Chilean Uprising

Grassroots movements as an instrument of contestation

to social injustice and neoliberal urbanism

Camila Freitas de Souza

Faculty of Culture and Society

Urban Studies: Master's (Two-Year) Thesis 30 credits

Autumn Semester 2020

2 Chilean Uprising

Grassroots movements as an instrument of contestation to social injustice and neoliberal urbanism

Camila Freitas de Souza

Faculty of Culture and Society

Urban Studies: Master's (Two-Year) Thesis 30 credits

Autumn Semester 2020

3 SUMMARY

In October 2019, a wave of massive demonstrations took place in Santiago de Chile and this movement was stamped in several newspaper covers worldwide. People shouting against the Chilean neoliberal system, holding posters with anti-imperialist sayings, and organizing artistic interventions on the streets went viral in social media. The message was clear – for several consecutive months, people in Chile were actively questioning the political, economic, and societal systems as well as the power struggles faced in the country. Relying on the 2019-2020 Chilean Uprising as a case study, this research investigates the most recent Chilean grassroots movement under a human geography and urban studies lenses. The use of newspapers articles and semi-structured qualitative interviews as main empirical materials is the foundation towards the unpacking of the main discourses surrounding the movement, raising reflections on the Chilean inhabitants’ perceptions of the protests by bridging these notions with the Chilean society, its history, social structures, and power distribution.

Drawing the discussion on postcolonial, decolonial, and critical urban theor ies, a critical perspective of the neoliberal system, the Lefebvrian Right to the City concept, and Manuel Castells' grassroots movements definition, this thesis debates on the consistency of the Santiago de Chile demonstrations by connecting its social claims to the field of urban studies for the understanding of social and spatial constructions, as well as their struggles, in the Chilean context. The newspaper pieces are thoroughly analyzed with the assistance of critical urban theory, critical discourse analysis, as well as the interviewees’ impressions of the mediatic discourse towards the social movement. The 2019-2020 Chilean Uprising, its social causes, organizational capacity, and social impacts are also debated with the interview participants, who raised reflections about the connections between this social movement claims and the Latin American and Chilean historical and collective processes that are closely related to actions of geopolitical power that occur ever since the beginning of the Latin American history.

This thesis ends with a brief discussion on the research findings and a suggestion for future academic investigations about this topic. The analytical framework is cited and debated in connection with the theoretical perspectives raised in the theoretical chapter of this research. Keywords: grassroots movements; postcolonial and decolonial theory; critical discourse analysis; Santiago de Chile

4

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1. INTRODUCTION...5

1.1 Aim and Research Questions ...7

1.2. Layout of the Thesis ...8

2. METHODOLOGY...9

2.1. Literature Review...9

2.2. Discourse Analysis ... 10

2.3. The Use of Interviews in Qualitative Research ... 12

2.4. Role of the Researcher... 13

2.5. Research Methodological Limitations... 14

3. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK ... 16

3.1. Postcolonial and Decolonial Lenses... 16

3.2. A Critical View of the Neoliberal System... 17

3.3. The Urban Perspective: “The Right to the City” and Grassroots Movements ... 19

4. CASE PRESENTATION ... 22

4.1. The Chilean Big Picture – history, society, and statistics ... 22

4.2. Grassroots movements emergence in Santiago de Chile ... 24

4.3. The last Chilean Uprisings – two major moments of social movements in Santiago de Chile .... 25

5. ANALYSIS ... 28

5.1. Chilean Uprising at first sight – impressions and main discourses... 28

5.2. How power relations shape the demonstrations – the violence question... 30

5.3. Which main voices are represented by the newspaper articles – and how does it relate to the way the movement is being portrayed by the media? ... 32

5.4. Towards the social causes and citizens’ rights defended by the Chilean Uprising ... 33

5.5. Uprising's organization capacity – historical and technological components ... 34

5.6. Current grassroots movement and its’ social impacts in Chile ... 36

6. CONCLUSION AND DISCUSSION ... 39

6.1. Reflections of Analytical Framework ... 39

5 1. INTRODUCTION

The act of people mobilizing themselves for a societal change has been studied in the social movement studies field since the 19th century, starting with researchers such as Max Weber and Karl Marx analyzing the working-class movements and their impact in society (Eder, 2015). Activism in relation to urban studies, however, is derived from the reflections on social relations, production, as well as struggles over the space (see, e.g., Andretta, Massimiliano, Gianni Piazza, 2015; Greenberg & Lewis, 2017; Harvey, 1985; Miller, 2006; Miller & Nicholls, 2013) and its' study, is, then, endorsed by the evaluation of power relations towards the collective consumption, including but not limited to the access to housing, education, health care, transportation, and public space (Castells, 1983).

Urban activism, like any social movement that takes place in the city environment, cannot be disconnected from the conceptualization and practice of neoliberalism in modern societies. The neoliberal mode as the hegemonic form of governing cities (c.f., Swyngedouw, 2009; Žižek, 1999) is based on economic as well as political performs that produce capital accumulation through the reduction of state services (such as the provision of education and housing) and the increase of non-restricted business operations and public-private partnerships (c.f., Brenner & Theodore, 2002; Harvey, 2005) as a market solution for all economic and social challenges (Peck & Tickell, 2002). The practice, as greatly explored by urban studies scholars, tends to generate gentrification in the city, boosting citizens to suffer from an uneven development of urban areas as well as “accumulation by dispossession” under the capitalist state and the capital accumulation (Harvey, 2003a).

Further, under a neoliberal context, looking through social movements with the grassroots lenses is of extremely relevance because of the consistent struggles and formations of these movements in cities of both Global North and South (Ward & McCann, 2006). The assembly between social change and grassroots movements (or social movements that come from the bottom -up and have the civilians as the main basis for political and economic changes) is considered as highly important to the analysis and understanding of these actions within the context of urban studies (Miller, 2006). This is due to Castells (1983) reflection on social relations versus urbanization, with social mobilizations constructed by alliances of mixed classes t owards the claim of collective consumptions. As “a city that is always in the process of becoming, of being accomplished is always then, in part, a ‘new city’, demanding of us ‘new paths’” (Ward & McCann, 2006, p. 193), the grassroots approach has the ability to contribute towards the reflection upon political actions and movements as well as their capacities of reshaping the city.

In a Global South perspective, neoliberal Latin-American states are molded with additional layers to this ‘capital accumulation’ and ‘uneven development’ as even the label ‘development’ itself (in which Global South countries are categorized as “underdeveloped”) is argued to symbolize a hegemonic form of representation created under a Western vision (Escobar, 1992). The Global South’s embracing of these northern ways of thinking society with the implementation of “1st

World” notions, such as neoliberal government and city and social development is, as postcolonial theorists discuss, a tool of domination (ibid.). In seek of this European’s ideals, the implementation of neoliberalism, as well as development politics in Latin America, come with severe effects in the societal, political, and spatial levels.

