Global Political Studies Peace and Conflict Studies Bachelor Thesis

Fall semester 2011

Tahrir Sq.

Location

and Goal

On Changes in the Liberal Political

Discourse in Post-Revolution Egypt

Isaac Heinrich

Supervised by: Dr. Ane M. Kirkegaard Words: 16,422

Keywords: Tahrir Square, the Arab Spring, Liberalism, Egypt, Egyptian revolution, MENA, discourse analysis, opinion articles, op-eds

ABSTRACT

Liberal Arab thought has long been fighting for elbow room in the political discourse in Egypt. The ruling nationalist–statist ideology from Nasser to Mubarak is renown for its repression of political dissidents, and the Islamist opposition often side with the ruling elite in its resistance against liberal reformers and democratization. Political liberalism is associated with a host of professional and personal risks and many are silenced. The Arab Spring revolutions across the MENA from December 2010 throughout the spring of 2011, however, seem to have revived the interest for liberal ideas in the Arab world.

This thesis investigates the impact of the Arab Spring on the liberal Arab discourse in Egypt. It asks whether the revolution has lead to increased opportunities for liberal Arabs to voice their opinions, and how the tone of the public debate has been affected. A discourse analytical research method is used to scrutinize thirty opinion pieces from two major Egyptian newspapers in the timeframe November 2010–September 2011, on eight sample days. The work also considers 115 articles published after the revolution on the sample days to monitor the impact of the events on the public debate quantitatively.

The study finds that the most salient feature after February 2011 in the op-ed material examined is the forming of the “Tahrir Square discourse,” a symbolically charged ideational entity that associates itself with liberal political rhetoric and values. It is a major influence during the stated period affecting 77% of the 115 post-revolution articles. The Tahrir Square discourse is an expression of a more permissive climate for voicing liberal and reform-friendly opinions, the thesis concludes. The empirical material exhibits more profuse mentioning of and advocacy for these values after the revolution. The tenor and rhetorical mode vary greatly in the studied articles; despite this, a broad support for the revolution itself is present. The study, however, is reluctant as to the permanence of these changes.

List of Abbreviations

FJP Freedom and Justice Party (MB) MB Muslim Brotherhood

MENA Middle East and North Africa NP National Party

Table of Contents

Introduction 1

1.1. Context 1

1.2. Problem Formulation 2

1.3. Objective and Purpose Statement 3

1.4. Research Questions 3

1.5. Why Egypt? 3

1.6. Outline of Thesis 4

Background 5

2.1. Statism and Islamism in the Case of Egypt 5

2.2. Who the Liberal Arabs Are and What They Want 7

2.3. The Liberal Arab Predicament 8

A Discourse Analytical Approach 10

3.1. General Orientation 10

3.1.1.!Discourse, Knowledge and Power! 12

3.2. Theoretical Tools 13

3.2.1.!Intertextuality and Interdiscursivity! 13

3.2.2.!Styles: Tenor and Rhetorical Mode! 14

Method and Data Selection 15

4.1. Methodological Considerations 15

4.1.1.!Chickens and Eggs: a Self-Evaluation! 15

4.1.2.!Technical Difficulties and Solutions! 16

4.1.3. !Literature Critique! 17

4.2. Procedural Features of the Study 18

4.2.1.!Data Collection! 18

4.2.2.!Sampling the Timeframe! 18

4.2.3.!Data Indexing! 19

4.2.4.!Further Delimitations! 19

4.2.5.!Delimited Sample versus Complete Sample Inquiries! 20

Analysis 21

5.1. Before Tahrir Square 21

5.2. The Liberal Infusion and the Birth of the Tahrir Square Discourse 24

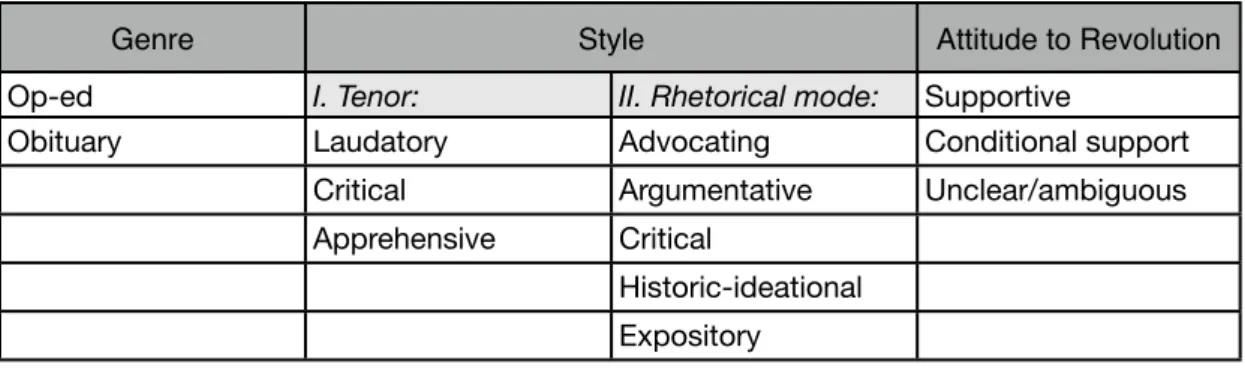

5.3. Qualitative Aspects: Analytical Categories 26

5.4. The Yes-Men 27

5.4.1.!The Revering! 27

5.4.2.!The Liberal Reformers! 29

5.5. The Critics 31

5.5.1.!On the Political Immaturity of Egyptians! 31

5.5.2.!Fearing Religious Extremism! 34

5.5.3.!Security Concerns, the Economy and Losing Sight of Revolution Goals! 36

Discussion 38

Chapter 1:

Introduction

1.1. ContextA year has passed since those defining moments around the turn of 2010 when the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region was set in motion by a series of popular uprisings that spread like wildfire across the region. It was an unchartered and erratic trip for greater political participation and improved civil rights, fueled by the grievances of populations in more than a dozen countries rising almost at once against their governments. The “Arab Spring,” as it is commonly known, was provoked by the somewhat arbitrary event of a Tunisian street vendor and graduate student, Mohamed Bouazizi, who in protest against the dire sociopolitical conditions in his country set himself on fire on December 17, 2010 (Reuters Dec 19, 2010). The act caused a heavy stir in Tunisia, a country not famous for its many political protests (The Guardian Dec 29, 2010), and produced a number of copycat suicide protests in more than eight other countries in the MENA region (BBC Jan 23, 2011; The Guardian Jan 16 & Jan 17, 2011; Haaretz Feb 13, 2011; WikiLeaks Jan 19 & 24 2011). The protests spread rampantly across the region1.

