 6.2 Context 26 6.3 Focus 29 6.4 Voices 35 6.5 Byline 37 6.6 Scope 42 7. Conclusions 46 8. References 48 8.1 Literature 48 8.2 Other 49 Appendix 51 I. Article ID-list 51

4

III. Code scheme 53

IV. Code book 54

V. Coding form 1 56

VI. Coding form 2 58

5

1. Introduction

As of 2013, the Swedish Armed Forces (SAF) are deployed within the mandates of two separate missions in Mali, given the conflicts that ravages in the desert state. This is a quantitative content analysis on the Swedish newspapers’ reporting of these missions and the SAF’s participation in them. This first introductory chapter will present the research problem initiating this study, as well as its aim and research questions. It also contains a presentation of the disposition for the rest of this text.

1.1 Research problem

When the decision was made that the Swedish Armed Forces would descend its long term commitment to the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) in Afghanistan during 2014, Hans Rosén (2013) wrote an article in which politicians as well as military representatives expressed concern that the lack of a large international mission would reflect negatively on the recruiting of new soldiers to the organization, but also on the public perception of its work. According to the SAF (Försvarsmakten, 2020a) over 7000 Swedish soldiers were deployed in Afghanistan during the 13 years of the military commitment to ISAF, and at the time of the decision to dismantle ISAF the Swedish contribution to Mali were not expected to be as extensive as it later turned out to be. As will be described further in the chapter presenting previous research (chapter 3), there are several studies reflecting on the public perception and trust in institutions like the armed forces, and also on the media as a messenger and a middle hand between the public, the politicians and the institutions. Therefore, I am interested in analyzing how the international work of the SAF is portrayed and presented to the public in the Swedish newspapers.

1.2 Aim and research questions

The aim of this study is to get a deeper understanding of the Swedish newspapers’ coverage of the Swedish Armed Forces’ missions in Mali, by conducting a quantitative content analysis of news articles in Aftonbladet, Dagens Nyheter, Expressen and Svenska Dagbladet during the years of 2013-2019. To help achieve this aim I have constructed five research questions:

6 - In what contexts are the SAF’s missions in Mali mentioned in the Swedish

newspapers?

- What is the main focus of the articles? - Who is represented in the articles? - What origin do the articles have?

- How much space is given to the articles?

The foundations of these question will be discussed and motivated in the theoretical chapter (chapter 4).

1.3 Disposition

Following this introductory chapter will be a presentation of the background to the conflict in Mali and the two missions that the SAF are committed to (chapter 2), followed by a brief recognition of previous research (chapter 3) that is relevant to the subject of this study. It focuses on the view of public perception, journalists’ access to sites in war, and challenges the military faces while working in Mali. The theoretical chapter (chapter 4) centralizes around the concepts of framing and agenda setting in the media, to further understand the surroundings of the news articles and their content. The methodological chapter (chapter 5) gives a thorough introduction to the selected data and a description of the quantitative content analysis as a tool, followed by a discussion of its strengths and weaknesses. The result of the analysis will be presented in chapter 6, followed by a conclusive discussion in chapter 7.

7

2. Background

This chapter contains a brief presentation of the conflict in Mali and the establishment of the two missions which the SAF participates in, EUTM and MINUSMA.

2.1 The conflicted Mali

Mali is the seventh largest country in Africa, home to the Sahara Desert in the north and approximately 19 million people spread across the country. According to Lotta Themnér (2016) Mali, with its past as a French colony, gained its independence in 1960 leading up to the governing as a one-party state 1960-68 and a military dictatorship 1968-91. There are several separate ethnic groups living in different parts of Mali with a long complex history of neglection and dissatisfaction, all of which cannot be presented here. However, today’s conflict evolved as a cry for independence for Azawad, which is the local name for the northern parts of Mali. Northern Mali has historically been financially and politically neglected, partly because of its non-fruitful land and partly because of the habitation of the Tuaregs, an ethnic group that constitutes about 10% of the population (Ibid.).

Many Tuaregs emigrated to Libya during the leadership of Muammar Gaddafi and were trained militarily there until his fall in 2011. They returned home, formed the group MNLA and gave the Malian government an ultimatum – recognize the independence of Azawad or the group would commence a military offensive, which they did early in 2012 (Ibid.). MNLA was, however, not the only party to the conflict. They had a brief alliance with a group called Ansar Dine and managed to gain control of almost two thirds of the country. Ansar Dine eventually allied with two other Muslim groups, AQIM and MUJAO, to establish an Islamic state ruled by sharia laws which opposed an independent Azawad governed by Tuaregs. When the Islamic groups initiated an offensive towards strategic cities in southern Mali the government cried for help from France, who agreed and commenced its Operation Serval in January 2013 (Ibid.).

2.2 Establishing the EUTM

According to the SAF’s own description of the mission (Försvarsmakten, 2020b), the European Union established the EUTM (European Union Training Mission) in Mali by a

8 request from the Malian government in the first quarter of 2013. It is a long-term educational mission, where about 75 instructors from 24 states guide and support Mali’s military leadership and train Mali’s armed forces in weapons, combat techniques, medical care and human rights (Ibid.). No deployed personnel engaged in this assignment participates in any operational missions. The Swedish contribution is limited to 15 people who are engaged in the Infantry Training Team and the CSS Training Team, based 60 km northeast of Bamako – in Koulikoro (Ibid).

2.3 The Swedish contribution to MINUSMA

As described by the SAF (Försvarsmakten, 2020c), the UN Security Council adopted resolution 2100 under chapter VII of the UN Charter in April 2013, to establish a stabilizing mission in Mali authorized to take all necessary measures to prevent threats and the return of armed groups to northern Mali. The West African support mission AFISMA was integrated into the UN Mission in July the same year (Ibid.). The UN Mission, called MINUSMA (United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali), is supposed to encourage dialogue and release tension between groups, protect civilians and stabilize communities, prevent asymmetrical attacks against civilians and UN-personnel, as well as promote and protect human rights (Ibid). The mission has remained the same over the years, but as of 2016 part of the mission is also to promote and support the peace agreement that was signed during that time.

