Shared Mobility as a

Socio-Technical

System

MASTER THESIS WITHIN: Informatics NUMBER OF CREDITS: 30

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: Information Architecture and Innovation AUTHOR: Wiebke Lena Henke

HAMBURG May 2020

Master Thesis - Informatics

Title: Shared Mobility as a Socio-Technical System

Authors: Wiebke Lena Henke

Tutor: Andrea Resmini

Date: 2020-05-19

Key terms: shared mobility system, socio-technical system, experience ecosystem, Augsburg, Mobil-Flat

Abstract

A major shift in our society is the one from a goods-dominant logic to a service-dominant one. Ownership becomes less important, while services from the area of sharing economy experience a rising demand. Municipalities and private companies are adapting and different shared mobility systems are emerging from their pursuit of new forms of mobility.

In 2019, Augsburg created a shared mobility system where public transport, carsharing and bikesharing are all provided via one subscription. As this form of subscription does not have many customers yet, this thesis aims to first identify the system and research which reason and components motivate the people in Augsburg to use the system, as well as collecting different ideas for improvement. An expert interview was conducted with someone from the operator side and then customer interviews were held to get an insight from the customers’ point of view. This data was analyzed using tools from the area of information system as well as information architecture and the system was mapped out and discussed.

The system was mapped out around the user and the connections were shown, which indicated that the user wants simplicity and clarity, as too many platforms and ways to book a mobility service was stated negatively.

Acknowledgements

After studying “Information Architecture and Innovation” for two years, handing in this thesis via an online upload and not being able to celebrate with the whole IA class of 2020 feels very wrong. But difficult times require exceptional measures, and I am sure the whole class will celebrate via Zoom after (or during) the opposition.

Firstly, I would like to thank Andrea Resmini for his guidance throughout the last two years. Whenever I had a question, he gladly gave me an answer which lead to me having way more questions than before. By now I know that asking the right question is what it is about. Giving an answer is not as important, as it all depends.

Secondly, I want to thank my classmates, Wilian and Rients. Us all being in different parts of Europe makes things hard. Seeing you guys every morning in our daily Skype call to talk about our progress, discussing ideas about the thesis and philosophizing about our futures made things almost normal again.

Lastly, I would like to thank Julia, for reading this thesis again and again, as well as my family for bearing with me during this stressful time.

Table of Contents

1.

Introduction ... 1

1.1 Research Problem... 2 1.2 Purpose ... 2 1.3 Research Question ... 3 1.4 Delimitations ... 3 1.5 Definitions ... 42.

Theoretical Background ... 5

2.1 Approach to Literature Review ... 5

2.2 Sharing Economy ... 6 2.3 Services ... 8 2.4 Shared Mobility ... 10 2.4.1 Sidewalk Labs ... 12 2.5 Information Systems ... 12 2.5.1 Socio-Technical System ... 13 2.5.2 Experience Ecosystem ... 13

2.6 Shared Mobility In Augsburg... 14

2.6.1 Stadtwerke Augsburg Organization ... 15

2.6.2 Mobil-Flat ... 16 2.6.3 Bikesharing ... 17 2.6.4 Carsharing ... 18 2.6.4.1 Station-Based Carsharing ... 19 2.6.4.2 Free-Floating Carsharing... 19 2.6.5 Public Transport ... 19

2.6.6 City Zone Augsburg ... 20

2.7 Solutions In Other Cities ... 21

3.

Methodology ... 23

3.1 Research Philosophy ... 23

3.2 Research Approach ... 24

3.3 Research Design ... 25

3.4 Data Collection Method ... 25

3.4.1 Semi-Structured Interviews ... 26

3.4.2 Textual Analysis... 28

3.5 Limitations Of Methodology ... 28

3.6 Ethical Considerations ... 29

3.7 Interpreting The Data ... 30

3.7.1 Customer Journey ... 31

3.7.2 Mapping The System ... 31

3.7.2.1 Individual Actor ... 32

3.7.2.2 General Ecosystem ... 33

4.

Results ... 34

4.1 Interviews ... 34

4.1.1 Interview Employee Stadtwerke Augsburg ... 34

4.1.2 Interviews Customers ... 37

4.2.2 Customer Journey 2 ... 48

4.2.2.1 Reflections On The Customer Journey 2: ... 50

4.2.3 Customer Journey 3 ... 51

4.2.3.1 Reflections On The Customer Journey 3: ... 53

5.

Analysis ... 54

5.1 Socio-Technical Mobility System In Augsburg ... 54

5.1.1 Creating Value ... 57 5.2 Experience Ecosystem ... 58

6.

Conclusion ... 64

7.

Discussion ... 67

7.1 Theory Discussion ... 67 7.2 Methods Discussion ... 67 7.3 Results Discussion ... 687.4 Implications For Research... 68

7.5 Future Research ... 69

8.

Reference List ... 70

Appendix ... vi

Interview Guide ... vi

Interview Transcripts ...viii

Interview 1 ...viii

Interview 2 ... xiv

Interview 3 ... xix

Interview 4 ... xxvi

Figures

Figure 1: Location of Augsburg ... 15

Figure 2: Structure of Stadtwerke Augsburg ... 16

Figure 3: Mobil-Flat ... 17

Figure 4: switchh in Hamburg ... 21

Figure 5: Whim in Helsinki ... 22

Figure 6: Mapping ecosystems, based on ... 32

Figure 7: Synthetic Map ... 33

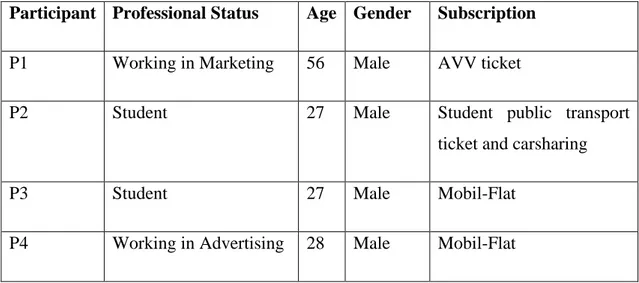

Figure 8: Code categories and clusters from Interviews ... 38

Figure 9: Legend for Customer Journey ... 43

Figure 10: Customer Journey 1, part 1 ... 44

Figure 11: Customer Journey 1, part 2 ... 46

Figure 12: Customer Journey 1, part 3 ... 47

Figure 13: Customer Journey 2 ... 48

Figure 14: Customer Journey 3 ... 51

Figure 15: Components of socio-technical system and their connections ... 56

Figure 16: Path IKEA 1 ... 60

Figure 17: Path IKEA 2 ... 61

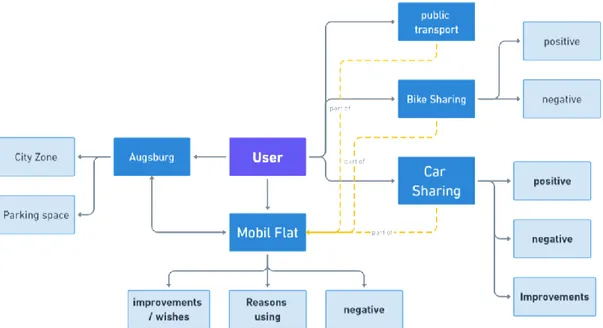

Figure 18: Map of Mobil-Flat system ... 62

Figure 19: Map of improvements ... 63

Tables

Table 1: Service Definition ... 91. Introduction

The sharing economy, the sharing of underutilized resources against compensation (Botsman & Rogers, 2010), and the associated change in consumer behaviour is a result of the increase in networking and digitalization (Botsman & Rogers, 2010). 82% of people under the age of 30 have already used at least one service of the sharing economy (PricewaterhouseCoopers AG, 2015). In addition to the Internet or the smartphone, this digitalization also engenders a rethinking of ownership structures. The sharing economy offers an alternative to ownership and shows what happens when traditional consumption loses relevance and is replaced by a service of sharing.