Despite this rather morbid beginning, Arab Spring protests were otherwise largely nonviolent. The main grievances behind the uprisings varied locally, but included public discontent with governance issues, high level of corruption and human rights abuse, along with reactions to the dire socioeconomic situation in the region, such as lacking housing and basic services, rising inflation and food prices, scarce work opportunities and poor working conditions (The Guardian Dec 29, 2010; Jan 7 & 16, 2011; The Washington Post Feb 12 & 25, 2011). In many ways, the protests can be regarded as the return of liberal ideas to the MENA. In Egypt, the demonstrations rallied protesters in the millions. Tahrir Square alone, the central square in Cairo, accommodated more than a million people for several consecutive days at the end of January (Al Jazeera English Feb 1, 2011 a&b), briefly erupting in hostilities on February 2 between protesters and pro-Mubarak

1 Starting with insurgencies in Tunis in mid-December 2010 it was shortly followed, in chronological order, by: Algeria (Jan 6-7), Jordan (Jan 14/28), Yemen (Jan 23/27), Saudi Arabia (Jan 23/end of Feb), Egypt (Jan 25), Lebanon (Jan 25), Oman (Jan 27), Palestine (Jan 28), Iraq (Feb 12), Bahrain (Feb 14), Iran (Feb 14), Libya (Feb 15), and Morocco (20 Feb), Syria (Mar 15) (for an interactive overview, see The Guardian Nov 18, 2011; supporting articles Al Jazeera

English Jan 14, Feb 22 & Nov 20, 2011; BBC Jan 23, 2011; The Washington Post Feb 12, 2011). For difficulties

attending rapid and widespread social upheaval, precise starting points (indicated in parentheses above) are hard to determine; dates are tentative and based on when revolts first made headlines in the mentioned sources.

supporters and security forces (ibid. Feb 2), but peaceful protests resumed shortly thereafter. Sit-ins and peaceful marches were regularly conducted across Egyptian provinces and main cities for several weeks through January and February 2011. The chief demands of Egyptian demonstrators were the step down of President Mubarak and the abolishment of Emergency Law, which had granted the administration extensive powers to strike down on political dissidents and restrict civil rights since 1981.

The results of the Arab Spring resounds to date as we have not yet seen the end of the revolutions across the MENA. The toll on local governments, however, can already be somewhat tentatively established: political concessions in Algeria, Jordan, Morocco, Oman (Al Jazeera English Feb 22, 23 & Apr 16, 2011), strike-down against protesters and curfews imposed in Iraq (The Washington Post Feb 25, 2011), regime shift and civil war between government troops and insurgents backed by NATO in Libya ending with the killing of Muammar Gaddafi in October(Al Jazeera English Oct 21 & 25, 2011). By-elections were held in Bahrain, Tunisia, Yemen and Egypt. Bahrain announced a second round of by-elections on October 1 due to low voter turnout, Tunisia’s final election results were announced on November 14 (Al Jazeera English Nov 14, 2011), and Yemen’s President Saleh announced his resignation on November 24 (ibid. Nov 24, 2011); Mubarak resigned on February 11 and extra parliamentary elections were held in Egypt from November 28, 2011, to January 11, 2012.The Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) has governed in the interim period. Syria is most likely the next scene for violent Arab Spring offshoots, currently faltering, as it were, between insurgency and civil war.

As a life-altering and cross-polity social event in the making, the Arab Spring remains to be fully mapped out, investigated and scrutinized in academia. The absence of published scholarly works may be noted even in the reliance on news media sources for this short introduction. This study, although small in scope, will employ a discourse analytical approach to assess the impact of the Arab Spring on mainstream news media in Egypt in a modest attempt to remedy this blind spot, and contribute to what will doubtlessly consume political and social researchers for years to come.

1.2. Problem Formulation

Arab liberal influence in MENA politics has long been a “virtual footnote in the ongoing Middle East discourse” (Rubin 2006:11). This is partly due to the hegemonic rule of Arab nationalist and competing Islamist schools of thought. This ideological struggle has left its mark on regional politics and perhaps more so than elsewhere in Egypt. Nationalists and Islamists have a broader supporter base, stronger social ties and acceptance on the ground (Islamists are particularly

populist), and control large media networks and political and ideological fora, notably in the case of nationalists, the national education system (ibid. 41). Arab liberals have limited access to these platforms and therefore face significant challenges voicing their opinions, not to mention the risks to personal safety and livelihood for such political engagement. Egypt has a bleak record of human rights abuse and is known for its repression of political activism (Amnesty International 2011). This is not to say that the work of Arab liberals is insignificant: both politically and academically, liberal Arab ideas have been much circulated in international press and scholarly works, although mainly in English-language publications.

The efforts of Arab liberals in the MENA remains to be investigated, and particularly in the context of the Arab Spring. This study will focus on the injection of liberal ideas in the political debate as a result of the revolutions. It asks whether the popular revolt finds its counterpart in a more permissive and open debate in the media. Has the ban on liberal political ideas been lifted?

1.3. Objective and Purpose Statement

By studying the political debate in two leading Egyptian newspapers (one governmental and one independent), I attempt to discern how the political discourse in staff written or unsolicited opinion articles, or op-eds, have been affected by the Tahrir Square revolution.

The broader purpose of the study is to assess whether the Arab Spring poses a real paradigm shift in the political life (and how political discourse is being carried out) in Egypt beyond the symbolical and, perhaps, cosmetic. Does Tahrir Square mark the dawn of liberal Arab thought in Egypt, or does it, reversely, signal the fallback of the state to the benefit of military-statist or Islamist rulers?

1.4. Research Questions

1. Has the Arab Spring led to increased opportunities for Egyptian liberals to voice their opinions and for liberal political ideas to be debated in Egyptian media?

2. What change, if any, can be noted in the content and tone of the political messages that are being voiced?

1.5. Why Egypt?

Egypt has a prominent position with respect to Arab liberal thought. Among the twelve notable Arab liberals that Barry Rubin mentions in the opening chapter of The Long War for Freedom, nine

are Egyptians (2006). Historically, it was the first Arab country2 to introduce in the 1820s-30s the

government printing press publishing the first Arabic-language newspapers, and forming language and military officers’ training schools fashioned on European-style academies (Cleveland & Bunton 2009:67-8). The purpose of these faculties was to train a new generation of Egyptian Arabs from all levels in society in the European sciences and technologies that had proven so successful, especially in warfare. At the turn of the nineteenthcentury, the press had become the primary medium for political opinion and a host of newspapers of different political coloring had been established (ibid. 107, 109).

In modern times, Egyptian media has become one of the MENA region’s most influential: its newspapers are the most widely circulated, Egypt is a major player in the film and entertainment industry, and it was likewise the first Arab nation to have its own TV satellite, Nilesat (BBC May 6, 2011). Journalistic freedom is also among the most liberal by regional standards (ibid.). This is seen in the surge in recent years (2000s) of independent press, starting with al-Masry al-Youm and followed by newspapers like Al-Shorouk and al-Tahrir, and widespread use of the internet (Oxford Business Group 2010:183; Freedom House 2007). Considering the relative freedom of Egyptian media compared those of countries of similar political background in the MENA, that is, Syria and Iraq, and the ease of political transition during the Arab Spring, again as opposed to its counterparts, Egypt rises in relevance as a suitable focus for this particular inquiry.

1.6. Outline of Thesis

In this chapter, the general background and research problem has been presented. In Chapter 2 next, the Egyptian political setting is dealt with, and I define Arab liberalism, its ambitions and challenges. In Chapter 3, the discourse analytical approach will be presented along with the theoretical tools relevant to this study. Chapter 4 deals with the exigencies of data collection and delimitation, and considers some important methodological difficulties. We will then turn to the analysis in Chapter 5, the results of which are discussed in Chapter 6. Finally, Chapter 7 summarizes and concludes the study.

2 I here, right or wrong, disregard similar contemporary developments in the Ottoman Empire that, although belonging to the same religious-cultural and geographical continuity, followed a distinctly Turkish–ethical trajectory beginning with the Young Turks and Kemal Atatürk in the early 1900s.

