“It’s to Protect the Country!”

The Everyday Performance of Border Security

in Sweden

Mette Skaarup

Peace and Conflict Studies Bachelor’s degree 15 credits Spring 2018 Supervisor: Dr. Stephen MarrThank you,

My deepest gratitude goes out to Michael Sundström and the participants who generously shared their time and stories with me. Without you this project would not have been possible. I hope that I have done you justice and I take full responsibility for any mistakes or misrepresentations. Thank you to all those unnamed individuals who shared observations and experiences with me during my field research. Your insight is much appreciated.

Finally, I would like to thank my supervisor, Steve, for showing us that academia can be relevant, beautiful, poetic, fun, and unruly, all at the same time.

What we have come to call a globalized world harbors fundamental tensions between opening and barricading, fusion

and partition, erasure and reinscription. These tensions materialize as increasingly liberalized borders, on the one hand,

and the devotion of unprecedented funds, energies, and technologies to border fortification, on the other. ― Wendy Brown: Walled States, Waning Sovereignty

ABSTRACT

In response to the humanitarian crisis of 2015, Sweden introduced ‘temporary’ border controls. The increasingly permanent controls warrant critical assessment and raise urgent questions: How is border security exercised in practice? What is the relationship between intent and practices on the ground? Which logics drive the border control? This study explores these questions through in-depth interviews with border guards and ethnographic field observations conducted at Hyllie station. Applying Foucault’s concept of biopolitics and Walters’ image of the border-as-firewall, the study critically probes the practices of border security and the logics that underpin it. The study argues that the Swedish border control acts as a (biopolitical) firewall. Yet, this conceptual framework alone cannot account for the multiple logics, rationalities, and objectives that intersect and drive the project of border control. The analysis suggests that biopolitics frames security as a rather monolithic, omnipotent performance of overarching state objectives. In reality, the exercise of border control is assembled ad hoc, constrained by the limits of available resources of the Swedish police and mediated by the agency of individual border guards. Finally, the study reflects on the exclusionary logic embedded in the practices of border control and stakes out paths for future research.

Key words: Sweden, borders, security, biopolitics, Foucault

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

EC European Commission

ECC European Economic Community

EU European Union

PACS Peace and Conflict Studies SIS Schengen Information System

LIST OF FIGURES

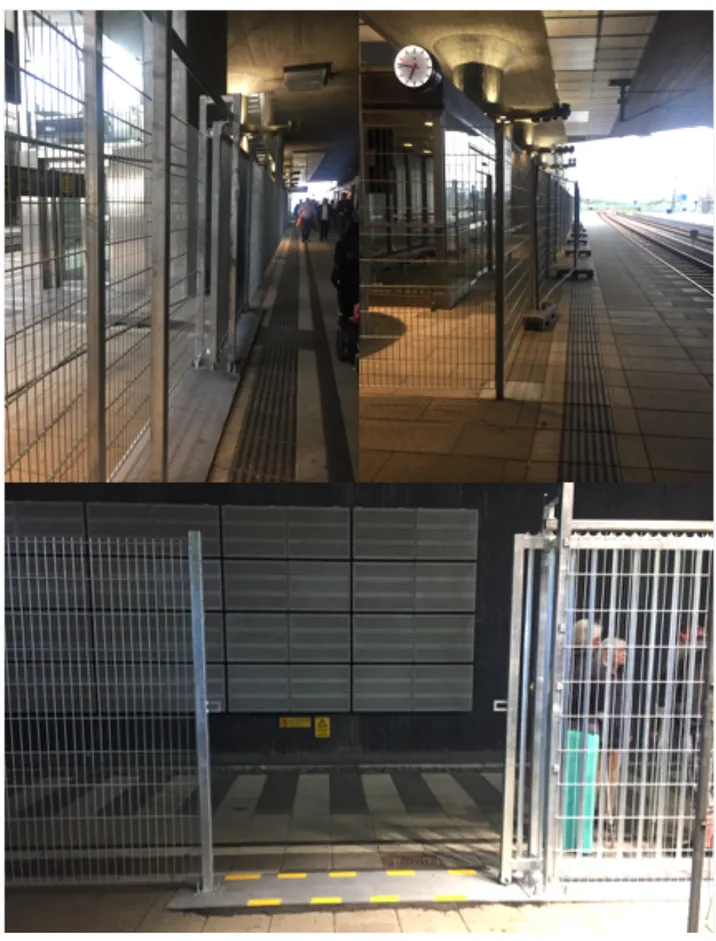

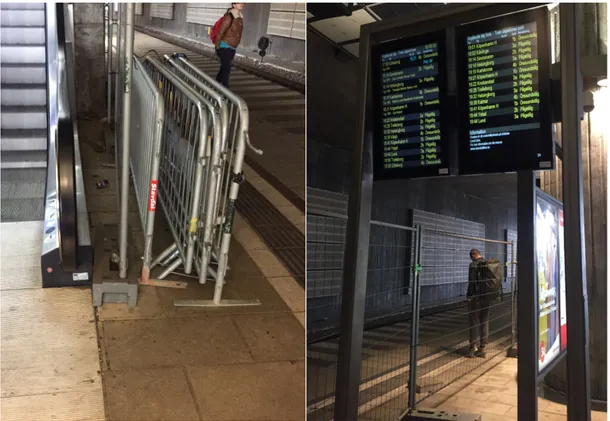

Cover page Hyllie station: Track 3 and 4

1 Map of Sweden

2 Schengen visa policy map 8

3 Hyllie station 26

4 Train tracks, Hyllie 27

5 Container for border guards at Hyllie 27

6 New fence at Hyllie 28

7 Old fence at Hyllie 29

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1 INTRODUCTION ... 1

1.1 RESEARCH PROBLEM AND AIM ... 2

1.2 PURPOSE AND RESEARCH QUESTIONS ... 2

1.3 RELEVANCE TO PEACE AND CONFLICT STUDIES ... 4

1.4 (DE)LIMITATIONS ... 5

1.5 THESIS OUTLINE ... 5

2 BACKGROUND ... 7

2.1 THE SCHENGEN AREA ... 7

2.1.1 History ... 7

2.1.2 The Schengen Information System ... 9

2.2 SWEDISH BORDER CONTROL 2015-2018 ... 9

3 LITERATURE REVIEW ...11

3.1 BORDER STUDIES ... 11

3.2 GOVERNING MOBILITY ... 12

3.3 BORDER SECURITY:TAKING BACK CONTROL ... 13

3.4 POSITIONING THIS THESIS ... 14

4 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK ...16

4.1 BIOPOLITICS ... 16

4.1.1 What is biopolitics? ... 16

4.1.2 How is biopolitics applicable to border security? ... 17

4.1.3 What is biopolitics missing? ... 18

4.2 THE BORDER AS FIREWALL ... 18

4.3 CONNECTING THE CONCEPTS ... 19

5 METHODOLOGY ...20 5.1 RESEARCH DESIGN ... 20 5.2 DATA COLLECTION... 21 5.2.1 Method ... 21 5.2.2 Selection of participants ... 22 5.2.3 Presentation of participants... 22 5.3 ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS ... 23 5.4 POSITIONING MYSELF ... 24

6 DATA ...25 6.1 RESEARCH SITE ... 25 6.2 RULES ... 30 6.3 CATEGORISATION ... 32 6.4 FILTERING ... 36 6.5 SECURITY HOLES... 38 7 ANALYSIS...42

