What’s the plan? Impact of a

pandemic on people in supply

chain management:

MASTER THESIS WITHIN Business Administration

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: International Logistics and Supply Chain Management NUMBER OF CREDITS: 30

AUTHOR: Sven Bremer and Albin Larsson TUTOR: Dr. Elvira Kaneberg

JÖNKÖPING May 2021

Acknowledging experiences

of COVID-19 to create more

resilient supply chains

i

Master Thesis in Business Administration

Title: What's the plan? Impact of a pandemic on people in supply chain management

Authors: Sven Bremer and Albin Larsson Tutor: Dr. Elvira Kaneberg

Date: 2021-05-24

Supply Chain Resilience, Risk Management, Pandemics, Disruption, Global Supply Chain Management

Abstract

Background: By focusing on efficiency, supply chains became increasingly extensive and complex during the past years. This led to higher vulnerability, and the COVID-19 pandemic caused an incomparable impact on global supply chains. Consequently, researchers demanded more investigation of the pandemic to prepare for future disruptions and create more resilient supply chains.

Purpose: This thesis examines the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on operations in supply chain management. It seeks to understand the challenges during a pandemic and acknowledge experiences to create more resilient supply chains in the future.

Method: We applied an explorative single-case study with a focus on individuals working in SCM-related departments. Therefore, we conducted semi-structured following theory-guided - and maximum-variation sampling to get a holistic view. Following an abductive approach, we constantly compared theory and empirical findings to further expand on previous theory about supply chain resilience. We also increased the validity by triangulating our findings with quantitative secondary data.

Conclusion: The results of this study show that a pandemic causes multiple reoccurring disruptions to supply chains. Companies have to react flexibly to adapt to the fast-changing environment, but the extensive supply chains hinder fast reactions. The findings of this study allow making different theoretical and managerial implications to create more resilience in supply chains to face future pandemics and other disruptions.

ii

Acknowledgements

This thesis would not have been possible without the help of many individuals who supported us with valuable insights and inspired us. We would like to take the opportunity to thank these people.

First of all, we want to show our deepest gratitude to all of our interview participants who shared their experiences and extensive knowledge. Without them, this study would not have been possible.

Secondly, we would like to extend our sincerest thanks to Dr Elvira Kaneberg for her invaluable support and constructive feedback. We would also like to thank our seminar group for their valuable remarks and helpful advice to improve our thesis.

In addition to that, we cannot leave Jönköping University without mentioning our classmates and the people of the university who made our time in Jönköping unforgettable.

Finally, our deepest gratitude goes to our friends and family for the relentless love and support during this challenging time. Not only have they emotionally supported us, but they have also provided practical remarks and insightful suggestions. Primarily, we would like to thank our parents, who made it possible for us to pursue our own paths.

iii

Table of Contents

1

Introduction ... 1

Problem Description ... 3 Purpose ... 4 Delimitations ... 42

Literature review ... 5

Supply Chain Management and the Issue of Globality ... 5

Risk Management as a Precondition for Resilient Supply Chains ... 6

2.2.1 Challenges of Supply Chain Risk Management ... 8

2.2.2 Characterization of Supply Chain Disruption Risk ... 9

2.2.3 The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Supply Chains ... 11

2.2.4 Disruption Propagation in Supply Chains ... 12

The Resilience of Supply Chains ... 13

2.3.1 Phases of Supply Chain Resilience ... 14

2.3.2 Elements of Supply Chain Resilience ... 15

2.3.2.1 Flexibility...16

2.3.2.2 Collaboration ...17

2.3.2.3 Visibility ...17

2.3.2.4 Supply Chain Risk Management Culture ...18

The Theoretical Framework of this Study ... 19

3

Methodology ... 21

Research Philosophy ... 21 Research Approach ... 22 Research Design ... 23 Data Collection ... 24 Sampling Strategy ... 26Data Coding and Analysis ... 27

Quality of the Research ... 32

Limitation of Methodology ... 33

iv

4

Findings ... 35

Uncertainty as the Major Challenge During a Pandemic ... 35

Issues Related to Flexibility ... 37

4.2.1 Long Supply Chains and Slow Reaction Time ... 37

4.2.2 Reduced Workforce ... 38

4.2.3 Transportation Rotation Issues ... 39

Flexibility Measures during the Pandemic ... 39

4.3.1 Safety Stock and Warehousing ... 40

4.3.2 Rerouting, Prioritizing and New Solutions ... 41

The Influence of Remote Work on Collaboration ... 42

4.4.1 Internal Collaboration ... 43

4.4.2 External Collaboration ... 46

SCRM Culture ... 48

4.5.1 Listening to Employees and Willingness to Change ... 48

4.5.2 Personal Resilience Traits ... 50

4.5.3 Learnings from the COVID-19 Pandemic. ... 51

Visibility and Process Re-evaluation ... 52

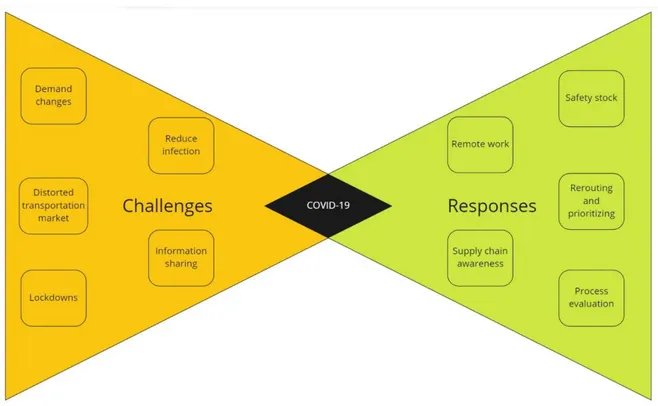

Challenges and Responses related to COVID-19 ... 54

5

Analysis ... 55

Supply Chain Resilience Phases During a Pandemic ... 55

Flexibility ... 57

5.2.1 Redundancy and Safety Stock ... 58

5.2.2 Resourcefulness ... 59 Collaboration ... 60 5.3.1 Internal Collaboration ... 60 5.3.2 External Collaboration ... 61 SCRM Culture ... 63 5.4.1 Remote Work ... 63

5.4.2 Empowering the Employee and Personal Resilience Traits ... 65

5.4.3 Awareness of Supply Chain Management ... 66

5.4.4 Innovation ... 67

v

Visibility ... 68

Supply Chain Resilience in the Context of a Pandemic ... 69

6

Conclusion ... 71

Managerial Implications ... 74

Theoretical Implication ... 75

Ethical Implications ... 76

Limitations of the Study and Further Research ... 76

7

References ... 78

8

Appendix ... 91

vi

List of figures

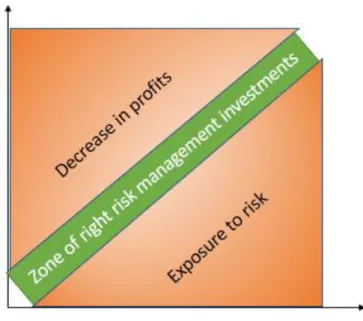

Figure 1: Zone of right risk management capabilities ... 9

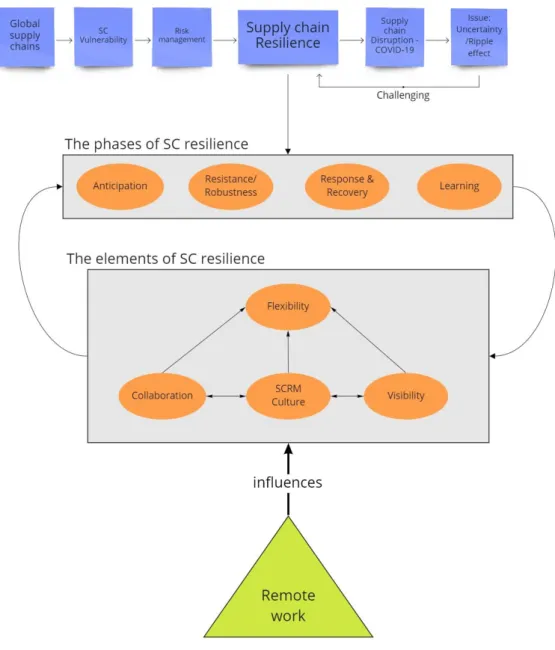

Figure 2: Supply chain resilience framework ... 20

Figure 3: Research approach ... 24

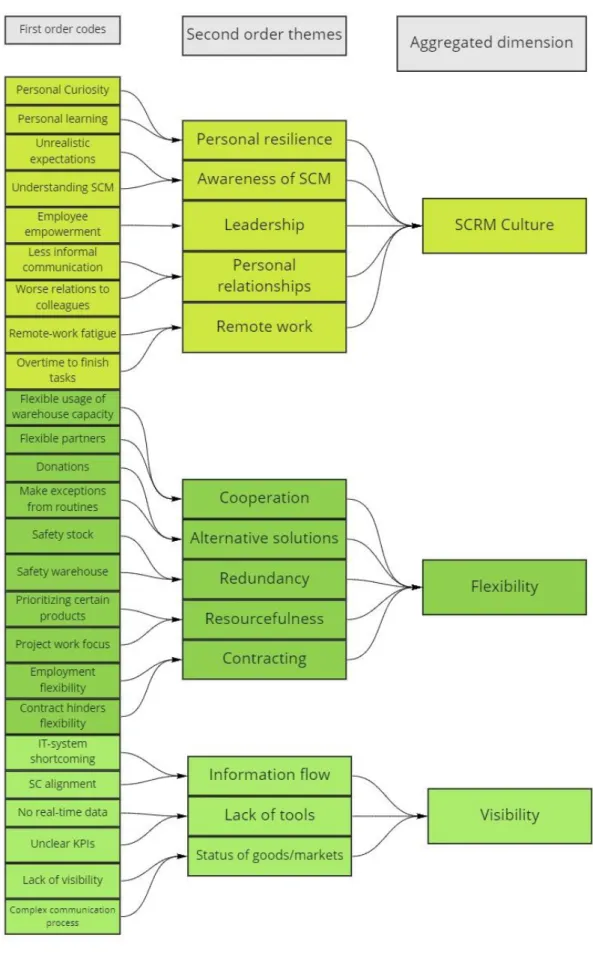

Figure 4: The aggregated dimensions of SCRM Culture, Flexibility and Visibility. ... 30

Figure 5: The aggregated dimensions of Collaboration, Growth and Uncertainty. ... 31

Figure 6: Research procedure ... 34

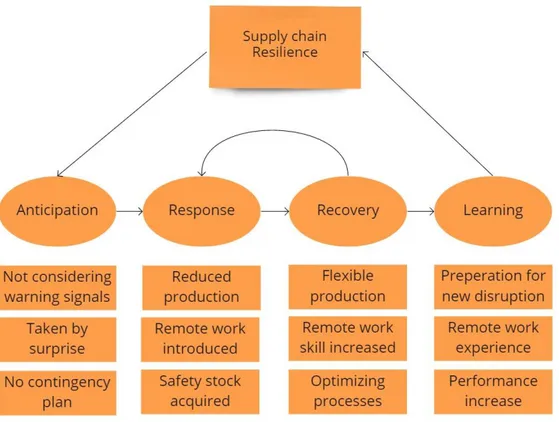

Figure 7: Identified challenges and responses related to COVID-19 ... 54

Figure 8: Resilience phases in the pandemic context ... 57

Figure 9: Supply chain resilience in the context of a pandemic ... 70

List of tables

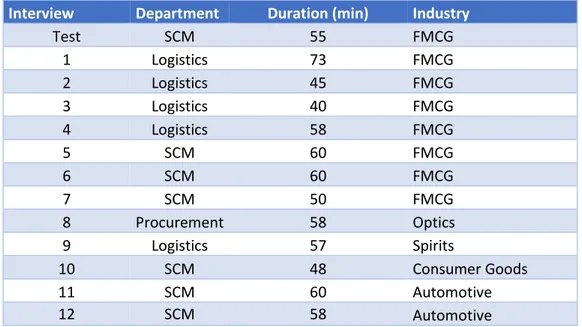

Table 1: Interview participants ... 27List of appendices

Appendix 1 The topic guide ... 91Appendix 2 Consent form and participant information sheet ... 93

Appendix 3 Except of the Codes, themes and aggregated dimension ... 97

Appendix 4 Remote work resilience framework ... 99

vii

List of Abbreviations

Abbreviation

Full Word

SCM

Supply chain management

SCRES

Supply chain resilience

SCRM

Supply chain risk management

KPI

Key performance indicator

IT

Information technology

1

1

Introduction

This chapter introduces the topic of the COVID-19 pandemic's impact on supply chains.

"By failing to prepare, you are preparing to fail."

-Benjamin Franklin

Franklin's quote works perfectly in the supply chain context. Companies need to be aware of the risk of disruption and implement appropriate risk mitigation strategies.

Global supply chains have emerged due to customer demand and competitive pressure. Conversely, supply chains have become more extensive and complex, leading to higher vulnerability to disruption (Manuj & Mentzer, 2008a). Managing supply chain activities is increasingly difficult in a disruptive and dynamic environment (Blackhurst et al., 2005; Chopra & Sodhi, 2004; Craighead et al., 2007).

The nature of disruptions can be roughly put into two categories. Firstly, human-made, anthropogenic catastrophes such as a financial crisis (Jüttner & Maklan, 2011), terrorism (Khan et al., 2018), political turmoil (Tukamuhabwa et al., 2017), port stoppages, losses of critical suppliers, quality issues, equipment failures, poor communication and human errors (Jabbarzadeh et al., 2016). The second source of disruption are environmental disasters like the earthquake in Japan in 2011 (Todo et al., 2015), droughts, hurricanes, flooding, or pandemics like the current COVID-19 pandemic (van Hoek, 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic has created an incomparable global disruption in modern supply chains and should therefore be scrutinized in greater detail (van Hoek, 2020).

As a result of the disruption, companies do not meet their customers' demands at the right time, at the right place, and with the right quantity. Not meeting customer demand leads to lost sales, delays, lost customers, and damage to its reputation (Jüttner & Maklan, 2011; Sheffi & Rice, 2005). Historically, many firms have been forced to close or rebuild due to disruption (Chen et al., 2016). As many as 75 % of firms in 71 countries have experienced a disruption in their lifetime, 21 % have suffered significant financial losses of more than 1 million Euros (Pournader et al., 2016). The popular management press has urged decision-makers to rethink their supply chains to make them more resilient (Linton & Vakil, 2020; van Hoek, 2020).

2

Supply chain resilience (SCRES) can be defined as the "capacity of a firm to recover its

supply chain operations from an unforeseeable event that causes disruption" (Christopher

& Peck, 2004; Sheffi & Rice, 2005; Wong et al., 2020). Furthermore, it can also help mitigate disruption with planning, preparing, and taking pre-emptive action (Tomlin, 2006). That includes having a buffering capacity in production and inventory (Chopra & Sodhi, 2004; Sheffi & Rice, 2005). When a supply chain faces a disruptive event, resilience is its capability to reduce the impact and help it recover to its original state (Melnyk et al., 2014). In other words, resilience is considered a dynamic ability of the supply chain to effectively adapt, respond, and recover from disruption, increasing the firm's competitive advantage (Yu et al., 2019).

However, an issue is that researchers may not have guided the industry in the right direction. A survey with a sample of 700 showed that 60 % of the responding procurement managers experience a lack of transparency in their supply chains (Forde, 2020). Another survey based on 450 companies by Prasad (2020) from March 2020 showed that only 49 % of the responders had made business continuity plans. A similar study in May 2020 by Zwemke and Leonardi (2020) showed that 47 % of the responders had robust planning in place or were already executing post-pandemic plans. Interestingly, Prasad (2020) also found that 64 % of companies anticipated that everything would go back to normal within 3-6 months (Prasad, 2020). These numbers show that companies do not plan to make their supply chains more resilient and create recovery capabilities even if we are currently under extreme supply and demand disruption. Instead, companies keep hoping that things will go back to normal within short notice while the management press calls for action. The numbers suggest a gap between understanding supply chain risks in industry practice and literature (van Hoek, 2020).

Nonetheless, that does not imply that companies are unprepared for any form of risk. According to Chopra and Sodhi (2004), companies tend to develop protection against recurrent low-impact disruptions. Still, the Achilles' heel is the high impact, rarely occurring disruption. At the same time, even a rare impact with low probability should not be ignored since a firm's ability to respond effectively to adverse events is crucial for its longevity and competitive advantage (Child, 1972; Bode et al., 2011).

3

Problem Description

Researchers argue that the concept of SCRES in existing studies should be investigated and challenged in the light of new phenomena (Pettit et al., 2019). The COVID-19 pandemic differs from other disruptions because of its unpredictable effect on supply and demand in supply chains. It can be described as a "black swan event". An unexpected event with significant consequences, even though some argue that scientists predicted such a pandemic (McGillivray, 2020). While most other disruptions occur regionally and timely limited, the COVID-19 outbreak affects the whole world and is already lasting more than a year and therefore, COVID-19 differs from a 'normal' disruption since it not only affects companies but entire societies (Sodhi & Tang, 2021).

While the industry practitioners hoped that things would revert to normal within 3-6 months in March 2020 (Prasad, 2020), it has not yet happened, and new lockdowns have been introduced in different parts of the world. As of January 28,2021, the virus has infected more than 100Mio people and caused more than 2Mio confirmed deaths worldwide (WHO, 2021). Apart from the high threat to health and life, the pandemic also caused disruptions to companies and supply chains in several different ways. Employees could not come to work because they were sick or under quarantine. Companies were forced to temporarily close plants under the governments' order to prevent further spreading of the virus, and international travel nearly came to a standstill. Altogether, 86 % of the UK's global supply chains were disrupted during the Coronavirus outbreak, according to the Chartered Institute of Procurement and Supply (CIPS, 2020). Furthermore, physical stores with non-essential products were forced to close in many countries, and for several weeks, businesses could not sell their products and had to keep their stock (e.g., The Guardian, 2021). These shutdowns resulted in further disruptions on the demand side of supply chains.

Even though COVID-19 is not the first pandemic, the impact of the disease on the global society is incomparable to other virus outbreaks in the past century. While other illnesses like the SARS outbreak and the "swine flu" also affected the whole world, they were not as contagious and severe as COVID-19 (Healthline, 2020; WEbMD, 2010). Therefore, it is vital to research the impact of COVID-19 in different industries and parts of SCM. Some studies already focussed on the strategic view of COVID-19. However, to our knowledge, there has been little research done about challenges in operations in SCM

4

caused by global disruption such as the COVID-19 pandemic, and we are aiming to close this gap.

Purpose

The purpose of this thesis is to examine the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on operations in supply chain management and connect this to the theory of supply chain resilience. We focus specifically on the challenges and personal experiences of people working in supply chain management. By better understanding disruptions from an operational perspective, decision-makers can improve the supply chain's resilience.

Following this, the thesis seeks to address the following research questions:

RQ1: What are the challenges for supply chains to operate during complex disruptions like pandemics?

RQ2: In what ways could supply chain management acknowledge the experiences from the current COVID-19 pandemic to their future operations?

Delimitations

We are limiting our study to the experiences of employees of different departments connected to SCM. Our respondents work for large companies with more than 1000 employees operating with supply chains globally. The departments we focus on are logistics and procurement. We want to interview different people in each company to get different views of the topic. We focus on personal experiences and less on the strategic development of the companies during the pandemic. Finally, we will base our research on interviews as primary data and support our findings with quantitative data from secondary sources.

5

2

Literature review

In the following chapter, we will offer the theoretical background of the topic. Therefore, we briefly describe SCM, followed by risk management in supply chains and previous research about supply chain resilience. We included risk management since the concept is closely related to supply chain resilience (SCRES).

Supply Chain Management and the Issue of Globality

The definition of SCM evolved, and researchers still do not entirely agree on one definition. In general, they agree that a supply chain consists of separate entities connected by the physical flow of goods, information flow, and financial flow between them (Sodhi & Tang, 2012). Supply chains consist of all raw material suppliers until the final customer (Christopher & Peck, 2004; Craighead et al., 2007). Sodhi and Tang (2012, p.6) define SCM as:

“The management of material, information, and financial flows through the supply chain. It includes the coordination and collaboration of processes and activities across different functions such as marketing, sales, production, product design, procurement, logistics, finance, and information technology within the supply chain.”

Since there are no linear supply chains with only a path from the first supplier to the final customer, supply chains can be described as a supply chain network (Christopher & Peck, 2004). Christopher and Peck (2004) argue that the discipline evolved out of the goal to provide higher value to customers and shareholders by putting aside self-interests and focussing on cooperation. Holland (1995) states that the development of inter-organizational information systems partly drove the development of SCM. The entities in a supply chain are interdependent, and one entity's strategic decisions influence the other members of the supply chain (Manuj & Mentzer, 2008a).

Supply chains became increasingly extensive, complex, and primarily global during the past decades (Blackhurst et al., 2005; Kamalahmadi & Parast, 2016b). Globalization led to more competition in the market and offered many opportunities to reduce costs and increase efficiency (van Hoek, 2020). Companies want to take advantage of international product, capital, and factor markets (Manuj & Mentzer, 2008a). Therefore, they outsourced production to, for example, China and India to reduce costs by utilizing the lower salaries in developing countries (Fiksel et al., 2015). To reach more customers and

6

satisfy country-specific demands, companies are also forced to offer their products in more variants, leading to the higher complexity of the supply chains and following from this to higher vulnerability (Thun et al., 2011). Most researchers agree that especially lean practices implemented to reduce costs and minimize waste led to higher vulnerability of supply chains (e.g., Fiksel et al., 2015; Kovacs & Sigala 2021). Another consequence of global supply networks and competition is the development of longer supply chains and shorter clock speeds that came with higher proneness to disruption and less space for errors (Kleindorfer & Saad, 2005). Entities in supply chains became more interconnected and therefore required a closer relationship (Thun et al., 2011). A survey conducted by Jüttner (2005) shows that globalization is perceived as the most significant impact on supply chain vulnerability. Companies operating within global supply chains face many challenges such as unevenly developed infrastructure, cultural differences, tolls, and customs that hinder the smooth transportation of goods along the supply chain (Drake, 2011).

To conclude, global supply chains have a higher risk of disruptions due to their more significant potential delay points and uncertainties (Manuj & Mentzer, 2008a).

