Marginalised belonging:

Unaccompanied, undocumented Hazara youth navigating

political and emotional belonging in Sweden

Suzanne Snowden

International Migration and Ethnic Relations Master Thesis

15 credits Spring 2018

Supervisor: Anne Sofie Roald Word count: 17070

Abstract

This paper investigates the current situation of the youth that applied for asylum in Sweden in 2015 as Unaccompanied Asylum Seeking Children (UASC). Specifically the former UASC youth from the Hazara ethnic group who were denied asylum yet are still living as undocumented in the municipality of Malmö, Sweden in 2018, now aged between 18 to 21 years old. This case study employs a hermeneutic-constructivist approach utilising semi-structured interviews with 10 of these Hazara unaccompanied, undocumented asylum seeking (UUAS) youth to examine their experiences and perspectives in terms of political and emotional belonging to communities and places in which they experience some form of marginalisation. Theories surrounding the concepts of belonging which consists of both emotional and political elements will be used, along with ‘othering’, to frame the youth’s experiences. The results of this study demonstrate how political belonging affects emotional belonging in various ways depending on context. The study also highlights how the impact of elements within both forms of belonging are assessed by individuals, and how these considerations are instrumental to a migrants decision to remain in, or leave, a location. This study also calls for further research in this field on these concepts of belonging affect marginalised groups.

Table of Contents

Abstract 2 Table of Contents 3 Acknowledgments 4 Abbreviations 5 1 Introduction 61.2 Research aim and question 7

1.3 Relevance and context of this research 7

1.4 Terminology explained 8

1.5 Scope and delimitations 9

1.6 Disposition 10

2 Contextual background 11

2.1 Why focus on the Hazara ethnic group in Sweden 11 2.1.1 Why have so many Hazara UASC from 2015 become UUAS youth? 13 2.2 Discretionary allowances for UUAS youth in Malmö 15 2.2.1 Youth Centre project for UUAS youth in Malmö 16

3 Previous studies 17

3.1 A conceptual shift in the notion of belonging 17

3.2 Belonging as a mindset 19

4 Theoretical Framework 21

4.1 The concept of belonging 21

4.1.1 Political belonging 21

4.1.2 Emotional belonging 23

5 Research design 25

5.1 Research Philosophy 25

5.2 Qualitative case study approach 25

5.3 Semi-structured interviews 26

5.4 Participant Observations 28

5.5 Sampling and criteria 28

5.6 Gathering Data 29

5.7 Access to the research field 29

5.8 Role of the researcher 30

5.9 Analyzing the data 30

5.10 Ethical considerations 31

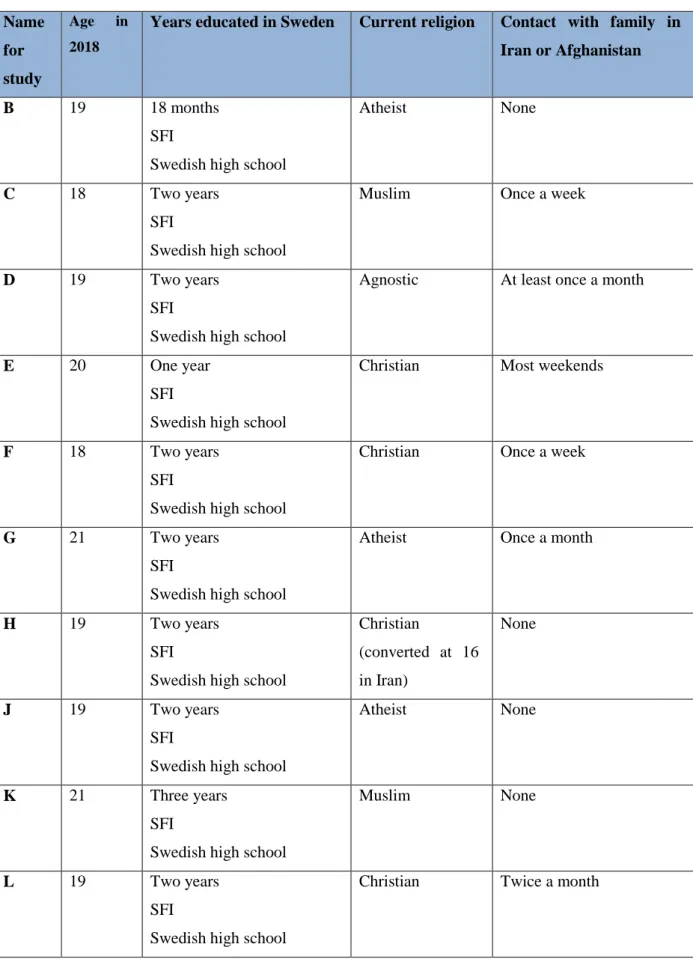

5.12 Introducing the interviewees - background information 33

6 Analysis and discussion of results of interviews 36

6.1 Keeping in touch with family 36

6.2 Impacts of institutional exclusions in Sweden 38

6.2.1 Impacts on health 40

6.3 Benefits of institutional inclusions 42

6.4 Reliance on others 43

6.5 Personal safety and othering 45

6.6 Freedom of religion in Sweden 48

6.7 Imagining the future 49

7 Conclusion 51

8 Further Research 53

Bibliography 54

Appendix 59

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank everyone I have met at Malmö University who has inspired me, nurtured, supported and challenged me to become a better academic throughout both my IMER Bachelor and Masters programmes. (Too many people to list, but you know who you are!). I feel so fortunate to have gained such a wealth of information about the world of IMER related concepts and issues that have made me realise that my “good general knowledge” was whilst good, was actually only a superficial worldview. I feel richer as a person from taking the time to study these issues in more depth, tackling two more degrees in my mid-forties.

For this thesis in particular, I would like to thank my supervisor, Professor Anne-Sofie Roald for constructive academic criticism and guidance, good chats and a warm smile throughout this journey. I am also grateful to everyone else who helped me make this thesis something I am proud of. Obviously I am forever thankful to Zoran and so many others who have always been so supportive, listening to my ideas, helping at the centre, translating, proof reading and being there for me in so many ways I cannot describe.

Most importantly, THANK YOU to the amazing Hazara youth who agreed to participate in my research and shared their personal experiences. Without you this thesis would never have been possible and you all will always have a place of belonging in my heart.

Abbreviations

ECRE European Council on Refugees and Exiles EASO European Asylum Support Office

IMER International Migration and Ethnic Relations IOM International Organisation for Migration NGO Non-governmental organisation

NGO Non-Governmental organisation NHW National Board of Health and Welfare

PICUM Platform for International Cooperation on Undocumented Migrants SMA Swedish Migration Agency

SMB Swedish Migration Board MC Swedish Migration Court

MCA Swedish Migration Court of Appeal

UASC unaccompanied asylum seeking children (child) UN United Nations

UNCRC United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child UNHCR United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees UUAS unaccompanied undocumented asylum seeking

1 Introduction

The atmosphere at the Monday night drop-in session at the youth centre in Malmö, Sweden, is always electric, buzzing with cheerful exchanges in Swedish between staff and the dozens of youths who attend weekly to socialize and share a meal that they have cooked together. There is a tangible feeling of a self-created urban family, with activities before and after the meal, similar to any night in a home filled with youths. School homework and practicing conversational English is done in quieter areas; whereas in the larger spaces, small groups are laughing over card games or a friendly billiards match. The occasional bursts of cheers or groans from those playing the FIFA football game can be heard from the TV room.

