New trends in densification projects within the Million

Homes Programme areas

Investigating new approaches for urban densification projects within the

Million Homes Program areas in the search for sustainability

Noé Alberto Carbajal Velazco

Urban Studies

Two-year Master Programme

Master´s Thesis, 30 credits

Spring Semester 2018

Supervisor: Marwa Dabaieh

Summary

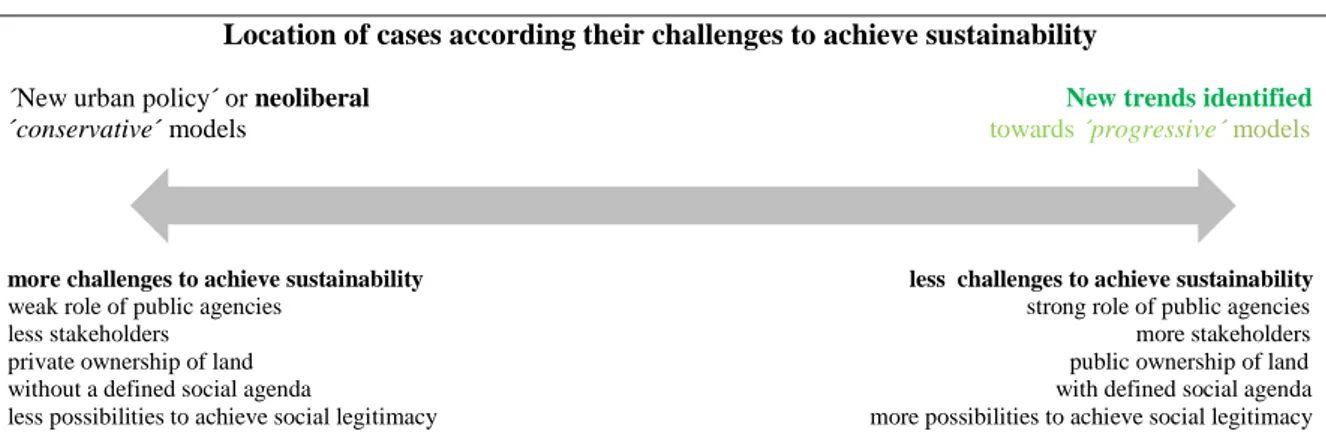

The urban densification projects launched in many Swedish cities in recent years supposedly lead to more sustainable urban environments, according to those responsible; solving the shortage of housing units and using the urban infrastructure and other resources in a more efficient way. But many of the proposed projects face a lot of criticism when they are located within the Million Homes Programme areas due to their current situation: social segregation, unemployment, as well as the perception of the permanent increase in insecurity. The voices that are raised against these projects go mainly against their models of conception and management; because those projects will not solve the social problems of the current residents; on the contrary, they will further exacerbate social differences within the city. The main hypothesis of this work is that since much regeneration or urban densification projects have already been carried out within the Million

Homes Programme areas, then there must also be some good examples that should be identified and used as

a reference to improve the urban regeneration practices in those types of areas.

The aim of this study is to investigate if within these new projects there are some that could be considered as better practices of how to do more sustainable urban densification processes in those Million Homes

Programme areas. For that the concepts of legitimacy and sustainability are crucial variables to evaluate and

identify them.Due to the limitations of the work, the first part identifies and performs a general comparative analysis of six densification projects developed within neighbourhoods built under the Million Homes

Programme located in the cities of Malmö and Växjö. In the second part, after a critical analysis two projects

are chosen that could be considered as the better practices and perform a second critical analysis to both in a deeper way, to generate the necessary discussion and finally reach conclusions and recommendations. The work is based on qualitative research and complemented with grounded theory and case-study theory, (flexible design), those that served to design specific tools for the analysis purposes of the cases.

Among the main findings during the research process were that the failures or weaknesses of some projects are mainly due to the lack of social commitment with local residents (many of them immersed in vulnerable economic and social situations) due to the distancing of the public agencies (municipalities) of the project, while in other projects a social agenda has been incorporated as part of the processes in favour of current residents, which also means the permanent commitment of local governments to these projects, actions that contribute to greater possibilities of achieving sustainability.

Keywords: Urban development, urban densification, urban regeneration, urban density, compact cities,

Acknowledgement

My thanks to all the staff of the program, that despite being new has helped me a lot in understanding the problems of the city from different angles, as well as the use of different methodologies when it comes to proposing solutions.

Thanks also to LBE Arkitekter office in Växjö, where I had a place to work on the thesis as well as to exchange ideas and receive criticism about my thesis subject.

Finally, thanks to all my family in Peru, who has always supported me to continue with this project, and of course thank you Inger and your family here in Sweden for all your important support at all times.

Glossary of terms

Bostadsrätter housing in form of condominiums Boverket the Swedish National Housing, Building and Planning Board Bokal (from bostad + lokal) Residence + local (commercial area) BoKlok (from Bo Klokt) ´live wisely´ Byggnadsnämnden municipal Build ing Committee EU European Union Fastighetsägarna the Property Owners Organization Fastighetskontoret municipal Real Estate Office Hyresrätter housing for rent

Hyresgästföreningen the Tenants National Organization

IMRAD format Introduction, Materials and Methods, Results and Discussion format MHP Million Homes Programme Miljonprogrammet Million Homes Programme PPP model Public Private Partnership model SBK / Stadsbyggnadskontoret City Planning Office UDP´s Urban Development Projects URP´s Urban Regeneration Projects UK United Kingdom WWII World War II

Table of contents

Summary and keywords ……….. 02

Acknowledgements ………. 03 Glossary of terms ………. 04 1.0 Introduction ………...07 1.1 Background ………. 07 1.2 Research questions ………. 08 1.3 Previous research ………..……….. 09