Risk Management as a Precondition for Resilient Supply Chains

Risk management can be seen as a precondition to create resilience, and the two concepts are closely interrelated (Christopher & Peck, 2004; Jüttner & Maklan, 2011; Shashi et al., 2020). Jüttner and Maklan (2011) determine a positive effect of supply chain risk management (SCRM) on SCRES, and Pettit et al. (2019) argue that resilience is an enhancement to risk management. Therefore, we investigate the concept of SCRM first. It is difficult to define risk because the concept varies significantly between different disciplines (Manuj & Mentzer, 2008a). In general, risk is a consequence of uncertainty. In other words, the possible occurrence of an event leads to the presence of risk (Manuj & Mentzer, 2008b). Manuj and Mentzer (2008a) state that all definitions of risk include three components. (1) the potential losses when the risk is realized, (2) the probability that the risk is realized, and (3) the significance of the consequences of the potential losses. According to Manuj and Mentzer (2008b), adding two more components to risk on the supply chain level is essential. Speed, which includes the pace of unexpected events that lead to losses on a supply chain level, how often the circumstances lead to

7

financial losses, and finally, the speed of discovery. The second dimension added is the frequency in which disruptive, unexpected events occur.

Risk management is about preventing and mitigating potential risks because they represent a threat to the supply chain (Chopra & Sodhi, 2004; Fahimnia et al., 2015). Assessment of risks is a key factor for the survival of companies, and the risk of disruptions differs between companies and industries (Fiksel et al., 2015). Chen et al. (2016) demonstrated that disaster risk assessment is crucial to consider in long-term business strategies. While risk is considered in many internal parts of an organization and many different disciplines, the research on risk management studies on the supply chain level evolved just recently (Jüttner, 2005; Ho et al., 2015; Shashi et al., 2020). The insufficient research of risk on the supply chain level is caused by the fact that, in general, risk management is understood as a company-specific task (Jüttner, 2005).

Nevertheless, risk management on the supply chain level became increasingly important due to the higher interconnectedness within the supply chain network, complexity, and the trend towards more lean practices (Thun et al., 2011). However, Birkie (2016) and Ruiz-Benítez et al. (2018) argue that some lean practices are also resilient practices such as close collaboration, and consequently, the strategies are not always contrary. Jüttner (2005) states that while most companies have internal risk management initiatives, the risk assessment and reduction strategies are less implemented on a supply chain level. However, entities in the supply chain need internal risk management plans to contribute to successful risk management strategies on a supply chain level (Kleindorfer & Saad, 2005). While plans for recurring, minor disruptions are well established, supply chains are especially lacking strategies to deal with low probability, high impact disruptions (Chopra & Sodhi, 2004). A significant issue is a lack of shared knowledge about companies' internal risk management with other supply chain members (Jüttner, 2005). However, SCRM should be considered cross-company to identify and reduce risks on a supply chain level. Therefore, we use the definition of Ho et al. (2015, p. 5036) and see SCRM as:

“an inter-organizational collaborative endeavour utilizing quantitative and qualitative risk management methodologies to identify, evaluate, mitigate and monitor unexpected macro and micro-level events or conditions, which might adversely impact any part of a supply chain.”

8

Kleindorfer and Saad (2005) propose that disruption risk management in supply chains consists of three main tasks: specify the risk, assess the risk, and develop mitigation strategies.

2.2.1 Challenges of Supply Chain Risk Management

Risk management in supply chains is challenging because it is a trade-off between costs caused by a possible disruption and costs associated with prevention and mitigation initiatives (Chopra & Sodhi, 2004; Kleindorfer & Saad, 2005; Fiksel et al., 2015). Chopra and Sodhi (2004, p.55) compare the task of a risk manager with a stock portfolio manager:" Achieve the highest possible profits for varying levels of risk and do so

efficiently.", which indicates that it is essential to mitigate the risk without reducing the

earnings of the company. The right amount of investment in risk management capabilities depends on the supply chain's vulnerability since a higher vulnerability leads to higher exposure to risk (Fiksel et al., 2015). Higher exposure to risk then requires higher risk management capabilities (Fiksel et al., 2015). Consequently, the challenge is to find the right balance between the exposure to risk and the erosion of profits (Figure 1)(Fiksel et al., 2015). Pettit et al. (2019) state that it is hard to identify the right risk management capabilities since the avoided and reduced impact of disruptions are difficult to monetarize. Jabbarzadeh et al. (2016) found that only slight configurations of the supply chain design and minor investments in risk management capabilities can significantly influence resilience. Moreover, extensive investments do not necessarily reduce the strategic costs but can even increase them (Jabbarzadeh et al., 2016). Hence, they confirm Figure 1.

9

Figure 1: Zone of right risk management capabilities Own figure based on Fiksel et al. (2015)

Another challenge that needs to be considered is that one disruption risk mitigation strategy can increase the risk of another disruption (Chopra & Sodhi, 2004). As an example, Chopra and Sodhi (2004) relate to safety stock, which can reduce the impact of a supply disruption but can be obstructive during a demand disruption. Moreover, SCRM requires visibility and transparency between supply chain partners (Kleindorfer & Saad, 2005). Still, many entities are unwilling to offer this sensitive information since they do not want to point out their weaknesses (Kleindorfer & Saad, 2005). Finally, some entities in a supply chain could be more willing to work on SCRES than others because the incentives to do so are unevenly distributed (Scheibe & Blackhurst, 2018).

2.2.2 Characterization of Supply Chain Disruption Risk

Researchers have developed several different classifications of risk (Chopra & Sodhi, 2004; Christopher & Peck, 2004; Jüttner, 2005; Tang & Tomlin, 2008; Manuj & Mentzer, 2008a; Shashi et al., 2020). Christopher and Peck (2004) identified three types of risk. Internal risk to firms results from the possible failure of internal processes and control,

10

such as a mechanical failure. Secondly, external risk within the supply chain results from the supply side, like a financially unstable supplier or a supplier with quality problems, and the demand side, such as an uncertain forecast. Finally, the environmental risk results from the possible occurrence of natural disasters, political changes, or other disruptions that are not related to the supply chain.

In comparison, Shashi et al. (2020) chose to combine external and internal risk and call it operational risk caused by uncertainty relating to information (E.g., volatile customer demand that causes forecast issues or a malfunctioning production line). Moreover, Shashi et al. (2020) call them disruption risk and split them into environmental or anthropological risk. Environmental being an earthquake or disease and anthropological is man-made such as financial recession or a terrorist attack (Kleindorfer & Saad, 2005). To conclude, most researchers identify disruption risk as a special kind of risk. Disruption risks are less frequent than operational risks but cause significantly more damage economically and socially (Jabbarzadeh et al., 2016). Interestingly, Thun and Hoenig (2011) came to a different conclusion. Even though they agree that disruption risks are less frequent, the overall impact is less severe because of their lower probability than operational risks. Additionally, disruption risks are also complex to mitigate since no statistical data is available for unpredictable events that rarely happen (Fiksel et al., 2015; Sáenz & Revilla, 2014). For this reason, Kleindorfer and Saad (2005) argue that disruption risk cannot be managed the same way as operational risk. Companies tend to develop plans for reoccurring risks with low impact. Meanwhile, high-impact, rarely occurring disruptions are ignored (Chopra & Sodhi, 2004). However, academics shifted the focus towards low-probability, high-impact disruptions during the last years (Ivanov et al., 2014; Jabbarzadeh et al., 2018; Shashi et al., 2020).

According to Bode et al. (2011), the willingness to create a mitigation plan can be determined by (1) the impact of disruption, (2) dependence on the partners involved, and (3) the firm's disruption orientation. This concept encompasses the general awareness and recognition of the opportunity to learn from supply chain disruptions (Bode et al., 2011). Additionally, a quick and responsive reaction to environmental changes is a competitive advantage. For example, a firm that changes its routines, structures, and information processing rapidly in response to disruption performs better over its lifetime than a gradually changing firm (Miller & Friesen, 1982).

