1

How do we experience parks?

Social benefits of ecosystem services with anincreased connectivity of sub-urban parks.

Master Thesis for Sustainable Urban Management (SASUM)

BY602E Spring semester 2015

Authors:

Hildur Hreinsdóttir

Lea Meyer zu Bentrup

Tutor:

Ebba Lisberg Jensen

Abstract:

Our motivation for this research is the interest we have for positive influences of green areas on people's well-being and social improvement. We see nature, the ecosystems and its services, integrated with humans as a whole, making our lives physically and mentally more sustainable. Therefore the purpose of this study is to investigate the social benefits of selected ecosystem services in sub-urban parks in Malmö City, and to explore how the respected services can be enhanced with a greater connectivity of the parks. A survey and interviews were used to collect information about people's preferences and values about nature parks and their opinion on possible connectivity of three sub-urban parks in Malmö, Sweden. The results show that people are overall positive with the recreational and aesthetic values of parks but show less appreciation for the parks as pure nature represents. Connectivity is not clearly understood by the participants but seems to be positively accepted. To give an idea on how Malmö could improve urban biodiversity and facilitate enjoyable nature experiences we give some practical suggestions for a green corridor.

Acknowledgements

First of all we would like give special thanks to Annika Kruuse, at Miljöförvaltningen (Malmö stad), for providing us with additional information; to Arne Mattsson, at Gatukontoret (Street- and Park Division), for sharing his time with us to make the interview. We also would like to thank our friends and acquaintances who shared and commented on our survey. Finally, we would like to thank our family for being with us, their patience and encouragement along the journey of this thesis.

2

Table of Contents

1 - Introduction ... 4

1.1. Malmö as the city of parks ... 4

1.2. Ecosystem services and challenges with urban expansion ... 4

1.3. The importance of urban green areas ... 5

1.4. Aim and research questions ... 7

1.5. Structure ... 7

2 –The Role of Biodiversity, Ecosystem Services and Connectivity. ... 8

2.1. Ecosystem services... 8

2.1.1. Ecological side of ecosystem services ... 10

2.1.2. Social side of ecosystem services ... 10

2.2. Green areas and connectivity ... 12

2.2.1. The social benefits of connecting green areas ... 13

3 - The Cases ... 14

3.1. Bulltofta park ... 15

3.2. Husie Mosse ... 16

3.3. Remonthagen/ Jägersro ... 17

3.4. Ecosystem services in the parks... 18

4 - Epistemological Considerations and Methods ... 20

4.1. Park as process ... 20 4.2. Methods ... 20 4.2.1 Documents ... 21 4.2.2 Field observations ... 22 4.2.3 The survey ... 23 4.2.4 Interviews ... 24 4.2.5 Analysis methods ... 24

4.2.6 Validity and reliability ... 25

5 – Analysis ... 26

5.1. Social benefits of the cultural/ recreational ecosystem Services ... 26

5.2. SWOT analysis of each park ... 30

Bulltofta park: ... 30

Husie Mosse: ... 31

Remonthagen: ... 33

5.3. SWOT Analyze of the connectivity between the parks: ... 35

6 – Concluding Discussion ... 39 6.1. Practical suggestions ... 40 6.2. Further research ... 41 References: ... 42 Appendix 1 ... 45 Appendix 2 ... 49

3

Table of Figures

Figure 1: Model of Ecosystem services (text from Ernstons 2013; Icons from C/O City

2014)... 9

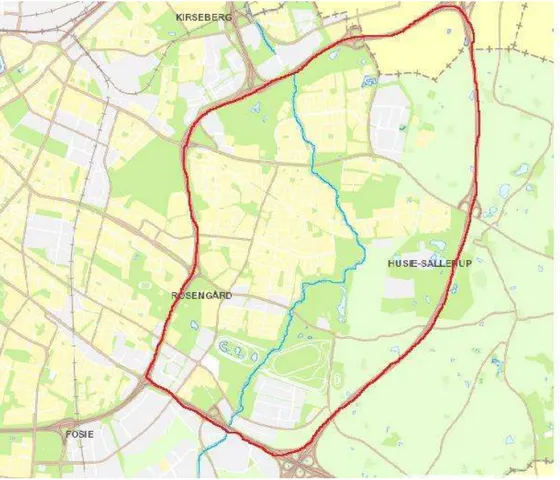

Figure 2: Map of the study area ...14

Figure 3: Map of Bulltofta park...15

Figure 4: Maintained path and a view to the forest in Bulltofta park...15

Figure 5: Sand slopes and pine trees...16

Figure 6: Sign with information on the lizards in Husie Mosse ... 16

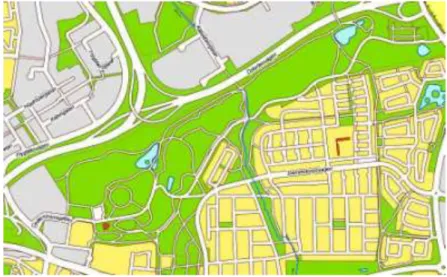

Figure 7: Map of b) Husie Mosse and c)Remonthagen/ Jägersro ...17

Figure 8: Riseberga stream in Remonthagen/ Jägersro ...17

Figure 9: Playground in Remonthagen/ Jägersro ... 17

Figure 10: Riseberga stream in Bulltofta park...18

Figure 11: The interactive maps on www.malmo.se show various aspects like bicycle paths, nature reservoirs and Husie Mosse and Bulltofta as good spaces to watch birds (Red spots)... 22

