A service designed on the context of a surveillance society

in an increasingly connected world

Dorien Koelemeijer August 2015

Thesis Project – Interaction Design Master’s Programme K3, Malmö University, Sweden

Date of Examination: 20th of August, 2015 Dorien Koelemeijer Interaction Design (M. Sc.) info@dorienkoelemeijer.com Supervisor: Linda Hilfling Examiner: Susan Kozel

The privacy and surveillance issues that are consequences of the Internet of Things are the motivation and grounding for this thesis project. The Internet of Things (IoT) is a scenario in which physical objects are able to communicate to each other and the environment, by transferring data over communication networks. The IoT allows technology to become smaller and more ubiquitous, and by being integrated in the environment around us, the world is becoming increasingly connected. Even though these developments will generally make our lives easier and more enjoyable, the Internet of Things also faces some challenges. One of these are the aforementioned privacy and surveillance issues that are the results of transferring sensitive data over communication networks. The aim of this thesis project is therefore to answer, both in a theoretical, as well as in a practical way, the following research question: How can the Internet of Things be more accessible and safe for the everyday user?

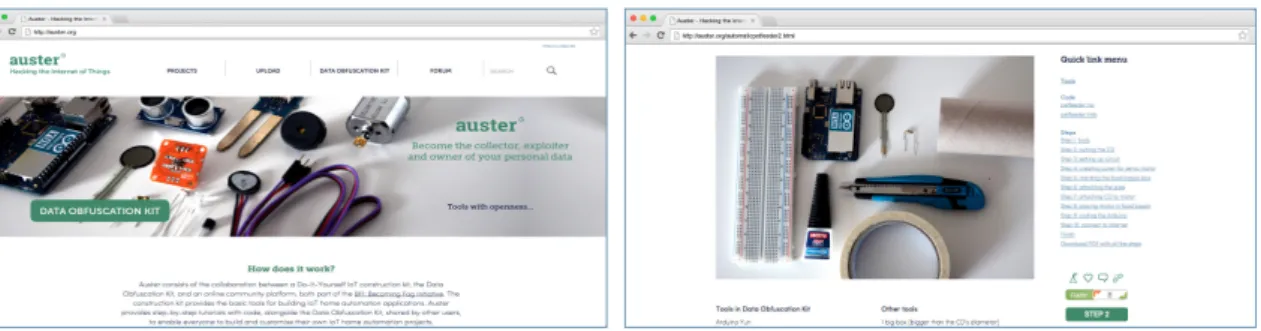

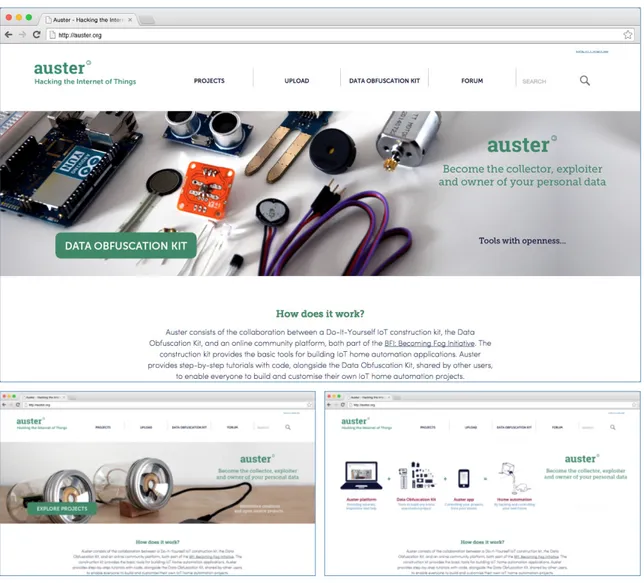

Accordingly, the Auster online platform, the Auster app and the Data Obfuscation Kit were developed to provide people with the tools and knowledge to construct home automation projects themselves, as an alternative for using applications from governments and

corporations alike. The aim is to create a way to endow people with the capability to exploit their talents, realise their visions and share this with a community joining forces. By enabling people to create their own home automation projects, personal data is kept in the user’s possession and the collection of data by governments and companies alike is prevented. Moreover, by giving the control over technology back to the user, creativity and innovation in the field of the Internet of Things in domestic environments are expected to increase.

Acknowledgements

Over the course of this thesis project I have received support and encouragement from a number of people. First of all, I would like to thank my supervisor Linda Hilfling for her assistance and guidance throughout the process of writing this thesis. I also wish to express my gratitude to my dear friend Nadine Kuipers for her loyalty and proofreading of my draft. In addition, I want to thank Kim Antonissen, Emma Raben and Franziska Tachtler for sharing their vision and opinions on the design related aspects of this thesis project and for lifting my spirits when I was in need of it. Lastly, I would like to thank my parents and sister for always supporting me.

1. Introduction 2. Background

2.1 From a network of computers to a connected world 2.2 Architecture of the Internet of Things

2.3 Influence of the Internet of Things

2.4 A user’s influence on the Internet of Things 3. Problem domain and grounding

3.1 Privacy and security issues 3.2 Breadth and scope

4. Conceptual discovery 4.1 Sousveillance 4.2 Becoming fog

4.3 Hacktivism and hacking 4.4 Do-It-Yourself

5. Related work

5.1 Home automation products and services 5.2 Data sousveillance

5.3 Online (DiY) platforms 6. Role of the interaction designer 7. Research methods

7.1 Research Through Design 7.2 Design process

8. Auster

8.1 The concept

8.2 The Auster platform 8.3 The Data Obfuscation Kit 8.4 The Auster app

9. Use cases 9.1 Andreas 9.2 Emma

10. Discussion and conclusion 10.1 Discussion

10.2 Conclusion References

Image credits Appendices

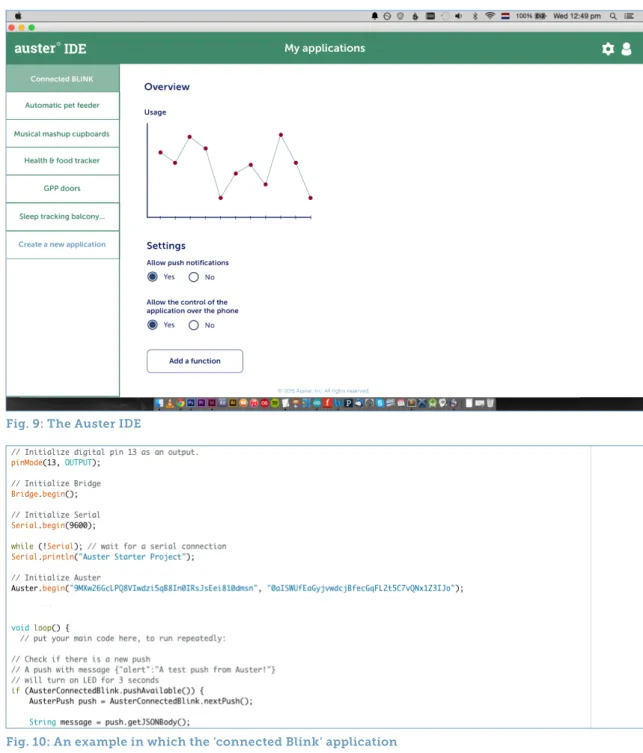

Structure of the Auster platform

Analysis of the hardware base of the Data Obfuscation Kit 4 7 7 8 9 10 11 11 16 17 17 17 18 19 20 20 22 24 25 26 26 26 32 32 34 35 39 41 41 47 51 51 55 56 62 63 63 71

Table of contents

At the moment I’m writing, there are no technical restraints to keep humans from turning science fiction into reality. Inventions that once seemed to come from another world -

described and presented in so many sci-fi books, films and series - progressively start to look like our own. Last year the company Arx Pax has developed a fully functioning prototype, called the Hendo Hoverboard (Pax, 2014-2015), inspired by the fictional levitating device used by Marty McFly in the film Back to the Future II (Zemeckis, 1989). Even though new technologies are used to create a range of products and services, most of these products are generally becoming smaller and more ubiquitous, making the world around us progressively connected. The emerging Internet of Things (henceforth IoT) will have a big influence on this development. The IoT is a network of physical objects and systems, embedded with electronics, software, sensors and connectivity. These connected devices and systems interact with each other and the environment, by transferring big amounts of data over communication networks (Wong & Kim, 2014). Mark Weiser already predicted this development of technology in 1991: “The most profound technologies are those that disappear. They weave themselves

into the fabric of everyday life until they are indistinguishable from it. My colleagues and I at PARC think that the idea of a ‘personal’ computer itself is misplaced, and that the vision of laptop machines, dynabooks and ‘knowledge navigators’ is only a transitional step toward achieving the real potential of information technology. Such machines cannot truly make computing an integral, invisible part of the way people live their lives. Therefore we are trying to conceive a new way of thinking about computers in the world, one that takes into account the natural human environment and allows the computers themselves to vanish into the background” (Weiser, 1991, p. 78).