Chapter 2:

Background

To grasp the state of contemporary Arab liberalism we need to inspect it from different angles. This chapter has been divided into three main sections; the first provides the sociopolitical setting in which Arab liberals have lived and acted in recent time, the second defines the term and stated ambitions of “Arab liberalism” as intended in this work, and the last with existing difficulties and risks connected to liberal political commitment in the Arab world.

2.1. Statism and Islamism in the Case of Egypt

Liberal thought in the Arab countries has long been struggling against a hard countercurrent, stuck, as it were, between statist and Islamist ideologies. In most Arab countries throughout the 1950-60s, Arab socialism in the form of Nasserism and Baathism, commonly associated with a statist and stout Arab-nationalistic stance, came to dominate the political life in many MENA countries, notably Egypt, Syria, and Iraq3. Following the 1952 Egyptian Revolution, Nasser developed the

Arab Socialist Union which quickly became a dominant single-party system with a hefty bureaucracy employing some five million workers by the late 1960s (Cleveland & Bunton 2009:318). In Syria and Iraq, Baathist one-party rule was institutionalized by Hafiz al-Asad in 1963 and Hasan al-Bakr in 1968/1977 respectively (Saddam Hussein was still second in command at the time; ibid. 399, 409-410). The short-lived union between Syria and Egypt – the 1958-61 United Arab Republic – was an early but rather unsuccessful attempt at pan-Arabism in practice. It failed because of Syrian disenchantment with Nasserist Egypt dominating the politics of the union, and rather than treating Syria as a partner quickly imposed the same single-party military regime on the country as it had vis-à-vis its fellow Egyptians (ibid. 314, 326; Cantori & Baynard 2002:351). Despite this, statism, socialism and Arab nationalism has become deeply embedded in the way that these states logically function and reason, from their education systems, intellectual culture, to government rhetoric (cf. Choueiri 2000, Groiss & CMIP 2001, Rubin 2006, Stacher 2001).

3 Arab nationalism had begun as an ideological movement over a century earlier with Arab literary clubs and scientific societies emerging from within the Ottoman empire in Lebanon and Syria (Cleveland & Bunton 2009:130).

Interestingly, nationalism went hand in hand with a liberal–scientific orientation at this point. The forming of the Young Arab Society, al-Fat!a (1880-1984), is an epitome of this influence. Again in the 1940s-50s, Syria became the arena for Arab-nationalistic enterprise with the founding in 1946 of the Arab Baath Party by Michel Aflaq and Salah ad-Din al-Bitar. The influence of Baathism on the more recent Nasserism is well-established (ibid. 325-326).

Throughout the 1960s–80s, Rutherford writes, the prevailing state ideology in Egypt was a “sweeping conception of statism that created a vast and pervasive state apparatus” (2008:131). This created a highly centralized statist regime that controlled the economy, polity and society, and in which political rivals were outlawed (ibid. 132).

During the 1970s, Anwar Sadat partly abandoned the government-instituted Arab socialism and set out on an economic and political reform program. It involved opening up to Western aid and investment, decentralization of government, and a move away from the centrally planned economy (Cantori & Baynard 2002:355). After the lost October War of 1973 it likewise meant reconciliation with Israel, culminating in the 1979 Egypt–Israel Peace Treaty (ibid.). For ordinary citizens, however, this move towards economic liberalization seems to have had little effect toward improved living standards. This caused in a renewed popular interest in Islamic principles of justice and social order (Cleveland & Bunton 2009:382). The Muslim Brotherhood (MB) grew considerably through recruitment from the student body of universities around the country and some more radical organizations developed simultaneously (ibid.). By 1980, confessional conflict between Christian Copts and militant Islamists had erupted throughout the country, and the years 1980–81 were marked by increasing political violence (Cantori & Baynard 2002:355). In an attempt to curb the uprisings, Sadat’s government struck down hard on the assailants and ordained severe countermeasures against persons from a broad range of different political backgrounds. Newspapers were closed, some political parties and religious groups were banned, and between 1,000-1,500 individuals (numbers diverge, cf. ibid 356; Cleveland & Bunton 2009:382) were arrested in one month, September 1981, alone.

Following Sadat’s assassination on October 6 the same year, Emergency Law – one of two primary grievances voiced at Tahrir Square – was imposed. It has not been lifted entirely, even with the resignation in February 2011 of Hosni Mubarak, Sadat’s vice president and presidential successor. From 1984, repression of the political opposition augmented and elections became ridden with intimidations and fraud – the “hallmark of elections under the Mubarak regime” (The Guardian Nov 30, 2011). “These were not new practices in post-1952 Egypt, but their use by a regime that had no purpose other than to stay in power and by a president who inspired little popular confidence served only to alienate the public,” Cleveland & Bunton write (2009:393).

Throughout the regime of Mubarak, Emergency Law has existed as an instrument for the government to strike down on political dissidents. At the turn of 2010, the record was persistently bleak despite a May 2010 presidential decree to limit its application. Political prisoners in the thousands were still in administrative detention, torture in police stations, prisons and detention

centers described as “systematic” and generally committed with impunity, and suppression of freedom of expression and state censorship was widespread (Amnesty International 2011:131-4). For this reason, Islamism has only gained in public appeal in Egypt since the decline of Arab nationalism at the end of the 1970s. The officially banned, but overtly operating and broadly supported MB is a telltale example of this.It is therefore perhaps unsurprising that religion has been described as “the only uncensored public expression in most Arab countries” (Ghabra 2004 in Rubin 2006:32). Islamists, furthermore, are often accused by liberals of playing into the hands of ruling regimes by opposing liberal democracy and thereby keeping the system’s goals intact (ibid. 57). The recently concluded (January 2012) Egyptian by-elections – a direct outcome of the popular Arab Spring revolution – turned out a massive victory for Islamist parties, the MB’s Freedom and Justice Party (FJP) winning 47.2% and the ultraconservative runner-up al-Nour, an even more fiercely Islamist party, secured 24.3% (BBC Jan 21, 2012). Islamists have likewise been successful in post-revolution elections in Morocco and Tunisia this fall (The Guardian Nov 30, 2011). This outcome strengthens the argument that Islamism is a force to be reckoned with in the Arab world.

Despite the recurring periods of turmoil over the past thirty years and the sometimes strenuous dynamics between statism and militant political Islam, Cantori & Baynard note that, “Egyptian political culture […] has remained relatively constant” (2002:357). We will next turn to define the role and ambitions of Arab liberalism in the MENA.

2.2. Who the Liberal Arabs Are and What They Want

In this work, the word “liberal” and “Arab liberalism” is related to classical social liberalism. As Bruce K. Rutherford explains, “Egypt’s liberal tradition incorporates the core principles of classical liberalism: a clear and unbiased legal code, the division of state powers into separate branches, checks and balances among these branches, and respect for basic civil and political rights” (2008:32). The political implications of this position are many, as Barry Rubin, in his book The Long War for Freedom, exemplifies:

This book defines [liberal Arabs] as people who support one or more of the following concepts: multiparty elections, parliamentary democracy, human rights, women’s rights, a more tolerant interpretation of Islam, rapprochement with the West, and peace with Israel […] [It] may also include additional ideas such as the diversification of the economy, a higher emphasis on toleration of other cultures, and opposition to terrorism in principle. (2006:3-4)

Given that this definition is broad-brushed and perhaps lacks a bit of analytical clarity as a result, it is nevertheless this encompassing but distinct “entity,” or discourse, I am interested in. The reader

should therefore note that what is designated has less to do with party politics or the particular voice of any one school of thought, but with a cluster of ideas expressed by different actors. One condition is of course that we disregard the “dishonest liberalism” of regimes who only pay lip service to democracy and human rights to veil de facto authoritarianism, so common for the MENA (ibid. 4; Schnabel 2003:36).

