DOI: 10.4018/IJSR.2017010102

Copyright©2017,IGIGlobal.CopyingordistributinginprintorelectronicformswithoutwrittenpermissionofIGIGlobalisprohibited.

Motives for Participation in Formal

Standardisation Processes for

Geographic Information:

An Empirical Study in Sweden

Jonas Lundsten, Malmö University, Malmö, Sweden Jesper Mayntz Paasch, Universty of Gävle, Gävle, Sweden

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this article is to investigate the personal motives for participation in formal standardizationprocessesforgeographicinformation.Themethodinvolvedinterviewingmembers oftechnicalcommitteesattheSwedishStandardsInstitute,SIS.Theresultsarethatthemajorityof theintervieweesareverymotivatedintheirworkandtheythinktheirparticipationiswell-financed bytheirorganizationsallocatingthemtoatechnicalcommittee.Themainmotivesaretocontribute todevelopmentofsocietyandbeattheforefrontofdevelopment.However,thisarticlealsoshows thatseveralmembersparticipatinginthisstudyfeltthattheydonothavesufficienttimeforworking withtasksrelatedtotheirtechnicalcommittees.Theirdailyworkintheirrespectiveorganizations oftenhashigherpriorityinrelationtostandardizationwork.Thiscontrastswiththeorganizational goalsoftheparticipatingorganizationsandmayslowdownthedevelopmentofstandardsandother publicationsduetolackofresources. KEywoRdS

Cultural Historical Activity Theory, Geodata Infrastructure, Geographic Information, Motivation, Motivation in Projects, Project Management, SIS, Standardization, Swedish Standards Institute

INTRodUCTIoN Thisarticleexploresmotivesforparticipationinformalstandardizationprocessesforgeographic informationinSweden.Geographicinformationisacommontermforinformationdescribingthe physicalworldaroundus(forexamplebuildings,roads,forestsandadministrativeboundaries,and e.g.presentedonmaps)andrelatedinformation.Toparticipateinaformalstandardizationprocess mayrequirehugeresourcesfromtheparticipants(Riillo,2013).Standardsarehowevernot“trade secrets”,butavailableforothers,suchascompetitors,forafeeafteracceptancebythestandardization body.Themotivesforparticipationinstandardizationprocessesdothereforenotsolelyrelyonthe protectionofideasforthecompaniesinvolved,butcanalsoforexamplebemotivessuchastoshare technicaland/orstrategicknowledgeand/oraccesstomarkets(Bild&Mangelsdorf,2016;Riillo, 2013),thusgainingeithertechnicaland/oreconomicadvantages.

Geographicalinformationhasgainedmuchinterestduringthelastdecadesduetotheincreased useandexchangeofdigitaldatadescribinggeographicalandadministrativefeatures.Standardsand relateddocuments,suchastechnicalreports,playanimportantpartinthis.Examplesarethetechnical guidelines(dataspecifications)specifyingcommondatamodels,codelists,etc.,tobeusedwhen exchanginggeographicdatasetsinaccordancewiththeEuropeanINSPIREdirectiveprovidinga spatialinfrastructureforEurope(Europeanunion,2007).Thebenefitsofstandardizationinthefield ofgeographicinformationarewellknownandthedevelopmentofformalstandardshavebeenin focusforseveralyears,e.g.byprivateandpublicstakeholdersparticipatingintechnicalcommittees, TC,attheSwedishStandardsInstitute,SIS,formorethantwodecades1. Theauthorshavenotidentifiedresearchonhowindividualsaremotivatedinstandardization workingeographicinformationandhopethisarticlewillbeacontributiontothisfieldofstudy. Thereisalongtraditionforimplementinginternationalstandardsforgeographicalinformation andtodevelopnationalstandardswheninternationalstandardsarenotavailable.Examplesarethe InternationalOrganizationforStandardization’s[ISO]19100seriesofstandardsforgeographical information,i.e.specifyinghowtodescribegeographicinformation(ISO,2014),theSwedishstandards forapplicationschemasformunicipalzoningplans,SS637040:2016(SwedishStandardsInstitute [SIS],2016)androadandrailwaynetworks,SS637004:2009(SIS,2009).Swedenhasrecently adoptedanationalstrategyforadvancedcooperationforopenandusablegeographicinformation viae-services(Lantmäteriet,2016).Thestrategystate,amongotherthings,thattheuseofstandards isofmajorimportanceforachievinganeffectiveinfrastructurefor,amongothers,dataexchange, digitizationofpublicadministration,moreeffectivesocialplanningprocesses,defenseandcivil contingencies.Standardsareinotherwordsanimportantpartofthenation’s“invisibleinfrastructure”, atermcoinedadecadeagobytheSwedishgovernmentinregardtoincreasedcooperationconcerning ITstandardizationinthepublicsector(Swedishgovernment,2007). StandardizationinthefieldofgeographicinformationisacentralpartintheSwedishlanduse andplanninginfrastructureand,forexample,playavitalpartinthenationalSwedishstrategyfor geographicinformationinfrastructure2016-2020(Lantmäteriet,2016).Anexampleistheinitiative providinggovernmentalagencies,municipalitiesandotherorganizationseasyaccesstodatawithinthe Swedishgeodatacooperationinitiative.2Athirdexampleillustratingtheimportanceofgeographical informationstandardsisthefinancialagreementbetweenSISandLantmäteriet,theSwedishmapping, cadastralandlandregistrationauthority,allowingthefree-of-chargeuseofanumberofstandards withintheSwedishgeographicinformationsector(SIS&Lantmäteriet,2017). Research Question Thisarticlepresentstheresultsofaninvestigationregardingparticipants’personalmotivesfor participatinginformalstandardizationworkattheSwedishStandardsInstitute,SIS,concerningthe productionofstandardsandrelateddocuments(suchasnationalprofilesandotherpublications)for geographicinformation.TheSwedishStandardsinstitute´sTCforgeographicinformationstatedin 2012thatitsometimesisdifficulttorecruitnewparticipantstothetechnicalcommittees(SIS,2012). ThisisalsoanobservationsharedbyoneoftheauthorsafterhavingbeeninvolvedinTC-workfor morethanadecade. Theresearchquestioninvestigatedhereishowastandardizationproject,intendedtodevelop standards,technicalreportsandotherguidelinesforgeographicinformation,isperceivedasmotivating bytheprojectteammembers?