The fact that technology has become ubiquitous is making our lives easier and often more pleasant. There are, however, consequences of these rapidly evolving technologies, such as the privacy and surveillance issues, that have also long been envisioned in the past. Ten years ago Steven Spielberg directed Minority Report (Spielberg, 2002), based on a short story by Philip K. Dick (Dick, 1998), showing a futuristic world in which the government is seeing and all-knowing. The story is set in Washington D.C. in 2054, where no murder has been committed for six years. This is due to the fact that the surveillance state uses behaviour prediction technologies to prevent crimes before they happen. However, this technology predicts that the Chief of the Department of Pre-Crime will become a future criminal. He flees and is forced to take measures in order to prevent a surveillance state that uses biometric data and

sophisticated computer networks to track its citizens. Current technology has developed so fast, that this futuristic setting is no longer in the realm of science fiction, but has become reality fourty years before it was anticipated. Nowadays, governments and corporations alike are using technologies such as iris scanners, enormous databases and behaviour prediction software that are incorporated into a cyber network, to track people’s lives, predict their thoughts and control their behaviour by collecting personal data.1 The exploitation of this data

can lead to discrimination by insurers, employers and in the future it can even lead to genetic spying. The Circle by Dave Eggers (Eggers, 2014), which could be described as a modern take on George Orwell’s 1984 (Orwell, 1949), also hints at the dark side of pervasive surveillance, and suggests that the pleasures of the consumer society will lead people to walk willingly into their chains. The Circle, as described in the book, has taken over all the big Silicon Valley tech companies, linking users’ personal emails, social media, banking and purchasing with their universal operating system, resulting in one online identity and a new age of civility and transparency. “A couple of quick mergers could make it so. Eggers’ novel reads more like journalism and critique than like fiction. 1984 presents a disturbing vision of what might eventually be; The Circle pretty much describes what already is, and where it’s surely headed” (Cowlishaw, 2014, para. 3).

The fast development of technology, as well as the increasing ease of sourcing technological parts, has contributed to the emerging popularity of the maker culture, which can be described as a technology-based extension of the Do-It-Yourself (DiY) culture (Dougherty, 2012). The increasing importance of the maker culture has prompted me to reconsider the role of the interaction designer: where it was once the task of an interaction designer to create ideas, products, and services for the future society, I believe it has transformed to understand the context of these ideas and to create a fitting environment or platform for these to exist in. This thesis project aims to propose a solution for the possible scenarios that are able to occur in the context of the Internet of Things in a surveillance society. The transferring of data is what IoT technologies rely on; however, it is also the core of the issues. The emerging Internet of Things will cause an increase in connected devices, mostly sensors, which function by

1 Personal data concerns any information relating to an individual who is or can be identified by data or from the data in

conjunction with other information regarding his physical, physiological, mental, economic, cultural or social identity (Office of the Data Protection Commissioner, 2015).

receiving and transmitting data. “No one really understood how the Internet was going to affect things, and the impact of the IoT will probably be more pervasive, rolling out over time, but affecting us more immediately and in more profound ways” (Bradbury, 2015, A Big Brother made of little things section, para. 3). One thing is for sure: data generation will only increase and the conclusions that can be obtained from it will become more precise and more intrusive. Edward Snowden has warned that unless we challenge the status quo, future surveillance will be in the hands of countries, companies and criminals (Ingham, 2015). The problems regarding surveillance and privacy, alongside the lack of involvement of the everyday user in the development of new technology, which substantiates Snowden’s warning, have made me realise that the power over IoT technologies should be with everyday users. I think the transforming role of the interaction designer can provide possibilities to improve the engagement of the everyday user with technology, such as the IoT. Therefore, the aim of this thesis project is to answer and find a solution to the following research question: how can the Internet of Things be more accessible and safe for the everyday user?

2.1 From a network of computers to a connected world

The first version of what is known today as the Internet was created in the 1960s by a group of idealists that saw opportunities in connecting computers to each other. As a result ARPANET, the first computer network, was developed to connect four major computers (Salus, 1995). The Internet has evolved greatly after this, by becoming ubiquitous, faster and more accessible to the general public (Pletikosa Cvijikj & Michahelles, 2011). Instead of only connecting computers to each other, and allowing humans to interact with them, the newest development of the Internet has established a network connecting digital information to real world physical items.

The exchange of information between systems or devices, by automatically transferring data over communication networks (wired or wireless) without any manual input is the main purpose of this integrated version of the Internet, called the Internet of Things (Wong & Kim, 2014) (Borgohain, Kumar, & Sanyal, 2015). The IoT provides the embedding of physical reality into the Internet, and information into the physical reality. Physical objects are connected by using sensors, computer chips, actuators, and other smart technologies to other computing devices, such as cloud servers, computers, laptops and smartphones (daCosta, 2013). By seamlessly integrating these physical objects into the information network, the IoT allows not only person-to-object communication, but also object-to-object communication (Uckelmann, Harrison, & Michahelles, 2011).

Moreover, the Internet of Things provides possibilities to exchange data not only between devices but also between systems, enabling them to interact with each other, increasing their efficiency, reliability and sustainability (Mukhopadhyay & Suryadevara, 2014). However, multiple challenges still need to be addressed before the vision of IoT becomes a comfortable reality: “The central issues are how to achieve full interoperability between interconnected devices, and how to provide them with a high degree of smartness by enabling their adaptation and autonomous behaviour, while guaranteeing trust, security, and privacy of the users and their data” (Bandyopadhyay & Sen, 2011, p. 50).

2.2 Architecture of the Internet of Things

The IoT relies on devices or systems that share data with other devices or systems, by being connected to communication networks. This process is achieved by an architecture consisting of five layers, separating two different divisions with an Internet layer in between. The first division contributes to data capturing, while the second division is responsible for data utilisation and the distribution of applications (fig. 1).

The first division includes an edge technology layer and an access gateway layer. The edge

technology layer is the hardware layer, consisting of sensor networks, embedded systems,

RFID tags and readers, providing identification and information storage, information collection, information processing, communication, control and actuation. The edge

technology layer is the layer a user would generally hack into in order to, for instance, create own home automation applications. The access gateway layer handles the first stage of data, by taking care of message routing, publishing and subscribing.

The second division consists of the middleware layer and the application layer. The

middleware layer can be envisioned as a mediator between the edge layer and the applications

layer. Functions of this layer include managing the device and information, filtering and collection of data, accessing control and retrieving information. In other words, this layer has the function to make sense of the data that is sent from the edge layer to the application layer. Fig. 1: The different layers of the architecture of the Internet of Things

Personal data protection is most needed in the middleware layer, since this data could be sensitive and permits user profiling by governments or corporations alike.The application

layer is responsible for distributing various applications to IoT users, in the different

application domains (Bandyopadhyay & Sen, 2011). This is the only layer users get in touch with or have control over when buying IoT applications from companies.

