J

Ö N K Ö P I N GI

N T E R N A T I O N A LB

U S I N E S SS

C H O O L JÖNKÖPING UNIVERSITYNeeds and Wants in Online

Communities

A case study of Ungdomar.se

Bachelor Thesis in Business Administration

Author: Frost, Emma 881203

Persson, Sanna 910403 Sandström, Jennifer 920305 Tutor: Taube, Magnus

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the people who have made our bachelor thesis possible! These persons have contributed to the fulfilment of the research purpose and to a success-ful completion of the study, for which we are extremely thanksuccess-ful.

Firstly, we want to express our gratitude to Junedalsskolan, Kunskapskällan, and Brunnen. They enabled us to collect the data needed for answering the research questions. Secondly, we would like to give a special thanks to Ungdomar.se, who did not only provide us with data and information, but also insight and support. Kim Jakobsson and André Vifot Haas, we are sincerely grateful for the collaboration. We would also like to thank Jesper Sand-ström for his excellent language skills.

Finally, we would like to express our greatest gratitude to our tutor, Magnus Taube, who has guided us throughout this thesis, and provided us with his knowledge, support, and ad-vice, all the way from Ecuador.

Emma Frost Sanna Persson

Jennifer Sandström

Bachelor Thesis in Business Administration

Title: Needs and Wants in Online Communities – A case study of Ungdomar.se

Authors: Emma Frost, Sanna Persson and Jennifer Sandström

Tutor: Magnus Taube

Date: 2013-05-14

Subject terms: Marketing, Consumer behaviour, Online communities,

Youths, Motivation, Needs and wants.

Abstract

Background

Young people constitute a fast growing group of Internet users and they are considered an important market segment. In Sweden, on average nearly 97 % of the people between the ages of 15-19 use Internet every day. A great deal of these people use online communities, and in order for these communities to succeed, it is vital to understand what content the youths perceive as valuable and useful. Furthermore, since using an online community takes time and effort, the community should fulfil a need among its users. Since it is no easy task to understand what motivates consumers, online communities should strive to reach a consensus in common characteristics among these individuals, in terms of what needs and wants they seek to satisfy in online communities.

Purpose

The purpose of this thesis is to explore what needs and wants youths in Sweden seek to satisfy in online communities. To demonstrate the findings, Ungdomar.se will be evaluated, and given recommendations accordingly.

Method

In order to fulfil the purpose of this thesis, a descriptive and explorative study was con-ducted, consisting of both quantitative and qualitative data. The collection of data was made through a survey among youths, and by semi-structured interviews with Ungdomar.se and two people working at the Youth Centre Brunnen.

Conclusion

The authors have identified a set of needs and wants, that youths seek to satisfy in online communities. This has further been applied to the online community Ungdomar.se, and they have been provided with recommendations on how to satisfy these needs and wants.

Table of Contents

1

Introduction ... 1

1.1 Background ... 1 1.2 Specification of problem ... 2 1.3 Purpose ... 2 1.4 Contributions ... 2 1.5 Delimitations ... 32

Pre-understanding of the Topic ... 4

2.1 Online consumer behaviour ... 4

2.2 Online community ... 4

2.3 Definitions ... 5

3

Frame of Reference ... 6

3.1 Internet and Web 2.0 ... 6

3.2 Motivation theory - Needs and wants ... 6

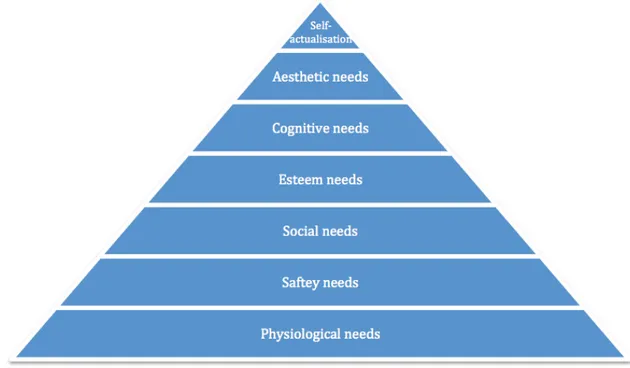

3.2.1 Maslow’s hierarchy of needs ... 7

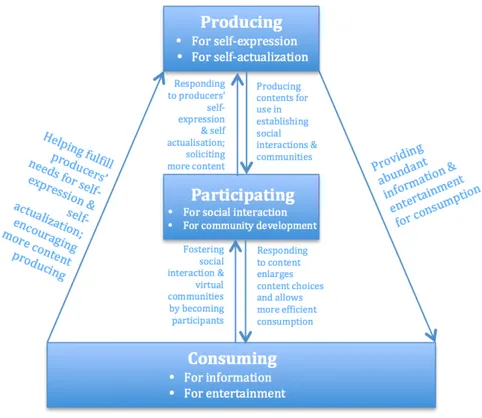

3.2.2 User-generated medias (UGMs) ... 9

3.3 Creating a sustainable online community ... 11

4

Method and Methodology ... 13

4.1 Methodology ... 13 4.1.1 Research philosophy ... 13 4.1.2 Research purpose ... 13 4.1.3 Research approach ... 14 4.2 Method ... 15 4.2.1 Case study ... 15 4.2.2 Target population ... 15 4.2.3 Research strategy ... 16 4.2.4 Data collection ... 17 4.2.5 Sampling ... 17 4.2.6 Time horizon ... 19

4.2.7 Quality of the study ... 19

4.2.8 Summary of the method ... 22

4.2.9 Discussion on the method ... 22

5

Empirical Findings ... 24

5.1 Findings from the questionnaire ... 24

5.2 Findings from Brunnen ... 30

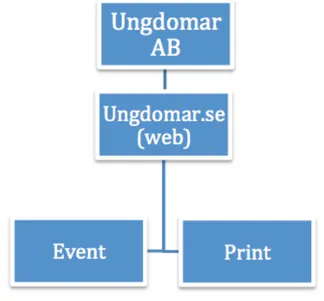

5.3 Findings from Ungdomar.se ... 32

6

Analysis ... 35

6.1 Youths’ needs and wants in online communities ... 35

6.2 Creating a sustainable online community ... 37

6.3 Youths communicating online ... 41

7

Conclusion ... 42

8

Discussion ... 43

8.2 Suggestions for future research ... 44

9

List of References ... 46

Appendices ... 51

Figures

Figure 1 - The hierarchy of needs (Gleitman et al., 2011) ... 8 Figure 2 - Interdependence of people's consuming, participating, and producing on

user-generated media (Shao, 2009) ... 11 Figure 3 - Research strategy, created by the authors (2013) ... 16 Figure 4 - Structure of Ungdomar AB, created by the authors (2013) ... 32

Tables

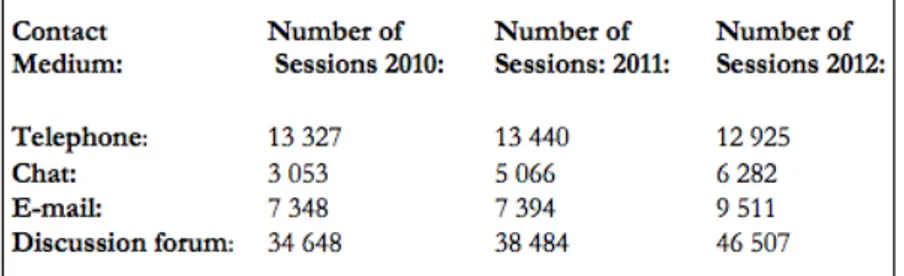

Table 1 - Statistics from BRIS-rapporten (BRIS, 2011b, 2012 & 2013) ... 6 Table 2 - Maslow's hierarchy of needs, in online and offline settings (Kim, 2000) .... 9

1 Introduction

This section will present an introduction to the broader concept of the study. The reader will be given a background to the problem, followed by the problem discussion and the purpose. Further on, the authors will declare the contributions of the study and finally, delimitations of the study will be explained.