I volunteer weekly at this Monday night drop-in because of the positive dynamic in this centre and the interactions that instill a palpable sense of belonging for the people there. The familiar faces each week provide an observable sense of community with this group of youths. One night, the absence of a regular attendee creates a perceptible mood change – the reason he is missing is discussed in hushed huddles. The concern is understandable. Despite being relative strangers, these youth are tied together by their shared, yet individual histories that have led to their current status as unaccompanied undocumented asylum seeking (UUAS) youth in Malmö.

All these youths are males who had travelled to Sweden as unaccompanied asylum seeking children (UASC) over the past five years, with the majority arriving during 2015. According to the director of the centre, roughly 95% of these youth are of the Hazara ethnic group from Afghanistan. Due to a history of religious or ethnic discrimination in Afghanistan, most of these Hazara youth have been raised in Iran as a marginalized minority. Despite this, they have all recently been rejected by the Swedish Migration Court of Appeal (MCA) with the threat of being sent back to Afghanistan, a country in which most have only lived for a short time or not at all. Despite this rejection by Swedish immigration, the youths openly stated they were planning to stay in Malmö as they felt they had a place they belonged, despite being undocumented and at risk of deportation.

This paradox of the UUAS youth desiring to remain in Sweden despite exclusionary, institutional barriers, inspired this study. I wanted to explore their situation within the framework of the concept of belonging, using two interrelated forms of belonging - emotional and political. Emotional belonging involves the sense of belonging to a certain group, place, or social location, and this was demonstrated by the youth in the centre who all speak Swedish,

go to school in Malmö and have a social network here. Political belonging is looking at how governments, institutions, community groups and individuals can marginalise people by drawing social demarcations and establish border regimes. Aspects of political belonging could be observed in many situations described by the Hazara UUAS youth during discussions at the centre, whether it be their undocumented status or the societal stigma that being both undocumented, and Hazara, places on them. Due to my observations that the emotional and physical elements were impacting the UUAS youth lives in conflicting ways, I wanted to investigate where they felt they belonged and were accepted by a community especially given the stigma attached to the Hazara UUAS youth in particular - the specific reasons for their unique history of marginalisation is outlined further in this study.

1.2 Research aim and question

The aim of this study is to investigate how a specific group of UUAS youths living in Malmö navigate belonging to a community where there are exclusionary barriers to overcome. Therefore the research question for this study is:

- How do the politics of belonging affect the emotional belonging to a community for UUAS Hazara youth in Malmö?

1.3 Relevance and context of this research

This study is relevant to the field of International Migration and Ethnic Relations (IMER) as migration issues are becoming more complex, especially those surrounding membership of communities or nation states. The academic discussions exploring the concepts of belonging are also integral to understand as they are moving from simply collective ethnic and cultural boundaries to a more intersectional view that incorporates different types of belonging such as to a geographic place, over time, and through daily activities of people.1

This research focuses on the Hazara UUAS youth in Malmö to highlight the situation of the rising number of marginalised people attempting to navigate a sense of belonging to a place they do not have formal membership of.

1.4 Terminology explained

It is important at this stage to define what is meant by “youth” and “undocumented” within the context of this study and why these clarifications are important.

Youth – refers to the age cohort of 18 to 21 which is the age range of interviewees in this study. This clarification is important for two reasons. Firstly, it is not in line with the United Nations (UN) description of youth which is “in the age cohort of 15 to 24”.2 Secondly, there is

an overlap of definitions by the UN as the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) defines a child as “anyone up until the age of 18”.3

This is relevant when discussing asylum seeking youth, as Swedish law incorporates the UNCRC in regards to allowances for children. Once a UASC turns 18, the UNCRC is not applicable and the state is no longer formally bound to provide asylum seekers with these allowances.

Undocumented - The definition for this concept is taken from the Platform for International Cooperation on Undocumented Migrants (PICUM). “Persons who reside in a country without having a residence permit that allows them to do so after gaining admission by irregular routes, and having had been led to that point after a long-drawn out process involving a substantial commitment in time and scarce financial resources, but who had not at the onset of their journey necessarily intended ‘illegal’ migration”.4

I would like to highlight that the term “irregular migrant” is at times used in similar research. However, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) describes irregular migration as a much broader migrant experience as simply “entering, staying or working in a country without the necessary authorization or documents required under immigration regulations”.5

2 “Youth - Definition | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization,” accessed May 12,

2018, http://www.unesco.org/new/en/social-and-human-sciences/themes/youth/youth-definition/.

3 United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, “United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child

(CRC),” UNHCR, accessed April 2, 2018, http://www.unhcr.org/protection/children/50f941fe9/united-nations-convention-rights-child-crc.html.

4 PICUM - Platform for Undocumented Migrants with HIV/AIDS in Europe (2010).

http://www.undocumentary.org/assets/health/publications/Policy%20Papers/HCPubl%20-%20Undocumented_ Migrants_with_HIV_AIDS_in_Europe_EN%20only.pdf Last accessed May 12, 2018

5 “Key Migration Terms,” International Organization for Migration, January 14, 2015,

Therefore, in light of these definitions, “undocumented” is preferred for this study as it more adequately reflects the specific situation of the unsuccessful asylum seeking youth in this research.

1.5 Scope and delimitations

The delimitations of this study are designed to create a greater understanding of the experiences of a specific group of undocumented youth within a bounded location. Therefore this qualitative, exploratory case study was conducted in a youth centre in Malmö, Sweden during their weekly Monday night drop-in from August 2017 to May 2018. The main purpose of the study was to identify the multiple narratives of the experience of belonging for the UUAS youth, to identify how they experience inclusion and exclusion in a community on both an institutional and personal level. Empirical data was collected from semi-structured interviews of 10 Hazara youth who have volunteered to take part as interviewees. Also, data was used from participant observations of other Hazara youth attending the Monday drop-in on Monday nights – these are described as informants. I had a narrow criteria for selection of interviewees, to ensure all interviewees had common traits representative of the dominant group of UUAS youth in Malmö in 2018. The criteria I set for this study was that all interviewees were to be: male; a citizen of Afghanistan; from the Hazara ethnic group; who have lived in Iran for the majority of their life; arrived in Sweden in 2015; all asylum appeals rejected; currently living in Malmö undocumented and waiting for the 4 years to pass for asylum re-application. All 10 interviewees spoke fluent Swedish with at least basic conversational English which was important to me as a native English speaker so I could have some conversations directly with them. Two interviewees were fluent in English. When asked about transnational behaviour, none of the interviewees reported sending or receiving money from Iran or Afghanistan, which has meant economic transnationalism is not within scope of this study. All interviewees expressed that they want to stay in Sweden, even undocumented. The interviewees’ political interest in regards to Iran or Afghanistan appears to be mainly connected to obtaining information about changes that could assist with their asylum claim so they can remain in Sweden. Due to these delimitations, the experiences of any other undocumented person, or any other activity conducted in the youth centre, will not be discussed in this study.