Research Method SIShadwhentheinvestigationwasconducted9technicalcommittees,TC,activeinfieldof geographicalinformation.TheTC’sweremainlydealingwithnationalSwedishstandardizationand theISO19100standardseriesforgeographicinformation.3 TheindividualTC´shavenotbeensubjectforindividualresearch,butaretreatedasoneentity. Inordertomeetthepurposeaqualitativemethodwasusedtocollectdata.Narrativeinterviewswere conductedtogettheinvolvedparticipant´sperspectiveonthestandardizationprojects.Aninterview guidewasconstructed,basedonLeontiev’s(1978)theoryontherelationshipbetweenanindividual’s goalandthemotiveofacollectiveactivity.Inthebeginningofeachinterview,theintervieweeswere askedtodescribetheproject,thegoal,thestakeholders’expectations,theintervieweesexperiences oftheprocess,andtheperformancesintheprojectteam.Thefollowingquestionsconcernedthe interviewees’viewofthemotives’behindtheprojectandtheiremployingorganization.Thereafter,the intervieweeswereaskedabouttheirpersonalmeaningfulgoalandhowitwasrelatedtotheproject’s motive.Finally,theywereaskedabouttheconditionsfortheproject’ssucceeding. Inordertounderstandhowtheprojectswereexperiencedbytheintervieweesandwhytheywere experiencedthatwaytheMeaning Constitution Analysis, MCA(Sages&Lundsten,2004)method wasused.Inafirststepoftheanalysiseachinterviewwasdividedintomeaningunits.Eachmeaning unitsconsistedofoneorafewclauses.Themeaningunitswerethencategorizedintothemes.The interviewswerethencomparedinordertofinddifferencesandsimilarities.Theinterviewswere categorizedbasedonthemotivesbehindthestandardizationprocesses.Basedonthecategorization theintervieweesweredividedintogroups.Forinstance,insomeinterviewsthemotivecouldbe relatedto“stakeholders”,whereasinotherinterviewsthemotivecouldberelatedto“theemploying organization.If“stakeholders”wasmentionedasthecentralaspectforthestandardizationprocess inonegroupofinterviewstheintervieweeswerecategorizedintoonegroupincontrasttothose intervieweesindicatingthat“theemployingorganization”wasthecentralaspect. ThecasestudywasconductedbyinterviewingindividualpresentandformerTCmembers.The intervieweeswererandomlyselectedbystudyingtheirpresenceatcommitteemeetings,documented inthemeetingminuteswhereavailable,andthroughdiscussionswiththeauthor’scolleaguesinvolved inTKstandardizationwork.23presentandformermemberswerecontacted.Intotal,18presentand formercommitteememberswereinterviewed;13membersactiveinsomeoftheTCs(sevenchairmen andsixteammembers),twoformerteammembershavinglefttheirTCsduetoreorganizations,but havebeenreplacedwithothersfromtheirrespectiveorganizations,andthreeformerteammembers whoseorganizationshavelefttheirTCs.The9TCsconsisttodayof81membersrepresenting43 differentpublicandprivateorganizations.4SeveralorganizationsarerepresentedinmorethanoneTC. TheTCchairmenwereincludedinthestudysincetheyareresponsibleformanagingthecommittee andappointedbySISafterrecommendationfromtheparticipatingorganizations(Beskow,2017), oftenemployedbyoneoftheorganizationsparticipatingintheTCandnormallymuchengagedinthe TCsdailywork.5TheTCteammembersareappointedbytheparticipatingorganizations(Beskow, 2017).Inthefollowingtext“member”indicatechairmenandteammembersunlessotherwisenoted. Allinterviewswereconductedbypersonalmeetingsorbytelephone/Skype,supportedbyopen endedquestions.TheauthorshaverefrainedfromsendingoutquestionnairestoallTCmembers, whichmayhaveincreasedthenumberofinterviewees,butwithanswersonpre-formulatedquestions. Instead,theapproachofin-depthinterviewsbasedinfeweropenendedquestionswerechosento allownarrativeinterviewsconcerningtheirindividualmotives.Theintervieweeswere,forexample, askedaboutthemotivationoftheorganizationtheyrepresentandtheirpersonalmotivesforbeing involvedinstandardization,thesupporttheyreceivefromtheirhomeorganizationandtheviewof theirhomeorganizationonstandardization.Itmustbenotedthatthisstudydoesnotincludethe formalmotivesoftheparticipatingorganizationsandlevelofsupport,butthemotivesandsupport asperceivedanddescribedbytheinterviewees.SISfacilitatetheTCworkbysupplyingaproject managerandbybeingresponsibleforformal,administrativematters.

