Repeating Despite Repulsion: The Freudian

Uncanny in Psychological Horror Games

Julia Jespersdotter Högman

English Studies Bachelor Level 15 hp

Term 6 2021

Table of Contents

Abstract………...i

1. Introduction………....…..1

2. Theory and Method………..….4

a. The Uncanny………..4 b. Player/Avatar Relationship………...8 c. Interactive Fictions………..10 d. Cry of Fear………...11 e. Silent Hill 2………..11 f. P.T………12 g. Outlast……….…13 4. Discussion……….14

a. Internal and External Reality………...14

b. The Symbolic………...21

c. The Familiar……….31

d. The Double………..37

e. Video Game Fiction and Written Fiction………...41

5. Conclusion………....44

6. Glossary………....46

Abstract

This thesis explores the diverse and intricate ways the psychological horror game genre can characterise a narrative by blurring the boundaries of reality and imagination in favour of storytelling. By utilising the Freudian uncanny, four video game fictions are dissected and analysed to perceive whether horror needs a narrative to be engaging and pleasurable. A discussion will also be made if video game fictions should be considered in the literary field or its own, and how it compares to written fiction in terms of interactivity, engagement, and immersion.

1.

Introduction

I began my research with the purpose of defining the strange allure to horror games, the enjoyment in torturing yourself with graphically bloodied deaths and grotesque monsters designed to terrify you, and why we subject ourselves to this terror. There is an element to horror games that adventure games seem to lack, namely the adrenaline-filled rush of conquering the reaper, facing the worst, and emerging on the other side. The rectangular shape of the computer screen dissipates, bridging the gap between player and avatar, you become fully immersed in the goal to survive the horrors before you. Jeffrey Douglas writes: “There exists a sense of pleasure conflated with emulating the mastery of an unpleasurable experience, and the sense of pleasure generated by symbolically engaging death is predicated on the intuitive sense of despair one might feel in facing finality” (4). Douglas refers to the Freudian death drive, the compulsion to repeat despite repulsion and the enjoyment you achieve from this cycle. While researching this compulsive desire, the Freudian death drive was a theory that surfaced numerous times. Still, even more prevalent was the Freudian uncanny, describing the unsettling but pleasurable horror in doubting whether something is real or rooted in imagination (Brown and Marklund 4). This theory has been applied to horror games previously, specifically related to the video game franchise Silent Hills. Psychological horror games are usually analysed in psychoanalytic theory due to their focus on the protagonist’s mental turmoil. Anna Maria Kalinowski discusses in her article how game developers utilise familiar environments “which players can easily identify, but then alter them in ways to create a feeling of something being ‘slightly off’” (4). This sense of unsettling the player through uncanny elements is the focus of my research, specifically how utilising the uncanny affects the video game’s narrative. Interactivity, agency and relation between player and avatar are also interesting aspects of this subject. Are video game fictions—games with a fictional plot—a more interactive form of storytelling than text-based fiction due to the agency the player has? How does the player/avatar

relationship compare to the reader/narrator relationship? Should video game fictions be considered in literary theory or be a separate field? While this text will not answer all the above questions, it strives to offer a perspective on the relation between video game fiction and written fiction through the lens of the psychological horror genre. Psychological horror is a sub-genre separated from its predecessor of pure horror due to the intricate narrative elements stressing a singular protagonist’s psychological journey. Prioritising the narrative over terrifying its audience, psychological horror aims to unsettle rather than rely on sudden frights. In psychological horror games, the player must interpret occurrences and form individual conclusions, at times questioning what is real and what originates from within the protagonist’s imagination.

Jonathan Ostenson argues for video games to be considered in literary theory, he writes: “the games of today have come to rely more and more on the elements of fiction in their design, and they represent unexplored territory in studying the nature and impact of narrative” (2). Conversely, Tanya Krzywinska, professor in digital games, transmedia, and immersion, argues for the existence of ‘ludology’, game studies. As it strives to define the relationship between player and avatar, ludology aims to separate itself from literary theory due to the difference in medium and audio-visual rather than textual storytelling (Roe and Mitchell 2). Krzywinska writes: “I for one look forward to a time when I don’t have to smuggle games into my film courses under the rubric of genre” (2). Although I agree with Krzywinska’s perspective on studying games separately, it will still be practical to consider them in the context of written media, if only to prove their worth as a field of research. This thesis will take advantage of Sigmund Freud’s text The Uncanny to achieve this, exploring the psychological horror narrative and its effective and affective storytelling using narrative techniques derived from literary theory and traditional storytelling.

The games I will research in this thesis are staples of the psychological horror genre,

Silent Hill 2 being a game that kickstarted this type of storytelling in 2001, adding

psychological elements to its successful predecessor with the same name. P.T., meaning “Playable Teaser,” was an interactive teaser for the highly anticipated latest instalment in the

Silent Hill franchise designed by game producer Hideo Kojima and film director Guillermo del

Toro. However, the game was cancelled due to conflicting interests with Konami, the company owning the rights to the franchise. Outlast and Cry of Fear are games referred to as “indie horror,” meaning smaller, independent teams created them without the financial support of a corporate game publisher.

As mentioned earlier, the Freudian uncanny is closely related to psychological horror, derived from Sigmund Freud’s book The Uncanny. The book discusses concepts that incite fear and uncertainty while also emphasising the separation of imagination and reality, the unfamiliar and the familiar. Horror in video games has previously been discussed in the context of Sigmund Freud’s The Uncanny in attempts to locate what makes us fear what we logically know does not exist. This thesis will further explore the concepts presented in Freud’s work concerning how the perception of reality is portrayed through the protagonist’s perspective, causing the player themselves to be lost in the inexplicable. I will also consider the views of Slavoj Žižek and Ewan Kirkland as they have contextualised and modernised the Freudian uncanny in film and games, while Freud is limited to literary examples. By utilising these theories, I will gauge what is rewarding and pleasurable in these video game fictions. How can I define the player/avatar relationship further? What effect do the uncanny elements in the games have on the player’s connection to the avatar they are controlling? What is the psychological component of psychological horror, and how does it relate to the Freudian uncanny? And finally, is video game fictions comparable to written text? Is one more interactive than the other?

2.

Theory and Method

a.

The Uncanny

The Uncanny is a strange phenomenon that has been the root of research both within video game theory and psychological horror as researchers attempt to navigate what incites this peculiar feeling of discomfort. I will begin in the scope of study that resides outside of video game narratives; Sigmund Freud and Slavoj Žižek are worth mentioning in this context, while Ewan Kirkland’s focus is on horror games.

According to Freud, the uncanny “is undoubtedly related to what is frightening—to what arouses dread and horror” (1). He introduces the word as derived from the German word 'unheimlich,' meaning the opposite of 'heimlich,' homely, or 'heimisch,' native (3). Freud intends to present a common conclusion that what is uncanny must also be unfamiliar or that something must “be added to what is novel and unfamiliar in order to make it uncanny” (3). He then states that this is a shallow interpretation of the uncanny, originating from Ernst Jentsch, from which he concludes that: “It is not difficult to see that this definition is incomplete, and we will therefore try to proceed beyond the equation ‘uncanny’ as ‘unfamiliar’” (4). Freud proceeds to investigate the meaning of the uncanny in several other languages, resulting in more definitions such as “strange, foreign” (Greek), “uncomfortable, uneasy, gloomy, dismal” (English), “daemonic, gruesome” (Arabic, Hebrew) (4, 5). He then returns to German, especially emphasising a statement by Friedrich von Schelling: “Unheimlich is the name for everything that ought to have remained … secret and hidden but has come to light” (6). With this, Sigmund Freud concludes his interpretation of the unheimlich or uncanny; “It may be true that the uncanny [unheimlich] is something which is secretly familiar [heimlich-heimisch], which has undergone repression and then returned from it, and that everything that is uncanny fulfils this condition” (16). Freud explains the uncanny as the dichotomy between the familiar and the

unfamiliar, altering what feels familiar through the resurfacing of repressed elements. Researchers of Freud’s uncanny have adapted his theories to more modern mediums, such as Brown and Marklund’s study of the uncanny horror in the video game Animal Crossing: New

Leaf. They reiterate Freud’s definition to state: “It is the seemingly oxymoronic combination

of allure and repulsion, and strange and familiar, which gives the uncanny its unnerving nature” (4). By claiming that Freud’s uncanny also includes pleasure, “repetition despite repulsion,” they offer a different perspective of his uncanny, one that can be applied to psychological horror games, as you must die to progress, and you will enjoy it (Brown and Marklund 4). While there is more to this pleasurable repetition, deriving from his theory on the “death drive,” I will first introduce some other perspectives of the uncanny.

In Looking Awry: An Introduction to Jacques Lacan through Popular Culture, Slavoj Žižek analyses narratives written by film director Alfred Hitchcock through the lens of Freud’s uncanny:

All of a sudden he notices that one of the mills rotates against the direction of the wind. Here we have the effect of what Lacan calls the point de capiton (the quilting point) in its purest: a perfectly “natural” and “familiar” situation is denatured, becomes “uncanny,” loaded with horror and threatening possibilities, as soon as we add to it a small supplementary feature, a detail that “does not belong,” that sticks out, is “out of place,” does not make any sense within the frame of the idyllic scene. (55)

Žižek establishes the uncanny as an unfamiliar aspect in a familiar setting, referred to as the architectural uncanny in Ewan Kirkland’s research (1). Žižek continues: “The same events that, till then, have been perceived as perfectly ordinary acquire an air of strangeness” (55). Žižek’s understanding of the uncanny highlights its contemporary uses, while Freud was limited to literary examples in his book. In contrast, Žižek’s explanation of the uncanny draws imagery from film narratives and is, therefore, worth considering in the context of video games.

architectural uncanny related to game mechanics. In his paper Horror Video Games and the

Uncanny, he considers the possibility of the avatar as an uncanny inanimate object turned

animate. This consideration exists within Freud’s uncanny, citing Jentsch’s ideas on objects that take a life of their own: “Jentsch has taken a very good instance ‘doubts whether an apparently animate being is really alive; or conversely, whether a lifeless object might not be in fact animate’” (8). Kirkland applies this idea to the avatar, claiming as they are three-dimensional figures designed to be true to life, but despite this, “there remains something unavoidably lifeless about the avatar” (1). He refers to them as “virtual puppets” and that they “function as a surrogate for the player within the virtual world of the video game” (1). Continuing in the same scope of discussion, Kirkland applies ‘the double’ to the player/avatar relationship, another concept derivative from the uncanny. The notion of the double can apply to various scenarios; Freud defines it as “doubling, dividing and interchanging of the self” (9). Freud’s conviction refers to the double as the presence of doppelgängers, which at times may divide knowledge between them through a telepathic relationship, or that an individual “identifies himself with someone else, so that he is in doubt as to which his self is, or substitutes the extraneous self for his own” (9). Kirkland contextualises the double, precisely that which regards the interchanging of the self, with the player/avatar relationship (2). He argues for the double being present in the endless cycle of destruction and resurrection in the gameplay, as the player controlling the avatar must at times send them into certain death to learn new information and progress in the game, a concept I explore further in my discussion.

The last set of examples of the uncanny Freud refers to as “omnipotence of thoughts” (24), dealing with repression of emotions: “something which is familiar and old-established in the mind and which has become alienated from it only through the process of repression (25). This reminds us of Freud’s consideration of the German dictionary and Schelling’s definition of how the uncanny can be defined as something repressed or hidden brought to light (7). This

manifestation of concealed elements will be covered further by discussing enemies and symbolism present in video games.

I conclude with the final example of the uncanny emotion most vital to this thesis: reality and its representation. Freud claims that the discomfort of the uncanny occurs when “the distinction between imagination and reality is effaced, as when something that we have hitherto regarded as imaginary appears before us in reality, or when a symbol takes over the full functions of the thing it symbolises, and so on” (29). Reality and imagination are vital parts of the psychological horror genre. The representations of reality in psychological horror games allow storytelling to evolve beyond what one may reasonably expect from more accurate to life or realistic narratives. Freud defines two models of reality, the psychical and the material (29). In more understandable terms, I will refer to them as internal and external reality in my discussion; internal reality is the psychological, at times imaginary aspects residing in the protagonist’s mind, external reality being the material setting and space in which the story takes place.

As you may now grasp, the uncanny can present itself in various scenarios, which Freud explores mainly in fiction. However, he concedes it to be more efficient in real life, as in fiction, the reader gives up their control of reality to the author, never questioning whether the text is rooted in reality or fantasy (34). The uncanny, therefore, is at its most effective when something seemingly incredible happens that awakens a question of whether such a thing is possible; reality and imagination are blurred to make sense of the feeling. Freud acknowledges the uncanny experience to be sparse and rare to occur, literature providing ample examples where real-life does not. Similarly, I will use video games to demonstrate how the uncanny may be inflicted to incite horror and doubt in the player or characterise a narrative effectively. As video game narratives consider both the player and the avatar, I must first define this relationship to include and apply it to my discussion.

b.

Player/Avatar Relationship

The player/avatar relationship is of specific importance to my research, as the player is an active participant in the video game’s narrative with the agency to command the avatar and influence the story. The theory I have found to be most associated with this relationship is the Lacanian psychoanalytic theory of the “mirror stage,” referring to the stage occurring when children “first encounter and respond to their own reflection as an aspect of themselves” (Rehak 2). The player/avatar relationship is reminiscent of this, the player responding and reacting to the avatar as an extension of themselves. We return to Freud’s notion of the double and substituting “the extraneous self for his own” (9), which has been argued to occur in this relationship. Jon Robson and Aaron Meskin explore this interaction between player and avatar, specifically how the player self-inserts themselves into the fiction:

The self-involving interactive nature of video games is best highlighted by focusing on the high degree of first-person discourse that is found in talk about our interactions with them. Gamers typically make a variety of first-person claims concerning the games they are playing (“I defeated the dragon,” “I was killed by the creeper,” and so on) and this is reflected in the use of the generic second-person in much video-game criticism. (4)

They argue that the player takes on a role in the fictional world based on the avatar they are playing, involving themselves in the narrative through its interactive nature. This is the core of the player/avatar relationship and the compelling aspect of video game narratives, specifically how to explain this changing of roles, as the player lets the avatar be “imbued with life,” consequently causing the player to “become more machine-like” in their stationary act of gaming (Kirkland 2).

