The Design and Evaluation of

Ambient Displays in a Hospital Environment

ByDorien Koelemeijer

Thesis Project II

Interaction Design Master K3, Malmö University, Sweden

The Design and Evaluation of

Ambient Displays in a Hospital Environment

Date of examination: 31st of May, 2016

Dorien Koelemeijer Thesis Project II

Master of Science in Interaction Design K3, Malmö University, Sweden

Supervisor: Anne-‐Marie Skriver Hansen Examiner: Henrik Svarrer Larsen

Abstract

Hospital environments are ranked as one of the most stressful contemporary work environments for their employees, and this especially concerns nurses (Nejati et al. 2016). One of the core problems comprises the notion that the current technology adopted in hospitals does not support the mobile nature of medical work and the complex work environment, in which people and information are distributed (Bardram 2003). The employment of inadequate technology and the strenuous access to information results in a decrease in efficiency regarding the fulfilment of medical tasks, and puts a strain on the attention of the medical personnel. This thesis proposes a solution to the

aforementioned problems through the design of ambient displays, that inform the medical

personnel with the health statuses of patients whilst requiring minimal allocation of attention. The ambient displays concede a hierarchy of information, where the most essential information encompasses an overview of patients’ vital signs. Data regarding the vital signs are measured by biometric sensors and are embodied by shape-‐changing interfaces, of which the ambient displays consist. User-‐authentication permits the medical personnel to access a deeper layer within the hierarchy of information, entailing clinical data such as patient EMRs, after gesture-‐based interaction with the ambient display. The additional clinical information is retrieved on the user’s PDA, and can subsequently be viewed in more detail, or modified at any place within the hospital.

In this thesis, prototypes of shape-‐changing interfaces were designed and evaluated in a hospital environment. The evaluation was focused on the interaction design and user-‐experience of the shape-‐changing interface, the capabilities of the ambient displays to inform users through peripheral awareness, as well as the remote communication between patient and healthcare professional through biometric data. The evaluations indicated that the required attention allocated for the acquisition of information from the shape-‐changing interface was minimal. The interaction with the ambient display, as well as with the PDA when accessing additional clinical data, was deemed intuitive, yet comprised a short learning curve. Furthermore, the evaluations in situ pointed out that for optimised communication through the ambient displays, an overview of the health statuses of approximately eight patients should be displayed, and placed in the corridors of the hospital ward.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my gratitude to Henrik Elg, head of the department of Internal Medicine section 5 at Skånes Universitetssjukhus Malmö, and the nurses at this department for the time and effort they dedicated to establish an effective collaboration. It is by virtue of their enthusiasm and interest during the field research and evaluation sessions, that it was a pleasure to work on this thesis project. In addition, I would like to thank my supervisor, Anne-‐Marie Skriver Hansen, for her assistance and the valuable insights given during the course of this thesis project.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction 6 1.1 Research outline 61.1.1 Key audiences 8