7.1 HOW DOES THE SWEDISH BORDER CONTROL FUNCTION? ... 42

7.2 HOW DO BORDER GUARDS CATEGORISE AND REGULATE BORDER CROSSERS?... 43

7.3 WHAT IS THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN INTENT AND PRACTICE AT THE BORDER CONTROL? ... 44

7.4 HOW IS ‘SECURITY’ CONSTRUCTED THROUGH THE EVERYDAY PERFORMANCE OF BORDER CONTROL? ... 45

7.5 EVALUATION OF THE THEORY ... 46

8 CONCLUSION ...48

8.1 CONCLUDING REMARKS ... 48

8.2 SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER RESEARCH ... 50

REFERENCES...51 APPENDIX 1 ...59 APPENDIX 2 ...61 APPENDIX 3 ...63 APPENDIX 4 ...64 APPENDIX 5 ...65

1 INTRODUCTION

When I moved from Copenhagen to Malmö a few years ago, I used to jokingly say that I was just moving to a different part of Denmark. But the reintroduction of border control makes it clear that one is, indeed, entering a different country. In November 2015, Sweden – along with a handful other European nations1 - implemented temporary inner border control2, ending sixty years of Nordic free movement3 (Sveriges Radio, 2016; Øresundsinstituttet, 2017). The move responded to the arrival of thousands of mostly Syrian asylum seekers. It signalled a dramatic shift in Swedish policy, hitherto characterised by an extraordinary openness (Brännström, 2015; Kobierecka, 2017). Not only did the announcement draw headlines in Denmark and Sweden, it also garnered attention in international newspapers (Al Jazeera, 2015; BBC, 2015; The Guardian, 2015).

Europe’s new border landscape challenges the Schengen vision of free movement and presents immense obstacles to those seeking better lives in Europe. In 2017, the EU Commission recommended that Sweden “phase out the temporary controls” (EC, 2017). Instead, the government extended them on the basis of ‘the serious threat4 to national security’ (Polisen, 2017a). The controls look less temporary by the day. Prime Minister Stefan Löfven has cautioned that inner border controls will ‘probably not disappear’ any time soon (Regeringen, 2017). His political party5 declared that: ‘We guard Sweden’s security – the Swedish model will be developed not phased out’6 (Sydsvenskan, 2017a).

1 See EC, 2018c for a comprehensive list of EU Member States’ notifications of temporary reintroduction

of inner border controls.

2 [inre gränskontrol] ’Inner border’ denotes a border with another Schengen country, while ’outer border’

denotes a border with a non-Schengen country.

3 [nordisk pasfrihed] Between 1860 and 1914, there was complete passport freedom between Denmark,

Sweden and Norway. In 1954, the Nordic Passport Union was created, implementing passport freedom between Sweden, Denmark, Norway and Finland. Iceland entered the Union in 1955, and the Faroe Islands entered in 1966.

4 [allvarliga hotbild] (Polisen, 2017a). 5 The Social Democrats.

A solid fence has been fused into the ground at Hyllie station. These developments indicate that the ‘temporary’ controls might transform Sweden for good.

1.1 Research Problem and Aim

Most research on borders emphasises that their primary function is to provide (real or imagined) security. The border performs this function as a filter, categorising travellers as desirable/undesirable (Popescu, 2011; Walters, 2006a). This study aims to investigate the exercise of security and biopolitics at the Swedish border. Swedish border policies illuminate a global shift in thinking about security towards ‘risk management’ and the ‘securitization’ of individuals (Bigo, 2002; Häkli, 2015; Popescu, 2011). Border literature now discusses smart borders (Salter, 2004), ‘remote-control’ borders (Guiraudon & Lahav, 2000), mobile borders (Lambert & Clochard, 2015), networked borders (Walther & Retaillé, 2015), embodied borders (Popescu, 2011) and cooperative ‘21st century borders’ (Longo, 2016).

The categorisation and regulation of individuals, which serves to protect the state population, represents a form of ‘biopolitics’. According to Marr (2012:84), “[o]ne of the primary purposes of biopolitics is to categorise populations within a given territory in order to better manage, regulate or govern the body politic”. I argue that this raises a string of urgent questions: How are these mechanisms exercised in practice? How are border guards7 trained? Which rules do they follow? Which logics guide border security practices? The thesis explores these issues by constructing what Murray calls a montage “derived from ‘empirically grounded vignettes’” (2003:442); a mosaic of stories and observations of the everyday performance of border security.

1.2 Purpose and Research Questions

The ‘vignettes’ are collected through ethnographic field research, presented in thematic clusters and analysed using the theoretical framework of biopolitics. The purpose is to

7 Throughout the study, I will use the term ’border guards’ as an umbrella term for civilian guards (pass

controllers and border controllers) and police officers who work at the border. When distinction is necessary, I refer to either ’civilians/civilian guards’ or ’police/police officers/border police’.

explore how security is exercised and how the idea of biopolitics connects to the “practices that unfold on the ground” (Häkli, 2015:99). To this end, the study asks the central question:

How is ‘security’ constructed through the everyday performance of border control?

Based on work by Scheper-Hughes, ‘everyday performance’ describes the “little routines and enactments” of border security (in Scheper-Hughes & Bourgois, 2004:253). Following Foucault, I conceptualise security as ‘the management of an indefinite series of mobile elements’ through measures that work on material givens to maximise perceived positive elements and minimise risky or inconvenient elements (2007: pp.19-20).

The central question is explored through the case of Swedish border control. The following operational questions will help answer it:

1) How does the Swedish border control function?

To analyse how border security is exercised, it is necessary to outline the ‘nuts and bolts’ of everyday border control. This question addresses the institutional organisation and the routines of border control, which offer important clues to its underlying logics.

2) How do border guards categorise and regulate border crossers? This question addresses the how of biopolitics: How border guards perform border security by categorising and filtering people at the border.

3) What is the relationship between intent and practice at the border control?

This question addresses potential dissonances between how the border control should function and how it actually functions. The findings facilitate the final discussion of how security is constructed and exercised at the Swedish border control.

Taken together, these questions construct a ‘montage’ of the performance of border security and biopolitics at the Swedish border control. The analysis offers reflections on the relevance of biopolitics in relation to the Swedish case.

1.3 Relevance to Peace and Conflict Studies

Why is it socially and theoretically relevant to study border control? And how does it relate to Peace and Conflict Studies (PACS)?

First, this study documents a very specific historical moment. In twenty years, we might look back at this as an anomaly in Schengen’s history –or as the time that Europe abandoned Schengen. Yet, research on the Swedish border control is scarce (see e.g. Barker, 2018; Frank, 2014; Hansson, 2017) and I located no studies that explore the border from the ‘bottom-up’.

Second, this study builds on an ongoing effort to decipher what the world’s borders “represent for us and what they do to our lives” (Amilhat Szary & Giraut, 2015:2). Borders express a human need for “order, security and belonging” and our “desires for sameness and difference, for differentiating between the ‘known’ and the ‘unknown’ and between ‘us’ and ‘them’” (O’Dowd, 2001:67). Questions of othering (Said, 1978), security discourses (Buzan et al., 1998; Cohn, 1987), structural violence (Galtung, 1969), and exclusion (Scheper-Hughes & Bourgois, 2004) represent core PACS themes.