1.3.1 Previous terms and concepts used in the urban development process .……….. 09

1.3.2 The concept of urban regeneration ……… 09

i. Some critical voices against urban regeneration ………... 10

1.3.3 The urban form and sustainability ………. 11

i. Compact cities and density ……… 11

1.3.4 Experiences about urban regeneration approaches in the MHP areas within the Swedish context ………... 12

i. The Bokals, projects seen as successful examples within MHP areas ………….. 14

1.3.5 The concepts of sustainability and legitimacy ………... 15

i. Sustainability ………. 16

ii. Legitimacy ………. 17

iii. Social sustainability and legitimacy in urban regeneration projects ………. 17

1.3.6 Summarizing the previous research ………... 18

1.4 Aims of the study ……… 18

1.5 Objectives of the study ……… 19

1.6 Outcomes of the study ………. 19

1.7 Method ………. 19

1.8 Layout of the document ………... 19

2.0 Methodology and the materials …...……… 21

2.1 The research process and methodological strategy ……….. 21

2.2 The material (primary and secondary data), limitations and reliability of the study ….……….. 22

2.2.1 Written and graphic material ………. 22

2.2.2 Interviews ……….. 22

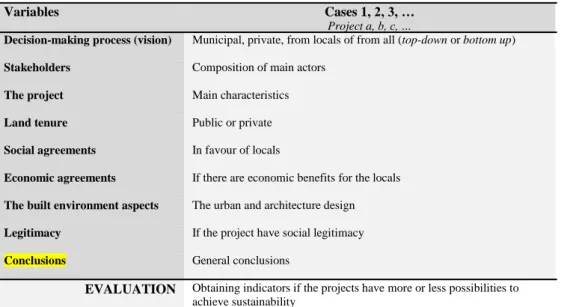

2.3 Tools for evaluation ………. 23

2.4 The selection of cases ……….. 24

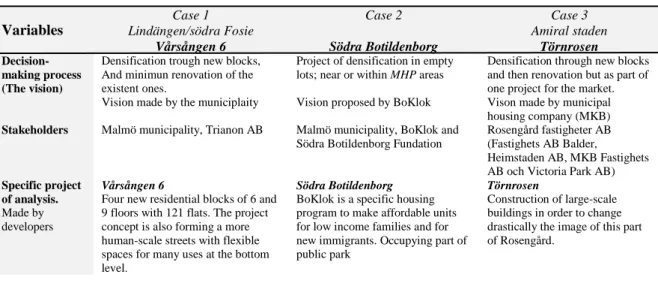

2.5 The six projects and a comparative analysis of their characteristics ………... 24

2.5.1. Projects in Malmö ... 24

i. Lindängen/södra Fosie context and ´Vårsången 6´ project (case 1) ... 24

ii. Södra Botildenborg project (case 2) ……… 25

iii. The Törnrosen project (case 3) ……… 26

iv. Comparative analysis of Malmö projects ……… 27

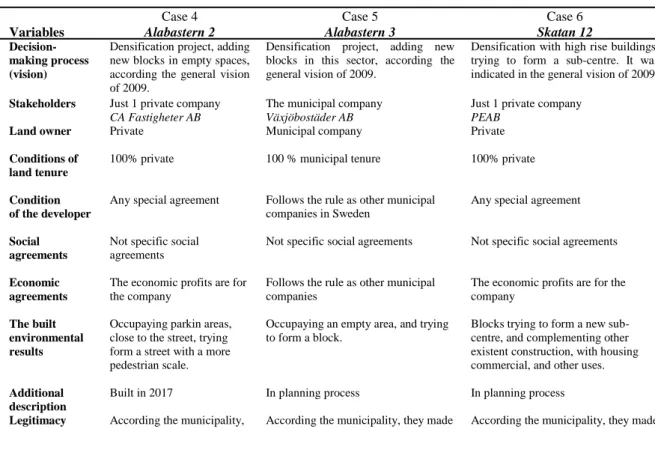

2.5.2. Projects in Växjö ………... 29

i. Alabastern 2 (case 4) ………... 29

ii. Alabastern 3 (case 5) ………... 30

iii. Skatan 12 (case 6) ……… 31

iv. Comparative analysis of Växjö projects ……….. 31

3.0 Results ………..………..………... 33

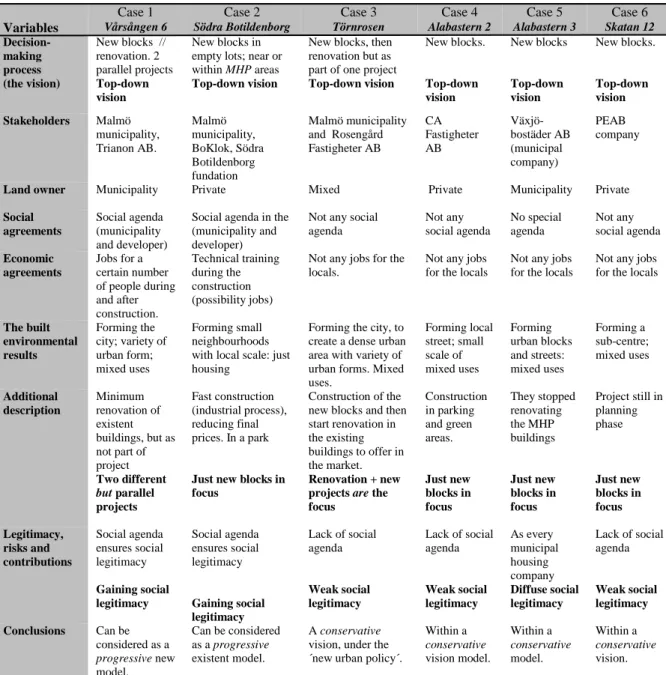

3.1 First level evaluation: Critical analysis and results of the six cases ……… 33

3.1.1 First general critical analysis evaluation of the six cases (grounded or comparative method) ………. 33

3.1.2 Second general critical analysis of the six cases (case-study methodology) …………. 34

3.2 Second level evaluation: Critical analysis and results of the two final cases ....……...………... 35

3.2.1 Case 1: The Vårsången 6 project ………... 35

i. Description of the project ……… 36

ii. The social agenda ………... 37

iii. Summary ………. 37

3.2.2 Case 2: The Södra Botildenborg project ………... 37

i. The BoKlok concept within the context of MHP areas ………... 37

ii. The incorporation of an official social agenda ………... 38

iii. Summary ………. 39

3.2.3 Final results of critical analysis evaluation between Case 1 and Case 2 ………... 39

i. First critical analysis evaluation …..……… 39

ii. Second critical analysis evaluation ..……… 40

4.0 Discussion ………...……….... 42

4.1 The densification experiences in MHP areas ………...…… 42

4.1.1 Urban densification as urban policy in Sweden ……… 42

4.1.2 Densifying the MHP areas ………. 42

i. The MHP areas context ………..……… 42

4.2 Discussion about the analysed cases ………….………... 43

4.2.1. Discussion about the findings (6 cases) ………. 43

4.2.2. Discussion about the results of cases 1 and 2 ……… 44

5.0 Conclusions, recommendations and future research ………. 46

5.1 General conclusions ………. 46

5.2 Recommendations ……… 47

5.2.1 Developing more the general suggestions in the built environment aspect ...………... 47

i. Recommendation on the urban scale ………... 48

ii. Recommendations at the local scale – the architecture ………... 48

5.3 For future research ………... 49

6.0 References ……….. 50

7.0 Annexes ……….. 54

Annex 1: Format of questions for those responsible for companies that work in densification projects within the MHP areas .……….…….. 54

Annex 2: Format of questions for those responsible in the municipalities ………. 55

1.0 Introduction

In this chapter the background of the study is discussed as well as the previous literature research about the subject; if there are new trends in densification projects within the Million Homes Programme areas with more possibilities to achieve sustainability. Also the research questions are developed as well as the main aims, the objectives, and the outcomes of the study, ending with the used methodology and explaining the lay out of the document.

