Oops! I Did It Again...

Exploring consumers’ post-purchase emotions in regards to impulsive

shopping and product returns online.

BACHELOR THESIS WITHIN: Business Administration NUMBER OF CREDITS: 15 ECTS

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: International Management AUTHORS: Elin Jönsson & Rebecka Ölund

2

Acknowledgements

First and foremost, the authors of this study would like to give the biggest and warmest thank you to everyone who has devoted their time and effort into this study.

To our tutor Jenny Balkow, who has supported us throughout this journey, being a guidance and providing us with expertise and knowledge within the field. We are grateful for the feedback that she has provided which has given us valuable insights for this research.

To all of the participants who agreed to contribute with their experience of impulsive shopping and provided the research with much valuable insights.

To our seminar group who engaged in discussions and provided constructive criticism in order for us to improve the thesis.

To Anders Melander from Jönköping University who provided clear guidelines and information for the Bachelor Thesis course.

_____________________ _____________________ Elin Jönsson Rebecka Ölund

3

Bachelor Thesis in Business Administration

Title: Oops! I Did It Again… Exploring consumers’ post-purchase emotions in regards to impulsive shopping and product returns online.

Tutor: Jenny Balkow Date: 2021-05-24

Key terms: Impulsive buying, post-purchase emotions, product returns, cognitive dissonance

Abstract

Background:

The expansion of e-commerce and online orders have led to companies creating new marketing strategies, where impulsive purchases are important in order to boost sales. However, this also has negative aspects concerning overconsumption and the environmental impact. Consumers are more likely to have negative post-purchase emotions when making an impulsive purchase, and thus are more prone to return products. This research aims at creating a deeper understanding about consumers’ post-purchase emotions after making an impulsive purchase and how a product return affects the post-purchase emotions.

Problem discussion:

Impulsive buying is critical for online stores and retailers are actively trying to increase these purchases for all customers, but at the same time, there is a growing number of product returns. This makes it important for firms to understand how consumers think and react to an impulsive purchase, since this supposedly has an impact on product returns. By providing a deeper understanding regarding the consumer’s post-purchase emotions one can specify such reactions on shoppers and help future marketing activities preventing consumers’ negative emotions in the purpose of increasing organizational profitability and decreasing the environmental impact. Purpose:

The purpose of this research is to build a theory that will provide organizations with knowledge about the chosen segment of Swedish women in the age 18-35 post-purchase emotions after impulsive buying. The findings of this study can contribute with additional insights to previous theoretical knowledge about post-purchase emotions after impulsive shopping.

Method:

This qualitative research has been conducted by using 14 semi-structured interviews with the chosen segment of Swedish females in the age 18-35 who had previously shopped impulsively online and returned products. For the data analysis, an interpretative phenomenological analysis was used, providing the research with reflections regarding the perspective of the participants’ experiences of impulsive shopping and their post-purchase emotions.

4 Results:

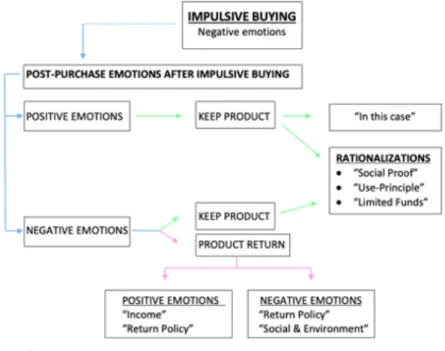

This research indicates that the participants generally held a negative view of impulsive buying, where they reduced/strengthened their post-purchase emotions through three rationalizations which were named by the authors “Social Proof”, “Use-Principle” and “Limited Funds”. When making a product return, the participants either had strengthened emotions or the negative emotions were turned into positive emotions. This was connected to three themes found by the authors which were called “Income”, “Return Policy”, and “Social and Environment”. The analyzed findings were presented in a developed framework.

5

Table of Contents

1. Introduction ... 8 1.2 Background ... 8 1.3 Problem Discussion ... 9 1.4 Purpose ... 10 1.5 Research Questions ... 11 2. Theoretical Background ... 112.1 Method for Theoretical Background ... 11

2.2 Impulsive shopping ... 12 2.3 External Triggers ... 13 2.3.1 Sales promotions ... 13 2.3.2 Social Identity ... 14 2.3.3 Trends ... 14 2.4 Post-purchase Emotions ... 15 2.5 Product returns ... 16 2.5.1 Return policies ... 17 2.6 Theory of Dissonance ... 17 2.7 Regret Theory ... 18 2.8 Theoretical Summary ... 19

3. Methodology and Method ... 20

3.1 Methodology ... 20 3.1.1 Research Philosophy ... 20 3.1.2 Research Approach ... 20 3.2 Method ... 21 3.2.1 Data Collection ... 21 3.2.2 Sample Selection ... 21 3.2.3 Semi-structured interviews ... 21 3.2.4 Interview Strategy ... 22

3.2.5 Interview Questions Design ... 24

6

3.2.7 Selection of Quotes ... 26

3.3 Ethics and Data Quality ... 27

3.3.1 Anonymity and Confidentiality ... 27

3.3.2 Credibility ... 27

3.3.3 Transferability ... 28

3.3.4 Dependability ... 28

3.3.5 Confirmability ... 29

4. Empirical Findings and Analysis ... 30

4.1 Summary of Empirical Findings ... 30

4.1.1. Products associated with impulsive buying ... 30

4.1.2. Emotions towards impulsive buying ... 31

4.1.3. Triggers ... 33

4.1.4. Post-purchase emotions when ordered ... 33

4.1.5 Post-purchase emotions when receiving the package ... 34

4.1.6. Product returns ... 36

4.2 Analysis of RQ1: “How do consumers reduce/strengthen their post-purchase emotions after making an impulsive purchase online?” ... 37

4.2.1 Dissonance Reducing Behaviour ... 38

4.2.2 “Social Proof” ... 39

4.2.3 “Use-Principle” ... 42

4.2.4 “Limited Funds” ... 44

4.3 Analysis of RQ2: “How does a product return impact the consumer’s post-purchase emotions after impulsive buying online?” ... 46

4.3.1 Income ... 48

4.3.2 Return Policy ... 49

4.3.4 Social and Environment ... 50

4.4 Proposed Framework and Explanation ... 52

5. Conclusion ... 54

5.1 RQ1: “How do consumers reduce/strengthen their post-purchase emotions after making an impulsive purchase online?” ... 54

5.2 RQ2: “How does a product return impact the consumer’s post-purchase emotions after impulsive buying online?” ... 54

7 6. Discussion ... 55 6.1. Theoretical contribution ... 55 6.2 Limitations ... 55 6.3. Future Research ... 56 References ... 58 Appendices ... 64