1.1.2 Collaboration 8

2. Methodology 9 2.1 Methods 9

2.1.1 Field research 9

2.1.2 Literature-‐based research 10

2.1.3 User evaluation 10

3. Clinic of Internal Medicine 12

3.1 Internal Medicine 12

3.2 Field research 12

3.2.1 Setting 12

3.2.2 Study design 12

3.2.3 Findings 13

4. Theoretical framework 15

4.1 Ubiquitous Computing versus the Internet of Things 15

4.2 Ubiquitous technologies in hospital environments 15

4.2.1 The Electronic Medical Record 16

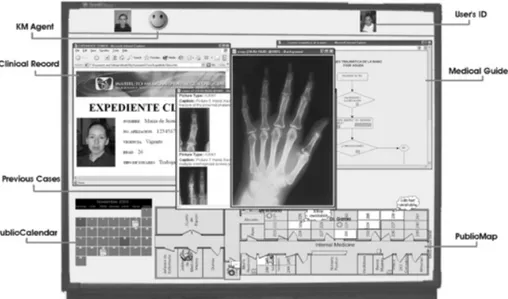

4.2.2 Ubiquitous computing and Ambient Intelligence 16

4.2.3 Guidelines for the creation of ambient displays in hospital environments 18

4.2.4 Body Area Networks 19

4.3 Perception, attention and memory 20

4.3.1 Perception and memory 20

4.3.2 Peripheral attention 21

4.4 Calm technology and unattended technology 22

4.4.1 Visually perceptive features supporting peripheral vision 22

4.4.2 Guidelines for calm and unattended technology for hospital use 22

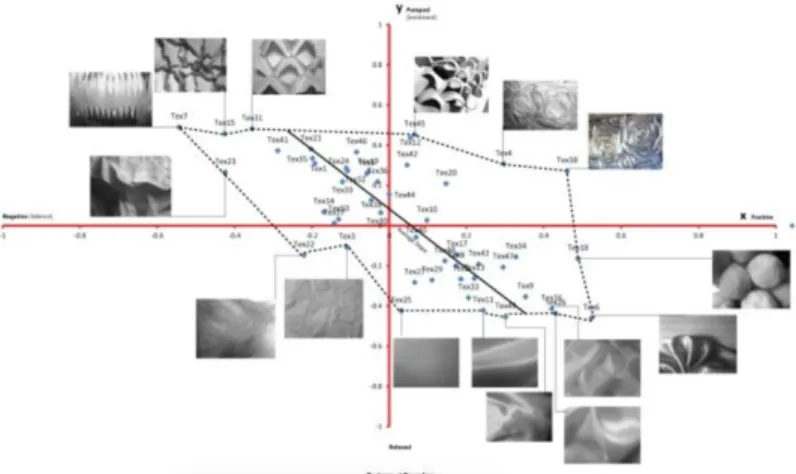

4.5 Natural aesthetics in hospitals 23

5. Related work 24

5.1 SnowGlobe 24

5.2 Textile Mirror 25

5.3 Ambient lighting display through biofeedback 26

6. Designing the ambient display 28

6.1 The concept 28

6.1.1 Hierarchy of medical information 31

6.1.2 Aesthetics and materiality 32

6.1.3 Technical specifications 33

6.1.4 Common Information Space 34

6.1.5 Encryption of public data 34

6.1.6 Metadata 34

6.3 Evaluation I 36

6.3.1 Dual-‐task experiment 36

6.3.2 Results 37

6.3.3 Reflection 38

6.4 Prototyping II 39

6.5 Evaluation II 39

6.5.1 Experience prototyping with tangible prototypes 39

6.5.2 Results 39

6.5.3 Reflection 40

6.6 Prototyping III 41

6.7 Evaluation III 42

6.7.1 Evaluating the interaction with the ambient display and hierarchy of medical

information 42

6.7.2 Results 43

6.7.3 Reflection 44

6.8 Prototyping IV 44

6.9 Evaluation IV 45

6.9.1 Evaluating the semi hi-‐fi prototype 45

6.9.2 Results 45

6.9.3 Reflection 46

7. Discussion and conclusion 47

7.1 Discussion 47

7.1.1 Overall evaluation of the shape-‐changing interface 47

7.1.2 Results in relation to theory 48

7.1.3 Limitations 49

7.2 Conclusion 51

7.2.1 Knowledge contributions 52

7.2.2 Future directions 52

References 53

List of Figures 58

Appendices 60

Appendix A: Interview with the head of the department of Internal Medicine 60

Appendix B: Scenario of the ambient display in use 62

Appendix C: Overview of additional clinical information 63

Appendix D: The dual-‐task experiment 64

Appendix E: In-‐depth description of dual-‐task experiments I, II and III 65

Experiment I 65

Experiment II 65

Experiment III 65

Appendix F: Results of the dual-‐task experiment 66

Experiment I 66

Experiment II 66

Experiment III 68

Overall results and performance 70

1.

Introduction

1.1 Research outline

Healthcare facilities are ranked as one of the most stressful contemporary work environments for their employees, and this particularly concerns nurses (Nejati et al. 2016). One of the core problems comprises the notion that current technology adopted in hospitals does not support the mobile nature of medical work and the complex work environment, in which information is distributed and the medical personnel is required to carry out tasks at scattered locations within the hospital (Favela et al. 2004). Due to this high mobility, it is relatively difficult for medical personnel to consistently be aware of the health status of the patients they are responsible for (Tentori et al. 2009). Furthermore, the employment of inadequate technology and the strenuous access to information results in a decrease of efficiency regarding the fulfilment of medical tasks, and puts a strain on the attention of the medical personnel. Therefore, this thesis aims to answer the following research question: ‘How can ambient displays increase the efficiency of medical work conducted in a hospital setting by providing healthcare professionals with medical information while requiring minimal allocation of attention?’