11

Conclusively, supply chain disruptions have become more frequent (Mccrea, 2019). Because of their severe implications on the supply chain, they should be treated as a significant managerial concern (Hendricks & Singhal, 2003). In particular, managers' response decisions can have substantial negative consequences on the whole supply chain network if they are only focused on the focal firm (Scheibe & Blackhurst, 2018). Nevertheless, Golgeci and Ponomarov (2013) discovered that disruptions trigger innovation and that the severity of a disruption positively influences innovativeness. Some research on disruptions has been done based on specific events (e.g., Jüttner & Maklan, 2011; Todo et al., 2015). So investigated Todo et al. (2015) the impact of the great earthquake of Japan in 2012 and discovered that extensive supply chain networks could positively affect the recovery time of firms within an affected area. However, the affected supply chain must deal longer with the impact of a disruption. Moreover, Todo et al. (2015) recognized that networks outside of the affected area stimulate short-term recovery, and networks within the affected area stimulate medium-term recovery. Jüttner and Maklan (2011) focused on the global financial crisis of 2008 and stated that it was the first empirical investigation of a global, disruptive event on SCM. Moreover, Jüttner and Maklan (2011) investigated the relationships between SCRM, supply chain vulnerability, and SCRES. They concluded that more vulnerable supply chains require better risk management and that better risk management leads to higher resilience.

2.2.3 The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Supply Chains

Before the COVID-19 outbreak, only very few articles investigated the impact of pandemics on SCM (Chick et al., 2008; Dasaklis et al., 2012; Ekici et al., 2014; Simchi-Levi et al., 2014; Santos et al., 2014; Schaetter et al., 2019). According to Simchi-Simchi-Levi et al. (2014), pandemics belong to the low probability, high impact risks that are difficult to determine. However, researchers argued that businesses and governments should be prepared because worldwide developments such as a higher population density, urbanization, and climate change could increase the probability of a pandemic outbreak (Dasaklis et al., 2012). Moreover, increasing international travel could enhance the spread of a new virus (Ekici et al., 2014). Additionally, Ekici et al. (2014) demonstrated the usefulness of quarantines to reduce the spread of a virus and stabilize supply chains during a pandemic. Since the last virus outbreaks were considered as epidemics (locally

12

restricted) and not pandemics (globally), researchers lacked empirical data to investigate the topic comprehensively (Dasaklis et al., 2012). Therefore, we see the COVID-19 pandemic as an opportunity to support the research with empirical data.

The COVID-19 pandemic is a global disruption and directly affects companies worldwide (van Hoek, 2020). Such a disruption before the COVID-19 pandemic was, for example, the global financial crisis of 2008 (Jüttner & Maklan, 2011). Even though the COVID-19 outbreak started just over a year ago, many researchers focused on this concerning SCM (Ivanov, 2020a, 2020b; van Hoek, 2020; Flynn et al., 2021; Nikolopoulos et al., 2021). Ivanov (2020a) built on the challenges of COVID-19 to introduce the viable supply chain model that connects agility, resilience, and sustainability to cope with the changing environment. Van Hoek (2020) conducted a qualitative study to gain insights into executives' experiences to suggest research opportunities related to COVID-19.

2.2.4 Disruption Propagation in Supply Chains

Jüttner (2005) first described disruption propagation and thereby argued why it is essential to manage risk on the supply chain level. Due to the linkage between the entities in a supply chain, just focusing on company-specific risk management is insufficient (Jüttner, 2005). Jüttner (2005) further described that a later entity could be affected if a sub-supplier's plant is damaged or destroyed during an external disruption and cannot continue operations in a normal state. Even companies outside of a disrupted supply chain can be affected (Scheibe & Blackhurst, 2018). For example, when one company switches to an alternative supplier because the usual supplier has been damaged during a natural disaster, the new supplier might not fulfil all customers' demands (Scheibe & Blackhurst, 2018).

Moreover, the severity of the disruption can even increase while affecting other supply chain entities (Blackhurst et al., 2011). The extent depends on different factors like the dependency of supply chain entities and the human response (Scheibe & Blackhurst, 2018). Scheibe and Blackhurst (2018) elaborate that wrong managerial decision are drivers of disruption propagation, and companies should not only focus on themselves but also the whole associated supply chain network. A disruption propagation with severe impact happened during Japan's earthquake in 2011, when Toyota lost its position as a market leader even though it was not directly affected (Todo et al., 2015). The effects of

13

a disruption "ripple" through the supply chain (Ivanov et al., 2014). Following this, Ivanov et al. (2014) introduced the term "ripple effect in supply chains" and argues for the importance of implementing SCRES. For example, Jüttner and Maklan (2011) investigated the impact of the global financial crisis on supply chains. They concluded that the declining demand caused a demand disruption that rippled through the supply chains. Later the financial crisis caused a supply disruption because many companies went bankrupt, and companies lost their suppliers.

The Resilience of Supply Chains

Many researchers have investigated SCRES (Christopher & Peck, 2004; Sáenz & Revilla, 2014; Melnyk et al., 2014; Ivanov et al., 2014; Fiksel et al., 2015; Jabbarzadeh et al., 2016; Adobor, 2019). The concept is based on the assumption that not all risks are avoidable (Jüttner & Maklan, 2011; Blackhurst et al., 2011; Hohenstein et al., 2015; Tukamuhabwa et al., 2017). The concept of SCRES moved in the focus of researchers primarily during the last decades (Pettit et al., 2019). Prior to that, businesses focused on cost and customer service optimization and following from this on lean practices (Christopher & Peck, 2004). Still, the development of global and complex supply chains demanded a shift of the focus towards resilience (Christopher & Peck, 2004). Sáenz and Revilla (2014) state that while resilience in supply chains received more attention during the last years, it did not evolve as fast as the complexity of supply chains and following from this the vulnerability.

The definition of resilience differs between research disciplines but generally deals with vulnerability, risk management, and disaster recovery (Ponomarov & Holcomb, 2009). Consequently, risk management and resilience concepts are akin and interrelated (Shashi et al., 2020). For SCM, the definition of resilience evolved, but most researchers involve the fast recovery after a disruption to return to a pre-disruption service level in their definitions (Kamalahmadi & Parast, 2016a; Tukamuhabwa et al., 2017). Hohenstein et al. (2015) collected definitions of SCRES and stated that there is still no clear definition. Christopher and Peck (2004, p.2) provided one of the first highly cited SCRES definitions: "The ability of a system to return to its original state or move to a new, more

desirable state after being disturbed." However, it lacked the time factor, later added by,

14

the disruption and operation maintenance after it occurred. We use the definition of Kamalahmadi and Parast (2016a, p.121), who define SCRES as:

"The adaptive capability of a supply chain to reduce the probability of facing sudden disturbances, resist the spread of disturbances by maintaining control over structures and functions, and recover and respond by immediate and effective reactive plans to transcend the disturbance and restore the supply chain to a robust state of operations."

Yet, even this definition does not include the "growth"-phase after a disruption that was identified by Hohenstein et al. (2015) in many definitions. Hohenstein et al. (2015) noticed that researchers adopt definitions from previous studies or combine the definitions of several researchers. We can conclude that the research society still does not agree on one definition.

Moreover, researchers are disputed what exactly is part of SCRES. There are several concepts and strategies that some researchers behold as part of resilience, and others distinguish from resilience. For example, Hohenstein et al. (2015) argued that all strategies and methods that mitigate the negative impact of disruption are part of SCRES. However, Christopher and Peck (2004) and Brandon-Jones et al. (2014) distinguish between robustness and resilience. They argue that resilience is more about restoring a system to the normal state of operations after being disrupted, and robustness is about maintaining operations. While the expressions can be used as synonyms in many disciplines, according to Christopher and Peck (2004), it is essential to differentiate between them in a supply-chain context.

Nevertheless, we see SCRES as an umbrella term that includes all strategies to mitigate the negative impact of a disruption. As Ivanov et al. (2014), Kamalahmadi and Parast (2016a), and Pettit et al. (2019), we consider robustness as part of resilience.