Previous Research on Participation Theselectionofstakeholdersforparticipatinginstandardizationprojectsisessential.Therearecases wherestakeholdersfromlargerorganizationstendtoinfluencethestandardizationinawaythatmakes thestandardsmorecomplex(deVries,2006).Themotivesforparticipatinginstandardizationwork aremany,forexampleBlindandMangelsdorf(2016),BlindandGauch(2009),Mangelsdorf/2009), Blind(2006),andJacobs,Procter,andWilliams(1996;2001).However,wehavenotidentified researchontheinfluenceofstakeholdersonstandardizationofgeographicalinformation. Contributingtostandardizationdemandsmanaginginformation,implyingthatstandardization iscomplex,seee.g.Hanseth,Jacucci,Grisot,andAanestad(2006).Previousresearchhasshowna relationshipbetweenperformanceincomplextasksandmotivation(Amabile,1982),implyingthat motivationalfactorsneedtobeconsidered.Accordingtoself-determinationtheory,SDT,thereare threefundamentalpsychologicalneeds:Autonomy,Competence,andRelations(Ryan&Deci,2000). TheconceptAutonomyreferstoanindividual’sexperienceofbeingabletocontrolasituation,the conceptCompetencereferstoaprocessoflearningnewskillsorknowledge,andtheconceptRelations referstoafeelingofinvolvementinasocialcontext.Inanactivityinwhichthesethreeneedsaremet astateofautonomousmotivationarises.Aprerequisiteforthebasicpsychologicalneedstobemet inaworksituationisthattheindividualhasacertaindegreeoffreedom,theworkinvolvesacertain levelofchallengeandthatperformancesleadtoinvolvementinasocialcontext. Steinfield,etal.(2007)mentionthatconsultantsmaynotbeabletorecoveralltheirindividual costsbybillingtheirclientstheirtotalexpenses.andthattheirparticipationthereforecompeteswith fee-generatingwork.However,thisbehaviormaybevoluntarysincetheremaybeaneventuallater payoffinfuturebusinessdevelopmentsincetheymayhaveobtainedaknowledgegapinrelationto non-participatingcompetitors(Steinfield,etal.,2007,p.182).Anotherindividualreasonformany toparticipateisapersonalinterestinthesubject-mattertobestandardized.Thismayresultinthe willtoparticipatemoreorlessonone´sprivate,freetime,asoneintervieweeexpressed(Steinfield, etal.,2007,p.182).Anotherreasontoinvestprivatetimeintotheprojectwasthattheybecame committedtothecauseortotheotherparticipants(Steinfield,etal.,2007,p.182).Frequentand lastinginteractionamongexpertsworkinginagrouptendtoforgegroupstogether(Isaak,2006). However,notmuchresearchaboutmotivationingeographicalinformationstandardizationteamshas beenidentified.However,onesuchpublicationisareportfromtheSwedishStandardsInstitute(2012). organizational Motives for Standardization

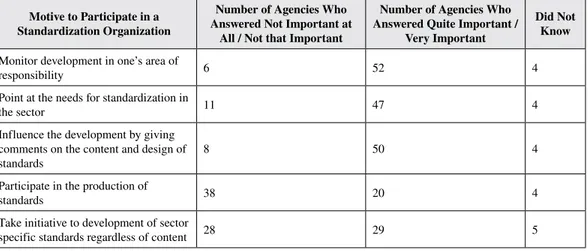

Agovernmentalstudyfrom2007describesthemotivesof626Swedishgovernmentalorganizations tobeinvolvedinformalITstandardization.Theirmotivesforparticipationwerenotprimarilythe productionofstandards,butrathertomonitorthedevelopmentofstandards,pointoutareaswhere standardizationisneededandtogiveinputandcomments(Swedishgovernment,2007,pp.354-356). Instandardizationingeneral,therecanbeseveraldifferentmotivesforparticipating,exceptthe productofthestandardizationperse(deVries,2006).SeeTable1.Thatis,therewasadivergence betweenexplicitandimplicitmotives. Anorganizationalmotiveleadstheactivitytosatisfyaspecificneed(Leontiev,1978).When theneedissatisfied,externalprocessescanbestarted(Tobach,1999).Theseprocessesmaythen beactivitiesinanexternalorganization,implyingthattheactivitiesaredependentoneachotherto function.Ingeodatastandardizationprocessesmultipledevelopersfromdifferentorganizationsare involvedtodevelopastandard,othernormative,orinformativeproduct.Eventhoughtheorganizations canhavedifferingmotives,theysharetheneedofastandard.Thestandardcanfacilitate,ormay evenbeaprerequisitefor,theorganizationstoperformtheiractivities.Anexampleistomeetthe expectationsintheaforementionedSwedishnationalstrategyforgeographicinformationinfrastructure 2016-2020(Lantmäteriet,2016).

Relationships Between organizational Motives and Personal Meaningful Goals Anorganizationalcontextaffectspeople’smotivation(Deci,Connel,&Ryan,1989;Gagné&Deci, 2005),implyingthatunderstandingmotivationrequiresunderstandingtheorganizationalstructure. Leontiev’s(1978)theoryontherelationshipbetweenanindividual’sgoalandthemotiveofacollective activitybridgesthegapbetweentheindividuallevelandtheorganizationallevel.Satisfactionofthe basicpsychologicalneedsinataskmakesthegoalofthetaskpersonallymeaningfulfortheindividual (cf.Gagné&Deci,2005).Byinvolvementinanactivitytheindividual’spersonalmeaningfulgoalis relatedtothemotiveoftheactivity.Agoalisaperson’simaginationofadesirablestateinthefuture, whereasamotiveisthekitlinkingpeopleinacollectiveactivity.Themotiveformstheframein whichtheindividualscanfulfiltheirpersonalmeaningfulgoalsand,bythat,bemotivated(Leontiev, 1978).Whenanorganizationcommunicatestheexpectationsonstandardization,theindividual relatestheseexpectationstopersonalmeaningfulgoals.Theexpectationscanbeunrelatedtopersonal meaningfulgoalsandthustheindividualwillnotbemotivated.Theexpectationscanalsoencourage theindividualtostrivefordevelopmentofpersonalcompetencealongwithstandarddevelopment.A motiveoriginatesinarealorperceivedneedamongagroupofpeople(Leontiev,1978).Ifthemotive formstheactivityinawaythatmakesitsatisfythepsychologicalneeds,autonomy,competence,and relations(cf.Ryan&Deci,2000)thepersonalmeaningfulgoalisrelatedtotheactivityitself(cf. Leontiev,1978).Inastandardizationprojectanindividual’spersonalmeaningfulgoalcanbetodevelop thepersonalcompetencebyparticipationintheprojectand,bythat,satisfypsychologicalneeds. Multipleorganizations,withdifferingmotives,areinvolvedinstandardizationprojects.Consequently, theteammembershaveseveralmotivestoconsiderinrelationtotheirpersonalmeaningfulgoal. Multipleactivitiescanshareanobject,inspiteofdifferingmotives.Forinstance,themotive foroneactivitycanbetodevelopaproduct.Themotiveforanotheractivitycanbetodistribute theproduct.Theproductistheobjectforbothactivities.Thedifferingmotivesmakepeopleinthe activitiesperceivetheobjectfromdifferentperspectives,whentheobjectissharedandpeoplefrom separateactivitiesinteract.Intheseinteractionspeoplecanlearnfromactivitiesbeyondtheirown (Engeström,2001).Previousstudiesindicatethatpersonalinteractionsenhancemotivation(Bent &Freathy,1997),whichcanbeexplainedbythepsychologicalneedforrelations(Gagné&Deci, 2005).Additionally,thepsychologicalneedforcompetence(Gagné&Deci,2005)issatisfiedby thelearningprocessininteractionsbetweenactivities.Thatis,interactionsbetweenactivitiescan affectpeople’sautonomousmotivation,implyingthatpersonalmeaningfulgoalscanbeachieved.