So what do liberal Arabs want? As just mentioned, I have associated liberal Arabs with the pursuit for improved civil rights and freedoms. Increased political participation by members of society together with transparency and accountability in electoral affaires and political processes logically follow this position. This, however, is no piecemeal undertaking in countries were the implementation of democracy and human rights, despite their enshrinement in constitutions and legal codes, are “often neglected and, in some cases, deliberately disregarded” (UNDP 2002:2 qt. in Schnabel 2003:34). In many Arab countries, democratization is systematically de-prioritized for security reasons (Rubin 2006:62; Abu Jaber 2003:132); Arab states many times exhibit amazing regime stability. This is true for Ben Ali’s Tunisia, Gaddafi’s Libya, Mubarak’s Egypt, al-Asad’s Syria, the Hashemite Jordan and, prior to his deposal, Saddam Hussein’s Iraq. As Albrecht & Schlumberger somewhat punningly remark: “What we should investigate is therefore not the ‘failure’ of democracy, but the ‘success’ of authoritarianism in the Middle East and North Africa” (2004:373). We may therefore easily appreciate that what Arab liberals actually impose on their governments and societies is nothing short of revolutionary:

After all, the main changes the reformers advocate involve abandoning the ruling doctrine and ending the regime’s educational-cultural monopoly (which validates the existing intellectual elite); reducing high military spending (which keeps the armed forces happy); breaking up the statist economy (which enriches the regime and its followers); putting corrupt civil servants and human rights violators in jail while firing the incompetent (thus threatening the government bureaucracy); and holding fair elections (which will throw the current rulers and political elite out of power). (Rubin 2006:45)

2.3. The Liberal Arab Predicament

Political activism in Egypt comes with a hefty price tag and particularly so when the values one maintains run counter to state ideology. Liberals who openly champion their ideas are admittedly few, in part due to the dramatic consequences of such political engagement: “Arab liberals are indeed under siege, and that’s putting it mildly. [They are] fighting to retain the last foothold that liberal values still have in the Arab world” (Abdulhamid in The Daily Star Aug 31, 2004 qt. in Rubin 2006:8). The Egyptian Government is known for its intimidations and reprimands against

journalists and bloggers (Oxford Business Group 2010:184; Amnesty International 2011), and even after the political transition in 2011, several individuals have been litigated, fined and/or imprisoned on defamation charges and/or for disturbing peace and security (Reporters Without Borders, Sep 10 & Nov 16, 2011).

Those that do not succumb to the fear of summary arrests, and mistreatment and physical abuse while in penal custody additionally have to face the dilemma of just getting one’s point through. Arguably, nationalists and Islamists have far more followers and have been vastly more successful in dominating the political discourse through the various information channels they control (Rubin 2006:11). Moreover, threats to one’s safety, career and livelihood, and the safety, careers and livelihoods of friends, associates, and family is not a negligible influence. Smear campaigns are often launched against liberal reformers, and people have been barred from working and expelled from professional organizations (Rubin 2006:55, 61). The “central pillar of the system,” according to Rubin (ibid. 45), is the use of conspiracy theories: “Xenophobia has always been one of the Arab regimes’ most valuable tools, with the anti-America and anti-Israel cards as the aces in their hands. In the Arab world, patriotism is the first refuge of scoundrels, who defend their privileges by denouncing reformers as traitors” (ibid. 62; cf. Groiss 2001, Heinrich 2011:32-34).

Consequently, Arab liberals are often silenced (threatened, defamed or simply not published) due to lack of political mandate and exclusion from different communication channels. It remains a fact that most of Egypt’s five-hundred or so newspapers and magazines are controlled by the government (Oxford Business Group 2010:183). While the surge of new and critical independent newspapers after the 2003 launch of Al-Masry Al-Youm itself is a sign of improved conditions for Egyptian publishers, editorial and journalistic self-censorship remains a great obstacle to free political expression (Grant 2008).Similarly, Egyptian media (television, internet) and the academic world remain largely unaffected by liberals. One way to evade domestic repression and censorship is publish one’s work abroad, generally in English-language journalistic and academic literature. This however aggravates the scarcity of liberal historical and ideological works available to a predominantly Arabic-speaking-only public (ibid. 39).

Others, still, have paid the highest price for their ideals. Incidents of disappearances, deaths in custody and death penalties against political dissidents have been commonplace throughout Mubarak’s regime (Amnesty International 2011:131-4).

Chapter 3:

A Discourse Analytical Approach

Discourse analysis is a methodological and theoretical approach to social analysis that has been developed intensely over the past forty years. In its modern form, it is commonly attributed to Michel Foucault (e.g. Fairclough 2006:37; Phillips & Jørgensen 2006:12; and Garrity 2010). This chapter builds on the work of recent protagonists like Norman Fairclough, James Paul Gee and Phillips & Jørgensen. For reasons associated with the closeness of theory and method in discourse analysis, they will here be described conjointly, whereas the methodological concerns particular for this study will be dealt in the next chapter (“Method and Data Collection”). First, I will provide a general orientation to discourse analysis and then review the analytical tools of the approach relevant to this study.

3.1. General Orientation

Discourse analysis, simply put, is the study of “language-in-use” (Gee 2011:8). Rather than representing a particular theory or methodological approach, it is a theoretical stance based on a set of ontological and epistemological claims related to social constructivism. “Discourse analysis is just one among several social constructionist approaches but it is one of the most widely used approaches within social constructionism” (Phillips & Jørgensen 2006:4; cf. Weiss & Wodak 2003:12). Discourse analysis recognizes that language use is a social practice with substantial implications for how the world is and can be perceived. To understand why, we need to look at how discourse analysis conceives the term “discourse.” The notion is used quite differently in different academic cultures. Between Habermas definition of discourse which focusses on communication and intersubjectivity and Foucault’s archeological description of the term which ponders how it is possible to meaningfully talk about anything at all, there is a gulf to traverse, as Garrety (2010:194) points out.

Fairclough, whose work is guiding in this study, applies the term in three different ways. In the most abstract sense, he defines discourse as “language use as a social practice” (Phillips & Jørgensen 2002:66). Discourse analysts view language as mutually constituted of information, action and identity (Gee 2011:2). When we express ourselves on a topic, the act of speaking has an

intended audience and a message that aims to achieve some kind of result or action. Moreover, the things we say and do by saying them to a varying degree involve the enactment of identity. These identities are embedded in the language used to transmit them. The focus on performance and other physical, emotional or cognitive implications of language, and how social realities in turn affect the choice of possible topics and the language used to reflect on or modify these realities, makes the social practice definition meaningful. Secondly, discourse is the “kind of language used within a specific field” (Phillips & Jørgensen 2002:66), like politics, the media or everyday conversations. Each field carries within a certain “lingo” and a way of representing and enacting a certain role or identity. The terminology and tone of a physician or a layperson discussing public health is quite different, as is speech addressed to a child from that addressed to adults, official correspondence as opposed to private conversations, PR buzz talk, chat language, and so on. The potential for specialized forms of language, so-called social languages (Gee 2011:28) or genres (Fairclough 2006:126-7), are almost infinite.