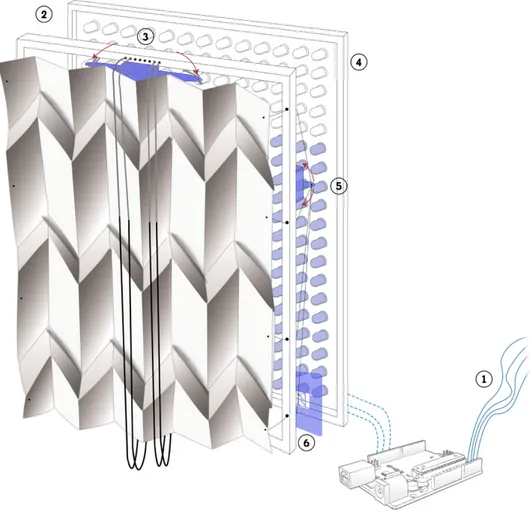

As an answer to this question, ambient displays, consisting of shape-‐changing interfaces for each patient, were developed. Shape-‐changing interfaces are artefacts that are transformed through physical change of shape as response to certain inputs, as opposed to using a screen for the representation of information (Rasmussen et al. 2012). The ambient displays developed as part of this thesis concede a hierarchy of information, where the most essential information provides an overview of patients’ vital signs. The ambient displays are designed to be perceived through peripheral vision, and allow for the acquisition of information concerning patients’ health statuses with minimal cognitive effort (Purves et al. 2013; Preece et al. 2002). Data regarding patients’ vital signs is measured by biometric sensors, and embodied by the shape-‐changing interfaces, allowing for remote communication between the patients and health care professionals. The ambient displays are public and are part of a common information space, shared among medical

professionals (Reddy et al. 2001). However, the embodiment of medical information through shape change allows for the encryption of private medical data, which ideally can only be decoded by the medical staff. By monitoring patients in real time and providing the hospital staff with an overview, patients’ health statuses can be compared, based on which metadata may be derived (Pignolo et al. 2013). User-‐authentication permits the medical personnel to access a deeper layer within the

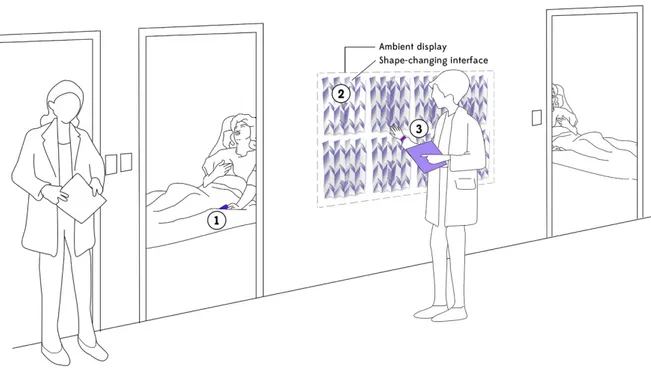

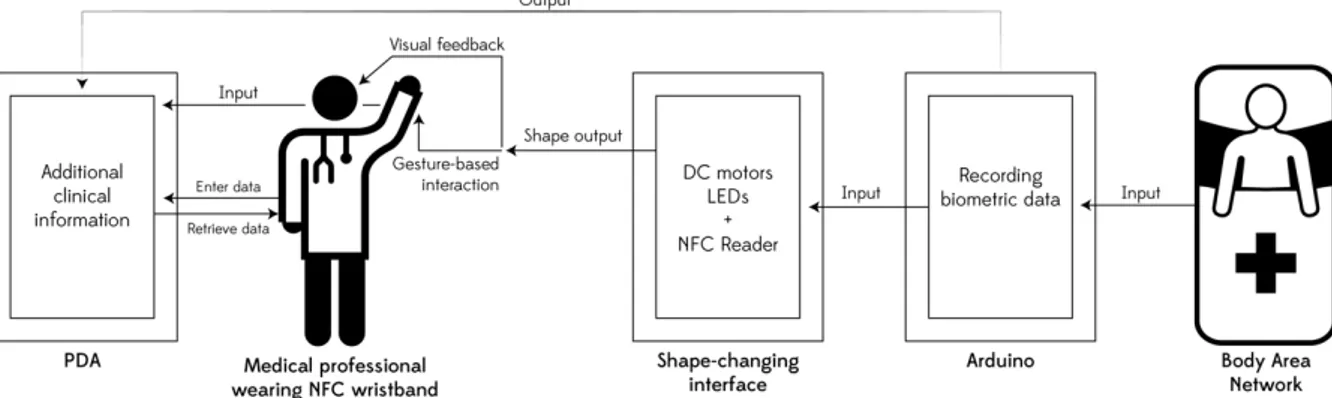

hierarchy of information, entailing clinical data such as patient EMRs, after gesture-‐based interaction with the ambient display (Shadbolt 2003). The additional clinical information is retrieved through the user’s PDA, entailing a private information space that enables content-‐adaption based on user-‐ authentication (see Figure 1).

