J

Ö N K Ö P I N GI

N T E R N A T I O N A LB

U S I N E S SS

C H O O L JÖNKÖPING UNIVERSITYC o o p e r a t i o n i n t h e D i s t r i b u t i o n

C h a n n e l

Determinants of inter-organisational cooperation between suppliers and servicing

dealers in the Swedish outdoor power equipment market

Paper within Bachelor Thesis Author: Benjamin Risom

Johan Olsson Jonas Magnusson

Bachelor Thesis within Business Administration

Title: Cooperation in the distribution channel;Determinants of inter-organisational cooperation between suppliers and servicing dealers in the Swedish outdoor power equipment market. Authors: Magnusson, Jonas

Olsson, Johan Risom, Benjamin

Tutor: Holkko Lafourcade, Johanna Date: May 2011

Subject terms: Relationship marketing, Distribution channels, Inter-organisational coop-eration, Commitment trust theory, Swedish outdoor power equipment mar-ket

Abstract

For manufacturing suppliers, careful handling of business relationships with dealers is an essential function required for business success. End consumers rely on deal-ers for product information, advice and after sales support; all of which being fac-tors capable of enhancing their perceived value of the product. The importance of the dealers for the end consumers implies that it is in the interest of suppliers to manage their relationship with the dealers in a satisfactory manner in order of gain-ing their support and commitment. In the case of suppliers in the Swedish market for outdoor power equipment, managing this relationship with servicing dealers is of great importance to their business success and viability. Successful management of such relationships requires coordination and cooperation. Thus, it is in the inter-est of suppliers to understand how long-term cooperation with dealers can be en-hanced.

Our research focuses on identifying determinants that enhance sustainable coopera-tion between manufacturers and servicing dealers in the Swedish outdoor power equipment market.

A survey was conducted among servicing dealerships in Sweden testing eight hy-potheses developed through an adaption of Morgan and Hunts’ (1994) Commit-ment-trust theory together with an extensive literature review. The results were ana-lysed and tested with correlation analysis.

Trust and commitment were found to be determinants in fostering sustainable co-operation between dealers and manufacturers in the Swedish market for outdoor power equipment. Furthermore, four important antecedents for dealer commitment were identified; supplier commitment, support, termination costs and participation.

Purpose:

Background:

Method:

Table of Contents

1

Introduction ... 1

1.1 Background ... 1 1.2 Problem Discussion ... 2 1.3 Purpose ... 3 1.4 Research Questions ... 3 1.5 Perspective ... 3 1.6 Delimitations ... 4 1.7 Definitions ... 41.8 The Swedish Outdoor Power Equipment Market ... 5

2

Theoretical Framework ... 7

2.1 Perspectives of Interorganisational Performance ... 7

2.2 The Commitment – Trust Perspective ... 8

2.2.1 The Key Mediating Variables (KMV) model ... 8

2.2.2 Mediating Variables ... 9

2.2.3 Antecedents ... 10

2.2.4 Outcomes ... 11

2.2.5 Findings of the KMV model ... 11

2.2.6 Previous Application of the KMV Model ... 12

2.2.7 Critique ... 14

2.3 The Use of the KMV model in our research ... 15

2.4 Presentation of the Conceptual Framework ... 16

2.4.1 Cooperation ... 16

2.4.2 Relationship commitment ... 17

2.4.2.1 Reflection about Relationship Commitment ... 17

2.4.2.2 Relationship Commitment and its Influence on Cooperation – RQ 1 ... 18

2.4.3 Trust ... 18

2.4.3.1 Reflections about Trust ... 18

2.4.3.2 Trust and its Influence on Cooperation – RQ 1 ... 20

2.4.3.3 Trust and its influence on Relationship Commitment – RQ 2 ... 21

2.4.4 Antecedents of Commitment and Trust – RQ 3 ... 21

2.4.4.1 Support ... 22

2.4.4.2 Termination costs... 22

2.4.4.3 Supplier commitment ... 24

2.4.4.4 Participation ... 24

2.4.4.5 Communication ... 25

2.5 Overview of the Generated Framework ... 27

3

Method ... 28

3.1 Deductive research approach ... 28

3.2 Quantitative method ... 29 3.3 Data collection ... 30 3.3.1 Secondary Data ... 30 3.3.2 Population ... 31 3.3.3 Sample ... 32 3.3.4 Survey ... 32 3.3.4.1 Survey structure ... 32 3.3.4.2 Measurement development ... 33 3.3.4.3 Likert scale ... 35 3.3.4.4 Pre study ... 36

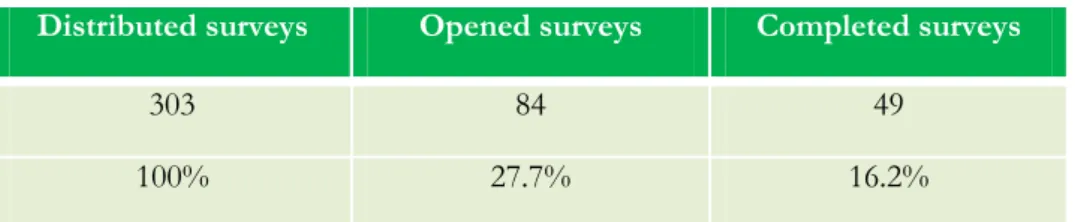

3.3.4.5 Response rate ... 37

3.3.4.6 Non-response bias ... 37

3.4 Reliability and validity ... 38

3.4.1 Reliability ... 38 3.4.2 Validity ... 39 3.4.2.1 External Validity ... 39 3.4.2.2 Internal Validity ... 40 3.5 Data Analysis ... 40 3.5.1 SPSS ... 40

3.5.2 Preparation and cleaning of data ... 40

3.5.3 Statistical Validity and reliability control ... 41

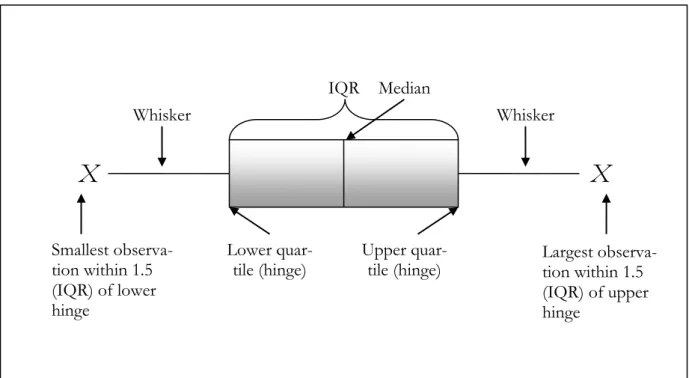

3.5.4 Descriptive statistics ... 41

3.5.5 Correlation Analysis ... 43

3.6 Limitations of Method ... 44

4

Empirical Findings and Analysis ... 45

4.1 Response rate ... 45

4.2 Non-response bias ... 45

4.3 Data cleaning ... 46

4.4 Data characteristics ... 46

4.5 Reliability and validity of measures... 49

4.6 Construct and Item summaries ... 50

4.6.1 Participation ... 50 4.6.2 Supplier Commitment ... 52 4.6.3 Termination Cost ... 55 4.6.4 Support ... 57 4.6.5 Communication ... 59 4.6.6 Relationship Commitment ... 61 4.6.7 Trust ... 63 4.6.8 Cooperation ... 65 4.7 Hypothesis Testing ... 67 4.7.1 Research Question 3 ... 68 4.7.1.1 Hypothesis 8 ... 68 4.7.1.2 Hypothesis 7 ... 70 4.7.1.3 Hypothesis 6 ... 72 4.7.1.4 Hypothesis 5 ... 74 4.7.1.5 Hypothesis 4 ... 76 4.7.2 Research Question 2 ... 78 4.7.2.1 Hypothesis 3 ... 78 4.7.3 Research Question 1 ... 80 4.7.3.1 Hypothesis 2 ... 80 4.7.3.2 Hypothesis 1 ... 83 4.8 Overview of results ... 85

5

Conclusions ... 86

6

Managerial Implications ... 87

References ... 88

Appendix ... 97

Appendix D: Cover Letter English Version ... 122

Appendix E: Mann-Whitney U-test ... 123

Appendix F: Item-Total correlation statistics ... 124

Appendix G: Correlation Matrix ... 125

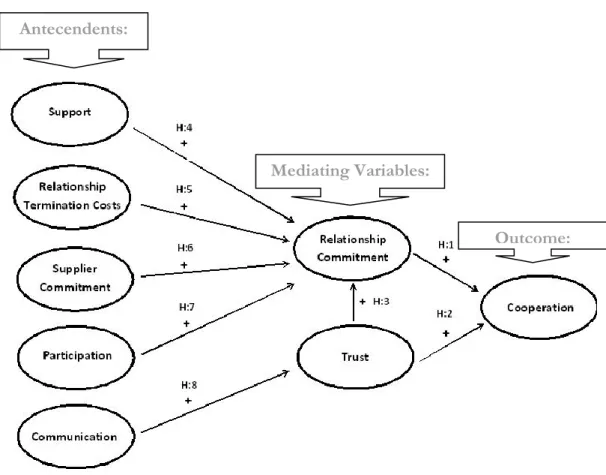

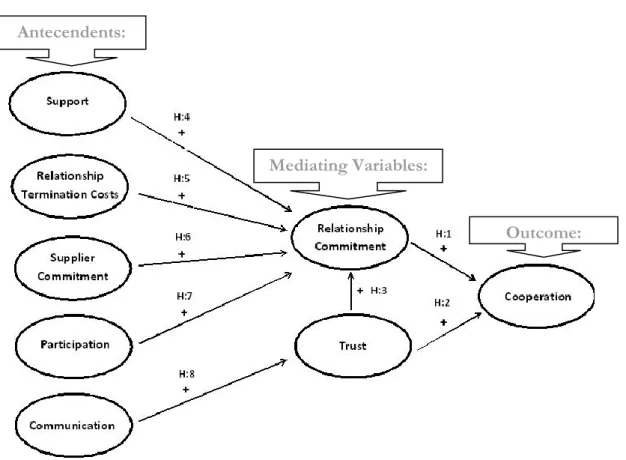

Figure 1. The KMV model by Morgan and Hunt (1994) ... 9

Figure 2. Conceptual framework in this research. ... 16

Figure 3. Overview of Conceptual Framework ... 27

Figure 4. Specification of Population ... 31

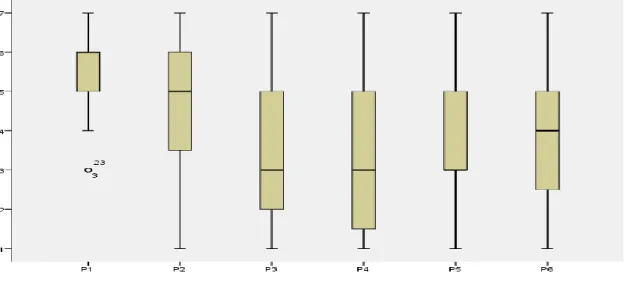

Figure 5. Description of Box Plot ... 42

Figure 6. Level of knowledge indicated by SQ1 ... 46

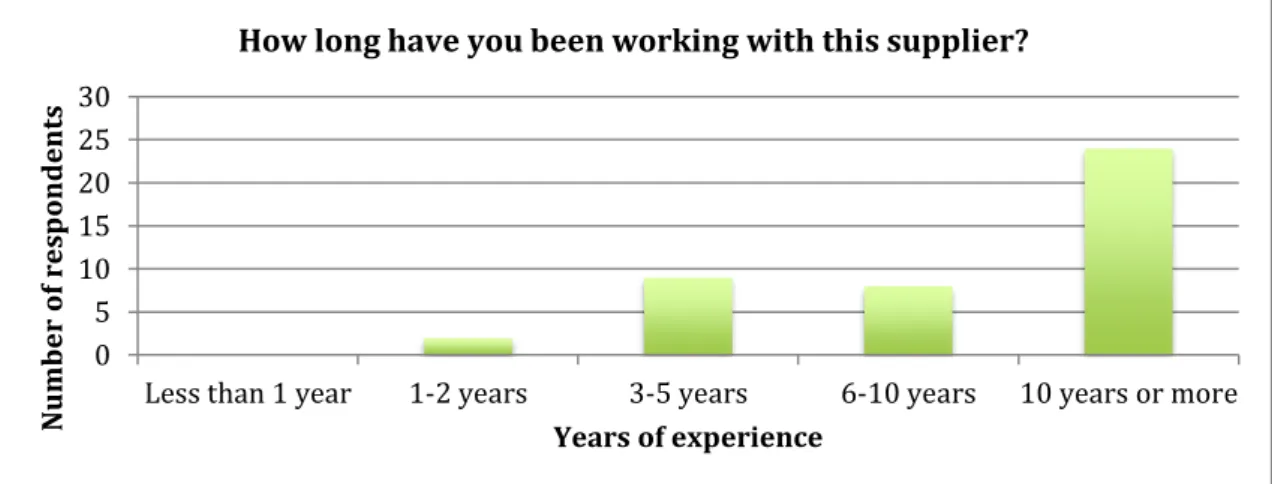

Figure 7. Dealer experience with main supplier as indicated by SQ2 ... 47

Figure 8. Respondents experience with main supplier as indicated by SQ3 ... 47

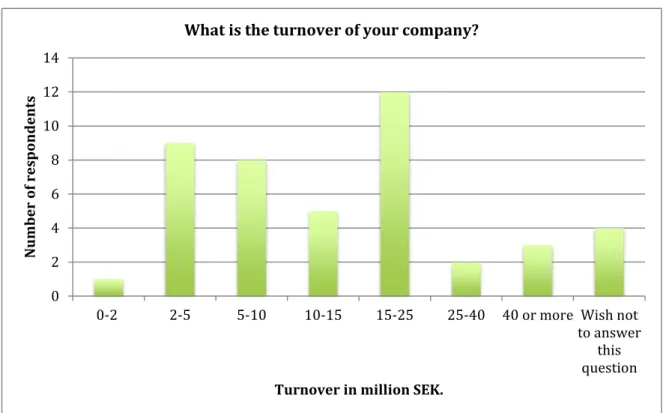

Figure 9. Dealer turnover as indicated by SQ5 ... 48

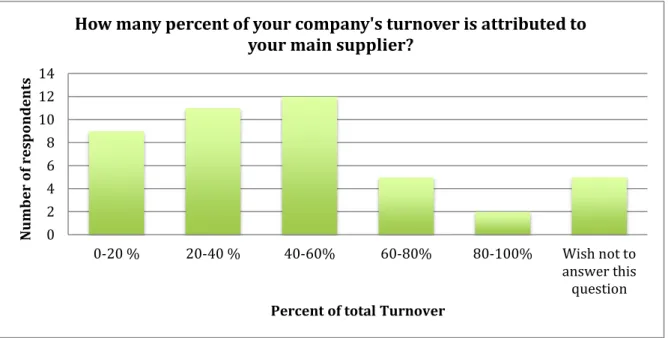

Figure 10. Main suppliers share of total Turnover as indicated by SQ6 ... 49

Figure 11. Pie Chart Participation ... 51

Figure 12. Box Plot Participation ... 52

Figure 13. Pie Chart Supplier Commitment ... 53

Figure 14. Box Plot Supplier Commitment ... 54

Figure 15. Pie Chart Termination Costs ... 55

Figure 16. Box Plot Termination Costs ... 56

Figure 17. Pie Chart Support... 57

Figure 18. Box Plot Support ... 58

Figure 19. Pie Chart Communication ... 59

Figure 20. Box Plot Communication ... 60

Figure 21. Pie Chart Relationship Commitment ... 61

Figure 22. Box Plot Relationship Commitment ... 62

Figure 23. Pie Chart Trust ... 63

Figure 24. Box Plot Trust ... 64

Figure 25. Pie Chart Cooperation ... 65

Figure 26. Box Plot Cooperation ... 66

Figure 27. Overview of correlations coefficients for Hypotheses ... 67

Figure 28. Hypothesis 8 ... 68

Figure 29. Scatter plot Hypothesis 8 ... 68

Figure 30. Hypothesis 7 ... 70

Figure 31. Scatter plot Hypothesis 7 ... 70

Figure 32. Hypothesis 6 ... 72

Figure 33. Scatter plot Hypothesis 6 ... 72

Figure 34. Hypothesis 5 ... 74

Figure 35. Scatter plot Hypothesis 5 ... 74

Figure 36. Hypothesis 4 ... 76

Figure 37. Scatter plot Hypothesis 4 ... 76

Figure 38. Hypothesis 3 ... 78

Figure 39. Scatter plot Hypothesis 3 ... 78

Figure 40. Hypothesis 2 ... 80

Figure 41. Scatter plot Hypothesis 2 ... 80

Figure 42. Hypothesis 1 ... 83

Figure 44. Overview of results ... 85

Tables

Table 1. Item Adaption ... 34Table 2. Response Rate ... 45

Table 3. Reliability and validity as indicated by Cronbach alpha ... 49

Table 4. Median & Mode of Participation ... 52

Table 5. Median & Mode of Supplier Commitment ... 54

Table 6. Median & Mode of Termination Cost ... 56

Table 7. Median & Mode of Support ... 58

Table 8. Median & Mode of Communication ... 60

Table 9. Median & Mode of Relationship Commitment ... 62

Table 10. Median & Mode of Trust ... 64

1

Introduction

This chapter provides the background to the subject as well as the underlying problem that will be dealt with throughout the thesis. Based on the background and problem, we also define the purpose of the research, the research questions to be covered as well as the delimitations of our work. Finally, a section is included that describes the characteristics of the market that is investigated.

1.1 Background

In today’s business environment, distribution channels gain more and more importance since customers require increasing support, like advisory service during their purchase and after sales support, in order to maximise the obtained value of their purchase (Goffin, 1999). Often, the support demanded can only be efficiently provided by servicing dealers since they possess unique knowledge of local market conditions and have established close personal contact with the local customer base, thus allowing them to respond instantly to changing customer needs and expectations (Collins, 1992).

According to Kraft and Mantrala (2006), customer orientation is of special importance in high-price markets with premium products. The Swedish outdoor power equipment market is characterised by these conditions as products can be seen as investments due to their longevity and high-pricing. This also explains the increasing importance of servicing dealers within the market, as the target consumers require excellent after-sales support in regards to maintenance and repairs (Husqvarna Annual Report, 2010). The market is estimated to have an annual value of 2.5 billion SEK, with marginal growth of only two percent per an-num. In such slow-growth markets it is advisable to focus on customer orientation in order to achieve a high customer retention rate, which in turn will give a competitive edge to firms as their revenues are safeguarded against the attempts from competitors to steal mar-ket share (Fornell, 1992). Therefore, the entity responsible for directly interacting with the end-customer, needs to be motivated and dedicated to satisfying market expectations (Col-lins, 1992). In the case of the Swedish outdoor power equipment market, this entity is rep-resented by the servicing dealers, who preferably should be supporting the manufacturers’ objectives.

This highlights the need for better cooperation between manufacturers and servicing deal-ers in order to achieve better service levels and the desired customer orientation (Fernie & Sparks, 2004). According to Gummesson (2002), cooperation is the core concept in man-aging these relationships as it creates mutual value increases for the involved parties.

Scholars argue about how this cooperation can be achieved. El-Ansary and Stern (1972) state that power, as the ability to control the other entity, is the central concept in order to encourage distribution channel members behaviour towards enhanced cooperation. This approach is widely represented in the academic research field. Dant and Young (1989) identify one hundred and nineteen studies which address the role of power in managing and monitoring channel members’ behaviour.

Opposing the paradigm that power is the main source of efficient partnerships, Kumar (1996) holds the opinion that the use of power will be self-defeating. Instead Kumar (1996) suggests that trust and an intrinsic motivation of acting in a partner’s interest are needed in order to achieve long-term benefits and exploit the full potential of partnerships. Related to this, academic research has also focused on the role of commitment in the successful func-tioning of relationships (e.g. Anderson & Weitz, 1992; Morgan and Hunt, 1994)

Kumar, Hibbard and Stern (1994) analysed the impacts of commitment on desirable out-comes for the firm. They stress that commitment should be generated by attracting the dealer, rather than by creating “lock-ins”, either by obligation or the degree of investments already made within the relationship. Partners who are attracted to the manufacturer will therefore perform better than those who feel that they need to stay in the relationship due to exerted power or dependence.

1.2 Problem Discussion

As Fox and Sethuraman (cited in Kraft & Mantrala, 2006) denote, manufacturers are de-pendent on the servicing dealers in order to reach their desired market coverage. As such, these stores can be optimised to target a smaller number of customers more efficiently with regard to their knowledge of local market conditions. On the other hand, dealers are de-pendent on the manufacturers’ products due to their brand recognition and the accompa-nied demand from end-customers (Glynn, Motion & Brodie, 2007). This mutual depend-ence creates incentives to coordinate actions since decisions by one channel member will impact on the performance of the partner, especially on the generated profits (Jeuland & Shugan, 1983).

As suggested by Hunt and Nevin (1974), this coordination should not be achieved by exer-cising coercive power, but rather by enhancing cooperation. This should lead to higher dealer satisfaction with the relationship and foster a will to perform in the interest of the manufacturer. In the Swedish outdoor power equipment market it is thus vital for manu-facturers to handle the relationship with servicing dealers through policies and actions that enhance cooperation. The problem arises, which factors and actions fulfil the desired ob-jective of enhanced cooperation, a challenging managerial task to solve.

The fact that these dealers have their own business objectives and might engage in oppor-tunistic behaviour aggravates the task further, since unsatisfied dealers might neglect the partnership and cease to support the manufacturers products (Fernie & Sparks, 2004). Ac-cordingly, flawed relationships with dealers can harm the manufacturers business by losing a customer in the long run, as the quality of the relation to the dealer could decide which manufacturers’ brand a customer will be directed to by the dealer (Neese, 2004). Thus it is in the interest of manufacturers to understand how cooperation, as a trust-based, intrinsic motivation of dealers to support the manufacturer in the long-run, can be enhanced. Committed dealers will be more reluctant to dissolve the relationship, which should allow a profitable return on the resources dedicated to the relationship by the manufacturer.

Addi-enhanced assistance in developing loyalty among end customers and a decreased interest among dealers to support competitor brands (Anderson & Weitz, 1992).

As Mehta, Polsa, Mazur, Xiucheng and Dubinsky (2006) demonstrated, enhanced coopera-tion can also increase manufacturer’s satisfaccoopera-tion with the relacoopera-tionship. This might lead to an improved willingness among manufacturers to share the heightened total channel profits with the dealer (Jeuland & Shugan, 1983). In addition, better cooperation will create a posi-tive spiral mechanism in regard to the mutual commitment of the two parties. Thus, higher dealer commitment should increase the manufacturer’s commitment and the bonding ef-forts can in turn also improve the margins and the turnover of dealers, increase customer satisfaction and lead to differentiation from their competitors (Anderson & Weitz, 1992). Subsequent to the previous argumentation, we propose that it is of pivotal importance to truly understand which factors enhance cooperation in distribution channel relationships. Intrinsic to this, is the realisation of the potential revenue growth obtained from higher channel performance and the actualisation of the partnerships’ full potential.

1.3 Purpose

Our research focuses on identifying determinants that enhance sustainable cooperation be-tween manufacturers and servicing dealers in the Swedish outdoor power equipment mar-ket.

1.4 Research Questions

1. How do commitment and trust impact on cooperation between dealers and suppliers? 2. How does trust from dealers impact on their commitment towards suppliers?

3. Which actions and factors influence the degree of commitment and trust from dealers towards suppliers?

1.5 Perspective

This research approaches the problem of better cooperation in the relationship between suppliers and dealers from a supplier perspective. Thus, we investigate how suppliers in the market can enhance cooperation as perceived by their dealers. This is reasonable since, ac-cording to Jap and Ganesan (2000), it is mainly initiatives by suppliers that give the impetus for shaping the nature of the relationship. Furthermore, they denote that the higher the dealer’s perception of the supplier commitment, shown through supportive actions and in-vestments in the relationship, the higher the satisfaction of the dealer with the relationship. This increased dealer satisfaction is found to lead to higher degrees of cooperation and in turn fosters a long-term orientation in the relationship (Hunt & Nevin, 1974; Ganesan, 1994).

1.6 Delimitations

Our research will be conducted in a very specific setting as the Swedish outdoor power equipment industry possesses characteristics which might not be found in the same ar-rangement as in other industries. Therefore, the generalisability of the results is limited even though implications for manufacturer-dealer relationships in other industries could be given. Furthermore, the research evaluates dealer’s perceptions of the relationships and thus a complete view of the relationship is not provided as this would also entail an investi-gation of supplier’s perceptions. Dealer’s behaviours and actions also contribute to a func-tioning relationship but were intentionally disregarded in order to isolate the impacts of manufacturers’ actions. Lastly, this paper analyses the enhancement of cooperation from a commitment and trust perspective as suggested by Morgan and Hunt (1994). As authors, we are aware that several other factors may influence the degree of cooperation, but within the scope of this thesis, a restriction had to be made in order to guarantee a deeper under-standing of the chosen perspective.

1.7 Definitions

Outdoor power equipment: Outdoor power equipment in this context refers to trim-mers, chainsaws, lawnmowers, hedge trimtrim-mers, and brush cutters.

Servicing dealers: In the Swedish outdoor power equipment market, the word denotes what is known as a specialised retailer in the academic community. A specialised retailer sells the products to the consumer and offers a specialist product range with a high degree of customer service and personal advice (Sonneck & Ott, 2006 cited in Kraft & Mantrala, 2006). In this paper the word servicing dealer or dealer will be used accordingly in order of facilitating the comprehension, and to enhance the readability of the thesis.

Manufacturer: This term refers to an entity that produces a good through a process in-volving raw materials, components, or assemblies (Business Dictionary, 2011). The final product will then be supplied to consumers via distribution channels. Thus, supplier is used as a synonym for manufacturer.

Cooperation: Coordinated actions of independent relationship partners in order to achieve mutual goals (Anderson & Narus, 1990).

Commitment: Relationship commitment exists when partners in an ongoing industrial re-lationship believe that the rere-lationship is so important as to dedicate maximum efforts at maintaining it (Morgan & Hunt, 1994).

Trust: Trust occurs if one party has confidence in the exchange partner’s reliability and in-tegrity (Morgan & Hunt, 1994).

Antecedent: In this research it relates to the precursors of commitment and trust. Ante-cedents are theoretical constructs or factors which affect the degree of a partner’s com-mitment or trust.

Mediating variable: Commitment and trust are the only two mediating variables used in this paper. This implies that mediating variables are focal constructs which give a better in-sight in explaining the effects of inputs on the outcomes of the relationship. Thus, anteced-ents impact on the degree of commitment and trust which in turn leads to either positive or negative outcomes for the relationship.

Outcomes of relationship commitment and trust: Outcomes refers to factors that shape the nature of the relationship, such as cooperation. This can happen either positively or negatively which will be dictated by the degree of commitment and trust prevailing in the relationship.

1.8 The Swedish Outdoor Power Equipment Market

In the absence of official information gathered by an external party such as Skatteverket or Statistiska centralbyrån (SCB), the following information is collected from annual reports of major suppliers in the market.

The main suppliers in the Swedish outdoor power equipment market are Husqvarna, Stihl, GGP and MTD (Husqvarna annual report, 2010). Outdoor power equipment in this con-text is limited to products within the segments of lawnmowers, hedge trimmers, brush cut-ters, trimmers, chainsaws and respective accessories for those products. This specific mar-ket in Sweden is estimated to have an annual value of 2.5 billion SEK and an approximated per annum growth of two to three percent (Husqvarna annual report, 2010). Due to the application of the products, sales are unevenly distributed throughout the year with late spring and summer marking the periods in which the bulk of the revenue is generated. By screening the market it can be noticed that no vertical integration exists from the sup-plier into the lead of distribution. The two main types of distribution channels are through retailers and servicing dealers. Retailers are chains of stores offering mid to low quality products with price being the most important decision making factor. Whilst servicing dealers mainly offer premium products together with extensive service and after-sales sup-port. At this present time, the proportions are approximately sixty percent sales through servicing dealers and forty percent through regular retailers. However, actors in the market anticipate that over the coming years a considerably higher proportion of sales will be gen-erated through the servicing dealers (Husqvarna annual report, 2010).

The characteristics of a servicing dealer is that they offer extensive expertise in the field, all-encompassing after-sales support in terms of spare and maintenance parts, the ability to re-pair the products and a local presence (Stihl website, 2011). They work towards both pro-fessional users and demanding private customers. To complement their product range and to compensate the seasonal nature of sales within the industry, it is common that they offer other types of products such as All-Terrain-Vehicles and agricultural equipment. Our deal-er screening also shows that a typical dealdeal-er is a small company with few employees. Some efforts are made in the market to consolidate power among servicing dealers and to gain a better bargaining position towards the suppliers, an example of this is Qvalitetscenter, which is a chain that independent dealers can join.

Upon review of annual reports from suppliers in the market, it is obvious that there is a strong focus on developing existing distribution networks especially with regard to servic-ing dealers. For example, Husqvarna explicitly presents strategic decisions aimed at strengthening the relations towards servicing dealers. Those initiatives consist of several service improving mechanisms such as refined sales support and training.

2

Theoretical Framework

The following chapter will give the reader an understanding of the main perspectives surrounding inter-organisational relationships. Further, the theory and chosen model for this thesis is presented along with re-flections, explanations, previous applications and critique. The chapter concludes with a presentation of the developed conceptual framework that will be applied and tested in this research as well as the associated hy-potheses.

2.1 Perspectives of Interorganisational Performance

Interorganisational relationship performance or cooperation can be created in several ways with different underlying reasoning. Palmatier, Dant and Grewal (2007) distinguish be-tween four perspectives that dominate the academic field of understanding successful in-terorganisational relationships: (1) the transaction cost perspective, (2) the relational norms perspective, (3) the dependence perspective and (4) the commitment-trust perspective. The transaction cost perspective offers an explanation for interorganisational performance that is based upon classical transaction cost economics (Williamson, 1975). Researchers such as Heide and John (1990) show that relationship closeness, which comprises of joint actions and expectations for a long-lasting relationship, evolves organically due to the need of safeguarding specific investments and in order to reduce uncertainty within the relation-ship. If the relationship were to be abandoned by one party, relationship specific invest-ments made by the other party may lose its value. This creates a potential for opportunistic behaviour that could harm one of the parties. Consequently, parties collaborate and create bilateral governance structures in the form of joint actions that prevent harmful actions from the partner. Thus, cooperation is enhanced and opportunistic tendencies are damp-ened due to the mutual control over assets implied by joint governance. In conclusion, ac-cording to Palmatier et al. (2007), the degree of specific investments and opportunistic be-haviour influences the governance structure and the performance of the partnership in this perspective.

The relational norms perspective emphasises the importance of norms as a means of shared expectations within the relationship (Kaufmann & Dant, 1992). The better estab-lished these norms are, the more likely the partnership will become a source of competitive advantage and lead to sustainable, value-creating business relations (Palmatier et al., 2007). Such norms may be specified in different ways, according to the respective context. For ex-ample, according to Jap and Ganesan (2000) norms such as solidarity, active information exchange or participation proved to be vital in enhancing the dealers’ perception of suppli-er commitment which in turn leads to highsuppli-er satisfaction with the relationship. Gensuppli-erally, if such norms are well established and strong, they will ultimately enhance cooperative behav-iour and the performance of the relationship (Cannon, Achrol & Gundlach, 2000).

The dependence perspective suggests that interdependence of partners in a business rela-tionship is a driver of performance and affects the way in which conflicts are resolved in a given relationship (Palmatier et al., 2007). Research focuses on dyadic interdependence, which is assessed by the degree of total dependence, comprising both manufacturer and

dealer dependence, and also relative dependence, which reflects the extent to which one party is more dependent than its counterpart (Gundlach & Cadotte, 1994). Hibbard, Ku-mar and Stern (2001) show that the higher the total dependence, the higher the value is that the parties derive from the relationship since their stakes in it are greater. This mutual de-pendence enhances performance since both parties have incentives to work in the interest of the other party. Consequently, as the relationship is perceived to be highly valuable to both firms, they refrain from destructive acts and the exertion of power. Hibbard et al. (2001) further deduces that if the relative dependence increases, manufacturers can exert power and pursue policies which might harm the distribution partner. This is attributed to the awareness that the partner will passively accept most actions since the dependence does not allow for counteractive measures.

The commitment and trust perspective can be traced back to Morgan and Hunt (1994) and serves as the basis for this thesis. With regard to the research made by Palmatier et al. (2007) this is reasonable since the commitment and trust perspective, compared to the oth-er poth-erspectives, was found to be a relatively bettoth-er predictor of financial poth-erformance, co-operation and conflict in the relationship, especially as environmental uncertainty increases. The evaluation of factors that might enhance cooperation against the background of their influence on commitment and trust is reasonable as this perspective proved to be the main mediating force between investments to a relationship and the achieved performance level by the partners (Luo, Liu & Xue, 2009). This perspective has been further acknowledged by previous research and hypotheses throughout academia. Anderson and Weitz (1992) state that committed partners cooperate better and are able to achieve mutual performance enhancements. Additionally, Kumar (1996) proved that trust is essential for long-lasting and beneficial business relationships, and thus commitment should not be separated from trust. The findings and support for commitment and trust as being essential in fostering sustainable inter-organisational cooperation makes the commitment-trust perspective suit-able as a basis for fulfilling our purpose of identifying determinants that enhance coopera-tion. A deeper insight to the commitment-trust perspective will be given in the proceeding section.

2.2 The Commitment – Trust Perspective

2.2.1 The Key Mediating Variables (KMV) modelDeveloped by Morgan and Hunt (1994), the key mediating variables (KMV) model is one of the most acknowledged and cited models of relationship marketing (Morris & Carter, 2005). The model (Fig. 1, p.8) is rooted in the social exchange theory which states that in-dividuals form relationships based on mutual exchange in order to derive benefits from the relationship. While past research focused on power as a determining factor of relationship performance (Dant & Young, 1989), Morgan and Hunt (1994) express the importance of commitment and trust in understanding what distinguishes productive and effective rela-tions from those that are unproductive and ineffective. Like previous researchers (e.g. An-derson & Narus, 1990; Dwyer, Schurr & Oh, 1987) Morgan and Hunt (1994) claim that

trust and commitment are crucial factors in building, developing and maintaining inter-organisational relationships.

The purpose of Morgan and Hunt’s (1994) research was to prove their proposition that the presence of trust and relationship commitment is central to building successful business re-lationships. They demonstrate that the presence of commitment and trust encourages firms to work at maintaining the relationship by cooperating with partners and resisting attractive short-term alternatives in favour of long-term profits. Furthermore, Morgan and Hunt (1994) argue that commitment and trust make firms view potentially high-risk actions as prudent because they are confident that their partners will not act opportunistically.

+ +

+

-+ -+

+ + +

+ +

-

-Relationship Termination Cost Relationship Benefits Shared Values Communication Trust Relationship Commitment Functional Conflict Uncertainty Cooperation Propensity to Leave Acquiescence Opportunitic Behavior

Figure 1. The KMV model by Morgan and Hunt (1994)

2.2.2 Mediating Variables

Morgan and Hunt (1994) contend that trust and relationship commitment are interrelated and key mediating variables of five antecedents and five important relational outcomes as seen above in Figure 1. The direction of the arrows indicates whether the proposed ante-cedents influence the degree of commitment and trust (key mediating variables in Figure 1) or if the two key mediating variables impact on final outcomes of a relationship. Thus, an-tecedents do not influence the outcomes directly, but are mediated by the effects of

en-Antecendents:

Mediating Variables:

hanced commitment and trust. This awareness constitutes the naming of the key mediating variable model which is the core of the commitment and trust conceptualisation.

In this model, commitment represents a belief among the relational partners that the rela-tionship is so valuable as to dedicate maximum efforts at preserving it. Thus, the partners aim at maintaining the relationship on a long-term base. Trust on the other hand reflects the confidence of a partner in the others reliability and integrity. In the model trust is the basis for commitment, since only trust in a partner allows commitment which comes along with a certain risk potential as dedicated efforts might not pay off when the relationship is dissolved. This relation is depicted through the positive arrow from trust to commitment in Figure 1.

2.2.3 Antecedents

Antecedents are precursors of commitment and trust. Morgan and Hunt (1994) identify five crucial factors: (1) relationship termination cost, (2) relationship benefits, (3) shared values, (4) communication and (5) opportunistic behaviour. Relationship termination costs relate to idiosyncratic investments which lead to switching costs when a relationship is ter-minated as these investments lose their value in alternative business relationships (Heide & John, 1988). Morgan and Hunt (1994) denote that the higher these expected losses from ending a relationship, the higher the commitment (Figure 1). The same positive relation holds true for relationship benefits, which are advantages derived from a certain relation-ship with regard to profitability, customer satisfaction or performance (Morgan & Hunt, 1994). Thus, one party is more likely to commit itself to a relationship if the generated ben-efits from the relationship are high, relative to the alternatives. This is shown through the positive arrow between the two constructs in Figure 1.

Shared values is the only antecedent impacting on commitment as well as on trust. Morgan and Hunt (1994) define shared values as common beliefs among the partners with regard to adequate and important behaviours, goals and policies defining the relationship. If these values prevail to a great extent in a relationship, there is a direct positive effect towards commitment as well as an indirect enhancement of commitment through the influence of these values on trust.

The KMV model also displays that if the partners communicate relevant information in a timely, reliable and frequent manner, there will be higher trust in the relationship as con-flicts are solved more efficiently and since demands made on a relationship from the indi-vidual partners can be aligned (Anderson & Narus, 1990; Etgar, 1979). Lastly, there is a negative relation between opportunistic behaviour and trust, meaning that the more oppor-tunistic behaviours are prevailing in a relationship, the lower the degree of trust as seen in Figure 1. Morgan and Hunt (1994) postulate that these violations of expected behaviours not only decrease trust in a relationship, but the will of the partners to commit themselves to the respective relationship.

2.2.4 Outcomes

The right side of Figure 1 displays the outcomes of the relationship, which are influenced through the degree of commitment and trust in a relationship. Morgan and Hunt (1994) evaluated five outcomes: (1) acquiescence, (2) propensity to leave, (3) cooperation, (4) func-tional conflict and (5) uncertainty.

Morgan and Hunt (1994) define acquiescence as the degree to which the partners comply with certain demands or policies from the other party. They show that the higher the commitment, the higher the willingness of a partner to accept requests and wishes. A posi-tive effect can also be found for the propensity to leave, which refers to the likeliness of a partner to dissolve the relationship. Thus, the higher the perceived commitment, the lower the possibility that a partner will terminate the relationship.

Cooperation, which relates to the partners’ willingness to work together to achieve mutual goals (Anderson & Narus, 1990), is influenced by both commitment and trust. Morgan and Hunt (1994) show that higher commitment will lead to enhanced cooperation due to the partner’s motivation to attain a functioning relationship. Trust has the same effect, since trust is a precondition for cooperation, a detection which relates back to the prisoner’s di-lemma experiments conducted by Deutsch (1962).

Moreover, a higher degree of trust leads to more functional conflict. As opposed to con-flict, functional conflict does not carry a negative denotation but can rather be seen as a constructive and amicable way of solving disagreements. The underlying reason behind this claim can be traced back to the antecedents of trust such as enhanced communication which makes the parties believe that disputes will be handled in a functional manner (Mor-gan & Hunt, 1994).

Finally, Morgan and Hunt (1994) show that enhanced trust is related to decreased decision-making uncertainty as a partner’s confidence in the predictability and desirability of conse-quences deriving from certain decisions is heightened.

2.2.5 Findings of the KMV model

Correlation analysis supported all thirteen linkages constructed in Figure 1. The empirical findings show that over a half of the variance in relationship commitment and trust could be explained by Morgan and Hunt’s chosen antecedents. With regard to cooperation, Mor-gan and Hunt (1994) explain almost half of the variance by the direct effect of relational commitment and trust. A rival model constructed by Morgan and Hunt (1994) explained far less variance and only found two antecedents that significantly affect the level of coop-eration. However, the KMV model proves that the introduction of trust and relational commitment as key mediators results in all antecedents (except relational benefits) having a significant effect on cooperation. Thus, the main finding of their empirical research is the importance of conceptualising trust and relationship commitment as mediators of im-portant relational variables. Based on these findings, we believe that the KMW model is an appropriate basis from which to investigate determinants of sustainable cooperation in the Swedish market for outdoor power equipment.

2.2.6 Previous Application of the KMV Model

While the KMV model is highly recognised and referred to in relationship marketing, few replications of Morgan and Hunt’s research have been published in peer-reviewed journals. The few that have been published cover a wide range of fields. For instance, Li, Browne and Wetherbe (2006) used the KMV model to research how trust and commitment are cre-ated towards websites. Whilst Bowen and Shoemaker (1998) applied the KMV model to research commitment and trust among guests in luxury hotels. Zineldin and Jonsson (2000) used the KMV model as the basis in their research on commitment trust between dealers and suppliers in the Swedish Wood industry by focusing on the lumber dealers in the rela-tionship dyad.

Another study that made use of the KMV model was conducted by Friman, Gärling, Mil-lett, Mattsson and Johnston (2002), in which they investigated commitment and trust among service companies in a B2B market. The research by Friman et al. (2002) differs from many of the previously examined studies by making use of a qualitative method through interviews instead of the more common survey method with subsequent statistical analysis. The study also focused on relationships between firms in the early stage of the re-lationship development and international rere-lationships between firms in Sweden, Australia and the United Kingdom.

Yet another interesting application of Morgan and Hunt’s (1994) KMV model was achieved by MacMillan, Money, Money and Downing (2005), who applied the commitment – trust theory to the not-fprofit sector. Their research assessed how not-fprofit or-ganisations can gain commitment and trust from current and potential funders of their op-erations. The study was conducted in South Africa, using a local crime-prevention not-for-profit organisation as their case study. Like in many other previously described applications of the KMV model, MacMillan et al. (2005) adapted the antecedents of commitment and trust to fit with their purpose and the not-for-profit context. Their study confirmed the importance of commitment and trust in their specific research setting and proved that as-pects such as communication, shared values and particularly the presence of non-material benefits were important in order to gain trust and commitment among the funders. Conse-quently, their findings had highly applicable implications for fundraising strategies of not-for-profit organisations as non-materialistic benefits, such as funder involvement in activi-ties, transparency and demonstration of achievements, were found to be of great im-portance to the funders.

The studies mentioned above made use the KMV model in several ways and applied it to a range of different contexts. However, they all proved successful in confirming Morgan and Hunt’s (1994) main proposition of the importance and mediating effects of commitment and trust in relational exchanges. In addition to the already mentioned applications of the KMV model, there are two more studies worth giving attention to because of their find-ings. These will be presented in the remainder of this section.

ex-search left the subject unexplored. In essence, Morgan and Hunt (1994) simply assumed that the outcomes suggested by their model will result in improved financial performance but left that assumption untested and for others to explore. This constitutes the starting-point of a study conducted by Morris and Carter (2005). Morris and Carter (2005) depart from the outcomes suggested by Morgan and Hunt (1994) and explore the impacts on supplier performance in logistics. Thus, their study can be seen as an extension of Morgan and Hunt’s (1994) KMV model, as it focuses on the performance consequences that result from the outcomes proposed in the KMV model.

The study by Morris and Carter (2005) revealed that cooperation is positively related to supplier performance. Conversely, they also establish that a high degree of uncertainty is negatively related to supplier performance. Both these relations were proven to be signifi-cant. However, for the remaining outcomes in Figure 1 (acquiescence, functional conflict and propensity to leave), no significant relation to supplier performance was discovered. Nevertheless, their research made an important contribution by confirming the importance of cooperation in distribution channels as being highly related to performance.

One of the limitations of the study by Morris and Carter (2005) is that although they were successful in measuring performance, this measurement was limited solely to performance in the logistics field. Consequently, other potential areas of performance measurement were not included in their study.

The second article of interest was published by Lancastre and Lages (2006), who used the KMV model to research determinants of cooperation between B2B firms in an e-commerce context. Their study was not a strict replication of Morgan and Hunt’s (1994) research but rather based on a slight modification of the original KMV model. The sole outcome of interest for Lancastre and Lages (2006) was cooperation. The mediating effects of commitment and trust remained inherent and unchanged in their model, but the ante-cedents were adapted to fit the e-commerce context.

Consequently, their model includes three new antecedents of commitment and trust, name-ly product prices, post-acquisition benefits, as well as relationship policies and practices. The construct of product prices was adopted on the assumption that a competitive price achieved through cost-efficiencies enhances perceived value among buyers and therefore increases their level of commitment towards the supplier. The construct of post-acquisition benefits is not entirely original in Lancastre and Lages (2006) model but rather an adaption of Morgan and Hunt’s (1994) construct of relationship benefits. Lancastre and Lages (2006) adapted it to fit with e-commerce but kept the underlying assumption that firms who receive superior benefits from their partnerships will be more committed to the rela-tionship. The final new construct in their model was relationship policies and practices which again are similar to a construct already found in Morgan and Hunt’s (1994) model, namely shared values. However, Lancastre and Lages (2006) included an additional com-ponent to the construct, that of problem solving orientation.

The remaining antecedents of commitment and trust were left unchanged from that of Morgan and Hunt (1994) and comprise of termination costs, opportunistic behaviour and

communication. Lancastre and Lages (2006) made the proposition that in an e-commerce setting, the importance of commitment and trust is increased, compared to traditional tribution channels, as the exchange parties often are separated by great geographical dis-tance and also because the risk and uncertainty associated with e-commerce is more pro-nounced. Generally, e-commerce was assumed to entail a higher level of perceived risk for buyers because of security problems associated with the internet, the possibility among online suppliers to act opportunistically and finally because of the relative low experience among buyers to purchase products and services online (Lancastre & Lages, 2006).

In the study by Lancastre and Lages (2006) buyers in the Portuguese market, in this case small and medium sized companies had to assess one supplier. This focus on only one supplying partner constitutes a limitation within their study. However, Lancastre and Lages (2006) did prove that commitment and trust are key determinants of cooperation also in an e-commerce setting. Furthermore, their findings suggest that commitment has a larger im-pact on cooperation than trust. In accordance with the findings of Morgan and Hunt (1994), Lancastre and Lages (2006) illustrate that trust is positively related to commitment, in other words, trust is a prerequisite of commitment. In addition to proving the mediating effects of commitment and trust, Lancastre and Lages (2006) were also able to confirm the majority of their antecedent hypotheses. Such as, the negative relationship between high product prices and relationship commitment and that high termination costs are positively related to relationship commitment. Whilst the study succeeded in validating the key as-sumptions of Morgan and Hunt’s (1994) KMV model, the main accomplishment of Lan-castre and Lages (2006) was to prove the validity of the KMV model in a new setting, that of B2B e-commerce.

2.2.7 Critique

Morgan and Hunt’s (1994) proposed model has attained numerous supporters among scholars around the globe and has been widely applied throughout academia (e.g. Frimanet al., 2002; Lancastre & Lages, 2006; Hsiao, 2006). However, like more or less all research, it has been the object to some critics. A common concern is the use of abstract notions such as trust and commitment. As an example, Gambetta (1988) highlighted the problem that no consensus was reached for defining trust and that this is problematic when comparing different studies on trust. Later research such as that by Hernandez and Santos (2010) shows that this controversy still exists.

The second and major critique concerns the lack of theoretical framework for the anteced-ents of commitment and trust (Sheth & Parvataiyar, 2000). Morgan and Hunt (1994) pro-pose that different organisational environments might have an impact on which anteced-ents are influential and suggest applying their model in different contexts to assess the ex-ternal validity.

2.3 The Use of the KMV model in our research

We have followed Morgan and Hunt’s (1994) suggestion to apply the KMV model to a dif-ferent and specific context. With regard to cooperation, which they consider to be the cru-cial outcome, they state that “if cooperative relationships are required for relationship marketing

suc-cess, our results suggest that commitment and trust are, indeed, key” (Morgan & Hunt, 1994, p. 31).

Since this accurately reflects the underlying problem examined by this thesis, the relation between cooperation, commitment and trust will be extracted and used to serve as the core, as well as the starting point of our investigation. The mediating effects of relationship commitment and trust will be assumed to be given in the preceding argumentation and analysis. The application of this triad, while leaving out the other outcomes of Figure 1, is also sufficient with regard to this research as Morris and Carter (2005) revealed that higher cooperation leads to better supplier performance. This enhanced supplier performance re-flects the manufacturers perspective of this research and is the main reason for attempting to enhance cooperation with dealers in the first place.

In line with the criticism against the model we have chosen to be neutral with regard to the antecedents proposed by Morgan and Hunt (1994). The antecedents used in our conceptual framework will be identified through an extensive literature review, encompassing the four major interorganisational performance perspectives (see section 2.1), as well as evaluations of the suitability of the respective antecedents in the context of the Swedish outdoor power equipment market. Overlapping with antecedents of Morgan and Hunt (1994) will there-fore only occur if they are found to be inevitable to fulfill the purpose of this thesis.

2.4 Presentation of the Conceptual Framework

Figure 2. Conceptual framework in this research, based on the KMV-model by Morgan and Hunt (1994). 2.4.1 Cooperation

Cooperation, depicted as outcome in both Figure 1 and 2, is one of the outcomes that Morgan and Hunt (1994) used in their model along with four other outcomes. However, in accordance with the proposed purpose of our research, cooperation is the outcome of our interest and thus we exclude the remaining four outcomes included in the original KMV model (Figure 1). According to Morgan and Hunt (1994) cooperation was considered to be the core outcome of the KMV-model, as it is vital in promoting success within the rela-tionship.

Even earlier channel research recognises the importance of cooperation in channel behav-iour (Young & Wilkinson, 1989). Boersma, Buckley and Ghauri (2003) concluded that ex-change partners cooperate with the other party to pursue economic rewards. Cooperation is thus crucial in relationship marketing to generate benefits for the parties involved (Gummesson, 2002). The underlying logic behind it is that the parties are dependent on each other and as interdependence is present in a channel relationship, organisations realise that they are stronger if they work together and cooperate instead of working individually (Etgar & Valency 1983; Skinner, Gassenheimer & Kelley, 1992). According to Hsiao (2006), the motivation to pursue such a cooperative behaviour can be deduced to five

un-Antecendents:

Mediating Variables:

gevity of the relationship, and (5) to gain value to the company externally through for ex-ample, carrying a well-known brand and the extent of support from an supplier.

In this distinction, compliance to a powerful party and the existence of high switching cost represent the view that cooperation or coordination between channel members is achieved through the use of power that can be exerted to change the channel partner’s behaviours (Stern & El-Ansary, 1989). Morgan and Hunt (1994) state that this approach, in which power and potential conflict are of interest, is responsible for overshadowing the pursuit of understanding the nature of cooperation. With the introduction of commitment and trust as key mediating variables for cooperation, it was their intention to induce a paradigm shift away from the belief that power is crucial to condition cooperative behaviour.

This stance has prevailed in more recent research and Valenzuela and Villacorta (1999) acknowledge that active cooperation between firms is necessary in order to be able to cope with new competitive challenges. Moreover, Grönroos (1996) supports the view that if par-ties work against each other, the outcomes will not be desirable, whereas cooperation fos-ters a win-win scenario in which partners benefit from each other and realise the need for mutually beneficial actions.

Thus, we define cooperation as efforts of individual parties to work together in order to achieve mutual goals, aligned with the definition made by Andersson and Narus (1990). This is most suitable to target the underlying problem and the purpose of this thesis as such cooperation aims at achieving value creation by fostering collaboration and interac-tion, which in turn stimulates the long-term orientation of relationships (Hewett & Bearden, 2001; Sheth & Parvatiyar, 1995). Cooperation is the final outcome in our model and is argued to be primarily influenced by the mediating variables of commitment and trust (see Figure 2).

2.4.2 Relationship commitment

2.4.2.1 Reflection about Relationship Commitment

The conceptualisation of relationship commitment, as seen in figure 2, is adapted from Morgan and Hunt (1994) who state that relationship commitment exists as an exchange partner believes that an ongoing relationship with another is so important as to warrant maximum efforts at maintaining it. In other words the committed party believes the rela-tionship is valuable enough to work on it to ensure that it sustains indefinitely.

In previous research, organisational commitment is generally considered to be a construct of three main factors deriving from an attitudinal perspective (Mowday & Porter, 1979). Those are (1) a strong belief in and acceptance of the organisations goals and values, (2) a willingness to exert considerable effort on behalf of the organisation and (3) a strong desire to maintain membership in the organisation. Although this definition reflected organisa-tional commitment in an intra-organisaorganisa-tional setting from employees towards the employer, this definition is adapted into definitions used in the setting of inter-organisational relation-ships. For example, Anderson and Weitz (1992) showed that commitment between distrib-utors and manufacturers entails a desire to develop a stable relationship, a willingness to

make short-term sacrifices to maintain the relationship, and a confidence in the stability of the relationship. Also, the definition by Moorman, Deshpandé and Zaltman (1993) of rela-tionship commitment is closely related as it states that commitment to the relarela-tionship is defined as an enduring desire to maintain a valued relationship. Dwyer et al. (1987) under-lined the importance of constant dedication of resources towards a relationship. They con-ceptualised such constant dedication as commitment toward a relationship. The reflected long-term orientation of commitment, the will to dedicate efforts and resources as well as the active engagement needed by partners to reach commitment, justifies its role as a medi-ating variable which influences cooperation.

2.4.2.2 Relationship Commitment and its Influence on Cooperation – RQ 1

As pointed out by Anderson and Weitz (1992), mutual commitment will enhance the prof-itability of both partners, as manufacturers might get better access to market information or attain better dealer support and since dealers can for example reach enhanced customer satisfaction and differentiate themselves more effectively from competitors. Thus, both parties derive value from each other, which shapes their desire to maintain and deepen the relationship as these convergent interests lead to mutual gains through cooperation and joint action (Kumar, Scheer and Steenkamp, 1995).

Therefore, we propose that a party that is committed to a relationship will cooperate as it wants to ensure the effective functioning of the relationship. This leads to our first hypoth-esis in regard to answering the first research question:

Hypothesis 1: There is a positive relationship between relationship commitment and co-operation

2.4.3 Trust

2.4.3.1 Reflections about Trust

We have chosen to use Morgan & Hunt’s (1994) conceptualisation of trust which states that trust occurs when one party has confidence in a partner’s reliability and integrity. Trust has been considered central to successful relationship marketing and cooperation by many researchers (Berry 1995; Dwyer et al., 1987; Pruitt, 1981; Blau, 1964).

As such, it is important to explore the definition of trust, since this is an issue that has en-gaged scholars from many different disciplines over the years (Gambetta, 1988). At present, a generally accepted consensus on the definition of trust is yet to be achieved, and as such, the conceptual confusion that persists makes it problematic to compare one study on trust to another (McKnight & Chevany, 1996). Hernandez and Santos (2010) denote that this disagreement is still prevailing today as it has been in the past. The underlying reasons for these disagreements are diverse. McKnight and Chevany (1996) stated that researchers, in order to enhance their result in terms of internal consistency and external validity, tend to limit the scope of their conceptualisation of trust. Mayer, Davis and Schoorman (1995)

ad-dress the problem of defining trust by stating that terms, such as cooperation, have been used synonymously and they suggest that a clear distinction is needed.

Before the academic contribution made by Morgan and Hunt (1994), two perspectives of defining trust were commonly acknowledged. One perspective depicts trust as a belief that a partners' word or promise can be depended upon and that this partner fulfills his or her obligations in the relationship (Blau, 1964; Rotter, 1967).

The second perspective represented a more behavioural approach. According to Deutsch (1962), trusting behaviour comprises of actions that cannot be controlled by the trustor and increase his or her vulnerability in situations where the penalty of the vulnerability abuse is greater than the benefit of refraining from the abuse. Zand (1972) exemplifies this perspec-tive with the illustration of parents hiring a baby-sitter, in whom the parents show a high degree of trust. The vulnerability of the parents is certainly increased and they are not ca-pable of controlling the actions of the baby-sitter once leaving the house. If the baby-sitter now abuses the situation, the penalty might be a tragedy which impacts drastically on the rest of his or her life; if the babysitter refrains from the abuse, the reward might be to watch a movie.

Moorman et al. (1992, p. 82) bridged these definitions and defined trust as “a willingness to

rely on an exchange partner in whom one has confidence”. They argued that both belief and

behav-ioural intention components must exist for trust to be present and supported their claim by exemplifying how a person considering a partner to be trustworthy still can be reluctant to rely on this partner. In addition, they demonstrate that reliance on a partner can exist with-out the counterparts’ belief of this partner’s trustworthiness. The later might instead show an asymmetric power distribution or dependency, where one partner has few or no options but to rely on the other partner.

The conceptualisation of trust made by Morgan and Hunt (1994) touches many of the well-cited sources of the definition of trust and like the one of Moorman et al. (1992) it high-lights the importance of confidence and reliability. It is not limited to a certain aspect of trust, but instead reflects both the attitude and behavioural side of it. They study also, as proposed by Mayer et al. (1995), makes clear distinctions between trust and cooperation. Morgan and Hunt (1994) also inspired a common and frequent definition of today: “trust is

the willingness of one party to be vulnerable to the actions of another party based on the expectation that the other will perform a particular action important to the trustor, irrespective of the ability to monitor or control that other party” (Mayer et al., 1995, p. 712). It might be argued that the aspect of

vulnerabil-ity is not completely covered in the definition of Morgan and Hunt (1994). However, they make a crucial assumption that a relational exchange will not exist if there is no interde-pendency among the parties, which in turn implies that there is vulnerability present. Lastly, their definition is also closely related to a more classical psychological view of trust which was defined by Rotter (1967) as a generalised expectancy held by an individual that the word of another can be relied on.

Following this discussion we find the definition by Morgan and Hunt (1994) to be suitable and highly profound as it eliminates most of the controversies related to the concept of trust.

2.4.3.2 Trust and its Influence on Cooperation – RQ 1

As inferred by Mayer et al. (1995) it is important to make a clear distinction between trust and cooperation. The underlying reasons for the separation of these terms are sound. Scholars such as Kee and Knox (1970) proved that there are several situations where the cooperative behaviour is not associated with the level of trust in the relationship. They show that one party can cooperate without having trust in the other party by referring to a situation with implemented external control mechanisms that will punish a trustee for dis-honest behaviour. In such situations a trustee might behave and cooperate in such a way that it coincides with the desires of the trustor (Mayer et al., 1995). Thus, trust cannot be equated with cooperation.

However, several scholars have showed a close positive and predictive relation between trust and cooperative behaviour in an organisational context (Johnston, McCutcheon, Stewart & Kerwood, 2004; Siguaw, Simpson & Baker 1998, Morgan & Hunt, 1994). Gam-betta (1988) illustrates the underlying relation between trust and cooperation by claiming that trust is what makes cooperative endeavors happen.

In bargaining, it is evident that sellers want to be perceived as trustworthy since this fa-vours interaction and integrative behaviour from the buyer (Schurr & Ozanne, 1985). In organisational contexts, the same outcomes can be found as Pruitt (1981) notes that trust will foster constructive dialogue and cooperative problem solving. This illustrates that trusting behaviours imply a commitment to make relationships work (Morgan & Hunt, 1994). Smith and Barclay (1997) show that a higher degree of perceived trustworthiness, re-sults in more trusting behaviours being exhibited by partners. Those behaviours can best be described as actions that entail a willingness to accept vulnerability and uncertainty (Moorman et al., 1992). In other words, there is a high risk involved in undertaking those actions. Consequently, a party will only pursue high-risk, coordinated behaviours if trust is present (Pruitt, 1981).

The presence of trust facilitates cooperative behaviour as it makes organisations more in-clined to overlook or postpone short-term profits in order to gain long-term cooperative profits (Anderson & Narus, 1990). This assumption is underpinned by the organisations belief that the other party will perform actions that will bring a positive outcome for the organisation and not act in an unexpected manner that will put the organisation at risk (Hsiao, 2006). Thus, a trusting downstream partner will work more on behalf of his up-stream partner (Anderson, Lodish, & Weitz, 1987)

Furthermore, increased competitive forces in modern markets constitute another reason for firms to engage in long-term cooperative relationships that are based on trust

(Raimon-might be dependent on the relationship context, which gave rise to our curiosity to evaluate the role of trust in the Swedish outdoor power equipment market. Taking the preceding ar-gumentation into account, and in line with research question one, we postulate the follow-ing hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: There is a positive relationship between trust and cooperation

2.4.3.3 Trust and its influence on Relationship Commitment – RQ 2

As argued by Dwyer et al. (1987), buyer-seller relationships depend on the commitment made by each of the partners to the relationship. This study points out that in order to reach the long-term benefits that relationships offer, it is often necessary to make short term sacrifices which might expose vulnerabilities and put each of the parties at risk. This highlights the importance of trust in a relationship. Morgan and Hunt (1994) argued that trust, conceptualised as one party that has confidence in an exchange partners reliability and integrity, has major influence on relationship commitment. This view can be traced back to social exchange theory, which claims that mistrust feeds mistrust and in turn de-creases relational commitment, which in turn can force the relationship towards a short-term perspective with short-short-term exchanges (McDonald, 1981).

Several other theorists have also discussed these two key terms in relation to each other. Miyamoto and Rexha (2004) suggest that trust is a prerequisite for relationship commit-ment and that a suppliers’ long term marketing objective should be focused on winning customer trust. Anderson and Weitz (1989) emphasise that it is possible to stabilise and nurture long-lasting industrial relationships by cultivating trust, which increases commit-ment from the other party. Ganesan and Hess (1997) explain it more explicitly and state that trust enhances commitment to a relationship by:

(a) Reducing the perception of risk associated with opportunistic behaviours by the part-ner.

(b) Increasing the confidence that short-term inequities will be resolved over a long period. (c) Reducing the transaction costs in an exchange relationship.

Garbarino and Johnson (1999) take it further and argue that commitment is unlikely to be present itself unless there is trust in the relationship. This is due to the inherent nature of commitment requiring vulnerability towards the other party. Therefore we posit the follow-ing hypothesis, answerfollow-ing research question two:

Hypothesis 3: There is a positive relationship between trust and relationship commitment.

2.4.4 Antecedents of Commitment and Trust – RQ 3

To satisfy research question three, an extensive assessment of literature spanning the four perspectives of interorganisational relationships was carried out (see section 2.1). We iden-tify five likely antecedents of commitment and trust in the relationships between suppliers

and dealers in the Swedish outdoor power equipment market. As shown in Figure 2 we postulate that (1) support, (2) termination costs, (3) supplier commitment, (4) participation are positively related to relationship commitment of the dealer, and (5) that communication impacts on trust directly as well as on commitment indirectly through the effects of trust. The authors are aware that the chosen antecedents capture only a fraction of numerous in-fluential factors on commitment and trust, but perceive the identified antecedents to be of key importance in the underlying context.

2.4.4.1 Support

Providing support to retailers is an important way for suppliers to influence dealers in the industrial channel (Etgar, 1978). Retailer support can manifest itself in many ways, for in-stance by providing the retailer with product and service training or extensive warranty programs (Brown and Lusch 1995). Anderson and Weitz (1989) further stipulate the provi-sion of promotional material and requested information as being crucial support mecha-nisms. Kotabe, Martin and Domoto (2003) add to this research by pointing out the need for knowledge sharing through technical and capability exchanges. These exchanges are implemented via information flow, personnel support, as well as joint training programs and improve operational strength. Consequently, problem solving abilities and a common understanding of products, competition and markets is enhanced (Luo et al., 2009).

Providing the outlined support to dealers is highly beneficial as it creates a better relation-ship between manufacturers and dealers (Delano, 1984). Additionally, Park (2004) suggests that promotional support can foster a long-term relationship and benefits both exchange parties.

In the context of dealers within the outdoor power equipment industry in Sweden, servic-ing is an integral part of their business offerservic-ing and one of the key aspects that separate these specialty stores from other types of retailers (Husqvarna website, 2011). As these spe-cialised dealers are generally small businesses with small possibilities to carry expertise knowledge in the previously mentioned fields, they require support in order to target and service the customers in the most effective way. Suppliers such as Husqvarna (Husqvarna annual report, 2010) have explicitly stated that their current focus is on increasing their supportive activities toward dealers, which further triggers our interest in this particular an-tecedent. As this support will lead to better outcomes and a long-term orientation, as de-noted by Park (2004), we assume that supporting dealers can be an important way of gaing commitment. In our research, this proposition will be tested to see whether supplier in-duced support measures impact on the commitment of the dealer. Hence, we hypothesize: Hypothesis 4: There is a positive relationship between support and relationship commit-ment.

2.4.4.2 Termination costs