Table 1. Motives for governmental agencies to participate in standardization organization. Translated from Swedish government (2007, p. 356)

Motive to Participate in a Standardization Organization

Number of Agencies Who Answered Not Important at

All / Not that Important

Number of Agencies Who Answered Quite Important /

Very Important Did Not Know Monitordevelopmentinone’sareaof responsibility 6 52 4 Pointattheneedsforstandardizationin thesector 11 47 4 Influencethedevelopmentbygiving commentsonthecontentanddesignof standards 8 50 4 Participateintheproductionof standards 38 20 4 Takeinitiativetodevelopmentofsector specificstandardsregardlessofcontent 28 29 5

Interactionsbetweenstandarddevelopersandstakeholdersinstandardizationprojectscanhavea positiveeffectonmotivation(cf.Bent&Freathy,1997). Tounderstandactivities,theirnetworksneedtobestudiedalongwiththem(Spinuzzi,2011). Spinuzzi’s(2011)theorydescriberelationshipsbetweenmultipleactivities.Anobject,sharedina network,tendtobeinconstant,makingitperceiveddifferentlyindifferentactivities.Inanetwork ofactivities,whichtakesplaceinstandarddevelopment,asinglepersoncanbeinvolvedinmultiple activities(Miettinen,1998[ascitedinSpinuzzi[011,p.457]).Thereby,apersonconstitutesalink betweendifferentactivitiesandtransferunderstandingofanambiguousobject.Insomecases,the objectisunclear.Thatis,peopleinvolvedinsuchnetworkdonothaveaclearlydefinedaimtostrive for(Spinuzzi,2014).Instandardizationofgeodatatheobjectshouldberatherclear.However,there canbeimplicitmotivesforparticipationinstandardization(Swedishgovernment,2007,pp.354-356).Consequently,therecanbeseveralmotivesfortheindividualstandarddeveloperstotakeinto respect,whichaffectstheirmotivation. RESULTS

Motivation Among Members in Technical Committees

Theinterviewedchairmenexpressedthattheirmainmotiveforparticipationinthetechnical commissionswastostructuregeographicdata.Fortwochairmen,therewasanadditionalmotive, namelytointensifytheinteractionsamongtheteammembers.Theyexperiencedlackofengagement amongteammembersasahindranceinthestandardizationprocess.Therearetimeconstraintsinthe projectsconsideredasareasonforthelackofcommitmentamongparticipants.Theindividualproject teammemberscannotinfluencetheworkloadintheorganizations,buttheemployee’smotivationmay stillberelevant.Withahighdegreeofmotivationforthetask,theemployeewillbemoreinclined toprioritizethetask. Therewereconsiderabledifferencesbetweentheteammembers’descriptions.Allmembersfrom publicorganizations,exceptone,expressedthattheirorganizationhadtoprioritizethemembersdaily workingtasks,andthatthetechnicalcommissionsthuswerenotprioritized.Theyneededtofocus ontheorganization’scoreactivities. Oneoftheteammembers,whorepresentedaninterestorganizationpredominantlyforsmall sizedcompanies,expressedthattheorganizationwasdependentontheworkdoneinthetechnical committee.Manyofthecompaniesneededaccessiblegeographicdata.Inordertosatisfythisneed, theorganizationengageditselfinatechnicalcommittee.Therelationsbetweenthecompaniesand theinterestorganizationmadetherepresentativebeingmotivatedtoparticipateinthetechnical committee.Theprojectmanagerdidnotneedtofocusoninteractionsbetweenteammembers;the projectproceededdrivenbythemotivationtosolvetheneedsofcompaniesindirectlyinvolvedby theinterestorganization. Inallinterviewstheintervieweessaidthatthestandardizationprojectsdemandedaconsiderable effortfromthem.Forsomeoftheintervieweesthestandardizationprojectwasrelatedtoan unpleasantpersonalsituation.However,thestandardizationprojectshaddifferentmotivesand goalsfortheinterviewees.