1.1 Background

Nowadays the World Bank (2018) considers that urban development1 is crucial, since currently 4.5 billion people (54% of the world population) lives in urban areas, and by the year 2045 the urban population will be a total of 6 billion. The World Bank also highlights that more than 80% of the world´s GDP is generated in the cities, so that urban development can contribute to sustainable growth if it is well managed, increase productivity, and allow innovation and new ideas to emerge. Moreover, urban development is very closely related to density2. Mcfarlane (2016) argues that the urban density is and has been a key word throughout the

history of how the city has been conceived and understood, and he believes also that it is firmly back on the global urban agenda, but still with a deficient definition. So in that sense, it is possible to argue that the process of densification3 of urban areas is a ´natural´ process, depending on economy and market fluctuations in the cities and in its societies, but sometimes due to social or political expected and unexpected events at local, national or global levels appears the urgency to quickly build significant amounts of housing units, services and urban infrastructure, and as a consequence of this, certain areas of the cities undergo accelerated processes of densification, to which it is necessary to respond appropriately.

In the European context, currently cities have the need to densify due to two main reasons: the natural European´s population growth as the World Bank (2018) asserts, and the great flow of immigrants from outside the borders of the European Union in recent years. The first reason is also explained by Colantonio & Dixon (2011) when they argue that due to the natural growth and development of the local population makes the cities have an accelerated urbanization process occupying valuable land for agriculture. The second reason is explained by Park (2015), who argues that these flows of migrants and refugees into Europe presenting to the European leaders and policymakers the greatest challenge since the debt crisis. Moreover, Carrera, Blockmans, Gros & Guild (2015) argue that this situation reached very high flows of immigration especially during the European migrant crisis during the 2015 when hundreds of thousands of people crossed the borders of the European Union (EU) escaping from the political persecution and civil wars in their countries during the Arabic spring, testing the capacity and legitimacy of the EU in responding to these sorts of humanitarian crisis, and putting huge pressure on the European institutions and member states´ governments. Consequently, migration policies are now at the top of the EU policy agenda.

Sweden as member of the EU has not been an exception to this crisis, on the contrary, many immigrants have been coming to seek asylum in the country due to its well-known social welfare system. They were first placed in temporary residences (in precarious conditions in many cases) and then when the migrants have been accepted as refugees, many of them moved into the neighbourhoods built during the Million Homes

Program (MHP) era (Miljonprogrammet) between the years 1965 and 1974 (Andersson, Bråmå &

Holmqvist, 2010; Arnstberg, 2011; Vidén, 2012; Boverket, 2015), because they have relatives there or know people there or because they feel closer culturally in those areas, and also due to the rent prices and availability of housing units.

This phenomenon does not always produce desired consequences due to the characteristics of these neighbourhoods, for instance some of them are physically isolated from the rest of the city. Together with the

1.

Urban development: [noun geography] ´the development or improvement of an urban area by building´, (Collins Dictionary, n.d.). 2

Density: The quantity of people or things in a given area or space. ‘areas of low population density’ [count noun] ‘a density of 10,000 per square mile’, (English Oxford Dictionaries, n.d.).

high concentration of immigrants (Parker & Madureira, 2016) this creates negative impacts in those areas; high percentages of unemployment, social stigmatization, social segregation and finally the perception of increasing criminal activities, affecting the lives of the current residents and to those new immigrants as well. Then the municipalities and those responsible for those economically and socially vulnerable areas4 have begun to build projects of renovation and densification of those neighbourhoods trying to improve them, but not always with recognised good results because many of those projects supposedly create rapid processes of ´gentrification´5 (Swyngedouw, Moulaert, & Rodriguez, 2002; Parker & Madureira, 2016), on the one hand, and are the centre of very strong criticism especially by the media, involving them in very long processes of negotiations (e.g. Amiral staden project in Rosengård, or Lindängen/Södra Fossie, both in Malmö) or stopping them indefinitely, on the other hand (Palm, 2016; Wall, 2016; Fjellman, 2016).

However, there is a consensus to densify the MHP areas in nearly all cities in Sweden, (Fastighetsägarna, 2010; Malmö Stadsbyggnadskontor, 2010; Edeskog, 2015; Boverket, 2017). However, the densification per se, is apparently one aim and not an urban integral strategy, because it needs to be within a range of actions (Roberts, Sykes, & Granger, 2016) to obtain sustainable results. Apparently it is not yet clear in which methodology this process should be incorporated in, in order to guarantee the proper sustainability of these areas of the city. Because and according to the lines above, it is considered that there were many errors in the previous densification projects, but also that some better practices have been made or are in process (Boverket, 2017).

This work emphasizes that right now, due to the researchers, academics and also some responsible authorities (mainly from public agencies) for the MHP areas are looking for new forms to make urban densification projects, where current residents, local grassroots organizations and the public in general (the city) should gain and obtain more benefits, in order to bring legitimacy to those new approaches that could guarantee harmonic and more sustainable results. The object of this research work is to try to identify some of those densification projects (in Malmö and Växjö) that can be considered as better practices, and specifically which actions within those built projects or in the final stages of planning could be considered as crucial aspects for achieving more sustainable urban environments.

1.2 Research questions

Why some already built densification projects in the Million Homes Programme areas can be

considered as better practices, and are they sustainable?

What impacts have these better practices projects of densification created in the Million Homes Programme areas and in the rest of the city?

How do these new approaches or forms of urban densification projects guarantee the achievement of sustainability and attract more investment for densifying those Million Homes Program areas, at the same time?

4The Swedish governmental institutions have categorised those areas in three levels as: particularly vulnerable areas/särskilt utsatta områden, risky areas/riskområden and vulnerable areas/utsatta områden, (Polisen, 2015).

5The term was coined by sociologist Ruth Glass in 1964, who is quoted below. "One by one, many of the working class quarters of London have been invaded by the middle-classes—upper and lower. Shabby, modest mews and cottages—two rooms up and two down—have been taken over, when their leases have expired, and have become elegant, expensive residences ... Once this process of

'gentrification' starts in a district it goes on rapidly until all or most of the original working-class occupiers are displaced and the whole

1.3 Previous research

The urban development, densification and sustainability in the international context

In order to understand which sort of methodologies and strategies of urban development have been used in those specific MHP urban areas in the Swedish cities, a review is made of the most common and known concepts and methods in the search to substantially improve the quality and the sustainability of existing urban areas in critical situations in the international context especially in the European countries.

So how those processes of urban development could be called? Urban renewal, urban regeneration, or just urban densification process, or something else? It should be noted that this research covers only the post-war stage, which is from when European cities have been developing ´normally´, without stages of mass destruction or other catastrophic events.

1.3.1 Previous terms and concepts used in the urban development process

Beswick & Tsenkova, (2002) made an overview of the urban development policies objectives, initiatives, and strategies as it relates to changes in the policy environment. They identified at least five stages or urban development policies of how the economic and social policies were created and implemented in order to address and improve the economic, social, environmental and physical aspects of the urban areas after the World War II (WWII) and the decline of the industrial cities in UK as well:

- Urban reconstruction - policy of the 1950´s, focused in the reconstruction of cities and construction of

new urban areas after WWII. The task of reconstruction and development, in response to the growing needs for new family housing. Reconstruction and extension of older areas of towns and cities often based on a master plan; significant suburban growth. The social content was the improvement of housing and living standards.

- Urban Revitalization - policy of the 1960´s; which can be seen as the continuation of 1950´s theme,

and strong emphasis in suburb and peripheral growth, some early attempts of some few existing areas rehabilitation. The social content was the welfare system improvement.