In fact, a recent United Nations report on inequalities in human development (UNDP, 2019) has identified that Latin America is the most unequal region of the world and that no other place of the

6 globe has 10% of the richest people concentrating 37% of the total wealth. What the report calls of “horizontal inequalities” is deeply “connected to a culture of privilege with roots on colonial times” (ibid., p. 53) that emerged from the people’s submission of an injustice division of land and historically evolved into the implementation of classist militarized dictatorships that raised states’ international debts and, later on, to the implementation of a neoliberal form of governance (ibid.). Social inequalities are, then, a common ground of all Latin America and an extra layer to the debate of southern societies, functioning as the basis of urban maladies that are broadly discussed among urban scholars of the Global South – with some of these discussions relying on concepts such as peripheral urbanization (c.f., Caldeira, 2017), urban fragmentation (c.f., Borsdorf, Hidalgo, & Sánchez, 2007), gentrification (c.f., Casgrain, 2014), urban informalities (c.f., Hoai & Yip, 2017; Roy, 2005), and beautification (c.f., Harms, 2012).

Hence, the foundation of Latin American social movements is based on a response to this “commodification, bureaucratization, and cultural massification of social life brought about by these hegemonic formations” (Escobar, 1992, p. 426), making use of anti-imperialist discourses and in defense of a more independent and participative social, political, and cultural forms. The predominant features of grassroots movements in Latin America are, then, as follows: 1- they are essentially local, branching out either horizontally or vertically but always from the bottom-up, 2- they represent plural struggles suffered from the most diverse societal levels; 3- they expose a certain distrust on politics, politicians, and political organization, 4- they are not necessarily driven by economic reasons only, as culture and community are likewise significant (ibid.). Grassroots, in this context, is seeing as a major contributor to the redefinition of social justice, basic needs, and democracy (ibid.).

Additionally, for some urban critters, social movements in South America are classified as powerful actors in urban transformations, planning, and management, allowing civil society to create and implement socio-spatial strategies and functioning as direct opposers of urban neoliberalism and it’s outcomes (de Souza, 2006). The movements claim for an ‘autonomy’ in order to emphasize the need of a free society that does not suffer from political oppression either technocratic planning – or a top-down style characterized by a lack of popular participation in the planning process (ibid.). Following this concept, the urbanistic approach of these movements is supplemented with another level as there are fundamental discussions towards the possibility of the emergence of a bottom-up urban reform that is capable to take form despites the state (ibid.). Regarding Chilean social movements, the case study of this thesis is consisted by the analysis of the most recent demonstrations of Santiago de Chile that began in October 2019, with the outbreak of the Chilean government model followed worldwide through the mediat ic coverage of the citizens’ protests. Santiago de Chile’s inhabitants were standing primarily against the raise of a subway fare, but were also upraising questions towards the cost of living, privatization, and inequalities situations in the country ( c.f., e.g., BBC, 2019). Analyzing grassroots movements in Chile enhances critical urban debates of neoliberalism under Global South contexts, as the Chilean case was, for decades, widely perceived as a successful neoliberal implementation – in both planning and governance. The urban transformations and new forms of producing the space emergent from the military regime in 1973 (as well as its continuous application during the following decades) (Caldeira, 2017), however, have actually being questioned from both citizens and scholars/academia and recent studies have shown the flip side of this neoliberal adoption in Chile, by connecting the model to the production of spatial segregation, deterioration, increase of violence, and even mental illness (Ducci, 1997).

7 The current demonstrations and people’s occupations on the urban space of Santiago de Chile, nonetheless, are not unprecedented to the Chilean history. Indeed, the current protests are greatly connected to the 2011 urban acts of Santiago de Chile, when the citizens (especially the students) have appropriated the urban area to claim for public education, diversity, freedom of native people (the Mapuche), and tax reform (Toso, 2011). The acts from 2011 were considered as the “awakening” of Chilean social movements, boosting the re-politicization of Chileans who used to perceive neoliberalism as a natural feature of their society and since then have recognized their system as a “restricted democracy” (ibid.). The 2019-2020 Chilean social movement that is discussed on this thesis comes, then, with a broad and complex historical background that is covered by an economic and social crisis of a neoliberal model and this project relies on the people’s uprises to enhance the debate towards neoliberal as well as horizontal forms of politics, democracy, grassroots movements, and the struggles to achieve the right to the city.

1.1 Aim and Research Questions

This project makes use of critical urban theory as well as postcolonial and decolonial theories for the analysis of the 2019-2020 Chilean social movement regarding its contributions towards the social-political debate under a Global South context as well as its social challenges, effects, and capabilities. The thesis' framework was defined with the intention to create an empirical, theoretical, and epistemological contribution to grassroots movement studies in Latin America, by bridging the Chilean reality and struggles to a cosmopolitan and global deliberation, in order to increase plural discussions in the urban studies field (Robinson, 2016).

In summary, the Chilean uprising is analyzed towards its social and spatial struggles. The sociality of the movement is debated under the concept of the movement formation, influence, and perception among society whereas its spatiality is discussed both towards the social struggles over space (Lefebvre, 1996) as well as its immediate interferences relating to their impacts towards social behavior. Drawing on urban studies concepts, such as neoliberal planning (Swyngedouw, 2009; Žižek, 1999), Lefebvre, ‘the right to the city’ (Fernandez, 2018; Harvey, 2003b; Junior, 2005; Lefebvre, 1996; P Marcuse, 2012), grassroots movements (Castells, 1983; de Souza, 2006; Escobar, 1992; Miller, 2006; Ward & McCann, 2006), and urban gentrification (Casgrain, 2014), the main goal with this study is to unpack the connections between the Chilean Uprise against the current political and social systems and urban studies.

In this thesis, the 2019-2020 Chilean protests are going to be explored within its socio-political as well as spatial impacts. The main pillars of this research are formed by 1- a literature review within the concepts of urban activism and grassroots movements, neoliberal planning, and ‘the right to the city’ for the enrichment of an urban studies debate, as well as postcolonial and decolonial studies in order to bring the discussion towards a Global South, Latin American, and Chilean perspectives; 2- a discourse analysis of local and national newspapers articles throughout the months (from October 2019 until May 2020) for the reflection upon the main discussions around the movement and a greater understanding of the Chilean societal realities (Hastings, 2014); 3- the use of social research qualitative methods (Bryman, 2016), such as semi-structured interviews (Evans & Jones, 2011), with the intention to represent the citizens' life, opinions, and claims around the movement. Above all, these pillars were defined with the aim to understand the connection between the most recent case of urban activism in Chile and the critical urban theory debate on social relations, coloniality of power, and the struggles over space.

8 • What are the main discourses addressing the movement and how are they materialized in

the demonstrations?

• How do Chilean inhabitants perceive the recent grassroots demonstrations in Chile and what reflections do they have regarding the relationship between such social movement and their own society?