organizational Motives and Personally Meaningful Goals

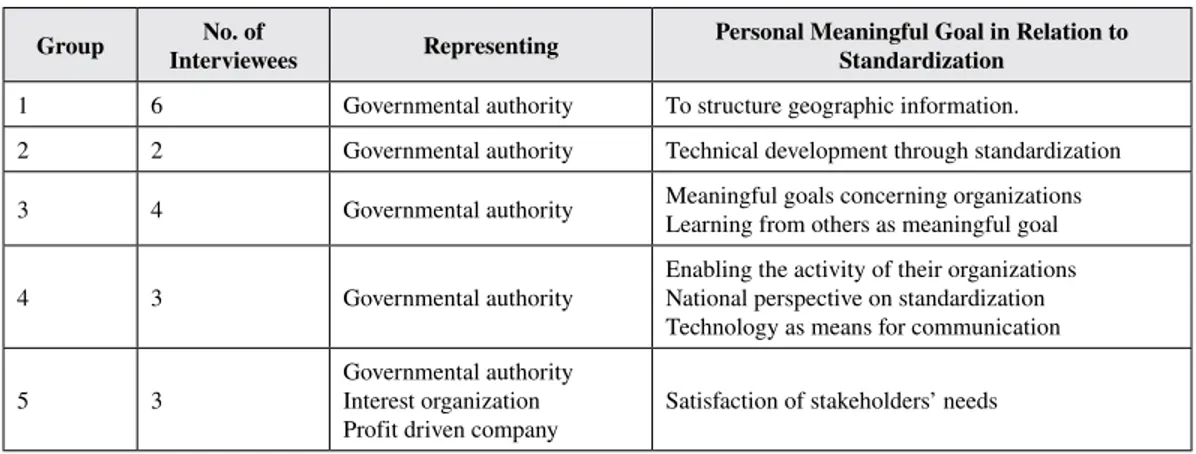

Theintervieweesdescribedfivedifferentmotivesforparticipation:1)todevelopstandardized structuresforgeographicinformation,2)totakepartintechnicaldevelopment,3)tominimize resource waste, 4) to run the organization based on national perspectives, 5) to facilitate informationtransmission.

Sixintervieweesdescribedtheobjectfortheiractivityasstructureofgeographicinformation. Geographicdataneedstobestructuredinordertoenableinformationtransferbetweenusers. There is a need for standardization in the organizations, which made them engage in the

standardizationprojects.Themainobstacle,asdescribedbytheinterviewees,wascommittee member’sengagement.Insufficientcommunicationcameasaneffectoflackingengagement. That is, in the beginning of the project the object is structure of geographic information. Duringtheprojecttheobjectchanges.Inalaterstatetheobjectisthecommunicationinthe committee.Inordertostructuredatamultipleperspectivesfromdifferentbranchesareneeded. Inturn,interactionsinprojectteamswereneededtosynthesizethemultipleperspectives.The intervieweesdescribedtwoaspectsofclarificationasapersonalmeaningfulgoal.Thefirstaspect wasclarificationoftheirownandcommitteemembers’rolesinthestandardizationprojects. Theirrolesandtheexpectationsoneachcommitteememberwereunclear,whichhinderedthe projectsfromproceedingeffectively.Thesecondaspectwasclarificationoftheexplicitpurpose ofthestandardizationprojects. Thesecondgroup,oftwointerviewees,describedtheirobjectastechnicaldevelopment.In contrasttothepreviouslymentionedinterviewees,forthemtheobjectivewasnotsocialinteractions, butplansfordevelopmentofthetechnicalaspectsofstandardization.Theintervieweesdescribed makingcontributionstothecommunitybenefitasapersonalmeaningfulgoal. Thethirdgroup,offourinterviewees,describedtheobjectasminimizedresourcewaste.The standardizationprojectswerenotprioritizedbytheirorganizations.Therefore,theamountoftimespent onstandardizationneededtobeminimized.Still,theseintervieweeswereinvolvedinstandardization projectsandtheyhadavalueforthem,namelyinsightintootherorganizations.Theylearnedfrom othersinthestandardizationprojects,regardlessofthelackoffocusonstandardizationperse.The objectsdescribedbytheintervieweesdifferedandwerenotassociatedwithstandardization.Likewise, thepersonalmeaningfulgoalsdiffered.Fortwointerviewees,thepersonalmeaningfulgoalconcerned theirorganization.Theothertwointervieweesdescribedlearningfromothercommitteemembersas theirpersonalmeaningfulgoal. Afourthgroup,ofthreeinterviewees,describedtheobjectasenablingtheactivityoftheir organizations.Theyemphasizedtheorganization’snationalperspectiveonstandardization.The mainobjectivewasestablishmentofguidelinesforstandardizationofnationalgeographicdata.Two intervieweestalkedabouttechnologyasameanforcommunication.Oneoftheintervieweestalked aboutthefinalstandardsasthemeanforcommunication.Thatis,theintervieweesemphasizeddifferent aspectsofcommunication;technologypersevsthefinalstandards.Facilitatingthetransmissionof informationwasdescribedasapersonalmeaningfulgoal,implyingthatthepersonalmeaningfulgoal correspondedtothemotiveoftheactivity. Thefifthgroupofintervieweesdifferedfromtheformerfourgroups.Inthefifthgroup, oneintervieweerepresentedagovernmentalauthority,oneoftheintervieweesrepresentedan interestorganization,andoneintervieweerepresentedaprofitdrivencompany.Amongthese organizations,anetworkwithfrequentinteractionswithstakeholderswasacommonfeature. The interviewees in group 1, 2, 3, and 4 represented a governmental authority. Possibly, representing a non-governmental organization makes commission members more prone to perceivestakeholders’needsandsatisfactionasapersonalmeaningfulgoal.Thisishowever subjectforfurtherresearch. Theinteractionofprivateandpublicactorsareoftenblendedtocombinetheiradvantages,such asprovidingtechnicalexpertisefromtheprivatesectorandmobilizationofstatepower(Abbott& Snidal,2001,p.363).7 Theinterestorganization’sstakeholdersweremainlysmallfirms.Theycommunicatedtheir needsoffacilitationoftransmissionofgeographicdata.Theinterestorganizationmonitoredthese interests.Inturn,thegovernmentalauthoritywasinfrequentcontactwiththeinterestorganization andadditionallywithsimilarinterestorganizations.Theprofitdrivencompanywasinfrequent contactwithcustomerscommunicatingstandardizedsolutionsfore-services.Theintervieweesin thefifthgrouphadfrequentinteractionswithclients.Intheseinteractions,theclientsexpressed

theirneeds.Thatis,theintervieweesconsideredthestandardizationprojectsbeingrelatedto people’sneeds(seeTable2).