- Urban Renewal - policy of the 1970´s; with focus on in-situ and neighbourhood schemes, but there is

still strong development at periphery. The social content was community based action and greater empowerment.

- Urban Redevelopment - policy of the 1980´s; characterized by the use of many major schemes of

development and redevelopment flagship projects, focus on out of town projects. The social content was community self-help with very selective state support.

- And urban regeneration - policy of the 1990´s; Move towards a more comprehensive form of policy

and practice more emphasis on integrated treatments. The social content was the emphasis on the role of community.

Roberts, et al., (2016), also agree with Beswick & Tsenkova about the evolution of those five stages showed above, but also adding a sixth new policy which is running after the 2000´s, calling this urban regeneration

in recession, its main characteristics being restrictions in all activities with some relaxation in areas of

growth, and having as social content the emphasis on local initiatives and the stimulation of the third sector. After reviewing the evolution of urban development policies in the post-war period, it is concluded that

urban regeneration (or regeneration in recession) is still the policy that is being used until now, so it is

necessary to understand the concept more thoroughly and its implications in practice, as well as their relationship in the context of Swedish cities.

1.3.2 The concept of urban regeneration

Tsenkova, (2002) argues that the urban regeneration is the most successful approach to achieve more sustainable results. She explains that the success of the urban regeneration is due to the incorporation of social and environmental policies that resulted in a change from the previous techniques of urban renewal

and revitalization to a more comprehensive urban regeneration application. The author highlights that the

urban regeneration approach goes beyond the objectives, aspirations and achievements of the previous

concepts, because the urban renewal, is seen as a process of essentially of physical change, while urban

development (or re-development) has a very general mission and an unclear purpose, and finally urban revitalization (or rehabilitation) that although it suggests the need for action, but it does not specify a precise

method of approach.

Colantonio & Dixon, (2011) argue that the fusion of previous concepts of urban regeneration with sustainability to produce a concept of sustainable urban regeneration reflects the evolution of the different phases of regeneration. For instance, in the last definitions urban regeneration pushes the practices of consultation and participation of the locals (´community partnership´) and voluntaries (third sector) together with the state as an enabling partner, pointing out the community and the local level as the main areas for the achievement of sustainability. However, the authors also point out that there are many definitions of ´urban

regeneration´ depending on particular perspectives. Another definition that they present about the urban

regeneration is an integral vision and action that leads to the resolution of urban problems and that seeks a substantial and perdurable improvement of the economic, physical, social and environmental conditions of a specific urban area in the city.

Foultier, (2010) notes that urban regeneration policies always lead to an intense debate between two positions; On the one hand, some experts consider that the transformation of the depreciated areas is successful due to the design of the buildings, the quality of the public spaces, the urban equipment, the green areas and the maintenance services implemented (focus on physical aspects), while on the other hand, others call attention to the weaknesses and failures due to relocation strategies and the difficulties in developing an affordable offer for the most disadvantaged groups (focus on social aspects). Some factors of the urban regeneration processes that Foultier (2010) identifies are: Success factors of the regeneration process are based on an integrated approach and project management; the challenges of the years to come are; territorial policies and governance processes, urban regeneration and mobility, and the difficulties and limits are insufficient attention to relocation strategies and the fact that urban regeneration dynamics are difficult to control in a local housing market.

Roberts et al. (2016) argue that the very nature of urban regeneration makes it an activity in constant evolution. They define urban regeneration as a vision and deep integrated actions that seek to solve problems and achieve a lasting improvement in the social, economic, physical and environmental conditions of an urban area that has been deteriorating or offers opportunities for substantial improvements. Finally, it should be highlighted that urban regeneration implies that any approach to addressing urban problems must be constructed with a more strategic long-term purpose.

According to the definitions reviewed previously, the concept of urban regeneration could be recognized as the result of the evolution of other concepts used in the past. Some of its main characteristics are the incorporation of social and physical/environmental policies in the development of urban processes. Regarding social issues, the incorporation of grassroots organizations is noteworthy, seeking bottom-up visions in the initial decision-making stage of the processes, which seek to make urban projects more inclusive, and the understanding that sustainable urban regeneration implies the constant evolution of the concept itself and the need for long-term commitments of the processes.

i. Some critical voices against urban regeneration

The urban regeneration approach also faces quite serious challenges, especially in two areas; the first is during its implementation phase and the second is that this concept has been used as a propaganda poster to carry out projects that only seek private profitability.

Colantonio & Dixon, (2011) argue that the main criticism of urban regeneration has been the failure to close the socioeconomic gap between the poorest neighbourhoods and the national average. Despite the multiplicity of innovations and attempts to address the components of urban decline, a combination of poor investment and inadequacies in urban policy has consolidated symptoms of social polarization, economic

difficulties and environmental deprivation in many areas of the interior of cities. This has led to a reorientation towards social issues in regeneration, which are sometimes perceived as the softer or less tangible side of regeneration which requires new tools in the evaluation and measurement of objectives. Also Foultier (2010) recognises that the urban regeneration plans still face many challenges, especially when it is put into practice. Governments launching national programs based on territorialized approaches (with defined local actors), not sufficiently favouring cooperation between local authorities leads to the consequence that it does not generate a real strategic reflection at the metropolitan level when it comes to addressing, for example, a segregation process in housing. Also the physical solutions developed in the urban regeneration plans in general are only "corrective measures" to restore the attractiveness of the problem areas that face a process of depreciation in housing. In addition to corrective measures, it is advisable to develop a preventive approach by improving cooperation between regional and local governments, in order to better address the segregation process, and to improve the development and distribution of affordable housing in the housing market.

Swyngedouw et al. (2002) argue that the concept of urban regeneration evolved with the aim of building more sustainable cities, especially in the social aspect, but that the concept of urban regeneration ended up being used by the ruling elites as a top-down model, because the globalization and liberalization during and after the 1990´s had articulated the new forms of governance and the relationship between large-scale urban development projects (UPD´s) and the political power, the social and the economic relations in the city, calling this as the ´New Urban Policy´. The public-private partnership (PPP) model has been used to establish exceptional measures in planning and policy procedures, but usually UDP projects are poorly integrated. As a consequence its impact on the city as a whole (the environment) and on the areas where the projects are located remains ambiguous. The local mechanisms of democratic participation are not respected or just applied in a very ´formalistic´ manner, where grassroots organizations occasionally based on resistance and protests could manage to change the course of these events in favour of local participation and obtain modest social returns for disadvantaged social groups.

1.3.3 The urban form and sustainability

i. Compact cities and density

According to Heyman and Ståle (2013) one early definition relating to the urban form and sustainability was made by Jane Jacobs in 1961. She argued that the urban areas have to have a certain density to increase the diversity of uses and people, because without the help of residential density there will not be or there will be just few services in the area. Density can be considered as a way to create vitality and variations in a small area, emphasizing the combination of workplaces and houses on small scales, such as streets or even blocks, in order to increase urban life and extend it to so many hours a day as possible, enhancing the sense of security.