Swedish staff officers have been present in Mali since the spring of 2013, but a larger unit of Swedish soldiers arrived at Camp Nobel outside of Timbuktu in December 2014. Sweden’s most prominent contribution to MINUSMA consists of an ISR Task Force, short for Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance, with the main task of gathering intelligence (Ibid.). From November 2017 to May 2018, Sweden also contributed with air transportation in form of a C-130 Hercules aircraft. During the time of this study (spring 2020), the SAF (Försvarsmakten, 2020d) have published information about an alteration in the Swedish contribution to the mission in Mali. Camp Nobel in Timbuktu has been replaced by Camp Estelle in Gao, where the SAF now contributes with an infantry that is to perform security operations in support of MINUSMA (Ibid).

9

3. Previous research

This chapter present research done in areas relating to this study, and whose conclusions serves as important aspects surrounding media coverage of the armed forces, which will be helpful for me in my analysis and discussion.

3.1 Public perception of the military

In a study of the Swedish public view of the armed forces, military service, and NATO, Joakim Berndtsson, Ulf Bjereld and Karl Ydén (2017, 598) argue that the public perception of the armed forces are depending on legitimacy and trust, which derives from a consensus view of the armed forces between the public, the political elite and the military. They focus particularly on the view of political decisions regarding military and security issues, methods of recruiting, and military style (i.e. the symbols and rituals that distinguish militaries from civilians) – claiming that changes within these areas need to be embedded in the civil-military relationship (Ibid, 599).

During 2013, when it became clear that the Swedish troops were to dismantle from Afghanistan and Kosovo, the political agenda of the Swedish participation in international missions were up for debate (Rosén, 2013). The lack of international missions was considered, both by politicians and the SAF, as a risk to the recruiting of new soldiers, as international missions and an opportunity to actively work to achieve peace and security around the world are attractive for many people joining the military. It was also considered a waste of resources for Sweden not to participate internationally, but also regarded as something that would negatively impact the public’s trust in the armed forces if the organization did not achieve something, or gain experience and knowledge that would help the Swedish defense in the future, while still being so financially draining.

Berndtsson et al (2017, 603-604) researched the public trust in federal institutions over the years until 2016, and the confidence balance for the SAF was only positive once during the previous 15 years, namely in 2015 when the balance was +3. In 2016, 42% of the respondents claimed that they had “neither great nor small confidence” in the armed forces, something that Berndtsson et al considered an indicator for lack of interest or lack

10 of knowledge among the respondents. This reluctance to take a stand was significantly more often used for questions concerning the military than for example the police or the healthcare system (Ibid, 603).

Other research, by Sören Holmberg and Lennart Weibull (2014, 99), suggests that the public’s trust in social institutions not only depends on the circumstances surrounding the people themselves and the institutions, but also the characteristics of the mediums channeling the information between the people and the institutions. Holmberg and Weibull conducted a study on the matter and came to the conclusion that people’s trust in social institutions covaries systematically with the attention that a specific institution is given in the media (Ibid, 114). Their hypothesis was based on the supposition that the trust in an institution would be lower if the institution was given a lot of attention in the media, thus made on the assumption that a lot of media coverage is generally negative. The study was done on a small scale and did not specifically explore whether the institution was portrayed in a positive or negative manner, but Holmberg and Weibull remained confident that the frequency of media coverage influences the level of trust for the institution in question.

What responsibility the media have in informing the public will be further evaluated in the theory chapter, but the issues of legitimacy and trust that these studies present are interesting and valuable to the analysis of the media content surrounding the work of the armed forces. Through these studies, it seems like the international work of the military needs to be promoted and recognized by the media, if they are going to earn the trust of the Swedish people.

3.2 Access to site

In their study, Stephen Hess and Marvin Kalb (2003) have conducted several interviews and panel discussions with journalists and government officials in the US, to identify the struggles of war correspondence in the sense of maintaining the freedom of the press but at the same time protect information in the interest of the state. They quote one highly experienced Washington bureau chief, who accordingly said that the Pentagon and the press are “two great institutions … that have totally contradictory objectives and purposes” (Hess & Kalb, 2003, 85). The discussion they presented on the matter maintain

11 this polarized attitude towards war correspondence. The representatives of the press argued that for the long-term success of a mission, the military must have the support of the people, which they can only get through the appeal and coverage by the media (Ibid, 93). But instead of using the media to their advantage, the military shuts them out and claims operational security. An official public representative responded that this operational security is absolutely crucial, especially in a world where information spreads in an instant, as they do not want to “paint a picture for the bad guys”, neither of what has been done or what will happen (Ibid, 94). So even though her assignment was to keep the public engaged and supportive, she claimed that it was a constant balance of giving information without gambling with peoples’ lives (Ibid, 94).

In a Swedish study of war journalism, Karin Fogelberg (2004) turned the attention to Swedish journalists’ access to conflicted areas, with the most recent one included in the study being the war in Afghanistan. Contrary to Hess and Kalb’s research, Fogelberg does not recognize the problem of availability for journalists in regard to getting access to the military, but in regard to who is governing the area in question. In a zone controlled by enemies, access might be incredible dangerous or not possible at all, while journalists might be welcome in a friendly governed zone but only under very specific circumstances (Ibid, 237-239). Both of these scenarios restrain the journalistic work in their own ways.

One of the examples given by Fogelberg included the accessibility to interpreters, and who provided them. For a foreign correspondent who does not speak the local language, an interpreter is a necessity. The interpreter does not only translate, but often provides local and cultural knowledge as well as useful contacts, given that the relationship between the journalist and the interpreter is good and built on mutual trust. What Fogelberg (2004, 238) argued was that in Afghanistan, one reporter was approved by the Afghan government to work in a specific area and was appointed an interpreter by the government, whom he had not chosen himself and did not have a successful relationship with, which resulted in the interpreter modifying the translations to fit his own views. This is of course damaging to the journalistic work and may result in misleading news reports.

The relevance of distinguishing these issues in relation to my study, is that it is very likely that they affect whether or not a news organization finds it valuable enough to have a

12 reporter on location. The stories getting through to the media are of a different character depending on them being based on firsthand stories by locals, or on a news telegram of the latest events. However, the cooperation of the SAF and the judgement of risk for a Swedish journalist to be in Mali must also be considered.

3.3 Challenges of MINUSMA

Prior to the Swedish Armed Forces’ arrival in Mali, Magdalena Tham Lindell and Claes Nilsson (2014, 10-11) conducted a study based on interviews with people who had already served in MINUSMA, with the aim of identifying challenges and prerequisites to the mission, and what conditions the Swedish troops would have to meet. They recognized five major challenges accounted for below.