The third and most concrete definition of discourse is “a way of speaking which gives meaning to experiences from a particular perspective” (Phillips & Jørgensen 2002:67). Consider Gee’s definition:

I use the term “Discourse”… for ways of combining and integrating language, actions, interactions, ways of thinking, believing, valuing, and using various symbols, tools, and objects to enact a particular sort of socially recognizable identity. (2011:29)

Being a lawyer, for example, presumes not only a way of speaking, but to a way of dressing, composing oneself and a palette of attributes and attitudes. Showing up for work in baggy pants and a baseball cap would certainly raise a few eyebrows, indicating how easily social roles can be transgressed. Fairclough proposes that discourses have three key elements: the identity, relational and ideational function (Phillips & Jørgensen 2002:67). In addition to indicating the role and identity of the elicitor, language defines social relations. The same person may be addressed “Mr. Cane,” “Robert,” “Bobby,” “dad” and “honey” depending on the relation one maintains with the designee. Moreover, wording, tone and attitude to that which is expressed may point to sets of values and beliefs shared or contested by the speaker and his or her intended audience, again defining the relationship between the producer and consumer of the information. More fundamentally, all language usage is linked to systems of human knowledge and meaning, the ideational element. To meaningfully state any claim – and here I wish anew to draw the reader’s attention to Foucault’s archaeology – the things we say or write need to be consistent with socially agreed upon perceptions of reality, that is, they need to be built on shared experiences, whether

facts, phenomena or values, that resound with the expectations of the recipient to make sense. In this way, all statements contain elements of historically antecedent statements and knowledge that is itself enmeshed in and “stored” as contemporary discourses. This is referred to as intertextuality (Fairclough 1996:102), where “text” from a discourse analytical perspective is taken to mean any form of written or spoken language, or mix thereof. Both in the case of text production and consumption, that is, interpretation, the sociocognitive processes that are in play are largely unconscious and automatic (ibid. 80). Discourse analysis acknowledges and stresses that discourses are evolving and transient (even the most persistent [mis]perceptions, e.g. that the earth is flat, do change over time). As such, discourse is an important form of social practice that both reproduces and changes knowledge, identities and social relations over time (ibid.).

3.1.1. Discourse, Knowledge and Power

Having outlined some fundamental ontological claims of discourse analysis, we will now look at the epistemological implications in the case of social research on power. Discourse analysis and social constructivism enshrine the trinity of language (discourse), knowledge and power; they are interested in the ways discursive practices reproduce existing relations of knowledge and power (Weiss & Wodak 2003:12-15). The postmodernist venture, of which constructivism and poststructuralism are part, is adamant in its critique against the empirical positivism of Enlightenment scientific inquiry (Mouffe 2005:13). The ethical knowledge, or knowledge emanating from the ethos (self), it professes is counterintuitive to the scientific–epistemic knowledge created by positivism (ibid. 14). It assumes a “fundamental unity of thought, language and the world” (ibid. 17). This critique of rationality suggests that knowledge is historically and socially situated and opens up for research into the hermeneutical, ideational, and discursive. Knowledge, by this token, is subjective rather that objective, because, “knowledge and representations of the world are not reflections of the reality ‘out there,’ but rather are products of our ways of categorizing the world” (Phillips & Jørgensen 2002:5). Discourse analysis thus takes a particular interest in the relationship between language and knowledge, and how this knowledge is embedded in, and used to reinforce, manipulate or challenge existing distributions of power.

Power is about relations of difference, and particularly about the effects of differences in social structures. The constant unity of language and other social matters ensures that language is entwined in social power in a number of ways: language indexes power, expresses power, is involved where there is a contention over and a challenge to power. Power does not derive from language, but language can be used to challenge power, to subvert it, to alter distributions of power in the short and long term. (Weiss & Wodak 2003:15)

As this research aims to discover the way(s) in which political discourse pre- and post-Tahrir Square has evolved to reflect on the changing power structures in Egypt, it seems befitting to employ a method that enshrines this dialogical language–power paradigm at its core.

3.2. Theoretical Tools

Many theoretical concepts used in this study have provisionally been defined earlier in this chapter. The following two sections will briefly elaborate on the most relevant.

3.2.1. Intertextuality and Interdiscursivity

Two ideas in the critical discourse analyst’s palette will be much used in this work, what Fairclough terms manifest- and constitutive intertextuality, the latter of which is also known as interdiscursivity (Fairclough 1996:102). We have established that all “texts,” spoken or written, draw on other texts and discourses to make sense to the interpreter, that is, they are informed to a varying degree by other systems of knowledge and meaning. Texts are therefore “inherently intertextual” (ibid.). There are several ways in which a text reflects on, alludes to, incorporates or embeds other discourses and knowledge. Manifest intertextuality, henceforth simply intertextuality, indicates that the borrowing is explicit. In his work, Fairclough deals with five instances of this type: discourse representation, presupposition, negation, metadiscourse and irony (ibid. 118-23). Each in their own way directly refer to utterances made by other people. Discourse representation can be, but is not limited to direct quotes; it has to do with reporting what someone else has said. Presupposition are taken for granted propositions by the text producer; the compound phrase “the Islamist threat,” for example, assumes that such a threat exists. Negating something naturally implies that someone else has previously stated the contrary. Metadiscourses arise when the author distances him/herself from parts of the own text to comment on or differentiate various levels of the narration, treating it as if it were an external text. Paraphrasing, metaphors and hedging belong to this subfield. Irony, finally, is traditionally taken to mean “saying one thing and meaning the opposite.” It may express a negative attitude towards, criticizing or ridiculing, something someone else has stated in the person’s own words. This form has interesting implications on the intersubjectivity of producer and interpreter since it a) assumes shared attitudes to that which is expressed, and b) depends on the interpreter being able to recognize the irony, taking the meaning to be antithetical to that which is expressed.

If intertextuality highlights relations between texts, interdiscursivity can be seen to more broadly address, “relations between discursive formations or more loosely between different types

of discourse” (ibid. 47). However, it may equally apply to cases on textual level where the reference to other texts is indeterminate and implicit (ibid. 124).

3.2.2. Styles: Tenor and Rhetorical Mode

I have already dealt with social languages or genres above. Genres are commonly associated with a particular style, although alternatives exist (ibid. 127). An op-ed genre, in this case, is most commonly related to a formally written texts with the purpose of relating to and politicizing some contemporary event. There are, of course, several ways this can be done. The terms tenor, mode and rhetorical mode address variations in style of written or spoken language of any specific genre.

Tenor, first, addresses the relationship between interlocutors, which can be “intimate,” “casual” and so on (ibid.). In this work, it is likewise taken to mean the tone and attitude of the message communicated. Mode, in turn, applies to the particular form of the text, if it is written, spoken or a combination (i.e. written-as-if-spoken etc.). In my case, all articles are simply written and the analysis will not deal with this particular aspect of style. More significantly, rhetorical mode is used to classify texts according to the exposition of language, such as “argumentative,” “descriptive,” “explanatory” and so on (ibid.).

Chapter 4:

Method and Data Selection

Having outlined the methodological and theoretical stance of this research, we turn to the practicalities of the study. The first section in this chapter treats some methodological and technical challenges resulting from the choice of method and research topic, and how these were met. I then turn to the procedural details of the method, such as selecting scope and timeframe, indexing and delimiting the material.