Burton, Jenks, & Williams, (2003), argue that on the international environmental agenda is the debate on the urban form and sustainability. Crucial concepts of discussion are what physical form cities should take in the future, and how these forms can have an effect on economic and social sustainability and on the consumption and depletion of resources. The authors, whose focus is the compact city in the context of the developed world, also argue that there is a strong link between the urban form and sustainable development. A compact city brings and encourages more possibilities for socialization, brings an efficient public transportation with it and due to its appropriate form and scale it is possible to walk, and cycle.

Burton et al. (2003), consider that the ideas behind the compact city are of crucial importance in the attempt to find sustainable urban forms, for example for existing cities. For completely new cities forms are suggested ranging from large concentrated centres to ideas of decentralized but concentrated and compact medium settlements linked by public transport systems to strategies for dispersion in self-sufficient communities. The benefits which the compact city offers according to Burton et al. (2003) are the following: it provides a concentration of socially sustainable mixed uses, concentrating development and reducing the need to travel, thus reducing vehicle emissions. Higher densities can help make services and facilities

economically viable, improving social sustainability. However, Burton et al. (2003) are aware of the criticisms that compact cities may have, as for instance Neuman (2005) argues that compact cities could also have very negative consequences such as the crowding of people leading to the loss of urban quality and life, less open spaces, more congestion and pollution, eventually discouraging many people from living there. A greater research and discussion of the theory and practice is suggested, to find the limits and the scales suitable for their implementation in complex situations. The idea of the compact city should not be seen in a simplistic way and in the case of MHP areas it is especially necessary to put particular attention to the social aspects in big scale processes of compaction or densification.

So considering the international experiences on urban development, it should be noted that there has been a fairly long process (after WWII) of efforts and experiences to achieve sustainability. But it is necessary to note that every country has a specific legislation and some are not necessary equal with others. In the case of Sweden and due to the welfare policy it has, the problems and solutions have to be managed quite different from other countries.

1950´s 1960´s 1970´s 1980´s 1990´s from 2000 until now

Post-war

Reconstruction Revitalization Renewal Redevelopment Regeneration Regeneration in recession

Improving cities, housing and living standards after WWII welfare improvement community action and greater empowerment community self-help with very selective state support

emphasis on the role of community and in social aspects

Implementation of the concept of Sustainability Concept of sustainability appeared Compact cities Urban density (Smart cities) And in the search of sustainability… New trends? Figure 01: Evolution of post-war urban development concepts that involve strategic actions to plan new urban developments as well as to improve deteriorated urban environments. Graphic based on Beswick & Tsenkova, (2002) and Roberts et al., (2016).

It is important to highlight also that the Figure 01, which is presented in a longitudinal observation form (Gerring, 2006), shows how the social content evolved in these different concepts in the effort to develop and improve urban areas; incorporating new variables in order to achieve more permanent (or sustainable) results; but it also shows that the concepts still need to continue their evolution in the future.

1.3.4 Experiences about urban regeneration approaches in the MHP within the Swedish context

Andersson et al., (2010) note that the issue of residential segregation has been on the Swedish political agenda since the early 1970s and its appearance there is linked to the emergence and critique of those new urban forms and types of neighbourhoods built as part of the MHP. In most cities, the MHP areas resulted in new developments that were added to the built environment in the urban periphery. Although the original program comprised a combination of forms of tenure and types of dwelling, the final results of the new neighbourhoods tended to be fairly homogeneous, consisting of single-family houses with their own homes or multi-family dwellings with lease or cooperative tenure. The major criticism was more focused on areas where the buildings were of great height, as well as the lack of infrastructure for socialization and lack of commercial areas, initiating efforts of regeneration just at the end of the construction. Also, due to the growing concern about segregation, shortly before the end of the MHP in 1975, the Parliament decided that the construction of new residential areas should be characterized by a more ´varied domestic composition´, remaining afterwards as a concept in all housing policies; however since the early 1990s it tended to be an objective without effective means.

Andersson et al., (2010) make an analysis of the strategies that have been applied to try to solve the segregation problem (de-segregation policies) in those areas. Those de-segregation policies are: the housing

and social mix policy, first initiated in the 1970s, the refugee dispersal policy, which was initiated in the

1980s, and the area-based urban policy (initiated in the 1990s). The authors note that the most efficient anti-segregation policy is not found in housing or urban policies, but in the policies that affect the allocation of

economic resources among the households of society. If the socio-economic distances are large, it can be assumed that segregation processes are stronger. The authors emphasize this for the welfare system that exists in Sweden. But their analysis unluckily shows that none of those three policies have been successfully managed to solve the segregation. There have just been marginal improvements. The reasons are the ineffective implementation of the mixed policy, which had as main concept a socio-economic and demographic mix, and the other two with a clear ethnic focus; defects of design in the refugee dispersion policy and conflicting objectives inherent in the area based interventions policy

(

Andersson et al., 2010). Parker & Madureira, (2016) also explain that the areas of the MHP have been the subject of extensive debates and research regarding the social aspect and maintenance challenges as well as their symbolic value and in their different contexts and in terms of physical qualities and the role they play in their particular urban environments. They note that some of these neighbourhoods are very segregated and stigmatized and addressing that stigmatization has been an arduous challenge for housing companies and for the city in which they are located. The challenges are in particular in terms of social exclusion and discontent that constantly challenge the problems of housing and urban governance. The authors find that to try to solve these urban problems of deprivation, socioeconomic issues and stigmatization of these areas there have been implemented several strategies such as:- Physical and tenure restructuring; demolishing the old and re-building everything and changing the

forms of tenure, to create a social mix, where the different social groups interact bringing benefits for the less privileged. This strategy has been widely criticized, since it has only contributed to the gentrification of these neighbourhoods, just making them more attractive for private investment due to its profitability. The social mixing cause the rupture of existing social capital links and ignoring that people choose to be close to the people with whom they can identify. This approach is usually related to these processes that were carried out with only profitable objectives, which Swyngedouw et al. (2002) call the 'New urban policy'.

- Upgrading approach; intervention in physical improvement and maintenance, the creation of

amenities and public spaces, increasing the attractiveness of the area for middle class residents and, therefore, gentrifying it, but it is less visible in terms of physical renewal than restructuring approaches. This approach is related to the urban renewal and redevelopment, where the physical aspect is the main aim.

- The service-partnering approach; giving greater citizen participation in the decision-making of these

MHP areas, for example, the determined and constant maintenance strategy, where the tenants decided how to do it and what tasks should be prioritized. The role of local people went from being the passive user of development programs to becoming local experts. Although in theory it seemed to be a very promising approach, in practice it was very difficult to achieve concrete results, especially when it was necessary to carry out densification projects. This approach was just physically oriented as urban

development approach.

- The gradual improvement of standards and socioeconomic empowerment; seeks to empower people in

areas of low social status to participate in society in general with programs that increase information and access to certain types of services. Socio-economic empowerment and area-based approaches have been widely adopted in Sweden (see also Andersson et al., 2010); however, the effects of these efforts are difficult to measure. For those who benefit from the efforts or come to obtain a higher and safer income, they tend to leave the stigmatized area, sharpening the segregation of those who remain.