This change from ownership to a sharing service also affects mobility. Fewer people want to own a car, and more and more people are using shared mobility models. There is a decrease of 13% in car ownership between millennial families and families from older generations (Klein & Smart, 2017). Moreover, the number of car owners can decrease even more when the prices for shared subscription model are lowered (Hörcher & Graham, 2020).

Companies and municipalities are becoming aware of this societal shift and are adapting their product and service portfolio with sharing services. Terms such as “Mobility on demand” and “Mobility as a Service” are gaining more attention, and new mobility systems, having different modes of mobility together, which can be defined by those terms, are evolving.

The overall aim of this thesis is to research and study the shared mobility system in Augsburg, with reference to which factors and groups influence this concept, and are being influenced by this concept. Positive and negative sides of this system are being discussed and recommendations to improve the system will be provided. The understanding of this system from the view of its users is the focal point of attention of this thesis.

After bringing awareness to the topic of shared mobility systems in the introduction, chapter 2 will give the reader a holistic overview of the backgrounds of the sharing economy, shared mobility, the aspects of services and systems itself, as well as information about the German city Augsburg and the mobility system used there. A

description of the used methodology in chapter 3 hands the thread over to chapter 4, where the collected results will be presented. Those results will be interpreted in the following analysis, and the research questions will be answered in the conclusion. A short discussion and a critical view on the thesis will be presented in the last chapter.

1.1 Research Problem

To date, limited research has been conducted about the mobility system in Augsburg, Germany. There exist few case studies regarding bikesharing, however no research has been done on the shared mobility system as a whole.

Many existing studies on shared mobility focus on the market of the USA or the Asian market, where the concepts for different modes of sharing are more common. Therefore, there exists a gap in knowledge about shared mobility for the German market.

In many case studies that were conducted to investigate certain forms of shared mobility or even the sharing economy, only the means were examined. Thus, while the researchers looked closely at the application needed to use bikesharing, for example, they neglected the impact of bikesharing on the users and on the residents living or working in the area of said bikesharing (Forte & Darin, 2017). While the application needed to use the shared mobility system is important, this thesis aims to provide a more holistic view of the system with all its components, such as the applications for the booking system, the spatial factors as well as the advantages and disadvantages of the system.

1.2 Purpose

This thesis has the purpose to conduct research in the area of shared mobility. Thereby it will focus on the following points:

• map out the scrutinized shared mobility system to show how it works • identify the different factors which are influencing the system

As an outcome, recommendations will be given on how to further improve the system. For these recommendations, especially the user’s point of view is taken into account.

1.3 Research Question

The research questions which will be answered with the research and the analysis of this thesis are the following:

Research Question 1: What is the Augsburg mobility system, how does it work and what

are the premises?

Research Question 2: What motivates the people in Augsburg to use the offered shared

mobility system?

Research Question 3: Which changes could be made to the offered mobility system in

order to motivate more people to use it?

1.4 Delimitations

This thesis has been developed within the area of information systems and user experience. Different factors that influence the user experience of the system, as well as the system itself, will be discussed in the following chapters. Recommendations will be provided. It is important to note that this thesis will not look at the economic aspects of the system but will examine the technological and operational parts.

While the theoretical background provides a holistic overview of the sharing economy and shared mobility, as well as general aspects of information systems, the researched socio-technical system is in Augsburg, and therefore only this system within the given area is discussed. This thesis will not develop a general conclusion for different mobility systems, but only for Augsburg.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic which broke out during the conduction of this thesis, fewer interviews than intended could be conducted, and therefore a stronger focus is put on the theoretical framework and its connection with the system in Augsburg. The

pandemic is also responsible for the fact that only literature and sources that were available online were used. Physical libraries were inaccessible due to the pandemic situation.

1.5 Definitions

Throughout this thesis, several technical terms will be used. Since a common understanding of these terms is crucial to the research, they will be defined in this section. These definitions are either official definitions or clarifications of how certain terms are used within this thesis. More complex terms will be explained and defined in the theoretical background (see chapter 2).

Bikesharing: a short-term rental of bikes, usually only able with a membership. Real-time

locations and availabilities of bikes are shared via an application or website, which enables an online booking process. (U.S. Department of transportation, 2020)

Carsharing: similar to bikesharing; a short-term rental of cars for members, also bookable

via an online tool (U.S. Department of transportation, 2020). Different forms of carsharing will be explained later.

Flat rate: a service which has a price fixed at a particular level, no matter how much the

service is used (Cambridge University Press, 2020).

Means and modes of transportation is used in this thesis for the offered mobility options

2. Theoretical Background

This chapter will provide the reader with the theoretical background of the research. First the approach to the literature research is described. From section 2.2 onwards of this theoretical background the terms “sharing economy”, “service”, “shared mobility” and other for this thesis relevant terms will be defined. This thesis researches the effects a shared mobility system has on the residents and users in Augsburg. Especially the aspect of how the sharing economy and shared mobility are affecting the people will be discussed in the following chapters.

In order to later sort the researched model into the background of a socio-technical system, relevant techniques and approaches from the field of Information Systems will be described in section 2.5. As there is only little relevant literature available, a focus is put on case studies which show how socio-technical systems affect the users and people within the system.

The last part of this background is a description of the current situation in Augsburg. It is important to mention that this thesis will only look at Augsburg and therefore, the literature review only focuses on theories concerned for urban areas, .

2.1 Approach to Literature Review

To ensure a holistic literature review, a literature research was conducted. The search was carried out on the three platforms Primo, Scopus and Google Scholar by using selected keywords including “shared economy”, “sharing economy”, “shared mobility” and “mobility on demand”. For every keyword, the first 10 results were examined for how they fitted the general topic of this thesis. Since the terms “sharing economy” and “shared mobility” were coined recently (see 2.2), only articles from 2013 onwards were considered in this research. For further research, articles mentioned in the found articles were looked at and, if the topic was fitting, included in this thesis.

News articles and company driven research is also included in this thesis, as the topics of sharing economy and shared mobility are focused on strongly within the private sector.

From companies in the mentioned sector, the economic feasibility was often mentioned, which will not be considered in this research.

The articles covering socio-technical systems and how they affect the users are selected based on common literature in the field as well as the lectures during the Master programme “Information Architecture and Innovation” at the Jönköping University. The case studies researching the effects of those systems are also selected from the platforms Primo, Scopus and Google Scholar.

The information about the current situation in Augsburg are obtained by researching the information provided on the website of Stadtwerke Augsburg (swa), their social media channels, as well as new articles and observations made by the author.