2.3 Influence of the Internet of Things

The aim of the Internet of Things is to enable communication between different systems and devices, along with streamlining the interaction between humans and the virtual environment (Borgohain, Kumar, & Sanyal, 2015). The IoT creates the possibility to connect almost anything to the Internet, from paperclips to airplanes. Therefore, this technology finds its application in almost any field, which makes the domain enormous. IoT technology will provide benefits in application domains such as the automotive industry, the connected home, the telecommunications industry, the medical and healthcare industry, the retail, logistics and supply chain management, and the transportation industry. Even though IoT technology is applied differently in all these distinctive domains, devices are generally equipped with RFID technology, advanced sensors and actuators. The main purpose of implementing IoT technology is to improve sustainability, efficiency and comfort, and decrease energy use and overproduction (Bandyopadhyay & Sen, 2011). The aim of the connected city for example, is to make better use of public resources, aspiring to improve the services offered to citizens, while reducing costs. By increasing transparency, IoT technology in cities will improve the management and maintenance of public areas, protection of cultural heritage, garbage collection and the constitution of hospitals and schools (Zanella, Bui, Castellani, Vengelista, & Zorzi, 2014). The healthcare application domain requires additional transparency on a patient’s vital signs and body functions, such as glucose-level readings, blood-pressure monitoring, abnormal heart activity and body temperature. These measurings are conducted by body sensors and the derived information is shared with physicians and doctors, to prevent the patient from, among other things, unnecessary check-ups and provides possibilities for doctors to detect diseases in an early stadium (Kellmereit & Obodovski, 2013) (Turcu, Turcu & Tiliute, 2012). The examples above already indicate that IoT applications rely on transparency, deducible from the data generated by connected devices (Bandyopadhyay & Sen, 2011). In the cases of connected cities and the healthcare industry, users do not have much influence on the way IoT technology is applied. There is however an application domain in which the private user has more authority: the domestic setting or the so-called connected home.

2.4 A user’s influence on the Internet of Things

Connected devices at home enable actions such as the measuring of the productivity of home tasks, and the tracking of people’s mood and vital signs. These actions rely on the decoding of data that is generated by the use of unobtrusive body sensors and other connected devices. The aim of the connected home is to adapt itself to the people living in it. Unobtrusive body sensors improve the automatic communication with the home system, allowing better control of temperature, light, smart appliances and security (Kellmereit & Obodovski, 2013). Moreover, users have the exciting opportunity to automate their home and control different applications with a smartphone, or let things in the house respond and probe action depending on various inputs and outputs (Miller, 2015). John Elliott makes the following predictions about home appliances that are improving the standard of living by collecting the user’s personal data: “All major appliances are going to be connected, and the value of the information from major appliances will be worth a lot for those appliance manufacturers. Not only will they discover usage patterns, but also ways to better manage marketing and supply chain around parts replacement by staying connected with their installed base.” He continues: “Even though the primary use case in the example I gave is an opportunity to syndicate data externally to appliance manufacturers, there will be an interest in this data in the long haul by other parties. Some of the new entrants, like Google, have a very different view on the value of data, and as they wake up to this opportunity you may see them investing more heavily and creating a sort of platform for home appliance data” (As cited in Kellmereit & Obodovski, 2013, p. 137). The data that can be obtained from IoT technology in the connected home is not more sensitive or important than in the other application domains. However, people have the power and authority in their own home to decide which products and services they want to have installed, and how these are used. Accordingly, the focus of this thesis project will be on the protection of personal data and the possibilities of IoT technology in the connected home.

3. Problem domain and grounding

Along with the potential benefits offered, the adoption of the Internet of Things also raises some concerns. The explosion of sensors, devices and other technologies connected to the Internet naturally result in an increase of data generation and data exchange. “With the development of the IoT, it appears that the physical world is transforming into an information system itself, where data is being communicated between different devices, thus enabling them to sense and decipher the continuous flow of data” (Skaržauskienė & Kalinauskas, 2012, p. 109). IoT applications generally rely on the analysis of personal data in order for them to function properly, which can provoke privacy and surveillance issues. Moreover, the scope and consequences of the enormous increase of connected devices should not be underestimated.

3.1 Privacy and security issues

The IoT relies on the automatic exchange of vast amounts of data, communicated between systems or devices by automatically transferring data over communication networks (Borgohain, Kumar, & Sanyal, 2015). All this data needs to be processed in order for the devices to respond correctly to each other, and to the environment they are in. Although the decoding of the enormous amounts of data is a problem, the bigger issue concerns the information that can be extracted from this data and who can obtain it. Especially the collection and analysis of real-time data in IoT applications may challenge the privacy of the user. The data retrieved at distinct times allows governments, providers or third parties to come into the possession of extra knowledge by cross-examining the data within a specific timeframe (Wong & Kim, 2014). In the sections underneath I will introduce the concept and implications of data surveillance, and express which aspects of data surveillance are of current concern.

3.1.1 Data surveillance

The notion of a ‘surveillance society’ where every aspect of people’s private life is monitored and recorded, still seems like an abstract and paranoid phenomenon to many people; the danger and impact of an increase in surveillance by governments and private sectors is often not acknowledged. One of the reasons that the dangers of surveillance are generally not recognised is because many people think they are only surveilled by cameras. However, a new type of surveillance, data surveillance, is becoming more common and powerful. Even though data surveillance is less visible than video surveillance, it is presumably more intrusive (Stanley & Steinhardt, 2003).

Data surveillance encompasses the observing of people’s online behaviours, and makes tracking and profiling through the exploitation of personal data even more dominant. Edward Snowden revealed that all online actions, such as researching topics of interest, writing personal emails, debating political issues, seeking support for intimate problems and many other purposes that can result in the assembly of private information, are being recorded (Snowden, 2013). Even leisure activities, such as being on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, which are intended to entertain and relax, simultaneously trick people into generating vast amounts of data. Although a specific piece of data about a person is harmless, when enough pieces of similar data are assembled it can result in a detailed and intrusive picture of an individual’s life and habits, and it can almost give the data collector a look into a person’s mind.

3.1.2 Implications

Data has been collected in databases for over a century, but is no longer only in the possession of accountants, analysts and scientists: “New technologies have made it possible for a wide range of people – including humanities and social science academics, marketers, governmental organisations, educational institutions, and motivated individuals – to produce, share,

interact with and organise data. Massive data sets that were once obscure and distinct are being aggregated and made easily accessible” (Boyd & Crawford, 2011, p. 2). This means that not only the government will have access to personal data, but also insurance companies and future employers (Stanley & Steinhardt, 2003). Issues of financial as well as social discrimination could arise.2 The conclusions derived from personal data collection are based

on propensities, which may result in the making of decisions on the basis of assumptions (Mayer-Schonberger & Cukier, 2013). This can lead to bad decision making by organisations, resulting in service denial. Service denial is known to occur in numerous contexts including government licensing, financial services, transport, and even health. There is a chance the individual is not even aware of a decision, or about the basis on which it was made (Mayer-Schonberger & Cukier, 2013).

2 For instance, bank managers could restrict loans to residents of certain areas in a city. In addition, a future employer might not

hire a person based on information about their sexual or political preferences, retrieved by looking at their online behaviour and data. Or if an individual’s data indicates that they are not having a healthy lifestyle or, conversely, are participating in extreme sports, insurance costs might be increased.

Another issue is the distributing of anonymous information. Even though the information is anonymous, it is often fairly easy to de-anonymise it. “In October 2006, the movie rental service Netflix launched the ‘Netflix prize.’ The company released 100 million rental records from nearly half a million users – and offered a bounty of a million dollars to any team that could improve its film recommendation system by at least ten percent. Personal identifiers had been carefully removed from the data. And yet, a user was identified: a mother and a closeted lesbian in America’s conservative Midwest” (Mayer-Schonberger & Cukier, 2013, p. 67).3 This

example illustrates how easy it is to de-anonymise so-called anonymous information. It also points out how information that seems innocent, like film and TV preferences, can reveal detailed information about a person.

3.1.3 Control society

The concept of data surveillance can be compared to Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon, as

described by Michel Foucault: “The major effect of the Panopticon is to induce in the inmate a state of conscious and permanent visibility that assures the automatic functioning of power. So to arrange things that the surveillance is permanent in its effects, even if it discontinuous in its action; that the perfection of power should tend to render its actual exercise unnecessary; that this architectural apparatus should be a machine for creating and sustaining a power relation independent of the person who exercises it; in short, that the inmates should be caught up in a power situation of which they are themselves the bearers” (Foucault, 1977, p. 440).

The functionality of the Panopticon thrives on two aspects. One aspect encompasses the fact that the surveilled person is visible, while the observer remains invisible. The other aspect is a consequence of the first and concerns the asymmetrical nature of surveillance, which is characteristic of an unbalanced power relationship. Both these aspects lead to an embodiment of surveillance: there is no way of knowing whether someone is being observed or not, so the observed person feels and acts as if always being surveilled. Foucault describes this phenomenon as part of the disciplinary societies.

Gilles Deleuze introduces the notion that societies of control are replacing the disciplinary societies. He writes the following: “‘control’ is the name Burroughs proposes as a term for the

3 Research has pointed out that it is possible to identify a Netflix customer 99 percent of the time, by comparing films watched on

new monster, one that Foucault recognises as our immediate future. Virilio also is continually analysing the ultra rapid forms of free-floating control that replaced the old disciplines operating in the time frame of a closed system” (Deleuze, 1992, p. 4). The essential difference between the two systems is that in the case of control societies, surveillance is no longer bound to a specific environment, such as factories, schools or prisons, but, as Deleuze describes, “the corporation has replaced the factory, and the corporation is a spirit, a gas” (Deleuze, 1992, p. 4). The control society therefore increases the invisibility of surveillance and hereby expands the embodiment of surveillance.

3.1.4 Surveillance in a world of connected things and beings

As Deleuze already implied, surveillance nowadays is everywhere, but rarely observed. The emerging Internet of Things is tried to be made invisible by integrating it into buildings, objects and bodies, allowing technology to be more interwoven in our lives than ever (Mann & Niedzviecki, Cyborg: Digital Destiny and Human Possibility in the Age of the Wearable, 2001). “The explosion of computers, cameras, sensors, wireless communication, GPS, biometrics, and other technologies in just the last 10 years is feeding a surveillance monster that is growing silently in our midst. Scarcely a month goes by in which we don’t read about some new high-tech way to invade people’s privacy, from face recognition to implantable microchips, data-mining, DNA chips, and even ‘brain wave fingerprinting.’ It seems as if there are no longer any technical barriers to the Big Brother regime portrayed by George Orwell” (Stanley & Steinhardt, 2003, p. 1). The Internet of Things (and technology in general) is developing at such a speed that adaption of the legal system and the enactment of new laws and regulations have no time to take place. To this day, it is undecided who will have the rights over the data generated by IoTs. Experts announce that privacy is a big problem, but finding or developing the perfect concepts for absolute data protection, privacy and security is probably not feasible (Witchalls & Chambers, 2013). The impact of the IoT in the future will be huge and I therefore find the lack of solutions to solve the aforementioned privacy and surveillance issues worrying.

3.1.5 Building on a worst case scenario

One of the reasons that user profiling, based on personal data, is built on propensities and assumptions, is because it is not always possible to distract useful information from collected data. As described earlier, one of the challenges of the Internet of Things is the decoding of the big amounts of data.

The data people generate is analysed by algorithms, on which a general profile of a person is built.4 A whistle-blower at the Transmediale festival stated that it is absolutely impossible for

the NSA to handle the shear amount of data (Transmediale, 2015). It needs to be emphasised that the cases above, introducing the privacy and surveillance issues, consist partly of worst case scenarios. Boyd & Crawford stated that data sets that were once cryptic are being accumulated and made easily accessible for governmental organisations, education institutions, and motivated individuals. The consequences that can become results of the fact that not only governments have access to personal data, but also insurance companies and future employers, will presumably not affect most of the general public (Boyd & Crawford, 2011). Stanley and Steinhardt increase this paranoia by explaining that new technology is invented to invade people’s privacy, in order to feed a ‘surveillance monster’. There is no doubt that data collection and exploitation are used for profiling, however, most of the scenarios described above are worst case scenarios that will not affect a big percentage of people.

Nonetheless, I think the enforcement of paranoia (when for instance talking about a

‘surveillance monster’) is a concern, since it emphasises the embodiment of surveillance. The people that are aware of what their personal data can provoke, might feel unsafe or spied upon online, even if they are conscious of the probability of these consequences becoming a reality. Conversely, there is a concern, as Smith points out, regarding people that are incautious or uninformed when it comes to privacy and security issues. Moreover, unlike desktop and mobile computing platforms where security has been an open concern for many years now, embedded software is notoriously buggy, unaudited and potentially very dangerous (Smith, Physical: Home, 2015). The uncertainty regarding the privacy laws of the emerging Internet of Things is another concern. Until privacy laws have been set, companies have ownership and control over their users’ personal data. Moreover, since IoT technology can collect information on one’s physical functions and the use of devices at home, and more importantly the relation between those, there is a possibility to derive a detailed impression of an individual’s life. The aim of this thesis project is therefore to design on the context of a worst case scenario in the unknown future of surveillance in a connected world. A slight notion of paranoia regarding the surveillance society will be implemented in the execution, not with the aim to enforce the embodiment of surveillance, but, on the contrary, to raise awareness and stimulate reflection on the implications of the IoT.

4 Data mining algorithms consist of a set of queries and calculations that create a data mining model from data. The algorithm

3.2 Breadth and scope

Comparing the traditional Internet to the emerging Internet of Things, the distinctions are immediately apparent. The data networks of the traditional Internet have been over provisioned: they are built with more capacity than is required for the amount of information that is needed. This architecture of the Internet was developed before people had envisioned to connect billions of devices to the Internet (daCosta, 2013). Now, a new era of ubiquity is approaching, which will consist of billions of embedded electronic measuring devices connected to the Internet, and where humans are becoming a minority as generators and receivers of the information that is being communicated between these devices (Evans, 2011). “Extending this thinking, simply scanning for hundreds of billions of IPv6 addresses would take literally hundreds of years. It is one thing to put addresses on nearly a trillion devices, but quite another to find and manage one device out of that constellation” (daCosta, 2013, p. 72). As the Internet of Things revolution advances, the challenges that are evident now will only become more severe. Moreover, the incredible breadth and scope of new technology, and the uncertainty of the consequences, will leave people feeling overwhelmed and unprepared.5

Accordingly, I find it crucial that people gather insight and control over ubiquitous technology, in furtherance of stimulating IoT technology to be more accessible and closer to the user, in contradiction to the current scenario where technology is dominated and controlled by governments and private corporations.

5 Another concern is that the billions of embedded electronic devices and gadgets, that are a result of the unimaginable scope of the

IoT, are likely to be outdated in a couple of years. Outdated devices will constantly need to be replaced with new devices, resulting in big amounts of electronic waste.

4. Conceptual discovery

4.1 Sousveillance

If the surveillance and privacy issues that are consequences of the Internet of Things will not be solved, a worst case scenario could be that the world will turn into an Orwellian Panopticon, in which every thought or action is recorded. An act of dissidence against the spying eyes of the surveilling government is ‘sousveillance’, a term first coined by Steve Mann in 2002 (Mann, “Sousveillance” Inverse Surveillance in Multimedia Imaging, 2004). Sousveillance can be described as a counteraction of surveillance and inherits its name from the French words for sous which means below and veiler to watch. The name suggests that surveillance is carried out by people in low places, rather than governments and the private sector in high places (Mann, Nolan, & Wellman, Sousveillance: Inventing and Using Wearable Computing Devices for Data Collection in Surveillance Environments, 2003). The concept of sousveillance is to empower people to access and collect data about their observer, and by doing so, neutralise surveillance. This method of contra surveillance leads to a distortion of the Panopticon; the invisible is made visible, resulting in a decrease of asymmetry regarding the power relationship. Sousveillance can also be used as a form of personal space protection, which resonates with Gary Marx’s proposal to escape surveillance through non-consent and interference techniques that block, distort, mask and refuse the collection of information (Marx, 2009). Two examples that employ this method of sousveillance are described in the chapter with related work (see Chapter 5.2).

4.2 Becoming fog

Sousveillance as a form of personal space and data protection can be achieved through data obfuscation, by applying techniques such as blocking, distorting, masking or refusing the collection of information by governments or data-mining companies. The consequence of this method can be described as creating fog, which can be regarded as a vital response and interference of the imperative of transparency, that control imposes: “Haze disrupts all the typical coordinates of perception. It makes indiscernible what is visible and what is invisible, what is information and what is an event. Fog makes revolt possible” (Tiqqun, 2010, p. 49). A proposal to become ‘fog’ as an act of sousveillance, by creating opacity zones within the realm of surveillance in the Internet of Things, is fruitful in the sense that it will not only increase the feeling of safety, but will additionally stimulate creativity and experimentation. A suggested method to create ‘fog’ in one’s home is to consider hacktivism or hacking as

an act of sousveillance. In this case, Do-It-Yourself as a method of hacking and as an act of sousveillance is an interesting direction, since it authorises people to regain control over the data they generate, but it also empowers them to exploit their talents, realise their visions and share this with a community joining forces.

4.3 Hacktivism and hacking

The term ‘hacking’ should not be confused with ‘cracking’. Eric Raymond, the author of

The Cathedral and the Bazaar (Raymond, 1999), explained this difference by making an

appropriate distinction between hackers, who build things, and crackers, who destroy things (Von Busch & Palmas, 2006). The term ‘hacktivism’ was first coined in 1995 by Jason Sack, and is a contraction of the words ‘hacking’ and ‘activism.’ Decentralising control and empowering will are the main purposes of hacktivism, and are generally achieved by “exploring the limits of what is possible, in a spirit of playful cleverness” (Stallman, 2002, para. 8), or “the beating of a system through intellectual curiosity” (Von Busch & Palmas, 2006, p. 29). The exploration of these limits is done in different ways, depending on the goal of the hack, but it mainly builds on the idea of customisation. However, hacking goes beyond customisation. It instead focuses on the direct interventions in the functional systems and operations of a machine or device, to make technology work the way one wants. This can be achieved by using parts in unexpected ways, or making projects by building on those of others. By this means, the domestic environment can be reclaimed and reshaped in the way the hacker envisions it. The goal is not necessarily to create something unique, but rather to use parts in unanticipated ways and to create cross-over techniques, in order not to be forced to adapt a defined way of using technology. However, the reclaiming of authorship of a technology, by encouraging transparency and unexpected practices, can also be a purpose of hacking (Von Busch & Palmas, 2006). Arduino is a piece of hardware that has these particular qualities, and additionally has the ability to serve as a possibility to hack into the edge technology layer, described in the infrastructure of the Internet of Things.

The hacker ethos is based on collaboration and the sharing of information. Through hacking, the purpose of a technology can be transformed and re-appropriated by building on existing code, or a new commons can be shared for everyone to explore and augment. This ethic is grounded in the Do-It-Yourself (DiY) culture, and evolved into the academic hacking subculture with the introduction of computers. The software on the computers then was open source and was shared amidst users and programmers. Academics discovered the potential of hacking and reusing code to circumvent unwanted limitations. Hacking, therefore, can be regarded as a “critical as well as a playful activity circling around a DiY approach to the means for our

interaction with the world. A hack can be seen as a deeper intervention of customisation” (Von Busch & Palmas, 2006, p. 30).

4.4 Do-It-Yourself

As the term Do-It-Yourself implies, it can be defined as an activity in which amateurs make products or services for their own purposes, instead of buying these from professional retailers that offer finished products. The activity of DiY validates the creative nature of people, and provides feelings of ‘being their own boss’ (Hoftijzer, 2009).

Ever since the introduction of the first computers DiY has existed, but it was then considered hacking as it involved the customisation of computers and software. DiY nowadays thrives on giving people the opportunity to create personalised artefacts or to customise existing applications to fulfil their visions. Leadbeater and Miller state that the customisation aspect of DiY establishes “a form of everyday resistance to the alienating effects of contemporary society, which is characterised by excessive consumerism, globalisation and economic inequalities between persons and groups, alienating us from our environment and ourselves” (as cited in Uckelmann et al., 2011, p. 38). Although these aspects are also important for DiY practices regarding new technology at home, the main advantage is to give people back the control over their own data and let them decide how to use it for context-awareness at any time. Hacking as a DiY practice could provide opportunities to give people back their control, following the five aspects of hacking from Anna Galloway:

- Access to a technology and knowledge about it (‘transparency’) - Empowering users

- Decentralising control

- Creating beauty and exceeding limitations

- Using the intelligence of many for innovation, since the hacker ethic is based on collaboration, sharing and the reuse of code (Galloway, 2004).

5. Related work

In addition to the state of the art of the IoT (see Chapter 2), various examples of related work are described in this chapter. Different home automation products and services, such as the Nest Thermostat and Homey, along with an example of a self-made home automation project, are explored. Additionally, the works AdNauseam and Jennifer Lyn Morone, Inc. were analysed and described, in order to provide a better understanding of sousveillance as a method for personal data protection. Furthermore, several online DiY platforms and websites with the focus on IoT projects were examined to gain insight into the state of the art in this subfield, alongside the functionality and design of these platforms.

5.1 Home automation products and services

5.1.1 Nest Thermostat

The Nest Thermostat (fig. 2) is a smart thermostat that is able to recognise patterns regarding a user’s temperature preferences over time, and by this means aims to save energy in the domestic environment. The Nest Thermostat is capable to detect when a user has left the home, and, subsequently, adapts the temperature. Furthermore, the Nest app provides the user with possibilities to control the thermostat with the use of a smart phone (Nest, 2014). The Nest Thermostat is an example of a popular smart home product, and substantiates the advantages of home automation in the fields of heat, light, presence and motion.

However, it is a product that relies heavily on the data generated by its users. As such, it can be stated that the Nest Thermostat is a related work, as well as an example of a home automation project linked to a data mining company (considering the fact that Google bought the Nest Thermostat and Nest in early 2014). Sacha Segan states the following: “The Internet of Things is at an early stage. A clear trend from CES 2014 was that over the next three years, we’re going to try to connect everything to everything else. Phones are being reinvented as “sensor hubs” that collect data, interpret and analyse it. There’s a land grab going on for the best expertise and infrastructure in this new, growing field, and Google wants to have a strong position early” (Segan, 2014, The “Internet of Things” is at an early stage section, para. 1).

5.1.2 Homey

Homey is a voice-controlled home automation system, enabling users to control many different applications in the home; from lights to music, from temperature to TV. The service consists of multiple wireless technologies enabling connections to wireless devices, and congregates these on a single platform which connects to the Internet (Øredev, 2015). Homey is an interesting example of a related work since it includes an interactive flow-editor, empowering the user to ‘program’ different parameters to respond to each other, without the use of code. By this means it aims to increase the accessibility for the everyday user. However, the accessibility remains limited considering the fact that the user is restricted to controlling the application layer of the system. Homey offers another interesting approach to increase the accessibility and influence of the everyday user by providing its own app store, in which apps of other users can be found. By this means, it intends to increase collaboration and sharing between users in anoriginal and innovative way (Athom, 2014). Nevertheless, it remains unclear how safe these (self-made) apps are, and to what extent personal data is protected.