1.1 Background

Global Internet usage is steadily increasing (Kaur & Medury, 2011) and it is considered an important source of information and entertainment (Findahl, 2012). A great deal of people have access to computers and the Internet, and youths constitute a fast growing group of Internet users (Rideout, Foehr & Roberts, 2010). According to Sørensen (2010), people born after 1986 are part of the Internet Generation, due to their heavy Internet usage and the fact that they have been familiar with the phenomenon since their childhood. This In-ternet Generation has defined a new group of consumers (Lee, Conroy & Hii, 2003) and as Chan and Fang (2007) declare, these young people comprise an important market segment. Therefore, online communication platforms that target young people, should be designed with regard to their needs and wants (Chan & Fang, 2007).

In Sweden, on average nearly 97 % of the people between the ages of 15-19, use Internet on a daily basis. Furthermore, a majority of these people use online social networks (Findahl, 2012). These can take the form of online communities.1 Bishop (2007) argues that for an online community to succeed, it is vital to understand what motivates consumers and how they make the decision of whether or not to use the online community. Further-more, Koh et al. (2007) state that consumers who perceive the content as useful will feel motivated to continuously use the community, which in turn will lead to online communi-ties that prosper. In addition, the community should fulfil a need among their consumers, since using an online community takes time and effort (Kim, 2000). As proposed by Barnes and Pressey (2011), “understanding what motivates individuals and their dominant needs would seem a useful precursor to targeting them and effectively fulfilling these needs” (p. 246).

As an established online community, the authors2 consider Ungdomar.se interesting since they currently focus on adapting and developing their website with respect to their target group. Ungdomar.se is a Swedish online community, targeting young people, with 110 000 unique visitors a week (Ungdomar AB, 2013b). According to the CEO, Kim Jakobsson (2013), Ungdomar.se aims to provide a platform that empowers youths in society and ena-bles them to freely express their opinions. The authors believe that online communities could gain from exploring what needs and wants youths seek to satisfy on their websites. This is in line with Jakobsson (2013), who argues that it is essential for an online

1 Online communities are Internet based platforms used for information sharing, problem solving and com-municating common interests (Andrews, 2002).

ty to possess knowledge about the needs and wants of their consumers. Since Ungdomar.se targets a wide range of young people, similarly to other online communities, and strives to develop their business according to this target group, the authors consider this a suitable case study for this thesis.

1.2 Specification of problem

Understanding consumer behaviour is no easy task (Kotler, 2000). Koh et al. (2007) simi-larly state that it is not simple to understand what motivates consumers of online commu-nities; these individuals are both physically dispersed and differing in various aspects, such as age and education. Therefore, Koh et al. (2007) stress the importance for such commu-nities to reach a consensus in common characteristics among these individuals, in terms of what they are looking for in an online community. Furthermore, Zollo (2004) highlights the fact that even though youths are not a homogenous group of consumers, they comprise an important market segment with many common traits.

With support from previous research, the authors argue that online communities, targeting youths, should reach a consensus on what needs and wants these people seek to satisfy in an online community. By doing so, the community will provide content that the consumers perceive as valuable and useful, which is in line with what Koh et al. (2007) suggest. The authors claim that, for instance, it would be of interest for these online communities to know what young people want to read about, what website features they find important and what other attributes they value.

1.3 Purpose

The purpose of this thesis is to explore what needs and wants youths in Sweden seek to satisfy in online communities. To demonstrate the findings, Ungdomar.se will be evaluated, and given recommendations accordingly.

To fulfil the purpose of this thesis, the following research questions will be answered: • What needs and wants do youths seek to satisfy in online communities?

• How can Ungdomar.se adapt and improve their website with respect to youths’ needs and wants in online communities?

• Is it possible for Ungdomar.se to provide youths with a function that cannot be provided outside of the Internet and if so, what function would that be?

1.4 Contributions

Until now, there is little research within this specific area since consumer behaviour typical-ly relates to commerce settings (Loveland, 2013). Ungdomar.se has not yet undertaken any study to explore their target group. Hence, they believe that it would be valuable to explore the needs and wants of these people in online communities (Jakobsson, 2013). In addition, since the majority of young people in Sweden today are found on the Internet and use online communities (Findahl, 2012), the authors argue that this thesis might serve as a guideline and be helpful for other online communities, with interests in the same target

group. Furthermore, this study will contribute to the academic community, since it opens up for further research on online consumer behaviour in relation to youths’ needs and wants in online communities. Lastly, this thesis demonstrates that consumer behaviour is applicable online in a non-commerce setting.

1.5 Delimitations

This study focuses on people between the ages of 15-19 in Sweden. Convenience sampling has been applied in the quantitative phase of the study, explained in section 4.2.5. Thus, as Fritz and Morgan (2010) state, the authors of this thesis cannot claim that the sample, hence the result, will be representative of the whole population of interest.

2 Pre-understanding of the Topic

This section will give the reader a pre-understanding of the topic in order to facilitate the reading. Key con-cepts will be explained and how they are to be interpreted in this thesis. Furthermore, definitions will be brought up.

2.1 Online consumer behaviour

The term ‘consumer behaviour’ concerns “how individuals, groups, and organizations se-lect, buy, use, and dispose of goods, services, ideas, or experiences to satisfy their needs and desires” (Kotler, 2000, p. 87). Gad (2009) further refers to consumer behaviour as the consumers’ attitudes, intentions, decisions and actions that occur in the marketplace. The authors notice that when the concept of consumer behaviour is applied to online settings, it often relates to how consumers make purchasing decisions in e-commerce contexts. However, as stated by Cho and Park (2001), it is important to remember that in online set-tings, consumers can be considered not only as buyers of goods but also as consumers of information. With support from the Marketing Professor Kate Loveland (2013), the au-thors argue that using a website can be seen as a type of consumption while time and effort can be treated as the payment. An online community, such as Ungdomar.se, does not sell goods or services in exchange for money; instead they put value into consumers’ usage of their online community and the fact that individuals invest their time and effort in the community rather than any other website (Jakobsson, 2013). In this particular context, the authors refer to the concept ‘online consumer behaviour’ as how Internet users select and repeatedly consume the services provided in an online community, in order to fulfil their needs and wants. According to this definition, online communities serve as an e-service, which the Internet users consume at no financial cost. Finally, this thesis refers to users of online communities as consumers in the sense that they consume website content, com-pensating with their time and effort. As far as the authors are concerned, there is no estab-lished definition describing exactly this case.3