Logistics

Mali is a very large country and covers the surface of Spain and France combined. The northern regions are wrapped in desert and lack prominent infrastructure. The temperatures are extreme and there was a large shortage of water. The mission lacked capabilities to evacuate injured personnel, and heavily relied on the French Operation Serval for that service (Ibid, 31-32).

Generation of force

The deficiency of resources and competence, at least at that early stage of the mission, was recognized as a huge problem. It was seen as a result of the mission’s incapability to obtain resources as well as the long bureaucratic processes within the UN. The African troops from AFISMA was given an initial period of support with education and resources when they were first integrated into MINUSMA, but overall the UN had to accept troops that did not meet the standards of an UN operation (Ibid, 33).

Management

Many of the interviewees experienced that the management of MINUSMA was very obscure and inefficient, and that there was no operational plan of how the mandate should be achieved (Ibid, 34).

13 Operative ability

The study showed that the mission did not reflect the robust demeanor approved in its mandate, but that this could be a result of the challenges mentioned above. Experiencing more and more attacks, the troops needed be more offensive and actively look for and analyze the threat. However, UN’s incapability to provide for the troops and the insecurities of attaining medical evacuation were seen as examples to why many troops solely focused on daily survival and nothing beyond that (Ibid, 36-37).

Security situation

The mission has been known as one of the deadliest peacekeeping missions in the history of the UN. It was heavily targeted and experienced considerable losses during its first 16 months. The attacks were categorized as mainly conducted by rockets, grenades, road mines and suicide attacks (Ibid, 37). Tham Lindell and Nilsson (2014, 39) argue that some fatal outcomes could have been prevented by sufficient equipment and protection.

The arguments regarding the challenges of the mission presented in this study are relevant to my research for at least two reasons: challenges in conducting the mission are likely to influence what information the SAF present to the public but are also likely to affect what the media publishes about it. Tham Lindell and Nilsson do present critical arguments towards the UN and the management of the mission, which is very interesting since Sweden’s longtime engagement in Afghanistan was with NATO, and the experiences were likely very different. However, the participation in MINUSMA came at a time when Sweden was heavily lobbying for a spot in the UN Security Council, so even though they might have been critical to the management of MINUSMA as well, it is very unlikely that this was expressed publicly.

14

4. Theory

In this chapter I will present how the media concepts agenda setting and framing have guided me in my research and recognize how these theoretical concepts have led me to the research questions of this study.

4.1 Agenda setting

The concept of agenda setting stems from a responsibility of the media to inform the public with valuable and truthful messages, and a power of evaluating what information is the most precious at what time. Marina Ghersetti (2012, 210) argues that people’s own experiences together with the information that is given to them influences the perception that the public have of issues and events around them, which in turn affects not only individuals but the world itself. This is similar to the arguments made by Holmgren and Weibull in chapter 3.1 and revolves around the relationship between the media’s agenda and the public’s agenda. Further on, Maxwell E. McCombs and Donald L. Shaw (1972, 176-7) argued that one should always recognize that people’s interest and attention to information may vary, meaning that educated and (in their case politically) interested people are more likely to actively seek information. However, Jesper Strömbäck (2014, 101) means that the general procedure still seems to be that people depend on the media for information as the reality is far too complex to examine on your own, which in turn allows the media to gain ownership of issues and the extent of the attention given to them and by that setting the agenda.

The agenda setting does not implicate how the news are presented, which is the function of framing as recognized in the section below. Agenda setting represents the first steps in the news selection and determines what news even makes it to the agenda. Bernard Cohen (1963, 13) explained that: the press “may not be successful much of the time in telling people what to think, but it is stunningly successful in telling its readers what to think about.” (italics not mine) – which emphasizes the importance of the relationship between the media’s agenda and the public’s. Ghersetti (2012, 208-9) also calls attention to the fact that the media’s agenda may be influenced by commercial considerations due to financial reasons, thus risk including news that are entertaining, sensational, dramatic and easier to sell in favor of news of a heavier kind but with higher relevance.

15 Adam Shehata (2012, 324) claims that researchers have further developed the agenda setting theory during the years with an enhanced focus on priming which recognizes the opinion-making aspects, meaning how the media content affect people’s behaviors, opinions, and judgements. Shanto Iyengar and Donald R. Kinder (1987, 63) emphasized the importance of acknowledging the power the media have also in distinguishing what questions the public find important when it comes to the assessment of representatives of government or other large organizations. In other words, the assessment of public representatives is based on the questions that the public are familiar with, delivered through the agenda of the media (Shehata, 2012, 325). The focal point of this study is not how the public respond to the media content. However, it is still worth acknowledging the power the Swedish newspapers may have in shaping the public opinion of the armed forces and the leaders of its organization just by bringing the subject to the agenda.

In practice, the concept of agenda setting determines what events are significant and newsworthy enough to make it to the newspaper’s agenda. This has influenced my research question regarding the context of an article. The context reflects on the event that makes the content of the article important enough to be published. Given the specific subject of this study, in what context the SAF are brought to the agenda of the newspapers could determine the public perception of the work they are doing, which in turn could influence the confidence the people have in the Swedish defense and military capability. The agenda setting also determines how much space the article gets in relation to other news, thereof my research question regarding the scope of the article. This is particularly interesting in regard to the paper editions of a newspaper, as everything on a physical page has to stand in relation to the other articles on the same spread.

4.2 Framing

The concept of framing concerns how a message is presented and what information it is surrounded by, so to guide the reader to a certain interpretation of the message. Robert M. Entman (1993, 52) explained that “to frame is to select some aspects of a perceived reality and make them more salient in a communicating text, in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, casual interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation for the item described” (italics not mine). In other words,

16 framing a message means including or excluding aspects of the reality in a text so to make the certain message more prominent (Ibid, 54). Jesper Falkheimer (2012, 164) further claims that framing may concern aspects like the definition of a problem, the role and responsibilities of specific actors, values, or consequences.

The framing of a message is, consciously or not, made throughout several steps of the communication process: by the source, the communicator, the information delivered, by the receiver and its cultural surroundings (Entman, 1993, 52; Falkheimer, 2012, 163). The communicator frames the message based on its own belief system, again consciously or not, when it decides what to say; the text is depending on frames by the inclusion of certain keywords, stock phrases or stereotypes that arrange for confined bundles of facts or opinions; the receiver’s conclusion may or may not be influenced by the frames in the text and the objective of the communicator, but is likely to have already been affected by the discourse in its cultural surroundings (Entman, 1993, 52-53). Dhavan V. Shah, Douglas M. McLeod, Melissa R. Gotleib and Nam-Jin Lee (2009, 91) argue that the creator of a message may also need to adjust the frame so that it responds well with the previous knowledge and values of the message’s recipient, as this enhances the chance to get a more prominent effect of it. Therefore, framing is a process depending on the relationships between leaders, individual journalists, norms of the profession and ideological differences, as well as other aspects (Shah et al, 2009, 86).

