Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rere20

Educational Research

ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rere20

Understanding bullying from young people’s

perspectives: An exploratory study

Lisa Hellström & Adrian Lundberg

To cite this article: Lisa Hellström & Adrian Lundberg (2020): Understanding bullying from young people’s perspectives: An exploratory study, Educational Research, DOI: 10.1080/00131881.2020.1821388

To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2020.1821388

© 2020 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group.

Published online: 23 Sep 2020.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 255

View related articles

Understanding bullying from young people’s perspectives:

An exploratory study

Lisa Hellström and Adrian Lundberg

Department of School Development and Leadership, Malmö University, Malmö, Sweden

ABSTRACT

Background: Common definitions of bullying, employed in research and public policy alike, are generally based on adult- imposed categories. To account for students’ needs in school, research should aim to include their voices more often. However, a major challenge for educational research in general, and bullying research in particular, is finding methods that enable students to participate in the discussion.

Purpose: The aim of this small, exploratory and in-depth study was to further the understanding of bullying and provide insights by examining students’ subjective viewpoints about bullying.

Method: Using Q methodology, a total of 29 Swedish 11- and 13- year-olds from one school were given a Q set, comprising 23 items to rank order. Aspects such as the characteristics, modes and types, as well as the context of bullying, were taken into account in the construction of the Q set. Through analysis it was possible to identify two distinct viewpoints, which were then qualitatively interpreted and described.

Findings: The viewpoints which emerged within this small, exploratory analysis suggested some interesting distinctions and age-related emphases. Specifically, the older students tended to rank items taking place offline as more severe, compared with items describing bullying taking place online. Further, bullying in private settings was perceived as more severe amongst the younger stu-dents, while items describing repetitive bullying in public settings appeared to be of greatest importance when defining bullying behaviour amongst the older students. The relational types of bullying were not ranked as highly characteristic for bullying by younger or older students.

Conclusions: Further research with larger data sets is necessary to investigate these emerging findings. The study draws attention to the need for adults to maintain a focus on students’ behaviours offline, as well as online: in this highly digital age, it is easy for the offline context to be inadvertently overlooked. When it comes to younger students, anti-bullying efforts targeting bullying in private settings and acknowledging potential harm may be more suitable than anti-bullying efforts targeting stigma and shame, which may, in turn, better support the needs of older students. The study also shines a light on the importance of using participatory methodol-ogies that allow students to express their own perspectives.

ARTICLE HISTORY

Received 11 December 2019 Accepted 6 September 2020

KEYWORDS

Bullying; definition; school students; wellbeing; Q methodology; student voice

CONTACT Lisa Hellström lisa.hellstrom@mau.se https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2020.1821388

© 2020 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any med-ium, provided the original work is properly cited, and is not altered, transformed, or built upon in any way.

Introduction

With its negative consequences for wellbeing, bullying is a major public health concern affecting the lives of many children and adolescents (Holt et al. 2014; Liu et al. 2014). Bullying can take many different forms and include aggressive behaviours that are physical, verbal or psychological in nature (Wang, Iannotti, and Nansel 2009). Bullying can also include behaviours that aim to disrupt relationships; it can take place online as well as offline (Slonje and Smith 2008). With the increasing use of the internet as a platform for building peer relations, much of the communication and incidents of victimisation among children and adolescents remains hidden to the adult world, making the situation somewhat difficult to comprehend (Patchin and Hinduja 2015). The involve-ment of new media may have changed the ways in which children and adolescents are bullied, as well as the perceived boundaries for acceptable behaviours (Rigby and Smith

2011).

An urgent matter of concern is what adults can do to provide assistance and support in reducing the amount of stress and anxiety experienced by young people which results from online and offline victimisation. The lack of knowledge and understanding about what young people perceive to be bullying, including both indirect and direct behaviours, may contribute to why adults may be unable to intervene effectively, if they intervene at all (Gropper and Froschl 2000; Boulton and Hawker 1997; Hopkins et al. 2013). In case of discrepancies between young people’s and adults’ understandings of bullying, the sug-gestion is often to adjust young people’s definitions to better coincide with researchers’ definitions (Frisén, Holmqvist, and Oscarsson 2008; Hopkins et al. 2013; Maunder, Harrop, and Tattersall 2010). However, when the voices of young people are heard in these matters, effective support can be designed based specifically on what young people want and need rather than what adults interpret and understand to be supporting the young people (O’Brien 2019). Drawing on recent research literature, the following sections illustrate and discuss some common aspects of bullying. First, the distinction between offline and online bullying is explored. Then, different modes, types and contexts of bullying are outlined, before various gender and age differences are discussed. Finally, a section about commonly used methods in bullying research leads to the purpose of the present study – that is, to further the understanding of bullying and provide insights by examining students’ subjective viewpoints.

Background

Definitions and characteristics of offline and online bullying

Continuing efforts to address bullying among children and adolescents underscore the need for a clear and consistent definition and an understanding of what it means to be a victim and a perpetrator of bullying (Thomas et al. 2017). The most widely adopted definition of bullying by both researchers and policymakers was developed by Dan Olweus (Olweus 1978), who defined bullying as direct and indirect aggression that (a) is intentional, (b) is repeated, and (c) involves a power differential between the aggressor(s) and the target. Even though Olweus’ definition of bullying is the most widely used conceptualisation of what constitutes bullying, there is some critique involving the

application and importance of the three distinct criteria intended to separate bullying from other forms of aggression. In addition, it is evident that young people and adults do not always share the same understanding of what it means to be bullied (Hellström, Persson, and Hagquist 2015; Vaillancourt et al. 2008; Younan 2019), thus adding to the complexity of reaching an understanding of how to address bullying based on what young people want and need. For example, in their qualitative study, Jeffrey and Stuart (2019) found that even when the concepts of intent, repetition and power imbalance were included in children’s definitions of bullying, they may not necessarily be function-ally equivalent to adults’ understandings. The intent behind the action is a criterion included in the definition of bullying. However, children seldom mention the harmful or hurtful intention and they tend to focus more on the effect on the victim as an important criterion when asked to define bullying (Guerin and Hennessy 2002; Hellström, Persson, and Hagquist 2015; Madsen 1996). Repetition is another criterion used to define bullying behaviour, where different cut off points to define repetition are evident in different studies. No generally accepted cut off point exists, making it hard to compare prevalence rates between studies and to grasp fully the severity of the situation (Rigby 2006b; Solberg and Olweus 2003).

Lastly, the concept of power imbalance has proved hard to operationalise and capture in assessments among children, as different forms of power are not always stated or may not always imply difficulty for the young person being bullied to defend him- or herself (Green et al. 2013). For example, bullying may be used as a means to achieve social power (Thornberg and Delby 2019). Power imbalance may be situationally bound and can change over time; measures of bullying might not detect the subtle forms of power imbalance that separates it from aggressive behaviour that is neither intentional nor repetitive (Green et al. 2013; Rigby 2006a).

The application and importance of the criteria used to define bullying may also be challenged by the changing conditions within young people’s social environments, particularly as communication is increasingly taking place online (Dooley, Pyżalski, and Cross 2009; Nocentini et al. 2010). Hence, there is ongoing debate about how far online bullying should be defined and conceptualised differently from or similarly to offline bulling (Englander et al. 2017; Olweus 2017). The definition of cyberbullying sometimes includes the traditional definition of bullying with the additional specification that it occurs through an electronic device or digital means (Berne, Frisén, and Berne 2019; Campbell and Bauman 2018; Kowalski et al. 2014), while others argue that cyberbullying is a separate phenomenon compared with traditional forms of bullying, requiring its own distinct definition (Cross, Lester, and Barnes 2015). Indeed, specific criteria such as anonymity and publicity have been proposed for the definition of cyberbullying (Menesini and Nocentini 2009; Slonje and Smith 2008). Compared with offline bullying, online bullying has an increased potential for a large audience, anonymous bullying, lower levels of direct feedback, decreased time and space limits, and lower levels of supervision (Sticca and Perren 2012).

The criterion of repetition illustrates some of the complexities involved in seeking to tease out the distinctions between online and offline bullying. Due to the rapidity of dissemination and follow-up effects of online victimisation, every action taken online has the potential to be repeated, which brings into question how the criterion of repetition should be handled when it comes to defining online bullying (Dooley, Pyżalski, and Cross

2009; Patchin and Hinduja 2015). Further, the criteria of intention to harm and power imbalance are more difficult to apply in an online environment (Patchin and Hinduja 2006,

2015), and recent research has shown that children seldom include traditional criteria to define cyberbullying (Moreno, Suthamjariya, and Selkie 2018). In sum, the uncertainty concerning the application and importance of the criteria shaping the definition of offline and online bullying represents a considerable challenge for this field of study, which needs to be acknowledged at the start of all research endeavours in this area (Finkelhor, Turner, and Hamby 2012).

Modes and types of bullying

Bullying can be expressed in different ways and includes aggressive behaviours that can be direct or indirect (modes) and physical, verbal or relational (types). As discussed in the section above, developing frameworks for defining bullying behaviour is complex and full theoretical discussion is beyond the scope of this paper. In this section, we outline some distinctions in terms of modes and types of bullying that we have found helpful to our investigation, whilst recognising that other ways of distinguishing categories are also of value in furthering the understanding of bullying.

Direct bullying of young people can be defined as those behaviour(s) that occur in the presence of the targeted young person. Examples include face-to-face interaction such as pushing, hitting or directing aggressive written or verbal communication at a young person (Gladden et al. 2014; Van der Wal, De Wit, and Hirasing 2003). Direct physical actions can only happen offline. Indirect bullying comprises those behaviour(s) that are not directly communicated to the targeted young person. Examples are rumour- spreading or gossiping, either offline or online (Gladden et al. 2014; Björkqvist and Österman 2018). Indirect bullying can only be public, due to the involvement of a third person. Different types of bulling include physical aggression where the perpetrator(s) use physical force against a targeted young person; i.e. hitting, kicking, punching, spitting, tripping, and pushing. Verbal bullying is oral or written communication that causes the targeted young person harm; i.e., mean taunting, calling names, threatening or offensive written notes or hand gestures, inappropriate sexual comments, or threats (Gladden et al.

2014). Verbal public actions online can only be repeated (Thomas et al. 2017; Menesini et al. 2012). Relational bullying is designed to harm the reputation and relationships of the targeted young person; i.e. actions intended to isolate the target by keeping him or her from interacting with peers or ignoring them (direct relational bullying), or spreading false and/or harmful rumours, publicly writing derogatory comments or posting embarrassing images online or offline without the target young person’s permission or knowledge (Gladden et al. 2014).

Context of bullying

When it comes to evaluating bullying severity, Sticca and Perren (2012) suggest that the role of publicity and anonymity is of greater importance than the arenas for bullying (i.e. offline vs online). Research indicates that bullying acts that are acknowledged by a larger group of people and that are public (e.g., offences occurring in a public forum, or videos or pictures distributed via social networking sites) are perceived as more severe compared

with private exchanges of bullying between two parties (Slonje and Smith 2008; Smith and Slonje 2010; Nocentini et al. 2010). Hence, the presence and actions of bystanders seems to be of importance when judging bullying behaviour. The role of the bystander, i.e. those students who witness bullying, is now maintained to be of particular significance in bullying situations (Wiens and Dempsey 2009). Bystanders are considered important not least because their behaviour and reactions will sustain the social norm (Craig, Pepler, and Atlas 2000). They provide direct feedback about the acceptability of behaviour by reacting in a certain way and can choose to actively or passively reinforce the aggressive behaviour, or to support the victim (Quirk and Campbell 2015; O’Connell, Pepler, and Craig 1999).

Bullying and student characteristics

Some evidence suggests that the understanding of bullying and the types of victimisation experienced by children may differ in relation to gender and age. While some research has found no differences between boys and girls (Guerin and Hennessy 2002), other research has found that the effect on the victim is more often mentioned among girls in their understanding of bullying behaviour than by boys (Frisén, Holmqvist, and Oscarsson

2008; Thornberg and Knutsen 2011). In their study, Hellström, Persson, and Hagquist (2015) found that boys reported fewer behaviours as bullying in comparison with girls, and a larger proportion of girls considered behaviours online and behaviours involving the peer group as bullying. Further, while boys are more likely than girls to engage in direct physical bullying, verbal bullying seems to be just as common among girls as boys, and girls have been reported to more frequently engage in indirect, relational and social bullying than boys (Björkqvist and Österman 2018; Hwang et al. 2018). However, the idea that girls would be more indirectly aggressive than boys has been criticised and studies have shown contradictory results (Salmivalli and Kaukiainen 2004; Olweus 2009).

Further, students’ conceptualisation of bullying behaviour changes with age, as there are suggestions that younger students tend to focus more on physical forms of bullying (such as fighting), while older students include a wider variety of behaviours in their view on bullying, such as verbal aggression and social exclusion (Monks and Smith 2006; Smith et al. 2002; Hellström, Persson, and Hagquist 2015). A recent systematic review indicates that older students (14 years and over) were able to differentiate between aggressive and non-aggressive behaviour, physical and non-physical bullying and also characterise bully-ing behaviour as involvbully-ing a power imbalance and repetitive behaviour, whereas younger participants (4-8-year-olds) could only differentiate between aggressive and non- aggressive behaviour (Younan 2019). This suggests that cognitive development may allow older students to conceptualise bullying along a number of dimensions (Monks and Smith 2006). Further, some research has indicated that younger students tend not to be repeatedly victimised over long periods of time (Kochenderfer and Ladd 1997), mean-ing that younger and older students may differ in includmean-ing repetition as a part of their definition of bullying.

Overall, young people as well as adults tend to perceive aggressive behaviours, such as hitting, threatening and calling names, as more severe compared with aggressive beha-viours such as rumour-spreading and social exclusion (Maunder, Harrop, and Tattersall

behaviours may imply that schools need to apply different target intervention strategies, depending on a range of different factors.

Ways of researching young people’s understanding of bullying

As young people’s actions are grounded in how they understand and interpret the world and not in what adults or researchers see as objective reality, understanding students’ perception of what types of behaviours are considered to be bulling is important in the undertaking of understanding and addressing bullying in schools (Gamliel et al. 2003; Varjas et al. 2008). Hence, to understand bullying among young people more comprehensively, their own perspectives need to be taken into consideration (Hellström, Persson, and Hagquist 2015). However, a major challenge for researchers is to find methods that will enable adolescents and children to be able to provide the information that scholars seek (Owens 2016).

Numerous efforts have been made to investigate different stakeholders’ definitions and perceptions of bullying, which has made researchers sometimes refer to the assess-ment and measureassess-ment of bullying as the ‘Achilles heel’ of prevention efforts (Cornell, Sheras, and Cole 2006). Quantitative research designs, which have long dominated the field of bullying research (Eriksen 2018), are often constructed based on researchers’ understanding rather than constructing the design from the viewpoint of young people interpreting their own lived experiences (see Canty et al. 2016). For example, some questionnaires inform students what bullying is by including different criteria, so this is predetermined before they respond to the questions. Although this direction can be helpful in focusing the student on the task, it risks limiting young people’s expressions of what might really be troubling them at school, thus restricting their thinking about bullying to a narrow set of phenomena (Naylor et al. 2006; Duncan and Owens 2011). Quantitative studies also require large samples of respondents and may need students to possess reasonable literacy skills in order to respond. Qualitative studies, which may rely on students’ verbal skills, are less plentiful. Moreover, it must be remembered that asking students to express experiences of emotionally charged situations, for example concern-ing bullyconcern-ing, is particularly challengconcern-ing (Ellconcern-ingsen, Arstad Thorsen, and Størksen 2014) and constitutes another reason why this important area of research is difficult and complex to design and investigate.

In order to fully account for young people’s needs in school and, eventually, build a truly inclusive educational environment, research should aim to include students’ voices more often (de Leeuw et al. 2019; Sargeant and Gillett-Swan 2019) and potentially in a non-verbal way. As de Leeuw et al. (2019) state in their study about young children’s perspective on resolving social exclusion, ‘the question is not whether the participation of young children should occur within educational research and educational reform, but rather how this can be accomplished’ (p. 325, italics in original). The same is true for older children, as providing additional examples of youth perceptions of bullying could help inform the development and refinement of future bullying prevention programmes (Ybarra et al. 2018).

Purpose

Against this research backdrop, the need for studies investigating bullying from young people’s perspectives led to the aim of the current study, which was to contribute to the

understanding of bullying by examining students’ subjective viewpoints on bullying. The study was therefore designed to address the following research question: What are

students’ subjective viewpoints on bullying behaviour?

Methods

Participants

The researchers were contacted by the participating school as part of the school’s preventive anti-bullying work. Two classes within the school were involved; students aged 11 (Grade 5) and 13 (Grade 7) were invited to participate in the study. As a result of this process, a total of 29 students (13 Grade 5 students (9 girls and 4 boys) and 16 Grade 7 students (8 girls and 8 boys)) took part, which comprised the majority of the students invited. Both researchers were present during the collection of the empirical data and the data collection was scheduled so that the students would not miss any classes.

Ethical considerations

As explained above, this project was part of the participating school’s anti-bullying work and the researchers were contacted by the school. Ethical advice was sought from the chair of the Research Ethics Council at the researchers’ university. The caregivers of the respondents were asked to sign an informed consent form, which was required for their child’s participation in the study. Also, the students themselves had to assent to their participation. The students, as well as their caregivers, were informed about the aim of the study and that no individual experiences with bullying would be asked for, that participa-tion was voluntary and that the students could withdraw their participaparticipa-tion at any point. Participating students and their caregivers were further assured of confidentiality, as no names or personal data or names of other people or locations involved in the study would be collected or presented in such a way to risk identification.

Methodology

To respond to the research question posed in this study, Q methodology was selected because of its usefulness in organising and measuring subjective viewpoints of partici-pants regarding significant personal experiences, as well as its benefit of being a less intrusive way of gathering data among children (Ellingsen, Arstad Thorsen, and Størksen 2014; Brown and Good 2010). Q methodology is concerned with individuals’ subjective perspectives, which are communicable and advanced from a self-referential position (Owens 2016). In Q methodology, individuals respond to a set of items, including items that refer to feelings, thoughts, preferences and opinions related to facts or figures, using a card sorting process. This rank-ordering procedure, with its play- like character, can facilitate the expression of views and experiences for children (Ellingsen, Arstad Thorsen, and Størksen 2014; Ellingsen, Størksen, and Stephens

2010). Participants’ responses can then be analysed and the findings interpreted in a qualitative fashion (Brown and Good 2010; Watts and Stenner 2012). Q methodology,

and in some cases exclusively its card sorting technique, has been used in various ways previously; for example, to explore different roles of bullying participation and social competence among preschool children (Camodeca and Coppola 2016; Camodeca, Caravita, and Coppola 2015) and also to investigate popularity attribution among teenage girls (Owens and Duncan 2009; Owens, Feng, and Xi 2014; Duncan and Owens 2011).

Development and piloting of the research instrument

The main source of information and knowledge drawn upon in the construction of the research instrument was recent literature outlined earlier. To ensure that the final Q set captured different modes, types and contexts of bullying, findings and definitions from qualitative and quantitative research were integrated. In summary, the following types of bullying behaviours were identified and represented in the Q set: physical bullying and verbal bullying (direct bullying), relational bullying (such as social exclusion) and indirect acts (such as rumour-spreading or posting something mean online). Further, acknowl-edgement and recognition that bullying can take place on the internet, as well as face-to- face, was captured by alternating online and offline behaviours in the items comprising the Q set.

So as to capture up-to-date communication platforms and explore different types of social media, computer games, and other online activities of relevance to the target group, a participatory research approach was chosen (Bergold and Thomas 2012). In this way, we aimed to make the situations as authentic and close to the everyday life of today’s young people as possible. Participating classes were thus involved in an explora-tory and rather informal discussion about their familiarity with and usage of aforemen-tioned digital channels, guided by their physical education and health teacher. The discussion’s outcome led to the inclusion of a broader range of digital channels into the Q set, due to the participatory contribution of the classes.

Further, as some research has suggested that bullying acts that are acknowledged by a larger group of people and that are public (e.g., offences occurring in a public forum, or videos or pictures distributed via social networking sites) are perceived as more severe compared with private exchanges of bullying between two parties (Slonje and Smith 2008; Smith and Slonje 2010; Nocentini et al. 2010), these aspects were also taken into account in the compilation of the Q set. Finally, regarding the commonly used criteria for bullying, different cut off points for repetition were included and expressed as: behaviours happen-ing every day, or every time a certain event takes place, or as behaviours happenhappen-ing for the first time. As the harmful or hurtful intention behind an action may take on lower signifi-cance when children themselves define bullying (Guerin and Hennessy 2002; Hellström, Persson, and Hagquist 2015; Madsen 1996), and power imbalance has proved hard to operationalise and capture in assessments among children (Green et al. 2013), such aspects were excluded when compiling the Q set. It was determined that inclusion of these aspects would have meant that many more combinations of behaviours, definitional criteria and arenas would have had to be taken into account, thus making the compilation of bullying too complex to study in a reliable way, as the sorting of large Q sets can be extremely demanding for children and adolescents (Watts and Stenner 2012).

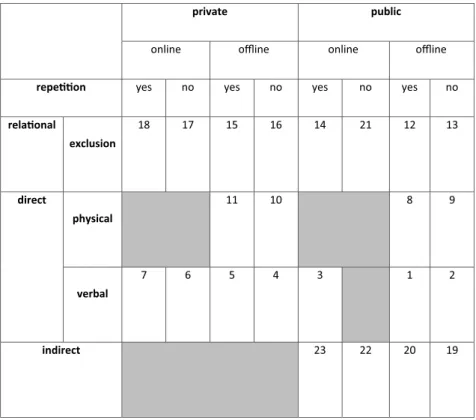

This process resulted in the development of a 23-item scenario Q-set. A pilot study was then performed, involving three students in the evaluation of the 23 item scenarios and in exploring whether they considered that any important aspects of bullying or different bullying behaviours had been left out of the Q set. Apart from correcting a couple of spelling mistakes, no changes were made and no items were added after the pilot study was completed. The combinations of bullying characteristics, modes and types of bullying and contexts of bullying were summarised into 23 different items (relationships shown in

Figure 1; item wordings presented later in the article in Table 1).

Data collection and analysis procedure

First, the students completed a short questionnaire, supplying the basic demographic information (as above in the subsection on participants) and giving an indication of their usage of various social media, online communication means and online games. Of the 29 students, most or all reported using Snapchat or Instagram; roughly between one third and two-fifths of students (between 9 and 12 students) reported using Facebook, Messenger, Tiktok, WhatsApp and Fortnite. Next, the students were asked to perform the card-ranking activity using the 23 items on bullying behaviours. Each item had to be

c i l b u p e t a v i r p

online offline online offline

repe on yes no yes no yes no yes no

rela onal exclusion 18 17 15 16 14 21 12 13 direct physical 11 10 8 9 verbal 7 6 5 4 3 1 2 indirect 23 22 20 19

Figure 1. Combinations of bullying characteristics, modes and types of bullying and contexts of bullying summarised into the 23 item scenarios. Notes: Four combinations of categories were excluded and are marked grey in the table.The numbers 1–23 refer to the item numbers for the scenarios (see Table 1 later in the article for the item scenario wordings).

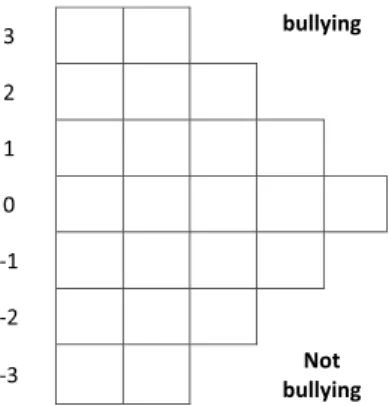

assigned a hierarchical position in a forced-choice, quasi-normal and symmetrical dis-tribution, according to the extent to which the situation was felt to describe the participant’s understanding of bullying. By ranking single items in relation to all other items, instead of merely rating items separately, students could indicate which of them, based on their subjective perspective, were particularly characteristic (+3) or not at all characteristic (−3) of bullying. It is this specific strength of Q methodology that enables indication of how items ranked as more characteristic of bullying are most likely to represent more severe and damaging bullying situations. It is important to note that, unlike more traditional Q methodological studies using a horizontally oriented distribu-tion grid, in the current study the most negative value represented the bottom of the grid while the most positive value was located at the top of the grid (Figure 2). Rotating the distribution grid by 90° allowed the respondents to follow a more instinctive rank ordering process. The aim of this dynamic procedure was to generate a single and holistic configuration of all the items, consisting of each participant’s constant compar-ison between items. The product is considered to be a dynamic representation of their viewpoint on the subject.

In line with the conceptual underpinning of Q methodology, data from all participants was analysed collectively and no preconceived categorisation was applied prior to the interpretation of emerging factors (Watts and Stenner 2012). The dedicated software called PQMethod (Schmolck, 2014) was used. The most informative solution, featuring two factors, was reached and a total of 27 out of 29 sorts loaded exclusively on one of the factors at the p < 0.01 level. They could therefore be used for the creation of the factor arrays, achieved through a procedure of weighted averaging. These single ideal-typical Q sorts formed the basis for interpretation, while additional measures in the PQMethod result sheet and demographic information further increased the richness of Q factor descriptions and served confirmatory purposes.

Findings

In step with common practice in Q methodology to accentuate the subjective character of the results and illustrate the participants’ own way of seeing the phenomenon under scrutiny, the described factors from this study will be called viewpoints. Table 1 shows the

3 bullying 2 1 0 -1 -2 -3 Not bullying

values assigned to each identified viewpoint for each of the 23 item scenarios (item scenarios are presented in translation).

Viewpoint 1 accounted for 28% of the study’s opinion variance and consisted of 14 significantly loading Q sorts. Three of them were 11-year-old students and 11 of them were 13-year-old students. Repeated actions almost entirely took up the highest ranked positions in the factor array for Viewpoint 1. Only the item describing repeated online, private exclusion ranked very low (item 18: Y never receives any response from X when s/he

tries to talk while playing Fortnite online.). The second highest ranking was assigned to the

repeated situation which describes physical bullying in a public offline context (item 8:

During every recess, X pushes Y in front of their peers.). Its non-repeated manifestation (item

9: Y is pushed off his/her chair by X during a maths lesson.) was ranked at −2, creating a large difference between these two related situations. A similarly large difference was detected for the private pair of situations of physical bullying (item 11; X hits Y with his/her bag pack

every morning while alone on the school bus. and item 10: Y is kicked by X when they are alone one afternoon.).

In contrast with the dominance of repeated situations in the top half of the distribution, the highest ranked item describes a situation where adolescents are publicly and indirectly bullied in an offline setting that only happens once (item 19: Y is a victim of a false rumour by

X during a break.). Nevertheless, this is the only online-offline pair of situations where the

non-repeated manifestation was ranked higher than its repeated one. Interpreting the online-offline distinction, Viewpoint 1 respondents tended to regard face-to-face situations as more characteristic of bullying than actions taking place online, especially when they were repeated. Indirect situations of bullying were generally ranked high, notably when they were experienced in offline situations (item 19: Y is a victim of a false rumour by X during

Table 1. Q set consisting of the 23 item scenarios used in the card-ranking activity, showing the values assigned to each identified viewpoint.

(Item) Scenario V1 V2

(1) Y is always made fun of by X when s/he speaks in front of the class. 0 0 (2) X calls Y mean things in front of his/her peers for the first time. −1 0 (3) Y receives mean comments by X on multiple pictures posted on Instagram. 1 1 (4) X is calling Y mean things on one occasion when they are alone in the restroom. −2 1 (5) X teases Y during every recess, when nobody can see it. 2 2

(6) Y receives a mean Messenger message by X. −1 −1

(7) Every morning on the school bus, Y receives a mean Messenger message by X. 2 0 (8) During every recess, X pushes Y in front of their peers. 3 2 (9) Y is pushed off his/her chair by X during a maths lesson. −2 1

(10) Y is kicked by X when they are alone one afternoon. 0 3

(11) X hits Y with his/her bag pack every morning while alone on the school bus. 2 3 (12) Y is not allowed to participate in any games or activities during recess. 1 0 (13) Y is not invited to the party whereas everybody else from the same class is. 1 −1 (14) Y is not allowed to be a part of it each time the class chat on Snapchat. 0 −2 (15) Y is constantly prevented from working with X during school activities. 0 −1 (16) Y is not allowed to play with X when s/he has a new computer game. −1 −3

(17) Y’s Friend request to X on Facebook is ignored. −3 −3

(18) Y never receives any response from X when s/he tries to talk while playing Fortnite online. −3 −2 (19) Y is a victim of a false rumour by X during a break. 3 2 (20) Every time Y leaves the room, X talks badly about him/her to their peers. 1 1 (21) Differently from all the others, Y is not tagged on X’s new Instagram picture. −2 −2

(22) X posts an embarrassing video of Y on TikTok. −1 0

(23) Every time X posts a picture on Instagram, s/he mentions Y in a mean hashtag. 0 −1 Notes: V1 = Viewpoint 1; V2 = Viewpoint 2.

a break. and item 20: Every time Y leaves the room, X talks badly about him/her to their peers.).

Repeated verbal bullying in a private setting (item 5: X teases Y during every recess, when

nobody can see it. and item 7: Every morning on the school bus, Y receives a mean Messenger message by X.) constituted two of the four most characteristic situations in the factor array

for Viewpoint 1. Across all situations of verbal bullying, the repeated situations were perceived as much more damaging. Generally, the relational types of bullying were not ranked as highly characteristic for peer victimisation. In fact, the two least characteristic situations to Viewpoint 1 were items 17 (Y’s friend request to X on Facebook is ignored.) and 18 (Y never receives any response from X when s/he tries to talk while playing Fortnite online.). Together with item 21 (Different from all the others, Y is not tagged on X’s new Instagram

picture.), it suggests that online social exclusion was not perceived as bullying. From the

pool of the relational types of bullying, only items 12 (Y is not allowed to participate in any

games or activities during recess.) and 13 (Y is not invited to the party where everybody else from the same class is.) received a value greater than 0; that is 1.

Viewpoint 2 accounted for 26% of the study’s opinion variance and consisted of 13 significantly loading Q sorts. In contrast with Viewpoint 1, with 9 students, the respondents on this factor were mainly 11-year-old students. The remaining four were 13-year-old students. The three most characteristic situations for bullying, according to Viewpoint 2, were all physical actions. The ones committed in privacy (item 11: X hits Y with his/her bag pack every morning while alone on the school bus. and item 10: Y is kicked by X when they are alone one afternoon.) were experienced as even more damaging than when around other people (item 8: During every recess,

X pushes Y in front of their peers. and item 9: Y is pushed off his/her chair by X during a maths lesson.). At the other end of the continuum of what Viewpoint 2 respondents

defined as bullying are situations of social exclusion. Except for item 12 (Y is not

allowed to participate in any games or activities during recess.), which was ranked 0, all

items of this type were located in the bottom half of the distribution. In fact, the six least characteristic situations used in this study were all within the relational type of bullying. Indirect and verbal bullying situations were assigned values between 2 (item 5: X teases Y during every recess, when nobody can see it. and item 19: Y is

a victim of a false rumour by X during a break.) and −1 (item 6: Y receives a mean Messenger message by X. and item 23: Every time X posts a picture on Instagram, s/he mentions Y in a mean hashtag.). With only small differences between the repeated

and the non-repeated manifestations of the related situations, no clear pattern for the criterion of repetition could be found in Viewpoint 2. The same was true for the online-offline distinction. The only notable difference was detected in verbal private bullying situations, where the offline form was considered more damaging.

Discussion

The aim of the current investigation was to contribute to the understanding of bullying by examining students’ subjective viewpoints on the subject of bullying. Whilst it must be recognised that this was a small scale, exploratory study within one school, and general-isation is, of course, not intended, interesting differences in emphases between the younger and the older students’ responses in the study were apparent in the two view-points that were identified by the analysis.

Specifically, Viewpoint 2, which was mainly formed by the younger students, ranked items, especially the non-repeated ones (item 9 and item 10), in this category of physical bullying generally higher. Further, the younger students seemed to find the aspect of privacy to be of more importance in situations when physical bullying was taking place, in comparison with the situation taking place in public. It is possible that this finding could be an indication of age-related bullying behaviour, where younger students may be more focused on physical forms, whereas for older students bullying behaviour tends more often to represent the sending of a mean message via social media (Hellström, Persson, and Hagquist 2015; Monks and Smith 2006). It may also suggest that any physical bullying that is taking place with no one else around could, perhaps, be seen as more severe among younger students. Hence, the risk of the situation turning into something harmful may be of greater importance when defining bullying than the risk of stigma and shame involved in being physically bullied in front of others. This emphasis differs from some previous research suggesting that bullying acts that are acknowledged by a larger group of people may be perceived as more severe, compared with private exchanges of bullying between two parties (Slonje and Smith 2008; Smith and Slonje 2010; Nocentini et al.

2010). Our findings may highlight the need for adults to be present as far as possible to witness and intervene in physical bullying situations, especially in the case of younger students.

Meanwhile, Viewpoint 1, which was mainly formed by the older students, ranked items that were repeated, and taking place offline in a public setting to be of greatest importance when defining bullying behaviour. Hence, behaviours offline were ranked higher compared with behaviours ranked online. This was, in part, resonant with earlier research that indicates that the criteria of publicity and anon-ymity seem to be of greater importance than whether the bullying takes place offline or online when deciding severity (Sticca and Perren 2012). The current study offers a contribution by indicating that public behaviours offline may be regarded as more severe compared with public behaviours online. Hence, it is possible that the pre-sence and actions of physical bystanders might be of greater importance for older students when judging bullying behaviour. The interpretation of younger and older students’ different viewpoints on the severity connected to private or public actions could be that younger students’ definitions are based more on fear of what can happen when no one is around, while older students’ definitions might be based more on fear of the stigma and shame of being bullied in front of others. This could be interpreted in line with research suggesting that younger students describe bullying as being mean, while older students focus more on the emotions associated with being a victim of bullying (Byrne et al. 2016). In the current study, no differ-entiation was made if the public situations included the presence of adult school personnel or peers only. However, because social exclusion was described as more characteristic of bullying when experienced in public, we suggest that it would be helpful for future research to include this variable to investigate whether students use adult presence – or the lack of it – as a tool in their understanding of bullying behaviour. Our findings chime with previous research indicating that the role of bystanders is important (Wiens and Dempsey 2009; Quirk and Campbell 2015; O’Connell, Pepler, and Craig 1999) but also suggest that bystanders may be impor-tant in somewhat different ways for younger students compared with older students.

Further, while the severity of offline versus online aggression was unclear regarding the younger students (Viewpoint 2), the older students (Viewpoint 1) regarded aggressive behaviours taking place in an offline setting to be more often characterised as bullying compared with aggressive behaviours taking place online. This is interesting to note, as in terms of balance there is, unsurprisingly, an increase in effort and research focusing on bullying and victimisation taking place online (Kowalski et al. 2014), since many young people spend increasing amounts of time online. It is possible that a sense of the fear of the unknown may have resulted in an emphasis on combating online aggression, with a corresponding diminishing of attention devoted to offline aggression in recent years. While some students, especially the older ones, tend to have found strategies for handling bulling online such as ignoring, dismissing and keeping distance (Hellström, Persson, and Hagquist 2015), our study draws attention to the possibility that they still may need help with strategies for handling bullying that is taking place face-to-face in the classroom, in the school playground or in the corridors.

Another issue worthy of further investigation is the notion that the older students in the study seemed to assess repetition as a more important criterion for the definition of bullying compared with their younger peers. Earlier research has shown that younger children tend not to be repeatedly victimised over long periods of time, indicating that younger and older students may differ in including repetition as a part of their definition and understanding of what it means to be bullied. Hence, the stability of the victim role differs between younger and older students (Kochenderfer and Ladd 1997). Even if repetition is included as an important criterion in older students’ subjective viewpoints, it may not necessarily be functionally equivalent to adults’ understandings of where to draw the line (Jeffrey and Stuart

2019). An open dialogue between children and adults on this topic could contribute to more effective interventions by adults (Hopkins et al. 2013).

Across both viewpoints in the current study, it is noteworthy that social exclu-sion was ranked low in comparison with other bullying situations. This is in line with previous research which suggests that children, as well as adults, tend to perceive behaviours such as hitting, threatening and calling names as more severe compared with rumour-spreading and social exclusion (Maunder, Harrop, and Tattersall 2010; Skrzypiec et al. 2011). However, the findings are interesting, as previous research has established a strong relationship between relational forms of bullying and poor self-reported mental health (Chester et al. 2017). Traditionally, relational forms of bullying have been seen as a female form of bullying, stemming from socialising processes where girls have learned to use less aggression or to vent their aggression indirectly and where girls tend to engage in fewer and closer friendships compared with boys (Lagerspetz and Björkqvist 1994). However, a recent meta-analysis found no significant difference between boys and girls regarding relational victimisation (Casper and Card 2017). Given that relationships among students today typically take place on the internet, and if they have found strategies to handle bullying online, it is possible that relational bullying may not be experienced as severely as physical forms of bullying taking place offline (O’Brien and Moules 2010; O’Brien 2019).

Limitations and suggestions for further research

As noted above, generalising to the wider population is not intended, nor was it the goal of designing an exploratory study using Q methodology. Our study had a small and purposive participant sample from a one school; there may, of course, be many other explanations for the distinction of two viewpoints that are unrelated to age, particularly as the two age groups were relatively close to each other. Equally, it is possible that the ranking of online behaviour could be related to the degree of familiarity with the specific examples of social media, communication tools and online games included in the 23 item scenarios.

Nevertheless, our fine-grained analyses and identification of viewpoints offers a springboard for further, larger-scale research across schools and may also provide valuable and transferable insights for bullying prevention efforts in general. For example, the applied Q set in the current study could be used as the basis for a future research project involving a large number of schools and a wide range of age groups to investigate whether there may be an age-related progression from understanding bullying as a more physical act (Viewpoint 2) to predominantly verbal forms (Viewpoint 1). In addition, while a strength of the current study was the participatory way that the participants were included in the development and pilot-ing of the instruments, it is still the case that the study would have been enhanced if it had been possible to undertake interviews with at least some of them after the sorting procedure. This would have facilitated further analysis and allowed an enriched interpretation of the viewpoints because of the additional qualitative data that would have been produced.

Conclusions

The viewpoints that emerged within this small, exploratory analysis of bullying beha-viours would be worthy of further investigation with larger data sets. The findings draw attention to the need for adults to maintain a focus on students’ behaviours offline, as well as online: in this age of increasingly digital communication, it is easy for the offline context to be inadvertently overlooked. When it comes to younger students, anti-bullying efforts targeting bullying in private settings and acknowledging potential harm may be more suitable than anti-bullying efforts targeting stigma and shame, which may, in turn, better support the needs of older students in a more precise way. The study also shines a light on the importance of using participatory methodologies that allow students to express their own perspectives rather than working with adult-imposed categories. It is our hope that the research reported here can play a part in assisting others internationally in further understanding bullying behaviours from students’ perspectives and supporting the development of anti-bullying strategies, ultimately improving student wellbeing.

Disclosure statement

ORCID

Lisa Hellström http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9326-1175

Adrian Lundberg http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8555-6398

References

Bergold, J., and S. Thomas. 2012. “Participatory Research Methods: A Methodological Approach in Motion.” Historical Social Research/Historische Sozialforschung 37 (4): 191–222.

Berne, S., A. Frisén, and J. Berne. 2019. “Cyberbullying in Childhood and Adolescence: Assessment, Negative Consequences and Prevention Strategies.” In Policing Schools: School Violence and the Juridification of Youth, edited by J. Lunneblad, 141–152. Cham: Springer.

Björkqvist, K., and K. Österman. 2018. “Sex Differences in Physical, Verbal, and Indirect Aggression: A Review of Recent Research.” Sex Roles 30 (3/4): 177–188. doi:10.1007/BF01420988.

Boulton, M., and D. Hawker. 1997. “Verbal Bullying: The Myth of “Sticks and Stones.”.” In Bullying: Home, School, Community, edited by D. Tattum and G. Herbert, 53–63. London: David Fulton Publishers.

Brown, S. R., and J. M. M. Good. 2010. “Q Methodology.” In Encyclopedia of Research Design, edited by N. J. Salkind, 1149–1155. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Byrne, H., B. Dooley, A. Fitzgerald, and L. Dolphin. 2016. “Adolescents’ Definitions of Bullying: The Contribution of Age, Gender, and Experience of Bullying.” European Journal of Psychology of Education 31 (3): 403–418. doi:10.1007/s10212-015-0271-8.

Camodeca, M., S. C. S. Caravita, and G. Coppola. 2015. “Bullying in Preschool: The Associations between Participant Roles, Social Competence, and Social Preference.” Aggressive Behavior 41 (4): 310–321. doi:10.1002/ab.21541.

Camodeca, M., and G. Coppola. 2016. “Bullying, Empathic Concern, and Internalization of Rules among Preschool Children: The Role of Emotion Understanding.” International Journal of Behavioral Development 40 (5): 459–465. doi:10.1177/0165025415607086.

Campbell, M., and S. Bauman. 2018. “Cyberbullying: Definition, Consequences, Prevalence.” In Reducing Cyberbullying in Schools, edited by M. Campbell and S. Bauman, 3–16. London: Academic Press.

Canty, J., M. Stubbe, D. Steers, and S. Collings. 2016. “The Trouble with Bullying–Deconstructing the Conventional Definition of Bullying for a Child-centred Investigation into Children’s Use of Social Media.” Children & Society 30 (1): 48–58. doi:10.1111/chso.12103.

Casper, D. M., and N. A. Card. 2017. “Overt and Relational Victimization: A Meta-analytic Review of Their Overlap and Associations with Social–psychological Adjustment.” Child Development 88 (2): 466–483. doi:10.1111/cdev.12621.

Chester, K. L., N. H. Spencer, L. Whiting, and F. M. Brooks. 2017. “Association between Experiencing Relational Bullying and Adolescent Health-related Quality of Life.” Journal of School Health 87 (11): 865–872. doi:10.1111/josh.12558.

Cornell, D., P. L. Sheras, and J. C. M. Cole. 2006. “Assessment of Bullying.” In Handbook of School Violence and School Safety: Frpm Research to Practice, edited by S. R. Jimerson and M. J. Furlong, 191–210. Mahwah: Erlbaum.

Craig, W. M., D. Pepler, and R. Atlas. 2000. “Observations of Bullying in the Playground and in the Classroom.” School Psychology International 21 (1): 22–36. doi:10.1177/0143034300211002. Cross, D., L. Lester, and A. Barnes. 2015. “A Longitudinal Study of the Social and Emotional Predictors

and Consequences of Cyber and Traditional Bullying Victimisation.” International Journal of Public Health 60 (2): 207–217. doi:10.1007/s00038-015-0655-1.

de Leeuw, R. R., A. A. de Boer, E. J. Beckmann, J. van Exel, and A. E. M. G. Minnaert. 2019. “Young Children’s Perspectives on Resolving Social Exclusion within Inclusive Classrooms.” International Journal of Educational Research 98: 324–335. doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2019.09.009.

Dooley, J. J., J. Pyżalski, and D. Cross. 2009. “Cyberbullying versus Face-to-face Bullying: A Theoretical and Conceptual Review.” Zeitschrift Für Psychologie/Journal of Psychology 217 (4): 182–188. doi:10.1027/0044-3409.217.4.182.

Duncan, N., and L. Owens. 2011. “Bullying, Social Power and Heteronormativity: Girls’ Constructions of Popularity.” Children & Society 25 (4): 306–316. doi:10.1111/j.1099-0860.2011.00378.x.

Ellingsen, I. T., A. Arstad Thorsen, and I. Størksen. 2014. “Revealing Children’s Experiences and Emotions through Q Methodology.” Child Development Research 2014: 1–9. doi:10.1155/2014/ 910529.

Ellingsen, I. T., I. Størksen, and P. Stephens. 2010. “Q Methodology in Social Work Research.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 13 (5): 395–409. doi:10.1080/ 13645570903368286.

Englander, E., E. Donnerstein, R. Kowalski, C. A. Lin, and K. Parti. 2017. “Defining Cyberbullying.” Pediatrics 140 (Supplement 2): S148–S51. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-1758U.

Eriksen, I. M. 2018. “The Power of the Word: Students’ and School Staff’s Use of the Established Bullying Definition.” Educational Research 60 (2): 157–170. doi:10.1080/ 00131881.2018.1454263.

Finkelhor, D., H. A. Turner, and S. Hamby. 2012. “Let’s Prevent Peer Victimization, Not Just Bullying.” Child Abuse & Neglect 36 (4): 271–274. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.12.001.

Frisén, A., K. Holmqvist, and D. Oscarsson. 2008. “13-year-olds’ Perception of Bullying: Definitions, Reasons for Victimisation and Experience of Adults’ Response.” Educational Studies 34 (2): 105–117. doi:10.1080/03055690701811149.

Gamliel, T., J. H. Hoover, D. W. Daughtry, and C. M. Imbra. 2003. “A Qualitative Investigation of Bullying: The Perspectives of Fifth, Sixth and Seventh Graders in A USA Parochial School.” School Psychology International 24 (4): 405–420. doi:10.1177/01430343030244004.

Gladden, R. M., A. M. Vivolo-Kantor, M. E. Hamburger, and C. D. Lumpkin 2014. “Bullying Surveillance among Youths: Uniform Definitions for Public Health and Recommended Data Elements.” Version 1.0.” Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and US Department of Education.

Green, J. G., E. D. Felix, J. D. Sharkey, M. J. Furlong, and J. E. Kras. 2013. “Identifying Bully Victims: Definitional versus Behavioral Approaches.” Psychological Assessment 25 (2): 651–657. doi:10.1037/a0031248.

Gropper, N., and M. Froschl. 2000. “The Role of Gender in Young Children’s Teasing and Bullying Behavior.” Equity and Excellance in Education 33 (1): 48–56. doi:10.1080/1066568000330108. Guerin, S., and E. Hennessy. 2002. “Pupils’ Definitions of Bullying.” European Journal of Psychology of

Education 17 (3): 249–261. doi:10.1348/000709905X52229.

Hellström, L., L. Persson, and C. Hagquist. 2015. “Understanding and Defining Bullying–adolescents’ Own Views.” Archives of Public Health 73 (1): 4. doi:10.1186/2049-3258-73-4.

Holt, M. K., J. Greif Green, G. Reid, A. DiMeo, D. L. Espelage, E. D. Felix, M. J. Furlong, V. P. Poteat, and J. D. Sharkey. 2014. “Associations between past Bullying Experiences and Psychosocial and Academic Functioning among College Students.” Ournal of American College Health 62 (8): 552–560. doi:10.1080/07448481.2014.947990.

Hopkins, L., L. Taylor, E. Bowen, and C. Wood. 2013. “A Qualitative Study Investigating Adolescents’ Understanding of Aggression, Bullying and Violence.” Children and Youth Services Review 35 (4): 685–693. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.01.012.

Hwang, S., Y. S. Kim, Y. J. Koh, and B. L. Leventhal. 2018. “Autism Spectrum Disorder and School Bullying: Who Is the Victim? Who Is the Perpetrator?” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 48 (1): 225–238. doi:10.1007/s10803-017-3285-z.

Jeffrey, J., and J. Stuart. 2019. “Do Research Definitions of Bullying Capture the Experiences and Understandings of Young People? A Qualitative Investigation into the Characteristics of Bullying Behaviour.” International Journal of Bullying Prevention 1–10. doi:10.1007/s42380-019- 00026-6.

Kochenderfer, B. J., and G. W. Ladd. 1997. “Victimized Children’s Responses to Peers’ Aggression: Behaviors Associated with Reduced versus Continued Victimization.” Development and Psychopathology 9 (1): 59–73. doi:10.1017/S0954579497001065.

Kowalski, R. M., G. W. Giumetti, A. N. Schroeder, and M. R. Lattanner. 2014. “Bullying in the Digital Age: A Critical Review and Meta-analysis of Cyberbullying Research among Youth.” Psychological Bulletin 140 (4): 1073–1137. doi:10.1037/a0035618.

Lagerspetz, K. M. J., and K. Björkqvist. 1994. “Indirect Aggression in Boys and Girls.” In Aggressive Behavior. The Plenum Series in Social/Clinical Psychology., edited by L. R. Huesmann, 131–150. Boston, MA: Springer.

Liu, M. C.C., Lan, J.-W. Hsu, K.-L. Huang, and Y.-S. Chen. 2014. “Bullying Victimization and Conduct Problems among High School Students in Taiwan: Focus on Fluid Intelligence, Mood Symptoms and Associated Psychosocial Adjustment.” Children and Youth Services Review 47 (3): 231–238. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.09.011.

Madsen, K. C. 1996. “Differing Perceptions of Bullying and Their Practical Implications.” Educational and Child Psychology 13 (2): 14–22.

Maunder, R. E., A. Harrop, and A. J. Tattersall. 2010. “Pupil and Staff Perceptions of Bullying in Secondary Schools: Comparing Behavioural Definitions and Their Perceived Seriousness.” Educational Research 52 (3): 263–282. doi:10.1080/00131881.2010.504062.

Menesini, E., and A. Nocentini. 2009. “Cyberbullying Definition and Measurement: Some Critical Considerations.” Zeitschrift Für Psychologie/Journal of Psychology 217 (4): 230–232. doi:10.1027/ 0044-3409.217.4.230.

Menesini, E., A. Nocentini, B. E. Palladino, A. Frisén, S. Berne, R. Ortega-Ruiz, J. Calmaestra, H. Scheithauer, A. Schultze-Krumbholz, and P. Luik. 2012. “Cyberbullying Definition among Adolescents: A Comparison across Six European Countries.” Cyberpsychology, Behavior, Social Networking 15 (9): 455–463. doi:10.1089/cyber.2012.0040.

Monks, C. P., and P. K. Smith. 2006. “Definitions of Bullying: Age Differences in Understanding of the Term, and the Role of Experience.” British Journal of Developmental Psychology 24 (4): 801–821. doi:10.1348/026151005X82352.

Moreno, M. A., N. Suthamjariya, and E. Selkie. 2018. “Stakeholder Perceptions of Cyberbullying Cases: Application of the Uniform Definition of Bullying.” Journal of Adolescent Health 62 (4): 444–449. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.11.289.

Naylor, P., H. Cowie, F. Cossin, R. de Bettencourt, and F. Lemme. 2006. “Teachers’ and Pupils’ Definitions of Bullying.” British Journal of Educational Psychology 76 (3): 553–576. doi:10.1348/ 000709905X52229.

Nocentini, A., J. Calmaestra, A. Schultze-Krumbholz, H. Scheithauer, R. Ortega, and E. Menesini. 2010. “Cyberbullying: Labels, Behaviours and Definition in Three European Countries.” Australian Journal of Guidance and Counselling 20 (2): 129–142. doi:10.1375/ajgc.20.2.129.

O’Brien, N. 2019. “Understanding Alternative Bullying Perspectives through Research Engagement with Young People.” Frontiers in Psychology 10. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01984.

O’Brien, N., and T. Moules. 2010. “The Impact of Cyber-bullying on Young People’s Mental Health: Final Report.” In. Chelmsford: Anglia Ruskin University.

O’Connell, P., D. Pepler, and W. Craig. 1999. “Peer Involvement in Bullying: Insights and Challenges for Intervention.” Journal of Adolescence 22 (4): 437–452. doi:10.1006/jado.1999.0238.

Olweus, D. 1978. Aggression in the Schools: Bullies and Whipping Boys. Oxford, England: Hemisphere. Olweus, D. 2009. “Understanding and Researching Bullying.” In Handbook of Bullying in School - an

International Perspective, edited by S. M. Swearer, D. L. Espelage, and S. R. Jimerson, 9–34. New York, NY: Routlege.

Olweus, D. 2017. “Cyberbullying: A Critical Overview. .” In Aggression and Violence: A Social Psychological Perspective, edited by B. J. Bushman, 225–240. New York, NY: Routledge.

Owens, L. 2016. “The Use of Q Sort Methodology in Research with Teenagers.” In Pratical Research with Children, edited by P. Herwegen and J. V. Jess, 228–245, ProQuest Ebook Central, London & New York: Routledge.

Owens, L., and N. Duncan. 2009. “Druggies” and “Barbie Dolls”: Popularity among Teenage Girls in Two South Australian Schools.” Journal of Human Subjectivity 7 (2): 39–63.

Owens, L., H. Feng, and J. Xi. 2014. “Popularity among Teenage Girls in Adelaide and Shanghai: A Pilot Q-Method Study.” Open Journal of Social Sciences 2 (5): 80–85. doi:10.4236/jss.2014.25016.

Patchin, J. W., and S. Hinduja. 2015. “Measuring Cyberbullying: Implications for Research.” Aggression and Violent Behavior 23: 69–74. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2015.05.013.

Patchin, J. W., and S. J. Hinduja. 2006. “Bullies Move beyond the Schoolyard: A Preliminary Look at Cyberbullying.” Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice 4 (2): 148–169. doi:10.1177/ 1541204006286288.

Quirk, R., and M. Campbell. 2015. “On Standby? A Comparison of Online and Offline Witnesses to Bullying and Their Bystander Behaviour.” Educational Psychology 35 (4): 430–448. doi:10.1080/ 01443410.2014.893556.

Rigby, K. 2006a. “Towards a Definition of Bullying.” In New Perspectives on Bullying, edited by K. Rigby, 27–51. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Rigby, K. 2006b. “What International Research Tells Us about Bullying.” In Bullying Solutions: Evidence-based Approaches to Bullying in Australian Schools., edited by H. McGrath and T. Noble, 3–15. Crowat Nest, NSW: Pearson Education.

Rigby, K., and P. K. Smith. 2011. “Is School Bullying Really on the Rise?” Social Psychology of Education 14 (4): 441–455. doi:10.1007/s11218-011-9158-y.

Salmivalli, C., and A. Kaukiainen. 2004. ““Female Aggression” Revisited: Variable-and Person-cen-tered Approaches to Studying Gender Differences in Different Types of Aggression.” Aggressive Behavior 30 (2): 158–163. doi:10.1002/ab.20012.

Sargeant, J., and J. K. Gillett-Swan. 2019. “Voice-Inclusive Practice (VIP): A Charter for Authentic Student Engagement.” The International Journal of Children’s Rights 27 (1): 122–139. doi:10.1163/ 15718182-02701002.

Skrzypiec, G., P. Slee, R. Murray-Harvey, and B. Pereira. 2011. “School Bullying by One or More Ways: Does It Matter and How Do Students Cope?” School Psychology International 32 (3): 288–311. doi:10.1177/0143034311402308.

Slonje, R., and P. K. Smith. 2008. “Cyberbullying: Another Main Type of Bullying?” Scandinavian Journal of Psychology 49 (2): 147–154. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9450.2007.00611.x.

Smith, P. K., H. Cowie, R. F. Olafsson, and A. P. D. Liefooghe. 2002. “Definitions of Bullying: A Comparison of Terms Used, and Age and Gender Differences, in A Fourteen–Country International Comparison.” Child Development 73 (4): 1119–1133. doi:10.1111/1467- 8624.00461.

Smith, P. K., and R. Slonje. 2010. “Cyberbullying: The Nature and Extent of a New Kind of Bullying, in and Out of School.” In The International Handbook of School Bullying, edited by S. Jimerson, S. Swearer, and D. Espelage, 249–262. New York: Routledge.

Solberg, M. E., and D. Olweus. 2003. “Prevalence Estimation of School Bullying with the Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire.” Aggressive Behavior 29 (3): 239–268. doi:10.1002/ab.10047.

Sticca, F., and S. Perren. 2012. “Is Cyberbullying Worse than Traditional Bullying? Examining the Differential Roles of Medium, Publicity, and Anonymity for the Perceived Severity of Bullying.” Journal of Youth Adolescence 42 (5): 739–750. doi:10.1007/s10964-012-9867-3.

Schmolck, P.. 2014. PQMethod. Release 2.35. Retrieved from http://schmolck.userweb.mwn.de/ qmethod/downpqmac.htm.

Thomas, H. J., J. P. Connor, C. M. Baguley, and J. G. Scott. 2017. “Two Sides to the Story: Adolescent and Parent Views on Harmful Intention in Defining School Bullying.” Aggressive Behavior 43 (4): 352–363. doi:10.1002/ab.21694.

Thornberg, R., and H. Delby. 2019. “How Do Secondary School Students Explain Bullying?” Educational Research 61 (2): 142–160. doi:10.1080/00131881.2019.1600376.

Thornberg, R., and S. Knutsen. 2011. “Teenagers’ Explanations of Bullying.” Child & Youth Care Forum 40 (3): 177–192. doi:10.1007/s10566-010-9129-z.

Vaillancourt, T., P. McDougall, S. Hymel, A. Krygsman, J. Miller, K. Stiver, and C. Davis. 2008. “Bullying: Are Researchers and Children/youth Talking about the Same Thing?” International Journal of Behavioral Development 32 (6): 486–495. doi:10.1177/0165025408095553.

Van der Wal, M. F., C. A. M. De Wit, and R. A. Hirasing. 2003. “Psychosocial Health among Young Victims and Offenders of Direct and Indirect Bullying.” Pediatrics 111 (6): 1312–1317. doi:10.1542/ peds.111.6.1312.

Varjas, K., J. Meyers, L. Bellmoff, E. Lopp, L. Birckbichler, and M. Marshall. 2008. “Missing Voices: Fourth through Eighth Grade Urban Students’ Perceptions of Bullying.” Journal of School Violence 7 (4): 97–118. doi:10.1080/15388220801973912.

Wang, J., R. J. Iannotti, and T. R. Nansel. 2009. “School Bullying among Adolescents in the United States: Physical, Verbal, Relational, and Cyber.” Journal of Adolescent Health 45 (4): 368–375. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.03.021.

Watts, S., and P. Stenner. 2012. Doing Q Methodological Research: Theory, Method and Interpretation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Wiens, B. A., and A. Dempsey. 2009. “Bystander Involvement in Peer Victimization: The Value of Looking beyond Aggressors and Victims.” Journal of School Violence 8 (3): 206–215. doi:10.1080/ 15388220902910599.

Ybarra, M. L., D. L. Espelage, A. Valido, J. S. Hong, and T. L. Prescott. 2018. “Perceptions of Middle School Youth about School Bullying.” Journal of Adolescence 75: 175–187. doi:10.1016/j. adolescence.2018.10.008.

Younan, B. 2019. “A Systematic Review of Bullying Definitions: How Definition and Format Affect Study Outcome.” Journal of Aggression, Conflict and Peace Research 11 (2): 109–115. doi:10.1108/ JACPR-02-2018-0347.