5.1.3 DiY home automation

The following section describes a project of a home automation enthusiast and is chosen as a related work, because it gives insight into the opportunities and capabilities of hacking and constructing self-made home automation projects with the use of an Arduino. Moreover, it indicates the possibility of replacing products and services that are usually distributed by governments and data mining corporations with self-made projects, which decreases the exposure of personal data to these aforementioned companies.

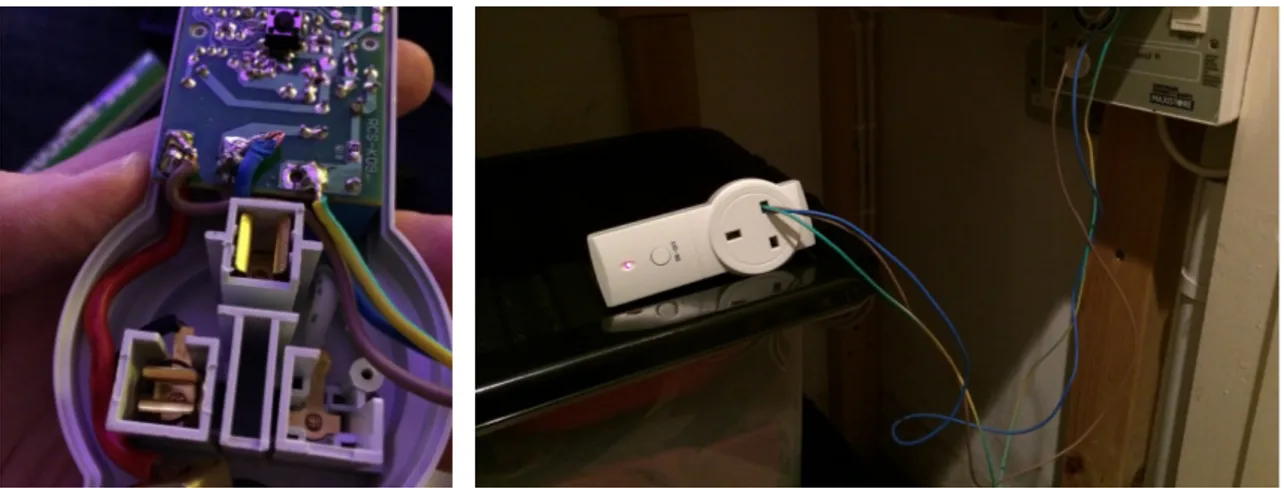

“I made a quick web interface to turn stuff on and off from the Internet. I put the plug sockets on loads of things in my house (fig. 3) - various lights, appliances (like my espresso machine), and I even ripped one of them apart and connected it to my boiler so I can control my heating. It’s been a fun project replicating the functionality of Internet of Things consumer products like the Belkin WeMO system (£40 per socket) and the Nest Thermostat (around £200). I hack in new features when I have time or get an idea - e.g. I’ve set the lights to come on just before sunset (a different time every day), in the winter I have the heating come on automatically when I leave work so the house is warm and my coffee machine is ready by the time I get back! I’ve also added in a few sensors, so I can turn off the lights if there’s nobody in the room etc. It’s also handy when I’m away from home - I can turn off the heating, and set the lights on random timers for security” (Smith, Physical: Home, 2015).

5.2 Data sousveillance

5.2.1 AdNauseam

Sousveillance can be used as a method to protect personal data, which resonates with Gary Marx’s proposal to escape surveillance through non-consent and interference techniques that block, distort, mask and refuse the collection of information (Marx, 2009) (see Chapter 4.1). A related work and example of sousveillance that employs this method is the browser extension

AdNauseam (which only works when AdBlock is installed), which automatically and blindly

clicks all the ads on the websites users visit. Moreover, it registers a visit on the ad network’s database. Since every single ad is clicked, user profiling, targeting and surveillance become unprofitable. The purpose is not only to obfuscate browsing data and protect users from surveillance, it also “amplifies the users’ discontent with advertising networks that disregard privacy and facilitate bulk surveillance agendas” (Nissenbaum, Howe, & Mushon, 2014, para. 2). Fig. 3: Hacked plug sockets (Smith, Andy Smith: Digital Media Portfolio, 2015)

5.2.2 Jennifer Lyn Morone, Inc.

Another example is Jennifer Lyn Morone, Inc., which is an act of ‘extreme capitalism’, as she describes it herself. “Jennifer Lyn Morone, Inc. has advanced into the inevitable next stage of Capitalism by becoming an incorporated person. This model allows you to turn your health, genetics, personality, capabilities, experience, potential, virtues and vices into profit” (Morone, 2014, Life Means Business section). The concept is to track one’s own data at all times by recording online behaviour, mobile behaviour and offline behaviour with the use of an Arduino and wearable sensors. “By mining, collecting and indexing as much data about oneself as possible, you can gain valuable insights and intelligence specific to your operation” (Morone, 2014, Why Are We Building DOME? section). In Morone’s case sousveillance is applied to protect personal data by collecting and keeping ownership over it. The reason behind the work is not necessarily based on the implications of surveillance, but rather those of capitalism. AdNauseam and Jennifer Lyn Morone, Inc. are interesting examples, considering the fact that they highlight different tactics of sousveillance in the digital Panopticon, both relying on the aspect of obfuscating personal data. AdNauseam obfuscates data through multiplication and distortion, and by this means negates the reliability of the generated data. Conversely, Jennifer Lyn Morone, Inc. employs sousveillance by containing and shielding the generated data in furtherance of obfuscating it. The sousveillance tactic AdNauseam applies is suitable when the purpose is to protect generated data from being used for profiling in order to prosecute targeted advertisements, because, as described before, it does not only make the generated data unprofitable, but it also emphasises the users’ discontent. Moreover, AdNauseam employs a tactic that is well-chosen, as well as obvious: AdNauseam is granted with a straightforward possibility to multiplicate and distort data, since there is the potentiality to automatically click every ad on visited websites. The opportunity to practice multiplication and distortion as a tactic for Jennifer Lyn Morone, Inc.’s example is less suitable, since there are no apparent opportunities to generate big amounts of random data. Furthermore, the generated personal data in this example is very sensitive, containing information about a user’s lifestyle, habits and body functions. It is therefore advisable to completely shield the generated data in furtherance of entirely protecting it. As such, it can be stated that different purposes of sousveillance call for different tactics of data obfuscation, which the examples of AdNauseam and Jennifer Lyn Morone, Inc., illustrate very well.

5.3 Online (DiY) platforms

The different online DiY platforms that are elaborated in the following section are chosen to shed light on various manners to support and motivate hacking and DiY in a range of fields, along with providing information on the state of the art of (self-made) IoT projects.

Postscapes, for instance, is an online platform that tracks and gathers the most recent

developments of the IoT by displaying projects and devices, sorted in different categories such as body, home, city and industry (Postscapes, 2015). Along with the clear and structured manner of presenting the projects, Postscapes gives an excellent overview of the possibilities and developments in the realm of the IoT. Instructables also offers an overview of IoT projects and tutorials, supported by Intel, on one of the sections of the platform (Instructables, 2015). Instructables was chosen as a related work due to the fact that the platform provides step-by-step tutorials, created by the everyday user, for the everyday user, and by doing so supports DiY in many different fields. However, the lack of structure in the uploading process, along with the distracting design of the website, result in tutorials that are often chaotic and difficult to follow. Kickstarter, just as Instructables, showcases projects in a range of categories. The purpose of Kickstarter, however, is to provide users with a chance to pitch and get their projects funded for further development, as opposed to providing tutorials on projects (Kickstarter, 2015). Kickstarter, as a related work, provides insight into the uploading process and methods of (crowdfunding) projects. In addition, the platform indicates the high level of creativity and innovation of projects created by, among others, everyday users in the field of IoT, alongside many other fields.

In furtherance of making DiY a successful practice, numerous platforms grant a place for collaboration and community building, in different manners. Instructables, for instance, supports collaboration by providing tutorials. Other platforms, such as Github and Stack

Overflow, encourage collaboration between users through the exchange of code. Github offers

a place for collaboration, code review and code management for open source and private projects, by providing users with opportunities to share their projects with the necessary code included (Github, 2015). Stack Overflow is another platform concentrated on code review and code management. However, instead of sharing code in the form of projects, Stack Overflow offers a question and answer based format for professional and amateur programmers to solve programming problems through the exchange of code (Stack Overflow, 2015). Stack Overflow and Github are related works that highlight the importance of collaboration, by pointing out that amateur programmers are able to solve programming issues with the help of other (more experienced) users, based on a question and answer method, and the sharing of code.

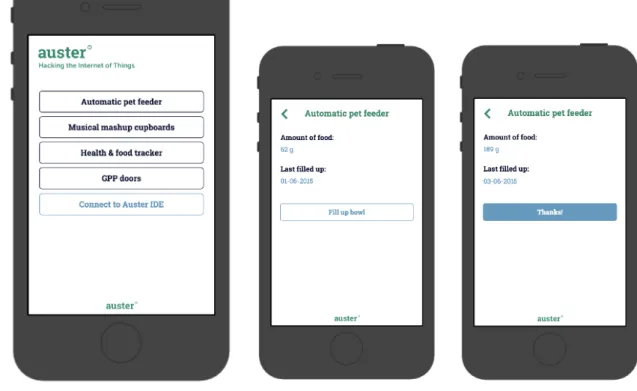

6. Role of the interaction designer

In the introduction is described how there are no longer any technical restraints to create many bizarre applications, presented in science fiction films and books. The increasingly popular maker culture has the potential to enable people to turn these sci-fi inspired applications into a reality. The chapter about the conceptual discovery pointed out that hacking as a DiY practice (see Chapter 4.3 and 4.4) is a fruitful method to give control back to users and to help them reclaim the domestic environment through the use of ‘transparent’ tools and customisation. This empowers the user to construct numerous applications and prevents them from being enforced to buy IoT applications from the government or corporations alike. The benefits of hacking as a DiY practice, as part of the maker culture, emphasise the potentially shifting role of the interaction designer: where it was once the task of an interaction designer to create ideas, products, and services for the future society, it has transformed to reflect and act on the context of the development of new technology, and to create a fitting environment or platform for this context. The role of the interaction designer in this case is to understand and design for the context of the privacy and surveillance issues of the IoT and its implications, along with the concerns regarding the user’s involvement. The proposed direction is to create a platform which permits the everyday user to create ‘fog’ in their own home, by performing an act of sousveillance. A place should be designed where people have “the right to privacy; the right to be calm when they require it; the right to make autonomous decisions and control their surrounding electronic environment and the right to be the master of their own identity in machine systems” (as cited in Uckelmann et al., 2011, p. 30). This can be achieved by applying hacking as a method: by providing the user with the right tools, inspiration and knowledge, they are given the opportunity to construct and control their own home automation projects. Accordingly, it permits the user to make a range of projects, from automatic pet feeders to secure health trackers, but also projects inspired by their favourite sci-fi book or film, while at the same time being assured that these are created in a publicly engaged and safe environment.

7. Research methods

7.1 Research Through Design

Research Through Design (RtD) is “a research approach that employs methods and processes from design practice as a legitimate method of inquiry”, and was the chosen approach for this project (Zimmerman, Stolterman, & Forlizzi, 2010, p. 310). This RtD approach has been employed by applying several different research methods throughout the design process, consisting of both sign-based research, as well as other forms of research. Obrenović stated the following about de-sign-based research: “While design itself adds discipline and professional attitude to tacit, implicit, and intuitive knowledge and skills, design-based research may be viewed as an attempt to increase awareness of such knowledge and to support, capture, generalize, and share this knowledge beyond the design community” (Obrenović, 2011, p. 59). The different practiced research methods have occurred in an iterative manner, which can be explained by the fact that “design problems are often full of uncertainties about both the objectives and their priorities, which are likely to change as the solution implications begin to emerge. Problem understanding evolves in parallel with the problem solution, and many components of the design problem cannot be expected to emerge until some attempt has been made at generating solutions” (Željko Obrenović, p. 57). The following section aims to chronologically describe my design process in more detail, and introduces the different methods implemented in each phase in order to give more insight into the decisions made during this process.

7.2 Design process

7.2.1 Field research: first round

Ethnographic research, as David R. Millen states, typically includes field work or field research. The aim is, as described by Blomberg and her colleagues, “to provide designers with a richer understanding of the work settings and context of use for the artefacts that they design” (as cited by Millen, 2000, p. 280). The first round of field research concentrated on exploring and understanding the context of the subject of this thesis project and was carried out by firstly attending the

Transmediale festival in Berlin, Germany (Transmediale, 2015). The topic of the Transmediale festival was ‘Capture All’, fostering a critical understanding of how the development of technology is influencing daily life, now and in the near future. Furthermore, I was present at different talks concerning the Internet of Things at Media Evolution City in Malmö, Sweden (Media Evolution City, 2015). Alongside the infrastructure of the Internet of Things, the main topics discussed at these talks were the security and privacy concerns. The knowledge gained from this first round of field research permitted me to establish a basic understanding of the state of the art of the IoT, particularly regarding the concerns that are consequences of this emerging technological

development. Both events spelled out that many of these concerns are related to the fact that the infrastructure of the IoT (and frequently technology in general) is controlled by governments and corporations alike. The consequences of the IoT were taken as a starting point and grounding for this thesis, and it was determined that the solution would be focused on the decentralisation of control, by enabling technology to be more accessible for the general public. At this stage the first version of the research question was formulated, and the idea of creating an online DiY platform and a construction kit was formed. However, the manner in which these would be developed and framed were still undecided.

7.2.2 Literature-based research

Literature-based research as a method consists of reading through, analysing and sorting literatures “in order to identify the essential attribute of materials. The conduction of literature-based

research consists of grasping sources of relevant researches and scientific developments and understanding what predecessors in a specific field have achieved, alongside the progress made by other researchers” (Lin, 2009, p. 179). Literature-based research has been conducted throughout the design process, but has generally been employed to establish a better understanding of the background and state of the art of the IoT, along with clarifying the problem domain. The chapters about the background, and the problem domain and grounding are therefore largely dependent on my interpretation of scientific articles and specialised literature in the form of digitised books. After having researched the privacy and surveillance issues regarding the IoT in more depth, along with the consequences of the lack of the user’s involvement, I was able to refine the research question. The formulation of the research question was followed by the exploration of literature focused on escaping surveillance and decentralising control as methods and onsets for possible solutions, described in the conceptual discovery. Especially the description of Von Busch & Palmas of hacking and hacking as a DiY practice (see Chapter 4.3), combined with the findings on sousveillance (see Chapter 4.1), provided a grounding and a suitable framing for the project (Von Busch & Palmas, 2006). In addition to the scientific and specialised literature, philosophic literature was consulted to establish an extra layer of understanding and a different perspective on the topics discussed in the conceptual discovery.

7.2.3 Analysis of related work

Alongside the literature-based research, part of the conceptual discovery consists of an analysis of related works. Two critical design pieces, AdNauseam and Jennifer Lyn Morone, Inc., that focus on sousveillance through data obfuscation, were analysed. Critical design, as Dunne and Raby describe is “a form of design that questions the cultural, social and ethical implications of emerging technologies” (Dunne and Raby, 2015, para. 27). The analysis of these two works have prompted

inspiration for the overall idea.

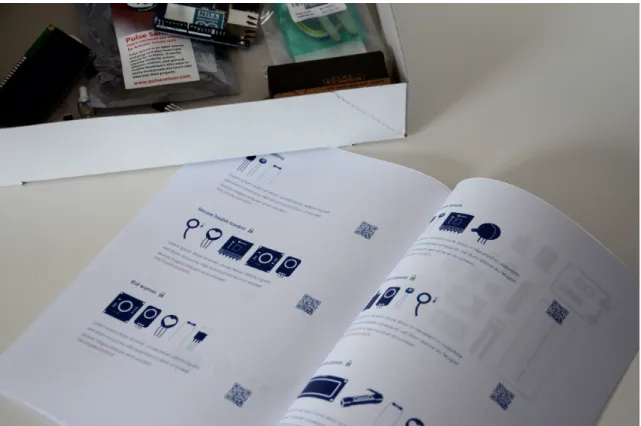

Furthermore, several Do-It-Yourself platforms, and platforms which focus on the progression of the IoT provided new insights and inspiration for the project. The platforms I reviewed were Postscapes, Instructables, Adafruit, Kickstarter, Github and Stack Overflow. The review of these platforms was conducted in the process of sketching the design and functionality of the online platform, and resulted in an understanding of the strengths and weaknesses of each of the aforementioned platforms. I realised that my concern with several platforms, such as Instructables, Kickstarter and Github, is the lack of overview as a result of the many categories they try to cover. The main inspiration for the design of the Auster platform was obtained by reviewing Kickstarter, whereas Instructables has aided me in developing the functionality of the Auster platform. The exploration of Github and Stack Overflow have contributed to developing aspects related to collaboration and the sharing of code during the sketching and ideation phase of the online platform. In furtherance of making informed decisions on the inclusion of tools in the Data Obfuscation Kit, inspiration was obtained from analysing websites that offer construction kits, such as Arduino and Adafruit. In addition, I studied tutorials on home automation projects to determine what the most used sensors and actuators in this field are. Moreover, I have described and compared the different specifications of the Arduino and Raspberry Pi in order to decide which hardware to adopt for the base of the construction kit (see Appendix).

7.2.4 Field research: second round

The analysis of related work, and the sketching and ideation phase of the Auster platform and the construction kit were followed up by another round of field research. An IoT conference at Ideon in Lund, Sweden was attended, which strengthened my knowledge about hacking and the importance of the user’s involvement regarding IoT at home (Ideon, 2015). When the audience at one of the talks of this conference was asked if anyone had automated homes or IoT applications in their home, a fair share of people raised their hands. When they were asked how many of them built and programmed these themselves, all of them raised their hands. Needless to say, this is a biased audience, but it was a validation of the chosen subject and confirmed the interest and feasibility of constructing home automation projects. To validate the subject further, I attended a talk by Peter Sunde, best known for being a co-founder and ex-spokesperson of The Pirate Bay, at STPLN in Malmö (STPLN, 2015). In his presentation he sketched and discussed his view on the future, which turned out to be a dystopian one. He expressed his concerns about a world in which the Internet is becoming more and more centralised, and underlined the importance of online collaboration. Sunde’s views on online collaboration made me, once more, realise the importance of the community and collaboration aspects of the Auster platform. Moreover, during Sunde’s talk I got introduced to a microdonations service called Flattr, which was later implemented in the feedback system of the Auster platform.

In addition to attending different events, I carried out an in-depth interview with Andy Smith, who has been building IoT home automation projects with the Arduino for a period of five years. Smith has, among other things, studied web development, has a BA in Digital Media and now works as a software developer. According to Mack, Woodsong, et al. “the in-depth interview is a technique designed to elicit a vivid picture of the participant’s perspective on the research topic. During in-depth interviews, the person being interviewed is considered the expert and the interviewer is considered the student” (Mack, Woodsong, MacQueen, Guest, & Namey, 2005, p.29). The questions asked in the interview gave insight into the possibilities of constructing home automation projects with the use of an Arduino, and the benefits of connecting these to the Internet. Smith gave several examples of his projects, along with describing the methods and technology used for constructing these. Furthermore, I asked Smith about his opinion on the construction of self-made home automation projects as a possible solution to the privacy and surveillance issues of the emerging IoT. In his answer he clarified that the privacy and surveillance issues are a “massive issue” and will only become more prevalent and dangerous. Moreover, he stated that self-made projects are a possibility to mitigate the risk by applying methods of security through obscurity. After introducing Smith to the idea of an online DiY platform consisting of tutorials in furtherance of sharing knowledge to a community, he indicated his desire to share his projects and knowledge. However, he argued that most of the uploading processes on platforms such as Instructables take too much time. This argument established an awareness of the need for a well structured and easy uploading process. The interview with Smith was helpful, since it did not only confirm the feasibility of the creation of home automation projects with the use of Arduino, but his perspective on the privacy and surveillance issues of new technology, which he is occasionally confronted with at his job, also became apparent (Smith, Physical: Home, 2015).

7.2.5 Prototyping: first round

After I had gained insight into the different conceptual approaches, the weaknesses and strengths of several DiY platforms and the possibilities of self-made home automation projects, a first lo-fi prototype of the Auster platform was created. Van Buskirk and Moroney explain that “a prototype can be thought of as a representation or mock-up of a proposed solution to a design problem, regardless of the medium. The typical use of prototypes is for usability evaluations conducted in the design phase of a project” (Van Buskirk & Moroney, 2003, p. 613). The main objective of the first prototyping round was to focus on the functionality of the platform, in order to make it suitable for user testing. Therefore, the prototype was still ‘unpolished’ in furtherance of encouraging test participants to provide feedback about the solution or artefact being evaluated (Van Buskirk & Moroney, 2003). Alongside the prototype of the platform, a first proposition regarding the inclusion of tools in the construction kit was made. However, no tangible prototype had yet been made at this stage. Furthermore, a prototype of an automatic pet feeder was developed as an example of a home

automation project. This prototype was uploaded as a tutorial on the Auster platform, in furtherance of making it available for user testing.

7.2.6 User testing: first round

The first round of user testing was carried out to examine the feasibility of constructing home automation projects. For this round of user testing two types of test participants were asked to make the automatic pet feeder prototype on basis of the Auster platform prototype and the first proposition of the Data Obfuscation Kit. One of the participants was a 23 year old girl, who worked as a graphic designer, and had a bit of experience with using the Arduino. The other participant was a 61 year old man, whose occupation was being a medical doctor. This participant had no experience in using Arduino. Both participants were presented with the tutorial of the automatic pet feeder on the Auster platform and were given an Arduino board and the necessary tools to construct this particular project. The results extracted from this round of user testing were obtained by carefully observing the participant, and by afterwards discussing the difficulties that became apparent during the testing. The main findings of this round of user testing indicated that beginning users require a basic understanding of the technological components, before constructing projects on basis of the tutorials on the Auster platform. Additionally, the importance of collaboration and the community aspect of the online platform became apparent, since with a bit of help, the test participant without experience was able to successfully construct the project. The participant with a bit of experience was found to be capable of following the tutorial on the platform without additional help.

7.2.7 Prototyping: second round

The first round of user testing was followed by a second round of prototyping. During this round of prototyping, the functionality of the platform was improved, alongside enhancing the aspects regarding community and collaboration, based on the findings of the user testing. However, the main focus during this phase was to improve the design and aesthetics of the online platform. Additionally, a tangible prototype of the Data Obfuscation Kit was created along with a guide containing information and instructions on the functionality and the installation of the technological components, on basis of the results obtained by the first round of user testing. In addition to the prototypes of an online platform and a construction kit, a prototype for an app was created in furtherance of connecting the home automation projects to the Internet. Two online services, Parse and Temboo were used to connect Arduino projects to the Internet, and control these with the use of a smart phone (Parse, 2015) (Temboo, 2015). The experiments and prototyping with Parse and Temboo shed light on the advantages and disadvantages of both services, and enabled the development of the idea and functionality of the app.