The arguments made for the concept of framing above have guided me to several of my research questions for this study. First of all, the question regarding the origin of the articles. It is a conscious decision to incorporate newspapers of different ideological standings in the study (more about this in chapter 5), not for the purpose of strictly comparing them, but to eventually present a result that is of a general view and not tied to the influences of a single ideology. Even though news articles are typically neutral, all the minor aspects that Entman and Falkheimer have presented above might influence the writer of an article to unconsciously lean in a certain direction. However, I will not analyze journalists at an individual level in this study, nor their ideological standings, but I do intend to investigate the characteristics of different methods of reporting by analyzing articles written by a foreign correspondent, by a journalist based in Sweden, and articles first published by a news agency or another newspaper. The experiences and surroundings of the different methods could impact the way the writer frames the message in an article.

17 Second, the question regarding who gets a say in the articles. A source is able to speak out of its own experience and version of the truth, and a source that represents an organization has the opportunity to frame a message favorably to the own organization. This will also influence the message of a story. Last, but not least, the question regarding the focus of the articles. This is the heart of framing, as it concerns the actual message of the story and what it wants to tell the reader. Together with the context, the focus is the variable in the study that actually presents the content of the articles.

18

5. Method

In this chapter I will discuss different methodological considerations in regard to the selection of data as well as the analysis. A full list of the data collected and more comprehensive material regarding the analysis can be found in appendix I-VII.

5.1 Selection of data

This section is separated in two parts: the first one regards the selection of newspapers and the second one focuses more on the process of gathering the data included in the analysis.

5.1.1 Units of sampling

To be able to answer the research questions of this study I need data that provides a generalizable result, requiring a collection of data from newspapers that represents the Swedish newspaper market fairly well. This representation is characterized by the reach of the papers, their political leanings, and their capacity as either a morning paper or a tabloid. The political leanings of the papers are not something that will be deeply evaluated in the study, but that maintain an important aspect of the sampling as they represent different groups of the Swedish news consumers. According to Nationalencyklopedin1 (2020) a tabloid (or evening paper) is characterized by a more relaxed structure than a morning paper with news that are more sensational and easier to sell. Tabloids are often sold by single copies, whilst morning papers have a tendency of being subscribed to. I want to include papers that reach both these audiences.

According to Kantar Sifo’s2 (2020) latest report on the scope of the Swedish newspapers and magazines, Dagens Nyheter and Svenska Dagbladet were the largest national morning newspapers in Sweden during 2019, reaching 520 000 and 302 000 readers respectively. The two largest national evening newspapers were Aftonbladet and Expressen, with 457 000 and 426 000 readers respectively (Ibid.). These numbers reflect on printed editions only.

1 Nationalencyklopedin (NE) is a Swedish encyclopedia available in print and online.

19 Dagens Nyheter (DN) is an independent liberal newspaper founded in 1864 that is part of the Bonnier Group, one of the largest media organizations in northern Europe (Dagens Nyheter, 2008). Expressen is also part of the Bonnier Group and has a liberal standing, but is a tabloid, contrary to DN’s orientation as a morning paper (Expressen, 2017). Expressen is nationwide, founded in 1944, and heads two editions with a more local coverage: Kvällsposten focusing on the south of Sweden, and GT focusing on the west (Ibid). Included in this study is solely Expressen as the nationwide paper. Svenska Dagbladet (SvD) was founded in 1884 and is an independent moderate morning paper with the Norwegian media group Schibsted as the largest shareholder of 99,4% (Svenska Dagbladet, 2020). Schibsted are also the largest shareholder of the tabloid Aftonbladet, with 91% of the stocks, with the Swedish Trade Union Confederation (LO) owning the remaining 9% (Aftonbladet, 2016). LO has the right to appoint the political editor in chief of Aftonbladet, which have had an independent social democratic approach since the 1960’s (Ibid). The paper was founded in 1830.

Further on, the papers will always be presented in alphabetical order (which also happens to recognize their political leaning from left to right), but in this initial presentation I believed it would be valuable to categorize them according to their media group belonging, given that Bonnier and Schibsted own the majority of one morning paper and one tabloid respectively. Even though it was a coincidence on my end that the newspapers included in the study belonged to these groups, it should be considered a fair representation that two of the largest media groups in the Swedish newspaper industry are equally included in this study. The decision to limit the study to the printed editions of the newspapers is based on the transformative nature of articles published on the web. The digital sites are constantly evolving, and articles can be edited several times as an event progresses and moved up and down the site. The printed articles maintain in the form they are initially published and are therefore more reliable units to analyze. The printed editions of the newspapers are all available in the Retriever database which according to their own presentation (Retriever, 2020) is the most extensive media archive in Scandinavia with approximately 100 million searchable articles provided in full-length.

5.1.2 Units of data collection

The Retriever database presents several opportunities to limit the search within the newspapers selected. One of the most challenging aspects in the gathering of data in this

20 study is how to search the database and get a sample that is representing the subject in a generalizable manner. I have done my data collection through four steps, in four sessions. I used the extended search tool and entered my search words in the box for words that the article must contain (more about the words I used below). I limited the dates to 2013-01-01 until 22013-01-019-12-31 and selected the respective newspapers. When the search was done, I manually removed argumentative texts like chronicles and debate articles, and articles where the mission in Mali are solely mentioned in fact boxes. The maintaining articles should be news articles reflecting on the security situation in Mali, the mission itself, the political discussion regarding whether or not to deploy troops in Mali, and similar aspects that can relate to both the missions and Mali.

My initial thought was to solely use the search words “Försvarsmakten” (the Swedish name for the SAF) and “Mali” to get the articles that relates to SAF’s participation in Mali. However, this would risk excluding articles with a less formal attitude in which the SAF are not called by its full name. In Sweden the SAF often goes by the name “försvaret”, which roughly translates into “the defense”. I also wanted to recognize articles in which the content focuses more on the missions rather than the SAF. To widen my data collection, I therefore decided to conduct several searches. The four steps above will therefore be implemented in four sessions. Initially with the search words “Försvarsmakten” and “Mali”, secondly with the words “försvaret” and “Mali”, thirdly with the words “MINUSMA” and “Mali”, and lastly with the words “EUTM” and “Mali”. In the event that an article appears in the result of several searches, it is only included once. The process resulted in a total of 117 articles. A full disclosure of which article was collected through which search can be found in the Article ID-list in appendix I.