1.2. Layout of the Thesis

After this introduction chapter, in which I explained the basis of this research and its aim, purpose, and questions, there will be a following chapter focused on the methodologies I relied upon for the collection of the empirical data, there is mainly formed by a cr itical discourse analysis of newspapers articles and the conduction of semi-structured interviews according to the qualitative research approach. This chapter also raises some inputs on the researcher position, roles, validity, and reflection practices, as well as the limitations derived from the conduction of research in a pandemic time. Then, the theoretical toolkit, which is mainly founded by the Lefebvrian Right to the City, the neoliberal debate from a critical urban theory perspective, the grassroots movements concept, and the postcolonial and decolonial theories, is presented and discussed. Subsequently, there is the Case Presentation chapter, in which the 2019-2020 Chilean Uprising is described in-detailed, together with its relations with the Chilean history and society. The analysis comes next, in which the presentation of the empirical material takes place followed by the collected data co -relations with the theoretical outline. Finally, the Conclusion chapter presents the overall research discussions and findings in relation to the two research questions raised at the beginning of this journey.

9 2. METHODOLOGY

This chapter introduces the methodological tools used for the delineation and evaluation of this research as well as justifies the chosen methods basing its’ arguments on previous academic productions. The thesis design and production process will also be presented together with some research reflections and methodological limitations. The chapter also describes in detail how the collection of the empirical materials took place in this research. Concisely, this thesis relies on a literature review of critical urban theory as well as postcolonial and decolonial theories, a critical discourse analysis, and the conduction of qualitative semi-structured interviews. The empirical materials are mainly formed by newspaper articles and interviews transcriptions. During the collection process of the literature review, I focused on bringing together general concepts of urban research to the Global South and Latin American contexts. The analytical material of media productions provided a better understanding of the recent social movement activities in Santiago de Chile and enhanced the reflections on the discursive storylines dealing with the case. The use of qualitative research interviews, nonetheless, strengthened the contextualization and discussion towards protest occurrences in the area.

2.1. Literature Review

The aim of this literature review is to gather academic materials (articles, dissertations, and books) that explore the concept of social movements and urban activism through social, political, and spatial perspectives aiming to raise familiarity on how urban scholars are assessing and studying the grassroots movements phenomenon in urban settlements as well as to explore social movements’ concepts in a worldwide range. Although this review has covered Western debates on urban activism, there was an objective to deepen the reflection on materials that discuss Global South, Latin American, and Chilean perspectives on social movements as well as their relations to postcolonial and decolonial approaches.

The literature review is focused on critical urban theory and postcolonial and decolonial studies as me, as an outsider researcher (or non-Chilean citizen), understand the importance of bridging the general Western ideas to a local dialogue. Therefore, this review will be covering ‘traditional’ critical urban theory in English productions as well as postcolonial and decolonial perspectives under Latin American and Western productions. Special attention has been made to bring emphasis to Chilean scholars who discuss historical aspects of Chilean society, social movements in Chile, as well as socio-political and economic perceptions of the country in order to soften the Western idea of totality and society (Quijano, 2007) in the debate.

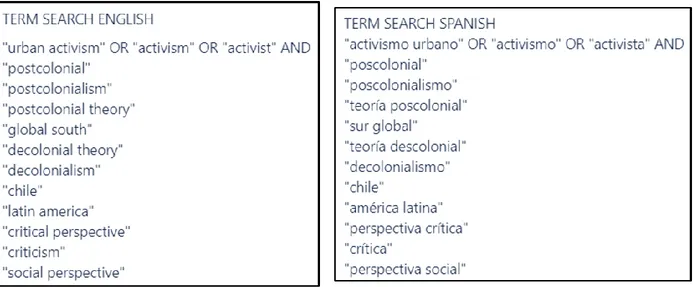

I have used Google Scholar and Malmö University Library Journal Search as the main tools in which I have searched for the academic materials and the defined terms of the search were 1- in English: ("urban activism" OR "activism" OR "activist") AND ("postcolonial" OR "postcolonialism" OR "postcolonial theory" OR "global south" OR "decolonial theory" OR "decolonialism" OR "chile" OR "latin america" OR "critical perspective" OR "criticism" OR "social perspective"); 2- in Spanish: ("activismo urbano" OR "activismo" OR "activista") AND ("poscolonial" OR "poscolonialismo" OR "teoría poscolonial" OR "sur global" OR "teoría descolonial" OR "decolonialismo" OR "chile" OR "américa latina" OR "perspectiva crítica" OR "crítica" OR "perspectiva social") (see Figure 1 for a better visualization and understanding). After academic data generation under these terms, I have read each possible-relevant article’s abstract to evaluate if each piece would fit the main concepts addressed in this thesis.

10

Figure 1 Screenshot of term search in English and Spanish. I have used Trello as a software to organize and update the searching process. Some terms were adapted throughout the process to avoid a great amount of ‘garbage data’

2.2. Discourse Analysis

The utilization of discourse analysis as a method in this thesis plays a role in boosting the reflection upon how the recent activist demonstrations in Santiago de Chile are being narrated and conceptualized in the Chilean society. I have focused especially on the power relations that are taking place during the acts and, therefore, the main approach of the analysis is inspired by Critical Discourse Analysis (D’Angelo & Kuypers, 2010; Hastings, 2014). This part of the research was conducted before starting the contact of organization and citizens for the procedure of interviews and besides serving to the assistance of my own situation as a researcher on the case, my main goal with this method was to understand how language and narrative used in the empirical material were capable of reproducing power relations, so I have bridged the usage of wording, grammar, pictures, videos, graphs, infographics, and maps available in the sources to a wider societal structural process and reflected upon why certain words, text, and symbols were being used, why they were being used in specific ways, and how their significance was being matured, as well as whom was the discourse trying to convince (Hastings, 2014).

The empirical data used for the discourse analysis exercise came entirely from online sources, relied on newspaper articles published by the traditional as well as the alternative media. I have also focused on the news pieces written in Spanish and from local and national portals. Since the Chilean demonstrations have started in October 2019, I have divided the analyzed articles according to time in order to be able to cover the movement while it was still happening but also to raise a richer analysis of how the discourses around it were being constructed throughout time. Considering that the production of this research has happened until the third week of May 2020, this thesis is addressing the eight first months of the movement. I, then, targeted the evaluation of around 15 newspaper articles on total, specifically divided to every 15 days of publication. I have used Google News as a searching tool and the terms “Santiago”, “protestas”, and “estallido” to target only news pieces related to my case study.

The criteria to delineate the reliability of the newspapers were established by the following actions: 1- I have visited the main webpage (or front page) of the portals and checked the kind of recent headlines of news piece they had; 2- I have checked the ‘about us’ section of the websites to know

11 more about the history of each one of them; 3- I have checked the reach of the newspapers by looking if they had a ‘national version’; 4- I have analyzed the language use of the portals to see if they followed a journalistic pattern rather than a colloquial language; 5- I have visited each newspaper official social media profile (mainly Facebook and Twitter) and checked the number of followers and kinds of interactions; 6- Finally, I have spoken to my local contact persons in Chile so they helped me to demarcate the reliability of newspapers.

Further, I have made use of NVivo as a qualitative data analysis software for the labeling of newspapers’ articles (all written in Spanish and belonging to either local or national media) and EndNote as a notepad for the inclusion of some personal observations of all the material as the utilization of NVivo has served mostly for the evaluation of the news’ texts. After the reflection on the pieces’ content and establishment of patterns on the discourse and language use as well as with some pre-defined main concepts that were considered as important to focus on (such as the supportive or destructive arguments towards the social movement, the voice balance between protesters, civil society, and authorities among interviews, exposure of private opinions, and the portrait of the social space), I used deductive coding (Bryman, 2016) for the creation of 22 nodes (or subjects, that is, Academic Voices, Civil Society Voices, Economic Loss, Government Measures, Intergovernmental Organization Voices, Location, Manifestation Day, Mapuche Voices, Metro Fare, Movement Claims, Movement Reasons, People’s Money, People Power, Physical Impacts, Police Power, Police Voices, Political Impacts, Political Voices, Protesters Number, Protesters Profile, Protesters Voices, Social Impacts) that have been, later on, organized among five different clusters (that is Big Picture, Money Mention, Movement Impacts and Consequences, Use of Force, Voice Balance) for the exploration and evaluation of the data1. For

a better understanding of tagging distribution among clusters, see Figure 2.

Figure 2 Distribution of Clusters and Nodes for the newspaper articles' subjects labeling in NViv o

1As I am focusing on the main discourses addressing the movement, the clusters “Movement Impacts and Consequences”, “Use

of Force”, and “Voice Balance” are the ones that are presented and reflected in-depth in this thesis due to their high prevalence among the collected newspaper articles. This is better debated in the Analysis chapter of this thesis.

12 Lastly, this method plays an important role for the reflection upon the first research question of this thesis (‘what are the main discourses addressing the movement and how are they materialized in the demonstrations?’) as I have used news pieces to discuss about the conceptualization of this movement in the societal debates. The general perception of the movement was reflected through the interpretation of supportive as well as destructive discourses around the acts, the voice balance happening in the content of the newspapers’ interviews, the narrative of space, and the accentuation and minimization of statements. Visual productions, such as videos and pictures, have assisted me in the analysis of how these discourses supported in the texts are materialized in the acts – the discussions with the interviewees who were part of the demonstrations were also used for this reflection.

2.3. The Use of Interviews in Qualitative Research

As this research has been carried out in a timeframe of only four consecutive months, there would not be enough time neither resource to conduct a throughout ethnographic work. I have relied, however, on qualitative research methods for the reflection of the data gathered during the conduction of interviews with Chile’s residents as the interview brings a well-detailed and local contextual analysis to the study case (Clifford, Marcus, Fortun, & Fortun, 2010), functioning as a tool to investigate politics of survival at the micro-scale while situated within larger socioeconomic processes (Ward, 2017). The use of the interview method basis its relevance in this research as a tool to capture individual voices in an in-depth context (ibid.). I have conducted, then, semi-structured sedentary interviews (Evans & Jones, 2011), with both inhabitants who were part of the protests and who were not part of the social movement.

I have started performing the interviews with three contact persons who currently live in Chile (one who was born in Santiago and two who have been living in the city for the last five years) and from this point, I have made use of the snowball sampling (Bryman, 2016) to connect with a greater number of people. The first intention was to get in contact with 10 to 15 people living in the city. My target group was the residents of Santiago de Chile and I have planned to talk with both participants and non-participants of the demonstrations for a greater perspective on the views regarding the movement. As the movement is not exclusively formed by citizens in their individual levels, but also organized and created by non-profit organizations, political parties, and working and student unions2, I have also contacted all the organizations I could detect as part of the

movement through the observations of pictures, videos, and interviews published by the local traditional as well as social media with the aim of interviewing these groups to get in contact with their view of the movement.

The practice of observing and reflecting upon the images and videos of the protests that were posted online by traditional as well as alternative media, beyond the role of adding contextualization to interviews, were key to the construction of the analytical chapter of this thesis, as what people say is not necessarily what they do (Ward, 2017) and learning how to participate in the community as well as reflectively observing what they do is key to enhance the complexity of the research. Further, as Ward advises, while conducting observations, I have consciously tried to diminish the external interferences that were not connected to the case study, being ‘alone’ with my thoughts and consistently taking notes of my observations. Finally, critically observing online

2The organizations who are part of the 2019-2020 Chilean social movement are presented in detail in the Case Study chapter of

13 material has assisted me with my own familiarity with the movement and have prepared me with the basis for the conduction of better in-depth interviews.

Following the argument presented by Evan and Jones advocate (2011), sedentary interviews have been part of this research to encourage discussions towards people and society. Additionally, when conducting semi-structured sedentary interviews, I have frequently made use of probes and prompts (de Leon & Cohen, 2005) to boost discussions about particular topics that were related to this research and it’s raised questions. The materials I have used to trigger responses include, but are not restricted to, objects, photos, and newspaper articles (some of them used in this research for the analysis of discourse). I have relied on the materials always with the awareness that I was allowing the interviewees to take the control of their interview (ibid.) and the materials were only used if needed and for the creation of a trust environment between the researcher and the interviewee. The interviews, then, have enriched the conversation towards the second research question of this thesis – how do Chilean inhabitants perceive the recent activist demonstrations in Chile and what reflections do they have regarding the relationship between such movements and their own society?

Finally, the semi-structured sedentary interviews served for the answering of both research questions raised at the beginning of this research, even though they play a primary role as tools for addressing the second main question raised in the aim section. I have conducted, on total, 12 interviews (mostly with Santiago de Chile residents but also with a person who lives in Valparaíso, a city located about 120km north from the capital), and the interviews had a time range of 35 minutes to one hour and 43 minutes.

2.4. Role of the Researcher

In qualitative research, the researcher is considered to be an instrument of the data collection (Denzin & Lincoln, 2003) as the exchange of information happens through the researcher’s contact with sites and people. In order to strengthen the reliability of this research, I have sought to provide the final material with in-dept descriptions of relevant aspects of the research processes, such as the analysis of the data, interviews, discourses analysis, and theoretical framework as well as information of my own self under the researcher position to qualify my abilities to conduct this research without any biases and pre assumptions of final results (Greenbank, 2003).

Considering that I am not a Chilean citizen, I play the role of a researcher from an ethic – or outside – view, assuming the position of an objective viewer (Punch, 1998). I try to overcome the limitation of being in this place by giving emphasis and bringing to discussion local perspectives of the studied phenomenon through Chilean academic scholars as well as Chilean mediatic productions and inhabitants' points of view. This outsider role, however, can vary between insider and outsider – as Juanita Sundberg (2005, p. 21) already pointed out, being a woman conducting critical geography in Latin America, a field within “only white hetero-sexist males was seen as capable of achieving rationality” can be problematic for a feminist researcher as myself since the production of knowledge is naturally an embodied process and any researcher, just for being alive, will always see through “lenses that are shaped by gender, race, class, and geographical location”. As the revealing of social and geographies of others without the unveiling of our own reproduces an asymmetrical relationship with the subject of study (ibid.), I have also kept a research journal in which I took notes on my personal reflections and insights about the research processes and some thoughts have been exposed throughout this thesis discussion.

14 This chosen researcher position takes basis on a reflexive research practice, as I recognize that the reality portraited in this thesis does not represent the “mirror reality” of Chile, Santiago de Chile, and it’s social movements and the discussion brings together a specific reality that is shaped through the use of defined concepts and theories (Wijsman & Feagan, 2019). I have tried to make use of reflexivity during the whole process of thesis-making as I understand that knowledge production, in a broad sense, is developed towards certain positionalities and situatedness and also because the researcher reflexivity boosts the research to “recognize the knowledge of others in more complex ways” as well as “brings explicit attention to how the researcher personal knowledge and the knowledge of the collectives shape the process and content of the research practice” (ibid., 74).

In regard to validity, or the degree to which the researcher statements approximate to the truth (Punch, 1998), I committed myself as a researcher to always be fully transparent about how the research practices took place, how the scope was defined and under what reasons, as well as to produce a full transcription and integral description of empirical materials. All the tools and software I have used are described in this thesis, as well as how and where I have stored all the data for the construction of this research. Lastly, validity can also be reinforced by the knowledge of the researcher towards the studied place and the particular community and as I am aware that theorizing the subject from a classroom is totally different than living within and seeing the nature of the subject (Ward, 2017), I have been in constant communication with my three main contact persons in Chile who have helped me throughout the whole process of this thesis, from discussing about their own perceptions of the Chilean society in general to new occurrences of protests and what they were witnessing in their everyday life in Santiago de Chile.

2.5. Research Methodological Limitations

The whole idea of this thesis’ topic, as well as the chosen case study, were defined in January 2020, when the world pandemic wasn’t established yet and the Covid-19 was just spreading in Asia and some cases started to appear in the United States (Taylor, 2020). At that time, I have shaped my research with the aim to base my analysis in an ethnographic-inspired methodology and I was deeply dependent on my planned fieldwork that was scheduled to happen at the end of March. One week before my travels, however, Denmark closed its’ borders (Nikel, 2020) and only five days later Chile was also closed to visitants (La Tercera, 2020). I have tried to postpone my fieldwork to the end of May with the hope that the pandemic would settle down and it would be safe to travel internationally from Europe to South America. At the moment I am writing this text, however, Chile is still with its’ borders closed3. As a researcher, I, then, had to readapt the

methodology of my thesis as well as its’ theoretical framework in order to be able to conduct research in a fully long-distance model.

The methodological limitations of this thesis, therefore, are related to the challenges of practicing research from outside the case study site and in an internet-based situation. All the semi-structured interviews were made through either Zoom4 or Skype5 in a process where I would record videos

of my interactions with the interviewees for future transcribing the interviews. I have consistently tried to establish contact with the grassroots organizations involved in the protests but, unfortunately, I didn’t have any success hearing back from them – most of them did not reply to a

3 June 25, 2020 4https://zoom.us/

15 first contact and some that replied explained that interviews were only given in-person. The best way I found to overcome these challenges was to get as much in touch with the interviewees as I could. Interacting digitally with someone you have never seen can be a bit intimidating, especially if you are going to share personal details of your life, so, as a researcher, I tried to spend as much time as the interviewees were willing to, talking about life, Sweden and Chile cultural differences, my professional journey until now, and similar things before the interviews start (Harrington, 2003). I believe in that way they were feeling more comfortable to share their personal views about my study case. This is also why the time of the interviews was relatively long. Finally, to overcome the lack of interviews with the representatives of grassroots organizations, I made sure I would spend some time talking about these organizations and collectives with the inhabitants who were already being part of the interviewees’ group. I feel lucky for being able to really make use of snowball sampling (Bryman, 2016) even in a fully digital environment and I am grateful to every single one of the participants who were posting about my research on Social Media and asking if their friends/followers were willing to contribute with an interview for this thesis.

16 3. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

The goal of this chapter is to present and discuss the theoretical basis of this research. This thesis is built on four different theoretical foundations that frame and contextualize, as well as provide an analytical framework for the 2019-2020 Chilean Uprising study – the theoretical outline is, thus, formed by the Lefebvrian Right to the City, the debates of the neoliberal system from critical urban theory perspectives, the definition of the social movement and activism as a grassroots movement, under the lenses of postcolonial and decolonial theories. The synergy of these theories as well as their relationships with the case study of this thesis is deliberated below. 3.1. Postcolonial and Decolonial Lenses

Primarily, this thesis relies on the analysis of the most recent Chilean social movement towards a postcolonial lens, to both understand the consequences of colonial repressions throughout history and to serve as a counterpoint for the debate and application of all the other theories mentioned and explained above. I refer to the contraposition of postcolonial and decolonial theories towards Western theories because, as Noxolo (2017) asserts, the history of academic studies in geography represents the whiteness of the post colonies in a model where there is no openness to difference and diversity in the knowledge production. A postcolonial and decolonial view brings the focus on how the colonial past is still active in the inequalities and social reality of the present (ibid.). Further, knowledge is not and cannot be conceived as “universal” since its production has a close relation to power forces and to time, location, and conditions of production (c.f., e.g., Noxolo, 2017; Quijano, 2007; Roy, 2016).

This conception of an universal knowledge production is ascribed as a Eurocentric manner of studying societies in a process where there is a high tendency to “convert local history into a global design” (Castro-Gómez, 2008), moreover, this traditional form of viewing the knowledge labels the European culture as the ‘rational one’ that is elaborated as part of a power structure involving European colonial domination over the rest of the world, a process called as the ‘coloniality of power’ (Quijano, 2007) that continues to exist in the contemporary times. Postcolonial and decolonial theories, then, play a key role for the comprehension of elements of social life that cannot be unified to dominant discourses and structures, enabling the research to approach the historical differences belonging to part of a culture that reproduces Eurocentrism by allowing the investigation to undertake a political economy with attention to historical variances and, lastly, relying on both theories is crucial to look upon Global South investigations as the processes of decolonization in post-colonial countries are not over yet (Roy, 2016b).

Regarding Latin American history, Grosfoguel (1996) explains that, in this territory, the idea of progress has been historically connected to “the new”, what is considered as good and desired. This mentality was developed throughout the years and emerged with the developmentalist ideology that is still present in Latin American countries nowadays and that, later on, evolved into modernity ideology and the implementation of neoliberal policies. He explains that the developmentalist debate arose as an outcome of the capitalist world-economy and such ideology was embraced and tailored by the elites in the 18th century to attend their own agenda, by protecting

non-capitalists forms of coerced labor and racial hierarchies. The capitalist society in Latin America, thus, did not have the same path as the European because of the “feudal” background of the Spanish colonialism. Between the 1950s and the 1970s, when the world had an imminent redistribution of power, Latin America was facing military dictatorship governments that were financed and supported by hegemonic states – a period Grosfoguel sees as the destruction of

17 several Latin American democracies and, therefore, he argues that “any discussion concerning the success of neoliberalism in Latin America has to be linked to the historical defeat of antisystemic movements” (ibid., p. 138) from the dictatorship times, as the neoliberal system was implemented under a controlled democracy from above. Further, after re-democratization, in the 1980s, there was a broad recolonization of the periphery by the core, privatization, re-concentration of power and economy, high unemployment, poverty, and misery rates (ibid.).

The Latin American territory is structured by violence and colonial power relations (Halvorsen, 2019) and all these historical nuances of Latin America play an important role in the emergence and solidification of the 2019-2020 Chilean demonstrations. The Chilean dictatorship government and the Chilean colonial period, for instance, were continuously mentioned by the interviewees, both as moments from the history that shaped the current Chilean society as well as times that are still alive in the imaginary of its’ citizens. Looking at history through a critical and postcolonial perspective is, then, vital for an in-depth evaluation of the whole 2019-2020 Chilean social movement – its social representation, strength, and claims.

Finally, I follow the idea of Ananya Roy when she says that “postcolonial theory is a way of inhabiting, rather than discarding, the epistemological problem that is Eurocentrism” (Roy, 2016, p. 205). Thus, I choose not to eliminate the use of Western and Eurocentric theories for the analysis of a case study from the Global South, rather, I try to build integration between these already established and worldwide used theories together with the historical considerations and power relations belonging to a post-colonial state.

3.2. A Critical View of the Neoliberal System

The neoliberal debate is essential to this thesis especially because of the location in which the case study takes place – Santiago de Chile. As previously mentioned in the Introduction chapter, neoliberalism plays an important role in modern societies, as it is a hegemonic form of city governing based on economic and political production of capital accumulation that happens through the diminishing of state services and increasing of business operations and public-private partnerships (see, e.g., Brenner & Theodore, 2002; Harvey, 2005; Swyngedouw, 2009; Žižek, 1999). This concept will be continuously mentioned during this thesis and it will be closely debated within its relationship with the analyzed case in the next chapter, where I present the case study I am reflecting upon in this research material. But first, I would like to dig into the neoliberal system’s definitions and views in the critical urban theory field.

Firstly, when I classify the neoliberal form as hegemonic, I rely on Gramsci's (1989) reflections upon hegemony, when he argues that it is how governments and ruling classes sustain their domination underneath capitalist models. Capitalism here functions as a common interest and its’ constructions are portraited as universal with the aim to reinforce the imagery of a non-ideological status quo (ibid.). Hegemonic neoliberalism is, then, the dominating and powerful approach of modern societies, in which all the connections, productions, relationships are dependent of this ‘common sense’ and its norms (Roseberry, 1994) and the neoliberal hegemony emerges in the contemporary world as a political mode of governing cities (Swyngedouw, 2009b; Žižek, 1999), a model that relies on widespread ‘market solutions’ for all the problems emerging in different societies and economies (Peck & Tickell, 2002). Thereby, neoliberalism transverses the whole society, as it affects the ones at the bottom as well as the ones at the top structures of civilizations (Tyler, 2015). But the way the model affects each citizen is totally different and codependent of the position each one of them occupies in the society, as in a neoliberal system, the positions of

18 power are highly connected to the economic, cultural, physical, and social outcomes in a model that is founded by the principle of the exploitation of the many by the few (Harvey, 1976).

The universal form of the neoliberal hegemonic system (and its marketization solutions) is not built to resolve rooted social problems that are historically attached to the development of cities and civilizations, to the contrary, it generates and reinforces the challenges for the horizontal expansion of societies, with the diffusion of gentrification, segregation, capital accumulation, misery, inequalities, and dispossessions (see, e.g., Baeten, 2017; Brown, 2015; Casgrain, 2014; Harvey, 2003b, 2003a, 2005a; Klaufus, 2013; McGuigan, 2014; Paula Rodriguez & Rodriguez, 2018; Peck & Tickell, 2002; Velicu & García-López, 2018). As the neoliberal form of governance sets individuals and institutions in a position where they have to succumb to the modus operandi of the market system, they are fully and independently responsible for their triumph as well as their defeat, their well-being and their misery (Brown, 2015) since neoliberal governance standardizes the logic of individualism and entrepreneurship in societies, converting citizens into consumers (McGuigan, 2014). Moreover, as David Harvey affirms (2005b), in a neoliberal capitalist system the wealth and power of the few draws on the dispossession of resources of the many, in a process he calls as ‘accumulation by dispossession’. The dispossessed citizens are formed by the people who suffer from the deprivation of land, human rights, and jobs and are exposed to a precarious life, with poverty, debts, and lack of stability (Velicu & García-López, 2018).

Bridging this concept to the case study discussed in this thesis, Santiago de Chile represents the city where the ‘birth’ of neoliberal governance and planning took place for the first time in history. Its model was first implemented in Santiago de Chile in 1973, during the military dictatorship (Caldeira, 2017). The implementation of this system in Chile had a primary aim to bring the country from a peripheral to a semi-peripheral position in the capitalist world-system (Grosfoguel, 1996), which means that, with the neoliberal implementation, Chile would play a political function (rather than just an economical) in the capitalist world, as the country would attend the interests of core states to create semi-peripheral zones that are seen as better than the lower areas (and not worse than the upper sectors) (ibid.). Therefore, the neoliberal development in the Global South is connected to colonial discourses, in which the implementation of a rational system is referred to a ‘salvation’ as this part of the globe is seen as always deficient in relation to the West and always in need of imperialist projects of progress and development (Escobar, 2010).

As widely debated in Latin American critical urban theory, planning inexorably requires a certain standardization of reality that erases difference and diversity, while town planning acts to reifying space and objectifying people (Escobar, 2010) – and this is not an exception from the implementation of neoliberalism in Chile. Urban scholars relate the application of the Chilean neoliberal model with a wild vertical expansion of the city, including the construction of high-rise buildings and the increase of land and housing prices (Kusnetzoff, 1987). In consequence, neoliberalism under the framework of the Chilean society is studied as a system that unfolded spatial segregation, deterioration, and violence in the urban area (Ducci, 1997), as well as the repression of the poor (Wacquant, 2009). Further, developmentalist plans always impact women and indigenous people by destroying their basis for sustenance and survival – and the development models critiques often come from feminist movements, with wom en questioning the system’s dynamics of domination (Escobar, 2010). All of these neoliberal consequences can be seen in Santiago de Chile – the biggest and most important political city of the country. The foundation of such a model in the country will be discussed in detail in the next chapter of this thesis, where I

19 present the Santiago de Chile case and its historical background. But drawing on the neoliberal model is of great importance for the understanding of the development of Chile as well as for the throughout analysis of its society and its power relations.

3.3. The Urban Perspective: “The Right to the City” and Grassroots Movements

The Lefebvrian theory of the ‘right to the city’ (Lefebvre, 1996) and Castells conceptions of grassroots movements (Castells, 1983) work, in this research, as mutually dependent, since I see both ideas as complementary to each other: Lefebvre’s theorization of a city where the citizen is turned into the protagonist is a call for social action and organization of grassroots movements that are well explained and conceptualized, including under the Chilean context, by Manuel Castells. Lefebvre defines the right to the city as a form of contestation of neoliberal urbanism, in which the ‘capitalist city’ generates alienation and segregation, ejecting the lower classes of society from the center to the peri-urban areas in a continuous industrial process of land's privatization, speculation, and appropriation (Lefebvre, 1996). Hence, the demand of this ‘new city’ comes from “those directly in want, directly oppressed, those for whom even their most immediate needs are not fulfilled” (Marcuse, 2011, p. 30), such as homeless people, the ones who don’t have access to food, the ones in prison, and the ones repressed because of their gender, religion, or race (ibid.). The right to the city is, then, a ‘cry for a new city’ (Lefebvre, 1996), a right to have unrestricted access to urban resources – “it is a right to change ourselves by changing the city. It is, moreover, a common rather than an individual right since its transformation inevitably depends upon the exercise of a collective power to reshape the processes of urbanization” (Harvey, 2008, p. 23). Furthermore, Lefebvre advocates that the right to this ‘new city’ can be achieved with the application of four main features: 1- centrality, 2- participation, 3- appropriation, and 4- encounters (Lefebvre, 1996).

According to Lefebvre, centrality would be the resurgence of the social life as a ‘central role’ in the city – the recuperation of the center by the city inhabitants who were once pushed away to the peripheries and to whom the full access to the city center has been denied (ibid.). The right to have access but also to occupy these central spaces and to enjoy them, sparking the promotion of use-value as a substitute for privatization and speculation, and increasing integration in the urban city center. Centrality also means the emplacement of inhabitants into central decision-making processes, with the inclusion of citizens into what is perceived as top-down positions of planning the city (ibid.), often occupied by urban planners and politicians. Participation comes as a complement of this citizens-centrality in the planning process of the city, as Lefebvre advocates that city inhabitants must exercise their right to participate in the decision-making process of city planning in a self-management form in order to avoid the manipulative influence of those in the positions of power in the society and to prioritize the social needs in city development (ibid.). Further, the appropriation feature is defined as the right of re-appropriation of public spaces by the city inhabitants, in a process where the commodification and privatization of public areas are ceased and the people take back their space, time, and desire over spaces, as well as their right to create new spaces (ibid.). Finally, encounters result in what the practice of the three other features generates – the universalization of the city use value to all people (ibid.).

The Lefebvrian “Right to the City” can be seen as a model that stands for the possibility to turn the city into a utopic place (c.f., e.g., Pinder, 2015), and even Lefebvre (1996) mentions that he focuses on ‘the possible’ to, perhaps, reach ‘the impossible’ whereas he refuses to come up with a sharped definition of the ‘perfect’ and ‘ideal’ city. In this thesis, however, I rely on this concept to

20 reinforce the argument that the exercise of the right to the city can be also achieved through citizens being able and empowered to fight for this right (c.f., e.g., Brenner, Marcuse, & Mayer, 2012; Harvey, 2012), bringing the focus to the value of social movements that come from the bottom in order to develop and, eventually, accomplish the ‘right to the city’. Hence, I am inspired by Souza (2010) when he says that the strategies to achieve the “right to the city” under a Latin American context might be taken from a libertarian point of view. As a “contested territory” in which hierarchy and verticality forms are criticized and traditions are not necessarily reproduced but considered as “lessons from the past” (ibid., p. 327) and where horizontality, communes, and networks are tools used to eradicate class exploitation, racism, and patriarchal models. The ‘right to the city’, then, can also be seen in this research beyond its slogan of a gentrification opponent – as the right for an unrestricted and horizontal liberty of thought and action in the society.

Therefore, I interpret the social movement case analyzed throughout this thesis under the lenses of one of the most important academic works on urban social movements (Miller, 2006): Manuel Castells’ The City and the Grassroots (1983). In his book, Castells approaches grassroots movements as a forceful cross-class coalition that is built according to the ‘common grounds’ of collective consumption (that is housing, healthcare, education, public and private transportation, food, and public space) in a phenomenon where people mobilize themselves for the common aim of changing their city and its systems (Castells, 1983).

To justify the importance and existence of urban social movements, Castells explains that society is the structure in which social classes oppose each other in relation to their own social interests, creating a conflictive urban meaning that is based on dominations and resistances to dominations. Additionally, cities are interpreted as the result of these social conflicts together with historical actors – “cities, like all social reality, are historical products, not only in their physical materi ality but in their cultural meaning, in the role they play in the social organization, and in people's lives” (ibid., p. 302). Thus, urban social change is classified by Castells as the redefinition of the urban meaning, and grassroots movements, then, use to have three common goals belonging to the bottom-up demands: 1- to obtain a city organized around its use value and against the notion of urban living and services as a commodity, 2- a search for cultural identity. For the creation of autonomous local cultures. Against the media communication monopoly and the predominance of a one-way information flow and culture standardization, 3- the request of an increasing power for local government, neighborhood decentralization, and urban self-management and against the idea of a centralized state. A fight for a ‘free city’ (ibid.).

Ultimately, Castells asserts that urban social movements have the power to generate societal changes, as long as they consider themselves as urban, or citizen, or related to the city, t hey are locally-based and territorially-defined, and they have the tendency to generate mobilizations towards collective consumption, cultural identity, and political self -management. When these features are not symbiotically-existent within the movements, there is a high chance the movement will be molded into already-existing institutions of society, which will cause the movements’ loss of identities (ibid.).

Furthermore, Latin American authors connect urban social movements as a “response to processes of commodification, bureaucratization and cultural massification of social life brought about by hegemonic formations” (Escobar, 1992, p. 426) and as highly capable of contributing to the redefinition of social justice, basic needs, and democracy. Grassroots movements under a Global South context, then, emerge with a strong anti-imperialist discourse, standing for social and

21 cultural identities and against capitalist struggles, and it is no coincidence that such movements base their strength under the mobilization of women and the youth (ibid.) as they belong to groups that are heavily impacted by developmental plans (Escobar, 2010). Additionally, grassroots movements in Latin America have the ability to empower the people through the creation of alternatives to planning, as criticism and demands toward the state are not always sufficient to change realities (de Souza, 2006). In this way, civil society can pro-actively conceive and implement alternative socio-spatial strategies becoming, then, a powerful actor in urban planning management (ibid.). Urban social movements, thus, act as opposers to technocratic planning, urban neoliberalism and it’s unemployment rates, evictions, lack of housing, and land speculation and as capable providers of a more autonomous society, a free society from foundations of law, norms, and political oppression (ibid.). Finally, the establishment of this intercultural dialogue that confronts universal hierarchies and their power relations can also be interpreted as an attempt towards the ‘decolonization’ of Latin American territories, an endeavor to stop the cycle of reinvention of modern colonial ideas (Halvorsen, 2019).

22 4. CASE PRESENTATION

In this chapter, in addition to presenting the case study of this thesis, which is the 2019-2020 Chilean Uprising, I also portrait the main topics of the Chilean history that are connected to the grassroots movement, relying on some statistics and socio-political backgrounds. It is extremely beneficial for this thesis reader to have a glimpse of the previous phenomenon that potentially triggered the most recent Chilean social movement discussed in this research, therefore, this chapter starts citing main elements of the Chilean colonial period, followed by the geographical context of Santiago de Chile, the first social movement of the country – or the squatters movement of Santiago, and the throwback of the main protests of the past decade.

4.1. The Chilean Big Picture – history, society, and statistics

The Republic of Chile is a South American country that occupies a long and narrowed coastal strip that goes from the Andes mountain range to the Pacific Ocean – a total of 756,945 square kilometers, bordering Peru, Bolivia, and Argentina (Google Maps, n.d., Accessed 3 March 2020). The country has a total population of 19 million inhabitants and, among South American states, it is considered to have the highest human development index (a total of 0,843) (INE, 2017). Such a score is attributed to its economic system that is mainly focused on the exportation of products and has deep liberal and neoliberal influences. Its geographical range is divided amongst 15 administrative regions, except for the capital, the metropolitan region of Santiago de Chile. Its history is marked by the Spanish colonization of, mainly, the Mapuche native people who are, until nowadays, the most present native group in the country in terms of number and one of the most important groups in the Chilean social movements for, among other claims, the access of land and human rights (c.f. Cabalin Quijada, 2014; Toso, 2011).

Figure 3 Mapuche native people protesting against the violation of human rights and for the end of neoliberal exploitation. News Front. (2019, November 18) Retrieved from

23 Santiago de Chile, the chosen city for this case study, plays an important role in all historical background of the country – from colonial times to nowadays’ citizens demonstrations – as it now sits where the Mapuche originally established in colonial times (and where they still fight for social justice in the contemporary world) and also because it is the berth of the countries’ politics, representing the main area where all financial and political systems function in the country. Santiago de Chile is the capital of Chile as well as its administrative center. The city is also the greatest urban agglomeration of the country, with a population of around 7 million people (INE, 2017) (see Figure 4 for a geographical situation). The formation of Santiago de Chile as an urban conglomerate was greatly influenced by the military dictatorship times (1973-1990) and the subsequent neoliberal planning implementations as, under the principles of the National Urban Development Policy of 1979, the city was forced to grow vertically through the construction of several skyscrapers, spreading from 36,000 to 100,000 hectares (Kusnetzoff, 1987).

Figure 4 Map of Chile with the city of Santiago de Chile highlighted. Image extracted from Google Maps.

https://www.google.com/maps

Although Chile is considered one of the most economically stable countries of South America, and Santiago de Chile as one of the most competitive cities of the region, the rates and statistics do not represent the social tensions prevailing among its citizens for almost a decade. The economic development of the country is not questionable, but its social inequality is one of the main reasons for all the riots reported in the media nowadays. Moreover, in the United Nations report on inequalities in human development (UNDP, 2019) that was briefly mentioned in the introduction chapter of this thesis, Chile is categorized as a country that is historically unequal in terms of income and a place where the progress accomplished throughout the years are not reaching all social groups and territories in an equal way. The consequences of the rapid urban development from the dictatorship times, such as the increase of land, housing prices, and speculations, as well as segregation and suppression of the poor (Kusnetzoff, 1987) can still be observed today. This is why the UN highlights the importance of a comprehensive analysis of the Chilean case, in which

24 not only the economic data is examined but also the human development overall view (UNDP, 2019).

4.2. Grassroots movements emergence in Santiago de Chile

Besides the natives’ fights against the destitution of their land and human rights, which is an ongoing process since the colonization period, one of the first grassroots movements in Chile happened before the military dictatorship, in the late 1960s – the squatters movements in Santiago de Chile. The emergence of grassroots movements in the country is connected to the structures and social dimensions of the area, since the uneven development of Latin America has triggered the implementation of an international division of labor, forcing mill ions of people to live in physical and social lower conditions that are now categorized in human geography as urban marginality and urban informality (Castells, 1983). The social structures of Chile in the 1960s was the big spark of the squatters movement, as the social change actions came from the marginal sectors of the country. Marginality, in that sense, meant the inability of the economic system as well as the state policies to provide housing and urban services to an increasing number of urban dwellers, including the regular employees and salaried citizens (ibid.). People who were marginal to society, then, were not necessarily unemployed, inactive, either working in the informal s ectors. The squatters movement in Santiago de Chile happened between 1965 and 1973 and was closely connected to class struggles, being characterized by informal invasions6 of urban land that were

initiated after the creation of a homeless committee (Comites Sin Casa) with the aim to force the government to provide housing and urban services for the ones in need. A new form of settlement was, then, established (the campamentos) founded on the illegal invasion of land (Castells, 1983). The movement has proven its’ organizational capacity throughout the years with the ability to obtain housing and services from the Ministry of Housing with the consented reallocation of 1600 families to 86 hectares of legal urban land. The Chilean government developed policies towards the settlements between 1970 and 1971 when the president at that time (Salvador Allende) had no other option but the acceptance of the ‘illegal’ settlements’ existence and started providing elementary services by connecting the squatters to public agencies for the creation of an active collaboration within the administration. That was also the time when the squatters movement came to an end as an identifiable, organized, and structured entity. The campamentos, however, are recognized as a mode of urban social movement due to the involvement of popular masses around urban issues, making political contributions for a societal change (ibid.).

One of the responses to Salvador Allende politics in Chile was the implementation of a military dictatorship that took place in 1973 with the leading of Augusto Pinochet through a coup d'etat. The dictatorship (1973 – 1990) was one of the most violent of South America in the 20th century with the left-wing leaders as well as government opposers being incarcerated in seclusion centers and detention and torture camps (Francisco, Fuentes, & Sepúlveda, 2010). One of the long-lasting outcomes of the dictatorship was the creation and implementation of a neoliberal economic, governmental, and planning systems that are still present in the Chilean society (Biblioteca Nacional de Chile, n.d.). The model was produced underneath a “shock policy”, with the formation of a group of young economists (the “Chicago Boys”) who, with the political support of the United States government and the aim to bring Chile out of an economic crisis, developed a neoliberal

6 For a matter of contextualization, Manuel Castells makes use of the term ‘invasions’ to represent informal occupations in a

book that was published in 1983, a time when the wide debates on informality and dichotomic discourses of legal versus illegal were not as present in the field of Urban Studies as nowadays.

![Figure 5 Picture of the Largest March of 2019. BBC. (2019, October 26). “En redes sociales, la manifestación fue convocada como ‘La marcha más grande de Chile’” [digital image]](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/5dokorg/4032808.82542/27.918.236.684.700.956/figure-picture-largest-october-sociales-manifestación-convocada-digital.webp)