The research conducted in this thesis project is positioned within the fields of ubiquitous computing, calm and unattended technology, and embodied interaction, within HCI and Interaction Design (Levin 2008; Weiser 1991). The thesis is theoretically grounded in these fields, as well as areas closer to engineering and the natural sciences, such as Ambient Intelligence (AmI) and cognitive

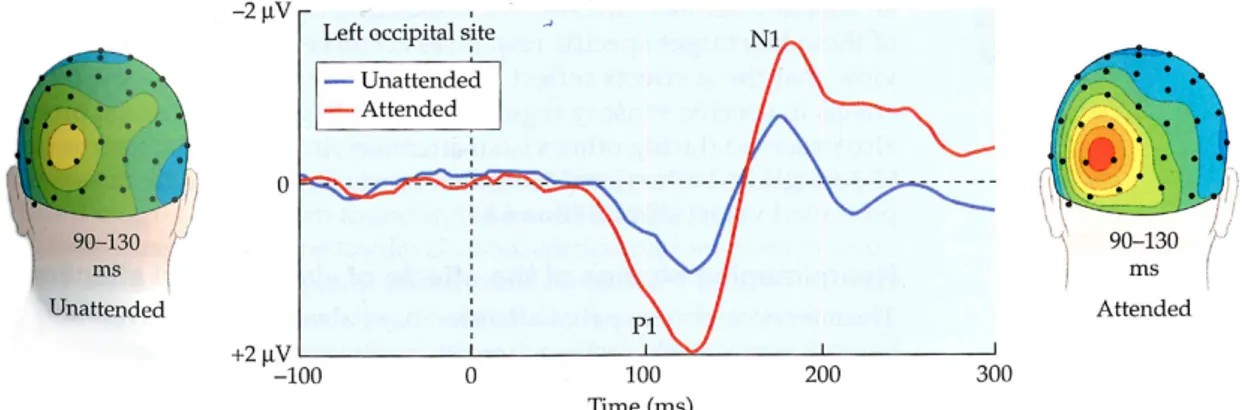

neuroscience (Irizarry et al. 2014; Shadbolt 2003; Aarts 2004; Purves et al. 2013). The principles of cognitive science were taken into consideration for the evaluation of the design artefact, as the research focuses greatly on reducing information overload and the offloading of cognitive processes, in furtherance of preserving the attention of healthcare professionals. By informing the medical personnel with clinical information through peripheral awareness, the efficiency of work is enhanced as medical tasks can be carried out simultaneously. Especially the principles regarding sensory

memory, and perceptual attention required for the acquisition of information are therefore of importance for this thesis project. The review of related works comprising shape-‐changing interfaces, ambient displays through biofeedback and remote communication through embodied interaction were significant in making decisions regarding the functionality and aesthetics of the ambient displays.

Figure 1: Schematic image of the ambient display in a hospital environment. (1) Data regarding patients’ vital signs is measured by biometric sensors, which are embodied by the shape-‐changing interfaces of which the ambient display consists. (2) The ambient displays provide an overview of patients’ vital signs, which can be considered the most essential information within the hierarchy of information contributed by the displays. (3) The additional clinical information within this hierarchy can be retrieved through the user’s PDA after interaction with the ambient display.

The various medical parameters are visualised by a prototype of the shape-‐changing interface through structure changes in paper and thread, as well as colour and movement of light. These changes in shape are driven by biometric data of the patients, measured by biometric sensors in a Body Area Network (BAN) (Latré et al. 2011). The choices regarding type of shape change and kinetics were chosen on the basis of their ability to be well perceived through peripheral vision. In addition, the aesthetics comprised natural aesthetics, as these are indicated to be advantageous for the stress levels of hospital staff and patients in healthcare environments (Mullaney 2016;

Beukeboom et al. 2012; Nejati et al. 2016).

The design process consisted of various iterative prototyping rounds, based on a field study conducted in a hospital environment. The succeeding prototypes were evaluated through four usability testing sessions, that to a great extent took place in situ (Koskinen et al. 2012). The ambient displays were created to be used by both nurses, as well as other medical professionals, although the prototypes were exclusively evaluated with nurses. The dual-‐task experiment, designed and conducted as part of the research, suggests that the shape-‐changing interface is capable of

informing medical personnel through peripheral attention, whilst the centre of attention is allocated to other activities. The interaction with the shape-‐changing interfaces is gesture-‐based, and

consequently allows the medical professional to access additional clinical information with the use of a PDA (Acampora et al. 2013). The interaction with both the shape-‐changing interfaces and

retrieval of additional clinical information with the PDA was evaluated through user testing with nurses, carried out in a hospital setting.