4.1. Methodological Considerations 4.1.1. Chickens and Eggs: a Self-Evaluation

Working with a meta-theory such as discourse theory, it is easy to lose oneself in its theoretical complexities. The researcher may unwittingly, and perhaps as a result of simple causation, “create” the discourse that s/he is investigating through the research focus and personal categorizations (Kirkegaard 2004:48). As a researcher, it is easy to topple into the pitfalls of this chicken-and-egg causality, arriving at research outcomes that are nothing but consequences of the research strategy, the active choice of sources and data, selection of analytical tools and definition of concepts. Perhaps I myself am guilty of such “ingenuity.” Having chosen Rubin Barry as my main theorist on Arab liberalism, and my reliance on his definition of the term, naturally frames this study. Putting liberalism at odds with Islamism as I seemingly have in the Chapter 2 is another example, and one that I do not consistently subscribe to at that4. For the terminology I have chosen to identify or name

discourses in the op-eds investigated in this study, it should follow that these are by necessity re-presentations of ongoing political discussions in Egypt through the conceptual lens of the author, that is, me. Their validity must be weighed against the strategy employed to define them. For this reason, the following chapter aims to clarify the process of data collection and delimitations thereof, and to describe the research strategy.

4 There is no immediate logic to the claim that political Islam cannot function liberally like many Christian–Democratic parties in the West have (cf. Stacher 2001:84).

4.1.2. Technical Difficulties and Solutions

An initial and lingering challenge presented itself in the data gathering for this study. Libraries commonly keep catalogues and archive back issues of news media on microfilm or hardcopies and, increasingly, as scanned PDF:s. In addition, they have access to various public databases, such as Library Press Display. Perhaps naively, I believed that leading Egyptian newspapers would be easily availed; Egypt has a long intellectual and literary history and I pictured the interest for Egyptian news media would be warm outside the country. Given the research aims (Chapter 1), it was imperative to access articles as they were presented to the Egyptian public in the original Arabic language. Newspapers traditionally have farther reach than internet-based news sources, so it was important to get hold of original paper issues of the journals (web versions of some major Egyptian newspapers had proven to be slightly different from the printed versions on an early inspection). The process, as it turned out, took more than a month to complete during which I contacted various local and international database administrators, library staff, newsrooms and even a few Egyptian freelance journalists. The literature list (section “Databases and Library Catalogues”) will reveal the extent of this information search. In the end, I settled for scanned PDF:s of printed originals available through the web archives of the two studied newspapers but with adjusted timeframe (see 4.2.1. below).

As a consequence, I had to modify my initial idea to study one state-run (Al-Ahram), one independent (Masry Youm), and one more “radical” independent newspaper (Tahrir or Dustour), simply because it proved too difficult to acquire originals of the latter (Masry al-Youm’s online data archive coincidentally crashed during the information collection process). Instead, as a deserving runner-up the selection fell on Al-Shorouk, an independent newspaper that was remarkably favored during the revolution: its circulation had doubled to 150,000 a day by March 2011 (the Guardian Mar 10, 2011). Al-Ahram, the biggest state-run newspaper in Egypt, has a circulation ranging from 300,000 to 900,000 copies on weekdays and over a million on Fridays according to the Oxford Business Group (2010:183). Real circulation figures for state-run press in Egypt seem hard to establish, however: one media analyst claims Al-Ahram weekday circulation to be closer to 140,000 (the Guardian Mar 10, 2011).

With the choice of newspapers settled, I sampled the timeframe for the study (explained in 4.2.2.). This however resulted in 133 op-eds to cover, creating another methodological dilemma. In qualitative studies large selections of empirical data will necessarily affect the analysis negatively. Qualitative studies have a tendency to inflate, generating more data than one initially starts out with. It becomes difficult for a single person to retain so much information while at the same time

preserving a coherent overview of the material, and chances are important points are lost. This difficulty compelled me to employ quantitative methods to organize and delimit the material. These are described below (4.2.4.)

On a final note, I wish to discuss the consequences of poor adaptation of right-to-left (RTL) languages in many word processors. For my computer of choice, there are limited resources to manage Arabic script. The Arabic language consists of 28 consonants, which can be written in two to four conditional forms. The letter t!’ (“t”), for example, is drawn in four distinct ways depending on its position in the word (initial, medial, final or isolated = in reverse: ! "#$% "%&$% "%'). This creates a cursive style of writing whereby each letter of a text is merged typographically into compound words. Most word processors, however, cannot reproduce this morphology: Office 2011 for Mac cannot link Arabic letters at all (!), whereas iWorks do in only certain fonts:

The words “the Arabic language,” “()*+,-. (/0-.,” turn into “!"#$%&' !(&&'” as a result.

In the first (correct) instance, I had to change the Times New Roman font to Times or Helvetica. In addition, the use of Arabic letters in the preceding paragraph disconnected the default tab stop in this section and I had to insert a first line indent manually. Furthermore, the text cursor (|) disappears in Arabic script, making editing of already typed Arabic text a painstaking task. For these and other formatting disadvantages, I have chosen not to include original Arabic quotations in the analysis and instead translate directly to English. While this affects the means to control the accuracy of my translations, I have likewise offered a careful and systematic index of the material (“Appendix I: Opinion Article Index”) that may guide the studious reader to the cited text in the source material. For the non-Arabic-speaking audience this choice should be inconsequential.

4.1.3. Literature Critique

Whereas much of the literature used in this study is uncontroversial, that is, established academic works or scientific databases and reference literature, there is likewise a high dependency on news media sources to be noted (see “Sources”). The explanation for this is that the Arab Spring, due to its overwhelming scope and recentness in history, is still being examined by scholars of various backgrounds. Academia, it seems, is still to “catch up” with the new realities in the MENA. Because of the current lack of scholarly works to base this research on, I have turned to online news media to trace the Arab Spring, and to inform myself Egyptian conditions and events throughout 2011–12. The use of several major news agencies to get a combined impression should to some extent counter the negative effect of these sources on the overall reliability of this study.

4.2. Procedural Features of the Study 4.2.1. Data Collection

Data collection has been dealt with in some detail in subsection 4.1.2. above. Having decided on Al-Ahram and Al-Shorouk as my primary empirical data, I set out to determine the days which were to be covered. To avoid selecting days of news drought some key dates were chosen. Originally, these were June 6, 2010 (the day of the murder of blogger Khaled Saeed whose death became a symbol during the Tahrir Square demonstrations), February 11, 2011 (Hosni Mubarak’s resignation), and as close to parliamentary by-elections of 2011 as possible (in my case September 2011 when the data was gathered). Since no archive material was available for June 2010 (another technical dilemma), the first annual commemoration in 2011 was selected, and the starting point became the November 2010 elections.

Secondly, a newspaper’s political profile is generally defined by its editorials and opinion pages. Since the political discourse was targeted these became my primary focus. However, the two newspapers studied had no clear editorial page, or only did so on selected days, why I determined to look exclusively on the op-eds.