2.2 Online community

In many studies, online communities and virtual communities are interchangeable; both can be viewed as social communities taking place on the Internet (Bagozzi & Dholakia, 2002; Bishop, 2007). According to Leimeister, Sidiras and Krcmar (2006), such a communi-ty is “built on a common interest, a common problem, or a common task of its members that is pursued on the basis of implicit and explicit codes of behaviour” (p. 281). The tech-nical platform also helps to create trust among the members, along with a sense of com-munity (Leimeister et al., 2006). In this thesis, the authors will use the definition proposed by Andrews (2002). That is, an online community is a virtual social network, primarily used for communicating common interests, sharing information and solving problems. This communication is supported by computers instead of face-to-face interactions (Andrews,

2002). Furthermore, this kind of community often includes user-generated content and can be described as a form of a user-generated media (UGM), since both are based on a shared interest and common goals among the users (Shao, 2009). Therefore, in this thesis, online communities are also viewed as a form of UGMs.

2.3 Definitions

Blog: Online journal in which a record of thoughts, activities and beliefs are regularly pre-sented (Nationalencyklopedin, 2013a).

BRIS: An organisation working for children’s rights in Sweden. Their main commitment is to support and give feedback to vulnerable children and youths by providing the possibility to contact the organisation regarding any problem (BRIS, 2011a).

E-commerce: Retail of goods, services and information over the Internet (Encyclopædia Britannica, 2013a).

E-service: Providing services over the Internet or any other electronic network (Rust & Kannan, 2002).

Facebook: Website, based on social networking and online communication, mainly through texts and photos (Nationalencyklopedin, 2013b).

Instagram: Social network mobile application that enables people to share photos (Nat-ionalencyklopedin, 2013c).

Online forum: Web application or website that allows Internet users to communicate with each other, although not face-to-face (Laudon & Traver, 2012).

Social network: Website or an application that enables people to communicate, for in-stance by sharing photos and information or posting comments and messages (Oxford University Press, 2013).

Twitter: Service, that enables the user to send out short messages to groups of people as a sort of micro blog (Encyclopædia Britannica, 2013b).

3 Frame of Reference

This section will present the frame of reference, which consists of theories and information of relevance for this thesis. It will serve as a foundation for the design of the investigation as well as for the interpretation and analysis of the findings.

3.1 Internet and Web 2.0

The first website was accessible on the Internet in 1991 and ever since, Internet has rapidly evolved (Wee, 2010). According to Sørensen (2010), the Internet Generation4 has been provided with new possibilities when it comes to learning and communicating. Over the years, Internet has developed into the concept Web 2.0, which can be seen as the second generation of the phenomenon. Web 2.0 deals with Internet as a platform where digital material is gathered. Sørensen (2010) further explains that this has opened up a world where people share things with each other, create things together and communicate through social communities. Thus, Web 2.0 strongly relates to the concept of ‘user-generated content’, which is the content produced by the Internet users themselves. According to BRIS (2013), the new possibilities of communicating can be seen in their dai-ly operations. BRIS reports from the last three years show how there has been a shift when it comes to communication. Today children and youths use Internet as a communication channel to a higher extent than before and they communicate through Internet rather than on telephone (BRIS, 2011a). Table 1 shows how children and youths increasingly choose Internet-based contact mediums over phone calls, when contacting BRIS.

Table 1 - Statistics from BRIS-rapporten (BRIS, 2011b, 2012 & 2013)

3.2 Motivation theory - Needs and wants

The behaviour of human beings is based on motivation, which occurs when a certain need is evoked. This need creates a tension that the individual seeks to reduce (Solomon, 2009). According to Hoyer and MacInnis (2008), motivation is ”an inner state of arousal that pro-vides energy needed to achieve a goal” (p. 45). A motivated consumer is eager to engage in an activity that can help fulfil this goal. As proposed by Solomon (2009), motivation closely relates to needs and wants.

Dermody (2009) proposes that “needs and wants reside within the discipline of motivation and are closely interlinked”. Needs concern “the manifestation of physiological, personal, and/or social motives” while wants are “the means of fulfilling them”. Dermody (2009) further argues that needs and wants within consumer behaviour help to obtain an under-standing of the what, why and how of the decisions that people make, both by themselves and in groups.

According to Kim (2000), people choose to participate in communities in order to fulfil different needs. For an online community to succeed, it is vital to know which these needs are. Whether it regards the launching of a new community or the refining of an existing one, communities should strive to see the community through the eyes of their consumers. When seeking to determine consumers’ needs, Kim (2000) suggests three stages: (1) under-stand your members, (2) make a list of their needs, and (3) prioritise your list. At the first stage, communities should ask questions such as who their members are, whether they are homogenous or not, what interests they have, and whether they belong to any other com-munities. The aim is to gain understanding of who their members are. At the second stage, communities should seek to find out why consumers visit their website, whether they look for something specific and what their community can do to make them satisfied. Further-more, the aim is to find out what content consumers look for. The last stage is about decid-ing on which needs and wants that should be prioritised on the website. That is, what web-site attributes consumers value the most. Communities should think of unique features, which they could offer their members (Kim, 2000).

3.2.1 Maslow’s hierarchy of needs

According to Barnes and Pressey (2011), there is no real consensus regarding how to classi-fy motivation and human needs. However, they argue that the most employed needs con-ceptualisation within the marketing field could be Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, developed in 1943. Solomon (2009) explains how this theory for understanding human motivation identifies five categories of needs: (1) Physiological needs, (2) Safety needs, (3) Love or So-cial needs, (4) Esteem needs, and (5) Self-actualisation needs. According to this theory, in-dividuals have to satisfy their physiological needs, such as air, food, shelter and water, be-fore they gradually can satisfy the other needs. The hierarchy of needs takes the form of a pyramid, which implies that lower needs must be fulfilled first (Solomon, 2009).

Maslow (1943) states that the most dominant physiological need is hunger and this need has to be satisfied before any other need can be fulfilled. An individual who is starving pri-orities eating above everything else – without food the individual will simply die. When physiological needs, such as hunger, sleep, thirst and air, have been satisfied, the individual strives to address the safety needs. In order for someone to feel safe, a predictable and or-derly view of the world is desirable. When becoming adults, individuals learn the repetitive patterns of how the reality runs and thus perceive safety. Hence, in a developed and safe society, an adult will eventually satisfy their safety needs. Maslow (1943) further explains that the next level comprises social needs. At this stage, people seek for belonging and love from other individuals and for affectionate relations. The social need fulfils by both giving

and receiving love. Next stage in the hierarchy comprises the need for esteem, which sists of affiliation, self-respect and high evaluation of oneself. The first type of esteem con-cerns how the individual strives to obtain confidence and confirmation, which in turn leads to esteem in the sense that the individual feels trust in what he or she does, hence obtains a sense of being useful and necessary. The other type of esteem describes how the individual seeks esteem from others, for instance in the form of reputation, prestige and recognition. Finally, when all these level of needs are satisfied, the individual tends to perceive restless-ness, meaning that the last level in the hierarchy of needs is the need for self-actualisation. At this stage, the individual seeks to engage in activities in which he or she has capacity to thrive; “what a man can be, he must be” (Maslow, 1943, p. 382).