5.2 Analysis of data

This section will describe the quantitative content analysis, the tool for this study, and present the variables used as well as how they came about.

5.2.1 Method description

The decision to conduct a quantitative content analysis is based on its non-intrusive character, which Jim Macnamara (2005, 6) claims authorizes research on a large amount of data over an extended period of time in a rather time efficient manner. Kimberly Neuendorf (2017, 21) means that as with any quantitative analysis, the content analysis

21 is based on a numerical process, with the ambition to count key categories and measure the amounts of other variables. The phenomenon under scrutiny in a quantitative content analysis are often of a qualitative nature, but the purpose of the study is to produce a numerical summary of a chosen message set, rather than to present a thorough characterization of it (Ibid, 21-22). This means that the variables in the analysis are rather simple in comparison to a more thorough, qualitative content analysis, as the ambition in this study is to get a general view on a large amount of data.

Pamela J. Shoemaker and Stephen D. Reese (1996, 31-32) argue that a content analysis may categorize messages in the media content, but to truly understand the meaning of the messages, the researcher must also reckon other phenomena like the medium itself, the sources and the context. Neuendorf (2017, 43-44) argues that approaching the analysis as a descriptive one must entail an analysis of solely the variables measured within the content analysis. This does not prevail that the relationship between variables cannot be discussed and accounted for, as long as the variables are measured within the study. I intend to approach the analysis descriptively with basic, straightforward research questions and an expositive result. However, I recognize the arguments made by Shoemaker and Reese, which serves well with the intention of my study, and I will therefore include variables in relation to the circumstances of an article like the source and the medium.

5.2.2 Variables

The aim of this study is to get a deeper understanding of the Swedish newspapers’ coverage of the SAF’s missions in Mali and through the previous research of others, as well as the concepts of agenda setting and framing, I have constructed a coding scheme with six variables intended to answer the research questions of the study. These categories are closely related to each of the research questions respectively, and whose theoretical connection have been outlined in chapter 4. However, the first variable solely concerns the newspapers and the belonging of the articles and does not relate to any research question. The decision to make it a variable is only for the convenience of having everything in codes at the later stages of summarizing the results.

The codes responding to the variables derive partly from the perspectives of the previous research presented in chapter 3, and partly from the data itself. In a study with a deductive

22 approach all variables and their measurement should be established prior to the observation of the data. However, Neuendorf (102-103) argues that a “researcher may need to immerse himself or herself in the world of the message pool and conduct a qualitative scrutiny of a representative subset of the content to be examined”. In other words, Neuendorf suggests that if the researcher is familiar with the data and let the variables emerge from the messages of it, it might be beneficial for the study as it limits the risk of failing to identify key variables (Ibid, 103). Even though an inductive approach, where variables are chosen as they are being studied, is dismissed by Neuendorf as something that “violates the guidelines of scientific endeavor” (Ibid, 11), she claims that the process of a content analysis naturally combines an inductive and deductive approach as a lot of exploratory work is necessary before a final coding scheme can be finalized (Ibid, 12). In clarification, the variables in this study derive partly from the data so to make them as specific to the subject as possible, but they are all finalized

prior to the coding. The invalidity of a completely inductive approach, where issues

might be added throughout the study, are therefore limited.

The codes responding to the variables are depending on two ground rules: they need to be exhaustive and mutually exclusive. This means that there must always be a code available that suits the unit analyzed, but that there can only be one code that is appropriate (Neuendorf, 2002, 118-119). For this reason, I have developed a codebook with instructions on how to interpret the codes, which can be found in appendix IV. Below is a summarized presentation of the variables and the codes from the codebook.

Article ID: The article’s ID-number from the Article ID list. Year: The year the article was published.

Coder ID: The coder’s ID-number from the Coder ID list. Date: The date when the article was coded, yyyy-mm-dd.

23 2. Context: The circumstance on which the article is based – attack, accident, peace

negotiations, threat level, visit, working conditions, deploying, dismantling or portrait. Also includes other and unable to determine.

3. Focus: What the article centers around – enemy, health, injuries, casualties, missing

person, equipment, new troops, policies or mission. Also includes other and unable to determine.

4. Voices: Who gets a “say” in the article – military, politician, expert or civilian. This

category contains the alternatives not included and several people with different professions given the possibility that the article does not voice any specific person, or the possibility that several people are heard. Also includes the alternatives other and unable to determine.

5. Byline: Who has written the article/where it comes from, e.g. if it’s based on firsthand

experience or reports. Contains the alternatives correspondent, home desk or news agency/other newspaper, as well as other and unable to determine.

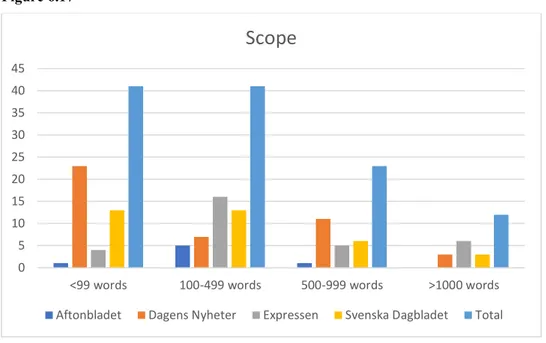

6. Scope: The size of the article based on the number of words included. Categorized in

<99 words, 100-499 words, 500-999 words and >1000 words.

All the units of data collection will be coded one by one according to these variables, where the appropriate code will be noted in the coding form. Article ID-list, coding scheme, codebook and coding form are all available in appendix I-VII.

5.3 Method discussion

This section is devoted to a general discussion in regard to the method and its implementation. Some questions have already been accounted for, but this will serve as a collective debate for possible concerns in relation to this particular study.

The quantitative content analysis as a method can arguably be too shallow and not explorative enough when messages are not analyzed in their entireties, but rather picked a part so to discover the segments of interest for the researcher. For this study I do not

24 consider this argument to be a weakness, as my area of interest regard the surroundings of an article, more than its specific content and statements. The shallowness of the method is what makes it possible to analyze such a large amount of data and get a generalizable result, so in this case it is a strength. This approach is well suited given the basic nature of my research questions and the aim of my study.