1.6 Disposition

The first chapter of this thesis introduces the subject area, research problem, aim and questions. In addition to this, the context of the research, definitions of terminology and delimitations are outlined. Chapter two provides a contextual background with an explanation including why Hazaras are the focus of this study, including the background that led to their UUAS status. Chapter three gives an insight into existing literature with chapter four outlining the theoretical framework for this study. Chapter five describes the methodology and research design including the research philosophy, methods and considerations used at all stages of data collection and analysis. Chapter six discusses the findings and analysis of interviews in the context of the theoretical framework. Chapter seven provides the conclusion and chapter eight has suggestions for future research.

2 Contextual background

To understand why the Hazara have become UUAS youth, it is important to

appreciate a combination of factors that challenge their political and emotional belonging to different communities. This section provides a brief background of Hazara asylum seekers, along with an outline of the institutional scenarios in Sweden from asylum application to support for undocumented people.

2.1 Why focus on the Hazara ethnic group in Sweden

Statistics from the Swedish Migration Agency6 (SMA) indicate that 66 percent of all

UASC asylum applications during 2015 were made by citizens of Afghanistan. This equates to 23,480 Afghani UASC, with statistics indicating 92 percent of these applicants were male, hence the disproportionate number of male migrants being the subject of studies such as this. Furthermore, according to a UNHCR study7 on Afghan UASC asylum applicants in 2015 in

Sweden, 74 percent identified themselves as being from the Hazara ethnic group.

Many factors contribute to why people migrate to places like Sweden; however, for members of the Hazara ethnic group the reasons are quite complex. Whilst there are many current issues within Afghanistan itself with the legacy of war or current conflicts resulting in a multitude of social and human rights issues, 8 there are other explanation for so many UUAS youth in Sweden. These include widespread discrimination of Hazaras in Afghanistan and Iran for two main reasons: religion and ethnicity.

Religious discrimination of Hazaras occurs in Afghanistan due to the different Islamic beliefs of the Sunni and Shi’ite Muslims. In Afghanistan, Sunni Muslims make up the majority of the population. This differs from the Hazara minority who are Shi’ite Muslims. To put the Shi’ite minority into context, whilst the majority of Hazara are Shi’ite Muslims, Hazaras comprise only around 10 percent of the Afghani population.9 It is only the Hazara Shi’ite

Muslims who migrate to countries such as Iran, which an Islamic Republic with a majority Shi’ite population. Therefore, whilst religious discrimination of Hazaras is not problematic in Iran, ethnic discrimination of Hazaras occurs in both Afghanistan and Iran.

6 Migrationsverket “Statistics - Swedish Migration Agency,” text, accessed January 25, 2017,

http://www.migrationsverket.se/English/About-the-Migration-Agency/Facts-and-statistics-/Statistics.html.

7 “Document - THIS IS WHO WE ARE,” accessed May 13, 2018,

https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/52081.

8 Human Rights Watch “World Report 2018: Rights Trends in Afghanistan,” Human Rights Watch, January 18,

2017, https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2018/country-chapters/afghanistan.

Ethnic discrimination of the Hazara people is an issue that arises in both countries, due to differences aside from religion. These include cultural practices, social status and social psychological factors resulting from prejudice and stereotyping which ‘others’ the Hazara people.10 The enactment of discrimination is reported to be widespread, partly due to apparently observable ethnic differences of the Hazara people.11 The facial features of the Hazaras are

often said to be distinctly different to the rest of the Afghan population due to their tribal Mongolian heritage and this obvious physical difference often makes them a clear target for discrimination in both countries.12

According to Monsutti,13 Iran has always been a destination country for Hazara

migration from Afghanistan due to religious compatibility. During the 1980s and 1990s war in Afghanistan, the Hazara were classed as refugees in Iran. This provided them with access to social services such as education and health care. This access was officially withdrawn in 2002 when Iran reclassified Afghani status from “refugees” to “migrants”, and “at the same time reducing various other mechanisms designed to make life in Iran less desirable for them”.14

According to Tober, it became difficult for most Afghans, even those born in Iran, to stay legally in Iran as “resentment toward Afghans has been growing and they feel that they are no longer welcome”.15 This is due to the continued marginalization which Monsutti argues has

resulted in the shared identity among the Hazaras resting not on their Mongol ancestry, but rather on their experience of marginalization16 as the Hazaras tend to be excluded from

acceptance by members of the dominant society, in both Iran and Afghanistan.17

Many Hazara people born outside of Afghanistan have citizenship obtained under Article 2 of the Citizenship law of Afghanistan which states that “all persons born of Afghan mothers and fathers, whether inside or outside Afghan territory shall be considered Afghans

10 Fadlilah Satya Handayani, “Racial discrimination towards the Hazaras as reflected in Khaled Hosseini's the

Kite Runner,” https://www.neliti.com/publications/145437/racial-discrimination-towards-the-hazaras-as-reflected-in-khaled-hosseinis-the-k..p.17

11 Alessandro Monsutti, War and Migration: Social Networks and Economic Strategies of the Hazaras of

Afghanistan, 1 edition (New York: Routledge, 2012). p.172

12 Monsutti. Ibid. p.172

13 Alessandro Monsutti, War and Migration: Social Networks and Economic Strategies of the Hazaras of

Afghanistan (Routledge; 1 edition (7 Dec. 2012), 2012). p.172

14 Diane Tober, “‘My Body Is Broken like My Country’: Identity, Nation, and Repatriation among Afghan

Refugees in Iran,” Iranian Studies 40, no. 2 (2007): 263–85, https://doi.org/10.1080/00210860701269584. p.274

15 Tober. ibid. p.275

16 Monsutti, War and Migration: Social Networks and Economic Strategies of the Hazaras of Afghanistan.

p.172

and shall hold Afghan citizenship”.18 This is the reason why many Hazara have citizenship of Afghanistan despite little or no ties in Afghanistan. The UNHCR study19 on UASC in Sweden mentioned previously states that of the UASC applying for asylum in Sweden, “one third have been internally displaced, with a further one third having lived most of their lives in Iran, despite eight out of ten having been born in Afghanistan”.20 UNHCR also highlights that a

significant number of these applicants “who reach Sweden are members of a small minority group”.21 Studies such as the one conducted by the European council on refugees and exiles

(ECRE) have made recommendations to the European Asylum Support office (EASO) including:

Vulnerable groups should not be returned to Afghanistan under any circumstances. This includes those who have not lived in Afghanistan for long periods and have no family or networks there. European countries should not be “returning” to Afghanistan people who have never been there.22

This argument is the basis of the rationale for Hazara youth remaining in Sweden despite being undocumented and exemplifies why the theoretical framework of belonging and othering resonated with this research into Hazara UUAS youth.

2.1.1 Why have so many Hazara UASC from 2015 become UUAS youth?

There are no official statistics as to the exact number of UUAS youth currently in Sweden. However, understanding the application and appeals process for the UASC who arrived in 2015 provides some insight into why so many stay despite rejection.

Sweden started to become a key destination country for UASC several years prior to 2015 with numbers slowly increasing from a few hundred to a few thousand UASC applications per year23 due to its strong reputation for adhering to the United Nations Convention on the

18 “Citizenship Law of Afghanistan (1936) – 1: Original Citizenship, Naturalization, Citizenship Rights | Open

Corpus of Laws,” accessed May 16, 2018, http://corpus.learningpartnership.org/citizenship-law-of-afghanistan-1936-1-original-citizenship-naturalization-citizenship-rights.