Altogether, researchers agree that resilience is a dynamic capability to respond to changes and that a resilience strategy is essential to mitigate the negative impact of disruptions on the supply chain (Sheffi & Rice, 2005; Scholten et al., 2014; Fiksel et al., 2015; Kamalahmadi & Parast, 2016a).

2.3.1 Phases of Supply Chain Resilience

Researchers identified different phases relevant for SCRES (Hohenstein et al., 2015; Kamalahmadi & Parast, 2016a; Shashi et al., 2020). Kamalahandi and Parast (2016a) and

15

Shashi et al. (2020) describe three phases of SCRES. The first is anticipation as the need to prepare for possible disruptions and environmental changes. Resistance is the second and about maintaining operations when a disruption occurred. Finally, recovery and response minimise the negative impact and return to the normal state of operations after a disruption hits the supply chain. Hohenstein et al. (2015) identified four phases in the literature relevant for SCRES. (1) Readiness, being prepared for disruptions and taking measures to avoid these. (2) Response, how an entity in a supply chain reacts to a disruption. (3) Recovery, which is a crucial phase after a disruption and implies the ability to bounce back to a pre-disruption state in operations and finally (4) growth, which stands for the ability to move to a better state of operations after a disruption and improve the competitive position. According to Hohenstein et al. (2015), response and recovery seem to be the key elements of SCRES.

2.3.2 Elements of Supply Chain Resilience

Due to the extensive research and ambiguity of SCRES, it is challenging to sort the elements of SCRES (Hohenstein et al., 2015; Chowdhury & Quaddus, 2016). Moreover, some elements are used interchangeably by different researchers (Kamalahmadi & Parast, 2016a). Researchers developed various frameworks to describe SCRES (Christopher & Peck, 2004; Blackhurst et al., 2011; Kamalahmadi & Parast, 2016a; Shashi et al., 2020). For example, Chowdhury and Quaddus (2016) identify SCRES as a "third-order hierarchical construct" that includes the two second-order dimensions readiness and response-recovery and the first-order dimensions flexibility, redundancy, visibility, collaboration, disaster preparation, response, and recovery. Hohenstein et al. (2015) describe the six key elements flexibility, redundancy, collaboration, agility, information sharing, and visibility that contribute to SCRES. Ali et al. (2017) identify 13 elements divided into the pre-disruption phase, during-disruption phase, and post-disruption phase. For a general overview of resilient supply chain practices, we refer to Ruiz-Benítez et al. (2018). We identified four key elements of SCRES, and in the following, we distinguish and characterize them.

16

2.3.2.1 Flexibility

The term flexibility is frequently used in the literature. Hohenstein et al. (2015) describe flexibility as an essential factor in all phases of SCRES. It needs to be implemented in the businesses' supply chain strategy. Flexibility is required to respond to disruptions fast and efficiently and in the literature often described as agility after the initial impact of a disruption (Ponomarov & Holcomb, 2009). The speed of the response is frequently described as velocity and a crucial factor of SCRES (Christopher & Peck, 2004; Scholten et al., 2014).

Christopher and Peck (2004) state that flexibility represents strategies that enable the ability to keep several options open. Flexibility applies, among others, to the number of suppliers for different parts. While one supplier can lower costs, a higher number of suppliers can deliver enough supplies when one faces a disruption (Christopher & Peck, 2004). Consequently, flexibility covers the element of redundancy which relates to additional capabilities and inventory (Jüttner & Maklan, 2011). Nevertheless, Sheffi and Rice (2005) describe redundancy as a separate resilience capability, but Jüttner and Maklan (2011) propose redundancy is part of flexibility. Implementing redundancy is a trade-off to efficiency in the operations (Christopher & Peck, 2004). Zsidisin and Wagner (2010) stated that while redundancy cannot reduce the risk of disruption, it can reduce the impact once a disruption occurred.

Tang and Tomlin (2008) proved that flexibility in supply chains is a way to respond to disruptions to mitigate the impact and can even be a competitive advantage. They relate to the cases of Honda, which can introduce new models more frequently than the competition, and the company Zara, which can respond faster to changes in fashion. However, flexibility usually causes higher costs during regular and stable business times (Ivanov et al., 2014).

Flexibility can also apply to prioritising certain product types in the production and, in this way, avoid disruption in the supply chain (Shashi et al., 2020). Shashi et al. (2020) describe this element of resourcefulness as the capability to identify problems, prioritize and establish resources when there is an imminent event that causes disruption. It is the ability to apply material and human resources to prioritized areas to achieve the goals of avoiding disruption (Brandon-Jones et al., 2014; Shashi et al., 2020).

17

2.3.2.2 Collaboration

Researchers agree that collaboration is one of the most important elements of SCRES (Christopher & Peck, 2004; Jüttner & Maklan, 2011; Scholten et al., 2014; Scholten & Schilder, 2015; Kovács & Sigala, 2021). Collaboration between the supply chain entities is fundamental to manage risk in highly interconnected supply chains (Pettit et al., 2019). According to Scholten and Schilder (2015), collaboration covers information sharing, communication between entities within a supply chain, and mutually created knowledge. Sharing information with other supply chain entities can reduce uncertainties and complexities (Gunasekaran et al., 2015). Moreover, the early sharing of detailed and reliable information with supply chain partners can increase the velocity of the response to a disruption (Scholten & Schilder, 2015). Scholten and Schilder (2015) also discovered that joint decision-making increases the flexibility of the supply chain. Since delayed information sharing leads to later adaptions of production schedules of supply chain partners, other supplies cannot be stopped or ordered in time. However, organizations usually do not aim to develop long-term strategic collaboration with all of their partners (Scholten & Schilder, 2015).

Azadegan and Dooley (2021) distinguish collaboration in two different levels. First, the micro-level collaboration between organizations, such as between buyers and suppliers, and the macro-level collaboration between companies and governmental institutions. Global disruptions like a pandemic enhance collaboration between private companies and governments. For example, governments offer financial support to companies and individuals that faced a negative financial impact (Azadegan & Dooley, 2021).

2.3.2.3 Visibility

Brandon-Jones et al. (2014) described visibility as an antecedent to resilience. Visibility in SCM refers to the ability to track the status and location of units throughout the supply chain (Jüttner & Maklan, 2011). It supports the proper decision-making in regular business times and particularly after a disruption (Jüttner & Maklan, 2011). Zsidisin and Wagner (2010) suggest that firms should invest in knowledge about their supply chains to understand potential risks. Hence, visibility can reduce risk and significantly mitigate the extent of the disruption propagation (Chopra & Sodhi, 2004). In addition to that, visibility can reduce the complexity in supply chains by utilizing real-time data without

18

relying on predicted data (Gunasekaran et al., 2015). For global and complex supply chains, visibility to second and third-tier partners can be appropriate (Hosseini & Ivanov, 2019). Since visibility involves the willingness of entities to share sensitive information with supply chain partners, it is connected to collaboration (Scholten & Schilder, 2015). Blackhurst et al. (2005) stated that visibility is a crucial capability to deal with disruptions. Visibility is usually connected to information technology (IT) and can improve decision-making under uncertainty (Brandon-Jones et al., 2014). However, it is also related to high costs in the form of technology and infrastructure, and therefore it is vital to consider carefully which degree visibility is required (Blackhurst et al., 2005).