The experiential qualities of the ambient display, obtained through the various evaluation rounds, indicate the potential of the displays to grant medical personnel with a better overview of the health status of patients without increasing cognitive workload (Löwgren 2013). Accordingly, the work flow of medical personnel is not interrupted by the information presented through the ambient display. Moreover, the mobile nature of medical work is supported by providing access and the possibility to modify additional clinical information after interacting with the ambient display. All of the

aforementioned aspects are expected to enhance the efficiency of the activities carried out in a hospital environment.

This thesis projects contributes knowledge to the field of ubiquitous computing by providing a set of guidelines for ambient displays in a hospital environment, and to the field of calm and unattended technology through the establishment of guidelines for the design of calm artefacts. In addition, experiential qualities of an evaluation of a prototype of a shape-‐changing interface with medical staff provides knowledge for the field of embodied interaction. Furthermore, a proof of concept is contributed on the basis of a dual-‐task experiment, incorporating the shape-‐changing interface, as well as a scenario of the ambient display in use (Löwgren 2013).

1.1.1 Key audiences

The key audience of this thesis project consists of medical personnel employed in hospital

environments. Researchers and designers within the fields of embodied interaction and ubiquitous computing, situated within Interaction Design, are considered an additional audience.

1.1.2 Collaboration

This thesis project was carried out in collaboration with the department of Internal Medicine (Internmedicin Avdelning 5) at Skånes Universitetssjukhus (SUS) Malmö.

2. Methodology

Research through design (RtD) and constructive design research are the research approaches that were employed during this thesis project. RtD is “a research approach that employs methods and processes from design practice as a legitimate method of inquiry” (Zimmerman et al. 2010, p.310). Constructive design research, as described by Koskinen et al., refers to a practice-‐based approach situated within RtD, with a close analysis of design experiments (Koskinen et al. 2012; Krogh et al. 2015). Multiple design experiments and evaluation sessions were carried out in situ as part of the research (see Chapter 2.1.3). The design research approach employed in this thesis consisted of a three-‐step work process where objectives were formulated, and realised through experiments that evaluate the design artefact, where design knowledge was constructed based on the results and reflections of these experiments. Accordingly, the knowledge contributed in this thesis project is derived from the findings of the construction and evaluation of a design prototype in a healthcare context through several iterative experiments of succeeding prototypes.

Koskinen et al., state that the emphasis of the design research should not be on its specificity, losing the cross-‐disciplinary and exchanges with other forms of research (Koskinen et al. 2012). In line with this argument, the research and conducted experiments have a partial foothold in the natural sciences, and are theoretically grounded in both design-‐based research, as well as literature-‐based research in the realm of the natural sciences. Furthermore, the thesis project, and particularly the artefact created, are based on canonical examples of related work within the field of Human Computer Interaction (HCI) and Interaction Design. The empirical grounding for this thesis project was attained through field research and evaluation sessions in the intended context of the design artefact, in collaboration with healthcare professionals (Löwgren 2007).

The design and research process consisted of quantitative, qualitative and design construction methods, which are described in more detail in the sections below.

2.1 Methods

2.1.1 Field research

Ethnographic research, as David R. Millen states, typically includes field work or field research. The aim is, as described by Blomberg et al., “to provide designers with a richer understanding of the work settings and context of use for the artefacts that they design” (As cited by Millen 2000, p.280). As part of the field research, a workplace study was conducted at the Internal Medicine department at SUS Malmö to gain insight into the technological challenges this department faced, especially regarding the efficiency of the medical work carried out by nurses. A combination of qualitative methods was employed during the initial field research. These qualitative methods included participant observation and an in-‐depth interview with the head of the department of Internal Medicine. According to Mack, Woodsong, et al. “the in-‐depth interview is a technique designed to elicit a vivid picture of the participant’s perspective on the research topic. During in-‐depth

interviews, the person being interviewed is considered the expert and the interviewer is considered the student” (Mack et al. 2005, p.29). Based on the findings of the workplace study, the final research question was formulated (see Chapter 1.1).

2.1.2 Literature-‐based research

Literature-‐based research as a method consists of reading through, analysing and sorting literatures “in order to identify the essential attribute of materials. The conduction of literature-‐based research consists of grasping sources of relevant researches and scientific developments and understanding what predecessors in a specific field have achieved, alongside the progress made by other

researchers” (Lin 2009, p.179). Literature-‐based research as a method has been interwoven and applied throughout the process, but has especially been useful during the establishment of the theoretical framework. Literature regarding the technological advancements in ubiquitous computing and ambient intelligence in healthcare contexts, and research concerning the implementation and use of technology in hospitals provided a deeper understanding of the technological possibilities within such a context (Favela et al. 2004; Bardram 2003; Andersen et al. 2009). A literature review on the theory of cognitive neuroscience granted insights into human perception, attention and memory. The derived knowledge served as grounding for the design of an unattended artefact, and provided essential knowledge for the construction of a dual-‐task

experiment, which was used as evaluation method (Levin 2008; Purves et al. 2013). Literature and related work within HCI and Interaction Design, such as research concerning shape-‐changing interfaces, ambient displays and Social Awareness systems, were consulted as onsets for possible design solutions, and granted an overview of the state of the art of the areas of embodied and tangible interaction (Visser et al. 2011; Rowan & Mynatt 2005; Davis & Roseway 2013; Yu et al. 2014).

