Solidarity with migrants in and around Grenoble

Volunteer commitment: from reflection to action

Elsa Leone

International Migration and Ethnic Relations Two-year Master’s program

Master thesis 30 credits Spring 2020: IM639L-GP766 Supervisor: Brigitte Suter Word count: 21 968

Abstract

This thesis explores the drivers of the commitment of volunteers that support migrants. It aims at investigating the reasons that lead people to decide to get involved in solidarity action with migrants through the case study of Grenoble and the Isère department, in France. Through qualitative interviews with volunteers and coordinators from solidarity organizations in the geographical area, this ethnographically inspired research identifies factors participating to the birth of solidarity action. Beyond finding that there is never one reason for people to get involved, the study identifies internal and external drivers of the commitment and the mechanisms within which they operate. It concludes that a combination of internal and external factors resulted in the volunteers getting involved physically in helping migrants. Additionally, it contributed to the discussion on solidarity, including its political dimension, and generated findings about motives for volunteering that may benefit civil society actors supporting migrants.

Word count: 148

Table of contents

Acknowledgments ... 5

Prologue ... 6

1) Introduction ... 8

1.1 Motivation and aim of the study ... 8

1.2 Research questions ... 9

2) Background information ... 11

2.1 Migration policies and management in France ... 11

2.2 Grenoble, the Isère department and migration ... 12

2.3 The Covid-19 pandemic and lockdown ... 14

3) Previous research ... 17

3.1 Volunteering and motives for helping ... 17

3.2 Solidarity in France and Europe with migrants since 2015 ... 18

3.3 Solidarity during the Covid-19 crisis ... 19

3.4 Contribution of the thesis ... 20

4) Conceptual framework ... 21

4.1 Solidarity ... 21

4.2 The psycho-sociological approach ... 22

4.3 Disagreement, resistance and political solidarity ... 23

4.4 Humanitarianism and moral principles ... 25

5) Methodology ... 27

5.1 Ethnographically inspired research ... 27

5.1.1 Methods, sampling and access to the field ... 27

5.1.2 Validity and reliability ... 28

5.1.3 Delimitations ... 28

5.2 Material ... 28

5.2.1 Organizations ... 28

5.2.2 Interviewees and other interlocutors ... 29

5.3 Positionality ... 31

5.4 Ethical considerations ... 32

6) Analysis: the driving forces of the commitment ... 33

6.1 Internal drivers of the commitment: building a ‘fertile ground’ for solidarity action .... 33

6.1.1 Life trajectories and personal history, socialization ... 33

6.1.2 Religious convictions: beliefs and faith ... 35

6.1.4 Emotions and psychological elements ... 41

6.2 External drivers of the commitment: triggers ... 46

6.2.1 Leaders and sources of inspiration ... 46

6.2.2 Life trajectories ... 47

6.2.3 The networks ... 48

6.2.4 Media coverage of the distress of migrants ... 50

6.2.5 Impact of the Covid-19 pandemic and lockdown ... 51

6.3 Conclusion ... 53

7) Discussion: Beyond the question of why people help ... 55

7.1 The political dimension of commitment ... 55

7.1.1 De-politicization or re-politicization? ... 55

7.1.2 What makes our emotions political? ... 56

7.1.3 Humanitarianism versus political? ... 57

7.1.4 A political dimension influenced by the organization itself ... 58

7.2 Motivations in special times: what about the crisis effect? ... 59

8) Conclusion ... 62

References ... 64

Appendices ... 74

Appendix 1: Organizations ... 74

Appendix 2: Interlocutors ... 76

Appendix 3: Interview guide ... 79

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank my supervisor at Malmö University, Brigitte Suter, for her helpful advice and enlightened opinion during the academic journey that this thesis has been and which has helped me grow as a future researcher. I also want to express my appreciation for her support and understanding in the complicated circumstances in which I have conducted this work.

I would like to thank all the participants to this work who have accepted to give me some of their time and to talk to me about their experiences.

Thank you to my classmates and friends who helped me with advice but also study sessions and motivational support, we were all in this boat together and I am grateful that we helped each other all the way. A special thank you to Emma, Juliette and Armande for their help with comments and proofreading.

I am thankful for the love and attention of my close ones and friends who took care of me, helped me blow off some steam, changed my mind and gave me faith in myself.

Prologue

Feelings about inequalities and others’ distress and difficulties is something that I have always experienced, and the way we are all different in our relationship to these feelings has always intrigued me. I have been sensitive to issues of inequalities, racism and discrimination since forever, having been raised in a family that shares those concerns and later through my experiences abroad and my encounters with people – friends, teachers, mentors, scholars, activists – who made me deepen my understanding of and sensitivity to the fight against injustice. Like many others, during what is called the ‘migration crisis’ but that together with several researchers (Lendaro, Rodier, and Vertongen, 2019; Farrah and Muggah, 2018) I choose here to call a ‘welcoming crisis,’ or an ‘asylum crisis’ (Braud, Fischer and Gatelier, 2018), I was strongly hit emotionally and felt powerless when thinking about the challenges faced by the people who were trying to reach Europe in very difficult conditions. Then, I was already at the time studying political sciences and was writing my bachelor’s thesis on the Syrian war. This has also shaped my perception of the situation and made me even more outraged at the fact that some politicians and individuals had discourses of rejection towards those ‘waves of migrants’ coming to Europe. At that time, the city I was living in, Grenoble, was far from having those ‘waves’ of immigrants (Courrier International, 2020). It is only later on, when I started living abroad that the area started to see more migrants arriving, and especially people crossing the border between Italy and France, or at least this is not before 2017 that I started to hear about it. Then I learned that people on the French side of the border were helping asylum seekers with accommodation, navigating the system, and even rescuing those who got lost in the snow while crossing the Alps. When Cédric Herrou,1 a farmer got threatened with

offence charges for having hosted migrants in his farm next to the border, activists all over France were outraged and started voicing strong opposition against this new délit de solidarité [offence of solidarity], I took part in this, mostly on social media and in my social circle. I admired the people who committed to helping those who arrived exhausted in France looking for a better life, fleeing conflicts and life threats, or trying to reach their families. I think that my admiration was even reinforced by the fact that anti-immigration discourses and policies were flourishing at the time and that these people were risking a lot in getting involved. I also admired the people who

1 BBC.com (2017). French farmer Cedric Herrou fined for helping migrants. BBC, [online] Available at:

volunteered in Greece in the refugee camps, or in the North of France where migrants try to reach the UK, or those who got involved in rescue at sea in the Mediterranean.