Gleitman, Gross and Reisberg (2011) provide an extended version of the pyramid, shown in Figure 1, which includes two more needs: the cognitive need and the aesthetic need. The aesthetic need relates to order and beauty while the cognitive need drives the individual to strive for knowledge and understanding. These needs are placed before the self-actualisation need in the pyramid.

Figure 1 - The hierarchy of needs (Gleitman et al., 2011)

Maslow (1943) states that even though the needs take the form of a pyramid, the hierarchy does not intend to be inflexible. As Maslow (1943) proposes, “most members of our socie-ty who are normal, are partially satisfied in all their basic needs and partially unsatisfied in all their basic needs at the same time” (p. 388). This means that a need must not be fully satisfied before the next need can emerge. In addition, some needs might be considered more important than other needs and the higher up in the hierarchy, the lower the percent-age of satisfaction. This decreasing percentpercent-age of satisfaction would be a more realistic view of the hierarchy (Maslow, 1943).

Kim (2000) suggests that Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, as it first was developed, can be ap-plied to online settings and serve as a helpful tool when designing online communities. By means of the hierarchy, communities can clarify their goals, in order to decide which web-site-features to prioritise. In table 2, Kim (2000) demonstrates how the five needs can take form in both online and offline settings.

Table 2 - Maslow's hierarchy of needs, in online and offline settings (Kim, 2000)

Bishop (2007) proposes that the hierarchical needs theory implies that the reason why some people choose not to participate in an online community is that their physiological or safety needs have not yet been fulfilled. In the same way, people who choose to participate, do so because they seek to meet their higher needs. However, Bishop (2007) questions the idea that individuals’ needs would take the form of a hierarchy, since needs are not mutual-ly exclusive. “It is possible for an individual to be sociable and be creative at the same time and it might not be necessary for them to become secure before they act out social desires” (Bishop, 2007, p. 1882). Therefore, individuals do not necessarily have to feel physiologi-cally satisfied or safe in order to use online communities (Bishop, 2007).

3.2.2 User-generated medias (UGMs)

Today’s Internet users can choose from a wide range of UGMs with different characteris-tics. What all these have in common is that they can refer to as “the new media whose con-tent is made publicly available over the Internet, reflects a certain amount of creative effort, and is created outside of professional routines and practices” (Wunsch-Vincent & Vickery, 2006, cited in Shao, 2009, p. 8).

Katz, Blumler and Gurevitch (1974) proposed that needs can be media-related, indicating that such needs are the underlying motivation of why individuals consume media. These early studies on user and gratification concern the media provided at that time, such as TV, radio and newspaper. However, Shao (2009) argues that these theories from 1974 are somewhat out-dated in relation to today’s modern media, but that they can be revised to fit the modern media context. Consequently, by means of other researchers’ work, Shao

(2009) has provided an extension of these traditional theories. According to this extended theory, people have primarily three motives to visit UGMs: (1) Consuming, (2) Participat-ing, and (3) Producing. These motives can help individuals to fulfil certain needs (Shao, 2009).

Firstly, Bowman and Willis (2003, cited in Shao, 2009) explain that consuming concerns watching or reading the website content. It is also a way of seeking entertainment, for in-stance by browsing through videos on YouTube. This kind of information-search attracts people seeking to create sense and understanding of one self, other people, or the world. Therefore, as concluded by Shao (2009), individuals consume content on UMGs to fulfil their needs of information, entertainment and mood management. Secondly, Chan (2006, cited in Shao, 2009) argues that participating on UGMs implies that the individual actively engages in either user-to-user or user-to-content interactions. User-to-user interactions oc-cur through for instance email, chat rooms or message boards while user-to-content inter-actions occur when users save special website features to their favourites, share content with other users, post comments about the website content, and rate things such as pic-tures and stories. According to Shao (2009), joining an online community that is built around user-generated content can help fulfilling social needs. The interaction among users on such website form a virtual community, where people share interests and create a sense of togetherness. Lastly, producing on UGMs relates to when someone actively produce personal content such as texts and photos on a website. Shao (2009) further explains that posting own produced material on UGMs is highly related to the pursuit of self-expression, which implies that people seek to convey their identity to other people. By consciously choosing what parts to expose to others, it is possible to control this identity. In addition to self-expression, many users strive to reach behavioural goals such as recognition, fame or efficacy. This can refer to the need for self-actualisation (Shao, 2009).

The model developed by Shao (2009), shown in Figure 2, describes the interdependence of the three motives, i.e. consuming, participating and producing. The model illustrates how people tend to go through a certain path when using UGMs. According to Shao (2009), the first stage is where people mostly consume information or entertainment without partici-pating. As they become more acquainted with the UGM, they start participating through user-to-user or user-to-content interaction. This gradually increased involvement further advances at the final stage, which involves producing one’s own material. This results in the creation of one’s personal identity, through self-actualisation and self-expression. The model also demonstrates that UGMs rely on users to produce their own material; without users contributing to the website, it would barely exist. However, it is important to note that not all UGM users follow this specific path. Some people might publish their own work while others only interact. There are also users who remain at the first stage, i.e. only consume the content being provided (Shao, 2009).

Figure 2 - Interdependence of people's consuming, participating, and producing on user-generated media (Shao, 2009)

3.3 Creating a sustainable online community

It has been proposed by Kim (2000) that a successful and sustainable online community may be characterised by a number of timeless design strategies. These strategies may be useful both in the planning process of a new community but also for those who are already running a community, in order to develop and improve the website, to better meet the needs of its members (Kim, 2000). Seven of these strategies are explained below.

The first strategy relates to the community’s purpose or vision. This should be clearly artic-ulated and implemented in the overall website design. It should also permeate the website features, its technology and prevailing policies (Kim, 2000).

The second strategy concerns building a meaningful gathering place, for instance in the form of discussion forums or chat rooms. These gathering places should strengthen the purpose or the vision, to serve the members’ needs. By allowing members to contribute to the development of the website, the growth of the community may be enhanced (Kim, 2000).

The third strategy involves creating member profiles that include some kind of personal in-formation. This can make the website more vivid. By giving the members a chance to cre-ate their own identity, trust can be enhanced and social relationships encouraged (Kim, 2000).

The fourth strategy stresses the importance of recognising that members may have differ-ent roles, depending on how long they have been involved in the community as well as on their level of involvement. Kim (2000) suggests five different roles and how to treat them accordingly: ‘welcome your Visitors’, ‘instruct your Novices’, ‘reward your Regulars’, ‘em-power your Leaders’ and ‘honour your Elders’. For instance, for Visitors to feel welcome, a certain website feature may help them to find out what the community is all about and what the benefits of a membership are. Novices are people who have recently become members, hence may need some guidelines regarding how to use the website. Regulars are people who have been members for a long time and have a higher level of involvement in the community. Kim (2000) further describes these people as “the lifeblood of your munity, both socially and economically”. To ensure that Regulars stay involved, the com-munity may offer them certain opportunities and challenges. Furthermore, Leaders can be empowered with respect to the needs of the community. The leadership role can for in-stance involve hosting conversations, making sure that discussion forums stay focused and vivid, or moderating the overall content of the website, ensuring that inappropriate content or behaviour is removed or reported. Finally, Elders are long-time members who have seen the website evolve over time and who are continuously participating and interacting in the community. Many times, these serve as role models, to whom Novices can turn for advice and guidance (Kim, 2000).