To adequately define the relationship between player and avatar, we must look to new developments in narrative theory related explicitly to interactive fiction and games. Curie Roe and Alex Mitchell present the term “game narrator” in their article researching unreliable narrators in video game fictions (2). The “game narrator,” derived from cognitive narratology,

considers the player an active interpreter of the story separate from traditional narratology as it “understands narrative as an act of recounting while games involve direct participants in the events as they take place” (2). Video game fictions can be participated in as though it is a real-time event—if the player chooses to play—but simply stating that written text is limited to recounting is inaccurate and deserving of criticism. However, they divert from written fiction and suggests comparing the game narrator to film rather than written media, as they argue “computer games’ representation of space and narrative is audiovisual instead of textual” (2), which is, like film, using both visual and auditory channels. While I can agree that the medium of video games is in large part audio-visual, I would also argue that there are textual aspects more resemblant to written fiction. Tanya Krzywinska shares my sentiment as she founds her video game research on the “player/text relationship,” explicitly arguing for the textual aspects and how it relates to the player:

Any game has a set of ‘textual’ features and devices: a game is a formal construct that provides the environmental, stylistic, generic, structural, and semiotic context for play. Images, audio, formal structures, the balance of play, the capabilities of in-game objects and characters are all features that operate ‘textually’. The concerted action of a game’s textual strategies facilitate, at least in part, the generation of emotional, physical, and cognitive engagement, shaping the player’s experience of game play and making it meaningful. (3)

Deriving a video game fiction of its textual features would also mean removing the fictional elements that engage the player in the story. However, while there are textual aspects to video game fictions, I still believe the medium close to film due to its audiovisual channels separating it from written fiction. Therefore, I will employ the term ‘game narrator’ due to its similarity with the film narrator with the added interactive mode; the player can enter the fictional world and impact its story. In this text, I will be referring to the player as the game narrator, describing the player simultaneously experiencing the story while also actively participating in its events and controlling the avatar, the protagonist.

c.

Interactive Fictions

Storytelling is growing and expanding with the inventions of new mediums. There are now several new ways to tell a story, such as ARG’s (Artificial Reality Games), interactive fictions, transmedia fictions, and video game fictions. Fiction can be told using any platform and is not limited to only written text. Video game fiction differs from written fiction due to the amount of agency the player can have, their actions dictating the storytelling and, in some cases, how it ends. As previously discussed regarding the game narrator, while I believe video games should be considered a research field of its own, it is unavoidably compared to written text, often emphasising the difference in the interactivity of the two mediums. Aaron Meskin and Jon Robson argue that written text is a non-interactive media, claiming consumers of these have “virtually no influence over the structural properties of those fictions,” conversely, video game consumers will “influence what is true in the fiction, and, hence, play a role in generating its display “(4, 5). While written fiction does not allow the reader to change its structure directly, there are interactive options for the reader, as each reader can contribute subjective aspects to each written text.

I will clarify that not all video games are video game fictions; so-called FPS games (first-person shooters) may be more inclined to push you towards capturing objectives such as defeating an unnamed enemy or protecting an area for a specific amount of time. Games such as massively multiplayer games more focused on teamwork and winning matches are not considered video game fictions as there is no real narrative being presented or told by participating in them. The only objective present is to beat the other team, and these games tend to be unlimited in how much content you can play, the main goal being to improve your skill in the game and be rewarded with victory.

Conversely, video game fictions host a limited amount of content. Timothy Garrand explains it as “there is nothing unplanned in an interactive narrative. If one plays the program

long enough, one will eventually see all the material the writer created. An interactive narrative essentially allows each game narrator to discover the story in a different way” (3). I find this to be the most intriguing aspect of interactive video game fiction, namely, having the agency to follow a different path than the player before you. However, Garrand is accurate that the flaw in video game fiction is its limited writing, the enjoyment usually ceasing after the initial playthrough. Nonetheless, I argue that similarly to how readers discover new things each time they return to their favourite novel, players also go back to enjoy what makes each game unique; music, characters, visuals, or story—no matter how predictable it has become.

d.

Cry of Fear

Cry of Fear is a small game made by only four people, initially a modification for Half-Life 1. The game narrator controls Simon, who has lost his memories and finds himself in the

deserted town of Stockholm. He must navigate through the city while fighting terrifying creatures until he slowly regains his memories. At first glance, the game plays similarly to survival horror, the psychological elements becoming more prevalent as the plot unravels. The game mechanics are utilised in exciting ways; for example, Simon has limited stamina, represented by a bar draining as you run away from enemies; if empty, it almost certainly leads to death. Implemented dodge mechanics also drains your stamina bar; simply withstanding damage from enemies is impossible; therefore, dodging is essential if used sparingly. The game narrator is limited to Simon’s phone screen as an unreliable light source, especially when the battery runs out in an especially horrifying part of the game.

e.

Silent Hill 2

Silent Hill 2 is the sequel of the widely successful first Silent Hill game; with a bigger

series, Silent Hill 2 being more focused on the psychological aspects, and it exceeded expectations. Anna Maria Kalinowski’s article discussing the Silent Hill franchise states that it has been “recognised as a psychological horror masterpiece in the eyes of many players due to its careful implementation of psychological concepts within a simultaneously complex and well-crafted horror narrative” (3). Silent Hill 2 is argued to have been the game to kickstart psychological horror in the video game medium due to its success.

The game revolves around James, having received a letter from his wife Mary, calling him back to Silent Hill, a place where they previously vacationed; he returns despite knowing she is long dead. The tale of Silent Hill is developed upon in each instalment in the series, the main plot point being that everyone called to the town witnesses it differently, their own suppressed emotions and problems manifesting physically to haunt them. James is not alone on his journey. There are other people in the town, seemingly going through the same hell as James. It seems the town’s purpose is to confront those with suppressed issues and thoughts by reincarnating them into physical beings and manipulating the town’s surroundings to demonstrate the inner turmoil of the characters. James is on a journey in Silent Hill, both to survive the hell he is in and confronting the guilt he has repressed for smothering his sick wife out of frustration with her condition.

f.

PT

PT, meaning Playable Teaser, was an interactive teaser of a highly anticipated new Silent

Hill game, made by award-winning game developer Hideo Kojima, founder of Kojima

Productions, and film director Guillermo Del Toro. The game was cancelled due to conflicts with the publisher, Konami, who owns the rights to the Silent Hill franchise. Following this, Konami pulled the game from the PlayStation Store, and now only those that still have it installed on their PlayStation may play it. Despite only being a teaser, the game was critically

acclaimed for its atmosphere, story, and visuals. Kalinowski’s analysis of the game in her article “Silent Halls” describes the game becoming popular when it “began to garner attention amongst online communities and ‘Let’s Play’ videos, as word circulated of the game being a genuinely terrifying experience” (2). The game plays in the first person, instead of the normal third-person perspective in previous Silent Hill games. You begin in an L-shaped hallway, seemingly stuck in a loop in a suburban house, as you can only walk down the hallway to a door that brings you back to the beginning of the hallway. There seems to be a murder mystery present, the radio in the hallway reports on a familicide case committed by the father and two more cases like it. To progress, you must investigate frightening events and solve puzzles. As you move through each loop, the surroundings in the hallway gradually start to change. You eventually encounter a hostile ghost named Lisa, appearing and disappearing seemingly at random, shaping a uniquely horrifying experience. When solving the final puzzle, you escape the house, ending in a cinematic clip that reveals an upcoming Silent Hill game named Silent

Hills.

g.

Outlast

The Outlast games are newer and more focused on surviving terror; with chilling atmospheres and highly detailed graphics, you are transported to a realistic environment that punishes you for being too brave. The first Outlast game was unique to the genre as you are told not to fight the enemies but run away and hide at first sight of one, differing from Silent

Hill and Cry of Fear, where weapons are encouraged and often required to use. The camcorder

is essential in both games; in the first one, you play as a reporter out to get a scoop on Mount Asylum, while in the second, you play as a cameraman travelling with your wife to report on a story. The camcorder in the first game allowed you to use night-vision to see in the dark and contributed to the plotline being a reporter filming everything you can find while there. Having

developed this feature since the first Outlast, if you film anything significant in the second game, the video is saved, and you can view it on your camcorder as an in-game action. The protagonist will narrate over each filmed clip, letting you understand what the protagonist is thinking and feeling in those moments of the plot. This thesis will concern itself with the second game because of this mechanic, as the video snippets providing insight on the protagonist’s thought process is the central psychological aspect in the game and lets you peer into the protagonist’s mind.

3.

Discussion

a.

Internal and External Reality

Before beginning this discussion, I must recall the representations of reality Freud presents in his book, namely what he referred to as the “psychical” and the “material” realities, separating what is restricted to your mind and what is the physical world outside of it (29). Sigmund Freud states in The Uncanny that this uncomforting phenomenon lies in the boundary between reality and imagination and the seed of doubt that arises in whether something is possible in our external reality or if it resides in the internal. He further states that “the infantile element in this, which also dominates the minds of neurotics, is the over accentuation of psychical reality in comparison with material reality”; the imaginary reality is emphasised over the material one (29). As I stated previously, I will refer to these representations as internal and external realities; the internal being the psychological reality of the protagonist, the external referring to what is happening in the physical setting of the narrative. Navigating through the games in question, I will divide the narrative into the external plot and the internal plot to define the uncanniness of the game narrator being unsure of what is true in the narrative and what originates from the protagonist’s mind.

cameraman searching for his wife after their helicopter crashed in the middle of nowhere. Despite navigating the Arizona wilderness and the murderous inhabitants, much of the gameplay occurs in the protagonist’s hallucinations derived from his catholic school memories. Externally, Blake must survive the whims of the crazy inhabitants searching for his wife that somehow has become progressively more pregnant in a matter of days. The external plot exceeds common sense; although there are explanations for everything, they are vague and sometimes transcends logical reasoning. Instead, the internal story is the core of this video game fiction, the external plot scaring or unsettling the game narrator, while the internal plot provides an incentive to keep playing to unravel the story further. The external plot explains the madness in the inhabitants, as the entire area has been experimented on by Murkoff Corporation, attempting to achieve mind control and causing insanity. Heavily impacted by the flashes of light coming from the mind control stations, Blake is driven mad by hallucinations. The hallucinations repeatedly draw him back to catholic school, where the story unravels around his classmate Jessica and the guilt he harbours at failing to save her from being molested and killed by Father Loutermilch. It is implied that Loutermilch brutalised and beat Jessica to death, afterwards staging her suicide and Blake helping him out of fear of the consequences.

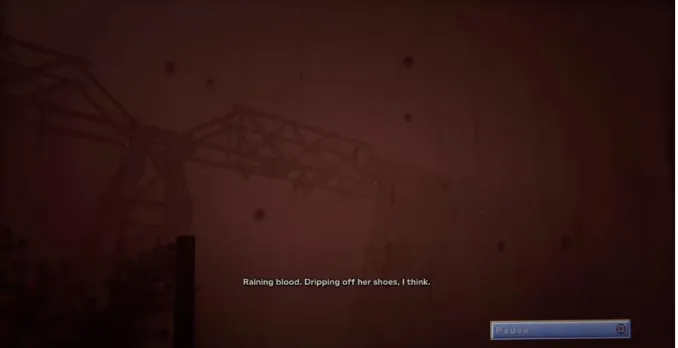

There are only a few times in the game where the hallucinations intrude into the external world of Arizona, one of them being a specifically disturbing sight of raining blood. When Blake films the rain, the game narrator may view the clip to hear him say: “Raining blood. Dripping off her shoes, I think. No. Just… I tried not to step in the blood because I didn’t want

to leave tracks.” (See fig. 1).

Despite being in Arizona, years later from the incident, Blake is unable to separate reality from imagination; you can assume he is talking about Jessica’s blood in this line. A similar blurring of imagination and reality occurs later in the game as well, when the main external antagonist, a character called Reverend Sullivan Knoth, the leader of the group Testament of the New Ezekiel, commits suicide. Blake films his body and, in the clip, says: “The priest dies. You didn’t have to do anything. You were a child, nobody could expect anything of you. None of this is my fault.” (See fig. 2). The hallucinations in these examples are not visible to the game narrator but hearing Blake’s words narrated over the clips saved in the camcorder you can interpret that he has lost the distinction between reality and imagination. He sees the reverends body and imagines it to be Father Loutermilch’s body instead, claiming he was too young to be blamed for Jessica’s death.

Cry of Fear is similarly rooted in the imaginary, as most of the plot is internal, although

it is not apparent to the game narrator until much later in the game. The game begins with a dialogue screen, Simon’s voice narrating: “I’ve always felt alone my whole life, for as long as I can remember. I don’t know if I like it… or if I’m just used to it, but I do know this; Being lonely does things to you, and feeling shit and bitter and angry all the time just… eats away at you.”

The game narrator plays as the protagonist Simon, claiming to have lost his memories and is now lost in Stockholm, so unlike its usual state, filled with monsters out to kill him. When the game narrator progresses, they begin to scratch the narrative’s surface, which is more profound than expected at the first playthrough. A survival shooter soon transforms into a story about depression, suicide, physical disability, and discontent with one’s life. At first glance, the external reality of this game is the events taking place in Stockholm city. As progress occurs and the game narrator is rewarded with short cinematic flashbacks after every defeated boss, the external reality is revealed to be a disabled Simon seated at his desk at home, writing down Fig. 2. Blake mistakes reverend Knoth for Father Loutermilch. Screenshot from Outlast 2.

his thoughts and feelings in a book (see fig. 3). The game’s plot revolves around a depressed Simon, wheelchair-bound and suicidal, writing to deal with his inner turmoil. The events in this book are the scope of the gameplay, the demons of external Simon’s mind trying to push internal Simon back from fighting his way out of depression.

At the end of the game—considering the game narrator made all the right choices until now—the external disabled Simon comes face to face with internal ‘Book Simon,’ the Simon that the game narrator has controlled for the extent of the playthrough. In a symbolic act of defeating his last enemy, himself, external Simon gets a second chance at life and treatment of his mental condition, given that the player made all the right choices, but that is another discussion.

P.T. is similar in some ways, but not being a fully completed game, there is less material

to analyse. The game narrator is closer to this game than the others, as it is played in first-person, and the protagonist being unnamed and not characterised, the player may insert themselves into the game. As previously mentioned, the plot takes place in an L-shaped

hallway, where the game narrator must interact with objects and solve puzzles to make progress. Despite this hallway appearing as usual as any suburban house, there seems to be a suspension of reality, or at least suspension of external reality, as walking through the L-shaped hallway will eventually lead back to the beginning, trapping the player in an impossible loop. The psychological elements are subtle, more so than the other games, as each loop through the hallway will slightly change its appearance, so slight the player can easily miss it. When the player starts doubting whether an object has been altered or stayed the same, discomfort only related to the uncanny occurs, the boundaries between reality and imagination effaced. There is not much to discuss in terms of story or plot in the game, as it was only a playable teaser hinting at a new instalment in the Silent Hill franchise, but knowing how previous Silent Hill games are, we can guess this too would have been present in the town of Silent Hill.

Silent Hill as a franchise has an extensive background history, especially related to the

location of the games. The town of Silent Hill perfectly encapsulates psychological horror, as each person visiting the town views it differently. The town can be perceived as the omnipotent antagonist holding up a mirror to each visitor’s face, perhaps as punishment for their evil thoughts or past mistakes. A lot is unknown about the town, the common knowledge being that there are alternate realities with alternating Silent Hills, each more different than the last, torturing its residents with monsters that take the symbolic shape of what resides within their minds. This reality is referred to as “dream-reality,” at times transforming to the so-called “Otherworld,” its nightmare-like state equivalent of REM sleep. The dream-reality of the towns entails that each visitor sees the town differently, suggesting they have been brought there for a reason. For the protagonist James, controlled by the game narrator, he must face his guilt of

killing his bedridden wife out of frustration with her condition (see fig 4).

Each enemy in the game represents this struggle, punishing him for his actions as he journeys through the town, a place he used to vacation in with his late wife. Due to Silent Hill being different for each visitor, it is impossible to determine as an outsider looking in what events took place in the external reality and what was internally restricted to only our protagonist. One hint on how Silent Hill operates are the different characters present in the game, each with a differing understanding of what is occurring in the town. Eddie claims that all he sees are people who mock and laugh at him, causing him to have a mental breakdown and attempt to murder James. Laura, the child in the town, does not see any monsters and run around freely, suggesting she, being a child, has a less sinister psyche than James. We can therefore not conclude that outside of the characters called to Silent Hill for a purpose, the town is not just a typical place with ordinary human people. The uncertainty that occurs in whether Fig. 4. Level design symbolising James' guilt. 23 May 2021,

the gameplay is set in the material reality of a town called Silent Hill or in the imagination of people like Eddie and the protagonist James is the centre of the unsettling emotion present in psychological horror.

These games adequately demonstrate how psychological horror can feature more than one representation of reality, often with more than one narrative layer. It is up to the game narrator to explore the boundaries of the plot and discover its full extent, sometimes having to draw conclusions based on vague factors such as the symbolism present in the enemies and events, as everything has a possibility of being connected to the protagonist and the internal reality of the game. As Freud previously stated in his studies on the uncanny, the uncanny arises when “the distinction between imagination and reality is effaced, as when something that we have hitherto regarded as imaginary appears before us in reality, or when a symbol takes over the full functions of the thing it symbolises, and so on” (29). Imagination and reality are central to the narratives of psychological horror games, but the symbolism is just as prevalent. As the abstract becomes physical, the internal demons of the protagonist manifested to take the shape of the thing they represent, and these are the enemies the game narrator must defeat to progress. Therefore, we must examine the enemies and antagonists in these games to discover whether they symbolise the protagonist’s inner struggle.

b.

The Symbolic

Symbolism is a central part of the uncanny, as it begs the question of what occurs when an object functions as what it symbolises (Freud 29). In psychological horror games, the horror lies not in the surroundings but between the protagonist and setting. Tanya Krzywinska argues that “horror games explore ways to play with, and against, game media’s normative expectations of mastery and its concomitant representational, symbolic, and emotional contours” (1). Horror games focus more on the portrayal of the main character’s emotions and

taking advantage of symbolism to offer perspective on the protagonist’s psychological struggles. Most commonly, this is done through the enemies, as horror games rely on the player’s fear of monsters and impossibly grotesque creatures. When discussing representation and affect in video games, Krzywinska claims that erasure of reality and otherworldly antagonists are additions of these concepts: “This sense is also exacerbated by the theme and narrative of the game which focuses on the loss of a controlling grasp on the nature of reality (nothing is what it seems) and the concomitant ‘reality’ of occulted forces” (3). The forces present in psychological horror games tend to take the symbolic form and functions of the thing they represent, often portraying abstract emotions such as repressed guilt, bringing us back to Freud’s statement on the uncanny being that which has previously been hidden or obscured but

comes to light (23).Through important boss fights, each unravelling the plot further, the game

narrator will encounter enemies that each represents a connection to the protagonist they control. Ewan Kirkland covers this topic in his analysis of a later instalment in the Silent Hill

franchise, referencing Freud’s uncanny and repression in connection with the enemies:

There are suggestions that the town of Silent Hill represents a beacon to particularly troubled individuals, for whom the landscape and the creatures within it assume a reflection of their own inner turmoil. The ways in which these repressed elements manifest as monsters in climactic boss battles suggests a therapeutic process whereby distressing memories take physical form, are confronted, and destroyed. The player participates in such processes, battling these inner demons on the protagonist’s behalf, vanquishing these manifestations of their guilt, trauma, and personal conflict. (4)

Kirkland analyses Silent Hill: Shattered Memories through psychoanalytic frameworks and this quote sums up the premise of the game franchise, specifically how the town of Silent Hill functions. The act of repressing emotions, hiding them, will eventually result in the revelation of said emotions; as Freud states, it comes to light, but it comes to light through the symbolic shape of confrontations from the manifestation of these emotions (Freud 29).

In Silent Hill 2, the game narrator controls protagonist James Sunderland, who enters the town searching for his wife, despite knowing he is the one that killed her. As game narrator, you are unaware of this fact, but the game seeks to send you hints through the enemies James encounter along his path and his aloof behaviour and speech that represents his confusion as to why he even returned to Silent Hill. The game designer and illustrator of Silent Hill 2, Masahiro Ito, has stated that “when working on designing creatures in Silent Hill 2, I really made them have their each [sic!] meaning of appearance on the true reason of James’s journey. Because they are something like illusions from his subconscious, not only creatures to take the score” (Masahiro Ito’s Twitter). Sexuality is a common theme in Silent Hill 2; as James’ wife was hospitalised for three years due to a debilitating illness, the player is to understand that she grew ugly due to her sickness, which impacted their sexual lives.

Consequently, many of the enemies in Silent Hill 2 are sexualised. For example, an enemy called the ‘Mannequin’ has an appearance that can be interpreted as sexual; a headless, armless monster, consisting of two pairs of legs stacked on top of each other with the top pair’s posterior made to resemble a woman’s breast (see fig. 5).

Fig. 5. First encounter with Mannequin. 23 May 2021. https://silenthill.fandom.com/wiki/Mannequin.

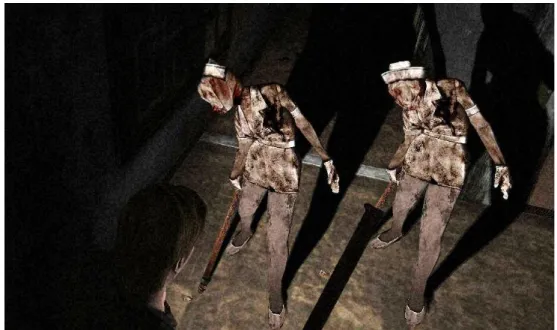

Another sexualised enemy is the iconic ‘Bubble Head Nurse’, a female humanoid creature dressed in a low-cut nurse uniform. The nurse’s head is covered and seemingly swollen under a liquid-trapped mask, the bottom centre of it taking the shape of an infant’s face (see fig. 6).

At first glance, these sexualised enemies are nothing but an obstacle the game narrator must face to progress. Learning the truth about James, his wife’s sickness, and his deep frustration with her state that he eventually smothers her with a pillow, puts their sexuality and

design into perspective.We can conclude that the Mannequin and Bubble Head Nurse are direct

representations of James’ harboured guilt for killing his wife, his sexual frustrations as she was ill and incapacitated, as well as the infant’s face representing their previous desire for a child. The covered and swollen faces of the nurses symbolise James’ act of smothering his wife to death, the nurse uniform hinting at the time he spent in the hospital with her before her death and reflecting his sexuality during this time.

Fig. 6. Encounter with two Bubble Head Nurses. 23 May 2021. https://silenthill.fandom.com/wiki/Bubble_Head_Nurse.

Another vital enemy to James’ journey, a recurring boss enemy named ‘Pyramid Head’, is a humanoid monster with a pyramid-shaped red helmet, dressed in butcher’s attire and wielding a heavy knife scraping against the floor. Pyramid Head resembles an executioner and acts as one, manifesting James’ guilt and desire for punishment; he exists solely to remind James of his past actions (see fig. 7).

When James kills another visitor of the town, Eddie, in self-defence, a second Pyramid Head materialises. Trailing the game narrator throughout the game, Pyramid Head does not eliminate but rather torture and confront James. By the end of the game, when James finally accepts his wife’s death and his actions, he faces Pyramid Head and his guilt with the statement: “I was weak… That’s why I needed you… Needed someone to punish me for my sins… But Fig. 7. First encounter with Pyramid Head. 23 May 2021.

that’s all over now. I know the truth. Now it’s time to end this”. Pyramid Head kills himself by the end of this battle as his purpose for existing has been finished (see fig.8).

Fig. 8. Last encounter with the Pyramid Heads. 23 May 2021. https://silenthill.fandom.com/wiki/Pyramid_Head.

Fig. 9. Mary in her boss battle form. 23 May 2021. https://silenthill.fandom.com/wiki/Mary_(boss).

As James confronts and faces his guilt, the final boss of Silent Hill 2 appears, Mary, his wife, or at least a manifestation of her, appearing as a diseased corpse strapped to a metal frame, upside-down and screaming. She wears clothing resembling what the Bubble Head Nurses wear, which references her hospitalisation (see fig. 9). She is just another symbolic manifestation of James’ guilt he must overcome in this final battle. One of her attacks is to strangle James, reminding the game narrator of how James himself asphyxiated the real Mary. Depending on the ending, the game narrator may read what the letter Mary gave James said, one of its lines being: “Whenever you come to see me, I can tell how hard it is on you… I don’t know if you hate me or pity me… Or maybe I just disgust you… I’m sorry about that.” Mary’s form represents this conflict James had with his wife, unsure if he still loved her and contemplating how he treated her during her final days. We know in this dream-reality of Silent Hill that it is not Mary we defeat, and James does too, saying this after defeating her: “That wasn’t Mary. Mary’s gone. That was just something I…,” not completing the sentence leaves the game narrator to interpret his statement freely. Theories vary from the monster being a hallucination that James imagined to a physical manifestation of his guilt created by the town of Silent Hill in its dream-reality, or it being Maria, a doppelganger of Mary serving as an antagonist in the game.

The symbolism present in Outlast 2 is frequently associated with religion. Both the external reality of the Arizona wilderness present antagonists affiliated with groups referred to as “The Heretics” and “Testament of the New Ezekiel,” as well as Blake’s internal hallucinations of catholic school. In Blake’s visions, the game narrator navigates Blake’s catholic school memories and repressed feelings of guilt regarding Jessica and her presumed suicide. It is implied that the music teacher at the catholic school, Father Loutermilch, raped and killed Jessica by pushing her down the stairs, then staging her suicide (see fig. 10).

Blake struggles with the guilt of not saving his friend, as he was there the night she was killed. In Blake’s memories towards the end of the game, you find out about Father Loutermilch’s actions, how he had brutalised Jessica, and it can be assumed then forced Blake to go along with the suicide coverup due to the line sung by the priest: “O be careful little mouth what you say, O be careful little mouth what you say…” while he is stalking Blake. This conflict is present within Blake throughout the game, being pulled into hallucinations by a long-twisted tongue belonging to the demon that chases you through the school corridors (see fig. 11).

Fig. 11. There are numerous demon chase sequences through the school. Screenshot from

Outlast 2.

Fig. 12. A comparison of Father Loutermilch and the demon. 23 May 2021. https://outlast.fandom.com/wiki/Loutermilch.

Even when he is in real, physical danger in the Arizona wilderness, he continuously returns to the catholic schools in his internal reality, stalked by a demon that shares the same birthmark as Father Loutermilch (see fig 12).

He presumably struggles with hallucinations due to his guilt for not speaking up and saving his friend from him. He discovers a phone ringing in one of the hallucinations that the game narrator can pick up to get this dialogue from a familiar voice: “Hello! Hello, oh thank God you’re alive. I need you to stay calm. We’re going to get help, we’ll get you out of there. I want you to find a place to hide, someplace safe where you can remember the taste of her kiss when you felt her neck break.”

The game narrator would recognise this voice as Blake himself, signalling the punishment he believes he deserves from standing by while Loutermilch kills Jessica and stages her suicide. In his hallucinations, the demon chasing Blake symbolises both Father Loutermilch and the helplessness Blake felt as a young boy, having to keep quiet in fear of Loutermilch’s actions. He deals with this guilt in a number of his recordings during his journey through Arizona, searching for his real wife, although he mistakes her for Jessica once he finds her:

“We’re out. I got Jessica out. It was cold but the snow had just started. We’ll find a grown-up and we’ll tell them what happened. We’ll be okay. It’s not my fault” (see fig. 13). Blake says this at the end of the game, with his wife Lynn in his arms; he is adamant that Jessica’s death was not his fault, as he repeats this in multiple recordings towards the end. These dialogue lines in Blake’s clip results in the game narrator doubting the reality of the narrative, as his hallucinations are intruding on the external plot but isolated to Blake’s perspective, creating a disconnect between player and avatar.

Concluding this point, I will remind you of Freud’s conviction of the uncanny occurring once a symbol functions as the thing it symbolises, or when what has previously been considered imaginary appears before us in our physical reality (15). The antagonists in these games can be interpreted as taking the form of the thing it symbolises by being an obstacle for the protagonist in the shape of something they have repressed in their minds, guilt being the common denominator in Outlast 2 and Silent Hill 2. Emotions can be viewed as imaginary, abstract phenomena, that when manifested, become something more tangible and concrete, therefore taking the full functions of the feeling they symbolise. As we are now aware, Silent

Hill 2 and Outlast 2 emphasises a dream-reality or hallucinations to project the protagonist’s

hidden emotions that “ought to have remained hidden but has come to light” (Freud 13). This repression of emotions is vital to the uncanny theory, as it is related to the dichotomy between the familiar and the unfamiliar, which I will discuss in the next chapter.

c.

The Familiar

As Freud mentioned, the uncanny originates from the German ‘unheimlich’, referring to discomfort or unfamiliarity. He then concedes that the uncanny is more prevalent in the moments where something previously familiar is altered into something less so. Freud states: “We can only say that what is novel can easily become frightening but not by any means all.

Something has to be added to what is novel and unfamiliar in order to make it uncanny” (2). He means that the unfamiliar by itself is not uncanny, just as the familiar needs an addition to become rooted in horror. Anna Maria Kalinowski bases her study of P.T on this distinction, summarising Freud’s uncanny as “feelings of unsettlement and fear through a threshold of familiarity and the unknown” (4). This statement is true particularly in Cry of Fear and P.T, as the setting of these games lulls the game narrator into a sense of security and familiarity to then invert the sensation into its foreign equivalent. Cry of Fear is modelled around real-life locations in and around Stockholm such as Spånga, Observatorielunden, Cybergymnasiet

Odenplan and Sankt Eriksplan. For a native, these locations are all familiar. Still, even for

players who never visited any of these places, they are modelled to incite familiarity with their accurate architectural structure, using real-life imagery that they rendered into the game environment (see fig 14).

Figure 14. Cry of Fear incorporates real-life locations in Stockholm.

Fig. 14. ‘Saxon Avenue’ modelled after St. Eriksplan in Stockholm. Screenshot from Cry of

A specific part of Cry of Fear stands out more than the others when the game narrator must enter Cybergymnasiet, a school building that serves as a reprieve from the enemies lurking in the city outside. The lights are all on, leaving no dark spaces, structured to be an impressive copy of the real Cybergymnasiet in Stockholm (see fig. 15).

At this point of the game, the game narrator has already had to wander through hallways of enemies, boss battles and bloody rooms to find this school empty and utterly clean. It is a stark contrast against the setting outside of the school being dark and dirty, and it can both make you feel relieved for the break, as well wary of something not being quite right with the pristine appearance of the school. As you go room to room searching for a fuse to power a door in the subway station, you eventually locate it with the realisation as soon as you take it, the school’s electricity will go out, and you will once more have to navigate through the darkness. The familiarity the game narrator is attached to with well-lit school hallways in this seemingly novel school free of enemies shifts as you understand that as soon as you grab the fuse, the school’s familiar façade will cease to exist. Due to the game forcing the game narrator to choose Fig. 15. Cybergymnasiet or 'Harbor College'. Screenshot from Cry of Fear.

to give up their haven for the sake of progress, the effect results in an uncanniness that encapsulate the distinction of the familiar and the unfamiliar, demonstrating how altering the ordinary can result in the uncanny. As the game narrator grabs that significant fuse, they are instantly shrouded in darkness and attacked, having to traverse through a now pitch-black school with enemies hiding in every room and the sound of pounding metal in their ears.

P.T also presents the familiar in its setting, as the teaser takes place in a simple hallway

of a suburban house, impossibly looping with each journey through the L-shaped hallway (see fig 16). The familiarity resides in the novelty of the setting, as it, at first glance, appears to be an average house.

The repeating loop of the hallway is reminiscent of ‘the double’, another concept of the uncanny Freud explains as the “inner ‘compulsion to repeat’” and can be applied in various ways (12). As the game narrator traverses through each loop, the hallway starts to change its appearance subtly. Initially a familiar, typical hallway, the game narrator will eventually doubt

Fig. 16. The never-ending hallway of P.T. 23 May 2021, https://silenthill.fandom.com/wiki/P.T.

whether the spiderweb in the ceiling, scratches on the walls and the layer of dust were there before. The haunted house is a common horror trope, and therefore it is no wonder the uncanny is connected to it, Freud locating multiple examples of ‘an unheimlich house’ translating to ‘a

haunted house’ (14). Slavoj Žižek explores this notion as well; we are reminded of his claim

that “the most familiar things take on a dimension of the uncanny when one finds them in another place, a place that ‘is not right’” (89). This uncanny emotion of not quite right arises when the game narrator walks through the L-shaped hallway and finds themselves, impossibly, back at the beginning. With each loop, the familiarity of the hallway is soon shifted, becoming more and more ‘haunted’, bugs that were previously not present crawling over the walls, shadows of a woman appearing in the corner of your eye and so on (see fig. 17 and 18).

Figure 18. Cockroaches crawling on the walls.

Fig. 17. The hallway illuminated in red light. 23 May 2021, https://silenthill.fandom.com/wiki/P.T.

Slavoj Žižek sums this sensation up as “The effect of uneasiness would be radically “psychologised”; we would say to ourselves, “This is just an ordinary house; all the mystery and anxiety attached to it are just an effect of the heroine’s psychic turmoil!” (74). As we are “closer” to P.T. than the other games, playing in the first-person perspective, the focus of the game lies in trying to incite doubt in the game narrator, the person playing. Is the hallway changing rapidly, or are you hallucinating these discreet changes? This uncanny kernel of doubt separating imagination from reality is what P.T aims to incite in the player. The familiarity of the hallway, originally comforting with its novel appearance, soon becomes unfamiliar with each loop and slight alteration of the environment. The player’s fear does not occur due to traditional horror elements such as graphic gore and body horror, but in the realisation that this ordinary hallway’s sole purpose is to make you fear each traversal through it. This sensation unites the player and avatar; the avatar’s fear becomes the player’s fear. Despite being stationary in front of a screen, you fear what awaits the avatar, that now is an extension of you, Fig. 18. Cockroaches crawling on the walls. 23 May 2021,

the player. The previously mentioned notion of the double defines this relationship as well as the occurrence of the twin in psychological horror.

d.

The Double

The double, I will remind you, Freud defines as the identical copy of an individual, or the telepathic relationship of divided knowledge between characters, or an interchanging of self by relating oneself to another (9). We have considered the latter double in a player/avatar relationship, as the player becomes more static while the avatar is “imbued with life” (Kirkland 2). I have defined this relationship in the game narrator, describing player interaction and avatar movement simultaneously. I will now introduce the death drive that goes hand in hand with the player/avatar relationship, presented by Jeffrey Douglas through the research of Gary Westfahl as the knowledge gained by the player with each death the avatar suffers (2). Using the popular Nintendo game franchise of the Super Mario Bros as an example, quoting Westfahl, he writes: “Literally, the more often Mario dies, the better the player becomes: in a true Zen paradox, players must repeatedly kill their Marios in order to better maintain their lives in future games” (2). This is especially the case in the psychological horror genre of games, as combat and stealth at times go hand in hand. Can you defeat the monsters in your way, or is it safer to avoid confrontation? Is it worth risking death facing your demons, or do you choose to save energy and ammo for a more dangerous enemy that will inevitably appear further into the game? With each trial and error, the player gains knowledge of what they are capable of surviving. The player may lose time if they die, as saving your game and ensuring progress cannot be made by the click of a button but by interacting with sparse objects hidden in the environment. The avatar will continuously be resurrected into an identical self with each death, creating multiple doubles, the knowledge that is gained and learned from the avatar’s destruction and resurrection I believe to be equivalent of to what Freud understands as the telepathic connection between

the doubles: “the one possesses knowledge, feelings and experience in common with the other” (9). The player gains experience with each avatar’s death, having to fail to succeed, defining the “inner compulsion to repeat despite repulsion” that resides in the centre of the uncanny (Brown and Marklund 4).

Having considered the double present in the player/avatar relationship, I now turn to the double I believe to be present in the video game narratives. As Freud states, the first part of the double can be defined as “characters who are to be considered identical because they look alike” (9). I interpret this to be a doppelgänger, an identical other that may or may not share these previously mentioned experiences and feelings as their twin. In psychological horror game narratives, as much of the narrative is internal and focused on the protagonist’s mental state, the struggle is done by facing a physical version of themselves in a symbolic act of taking back control. It represents the protagonist’s main antagonist being themselves, the narrative unravelling to reveal their internal battle to better themselves, ending with this last confrontation.

Cry of Fear features such a confrontation, as we are aware of the external plot being Simon, our protagonist, writing down his feelings and thoughts in a book to hopefully escape depression and regain the will to live. The game narrator controls Simon within this book, struggling against inner demons and finding a way out of Stockholm that symbolises his mentality of being lost internally and externally. The final boss fight in the game is a psychosis-induced hallucination in which disabled, external, Simon battles internal, Book Simon, the game narrator now controlling the external Simon. There are multiple endings to the game, but the one where the game narrator can defeat internal Simon is the better one. Once you beat the internal Simon, the external Simon accepts his psychosis and is admitted to a mental hospital (see fig. 19).

The purpose of the two Simons is to manifest the internal struggle of the real Simon, how he refuses to accept his reality and instead has turned bitter with the hopelessness of his condition. Depending on the choices the game narrator makes, Simon may end up committing suicide or getting the help he needs, decided by the symbolic choices of fleeing or facing difficulties in the game, the latter resulting in the real Simon facing the root of his issues – himself.

In Silent Hill 2, there exists another sort of doppelgänger, Maria, identical to James’ wife Mary, although slightly different appearance-wise. According to James, they share the same face and voice, and he initially mistakes Maria for his deceased wife. In their first meeting, James says: “I can’t believe it, you could be her twin. Your face, your voice… just your hair and clothes are different.” Maria is a more extroverted version of Mary, dressed in revealing pink clothes and blonde hair instead of Mary’s brown.

Seemingly an omniscient antagonist, Maria shares memories and experiences with Mary, suggesting she is only a construction of James’ delusion and guilt for killing his wife. After Maria is caught and killed, she impossibly returns and speaks to James, who is shocked at her survival. She responds: “Are you confusing me with someone else? You were always so forgetful, remember that time at the hotel?” (See fig. 20). The hotel being Mary and James’ special place where they had vacationed, causing James to doubt whether Maria is real or a figment of his imagination somehow connected to Mary.

Maria appears to share memories and experiences with Mary, suggesting she is the double described by Freud as sharing a telepathic relationship with its twin, feelings and knowledge divided between the two (9). Maria needs James’ protection throughout the game. She inevitably gets hurt and rests in one of the hospital beds, depending on how much the game narrator returns to check on her impacts the ending. Caring for Maria draw parallels between Fig. 20. Maria reminding James of his vacation with Mary. Screenshot from Silent Hill 2.

Mary’s hospitalisation and James’ failure to support and care for her properly; as stated in her letter, he seemed disgusted by her.

Therefore, the double can be interpreted as the therapeutic confrontation of the internal emotions plaguing James and Simon. The doppelgänger is designed to manifest an abstract inner battle to the player, who can only see and interpret what is visually represented. Through the presence of the doppelgängers, we get to see and interact with a Mary constructed by James’ imagination, perhaps out of what he wished his wife would have been when she was alive, just as we get to experience Simon’s struggle with his life through the Book Simon we control. I interpret that the doubles exist both to incite doubt at which version is real or imaginary, characterising the narrative by manifesting the repressed elements of the protagonist into something more tangible for the player. As Freud repeatedly states, the uncanny can be summarised by the repressed parts; something that ought to have remained hidden but has come to light; I believe that the creation of the doubles is to bring elements to light that the player would have otherwise overlooked.

e.

Video Game Fiction and Written Fiction

Having considered the uncanny and its impact on player, avatar, and narrative, I want to conclude the discussion by comparing the video game- and written fiction. I have until now only mentioned in passing the different aspects the player may affect the story in these games and how the interactive relationship between player-avatar is unique to video game fiction. As a reminder of the nature of a video game narrative, it is not a term exclusive for all sorts of video games but specific to the ones dedicated to telling a story. This includes psychological horror but also other genres such as adventure and RPG’s (Role-Playing Games), where the player takes on a role in the fictional world as described by Robson and Meskin (5). Robson and Meskin define interactive fictions, specifically video game fiction, as concerning the