2.1.3 User evaluation

The several succeeding prototypes were evaluated in both lab and field settings (Koskinen et al. 2012). The lab approach encompassed an experiment that was conducted to determine whether the artefact could inform its user pre-‐attentively, as well as evaluate the overall user experience. “In constructive design research, the epitome of analysis is an expression such as a prototype. It crystallises theoretical work, and becomes a hypothesis to be tested in the laboratory” (Koskinen et al. 2012, p.60). The lab approach towards evaluating prototypes has its foundations in the natural sciences, and was in this case based on the principles of cognitive neuroscience regarding

perception, attention and memory. The experiment consisted of a dual-‐task experiment and was carried out with the purpose of evaluating the user experience of the prototype, as well as providing a proof of existence. The experiment was conducted on five persons, consisting of medical

personnel, as well as people with a background in Interaction Design. Experimenting in a lab setting gives researchers an opportunity to focus on one thing at a time. In this case, this was achieved by including three different sessions within the dual-‐task experiment, each of which measured distinctive aspects of the artefact. The design of the dual-‐task experiment and the purposes of the particular sessions are described in more detail in Chapter 6.3, and Appendices C and D. In accord, the evaluation of the prototype through the dual-‐task experiment falls within the category of accumulative design experimentation, as one of the five methods of knowledge production

proposed by Krogh et al. In accumulative design experimentation, “the design sketches and models are focused on testing specific parts and wholes and are carried out in closed lab settings where the design experiments are evaluated for their cognitive qualities, rather than contextual

appropriateness” (Krogh et al. 2015, p.46). The dual-‐task experiment was conducted on one individual at the time, and was initiated by presenting an introduction video that explained the functionality of the prototype, which was essential for the subsequent task. Test subjects were provided with a document that explained each session in writing and included fill-‐in forms, which were used to evaluate the results. All three sessions within the dual-‐task experiment lasted four minutes, and were explained in detail beforehand. The results of the dual-‐task experiment were acquired by precisely measuring either the response time of test subjects, the information acquired from the prototype, or both, depending on the purpose of the session. After each dual-‐task

The evaluation of prototypes in the lab allows for the testing of several specific aspects of a design artefact and may provide a proof of existence. However, as the design artefact will eventually be used within a particular context, evaluation in a field setting is essential. Therefore, subsequent to the accumulative design experimentation within a lab context, several prototypes were tested at the department of Internal Medicine section 5 at SUS Malmö. The evaluations of the successive

prototypes focused on the implementation of, and interaction with the artefact within the hospital environment, and were evaluated with a nurse and the head of the department. According to Koskinen et al., “rather than bringing things of interest into the lab for experimental studies, field researchers go after these things in natural settings, that is, in a place where some part of a design is supposed to be used. They are interested in how people and communities understand things around designs, make sense of them, talk about them, and live with them. The lab decontextualizes; the field contextualizes” (Koskinen et al. 2012, p.69).

In the second evaluation, several distinct versions of tangible prototypes of the shape-‐changing interfaces were discussed and compared through experience prototyping, by exploring and evaluating the design ideas. “The main purpose of Experience Prototyping in this activity is in facilitating the exploration of possible solutions and directing the design team towards a more informed development of the user experience and the tangible components which create it. At this point, the experience is already focused around specific artefacts, elements, or functions. Through Experience Prototypes of these artefacts and their interactive behaviour we are able to evaluate a variety of ideas — by ourselves, with design colleagues, users or clients — and through successive iterations mould the user experience” (Buchenau et al. 2000, p.428).

The third evaluation entailed the examination of interaction with a digitised prototype of the ambient display, consisting of a video sketch which was tested through projection at the intended place of use, adopting a Wizard-‐of-‐Oz technique. “The Wizard of Oz (WOz) technique is a method in which participants are led to believe they are interacting with a working prototype of a system, but in reality, a researcher is acting as a proxy for the system from behind the scenes. Unseen by the participant, the researcher (i.e., the “wizard”) is able to intercept and shape the interaction between the participant and the “system,” without having an actual system up and running. The goal of the method is to allow the user to experience a proposed product or interface before costly prototypes are built” (Martin 2012, p. 204). The evaluation session was based on several scenarios, where the participants were asked to act according to these scenarios by interacting with the prototype.