A possible weakness of this work is my role as a single researcher and thereby single coder, as this might threat the reliability of the study. To limit this risk, I have developed a code book with extensive instruction on how to interpret the variables prior to the coding. I have also coded all the data twice at two separate occasions and highlighted any questionable results. In the event that an article is coded differently on the two occasions, it is coded a third time. These articles and the difficulty in coding them will be presented and discussed in the analysis.

As mentioned previously in this chapter, I have executed several searches to collect the material included in the analysis. The data collection is also an area that might be affected by me being a single researcher as it is partly my own interpretation of the material that decides whether or not it should be included. I have tried to maintain honest and open with the choices I have made throughout the process, and the boundaries that have guided me through it. Should there be any questionable judgements regarding the selection of data, I still feel confident that it would not be extensive enough to jeopardize the result of the analysis, given the large number of articles already included.

25

6. Analysis

This chapter contains a presentation of the analysis and its results. The first section displays a general overview of the data included in the analysis and its spread over time. The following sections are dedicated to each research questions respectively.

6.1 General

As mentioned previously, the data collection’s different steps resulted in a total of 117 articles from four different newspapers: Aftonbladet, Dagens Nyheter, Expressen and Svenska Dagbladet.

Figure 6.1

Figure 6.1 presents the distribution of articles per newspaper from 2013 to 2019. The collection resulted in a significant low number of seven articles from Aftonbladet, which naturally will influence all of the numbers related to that newspaper and have to be kept in mind throughout the analysis. The spread among the remaining three newspaper are more even, with 44 articles from Dagens Nyheter, 31 articles from Expressen, and 35 articles from Svenska Dagbladet. These numbers do express a larger interest in the missions among the morning newspapers, but since the number of articles from Expressen are still so similar to the morning papers, I will not make that conclusion. One should also remember that these numbers might have been different depending on the search words used in the selection. It cannot be ruled out that Aftonbladet might have published articles

7

44

31 35

Articles per newspaper

26 about the missions in other words, thus might have a number of articles in their archive relating to the subject that did not appear in my search. At the same time, another search might have impacted the outcome for the other newspapers as well. However, further on in the analysis the number of articles from each respective newspaper will matter less as the aim is to get a general view.

Figure 6.2

The timespan of the study covers the years of 2013 to 2019, as both EUTM and MINUSMA were established in the spring of 2013 and 2019 is the last year available in its entirety. My desire was to include the missions from the very start and as long as possible. Figure 6.2 presents the number of articles published per year during this time span. The largest number of articles were published during 2015, which might be a reaction to the more extensive deployment of Swedish troops that occurred in December 2014.

6.2 Context

With the context of an article I refer to the circumstances that makes the article appear on the agenda. A considerable majority of the articles were published in relation to an attack, and as visible in figure 6.3, three of the newspapers published almost equal numbers of articles with this context, implicating that they might have reported on the same events. Articles relating to deployment or decisions to deploy makes the second largest group, closely followed by the articles circumstanced by the threat level.

0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45 50 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019

Articles per year

27

Figure 6.3

The two variables for deploying and threat level have been slightly difficult to separate in some cases, where the article has presented the security situation that the troops are being deployed into, and article 2-0023 as well as 2-0074 had to be coded a third time for this reason. I have looked at the preamble for guidance in these cases. In article 2-007 the title states that: “33 people are part of the Hercules-force”5 which emphasizes that the article is concerning the deployment of new troops. However, the preamble states that:

“There is a certain threat level towards the Swedish task force that are going to Mali. This assessment is made by Klas Grankvist, deputy squadron leader for the mission, and the one who is planning the Swedish operation.”6

This emphasizes that the circumstance of the article is a concern for the security situation that the troops are being sent into. In article 2-002, on the other hand, the title and the preamble are actually implicating the same thing, namely that France wants help to fight terrorists in Mali. The preamble reads as follows:

3 Dagens Nyheter, Frankrike vill ha hjälp av EU, 2013-01-16. 4 Dagens Nyheter, 33 personer ingår i Hercules-styrkan, 2013-06-06. 5 ”33 personer ingår i Hercules-styrkan”

6 ”Det finns en viss hotbild mot den svenska insatsstyrka som ska åka till Mali. Den bedömningen gör Klas Grankvist, ställföreträdande divisionschef för insatsen, och den som ska planera den svenska operationen.” 0 10 20 30 40 50 60

Context

28

“The war in Mali is a magnifying glass of the shortcomings in the French defense. There is now an increasing annoyance towards the EU-neighbors – France does not want to be at war alone.”7

This suggests that France wants other EU-countries to back them in the war. The difficulty with this article is that it describes issues with the French warfare, and the security situation that they are facing in Mali, which implicates a level of threat. However, the article is published in the circumstance of a political discussion in France regarding the war and their expectance of other European leaders to participate. Therefore, the article is surrounded by a political discussion on who should, or should not, deploy troops in Mali, which is why I decided for the code of deploying. Deploying into a warzone should likely come with an assessment of the threat level and these articles serves as examples that the numbers in figure 6.3 regarding the variables for threat level and deploying might be related to some extent, but that different newspapers have different approaches.

A significant number of articles from Dagens Nyheter are related to working conditions, which is a result of a thorough investigation they did on the food situation for the Swedish troops in Mali and that was presented in a series of articles, as well as notices on the frontpages. I will analyze these further in the next section (chapter 6.3).

7 ”Kriget i Mali är ett förstorings-glas på bristerna i det franska försvaret. Nu ökar irritationen mot EU-grannarna – Frankrike vill inte kriga ensamt.”

29

Figure 6.4

As previously mentioned, a clear majority of the articles were published in the event of an attack. The evaluation amongst the newspapers to publish articles in relation to attacks seems logical for a couple of reasons. First of all, the dramatic character of an attack always makes for a good story. Second, the informational aspect of newspapers and their responsibility towards the public somewhat requires them to inform the public of events of this character as they are a threat to the security of Swedish citizens. Looking at figure 6.4, we can see that the number of articles published in the context of an attack increased significantly during the first three years of Swedish deployments in Mali. Since these numbers only reflect on articles within my search, thus are related to the SAF and the missions in Mali and not on attacks in general, the statistics needs to be considered accordingly. However, two of my searches were related only to MINUSMA and EUTM, and not to the SAF as such, implicating that in case there were a lot of reports on attacks where other soldiers, from e.g. MINUSMA, were involved they would have appeared in that search.