4.2.2. Sampling the Timeframe

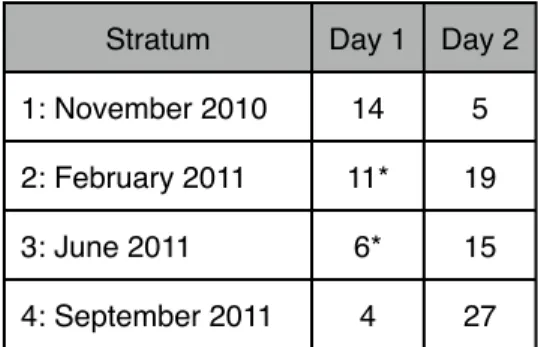

The material in this study has been chosen through a semi-randomized sampling technique employing both stratified random sampling and purposive or non-probability sampling (cf. Chambliss & Schutt 2006:97, 101). The fixed dates in this purposive sampling were February 11 and June 6, 2011; the rest were generated through random sampling in the four strata (months) through Random.org website. The site offers random number sampling based on atmospheric noise rather than number algorithms conventionally used for random sampling (Random.org). One day in February and June 2011 and two days in November 2010 and September 2011 were randomly sampled creating the following timeframe:

Stratum Day 1 Day 2 1: November 2010 14 5 2: February 2011 11* 19

3: June 2011 6* 15

4: September 2011 4 27

4.2.3. Data Indexing

As the third step in the inquiry, it was necessary to index the data collected by creating a spreadsheet database of op-ed material (available as “Appendix I: Opinion Article Index” at the end). Index letters were uniquely given to each of the eight issues (sampled days) of Al-Ahram (A to H) and Al-Shorouk (O to V). It was then an uncomplicated task to identify individual op-eds by page and article number (starting top to bottom of page, right to left in agreement with Arabic writing customs). Through this process, an overview of the material was gained while simultaneously creating a practical referencing system for the analysis. Instead of a bulky “Al-Ahram Feb 19, 2011, page 7:1” the reference is replaced with the index “D7:1,” where the letter D indicates newspaper source and date. Please view coding key in Appendix I and Table 2 (Chapter 5) for further information.

4.2.4. Further Delimitations

The compiled op-ed material from the eight dates altogether comprises 133 articles. Inevitably, I had to limit the material further and intended to do so by setting a word range limit. Having an interest in longer texts where the author has the opportunity to develop his or her arguments, I set this range to 750-1000 words, the lower figure corresponding to a common word limit for op-eds (cf. The New York Times n.d.; Sourcing Journal Online n.d.). Word limits vary between newspapers but many editorials accept contributions exceeding these limits for consideration, some up to 1,200 words (The Op-Ed Project n.d.; Communications Consortium Media Center n.d.). The Washington Post specifically asks for 750-1000 words (Columbia University 2010:6) providing the limits also for this study.

While theoretically a straightforward task, Al-Ahram’s collected PDF material turned out to be saved as a non-searchable image rather than text/image file, making any attempt to search or extract words from the documents impossible. Even in the case of Al-Shorouk, copy-pasting text passages into word software proved overwhelmingly complicated since spaces and some special Arabic characters turned out as indecipherable icons (and needed to be deleted one by one). Even a fairly sophisticated OCR software like Readiris Pro with Arabic language support could not perform the translation to word file for any of the newspapers.

Again in this somewhat troublesome data collection and delimitation process, I had to resort to a creative though unorthodox solution. Both newspapers use a similar font that turned out in both cases to be two millimeters in my printed copies. I thus measured the height and width of eight articles, four from each newspaper, and counted the number of words manually. This allowed for an

approximation of word per square centimeter (cm2) text (please view “Appendix II: Average Word

Calculation” for details); I then measured the remaining articles and estimated number of words based on that average. Through a final strike of luck, not only did thirty op-eds turn out in the defined range – a manageable amount – but fifteen from each newspaper.

4.2.5. Delimited Sample versus Complete Sample Inquiries

This study primarily considers the “Delimited Sample” – the thirty articles within the 750-1,000 word range that will be scrutinized using discourse analysis. Nevertheless, I have benefited from the (133 article) “Complete Sample” when determining the impact of the Arab Spring on opinion pieces from February–September 2011 (section 5.2. in “Analysis”). The complete sample was manually scanned for references to the revolution (keywords like “Tahrir Square,” “the January 25 Revolution” or “the Demonstration of the Millions”) to assess how much of the Complete Sample was affected by the event. Each article mentioning the revolution was marked once and percentages could be established.

Chapter 5:

Analysis

This chapter begins with an assessment of the empirical material from November 2010. The following sections deal with developments in the political debate after the overthrow of the Mubarak regime and ceding of power to the transitional military government, during which time the future political trajectory of Egypt was thoroughly debated; first through the lens of the revolution supporters and reformers, then the more reluctant or critical. This organization of the chapter also lends the presentation a certain chronology, as will be explained.

As a guide, please view Table 2 over indexes used for referencing throughout this chapter.

Date Al-Ahram Index

Letters Al-Shorouk Index Letters nov 5, 2010 A O nov 14, 2010 B P feb 11, 2011 C Q feb 19, 2011 D R jun 6, 2011 E S jun 15, 2011 F T sep 4, 2011 G U sep 27, 2011 H V

Table 2. Referencing Guide!

5.1. Before Tahrir Square

On November 28, 2010, regular Egyptian parliamentary elections were held. Front page stories in both newspapers on the fifth and fourteenth are concerned with the electoral run. Main concerns are the National Party’s (NP) candidature (e.g. A1:3>A7:2; B1:1), the refusal to enlist Islamist candidates, and the imprisonment of several MB candidates (e.g. A1:3>A7:1; O1:5>O4:1; P1:2). Al-Shorouk discusses the UN statement that Egypt is a “democracy without rotation” (O1:2). Both Al-Ahram and Al-Shorouk include articles on threats against Egyptian Copts by al-Qaeda (A1:1; O1:3) in connection with the organization’s attack on a Catholic church in Baghdad on October 31 (al-Masry al-Youm Nov 1, 2010).

Op-eds during this time refer intertextually to these events. “The Criminal Mind...Threatens Egypt” by Editor Usama Soraya, making first page headlines, is a vindictive debate article, its language resembling that of the Arabic rhetorical form ta"r#$ (“agitation” or “incitement”). Its opening statement illustrates this tone:

Stay safe O Egypt from each treacherous and cowardly villain. Stay safe O Egypt with all your Christian and Muslim [people] from each conspirator that does not know your destiny and unaware of your [value]. (A1:1)

The dramatic language in this passage is underscored twice by the address “O Egypt,” evocative of ecclesiastical texts and poetry. The convention to incite and fend oneself through conspiracy imagery noted previously (2.3.) is seen in the “treacherous villain” and the “conspirator,” this time directed at al-Qaeda. He continues: “the criminal mind hits the safety of Muslims [with] lies and calls for extremism” but, he asserts, “these terrorists do not know the true Egyptian human alloy” (A1:1), referring to the assumed resilience and brotherhood between Egyptian Muslims and Copts.

The article is more than a call for unity among the ranks against al-Qaeda, as later passages reveal:

Today we recognize the reality of policies and decisions taken in Egypt to protect its unity and security […] Some days ago there was a decision to close several satellite channels that frequently had transgressed and for which we have been very patient. Many of us went on to explain this in light of the upcoming elections, not realizing at the time that many of these channels had sunk into the depths of the fitna […] Today we recognize how much these satellite channels with their poisons and devious intentions represent a real threat to all Egyptians, and today we recognize also just how false some media practices were for exploiting the freedom in our country.