Appendix 1: Interview Protocol ... 64

Appendix 2: Interview Consent Form ... 65

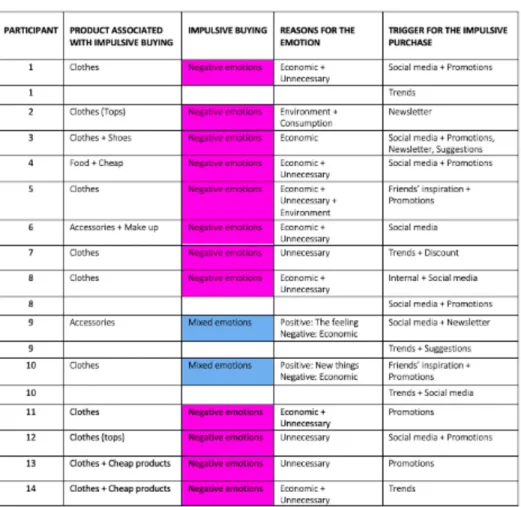

Appendix 3: Summary of Empirical Findings Table A & B ... 66

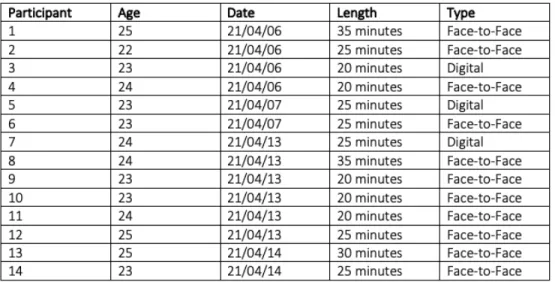

Tables & Figures Table 1: Interview overview ... 24

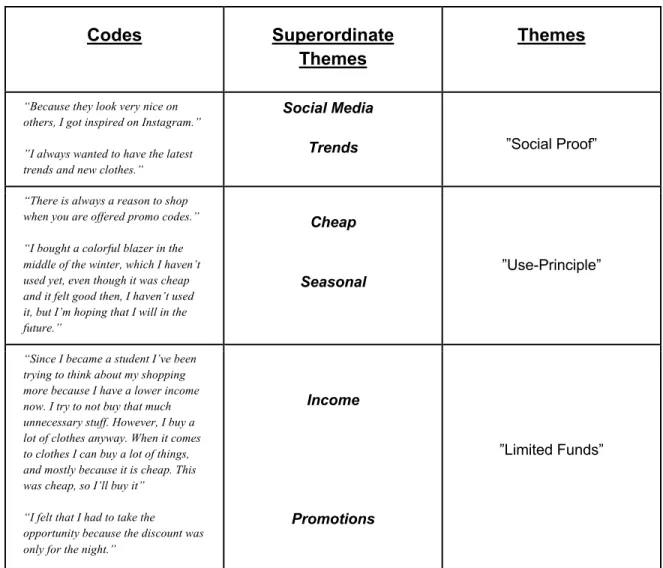

Table 2:Themes for Research Question 1 ... 38

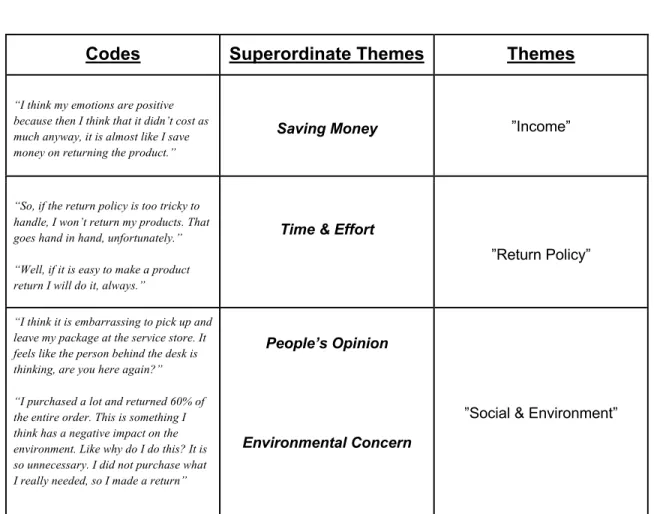

Table 3: Themes for Research Question 2 ... 47

Table 4: Summary of Interviews ... 66

Table 5: Summary of Interviews ... 67

Figure 1: Proposed framework regarding impulsive buying and post-purchase emotions and product returns. ... 53

8

1. Introduction

This chapter intends to provide background information about impulsive shopping online, further highlighting the post-purchase emotions after shopping impulsively and the possible consequences of a product return. Thereafter, a problem discussion is provided which aims to discuss the consequences of the post-purchase emotions after impulsive buying, followed by the purpose of this research, and two research questions.

1.2 Background

The expansion of e-commerce has increased globally over the past years and an increasing number of consumers are using the internet for shopping (Lissitsa & Kol, 2016). During 2020, 60% of the Swedish population increased their purchases online, where women stand for 69% of the total online purchases (Klarna Bank AB, 2020). Moreover, a study by Krishnakumar (2018) states that expenditure and purchasing of apparel have increased substantially in the last few years. In Sweden, the apparel industry is seen to be the most developed industry online and the most preferable industry for people in the age 18-35 (Klarna Bank AB, 2020). In 2019, the apparel industry had a yearly growth of 12% and a turnover of 12 billion SEK (Postnord, 2019). While in

2020, the annual growth for the apparel industry was 16% and the total turnover was 15 billion SEK, where covid-19 had a significant impact on e-commerce during this year (Postnord, 2020). The increase in online orders have led to companies creating new marketing strategies, where impulsive buying is critical for online stores and retailers are trying to increase the percentage of these purchases for all customers (Chen, Yeh & Lo, 2017).

Impulsive buying is a common shopping behaviour in the apparel industry (Hayat, Jianjun & Zameer, 2020), where Chen et al. (2017) states that almost 60% of online shoppers act on impulse and 40% of all online expenditures are impulsive purchases. Thus, many online retailers see impulsive purchases as important to boost sales (Chen, et al., 2017). There have, however, not only been positive aspects regarding the expansion of online shopping and impulsive buying in Sweden. The online apparel industry is the most affected industry regarding product returns, and the question about the environmental impact of this has been a very talkative topic (Chen et al., 2017). Therefore, during 2019 many online apparel organizations went from focusing on growth to instead focus more on profitability. Popular retail companies have started to take action concerning consumers with high proportions of returns, which could indicate suspension of purchasing

9

(Postnord, 2019). Furthermore, an impulsive purchase is often connected to a lack of consideration before a purchase, which makes consumers more prone to experience negative post-purchase emotions. This could lead to cognitive dissonance, where the individuals are more likely to return products (Cook & Yurchisin, 2017). Thus, consumers' post-purchase emotions are of importance for companies to understand.

1.3 Problem Discussion

This research will investigate consumers post-purchase emotions after impulsive shopping since this supposedly has an impact on product returns. According to the statistics (Klarna Bank AB, 2020) women represent a substantial part of the online shoppers, where people in the age 18-35 are those who most frequently purchase apparel online. This segment will therefore be used in this research in order to understand their shopping experience and post-purchase emotions after impulsive buying.