ANALySIS ANd dISCUSSIoN

Thestudyshowedthatamajormotivefororganizationsandindividualstoparticipateinformal standardizationistocontributetothedevelopmentofstandardsforthedescriptionandexchangeof geographicinformation.However,thereweredifferencesdependingontherelationshipsbetween theintervieweesandthestakeholders.Intervieweeswithfrequentinteractionswithstakeholders perceivedthestandardizationprojectbeingapersonalmeaningfulgoal.Thisfindingcorrespondsto theresearchresultspresentedbyBentandFreathy(1997),implyingthatpersonalinteractionswith clientsfacilitatemotivation. Noneoftheintervieweesmentionedtheirparticipationinstandardizationworkasanindividual strategicpersonalcareerplanningaimingat,forexample,ahigher/betterpositionintheorganization orhighersalary.Thatis,themotivatorwasnotmainlyrelatedtoanextrinsicreward.Theinterviewees wereintrinsicallymotivated,implyingthattheirbasicpsychologicalneedsofautonomy,competence, andrelations,weremet(cf.Gagné&Deci,2005).Onthecontrary,for15intervieweesinthefirstfour groupsdescribedearlier,participationinstandardizationwasrelatedtoanincreasedworkload,knowing thatonecannotmakeapropercontributionduetootherprioritiesintheparticipant’sorganization.They werenotabletomeettheexpectationssetontheminthestandardizationprojects.Forsomeofthese intervieweesapersonalgoalwastolearnfromothercommissionmembers.Thisimpliestherewere contradictionsbetweenmotivesandthepersonalmeaningfulgoals.Insuchsituation,theindividual riskstofeelalienated,resultinginamotivation,namelyanabsenceofmotivation(Gagné&Deci,2005). Fortheintervieweesinthefifthgroup,therelationstotheorganization’sstakeholders,standardization wasperceivedasameantofacilitatethestakeholders’activities.Forthemstandardizationwasboth theobjectandapersonalmeaningfulgoal,whichincreasesintrinsicmotivation. Thisobservationseemstocontradicttheviewsexpressedine.g.theSwedishnationalgeodata strategythatstandardsareanimportantpartofthegeographicinformationinfrastructureandthe effortoffinancingaccessforuserstostandards.Thereisagenerallywishamongthestakeholders thatitisimportantthatstandardsarebeingused. ParticipationintheformalstandardizationprocessisvoluntaryandinlinewiththeSwedish principlesofgovernmentalautonomy.Lantmäterietwasin2006appointedasresponsiblefor facilitatingincreasedcooperationconcerninggeographicinformationamongstakeholdersinSweden bytheSwedishgovernment(Swedishgovernment,2006;2009).Thisappointmentdoeshowever

Table 2. Representing in relation to personal meaningful goals

Group IntervieweesNo. of Representing Personal Meaningful Goal in Relation to Standardization

1 6 Governmentalauthority Tostructuregeographicinformation.

2 2 Governmentalauthority Technicaldevelopmentthroughstandardization 3 4 Governmentalauthority MeaningfulgoalsconcerningorganizationsLearningfromothersasmeaningfulgoal 4 3 Governmentalauthority EnablingtheactivityoftheirorganizationsNationalperspectiveonstandardization

Technologyasmeansforcommunication 5 3 GovernmentalauthorityInterestorganization

notincludeanymandatetoinstructotheramongpublicagenciesorotherpartiestoparticipate. TheSwedishsystemofpublicagenciesisbasedonacenturiesoldprincipleofratherindependent agencies, where tasks are meant to be solved in cooperation, not by one agency mandating anotheragencytodospecifictasks.Swedishgovernmentalagenciesthereforeholdaconsiderable highlevelofautonomyandareindependentlymanagedunderperformancemanagementbythe government(Hall,Nilsson&Löfgren,2011).8Thisautonomyisconstitutionallyenshrined.The responsibilitiesofeachgovernmentalagencyarespecifiedintheirgovernmentalinstructions, forexampleLantmäteriet´sinstructions(Swedishgovernment,2009).Thisautonomymeansthat agenciescanmaketheirowndecisionsconcerningif,andhow,theywanttobeparticipatein nationalandinternationalstandardization(Swedishgovernment,2007,p.123),unlesstheyreceive specific,governmentalinstructions. Thisprincipleisintheseauthors´opiniontobeseenasanorganizationalchallenge,duetothe riskthatparticipationinstandardizationmaynotbeprioritizedbytheorganizationitselfbyallowing theiremployeessufficienttimetoworkwiththeseissues(cf.Riillo,2013). Oneofthefindingsofthisstudyisthatthereasonwhytheinvestedresourcesinstandardization bysomeorganizationsareinsufficientistheresultofthatstandardizationseemnotprioritizedin relationtotheirmainactivities(cf.Riillo,2013).Theyhaveneverthelessinvestedresourcestoa specific,albeitnotsufficient,extent.Theyareofficiallyinvolvedbytheinvestedresources.Previous studiesshowthatnetworkingtendtoleadorganizationstoaimingattheirself-representationperse (Spinuzzi,2014).Insomecontexts,anorganizationcanimproveitsself-representationbyinvestments ofresourcesinastandardizationproject. CoNCLUSIoN Thisstudyfocusedoninvestigatingindividualmotivesforparticipationinformalstandardizationof geographicinformation,andaselectionofchairmenandmembersofTechnicalCommitteesatthe SwedishStandardsInstitutewereinterviewed. Themajorityofintervieweesexpressedastrongpersonalmotivationinstandardizationof geographicdata.Aminorityexpressedalackofmotivationforparticipatinginstandardization projects.Theintervieweesmotivationcorrespondedtotheinterestoftheirorganization.Itisnot sufficienttosupportthefinancialobligationsofbeingpartofatechnicalcommitteebypaying participationfees,etc.Iftheindividualparticipants´timeisnotallocatedforthespecificpurpose toparticipateinthetechnicalcommitteeitmayleadtolackofmotivationduetothefeelingof notbeingabletoparticipateinanoptimalwayandthattheworkisregardedaslessimportant thanotherworkactivitiesclosertodailylifeactivities.Thisviewhasalsobeenexpressedby someoftheinterviewees. Intervieweesrepresentingorganizationswithfrequentcontactswithstakeholdersdescribedthe standardizationaspersonallymeaningfulforthemselves.Accordingtotheanalysestheinteractions withstakeholdersmadethepurposeofstandardizationclear.Thestakeholders’needswererelated tothestandardizationprojects. Theirdailyworkintheirrespectiveorganizationshasoftenhigherpriorityinrelationto standardization work. This is in contrast with the organizational motive of the participating organizationsandmayslowdownthedevelopmentofstandardsandotherpublicationsduetolack ofresources. Further Research Alargerstudyencompassingthemajorityoforganizationsintheinvestigatedtechnicalcommitteesis beingplannedaseitherastand-alonestudyofmoreparticipantsfromthetechnicalcommittees,oras partofacomparativestudyofoneormoretechnicalcommitteeswithintheinformationsector.Future