2.2 Sharing Economy

Current literature has no uniform definition of sharing economy (Botsman, 2013). Therefore, the different views of various authors who coined the term sharing economy are presented below.

The American sociologist and economist Rifkin, a pioneer of the sharing economy (Staun, 2014), predicted a change in society in which access to resources is more significant than possession. According to Rifkin, networks are replacing traditional markets. Rentals or the limited use of property in exchange for various forms of compensation take the place of permanently transferring goods (Rifkin, 2007).

The term sharing economy was introduced by Botsman in her book "What's mine is yours", written with Rogers in 2010. They define the sharing economy as sharing underutilized resources, such as objects, spaces and skills, against monetary or non-monetary compensation (Botsman & Rogers, 2010). Botsman also offers a solution to the conceptual confusion that accompanies the sharing economy (Botsman, 2013). She differentiates between the different terms "collaborative economy", "collaborative consumption" and "peer economy" which are often used as synonyms for the sharing economy.

According to Botsman and Rogers, the collaborative economy is based on networks of connected individuals and communities instead of centralized institutions and is increasingly changing the way we produce, consume, finance and learn. It divides the economic forms into four sections: collaborative production, collaborative consumption, collaborative finance and collaborative education. The sharing economy is sorted by them to the sub-area of collaborative consumption. This describes an economic model in which access to ownership of products and services is made possible by sharing, exchanging, trading or renting them. Botsman differentiates between three different forms of collaborative consumption and thus also the sharing economy: a collaborative lifestyle, redistribution markets and product service systems. In a collaborative lifestyle, resources such as time, space or money are shared. Redistribution markets are platforms on which goods that are no longer or insufficiently used are redistributed. Product service systems, in turn, are used for dispossessed purposes, i.e. renting or lending resources. (Botsman, 2013)

Botsman and Rogers (2010) describe the peer economy as an economic form that enables both direct exchange of products and services between private individuals, as well as collaboration between them to develop, design or distribute products.

In an article published by Botsman two years later, she added the on-demand economy in order to be able to differentiate the terms further. That new category describes platforms that compare customer needs in real time with available offers to enable an immediate delivery of goods and services (Botsman, 2015).

Juliet Schor and Connor Fitzmaurice (2014) also defined the term sharing economy. In contrast to Botsman, Schor and Fitzmaurice consider a uniform definition of this term to be impossible and instead divide the activities within sharing economy into four different categories: recirculation of goods, building social connections, exchange of services and optimizing the use of assets. They define the activities in their contribution as follows: Recirculation of goods addresses the redistribution markets, in which an exchange of used goods takes place between private individuals, e.g. Ebay or gebraucht.de (translation from German: used). Platforms for building social connections allow underused resources to be made available to others. Examples include Airbnb or Couchsurfing with the mediation of unused living space. The third category, exchange of services, describes

platforms such as mediate services from private individuals to other private individuals (P2P) or to companies (P2B). Taskrabbit is one example. Optimizing the use of assets is described as a common use of means of production, shared assets or areas, that are used to enable production instead of consumption. This includes, for example, cooperatives, co-working spaces or platforms such as skillshare.com (Schor & Fitzmaurice, 2014). In a later work by Frenken and Schor (2017), the sharing economy is defined as different customers and consumers, who are granting each other temporary access to their underutilized goods.

While Botsman and initially also Schor, with their rather broad definitions, integrate many facets of the shared use of resources, there are other sources which consider a narrower definition to be correct. Russell Belk (2014) differentiates between "true sharing" and "pseudo-sharing". True sharing includes temporary access to resources without transfer of ownership and, contrary to the definition of Botsman and Schor, without monetary or other compensation. Hence, according to Belk, many platforms are wrongly sorted to the field of the sharing economy.

One critical aspect that can be identified in the different definitions is whether property is transferred or whether only access to the various resources is granted. If access is made possible, it is also controversial whether an entirely new capacity will be created by offering said capacity or whether already existing one will be used more intensively. After the introduction of the different definitions of sharing economy, it needs to be stated that the broader definition from Botsman will be used throughout this thesis.

2.3 Services

The access to property, which is being granted, instead of transferring goods ultimately, is called a service. Another one's resources (the one who is offering something) are being used for the benefit of another actor (who is using the offered items for a certain time without owning them). (Lusch & Vargo, 2019)

which a service needs to comply with: Intangibility, heterogeneity, inseparability and perishability. Those categories applied to a service are as followed:

Table 1: Service Definition (Moeller, 2010)

Intangibility Service is not material or tangible.

Heterogeneity Service experience is unique and not standardized.

Inseparability Service production and the consumption often happen simultaneously.

Perishability Service cannot be stored.

Intangibility says that a service is not material or tangible, while a good is an object which can be physically touched. The provider is offering a promise to the consumer instead of a good. The act of getting from A to B is not tangible, and therefore is a service. The fact that each service experience is unique and cannot be standardized is stated as heterogeneity. There are factors influencing the outcome, such as different providers or different users, external circumstances etc. As the experience of a ride differs due to traffic, weather conditions, the ride itself is a service as well. The production and the consumption of a service often happen simultaneously and are therefore inseparable. The service is first sold and afterwards consumed and produced. There is no set separation of the consumer and the producer and the producer needs the customers resources for the service to work. By renting a sharing car the service is produced, as the car will be made available for the rent. Lastly, the service cannot be stored but needs to be consumed when it is bought. When the carsharing car is rented, the service starts, and it cannot be stored away, as the service already includes the app and the booking confirmation etc. (Moeller, 2010)

Applying the definition of a service to the definition of the sharing economy, one can see that the change that occurs nowadays enabled by the sharing economy, is from a good's dominant logic to a service-dominant logic. By providing access to certain assets and not transferring assets, the concept of a service-dominant logic is more prevalent in today’s society.

2.4 Shared Mobility

The sharing of different modes of transportation within the sharing economy is called shared mobility.

Shared mobility refers to different, often innovative transportation methods, that offer an alternative to car ownership. Due to their innovative nature, those mobility methods often encounter barriers created by governments, mostly unintended. (Berube, 2017)

Due to the rising importance of shared mobility services, the public sector is working on accessing the market as well (Iacobucci, Hovenkotter, & Anbinder, 2017). The sharing economy, driven by many different non-public actors, is advancing at a rapid pace, which makes it difficult for the public sector to plan innovative mobility solutions within the sharing economy. While companies and private persons can work faster and often work with bigger funding, the public sector is slower to move in its innovations, creations and changes (Karim, 2017). Partnerships between private and public parties would lead to a strong and reliable transportation system which would be easier to implement than a purely private one (Shaheen & Stocker, 2018).

Car-, bike- and scooter sharing, either B2C (business to customer) or P2P (peer to peer), as well as ridesharing (e.g. carpooling or vanpooling) and micro transit are different forms of shared mobility (Shaheen & Stocker, 2018). The term microtransit denotes an IT-enabled service for multi-passenger vans. The routes are dynamically generated by the system based on the needs of the customers, and the passengers get picked up and dropped off at fixed points. (U.S. Department of transportation, 2020).

Shaheen and Stocker (2018) define different areas where the shared mobility influences the life of the users and residents living nearby.