There are currently a huge number of quantitative studies examining the motives of impulsive buying, however, identified gaps have been acknowledged. Only a few studies have been conducted qualitatively on post-purchase emotions after impulsive buying. Evidence shows that online impulsive purchases are growing but at the same time, the product returns are also increasing. There is a growing importance for firms to understand how consumers think and react to impulsive purchases after the purchase, since this seems to affect their choice of making a product return. By getting deeper insights about consumers’ post-purchase emotions after impulsive shopping this can help companies find ways to minimize returns. This is relevant to examine since product returns are increasing and returns have a negative impact for individuals, organizations and society. Return of goods significantly damages e-commerce which makes this topic truly important to further analyze (Lim, Lee & Kim, 2017).

For individuals, impulsive shopping is seen to unsettle the previous normal decision-making models since the buying logical process of the customers’ activities is substituted with an irrational moment of self-gratification. Because of this irrational moment many items purchased due to impulsive purchasing are often considered as non-functional and unnecessary in regard to the consumers’ lives (Lim, et al., 2017). A lack of consideration before a purchase, makes consumers more prone to experience post-purchase regret. To decrease the negative emotions which follow,

10

consumers are also more likely to return products (Cook & Yurchisin, 2017). A quantitative study by Li, Yang, Cui, & Guo (2019) suggests that consumers can feel negative emotions such as regret, guilt, and dissatisfaction, as well as experiencing economic problems due to overspending of money. However, this study aims at understanding how consumers react towards these emotions. For firms, product returns have become an increasing cost and challenge, and thus affects organizations revenue streams negatively (Saarijärvi, Sutinen, & Harris, 2017; Lee, 2015). Moreover, on a society level, product returns are a problem due to overconsumption and the impact on sustainability (Li, et al., 2019). This means that product returns are not only an economic issue, but also extremely damaging to the environment since it leads to product waste and increased transportation (Frei, Jack, & Brown, 2020).

By providing a deeper understanding regarding the consumers’ negative emotions one can specify such reactions on shoppers and help future marketing activities preventing consumers’ feelings of regret in the purpose of increasing organizational profitability, and decrease the environmental impact (Prashar, Parsad & Tata, 2020). Therefore, this study aims at examining customers' post purchase emotions within impulsive shopping online.

1.4 Purpose

This research sought to build a theory that will provide organizations with knowledge about the chosen segment of Swedish women in the age 18-35 post-purchase emotions after impulsive buying. The apparel industry relies heavily on impulsive buying, therefore it is highly relevant to understand consumers' experiences and emotions of impulsive buying and the consequences of this in today’s digital society. The findings of this research can further contribute with additional insights to previous theoretical knowledge since it will investigate the unexplored post-purchase emotions after impulsive buying. This will be of meaning for organizations in order to minimize any negative post-purchase emotions which can lead to decreased product returns, and thus increasing company profits. Hence, also reduce the environmental impact of returns.

11

1.5 Research Questions

RQ1: “How do consumers reduce/strengthen their post-purchase emotions after making an impulsive purchase online?”

RQ2: “How does a product return impact the consumer’s post-purchase emotions after impulsive buying online?”

2.

Theoretical Background

This chapter starts with the method for the theoretical background, followed by previous literature which aims at providing background for the research regarding: impulsive shopping, external triggers for the impulsive purchase, post-purchase emotions which the consumer can experience after shopping impulsively, as well as product returns which can be a consequence of impulsive buying. Lastly two theories, cognitive dissonance theory and regret theory, are presented which aims at providing background for the thesis and will be further used in the analysis.

2.1 Method for Theoretical Background

A systematic literature review, aimed at assessing previous literature about the topic, was conducted through the search engine Primo at Jönköping University library and Web of Science. These two databases were used mainly because they were considered to have an extensive selection of journals and relevant academic literature.

The scope of the literature was limited to only viewing peer-reviewed journals mostly written between 2015-2021 due to their relevance of the topic, as well as in English. However, some articles were used which were not included in these indexes or in the time span, because of their appropriateness for the theoretical contribution to this research. Keywords that were used to find literature in the Primo database on the topic were ‘impulsive buying’ which resulted in 2145 results, to further narrow down the results, keywords such as ‘impulsive buying online apparel industry’ were used which gave 100 results, ‘impulsive shopping product return emotions’ resulting in 190 articles, and ‘impulsive buying post-purchase emotions’ resulting in 77 articles. The abstract and headlines were read in order to determine which articles were relevant for this research. Moreover, the articles were decided to fulfil one of the two conditions: either being in a journal listed in the Association of Business Schools’ (ABS) Academic Journal Guide 2018 or in

12

a journal listed in the Social Science Citation Index journal list (SSCI). This to ensure validity and reliability of the journals found.

2.2 Impulsive shopping

A common purchase behaviour within the apparel industry is impulsive buying which can be described as a shopping process without any kind of planning (Hayat, et al., 2020). An impulsive purchase can be defined as “when a consumer experiences a sudden, often powerful and persistent urge to buy something immediately” (Rook, 1987, p.191). Impulsive buying is distinguished by a strong desire and a lack of control. The impulsive purchase involves an intensive feeling of desire to buy a certain product where this desire becomes too strong so that the consumer loses self-control and immediately purchases the product to receive immediate gratification (Muratore, 2016).

The impulsive purchase is connected to a consumer's reaction to a stimulus in the shopping environment which results in an instant and unintended decision to purchase. After the purchase the consumer may have emotional conflict and/or cognitive emotions (Muratore, 2016). These purchases are not related to the rational decision-making process, in which the consumer engages in information seeking, but rather happens instantly without any engagement in finding information (Muratore, 2016; Kotler, 2000). The regular decision-making process consists of five stages including problem recognition, information search, evaluation of alternatives, purchase decision and lastly the post-purchase behaviour (Kotler, 2000). However, looking at the process of impulsive buying one can reverse this framework and only include the last two steps, hence, the purchase decision and post-purchase behaviour stages.

Previous research investigates the inducements to engage in impulsive buying and the motives and influences of impulsive shopping pre-purchase, where people who are materialistic tend to engage in impulsive shopping (Li, et al., 2019). Moreover, studies indicate that impulsiveness is a trait that contributes to impulsive shopping, where consumers with high impulsivity traits are more likely to engage in impulsive buying (Chen & Wang, 2015). Ek Styvén, Foster, and Wallström (2017), mentions that consumers with high impulsive buying tendency (IBT), are on average younger and females, which suits well with the chosen segment for this research. In addition,

high-13

IBT consumers perceive the internet environment as safe and have a higher intention to use e-commerce for shopping apparel.

2.3 External Triggers

Youn and Faber (2000) have identified specific external cues that can be seen as triggers to impulsive purchases. The external triggers that impact the consumers to make impulsive purchases include marketer-controlled and sensory factors such as sales promotions, displays and advertisement. Balakrishnan, Foroudi and Dwivedi (2020) states that promotional marketing activities and peer influence encourage the consumer to increase impulsive purchases. This is why sales promotions, social identity and the concept trends are introduced in this section.

2.3.1 Sales promotions

Dawson and Kim (2010) argue that companies who have implemented frequent sales, promotions and free gifts samples with purchases indicate a strong ability to affect the consumers’ behaviour in impulsive purchases and hence increase sales. The phenomenon of sales promotions and discounts is discussed by Balakrishnan, et al. (2020) to be a common marketing tool to sustain the attractiveness among new and existing customers both within the brick-and-mortar industry and among the online retailers. Lo, Lin and Hsu (2016) stated the sales promotions to be collections of motivations that affect the consumer to purchase various products within a short time period. Muratore (2016) further mentions that impulsive purchases are triggered by promotional activities whereas the consumer associates the products as not or less expensive. Looking at e-commerce platforms many marketers have developed promotional schemes that include membership programs and e-coupons that give the consumers exclusive benefits that influence the consumer to increase their purchase intention and feel exclusive among other non-member consumers. Moreover, the discount codes and coupons are defined to be a promotional marketing tool that creates payment value for consumers and is seen as external cues that triggers online impulsive purchases (Lo, et al., 2016). The valuable benefits a consumer can stimulate by shopping products on sales promotions are utilitarian and hedonic benefits. Utilitarian benefits are connected to the money saved by shopping on sales promotions, quality and convenience while hedonic benefits are linked to exploration, entertainment and value expression. Some phenomena of sales promotions that exists among e-retailers that encourage the utilitarian money saving benefit and

14

hedonic value creation benefits are promotions offers such as buy one get one free, clearance sales within limited time periods, free gifts with purchase, percentage discounts, purchase ideas that trigger curiosity about new arrival products and suggestions (Lo, et al., 2016).

2.3.2 Social Identity

Seo and Lang (2019) has defined the concept of social identity as being the individual’s perception of being included in a social community. The group belongingness can satisfy the neediness of self-esteem which outlines the individual’s behaviour and attitudes (Valaei and Nikhashemi, 2017). Moreover, people have a propensity of categorizing individuals into specific groups depending on characteristics that could be based on gender, age, or religion. Therefore, the natural instinct of the human being is to constantly observe social norms to avoid potential group and society exclusion (Seo & Lang, 2019).

The aspects of social identity can be related to the apparel purchases whereas customers are dependent on other opinions. Balakrishnan, et al., (2020) argue that group involvement has a significant impact on people during purchases. Valaei and Nikhashemi (2017) defines the young consumers to specifically be individuals that pursue group involvement and societal acceptance when selecting apparel purchases. Moreover, the younger consumers can be affected by peer pressure since they fear exclusion. Valaei and Nikhashemi (2017) have stated clothing to be a way for a person to express one’s impression of identity and belongingness of a group, which also can be described as basing one’s clothing style on group acceptance. This means that companies have the ability to affect the consumer’s process of identifying themselves. Individuals desire to be accepted by the society and are therefore persuaded to buy clothing trends that radiate belongingness (Valaei & Nikhashemi, 2017).

2.3.3 Trends

Todays’ apparel industry is constantly changing, and the clothing trends shift at a fast pace. The average time for a particular fashion trend to be trendy is calculated to be approximately 1,5-3 months (Valaei & Nikhashemi, 2017). Gupta, Gwozdz and Gentry (2019) argues that the companies within the apparel industry constantly reinforces the consumer's desire to make new purchases. This is due to the continuous newness of trends that the youth customers have a strong

15

desire to get to fulfill pleasure and self-identity. Moreover, the nature of the apparel industry is to convince and attract the customers to follow the repetitive new trends and styles (Valaei & Nikhashemi, 2017).

2.4 Post-purchase Emotions

Togawa, Ishii, Onzo and Roy (2019) states that satisfaction, delight, regret, pleasure, and happiness are common post-purchase emotions among consumers after impulsive shopping. Impulsive buying tends to cause a higher level of happiness and guilt than non-impulsive buying. An individual is more likely to experience mood changes when indulging in impulsive purchases, which is mainly due to differences between target and results. Whenever the target and results are being met, the consumer will have a positive mood, whereas if a consumer’s goal is not being met this can result in negative feelings such as regret and sadness (Li, 2015). Furthermore, Togawa et al., (2019) discusses the differences in post-purchase emotions of pleasure and guilt, where the emotion of pleasure is related to positive thinking of the purchase, such as happiness induced through self-indulgence. On the other hand, the emotion of guilt is related to the consumer experiencing pain and psychological problems referring to the aspect of covering financial expenses and losing self-control, which can create emotional conflict (Togawa et al., 2019). The conflict that arises between the desire and the lack of self-control can evoke a purchase regret, which encourages the consumer to avoid this type of purchase. This may initiate future control strategies in order to avoid these impulses (Muratore, 2016). Moreover, when consumers have negative emotions, such as regret or guilt, after shopping on impulse, they are more likely to feel dissatisfied with their purchase (Cook & Yurchisin, 2017). Research by Lim, et al. (2017) suggests that if consumers have negative post-purchase emotions after an impulsive purchase this often leads to complaining which affects the consumers’ willingness to return goods and the tendency of returning goods. Saarijärvi, et al., (2017) further states that when customers ordered a size that did not fit, they experienced frustration and negative emotions because they had to spend time and effort to return and reorder the products.

16

2.5 Product returns

Frei, et al., (2020) proposes that e-commerce has made it easier to shop impulsively because it is easier to return products. Ishfaq, Raja, and Rao (2016) suggests that product returns provide value for customers but also creates additional substantial costs for the firm which could lead to lower total profits. Furthermore, Mandal, Basu & Saha (2021) states that the level of product returns online in the US is estimated to be 30%. This involves high substantial costs for e-retailers and is calculated to be on an average $6-$18 for each product, including transportation and warehouse processing. These numbers explain why product returns are of significance for firms to minimize.

There are several reasons as to why consumers return products which has raised challenges for retailers, mainly because of its incapacity of offering consumers the usual benefit of touching and feeling the product prior to the purchase (Mandal, et al., 2021). Consequently, this online shopping challenge has increased the number of product returns because of the difficulties for a consumer to judge the aesthetic appeal of the specific product when purchasing online (Mandal, et al., 2021). Reasons for returning the product(s) are concluded to be dissatisfaction of requirements regarding fit, material and design (Mandal, et al., 2021), the products not matching the customers style (Saarijärvi, et al., 2017), and consumers intent to cope with their post purchase dissonance (PPD) to justify their purchase mentally and emotionally (Lee, 2015). Seo, Yoon & Vangelova (2016) also found the most common reasons for making a product return were poor fit, unsatisfactory performance, change of mind, finding another alternative/deal, and regret after impulsively buying. They argue that consumers consider their ability to make a product return even prior to a purchase. Furthermore, consumers might worry that they waste time, effort and costs associated with product returns. As well as psychological costs for instance, disappointment, regret and having to undertake new research (Seo, et al., 2016).

Another challenge for firms is that product returns have a major impact on the environment, due to additional transportation, product waste, and processing of trash (Morgan, Tokman, Richey & Defee, 2018). A product return often involves many areas, such as marketing and advertising, supply chain and logistics, customer service, accounting, waste management and recycling (Frei, et al., 2020). This shows that product returns affect many parts of the organization and is not only an economic issue but also an environmental problem.

17

2.5.1 Return policies

The expansion and development of online shopping has simplified the process of product return policies but as an effect of this the impulsive purchasing has become easier to complete (Togawa, et al., 2019). Seo et al., (2016), explains that the return policy matters for consumers when making purchases because they want to be assured that they can make a product return if they changed their minds. Customer satisfaction and long-term customer value is of importance when it comes to product returns. Hence, firms often offer generous return policies for their customers which in turn, increases customers’ willingness to purchase products online (Ishfaq, et al., 2016). Lenient return policies can help decrease the purchase uncertainty and risk for consumers, since they cannot physically touch and feel the products. But these policies can also increase product returns, which has major implications for firms when it comes to managing the ecological and environmental issues of online returns. Purchases do, however, generally exceed the number of returns and thus, retailers gain substantial benefits from having free returns (Saarijärvi, et al., 2017). On the other hand, Frei, et al., (2020), states that product returns are one major challenge for firms and that many underestimate the scope of this problem. The downside of free delivery and free return policies have created an unanticipated number of product returns, where many businesses are not aware of the true costs for the business (Frei, et al., 2020).

2.6 Theory of Dissonance

Festinger (1957), was the first to introduce the theory of dissonance, describing that individuals strive to have consistency among cognitions, which are knowledge, opinions, and beliefs about the environment, oneself and one’s behaviour. When there is inconsistency, an individual experiences psychological discomfort, namely, dissonance. Moreover, when this occurs, a person is likely to alter the state of discomfort and avoid any information or situation that increases the dissonance (Festinger, 1957). Gawronski (2012) argues that motivated reasoning to resolve inconsistency can bias beliefs towards desired outcomes. Therefore, individuals tend to rationalize their behaviour in order to minimize their dissonance (Festinger 1957).

The theory about cognitive dissonance is about how people make sense of their decisions and how they rationalize their behaviour according to what they believe. There are generally three ways to reduce dissonance; changing beliefs, changing behaviour, or changing perception of the action

18

(Festinger, 1957). The original theory was tested by Festinger and Carlsmith (1959), where they found out that individuals changed their opinions favorable to a point of view which they did not hold from the beginning when being forced to perform an overt behaviour. Moreover, Kelman (1953) found out that a smaller reward changed the opinion of the individual rather than a large reward. However, Aronson (1968) suggested that it was not inconsistency that caused changes in attitudes, but rather that the individual’s self-esteem was threatened by the behaviour.

The theory of dissonance is a well-known theory in psychology (Vaidis & Bran, 2019), contributing to an understanding of behaviour and attitude changes as well as the relationships between cognition, perception, emotion and motivation (Harmon-Jones & Harmon-Jones, 2008). The theory has also become popular in other fields, such as management and marketing, which is of importance for this thesis when it comes to post-purchase emotions and cognitive dissonance linked to impulsive shopping. Furthermore, Powers and Jack (2013) found out that cognitive dissonance is positively correlated to product returns and that cognitive dissonance creates a discomfort which individuals are motivated to reduce, which aligns with Festinger’s theory.

2.7 Regret Theory

Gelberg (2002) argues that the experience of regret can be seen as one of the most profound human emotions. A study by Zeelenberg and Pieters (2007) defines the word regret as the negative and cognitive emotion one experiences when recognizing that the outcome of a current situation could have been better as a result of making different decisions. Prashar, Parsak and Tata (2020) further states that the emotion of regret can be seen to be an unpleasant feeling where the person blames him- or herself concerning the decision and wishes to make the specific situation undone. Moreover, Tsiros and Mittal (2000) discusses that the decision of regret is the consequence of making the wrong decision even if the decision appeared to be the best option when it arose. This is evidence of how counterfactual thinking is related to emotions (Van de Ven & Zeelenberg, 2015). The feeling of regret in a purchase perspective of customer-satisfaction is discussed by Tsiros and Mittal (2000) to have an influence on the behavioural intentions. The outcome of the specific situation is evaluated in regard to not only other alternatives available within the market, but also the level of anticipation. The evaluation is considered to affect whether the consumer feels repurchase intentions or not.

19

Tsiros and Mittal (2000) argue that the regret theory was developed in terms of the unpleasant experience. The regret theory is established to explain rational behaviour as an alternative to the previous traditional expected utility model of decision making (Gelberg, 2002). This particular theory is according to Gelberg (2002) divided into two different assertions. Firstly, if a person evaluates possible outcomes of an action after a decision is made, the feeling of regret can arise due to the realization of better outcomes. Secondly, that people anticipate post-purchase emotions and thereafter modify preferences before the specific decision (Gelberg, 2002). For this study it is connected to the impulsive online shopping experience which according to Park and Hill (2018) is the fast and convenient alternative where customers are acting with reduced decision making. Moreover, Park and Hill (2018) state that an impulsive shopping experience is equal to less invested cognitive effort into the decision process, whereas the consumer as a consequence will experience regret as the post-purchase emotion. Furthermore, regret is of interest for post-purchase emotions since it is a moderately clear cognitive dimension, influenced by cognitive effort and also found to be persuaded by the reasoning of a decision.

2.8 Theoretical Summary

Throughout the extensive review of previous literature, it became evident that impulsive purchases and the importance of impulsive buying for companies have been discussed frequently. However, there are only a few studies who mention the post-purchase emotions in relation to product returns. Previous scholars have proposed that consumers are more likely to experience cognitive dissonance after making an impulsive purchase and that they tend to rationalize their decision in order to minimize the dissonance. In addition, regret theory states that the emotion of regret is a common post-purchase emotion that follows after impulsive buying, which can encourage consumers to make a product return. Product returns are considered to be a problem for companies both due to an economic loss but also because of the environmental impact it has. Therefore, the authors aim to investigate potential rationalizations that consumers might use to reduce cognitive dissonance when buying impulsively, as well as to better understand how the consumer’s post-purchase emotions are related to product returns.

20

3. Methodology and Method

In this chapter, the authors introduce the methodology which includes the research philosophy and the research approach. Moreover, the method for collecting data as well as the interview strategy and interview question design. Further, how the data is analyzed and how the quotes have been selected. Lastly, ethics regarding the data quality is outlined.

3.1 Methodology

3.1.1 Research Philosophy

The research philosophy for this thesis is interpretivism, where interpretivism “rests on the assumptions that social reality is in our minds, and is subjective and multiple” (Collis & Hussey, 2014, p. 44), and is defined as a response to positivism (Collis & Hussey, 2014). Interpretivism is a philosophy that interprets social reality and meaning-making where understanding is the focal point, clearly distinguished from positivism that focuses on prediction and explanation (Chandler & Munday, 2016). This suits well with this study since it aims to create a deep understanding about individuals’ emotions and experiences. An interpretivist study is structured based on subjective knowledge from participants, where patterns of the findings are identified to understand the phenomena. In addition, interpretivism is associated with using small samples to gather subjective ‘rich’ data in order to generate theories (Collis & Hussey, 2014), Thus, this research philosophy is appropriate because the objective is to understand individuals' perspectives on the subject and develop a theory about the consumers’ experience of impulsive buying and post-purchase emotions.

3.1.2 Research Approach

By explaining this study’s research paradigm one can conclude the research approach to be of inductive nature. Instead of testing previous conceptual and theoretical structures, also known as a deductive approach (Collis & Hussey, 2014), this research aims to develop a theory from empirical findings and observations. In this research the authors will observe the interviewees and analyze their answers in order to find patterns which can contribute to a new theory answering the research questions. This refers to creating an understanding of the experiences and emotions of Swedish females with regards to impulsive shopping and product returns. Henceforth, this will allow the research to move from specific to general patterns, something that is common for an

21

inductive approach (Collis & Hussey, 2014). Additionally, the inductive approach is considered as the most suitable for this research due to the lack of relevant theoretical frameworks explaining the post-purchase emotions of consumers after impulsive shopping as well as the connection to product returns. Hence, making a deductive approach less applicable to the research purpose.

3.2 Method

3.2.1 Data Collection

To gather primary data, interviews were conducted to provide rich and meaningful insights about the consumer’s emotions and experience in relation to impulse buying and product returns. Before collecting the primary data, a wide range of second-hand data had been collected about emotions and their relationship to impulsive buying and product returns. This was done in order to gain contextualization, something that is needed in order to understand the contextual framework of the topic as well as to enhance the authors’ sensitivity and to add to the interpretation of the primary data (Collis & Hussey, 2014).

3.2.2 Sample Selection

For this research a convenience sample was used consisting of Swedish females in the age 18-35 who had previously shopped impulsively online and returned products. Under an interpretivist paradigm, there is no need for the sample to be random since the data is not going to be analyzed and generalized to the whole population (Collis & Hussey, 2014). Therefore, the convenience sample was seen as appropriate. A convenience sample is relatively inexpensive and easy to gather (Tracy, 2020). This meant that the authors could easily find participants to include in the study. Furthermore, even if the sample was limited to students at Jönköping International Business School, the sample was considered to be suitable since there are students from different parts of Sweden who can contribute with different ages as well as a mix of backgrounds to the research. 3.2.3 Semi-structured interviews

Interviews were conducted with the chosen sample, consisting of Swedish females in the age 18-35 who had previously shopped impulsively online and returned products, where they were asked questions about their experience towards impulsive shopping and product returns. By having interviews one can understand what participants think, do, and feel (Collis & Hussey, 2014). The

22

interviews followed a semi-structured design, where some questions were prepared in advance (Appendix 1). Collecting in-depth semi-structured interviews is also compatible with an interpretative phenomenological analysis (Smith, 2017), which will be the base of the data analysis. In an interpretative phenomenological analysis, the interviews are structured in a flexible way where the interviewees are probed on the topics arising (Smith, 2017). This allowed for a general structure of the interviews but also gave room for new and follow-up questions providing deeper insights about the topic. An unstructured interview, meaning that questions would be made throughout the interview (Collis & Hussey, 2014), was avoided to ensure that the participants were not asked about completely different aspects of the topics. This would have made it difficult to analyze and find patterns. Furthermore, open questions were used to allow the participants to reflect before developing their answers. This was done to derive consumers’ opinions, attitudes and information about their experiences and feelings regarding impulsive buying and product returns.

3.2.4 Interview Strategy

For the interviews, the participants were first contacted online and then booked in for a meeting either face-to-face or online. Face-to-face is the preferred option when asking participants about sensitive topics (Collis & Hussey, 2014), and since impulsive buying and product returns can be linked to negative emotions causing sensitivity, the authors acknowledged that this might be the preferable option. Most interviews were held face-to-face at Jönköping International Business

School, for the sake of a familiar environment and the convenience of the authors’ and participants'

location. Due to the current situation of covid-19, the area where the interviews were held was prepared according to the health and sanitary restrictions. However, if the participant rejected the offer of having the interview face-to-face they could choose the alternative of having the interview organized through video calling applications, such as zoom, instead. Having a video conference also ensured that the authors were able to observe visible cues as if a face-to-face interview were being held. This explains why having interviews on the telephone was not an eligible option for this research because of the relevance of the consumers’ visible signals such as their body language in providing an understanding about their emotions. In addition, zoom interviews resulted in flexibility since the researcher did not need to travel in order to meet the other person, saving both time and costs. On the other hand, the downsides of having interviews online is that participants

23

must have access to the internet (Collis & Hussey, 2014), but this was not seen as a major issue since access to the Internet in Sweden is widely available.

One pilot interview was conducted to examine the relevance and the appropriateness of the research design, where some questions were changed throughout the interview to better fit the context. Both authors were present during the interviews to make sure that everything worked according to the plan of action where one researcher took notes while the other formulated questions. The notes included questions and answers, as well as the body language such as facial gestures which the participants showed. Recording is helpful to get a more robust and broad analysis (Collis & Hussey, 2014), therefore, to allow the authors to go back and review the interviews they were recorded through one telephone, with the participant’s permission.

After the interviews, they were transcribed and translated into English. The original interviews were made in Swedish since this is the authors’ native language and the participants were also from Sweden, making it easier to have a conversation where the interviewees could feel comfortable. Due to the translation, there might be some errors such as information loss or misunderstandings. To reduce this, both authors made sure to read the translations through and cross-checked it with the participant.

In total, 15 interviews besides the pilot interview were made with an estimated length of 20-35 minutes (see Table 1). One of the interviews was removed due to its lack of contribution for impulsive buying and post-purchase emotions. The participant could not think of any online impulsive purchases which made it difficult for the authors to use it for this study. The other 14 interviews were considered to contribute to the research where all 14 participants had relevant experiences and emotions towards the purpose of the research.

24

Table 1: Interview overview

3.2.5 Interview Questions Design

The interview was divided into four parts where the first part included some general questions about the participant’s online shopping behaviour. The second part was about an online purchase, the third part about impulsive shopping and the last part about product returns and the environment (Appendix 1). This order was chosen due to impulsive shopping is often associated with negative post-purchase emotions that in turn can lead to a product return. Furthermore, the authors were always meticulous to analyze the emotions conducted to the particular experience that the participant explained.

The first part included some general questions about the online shopping behaviour. Some questions, such as “Can you please describe your shopping habits online?” were asked. These general questions aimed to see if the participant was a frequent online shopper.

The second part was about the participant’s latest purchase online, and how the process was experienced, as well as what emotions they had in this process. Some questions, such as “Did you

add any product(s) that was not intended?” were asked in order to gain information which could

point to if a part of the purchase was made on impulse rather than thought through.

The third part centered the emotions after the impulsive purchase which provided the authors with information about the post-purchase experience and the emotions connected to the impulsive

25

buying. The aim was to let the participants develop their answers freely without being biased by the authors’ opinions. Therefore, broad questions such as “What is an impulsive purchase

according to you?” and “What were your emotions toward this?” were asked in order to see how

they perceived impulsive shopping without letting them know what the authors’ definition of this was. Doing this, allowed the authors to analyze the participant’s personal experience and definition of impulsive shopping and their emotions towards it.

The last part of the interview included questions regarding product returns as well as questions about consumption and the environment. Examples of the questions asked are “What are your

emotions towards making a product return?” and “What were your emotions when making a product return?”. These questions provided information about how the participant’s viewed

product returns and their emotions towards making one.

Moreover, probes were used throughout the interview to allow the participants to elaborate on their answers in order to understand the information correctly and gain the most of the interview (Collis & Hussey, 2014). Examples of the probes which were used are “Can you explain this again?” and “Can you give any examples of an impulsive purchase?”.

3.2.6 Data Analysis

The interviews were analyzed through a phenomenological analysis which aims to clarify and understand the consumer experience of impulsive shopping and post-purchase emotions. Phenomenology can be explained as modes of appearing, which means that an experience, idea, emotion and memory can be seen in different perspectives by different people. In other words, a situation is experienced in different ways, which makes it important to gather multiple perspectives to provide a whole phenomenon (Bevan, 2014). Additionally, this study used an interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) which is a part of the phenomenological psychology approach that in detail concerns an investigation of individuals’ personal experiences. IPA is mainly based on phenomenology, hermeneutics and idiographic, focusing on individuals’ experiences. It involves a double hermeneutic, meaning that the authors will try to understand the participant’s sense of their world (Smith, 2017). It mirrors a creative and imaginative research approach and is counted to be one of the most established approaches for qualitative research (Willig & Rogers,

26

2017), which makes it highly relevant for this thesis. The detailed investigation of individuals firstly requires a personal in-depth analysis with the chosen participant (Willig & Rogers, 2017), which in this case was through qualitative semi-structured interviews. Thereafter, the interviews are further transcribed and then analyzed by examining in detail for each participant's experiential themes, and then by patterns across the interviews (Smith, 2017).

The transcribed interviews were intensively worked through and coded based on the participant’s experiences and emotions by both authors separately, then compared with each other. The coding that each author had made was discussed back and forth in order to understand the participant’s reality. Patterns across the emerged codes were looked into which involved similar emotions, thoughts and experiences about the participant’s post-purchase emotions after impulsive buying. These patterns presented abstract realities about the participant’s understanding of the phenomena studied. An example is that one participant (P1) avoided impulsive shopping and had a rule for doing so. This was interpreted as the participant having a negative view of impulsive buying since the participant felt a need to avoid it. The patterns that appeared were then called themes. From the coded data there were ten superordinate themes that were derived, which were then combined into six main themes. All of these were put into two tables in order to provide clarity of the themes found (Table 2 and 3). By using IPA, this research provided in-depth reflections about the perspectives of the participants’ experiences of impulsive shopping and their post-purchase emotions.

3.2.7 Selection of Quotes

The usage of quotes represents the participants’ experiences and can help the reader to evaluate the accuracy of the analysis as well as provide richness to the findings (Eldh, Årestedt & Berterö, 2020). The reason for using quotes in this research is to create transparency and to strengthen the empirical findings. The transparency is aimed at allowing the reader to interpret the participants’ post-purchase emotions after impulsive buying and to show how the authors of this study have interpreted this.

All participants that were included in the research had valuable insights for the final result. But as can be seen in the distribution of selected quotes some participants’ quotes were used more than

27

others. However, this does not mean that other participants’ quotes were less interesting or less valuable. The quotes have been chosen without any reflection on which participant had expressed it, but rather because of how they were worded.

3.3 Ethics

and Data Quality

3.3.1 Anonymity and Confidentiality

The ethics of this research have carefully been considered to keep a professional approach. The concepts of anonymity and confidentiality are seen to be closely connected in business research whereas the contributors of the particular research need to be informed about before their participation (Wiles, 2013). The definition of anonymity can be explained as the guarantee the participants and organization are given in regard to ensuring that their name will undoubtedly not be named in the research (Collis & Hussey, 2014). The authors could ensure anonymity in the study by letting every participant of the interviews sign a consent form (Appendix 2). Instead of using personal information such as the participant’s name the authors changed their identity to numbers only. Henceforth, the participants were also provided with the information about what will happen to the data collected and how it will be reported. This is explained as confidentiality which is connected to the protection of data and information collected from the participant (Collis & Hussey, 2014). In this study it is unmanageable to identify from whom the data were collected, which according to Wiles (2013) implicates a safe zone of private information. By specifying the anonymity and confidentiality participants can in general radiate greater openness and freedom of expression in their answers during the conducted interviews (Collis & Hussey, 2014). This resulted in a more pleasant interview environment where participants could more freely express personal opinions and emotions regarding their experiences of online impulsive shopping and product returns.

3.3.2 Credibility

To ensure that the research holds credibility, meaning that the subject was correctly identified and described (Collis & Hussey, 2014), the authors were both involved and observant in the process. Due to that the authors were equally involved in the process of conducting the literature review, designing interview questions, interviewing, coding and analyzing the findings helped to create valuable and extensive knowledge about the topic. This understanding of the topic allowed the

28

authors to verify the interview technique and interview questions through one pilot interview that were made in order to ensure the accuracy and appropriateness. To increase credibility, the information gathered can be cross-checked with others, known as analytic triangulation (Collis & Hussey, 2014). This was done with the transcripts to ensure that they have been correctly translated and analyzed. When analyzing the findings, the authors linked the primary data to the previous research, which resulted in a back-and-forth process of analysis, making sure that the findings were presented in a truthful manner.

3.3.3 Transferability

The transferability of a research refers to whether particular findings of the study can be applied to other situations (Collis & Hussey, 2014). This means that the authors have the responsibility to provide information regarding the number of participants taking part of the study, potential restrictions, data collection methods, and length of data collections sessions (Shenton, 2004). By providing the thickness of details in the primary data collection the authors can develop a baseline understanding which can help future investigators to transfer the empirical findings into new situations (Nowell, Norris, White & Moules, 2017). Since this research has been conducted qualitatively on a small sample size and a restricted geographical area, it could be difficult to replicate. However, the authors of this study aimed to provide detailed information for the data collection. But it is up to the future researchers to evaluate the transferability (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). This means that future researchers can apply the same process into new situations, but it is important to take the chosen segment as well as the industry into consideration, since this particular case has gained meaningful indicators for the female student consumer within the apparel industry only.

3.3.4 Dependability

Dependability refers to feasibility for future studies to repeat the work and thereby end up with similar or the same result as this study. This means that the research must include transparency including a well-documented research process to increase the understanding and chances for other authors to follow the same structure (Shenton, 2014). In order to increase the dependability, it is of importance to develop a study that ensures a logical, traceable and clearly documented research process (Nowell, et al., 2017). In this research IPA was carefully used whereas the authors developed the framework structure of the interview questions where no personal opinions nor

29

information from previous literature were used. To increase the dependability of the research, the primary data only contains information regarding the participants’ own observations and experiences of impulsive shopping, post-purchase emotions, and product returns. Furthermore, the process of data collection included audio recorded interviews where both authors participated. Thereafter the interviews were transcribed and examined by both authors to improve the dependability.

3.3.5 Confirmability

The definition of confirmability refers to that the research process is fully described and that the presented data are derived from empirical findings (Collis & Hussey, 2014). Confirmability within the qualitative approach refers to the author's objectivity when analyzing the collected data (Shenton, 2004). Furthermore, Nowell, et al., (2017) concludes that a research with strong credibility, transferability and dependability ensures the research with high confirmability. The findings should be results of personal experiences and ideas from the chosen participants rather than biased preferences and characteristics from the investigators (Shenton, 2004). Triangulation is a way to increase the confirmability (Shenton, 2004), which was done during the coding process to ensure that the empirical findings were presented objectively. Furthermore, both authors coded the data separately and then checked it with one another. This also helped with avoiding biases and personal opinions of the researcher. The research also included quotes from the interviews to show that the empirical findings were the participants’ experiences and emotions.

30

4. Empirical Findings and Analysis

This chapter provides the empirical findings and the analysis of the interviews. First, a summary of the empirical findings is presented which summarizes the conducted interviews. This includes brief presentations of products associated with impulsive purchases, emotions towards impulsive buying, triggers, post-purchase emotions, and product returns. Thereafter, the analysis of the empirical findings is presented which involves information to answer the two provided research questions. Firstly, an analysis regarding research question 1 is presented with the developed themes within dissonance reducing behaviour: Social Proof, Use-Principle, and Limited Funds. Secondly an analysis regarding research question 2 is presented with the developed themes concerning product returns: Income, Time & Effort, and Social & Environment. Lastly, a proposed framework with explanation is presented.

To understand the emotions of each participant regarding impulsive purchases the findings are results of the participants’ characteristics of experiences, ideas and emotions. The data analysis has been made with IPA which generated into 10 subordinate themes, and 6 themes presented in Table 2 and 3, where the data analysis aimed to answer the research questions:

• RQ1: “How do consumers reduce/strengthen their post-purchase emotions after making

an impulsive purchase online?”

• RQ2: “How does a product return impact the consumer’s post-purchase emotions after

impulsive buying online?”

4.1 Summary of Empirical Findings

4.1.1. Products associated with impulsive buying

When asking each participant about impulsive purchases the majority associated the purchases to be products within the apparel industry and most often clothes (Appendix 3). This further supports the choice of the clothing industry when investigating impulsive purchases. Participants (P2, P4, P13, P14) also pointed out that impulsive purchases most often included products that were considered as low priced and cheap. To exemplify, this is what participant 10 and 12 expressed:

“I would say clothes. You become excited and don’t think before making the purchase. I think you plan more expensive purchases and think one or two days extra before ordering it.” - P10

31

“Maybe clothes, such as tops. Not that expensive things. Especially not for me, I might see a cute top or a pair of cheaper pants or shoes. Something that I might not fully have an outfit thought

through.” - P12

4.1.2. Emotions towards impulsive buying

Rook (1987) defined impulsive purchase to be “When a consumer experiences a sudden, often powerful and persistent urge to buy something immediately” (Rook, 1987, p.191), which suits well with the participants’ idea of impulsive buying. A quote from Participant 14 demonstrates this:

“You buy something that was not planned or something that you haven’t thought about that you need or want. You see it and buy it instantly without thinking it through.” - P14

Generally, when speaking about impulsive purchases, the participants brought up negative experiences, or stated that “in this case” the impulsive purchase was good, which points to that the participants have negative emotions towards impulsive buying (Appendix 3). An example of “in this case” is expressed by Participant 5:

“I was very happy and pleased about the purchase. In other cases, I often feel negativity and not happy at all, almost anxiety, but in this case, I was very happy about it. I felt that these shoes

were necessary in some way” - P5

The negative aspects toward impulsive purchases were conducted to be unnecessary purchases of products that were not needed but in that particular situation highly wanted. These quotes by participant 2, 5, 12 and 13 highlights that impulsive purchases can be considered to be unnecessary purchases:

“It is when you are ordering something that you are not supposed to or that you don’t actually need.” - P2

“Yes, my Levi’s jeans, I bought them last week which was unnecessary because I have a pair that is very similar already, but somehow I bought them anyway.” - P5

“That you don’t think it through and it is maybe something that you don’t really need, but really want.” - P12

32

“It is when you don’t have a thought about buying something and not a need for it, but you find yourself in a situation where you like something very much and buy it without even having a

thought about the purchase. So, it is spontaneous.” - P13

Other evidence that showed the negative approach the participants had toward impulsive purchasing was concluded to be the avoidance of the behaviour. Participant 1 expressed this:

“The reason for the 24h rule is because I was the queen of impulsive buying and I spent a huge amount of unnecessary money on products I don’t need.” - P1

This quote shows that Participant 1 had created a rule, named the 24h rule, in order to avoid impulsive buying. The 24h rule helps the participant think about the necessities and benefits of the products for 24 hours before purchasing it. The rule was motivated by that the person would not be able to stop oneself from purchasing otherwise, which indicates that the participant has a negative approach towards impulsive buying (P1).

Two other quotes which exemplifies the negative approach towards impulsive buying are expressed by participant 3 and 6:

“If you have signed up for a newsletter you get a lot of inspiration and it is easy to make impulsive purchases. When I started my bachelors’, I decided to unsubscribe from many brands

to avoid my impulsiveness to save money.” - P3

“I have unsubscribed from all different brands and companies to avoid newsletters that attract my interest into making impulsive purchases.” - P6

Both Participants 3 and 6 state that they have unsubscribed from newsletters to avoid buying on impulse which is interpreted as they see impulsive purchases as something negative. The implemented control strategies by Participant 1, 3 and 6 strengthens what Muratore (2016) stated previously about emotional conflict when making impulsive buying. Impulsive buying can cause purchase regret due to a lack of self-control which encourages consumers to avoid this behaviour and thus initiate control strategies (Muratore, 2016).

33

4.1.3. Triggers

The findings showed that the participants had negative emotions towards impulsive buying, but due to external triggers the participants were encouraged to make a purchase anyway. These triggers created an urge to buy on impulse, where the individuals made fast decisions without thinking them through. The most frequently mentioned triggers by the participants in this research were social media, sales promotions, trends, newsletters, suggestions, and friends. The trigger ‘Social media’, especially Instagram, were often in combination with promotions (Appendix 3). Here are quotes from Participant 4, 10 and 11 who expresses how their purchase was affected by triggers:

“Yes, it was last week when I bought a pair of new sneakers. I saw someone on Instagram and felt like “Wow they looked really nice” so I really felt like I needed them. They were also on

sale...” - P4

“I ordered it because I like cheap prices, and later that day when I ran into my friend she said that H&M had started with their seasonal sale so I had to go back to their website and found

even more products that I purchased the day after.” - P10

“Because I had been inspired on social media to purchase two dresses, and then I saw on the website that they had a lot of nice things, so I ended up ordering 12 pieces, instead of only 2

dresses.” - P11

These quotes strengthen the assumption that the participants were influenced by triggers when making the impulsive purchase, which suits well with previous literature by Youn and Faber (2000) who stated that marketer-controlled and sensory factors impact the consumer to make impulsive purchases.

4.1.4. Post-purchase emotions when ordered

Previous research by Muratore (2016) stated the impulsive purchase to be within situations where the individual has tendencies of losing self-control and makes unplanned and spontaneous purchases for immediate gratification. The findings of this research confirm this statement where 12 of 14 participants had positive emotions such as excitement immediately after the impulsive purchase as shown in Appendix 3. The most frequently mentioned post-purchase emotions directly