The final user testing round evaluated the interaction and user experience on the basis of a hi-‐fi prototype of the shape-‐changing interface in situ. The method appropriated for this evaluation entailed experience prototyping (Buchenau et al. 2000).

The various user testing sessions are described in more detail in Chapter 6.5, Chapter 6.7 and Chapter 6.9.

3. Clinic of Internal Medicine

3.1 Internal Medicine

Internal medicine regards the medical discipline which focuses on the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nonsurgical conditions that primarily affect adolescents, adults, and the elderly. Departments of Internal Medicine are usually located in the hospital, and encompass both common and complicated diseases. The discipline of internal medicine is therefore highly diverse, and includes a vast amount of subspecialties such as cardiology, endocrinology and infectious disease. The medical work conducted by an internist consists of abundant contact with patients, and includes health maintenance and disease screening, the diagnosis and care of acute and chronic medical conditions. Nurses employed in departments of internal medicine also spend a considerable amount of time at the patient’s bedside (Arneson and McDonald 1989; Association of American Medical Colleges 2015).

3.2 Field research

3.2.1 Setting

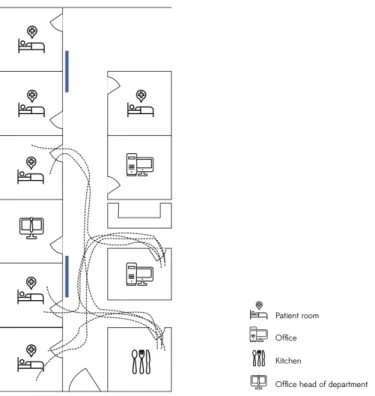

The internal medicine department in Skånes Universitetssjukhus consists of sections 7, 8 and the acute internal medicine section in Lund, and sections 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 in Malmö. The research for this thesis project was carried out at section 5 of the department of Internal Medicine in Malmö. The department of Internal Medicine at SUS works closely together with the emergency department, and includes patients who have been transferred from this department. The expertise of the department regards the internal medical diagnosis of acute diseases and multi-‐organ diseases in adults (Andersson 2015).

3.2.2 Study design

A multi-‐method approach was employed, which included direct observations and a semi-‐structured interview. The observation applied attention to the technology used in the different work spaces of the department. Furthermore, through observation a sense of the place and an awareness of the atmosphere in the clinic was acquired. Subsequently, an interview was conducted with Henrik Elg, a nurse and the head of the department of Internal Medicine section 5. The purpose of the interview was to gain a better understanding of the work carried out in the department, and the types of technology employed by the nurses. As the interview was conducted during the first meeting, the research focus of the thesis project was shortly introduced antecedent the interview. The interview was semi-‐structured: a set of open questions was prepared, but the interview was carried out in a flexible manner, and consisted of follow-‐up questions and subsequent in-‐depth conversations of certain aspects. A face-‐to-‐face interviewing approach was appropriated, since depth of meaning is important and the research was primarily focused in gaining insight and understanding (Ritchie & Lewis 2003). A large part of the interview was carried out in the office of the head of the

department. However, as some questions were difficult to answer through solely explaining matters, several aspects and situations were shown in use at different locations in the ward. A more detailed description of the interview can be found in Appendix A.

3.2.3 Findings

Medical professionals at the department of Internal Medicine work in multi-‐disciplinary teams, consisting of nurses, assistant nurses, a doctor, a physiotherapist, and occasionally an occupational therapist. Three teams within the section attend to twenty-‐one patients, each of which stay for five to six days on average.

The working days of nurses are divided in three shifts of eight hours. Shifts are initiated by manually measuring the vital signs (oxygen saturation levels in blood, blood pressure, heart rate and body temperature) of each patient, and entering this data into the patient’s electronic medical record (EMR). Although medical records are digitised, there is no technology present in the patient rooms to access these. The medical personnel on the ward have access to one mobile laptop that is located in the corridor of the ward, which is used by nurses for the administering of medicine. The laptop is mounted on a trolley, providing space for the storage of medication, paper charts and other equipment. Nurses use one of the two stationary PCs in the team’s office to retrieve or modify information from the EMR. Accordingly, nurses walk back and forth (on average forty-‐five times during each shift), from the patient room to the office in order to request or modify data in the patient’s medical record. Needless to say, this results in inefficient working situations, as it requires the nurses to do double work. In addition, nurses are often interrupted when moving from one space to another, which requires them to attend to various activities simultaneously. As a consequence, the work is stressful and time-‐consuming, leading to less time for personal contact with the patient. Furthermore, it emanates an increase in error-‐making due to the fact that nurses have to copy details from the computerised medication chart to paper, which is another example of a workaround resulting from the hardware devices that fail to support the clinical workflow.

During work shifts nurses often consult the medical record, in which they most frequently access lab

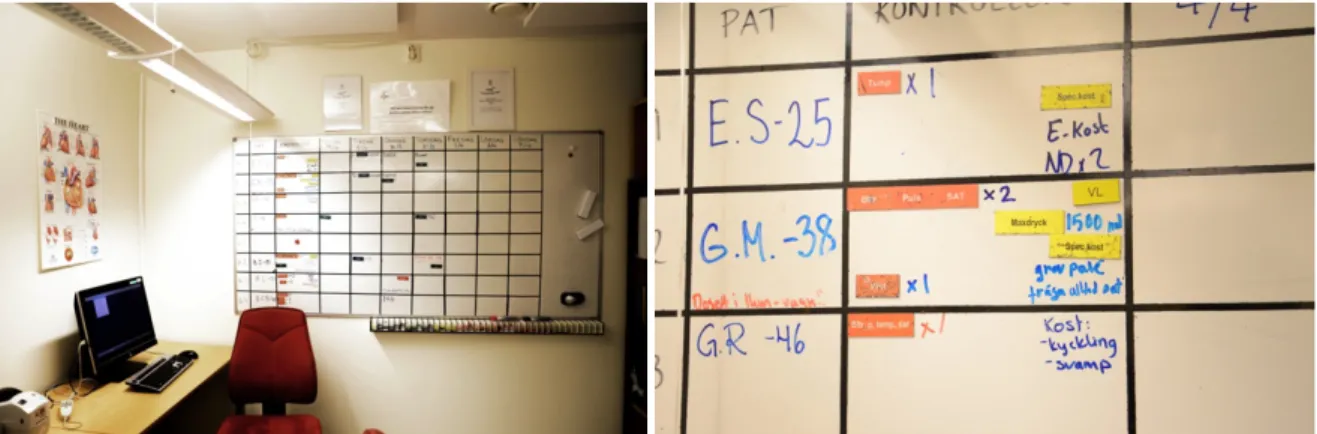

results, medication records, information regarding the vital signs, and results of scans, such as x-‐ray and CT scans. However, Melior, the EMR system operated in the department of Internal Medicine, is dense, hard to navigate through and does not provide a clear overview of a patient’s current health status or medical history. In order to provide the medical personnel with a quicker overview of the patients currently on the ward, analogue whiteboards are located in the main offices (see Figure 2). These boards help to communicate information regarding patients’ conditions and locations, and are often turned to by the hospital staff. In addition, information regarding the vital signs and a patient’s schedule for the upcoming week are disseminated through the whiteboards. However, as

whiteboards are not digital, they need to be filled in and updated by hand, which further decreases the efficiency of the medical work.

Figure 2: Whiteboard at one of the offices at the department of Internal Medicine at SUS Malmö. Various coloured tags are placed on the whiteboards, indicating different types of information and activities.

The field research indicated that medical work carried out by the nurses on the ward of is stressful and inefficient. A shortage of nurses has arisen as a result of this, while in the present situation it is difficult to employ new nurses. The objectives indicated by the head of the department of Internal Medicine, on the basis of these concerns, were taken as the outset for this thesis project.

Accordingly, the aim is to design technology that increases the efficiency of medical work executed by nurses, and hereby provide them with additional time to spend with the patients. The bespoken way of accomplishing this is by simplifying or automating the process of measuring patients’ vital signs, as indicated by the head of the department of Internal Medicine: “Measuring patients’ vital signs and the entering of data should be more efficient, and should be automated, so we can spend time with the patients.” Furthermore, the design of the technology should prevent workarounds, by improving the retrieving and entering of clinical information in frequently accessed spaces.

The interactive whiteboards, yielding a quick overview on the status of each of the patients on the ward, were a point of reference during the design process, following the aspirations of the head of the department of Internal Medicine: “I would like to have an overview of all the patients on the whiteboard, displaying the most important information such as the vital signs and the process of the patient. Whenever I ‘click’ on one of the patients, I would like to get access to more information that is in the medical record.” The desire to improve the overview of patients’ current health statuses, by granting access to a hierarchy of information as well as a more visual representation of clinical data in the electronic medical record, became apparent. The whiteboards therefore served as an inspiration for the ambient displays created in this thesis, yet the displays were not initially developed with the intend to replace the whiteboards but rather as a complementary means of communication.