2.3.2.4 Supply Chain Risk Management Culture

Researchers argue that companies need to adopt a Supply chain risk management culture (SCRM culture) to become more resilient (Christopher & Peck, 2004; Chowdhury & Quaddus, 2016). Some argue that SCRES starts with the individual resilience of the employees (Blackhurst et al., 2011; Lengnick-Hall et al., 2011; Kamalahmadi & Parast, 2016a; Adobor, 2019). Blackhurst et al. (2011) discovered that individuals with an understanding of SCM contribute to better SCRES by quicker reaction and better decisions after a disruption. Individual employee resilience and empowerment includes efforts from leadership and HR to provide training to detect and adequately react to disruptive events (Blackhurst et al., 2011). Lengnick-Hall et al. (2011) describe the importance of human resource management to educate individuals to become more resilient to perform better during a disruption.

Furthermore, the organisation can enhance individual resilience if it allows employees to do active experimentation without repercussions (Adobor, 2019). Adobor (2019) expands on how context can cause people to become more learning-oriented. For instance, if they are confronted with challenging tasks or are encouraged to question their current knowledge set. Adobor (2019) also underlines another resilience factor based on deeper relationships based on social competency in an organizational community. Additionally, this social competence can lead to better cross-functional collaboration and strengthen internal and external partnerships (Adobor, 2019).

Kamalahmadi and Parast (2016a) reported the importance of leadership for the individual's resilience. Leaders can change the culture of an organization. They can

19

continuously review company policy and introduce training and education in the most common resilience practices (Kamalahmadi & Parast, 2016a). By working with these methods proactively, leaders can cultivate individual resilience (Adobor, 2019). Sheffi (2005) argues how employee empowerment can further the organisation's resilience. For instance, how actors, such as Nokia, Toyota, and the US Army, have distinguished themselves by using their corporate culture to bounce back from disruptive events make them more flexible. In other words, empowering the employee is how anyone in the organization is encouraged to act when an issue is detected (Sheffi, 2005). Sheffi (2005) gave the example of a single sailor in the navy who has the authority to stop the entire operation and enables quick response. Therefore, according to Sheffi (2005), an organization with the right culture can use its employees' eyes and ears to detect threats. Following this, an enterprise's resilience depends on the organizational culture (Kamalahmadi & Parast, 2016a). Adobor (2019) developed a multi-level framework to demonstrate the interdependencies between the individual's resilience, organizational resilience, and SCRES.

As another part of SCRM culture, Kamalahmadi and Parast (2016a) describe how innovation culture is a critical aspect of the long-term survivability and growth of the company. It includes how the company adapts to changes in the environment. They argue that culture can create shared understanding and direction for innovation in the company. Additionally, Kamalahmadi and Parast (2016a) describe that culture is associated with learning and joint decision-making. Golgeci and Ponomarov (2013) also conclude that innovation is a key enabler for resilience. They used the example that plants that could use the internet to source key components after the earthquake in Taiwan in 1999 could easier recover from the disruption. Therefore they found that higher firm innovativeness increased the chances of reaching the desired SCRES (Golgeci & Ponomarov, 2013).

The Theoretical Framework of this Study

The bigger extend and higher complexity made supply chains more vulnerable to disruptions (e.g., Blackhurst et al., 2005). While common internal disruptions in supply chains are well investigated, and lots of research has been done about SCRES to mitigate the impact, the research about low-probability and high impact disruptions is insufficient (Chopra & Sodhi, 2004). These disruptions are especially relevant to investigate since

20

slow and wrong decisions can negatively impact the disruption on the focal firm and other entities within the supply chain (Scheibe & Blackhurst, 2018). The COVID-19 pandemic belongs to these external supply chain disruptions and causes an incomparable impact (Ivanov, 2020a). It caused long-lasting uncertainty and numerous disruptions in supply chains.

Figure 2 shows the theoretical framework of this study. As shown in the figure, this framework summarizes the main theoretical issues and links between the four phases of SCRES and four key elements that need to be considered to create more resilient supply chains. The emphasis is on the SCRES and the operations impacted by pandemic-related disruptions.

Figure 2: Supply chain resilience framework (adapted from multiple authors)

21

3

Methodology

In the following chapter, we will first explain, discuss and justify our methodological approach. Afterwards, we will present our applied methods for the data collection and justify how we ensure the quality and ethical considerations for this study

Research Philosophy

The ontology in social sciences is based on the behaviour of people. There are three different positions in social science ontology: internal realism, relativism, and nominalism (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018, p. 118). We focus on the relativist viewpoint, assuming that a phenomenon is experienced differently by different people. The people we interview all have different backgrounds, social class, culture, and countries in which they live, which will affect their experiences. The relativist viewpoint indicates that a phenomenon is dependent on the perspective from which we observe them. According to Collins (1989), the perceived truth can vary from place to place from time to time. Multiple truths correspond with our epistemological view that observations become more accurate if multiple perspectives are combined. (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018, p. 116). The ontology also affects which questions should be asked. For a relativist, it is interesting to know how things happen. How strategies are formed and how people adapt to a new situation. (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018, p. 118).

Epistemology is the nature of knowledge, and it can either be positivistic or social constructivist. A positivistic approach uses causality with the help of measurable concept to create generalization through statistical probability. In contrast, we focus on social constructivism and its essence to gain multiple aspects of societal realities determined by people rather than external factors. Social constructivism is tied to people's experiences because human action is based on making sense of different situations rather than external factors. Therefore, we should not only focus on measuring patterns and their frequency but also on the social constructs and meanings that people create from their experiences. For instance, people think and feel in groups or individually and communicate through verbal or non-verbal ways (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018, p. 123). In that sense, we aim to create a deeper understanding of their experiences to gain a holistic view of that complex phenomenon (Kahwati & Kane, 2020). We aim to create a general understanding of the

22

situation from a small number of subjects from which we gather rich data we can use to generalize through theoretical abstraction (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018, p. 124).

The strength of the social constructivism paradigm is that it enabled the understanding of change, the meaning-making of people, to adjust to new issues as they appear, and to be able to contribute with new theories or extend existing ones. It can also provide a holistic and deep understanding of a complex phenomenon derived from only a few cases (Kahwati & Kane, 2020). The data gathering is also more natural compared to the artificial positivistic counterpart.

The weakness of social constructivism is that data collection requires a lot of time and resources. To interpret data can also be a considerable challenge since interpretation is subjectively based on the researcher and their tacit knowledge of the field.

Research Approach

We have chosen to conduct our study with the help of the case study approach to get a deeper holistic picture. In combination with the case study, we have decided to use abductive research logic, also called systematic combining (Dubois & Gadde, 2002). The main idea of systematic combining is to have continuous movement between the theory with its models and the empirical data. In the research process, the encountered research issues and the analytical framework can progressively be altered as empirical data of the natural world unfolds. The first process of systematic combining is the matching of theory with reality. The second process is to create direction and re-direction. These processes are then affected by four factors: what is happening in 'reality, existing theories, a gradually changing case, and an analytical framework.

Abductive logic is more closely related to the inductive approach than the deductive. While deduction would make a proposition from current theory and test it, the inductive approach is based on grounded theory (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). It generates new theory systematically as data is collected (Corbin & Strauss, 1990). Compared to the inductive approach, systematic combining and abduction focus more on the interplay of empirical observations and theory (Dubois & Gadde, 2002). Therefore, abduction is a combination of induction and deduction and is helpful to discover new things, such as variables and relationships. The main concern is to generate new concepts; however, Dubois and Gadde (2002) underline that the main point is theory development rather than theory generation.

23

To conclude, the systematic combining builds on the alteration of existing theories. Therefore, the main difference between inductive and deductive approaches is the importance of the framework. The framework is continuously modified as the unanticipated findings are revealed (Timmermans & Tavory, 2012, p.169).

Research Design

We are using the case method research design since we focus on a small number of individuals with tasks in SCM during a pandemic. The nature of the research, stemming from our research philosophy of constructivism, is to gain a deeper understanding of a phenomenon with a small sample rich in data (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018, p. 195). Just as Yin (2018, p. 13) defined the scope of a case study, we aim to study a "contemporary

phenomenon within its real-world context" to be able to explain "casual links in real-life interventions that are too complex for survey or experimental strategies" Yin (2018, p.

15). Our single-case study is explorative in that we are observing a small group of SCM professionals within a new context and phenomena that have previously not been accessible for scientific investigation (Yin, 2018, p. 25, 42). For an overview of our research approach, we refer to figure 3.

24

Figure 3: Research approach

Data Collection

We have considered our research philosophy, approach and design and decided on using semi-structured qualitative interviews to get an in-depth understanding of our topic. As

25

Tracy (2013) said, interviews are a way to create "mutual discovery, understanding, reflection and explanation" to discover the lived experiences and views of the subject. Therefore, the interviews provide a context to learn about a phenomenon that otherwise cannot be observed. The point is to get the respondents perspective and determine why they have that perspective (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018, p. 278).

We conducted semi-structured interviews that covered beforehand selected topics. The topic guide enables us not to follow a list of fixed questions but develop follow-up questions during the interview to follow our explorative approach and gain additional in-depth information on the covered topics. For this reason, the questions were also open-ended and could not be answered with simply yes or no (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). The order of the topics and questions was not fixed but depended on the interviewee's responses to enable him to focus on his thoughts without disruptions caused by sudden changes in the topics. Moreover, the semi-structured topic guides allow more flexibility regarding the focus of the interviews. In appendix 1, we provide the topic guide with the discussed topics and example questions. However, we did not always precisely ask these questions.

Before the interviews, we provided the interviewees' basic information about the background of the study, such as that it is part of our Master thesis at the Jönköping International School. However, we tried to avoid giving too much theoretical information. Moreover, we informed the potential interviewees about the processing of the interview data and guaranteed anonymity. Furthermore, we send them our consent form (Appendix 2) to ensure permission to proceed with the interview data. However, some interviewees demanded additional information about the covered topics before they were willing to conduct the interviews, which we provided to them.

After considering the advantages and disadvantages, we decided to conduct the interviews in different languages depending on the interviewee's preference. Since not both researchers can conduct interviews in English, German and Swedish, the interviews in German and Swedish were conducted by one researcher. Consequently, researcher 1 conducted the interviews in Swedish, researcher 2 conducted the interviews in German, and both researchers conducted the interviews in English together. Even though the individually conducted interviews could lead to a higher risk of misunderstanding or missing a follow-up question, some interviewees felt more comfortable talking in their mother tongue. This way, we also avoided language barriers. It was easier for the

26

interviewees to express their feelings, personal perceptions, and stories. We believe that the additional information is more valuable than the potential questions of a second interviewer.

We planned to conduct the interviews face to face to gather additional data about the environment and the behaviour of the interviewees. Unfortunately, due to the still lasting pandemic, it would have been challenging. Instead, we decided to conduct the interviews online via Microsoft Teams, Zoom and Skype, depending on the interviewee's preference, to reduce the risk of spreading the virus and risking anybody's health. However, the online interviews allowed us to be more flexible. It facilitated the possibility of conducting interviews with people in different areas and countries and being more flexible regarding the schedule.

Apart from our primary interview data, we followed the "Institute of Supply Management" on LinkedIn to support our collected information with external data. By analysing the surveys, we wanted to compare our respondents' experiences with a more extensive sample. However, we acknowledge that the surveys conducted by the institute are only focused on the supply side but suppose that they apply to other areas in SCM as well. Furthermore, we could attend a company webinar about the current developments in the supply chain and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Sampling Strategy

The sampling strategy is the first step in preparing data collection (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). Our sampling strategy is theory-guided sampling as we are basing our sample on the theory about SCRES. Since we are studying the resilience of supply chains, the sample is employees in SCM in companies with global supply chains. The guiding principle for sampling is to generate theory, and therefore the sampling can be changed as the study progresses. For instance, if the initial data collected are used to generate themes, the sampling can be altered to select the interviewees to develop theory (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018, p. 183). In addition to that, we combined theory-guided sampling with maximum variation sampling to get different insights and experiences from the COVID-19 pandemic. By applying maximum-variation sampling, we can learn about experiences from people in a wide range of positions and develop industry overarching theories.

27

We contacted people from our personal network with jobs such as "Buyer", "Purchaser" "Logistics specialist", "Distribution Developer", "Account Manager", "Transportation Coordinator", "Operations Planner" who worked in companies with more than 1000 employees and global supply chains and managed to get eight interviews. Moreover, we contacted seven companies via their official contact form but could not acquire additional interviewees for our study. Finally, we contacted five people directly on LinkedIn and managed to get one additional interviewee. Due to the difficulties in obtaining additional participants for the study because of the high workload during the crisis and the general caution of large companies regarding sensible data, we also applied snowball sampling. After each interview, we asked the respondents if they could refer us to colleagues that match our sample description, and we acquired three more interviews. After we had an initial trial interview and feedback from a manager from our personal network, we could revise the question guide to fit our purpose. We will not include the trial interview in our analysis below.

Interview Department Duration (min) Industry

Test SCM 55 FMCG 1 Logistics 73 FMCG 2 Logistics 45 FMCG 3 Logistics 40 FMCG 4 Logistics 58 FMCG 5 SCM 60 FMCG 6 SCM 60 FMCG 7 SCM 50 FMCG 8 Procurement 58 Optics 9 Logistics 57 Spirits 10 SCM 48 Consumer Goods 11 SCM 60 Automotive 12 SCM 58 Automotive

Table 1: Interview participants

Data Coding and Analysis

After conducting the interviews, we transcribed the recording using the software sonix.ai for German interviews, and otter.ai and the Microsoft Word transcribe function for Swedish and English interviews. Afterwards, we double-checked the recordings to ensure the correct transcription of the software. We translated the German and Swedish

28

interviews into English to offer the partner all details of the interview. At this point, we agreed that no critical topic or question was missed out during the individually conducted interviews. Moreover, by transcribing and preparing the raw material for the following analysis, we got an overview of the collected data, which helps identify topics of particular interest.

The abductive approach allows the link between existing theory and empirical findings. To generate theory from the empirical findings, we followed the Gioia method grounded theory approach to ground our findings in previous theory while also finding new codes to develop the theory of SCRES. Following the Gioia method, we tried understanding the interviewees' lived experiences, using their own terms, not to take away the respondents' meaning (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018; Gioia et al., 2013). The method is based on diplomacy and discretion. Giving transparency to the informants about manuscripts and models but not granting them any veto power about anything but sensitive data. The key term here is not confidentiality but to keep the informants anonymous (Gioia et al., 2013, p. 19). We kept the informant-centric words respecting their integrity during the initial data coding of the 1st-order codes while also not trying to filter codes and determine categories too early. Here there is a tendency to get lost in the numerous categories, around 50-100 from the first ten interviews, which we did. However, the Gioia method also encourages getting almost lost in the beginning because "You gotta get lost before

you can get found" (Gioia et al., 2013, p. 19). Then we organized the 1st-order codes into 2nd order theory-centric themes.

Here we start to seek differences between the categories to reduce them to a manageable number of around 25-30. Here we worked together closely to avoid biased interpretations. We gave those categories labels or a phrasal description, preferably based on the informant's own words. When we observed the vast display of data, we started to probe it on a more abstract level to get the more profound meaning and structures behind the data. We began to analyse multiple levels simultaneously: the 1st-order codes, the more abstract 2nd-order themes and the dimensions of a larger narrative. All of which would lead to answer the research question of "what is going on in this case". In the 2nd-order analysis, we then focused on theory alone. We asked ourselves how the emerging themes could describe and explain the observed phenomenon. Here we could focus on new arising concepts which do not have a strong foundation in the existing literature. Once we had made a manageable set of themes and concepts, reaching what Glaser and Strauss