- Improvement of the image; seeks to improve the image of a stigmatized area, promoting positive

images and alternatives of it, and disseminating them through different actors. This strategy is ambivalent, because, on the one hand, the construction of images is more related to the neoliberal practices also used as an intentional policy and strategy on the part of public actors (municipality) to counteract the prejudiced images of an area, and on the other hand, there are reasons to distrust this approach, because it can distort or hide real social challenges. This approach may be related more to the 'new urban policy', product of the dominant neoliberal current.

For Parker & Madureira (2016), this range of strategies has been used due to the fact that national and local governments are interested in solving these problems in those MHP areas, but because there are certain differences in the approaches and the scales between them, the consequence is that there is no uniformity of criteria in the creation of these strategies. On the one hand, national urban and housing policies have an important role in allowing and restricting the deployment of different strategies, on the other hand, the local conditions of the housing market and the interest of local public and private housing companies also play an important role and influence the specific form of regeneration. After the variety of previously reviewed strategies, the authors suggest that the concept of legitimacy6 is lacking in most of these projects, and argue that it should be incorporated in urban regeneration projects, especially in segregated and stigmatized neighbourhoods, to have mutual and instrumental support established among the main actors; local residents, local government and developers.

i. The Bokals; projects seen as successful example within MHP areas

A short review is made about the Bokal concept and the Bokal project in Örtagårdstorget in Rosengård, Malmö as well, which some scholars recognized as successful one, due to the positive results achieved especially as a place for socialization of local residents. Boverket (2015) defines Bokal as the combination of

Bostad (residence) + lokal (local), which is the combination of residence and local (premises) for the same

person who should be able to live and work in a building.

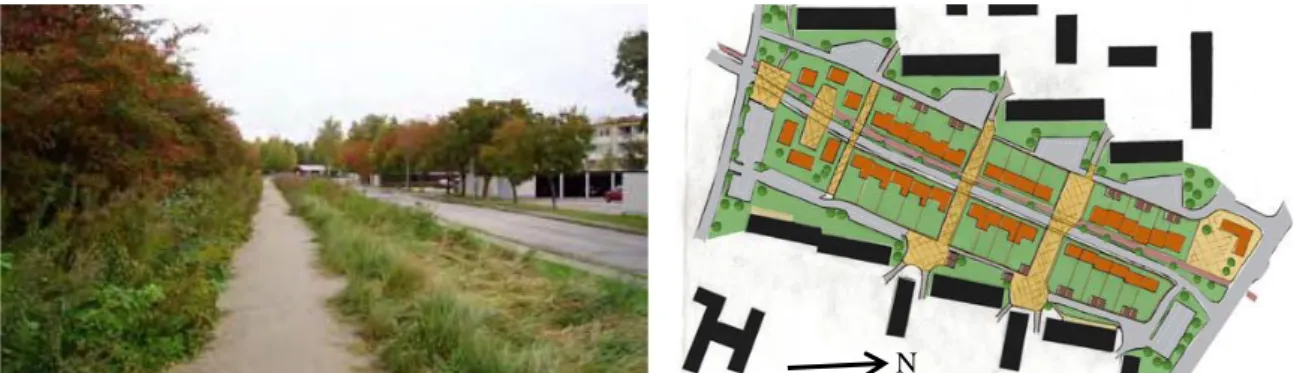

The Bokal project in Örtagårdstorget in Rosengård, Malmö (Figure 02) is a relative small and built in 2010. Parker, (2014) indicates that the project was an initiative from MKB AB - the municipality housing company of Malmö, to showcase local entrepreneurship, which both created a meeting place and indicated a direction that connects Rosengård with the city centre. The project is committed to small-scale trade with the special social conditions of the place. The development and subsequent implementation of the area helped to strengthen the social importance of the project.

The Landssekreterare (Malmö municipality, 2007) describe that the residential area is characterized by wide spaces but rarely adequate conditions for meetings and natural activities. The entrances of the buildings are oriented towards the gardens, which means that the streets and public neighbourhoods are not naturally linked to the buildings and the life that happens there. The proposed plan was to add to the existing departments of the first floor (Figure 02) a new commercial area - on one level - on the existing front gardens (Parker et al., 2012).

Existent buildings Proposed buildings

Figure 02 (left): Proposed Plan, where the new buildings (yellow ones blocks) are built separately from the old structures (light pink colour) and occupying the front gardens. Source: Malmö municipality, (2007).

Figure 03 (centre): Original situation, the housing blocks and the front gardens. Source: Malmö municipality, (2007). Figure 04 (right): The final result, after the construction of the project. Source: Parker, et al., (2012).

About the results also Parker, Delshammar, & Johansson, (2012) argue that the project has had an important effect on the adjacent public space, since it allows the residents - entrepreneurs to appropriate the space by being an active part in the physical and social configuration. The key aspects of the development of this space seem to be the relatively small scale, the close interconnection between the stores and a high level of visibility that allows mutual monitoring and connection with outer space. The institutional form of project

6

[…] legitimacy itself is a fundamentally subjective and normative concept: it exists only in the beliefs of an individual about the rightfulness of rule. It is distinct from legality, in that not all legal acts are necessarily legitimate and not all legitimate acts are necessarily legal [...], (Hurd, n.d.).

development creates an opportunity for residents - entrepreneurs who do not require much in terms of financial risk, as well as the surprising proposed architecture that functions as marketing. But there is also some criticism on this case, such as that the unregulated space is dominated by private and commercial interests, but it is evident in Bokal's case that the social and physical changes that this space generates are not only for abstract capital, but is deeply rooted in the local community that continuously exerts a certain degree of local control.

There are two main aspects in the Bokal project in Rosengård: on one hand, the project had a clear focus on the local people, giving more opportunities for some local residents to make commercial entrepreneurship activities, which will help their family's economy, and on the other hand, it led to an substantial improvement of the public space and social life of that part of the neighbourhood. Thus it makes the public place more attractive, helping to socialize people and creating a better sense of security due to the existence of social control. However, the project does not add more units of housing which could be also relevant, because the scale of the project is not enough to fill up the municipality´s vision and plans for densification of the MHP areas and the city as well. The project is complementing services that the area was lacking, and due to its small scale, the whole Rosengård would need more projects like this and located in strategic places to improve the public space and life. Nonetheless, it is still not an important proposal for densification because the area needs significate quantities of housing units.

1950´s 1960´s 1970´s 1980´s 1990´s from 2000 till Now

Post-war

Reconstruction Revitalization Renewal Redevelopment Regeneration Regeneration in recession European

context

Improving cities, housing and living standards after WWII welfare improvement community action and greater empowerment community self-help with very selective state support

emphasis on the role of community and in social aspects

Implementation of the concept of Sustainability

The concept of sustainability appeared Compact cities Urban density (Smart cities) Swedish context

Sweden did not had war but were severe shortage of housing Development of MHP areas under welfare system Development of MHP areas under welfare system Policies to maintaining the MHP areas Neoliberal processes to regenerate MHP areas

Looking for new approaches but still preserving the welfare system (Densification) And in the search of sustainability…new trends?

…and maintaining welfare system (?) Figure 05: A parallel evolution in time of the concepts on how to do urban development, between the European and Swedish contexts.

As a way of concluding the comparison of European and Swedish urban development strategies, the Figure

05 presents them in a longitudinal observation form (Gerring, 2006), from the 1950s until now, were some

clear differences between both processes can be noted.

In the European context, as a direct consequence of the WW II, the majority of the cities needed reconstruction and huge qualitative of housing improvements, giving rise to the different strategies of urban development, where also the idea of welfare had a stage (1960's) but leaving it aside soon. In the case of Sweden, the cities did not suffer the effects of the war, but due to the shortage of housing, ambitious urban development plans were also started, and also taking the concept of welfare system, but keeping it present as part of the city's governance system until now.

1.3.5 The concepts of sustainability and legitimacy

i. Sustainability

A first approximation of a definition of sustainability was made by the Bruntland Report for the World Commission on Environment and Development in 1987 as:

“Development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”. (Bruntland et al., 1987)

After this first definition there have been other ideas and strategies on how to implement them. Usually these concepts link social equity, economic and ecological concerns.

For instance Campbell (1996) suggests that the planners and designers should not work directly with these three detected issues; social equity, economy, and environmental; but in those three axes of tension (or conflicts) created by these three fundamental problems each one located in an angle of the triangle - ´planner´s triangle´. As a result of this action, sustainability tends to be located in the ´centre´ of these three tensions, but it must also be understood that this ´centre´ is quite diffuse, which means that sustainability cannot be found directly, so planners

have to redefine it all the time. Figure 06: ´The planner’s triangle´. Source: Campbell, (1996)

Another concept is given by Pope, Annandale & Morrison-Saunders (2004): they propose the assessment for

sustainability as a concept and tool to measure the processes of sustainability. For that, these processes are

based on the existent literature as models as well, providing clarification and reflecting on those different approaches described in the literature as forms of sustainability assessment, and evaluating them in terms of their potential contributions to sustainability. According the authors some of these existent examples of

‘integrated assessment’ derived from Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA)7 and Strategic Environmental

Assessment (SEA)8, where both (principle-based approach) have been extended to incorporate social, economic and environmental considerations as well, reflecting a ‘triple bottom line’ (TBL)9 approach to sustainability. These integrated assessment processes typically either seek to minimise unsustainability, or to achieve TBL objectives and according to the authors both objectives may or may not lead to a sustainable practice. Pope et al. (2004) also argue that the concept of ´sustainability´ must be very well- defined to apply to the concept of ‘assessment for sustainability’.

So there are some marked differences between those two concepts definitions: while Campbell suggests that there is no clear definition of sustainability and the focus should be in sustainable goals, Pope et al. (2004) argue that it is necessary to define clearly the concept of sustainability as a social aim – not just the goals orientation - to apply their concept of assessment for sustainability.

The concept of sustainability is still quite wide and open, but the most important thing is to be aware of this concept and in the cases of search for sustainability in the projects it is necessary make evaluations from several approaches, given by researchers and evaluates from time to time to correct or continue the chosen process. In the case of the present project research work in MHP areas it is not possible to avoid the aspect of

7

Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) is the process of examining the anticipated environmental effects of a proposed project - from consideration of environmental aspects at design stage, through consultation and preparation of an Environmental Impact Assessment Report (EIAR), evaluation of the EIAR by a competent authority, the subsequent decision as to whether the project should be permitted to proceed, encompassing public response to that decision, (Environmental Protection Agency, n.d.).

8 Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) is the process by which environmental considerations are required to be fully integrated into the preparation of Plans and Programmes prior to their final adoption. The objectives of SEA are to provide for a high level of protection of the environment and to promote sustainable development, (Environmental Protection Agency, n.d.).

9 The phrase “the triple bottom line” was first coined in 1994 by John Elkington, […]. His argument was that companies should be preparing three different (and quite separate) bottom lines. One is the traditional measure of corporate profit—the “bottom line” of the profit and loss account. The second is the bottom line of a company's “people account”—a measure in some shape or form of how socially responsible an organisation has been throughout its operations. The third is the bottom line of the company's “planet” account—a measure of how environmentally responsible it has been, (The Economist, 2009).

social sustainability and it must be incorporated as a crucial aspect of evaluation of these new approaches and strategies.

ii. Legitimacy

A general definition of legitimacy was made by Suchman (1995) as:

´a generalized perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper, or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions´. (Suchman, 1995)

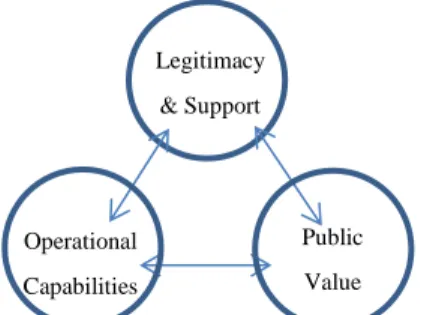

But how can legitimacy be understood in the urban realm, where the private interest usually challenges the public and common values? Moore & Khagram (2004) argue that for instance the private companies should learn from the government agencies how to create social value, because it is the way of their sustainability. Traditionally the main goal of government agencies is to create ´public [social] value´, while the goal of managers of the private sector is to create economic value. But how is the process in which the government agencies create the public value?

Through the "strategic triangle" (Figure 07) the authors show the three main and complex issues as the focus of attention of government administrators: public value; it is what the governmental organization must create, and not only its own vision, but it must also be shared by other actors, sources of legitimacy and support; are actions and provision of resources - commitments with other people and organizations that could confer legitimacy - necessary to sustain the governmental organization to create public value, and operational capabilities; are the necessary innovation, on which the government organization depends or has to develop to achieve the results (Moore & Khagram, 2004).

Figure 07: The ´Strategic triangle´. Source: Moore & Khagram, (2004).

iii. Social sustainability and legitimacy in urban regeneration projects

- Social legitimacy in urban regeneration projects

Since the concept of sustainability covers at least these three fundamental issues: social equity, economy, and environmental (Campbell, 1996), in this work it is necessary to highlight especially the social aspects in those processes of urban regeneration projects in MHP areas due to their very complex social problems. But what is the meaning of social sustainability in urban regeneration projects?

Dixon et al., (2009) state that there have been some definitions on the concept of social sustainability and there is still not one common interpretation. It is still in process and it must be included in urban regeneration that it must be an integrated vision and action that leads to the resolution of urban problems and that achieves a substantial and lasting improvement in the economic, physical, social and environmental conditions of an urban area that has suffered negative changes.

Additionally to these new concepts of social sustainability that are emerging there is also another new one that could also help a lot in the search for sustainability in such stigmatized neighbourhoods as the MHP areas in Swedish cities. This is the concept of legitimacy; which means if those processes of urban regeneration projects (public or privates) have the necessary legitimacy or not in the society to be successful and achieve the required goals.

- Legitimacy in urban regeneration projects

Moore & Khagram (2004) argue that the central argument of the concept of legitimacy is useful to understand, for example in urban development projects, the links between the administrative and the political, because in current times government institutions are losing legitimacy due to the low credibility of

Legitimacy & Support Operational Capabilities Public Value

politicians, then is the time of any organization; for-profit companies, government agencies and non-profit organizations ensure the creation of public value and increase their organizational capacities to obtain support and legitimacy for their sustainability.

Within the Swedish context, Parker & Madureira (2015) argue that the management of legitimacy as a "credible agent of change" would be crucial in the processes of urban regeneration in stigmatized and socially segregated areas. They argue that project management actions within this context of MHP areas can be better understood by including considerations of legitimacy, because many of the strategies that have been used have limitations and produce important consequences (for example, gentrification) for residents in that area. So the crucial role of management is to mediate with all stakeholders, connecting public, private and resident interests and playing a fundamental role in the configuration of neighbourhood regeneration, placing the administration itself as a credible actor in the process, generating a cumulative process that attracts investments from the public and private sectors.

Finally it is necessary to highlight that the project managers, public and private, have to manage the projects in order to gain the legitimacy especially from the local residents’ side; from the individuals as well as from local organizations. This is the real main challenge of all those projects located in those socio-economic vulnerable urban areas as MHP.

1.3.6 Summarizing the previous research

The problems of segregation have been present since the construction of the MHP projects and the apparent problem was the deficient planning and design processes in the links between these new neighbourhoods and the old city. The solutions which have been used before was not to attract more quantities of people in the area, but mixing people from different social strata and complementing with more public infrastructure for socialization and commercial areas, but not constructing more housing units or densifying the area.

The challenge for Sweden now is to generate or re-generate more sustainable cities and neighbourhoods, especially on those stigmatized MHP areas, while still maintaining the features of the welfare system10 while in other European countries the urban politics are ruled more under the neo-liberalism system11. In this sense, the situation of the MHP areas is contradictory; because the welfare policy should be an advantage in aspects of social sustainability especially for local residents, but nevertheless it seems that the urban development or the densification strategies programs that have been carried out in the MHP areas still lack in some crucial aspects to really achieve important advances in the search for the sustainability of those areas.

1.4 Aims of the study

The aim of the study is to find out if those selected new projects of densification built or in planning process within MHP areas considered ´better practices´ are sustainable according to the current theoretical definitions and based on the classical three pillars of sustainability: Social, economic and the built environment aspects.

Moreover, the aim is to prove if those new approaches of urban densification projects are more effective in the search for sustainability - especially in the social and in the built environment aspects – and are going to achieve important grades of success.

10

Welfare state, concept of government in which the state or a well-established network of social institutions plays a key role in the protection and promotion of the economic and social well-being of citizens. It is based on the principles of equality of opportunity, equitable distribution of wealth, and public responsibility for those unable to avail themselves of the minimal provisions for a good life. The general term may cover a variety of forms of economic and social organization […], (Encyclopaedia Britannica, n.d.).

11 Neoliberalism, ideology and policy model that emphasizes the value of free market competition. Although there is considerable debate as to the defining features of neoliberal thought and practice, it is most commonly associated with laissez-faire economics. In particular, neoliberalism is often characterized in terms of its belief in sustained economic growth as the means to achieve human progress, its confidence in free markets as the most-efficient allocation of resources, its emphasis on minimal state intervention in economic and social affairs, and its commitment to the freedom of trade and capital […], (Encyclopaedia Britannica, n.d.).

1.5 Objectives of the study

To make a revision of theories about good practices and sustainability of urban regeneration or densification projects, specifically in social - economic vulnerable urban areas.

To collect information (printed, drawn and recorded in other kind of formats) produced by the municipal authorities as well as by project managers and also information contained in the press and social media about the initial ideas of these new approaches in the design stage of the projects and make a comparison with the already constructed projects, to understand how the main ideas of sustainability were evolving or not, along the time.

1.6 Outcomes of the study

To contribute with more information, research and understanding of the problems within those built environment areas in vulnerable social-economic situations (the Million Homes Programme areas) in Swedish cities.

To clarify which are the better practices carried out previously and which are the most important new concepts that are being handled for the execution of densification projects in order to generate the necessary discussion in the academic field and in practice.

The conclusions and recommendations obtained at the end of the investigation can serve as basic guidelines for public and private agencies in the search for more sustainable urban densification projects in these social-economic vulnerable built environments, generating more benefits for residents and local organizations, which will ensure the social legitimacy of these new projects.

Finally, also new questions and new research topics will emerge throughout the process of the work, and to identify them clearly is necessary for further studies.

1.7 Method

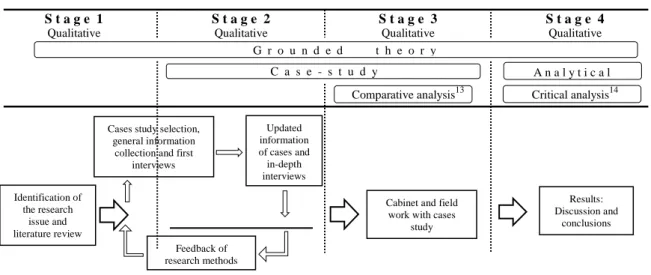

Due to the characteristics of the subject of study, it is necessary that the research and analysis processes have to be based in qualitative methodologies approaches or flexible design12 (Robson, 2011); being the

considered methodological approaches the Grounded theory research, known also as Constant comparative

method, (Groat & Wang, 2013) and the Case-study methodology (Gerring, 2006; Robson, 2011; Yin, 2017).

The grounded theory is used in the first chapter of the work, to collect qualitative information. While

grounded theory and case-study method are used in the second, third and the fourth chapters, making also comparative and critical analysis to the obtained results; in the fifth chapter are presented the conclusions,

recommendations and probably subjects for future research.

1.8 Layout of the document

The work is presented in five chapters following the

IMRAD format -

Introduction, Materials and Methods,Results and Discussion, (Nair & Nair, 2014). In the first chapter there are the introduction, the research

questions, aims and definition of the problem; where it is explained why the issue is relevant and the goals

and aims to achieve, and supported for a wide national and international theoretical definitions background about the subject. In the second chapter there is the explanation about the flexible design methodologies used

12

Flexible designs: […] referring to ´flexible´ rather than the more usual ´qualitative´ research design. […] concentrates on three

in the work; which are the grounded theory (Groat & Wang, 2013) and the case- study research methodology, (Gerring, 2006; Robson, 2011; Yin, 2017), in this chapter six cases are chosen located in MHP areas in Malmö and Växjö, and a comparative analysis is made within their cities context. The third chapter is to find out the results; for that a critical analysis is made between the six cases; finding that there are two cases some could be catalogued as better practices due to their compromise with the social aspects of the locals. At the end of this chapter a more deep critical analysis is made between these two chosen cases. The fourth chapter discusses the theory of the relationship between the urban form related to sustainability, also on the incorporation of the concepts of legitimacy and social sustainability in practice, and the discussion ends with the findings of the analysis of the specific cases carried out, and finally in the fifth chapter, the final conclusions, recommendations and some suggestions for probable future investigations are presented.