In extension, this study identifies a gap in PACS literature on borders, and demonstrates a need to broaden the scope of PACS to include border research. Border research calls for interdisciplinarity and “the creation of a shared space” if we wish to contribute to the evolving debate on borders (Newman, 2006:154). PACS explore conflict, structural violence and the means of obtaining lasting peace (Lottholz, 2017; Showkat Dar, 2017:45). ‘Structural violence’ denotes the indirect violence “built into the structure [which] shows up as (…) unequal life chances” (Galtung, 1969:183) or “social exclusion and humiliation” (Scheper-Hughes & Bourgois, 2004:1). Borders illustrate and produce structural violence, exclusion and othering (Andreas, 2003; Newman, 2006). Yet, the bulk of border research is found in journals of human geography, international relations or specialised journals, such as the Journal of Borderland Studies. PACS

journals8 feature little border research (see e.g. Arieli, 2015; Barzilai & Peleg, 1994; or Rider & Owsiak, 2015). Notably, anthropological peace research offers some insight into the links between borderings, mobility and inclusion/exclusion (see e.g. Bräuchler & Ménard, 2017). The study seeks to add to this body of literature and to fill the gap in PACS literature by linking border security to the performance of biopolitics.

1.4 (De)limitations

The study is limited in a number of ways. It focuses on the Swedish border control at Hyllie, which limits its generalizability. The research design precludes other approaches, such as a narrative analysis or the collection and analysis of statistical data on border crossings. It means that all the data was filtered through and shaped by the researcher’s personal biases. The data is limited to a period of two months (mid-March to mid-May, 2018), eight in-depth interviews and 14 hours of observation. The theoretical framework is limited to the concepts of biopolitics and the border-as-firewall. The theory does not address the question of how the Swedish border control is viewed and constructed by the media; whether a process of securitization takes place; or what the Swedish border illustrates about state sovereignty and territory in a globalised world (see e.g. Brown, 2010 and Sassen, 2015). Instead, this study focuses on the exercise of security and biopolitics at the Swedish border control.

1.5 Thesis Outline

The study is organised into eight chapters. Following this introductory chapter, Chapter two offers a brief background of Schengen and Swedish border control. The third chapter presents relevant literature on borders, mobility and border security. Chapter four discusses the concepts of biopolitics and the border-as-firewall, which constitute the study’s theoretical framework. Methodology and data collection are discussed in Chapter five, followed by the presentation of data in Chapter six. Chapter seven unfolds the

8 The Journal of Conflict Resolution; International Journal of Conflict Management; Journal of Peace

analysis of the data using the theoretical framework and reflects on the relevance of biopolitics in the study of contemporary border security. The last chapter offers concluding remarks and suggestions for further research.

2 BACKGROUND

For three decades, EU officials have worked arduously to craft (the myth of) a single, borderless “European space” (Zaiotti, 2011:555). The re-emergence of European border controls raises doubts about Schengen’s future. This chapter presents a brief history of Schengen before outlining key developments in the reintroduction of Swedish border control9. The chapter seeks to situate the Swedish case within a wider European context.

2.1 The Schengen Area

2.1.1 History

For three decades, EUrope10 has chased the dream of a borderless union. Following World War II, six European countries11 founded the European Economic Community (ECC) (EC, 2018a; EU, 2018b). The ECC nations12 signed the first Schengen Agreement in 1985 to “enable the European working population to freely travel and settle in any EU state” (EC, 2018b; EUR-Lex, 2009). The Schengen Area was gradually established throughout the 1980s and 90s. In 1993, ECC changed its name to the European Union (EU). Today, Schengen comprises twenty-six countries13. Sweden joined in 1996.

Schengen prescribes the abolition of internal border controls; common rules for external borders; uniform visa procedures; enhanced police cooperation; and a member database called the Schengen Information System (SIS) (EC, 2018b; EUR-Lex, 2009). In exchange for the abolition of inner border controls, Schengen promises to ‘tighten’

9 I direct the reader to Appendix 1 for a more comprehensive timeline, which chronologically outlines

developments between 2015 and today.

10 To distinguish the geographical area called Europe from the political and economic institution of the

European Union, Vaughan-Williams (2015) employs the term ‘EUrope’ when he speaks of the European Union as an entity.

11 Belgium, France, Italy, Germany, Luxembourg and the Netherlands. 12 Minus Italy.

controls at external borders (EC, 2018b), fortifying the walls around ‘Fortress Europe’ (Özdemir & Ayata, 2017:1). The emergence of ‘serious threats to public policy or internal security’ may warrant the exceptional introduction of temporary internal border controls (EC, 2018b), which is what happened in 2015.

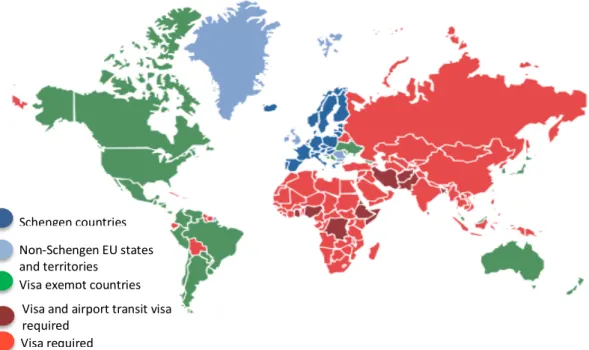

Schengen propagates liberal values of “freedom”, “human rights” and “equality” (EC, 2018a). Yet these privileges are only granted to those allowed to enter the area. Zaiotti suggests that this raises uncomfortable questions about the ‘exclusionary nature’ of the EU “and its claim torepresent a space of freedom. Freedom for whom? And what about those left out?” (2011:554). According to Schengen visa policies, some non-EU citizens are required to hold a visa when travelling within Schengen (EC, 2018d). The map below (fig. 1) shows that nationals from practically every country to the east and south of Europe need visas while Australia, New Zealand and most of the Americas are visa exempt. It is perhaps worth reflecting on the fact that the visa-exempt countries coincide with what Huntington dubiously terms ‘Western civilization’14 in his disputed Clash of Civilizations (1996: pp.24-29).

14 Huntington is not exactly clear on which ’civilization’ he perceives Latin America as belonging to, but

he does view it as “the immediate offspring of another long-lived civilization”, namely Europe (1996:44).

Visa and airport transit visa required

Schengen countries Non-Schengen EU states and territories

Visa exempt countries

Visa required

2.1.2 The Schengen Information System

SIS “is a highly efficient large-scale information system that supports external border control and law enforcement cooperation in the Schengen States” (EC, 2018e). In lieu of internal border checks, SIS is supposed to ensure internal security in Schengen. Police and border guards can use the system to access SIS alerts on “certain categories of wanted or missing persons and objects” (EC, 2018e). Twenty-six of EU’s member states (minus Ireland and Cyprus) and Switzerland, Norway, Liechtenstein and Iceland operate with SIS (EC, 2018e). The Swedish border police use the system to run so-called ‘deeper’ or ‘second-line’ checks on ‘irregular’ passengers. A ‘deeper’ check means that the police scans a person’s passport or contacts relevant foreign authorities to investigate whether the person is flagged in the system.

2.2 Swedish Border Control 2015-2018

In 2015, “Sweden embarked on one of the largest self-described humanitarian efforts in its history, opening its borders to 163,000 asylum seekers fleeing the war in Syria” (Barker, 2018:1). Prime Minister Löfven declared: “My Europe takes in people fleeing from war, my Europe does not build walls” (The Guardian, 2016). Two months later, Sweden introduced full-time border controls at Helsingborg, Lernacken15 and Hyllie16 in the Skåne region (see fig. 1) along with partial controls at other sites.17 Five other EU member states18 currently maintain border controls (EC, 2018a; EC, 2018b). Löfven has cautioned that the European border controls will likely remain as long as ‘we do not have a working system’ (Regeringen, 2017). The developments have stimulated debates on whether Schengen is on the brink of collapse (see e.g. DW, 2016; Independent, 2015). In September 2015, thousands of asylum seekers sought towards Sweden. Over 24,000 arrived in September and 39,000 in October. Most of them fled the Syrian war, which has forced over ten million Syrians to leave their homes (IDMC, 2017; UNHCR,

15 The border crossing by the Øresund Bridge, which also includes a Customs department. 16 The first Swedish train station en route from Denmark.

17 Sweden shares land borders with Norway and Finland, and maritime borders with Germany, Denmark,

Finland, Poland, Russia, Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia.

2016).19 Sweden declared the situation a ‘national special event’ [nationell särskilt händelse] (Sydsvenskan, 2015) and introduced temporary inner border controls on November 12. Police officers from greater Sweden travelled to Malmö to ‘manage’ the incoming refugees. In December, ID checks were introduced on trains and busses from Denmark (Øresundsinstituttet, 2017).20 When Sweden introduced carrier sanctions21 in January, every train passenger coming from Denmark had to pass an ID control (Sveriges Radio, 2016; Øresundsinstituttet, 2017).

On April 7, 2016, a truck attack sent shockwaves through Sweden (NYT, 2017). Löfven announced that the government would “totalise” the border control (TV2, 2017) and the border police hired 72 civilian border guards. By 2017, the number of asylum seekers had decreased by 80 percent22 and the parliament abolished ID controls in favour of intensified border control. The EU informed Sweden that it could not extend the control on the basis of a ‘national special event’ any longer (Øresundsinstituttet, 2017). Sweden changed the justification for the control to the ‘serious threat’ to national security (Polisen, 2017a). In EU language, it switched from a control based on “events requiring immediate action” to “foreseeable events” (EC, 2018a, emphasis in original). In May 2018, the Swedish government extended the border controls until November 11 (Sydsvenskan, 2018a). The controls have been financially23 costly (Øresundsinstituttet, 2017) and exasperate a nation-wide problem of resource shortage in the Swedish police (Riksdagen, 2018). The reintroduction of European border controls furthermore revealed deep cracks in the Schengen foundation.

19 This thesis does not go into depth with the complexities of the Syrian conflict, which have been

extensively covered elsewhere (see e.g. Corstange, 2018; European University Institute, 2016; Jabbour et al., 2018; Phillips, 2015; Warrick, 2015).

20 ID control ensures that a person carries valid ID while border control assesses whether a person is

allowed to enter.

21 Carrier sanctions hold transportation operators responsible for ensuring that all passengers carry valid

ID.

22 Compared with numbers from 2015.

23 The Danish national train company, DSB, reported a cost of 70 million Danish kroner for the ID control,

the cost of which was split evenly with Skånetrafiken, in 2016. In December, 2016, the Swedish Government set aside up to 139 million SEK to compensate train, ferry and bus companies for their ID-control-related profit losses.

3 LITERATURE REVIEW

This chapter seeks to familiarise the reader with current debates in border scholarship and significant developments in security thinking. It opens with a brief overview of border studies before presenting work on the restriction of mobility and (border) security.

3.1 Border Studies

At a time when globalisation scholars had predicted the extinction of borders (Amilhat Szary & Giraut, 2015:3), they “continue to separate us” (Newman, 2006:144). In fact, we are surrounded by borders—consider airports (Walters, 2006a), ‘remote control’ visa offices (Guiraudon & Lahav, 2000), transnational banks (Sassen, 2015), gated communities and ID controls (Walters, 2006b). Classic border studies viewed borders as static demarcations of territory (see e.g. Blake, 2000; Minghi, 1963; Prescott, 1965). Today, the Westphalian system has given way to a ‘post-Westphalian’24 and globalised world (Brown, 2010: pp. 21-23). Border scholarship changed radically with the introduction of the concept ‘bordering’, which denotes socio-political processes of border-making within society through discourses, institutions and media representations (Kolossov & Scott, 2013: pp.2-3). The field increasingly adopts an interdisciplinary focus on culture and discursive processes (see e.g. Mekdjian, 2015; Özdemir & Ayata, 2017). The ‘cultural turn’ in border literature (Özdemir & Ayata, 2017:2) advances the idea that borders are symbolic and material, simultaneously embodying exclusionary governance (Walters, 2006a:187), (eroding) state sovereignty, and fantasies of control and security (Brown, 2010). Borders still serve practical functions of division but they are simultaneously mobile, multifunctional and marked by complex re/debordering processes (Amilhat Szary & Giraut, 2015).

24 As Wendy Brown writes, a post-Westphalian order “is not to imply an era in which nation-state

sovereignty is either finished or irrelevant. Rather, the prefix ’post’ signifies a formation that is temporally after but not over that to which it is affixed.” (2010: 21).

3.2 Governing Mobility

Globalisation facilitates the increased mobility of people, goods, services and information (Andreas, 2003; Brown, 2010; Chalfin, 2007). According to Salter, the ‘problem of borders’ is “a result of two powerful governmental desires: security and mobility” (2004:72). The desire to facilitate ‘desirable mobility’ conflicts with the desire to regulate ‘undesirable mobility’, which supposedly brings crime and dangerous Others (Häkli, 2015; Salter, 2004). The function of security in a post-9/11 world (Jackson, 2005) has shifted towards ‘risk management’ and the ‘securitization of everyday life’ (Häkli, 2015:88; Popescu, 2011: pp.100-101). The shift manifests as increased law enforcement budgets; advanced surveillance, tracking and information technologies; stricter visa policies; extended inter-state cooperation; increased use of biometric technologies and restriction of mobility (Andreas, 2003; Brown, 2010; Popescu, 2011). Andreas (2003:78) suggests that states are restructuring their border practices (‘rebordering) to prioritise policing over military-economic purposes with the aim of regulating ‘clandestine transnational actors’.

The policing of borders raises important questions about the logics that motivate border guards. According to Häkli, guards hold discretionary powers, which turn the moment of ID verification into a personal and somewhat subjective assessment (2015: pp. 93-97). In a study of the ‘dispositions’ of EU border guards, Bigo found that border guards and police inhabit a security management ‘universe’ (2014:213) characterised in terms of ‘filtering’, ‘separating’ of il/legal travellers, and ‘managing’ flows of people (2014:211). The interviewed guards reject the idea that borders can be ‘made impermeable’. According to Bigo, they rationalise their roles through a logic of justice, policing and risk management; they protect (good) migrants against exploitative criminals and they protect the ‘inside’ from ‘illegals’ (Ibid., pp.213-214). He critiques the idea of securitization and argues that security discourses are usually formed retrospectively to justify practices (2014:211).

3.3 Border Security: Taking back control

The policing of borders goes hand in hand with the EUropean securitization of immigration (Bigo, 2002). Certainly this applies to Schengen, which couples a rigid external border regime with a discourse that conflates immigration with danger (see e.g. EC, 2018b; EC, 2018d; Schindel, 2016; Zaiotti, 2011). According to Bigo, this discourse extends beyond right-wing propaganda and racism:

Securitization of the immigrant as a risk is based on our conception of the state as a body or a container for the polity. It is anchored in the fears of politicians about losing their symbolic control over the territorial boundaries (…) It is based, finally, on the "unease" that some citizens who feel discarded suffer because they cannot cope with the uncertainty of everyday life. This worry, or unease, is not psychological. It is a structural unease in a "risk society" framed by neoliberal discourses in which freedom is always associated at its limits with danger and (in)security (2002:65).

Brown similarly argues that the desire for security “is fuelled by populations anxious about everything from their physical security and economic well-being to their psychic sense of ‘I’ and ‘we’” (2010:69). Both imply that this discourse elucidates deep-seated feelings of the loss of control; fears of losing symbolic territorial control, the uncertainty of everyday life and the ‘ungovernability’ of a globalised world (Brown, 2010:24). The perceived loss of control motivates shows of force - policing, blockading, walling - along with policies designed to regulate mobility (Andreas, 2003; Brown, 2010:24).25

When Bigo represents the ‘state as a container for the polity’ (2002:65), he invokes Foucault’s analysis of biopolitics26. In essence, biopolitics are mechanisms that regulate, categorise and separate populations. For the state to best regulate and govern27 populations, it must obtain knowledge about them (Foucault, 2004, 2007, 2010). Barker (2018:28) argues that the ‘inclusionary’ policies of the Swedish (national) state are contingent on the exclusion of others. She explains that the welfare state embodies a logic of productivity in which members of society contribute to national growth. Thus,

25 Tellingly, the Brexit Leave campaign chose ‘Take back control’ as its slogan (Daily Express, 2016). 26 I direct the reader to Ch. 4 for a more extensive introduction to the concept of ’biopolitics’.

27 It should be noted that governing refers to all forms of conduct, not just state governance (Foucault, 2007,

“Sweden is deporting failed asylum seekers because they are considered a potential drain on the welfare state” (2018:29).

Biopolitics emerged within a certain ‘art of government’, or ‘governmentality’28 (Foucault, 2007:383; Lacombe, 1996:347). Work by Walters (2006a, 2006b), Bigo (2014) and Chalfin (2007) shed light on the ‘governmentalities’ that underpin European border security. Walters (2006a) suggests that the ‘rebordering of the state’ (policing of mobility) might constitute what Foucault calls an ‘event’: “moments when an existing regime of practices is reinvested, co-opted and redeployed by new social forces and governmental rationalities” (2006a:188). 29 To explain contemporary borders, Walters invokes the image of the border-as-firewall (2006a, 2006b), which I elaborate in Chapter 4. Bigo argues that the logic of filtering develops a biopolitical governmentality, which discriminates against some populations on the basis of statistical risk calculation (2014:220). The result is a ‘politics of indifference’ that dehumanises certain population groups (Ibid., 221). Chalfin approaches the issue from ‘the bottom up’. Based on ethnographic field work, she investigates material modalities of governance at the Port of Rotterdam, suggesting that “the means of exercising authority is very much strategic and symbolic rather than in any way comprehensive” (2007:1618). Chalfin explores issues of control, governance, regulation and management of border flows. She seeks to understand grids of governmental logics, “the vast conglomeration of personages and protocols, objects and techniques, ontologies and epistemes through which power makes itself known” (2007:1613). She creates an instructive dialogue between Foucault’s theoretical ideas and on-the-ground practices.

3.4 Positioning This Thesis

Classic border research reinforced a tautological relationship between borders, sovereignty and territory (Amilhat Szary & Giraut, 2015:3). Contemporary border studies

28 Foucault interprets this ‘art of government’ as a liberal one. According to Lacombe (1996:347), Foucault

did not conceive of liberalism “as a political theory or a representation of society” but as an 'art of government' or a governmentality, “that is, as a particular practice, activity and rationality used to administer, shape, and direct the conduct of people”.

29 Foucault’s method of identifying and tracing these ‘events’ is called genealogy. In short, the purpose of

genealogies is to study the ’events,’ which establish what will come to be viewed as self-evident, universal and necessary (Walters, 2006a:188).

increasingly take the form of ethnographic case studies, which is where this study fits in. The reading of relevant literature points to two research gaps: First, there is a clear lack of literature on the reintroduction of Swedish border control. Second, there is a lack of case studies on seemingly non-violent and ‘unspectacular’ border sites. The bulk (though not all) of the case-based research focuses on ‘spectacular’ and directly violent border sites, hotspots and the extra-territorial off-shoring and outsourcing of EU bordering practices (see e.g. Brambilla, 2015; Lambert & Clochard, 2015; Sidaway, 2002; Vaughan-Williams, 2015; Özdemir & Ayata, 2017). It remains important to study these violent cases, but the spectacles should not divert attention from the everyday practices, which come to be accepted as normal. I argue that it is equally important to probe the “institutionally embedded discretionary powers” exercised at seemingly ‘unspectacular’ borders (Häkli, 2015:97). The Swedish border control entails the literal policing, regulation and exclusion of Others. It reinforces the criminalisation of immigration30 presumably for the sake of keeping the national state secure and pure (Barker, 2018). Border control was presented as an exceptional short-term instrument to handle incoming war refugees in 2015. Two and a half years later, Sweden has paved the way for permanent control with continuous extensions, tighter asylum policies (Regeringen, 2016) and a permanent fence at Hyllie. Put differently, Sweden is normalising border control (Barker, 2018:55). Foucault calls for the critical questioning of the moments when practices come to be viewed as self-evident and necessary: “We must be present at the birth of ideas and the explosion of their force, and not in the books that state them, but in the events in which they manifest their force” (2007: pp.374-375).

30 For an introduction into the concept of ’crimmigration’ (the criminalisation of immigration) in the

4 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

This chapter functions as a conceptual road map. The first section outlines the meaning of biopolitics. Following Walters’ advice that it is not “particularly helpful or productive to turn particular thinkers into self-contained packages” (mf, 2013:2), the second section adds an instrument to the ‘toolbox’ in the form of the border-as-firewall image. These concepts facilitate an understanding of how ‘security’ is constructed through mechanisms of categorisation and regulation at the Swedish border control.

4.1 Biopolitics

4.1.1 What is biopolitics?

Foucault explored “the effects and the ‘how’ of power” (Fontana & Bertani: 2004:274). He rejected the idea that you can ‘have’ power. Power produces effects; reality, rituals of truths, the individual as subject, knowledge about this subject (Lacombe, 1996:337). Power acts as a strategy, which materialises as it is exercised (Foucault, 2004: pp.23-41), working through “dispositions, manoeuvres, tactics, techniques, functionings” (Foucault, in Walters, 2006b:144). Biopolitics are regulatory mechanisms, or technologies of power (Foucault, 2004:243), concerned with the well-being, security, and risk management of a given population. It aims to enable desirable traits, such as healthy and productive populations.31 For institutions to perform regulatory practices, the population must be made legible. Institutions must obtain knowledge in order to better govern and regulate the population (Foucault, 2004, 2007, 2010).

The driving logic behind the birth of biopolitics was the emergence of 19th century European ‘State racism’ (Foucault, 2004: pp 65-84). Foucault’s genealogy of racism and

31 The aim of producing healthy and productive populations links the logics of biopolitics inextricably to

biopolitics brought critical insight into “the way in which racism becomes constitutive of the formation of modern society in Europe” (Nishiyama, 2015:331). In Foucault’s own words, State racism became “the administrative prose of a State that defends itself in the name of a social heritage that has to be kept pure” (2004:83). Some contemporary interpretations add a postcolonial perspective to Foucault’s (Eurocentric) analysis (see e.g. Nishiyama, 2015).

Governing practices flow from grids of underlying rationalities that Foucault calls ‘governmentality’. According to Senellart, biopolitics works within a largely liberal framework of governmental rationality (2007:383). Foucault describes governmentality as “the way in which one conducts the conduct of men” (2010:186). Governmentalities link disciplinary and regulatory technologies: “It is through disciplines, normalization and bio-power that welfare can be improved and populations governed. At the same time, these forms of government enhance the power of the state” (Simons, 1996:40). Institutions (such as the border) constitute sites of “micro-governmental rationalities,” which are part of wider grids of governmentalities (Simons, 1996:37).

4.1.2 How is biopolitics applicable to border security?

It remains difficult to flesh out a clear theory of biopolitics but this does not dampen the concept’s appeal. Its central strength is that it uniquely and innovatively captures a cluster of interconnected historical developments and phenomena: regulation and categorisation of populations, governance, power, State racism. The idea motivates a critical investigation of the logics that guide seemingly banal everyday practices, looking beyond any one individual or situation (Foucault, 2004, 2007; Woermann, 2012). I suggest that border security represents a mechanism of biopolitics. By this I mean that ID checks categorise individuals and make them legible in order to govern and exercise power upon them. Legibility32 enables categorisation such as ‘citizen’ or ‘asylum seeker’. Categories facilitate the exercise of power as guards decide whether to grant or deny entrance.

Popescu cautions that when states incorporate borders into everyday life for the sake of security, “it means acquiring power to order everyday lives” (2011:114). Returning to Foucault’s analysis, the power exercised through border control produces subjects,

32 For a slightly different and highly interesting use of the term legibility, see J. C. Scott’s Seeing Like a

knowledge about these subjects and a reality that legitimises this process. The regulatory practices of border security are underpinned by certain (state) governmentalities. Although security routines are seemingly guided by neutral rules and rational risk calculations, they are ripe with assumptions and values. As Häkli points out, “the apparent routine character, the neutral technicalities and smoothness of passport checking, effectively conceal the politics embedded in the power-laden institutional framing of border control” (2015:96). An analytical approach guided by the concept of biopolitics needs to consider the logics that guide the everyday practices of regulation.

4.1.3 What is biopolitics missing?

Apart from conceptual fuzziness, biopolitics has certain weaknesses. Bigo and Guild argue that Foucault overemphasised “the capacity and the will of control of national governments, their capacity to decide and to affect the life of everybody” (2005:3). Another common critique of Foucault’s analysis of power is that it risks undermining individual agency and subjectivity by diverting the focus to underlying logics (Woermann, 2012: pp.113-117). The idea of larger grids of government rationalities risks obfuscating the ad hoc decision-making by individual agents. Decisions might be influenced by a range of external factors, which have little to do with the logics of population regulation (stress, weather, tiredness, misunderstandings, personal beliefs). In practice, these dynamics manifest as a dissonance between the practices on the ground and the ideas of what the practices ought to do; what Marr calls a “‘leaky’ biopolitics” (2012:84). To address the ‘conceptual’ leakage and investigate if the border does what it is supposed to do, I supplement biopolitics with Walters’ concept of the firewall.

4.2 The Border as Firewall

Walters argues that contemporary borders act as ‘firewalls’, which differentiate “the good and the bad, the useful and dangerous, the licit and the illicit” (2006a:197). The metaphor is highly useful: A firewall is a digital network security guard, positioned at the point of entry between a private network and the outside, which all incoming and outgoing data passes through. It reads and filters data packages on the basis of preconfigured security rules, accepting legitimate packets and discarding illegitimate ones. Firewalls are crucial

for network security but they often have ‘security holes’ (Liu, 2011: 1). If the border acts as a firewall, border crossers constitute ‘data packages’. They are categorised into il/legitimate categories on the basis of inter/national security rules, using the ID as a ‘password,’ which facilitates the verification of data. Without valid ID, an aspiring border crosser will either be rejected or taken aside for a deeper check. The metaphor “breaks with geographical space, just as it breaks with state space, and moves us closer to the digital, the informational” (Walters, 2006b:151). It demonstrates that the new border is not a wall, but a filter that aspires – “frequently with mixed results” (Ibid.,153) - to reconcile the tension between security and mobility (Ibid.,152). The firewall follows an ever-dynamic logic of ‘updates’ and ‘patches’ (Ibid.,153).

4.3 Connecting the Concepts

The firewall differentiates good/bad data to protect a network from infiltration. Biopolitics differentiates national/foreigner to protect populations from infiltration and produce ‘healthy and pure societies’ (Foucault, 2004: pp.239-263). Border controls similarly have security holes that warrant updating. For this reason, I suggest that the ‘firewall’ is useful, not only as an image of the border, but as an image of biopolitics. Imagining biopolitics as a firewall adds a timeliness to the concept by supplementing the language of health with the language of technology. The firewall furthermore invites consideration of the permeability of the border without abandoning the idea of security rules. In other words, it facilitates a discussion of the dissonance between intent and practice.

5 METHODOLOGY

This chapter outlines the study’s methodological approach. The first section explains the research design, while the second section outlines the methods of data collection and analysis and presents participants. The last two sections reflect on ethics and researcher positionality.

5.1 Research Design

This study is an ethnographic case study. It employs ‘typical’ ethnographic methods of data collection (field research and interviews) to study the behaviour and experiences of Swedish border guards who could be termed a ‘culture-sharing group’ (Creswell, 2007: pp.68-72). The study does not seek to understand the culture of border guards but to explore the issue of border security through the case of Swedish border control. The control at Hyllie constitutes a bounded system (Creswell, 2007:73), which is investigated using multiple sources of information (interviews, observations, news articles, official statements). The data is presented in four clusters, based on a list of preliminary themes (see App. 4) compiled from the interview transcripts. The four clusters represent what I have identified as the four main elements of the firewall: (Security) Rules, Categorisation, Filtering, and Security Holes (see Sect. 4.2). The data is analysed thematically in accordance with the theoretical framework. Compared with ‘typical’ case studies, this study focuses less on chronological events and ‘lessons learned’ and more on the experiences of the participants (Creswell, 2007: pp.73-75).

5.2 Data Collection

5.2.1 Method

The data is based on observations made on the Øresund train and at Hyllie station along with eight formal interviews. I conducted semi-structured in-depth interviews to understand how border guards exercise and experience border security. I conducted two pilot interviews (included in the study) by phone based on a list of questions (Appendix 2). Subsequent interviews were guided by a list of topics (see Appendix 3). I knew that some issues might be uncomfortable for participants to discuss as it pertains to their current workplace. I sought to avoid pressing participants by allowing them to steer the conversation into more contentious areas (Bernard, 2006:215). As I gained experience, the interviews became richer and led to interesting detours (Bernard, 2006:212).33 All the interviews were conducted in English, which is a second language for both the researcher and participants.34 I transcribed significant parts and typed out the rest summarily. Minor grammatical mistakes and redundant repetitions and words have been corrected in direct quotes.

I conducted informal interviews with passengers on the train and at Hyllie, asking about their thoughts and experiences with border control.35 Additionally, I searched major Swedish media platforms, such as Sydsvenskan, electronically for relevant articles by using the keyword ‘gränskontroll’ [border control]. Official websites of Sweden’s government, parliament, and police were used to find specific policies and statements on border control, which help understand government reasoning (e.g. Regeringen, 2017; Polisen, 2017a).

I passed through the border control 25 times between March 6 and May 15. I kept notes of dates, times, departure and arrival station, and passenger and guard behaviour during ID checks. I logged 14 hours of observations at Hyllie station. During these, I drew

33 Two of these strands are picked up in the concluding remarks (Ch. 8) as suggestions for further research. 34 Sometimes participants resorted to Swedish phrases, which I, as a Danish speaker, understand well. 35 Casual conversations with people who asked me for directions and help at Hyllie became an

unexpected source of data. This happened surprisingly often and sparked interesting conversations about border control, Swedish policies, and even the war in Syria. One reason might be that I am a young, ’non-threatening’ woman. Another reason might be that I appeared comfortable and familiar with the setting, and not at all busy when I was observing. This perfectly illustrates the benefits of allowing for open-endedness and serendipitous moments in ethnographic research (Povrzanović Frykman, 2004:98).

sketches, took photos, and meticulously took notes of everything I found slightly relevant, including reflections on weather, architecture, sounds and feelings. Even though I never attempted to ‘hide’ that I was observing, I sought to blend in to avoid causing changes in behaviour. Field research allowed me to observe how encounters between border guards and passengers (including myself) unfold and what it feels like to physically stand at Hyllie. As Cohen puts it, I was “using myself to study others” (in Povrzanović Frykman, 2004:84)

The use of multiple sources of data allowed a form of triangulation; the use of different measures of the same ‘variable’ (Chambliss & Schutt, 2010:87). To give an example: In April, I noticed a group of big bags of gravel at Hyllie. I asked participants about this, and was told that it was for a new fence. I then searched for articles on the subject and found an article in Sydsvenskan (2018a) discussing the increasing permanence of border control. I also ‘found out’ about the border shut-downs during observations, prompting discussion of this with participants.

5.2.2 Selection of participants

I contacted the Swedish Police, Region South in February, 2018. I got in touch with the Deputy Head of Division who sent out an email to police officers with experience of working at the border control at various times between 2015 and today. In his words, he tried to contact as large a group as possible with a broad experiential distribution. Subsequently, I received a list of willing interview participants. In this way, the Deputy Head became my ‘gatekeeper’ (Creswell, 2007:125). I ended up with eight interview participants who have worked at the border control at various times between 2015 and today. Since I had indirect access to the police and border guards, I did not select anyone based on age, gender, position, or experience – I simply took every participant I could get. This could mean that participants were pre-selected by the gatekeeper because they were especially uncritical of border control. However, I did not sense any such predisposition during the interviews.

5.2.3 Presentation of participants

I interviewed five police officers and three civilian border guards. Seven of them still work with the police or border control, which is why I present participants in general

terms, instead of describing each participant individually. The police group comprised three inspectors, one assistant and one group chief [gruppchef], all male. Ages ranged from late-twenties to early sixties. The group is not representative in relation to gender36. The study does not strive for representativity, but it would have been interesting to engage a female perspective. The study’s only female participant explained that some border crossers treat female guards with less ‘respect’ than their male colleagues. The gender distribution of the participants hindered me from pursuing this thread. The civilian group comprised two passport controllers and one border controller, all in their early 20s and 30s, one of them female.

All interviews lasted about an hour37 and ensued in a friendly, conversational manner. I generally felt that the participants were open with me although I did sense a slight apprehension at times. I sensed this in the occasional reluctance to go into detail, or when participants stressed that although they ‘represent the police’ these were their ‘personal opinions’.38 It is important for me to acknowledge that I do not think that it is an easy task to be entrusted with border security. Every single participant came across as a dedicated, caring professional, who performs a challenging job to the best of their abilities.

5.3 Ethical Considerations

The interview participants do not represent a particularly vulnerable or minority group, but most of them still work with border control. Consequently, the interviews necessitated serious ethical reflections. I inquired about the challenges and structural issues involved with their work, personal experiences and grievances and their opinions on politically contentious issues such as free movement and immigration. The situation placed me in a precarious position, which led me to remove any possible identifiers such as names, job title, and even dates. A researcher’s primary responsibility – besides conducting sound research – is to protect a study’s participants (Bernard, 2006:26) and I have done this to the best of my ability. Every participant signed an interview consent form (see Appendix

36 Official statistics report that about a third of the Swedish police force is female (SCB, 2018:20). 37 The shortest interview lasted 45 minutes and the longest lasted 1 hour 42 minutes.

5) and were granted two weeks to withdraw permission. I chose not to include dates for observations that could identify any single guard. Another main concern of mine was whether I would misrepresent the words of the participants. To avoid this to the largest extent possible, I present most of the data through direct quotes; allowing participants to speak before me.

5.4 Positioning Myself

Creswell (2009:267) writes that it is important to reflect on personal biases and values in qualitative research, where the researcher is the primary instrument of data collection and interpretation. Quoting Foucault, I acknowledge that undertaking this study “has been on the basis of my own experience” (in Simons, 1996:8). As Povrzanović Frykman writes, (ethnographic) research “is personal” (2004:98). My choice of topic is motivated by my own experiences with border crossings and, frankly, a certain personal scepticism towards border security. I have attempted to reflect critically on, and continuously question my own ‘agenda’ throughout the process. Finally, I wish to acknowledge that I write from a privileged position as a Danish citizen. My position has inescapably shaped my border crossing experiences and the encounters with interview participants.

6 DATA

This chapter introduces the data divided into four themes based on the framework of biopolitics-as-firewall. It is stripped of any identifiers; participants are simply assigned a letter – P for police, B for civilians – and a number. Some quotes are completely anonymised. I wish to clarify that this study does not evaluate the performance of the border control or border guards.

6.1 Research Site

Coming by train from Denmark, Hyllie is the first Swedish stop. Hyllie is an underground railway station with two platforms and four tracks (fig. 3, fig. 4). Trains from Copenhagen, which arrive on Track 4, are subject to border control. Guards rest and conduct second-line checks in a container (or “shed”) inside the ‘control area’ (fig. 5). In May, a solid fence (fig. 6) replaced the previous fence between Track 3 and 4 (fig. 7). During my observations at Hyllie, I noted that the mood varies considerably depending on the time and day of the week; during week day rush hour, the narrow opening in the fence turns into a chaotic bottle neck with passengers pushing to get out. Other days, mostly on weekends, time seems to stand still. When the weather is mild and sunny, passengers and border guards lounge in the sun, chatting and joking. When it is cold, as it was in March when I began this field research, they silently conglomerate inside shelters (Field notes, March-May, 2018).

Figure 4: Train tracks, Hyllie. (Photo by author, Apr 21, 2018).

6.2 Rules

Currently, 74 police officers and 161 civilian border guards work at the border controls at Hyllie, Lernacken and Helsingborg, managed by the Swedish Police in Region South39 (Interview, P5; Sydsvenskan, 2018a). Most police are commanded to the border for three to nine months, often far from home:

B3: The problem is that the police don't wanna work there (…) It's not really a police job. I mean, the police are educated for something else.

P2: Uhm, when I first heard of it, I thought and heard that it was a crappy place to work, but… afterwards I think it’s an okay job. Just a job, that’s it.

The training lasts 2,5 weeks for civilian passport controllers and nine weeks for civilian border controllers40. They learn about EU, Schengen and Swedish laws41, documents and “general guidelines when it comes to police work” (Interviews, B1, B2, B3). Police officers undergo a two-day “crash course” followed by a learning period (Interview, P2).

The multiple layers of rules of border security complicate the work:

P2: The hardest [cases] are the ones that came from third countries with documents that are basically easy to fake - they look like they're fake but they're real. Sometimes we get people that they're originally from Syria, they got an alien's passport42 from Malta and a residence card from another European country. They're the hardest ones because it's so many rules that apply so that's the most difficult thing to investigate and to do check-ups on. We can call the other countries and send them the documents; we do it with SIS, Schengen Information System.

39 Region South [Region Syd] includes Blekinge, Kalmar, Kronobergs and Skåne County. The region is

divided into five police areas: Malmö, northwestern Skåne, southweatern Götaland, southeastern Götaland and southern Skåne.

40 Border controllers receive more in-depth knowledge about laws and documents than passport controllers

and are allowed to work with border control in airports as well.

41 Primarily the Swedish Alien’s Act [Utlänningslagen] and Passport Act [Passlagen].

42 The Swedish Migration Agency’s website states that “[i]f you do not have a passport and do not have the

possibility of obtaining one, in some cases the Swedish Migration Agency can issue an alien's passport.” It applies to people “who have been granted a residence permit in Sweden on the grounds of protection from authorities in their home country and who can therefore not contact them to obtain a passport.” Holders of an alien’s passport can travel according to EU passport requirements, sometimes requiring a visa as well (Migrationsverket, May 11 2017).

Civilians and officers generally perform the same tasks. They wear similar blue uniforms and green vests, lending them authority and “immediate visibility” (Chalfin, 2007:1618). Still, their roles differ:

B1: It's just that they [police] have a different job. They have a different task than we have, different rights. Legally they have the right to physically stop someone or something like that. And they don't need much reason to do it (…) I would say that if our task is to investigate documents and check documents, their task is almost to protect us while we're doing that job.

Sometimes officers deal with criminal offences at the border, such as drug possession and traffic offences. Civilians do not have the right to use coercive means [tvångsmedel] such as arresting people or taking them into custody (ST, 2017). B1 explained that “according to the internal guidelines, two police officers should be the ones escorting the people back” [to the train to Copenhagen]. Another guard at Hyllie confided that “if it’s a 70-year-old grandma, we might do it even though it’s a grey zone”.

I asked every participant how much of their decision-making is based on rules and personal intuition. Participants emphasised that decisions are made “higher up” (P2).

B1: When it comes to these borderline situations, I mean, you still have to understand that personally, as border guards, we're not the ones making the decision itself. Because - maybe you've heard that we have to talk to decision-makers and they're the ones who have the legal knowledge (…) Basically it's better to call than to not call them. Every decision that's done, it's through them. So even if it's something as simple as you forgot your passport, you should go back, I know that they will be sent back. I still have to call a decision-maker.

Yet, guards do use their discretion and intuition during ID checks:

P5: I think the most important work is speaking to the person, having that human contact… We could use more computers, of course, and have iris scans and face detection and all that, but for us, that's the future. We don't get those resources. And I mean, not even our airports have those. Lots of the work here is done by asking the person, 'what are you doing here, how long are you staying, where do you live back home, who are you visiting in Sweden?', those questions. And having the experience and the ability to read between the lines and determine whether this person is telling me the truth now, or is he just pulling my leg, trying to get into Sweden illegally.

B1: The airport obviously has all these scanners. But we on the outside border control, like physical borders, the only tool as such that we have is really the passport scanner that lets us scan the passport and then compares it to the Schengen international system. Actually that's the only control tool we have (…) Our task is looking for people. And legit documents. We don't need no scanners to do that. We just need to make sure that the passport is valid and that the person standing in front of us is actually this person.

These statements dovetail Bigo’s finding that “among border guards, the ability to detect ‘illegals’ comes from the long experience of control that only practice can give” (2014:214).

6.3 Categorisation

Based on the rules, border guards check IDs and assess who is allowed to enter Sweden. Six ‘categories’ of people emerged in the interviews: (EU/Nordic/Swedish) citizens; ‘real’ asylum seekers; ‘bad’ asylum seekers; potential criminals; illegal workers; and tourists. The data largely confirms Bigo’s findings that attitudes vary from “aggressive” behaviour towards “‘bogus’ refugees” who steal the places of “‘genuine’ refugees” and implicit reinforcements of racism to “more comprehensive and ‘compassionate’ attitudes based on the recognition that migrants seek to escape difficult life conditions” (2014:215). Participants spoke movingly about encounters with ‘real’ asylum seekers:

P5: I can tell you about my strongest moment within the border control. (…) as I told you, I was sent to Hyllie station and Lernacken back in 2015 before I was a group manager. I was sent there just one or two days after the border control was introduced. So there were trains coming, I think, every 20 minutes with 3-400 persons just coming out from the trains, applying for asylum, and some didn't want to apply for asylum. (…) And one man, who was old enough to be my dad, from Syria, I stood there talking to him and he spoke English and he told me that, ‘I mean, I've been coming all the way from Syria, escaping the war, and my goal is to go to Norway because that's where my family is.' And I spoke to him and I told him that you need to apply for asylum in Sweden, we have border control here, you cannot be let into Sweden. You need to apply for asylum here and then you can tell the Migration Agency that your family is in Norway (…) But you need to apply for asylum in Sweden or go back to Denmark’. And it was such a... strong moment, my strongest moment, because he was standing there, as I said old enough to be my

dad, crying in front of me. And he knowing, and I knowing, if he just was one or two days earlier, he'd be in Norway by this time. So that's [a] hard, uhm, line between the job I'm doing and what I believe in, that this is right and this needs to be done, in reference to this man standing here and he's just two days late.43

‘Bad’ asylum seekers and criminals are perceived quite differently:

P4: We shouldn’t really help everybody because some of them are not here for legal reasons, they’re here to take advantage of the Swedish society and make a mess and do criminal things (…) I have a really tough time to handle that when they arrive here and just have like ‘We want, give me, give me, we want!’ And I see other small children from like Syria or Afghanistan, they’re really happy to come here and they feel safe here, but with Morocco it’s like ‘Can I smoke, where’s the food, where’s the train to Stockholm’ (…) I don’t find them like ‘true’ asylum seekers, but I gladly help sad children and sad people that I really can feel I make a difference.

Illegal workers are seen as being vulnerable to social dumping but also as threats to “fair competition” (Interview, B3). Tourists (mostly North American) were discussed as ‘accidentally’ being trapped by the control when they fail to bring passports even though “they’re no risk for the nation because I can obviously see that they are tourists” (Interview, P4).

The ID requirements sometimes create confusion for passengers and challenges for guards:

B2: Most of the time people listen, but sometimes we get the same ones without ID, day after day with the same card. I don't know what to say to such a person. Often when that happens, they have more respect for a police officer and they tell them: 'Next time you do something like this, we can keep you for six hours'. Because it's the rules, if we have to investigate something we have the right to keep a person for 6 hours. Of course, we don't do that if we don't have to, because we don't have time for that.

43 I noticed an interesting pattern in relation to my handling of the interview material. During the interviews,

I focused on listening, asking questions, and taking notes. It was not until I started processing the words through transcribing them that the full emotional impact washed over me. This story moved me to tears, but not until I wrote it down. This personal reflection suggests that the very act of transcribing interviews might be more than tedious manual work; it serves as an important step in the process of analysing and interpreting the material.