researchshouldevenfocusonorganizationalaspectsofparticipation.Forexample,howorganizations prioritizeandimplementstandardsongeographicinformationandwhetheritispossibletomeasure thesocietalandeconomicimpactofdegreesofmotivation. ACKNowLEdGMENT Theauthorsareindebtedtothemembersofthetechnicalcommitteesparticipatinginthisstudyand theanonymousreviewersforvaluableinputandcomments.

REFERENCES

Abbott,K.W.,&Snidal,D.(2001).International“standards”andinternationalgovernance.Journal of European Public Policy,8(3),345–370.doi:10.1080/13501760110056013

Amabile,T.M.(1982).Socialpsychologyofcreativity:Aconsensualassessmenttechnique.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,43(5),997–1013.doi:10.1037/0022-3514.43.5.997

Bent,R.,&Freathy,P.(1997).Motivatingtheemployeeintheindependentretailsector.Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services,4(3),201–208.doi:10.1016/S0969-6989(96)00045-8

Beskow,C.(2017).Regler för arbete i teknisk kommitté (SIS/TK)[RulesforworkinginaTechnicalCommittee (SIS/TK)].Stockholm,Sweden:SwedishStandardsInstitute.

Blind,K.(2006).Explanatoryfactorsforparticipationinformalstandardisationprocesses:Empiricalevidence atfirmlevel.Economics of Innovation and New Technology,15(2),157–170.doi:10.1080/10438590500143970 Blind,K.,&Gauch,S.(2009).Researchandstandardisationinnanotechnology:EvidencefromGermany.The Journal of Technology Transfer,34(3),320–342.doi:10.1007/s10961-008-9089-8

Blind,K.,&Mangelsdorf,A.(2016).Motivestostandardize:EmpiricalevidencefromGermany.Technovation, 48–49,13–24.doi:10.1016/j.technovation.2016.01.001

deVries,H.J.(2006).Standardsforbusiness-Howcompaniesbenefitfromparticipationininternational standardssetting.InA.L.Bement,T.Standage,T.Sugano,&K.Wucherer(Eds.),International Standardization as a strategic tool - Commended papers from the IEC Centenary Challenge 2006 (pp.130–141).Geneva, Switzerland:IEC.

Deci,E.L.,Connel,J.P.,&Ryan,R.M.(1989).Self-determinationinaworkorganization.The Journal of Applied Psychology,74(4),580–590.doi:10.1037/0021-9010.74.4.580

Engeström,Y.(2001).Expansivelearningatwork:Towardanactivitytheoreticalreconceptualization.Journal of Education and Work,14(1),133–156.doi:10.1080/13639080020028747

EuropeanUnion.(2007).Directive 2007/2/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 March 2007 establishing an Infrastructure for Spatial Information in the European Community (INSPIRE).Brussels, Belgium:EuropeanUnion.

Gagné,M.,&Deci,E.L.(2005).Selfdeterminationtheoryandworkmotivation.Journal of Organizational Behavior,26(4),331–362.doi:10.1002/job.322

Hall,P.,Nilsson,T.,&Löfgren,K.(2011).Bureaucraticautonomyrevisited:Informalaspectsofagencyautonomy inSweden.Paper presented at the Permanent Study Group VI on Governance of Public Sector organizations, Annual Conference of EGPA,Bucharest,Romania.

Hanseth,O.,Jacucci,E.,Grisot,M.,&Aanestad,M.(2006).Reflexivestandardization:Sideeffectsand complexityinstandardmaking.Management Information Systems Quarterly,30,563–581.

InternationalOrganizationforStandardization.(2014).ISO 19115-1:2014 Geographic information - Metadata - Part 1 - Fundamentals.Geneva,Switzerland:InternationalOrganizationforStandardization,ISO.

Isaak,J.(2006).TheroleofindividualsandsocialcapitalinPOSIXstandardization.International Journal of IT Standards and Standardization Research,4(1),1–23.doi:10.4018/jitsr.2006010101

Jakobs,K.,Procter,R.,&Williams,R.(1996).Usersandstandardization-Worldsapart?TheExampleof electronicmail.StandardView,4(4),183–191.doi:10.1145/243492.243495

Jakobs,K.,Procter,R.,&Williams,R.(2001).Themakingofstandards:Lookinginsidetheworkgroups.IEEE Communications Magazine,2001(April),2–7.

Lantmäteriet.(2016).The national geodata strategy 2016-2020.Reportno.2016/7.Gävle,Sweden:Lantmäteriet. Leontiev,A.N.(1978).Activity, consciousness, and personality.EnglewoodCliffs,NJ:Prentice-Hall.

Mangelsdorf,A.(2009).Driving factors of service companies to participate in formal standardization processes: An empirical analysis.doi:10.2139/ssrn.1469512

Miettinen,R.(1998).ObjectConstructionandNetworksinResearchWork:TheCaseofResearchonCellulose-degradingEnzymes.Social Studies of Science,28(3),423–463.doi:10.1177/030631298028003003

Niklasson,B.,&Pierre,J.(2012).Doesagencyagematterinadministrativereform?:Policyautonomy and public management in Swedish agencies. Policy and Society, 31(3), 195–210. doi:10.1016/j. polsoc.2012.07.002

Riillo,C.(2013).ProfilesandmotivationsofStandardizationPlayers.International Journal of IT Standards and Standardization Research,11(2),17–33.doi:10.4018/jitsr.2013070102

Ryan,R.M.,&Deci,E.L.(2000).Intrinsicandextrinsicmotivations:Classicdefinitionsandnewdirections. Contemporary Educational Psychology,25(1),54–67.doi:10.1006/ceps.1999.1020PMID:10620381

Sages,R.,&Lundsten,J.(2004).Theambiguousnatureofpsychologyasscienceanditsbearingonmethods ofinquiry.InM.Lahlou,&R.B.Sages(Eds.),MèthodesetTerrainsdelaPsychologieInterculturelle(pp.189-220).Lyon,France:L’Interdisciplinaire,Limonest.