• Transportation: shared mobility has a direct and sometimes even indirect influence on the travel behaviour of the users and people around. The utilization of personal mode of transportation differs as people are using ride sharing, or the kilometers travelled in private vehicles differ as users change earlier to a different mean of transportation. Even the emission of greenhouse gases may reduce, as people are using their cars less to get to work in a car by themselves.

• Land use: When using shared mobility, the land use changes, as less parking space in the downtown and denser populated area of cities might be needed due to the alternative mobility methods. New parks might be created out of the unused space. • Housing: As an additional result of the reduction in parking space, more housing

could be built within the cities.

• Economic development: People are starting to use their underused assets, and new working places could be created within the sector of shared mobility.

• Healthy lifestyles: shared mobility can encourage users to take the shared bike, or to walk to the next pick up spot for the ride sharing. It also generally motivates people to leave their car at home /or to not buying a car at all. Therefore, people are more likely to be more active using the public transport and the shared mobility system.

• Environmental reasons: Due to the possibility to reduce the greenhouse gas emission made by cars, shared mobility also offers climate advantages.

Those are different areas which impact the behaviour and the lives of the users of the shared mobility system by them interacting with the system and changing their behaviour, as well as the residents who might benefit from the system when parking spaces are being

reduced, and parks or housing will be created. Thebeforehand mentioned changes are

only positive ones, such as more housing space or less traffic and therefore less air pollution, while people could also be affected negatively from such a shared mobility system, as they might want to keep parking spaces downtown. Companies that profit from selling cars or services that provide parking space in the city centre might suffer even more from the new development.

As already mentioned before, everything within the area of sharing economy is considered a service and therefore everything within the area of shared mobility is also a service, as those all are ways to use another ones (underused) resources for the benefit of another party. (Lusch & Vargo, 2019)

Given the concept of shared mobility as explained above, we will consider all of the mobility related services in the city of Augsburg as a service mobility system.

2.4.1 Sidewalk Labs

One of the biggest companies in the private sector researching shared mobility is Alphabet. The Google lab for urban innovation organization is working on this topic, as presented in the 8th episode of their “City of the future” podcast. Quirk & Jaffe call a model of public transport and different sharing operators “mobility on demand” (Quirk & Jaffe, 2019). In this podcast, different solutions for urban mobility are discussed, and an interview with Sampo Hietanen the founder of the mobility concept in Helsinki, called Whim!, who coined the term MaaS (mobility as a service) is conducted. Whim! is “for

the people, for the users, it’s a promise of anywhere, any time, on a whim” (Hietanen,

2019). How it works is described as following:

Say you want to go from your hotel to a karaoke bar on the other side of town. So the app shows you a few options. And so you decide “I’m going to take a bike-share.” Then you’re halfway there, and maybe it starts to rain, and the bike-share doesn’t look like such a great decision. You dock up the bike and switch to a train. Now mind you, the app has paid for all of this. You don’t need to worry about downloading a new app. You don’t have to use any new fare payments into the kiosks. You just keep going on your journey. (Quirk & Jaffe, 2019)

Hietanen stated that people desire convenience and a high level of service and that this is the reason why many people take their own car instead of using a shared mobility service. Unless those services are offering the same level of convenience and service, they will not manage to disrupt the mobility status quo. (Hietanen, 2019)

2.5 Information Systems

An information system (IS) is part of an organizational system, consisting of components for processing, storing and collecting data (Zwass, 2017). This information system provides the organization with the information needed to carry out their operations and management (Geiger et al., 2012). The understanding of the term information system differs in the extend that some researchers interpret it from a very technical point of view while the majority of the IS community defines information systems as a combination of a technical and a social part (Geiger et al., 2012). This view is used in the thesis and will

2.5.1 Socio-Technical System

A socio-technical system consists of two parts, a social, usually human part and a technical part. The crucial thing is that one cannot separate the two parts because they only work together (Law, 2016). The system has the chance to use the knowledge and information generation potential from both the technical side as well as the human side. (Ure & Jaegersberg, 2005)

In literature, Ure and Jaegersberg (2005) defined four strategies on how to create value in a socio-technical system, namely: using a common platform, bridging the gap, creating new linkable between technical and human networks and aligning systems to create value. Using a common platform urges the creator to create the platform around the system, and not the other way round. The platform should include the whole system, and the user has to be able to use this platform. Bridging the gap means creating a system that addresses the social part as well as the technical part. In every system, there are differences on a spatial level, a language and understanding level, hierarchical level and so on. Those differences need to be overcome in order to create value within the system. Due to the advancement of the web in the last decades, many ways for coupling of technical and social aspects were generated. Creating new linkable between technical and human networks therefore opens up new spaces for social and technical transactions. Aligning systems to create value describes the importance of the awareness for problems and the alignment of different systems and knowledge bases. If a scenario occurs, which could have been avoided by having acquired more knowledge about problems, the creation of value has an obstacle. (Ure & Jaegersberg, 2005)

2.5.2 Experience Ecosystem

Zooming out of a socio-technical system, the theory of experience ecosystems is also important when aiming at defining a system.

Experience ecosystems, as defined by Remini and Lacerda (2016) and by that time introduced under the name of cross-channel ecosystem, have a clear focus on creating

and offering a positive experience to the actor, who is in the center of such a system. In later papers the name was changed from cross-channel systems to experience ecosystems. Actors, formerly known as customers or users, have a desired state which they are pursuing by completing different tasks. They are existential for any ecosystem, as they physically shape it. The tasks are any activities that they have to perform in order to reach their desired state. By completing the tasks, an actor has different points-of-interaction, called touchpoints. Those touchpoints can be digital or physical with a person, a website or even a supermarket. All touchpoints, which can be accessed by an actor, share a seam. On those seams, information is transmitted within the ecosystem. The experience an actor has progresses from one touchpoint to another via those seams. The seams can connect touchpoints in different channels. A channel is a specific layer filled with information about an ecosystem. That information can be about a specific area of the ecosystem, but it can also be broader and contain a whole ecosystem. (Resmini & Lacerda, 2016) Therefore, in order to improve the experience, an actor has, the information transmitted between the different touchpoints and channels needs to be transmitted into all relevant channels, so that the experience in each channel can be improved, resulting in an overall improvement. (Resmini & Lacerda, 2016)

2.6 Shared Mobility In Augsburg

Augsburg is a large city in the southwest of Germany and one of the three Bavarian metropolises. It is a university town with almost 30,000 students and a total of approximately 300,000 inhabitants. In Augsburg, a unique mobility concept was introduced that, to this date, does not exist anywhere else in Germany.

Stadtwerke Augsburg, the public utility company in the city, launched a new mobility concept on November 01, 2019. For the first time in Germany, there is a city-wide flat rate for various modes of transport, including public transport, bikesharing and carsharing. This model is called Mobil-Flat.