This segment is replete with intertextual and intersubjective implications. First, the elections are mentioned by name; we see how they play a direct role in contextualizing some contemporary interpretations of the closure of (mainly religious) satellite stations. However, in refuting this standpoint, defending instead the official position that the act was motivated by a genuine concern for national safety and integrity, the author interdiscursively sides with another unmentioned party: the government. For it is the government who authored the “policies and decisions” mentioned in the first sentence, and who banned the broadcasters. Second, intersubjectively, there are two coexisting self-identifications, two distinct “we:s,” in this text (compare “today we recognize” and “many of us”). On closer inspection, these actually designate an “us” and “them.” The “many of us” directs an implicit accusation against the critics, the others, who were too quick in the mind of the author to blame the government for interfering in elections.

So who is this “we” that has been patient with the satellite stations and that has come to recognize the appropriateness of government decision-making? The readers of Al-Ahram? Us, the Egyptians? Partisans of the NP or the government itself? The rhetoric of this piece is normative both in the way that the author fashions himself as the spokesperson for a political grouping, and in the priority he gives to his “truth,” dismissing opponents as unaware (“not realizing”). And who are the others? The subject matter itself implicates not only al-Qaeda, but the Islamist bloc in general, and the MB are most certainly included; they were likewise complicit in spreading their “poisons” through the closed stations. Adding to this association is the use of the term fitna, meaning “trial” or “temptation,” a religious reference to the division of Islam into Shiism and Sunnism with connotations of secession and upheaval. To be sure, the article is more than a warning against extremism; it is likewise a call for unity and siding for the “home team” in the upcoming elections.

Characteristic for op-eds from this time is the ambiguous narration and roundabout way of stating a case, especially in the selected articles from Al-Ahram. Both the dispute over historic interpretations in “The Man Who Pronounced Egypt’s Defeat in the October [War]” and the Coptic Pope Shenouda’s piece “Effects on the Mind and Thought” (B10:2) and are examples of indeterminate texts with several possible interpretations. In the latter, Pope Shenouda initially talks about how the human intellect and feelings are interconnected, how the mind influences the heart which then may grow into will and action. At first, it seems like a philosophical or spiritual piece; he mentions how feelings affect both the conscious and unconscious, highlights the importance of reading and talks appreciatively about the education of women. He urges readers to tend to the integrity of their intellect.

Verily, God has created you with two ears. In a symbolic way, in order to listen to one point of view and […] the point of view of the other, and not depend on one idea only […] Rather, focus your mind on what you hear, welcome what is beneficial, and reject what harms, and don’t make your mind dependent on your ears, that is, don’t be [overly] receiving and don’t believe everything that you hear, but examine everything. (ibid.)

The first two clauses seem to call for more tolerance and openness to other’s opinions. In the third clause, however, he dissuades readers against being too naive. The intertextuality is subtle, though: there is no passage in the article as such that indicates what this warning refers to. The upcoming elections and the closing of satellite channels, as well as al-Qaeda intimidations against Copts could foreground this piece. To underline this vagueness, the article then discusses the effect of music on the mind.

As a contrast, one op-ed, “Distortions of Egyptian Political Life as Shown in the Parties’ Electoral Programs” published in Al-Shorouk on November 14, 2010, is particularly outspoken. The article, written by the Research Director at the Carnegie Center in Beirut, champions many liberal ideals, among them the need to revise the electoral system, both legal and procedural, to improve political pluralism and secure fair elections, and increase political participation on a societal level (P14:1).

During these past few days, the ruling NP has presented its intended and excluded candidates and absurdly [listing] more than one candidate per electoral seat, conclusive evidence of the continuing systematic distortion and failure of modernization efforts led by its General Secretariat and the Secretariat of Policies to convert it into a “normal” political party. (ibid.)

In “normal” situations, the author claims, candidates for government compete with members of other parties for electoral seats, not with candidates from their own ranks. He also criticizes the NP for its “absolute silence” on the topic of a possible repeal of the Emergency Law.

As for Egypt, and in its distorted political life, the possibility for rotation of power is lacking, and everyone knows in advance that the results in elections will not alter the NP’s dominance in the People’s Assembly. (ibid.)

The author does limit his critique to the ruling party, but likewise comments on the MB program, stating that while it addresses current economic, social and political conditions, it offers little alternatives; it is “satisfied with rhetorical generalities and unsupported analyses” (ibid.).

Having limited space to develop what is in reality a complex and initiated political analysis, suffice it to say that the break from the obscurity of other contemporary op-eds and open advocacy for political liberalism presents an exception in the sample. Next, we will begin to study the impact of Tahrir Square on these conditions.

5.2. The Liberal Infusion and the Birth of the Tahrir Square Discourse

There is a similarity to be noted between the Tahrir Square demonstration slogans and some core liberal ideals (view 1.1. & 2.2.). The Arab Spring may just represent the infusion of political liberalism into the popular discourse in the MENA. “There is a new appreciation for liberalism in the Arab world after the revolution” (Liberal International n.d.). While the political significance of the revolutions is still to reach its denouement, there is little doubt that the discursive impact of Tahrir Square in Egypt is exceptional. Of the 24 op-eds in the Delimited Sample published after February 2011, all but two (S11:3; V11:3; both concerned with the Palestinian application for UN membership – neither expresses liberal values why they have been omitted in the analysis) relate in

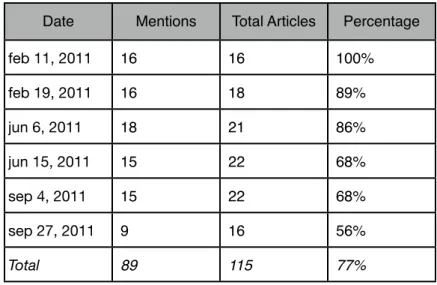

some way to the events at Tahrir Square. To better appreciate just how pervasive the synonymous phrases “Tahrir Square,” “the January 25 Revolution” or “the Demonstration of the Millions,” along with other references to the revolution have been since February 2011, I turned to the Complete Sample of the empirical material (listed in Appendix I). Table 3 summarizes the result of this examination.

Date Mentions Total Articles Percentage

feb 11, 2011 16 16 100% feb 19, 2011 16 18 89% jun 6, 2011 18 21 86% jun 15, 2011 15 22 68% sep 4, 2011 15 22 68% sep 27, 2011 9 16 56% Total 89 115 77%

Table 3. Mentions of Tahrir Square Demonstrations in Sample

Out of 115 articles in the sample published from February 11 to September 27, 2011, 89 contain at least one such reference, whether explicitly discussing the revolution and the effects thereof, or mentioning the events as a way to contextualize an adjacent debate. While not claiming any statistical accuracy for which a substantially larger sample size and measure frequency would be necessary, the percentages indicate that Tahrir Square, in its various appellations, has received much attention in the political debate in post-revolution Egypt in the two newspapers studied. As late as September 27, 2011, Tahrir Square is still discussed in a majority of op-eds in the sample, although this influence is diminishing with time elapsed since the revolution, decidedly so after mid-June. The results are graphically presented in Pictures 1 and 2.

Picture 1. Mentions per Total Op-Eds! ! Picture 2. Percentage Mentions over Time

0% 25% 50% 75% 100%

11-Feb 19-Feb 6-Jun 15-Jun 4-Sep 27-Sep 0 5 10 15 20 25

11-Feb 19-Feb 6-Jun 15-Jun 4-Sep 27-Sep

Percentage Mentions Total Debate Articles