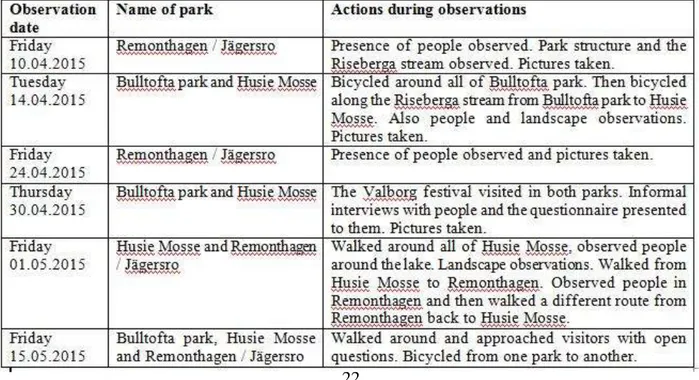

Figure 12: Observation schedule... 21

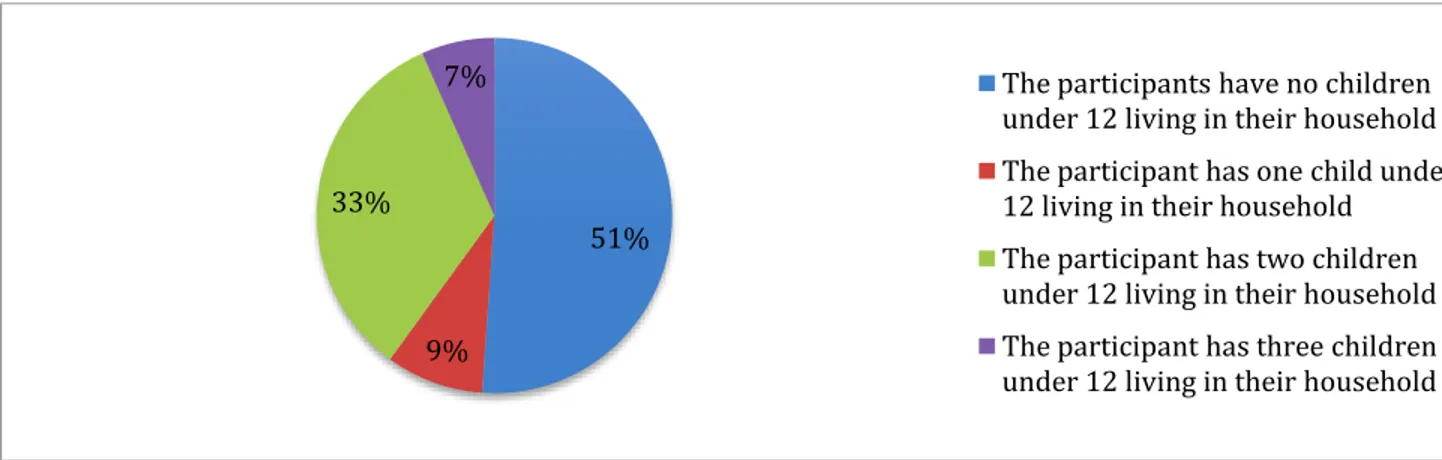

Figure 13: The graph shows the portion of people having one to three children under 12 living in their household...26

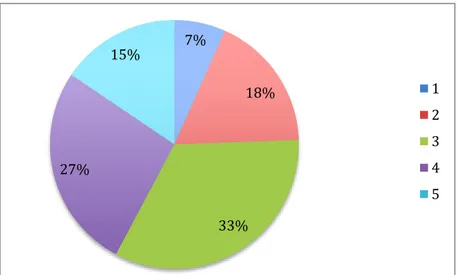

Figure 14: The graph shows the portion of people valuing dense spaces from 1 to 5... 27

Figure 15: The graph shows the level of appreciation of the park as a historical place... 27

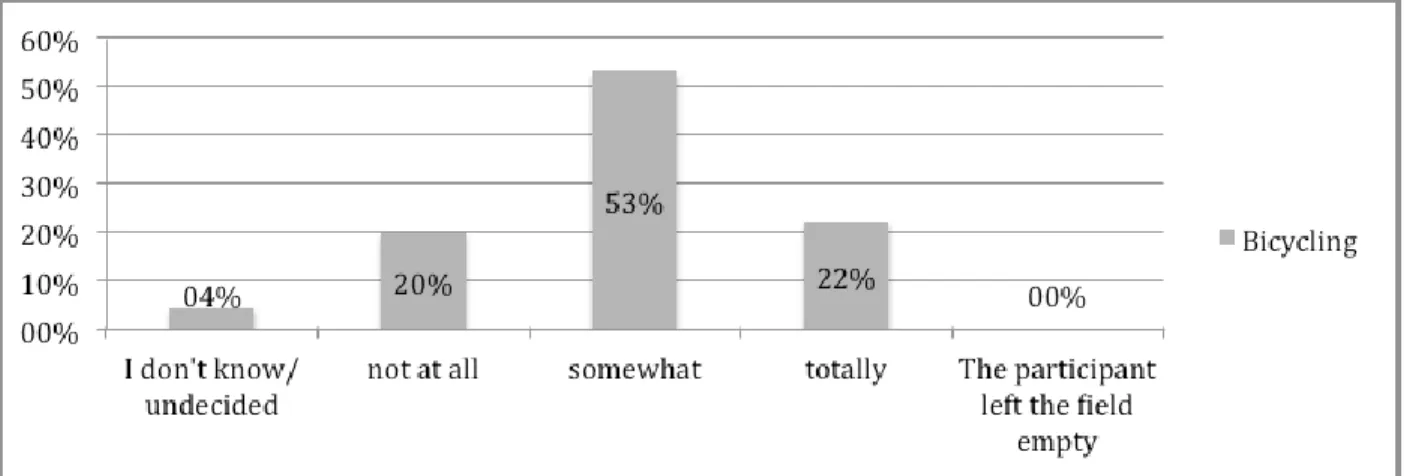

Figure 16: The graph shows the level of appreciation of bicycling... 28

Figure 17: The graph shows the importance of the variety of species for the participants... 29

Figure 18: Picture showing the mole mounds at Bulltofta park... 29

Figure 19: Running path with softer soil in Bulltofta park ...29

Figure 20: SWOT of Bulltofta park... 31

Figure 21: Attractive nature of Husie Mosse ...30

Figure 22: Wild growth and unclear paths in Husie Mosse...31

Figure 23: Diverse landscape in Husie Mosse - lake, forest, sand dunes ...31

Figure 24: Husie Mosse – a view from the south to the unmaintained northern part ...31

Figure 25: Sign near the shooting practice area of the military in Husie Mosse ...32

Figure 26: SWOT Husie Mosse... 33

Figure 27: The graph shows the percentage of people, who know Remonthagen park...34

Figure 28: SWOT of Remonthagen/Jägersro... 35

Figure 29: Difficult crossing over Amiralsgatan road between Husie Mosse and Remonthagen park...34

Figure 30: The graph shows the percentage of people who think a connection between the parks would matter to them...37

Figure 31: Last statement of the question about connectivity compared with place of residence...37

Figure 32: SWOT of the connectivity of Bulltofta park, Husie Mosse and Remonthagen park ...38

Figure 33: Green features...39

Figure 34: Green signs...39

Figure 35: Informative sign...39

Figure 36: Informative sign...39

4

1 - Introduction

To ensure good living conditions for ourselves and our future generations we need green areas around us and we need the ecosystems that develop in these green areas. People living in urban areas feel a special need to escape the city and its stress and enter into a more silent and lush surrounding. Some will use the green areas for physical activities and enjoyment while others just want to enjoy the peace and relaxing environment. The ecosystems in the green areas provide different services to us humans but, which services are more important than others? In order for urban planning to be effective and make sense there needs to be an assessment of how the green areas are working for people and if there are areas which are functioning better than others in terms of the ecosystem services.

1.1. Malmö as the city of parks

Malmö, a city of just over 300.000 people, is called ‘The city of parks’ – “Parkernas stad” in Swedish because of numerous beautiful parks of all sizes. This third largest city in Sweden has been praised for its concentration on sustainable urban development, renewable energy solutions and abundance of green space. From old parks with the oldest trees in town to the most modern parks with themed playgrounds, Malmö has many parks with different characters. Some are action filled, some are family oriented, some are concentrated on biodiversity and others are seen as enjoyable oasis, where one would go to find serenity and escape from the hectic city life. Already in the nineteenth century and early in the twentieth century spacious and beautiful parks were created and since the 1970´s Malmö has been transforming steadily from an industrial center point to the “future’s ecological city” (Broström et al. 2008, p. 120). Before the 19th century, public parks were unknown in Swedish towns (Pehrsson 1986) except outside the town borders and in Malmö only lined trees around the central square were to be found. Moreover, Malmö has always lacked the bordering nature as Scanian landscape is in principle an agricultural landscape and with the growth of the city the natural landscape was drained in increasing production and industrialism. Finally, in the beginning of 1980 the dream of a forest and nature park was fulfilled with the creation of Bulltofta park in the eastern part of Malmö. Shortly after the Husie Mosse park, nearby, was also created and in the 90’s the Remonthagen park. All located in East Malmö, these three parks are now the focus point of this study.

1.2. Ecosystem services and challenges with urban expansion

Challenges in our urban environment are many and diverse and reaching for sustainable urban development is a process where these challenges are met and change is made. Among the biggest environmental challenges urban society faces is traffic congestion, noise, air pollution and loss of biodiversity. Many people and politicians put their absolute faith in the future technology to solve all of earth´s problems, but there are some things that technology cannot replace. The natural ecosystems in our environment provide valuable services, called ecosystem services (ES), which are being consumed and taken advantage of by cities and their dwellers. But what exactly are these ecosystem services and how are they being exploited and consumed? The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment – MEA (2005) defines the ES as “benefits that people receive from the ecosystems they are surrounded by” (p.1). It has been recognized by many (e.g. Haines-Young and Potschin 2010; Newman and Jennings 2008 and Gómez-Baggethun and

5

Barton 2013) that in order for the city to fully function, the ES are necessary and the degradation of ES, caused by growing cities, increased population and urban sprawl, decreases the outcome of the ES as well as the biodiversity and the reproduction of species. Excessive consumption of resources has led to societies experiencing most degradation of the regulating and supporting services, which is a phenomenon called ‘The Tragedy of Ecosystem Services’ (MEA, 2005). Even some parts of the cultural and provisioning services are suffering too. The ecosystem services are direct as well as indirect services correlated with the natural capital, meaning that the ecosystem services and their benefits are provided by the natural capital. Sub-urban areas are providing more natural capital due to the fact that this is more available in sub-urban areas, as e.g. within country sides or forests. Therefore it is important to differentiate the ecosystems and ecosystem services provided in low-density sub-urban areas and the ones in high-density urban areas. Ecosystems within the city center or high-density urban areas have pressure on them as the city occupies these places. This pressure is extending with growing cities more and more towards the low-density sub-urban areas. According to Newman and Jennings (2008) cities can help to release the pressure of ecosystems in low-density sub-urban areas by creating new ecosystems within the city.

As we mentioned earlier some parts of the cultural ecosystem services are suffering as well as the ecological ones. Malmö is lacking nature areas and it is among the most impervious cities in Sweden with only 33 m2 per inhabitant of green space while Sweden´s other large cities have an average of 100 m2 (Malmö stad 2003). This means that the city has fallen behind other major Swedish cities in terms of green space within the city but the ‘Green plan’ (Grönplan) of Malmö (2003) did present these concerns and suggested that green areas should be given greater prominence in the future. They also contemplated on whether the parks as they are today really fulfill the needs of the residents. Sustainability is based on the three pillars of economic, social and environmental sustainability. Social sustainability focuses on equitable, diverse, connected and democratic quality of life (McKenzie, 2004). In order to reach sustainability keeping the balance between at least two of these pillars is essential and regarding the parks, a balance between social and environmental sustainability is desired. Furthermore we have to become the custodians of nature to contribute to the wider circle of life (Newman & Jennings 2008) and “instead of using nature as a mere tool for human purposes we can strive to become tools of nature who serve its agenda too” (Newman & Jennings 2008, p. 122, citing McDonough and Braungart 2002). According to Rudd et al. (2002) the fragments of ecosystems remaining in cities are more important than their limited size due to reduction of green space in urban areas. Therefore reconnecting the city residents with land and one another is a part of our sustainable urban lifestyle where cities should be “recognized again as place-bound embedded in ecosystems and bioregions” (Newman & Jennings 2008, p. 150).

1.3. The importance of urban green areas

Research has shown the importance of urban green areas for the quality of urban life (Breuste et al. 2013; Burgess et al. 1988 & Chiesura 2004) and to sustain long-term conditions for health, social relations and other aspects of human well-being (Gómez-Baggethun & Barton 2013). Ecosystem services have an influence on the human well-being (Summers et al. 2012; Kronenberg 2012; Tzoulas et al. 2007) and the benefits provided by ecosystem services can be of material or nonmaterial matter, improving physical and mental well-being. However, there are different ideas about the composition of the human well-being (e.g. Kronenberg 2012; Summers

6

et al. 2012, & Tzoulas et al. 2007) and what kind of needs can be accomplished with the help of the ES.

We, as humans, are integrated with the ecosystem, which sustains our lives physically and psychologically. But humans have also the ability to change the habitat of other species in a drastic way, damaging the ecosystems (Newman & Jennings, 2008). This is especially evident in cities where the urban sprawl and continuous development of the city decreases the natural surroundings of the city and the green areas that citizens have access to. Furthermore, all of the city’s operations place heavy burdens on the environment and the ecosystems that they occupy, and the degradation of ecosystems can cause significant harm to human well-being (Newman & Jennings 2008). With the increasing urban concentration people might lose appreciation to nature as well as awareness of the benefits of nature. This is evident even in urban societies with a substantive biodiversity present (Turner, Nakamura & Dinetti 2004). We are clearly not well aware of the important role the biodiversity plays in our lives and how it forms the basis of our existence. Many ecosystem services are highly undervalued because of lack of knowledge on how to put economic value on them and that means that often these services are excluded during policy making and decision making. Therefore it is always harder and harder to argue for the protection of these ecosystem services or why they need to be protected from further exploitation if no valuation work has been done (Malmö stad 2014a). Newman and Jennings claim that people will not understand the value of nature unless they have a direct experience with nature. The direct experience will also help people “gain a better appreciation of the importance of healthy habitats and ecosystems” (p. 64).

Newman and Jennings (2008) explain that the city can contribute to biodiversity by providing places for it to flourish and evolve, building connections between “city dwellers and the living world” and “creating the opportunity for daily interaction with the living world through e.g. parks” (p. 69). In our opinion it is not just about creating and maintaining parks as such, it is even more important to have parks that resemble the untouched nature as much as possible. A better and broader connection between natural green areas, the so-called green corridors are also vital. As cities continue to grow and growing population places more demand for land it becomes harder to preserve large green spaces, but city authorities must not forget that the larger the green area, the higher biodiversity it keeps which “provides important breeding and seeding habitats for interior species as well as edge species and transients” (Rudd et al. 2002, p. 373). A connection between these large green areas is important because with the size and closeness of each other the interaction between them grows and the species they foster multiply (Rudd et al. 2002). Such green corridors with increased biodiversity will improve the quality of life for city residents according to Rudd et al. (2012, citing Adams & Dove 1989), for example with “opportunities for wildlife viewing, human relaxation and education, and [by] controlling pollution, temperature and climate, erosion and noise” (Rudd et al. 2012, p. 373, citing Adams & Dove 1989). These are all part of the Ecosystem services important for human well-being. However, while it can contribute to the protection of wildlife, one should be careful not to interpret the importance of green corridors as the overall solution to wildlife conservation problems (Linehan et al. 1995).

Keeping and managing a healthy habitat for urban wildlife while at the same time providing recreational, aesthetic and other human ecosystem benefits is a big challenge and there is lack of understanding how social and ecological systems interrelate. There can be different interests and also possible conflicts between urban planning and urban dwelling in regards to which Ecosystem services are perceived most important and vital (Hansen & Pauleit 2014; Voigt

7

et al. 2014). The possibilities of viewing wildlife is an important part of outdoor recreation but keeping the balance between parks that include more nature and wildlife and managing them with recreational facilities is a difficult task. Therefore we need a better understanding of the conflicts and compatibilities between these two so that they may coexist without problems (Linehan et al. 1995, citing Strutin 1991).

1.4. Aim and research questions

The aim of this research is to study the social benefits of selected ecosystem services in sub-urban parks in Malmö City, and to explore how the respected services can be enhanced with a greater connectivity of the parks.

To facilitate the achievement of the purpose we have formulated the following research questions:

a. In what ways could the parks benefit individually from increased connection?

b. What kind of social benefits would an enhanced connection of all three parks bring for current and future users?

c. How do the residents of Malmö view the possible connectivity of the parks in question?

1.5. Structure

This paper is organized into six main chapters with subchapters. The first chapter provides detailed background information about the physical context of our study and about the ecosystem services. In the second chapter we present a framework for the principal concepts we are working with. Chapter three explains in more detail the settings for this study, the parks and their qualities. In a subsequent chapter our epistemological views are briefly reflected together with methods, which are arranged according to their weight and the reasons why those methods are chosen. In the fifth chapter data presentation is summarized and findings from the research and their analysis are presented. Lastly, conclusion of the study will be confined and discussed under chapter six, and there recommendations for further research will be given as well as practical suggestions.

8

2 – The Role of Biodiversity, Ecosystem Services and Connectivity.

The purpose of this chapter is to clarify some of the green area related concepts that we use in this paper and furthermore in our analysis, but in order to do so we must first make clear what we mean by a green area. A green area is defined by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) as “[a] land that is partly or completely covered with grass, trees, shrubs, or other vegetation. Green space includes parks, community gardens, and cemeteries” (United States Environmental Protection Agency 2014). The city of Malmö (‘Malmö stad’ from here on) has its own definition of green areas, which we will use primarily, since the purpose of this paper is to study the green areas in Malmö. Green areas defined by Malmo stad are “Everything green within urban limits, such as public parks and open lawns and other trees or grassy surfaces in the building leftover green areas (wasteland), villa gardens, green spaces between apartment buildings or industrial buildings and also green areas between roads is defined by Statistics Sweden as green space”1(Malmö Stad, Grönyta, Online). 2.1. Ecosystem services

Ecosystem services are defined by the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2005) as “benefits that people receive from the ecosystems they are surrounded by” (p.1). The ecosystem services are correlated with the natural capital, meaning that the ecosystem services and their benefits are provided by the natural capital. Sub-urban areas are providing more natural capital due to the fact that this is more available in sub-urban areas, as e.g. within country sides or forests. Therefore it is important to differentiate the ecosystems and ecosystem services provided in low-density sub-urban areas and the ones in high-density sub-urban areas.

Ecosystems within the city center or high-density urban areas have pressure on them as the city occupies these places. This pressure is extending with growing cities more and more towards the low-density sub-urban areas. According to Newman and Jennings (2008) cities can help to release the pressure on the ecosystems in low density sub-urban areas by creating more ecosystems within the city, and they suggest that the cities refer to themselves as “networked eco-villages embedded in their bioregions” (p. 68), which should develop strategies and a call for action to build and protect ecosystems and biodiversity in the city.

In order for cities to fully function, the ecosystem services are necessary (Haines-Young & Potschin 2010; Newman and Jennings 2008; Gómez-Baggethun & Barton 2013). Furthermore, the contribution of the biodiversity and the ecosystem services on social life has been recognized by e.g. Haines-Young & Potschin (2010). The degradation of ecosystems, because of growing cities, has negative influence on the ecosystem service outcome, e.g. the reproduction of species and biodiversity increase. Biodiversity is a very important factor for the ecosystems and the derived services or benefits for the humans (Haines-Young & Potschin 2010). In line with research, natural ecosystem services have functions, which are important to our society and these are equally determined by social values and perceptions as by ecological criteria. “Natural systems are thus a crucial source of non-material well-being and indispensable for a sustainable society” (deGroot et al. 2002, p. 11, citing Norton 1987).

1

Original text: “Allt grönt inom tätortsgränsen, såsom allmänna parker och öppna gräsytor samt andra träd- eller gräsbevuxna ytor, vid byggnation överblivna gröna ytor (impediment), villaträdgårdar, gröna ytor mellan flerbostadshus eller industribyggnader och även gröna stråk mellan vägar definieras av SCB som grönyta.” (Malmö stad, Grönyta, Online)

9

The most well established classification of ES has four different categories; those are: supporting ES, provisioning ES, regulating ES and cultural ES (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 2005) (see figure 1). There is a slight difference whether the described ecosystem services are global and have influence on the human race globally, or we are just talking about ecosystem services found in urban landscape. The urban ecosystem services are providing fewer resources and there is more focus on the social benefits as mentioned here by Breuste and Qurashi.

The concept of ecosystem services predominantly focuses on the resource provision and functional aspect of ecosystems. The concept of urban ecosystem services (UES) deals with the benefits that urban society and each single resident of a city gains from natural processes and ecological functions provided by urban ecosystems (Breuste & Qurashi, 2011, p. 315).

Category Description

Provisioning services Products obtained from ecosystems like food, fiber and energy.

Regulating services Benefits from regulation of ecosystem processes like pollination, seed-dispersal, pest regulation, air- and water filtration.

Cultural services Nonmaterial benefits from ecosystems, like spiritual enrichment, cognitive development, recreation, and aesthetic experiences.

Supporting services Ecological functions such as nutrient cycling and soil formation seen as necessary for the production of all other ecosystem services.

10

The main focus in our study is on the cultural/recreational ecosystem services as those can be measured without biological/bio-scientific knowledge and therefore we are more eligible to conduct such a research than if we would concentrate on the supporting, provisioning or regulating ecosystem services. As can be seen in figure 1, cultural ecosystem services are non-material benefits, such as recreational facilities, health benefits, sensual experience, social interactions, nature education and symbolism and spirituality.

2.1.1.ECOLOGICAL SIDE OF ECOSYSTEM SERVICES

The subcategories of provisioning, supporting and regulating ecosystem services are many and would cover most of this paper’s space if we would count them all. And since the cultural services are of our main interest, we consider to only briefly explain what these three categories include.

Regulating services relate to how natural and semi-natural ecosystems regulate essential ecological processes and life support systems and thereby maintain the health of the biosphere. This process brings such benefits to humans as clean air, water and soil. The supporting services include a refuge and reproduction habitat to wild plants and animals, which are necessary for the conservation of biological and genetic diversity and evolutionary processes. Provisioning services exist when e.g. carbohydrate structures, co2, water and nutrients, provide goods for human consumption. These goods can be in form of raw materials and energy resources to consumable food (adapted from deGroot et al. 2002).

2.1.2.SOCIAL SIDE OF ECOSYSTEM SERVICES

The ecosystems are serving us humans best when the influence is direct and the benefits they provide is strong. Not only do we receive direct benefits from materials that the ecosystems provide but also from non-material services and “natural ecosystems provide almost unlimited opportunities for spiritual enrichment, mental development and leisure” (deGroot et al. 2002, p. 401). Green areas and the ecosystems found there affect our health and mind in a positive way through the opportunities they provide for physical exercise or movement, through the clean air and reduced noise, through the smell of leaves and flowers and the sounds of birds or running water. These elements have been proven to have benefits to our physical and mental health (Stigsdotter et al. 2010; Kronenberg 2012).

Other cultural ecosystem services include the possibilities of social interaction, which can also influence our health positively; spiritual enrichment, using nature for religious or historical purposes; and for nature education to “enrich objective knowledge of natural and social sciences, e.g. botany, biology, history and archaeology” (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment 2005, p. 5). To connect the cultural ecosystems with our focus on sub-urban parks we introduce two listings of people’s experiences and preferences. The first one a) provides information of the cultural functions and services attributed to natural ecosystems, and the second one b) is the result of a study in Sweden showing what characteristics of a park people value the most. These two listings inspired us while creating the questions in our survey, and the names of features and services presented here are the ones we will be referring to in our analysis.

11

a) Cultural functions and services of natural ecosystems (adapted from deGroot et al. 2002):

Aesthetic information - According to deGroot, Wilson and Boumans many people prefer to live

in aesthetically pleasing environments and that reflects their preferences of natural areas as well. Real estates near scenic parks or views are usually more expensive than similar types of houses in less favored areas (deGroot et al. 2002, citing Constanza et al. 1997).

Recreation and tourism - People appreciate places to rest and refreshment and places for

recreation such as walking, hiking, camping, fishing and swimming. Tourism (especially eco-tourism) also falls under this category.

Cultural and artistic inspiration - “human culture is embedded within natural systems” as nature

is used as a source of inspiration for books, magazines, film, photography, paintings, sculptures, folklore, music and dance and other things.

Interesting point from deGroot, Wilson and Boumans is that this is a function we are not very conscious about although we constantly use nature for these purposes.

Spiritual and historic information - these are natural elements related to heritage values but it

also means that religious values are placed on nature (e.g. worshiping trees or animals).

Scientific and educational information - Ecosystems provide opportunities for environmental

education (e.g. preschool field trips and collection of nature productions, school excursions, ‘field laboratories’ for scientific research etc.)

b) As characteristics of a park can influence the number of visitors and their activities in the park we present here the 8 visual, emotional and social characteristics that people appreciate in urban parks (adapted from Stolz et al. 2012):

Serene - a place of peace, silence and care with sounds of wind, water, birds and insects

dominates over the sound of other people. In this kind of environment people don’t want to be disturbed by the sight of rubbish or weed.

Wild - a place of fascination with wild nature and the plants seem self-grown as well as lichen

and moss-grown rocks. Paths seem like they have been there from ancient times and are not maintained.

Lush - a place rich in species. A room offering a variety of wild species of animals and plants. Spacious - a place for thoughts and refreshments. A breathing-room offering the get-away

feeling, a feeling of “entering another world”. Here you don´t see the limits of the park, it should be like a Scanian beech forest or a middle-Swedish conifer forest.

The common - a green open place or meadow, allowing vistas and stays. A place for the circus to

put its tent, a flea market or a place for recreational activities.

The pleasure garden - a place of imagination. An enclosed, safe and secluded place where you

can relax and let your children play freely. This is where you will find playgrounds.

Festive center - A meeting place for festivity and pleasure.

Culture - the essence of human culture, monuments, old trees and buildings. A historical place

offering fascination with the course of time.

All of those characteristics embellish a green area for the visitors. Rich biodiversity and diversity in visual infrastructure (e.g. hills, meadows, forest, lake or pond, creek, bushes, flower beds… etc.) are appreciated by visitors attractive and therefore among the components that make a park more valuable. The fact that some of the characteristics overlap with some of the cultural

12

ecosystems provided indicates that people’s preferences coincide with the services that are offered. Maybe these services can even be strengthened by a form of a partnership of parks or a full, direct connection between them and this will be looked at in the next section.

2.2. Green areas and connectivity

There are multiple ways to connect parks with each other through green corridors, green wedges or green belts. Green belts are a very popular method from the early 19th century to prevent urban sprawl or further expansion of cities. Corridors are defined as:

Any space, usually linear in shape that improves the ability of organisms to move among patches of their habitat. It is therefore important to recognize that what serves as a corridor for one species may not be a corridor or may even be a barrier to another. Corridors can be natural features of a landscape or can be created by humans. (Hilty et al. 2006, p. 50).

The ability of the species to move among the patches of their habitat is measured and classified under ‘Connectivity’ (Hilty et al. 2006, p. 50). The main goals for creating green corridors, and thereby perhaps connecting parks, are e.g. improvements of the biodiversity, thus improving the connectivity and the well-being of the inhabitants (humans and non-humans) in and by the green belt area.

A green belt is generally known as a wider, open urban green area, which is connected with a dense, urban built development as a bigger town or a city. Due to the lack of open green space urban planners try to create nature conservation centers, which are able to balance the nonexistence of green spaces within the denser parts of the city. Reasons for building green belts are, among others, landscape protection, landscape restoration, nature conservation and to keep the rural character (Gather & Unterwerner 1992; Hilty et al. 2006). It is important to sustain biodiversity of plants and animals by keeping the rural and natural character so the animals are able to behave like they would do in their ‘real’ natural surroundings. Some green belts have been built to prevent cities from growing into joint cities, while others “assist in the safeguarding the countryside from encroachment [...and] urban regeneration, by encouraging the recycling of derelict and other urban land” (Amati & Yokohari 2006, p. 127). Hilty et al. (2006) coincide with that by further clarifying that green belts could be developed because of suspected floods in the area, topography or further reasons.

There are different shapes of green belts, they do not all look like a ‘belt’, which is wrapped around the city. The green belt around the city of Berlin, developed through connecting several parks and forests with each other, is known as ‘the star model’ because of its star-like shape. The city of Copenhagen also has a green belt, which is in the shape of ‘fingers’. The Green Belt in Frankfurt (Appendix 2) was built to prevent urban sprawl and to prevent the city from further growth. Gather and Unterwerner (1992) criticize this explanation and claim that the green belt was built in this location since this area would not have been valuable as a housing or industry area due to the air corridor and noise pollution.

As mentioned before, one of the main goals of creating a green corridor is to maintain or increase the richness of species. The species have a higher chance of reproduction as sources of food, materials, breeding places and energy resources are provided in higher quantity than a regular city park. In general, the availability of other species in big green areas is higher because those areas are more attractive for the named reasons. When reproduction is in this way easier, it can help to increase the richness of species (Hilty et al. 2006). Another reason to promote green corridors is that it could possibly aid with allowing free movement of animals within the area.

13

Many animals die in high numbers when they have to cross streets to go from one green area to another but with green corridors the animals are able to travel further to look for resources, yet still protected by the green area.

Not only do the green corridors provide more space to move, they can also lead the movement of the animals and “increase over-all species’ persistence compared to equivalent patches of habitat that lack connectivity” (Hilty et al. 2006, p. 108). With better connectivity there is less risk of inbreeding. An increased genetic variability between populations in the animal and plant kingdom is important according to Hilty et al. (2006, citing Beier & Loe 1992 and A. F. Bennett 1999). Some disadvantages of the green belt, regarding topics as economic growth, city growth, urban sprawl, and other economic related topics, have been discussed in other research but those topics will not be discussed further in this paper.

2.2.1.THE SOCIAL BENEFITS OF CONNECTING GREEN AREAS

Connecting parks, forest or any other urban green area with green corridors gives not only the animals, but also the humans a possibility to move greater distances within the green area. This might be specifically important when performing activities such as hiking, biking, horseback-riding and running. The paths for cycling, hiking or walking improve a sustainable mobility, which provides a healthier and cleaner environment and improves the health of the individual (Banister, 2008). Even if greenways are supposed to be compatible for both animals and humans, it has to be considered that some species of the wildlife, which usually steer clear of human contact, may not settle in areas where a lot of humans are active. Therefore to keep the biodiversity from being harmed by human activities it is important to keep some places for humans but others only for the wildlife as foreign plants and weeds “brought in by human activities can out-compete native plants, including food sources for wildlife” (Hilty et al. 2006, p. 113). Greenways within or around the built environment provide free ecosystems to the humans, like clean air, materials, a place to socialize and educate, just to name a few of the ecosystem services but they can also benefit humans by ensuring aesthetic surroundings (Amati and Yokohari 2006). In this summary of Hilty and his colleagues it is worth noting that green corridors can be in forms that we would normally not consider as ‘green’ (e.g. road-crossing structures) but can increase the sustainability of the areas:

In summary, corridors can take many forms and can be beneficial for natural and human systems on a variety of different scales. From road-crossing structures to watershed corridors to continent-wide connections, they can facilitate dispersal and migration and increase the overall quantity of habitat available, helping individuals move and populations retain connectedness (Hilty et al. 2006, p. 115).

The benefits of a creating greenway and increasing connectivity are various and can be of much use for the visitors of the parks. In the following chapter we present our cases, the parks we have studied for a possible creation of a greenway.

14

3 - The Cases

We have selected three parks as our cases for this research. Bulltofta park, Husie Mosse and Remonthagen park. The present common nominator of these parks is that they are all placed in the suburban area Malmö Öster, East Malmö (see figure 2), and the Risebergabäcken stream runs through all three parks. All of them, although man-made, have some more untouched nature aspect and a forest resemblance than the usual Malmö park, which is why we chose them since our main focus is to explore if people do appreciate that kind of natural landscape within the urban area. We present the parks below in the order that one usually reads a map, i.e. from north to south.

Malmö has had a long tradition of connecting parks and other green areas with each other or with the surrounding environment. Since 1920 Malmö urban planners have formed ideas and inspirations from German and American urban planning about linkages of parks and the surroundings. Even as early as 1879, a Malmö merchant suggested to the municipality that workers in the city did not need the grassy plains in Kungsparken (the King’s park) for their well-being, much rather were they in need of a more forest-like park (Pehrsson 1986). However, it was not until a 100 years later that this vision became a reality with the planning of Bulltofta park. All of the green areas within the city borders of Malmö are man-made, created and planned, mostly former industrial sites and brownfields (Broström et al. 2008; Mattsson, 2015; Pehrsson 1986) and different types of parks have been developed. The latest trend is the ‘landscape’ park, where the potentials of the original landscape are used and the landscape is the model of the park, but it also means that there is a large transformation of the environment (Pehrsson 1986).

Figure 2: Map of the study area

15

Figure 3: Map of Bulltofta park

Historical predecessors of the landscape parks are ‘English manor parks’ (Pehrsson 1986) but of course every phase in history puts its mark on how parks are developed and what is mostly valued in the design. In modern history of Malmö landscape parks with an intermediate position between the natural park and the city park has resulted in parks that have a realistic resemblance to original nature and forests. Such parks are Bulltofta park, Husie Mosse and Remonthagen/Jägersro, our three cases, which we have to admit believed at first to be real nature and not man-made. In the 20th century Malmö has changed from being a “grey industrial city” to the “future’s ecological city” (Broström et al. 2008, p. 120) but it is still an ongoing process which has its faults. The E6/E20 motorway surrounds Malmö and outside of these city borders there are only farming acres, therefore any kind of link or access to unspoiled nature outside the city border is not to be found (Broström et al. 2008).

The description and information about the parks, provided in the following subchapters, originates from various official documents from Malmö stad, their website, as well as the interview with Arne Mattsson. In 2014 the city’s Environmental Department (Miljöförvaltningen) mapped and valued the ES provided by the Riseberga stream specifically (Malmö Stad 2014b). We used this report as a source because the stream plays a significant role in the structure of the parks and for the ecosystem services.

3.1. Bulltofta park

As Skåne region is very flat and has few forests, hills or mountains, two landscape architect students detected the need for more natural landscape within the urban area around the

1980s (Malmö Stad,

Bulltoftaparken, Online). Before the park was created there was an airport in this area and some farmland. The land used for the park consisted out of old gardens and private land, which had no

trees and so the first thing was to draw up a plan for how to shelter

the park from the wind. The basic plan was to create a park with strong nature impressions as well as having as little maintenance cost as possible. The goal was that the park would in 20 years look more like a forest. Work went on from 1983 to 1992, and the park was divided into three zones. The nature zone is the biggest part of the park with many different tree arts (birch, oak, elm, ash tree), dry- and wetlands and ponds. The park zone has more traditional park like features, arboretum and cultivation allotments. The third zone is the recreation- and sport zone, with an indoor and outdoor gym, mini-golf, football, tennis and basketball fields. The third zone was created on the plains of the former airport (Malmö Stad, Bulltoftaparken, Online). Today Bulltofta park is 87 ha and it is considered one of the main recreational parks in Malmö. The park is well used by joggers, runners and walkers, there are frisbee-golf tracks, orientation runs are organized, and in winter the hills are much used by kids and others for sledge and ski riding.

16

3.2. Husie Mosse

Husie Mosse is approximately 2,7km southeast of Bulltofta park, which takes 9 minutes to bicycle or 30 minutes to walk2. It is divided in two parts, the northern part has a strong impression of nature, with a group of tall pine trees among sand slopes which are an important habitat for the threatening population of sand lizard. The southern part has a big lake and broad paths around the lake. There are picnic tables and

benches by the path around the lake so one can enjoy some bird watching or just the beautiful scenery. The northern part is owned by the Swedish military and there is a shooting area at the park’s edges. This could explain the structural differences to the southern part, which is owned by Malmö City. But is worth mentioning that the military does not use this area to any extent anymore and Malmö City has been trying to buy that land to complete the ownership of the park.

2According to measurements for walking and for bicycling on Google Maps Figure 4: Maintained paths and a view to the forest in Bulltofta park

Figure 5: Sand dunes and pine trees in Husie Mosse

Figure 6: Sign with information on the lizards in Husie Mosse

17

Husie Mosse is in total 32 ha (northern and southern part) and it was built as a nature and recreation site (Malmö Stad 2003). It was created as a park at the same time as Bulltofta park, in the beginning of the 80´s. Originally, the land was a swamp or even totally covered by water (hence the “Mosse” name in Swedish which means swamp), but it was dammed up creating the present half a kilometer long lake.

3.3. Remonthagen/ Jägersro

Remonthagen park, owned by Malmö stad, is only a small part of the Jägersro green area which is private owned. However, we chose to take the whole 66ha area into consideration since there are some recreational facilities outside the Remonthagen park borders. Moreover, the whole area, including Remonthagen park, is outlined 66ha and called Jägersro in the ‘Environmental Protection Plan’ (Naturvårdsplan) of Malmö Stad (2012).

The Riseberga stream forms a kind of a border between Remonthagen park and the rest of the area but wider green area is accessible by crossing the stream at two places. Nevertheless, people might hesitate to access the rest of the green area from Remonthagen park because it is mostly structured as a riding exercise area and as two football fields owned by the neighboring

sport club Husie IF. Furthermore there is a big part of the Jägersro Galopp tracks in this area and some horse pastures.

Remonthagen/Jägersro almost borders with the southern end of Husie Mosse (see figure 7) with Amiralsgatan street in between. Remonthagen park was redesigned from an older green area, also in the 80’s like the other two parks, and also according to the latest trends in landscape parks. In Remonthagen park there is a very nice playground, the only one of the three parks, surrounded by a circle of tall trees, which gives it good shelter from wind. Surrounding the playground there are some meadows and trees. Near the stream there is one bench; other sitting possibilities are at the playground. According to the ‘Environmental Protection Plan’ of Malmö Stad (2012) the size of the area makes it more valuable and they suggest that the area could be used more as a recreational area than it is at present.

Figure 7: Map of a) Husie Mosse and b) Remonthagen/ Jägersro

18

3.4. Ecosystem services in the parks

Here we mostly discuss the regulating and the supporting ecosystem services. We chose to discard the provisioning services since the parks are man-made, mostly for recreational purposes or to enjoy the natural environment, and there are no major provisioning services. Maybe there are some smaller ones, such as berries, mushrooms or edible plants to be collected but that is at such a minor scale we prefer to focus on the three remaining ES.

The Riseberga stream, which runs through all three parks, is a very important element for Malmö city because any form of running water is scarce around the city. It is also extremely important as a draining system and functions as the main rainfall attenuation. According to Miljöförvaltningen´s report (Malmö Stad 2014b) the ecosystem services that the stream provides are the regulating, supporting and cultural one. Not so much provisioning service although some herbs and edible plants grow along the stream. This stream is also important as it is a habitat for many different organisms at young stage. It provides the perfect environment for reproduction of species as well as providing a protective environment for the youngs. Furthermore it serves as a food source, not only for animals there is a possibility to do some fishing in the stream. One problem has been detected (Malmö Stad 2014b) and that is the invisibility of the ecosystem services that the stream provides, which are then taken for granted or highly under evaluated. Exploitation of land around the stream has created more impermeable surfaces which again increases the stream to overflow at heavy rainfall and high sea level.

Around 250.000 trees have been planted in Bulltofta park of which deciduous trees are dominating. In Bulltofta park there is a forest-like area, water elements in the form of five ponds (small and big ones) and a stream, there are meadows and a hilly landscape.

Figure 9: Playground at Remonthagen/ Jägersro

19

Some of the ponds have a natural origin, but others are man-made. As reported on Malmö stad’s website (Malmö Stad, Bulltofta, Online) 35 bird types nest in the park, compared to 7-8 types in the traditional Malmö park.

Husie Mosse has a relatively larger lake than are to be found in Bulltofta park, and because of that this park is considered to be a ‘Biological Hot-spot’ (Malmö Stad, Biologiska hotspots, Online) where many birds nest, both common types and rare. The vegetation is also rare in some spots, with a few types of orchids where for some, such as the ‘Majnyckel’ Husie Mosse is the only growing spot in Malmö (Malmö Stad, Husie Mosse, Online).

In Remonthagen park some amendments have been made to the Riseberga stream as prevention to natural catastrophes, like floods. This could have positive effects on other ecosystem services and on activities performed in the surroundings, such as the horse riders who enjoy riding along the stream and bird watchers who have a hut nearby Husie Mosse lake.

20

4 - Epistemological Considerations and Methods

We considered the subject matter of this research better suited to be studied in a qualitative rather than quantitative research, because the qualitative research helps best to explore “subjective” understandings (Flick, 2009). Furthermore, we believe that the qualitative research enabled us for an in-depth understanding and interpretation of the content of the phenomena under study. Therefore the inference in this research is interpretative because the researchers want to understand people’s subjective experiences of the parks and interpret some sense in the patterns observed (6 & Bellamy 2012). In this paper we have taken an inductive approach on social benefits of ecosystem services in sub-urban area of Malmö and we have structured the paper with a longitudinal research design, which is explained by Bryman (2012) as an “extension of survey research based on a self-completion questionnaire [and] or structured interview research within a cross-sectional design” (p. 63).

4.1. Park as process

Our ontological and epistemological considerations for this research are based on our deep interest in the way green areas function for people as well as for the biodiversity. We consider it to be very worth knowing, how the ecological elements of the parks adjust to the social functionalities and vice versa. To us nature has great value and we have a responsibility to preserve it as much as we possibly can. From that standpoint we did this research, to find out what values other people have of nature, and especially these parks that resemble a more natural look than many other parks in Malmö.

It is interesting to explore the process of how the users construct the parks because we know that the natural aspect of parks, the animal life and plants, are constantly changing and will not be the same today as it was maybe 10 years ago. People‘s habits and values also influence this semi-chaotic development of a park. However, we cannot talk about social constructionism since the process is the interaction between nature and humans and not entirely on a verbal intellectual level of only humans. We have ecosystems, but then these ecosystems also give service to humans and that can be a parameter of how we experience parks. People experience parks differently and their views and experiences are implicitly formed by the ecosystem services, although people do not make a direct link between these factors when enjoying the park or nature. In a positivist perspective the park and its features could be described, but that is not exactly what we are doing. We are more describing moments in the process of the parks and how the parks can be of benefit for us humans in harmony with nature.

4.2. Methods

This chapter describes in more detail the research methods we have used for this paper. We furthermore clarify why the intended methods were chosen for this specific research. For this research we have conducted an empirical research and therefore dealt mostly with primary data. Primary data are generated by the researcher, who formulates the research design and are thus collected and analyzed by him/herself (Blaikie 2003). On the other hand secondary data are raw data, which are created by someone else either for general information purpose, such as statistical data, or for specific office purpose (Blaikie 2003). The documents are understood as secondary data while field observations and interviews are considered to be primary data. The following subchapters explain each data creation and collection of data separately.

21

The methods in this research paper consist of ethnography and participant observation. Ethnographic research means that the researcher himself or herself observes and does interviews within a group or a community or any other kind of ethnographic group. For our explorations of the ecosystems and their social benefits we did a survey, which formed the base of our analysis and we observed the parks and the people visiting them and then we conducted some informal, non-structured, interviews with some of these people. Furthermore, we conducted one semi-structured interview. This is in many ways reflecting Bryman’s (2012) listing of what the ethnographic does: “immerses him- or herself in the group for an extended period of time, observing behavior listening to what is said income versus a sense both between others and with the field worker and asking questions” (p. 432). There are multiple differences in ethnographic research regarding the setting, style and methods used in the research. Not only are the settings of the site important, but the position and role of the observer is important as well.

The first difference is the overt versus covert ethnography. The overt ethnography is used when researchers are transparent and open in their observation field. During this research we were not discreet about our work nor did we do any observations from a distance. We rather blended in the settings with people. However, it could maybe be called a more covert style because when entering a setting we didn´t explicitly start explaining to everyone what we were doing. Another, more covert, style we used was that in some occasions we felt that approaching people pretending that we were unfamiliar to the settings (e.g. did not know about the park’s facilities or paths) was an easier way to start a conversation and get relevant information than to start the conversation saying that we were doing a research. The second difference is whether it is an open or a closed setting. This determines that an open setting is a space with public access, not segregated, gated or in any other way inaccessible. The parks, which form the setting of our study, are all public spaces generally available for everybody.

4.2.1DOCUMENTS

The documents we have collected and analysed during this research consist of material found on Malmö stad´s official website, www.malmo.se, an official document/report about the ecosystem services around the Riseberga stream from the Environmental Department of Malmö stad, and a few other official documents and reports about the parks. We plunged into the documents to orientate ourselves and we looked at how the parks are presented to the public. The report from the Environmental Department presented the work the officials at this department had done mapping the Ecosystem Services in and around the Riseberga Stream, as well as the potential economic benefits of the ES.

On the website of Malmö stad we looked at all information we could find about the parks, and that also included online interactive maps. In this process we discovered that Husie Mosse and Remonthagen are not listed under Nature- and recreational areas (Natur- och rekreationsområden) but Bulltofta park is. However, Husie Mosse is under this category listed as a “biological hot-spot”. The interactive maps (figure 11) showed us e.g. bicycle paths, other nature areas in Malmö, places where it is allowed to barbeque in parks, culturally interesting sites and accessibility to the parks in our research, for example wheelchair access. According to these interactive maps both Husie Mosse and Bulltofta park are marked as good bird-inspecting sites.

22 4.2.2FIELD OBSERVATIONS

On several occasions we visited the parks in this research. During our visits we took pictures in the area, observed how many people were in the parks and what they were doing. We also took note of the structure of the park, as we perceived it, and we randomly and informally talked to people we met. For the purpose of validity we visited each park at least 4 times and we tried to select different days to visit the parks, to observe presence of people on weekdays as well as weekends. Observation time also depended on the weather conditions and our limited writing time for this thesis. Bulltofta park lies on a daily cycling route of one of the researchers and therefore during frequent bicycle rides through the park it has been observed more often than the other parks, although it was not noted as planned observation days. To ensure validity and reliability we created an observation schedule (see figure 12)

Figure 11: The interactive maps on www.malmo.se show various aspects like bicycle paths, nature reservoirs and Husie Mosse and Bulltofta as good spaces to watch birds (Red spots)

23 4.2.3THE SURVEY

We created the survey questions in English first and then translated them to Swedish (appendix 1). Since this survey was intended for Malmö citizens we chose to do it entirely in Swedish, although Malmö citizens are surely from many nationalities. We wanted to have the survey all in Swedish to avoid any misunderstanding or dismissals due to lack of language skills. Several pretests of the survey were conducted. First the online version in English was sent to 5 English-speaking students to test if multiple-choice answers worked, if the questions were understandable and if the overall purpose of the questionnaire was understood. Then we asked a Swedish native Master student to read over the Swedish version. When both versions had been revised and changed according to the comments, we did a test run on the Swedish survey with a printed version. During the ‘Valborg’ festival in Husie Mosse, which took place in the evening of the 30th of April, we handed out the survey to people in the park and asked them to fill it out for us. Thereby we also explained who we were and what our purpose was. With this mode we got some comments and questions from the people about statements in the survey that they did not understand. This helped us formulate the questions and statements even better before we launched the online survey.

The online survey was anonymous and people were given the freedom to skip any answer should they choose not to answer. They were given the option to complain or comment on the survey by sending an E-mail to us and a thank you note was attached at the end of the survey, as well. At first, E-mails were sent with a text in English, asking people for their participation, but follow-up Emails were written in Swedish and sent out 5 days later.

We decided that the population for our survey should be all Malmö residents so in order to get a good sample we followed these three criteria for accessing people:

- To get the views and opinions of as many residents as possible, living in as many different districts of Malmö as possible, we asked people we knew if we could send the survey to them and ask them to spread it further. We got positive reaction about our request from everyone so we sent a link to the online questionnaire in an E-mail and personal Facebook messages to all the Swedes we knew in the city. They were asked politely to re-post and share the link to all their friends and colleagues.

- We also wanted to get more views and opinions of the residents in the areas, neighborhoods, near the three parks in question to compare to the responses we would get from people living in other areas. So we searched for sport clubs, churches, schools and other institutes or clubs in these neighborhoods and sent them an E-mail with our request to answer the questionnaire and resend it to other members of their club/services. The E-mail addresses were gathered through research on Google, by mapping the areas and finding institutions, which have access to a lot of people.

- We looked for Facebook groups, which we could connect to and spread the link to the survey there. We had access to 3 big groups: ‘Jägersro Gallopp’, ‘Riseberga Anslagstavla’ and ‘Husie föräldrarförening’.

24 4.2.4INTERVIEWS

As a complement part of this research to other information we had gathered, we used an individual interview as one of the primary data creation method. Then we used the transcribed interview for the collection of relevant information to answer our research questions. Furthermore, we conducted several informal interviews in Swedish and English with random people we saw in the parks. The procedures during the interview are presented briefly in the following chapters.

4.2.4.1. Semi-structured interview with Arne Mattsson at Malmö City

On the 29th of April we met Arne Mattsson who is a landscape engineer at the Street- and Park department of Malmö City. The purpose of this interview was to get more detailed information about the history and development of the parks in our research. We had prepared some questions before the interview but when Arne had answered the first questions, we realized that some of the questions were not applicable anymore so they were not used. Actually the interview developed more into a spontaneous discussion than a real interview.

4.2.4.2 Approaching people in the parks

We approached people on several different occasions and tried to talk to as many as possible to get a better idea of what the visitors are thinking. While we were talking to visitors we tried to get some insight into how they perceived the parks. We revealed our identities and purpose to the people we asked to participate in the survey and after they had filled out the survey we asked them additional questions, very informally. We showed cultural interest in the park and events, which led the discussions from there. On other occasions we mostly approached people by pretending we did not know the park so well and that we were looking for ways to go around with our bicycle. These were all spontaneous and unprepared approaches, which ended in questions to people about their experiences with the park.

An example of the questions we asked during our visit: “Is there anything you would like to see improved in this park or its surroundings?”, “Do you come here regularly?” “Do you live within the area (Malmö Öster)?” People were always given the freedom to answer this voluntarily. It was noted down if they had children with them or not for the purpose of comparing the answers with the survey. As we noticed quickly in the beginning that people were more reserved and often rejected to speak in English, all further interviews were held in Swedish to avoid misunderstandings or barriers because of language differences.

4.2.5ANALYSIS METHODS

For the analysis of the survey and the results of our interviews and observations we used the ethnographic content analysis method (Bryman 2012). The advantages of a content analysis in general are that it is a “very transparent research method, therefore very good for follow-up studies and transparency often causes content analyses to be referred to as an objective method of analysis” (Bryman 2012, p. 304). According to Bryman this type of method also gives access to information about social groups, which is difficult to gain access to. In the case of this research the possible users of the parks are non-identified groups and therefore not easy to get access to them. They could be people living in the neighborhood or someone, who live at the other end of town. And as two of the parks showed much less presence of people it was even more difficult to gain access to a possible user group. Due to a back and forth movement between the different steps of the analysis this analysis becomes very specific in procedure

25

detail. The ethnographic content analysis contains procedures or steps, which are typical within qualitative content analysis (Bryman 2012).

We chose to do a SWOT-Analysis to evaluate the ecosystem services of each park and the connectivity of the parks. As we have different primary and secondary data, the SWOT- table can be illustrative for summing up the entire material. For the analysis we will use the SWOT- Analysis both in textual form and as a table.

4.2.6VALIDITY AND RELIABILITY

In line with Bryman’s (2012) validity categorization we will view how validity is indicated in our research. As our research touches upon ecological issues in connection to people’s everyday life, we need to examine ecological relevance in this paper. Ecological relevance, also called ecological validity, explains the social scientific findings, which are applicable to people’s everyday life and natural social settings. Findings will be ecologically valid if the social sciences intervenes in a natural setting and as our research takes place in parks we conclude that as a natural setting and therefore ecologically relevant. However, we think it is questionable to use the term ‘validity’ and prefer to use ‘relevance’ which is more applicable in this context. To ensure external validity we have specified and structured the concepts we use for clarification and then deduced our research questions and aim from these concepts. This is especially important in interpretative studies to be able to “develop appropriate research instruments and apply them accurately and consistently” (6 & Bellamy 2012, p. 132).