The fifth strategy focuses on raising the Leaders of the community. Whether official or un-official, the Leaders are members who assist the community to implement its vision, serv-ing as “the fuel in your engine”. If their efforts are recognised, there is a greater chance that they will remain involved and share content on the website (Kim, 2000). This is further stressed by Koh et al. (2007), who argue that involved leaders are necessary in order to fos-ter members’ engagement in activities on the website. Such engagement can take the form of posting one’s own material or viewing what has already been posted on the website. The sixth strategy relates to the etiquette prevailing on the website, which can be referred to as the rules to live by. That is, what behaviour that is agreed upon and considered ap-propriate. This kind of regulation is important in order to foster a sense of safety on the website (Kim, 2000).

The seventh strategy involves promoting events, in both online and offline settings. These could be in the form of arrangements, where the members get together and interact, or competitions and challenges on the website. This strategy aims to define the community, i.e. further clarify its vision or purpose (Kim, 2000). Moreover, Koh et al. (2007) state that there is a direct linkage between offline events and the level of online involvement. Kim (2000) similarly suggests that offline interactions may reinforce a sense of solidarity and to-getherness, which in turn may motivate people to more actively participate on the website, i.e. not only view already existing community content.

4 Method and Methodology

This section will first present and discuss the choice of methodology whereupon the choice of method will be defined. Justifications and explanations for the chosen method will be provided.

4.1 Methodology

Methodology relates to the principals of philosophy and logic nature, which different methods are based upon (Svenning, 2003). The concept is also concerned with the strategy, plan, design or process that underpin the choice of method (Crotty, 1998).

4.1.1 Research philosophy

According to Saunders, Lewis and Thornhill (2012), the adopted research philosophy com-prises ”your assumptions about the way in which you view the world” (p. 128). These un-derlying assumptions will serve as a foundation for the methods the researchers choose as part of the research strategy. There are several philosophies, also referred to as paradigms, to consider when conducting a research. Under these paradigms, there are different posi-tions out of which positivism and interpretivism are commonly used. Positivism concerns observable realities and seeks to establish generalisations by collecting data. Interpretivism concerns the differences between humans in their role as social actors. A third position, pragmatism, is devoted to neither positivism nor interpretivism. Pragmatism considers the-se two positions as opposing concepts, and instead advocates mixing them. This position supports both quantitative and qualitative research, and the nature of the research topic will determine how to use these two methods. As further stated by Saunders et al. (2012), ac-cording to a pragmatist, “there are many different ways of interpreting the world and un-dertaking research, that no single point of view can ever give the entire picture and that there may be multiple realities” (p. 130).

The pragmatic position underlies this research, thus directs the methodological choices. The reason why the authors consider this philosophical position the best alternative is that the nature of the research questions requires a mix of both quantitative and qualitative data. Furthermore, the authors do not claim that the findings will show a definite reality, since the reality may look different, depending on how researchers conduct the research. Thus, the pragmatic position is well-suited for this study.

4.1.2 Research purpose

There are three common classifications regarding the purpose of a study: explorative, ex-planatory and descriptive. Firstly, explorative studies aim to gain insights to a topic and clarify understanding of a problem (Saunders et al., 2012). In addition, in an explorative study, the research problem tends to be badly understood (Ghauri & Grønhaug, 2005). Secondly, according to Saunders et al. (2012), explanatory studies intend to identify cause and effects relationships between variables, by making studies of problems or situations. Finally, descriptive studies seek to give an accurate picture of a phenomenon and can serve as complements to either an explorative or an explanatory study. This kind of study enables

researchers to go further and draw conclusions from the data described. Using a descriptive design tends to be appropriate when researchers have knowledge about the specific topic, prior to the data collection (Saunders et al., 2012).

In line with the purpose of this study, the authors consider this partly an explorative study and partly a descriptive study. The reason is that the aim is to obtain understanding of youths’ needs and wants in online communities as well as draw conclusions from a more extensive amount of data in order to give an as accurate picture of the reality as possible. 4.1.3 Research approach

Mixed method design

When conducting a study, there are three different methodological approaches: qualitative, quantitative or a combination of both (Darlington & Scott, 2002). According to Zikmund (2000), a qualitative approach is rather subjective and focuses on words and observations while a quantitative approach focuses on numbers and exact measurements. Saunders et al. (2012) refer to a combination of both approaches as a mixed method. Creswell and Plano Clark (2007, cited in Saunders et al., 2012), state that in this kind of study, researchers may use quantitative and qualitative research in either an equal or an unequal amount. Accord-ing to Morse and Niehaus (2009), the reason why a mixed method design is used, is that some phenomena cannot be fully described by using only one method. In such situations, by using both a qualitative and a quantitative approach, the study can become more com-plete and the research outcome may be improved.

A mixed method design is used to fulfil the purpose of this study. The reason is that the authors believe using one single method will be insufficient in order to answer the research questions, since they want to collect data from a sizeable population as well as obtain more qualitative information. The qualitative and the quantitative method have equal weight. Abductive approach

According to Saunders et al. (2012) there are three research approaches to choose from: inductive, deductive and abductive approach. When deciding on which research approach to use, it is important to look at the nature of the research topic. If conducting the research within a field that is new and thus not very explored, the inductive approach is suitable. This approach goes from data to theory, and aim to explore data. Conversely, when there is much literature on the topic, which enables researchers to establish hypotheses and frame-works from which to proceed, the deductive approach may be more appropriate. This ap-proach goes rather from theory to data. Finally, using a combination of the two apap-proaches composes the abductive approach. Such approach is neither moving from data to theory, nor from theory to data; it is moving back and forth. By using this approach, phenomena are explored by means of data, themes and patterns are identified whereupon new theories are created or existing ones are modified. These theories are subsequently tested, often through an additional collection of data. If there is much literature within one context, but less in the particular context in which the research is conducted, an abductive approach is appropriate (Saunders et al., 2012). Furthermore, according to Alvesson and Sköldberg (2007), an abductive approach goes deeper than the other two approaches, in the sense that

it seeks to obtain an understanding of underlying patterns of a phenomenon. Researchers alternate between theory and data, whereupon they reinterpret these in light of each other. To best fulfil the purpose, this study uses an abductive research approach. The research originates from already existing theories regarding consumer behaviour and online com-munities. These theories serve as the foundation for the questionnaire, which is in line with a deductive approach. The interviews are semi-structured and originate in data, from which the authors aim to seek common patterns and understanding, which is in line with an in-ductive approach. Finally, by means of existing theories, the authors analyse the findings al-together in order to answer the research questions. This combination of the approaches supports an abductive approach. Furthermore, the authors go neither from theory to data nor from data to theory, they rather move back and forth. This is in line with the abductive approach as defined by Saunders et al. (2012). Hence, the authors claim that the abductive approach suits this particular thesis. With regard to what Alvesson and Sköldberg (2007) state, the authors argue that an abductive approach will provide the thesis with a deeper understanding than if solely using an inductive or a deductive approach.