6.3 Focus

Contrary to the previous section on context, the codes relating to focus regards the actual content of an article and its message to the reader. Figure 6.5 presents the focus of all articles included in the study. The four largest groups consist of articles focusing on injuries, casualties, policies and the mission. A further disclosure of these categories will follow. 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019

Context – attacks

30

Figure 6.5

Relating to the previous discovery that most articles were written in circumstance of an attack, figure 6.6 centers around the focus of those articles. The majority of them concerns injuries and casualties, something that supports the argument in the previous section that the newspapers have some sort of obligation towards the public to report on security events and threats towards Swedish citizens abroad, and their status in the aftermath of an attack. I would also consider this to be related to the institutional trust that Holmberg and Weibull (2014) argued in chapter 3.1, given the media’s role as a messenger between the SAF in Mali and the public. In many cases the source in the articles are representatives from the SAF, something that I will get back to later in this chapter, but that enhances the role of the media as merely a messenger in some cases.

0 5 10 15 20 25 30

Focus

31

Figure 6.6

Article 2-0338 serves as a good example of how an article written in the context of an attack and which focuses on reporting injuries or casualties have typically looked like and presented below is the first part of that article:

“The UN-camp in Timbuktu in Mali, where the Swedish UN-soldiers have their base, was subjected to an armed attack on Thursday, according to the Swedish Armed Forces. The camp serves as a base for UN-troops from several countries. No Swedes, but at least four soldiers from “another nation” were injured.”9

The context of this article is clearly the attack on the base. The focus is telling the reader that people were injured, but also that none of them were from Sweden. Had this not been a Swedish newspaper, this text would probably not include the comment on the Swedish troops as the status of a non-injured Swede would not be newsworthy in many other countries. This article is framed so to interest and be relevant to the Swedish readers. Regardless that no Swedish soldiers were harmed in this attack, the article still gives the impression that the SAF are deployed in a dangerous area. This study is not meant to speculate around the perception that the readers get by these kind of articles, so whether these reports serves as just reports, if they imply that the SAF are competent enough not

8Dagens Nyheter, FN-soldater attackerade vid svenskbas i Mali, 2017-06-02.

9 ”FN:s läger i Timbuktu i Mali, där de svenska FN-soldaterna har sin bas, utsattes för ett väpnat angrepp på torsdagen, enligt Försvarsmakten. Lägret är bas för flera länders FN-trupper. Inga svenskar men minst fyra soldater från ”en annan nation” skadades.”

0 5 10 15 20 25 30

Attack – Focus

32 to get injured in attacks or if they are just lucky, are questions left unanswered. This short article did include a specific message from the source (the SAF) and included information of interest for the newspaper’s readers, while still being open for interpretation. This is a good example of how framing works well even in very short texts.

Discovered in this analysis was an intertwined relationship between the two codes for new troops and policies in the aspect of deployment. The codes have been used in relation to other contexts as well so their function may differentiate more in other aspects but considering only deployment, they represent pretty much the same articles, while just framed differently. Thus, the coding came to depend on the character of the article: if it was more political it was recognized as policies and if it was more a statement that new troops had arrived at camp it was recognized as new troops.

Figure 6.7

Figure 6.7 presents the category responding to deployment, and the focus of those articles. It contains almost solely articles regarding new troops and policies, although a majority regard policy. The decision to include this code was to distinguish all the articles considering the political process of the armed forces from the others, as politics control important aspects of the foundation of Sweden’s military engagements but does not concern the actual military work. Returning to the argument made by Berndtsson et al (2017) in chapter 3.1, the trust in the armed forces depends on a consensus view between the public, the military and the political elite, making it reasonable that the political

0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14

Deployment – Focus

33 accountability is recognized in these articles of deployment. Article 1-00210 is one of the articles focusing on policies regarding deployment. The preamble for the articles reads as follows:

“Sweden sends no JAS aircrafts to the fight against IS. The government says no and offers air transportation, equipment and staff officers instead. The opposition is strongly critical.

– We are not prepared to take our responsibility. We pass on what is expensive, difficult and dangerous to other European nations, says Allan Widman (L). “11

Without further research on the triangular relationship between the public, politicians and the military, this article is a fair example of how politicians make one third of the players in the game of legitimacy and trust for the armed forces. The military does not just do things without a political decision. What is also visible in this data is once again the role of the media to function as a messenger between the players.

There are other examples of difficulties in the coding relating to the similarities in the codes, and to which the codebook has been a necessity to be able to maintain a clarity in how the process has progressed, especially considering my status as the only coder. I have had to consider the framing of the articles as they might have contained information crossing several aspects of interest, and then reflected on what the most prominent messages of the article are. Article 2-03912 was coded a third time as a result of differences in the two initial sessions, where it was first marked as focusing on new troops and the second time on mission. After further consideration I landed on new troops, as the article was not descriptive enough of the actual mission in Mali but focused more on the preparation for it. Another article, 2-02813, was initially coded as a report on (no) injuries but was by the second and third coding altered to enemy. At the first glance, the status of injuries seemed like the most important aspect of the article. However, in the later sessions what seemed most prominent was the death of an enemy, making that the final

10 Aftonbladet, ”Rejält militärt bidrag”, 2015-12-17.

11 ”Sverige skickar inga Jas-plan i kampen mot IS. Regeringen säger nej och erbjuder istället flygtransporter, materiel och stabsofficerare. Oppositionen är starkt kritisk.

– Vi är inte beredda att ta vårt ansvar. Vi överlåter det som är kostsamt, svårt och farligt på andra nationer i Europa, säger Allan Widman (L).”

12 Dagens Nyheter, Här gör sig svenska soldater redo för FN:s farligaste fredsinsats, 2018-05-06. 13 Dagens Nyheter, Försvaret dementerar att FN-soldater dödat man, 2016-10-12.

34 coding. Considering this, I regard that reliability and the validity of my research was strengthened by the decision to code the data twice, and by the instructions in the code book to minimize the risk of misleading interpretations.

As with the category of working conditions in relation to context, the pile for health in figure 6.5 is also related to the series of articles published by Dagens Nyheter considering the food situation for the Swedish troops in Mali, which explains that this category almost solely responds to that paper. It was Dagens Nyheter’s own investigative series of articles (see article 2-012 to 2-019 in appendix I), regarding a subject that the public could possibly relate to and opinionate around, without being that invested in the work of the military. Without speculating about whether or not it did relate well with the public, or whether or not they had an opinion about it, I still would like to reflect on the role of the media in opinion-making brought up in chapter 4.1. Shehata (2012) argued that the assessment of public representatives is based on questions that the public are familiar with which are presented and made relatable through the media, which is interesting in consideration to this subject that Dagens Nyheter focused on so particularly. In short, the news regarded a lack of proportionate rations of food for the soldiers deployed in Mali, resulting in them losing weight and going to bed hungry. This created a cycle of blaming, where the word bounced between politicians, the leadership of the SAF and the UN, in other words almost all the players in the game of legitimacy and trust as previously discussed. Hypothetically, it might have opened up for the public to have opinions about political and military leadership, thanks to an issue that did not even involve military work, but which was relatable. Furthermore, by bringing this subject to the agenda in a way that the public could understand, Dagens Nyheter might also have managed to bring attention to the SAF’s participation in Mali and the prerequisites of the deployment just by framing the subject with contemplation. However, a further analysis of this subject goes beyond the limitation of this particular study.

I will discuss the articles describing the mission in a later part of this chapter, but it is also worth acknowledging that only five articles in total focused on the enemy, as visible in figure 6.5. I cannot analyze content that does not exist but considering what the SAF are deployed to do in Mali and all the articles that are published in relation to an attack, it would seem reasonable to have recognized the enemy and its goals.

35

6.4 Voices

The category called voices concerns who is given a chance to speak firsthand of the subject that the article circles around. To clarify, this does not include quotes from other platforms, like statements on Twitter, or statements made to other newspapers that are quoted a second time.

Figure 6.8

The numbers presented in figure 6.8 are not that surprising given the circumstances and the results in the previous categories. It seems rather natural to seek an answer from someone within the military regarding the subject of this study, given that the study only includes articles regarding the SAF and the military missions. A considerable number of articles do not include a statement from anyone, which is concerning as no one confirms or challenges the facts of the story. One of the aspects of framing as described in chapter 4.2, was the framing made by the source. To not include a statement from someone else, means that the article is solely based on the interpretation of an event made by the writer. The circumstances of including another source or not will be further evaluated in relation to the articles’ origins and scopes later in this chapter.

Previously in this chapter I discussed the role of politicians in regard to the legitimacy of the armed forces. The general numbers in figure 6.8 states that not many articles included the voice of a politician and as presented in figure 6.9 below a majority of them regarded policies. This implicates that politicians do not comment on the work of the SAF, unless

0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45 50

Military Politician Expert Civilian Several people Not included Other Unable to determine

Voices

36 it regards the political process. However, a few articles with other subjects have included a politician, and considering the very low numbers of articles in this category in total it is very difficult to make a definitive conclusion.

Figure 6.9

Another consideration regarding the voices in the articles are the invisible ones that are hidden amongst “several people with different professions”, as this does not implicate what professions the participants have. For example, worth noting in the results in figure 6.8 are the lack of statements solely from experts. However, the result in this case might be a little bit misleading as experts have been heard in several articles throughout the study, but in relation to other people which have put them under the pile of several people with different professions. The same goes for politicians, who in several cases have been included in relation to an expert. Even though it might be seen as a flaw for this study that the codes are not more specific in these cases, it can also be considered a strength for the articles and the work of the newspapers to have included people from different professions as this have likely improved the credibility of the stories.

Returning to the high number of articles including someone from the military, figure 6.10 presents the number of articles in which military representatives have made statements responding to attacks. In these cases, the military representatives are probably among the few knowing the details of the event and are able to give a proper response. So as long as a journalist do not have access to firsthand witnesses, the military is probably the most

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

Politician – Focus

37 dependable source. Reflecting on the institutional trust I would reckon that it is important for the SAF to comment on these subjects, to prevent rumors or misleading information from making the news. Furthermore, it gives them a chance to influence the framing of the story. Once again, a high number of articles have not included a statement from anyone, which will be further evaluated in the section below.

Figure 6.10

6.5 Byline

The results presented in this section concerns who has written the articles, based on the articles’ bylines. A correspondent reflects on a journalist that is located in a foreign country, home desk responds to all the articles written by one of the newspaper’s journalists in Sweden, and news agency/other newspaper reflects on all the articles that are not written by one of the newspapers’ own journalists but has a byline from a news agency or another newspaper.

0 5 10 15 20 25

Military Politician Expert Civilian Several people Not included Other Unable to determine

Attack – Voices

38

Figure 6.11

As presented in figure 6.11, the majority of the articles are written by journalists in Sweden or published as statements from other newspapers or news agencies. However, worth noting is that Expressen has a significantly low number of articles from news agencies or other papers, but also higher number of articles by the home desk than the other papers. This could suggest that Expressen actually wrote their articles about events which the other newspapers did not spend their resources on. All the newspapers except for Aftonbladet have at some point published articles by a correspondent, either in Mali or from somewhere else related to the missions. I have been unable to determine the authors of a few articles as they have been located on the frontpage where no bylines are included. Figure 6.12-6.14 presents the three groups of bylines respectively, and the focus of the articles within these groups.

0 10 20 30 40 50 60

Correspondent Home desk News

agency/other newspaper

Other Unable to

determine

Byline

39

Figure 6.12

Reflecting on the arguments made in chapter 3.2 on journalists’ access to sites in conflicted areas, figure 6.12 is very interesting as it concerns what correspondents have prioritized to report in circumstances where they have actually gained access. First of all, it needs to be acknowledged that the total number of articles included in this category is very low. Not knowing the underlying causes for that, one can only speculate around the subject. To have a correspondent cover the SAF in Mali would be the most efficient and trustworthy way to portray their work and to inform the public of the mission, its progressions and challenges.

Three of the newspapers have had correspondents writing with a focus on the missions, but during a seven-year period this has resulted in only eight articles. The articles that have been published are diverse and concerns different aspects of the mission and the troops deployed in Mali. Thus, it seems like the SAF have cooperated when it comes to granting access to journalists, something that Hess and Kalb (2003) considered one of the greater problems in chapter 3.2. Assuming that this is true, it was most likely evaluations within the news organizations that determined whether or not a correspondent would be sent to Mali or not. Given the dangerous prospects of working in Mali, sending a correspondent to location must be worth the risk and the costs. For the newspapers, it might not have been valuable enough to further cover the mission in Mali and the armed forces there since, as mentioned previously, the mission remained the same during the time period included in this study, besides the peace agreement that was supposed to be

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9