19 “Document - THIS IS WHO WE ARE,” accessed May 13, 2018,

https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/52081.

20 UNHCR (2016) “Document - THIS IS WHO WE ARE.” Accessed May 13, 2018

https://data2.unhcr.org/ar/documents/download/52081 P.14

21 Ibid “Document - THIS IS WHO WE ARE.” P.14

22 “EU Migration Policy and Returns: Case Study on Afghanistan,” ReliefWeb, accessed May 16, 2018,

https://reliefweb.int/report/afghanistan/eu-migration-policy-and-returns-case-study-afghanistan.

23 Migrationsverket “Statistics - Swedish Migration Agency.”

Rights of the Child24 (UNCRC). This was also partly because applications from unaccompanied

minors have been historically handled faster, with an “average handling time of 200 days as of October 2015”.25 Despite this official stance, “the processing time has been well in excess of

twelve to eighteen months for many UASC”.26 This was due to the sheer volume of

applications, especially during the last few months of 2015.

The increased numbers in 2015 were a result of what was dubbed the ‘refuge crisis’27

which saw 162,87728 asylum applications made in Sweden. Of these, a record number of

35,36929 UASC applications were made with 23,480 children from Afghanistan.30 As already

highlighted, 74 percent were Hazaras.31 Statistics from the SMA indicate that approximately

44 percent of the Afghani UASC applications from 2015 have only had an initial decision made to date.32 The total number of rejections of Afghani UASC by the SMA during from 2015 to

2017 indicate an upwards trend of rejections of Afghani UASC with 85 rejections in 2015, 616 in 2016 and 963 in 2017.33

After rejection by the SMA, the UASC can appeal through the Swedish immigration appeals courts. This includes an appeal of the SMA decision to the Migration Court (MC) and, if unsuccessful, one final right of appeal can be made to the Migration Court of Appeal (MCA).34 The rejection by the MCA is the final decision which then informs the MC and SMA

of the applicant’s status. An asylum seeker cannot re-apply for asylum in Sweden until the four year statute of limitations runs out.35 The asylum seeker then has the responsibility to leave

24 UNCHR Convention on the Rights of the Child

https://www.unicef.org.uk/what-we-do/un-convention-child-rights/ Accessed May 13, 2018

25 AIDA Asylum Information Database.

http://www.asylumineurope.org/sites/default/files/report-download/aida_se_2016update.pdf p.15. Accessed May 13, 2018

26 Suzanne Snowden, “Running from Asylum: Unravelling the Paradox of Why Some Unaccompanied

Asylum-Seeking Children Disappear from the System That Is Designed to Protect Them.,” 2017, http://muep.mau.se/handle/2043/22803. accessed May 13, 2018 p.10

27 UNHCR “2015: The Year of Europe’s Refugee Crisis,” Tracks (blog), accessed April 20, 2017,

http://tracks.unhcr.org/2015/12/2015-the-year-of-europes-refugee-crisis/.

28 Migrationsverket ‘Statistics - Swedish Migration Agency’.

https://www.migrationsverket.se/English/About-the-Migration-Agency/Facts-and-statistics-/Statistics/2014.html. Last accessed March 30, 2018.

29 Ibid ‘Statistics - Swedish Migration Agency’. May 12, 2018 30 Ibid ‘Statistics - Swedish Migration Agency’. May 12, 2018

31 UNHCR “Document - THIS IS WHO WE ARE.” https://data2.unhcr.org/ar/documents/download/52081

accessed May 13, 2018 P.14

32 Migrationsverket ‘Statistics - Swedish Migration Agency’.

https://www.migrationsverket.se/English/About-the-Migration-Agency/Facts-and-statistics-/Statistics/2014.html. Last accessed March 30, 2018.

33 “Statistics - Swedish Migration Agency.”

34 “Migration Courts - Sveriges Domstolar,” Text, March 31, 2006,

http://www.domstol.se/Funktioner/English/The-Swedish-courts/County-administrative-courts/Migration-Courts/. Accessed May 13, 2018

35 “Migration Courts - Sveriges Domstolar,” Text, March 31, 2006,

http://www.domstol.se/Funktioner/English/The-Swedish-courts/County-administrative-courts/Migration-Courts/.

Sweden, with the SMA providing support when needed. If the asylum seeker does not leave, then the SMA works in conjunction with the Swedish police to ensure that all steps are taken to apprehend, detain and deport people if required as per the Aliens Act36 which regulates the

Swedish migration policies. Therefore, any rejected asylum seeker who chooses to stay in Sweden lives under the threat of enforced deportation.

In reality, despite this process, the rate of deportation is low. Whilst official figures are difficult to obtain, media reports claim that a Swedish Government report stated that there were 17,358 deportation cases in June 2017.37 The head of the Swedish Border Police, Patrik

Engström, has also reportedly said that “with the scarce time and resources, it was hard to be effective in this part of enforcement”.38 Both media and police reports indicate that with the

2015 changes in policy, “more asylum seekers are staying as undocumented in Sweden, waiting for the four year statute of limitations to run”39 so that they can apply for asylum again.

The UUAS youth who chose to stay in Sweden no longer have UASC benefits in line with the CRC such as the daily allowance, accommodation, legal guardians, access to legal counsel and health care. Once the UASC turns 18, these elements are no longer considered to be an automatic responsibility of the state.40 In saying that, every municipality in Sweden has

the ability to set its own rules and regulations when it comes to the distribution of welfare and some municipalities. For example, Malmö in the Skåne region of Sweden, which is the focus of this research, make extra allowances for undocumented youth.

2.2 Discretionary allowances for UUAS youth in Malmö

The municipality of Malmö is considered to be liberal compared to other municipalities in Sweden with the granting of additional social rights for undocumented migrants. Whilst Swedish law41 allows for a small monthly allowance of 1700 SEK (165 Euros), a health clinic for refugees and access to emergency medical assistance for adult undocumented migrants, Malmö municipality also uses part of its state grant42 to provide education for UUAS. The

36 Global Detention Project. “Sweden Immigration Detention Profile | Global Detention Project | Mapping

Immigration Detention around the World,” Global Detention Project (blog), accessed May 13, 2018, https://www.globaldetentionproject.org/countries/europe/sweden.

37 The local. “Swedish Police Struggle to Carry out Deportation Orders - The Local,” accessed May 13, 2018,

https://www.thelocal.se/20171004/swedish-police-struggle-to-carry-out-deportation-orders.

38 “Swedish Police Struggle to Carry out Deportation Orders - The Local.”

39 Elin Hofverberg, “Laws Concerning Children of Undocumented Migrants,” Web page, September 2017,

https://www.loc.gov/law/help/undocumented-migrants/sweden.php.

40 Hofverberg. ibid.

41 Hofverberg, “Laws Concerning Children of Undocumented Migrants.” ibid.

42 Skolverket “Bidrag för utbildning av barn som vistas i landet utan tillstånd,” accessed May 17, 2018,

https://www.skolverket.se/skolutveckling/statsbidrag/grundskole-och-gymnasieutbildning/papperslosa-barn-1.203490.

extension of social rights to the UUAS youth creates a space for them to exist in Malmö in a form of ‘included exclusion’43 which goes a little way to explain Malmö’s marked presence of undocumented migrants as opposed to in other municipalities.

2.2.1 Youth Centre project for UUAS youth in Malmö

The inspiration for this study was observing the level of inclusion of the UUAS at the youth centre44 (also referred to as the centre) hence a little more description of the centre here. The Monday night drop-in session described in the introduction is part of a wider three year project (2016 to 2019) for this NGO that have lawyers that provide free, confidential legal advice and social workers providing support for all UUAS youth aged 18 to 25 who are located in the Malmö area.

Whilst the centre is non-discriminatory in regards to country of origin, gender, religion, sexual orientation or any other element of diversity, the bulk of the attendees are from Afghanistan and only males attend the centre. During an interview in March 2018, the project director of the youth centre indicated that 319 undocumented youth have sought free legal advice for Migration Board appeals since the project started.

The youth attend drop-in sessions on Monday nights, Thursdays afternoons or weekend activities organized by the centre to socialize with other undocumented youth in a safe space. As I only volunteer during the Monday night sessions, all my observations and data collection from the UUAS youth at the centre are from this bounded time frame and interactional space.

43 Maja Sager, Everyday Clandestrinity: Experiences on the Margins of Citizenship and Migration Policies

(Lund: University, 2011). p.60

44 This is a pseudonym for a non-governmental organisation (NGO) that operates in Malmö. I

have been asked by the director of the centre to anonymize this organisation due to the sensitive nature of its operations and attendees.

3 Previous studies

The prior literature focused on in this section outlines the key discussions that have influenced the theoretical and analytical aspects of my study. They were selected to highlight some of the discussion surrounding complexities of how a marginalised migrant group constructs a sense of belonging, most importantly within the context of political and emotional frameworks.

3.1 A conceptual shift in the notion of belonging

The academic and social debates around borders, nationality and social cohesion, along with the use of more constructivist approaches to research have inspired a change in the way scholars have discussed the concept of belonging over the past few decades.

The concept of belonging has been explored extensively by Anthias who has published several research papers which have utilised both discourse analysis and empirical studies to help create a new perspective when discussing belonging. The empirical studies conducted in 1998 consisted of interviews with four groups of Greek Cypriot diasporas45 which along with the discourse analysis helped better understand diasporas, along with aspects of identity construction that create social stratification46 and social divisions.47 Anthias argues that

simply understanding ethnic or racial identity does not provide a true insight into a migrant’s sense of belonging in the society they live in.48 Anthias suggests that the traditional notion of

identity is ambiguous and therefore no longer a solid heuristic device. She raises the concept of using the elements signposted by identity to view the concept of identity differently and most importantly, as a dynamic process. She posits that asking a migrant to explain how to describe where they belong and probing for an answer in terms of race or ethnicity could create inauthentic information. This narrow view could disregard their multiplicity of location and social placement within each location.49 Hence Anthias raises the concept of

translocational positionality which refers to how people see their place in the world. It

45 Floya Anthias, “Evaluating `Diaspora’: Beyond Ethnicity?,” Sociology 32, no. 3 (August 1, 1998): 557–80,

https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038598032003009.

46 “The Material and the Symbolic in Theorizing Social Stratification: Issues of Gender, Ethnicity and Class -

Anthias - 2001 - The British Journal of Sociology - Wiley Online Library,” accessed May 14, 2018, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00071310120071106.

47 Floya Anthias, “Where Do I Belong?: Narrating Collective Identity and Translocational Positionality,”

Ethnicities 2, no. 4 (December 1, 2002): 491–514, https://doi.org/10.1177/14687968020020040301.

48 Anthias. Ibid.

49 Floya Anthias, “Where Do I Belong?: Narrating Collective Identity and Translocational Positionality,”

evokes the intersectional elements of social categories we identify with, along with who, what and where we identify with.50

Werensjö builds on the discussion from Anthias through 201451 and 201552 qualitative, empirical studies in which Wernesjö interviewed 17 former UASC in Sweden. These interviewees were a mix of males and females who had been granted permanent residency and were navigating belonging in Sweden. In these studies, Wernesjö emphasized process, movement and negotiation in her investigation into these youth sense of belonging53 in ways

that challenge essentialist notions of ethnic and racial belonging along with that of national identity”.54

Youkhana also adds to this discussion from a discourse analysis perspective, challenging the underlying notions of belonging as a collective and in terms of ethnic or national boundaries.55 Youkhanas push for a conceptual shift, argues for a greater emphasis on

geographic location as an analytical factor that cross-cuts established categories such as race, class, gender, and stage in the life cycle.56 This evolution of the way belonging is

conceptualized reflects the complexity of changing social, political, and cultural landscapes. This includes the interactions between people, places and objects. These changes also addresses the underlying power relations”.57 The constructivist paradigm shift in how the concept of

belonging is discussed, is emphasized by Youkhana who stresses that there is a need for a greater understanding of how belonging is produced but is also contested in a matrix of ways.58

This stance is in line with the theoretical framework of this study, as described in section 4.

50 Floya Anthias, “Where Do I Belong?: Narrating Collective Identity and Translocational Positionality,”

Ethnicities, July 24, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1177/14687968020020040301 p.499

51 Ulrika Wernesjö, “Conditional Belonging: Listening to Unaccompanied Young Refugees’ Voices” (Acta

Universitatis Upsaliensis, 2014).

52 “Landing in a Rural Village: Home and Belonging from the Perspectives of Unaccompanied Young Refugees:

Identities: Vol 22, No 4,” accessed May 21, 2018,

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/1070289X.2014.962028?journalCode=gide20.

53 Ulrika Wernesjö, “Conditional Belonging: Listening to Unaccompanied Young Refugees’ Voices” (Acta

Universitatis Upsaliensis, 2014).

54 Wernesjö. ibid

55 Eva Youkhana, “A Conceptual Shift in Studies of Belonging and the Politics of Belonging,” Social Inclusion

3, no. 4 (July 8, 2015): 10–24, https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v3i4.150.

56 Youkhana. ibid 57 Youkhana. p.10 58 Youkhana. ibid

3.2 Belonging as a mindset

A 2004 ethnographic study in Sweden by Brekke highlighted the “ambivalence of asylum policies”59 and the effect this has on the individual and their capacity for wanting to belong to

the host society. Brekke created a framework to enable the “understanding of waiting under special exile conditions”.60 Brekke used 15 interviews with institutional actors and UASC to

produce a model to better understand the mindset of asylum seekers waiting for decisions on their application. This is specifically relevant for gauging why some individuals fare better than others especially in regards to their attachment to a community. I consider this research on waiting under special exile conditions61 an important addition to the discussion around why

some asylum seekers are more open than others when imagining themselves belonging to the host society. The four categories of mindset of asylum seeker as described by Brekke62, were

outlined as follows. Firstly, the ‘ideal-applicant’ who is oriented towards both integration and return, the second was the ‘exile activist’, a person who stays oriented towards their home country with no intent of integrating into society, hoping to return when possible, the third was the ‘bridge burner’ who chooses to mentally and practically pursue a future in Sweden as return is not an option and ‘the waiter’ who is literally in limbo, not taking any active measures to either return nor to integrate into Swedish society.

Inspiration from Anderson’s theory of Imagined Communities is evident in the descriptors of the ‘ideal-applicant’63 and the ‘bridge burner’64 as they choose to explore the avenue to

remain in the host country. This suggests that they can picture themselves as part of the imagined community in which they desired to stay. Anderson’s theory of Imagined Communities uses discourse analysis in an attempt to stimulate discussion on nationalism from a Postmodernist perspective with both Marxist and Capitalist underpinnings. Anderson’s stance is that nationalism consists of invented traditions which are a political factor in modern state making. He posits that nations are ‘imagined communities’65 with communal societal

bonds that exist within the minds of the members of the society. Anderson stresses that “communities are to be distinguished, not by their falsity/genuineness, but by the style in which

59 Jan-Paul Brekke, While We Are Waiting: Uncertainty and Empowerment Among Asylum-Seekers in Sweden

(Institute for Social Research, 2004).

60 Brekke, Jan-Paul. 2004. While We Are Waiting: Uncertainty and Empowerment Among Asylum-Seekers in

Sweden. https://brage.bibsys.no/xmlui/bitstream/handle/11250/2440626/R_2004_10.pdf?sequence=3.Brekke. p.7

61 Brekke. Ibid p.7 62 Brekke. Ibid p.49

63 Brekke, While We Are Waiting: Uncertainty and Empowerment Among Asylum-Seekers in Sweden. 64 Brekke. Ibid p.49

they are imagined”.66 Andersons elicits the concept of nations being ‘limited’, ‘sovereign’ and

constructed of ‘communities’. These consist, in the imagination rather than in reality, of an exclusive fraternity of people who exclude ‘others’ not perceived to be part of this imagined in-group.

The concept of being part of the imagined community is also reflected in the empirical studies of Wernesjö discussed earlier. Wernesjö uses interviews to draw on the differing negotiations of belonging to a particular place through the lens of the Swedish imagined community. In this study, Wernesjö also questions interviewee perception of the impacts of race, racialization and racism in terms of how they affect the migrant’s notion of belonging to a place. Additionally, Wernesjö investigates the intersectional lens by also exploring what Sirriyeh calls a transitional ‘in-between space’.67 Wernesjö investigates this in regards to how

the asylum seeker negotiates that in-between space which is an important consideration towards how they articulate their sense of belonging.

There have been many studies I would have liked to have included in this literature review however this section has included the most essential, highlighting key areas of discussion that intrigued me the most when framing my research design.

I believe that there is a gap in the literature in terms of what the UUAS youth that are legacy UASC applicants from 2015 are doing now. In particular, how they are navigating undocumented life in Sweden rather than facing the prospect of going back to a marginalised life in the country where they came from. The numbers are significant enough to investigate this phenomenon.

66 Anderson. Ibid p.6

67 Ala Sirriyeh, “Home Journeys: Im/Mobilities in Young Refugee and Asylum-Seeking Women’s Negotiations

4 Theoretical Framework

The concepts and theories most central to this study include those that relate to both institutional and societal impacts on an individual sense of belonging. Whilst there are many different definitions as to what the concept of belonging entails, this study takes inspiration from the explanation of the concepts by Yuval-Davis, Anthias and Youkhana.

4.1 The concept of belonging

This key concept is constructed through the use of linking complimentary theoretical and conceptual components used to explain belonging. Explanations as to linkages between them is provided in both this section and in the analysis.

According to Yuval-Davis, the concept of belonging consists of two interrelated parts, political and emotional therefore they will be described separately in 4.1.1 and 4.1.2.

4.1.1 Political belonging

The political aspects of belonging is the major aspect of belonging that can adversely affects UUAS youth by the inclusionary or exclusionary nature of the sum of its parts. This is because it includes the participatory membership of a community in terms of an individual enjoying entitlements such as citizenship, status and inclusion. Marshall68 defines citizenship as being ‘full membership of the community, with all its rights and responsibilities’. This description is notable as it does not reference the nation-state at all, paving way for discussion of the multi-layered, participatory nature of what constitutes citizenship of a geographic place.

Nationalist identities, political views and values facilitate political borders or boundaries that are constructed by the societal institutions and power dynamics which dictate the nature of the social demarcations. These can affect individuals or collectives in varying ways. This includes activism from differing political agendas fighting for what requirements should be invoked for membership of a community as the question of what constitutes belonging to a nation-state is highly contested. The expectation of rights and responsibilities of members differs between political systems who expect various degrees of loyalties to the state by its members.

An aspect of political belonging is power which in the past has been described by Weber’s classic theory of power which “differentiated between those dependent on individual

68 T.H Marshall Citizenship and Social Class (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1950); T. H. Marshall,

Social Policy in the Twentieth Century [1965] (London: Hutchinson 1975); T. H. Marshall, The Right To Welfare and Other Essays (London: Heinemann Educational Books 1981). in Nira Yuval-Davis, “Belonging and the Politics of Belonging,” Patterns of Prejudice 40, no. 3 (July 1, 2006): 197–214,

resources and those emanating out of legitimate authority”.69 However Yuval-Davis suggests

this description has been superseded due to the effects of a more diffused power structure in the contemporary world. The main theories and concepts currently surrounding political belonging are now largely acknowledged to be from Bourdieu and Foucault.

Bourdieu’s Theory of Symbolic power is attributed to the concept of belonging as it involves the concepts of societal structures, individual agents and the social spaces that are divided into fields. Structures refer to societal constructs of rules and frameworks that condition thoughts and actions, whereby agency is the concept that individuals have free choice and options.70 The “social fields” refer to the areas and elements of interactions that have shared

meanings to the individuals sharing those spaces.71 The symbolic power posed by Bourdieu is

described as “Doxa”, which is when socially constructed elements of society are perceived to be the natural order and therefore accepted.72 Bourdieu points out that the issue with this, is that this construct is changeable, therefore making power dependent on context and over time. Bourdieu also incorporates the concepts of capital – social, cultural and symbolic73 in the theory

of symbolic power. The theories of Bourdieu and Foucault are fairly reflective of each other however the scholars differ in how they view individual responses to power as according to Foucault, the structure is the key driver of power.

Foucault uses the term biopower which he refers to as a ‘technology of power’.74 This proposes that productive power can exist alongside a more repressive sovereign power.75 Examples of techniques of repressive sovereign power can be seen in the enforcement of migration laws as they ‘incite, reinforce, control, monitor, optimize and organize”76 the immigrant population. Along with this, Yuval-Davis observes that this is in line with the

69 Nira Yuval-Davis, “Belonging and the Politics of Belonging,” Patterns of Prejudice 40, no. 3 (July 1, 2006):

197–214, https://doi.org/10.1080/00313220600769331.p.206.

70 Matthias Walther, Repatriation to France and Germany: A Comparative Study Based on Bourdieu’s Theory

of Practice, 2014 edition (Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler, 2014). p.7

71 Walther. Ibid. p.8

72 Maria Jensen, “Structure, Agency and Power: A Comparison of Bourdieu and Foucault,” accessed May 22,

2018,

https://www.academia.edu/10258956/Structure_Agency_and_Power_A_Comparison_of_Bourdieu_and_Foucau lt. p.7

73 Yuval-Davis Yuval-Davis, “Belonging and the Politics of Belonging.”

74 Mona Lilja and Stellan Vinthagen, “Sovereign Power, Disciplinary Power and Biopower: Resisting What

Power with What Resistance?,” Journal of Political Power 7, no. 1 (January 2, 2014): 107–26, https://doi.org/10.1080/2158379X.2014.889403.

75 Mona Lilja and Stellan Vinthagen, “Sovereign Power, Disciplinary Power and Biopower: Resisting What

Power with What Resistance?” Journal of Political Power 7, no. 1 (January 2, 2014): 107–26, https://doi.org/10.1080/2158379X.2014.889403. p.109

76 Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality: Volume I: An Introduction by Michel Foucault (Pantheon Books,

Foucauldian construct of governmentality creating a ‘disciplinarian society’77 which involves

“impersonal mechanisms of power,”78 and are beyond individual agency.

Individual agency is also threatened by repressive power through its enforcement of the notion of “us” and “them”. This is described as the post-colonial theory of ‘othering’. ‘Othering’ describes the processes at play when a group or an individual is denied the rights and sociocultural affordances enjoyed by those within the imagined community. Anderson argues that the imagined element is due to the fact members maintain the community has fixed boundaries of a perceived fraternity despite never meeting each other. This imaginary ignores the reality of any inequality or exploitation within the community. This is why othering and imagined communities are interrelated as they explain how the concept of fear of others threatens the notion of security, prompting the ordering and bordering of communities.79

All these elements surrounding the politics of belonging center on the sociology of power. However it is when this is combined with the emotional aspect of belonging that it creates a “normative values lens which filters the meaning of both to individuals and collectivities”.80

4.1.2 Emotional belonging

Othering and imagined communities can also be seen as aspects of emotional belonging, however there are key differentiators between the emotional and the political elements of belonging which are crucial to understand when tackling social phenomena such as nationalism or race. The emotional aspect of belonging includes personal feelings towards different groups. These personal feelings stem from elements that are termed social location, identifications and attachments.

The concept of a social location is one that can be viewed through an intersectional lens. It describes aspects of an individual including age, gender, sexuality, ability, class, race or history, to name a few. Yuval-Davis posits that this notion of belonging can be imagined and narrated as all elements are dynamic. They are also reliant on power relations between different individual or collective entities and as they are also situational, they are subject to

77 Yuval-Davis, “Belonging and the Politics of Belonging.” pp. 197-213 78 Yuval-Davis. ibid

79 Henk Van Houtum and Ton Van Naerssen, “Bordering, Ordering and Othering,” Tijdschrift Voor

Economische En Sociale Geografie 93, no. 2 (May 1, 2002): 125–36, https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9663.00189.

80 Yuval-Davis, “Power, Intersectionality and the Politics of Belonging,” in The Palgrave Handbook of Gender

and Development, ed. Wendy Harcourt (London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2016), 367–81, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-137-38273-3_25.

change.81 Yuval-Davis argues that a person’s social location can be seen as occupying a space along an axis of power that is fluid and affected by history, culture and politics. This intersectional social location can be viewed differently depending on what social grouping or division is being discussed. Yuval-Davis stresses that the discourse on social locations is often racialized if conflated with the concept of identifications and emotional attachments.82

Identification and attachments refer to the stories people tell in relation to themselves; and these can describe individual or collective selves. This self-identification is seen as being an evolving, transitional state based on the emotional need to belong and to be accepted through building attachments to people and places. Therefore it can also include describing oneself in terms of abilities or physical prowess in order to identify with particular groupings. The creation of belonging through social location and identity is thought to happen through a combination of specific social practices, which are essential for attachment to groups. There is also a reliance on adhering to construction and reproduction of collective and individual narratives.83

This theoretical framework is valuable for this study as the dynamic interplay of the political and emotional elements surrounding belonging are quite complex. Keeping these elements in mind whilst analysing the data will provide a richer understanding as to how the political or emotional belonging affect the lives of the youth.

81 Nira Yuval-Davis, Floya Anthias, and Eleonore Kofman, “Secure Borders and Safe Haven and the Gendered

Politics of Belonging: Beyond Social Cohesion,” Ethnic and Racial Studies 28, no. 3 (May 2005): 513–35, https://doi.org/10.1080/0141987042000337867. p.521

82 Nira Yuval-Davis, “Belonging and the Politics of Belonging.” p.202 83 Nira Yuval-Davis, “Belonging and the Politics of Belonging.” ibid. p.202

5 Research design

This research is designed using an inductive, qualitative case study approach. The qualitative methods of participant observation and semi-structured interviews were employed during volunteering sessions at the youth centre from August 2017 to May 2018. The data from these methods, in conjunction with the theoretical framework and reflections on previous studies, will be used to answer the research question.

5.1 Research Philosophy

This research utilizes a qualitative, exploratory case study underpinned by an ontological and epistemological ideology that has a hermeneutic-constructivist approach. This paradigm “sees the world as constructed, interpreted, and experienced by people in their interactions with each other and with wider social systems”.84 The philosophical underpinning

and wider research design is appropriate for the aim of this study as it enables interviewees to develop “subjective meanings of their own realities and come to appreciate their own construction of knowledge”85

5.2 Qualitative case study approach

This study is based on a qualitative case study approach which is most suited to the collection of data that provides a rich description of the bounded phenomenon of the UUAS youth in Malmö from their emic perspective. An emic view is the viewpoint of those being studied to enable understanding of how they “make sense of their world, interpret and attribute meaning contextually to their experiences”.86

With this goal in mind, an inductive, qualitative approach was essential for this study. A quantitative study would have been not considered as the nature of this study was designed hermeneutically which involves eliciting descriptive and interpretative language of experiences not statistic inference. Despite the smaller sample sizes of qualitative studies, the methods of participant observation and semi-structured interviews provided the required theoretical saturation. To obtain the desired results, this qualitative case study approach loosely followed

84 F Tuli, ‘The Basis of Distinction Between Qualitative and Quantitative Research in Social Science: Reflection

on Ontological, Epistemological and Methodological Perspectives’, in Ethiopian Journal of Education and Sciences, vol. 6, 2010.p.100

85 Cohen, Manion & Morrison (2000) in Tubey, R et al (2015) Research Paradigms: Theory and Practice.

Research in Humanities and social sciences journal

http://www.iiste.org/Journals/index.php/RHSS/article/view/21155. p. 225

86 Sharan B. Merriam, Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation, Revised, Expanded edition

Crotty’s hermeneutic circle87 which is inductive, collecting data in the natural setting. It is analyzed inductively, focusing on each part to understand the whole whilst establish patterns and themes. The ontological perspective is emphasized when presenting the data using the interviewee’s voice and providing a complex description, interpretation and discussion in light of the research problem.

This was deemed to be a case study under the definition of it being a “strategy for doing research which involves an empirical investigation of a particular contemporary phenomenon within its real life context using multiple sources of evidence”.88 Conducting the research

within the timeframe required for this study – and at minimal cost – was an important consideration for this research. The relationships I had built with the UUAS youth in the centre also provided a natural framework conducive to this exploratory research design. Whilst the ‘case’ is considered to be how UUAS youth experience both emotional and political belonging, it could not be considered without the context, which is their marginalised status in both their home country and Sweden. It is only within this context that the study can help to understand the UUAS experience of belonging to a community. The use of context and definition to create boundaries around the case are important to ensure that the scope of the study remains within its delimitations. The definition of the bounded location of Malmö, the parameters of the criteria for the participant observation and semi-structured interviews helped to determine the breadth and depth of the study.

Volunteering at the youth centre provided lengthy periods with the UUAS youth in an environment in which they were comfortable. This suited the ‘emergent and flexible’89 design

of this qualitative study. The key to this research was to understand the holistic, emic perspective of the experience of the Hazara in Malmö. Therefore the methods of semi-structured interviews and participant observation were employed to identify themes that corresponded to the theoretical framework of the emotional and political belonging.

5.3 Semi-structured interviews

The exploratory nature of this case study made the use of semi-structured interviews the most logical choice due to the flexible nature of this approach. This interview format used

87 Margo Paterson, “Using Hermeneutics as a Qualitative Research Approach in Professional Practice,” n.d., 21.

p.345

88 C Robson, Real World Research: A Resource for Social Scientists and Practitioner-researchers by Colin

Robson, John Wiley & Sons, 1993. p.146

89 Merriam, Sharan B. Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation. Revised, Expanded

the combination of structured and unstructured questions. The structure provide a guide from which to deviate from into a tailored, deeper investigation of the experience of the interviewee when and where appropriate throughout the interview. It could be considered that the first few interviews were ‘pilot interviews’ in so far as they gave me the opportunity to test the questions with the target audience and inspired rearrangement of the order of questions, or deletion of those that created repetition of a previous answer.

Ten interviewees were chosen using pre-defined criteria after initial participant volunteering and observation. My rationale for selecting interviewees was to create a homogenous view of a specific subset of UUAS youth. Therefore, it was important that they were all Hazaras that had arrived in 2015 from Iran. These were the choices I made on the basis of their large numbers seeking asylum in Sweden as described in section 2. This group had also experienced transition from UASC to undocumented youth which would have had an impact on how they experienced belonging in light of multiple marginalization.

In line with the philosophical lens of this research design and ethical considerations outlined in 5.10, interviewees were well briefed as to what to expect prior to the interviews. Questions were grouped into categories to help with later thematic analysis and explanations were given to ensure that the interviewees knew they would be “seen as the writers of their own history rather than objects of research”.90

Two of the interviews were conducted in English by myself, with the remaining eight in a combination of English and Swedish with translators in the room. I am a fluent English speaker with only conversational Swedish. The translators – all known and trusted by the youth – assisted with interviews conducted in Swedish. The use of translators rather than official interpreters was solely down to cost which was a trade-off that needed to be made. The director of the youth centre allowed their staff to work as translators for this study, ensuring it was considered to be a part of their job which helped prioritize their time for the interviews. All interview answers were recorded verbatim on the computer and then repeated to the interviewee in Swedish with the translator present in a bid to ensure accuracy and transparency. The setting for the interviews was also a very important factor to consider for both comfort of the interviewee and quality of response. For the first interview, we kept it casual and sat alone in a quiet yet communal space. Since it was in the privacy of the youth centre with only a closed, trusted group of people, I did not even consider this would be problematic. However, I noticed the interviewee’s discomfort during the interview and despite us being

90 Casey, K (1993) in Tubey, R et al (2015) Research Paradigms: Theory and Practice. Research in Humanities

alone, he was not relaxed and kept looking around to see if anyone was going to walk in. He was so nervous, I suggested we move to a private room with a door and he instantly relaxed. That experience taught me a very valuable lesson to ensure all future interviews were conducted in a closed, private space.

5.4 Participant Observations

The participant observations were made solely during Monday night drop-in sessions The observations made have been attributed to as being from ‘informants’, which differentiates this data from the information gained from the interviewees responses from semi-structured interviews, which are attributed to specific individuals. The participant observations consisted of watching and participating in the variety of activities conducted within the centre, recording in a notebook what the youth were involved with and the interactions they had with each other and the staff. The communal cooking and meal time brought an interesting dynamic to the observations as the conversations were more relaxed and I could watch the interplays between the youth as to who were more social than others.

5.5 Sampling and criteria

Due to the youth centre providing an information-rich91 environment in which to

conduct this case study, a purposeful sampling technique which is a non-probability selective technique was the most appropriate to ensure that the interviewees were specifically selected based on my criteria for this study.92 Qualitative inquiry typically focuses on relatively small

samples that can then be studied in-depth93 which also suited this purposeful sampling method.

The initial criteria for interviewees of this study was simply “youths 18-21 currently living in Malmö undocumented, having arrived in Sweden as a UASC”. However, after initial interviews with 17 UUAS youth, it was clear that the criteria should be refined to create a more homogenous grouping as described above. Purposive sampling continued to be used to achieve this research goal of selecting the interviewees. The decision to focus on a homogenous grouping was not for any other reason other than to “narrow the range of variation and focus on similarities”94 to enable a more simplified analysis, allowing a more in-depth exploration of

this subgroup.95

91 Michael Patton (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods (pp. 169-186). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. 92 G Guest, A Bunce & L Johnson, ‘How Many Interviews Are Enough?: An Experiment with Data Saturation

and Variability’, in Field Methods, vol. 18, 2006, 59–82.

93 Michael Patton (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods (pp. 169-186). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. 94 LA Palinkas et al., ‘Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method

implementation research’, in Administration and policy in mental health, vol. 42, 2015, 533–544.

The results of the sampling approach led to the final selection of the 10 interviewees. Theoretical saturation – the point where no new information or themes are observed96 – had

been achieved by the eighth interview. Therefore, the reduction of interviewees used in the study had no adverse implication to the validity or reliability of the research. As the goal was to “describe a shared perception, belief, or behavior among a relatively homogenous group”,97

the sample of 10 was sufficient.

5.6 Gathering Data

Details of the data collection methods of participant observations and semi-structured interviews are described throughout this section, therefore only the ontological approach will be outlined here. The data gathering employed a hermeneutic style with a three-fold structure which is described a Dasein98. This it looks at the past, present and future99 providing a more holistic understanding of the development of the continuum of experiences around the emotional and political belonging during the lives of the interviewees to put the present into context.

5.7 Access to the research field

Access to the youth centre and introduction to the youth began in spring 2017 during research for my bachelor thesis on the historical issue of UASC disappearing from the system in Sweden during 2015.100 Volunteering at the centre inspired this case study for which formal

research began in September 2017.

Aside from the youth themselves, the youth centre coordinators were instrumental in this research, updating me on any changes in laws along with any major events involving the youth during the week. The staff also provided me with full access to anything I required for this study, including assisting with communication in multiple languages which was invaluable.

96 G Guest, A Bunce & L Johnson, ‘How Many Interviews Are Enough?: An Experiment with Data Saturation

and Variability’, in Field Methods, vol. 18, 2006, 59–82.

97 Guest, Bunce and Johnson, ibid. p. 76

98 Paterson, “Using Hermeneutics as a Qualitative Research Approach in Professional Practice.” p.346 99 Paterson. p.346

100 Snowden, S. Running from Asylum.

https://muep.mau.se/bitstream/handle/2043/22803/Suzanne%20Snowden%20Disappearing%20UASC%20thesis %20for%20archive%202017.pdf?sequence=2 Malmo University 2017.