4.2 Method

The method comprises the techniques or procedures that the researchers use in the collec-tion and analysis of data, to answer a research quescollec-tion or to test a hypothesis (Crotty, 1998).

4.2.1 Case study

Case studies are conducted when researchers aim to investigate a phenomenon within its natural environment. This is usually made by collecting data from multiple sources. Single case studies can be used when researchers want to investigate a typical example (Saunders et al., 2012). A single case study composes this thesis and as explained in section 1.1, the authors consider Ungdomar.se suitable.

4.2.2 Target population

In Sweden, an ethical industry standard states that people under the age of 15 should not participate in surveys without the consent from their parents or guardians (SMIF – Sveriges Marknadsundersökningsföretag, 2013). Given the time frame, the authors consider such acquisition of consent too time demanding and therefore, they decided to draw a bottom line at the age of 15. For practical reasons, the authors have decided to draw an upper line at the age of 19. These people are found in schools around Sweden, while people older than 19 years are no longer obliged to compulsory school attendance. Hence, they are not gathered at one common location and thus more difficult to reach.

4.2.3 Research strategy

The research strategy is the general orientation in which the research is conducted (Bryman & Bell, 2007). According to Saunders et al. (2012), research strategies are not mutually ex-clusive, which implies that several strategies can be used. As stated by Zikmund (2000), the research design can be seen as a master plan, specifying the methods and procedures that are to be used in order to collect and analyse information. When choosing between the dif-ferent strategies, the research questions should serve as a guide; a good research strategy is one that will enable researchers to give answers to these (Zikmund, 2000).

In this study, the authors conduct a questionnaire and three semi-structured interviews, i.e. a mixed method design. The questionnaire is of both quantitative and qualitative nature, in the sense that qualitative data is embedded within the quantitative data. This questionnaire primarily serves the descriptive part of this study, aiming to respondents within the popula-tion of interest. The interviews primarily serve the explorative part of this study. One inter-view is held with two people working closely to youths. As Kotler (2000) argues, under-standing how consumers behave is not simple, since they may not be conscious of their underlying motivations. Thus, the authors believe that two persons working at the Youth Centre Brunnen, located in central Jönköping, will provide insight to the needs of young people, which they may not be fully aware about themselves. Brunnen will also provide in-formation about common interests and concerns among the investigated population and whom they turn to with these concerns. Furthermore, to answer the research questions, the authors consider it important to acquire wide knowledge of what Ungdomar.se, as an online community, currently provides. The authors believe that interviews with two key persons within the company, the CEO and the Web Administrator, will provide this in-formation together with a review of the website.

This strategy results in a combination of quantitative and qualitative findings, described in figure 3. The left-hand box represents the questionnaire, and the right-hand box represents the interviews and the findings from Ungdomar.se. The authors consider these two strate-gies the best alternatives, given the time frame and the resources. Consequently, the au-thors use a concurrent embedded design, which according to Saunders et al. (2012) is when the collection of data is embedded within the collection of the other. In this study, this im-plies that some questions in the questionnaire require a qualitative response.

4.2.4 Data collection

Data can be either primary or secondary. Researchers themselves collect primary data while secondary data derives from knowledge found by previous researchers. Preferably, re-searchers should carefully examine both types of information sources (Eriksson & Wei-dersheim, 2011). Zikmund (2000) explains that the main advantage of using secondary data is that it saves money and time. On the contrary, the disadvantage is that the data is not de-signed specifically for the researchers’ purpose.

Primary data

Surveys are the most commonly used method for collecting primary data (Zikmund, 2000; Sekaran, 2003). As stated by Saunders et al. (2012), surveys are common in both explorato-ry and descriptive research. According to Bexplorato-ryman and Bell (2007), surveys are comprised by a cross-sectional design, in which data are collected at a single point in time, primarily by using questionnaires or conducting several structured interviews. Researchers seek to dis-tinguish patterns, identify characteristics of a specific group and to measure attitudes (Bry-man & Bell, 2007). Surveys are normally descriptive, but can also provide explorative in-sights or causal explanations, depending on the design (Zikmund, 2000).

Since the authors aim to collect an extensive amount of primary data to analyse, they con-sider questionnaire the best alternative, given the time and resources at hand. Additional primary data is obtained through the semi-structured interviews and the review of the web-site Ungdomar.se. According to Saunders et al. (2012), semi-structured interviews are suit-able when researchers aim to collect qualitative data. In such interview, the interviewer has a list of what subjects to cover as well as predetermined questions. The researchers may omit predetermined questions and ask additional questions, depending on the specific con-text (Saunders et al., 2012).

Secondary data

According to Zikmund (2000), secondary data enables researchers to ”build on past re-search – a body of business knowledge” (p. 125). In this study, the authors use literature found in the library of Jönköping’s University and online databases. The focus is primarily on peer-reviewed articles that are highly cited, due to their high reliability and quality. Dur-ing the search process, the authors face difficulties as many articles and books are too ex-pensive to access. Therefore, there is a risk that the authors might miss some information that could be useful for this study.

4.2.5 Sampling Questionnaire

According to Fritz and Morgan (2010), sampling concerns investigation of a portion of a population, in order to make statements about this certain population. How to select a sample is an essential part when conducting research. There are some evident advantages of sampling instead of exploring the whole population; these include lower costs, higher speed and convenience (Fritz & Morgan, 2010). However, it is important to remember that

a sample is only a model of the reality. This in turn can lead to sampling error, which is a measure of how far the model may be from the reality (Trobia, 2008).

Fritz and Morgan (2010) explain four steps in the sampling process. (1) Identify the popu-lation of interest, i.e. the target popupopu-lation. (2) Identify a portion of this target popupopu-lation. This is the sampling frame, based on readily available participants. (3) Create a smaller sample out of this accessible population. (4) Define the actual sample. This contains the in-dividuals who decide to participate in the study, hence whose data is analysed (Fritz & Morgan, 2010).

In this study, the population of interest is people in the ages between 15-19, living in Swe-den. The portion of this population lives in Jönköping and Herrljunga. Selected classes on schools located in Jönköping and Herrljunga constitute the sampling frame. From this, the authors obtain the sample of eight classes, i.e. two classes for every age investigated, with the aim to reach at least 150 students. According to Fritz and Morgan (2010), when decid-ing the sample size, researchers tend to base their decision on practical matters, such as available resources and amount of time. Hence, there is no right answer to how large a sample should be in order to be representative of the whole population. In addition, the re-searchers should consider the anticipated response rate (Fritz & Morgan, 2010).

Nonprobability sampling

As stated by Fritz and Morgan (2010), there are two broad categories of sampling methods to choose from: probability sampling and nonprobability sampling. In probability sampling, researchers must have access to all individuals in the accessible population and they should have an equal chance of being selected. In cases when this is neither practical nor feasible, the researchers can use nonprobability sampling (Fritz & Morgan, 2010). As an example, Baker (2002) explains that in much student research, probabilistic methods may be unreal-istic, since resources are limited. In this study, the authors use non-probability sampling, with respect to the resources that they have at hand.

According to Battaglia (2008), there are primarily three categories of nonprobability sam-pling methods: quota samsam-pling, purposive samsam-pling and convenience samsam-pling. In quota sampling, researchers set a target number of respondents, in order to fill predetermined quotas. Purposive sampling concerns selecting a sample based on the characteristics that are important for the sample to represent the whole population. In convenience sampling, the main selection criterion concerns how easy it is to obtain a sample. For instance, re-searchers consider the geographic distribution of the sample, how easy it will be to obtain data from the selected elements and how costly it will be to locate the elements of the pop-ulation of interest (Battaglia, 2008). With regard to the limited resources for this study, the authors use convenience sampling. In an attempt to reach different types of individuals, the authors hand out the questionnaire at the upper secondary school Kunskapskällan in Herrljunga, which offers different programmes. In order to reach ninth-graders, i.e. youths in the age of fifteen, the authors hand out the questionnaire at Junedalsskolan in Jönkö-ping.

Interviews

According to Marshall (1996), when conducting qualitative research, sampling is not as im-portant as in quantitative research. The reason is that researchers do not seek to generalise the results but rather develop an understanding of complex problems regarding human be-haviour. Hence, some individuals are considered to provide better insight and understand-ing for such research than others (Marshall, 1996). Consequently, in the qualitative part of this study, the authors select informants based on their knowledge and expertise with re-gard to young people.

4.2.6 Time horizon

When deciding on the time frame for a study, there are primarily two alternatives; longitu-dinal and cross-sectional research. Longitulongitu-dinal studies observe changes and development over a given period, while cross-sectional research studies an event or a phenomenon at a particular point in time (Saunders et al., 2012). Since this research is time constrained and the authors do not aim to observe changes or development, the authors conduct a cross-sectional study.

4.2.7 Quality of the study

According to Saunders et al. (2012), to optimise the quality of a study, researchers should ensure reliability and validity. Reliability relates to consistency, i.e. whether the means of collecting data would give the same result if other researchers conducted the same study. It also concerns to which extent the researchers show transparency in how they have inter-preted the data. Validity concerns whether the chosen method of collecting data correctly measures what the researchers were intended to investigate (Saunders et al., 2012). To op-timise the reliability of this study, the authors strive to be as explicit and transparent as pos-sible throughout the thesis, in order to enable other researchers to conduct the same study. Validity is faced primarily by carefully designing the questionnaire. For the interviews, in order to ensure trustworthiness, the authors take different forms of bias into consideration. Questionnaire

The questionnaire, originally in Swedish, and translated into English, can be found in ap-pendix 1 and 2, respectively.

Conducting questionnaires has both advantages and disadvantages; it is an inexpensive way to collect a large amount of data from a substantial population (Saunders et al., 2012; Gill-ham, 2007). Moreover, it is a quick and efficient way to assess information (Crotty, 1998; Gillham, 2007). Gillham (2007) further states advantages such as no interviewer bias, straightforward data to analyse, and anonymity of the respondents. However, disadvantages include generally low response rate, problems controlling the quality of the data, and the fact that possible misunderstandings cannot be corrected (Gillham, 2007). The authors are aware about these disadvantages and find it important to highlight that these factors may affect the result.

re-searchers to optimise the validity of the questions and to see whether the data will be relia-ble. Furthermore, such a small-scale test can ensure that the respondents do not have any problems understanding the questions (Saunders et al., 2012). To see whether there are any questions that need to be clarified or rephrased in this study, the authors conduct a pilot test with one person from every age investigated. In addition, this can ensure that the ques-tions are interpreted in the way they are intended to.

Translating empirical data into theory is acknowledged as a difficult task. Researchers have to consider that various factors can affect the investigation (Svenning, 2003). In order to minimise the risk of bias, it is vital to carefully think the research design through (Sekaran, 2003). To ensure validity, it is important to consider how to formulate the questions, how to measure the answers and how the questionnaire should be organised overall (Sekaran, 2003; Saunders et al., 2012).

When designing the questionnaire, the authors considered these four recommendations provided by Zikmund (2000):

• What questions should be asked? • How should the questions be phrased?

• How should the questionnaire layout be designed? • In which order should the questions be organised?

A questionnaire should only include questions relevant to what the questionnaire intends to investigate. There might be numerous questions that researchers want to ask, but they have to decide upon what they have to ask (Gillham, 2007). In this study, the authors only in-clude questions that can help answering the research questions. The questions are carefully selected and refined, in order for the questionnaire to be relevant.

Zikmund (2000) recommends using questions that are specific and formulated in a simple language, with a layout that is neat and easy to follow. Correspondingly, the authors con-ducting this study strive to create straightforward questions formulated in a conversational language, to avoid ambiguity and complexity. In addition, since the respondents are Swe-dish students, the questions are in SweSwe-dish. Furthermore, the authors use a plain question-naire layout in which the respondents are introduced to the study in the beginning of the questionnaire. As explained by Gillham (2007), if the respondents understand the research-ers’ purpose, they are more likely to put their effort into providing appropriate answers. Questions that might be perceived as sensitive should be asked in the end of the question-naire, as this can make the respondents might feel more comfortable in answering them (Zikmund, 2000). In this study’s questionnaire, the order of the questions is intended to first obtain a general understanding of the respondents (question 1-4). These questions aim to obtain data about age, Internet usage and interests, and to give the respondent a com-fortable start. The remaining questions (question 5-8) aim to more specifically obtain an-swers regarding what needs and wants online communities can address. Finally, the last question (question 9) might be perceived as more sensitive.

According to Bryman and Bell (2007), researchers formulate questions in either an open or a closed format. Open questions allow the respondent to answer freely while closed ques-tions give the respondent a set of fixed alternatives (Bryman & Bell, 2007). The longer the questionnaire, the fewer people may be likely to respond (Van Selm and Jankowski, 2006; Gillham, 2007). To reduce the risk of a low response rate, the authors in this study use mainly questions with fixed alternatives, together with open questions. According to Gill-ham (2007), fixed alternatives are easier to answer and take less time. Furthermore, the questionnaire in this study gives the respondents the opportunity to comment or come up with their own answer. Thereby, the authors want to ensure that they do not exclude other possible alternatives than those provided. Moreover, when providing multiple alternatives, the respondents can choose more than one, but three at most. The authors believe that such limitation may require them to deliberate upon their answers, hence prioritise which answers they perceive as most correct. Finally, the authors categorise the fixed alternatives with regard to the theories provided by Maslow (1943), Gleitman et al. (2011), Shao (2009), and Kim (2000). This is further explained in appendix 3.

Since the questionnaire contains qualitative elements such as open questions, and the pos-sibility for the respondents to provide their own answers, the authors do not consider it appropriate for this study to use statistical measurements such as analysis of variance, standard deviation and confidence interval. Instead, bar charts accompanied by clarifying comments will demonstrate the results in an explicit manner. Furthermore, as stated by Trobia (2008), it is not possible to determine the sampling error, since the study uses nonprobability sampling.

Interviews

Saunders et al. (2012) state that when conducting semi-structured interviews, researchers should consider different forms of bias, such as interviewer bias and interviewee or sponse bias. Interviewer bias occurs if the interviewer may have an impact on what the re-spondent answers, for instance by having a certain tone or giving specific comments. Inter-viewee and response bias are linked to interviewer bias and may occur as a result of how the respondent perceives the interviewer (Saunders et al., 2012).

Since the intention with the interview conducted at Brunnen differs from the intentions with those interviews conducted with Ungdomar.se, the authors do not have to consider is-sues such as using the same tone of voice and non-verbal behaviour for every interview. Regarding the interviews at Brunnen, the authors interview two persons at the same time. Therefore, the authors strive to give them the same possibility to tell their opinion. To min-imise the risk for interviewer and interviewee bias, the authors avoid leading questions. Furthermore, all the interviews are recorded, which enables the authors to go through the data several times, hence minimise the risk for misinterpretations. According to Saunders et al. (2012), the result of semi-structured interviews is not generalisable to the whole popula-tion. Thus, the authors of this study do not claim that the result from the interviews can be generalised. Finally, to further increase the trustworthiness of the interviews, these are held in Swedish, which is the mother tongue of the interviewees and the authors. The interview questions can be found in appendix 4 and 5.

4.2.8 Summary of the method

This is partly an explorative and partly a descriptive study, which takes the stance of prag-matism. An abductive approach is used together with a mixed method design. In order to collect primary data, a questionnaire is handed out to the investigated population by using convenience sampling. This primarily serves the descriptive part of the study and has a concurrent embedded design, in the sense that qualitative data is embedded within the quantitative data. Furthermore, semi-structured interviews are conducted with the Youth Centre Brunnen and with Ungdomar.se, which provide further primary data. The inter-views primarily serve the explorative part and are qualitative in their nature. Information on the website Ungdomar.se provides further information about the company. The secondary data is collected from books in the library of Jönköping's University and through academic articles provided in online databases. Finally, the study is cross-sectional.

4.2.9 Discussion on the method

In most literature regarding the concept ‘online consumer behaviour’, the authors note that studies primarily concern how consumers behave in commerce settings online. As men-tioned previously, in this particular context, the concept of consumer behaviour can relate to consumers who spend their time and effort rather than their money. When reading arti-cles referring to consumers as purchasers, the authors interpret this information in light of Cho and Park’s (2001) statement; in online settings, consumers can be seen as consumers of information and not only as purchasers. The authors regard this the best option, due to the limited amount of previous research and since they consider much of the information applicable to non-commerce settings as well. When discussing how consumers behave on the Internet in this particular context, the thesis consistently refers to online consumer be-haviour as explained in section 2.1.

It is important to note that other methods could have been suitable for this study. As Saunders et al. (2012) state, focus groups and depth interviews yield more qualitative in-formation and deeper understanding of the problem. The authors considered this, but since some respondents might perceive certain questions as intimidating and sensitive, they would be less likely to discuss these in focus groups or in interviews. Therefore, the authors still consider using a questionnaire the best alternative, as focus groups and interviews might have limited the respondents’ ability to give their honest opinion.

In the beginning of this study, the authors considered using an online questionnaire. In or-der to reach as many people in the target population as possible, the questionnaire would have been linked from the website Ungdomar.se. However, an online survey brought some problems that could not be overlooked. For instance, it would not be possible to establish a proper sampling frame, since the authors are not able to recognise the accessible popula-tion. Furthermore, it would have been difficult to calculate a response rate, since it would not be possible to determine how many people in the target population that had seen the questionnaire and chosen not to participate. In addition, it would not have been possible to control whether the respondents actually were in the ages between 15-19, since age is easy to fake on the Internet. Finally, linking the questionnaire on Ungdomar.se could result in

bias, since the result would only reflect users of the community. Through the actual choice of method, the authors can avoid these deficiencies. Furthermore, in order to ensure a more representative sample, the authors did also consider random sampling. However, due to the limited resources for this study, such sampling is not feasible. It might be argued that random sampling could have been used on the schools in Jönköping and Herrljunga. How-ever, such method could have generated a sample comprised by individuals representing a narrow range of programmes. Therefore, the authors do not consider this the best alterna-tive.

5 Empirical Findings

This section will first present the empirical data obtained from the questionnaire. In order for the reader to get a clear picture of the quantitative findings, bar charts and comments will be provided to each question. Thereafter, a summary from the interview conducted with professionals at Brunnen will follow. Finally, a summarised version of the interviews conducted with contacts at Ungdomar.se, as well as the website review will be provided.

5.1 Findings from the questionnaire

The questionnaire was handed out at Kunskapskällan in Herrljunga between the 8th and 9th of April and at Junedalskolan in Jönköping the 9th of April. As mentioned previously, the aim was a sample size of 150 students. The actual sample size was 170 students, with 149 responses. This yields a response rate of 87.6 %. The reason why not all students respond-ed was that some were missing in class or providrespond-ed incomplete questionnaires. Question number 5, 6, 7 and 8 allowed the respondents to choose more than one alternative. There-fore, the number of respondents on these questions exceeds 149. The questionnaire, in Swedish and translated into English, are found in appendix 1 and 2, respectively.

1. How old are you?

A majority of the respondents are 17 years old while there are fewest respondents in the ages of 15 and 19. The reason for this is that the other ages, i.e. 16, 17 and 18, can be found in two grades, depending on what time of the year the student was born. However, the analysis will discuss the population as a whole and avoid focusing on age. Therefore, this information intends to present an idea of the age distribution among the respondents.

2. How often do you use Internet?

The findings show that 96% of the respondents use Internet on a daily basis while 4% an-swer that they use Internet 3-6 times a week. None of the respondents anan-swer that they use Internet less often than that.

3. Do you visit any online communities?

The findings show that 93% of the respondents visit some kind of online community, whereas 7% do not.

4. What is your primary interest?

This open question asks the respondents to give their own answer. Thus, to be able to pre-sent the answers in a comprehensive manner, they are compiled into appropriate catego-ries. The primary interest of the respondents is sport/exercise. This involves sports such as dancing, horse riding and ice hockey. The most common sport however, is football, which 22 of the respondents have chosen as their primary interest. In addition, many respondents answer ‘working out’, which is categorised as exercise. Other common interests are spend-ing time with friends, watchspend-ing TV and films, readspend-ing books and listenspend-ing to music. Six re-spondents consider their primary interest to be some kind of social media, for instance Twitter, Instagram and Facebook. Furthermore, fashion and work are brought up three times each. Examples of other interests being mentioned, which only occur once, are pho-tography, science and food.

5. What would you most preferably like to read about in an online community?

The most popular answer among the respondents is that they would like to read about physical health. Nearly 50% of the respondents put this as one of their answers. Thereafter, the following five topics are equally popular: love and sex, inspiration, relationships,