Spinuzzi,C.(2011).Losingbyexpanding:Corallingtherunawayobject.Journal of Business and Technical Communication,25(4),449–486.doi:10.1177/1050651911411040

Spinuzzi,C.(2014).Hownoemployerfirmsstage-managead-hoccollaboration:Anactivitytheoryanalysis. Technical Communication Quarterly,23(2),88–114.doi:10.1080/10572252.2013.797334

Steinfield,C.,Wigand,R.,Markus,M.L.,&Minton,G.(2007).Promotinge-businessthroughvertical informationsystemsstandards:LessonsfromtheUShomemortgageindustry.InS.Greenstein&V. Stango (Eds.), Standards and Public Policy (pp. 160–207). Cambridge, Great Britain: Cambridge UniversityPress.

Swedishgovernment.(2006).Förordning(2006:1009)omändringiförordningen(1995:1418)medinstruktion fördetstatligalantmäteriet[Ordinance(2006:1009)concerningchangesinordinance(1996:1418)forthe governmentalLantmäteriet].Svenskförfattningssamling2006:1009.Stockholm,Sweden:Ministryofthe Environment.

Swedishgovernment.(2007).Den osynliga infrastrukturen - om förbättrad samordning av offentlig IT-standardisering. SOU 2007:47[Theinvisibleinfrastructure-concerningimprovedcoordinationofpublicIT-standardization.SOU2007:47].Stockholm,Sweden:MinistryofEnterpriseandInnovation.

Swedishgovernment.(2009).Förordning(2009:946)medinstruktionförLantmäteriet[Ordinancewith instructionsforLantmäteriet].Svenskförfattningssamling2009:946.Withlateramendments.Stockholm, Sweden:MinistryofEnterpriseandInnovation.

SwedishStandardsInstitute.(2009).SS 637004:2009. Geografisk information - Väg- och järnvägsnät - Applikationsschema[Geographicinformation-Roadandrailwaynetworks-Applicationschema].Stockholm, Sweden:SwedishStandardsInstitute.

SwedishStandardsInstitute.(2012).RapportomförslagtillutvecklingavStanlismetodik.[Reportonsuggestions fordevelopmentoftheSTANLImethology].2012-05-25.Stockholm,Sweden:SwedishStandardsInstitute, technicalcommitteeTK323.

SwedishStandardsInstitute.(2016).SS 637040:2016. Geografisk information - Detaljplan - Applikationsschema för planbestämmelser[Geographicinformation-Detailplan-Applicationschemaforplanninginstructions]. Stockholm,Sweden:SwedishStandardsInstitute.

SwedishStandardsInstitute,&Lantmäteriet(2017).Avtal nr LMV8589[Agreementno.LMV8589].Stockholm, Sweden:SwedishStandardsInstituteandGävle,Sweden:Lantmäteriet.

Tobach,E.(1999).Activitytheoryandtheconceptofintegrativelevels.InY.Engeström,R.Miettinen,&R.-L. Punamäki(Eds.),Perspectives on activity theory(pp.133–146).NewYork,NY:CambridgeUniversityPress. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511812774.011

ENdNoTES 1 ExamplesareLantmäteriet[theSwedishmapping,cadastralandlandregistrationauthority],Trafikverket [theNationalTransportAdministration]andothershavebeeninvolvedinformalstandardizationsincethe late1980-ies,beingpartofanationalinitiativeconcerningastandardizationprogrammeforgeographic informationattheSwedishStandardsInstitute.SeeSwedishgovernment(2007)foradditionalinformation onSwedishstandardization. 2 Seehttps://www.lantmateriet.se/en/About-Lantmateriet/Samverkan-med-andra/Geodatasamverkan/for additionalinformation. 3 Thetechnicalcommitteesare:TK320(Roadandrailroadinformation),TK323(FrameworkforGeographic Information),TK452(Watersystems),TK466(Addresses),TK533(Buildinginformation),TK538 (Forestryinformation),TK489(Metadataforgeographicinformation),TK501(Physicalplanning), TK570(Webbcartography).Note:TK489wasdissolvedduringthisresearchduetoareorganization attheSwedishStandardsInstituteandtransformedintoaworkinggroupunderTK323,buthasinthis investigationbeentreatedasaseparatecommittee. 4 Differentbranches/divisionsofanorganizationarecountedasbelongingtothesameorganization. 5 Oneauthor´sownexperienceafterbeingTCchairmanfor11years.Thisalsocorrespondswiththe opinionsoftheinterviewedTCchairmen. 6 Thesurveywassendto120governmentalagencies,ofwhich52%responded.SeeSwedishgovernment (2007,p.354)foradditionalinformation. 7 Abbott&Snidal(2001)focusedintheirstudyoninternationalstandardsandinternationalgovernance. We,however,seenoreasonwhytheirconclusionsarenotvalidfordomesticstandardization. 8 AsurveyhasshownthatthelevelofautonomydiffersamongSwedishagencies,seeNiklassonand Pierre(2012).

Jonas Lundsten is associate professor / senior lecturer at the Department of Urban Studies at Malmö University, Sweden, and has a Ph.D. in work and organizational psychology from Lund University, Sweden.

Jesper M. Paasch is senior lecturer at the Department of Industrial Development, IT and Land Management at University of Gävle, Sweden, and research coordinator at Lantmäteriet, the Swedish mapping cadastral and land registration authority. He holds a MSc degree in Surveying, planning and land management, and a Master of Technology Management degree in Geoinformatics, both from Aalborg University, Denmark, and a PhD degree in Real Estate Planning from KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden.