Open Innovation in Digital Transformation Era

A Qualitative Study

of the Impact on Customers’ Role in ABB Drive

LU, PEISHAN

MOLYTE, JOVITA

School of Business, Society & Engineering

Bachelor Thesis in Business Administration

Supervisor: Silvia Bruzzone

FOA 230

8

thof June, 2020

1

Abstract

Date June 8th 2020

Level Bachelor Thesis in Business Administration, 15 credits

Institution School of Business, Society and Engineering, Mälardalen University

Authors PeiShan Lu & Jovita Molyte

Tutor Silvia Bruzzone

Title Open Innovation in Digital Transformation Era – A Qualitative Study of Impact on Customers’ Role in ABB Drive

Keywords Digital Transformation, Product Development, Customers’ Role, B2B, Open-Innovation, Industry 4.0

Research Question

What is the customers’ role in the product development process in the digital transformation era?

Purpose To gain an understanding and contribute with knowledge to the gap of how digital transformation of a supplier company affects customers’ role in the product development process

Method This paper is a qualitative case study in ABB based on primary data collected through semi-structured interviews. After data collection, thematic analysis has been conducted to analyse the findings.

Conclusion Customers’ role can vary depending on the supplier-customer relationship, positions in the market, general environment circumstances and supplier’s needs. Each type of customer provides different knowledge due to their varied needs and serves as information sources for continuous product and service innovation, either in the form of feedback sharing or codevelopment. In the digital age, there is a higher chance for customers to give direct feedback through integrated digital platforms; customers are also valuable data providers that allow companies to understand the device performance in its lifecycle, in return, customers are the receivers of better functionalities of the device. Customers are information receivers, most of the time, they are not fully aware of the possibilities that new technological development brings until the supplier provides high end solutions. Also, the early technology adopters are not the majority, the few customers’ joint problem solving is deemed ever more important as they are the ones experiencing the practicality of the sensor/product/service.

2

Acknowledgement

The authors of this work would like to express our deepest appreciation to those who help us improve our research paper throughout the process. Many thanks to the seminar groups, our supervisor, co-assessor and our peers, for giving us feedback, without the valuable suggestions and guidance, we would not be able to present the paper today.

The authors would like to especially extend our gratitudes to ABB Drive and Softstarter, for providing insightful information and knowledge for this paper. Special thanks to the two managers who assisted us throughout the process; without their support and counsel, we would not have completed the idea formation and data collection. In return, we hope this work can be of contribution to their division.

We would also like to extend appreciation to Mälardalen University and the program responsibles for providing a digital platform during the COVID-19 time and making it possible for completing our bachelor thesis from a distance. We also appreciate the librarians who worked to put together the online resources for access to journal articles and books, they have been of tremendous help for this paper.

Many thanks to those who supported us through the process of this work, whether by giving precious advice or standing by us, without them, this work cannot be done in this difficult time during the world pandemic.

Sincerely,

PeiShan Lu & Jovita Molyte 26th May 2020

3

Contents

1. INTRODUCTION ... 5

1.1PROBLEM BACKGROUND ... 5

1.2AIM AND RESEARCH QUESTION ... 7

1.3DELIMITATION ... 7

1.4THESIS OUTLINE ... 8

2. LITERATURE REVIEW ... 9

2.1VALUE CREATION ... 9

2.2EXTERNAL STAKEHOLDER INVOLVEMENT:OPEN INNOVATION ... 9

2.2.1 Open Innovation in the Digital Era ... 11

2.2.2 Customer Involvement ... 11

2.3PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT IN DIGITAL TRANSFORMATION ERA ... 12

2.3.1 Customers’ Role ... 13

3. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY ... 16

3.1RESEARCH DESIGN ... 16

3.2LITERATURE REVIEW ... 16

3.3PRIMARY DATA AND SECONDARY DATA ... 17

3.4QUALITATIVE APPROACH ... 17

3.4.1 Semi-structured Interviews ... 17

3.4.2 Case Study Company – ABB Drive ... 18

3.4.2.1 Case Study - Drive Digital Transformation Journey ... 20

3.4.3 Purposive Sampling ... 20

3.5EMPIRICAL INTERVIEWING PROCESS ... 22

3.6ANALYSIS METHODOLOGY ... 22

3.7QUALITY OF RESEARCH ... 24

4. EMPIRICAL FINDINGS ... 26

4.1VALUE CREATION ... 26

4.2EXTERNAL STAKEHOLDER INVOLVEMENT IN VALUE CREATION:OPEN INNOVATION ... 27

4.2.1 Open Innovation in Digital Era ... 30

4.2.2 Customer Involvement ... 33

4.3PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT AND DIGITAL TRANSFORMATION ERA ... 34

4.3.1 Customers’ Role ... 34

5. ANALYSIS AND DISCUSSION ... 37

5.1.CUSTOMERS’ROLE IN THE PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT PROCESS ... 37

5.2.DIGITAL TRANSFORMATION ERA ... 39

6. CONCLUSION ... 42

7. REFERENCES ... 44

4

Glossary

Digital Transformation (DT)

Technology-driven process that triggers changes in a company's operational structures in order to find new ways to create value.

New Product development (NPD)

Set of procedures that are conducted from when the idea of new product or service occurs until it reaches the market.

Open Innovation Approach to innovation that encourages usage of external sources

for firm’s own innovation activities.

Early Adopter Business that adopts novelties earlier than the majority of the

market.

ABB ASEA Brown Boveri. Swiss-Swedish multinational corporation

currently operating in 4 businesses: Industrial Automation, Electrification, Motion, and Robotics & Discrete Automation.

B2B Business to Business.

OEM Original Equipment Manufacturer.

HVACR Heating, Ventilation, Air Conditioning and Refrigeration.

AC/DC Drive Alternating Current/Direct Current Drive is a frequency converter

5

1. Introduction

This chapter describes the background of phenomenon in focus as well as the problem discussion and the aim of the study.

1.1 Problem Background

Recent developments in digital technology have been gaining importance in the business field, changing the ways that companies operate (Bajgar et al., 2019) and contributing to the emergence of digital transformation (DT) concept (Peter et al., 2020). Differently from digitization, which is the move from analog to digital data, and digitalization, which is using the digital data in order to simplify ways of working, digital transformation is concerned with reinventing how business can be done by taking a step back and reevaluating the processes, in order to find new ways to create customer value (Salesforce, n.d.). As defined by Vial (2019), digital transformation is “a process that aims to improve an entity by

triggering significant changes to its properties through combinations of information, computing, communication, and connectivity technologies” (p.118). Ebert and Duarte (2018)

also emphasize that DT is a technology-driven change process which, once widely implemented, will have a profound effect on the industry through better value chain integration, new market exploitation and competitive advantage gains. Marked by the usage of intelligent technologies, such as the Internet of Things, Artificial Intelligence, Cyber-physical and Cloud systems, as well as Big Data, DT is the driving force behind Industry 4.0, which is the subset of the Fourth Industrial Revolution in industry sector (Rao & Prasad, 2018).

Continuous technology improvements and digital transformation are creating new opportunities for ways of working and interacting. For companies this means better efficiency and effectiveness, and possibility to enter new markets, whereas for individuals – more flexible work models and lifestyles, as well as opportunities for crowdsourcing and crowdworking (Reddy & Reinartz, 2017). This brings the authors to the situation which the world was undergoing at the time this paper was written - the global COVID-19 pandemic. The fear of virus spreading forced businesses to stop their operations all over the world, putting the world’s economy at risk (OECD, 2020). However, thanks to digital technologies whose “intangible and machine-encoded nature, software, data and computing resources can be stored or exploited anywhere” (OECD, 2019, p.3) allowing people to work remotely, not all operations had to shut down.

Businesses that are undertaking digital transformation are looking for ways to integrate digital and physical elements of their operations to successfully transform business models (Berman, 2012). In the industry sector, companies are going towards adopting holistic business models (Ebert & Duarte, 2018), redesigning products/services and automating

6

production, which in turn, “allows the manufacturing companies to operate in a complex supply chain, maintain closer relationships with customers and more importantly, adjust the production in real time to the demands of the market” (Bajgar et al., 2019, p.5). Early adopters, such as the case company ABB, are facing challenges as the integration of new technologies often adds complexity to established organizational processes. In Digital

Transformation of ABB Through Platforms: The Emergence of Hybrid Architecture in Process Automation, Sandberg et al. (2019) mention that facing digital transformation challenges,

there are recurrent disruptions to the business models caused by the infusion of digital technology into the physical production environment, and that the company is in need of drastic adjustments. Therefore, to adapt internally with DT changing the form of interaction and knowledge flows, the company needs to take a deeper look and rethink their current business operation processes.

As mentioned by Berman (2012), a company’s successful DT strategy focuses on “reshaping customer value propositions and transforming their operations using digital technologies for greater customer interaction and collaboration” (p.16). Among all stakeholders in a company’s general environment, customers are the ones that directly bring revenues into the firm, and close communication between them and suppliers, as well as including customers during a firm’s innovation process is a key factor for successful new product development (Fang et al., 2008). Creating customer value through innovation and using innovative technologies for product development has been a strategy used by companies for decades (Cooper, 2011) and it has been noted that most successful innovative enterprises combine internal competencies with customers’ knowledge when developing new products (Füller & Matzler, 2007). However, including external stakeholders in a company's operations can create difficulties, such as lack of resources, reluctance from the actors to take risks, rivalry set-up of different actors and the slow pace of progress (Ojasalo & Kauppinen, 2016). In the DT era, there are also the technological disruptions and the cyber risks that come with it. They impose new challenges for manufacturers managing open innovation with their external actors, such as customers, suppliers, distributors, government sectors and more (Ollila & Elmquist, 2011).

As digital transformation causes disruptions in business models, it poses challenges to established processes but also provides new opportunities – including in how enterprises interact and include customers in internal operations (Kaidalova et al., 2018). Yan et al. (2020) note also that the developments of new technologies changed relationships between traditional customer networks and affected traditional dissemination of information. Digital transformation is a relatively new topic and there is a lack of research done on how it can impact the roles of different actors in a manufacturer’s network and operations. While scholars and practitioners have discussed factors that can be leveraged to improve innovation process performance, there is little to no research that looks deeper

7

into how open innovation processes can be managed in the digital transformation era (Urbinati et al., 2018). Customer-centric nature of digital transformation and their importance for firm’s innovation processes bring the authors to wonder how the customers’ role is affected in this era, in terms of supplier’s new product development. Empirical studies of early adopter companies could provide the knowledge to fill this gap and give valuable insights for firms planning to undergo their own digital transformations.

1.2 Aim and Research Question

With this study, the authors would like to gain a deeper understanding and contribute with new insights to the previous research by looking into how supplier’s digital transformation can impact external stakeholder involvement in their innovation processes. The authors hope to increase the knowledge by looking into the role of customers in a case study of ABB Drive.

Research Question:

What is the customers’ role in the product development process in the digital transformation era?

1.3 Delimitation

It is important to note that this study focuses specifically on the customers’ role in supplier’s product development and how digital transformation of the supplier firm can impact that role. The authors acknowledge that network dynamics and interdependencies often play an important role in B2B relationships, but choose to narrow the scope of focus onto focal supplier-customer relationships and interactions between the two actors due to the limited timeframe of the thesis.

The limited time for conducting the study also forced the authors to limit the scope to the supplier's point of view. The authors are aware and acknowledge that customer’s point of view could add valuable insights to the topic, however, the study scope was narrowed in order to be able to meet the deadlines.

Each company’s digital transformation journey is unique and, therefore, in order to gain deeper understanding the authors chose to investigate one company. As digital transformation is a topic related to computer science and engineering studies, the authors will attempt not to go into details that would be considered as too technical for a business administration research.

8 1.4 Thesis Outline

The rest of the paper is sectioned as follows: Literature review where the framework of the study is established through relevant existing theories. Methodology where authors describe how the study was conducted. After that follows Empirical Findings from the interviews conducted and Analysis & Discussion where primary data findings are analysed by comparing them with the existent knowledge from previous studies. Lastly, Conclusion answering the research question is drawn, and limitations as well as future research possibilities are discussed.

9

2. Literature Review

This chapter introduces theoretical concepts about value creation and innovative capabilities, customer involvement and how they are affected in the digital transformation

era. Purpose of the chapter is to build a framework for the study.

2.1 Value Creation

Value creation is the central concept in the marketing field which lays the basis for all marketing activities and is necessary for achieving customer satisfaction and long-lasting relationships (Smith & Colgate, 2007; Marcos-Cuevas et al., 2016). The marketer’s job, therefore, is to determine what customers perceive as value (Kotler, 2017). According to Smith and Colgate (2007), a firm’s main purpose is to create value for others, in cases when it is not efficient for the buyers to try to satisfy their needs themselves. Moreover, Kotler (2017) points out that customers receive value from a solution that product provides rather than from a product itself.

As ‘value’ is an abstract term, researchers suggest that customers and suppliers may not always perceive value in the same manner (Möller, 2006). In dyadic relationships that are common in B2B markets, value is created for the customer as well as for the supplier, therefore, both parties seek to obtain it through different perceived value sources (Smals & Smits, 2012). Value can be considered not only in the form of monetary benefits, but also in less tangible forms that cannot be measured quantitatively. Non-monetary forms of value can include reputation and trustworthiness, perceived product quality and innovative capabilities, as well as resources of business partners (Smals & Smits, 2012). The nature of long-lasting business relationships also allows for the value to come in the form of negotiating power for future interactions. Business relationships can be very complex as there are many factors affecting them, and, according to Möller (2006), in order to successfully manage B2B relationships, it is necessary to understand how value is seen by both - suppliers and customers - as well as to understand what their roles are in value creation activities.

2.2 External Stakeholder Involvement: Open Innovation

External stakeholder involvement in a firm’s value creation activities and innovative processes has been considered by researchers looking for ways to commercialize external sources (Harrison & St. John, 1996; West & Bogers, 2013), leading to open innovation becoming a popular concept. Open innovation is a term that emerged with the idea that, when looking for new developments, firms should be able to utilize ideas that originate not only inside, but also outside the company (Bogers et al., 2019). Ever since Chesbrough introduced the robust concept in 2003 in Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating

10

as a substitute model of innovation, especially since the majority of European and American corporations had already been adopting this approach (Naqshbandi et al., 2019). Open innovation is about involving external stakeholders, as well as purposively managing knowledge flows across the boundaries of organization and, due to globalization, rapid technological developments and industry integration, it has become increasingly important for companies seeking to develop new products (Xie & Wang, 2020). Collaboration and access to external resources is a crucial part in a firm’s value proposition and creation strategy for gaining or keeping competitive advantage. Adner (2017) defines a business ecosystem as a network of multilateral partners who need to cooperate with each other in order to fulfill focal value propositions. Furthermore, it has been highlighted that interactions between central institutions, such as suppliers, customers and universities, have an important role in improving firm’s innovative competences (Reynolds & Uygun, 2018; Xie & Wang, 2020).

Researchers point out two kinds of open innovation knowledge flow: outside-in, also known as inbound, and inside-out or outbound (Chesbrough & Crowther, 2006). The outside-in approach is concerned with opening a firm's innovation processes to external stakeholders and taking their inputs into consideration (Bogers et al., 2018). The inbound knowledge flow requires an organizational culture which is open to external ideas and promotes collaboration in order to avoid the ‘Not-Invented-Here’ syndrome, in which the ideas that originate outside the company face resistance and even rejection from internal stakeholders (Katsikis et al., 2016; Bogers et al., 2019). Outside-in approach allows companies to utilize discoveries of others rather than relying only on their own R&D capabilities.

The inside-out or outbound approach is based on the logic that ideas originating inside a business should be able to cross boundaries of the company. Lack of such ability may cause inconsistencies between a company's long-established habits, their product base and the actual needs of the market (Katsikis et al., 2016). Based on this approach, unused or underutilized ideas should be able to leave organizational boundaries for other actors in the external network to make use of in their businesses (Bogers et al., 2018). Inside-out part of open innovation can be used to leverage competencies outside the firm’s network by selecting certain knowledge to outflow in order to achieve a specific purpose (Naqshbandi et al., 2019). For instance, a company could publish some selective product development know-how for others to build upon and come up with new solutions, or even to encourage competition. (Bogers et al., 2018).

11 2.2.1 Open Innovation in the Digital Era

Together with digitization, the ease and nature of information travels have changed. Extensive use of the internet contributed to changes in techno-business environment, as well as to open innovation becoming a necessity due to the digital convergence of industries (Bogers et al., 2019). Companies have always, at least to some extent, used external sources for ideas and solutions, however, it is happening at a much larger scale nowadays since globalization and technology provide the ability to connect with communities all over the world. As digital platforms are omnipresent, where different types of information, for instance, images, sounds and words, can be transformed into digital data, the means of sharing knowledge are increasing which allows for multi-invention and co-innovation (Bogers et al., 2019). However, these developments contributed to the ‘paradox of openness’ and the need for strengthening of intellectual property rights as well as cybersecurity systems (Hannigan et al., 2018; Bogers et al., 2019).

Paradox of openness is concerned with the fact that in order to access knowledge from external sources, firms have to expose some of their own knowledge to external actors (Laursen & Salter, 2014). Businesses are more likely to seek collaborations with external partners if they are able to protect themselves with, for instance, patents. On the other hand, a firm's protectionist view may render them a less attractive partner for developing collaborative innovations (Arora, Athreye & Huang, 2016). The paradox shows that open innovation can be “a (strategic) balancing act among a complex set of factors” (Bogers et al., 2019, p.88) where digitization of knowledge adds the need for intellectual property rights and cybersecurity as means to protect oneself (Bogers et al., 2019; Taylor & Steele, 2018).

2.2.2 Customer Involvement

While the definition names ‘external stakeholders’, in B2B world open innovation is mainly associated with customers and their participation since they can provide valuable market knowledge (Efstathiades & Papageorgiou, 2019). Efstathiades and Papageorgiou (2019) note that an effective open innovation approach could lead to a better understanding of customer wants and needs, however, it should be integrated into business processes and managed properly in order to be truly benefited from. Digital technologies, such as social media, act as tools for customer involvement - their very nature enables interactions between multiple actors, providing the opportunity for customers to reach out to sellers (Sashi, 2012). In the digital world, new business models and new markets are created, and innovation is not only one-way - by producers selling to users - anymore, but also two-way - by the customer feeding back the information to the producer with what is needed. Open innovation concept brings the ability to create an ecosystem, where competences of

12

suppliers and customers can be combined for value co-creation, and digital transformation brings tools for enablement of that ecosystem (Bogers et al., 2018).

Compared to B2C where customer feedback is usually an integrated part of business models, in the B2B sector, open innovation is much less developed (Katsikis et al., 2016; Chesbrough & Crowther, 2006). Nevertheless, open innovation can be profitable even to the traditional, mature industries (Chesbrough & Crowther, 2006). Companies that have foreign market operations, have better chances of succeeding with open innovation as they are more open to external ideas and resources. Furthermore, researchers note that “a company philosophy open to collaboration with external partners can also have a positive impact on business process innovations, leading to a higher probability for the successful introduction of radical innovations” (Katsikis et al., 2016, p.94), meaning that collaborative organizational culture plays a big role in accepting external ideas and transitioning to open innovation practices. Although even for organizations that promote open and collaborative culture, open innovation can be difficult to implement (Katsikis et al., 2016).

While customer involvement is increasingly recognized as a success factor for new products and services (Trischler et al., 2017), researchers do not deny the drawbacks and challenges associated with including customers in NPD. Open innovation and customer involvement makes the product development process more complex which could result in inefficiencies and product delays (Efstathiades & Papageorgiou, 2019). Researchers point out also that customer involvement has been associated with incremental innovation but is rather limited when it comes to radical innovation ideas (Lundkvist & Yakhlef, 2004), and that customers are “notoriously lacking in foresight” (Callahan & Lasry, 2004, p.108). Moreover, capturing customer knowledge requires appropriate infrastructure as it is difficult to extract potentially sticky knowledge. Richer social interactions are needed to obtain insights from a customer’s environment, which are more costly than formal inquiry tools (Lundkvist & Yakhlef, 2004). This is noted by Morgan et al. (2019) as well, mentioning that costs of needed deeper involvement can prevent firms from integrating more customers resulting in loss of understanding the greater diverse market. Furthermore, Callahan and Lasry (2004) highlight the risk of being too close to or led by the customer which could be detrimental to business and its innovative capabilities.

2.3 Product Development in Digital Transformation Era

It has long been established that continuous product development is essential for companies to stay competitive in today’s dynamic market. Multiple factors, including technological advancements, market changes, competition, shortening product lifetimes, are forcing companies to develop new products ever more frequently (Unger & Eppinger, 2011), and in order to be successful long term, businesses have to constantly search for ways to improve their products (Cooper & Kleinschmidt, 1991). Researchers name new

13

product development as “a lifeblood of a firm, ensuring that obsolete products are timely replaced with new ones, thus maintaining and improving existing levels of profitability” (Biemans, 2003, p.514) which further emphasizes the importance of innovative capabilities of businesses.

In the digitalization and knowledge sharing era, the ability to develop new products and release them into the market quicker is critical. The fast-changing customer demands, market dynamics and rapid pace of technology innovation, require businesses to be flexible and come up with new solutions in a frequent manner (Schweitzer et al., 2019). Customers demand for new products that are more individualized, of higher quality and are available in the market quicker, whereas businesses attempt to satisfy these demands while the complexity of products and processes is increasing due to digital transformation (Schweitzer et al., 2019). Researchers point out that these new trends, which require combining different technologies with existing products, have huge impacts on businesses not only in terms of their competitive landscape, but also in the internal operations (Belingheri & Neirotti, 2019). When the integration of two fundamentally different types of technologies - physical and digital - is managed by employees from multiple backgrounds and with different kinds of knowledge, it can create tensions in various operational processes in the product development. This must be dealt with properly in order to deliver the promised benefits to the customer (Belingheri & Neirotti, 2019).

In order to accommodate the changing customer demands, companies need to restructure the whole value chain, including R&D and production, logistics, marketing, sales and after sales to fit into the new digital technology landscape (Belingheri & Neirotti, 2019). Researchers of digital transformation so far have been focusing on the digitalization of the offering/product, while the digital transformation of innovation process has been less widely investigated (Schweitzer et al., 2019). According to Schweitzer et al. (2019), a variety of tools and procedures are applied in establishing HR management systems, speeding up and restructuring product development processes, in order to decrease costs of NPD as well as to create a first-mover advantage. Moreover, knowledge sharing is playing an ever higher role in product development processes as “innovation managers strive to intensify knowledge exploitation and exploration by means of collaboration within and between companies” (Schweitzer et al., 2019, p.2).

2.3.1 Customers’ Role

Practice of using NPD and innovation for obtaining competitive advantage and superior financial benefits has become widespread, however, many of the new products often fail to meet expectations. Fang et al. (2008) mention that a commonly identified reason for this is that a customer is the one who holds information about the ‘need’, whereas the

14

seller’s goal is to provide a solution to that need. Closer interaction between seller and customer is the key for avoiding failures in product development. Understanding customer needs, wants and circumstances, which requires active interaction with customers, is vital for successful product development (Lagrosen, 2005). Bonner (2010) also recognizes customer’s knowledge competence as an essential element for new product success. The role of customers in orientating product development has been to some extent discussed in innovation and marketing literature, and particularly the latter focused on emphasizing the importance of understanding customer needs. Marketing researchers have discussed the possibility and ways of including the customer in marketing programs in order to obtain customer’s knowledge for further product development (La Rocca et al., 2016).

With customer-oriented business models being more widely adopted, it is no wonder that customers are expected to have a role in product development. Researchers state that empowering customers and allowing them to develop products and even experiences together with the company is likely to be a part of successful business strategy (Chien & Chen, 2009). From a business point of view, customer involvement provides knowledge to reduce uncertainties during the innovation process as well as to achieve optimal production time and costs. For a customer, co-production provides an opportunity to gain understanding of the company and its products, which changes how the customer experiences the product (Chien & Chen, 2009). With technological advancements and the Internet, involving customers in product development activities has become easier and more cost-effective (Roberts & Dinger, 2016).

There are various theories investigating customer involvement in NPD. Bonner (2010) uses the concept of customer interactivity to discuss customer involvement in the product development process. Interactivity investigates the degree of interactions between customers and product development teams in three dimensions: 1) bidirectionality, 2) participation, and 3) joint problem solving. 1) Bidirectionality defines the flow of knowledge as either one-way or two-way, where “two-way interaction represents an interactive exchange where plans and issues are communicated and analysed, and feedback is provided” (Bonner, 2010, p.486). 2) The second dimension - participation - can be defined as the degree of active and direct customer involvement in NPD activities. This could be in the form of physical meetings, group discussions or face-to-face interactions. 3) The third dimension concerns the content of interactions and the degree to which joint problem solving takes place. During interactions, customers may provide insights for issues and solutions that the product development team had not considered, as the customers are more aware of how the new product would fit into their own organization (Bonner, 2010). On the other hand, Fang (2008) distinguishes two dimensions of customer’s role in NPD: CPI - participation as an information resource, and CPC - participation as a co-developer.

15

CPI concerns mostly activities of knowledge sharing with the supplier, whereas CPC is about joint-problem solving approach by incorporating customer’s expertise throughout the whole product development process (Fang, 2008). Morgan et al. (2019) further investigates customers’ involvement in terms of breadth and depth, where the breadth is defined as capturing the scope of customer participation across multiple NPD activities, whereas depth is defined as the degree of involvement in a stage of development process. Broad customer involvement could ensure that customer knowledge flows into all parts of product development which could increase information diversity and scope. Deep involvement, on the other hand, could provide profound customer insights (Morgan et al., 2019).

In B2B markets, it has been a common practice to involve customers in product development processes, as customer-supplier relationships tend to be closer than in B2C due to smaller number of customers. La Rocca et al. (2016) emphasize that in order to succeed, new product and solution development need extensive interactions between supplier and customer. Moreover, as more businesses shift from product-oriented logic to providing intangible services, the previously mentioned interactions are necessary since “the complex offering solutions cannot first be conceived and developed and then implemented; they must be ‘enacted jointly’ between the user/customer and producer/supplier organizations” (La Rocca et al., 2016, p.46). Customers are also recognizing the need to not only participate in the supplier's NPD process, but also to be proactively involved in order to reduce their own costs and increase product performance. Instead of being a passive buyer, the customer can take on an active role in creating value and compete for a higher share of it. The increased value that the customer obtains, impacts customer’s willingness and motivation to participate in the product development process (Fang et al., 2008).

16

3. Research Methodology

This chapter describes the paper’s research process and motivation behind each chosen approach to examine the research subject.

3.1 Research Design

The authors’ mutual interests in the recent development of technologies and how they are used in a real-life context drove the authors to the idea of this research topic. After a few unstructured interviews with two case company managers and literature review, the authors decided to carry out a study with the research question: What is the customers’

role in the product development process in the digital transformation era?

Pascale (2011) described analytic induction as the observation of numerous events in a particular phenomenon, gathering data, and through coding to establish patterns and exceptions in order to draw theoretical conclusions. The inductive approach was deemed the best fit for qualitative research (Miller & Brewer, 2003). The authors started by observing events that happened in the case company related to digital transformation, then gathered data with semi-structured interviews for deeper understanding of the topic; through coding the transcription, the authors were able to find patterns and exceptions for themes mentioned in literature review; lastly, the authors drew theoretical conclusions about the impact on customers’ role in the DT era (Pascale, 2011). The research literature used served as background understanding to the topic.

3.2 Literature Review

Throughout the work on this research paper, literature review helped the authors to be inspired and narrow down the research topic by using keyword searches to review the existing articles. It not only helped delimit the paper to a reasonable scope, but also deepened and strengthened the theoretical framework (Karlsson, 2009; Bell et al., 2019). The academic search engines used were ABI/INFORM, Google Scholar, Diva, SAGE Research Methods and Emerald Insight. They provided a wide range of business, management, economic and innovation articles from all over the world. The keywords used for this paper were: digital transformation, customer role, product development, open innovations, and

B2B. When typing the key word “digital transformation,” there were relatively few articles

due to its newness, however, the rest of the keyword research was discussed abundantly. The literature review served as the basis for the research question and helped define the research design.

17 3.3 Primary Data and Secondary Data

Primary data are described as the purest form for research sources as it is first-hand from the study subject (Salkind, 2010). The primary data used for this paper are the interviews, transcriptions, and interview notes. Bell et al. (2019) describe primary data analysis as the researchers collecting and conducting the analysis with the raw data gathered first-hand. Having the first-hand data helped the authors understand the personal experience of each interviewee and their perspectives, and also the latest information on the topics of technology implementation, customer interaction and organizational operations in the case company. Through primary data, the authors were able to see changes in the customers’ role with the impact of new technologies.

3.4 Qualitative Approach

The data for this paper was collected through qualitative interviews with participants who have different viewpoints (Bell et al., 2019), years of experience, levels of customer interactions, and involvement in the product development process. Marks and Yardley (2004) explain that qualitative research is used to attain an appreciation of how people’s subjective experiences are shaped through different circumstances, the ways people make sense of things and linguistic factors in the process of meaning creation. The interviewees here described events that had happened to them and provided several examples to elaborate the situations, for instance, visiting customers, facing cyber security issues, sensors being developed and implemented to gather data and other events. These vivid descriptions provided the authors with a very real context to comprehend the process. From different job position viewpoints the respondents illustrated how the case company tackles digital disruption, and it gave the authors a holistic view of how DT impacts different actors. In contrast to the qualitative approach, Saunders et al. (2016) pointed out when using the quantitative approach in business and management research, the respondent is asked to use a questionnaire, and then answers a follow-up ‘open’ question to further elaborate the reason behind the choice, or is requested to give an additional interview. The authors chose not to use the quantitative approach.

3.4.1 Semi-structured Interviews

In this paper, 9 semi-structured interviews with 10 respondents were carried out, each lasting between 50-120 minutes. The interview questions were designed according to the research topic with each of them having a clear aim, and they served as an interview guide (Bell et al. 2019; Given, 2008). Saunders et al (2016) describe the process as not only getting the answers on the ‘what’ and the ‘how’ but also emphasizing the ‘why.’ Semi-structured interviewing gave the authors more flexibility to use probing questions during interviews to interpret and clarify the meanings of terms, respondent standpoints, and language.

18

Semi-structured interviewing also allowed the authors to adjust the questions because of respondents’ distinct professions; the nature of their jobs are different, some are closer to the front end interacting directly with customers, some are at the back end receiving indirect customer feedback. At the end of each interview, the authors also asked the respondents if they would like to add any question or if there was anything they felt the researchers should ask to get a better angle on the topic. After some interviews, the authors were able to discuss patterns that were already existing and came up with follow-up questions. Using semi-structured interviews helped the authors gather all the data needed.

3.4.2 Case Study Company – ABB Drive

In order to gain an in-depth understanding of the research topic and the phenomenon of DT within its real-life setting, the authors chose to carry out a case study in a company (Yin, 2014; Saunders et al, 2016).

ABB (ASEA Brown Boveri), a Swiss-Swedish multinational corporation, with the headquarter located in Zurich, Switzerland. ABB was founded in 1988 as a result of the merger of ASEA (founded in 1883, Stockholm) and Brown, Boveri & Cie (formed in 1891, Baden). The two companies were manufacturers of electrical lighting, motors, generators, steam turbines, transformers, and more. Currently, there are approximately 147,000 employees all over the world. With ABB’s history of innovation spanning more than 130 years, ABB has five main businesses today: Industrial Automation, Electrification, Motion, Power Grids, and Robotics and Discrete Automation (ABB History, 2020; About ABB, 2020).

ABB Motion provides drives, motors, generators, mechanical power transmission products, and the service of digital powertrain solutions. ABB Drive is a division of ABB Motion. The industries range from water and wastewater, HVACR, food and beverage, wind, mining, oil and gas, metals, chemical to marine and more. Their goal is to keep the world running, while saving energy with a low-carbon footprint. ABB Motion and Drive products and services can be seen in different industries, cities, infrastructure, and transportation to help their customers optimize energy efficiency, improve safety and reliability, and achieve precise control (ABB Motion, 2020).

A drive, also called variable frequency drive (VFD), controls motor speed and torque by varying motor input frequency and voltage. ABB Drives include Softstarters (controls the speed of the motor when it starts and stops), low voltage AC drives, medium voltage AC drives, and DC drives. Electric motors are used to move and run almost everything on a daily basis, for business or pleasure. They rely on electricity to provide torque and speed;

19

and need the corresponding amount of electric energy to match exactly what is required by the production process (ABB Drives, 2020).

Figure 1: ABB Organization Map (ABB Drives, 2020) Electrification Industrial

Automation

Motion Robotics & Discrete Automation

Motor & Generator Drive Mechanical Power Transmission

Softstarter Low Voltage AC Drive

Medium Voltage AC Drive

20

3.4.2.1 Case Study - Drive Digital Transformation Journey

ABB is an early adopter of new technologies and has been undergoing digital transformation for a period of time now, successfully transforming their business operations. ABB is a large company, and parts of it started their DT journey earlier while others are still new to this transformation. However, ABB Drive organization began their digital transformation quite some time ago, managing not only to integrate their products with new data-driven features using sensors plugged in to the device, but also to provide integrated services and digital solutions, such as remote condition monitoring for preventive

maintenance, energy optimization, preventive unplanned downtime and life cycle assessment (ABB Drive, 2020). All these show that Drive organization has come far in the

journey and gathered knowledge that could be valuable in understanding what makes a successful digital transformation of a company. Moreover, due to their nature, the above mentioned services and solutions cannot function to their full extent or be implemented without customer involvement. Drive organization has close relationships with different types of customers (end users, OEM, consultants, distributors, and more) in terms of product/service experience feedback and lead user codevelopment. These factors make ABB Drive an excellent organization to investigate what role customers play in a company’s product development in the digital transformation era.

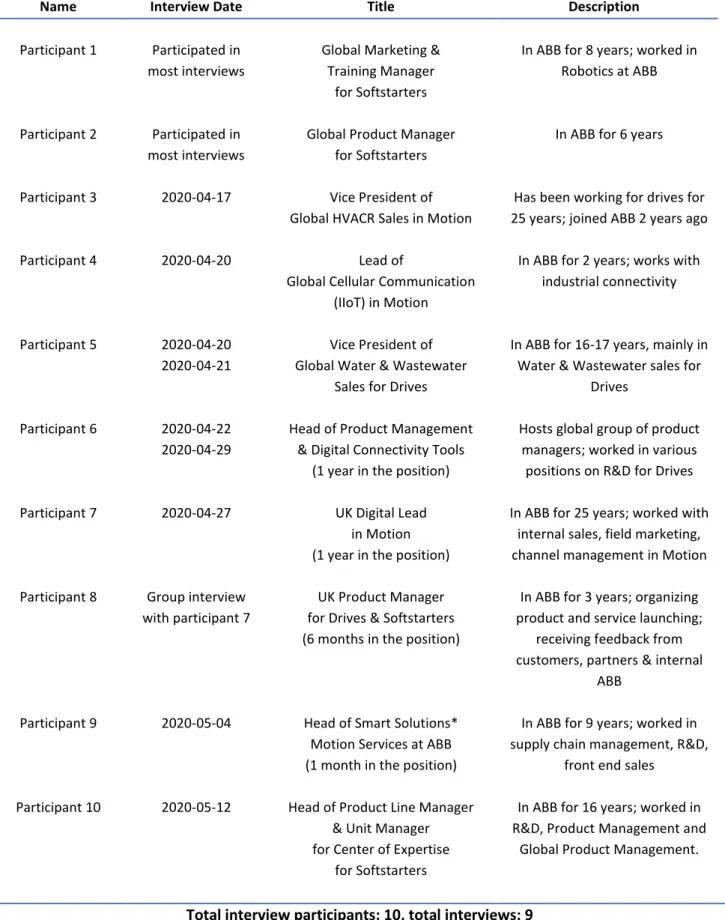

3.4.3 Purposive Sampling

The authors chose to select interview participants using non-probability (purposive) sampling in ABB Drive organization on the basis of their close relation to this paper’s research subject (Bell et al., 2019; Jupp, 2006). The requirements when choosing interviewees were that they have experience with digital transformation, customer

interactions, and internal innovation processes. There are in total 10 participants, see table

1. The list of respondents is the result of discussions between the authors and participants

1 and 2, who are managers in Drive (Softstarter) organization and have knowledge of the

respondents’ professional backgrounds. This helped ensure the source of data is relevant to the research subject. Participants 1 and 2 participated together with the authors in several interviews. They mostly stayed in the background to observe and learn Drive’s DT journey and provided relevant knowledge. Drive organization is located all over the world, and their main office is in Finland. Due to different professional backgrounds, they are located also in Denmark and the UK.

21

Table 1: Interview Participants

*Smart solution unit consists of product development, technology development, technology research, sales support, and operations.

Name Interview Date Title Description

Participant 1 Participated in

most interviews

Global Marketing & Training Manager

for Softstarters

In ABB for 8 years; worked in Robotics at ABB

Participant 2 Participated in

most interviews

Global Product Manager for Softstarters

In ABB for 6 years

Participant 3 2020-04-17 Vice President of

Global HVACR Sales in Motion

Has been working for drives for 25 years; joined ABB 2 years ago

Participant 4 2020-04-20 Lead of

Global Cellular Communication (IIoT) in Motion

In ABB for 2 years; works with industrial connectivity

Participant 5 2020-04-20

2020-04-21

Vice President of Global Water & Wastewater

Sales for Drives

In ABB for 16-17 years, mainly in Water & Wastewater sales for

Drives

Participant 6 2020-04-22

2020-04-29

Head of Product Management & Digital Connectivity Tools

(1 year in the position)

Hosts global group of product managers; worked in various positions on R&D for Drives

Participant 7 2020-04-27 UK Digital Lead

in Motion (1 year in the position)

In ABB for 25 years; worked with internal sales, field marketing, channel management in Motion

Participant 8 Group interview

with participant 7

UK Product Manager for Drives & Softstarters (6 months in the position)

In ABB for 3 years; organizing product and service launching;

receiving feedback from customers, partners & internal

ABB

Participant 9 2020-05-04 Head of Smart Solutions*

Motion Services at ABB (1 month in the position)

In ABB for 9 years; worked in supply chain management, R&D,

front end sales

Participant 10 2020-05-12 Head of Product Line Manager

& Unit Manager for Center of Expertise

for Softstarters

In ABB for 16 years; worked in R&D, Product Management and

Global Product Management.

22 3.5 Empirical Interviewing Process

All the interviews were conducted via Microsoft online Teams meeting due to the participants being spread out in Denmark, Finland and the UK. When sending out email interview invitations, the authors maintained transparency by stating the research subject and attaching interview questions, together with mentioned managers (participants 1 & 2) being copied in the emails. The authors received all replies to participate in interviews except for one.

Throughout the process, the authors and the respondents used online interview meetings as a common platform used by both parties, and the authors respected if the respondent did not wish to share their screen. The authors also considered the different holidays in different countries and the one-hour difference between the UK and Sweden when arranging interviews. The authors tried to accommodate respondents by stating available dates and times, and maintaining good communications (Bell et al., 2019).

Written in the email and before each interview started, the authors informed the participants the interview was being recorded to get their consents. To establish mutual trust and let the information flow smoothly, non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) were also signed by the authors, so any sensitive information is non-disclosable. Before each interview, the authors browsed the interviewees’ LinkedIn profiles and Drive webpages, to increase the quality of the interview, as the authors could understand better what the respondent was saying (Bell et al, 2019). One of the respondents stated that it made him feel important as an interviewee; all participants gave positive feedback regarding the research topic and were delighted to participate in interviews.

During the interview, it was also important to keep an open mind and allow the respondents the space to openly discuss the topic (Bell et al., 2019), but also to guide the questions in order to finish within the time frame. This semi-structured interview format yielded rich and detailed data.

3.6 Analysis Methodology

Thematic analysis was used to assist the authors in processing the data. Immediately after each interview, the transcription was made and presented in Google Doc, so the authors could use them for the analysis process. To use thematic analysis, Ryan and Bernard (2003) recommend looking for certain concepts in the transcription of interviews: repetition, local

expressions, metaphors, transitions, similarities, differences, and theory-related material.

Keeping the concepts in mind, the authors paid extra attention when coding the field notes and the actual transcriptions of the interviews in order to find patterns and then identify themes and exceptions (Braun & Clarke, 2016; Pascale, 2011). First, the author observed

23

the data to identify patterns listed below in table 2, then bundled them according to the themes created in the literature review chapter. This was a back and forth process: when going through all the concepts in the literature review, it was needed to go back to the data pool and find events that match the pattern. This way, the authors were able to analyse the data with the corresponding theoretical concepts.

By using thematic analysis, the authors were able to manage the large volumes of data, reduce the risk of losing context, get closer to or become immersed in the data, then organize and summarize the interpretation of the data (Mills, Durepos & Wiebe, 2010). This method assisted the authors in presenting the data and reinforced the analysis.

24 3.7 Quality of Research

Credibility, confirmability, dependability and transferability are the criteria to examine

throughout the process to assess the quality of research (Bell et al., 2019).

Credibility & Confirmability

Credibility refers to the measures used to capture what is meant to be studied. In other words, how believable are the findings? Throughout the paper, the authors used peer-reviewed articles published in journals, and reports done by research organizations as background introduction of this paper. Using semi-structured and in-depth interviews allowed the authors to use follow-up clarifying questions, from multiple angles to explore different responses to gather accurate first-hand data (Saunders et al., 2016). Signing NDAs and being introduced by company managers helped build trust between the researchers and respondents and strengthen the veracity of the work. According to Salkind (2010), interview data quality may be affected during the process of transcription. Conducting interviews in English and transcribing the content immediately after the interviews ensured the quality of the transcriptions. To strengthen trustworthiness, the authors have described the operationalization process in detail.

According to Bell et al. (2019), confirmability refers to whether the researcher has allowed

personal value to intrude to a high level. As mentioned above, one of the authors was

performing an internship in the case company, however, that author was conscious that this was academic research and did not allow the internship to affect the quality of the research. In fact, the knowledge gained from that author’s internship actually contributed to the understanding of technical terms used when gathering data. Also, during the process, when there might be even the appearance of bias involved, both authors discussed and made the decision together on the basis of academic objectivity.

Dependability & Transferability

Dependability and transferability are assessed on whether the result of the study is replicable, in other words, are the findings likely to apply at other times; do the findings

apply to other contexts? (Bell et al., 2019) According to Saunders et al. (2016):

This [dependability] may be achieved, where possible, by using more than one researcher within a research project to conduct interviews or observations and to analyse data to be able to evaluate the extent to which they agree about the data and its analysis. (p.202)

Here, the methodology, data collection and analysis of the data used in this paper were agreed to by both authors. As to transferability, the authors listed items that future

25

researchers might consider if they were to carry out the same research. If the same research keywords are used when looking for previous research articles through the same search engines, the literature review would not vary drastically. The information about the company from its website and documents can be gathered differently because new information related to digital transformation will be updated due to constant technological development. If the case study is executed in the same company and divisions, with the same set of interview respondents and questions, the data collected, patterns and themes might not be exactly the same, but the findings will be pointed in the same direction. The analysis and the conclusion could differ due to the theories chosen may vary. (Adolfsson & Lindgren, 2015; Bell et al., 2019). In order to apply the findings to other contexts, research subjects related to customers’ role and DT in companies, future researchers should take the points mentioned into consideration when applying this paper to their work.

26

4. Empirical Findings

In this chapter, the authors used patterns that are observed from the interview data, and themes from literature review to present the empirical findings.

4.1 Value Creation

When asking the respondents their thoughts on value creation, due to their different professional backgrounds, the authors received various insightful answers. The Vice President of Water & Wastewater explained what he perceives as value is that with the knowledge accumulated over 15 years in the water industry, he can ‘pass on knowledge onto the sales guys’ to provide useful information to the companies on water process improvements, for instance, by showing owners how to set up drives correctly to achieve far better control for better water treatment. As he stated “I want to move it past the product sell, more into the solution sell, and becoming the trust advisor”(Interview, 2020.04.20).

According to the Lead of Cellular Connectivity, the motto “We turn the world while saving energy” represents the value ABB Motion and his role in cellular connectivity are trying to create. He further explained that motors and drives are used in all industries, and that “we want to bring Motion in sense that we also save the energy, because we consume electricity, so we want to make that motion in a way that with as less energy as possible.”(Interview, 2020.04.20) With that, the task in his role is to use cellular connectivity to connect and collect telemetric data from the devices, so that the data can be analysed, and cloud-based services can be enabled, which can also optimize the process of device software development. This will allow motors and drives to save energy, which is also the main value connectivity service can bring.

The Head of Smart Solutions shared that value comes from different sources. The original value proposal was to be able to control motor speed by adjusting electrical energy that is being used and that translates into energy efficiency directly. Today, the customer expectations are higher, there is more competition, and the technological differences that existed between manufacturers have almost vanished. She stated that “We can’t make business anymore from just making frequency converters aka boxes. Because there are other companies that make those too and they’re pretty good at it as well” (Interview, 2020.05.04). She further mentioned today’s value comes from different sources, ABB needs to continuously consider what value can ABB propose to the customers, and that without providing value to customers, a company will no longer be able to keep running.

Value creation is a continuous process in ABB, the Digital Lead for Motion in the UK mentioned that during his digital journey of introducing customers to the new digital

27

service, one of his concerns is how ABB can demonstrate the value even when the product’s condition is in good shape and does not show any down sign. Furthermore, he felt that having virtual meetings, walking customers through their digital assets will be a powerful add-on to the service. The Local Product Manager for Motion in the UK further agreed and added that customers would like to feel the worth of the money they have paid for the products or even beyond that, fixing the pain point in their operation.

Value creation can be created internally as well through sharing Drive’s digital transformation journey with other organizations within ABB. By sharing internally their experience on how to engage customers, and further how the feedback can be transformed into value in the product development process. Throughout the interviews, all participants were keen on giving recommendations to the new family member in Motion, Softstarter. The Vice President of HVACR for Drives pointed out that this included aligning more closely between Drive and SoftStarter divisions, so they have one digital ecosystem due to their closely-related nature. He mentioned: “When we get to the point where we have the same user interfaces, the same apps, and so on. That integration will also make it easier for the customers to choose how to control their motors” (Interview, 2020.04.17). The value can be created through this integration not only internally but externally as well.

4.2 External Stakeholder Involvement in Value Creation: Open Innovation

When answering how value is created, the respondents implied that the first step is to understand to whom the value is created. There is a complex customer channel structure behind each industry and in each market. According to the Vice President of HVACR:

If you look at the oil and gas [industry], ABB works directly with company X, when we

sell our products and services, we sell them directly to X. Whereas in HVACR, we are going through 3,4 layers of intermediaries, and in some cases, they receive a partner, then we have an additional layer on top of that. (Interview, 2020.04.17).

He further explained that these HVACR intermediaries are end-users, consultants,

contractors, OEMs, distributors, and more. Often, each kind of customer has different

needs, and values different things. To illustrate this, he used multiple examples and emphasized on the differences:

Building owners (end-users) care about the continuation of the operation. “A Building owner doesn’t care about the lead time because he gets a building and there’s a time schedule, he just has to meet the time schedule or there’s a penalty for being late” (Interview, 2020.04.17). Consultants care about the new things in the market (technology) to better serve the customers because their job is to write specifications about which product with what functionalities to use, and suppliers have to comply with the

28

specification. Contractors win a project at a given price, and then they will buy products for the project that are as cheap as possible and try to meet the specification as well. Adding extra value to the product functionality to save their costs would be beneficial to them. OEMs want the production process to be as fast and cheap as possible, “they might be willing to pay a little bit more if it’s easier, they can save working time in the manufacturing, and if they can get higher security that the products are there when they need them”(Interview, 2020.04.17). A stop in the production would be a huge cost for them. On top of everything, there is the geographical market to be taken into consideration. According to the Vice President of HVACR for Drives:

In country X, for HVACR, we are not going through partner network simply because there isn't a market structure that supports a dedicated HVACR partner network, whereas in country Y, all of our businesses are going through our partners for the segment. (Interview, 2020.04.17).

He further explained that partner network means that instead of directly approaching a customer, a company maintains good relationships with small medium size companies as partners. He strongly felt that it is necessary to look at the market structure and adapt their business model since, even if ABB is a big company, they cannot change how the market behaves.

As the Vice President of HVACR for Drives noted, “Customer is the one choosing the product, so we need to have an interaction with them to find out how we can get a better understanding of how they use the product” (Interview, 2020.04.17). Having a complex network of partners and customers requires elaborate processes to communicate and obtain feedback from them. Those processes can include direct and indirect interactions. When answering what kind of direct interactions ABB has with their customers, it was a common answer from the respondents: one of the most straightforward types of customer interactions happens at the front end through sales units, account and segment managers, product managers as well as other specialists whose expertise on specific topics may be needed during a meeting. Currently, direct interactions can take place in the form of email, phone calls and customer visits. The Digital R&D Manager in Finland mentioned even a phone application which allows the customer to give feedback quickly when they get a prompt asking ‘do you have any feedback?’ on their phone.

Direct interactions with customers also need to be strategic about how the front end communicates with them to find out customers’ pain points. As the Vice President of HVACR for Drives mentioned that the regional-level salesforce needs to be trained to have

29

the right dialog with the customers, so that customers have the opportunity to provide their feedback on improvements. Furthermore, the Vice President of Water & Wastewater mentioned that when he has a chance to go on business travel, he does not visit ABB local office, but visits customers’ sites. The reason behind is to observe the work of the customer's plant, installation of the assets and to ask questions about customers’ needs. Sometimes, the needs of a customer are not expressed by words, but through the observations walking around the factories. An example he used: One day he was walking around a pump OEM, and he had a conversation with a worker there and noticed them spraying ABB motors. He immediately commented: “We can do that by sending out the right-colored motors!” The worker responded: “Ok, but the feet of the motors are always sprayed and we have to spend time filing off that paint on the bottom so the motor fits perfectly on my pump skid.” The manager then went back to ABB factory and discussed it. They came up with a perfect solution using a magnet which covers the feet when they spray the motors. This way it saved the OEM several hours of work by observing customers’ plants. The Global Cellular Communication Lead in Finland shared a similar opinion about understanding customer’s needs. He mentioned, it is necessary to instead of having the mindset of selling a product, one should have a discussion with the customer about their pain points and show interest in customer’s problems. The Digital R&D Manager in Finland mentioned that they have even received design thinking training which is about listening to the customer in a systematic way and structuring the conversation in a useful direction. Other occasions of direct interaction that respondents mentioned are during some events, fairs or trade shows. The Finland Digital R&D Manager and the Vice President of HVACR said that they often have fairs at different locations of the world with various customers, partners, OEMs and so on. According to them, these actors would be very engaged and willing to participate in personal one-on-one discussions, seminars, workshops, etc. the UK Digital Lead mentioned also that direct interactions could happen through, for example, service engineer or application engineer in case there are big issues on customer’s site. Moreover, in some occasions customers would actively reach out to give direct feedback. He also mentioned that in the UK, ABB has such a high share in the water market, that the factories, channel partners would actively engage with ABB themselves to provide feedback from end users. Feedback is another form of value creation to retain the customers, as the Vice President of Water & Wastewater explained the importance of it: “When customers stop telling you how they feel, or if they are annoyed, not because they are suddenly happy now. They are just gone somewhere else, isn’t it?” (Interview, 2020.04.21)

When answering what indirect interactions ABB has with their customers, it was explained that those at the front end who have direct interactions with customers, pass the feedback and knowledge further in the organization which becomes indirect customer interactions.