2.6.1 Stadtwerke Augsburg Organization

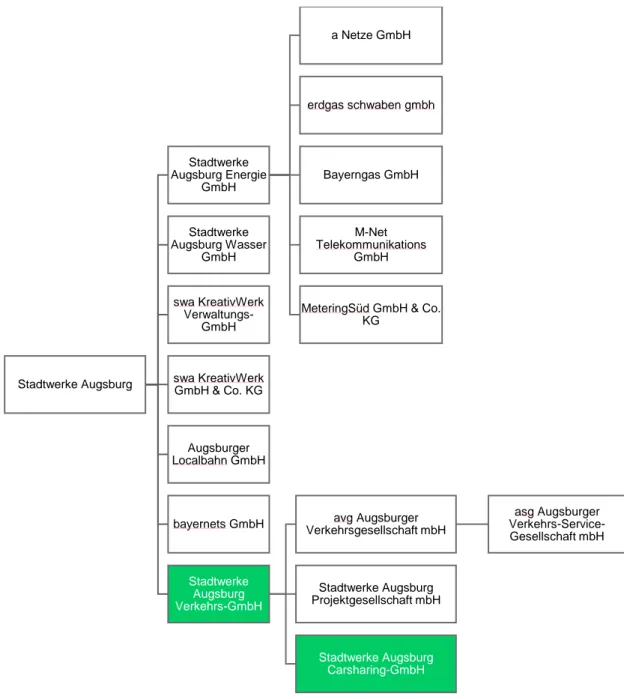

The Stadtwerke Augsburg have different subsidiaries which are working together in different areas. Stadtwerke is entirely a subsidiary of the city Augsburg. The organizational structure within the Stadtwerke is shown in the following organigram:

Figure 1: Location of Augsburg (Geodatenamt der Stadt Augsburg, 2020)

Figure 2: Structure of Stadtwerke Augsburg (Stadtwerke Augsburg Holding GmbH, 2020)

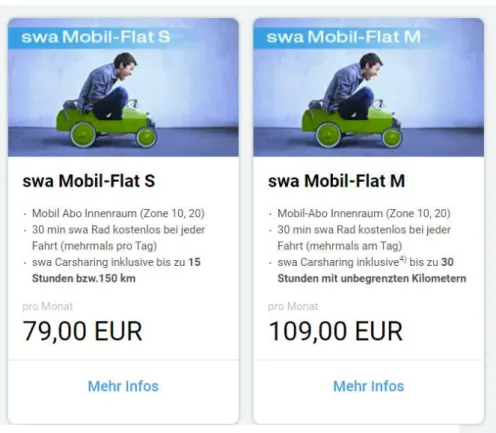

2.6.2 Mobil-Flat

With the flat rate, the customer can use public transport, bikesharing in the city and carsharing for a fixed monthly fee. The price depends on the desired carsharing kilometers and hours. Public transport can be used unlimited in the urban area called zones 10 and 20. For bikesharing, the first 30 minutes of each ride are free, and for carsharing, the

Stadtwerke Augsburg Stadtwerke Augsburg Energie GmbH a Netze GmbH erdgas schwaben gmbh Bayerngas GmbH M-Net Telekommunikations GmbH

MeteringSüd GmbH & Co. KG Stadtwerke Augsburg Wasser GmbH swa KreativWerk Verwaltungs-GmbH swa KreativWerk GmbH & Co. KG Augsburger Localbahn GmbH bayernets GmbH Stadtwerke Augsburg Verkehrs-GmbH avg Augsburger Verkehrsgesellschaft mbH asg Augsburger Verkehrs-Service-Gesellschaft mbH Stadtwerke Augsburg Projektgesellschaft mbH Stadtwerke Augsburg Carsharing-GmbH

kilometres. These two subscriptions are called Mobil-Flat S (15 free hours of carsharing) and Mobil-Flat M (30 free hours of carsharing) respectively.

Billing takes place monthly and is debited to customers at the end of the month. Customers of the Mobil-Flat will be charged additionally if the free hours or kilometers included in the package have been exceeded. (Biedermann, 2020)

2.6.3 Bikesharing

The bikesharing in Augsburg is carried out by nextbike. The bikes used in the area of Augsburg are branded as "swa bikes" but are the property of nextbike and operate according to their principle, which will be described in the following section.

For the Mobil-Flat, the bikesharing works as followed: When the subscription is completed, the customers’ accounts are activated for the bikesharing service. Registration with nextbike takes place online, via an app or via the hotline. Afterwards, the customer can use the bikes via the nextbike app. The website is branded with “swa-rad.de” as a product of the Stadtwerke. However, the rental and all other services take place via nextbike. (nextbike GmbH, 2020a)

The first 30 minutes of every trip are free of charge for Mobil-Flat customers, even if several trips are carried out per day. Thereafter, they pay the nextbike's regular tariff. If the duration of a trip exceeds 30, billing is made directly by nextbike after the ride. (Biedermann, 2020)

Based on the current contractual engagement, the swa has no insight into either the application or the booking system, thus functioning more as a customer than a provider. Therefore, the organization differs greatly from that of the car-sharing branch, where the swa is the driver behind the different advancements and developments, having autonomously created the booking and locking systems, as well as the app. (Biedermann, 2020)

During the COVID-19 pandemic, nextbike offers free 30 minutes per ride in Augsburg, and four other German cities to every customer, independent of the customer’s subscription. (nextbike GmbH, 2020c) (nextbike GmbH, 2020b)

2.6.4 Carsharing

The carsharing branch was founded in 2014 by the general traffic branch and had been offering carsharing from the swa brand ever since. (Biedermann, 2020)

Registration takes place either online, via the hotline or at the Stadtwerke service point, and the driver's license is identified in person at the customer centre. Since carsharing is offered directly by the Augsburg municipal utility and does not go through a second provider, it is only available in Augsburg. Customers pay a one-time registration fee (49 €) and a monthly fee (7 €). The price for every trip is based on the time, and the distance travelled. Depending on the size of the vehicle, the prices range from 1.60 € to 3.60 € per hour and from 0.18 € to 0.36 € per km. For long uses or rentals at night, the prices are slightly lower. Customer of the Mobil-Flat do not have to pay the registration and the monthly fee. (Stadtwerke Augsburg Carsharing-GmbH, 2020)

In addition to the offer for private customers, there is also an option to register as a business customer, as well as as a student. Students do not have to pay the registration or

The carsharing is divided into two parts, the free-floating carsharing, and the station based one.

2.6.4.1 Station-Based Carsharing

Station-based carsharing is the most widespread form of carsharing, also called “round trip” carsharing. The customer rents the car and picks it up from its parking spot, makes their trip and returns the car afterwards to the same parking spot. With this method, the provider usually has less work, as the cars do not get distributed over the whole carsharing area and need to be driven back to certain spots at the end of the day. Moreover, the distribution of cars at the station does not change with this method. Customers usually book the cars in advance to ensure there is a car available when they want to have one. (Le Vine et al., 2014)

In Augsburg and the surrounding area, there are currently 192 station-based cars on 82 stations.

2.6.4.2 Free-Floating Carsharing

A newer way of carsharing is the free-floating carsharing, also called “one-way” or “point-to-point” carsharing. The car can be picked up at one point and then dropped off at another one. This model is generally used more spontaneously, as the customer needs to check if a car is available at the moment at their current location. Due to the uncertainty, if there is a car close to a customer, pre-booking is not possible with free-floating carsharing. (Le Vine et al., 2014)

In Augsburg, there are nine free-floating cars in use. All those cars a e-cars.