The realization that while I was praising solidarity work, I did not personally engage in it became the starting point for this thesis. I looked at myself and at how I had convictions and was feeling strongly about this situation, wanting to get involved but for several reasons did not do it, and started wondering about the reasons that pushed those people to put the beliefs that I shared into action. At first, I had planned to go to Briançon, a town close to the Italian border, where more and more migrants started crossing in 2017 and where a strong solidarity movement was formed. In spring 2020, I was ready to go there and conduct fieldwork for a month with participant observation. This is when the Covid-19 pandemic hit Europe and France. My plans completely fell through and I had to change my topic, since an online or distant research was not possible. First, because of the strict lockdown that was put into place in France. Second, because the field itself was not “available” anymore, because most of the crossings stopped, and because the people involved in solidarity there do not communicate or coordinate so much via the internet or were not available. Switching the geographical focus to Grenoble then made sense, because of the numerous organizations supporting migrants that exist in the city, and the important number of migrants who live in and around the city. In doing so, I also did not realize that I would – maybe more poignantly because I was investigating ‘at home’ – come closer to an answer to my question. This thesis is about those who get engaged, and the conditions that led them to do so. Conditions that I do not gather entirely, hence my non-commitment; for now…

1) Introduction

1.1 Motivation and aim of the study

In 2014, the increase in arrivals of people seeking asylum in the Schengen area was quickly described as a “refugee crisis” or a “migration crisis” (Del Biaggio and Rey, 2016; Musée national de l'histoire de l'immigration, n.d.). In France, as stated by the government itself, there was not a rise in asylum applications until late 2015 (Gouvernement.fr, 2020a) and in 2018, France was the third country to have accepted the greatest number of asylum application in Europe after Germany and Italy, but in way smaller proportions – 41 400 accepted cases against 139 600 for Germany – (Toute l'Europe.eu, 2020). Quickly following the first arrivals in Europe, a polarization emerged between pro- and anti-migration discourses, countries and citizens (Speciale, 2010). While some countries like Germany or Sweden were at first more willing to host migrants, the failure to install a real solidarity between the European countries to share the responsibility for taking in migrants eventually discouraged the welcoming effort and the borders were closed again (Magnan, 2016). In 2016, the EU started to make deals with transit countries like Turkey and Libya asking them to help preventing people from going at sea in exchange of funding (European Commission, 2019) and migration policies quickly became more restrictive (Stock, 2017).

NGOs and activists were very critical of those policies and words like “welcome” and “solidarity” were at the center of the pro-migration circles (Della Porta, 2018). One decisive element was the rising occurrence and visibility of shipwrecks of migrant vessels in the Mediterranean and the deaths of migrants at sea (Braud, Fischer and Gatelier, 2018). The media coverage of those tragedies indeed stirred up emotions among Europeans, and played an important role in the surge in volunteering with migrants across Europe (Lendaro, Rodier, and Vertongen, 2019). However, volunteering to help asylum seekers, refugees and migrants is not something new; it has been the object of attention in media and research for a long time (Böhm, Theelen, Rusch and Van Lange, 2018; Herrmann, 2020; Wilson, 2000; Vertongen, 2018). More broadly, the question of “why people help” has interested scholars, particularly in social psychology, for many years (Batson 1995; Oceja, and Salgado, 2012; Segal, 2018).

This thesis is interested in the specificities of a place and a time. The political context in Europe since the beginning of the ‘refugee crisis’ seems all but favorable to immigration; migration policies are becoming more and more restrictive (Stock, 2017), there has been a multiplication of hate crimes and xenophobic discourses against migrants (Lomeva, Lozanova, Gabova and

Voynova, 2017) together with a criminalization of solidarity (Fekete, 2018). But even with all of these elements, thousands of citizens continue to get involved in solidarity work, NGOs, grassroot groups and individual action to help all kind of migrants – refugees, asylum seekers, unaccompanied minors, migrant workers, victims of trafficking – with integration, administrative procedures, basic needs and accommodation, all across Europe (Della Porta, 2018). It may indeed seem puzzling to see the growing engagement and resilience of people who get involved in solidarity despite the many obstacles and difficulties faced by migrants themselves but also defenders of migrants’ rights. In Grenoble, one of these obstacles is for example the unfavorable political context, with an increasing in anti-migration local political actors, lack of resources for organizations, and restrictive migration policies at the national level (Braud, 2018).

At the time of writing, another major element entered the picture; the Covid-19 pandemic that spread globally, hitting Europe too and led most governments to put in place lockdowns and sometimes state of emergency to fight the spread of the virus when it became out of control during the spring of 2020 (The German Marshall Fund of the United States, 2020). This situation undeniably had consequences for migrants and those who help them (McAuliffe and Bauloz, 2020). This research aims therefore at investigating volunteer commitment with migrants through the case of solidarity action in Grenoble and the Isère department [local district].

The study will take into account the uniqueness of the time during which the research was conducted, that is to say, the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic in France in 2020.

1.2 Research questions

The main research question to this study is: Why do people decide to commit physically in helping migrants and other foreigners?

More closely:

- How can we understand the transition from caring about the situation of migrants to practicing solidarity?

I intentionally chose the physical commitment, which excludes online individual activism, donation, ally work, signing petitions… because I am interested in the people who give their time and who engage bodily in solidarity with migrants. This distinction allows me to understand the process that volunteers go through and to go beyond feeling solidarity. This does not mean that I disregard the types of activism that do not entail a physical commitment – in fact, it is extremely important and useful for social justice – but it is a necessary distinction to frame my topic.

In order to answer these questions, I conducted qualitative interviews in the framework of an ethnographic approach that allowed me to access in-depth information on the case. Mobilizing a multidisciplinary conceptual framework on solidarity and help in my analysis of the material, I provide an answer to these research questions. I also offer a discussion on transversal elements of the volunteer commitment.

2) Background information

2.1 Migration policies and management in France

In the French law, immigration is organized by the Code of Entry and Residence of Foreigner and the Right of Asylum (CESEDA) since 2005 and the migration policies are decided by the government and implemented by the Interior Ministry through the institutions under its tutelage (Vie-publique.fr, 2019). Migration policies have been a major focus of governments, with seventeen laws adopted between 1980 and 2018 on the matter. Martin, Orrenius and Hollifield (2014: 8) consider that they did not include any major changes, and talk about a “strong symbolic dimension” of migration policy, with electoral strategies playing an important role in this intense production of new laws. Corneloup and Jault-Seseke (2019) also mention the use of migration reform as a communication tool. I do not have the space and time to proceed to a detailed overview of the successive laws, that is why I will focus on the last one to date at the time of writing, the ‘Law of 10 September 2018 for a managed migration, an effective right to asylum and a successful integration of 10 September 2018’ [pour une immigration maîtrisée, un droit d'asile effectif et une intégration réussie] commonly called “Law asylum and immigration” or “Collomb Act” from the name of the Interior Minister. The law, presented by the government as an answer to the increased “migratory pressure” of migrants and asylum seekers coming to France and Europe (Ministère de l'Intérieur, 2018), has been criticized by NGOs and academia (Paumard, 2018). Even the Council of State has criticized the lack of rigor in the figures and studies used to justify it (Corneloup and Jault-Seseke, 2019). The main objectives and decision brought by this law concern the length of asylum procedures, the protection and security for beneficiaries of international protection and regular migrants, the reinforcement of the fight against irregular migration and finally on attracting highly skilled migrants. The law is criticized in many aspects, mostly for its effect on migrants’ rights. Those include the accentuation of measures linked to the suspicion of fraud – which was already a tendency in the migration policies before but that is reinforced in the law – or the extension of the duration of administrative detention for people waiting for deportation (ibid). Migration policies are very centralized and their management is implemented by the state and its representative. One exception is the situation of unaccompanied minor. The local district [département] is the one that determines if people applying for protection as unaccompanied minors are under 18 years old – the age of majority in France – and if they are isolated and therefore are entitled to protection from the child welfare services [Aide sociale à l’enfance, ASE] (ibid).

Municipalities have limited powers when it comes to decisions about migration, but they are the one on the front line when it comes to providing basic and social services to the migrants who arrive on their territory. Although in France, as reminded in a report on the competences and responsibilities of cities on migration, municipalities do in fact have the possibility to take initiatives, especially concerning accommodation, integration and anti-discrimination (Organisation pour une citoyenneté universelle, 2019). However, at the local level, decisions about who has the right to access accommodation facilities and social services are taken by the state, mostly through prefectures.

2.2 Grenoble, the Isère department and migration

Grenoble is a city of about 160 000 inhabitants situated in the Alps, in south-eastern France. It is the capital of the Isère département which is itself part of the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region (see Fig. 1).2 The city has a particularly vibrant civil society, with a wide network of organizations that

provide support to migrants. In 2016, the network Migrants in Isère [Migrants en Isère] was created, federating 18 associations and organized the ‘General Estates of migrations’ [États généraux des migrations3] which formulated a series of propositions about hospitality and

integration directed to the local representatives (Méténier, 2019). If the municipality is welcoming towards migrants and asylum seekers, it is not the case of the Isère department, which is often accused by NGOs of restricting migrants’ right, particularly migrant youth and unaccompanied minors (Le Cimade, 2017). It has been reminded several times of its obligation to protect minors by the Council of State and even convicted by the administrative court of Grenoble (Tribunal administratif de Grenoble, 2017; Escudié, 2019).

The municipality, led by a left-wing mayor from the Green party since 2014, for example created a platform to coordinate the support to migrants, and is also part of a network of French cities called “Welcoming cities and territories” (Unevillepourtous.fr, 2020). The Migrants’ Hub [Plateforme Migrants] is also an important tool put in place in 2015 by the municipality in coordination with civil society actors to gather offers of support like French classes, donations, accommodation and legal support (Braud, Fischer and Gatelier, 2018). However, the mayor has also been criticized in

2 As of 2020, France is divided in territorial collectivities into three levels, 18 Régions [regions], 101 Départements

[departments] and 34 970 Communes [municipalities] (Vie-publique.fr, 2019).

3 The name “Etats généraux” was given to this event in reference to the assembly of the people that presented their

the spring of 2020 for not having supported migrant young adults during the lockdown with accommodation and not allowing them to demonstrate after the lockdown was over, invoking sanitary reasons (Bourgon, 2020; Fourgeaud, 2020).

Données cartographiques © 2020 Google. Figure 1: the Isère department

In 2015, contrary to many places in Europe, the city did not face a massive arrival of asylum seekers, mostly because they were “not choosing France” (Lapperousaz, 2015). However, according to a report from the regional prefect, between 2016 and 2017 the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region has seen an increase of 35% of the number of asylum applications, with a 52% increase in Grenoble (Secrétaire général pour les affaires régionales Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes, 2018). Asylum seekers indeed constitute an important part of migrants who are helped and supported by the civil society in their application for protection but also accommodation, since the reception centers are overcrowded and they often have to wait several months before getting a spot in a center (Braud, 2018). As of 2019, there was an estimated lack of 1700 spots for accommodation of asylum seekers in the Grenoble area only (Ligue de l’enseignement de l’Isère, 2019).

In late 2019, early 2020, the support to migrants, asylum seekers, refugees and foreigners in general was at the heart of the preoccupations of many activists and civil society actors. In the neighboring

mountains and valleys too, many collectives and organizations were created, especially to provide accommodation for asylum seekers because of the lack of free spots in state accommodation facilities (Braud, Fischer and Gatelier, 2018). Fourteen collectives provide accommodation within families and citizens’ homes, connected with the NGO Welcome asylum seekers [Accueil Demandeurs d’Asile, ADA] that proceeds to the referrals of people in need of accommodation. Even more collectives of this type exist in Isère, including networks of accommodation in parishes and individuals hosting independently (Méténier, 2019).

2.3 The Covid-19 pandemic and lockdown

This research has been conducted during a very specific time: the spring of 2020, during which the global pandemic of Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) hit Europe. The outbreak reached France at the end of January 2020, and two months later a full national lockdown and the state of health emergency were declared on March 23, 2020 (Direction de l'information légale et administrative (Premier ministre), 2020). The Government later communicated the concrete measures entailed by the lockdown, that were quite strict: all shops that were not selling necessities had to close. It also meant that going out of home was forbidden except for the following reasons: buying necessities like food and medicine, going to work if working from home was not possible4, going to a medical

consultation, helping vulnerable people or childcare, exercising briefly around the home. In order to be able to control this, people had to carry identity papers and a signed sworn statement stipulating the reason(s) for leaving home, risking a fine in case of breaching one of those conditions. On May 11, 2020, the lockdown ended and restrictions were lifted progressively throughout the following months (Gouvernement.fr, 2020b).

Even before the full lockdown, NGOs were already warning about the very worrying situation of migrant populations regarding the pandemic (Forum Réfugiés, 2020; Cook, 2020). Once the lockdown was put into place, European countries took different measures regarding migrants and asylum seekers. In Portugal, the state decided to grant migrants who had an ongoing residency application the same rights as its residents (Del Barrio, 2020). However, in most European countries, migrants ended up in limbo, especially people in irregular situation that were – already before the outbreak of the pandemic – highly dependent on NGOs and charities’ help (ECRE,

4 This mostly included people working in the medical field as well as in food stores and pharmacies, but also tobacco

shops, garbage collectors, postal workers. When in this case, workers also had to carry a certificate from their employers (Ministère de l'Intérieur, 2020a).

2020). If solidarity with migrants was needed before, the threat of the global pandemic made it even more urgent. Yet, the situation made it also more complicated to implement it concretely – for example, rescue at sea had to stop (ibid).

In France, the validity of residence permits and asylum application certificates was extended for 180 days for those whose expiration date was between March 16, 2020 and May 15, 2020 (Ministère de l'Intérieur, 2020b). The registration of new applications for asylum was temporarily suspended, at the exception of registration of vulnerable people, while identifying those who had the intention to apply for asylum. However, on April 30, 2020, the Council of State ordered the Ministry of Interior to re-establish the registration of asylum seekers in the Paris area (Conseil d’Etat, 2020). The declaration of the state of emergency suspended time limits for a range of appeals (Delbos, 2020). When it comes to the accommodation of asylum seekers, it was mostly a situation of status quo, where spots in accommodation facilities were already limited.

For solidarity organizations, the consequences of the lockdown were important, as much as the pandemic itself. Partly because most of the help activities had to stop, but also, amongst other reasons, because many of their volunteers being retired people and part of at-risk groups, had to stop helping. As a consequence, calls to volunteers were made through the mainstream and social media, and platforms were created to allow people to register themselves as available for volunteering (Delpierre, 2020).5 In these circumstances, charity organizations had to adapt to

continue providing help to vulnerable populations, including migrants.In the Isère department and its chief city Grenoble, while some charities were still allowed to exercise their activities, most of the support they used to provide had to stop, like legal aid (La Cimade, 2020) or language activities. At the same time, some of them were reinforced like food distributions (Solidarités Grenoble, 2020) or accommodation of migrants in families (Diaconat Protestant de Grenoble, 2020). Providing accommodation for migrants that were living in the streets was indeed an urgent challenge (Chesnais, 2020). Most of the organizations tried in some ways to continue exercising solidarity with migrants and vulnerable people, be it through physical actions or virtual help (Beyrie, 2020). Advocacy also increased with NGOs writing open letters to the President or to local authorities asking them to take stronger measures to protect asylum seekers and migrants (Carretero, 2020).

5 From these platforms, some examples are at the national level Jeveuxaider.gouv.fr together with the “civic reserve”

[Réserve civique] Covid-19, created by the government but also initiatives from the civil society like Covid-entraide France and commentaider.fr. At the local level, many cities and departments had their own platforms and networks, like “Grenoble voisins, voisines.”

The end of the lockdown was also problematic because it put many migrants in highly difficult situation, especially asylum seekers and young adults. In Isère, organizations supporting migrants voiced criticism about the slowness to re-open the administration in charge of processing applications for residence permit. It especially contrasted with the emergency faced by migrants whose time limits for applying started to run again – from May 24, 2020 for appealing against rejection of asylum and June 24, 2020 for applying for asylum, both having a time limit after which they were not valid anymore (GISTI, 2020).

3) Previous research

In this section, I present the state of the research on the topic at heart in this thesis: volunteering and help to others in the framework of solidarity. After a review of the research on volunteering (3.1) and solidarity action with migrants (3.2), I turn to the specific aspects of solidarity during the Covid-19 ‘crisis’ of 2020 (3.4). Finally, this section allows me to position myself in the field (3.4).

3.1 Volunteering and motives for helping

This thesis is interested in people involved in solidarity action with migrants. However, helping has been studied for a long time, by several disciplines, and with diverse methods and conclusions. From theses disciplines, one can cite psychology, social psychology, political sciences, sociology but also philosophy.

Havard Duclos and Nicours (2005a) studied volunteering and investigated the reasons for people to get involved in solidarity organizations. They argued that altruism and willingness to commit in helping others is not something that is naturally part of our personality, but that it is the product of one’s personal history and of the charity organization itself. In a second research (Havard Duclos and Nicours, 2005b), they identified four motives to get involved: (1) be useful, (2) be in line with one’s own story, (3) feel in harmony with one’s previous engagements, and finally (4) social and material retributions. Brodiez (2009) investigated the evolution of the profiles and motives of activists from Emmaüs.6 She found that religious beliefs continued being part of the motives over

time, even with the decrease of the role of religion in the organization and in the society. Importantly, primary (childhood) and secondary (adulthood) socializations played a great role in the factors of involvement, as well as values and personal networks. Indeed, socialization is often found to be crucial for one’s commitment in helping. Religious socialization was frequently brought up in the research on volunteering (Havard Duclos and Nicours, 2005; D’Halluin, 2010; Czerny, 2019; Gerbier-Aublanc, 2018b; Brodiez, 2009). The values promoted by monotheisms – in the cases evoked, Christianism – are often used by citizens to justify their actions. Of course, other kinds of socializations are also important; Gerbier-Aublanc mentions “political, intellectual, artistic or religious socialization” (2018a: 92).

6 Emmaüs is a solidarity organization that was founded in 1954 in France by a Catholic priest, l’Abbé Pierre. Its

particularity is that it is constituted of “communities.” In 1971, it developed into an international network, still with the goal to fight poverty, exclusion and homelessness (Emmaus-france.org, 2020).

3.2 Solidarity in France and Europe with migrants since 2015

Although it did not start in 2015, the phenomenon of people helping migrants by getting involved in actions of solidarity is topical and has known a peak in Europe (Feischmidt, Pries and Cantat, 2018). This movement happened in traditional associations,7 but also via grassroots groups that

self-organized through social media to help migrants with food and clothes distribution, language classes, accommodation, social integration, legal aid… (Barone, 2018; Herrmann, 2020; Bourgois and Lièvre, 2019; Mouzon, 2017; Giliberti, 2018; Masson Diez, 2018; Vertongen, 2018; Bernàt, Kertész and Tóth, 2016).

Masson Diez (2018) studied several forms of organized solidarity with migrants in France in the aftermath of summer 2015, observing the spontaneous drive to help people sleeping in the streets ‘down their block.’ Street camps in Paris played a role in the “moral shock” that led many citizens to help (Masson Diez, 2018: 178) in a will to “go from emotion to action” after seeing people in need (ibid: 170). For her, these encounters made it impossible for people to deny the reality of the situation and to ‘bear’ the sight of these people directly down one’s building without doing anything. According to Masson Diez (2018), the role of the personal network and acquaintances was also an important element for people to get involved. Knowing someone who is involved can facilitate the decision, as it is also found by Ruiz (2017) in her study of volunteers helping migrants in Swiss Romandie.

For those who did not directly witness the migrants’ difficult situation, media coverage has been identified as a strong trigger for solidarity movements with migrants in Europe after 2015. The picture of the dead body stranded on a Turkish beach of Alan Kurdi, a Syrian-Kurdish boy, particularly was seen as a such by many (Masson Diez, 2018; Fekete, 2018; Braud, Fischer and Gatelier, 2018; Gerbier-Aublanc, 2018a, 2018b).

Stock (2017) studied integration of newcomers in Germany and volunteer effort after 2015. Reviewing the literature, she highlighted the opposition between two views on the surge of volunteers to help asylum seekers. First, some academics said that it was a welcoming culture and a new political movement against Europe’s handling of migration, defending foreigners’ claims to rights. Others identified the movement as a product of the states’ will to outsource their social

7 “Association” is the most common name given to NGOs in French. It is a form of organisation that can be created

by anyone (it does not have to be professional) and whose status and activities are regulated by a law adopted in 1901 (Associations.gouv.fr, 2005).

services and sees refugees in need of help as passive receivers. In this view, the main drivers of the volunteering effort were the perceived vulnerability of the migrants and self-individual fulfilment. In their study of accommodation of asylum seekers in Grenoble, Braud, Fischer and Gatelier (2018) argued that the state, confronted to a lack of accommodation spots, saw the opportunity to use the networks and associations that emerged spontaneously at the local level for accommodating asylum seekers and refugees. It provided funding and pushed for hosting families to help asylum seekers with language learning, or finding a job... However, it used this in a utilitarian perspective and did not try to generalize it. For the authors, the state was afraid to lose control over a pro-migration movement that would show an idealized picture of what integration could be, which would be in contradiction with the restrictive migration policies it was putting into place. Snyder and Omoto (2008: 28) had a less critical approach to governments and institutions “utilizing volunteers to fill gaps in services” but also observed this phenomenon, considering that “volunteerism is itself a policy topic but also a tool for policy and policy implementation.”

Herrmann (2020) found that the commitment in the help to refugees in 2015 and 2016 by volunteers in Germany “was seen as a basic principled response, rather than a question of specific interests or political agendas.” Volunteers also “thought it took a specific personal disposition to want to help – one that others may not have.” (ibid: 214). These two findings raise the question of the drivers of the commitment, that my thesis aims at answering, drawing on Herrmann’s research but with different results.

3.3 Solidarity during the Covid-19 crisis

The impact of the lockdown and the pandemic on migration, migrants and solidarity has interested researchers, also for its unique occurrence. Some have written about the impact on migrants’ rights (Parrot, 2020) and on mobility (Dumont, 2020). However, the short time frame – of the lockdowns in Europe in spring 2020 and of the timeline of this thesis – has limited the amount of research that can be included about this topic. Yet, resources like webinars were particularly useful and I could review some of them. In Denmark, researchers from the University of Copenhagen quickly started to investigate volunteering efforts during the pandemic (Sociology.ku.dk, 2020). One of the scholars leading the research, Jonas Toubøl (2020), explained in a webinar that in Denmark, around half of the population helped others some way or another and that help was primarily organized in informal networks rather than formal organizations. One other interesting preliminary finding was that risk and trust perceptions were highly heterogeneous among the people involved. In Toronto,

an organization providing social support to refugees had to adapt to the lockdown, as explained by its co-directors in another webinar (Hill and Lusztyk, 2020). Going through the adaptation of the activities and the impact on volunteers, they explained that many new volunteers also signed up. One of them also noted

I think some volunteers are really also finding a sense of purpose and community in this work when they may be facing losses in other areas of their life, whether it’s loss of employment, or frustration and not being able to connect with family members in person. In that sense, the situation of crisis can itself be a motive for getting involved or staying involved.

3.4 Contribution of the thesis

The studies presented in this section have investigated motives for helping and solidarity with migrants. In Germany, Herrmann (2020: 206) examined “why previously unsupportive strata of society came out volunteering for refugees in 2015” and tried to find the “motives and triggers that brought them to volunteering.”. Triggers are external factors that make a person deciding to commit. They are more direct than the internal factors, that can be understood as more long term, deep factors, what Herrmann calls “values.” I align myself with this argument in this thesis, since I identify different types of drivers of the commitment of people helping migrants in Grenoble that I divide between internal (motives) and external (triggers). However, I demonstrate in this study that both triggers and motives are necessary for a person to decide to commit.

This multidisciplinary approach contributes to the field of migration studies on solidarity with migrants through the analysis of the participants’ understanding of their commitment. In combining sociology, political science and social psychology, I show the intertwining of the different types of factors (internal and external) of solidarity action. Those factors have been identified by research as having an impact, but the fact that their combination plays a role has never been studied before. Finally, the research provides helpful insights for actors involved in the support to migrants, trying to draw some lessons from the ‘crises’, and help prepare better for this kind of unique situation, be it a global pandemic or a new ‘refugee crisis’. Civil society organizations struggle sometimes to get some perspective on the work they do and the way they use volunteers since they are often working in a fast-paced environment (Snyder and Omoto, 2008). Investigating why people help and how their engagement is shaped also gives an insight on how to recruit volunteers, how to make people interested in helping. In that sense, this thesis is also a societal contribution.

4) Conceptual framework

In this section, I present the concepts and theoretical approaches that will help me analyze the findings in section 6) and give an overview of important theories connected to solidarity that are relevant to answer the research questions.

4.1 Solidarity

Solidarity is a broad concept that has been studied for a long time. Scholars have identified many reasons why we act on solidarity towards others: because they look like us, because we identify with their distress, because we share an ideology, because we are part of the same nation or because we feel like we have common interests (Stjernø, 2009: 18). Stjernø (2009) explained that solidarity existed before the concept was coined by research, in feudal societies in which social and family ties led people to support and help each other, along moral norms. Solidarity also existed in the form of “fraternity” (ibid: 26) in the Christian era, and later in France it was understood by philosophers in the context of social unrests and revolutions as “a way to combine the idea of individual rights and liberties with the idea of social cohesion and community” (ibid). With the birth of Marxism, solidarity became an essential mean of the working class’s unity in its struggle against capitalism (ibid).

According to Giugni and Passy (2002), the solidarity movement has been inspired by three traditions: Christianism, the humanist component of the Enlightenment, and socialism. During the two World Wars, many organizations, drawing from these three traditions, were offering relief or assistance in the form of voluntary associations. However, for the authors, their action was not political: “they provided assistance, but in the absence of sustained political claim-making addressed to power holders” (ibid: 9). One had to wait until the 1960s-1970s for a new social movement to emerge, in which organizations were still providing assistance, but whose actions included this claim-making dimension, that is, the birth of what we now call advocacy (ibid: 10). For the authors, “the new lines of conflict, which stem from the transformation of contemporary society, have given birth to a new political actor.” (ibid: 11).

Banting and Kymlicka (2017: 6) focused on what they call societal solidarity, which is distinct from “pure humanitarianism.” This distinction is made with the notion of in-group and out-group members: “We might say that justice amongst members is egalitarian, whereas justice to strangers is humanitarian, and social justice in this sense arguably depends on bounded solidarities” (ibid:

6). To them, solidarity is in fact a “set of attitudes and motivations” (2017: 3). They insist on the importance of bounded solidarities, which is the necessity to connect with others, as different as they might be from us, in order to build solidarity across different ethnic and religious backgrounds. Miller, who wrote a chapter in the edited book by Banting and Kymlicka, goes further in distinguishing solidarity among members of a group and solidarity with outsiders. He argues that if solidarity is only about having common features with people, then being human should be enough to express solidarity with everyone. In fact, it is “much narrower than this in practice” because there has to be a “we that feels and practice solidarity” in a reciprocal manner (Miller, 2017: 63). In that sense, for Miller but also others (Stjernø, 2009; Batson, 1995; Stürmer and Snyder, 2010) solidarity has to be distinguished from altruism, which is “helping people in need with no expectation of return” (Miller, 2017: 63).

4.2 The psycho-sociological approach

Another approach to the help to others comes from social psychology, in particular with the concept of prosocial behavior. It is simply defined as the study of “actions that benefit others” (Stürmer and Snyder, 2010: 59). One prominent scholar in this field is Daniel Batson, who wrote about the reasons why we decide to act for public good and why we help others (1995) and identified four of them: egoism, altruism, collectivism and principlism. Batson (1991: 6) defined altruism as “a motivational state with the ultimate goal of increasing another’s welfare”. He tried to answer the question “does altruism exist?” for a large part of his career and tried to challenge the way our belief and scientific system as a whole has been based on the assumption of “universal egoism” (ibid: 3). He focused on motivations of people, not the consequences of their acts, and distinguished between intermediate and ultimate goals, the latter being the one that is important for the altruistic hypothesis to hold. He also explained that we can have both altruistic and egoistic goals at the same time when acting, which sometimes leads us to “motivational conflict” (ibid: 8). In addition, self-benefits can be unintended, which means that it does not invalidate the altruism hypothesis. To take an example, when deciding to get involved in food distributions, one often gets some self-reward of satisfaction like a social status. These are benefits, that can be unintended, or intermediate goals. Yet, if the person decided to get involved not in order to get social status or self-reward, but because they want to increase the welfare of people in need of food distributions, they are still doing it for altruistic reasons.

Bar-Tal (as cited in Guigni and Passy, 2002) adds other dimensions in his definition of altruism: altruistic behavior (a) must benefit to other persons, (b) must be performed voluntarily, (c) must be performed intentionally, (d) the benefit must be the goal by itself, and (e) must be performed without expecting any external reward.

In his later work, Batson decided to follow the lead of empathy, convinced that it might prove that altruism could actually exist. He reached a “tentative conclusion that feeling empathy for a person in need evokes altruistic motivation to help that person” (1995: 373). Segal (2018) wrote about more specifically social empathy. First, she defined empathy broadly as “experiencing the suffering of others, that is, we share the distress of another” (ibid: 3). Then she distinguished between interpersonal empathy, which is “mirroring the physiological actions of another, taking the other’s perspective, and while doing so remembering that the experience belongs to the other and is not our own” and social empathy which is “the ability to understand people and other social groups by perceiving and experiencing their life situations” (ibid: 4). To her, social empathy means being aware of the context, the history and the structural nature of inequalities. It has a political dimension because it makes people aware of the imbalance of power between groups and is anchored in a process of changing this state of things. Segal argued that “being socially empathic has the benefit of helping us to feel part of the larger society, which is empowering. We feel that we can have an impact on the world outside us, that we matter and make a difference” (ibid: 177).

Making a difference at the societal level entails for many scholars a political dimension of one’s action of solidarity. This is why this approach will be needed too in order to frame the topic at stake completely.

4.3 Disagreement, resistance and political solidarity

The political dimension of solidarity, and particularly in the sense of resistance and reaction to injustice, is another interesting field for understanding the matter at stake in this thesis and the importance of political solidarity.

Political solidarity has been theorized by Sally Scholtz (2008) amongst others. The specificities of this kind of solidarity is the relationship to the society and the social world, that “indicates political activism aimed at social change” (ibid: 5). She further defined the concept as “a moral relation that marks a social movement wherein individuals have committed to positive duties in response to a perceived injustice” (ibid: 6). This type of solidarity can be motivated by various types of reasons,

from which she mentioned “feelings of indignation, experiences of oppression or injustice, desire to care for others who are suffering, or even employment situations.” (ibid: 72). When it comes to the form and scope of political solidarity, she understood it as the commitment of individuals in collective action. However, this does not mean that solidarity in general is necessarily collective:

[t]he first characteristic is that solidarity mediates between the community and the individual. That is, solidarity is neither individualism nor communalism but blends elements of both. Individuals are valued for their uniqueness but solidarity is also a community or collective (whether it be the formal state, society generally, or some subgroup or voluntary association). (ibid: 18).

Another characteristic of political solidarity which distinguishes it from what she called social solidarity, is the place given to “moral requirements” (ibid: 70). In social solidarity, they are present, but secondary, whereas they are a necessary and crucial feature of political solidarity. Featherstone (2012: 5) saw solidarity “as a relation forged through political struggle which seeks to challenge forms of oppression.” This struggle is not, in his view, the one that has been recounted as led by elites; he emphasized the importance of anti-colonial movements and thinkers and of a bottom-up dynamic that is contradicting the usual theorization of internationalism. Featherstone further argued that solidarity in its active form can only be political:

At first sight the idea that solidarity is the expression of an underlying human essence might seem incontrovertible and appealing. Indeed, it might seem pretty miserly to argue against a solidarity based on such firm foundations. The problem with such an account of solidarity is that it doesn’t enable ‘movements’ or political activity any agency or role in shaping how solidarities are constructed. (ibid: 19)

Rejecting the hypothesis according which we would be in “post-political times,” Featherstone argued that center-left and right-wing politicians tried to created “forms of political managerialism where conflict and contestation are eviscerated in diverse contexts” (ibid: 95). However, to him this does not mean that political movements and struggles have lost their importance; he argued that they are happening outside of “the narrow limits of ‘organized’ politics” (ibid).

One prominent scholar in the matter of politics is Rancière, who argued for the importance of “dissent” for politics and democracy to exist. Rejecting the model of consensus-based systems, Rancière theorized a model that opposed the police and the politics. The police, in the sense he intended it, has – almost – nothing to do with officers in uniform, but was a way to designate the

way experts in power decide on what is worth considering important to deal with politically – what he called “the givens” (Rancière and Panagia, 2000: 124). And in this system, he argued that

This extreme situation recalls what constitutes the ground of political action: certain subjects that do not count create a common polemical scene where they put into contention the objective status of what is “given” and impose an examination and discussion of those things that were not “visible,” that were not accounted for previously. (ibid: 125).

Rancière therefore saw the police as deciding “who counts and they decide that some do not count at all.” (Deranty, 2014: 63). Deranty summarized well what is the political and democracy for Rancière

It is something they do. They do it when they act together, alongside those in solidarity with them, under the presupposition of their equality within a police order that does not recognize that equality. Such a thought of politics is timely. In a period in which we are encouraged to become passive, to expect rather than to act, to shop rather than to organize, there are fewer theoretical tasks more urgent than that of reminding us that for politics to become our politics, we cannot be its audience; we must instead be its actors. (ibid: 79). That is why politics is about dissensus in the conception of Rancière, particularly the dissensus “about the givens of a particular situation” and not really in the sense of the “opposition of interests and opinions.” (Rancière and Panagia, 2000: 124).

Political solidarity in the sense of being involved in a movement that contests the state of politics on migration is an important approach to address the issues raised by this thesis. However, help to others does not always take the form of solidarity movements or activism, it can also come from the humanitarian perspective.

4.4 Humanitarianism and moral principles

The moral dimension of commitment to helping is also very present in the literature. Fassin (2011) argued that moral sentiments have become an important driver in politics and have given its importance to humanitarianism. In that way, there has been a transformation of the dynamics leading to volunteering, solidarity and charity: compassion and moral indignation at the suffering and injustice have replaced an engagement that previously would have happened in the framework of a political action. However, Redfield (2012) was skeptical towards a moral action that would be apolitical or anti-political. To him, even people involved in humanitarian action who refuse to

frame their action as political, arguing that the only driver is moral values, have a “social conscience” (ibid: 455). They are therefore involved in a political arena, whether they like it or not (ibid). Feischmidt and Zakariás (2018) conceptualized two dynamics in the correlation between charity and politics in the context of the refugee crisis. On one hand, they say that there is “politicization of charity,” which is an “increasing public awareness and responsibility implied by (actual or symbolic) charity activities.” On the other hand, “charitization of politics” is the fact that a political position – like the rejection of the politics on migration in this case – leads to implication in charity or what they call “civic helping” (ibid: 60). They argued that “charity activism in support of refugees appears to be a novel form of giving voice to positions concerning political actors and political responses to the so-called refugee crisis” (ibid). In that sense, charity or humanitarianism in the field of solidarity with migrants is getting political.

5) Methodology

5.1 Ethnographically inspired research

This thesis is an ethnographically inspired case study about people volunteering to help migrants in Grenoble and its region. The approach adopted is – as in an ethnography – iterative; in a first step, some theoretical research served as an orientation to guide the fieldwork. The analysis of the material then helped select more precisely the relevant theories and concepts to understand the phenomenon. In that sense, it was a “weaving back and forth between data and theory” (Bryman, 2012: 26).

5.1.1 Methods, sampling and access to the field

The methods used include, as a main source, qualitative interviews and some informal interactions and non-participant observation. The interviews with the volunteers were semi-structured, while the one with the coordinators were between semi-structured and structured interviews. I have distinguished them as in-depth (volunteers) and informative (coordinators) interviews.

The interviews were conducted face-to-face, through phone or telecommunication applications. The fact that most interviews happened remotely is directly linked with the lockdown of the spring 2020 in France, where many charity organizations’ field activities were on hold and physical encounters with people from outside one’s household were either forbidden or discouraged. To access the field, I used a combination of my personal network and of the snowball sampling (Bryman, 2012). Being a partial insider allowed me to access participants easily (section 5.3). Additionally, my knowledge of the field allowed me to spot the organizations that were involved in supporting migrants in Grenoble.I also used several online platforms and websites referencing civil society organizations by categories (Le Tamis Grenoble, 2020) and the website of Migrants en Isère, the network of associations involved with migrants in the département and then directly contacted the organizations by email. With both methods, I used snowball sampling, mostly with coordinators of associations that put me in contact with volunteers, other organizations’ coordinators or directed me towards organizations that they deemed relevant. This method is common in ethnography and useful because it makes the sampling easier and faster, which was convenient for the short time span I had. As Bryman (2012: 424) writes, “Much of the time ethnographers are forced to gather information from whatever sources are available to them.” I wrote an interview guide (see Appendix 3) with open-ended, broad questions informed by key

concepts and themes from the study of the literature and theories. In line with the iterative approach, I adapted the guide along the way.

5.1.2 Validity and reliability

The reliability of the method is quite high, as semi-structured interviews are a good way to collect data about the respondents’ self-perception which fit with the ethnographic approach. Because of the type of research design, there is a trade-off between internal and external validity. The case study of a specific topic on a reduced population and in a small geographical area means that potential for generalization is quite low. However, it is not impossible that some findings and conclusions of the study have somewhat a representative power, as Bryman (2012: 70) puts it:

“case study researchers do not delude themselves that it is possible to identify typical cases that can be used to represent a certain class of objects.”

5.1.3 Delimitations

The target group for this study includes volunteers and people involved in coordination of organizations supporting migrants in Grenoble and the Isère department. This selection has implications for the interpretation of the results in the analysis. The advantage of such a sample is to allow an in-depth investigation about the drivers of the commitment in helping. However, the fact that the sample does not include people who are not involved limits the scope of the findings about the activation of solidarity, or about the non-activation more precisely. This is something that would be interesting for future research.

5.2 Material

5.2.1 Organizations

People who decide to help can do it individually, but in the case of help to migrants and vulnerable populations in France, they usually end up doing it in the framework of collectives or associations. The associations – which are the most common form of civil society organizations in France – also differ in their types. In this thesis, I use the words association, organization and NGO interchangeably since they entail the same status.8

8 For an overview of the different legal status of associations in France, see

I distinguish between what I call (a) action-oriented organizations [associations caritatives], (b) action-oriented and ‘moderate advocacy’ organizations and finally (c) activist or militant organizations [associations militantes]. Action-oriented organizations [1 and 8] are focusing on relief and on answering the needs of people in more or less vulnerable situations. They do not try to advocate for a societal change on migration. ‘Moderate advocacy’ associations [2, 3, 4, 5 and 7], often because they are beneficiaries of funding from some state or local institutions, make sure to be ‘soft’ in their advocacy activities, worried to lose their funding. But some of them also do it because they are not interested in getting political, in the vein of “depoliticization of charity” (Feischmidt and Zakariás, 2018).Finally, militant associations [6, 9 and 10] are political and are usually very critical about the policies and government’s action on migration. They do not hesitate to come into conflicts with the authorities and to support civil disobedience actions. Many organizations combine different types of activities. It includes accommodation of asylum seekers and other migrants, social integration (French classes, social activities), relief and humanitarian assistance, advocacy and legal aid. A detailed table of the organizations can be found in Appendix 1. In the analysis of the material, no information is given about the organization unless it is needed or important for the point that has to be made.

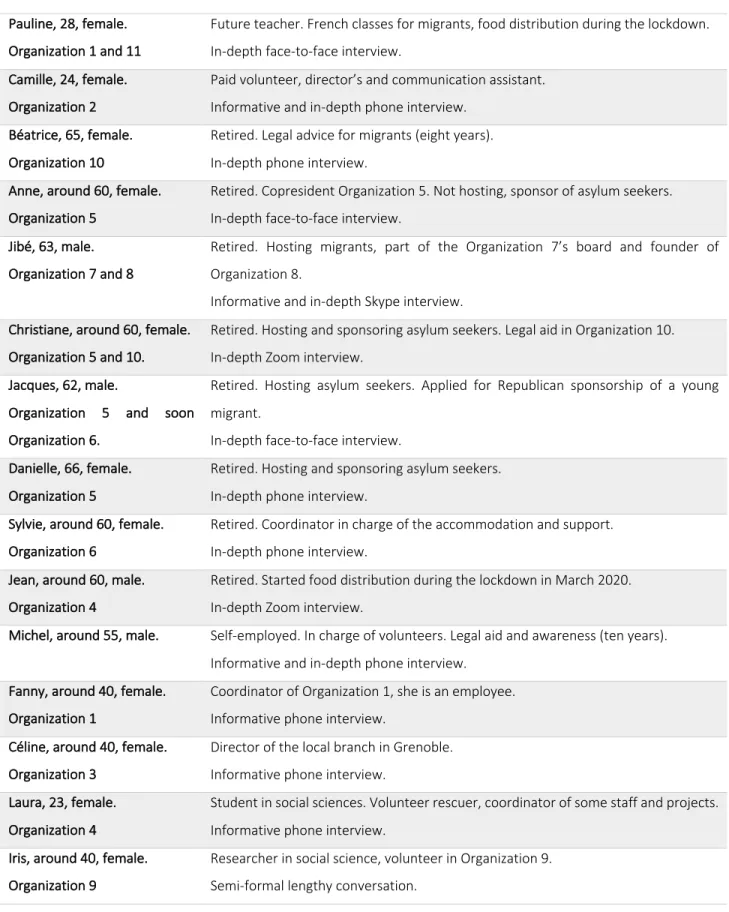

5.2.2 Interviewees and other interlocutors

The interviews lasted between forty minutes and one hour and fifteen minutes. Five took place through phone, three through video telecommunication and three in person. I also had several informal conversations with volunteers and coordinators that gave me access to important information. In total, I conducted eleven interviews with four men and seven women, aged between 24 and 66 years old, with a majority of them (eight) that were retired and therefore over 60. The table including the interviewees can be found below, and a detailed one is included in Appendix 2. The citizens involved in solidarity do not all consider themselves as activists. This is why it is challenging to find a word to talk about them. In this thesis, using their own words, I refer to them as volunteers [bénévoles], helpers [aidants], solidaires,9 or sometimes a more general term: people

involved in solidarity.

9 “Solidaire” is a French word that could be translated as “solidarian” and has been increasingly used by people

involved in solidarity with migrants to talk about themselves since 2015. This adjective has become a noun, similarly to what Rozakou (2016) describes about the word in Greek in her study about solidarity with migrants and asylum seekers in Greece.

Table 1: interviewees and interlocutors

Pauline, 28, female. Organization 1 and 11

Future teacher. French classes for migrants, food distribution during the lockdown. In-depth face-to-face interview.

Camille, 24, female.

Organization 2

Paid volunteer, director’s and communication assistant. Informative and in-depth phone interview.

Béatrice, 65, female.

Organization 10

Retired. Legal advice for migrants (eight years). In-depth phone interview.

Anne, around 60, female.

Organization 5

Retired. Copresident Organization 5. Not hosting, sponsor of asylum seekers. In-depth face-to-face interview.

Jibé, 63, male. Organization 7 and 8

Retired. Hosting migrants, part of the Organization 7’s board and founder of Organization 8.

Informative and in-depth Skype interview.

Christiane, around 60, female.

Organization 5 and 10.

Retired. Hosting and sponsoring asylum seekers. Legal aid in Organization 10. In-depth Zoom interview.

Jacques, 62, male.

Organization 5 and soon Organization 6.

Retired. Hosting asylum seekers. Applied for Republican sponsorship of a young migrant.

In-depth face-to-face interview.

Danielle, 66, female.

Organization 5

Retired. Hosting and sponsoring asylum seekers. In-depth phone interview.

Sylvie, around 60, female. Organization 6

Retired. Coordinator in charge of the accommodation and support. In-depth phone interview.

Jean, around 60, male. Organization 4

Retired. Started food distribution during the lockdown in March 2020. In-depth Zoom interview.

Michel, around 55, male. Self-employed. In charge of volunteers. Legal aid and awareness (ten years).

Informative and in-depth phone interview.

Fanny, around 40, female. Organization 1

Coordinator of Organization 1, she is an employee. Informative phone interview.

Céline, around 40, female. Organization 3

Director of the local branch in Grenoble. Informative phone interview.

Laura, 23, female. Organization 4

Student in social sciences. Volunteer rescuer, coordinator of some staff and projects. Informative phone interview.

Iris, around 40, female. Organization 9

Researcher in social science, volunteer in Organization 9. Semi-formal lengthy conversation.

5.3 Positionality

Like Hansen (2019: 33), I consider myself in this work a “partial insider” “and a partial outsider”. I am a partial insider since I am a native from the region I am studying; I already had some knowledge about migration and solidarity in Grenoble and around, and I have close ties to people that are involved in solidarity organizations, who belong therefore to the population I am studying. I am a partial outsider because I am not engaged myself in an organization and I am not involved in solidarity action physically. This particular position has advantages and disadvantages.

First, my network allowed me to find participants more easily, which helped me save precious time to conduct the research. Second, the fact that I am familiar with some of the organizations’ work and activities also gave me opportunities in the past to observe relevant events and dynamics. Additionally, the fact that I know some of the participants personally probably improved the quality of the interviews, since the trust relationship already existed and that people were already aware of my position and of who I am, contributing to the internal validity of the work. Indeed, one can hope that the participants talked to me more honestly and as they would talk to a peer, allowing the information to be close to an accurate depiction of their mental and psychological processes. Moreover, it is true that this partial insider position has influenced my perception and framed my understanding and work. Particularly, I also draw on Hansen’s take on the role of emotions (2019). While unlike her, I did not place myself bodily with the volunteers, my experience was similar with regards to the emotions felt at the time: stress and anxiety due to the uncertainty of the situation (the Covid-19 pandemic), guilt and outrage at the situation of migrants and asylum seekers who were “left behind” in this crisis (Stangler, 2020; Pascual, 2020). In that sense, my experience as a researcher was the same as most of the people I interviewed and allowed me to be aware of the challenges and lived experience of the interviewees. Some challenges specific to conducting research during the lockdown were similar to the one encountered by people involved in solidarity work – restrictions and adaptation of the work, emotional distress due to the pandemic and loss of freedoms, feeling of helplessness. Moreover, the fact that I was able to ask people about an experience that they were living and discovering at the same time as me made the data very valuable and unique and therefore participated to its internal validity. This also helped me grasp the specificities of the sensation people had regarding the uncertainty of this situation and of how long the situation would prevail, accessing direct information about how it was affecting their engagement and motivation. This experience is common in ethnography, and is part of the

also important as a researcher in such a position to reflect on this, and to “read the effects” of my identities and positionality on the work (Hansen, 2019: 144).

5.4 Ethical considerations

All the names of the participants have been changed to prevent them from being identified and protect their anonymity, and the names of the organizations have been replaced with numbers to further prevent identification of participants. The names of the people mentioned in the interviews were also changed.

The people in my sample are not vulnerable in the traditional sense we intend it in migration studies (Hugman, Pittaway and Bartolomei, 2011). They decide to help migrants and share their resources because they can afford to do so. However, in the context of the lockdown and spreading of the pandemic, it is important to take into account the distress people can suffer from. On one hand the exceptional situation where a global pandemic is causing numerous deaths inevitably creates anxiety for everyone, concerned with their close ones and own health and life; acting in solidarity and being in physical contact with others is increasing the risk of contamination. Consequently, the mental process one goes through when deciding to help is likely modified by these circumstances. Secondly, the lockdown situation in itself is also a source of worry and discomfort and has impact on mental health (Kazmi, Hasan, Talib and Saxena, 2020). It is therefore important to have in mind the well-being of participants, especially when interviewing them. Some people could also feel guilty or worried of not being able to continue helping.

Finally, conducting interviews through phone forced me to be careful about the affective atmosphere surrounding the people I talked to: the person is alone and it is difficult to know about their emotional mindset, and hard or impossible to make sure that they feel comfortable with the questions and topics addressed (Rubin and Rubin, 2005). To avoid creating any distress, I explained at the beginning of each interview to my interlocutors that if any questions made them uncomfortable or that they did not like it, they did not have to answer them, and refrained myself from insisting when people were giving short answers. Instead, I tried to leave them space to talk, showing interest with small verbal approval.