2.6.5 Public Transport

In cooperation with the Augsburger Verkehrsgesellschaft (Augsburg Transport Association), swa offers public transport in the region in and around Augsburg. This

includes the region of Mittelschwaben (Central Swabia), which extends south of Augsburg. The public transport service consists of five tram lines, 27 city and six night bus lines. Every year, more than 60 million passengers use those public transport services. The swa offers different subscription plans for the usage of the public transport. A subscription means in this case an annual ticket. All the tickets listed below can be for different zones, which are different regions in and around of Augsburg. (Augsburger Verkehrs- und Tarifverbund AVV, 2020)

• Mobil-Abo 9 am: The Mobil-Abo 9 a.m. is valid Monday to Friday from 9.00 a.m onwards and all day on Saturdays, Sundays and on public holidays.

• Mobil Abo: This subscription is always valid and allows the user to take every mean of public transportation within the respective zone.

• Mobil Abo Premium: The Mobil-Abo Premium entitles the customer to take up to 4 children from 9.00 a.m. Monday to Friday and all day on Saturdays, Sundays and public holidays. Monday to Friday from 18 o'clock, on Saturdays, Sundays and public holidays up to 3 adults can be taken along.

Next to those forms of subscription, the customers can buy single monthly, weekly and daily tickets, as well as tickets for singles rides. Students of the university Augsburg get a “Semesterticket”, a student card with which they can use the public transport in all of Augsburg.

2.6.6 City Zone Augsburg

On 1 January 2020, the City Zone was applied in Augsburg city center. This model, under which the use of local public transport is free of charge in a certain area, is so far unique in Germany. The city of Augsburg and Stadtwerke Augsburg, which are jointly responsible for the introduction of the City Zone, hope that this will have various positive effects, as improving the air quality in the city centre by reducing motorised private transport. In addition, the measure is aimed at increasing the attractiveness of the city

centre, which could result in a strengthening of Augsburg's retail trade. (Stadtwerke Augsburg Holding GmbH, 2020)

2.7 Solutions In Other Cities

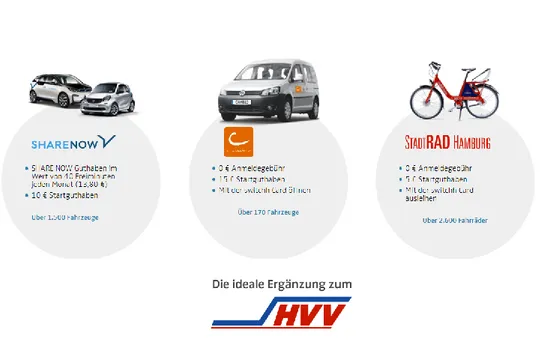

Other cities already have cooperation between public transport and mobility sharing providers. An example is the model “Switchh” in Hamburg, where customers have access to two carsharing providers and bikesharing for a monthly fee. Customers buy this service every month or as a subscription, yet still must pay for the individual use of car and bikesharing. Figure 4: switchh in Hamburg shows the pricing for the described model, where each service is billed separately peruse. Unlike the Augsburg model, where the user gets a certain amount of usage by paying a fixed price, switchh uses the pay-by-use model.

Figure 4: switchh in Hamburg (Hamburger Hochbahn AG, 2020)

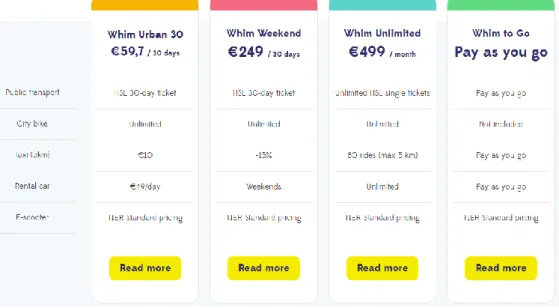

Outside Germany, the Finnish capital Helsinki implemented a similar model, in which public transport, bikesharing, taxi rides, rental cars and e-scooters are combined in one

service. Public transport and bikesharing are included for the flat rate models. Depending on the flat rate model, a discount on taxi rides and free car rentals (as provided by the provider, only on weekends or unlimited) is offered. E-scooter sharing always costs as much as with the original provider. The prices range between 57 € for 30 days and 499 € per month. In Figure 5: Whim in Helsinki , the different price models can be seen. In 2018 Whim started to expand to other cities and is available with the same principle (but different prices) in Austria, Singapore, United Kingdom (West Midlands), Belgium (Antwerp) and The Netherlands.

Figure 5: Whim in Helsinki (MaaS Global Oy, 2020)

Whim unites different providers in one service, as shown in Figure 5, while in Augsburg both bikesharing and carsharing are offered directly by the municipal utilities or under the brand of swa, which are also responsible for public transport.

Other that with Switchh in Hamburg, Whim is billing every service the customers are using together and they will only charge once a month, while Switchh bills after every use.

The Whim system and the Mobil-Flat are similar, in for example the monthly billing and the different subscription plans. The differences are that Whim offers a fixed price for certain services which still need to be paid per use, while the Mobil-Flat has a certain

amount included already. The Whim service can be used via one app, while in Augsburg there are (to this date) different app for the different services.

3. Methodology

A well-chosen methodology impacts the reliability of the conducted research and its results. Only if the philosophy, the research approach and the method are fitting for the purpose of the thesis, inaccuracies can be prevented (Saunders, Lewis, & Thornhill, 2009).

In the following chapter, the different parts of the methodology are investigated, and the reasons why the author chose different methods are explained in relation to the circumstances and the purpose of this thesis.

A closer description of how the secondary data was collected will not be done in this chapter, as it was already written out in 2.1 - Approach to Literature Review2.1.

3.1 Research Philosophy

Different researchers have varying interpretations of how they are understanding their surroundings and in conclusion, also their research. These distinct interpretations are called the research philosophy (Saunders, Lewis, & Thornhill, 2009).

To distinguish between different research philosophies, the way to look at those philosophies, the research assumptions, must be explained. There are three research assumptions, namely ontology, epistemology and axiology (Saunders, Lewis, & Thornhill, 2009). Ontology refers to the nature of reality, epistemology is about knowledge and what constitutes as acceptable knowledge in our social reality and axiology describes the judgement of the values and ethics in the research process (Babin & Zikmund, 2016).

The five major research philosophy approaches are called positivism, critical realism, interpretivism, postmodernism and pragmatism (Saunders, Lewis, & Thornhill, 2009). Positivism focuses on an observable social reality, hence on verifiable statements which are based on people’s experiences. The term critical realism describes the view on our experiences, taking the underlying structures of reality into account. The approach that

because they create meaning, is called interpretivism. Therefore, social research needs to be different from the research of natural sciences. The last major approach, pragmatism, values finding a practical solution and outcome more that finding abstract distinctions, in order to solve problems for future purposes. (Babin & Zikmund, 2016; Saunders, Lewis, & Thornhill, 2009)

The major philosophical research approach used in this thesis is the approach of interpretivism, as this approach allowed the researcher to generate primary data through interviews which then were used to analyse the system at hand and conduct recommendations for improvement. However, the author believes that a clear demarcation between the approaches is not entirely possible. Therefore, parts of the other approaches might also have an impact on the research. Therefore, parts of the other approaches may also have had an impact on the research.

Furthermore, the researcher is aware that by using the approach of interpretivism, the collected data could be interpreted differently by the interviewer than the interviewees intended their statement to be. Other researchers reading this thesis might come to different conclusions based on the interviews, and therefore the transferability of this research could be opposed. (Scotland, 2012)

The collected data and the analysis thereof were related to the social constructs and interpreted through culture and language (ontology). The knowledge, collected from the interviewed users is based on their perspective, feelings and personal views (epistemology). Furthermore, the author did the research without prejudices and in an objective way (as far as this is possible for a human being living in a social world) and interpreted the users’ narratives and formed them into a solution or suggestions (axiology). The researcher is aware of their subjective view.

3.2 Research Approach

In literature, there exist two types of reasoning, deduction and induction. The deductive approach describes the relationship between the theory and the conducted research. It is a top-down use of theory, as first, the authors identify the relevant literature and after building a framework based on that literature, the primary data is collected. The

hypothesis is established using the theory and afterwards investigated based on the collected data (Patton, 2015). A deductive approach is often used in quantitative research, as the collected data needs to be of a sufficient numerical size (Saunders, Lewis, & Thornhill, 2009).

Inductive research describes the process of concepts and theories emerging from the collected, most often qualitative, data. This approach is mainly used when there is no efficient theory to base the research on and when researchers aim to develop new concepts and want to explain broader theories and models (Patton, 2015).

This thesis used gathered research results wherefrom conclusions were drawn. Therefore induction is the chosen type of reasoning. The collection of primary data is the key point, and based on that data, the mobility service was modelled, and suggestions were made.

3.3 Research Design

According to Sauders et. Al. (2009) the research design can either be quantitative, qualitative or a mixture of both. The chosen design for this thesis is the qualitative research, as this research and its methods help the author to understand not only the people interviewed but also provides a way to grasp the context in which they live in, which is cultural and social. (Patton, 2015)

3.4 Data Collection Method

In order to collect the primary data for this thesis, the author decided to conduct semi-structured interviews with different actors within the system. A semi-semi-structured interview leaves enough room to respond to the interviewee's views, opinions, wishes and decisions, as the interview may have set questions but also the possibility to explore further into a direction that the interviewee named (Schultze & Avital, 2011). As the author wanted to leave enough room for the interviewee’s onions, ideas and views, this data collection method was selected.

The interviewees have been selected based on their different backgrounds and social groups. There was one expert interview with an employee of the Stadtwerke Augsburg Carsharing GmbH, who gave a profound interview to ensure an understanding of the different actors on the operator's side of the system. A business point of view was given, which the author noted, but the focus was still on the socio-technical part of the system. The majority of the interviewees was from the most relevant group, which includes the customers (people who already have a Mobil-Flat subscription), possible customers (people who are thinking about buying a subscription), customers in systems that are part of the bigger Mobil-Flat system (people who use only public transport, or only carsharing / bikesharing) and people who actively decided against using the subscription model. The participants for the (possible) customer interviews were contacted via the social media platform Facebook. The author published a post with a call to participate in an interview which does not take longer than 30 minutes. The post was be published in the groups called “Neu in Augsburg - Das Original” (English: new in Augsburg – the original) and “Universität Augsburg: Schwarzes Brett” (English: University Augsburg: Notice board). The groups were selected as the most used Facebook groups in Augsburg, which were not about the topics of renting, selling and buying and event tips.

In addition to the interviews, the primary data was based on observations and research, as the author observed the use of the system in Augsburg and online on their websites and applications.

3.4.1 Semi-Structured Interviews

To conduct semi-structured interviews, the seven guidelines suggested and developed by Myers and Newman were used. (Myers & Newman, 2007) In the following, these guidelines are presented as well as the applied to the interviews conducted for the thesis at hand.

1. Situating The Researcher As An Actor

The researcher is a female master student at a university in Sweden, but currently living in Munich, Germany. As a student herself, the interviewer might be able to talk to other

students in a way that makes them feel more comfortable than a professional researcher would. As the interviewer is German, the language of the interviews was German.

2. Minimise Social Dissonance

Reducing the social distance between the interviewee and the interviewer in order to improve disclosure is important. As the majority of the interviewees were students, and therefore on a similar social level as the interviewer, this is fulfilled. The interviews were held online due to the COVID-19 situation and restrictions in Germany (Presse- und Informationsamt der Bundesregierung, 2020), therefore external reasons for social distancing, e.g. clothing, were not important.

3. Represent Various ‘‘Voices’’

To avoid any elite biases, when interviewing only certain groups of people within a system, a mix of different groups should be interviewed. This was difficult, as the call for the interviews was published via Facebook, in groups with students and people living in Augsburg. Mainly students and professionals are in those groups, therefore it was not possible to avoid all biases.

4. Everyone Is An Interpreter

The interviewees themselves are interpreting their own world, as well as the interviewer. This can lead to adapted answers, especially since the experience of giving an interview via Skype is usually an artificial event. As the research philosophy is the interpretivism, the researcher is aware of the role that their own interpretation has, but also needs to be aware of the interpretation of the interviewees.

5. Use Mirroring In Questions And Answers

In order to make the interviewees feel more comfortable, the questions within the interview were worded, if possible, with phrases and words the interviewees used in their answer to the question before. This encourages them to describe their feelings and experiences in their own words.

6. Flexibility

The interviewer needs to be flexible, as a semi-structured interview allows the topic to explore different areas than the one the interviewer researched already. Furthermore, the interviewer needs to take their subject’s moods into account and react accordingly. This was a difficult task, as noticing different emotions via an audio call was challenging.

7. Confidentiality Of Disclosures

Every interviewee was made aware that the call would be recorded, and that all data used for the research would be saved without a name to identify the subject. The recording are stored on the researcher's flash drive, and appropriate steps to provide security are taken.

3.4.2 Textual Analysis

To use the results gained from the semi-structured interviews, the interviews were analysed with the method of indexing. This was done in six different steps (Brinkmann & Kvale, 2016): The author started by (1) reading the interviews carefully, and subsequentially on the second read-through (2) marked important words, phrases and sentences, called codes. Afterwards, (3) clusters were created, based on the codes, and the different codes were (4) sorted into those clusters. Those clusters were then (5) placed into more general categories, resulting in the existence of clusters and categories. The connection between those different categories and clusters was (6) described and afterwards, the categories could be ranked according to their importance and connection to each other.

The software ATLAS.ti was used to create the codes in the interviews as well as sort the different codes into clusters and afterwards into categories.

3.5 Limitations Of Methodology

While the method of qualitative research has many advantages for the thesis at hand, there are also disadvantages and limitations which need to be considered for the bigger picture

of this thesis. Having based this research on qualitative interviews means that the sample size is smaller than it would be for a quantitative research. Using semi-structured interviews meant that single interviews are not comparable; in contrast to fully structured interviews where a clear comparison between the different data sets would have been easier due to the fact that the questions are not personalized.

Using the philosophy of interpretivism also meant that the findings might not be transparent to other researchers, as the author interpreted the data based on their own background.

The sample size in this research is based on five interviews in total, where one expert interview was to collect data about the mobility system itself and not about the users view on this system. Therefore, four interviews are used to explain how the actor sees and perceives the offered Mobil-Flat and it’s components and what wishes and improvements there are. Contacting and collecting the users via the platform Facebook means that only Facebook users were addressed to give an interview, which already is a pre-selection of the participants. This pre-selection is based on the limited possibilities to reach users during the Covid-19 pandemic. The same applied to the number of people interviewed, as the author wanted to have a bigger sample group, which was not possible due to the fact that more possible interviewees could not have been reached out to in-person in Augsburg.

3.6 Ethical Considerations

Given the way the methodology has been used in this thesis and the way this research has been conducted, the only real ethical problem to the author is the treatment of the data coming from the interviews and how the interviewees have been treated. The interviews were held digitally and remote, therefore no physical harm was done to the interviewees and the author also did not harm them in any psychological way.

All the data that was collected by the author is treated confidentially. The author also considered the four ethical considerations when collecting the data, doing the analysis and writing the results. Those considerations are avoiding harm (and doing good),

Avoiding harm and doing good: The author did not have personal contact with any of the participants of the interviews. They paid attention to stay friendly and not hurt the interviewees in any psychological way. No names are published in this thesis and therefore, no career prospects might be hurt, or any damage to their reputation can be done. The author did not offer any incentives to the participants. The interviewee from the Stadtwerke Augsburg is the only one who can benefit directly from the findings of the thesis, as this research might offer some new finding to him, he was unaware of. The other interviewees participated voluntarily without any offerings (Spring 2020).

Informed consent: When asking for an interview and then again in the beginning of the interview, the interviewer explained to the participants the reasons for the research and why it is important. It was stated what the limitations of the use of the collected data is (there will be no monetary benefit made with their data) and who will get the results in the end (i.e. the University and Stadtwerke Augsburg). The author is aware of the difficulties of giving all information, therefore only the most important areas will be stated.

Right to privacy: The participants were informed that their name would be treated confidentially. In the thesis, only their demographic data is stated to be able to better interpret the answers given in the interview. The interviewees also needed to clearly state that they are aware and consent with the usage of their data for this thesis, as simply participating in the research does not automatically imply their consent.

Deception: The author clearly stated that the information in the thesis is only used to model the mobility system in Augsburg. All the participants are individual, different persons who took part in the interview out of unknown reasons. There was no incentive which might try to convince the participants to give certain, expected answers. There was no deceiving of the participants, and the research was only conducted as described to them.

3.7 Interpreting The Data

In order to interpret the data after getting the results from the interviews and the online research, different tools were used by the author. The selection of the tools was based on

the introduction of those tools in the Master programme Information Architecture and Innovation at Jönköping University as well as common literature within the field of information systems and mapping of ecosystems.

3.7.1 Customer Journey

Customer Journeys are a tool used in order to understand and afterwards improve the overall customer experience. That experience is conceptualized in a journey (Lemon & Verhoef, 2016), which displays the steps a customer goes through in the process of buying a product or using a service (Doyle, 2020). A customer journey map lists possible touchpoints a customer may encounter during their interaction with a service or during the purchase process. The actions the customers does during the process are also stated, as well as any other, influencing factors. The map is always from the view of the customer and therefore, is used to describe which experiences the customer has. It can be either emerging from collected data or prescriptive to show which customer experience is aimed for. (Rosenbaum et al., 2017)

The customer journeys conducted in this thesis were based on the interviews conducted as well as the author's observation about the sign-up process, as this was looked up step per step on the swa website.

3.7.2 Mapping The System

To map out the (eco)system, the thesis adopts the spatial syntax described by Lindenfalk and Resmini (Resmini & Lindenfalk, forthcoming) and developed from Willis' concept of "intent paths" (Resmini, 2012). An actor's experience is first described narratively, and then diagrammed as a path by means of a simple set of spatial conventions to convey the relative cognitive load of each step. Steps in the path take actors from one touchpoint to another: touchpoints are where actors interact receive, add, or modify information, and are represented by hexagon tiles. After all actor narratives have been diagrammed, they are compounded into one single ecosystem map. Contrary to paths, which describe an

concerns itself with the relationships between the participating elements. Therefore, this way of mapping does not make any difference between physical and digital touchpoints.

3.7.2.1 Individual Actor

The map is based on hexagonal tiles, where coloured tiles represent a touchpoint. Those touchpoints can be either personal (green), local (yellow) or remote (red). Personal touchpoints are at the immediate disposal of the user. Local is a touchpoint that is very close to the actor, may it be spatial or conceptual. If the actor needs little effort to use them, they are stronger (+), if they need more effort however, they are weaker (-). The red tiles are remote touchpoints, meaning the actor does not have them at their immediate disposal and has to either physically or conceptually cross a barrier to use them. The differentiation between stronger and weaker works on the same principle as for the local ones. (Lindenfalk & Resmini, 2019)

The touchpoints are arranged in a sequence based on the temporal order of the path. They are connected with arrows showing the direction in which the actor walks along the path. The arrows are located on grey tiles, representing the seams. They show the information flow that moves from one touchpoint to another. It is important to mention that those simple paths only represent the subjective view of one user and cannot be generalized. (Resmini & Lindenfalk, forthcoming)

Figure 6: Mapping ecosystems, based on (Lindenfalk & Resmini, 2019)

3.7.2.2 General Ecosystem

To map out the general ecosystem, the map is also based on hexagonal tiles.As for the

individual paths, the coloured tiles depict touchpoints and the grey tiles in between represent seams.

The information gained from the individual paths as well as the user interviews is collected, and a synthetic ecosystem is mapped. All touchpoints mentioned by the actors are then sorted into groups. Seams connect those groups of similar touchpoints, and there is a seam between different touchpoints if one actor mentioned it at least once. As a result, the mapped ecosystem looks like Figure 7: Synthetic Map , where the different colours represent the different groups.

There is a difference between the beforehand described emergent map and a prescriptive map. The prescriptive map shows the ecosystem in its designed state from the designer’s point of view, while the emergent map is from the actor’s point of view.

For this thesis, only an emergent map was conducted, as the views of the actor are the central point of the research.

4. Results

The findings of this research are presented in the following chapter. The first section shortly introduces findings from the interview held with the employee from the Mobil-Flat operator. Afterwards, the finding from the customer interviews are stated, and to better illustrate those findings, customer journeys were conducted based on those findings.

4.1 Interviews

For this thesis, the author interviewed one employee of the Stadtwerke Augsburg, who is responsible for the Mobil-Flat and the carsharing sector. This interview was used to further describe the mobility system and to get to know some actors better. Due to some technical problems, the interview was not recorded, but notes were taken.

In addition, four interviews were held with residents of Augsburg. Those residents are either subscribers to the Mobil-Flat, only carsharing users or people who actively decided against using the Mobil-Flat or even just the carsharing. The interviews with the residents were guided by a topic guide (see Appendix). All interviews were semi-structured, and therefore, each one had a slightly different focus, which usually was introduced by the participant.

Before the first interview with a resident in of Augsburg, the interviewer held a pilot interview with two carsharing users from Munich.

4.1.1 Interview Employee Stadtwerke Augsburg

The employee of the Stadtwerke Augsburg Carsharing GmbH, Jürgen Biedermann, is responsible for the carsharing and the development and implementation of the Mobil-Flat. The interview was held via a phone call. In the following, the results from the interview are summarized: