Vulnerable

data interactions

augmenting agency

Vulnerable

data interactions

augmenting agency

Nicole Carlsson

Thesis project II

Interaction Design Master

School of Arts and Communication, K3 Malmö University, Sweden

08/28/18

Supervisor: Susan Kozel Examiner: Henrik Svarrer Larsen 2nd edition

54

Acknowledgement

Deepest thanks my to supervisor Susan Kozel for generously providing timely inspiration and helping me shape this work. Sincere thanks also to Nikita Mazurov for sharing wonderfully holistic InfoSec perspectives, practical knowledge along with interesting discussions. Warm thanks to Roxana Escobedo and Raya Dimitrova for the Privacy

Rapist feedback and sketching session and to Kevin Ong and Michelle

Westerlaken for valuable midway feedback. A heartfelt thanks to all the participants of the Placebo Sleeve Inversion probe. Finally, thanks to all friends and family for your support during these studies.

Abstract

This thesis project opens up an interaction design space in the InfoSec domain concerning raising awareness of common

vulnerabilities and facilitating counter practices through seamful design. This combination of raising awareness coupled with boosting

possibilities for deliberate action (or non-action) together account for augmenting agency. This augmentation takes the form of bottom up micro-movements and daily gestures contributing to opportunities for greater agency in the increasingly fraught InfoSec domain.

1 Contents

1. Introduction

1

1.1 Problem statement

1

1.2 Research question

2

1.4 Motivation

2

2. Field

4

2.1 Abstract to concrete

4

2.3 GDPR

5

2.4 InfoSec

5

2.4.1 Security 6 2.4.2 Privacy 7 2.4.3 Man-in-the-middle attack 82.6 Transparency

9

3. Design approaches

9

3.1 Seamful Design

9

3.2 Critical Design

11

3.3 Adversarial Design

12

3.4 Related work

12

3.4.1 White Box 12 3.4.2 Data Dealer 133.4.3 The Internet Phone 13

3.4.4 Obfuscation: A User's Guide

for Privacy and Protest 13

3.4.5 Find My _________ 14

3.4.6 The Bronze Key 15

3.5 Design takeaways

15

4. Design Process

16

4.1 Privacy Rapist

17

4.2 Hen-in-the-middle

20

4.3 Interviewing Nikita Mazurov

26

4.4 Tangible email encryption

27

4.5 Placebo Sleeve Inversion

29

5. Conclusion

336. References

35

Appendices

39

A Interviewing Nikita Mazurov

39B Workshopping Tangible encrypted email

491. Introduction

Capturing people's data for profit or political gain appears to be the dominant activity of corporations and government agencies alike in the western world today (Zuboff, 2016; Christl & Spiekerman, 2016; Lanchaster, 2017).

Edward Snowden’s 2013 whistle-blowing (Maass, 2013; Žižek, 2013) regarding governmental surveillance practices was an eye opener for most. A glaring example of political manipulation of data is the recent Cambridge Analytica scandal where individually targeted political manipulation was caused by Facebook —unbeknownst to users — granting third parties unauthorized access to user data for political profiling (Cadwalladr & Graham-Harrison, 2018). Both the 2016 U.K. Brexit vote and U.S. presidential election of Donald Trump were affected, which arguably has caused political uncertainty and unrest. Sadly, it is vital to stress that Facebook is not the only company that should be taking heat (Hern & Wong, 2018) for neglecting user privacy and security. Shoshana Zuboff coined the term 'Surveillance Capitalism' when sketching out how Google Inc. challenges democratic norms and departs from market capitalism producing "new markets of behavioral prediction and modification" (Zuboff, 2015). As security and privacy researcher Bruce Schneier pointed out in a blog post:

Surveillance capitalism is deeply embedded in our increasingly computerized society, and if the extent of it came to light there would be broad demands for limits and regulation. But because this industry can largely operate in secret, only occasionally exposed after a data breach or investigative report, we remain mostly ignorant of its reach. (Schneier, 2018, March 29)

The industry's ability to operate in secret has created an asymmetric relationship, the big data divide, and a power imbalance (MacCarthy, 2016). People are unable to anticipate the potential uses of their data or recognize the data-mining processes and the sorting and targeting that result from this power imbalance (Christl & Spiekermann, 2016, p.123).

1.1 Problem statement

InfoSec is increasingly important to us on a daily basis, but still somehow comes across as removed, wrapped up in a distant rhetoric and taken out of our control. There seems to be a vested interest in assuming that people can not take action.

It appears that much of the security and privacy burden today is on users. Jason Hong argues for a sustainable privacy ecosystem where the privacy burden is shifted from end-users onto other entities such as developers, service providers and third parties. (Hong, 2017). The same could be said for security burdens. Technology & Society researcher Danah Boyd (2017) stresses that the culture of 'perpetual beta' has placed the public to function as quality assurance engineers, losing the integration of adversarial thinking from the design and development process.

In short, I think we need to reconsider what security looks like in a data-driven world. (Boyd , 2017)

Where is the interaction designer’s role in this? There are at least three levels of potential contribution here: (1) recognition — designing to raise awareness, (2) designing for action (or non-action) or (3)

2 3 designing for prevention. These could be seen as three layers or

modes of agency that can be facilitated by interaction design.

1.2 Research question

This thesis project can be framed in terms of the following research question:

How might interaction design contribute to an augmentation of agency in the current and increasingly fraught domain of InfoSec?

For the purposes of this thesis project, the key terms

agency and InfoSec are defined as following:

Agency

The interest and definition of agency for this thesis lies in awareness,

in relation to InfoSec and bodily data, followed by possibilities for deliberate action (or non-action). This is bearing in mind that agency

has several different definitions in a wide variety of fields, e.g. everything from voice, to control over women's reproductive rights. InfoSec

In this thesis project InfoSec, short for Information Security, encompassesboth security and privacy, which can be defined respectively as "the protection from harm" and

"the right to be left alone". (Jacobsson, 2008, p.11)

1.4 Motivation

Why this?

The initial motivation is an observation of a lack of agency in our computerized every day lives regarding bodily data in relation to InfoSec. The key audience is the interaction design research community.

But one could argue it is of relevance to people of all ages and walks of life. The physical and digital realm is blurred and blended today. The issue of security and possible death tied to hacked cars and medical devices may be relevant to most, but also more broadly affecting privacy, security and democracy. Why now?

InfoSec is a timely domain in the wake of the Cambridge Analytica whistle-blowing scandal and with the new European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) having taken effect May 25 of this year. Additionally, programming is becoming mandatory for all school

children in the coming years in Sweden. How will these young developers consider InfoSec as they code? This work could be relevant for any community where understanding InfoSec would make a difference for the public at large in terms of security, privacy and even democracy. Why Interaction Design?

Interaction Design can be seen as either difficult to define or as having several definitions. To start somewhere, here is what John Kolko has to say:

Interaction Design is the creation of a dialogue between a person and a product, system or service. This dialogue is both physical and emotional in nature and is manifested in the interplay between form, function and technology as experienced over time. (Kolko, 2011, p.15)

This definition is particularly relevant to this thesis project for the following reasons: Kolko's mention of both physical and emotional dialogue. Interaction design tends to live in a space between people and a system. It is not just about looking at an interface, but understanding the tensions, difficulties and potentials of this relation. Situated at the intersection of people and technology, interaction designers are key stakeholders in shaping computerized systems that are affecting privacy and security. Designers are also to be held accountable for their actions (or non-actions) in terms of giving privacy and security the serious consideration desperately needed when designing. Privacy is not an individual pursuit, it is a “from-the-bottom-up”, or grass roots, communal notion for those that are intrinsically disadvantaged from those who are advantaged." (Mazurov, Appendix A, p. 39). It is also intersectional (Crenshaw, 1991, p. 1244). Privacy relates fundamentally to agency. Interaction design is highly applicable here. Recognition, action (or non-action) and prevention are aspects that can and are designed for. It is the premise of this thesis project that agency needs to be materialized: we all need to feel that we have a voice, we have action, we are shaping the world we come in contact with, we are doing things when we speak, someone listens to us and something listens to us.

4 5

2. Field

When outlining this section materialities are drawn together and sketched out. Th e terms used may seem uneven, but what they are in fact revealing, is the material spectrum of this area. Th ere are diff erent materialities going on in this section, tensions and mixed messages. Th ese materialities may allow for unfolding diff erent layers relating to agency: layers of awareness/ unawareness and possibilities for deliberate action/ non-action.

2.1 Abstract to concrete

Th e design of this thesis presents a variety of materialities precisely because this topic exists among a range of materialities already in the world. Th is section is needed in order to design concepts, but also to give an overview of the political and data context that we are living in right now. Th is thesis argues for a journey from abstract to concrete real-life embodied experiences. 2.2 Internet of Things

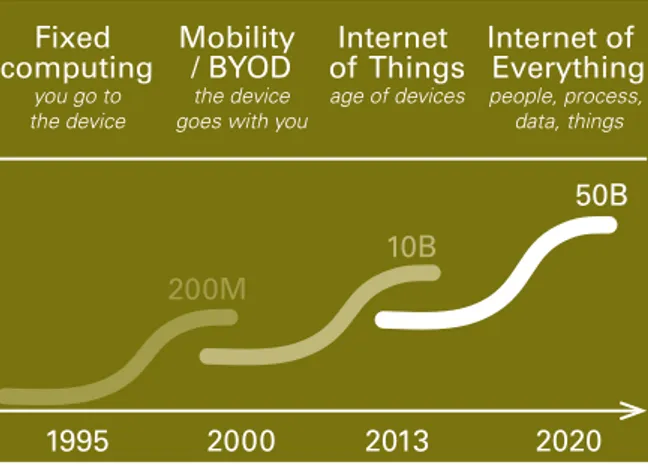

Computers are surrounding us in unprecedented quantities today and the numbers are expected to keep growing. Th is is exemplifi ed in a 2013 report by US computer network hardware manufacturer Cisco, in which the amount of connected 'things' is projected to reach a staggering 50 billion by 2020 (Fig 2.2).

Fixed computing you go to the device Mobility / BYOD the device goes with you

Internet of Things age of devices Internet of Everything people, process, data, things 1995 2000 2013 2020 200M 10B 50B

Figure 2.2 Cisco's vision and prediction of 50 billion devices by 2020 and what they call 'Internet of Everything'. (adapted from Cisco, 2013)

When it comes to data capturing, technologically IoT involves embedding sensors and actuators into everyday objects (things), connecting

them to the Internet and enabling them to send and receive data. As a consequence, whether a person is aware of it or not, sensors are often programmed to register everything you say and do in order to provide functionality. Th e resulting data body, representing a digital embodiment of a person, is stored in server farms, also referred to as 'clouds'. Over time, a detailed profi le of a person will be built up, as algorithms process, cross-reference, analyze and categorize the data. I.e. bodily interactions with systems are recorded, saved and stored as digital information, profi ling and (mis)representing a person, often without that person’s knowledge or consent. In terms of data handling these systems tend to be of a black box nature. I.e. it is not clear when and where data is collected, stored, shared with third parties, combined with other datasets or what algorithms are used to process the collected data for profi ling to act upon. (MacCarthy, 2016) In general, laws concerning who owns data are not straightforward. Furthermore, from a security perspective it is possible to

such as a heater, self-driving car or medical device.

An IxD perspective on the IoT could be to consider how aware/ unaware people are of the capture of bodily data in their everyday lives. Not to mention questioning how aware/unaware design decisions tied to this allows for people to take deliberate action (or non-action). As Marie Louise Juul Søndergaard and Lone Koefoed Hansen have pointed to, design is not neutral.

".. design is also a political medium. Through the design, the designer seeks to change the world in a way that is influenced by the designer's ideology. Even when the designer is not aware of this." (Søndergaard & Hansen, 2017, p.1) What if we engaged more in debate on what the default settings could be in terms of data capture and what type of values could drive these decisions? When is it meaningful for different systems and people to connect and interact? How could selection of captured data be more thoughtful? Who is benefiting from all the data captured? What types of biases do the algorithms processing the captured data support?

2.3 GDPR

Compared to the rest of the world, the European Union (EU) is in the forefront in terms of attempting to take some of the InfoSec burden from people's shoulders through judicial regulation. On May 25th, 2018, the EU passed the comprehensive General Data Protection

Regulation (GDPR). The details of the law are complex, but it is meant

to mandate that personal data of EU citizens only be collected and saved for "specific, explicit, and legitimate purposes," and only with explicit consent of the user. (European Commission, 2016)

Sweden adopted the GDPR with the adjustment of lowering the age of social media consent from 16 years of age to 13. Additionally if GDPR conflicts with existing Swedish constitutional laws:

Yttrandefrihetslagen ( freedom of speech) or Tryckfrihetsförordningen ( freedom of press), it will not be enforced. However, both Swedish companies and government agencies are susceptible to fines if not following GDPR rules. (Regeringskansliet, 2017)

There is a digital transformation of healthcare and social services planned in Sweden. All records previously stored on paper and older technologies is going to be replaced digitally. This type of data is sensitive and may have a tough time following GDPR. (Regeringskansliet, 2018) Christl and Spiekerman voice criticisms of GDPR from a privacy perspective. They point to a problematic vagueness in which the GDPR is phrased, while at the same time being so complex that only a select few specialized legal offices will be able to handle it.

We fear that this corporate reality will lead to a systemic interpretation of the GDPR that is not in line with the original ideas of privacy that were embedded in it. (Christl and Spiekerman, p. 141) An IxD perspective on this can be premised on continuing to support action (or non-action) on a grass roots level, complementing but not defaulting to the GDPR.

6 7

2.4 InfoSec

As noted in the introduction (section 1.2) the definition of InfoSec for this thesis includes both security and privacy. They will be covered in more detail below, along with an example showing a common vulnerability exploitation called a Man-in-the-middle attack. 2.4.1 Security

The glossary of the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) defines Information Security as:

Protecting information and information systems from unauthorized access, use, disclosure, disruption, modification, or destruction in order to provide— 1) integrity, which means guarding against

improper information modification or destruction, and

includes ensuring information non-repudiation and authenticity; 2) confidentiality, which means preserving authorized restrictions on access and disclosure, including means for protecting personal privacy and proprietary information;

and

3) availability, which means ensuring timely

and reliable access to and use of information. (NIST, 2017) Through the NIST definition above we can see how security and privacy are intertwined, through the concept of confidentiality. Another central concept is vulnerability, which can be defined as:

A weakness in a system, application, or network that is subject to exploitation or misuse. (NIST, n.d.) Security is a practice. It is not a binary state of being either secure or not. With enough time and effort, somebody will find a vulnerability and exploit it. Security, in a sense, is a matter of how hard we want to make it for someone to exploit a vulnerability. Privacy and security researcher Bruce Schneier stresses how security is a process and uses the analogy of a chain, only as secure as its weakest link. (Schneier, 2002) Schneier states that encryption, which can be defined as

to disguise confidential information

in such a way that its meaning is unintelligible to an unauthorized person (Piper & Murphy, 2002, p.7) is one critical component of security. Yet, many of the hacks seen in the news were due to weak (or non-existent) implementation/configuration of encryption. (Schneier, 2016) An IxD perspective on security could be to raise awareness of critical aspects of security, such as encryption and common vulnerabilities, in order to engage a wider spectrum of people to participate in countermeasures. Susan Kozel's (2016) Performing Encryption workshop work is of interest here. It experiments with full body movement improvisation to generate digital encryption keys and opens

up the scope for poetics, practical form, awareness and debate. 2.4.2 Privacy

Sociologist Christena Nippert-Eng describes privacy as a

... process of selective concealment [...] This is the daily activity of trying to deny or grant varying amounts of access to our private matters to specific people in specific ways. Whether focused on our space, time, activities, bodies, ideas, senses of self, or anything else we deem more private, this is the chief way in which we attempt to regulate our privacy, given the social, cultural, economic, and legal constraints at hand

(Nippert-Eng, 2010, p.3)

Similarly to how security is not binary, neither is privacy. (Fig 2.4.2) Nippert-Eng uses the analogy of a private island and a public sea. The beach then is the area where the boundary work (the strategies, principles and practices we use to create, maintain and modify cultural categories) and boundary play (used for amusement (public-private), the most powerful person present sets the boundaries) occurs.

Privacy Publicity The condition of (pure) inaccessability Private That which is completely inaccessible The condition of (pure) accessability Public That which is completely accessible

Figure 2.4.2 Privacy as one ideal endpoint of a continuum. (Adapted from Nippert-Eng, 2010, p.4) Nippert-Eng points out how the process of privacy "...requires

knowledge, judgment, skill and attention to selectively conceal or reveal in order to achieve satisfactory privacy levels."(ibid., p.8)

It becomes a mixed message when an Executive Chairman and former CEO of Google, a company known to collect vast amounts of data from people, states 'You have to fight for your privacy or you will lose it'. (Colvile, 2013) Is it a rallying cry or a warning? One could argue that it is an example of boundary play where Google, being the most powerful by holding the most information, sets the boundaries.

In light of this perhaps the most important aspect of privacy is the social and bottom up aspect as InfoSec researcher Nikita Mazurov phrased it:

There is a little bit of paradox there, because on the one hand privacy is about personal privacy and protecting yourself, but more holistically it's a collective concept [...] even if you think you have nothing to hide, privacy is not about you. It's about respecting the concept for people who are at risk [...] it is a collective notion rooted in the community standing united from the bottom up in safeguarding the rights of the disadvantaged from the advantaged.

(Mazurov, 2018, Appendix A, p.48)

Mazurov also uses the analogy of second hand smoking in relation to the concept of poor privacy habits, illustrating how practicing poor privacy habits inadvertently negatively affects those around you.(ibid) In the foreword to, famous hacker turned security consultant Kevin Mitnick's book The Art of Invisibility (2017), security

8 9 and privacy expert Mikko Hypponen notes how privacy is a

fundamental human right recognized by the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human rights in 1948.

No one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to attacks upon his honour and reputation. Everyone has the right to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks. (United Nations, 1948, article 12). As Hypponen continues

If our privacy needed protection in 1948, it surely needs it much more today. After all, we are the first generation in human history that can be monitored at such a precise level. We can be monitored digitally throughout our lives. Almost all our communications can be seen one way or another. We even carry small tracking devices on us all the time — we just don't call them tracking devices, we call them smart phones. (Mitnick, 2017)

In the wake of GDPR coming into effect, the Norwegian Consumer Agency published a report of an analysis of how three large technology companies: Facebook, Google and Microsoft are giving people the illusion of control, while in reality actively nudging (Consolvo, 2009) people towards privacy poor options. (Forbrukerrådet, 2018) This type of deceitful design, sometimes referred to as dark

strategies or patterns, is common and research is active in this

area. (Bösch, Benjamin, Frank, Henning & Pfattheicher, 2016; Acquisti et al, 2017; Schneider, Weinman & Vom Brocke, 2018) An IxD approach could champion privacy friendly default settings along with bringing the social aspect of privacy more to the fore, seeking to support community efforts in countermeasures for safeguarding awareness of poor privacy and provide possibilities for deliberate action (or non-action) for the disadvantaged. 2.4.3 Man-in-the-middle attack

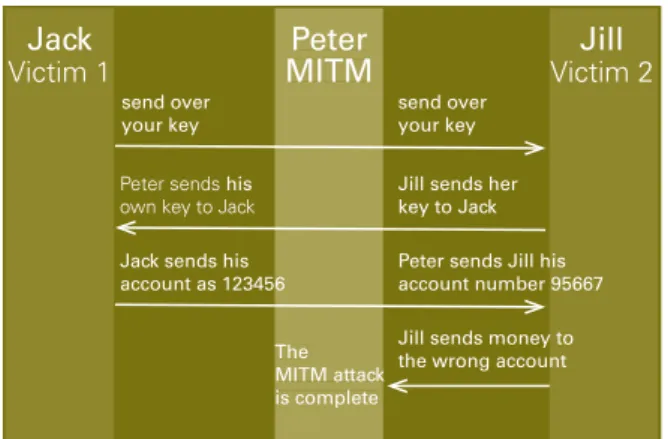

An example of a data related common vulnerability exploitation involving integrity, confidentiality and encryption (see section 2.4.1) is called a Man-in-the-middle attack (MITM).

This is an attack that can occur in conjunction with public Wi-Fi hotspots situated at e.g. a coffee shop, airport or shopping mall. The attacker inserts themselves in between a victim's computer and the Internet. Alternatively the attacker sets up a rogue hotspot and names it similarly to the current location—e.g. Free Airport Wi-Fi— . When the victim connects, their data flows through the attacker's computer first, enabling the attacker to either eavesdrop on or manipulate the data flow. Usually this is done in order to grab any password and username the victim happens to submit during their browsing. If the website the victim is visiting is using https encrypted sessions, the attacker cannot read the data. However, many sites only use https for login and then switch to insecure http, allowing attackers to steal victim's sessions, including personal data. There are also still websites that do not use encryption at all. (Henning, 2018, p.12; Veracode, 2018; Sims, 2016) To exemplify the sequence of such an attack: Peter is performing a Man-in-the-middle (MITM) attack. (Fig. 2.4.3) He inserting himself into the data flow, tricking both Jack and Jill on either end to think

that they are talking to each other securely, while Peter is both eavesdropping (passive attack) and manipulating data (active attack) by making Jill send money to his account number instead of Jack's.

Jack

Victim 1 MITMPeter

The MITM attack is complete Jill Victim 2 send over your key send over your key Peter sends his

own key to Jack

Jill sends her key to Jack Jack sends his

account as 123456 Peter sends Jill his account number 95667 Jill sends money to the wrong account

Peter MITM The MITM attack is complete account as 123456

Fig. 2.4.3 Example of an MITM attack process (adapted from Veracode, 2018).

2.6 Transparency

Philosopher Slavoj Žižek notes

Here are two telltale words: abstraction and control. To manage a cloud there needs to be a monitoring system that controls its functioning, and this system is by defi nition hidden from users. Th e more the small item (smartphone) I hold in my hand is personalised, easy to use, "transparent" in its functioning, the more the entire setup has to rely on the work being done elsewhere, in a vast circuit of machines that coordinate the user's experience. Th e more our experience is non-alienated, spontaneous, transparent, the more it is regulated by the invisible network controlled by state agencies and large private companies that follow their secret agendas.

(Žižek, 2013)

In essence, if the control is not in our hands, then the control is elsewhere. In a talk on the subject of transparency, entrepreneur and politician Peter Sunde (2015) also pointed to the relationship transparency has to power:

...if you do something, or the state does something that aff ects other people, you need to be transparent about it. It’s about power. Th e more power you have, the more transparent you need to be ... Th e problem is that companies are becoming the new state, but we have not really forced companies to be transparent.

(Sunde, 2015)

An IxD perspective on transparency is badly needed.

3. Design approaches

Th is thesis project applies a hybrid critical, political and activist lens. It draws inspiration from critical design, adversarial design and, perhaps the less common: seamful design.

3.1 Seamful Design

Seamful design has its roots in Xerox PARC Chief Scientist

Mark Weiser's notion of ubiquitous computing "to make a computer so embedded, so fi tting, so natural, that we use it without even thinking about it." (Weiser, 1994)

10

Computing is now truly ‘post-disciplinary,’ central to, and re-articulated through the rhetorics of culture, economics, and politics. However, contemporary visions of technological development increasingly focus on invisibility and ‘seamlessness.’ Invisibility is now often framed as both an inevitable and desirable quality of interface technology. (Arnall, 2014, p.104) Perhaps this seamlessness has been granted too much

precedence? Matt Ratto (2007) highlights the agency and control issues brought on by seamlessness. He states

"[...] by hiding the seams between systems, we are not allowed the ability to decide when and how we engage with them [...] without knowledge of the boundaries, users may be left with little ability to negotiate the moments of switching between active and passive roles." (Ratto, 2007, p.25)

An active role, or as this thesis project refers to as designing for deliberate action, or a passive role —deliberate non-action can and are designed for. Kristina Höök and Jonas Löwgren describe seamful design as

"a counterreaction to the prevailing strive for seamlessness as the golden standard for all kinds of connectivity, network coverage, positioning information and suchlike. In seamful design, moving between different networks, glitches in the coverage of the positioning system, or moving from one media tool to another will not be seamlessly hidden from users' view, but, instead openly exposed so that users could not only understand what is going on but even take advantage and make use of the seams in their activities." (Höök & Löwgren, 2012, p.8) Chalmers, MacColl and Bell (2003) presented examples of seams involving the characteristic of uncertainty, associated with sensor technologies and imperfect transformations between heterogeneous tools and systems. The authors argued for using an example of seams, related to system's flaws, as a deliberate "policy of design i.e. rather than fighting against uncertainty, we discuss the deliberate choice to present and use it" (ibid., p.14). Chalmers et al. suggest that

"deliberately affording knowledge and use of seams need not be a defensive choice or merely pragmatic — making a 'design feature' of a flaw — but a positive and empowering design option." (ibid.) Bell et al (2006) described their method of seamful design as

"Exploiting characteristic limits and variations that are apparent in use and interaction, and which contribute to users' practical understanding and use of a system as they experience it in their everyday life." (ibid, p.420) Their location-based game Feeding Yoshi is a seamful design example. When a player moved around the city with their PDA, it continually scanned for the presence of wireless networks. This game expanded the idea of a seam through exploiting whether the wireless network is open or secure (Fig 3.1). People plant fruit for a Yoshi in the wireless network hotspot they are connected to, the fruit grows and allows them to harvest it at a later time.

"This is interesting in terms of highlighting important debates around this technology" [...] "indirectly, players were learning about wireless networks' range, distribution

and access control mechanisms, accommodating and appropriating from the perspective of the game rather than from formal education." (ibid.)

Inspired by the work of Bell et al., this thesis project argues for expanding the notion of seams, or a system's flaws, opening it up to include spaces in existing infrastructure where people can experience vulnerability: vulnerable InfoSec interactions. This is with the aim to counteract the agency and control issues brought on by giving seamlessness precedence, as highlighted by Matt Ratto.

3.2 Critical Design

In 2001 Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby described critical design by stating

"...design that asks carefully crafted questions and makes us think, is just as difficult and just as important as design that solves problems or finds answers. [...] Questions must be asked about what we actually need, about the way poetic moments can be intertwined with the everyday and not separated from it." (Dunne & Raby, 2001, p.58)

Fig. 3.2 Words of a Middle Man (Volker, Steinlehner & Teuteberg, 2012) [video still] source: http://middleman.cube2.de/

Words of a Middle Man (2013) is a critical design project by Jeremias

Volker, Christoph Steinlehner and Lino Teuteberg. It explores digital privacy in real spaces, the role of the wireless router and how to tell stories with network traffic (Fig 3.2). The authors shift the router to the forefront socially by giving it its own voice by giving it a screen to broadcast human natural language and allowing it to form a character with its own presence and identity.

The router displays activity of people and objects on the network, such as ‘Michael learns on wikipedia’, ‘LaserJet 3600 is looking for a job’ and ‘Hey Michael, facebook again?’. They point out how the router through this becomes an active body in a social space. Furthermore the authors emphasize how the wireless router is the central place where the virtual world and the physical world meet in one single object. The authors are identifying an interesting seam, in the role of the router, which perhaps could be looked at through the lens of seamful design.

The authors also spoke of purposefully selecting the material of the router to retain the classic qualities of a router, with a dull plastic case. As Ylva Fernaeus and Petra Sundström (2012) have argued, materials play an important part in interaction design research. Indeed the way one chooses Fig 3.1. Screens from the location-based

seamful design game Feeding Yoshi (Bell et al., 2006). Plantations (left) are detected open wireless access points and Yoshis (right)

12 13 to materially model the router would heavily influence its identity and how

it would be perceived with its screen displaying words of a middle man. The interplay of Words of a Middle Man's more conventional material form and its newer, more socially active performing role stand in stark contrast.

3.3 Adversarial Design

Carl DiSalvo (2012) proposes Adversarial design as design which examines political qualities and potentials through the lens of agonism:

"Themes of agonism emphasize the affective aspects of political relations and accept that disagreement and confrontation are forever ongoing" [...] the most basic purpose of Adversarial Design is to make these spaces of confrontation and provide resources and opportunities for others to participate in contestation." (DiSalvo, 2012, p.5)

An example is Natalie Jeremijenko's (2002-present) project Feral Robotic

Dogs, which features hacked robotic dogs used to detect pollution. They

are released as media events to detect and act on toxicity in everyday surroundings, evoking and engaging in political issues. (Fig 3.3)

3.4 Related work

Making intangible processes more tangible was of interest for this research project. This section presents related work which served as inspiration and helped to situate the work.

3.4.1 White Box

Automato.farm's White Box (Fig 3.4.1) explores and

Fig. 3.4.1 White Box (automato.farm, 2016) Fig 3.3 Hacked Robotic Dogs from Natalie Jeremijenko's Feral Robotic dog project. source: https://www.nyu.edu/projects/xdesign/feralrobots/

Fig 3.4.2. Data Dealer online game [video still] source: https://datadealer.com

Fig 3.4.3 The Internet Phone (Frostå, Hunkeler, Obel & Zhou, 2017)

addresses the materiality making up the lack of agency experienced by people in a smart home.

“We think of the white box as a product that it’s fictional, but real enough to communicate new needs and challenges that ‘smart’ will bring to our homes. As designers, we have to move deeper in machines to understand the new mechanisms that smartness and connectivity bring, we need to design new interfaces to avoid people turning into unaware inputs.” (automato.farm, 2016) 3.4.2 Data Dealer

Data Dealer (2013) is an online game that allows you to “Become Larry Page, Mark Zuckerberg or even Edward Snowden, as you control the flow of data — and the price tag that comes with it”(Fig 3.4.2). It is a nonprofit project aimed at raising awareness about personal data and digital privacy issues by placing you in the active role of being a data dealer. 3.4.3 The Internet Phone

The physical computing project by Isak Frostå, Sebastian Hunkeler, Jens Obel and James Zhou (2017) is a project framed by the question 'What if you could experience the Internet by using a screenless and physical interface?' In this project you can experience the Internet in a novel and physical way by calling up websites using an old rotary phone and listening to them via numbers you find in a printed ‘cyber directory’. (Fig 3.4.3) The aim here was to 'demystify the processes of the Internet by allowing people to physically go through the process of connecting to a website (ibid.)'. 3.4.4 Obfuscation: A User's Guide for Privacy and Protest

In 2015 Finn Brunton and Helen Nissenbaum published a book positioned as a user's guide for privacy and protest. In this book the authors identify the notion of 'obfuscation' and define it as 'the deliberate addition of ambiguous, confusing, or misleading information to interfere with surveillance and data collection'. (Brunton & Nissenbaum, 2015, p.1) The book is a collection of case samples, along with discussion of why obfuscation would be necessary, justified and when it may be appropriate. However, for a book meant as a user's guide to protest, it has rather complacent definitions in relation to privacy such as "privacy does not mean stopping the flow of data; it means channeling it wisely and justly to serve societal ends and values "(ibid.), which is a statement which makes one question whose ends and values in society? This thesis project argues that at times the flow of data from unaware people does indeed need to be stopped and in fact specifically for privacy/human rights reasons. Another troubling statement in the book about privacy by the authors is:

“privacy is a complex and even contradictory concept, a word of such broad meanings that in some cases it can become misleading, or almost meaningless" (ibid, p.45)

Implying that privacy is meaningless is particularly grating. Once again it makes one wonder to whom privacy is ever meaningless, considering it has been defined as a human right (section 2.5).

The authors conclude by stating that “we have only begun the work by naming, identifying and defining. This book is a collection of starting points for understanding and making use of obfuscation. There is much more to be learned from practice, from doing" . (ibid, p.97) It seems the book authors were right in saying there is more to be learned from practice and doing. A well written counter 2017 book

14 15 review by Rashid al-Din Sinan also observes how the authors “present

a vehement defense of obfuscated state surveillance via ideological normalization, it further does so through the spreading of technical misinformation in the form of oversimplification and omission, thus effectively sabotaging and neutralizing users should they actually deploy the case studies describe in the text [...] leaving out potential pitfalls of the various case studies, Brunton and Nissenbaum endanger the reader, presenting potentialities which amount to misinformation based on omission”. (al-Din Sinan, 2017, n.p.) al-Din Sinan finishes the critique by calling out that it "is thus doubly dangerous, both in its normative function as a piece of state-sponsored ideological propaganda presenting mass government surveillance as a legitimate and positive aim, and as a compendium of technical misinformation, with both operations masquerading under the subtitle of what the text is decidedly not: a user’s guide for privacy and protest." (ibid.) The critique of this book highlights and supports the need for more

doing in the area of designing for awareness. It points to a need for

more hands-on experiences in designing ways for boosting people's possibilities for deliberate action (or non-action) in the area of InfoSec. 3.4.5 Find My _________

With a strategy to identify "under-addressed anxieties beneath the surface and at the margins of mainstream HCI, IoT and AI research", Pierce & DiSalvo (2018) address what they call 'network anxieties'. The authors use a technically grounded design metaphor they call 'Edge Cases' in a speculative design called Find My _________. Drawing from engineering jargon, an edge case is an 'overlooked or underestimated case occurring at extreme operating parameters' (Pierce & diSalvo, 2018, p. 5), e.g. a driverless car with a poorly calibrated sensor activating its breaks for

Fig. 3.4.7 The Bronze Key (Kozel, Gibson & Martelli, 2018) is an art installation consisting of three material components: (1) The Plaintext—sonified motion capture data from a Virtual Reality gesture making sequence (left)* on cassette tape (middle), (2)

The encryption key—a 3D printed bronze shape produced from the motion captured gesture (top right*), and (3) The Ciphertext—a printed book displaying the scrambled motion capture data (bottom right*). *image source: gibsonmartelli.com Fig 3.4.5 Find My _______________

a billboard depicting bicyclists. The authors shift the term Edge Case from an engineering problem solving space to treat it as a social and experiential phenomenon and reconfigure center/edge relations, to reveal its actual proximity. (Fig 3.4.6) Using creepy use cases on Apple's Native app

Find My Friends 'foregrounds another troubling center/edge relation: that edge cases lie closer to the center than they might initially appear'. (ibid., p.6) This could be considered a call-to-action to design for awareness and design for action/non-action as a way to contribute countermeasures and augment agency.

3.4.6 The Bronze Key

Kozel, Gibson and Martelli (2018) contributed performative re-materi-alization of bodily data in the form of an art installation. This critical art intervention addresses the archiving of bodily data and opens the scope for poetic and practical forms of encryption (Fig 3.4.7).

3.5 Design takeaways

PerformativityThere is a performative quality to The Internet Phone, Data

Dealer and The Bronze Key, which helps materialize abstract

technical processes such as calling up a website, connecting to a router or performing an encryption using bodily gestures. Tangible materialities

Hacked robot dogs, a plastic router case with thick antenna, thick paper books, a rotary phone, 3D printed bronze keys, reel to reel tape player with headphones, buttons and knobs are tangible materialities to be observed in several of the works (Feral Robot Dogs, Words of a

Middle Man, The Internet Phone, The Bronze Key, The White Box).

Signaling a lack of agency

The fact that there is book published with intent to guide a protest in relation to privacy, and a research paper dedicated to 'network anxieties' signal a lack of agency and a need an approach to possibly help build hands-on awareness and boost possibility for deliberate action (or non-action) for a broader range of people. In summary the design approach for this thesis project is a seamful design approach, identifying InfoSec vulnerabilities as seams. The work draws from notions of critical design, aiming to ask questions to make us think about what we need and about poetic moments intertwined with our everyday (section 3.2). Drawing from aspects of Adversarial Design, it aims for political and activist qualities with a desire to make hands-on spaces of contestation for a broader spectrum of participants (3.3). This thesis project crafts a methodology that takes concrete, real world actions and our bodies being in the middle of this and argues for integrating a seamful design approach with embodied interactions and a strong performative component.

16 17 Fig 4. Design process

4. Design Process

This thesis project falls under the research through design (RtD) orientation (Archer 1995; Frayling 1993, Zimmerman et al. 2007). RtD is where

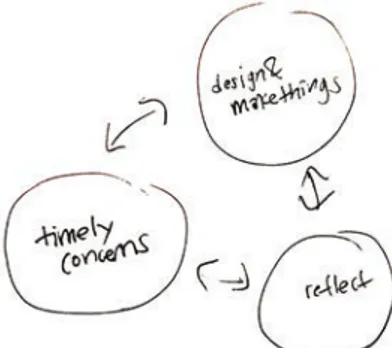

"design practice is brought to bear on situations chosen for their topical and theoretical potential, the resulting designs are seen as embodying designers' judgements about valid ways to address the possibilities and problems implicit in such situations, and reflection on these results allow a range of topical, procedural, pragmatic, and conceptual insights to be articulated" (Gaver, 2012, p.) This process is of a drifting nature in line with what Johan Redström describes (2011) in his Notes on Program/Experiment Dialectics, and what Peter Gall Krogh, Thomas Markussen and Anne Louise Bang (2015) touch on when attempting to model a selection of PhD thesis design research experimentation processes. As Krogh et al. point out, drifting ''is a quality measure as it tells the story of a designer capable of continuous learning from findings and of adjusting causes of action" (ibid., 2015). For this thesis project the process can be illustrated as moving back and forth in both directions between three modes: observing timely concerns, design prototyping and reflecting. (Fig 5)

'Design Prototyping' in this thesis project refers to Stephanie Houde's and Charles Hill's definition of prototyping, where prototyping is defined extremely broadly as "any representation of a design idea, regardless of medium" (Houde & Hill, 1997). 'Reflecting' refers to Donald Shön's reflection-in-action, a reflective conversation with the situation (Schön, 1983, p.76).

The process involved five phases in total. First, two initial phases (Privacy

Rapist and Hen-in-the-middle), followed by an interview phase with an

InfoSec practitioner and researcher (Nikita Mazurov). This interview phase helped ethnographically ground and deepen the ideas for two additional phases (Tangible Encrypted Email and Placebo Sleeve Inversion).

Phase 1

4.1 Privacy Rapist

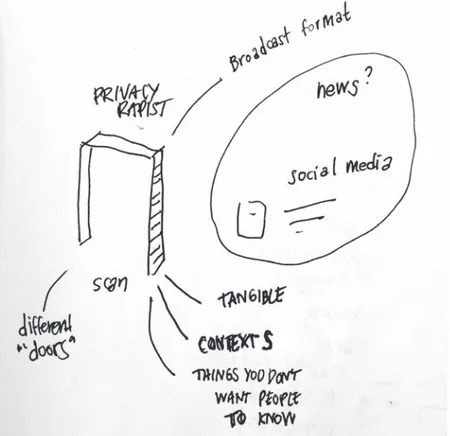

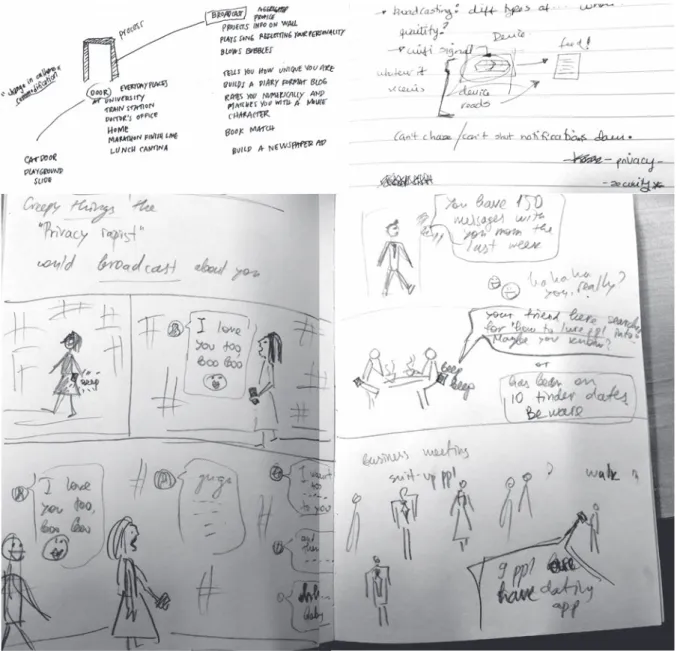

4.1.1 ConceptIt began with a concept: Privacy Rapist (Fig 4.1.1), which is meant to materialize, and raise awareness of, the lack of agency people have in the Surveillance Capitalism (Zuboff, 2016) culture of today. It is meant to bring to the fore and materialize the process of unknowingly sharing information over time as we walk around in urban landscapes with our devices, often as a default with no way to opt out, at least not without a serious amount of effort.

This concept is based on the embodied interaction of physically walking through a doorway. A doorway was selected because interacting with a door frame is an example of a daily mundane default interaction. Walking through a doorway is the default way to enter and exit a room or space. Alternatively you could enter and exit a room or space through a window perhaps. However, that would be considered out of the norm and certainly not as easy, especially if you are not located on the first floor of a building. Walking through the doorway is meant to serve as an example of a daily interaction which would be tricky to opt out of. Generally if you want to enter a building, you need to pass through a doorway of some kind. Privacy Rapist is not a stand alone door frame, it is layered onto an existing doorway in such a way that you would not initially notice it being there. Privacy Rapist is a door frame which scans your body (e.g. your face, height or weight) and your connected (Internet) or broadcasting devices (e.g. Wi-Fi, Bluetooth or BLE) as you pass through it. Over time, as you pass through the door frame numerous times,

Privacy Rapist builds up a profile on you and aggregates this

information with any other publicly available information it can find

18 19 online in order to form a relationship with you. This relationship is

then broadcast by Privacy Rapist, perhaps through external social media channels, but also locally in the nearby physical room or space through projections on the wall along with sound near the Privacy

Rapist doorway, for people passing by to openly see and hear.

4.1.2 Method

The method used for this prototyping is pen and paper sketching. Materials

-Pen -Paper -Our bodies

4.1.3 Implementation

A first initial rough sketch of the concept was sketched by the author, to introduce the concept.

A pen and paper sketching session was held by inviting two fellow interaction designers Raya Dimitrova and Roxana Escobado, in order

Fig 4.1.2 Privacy Rapist sketching session on different types of doors, broadcast formats, and creepy things it would share about you (Carlsson, Dimitrova and Escobado)

to further explore where these Privacy Rapist doorways could reside and who would interact with them, what information the Privacy

Rapist could potentially broadcast and in what formats (Fig 4.1.2).

4.1.4 Design takeaways/ Reflection

Insights from this experimentation were that with the time and resources at hand for this thesis project, it was as much and maybe more about identifying and materializing a vulnerable process in every day life and raising awareness about the lack of agency than it was about actually building this as a tangible intervention. The doorway, as a symbol, was found to be both helpful in its concreteness as well as a rich design metaphor to explore further in terms of entering into situations (or not), informed consent, daily default interactions and lack of agency.

When considering different door alternatives, both in form and placement, the possible participatory pool widened. Children and pets surfaced as also having their own doors, such as cat doors or playground slides. Discussions also landed on how metal detectors, which already exist and are put in use at airports and schools are eerily similar to the concept of Privacy Rapist in the sense that you are forced to go through in order to gain admittance to a certain space. Sketching scenarios was helpful in surfacing possible situations of embarrassment. E.g. scenarios where sketched with Privacy Rapist announcing how many people in the room are on a certain mobile dating applications, how often your mom has called you, what you have been typing into a search engine lately or broadcasting personal messages from your lover for everybody to see.

Some of the questions that surfaced were: what are we not willing to share and how do different contexts allow for different levels of (un)willingness to share?

20 21 Phase 2

4.2 Hen-in-the-middle

The performativity of this prototyping was centered on inserting my own body into the process. Therefore I am using the personal pronoun to describe it.

4.2.1 Concept

It began with a concept: Hen-in-the-middle, which is meant to materialize, make tangible and criticizable, the vulnerability of our data, when interacting with a Wi-Fi network. I am doing this by performing active Man-in-the-middle-attacks (section 2.4.3). Because I am inserting myself into the process and I do not identify as a man, I am using the Swedish gender-neutral pronoun: 'hen', resulting in the concept name: Hen-in-the-middle (HITM).

I have been intrigued by the concept of Man-In-the-Middle (MITM) attacks online, where one inserts oneself into a Wi-Fi network,

impersonates a network gateway and reroutes the traffic as described in more detail earlier (section 2.4.3). The reason I find this InfoSec concept fitting for this thesis project is that MITM techniques can be used to either eavesdrop on network activity and/or actively manipulate it while in data is in transit. Eavesdropping on and manipulation of data, being unaware of who you are communicating with are themes of vulnerabilities apparent in the Surveillance Capitalism culture of today. For this prototyping I was specifically interested in the latter, i.e. not in passive eavesdropping but in an active attack involving manipulation of data in transfer. 4.2.2 Method

Wishing to pull in performance-based methods, after having identified a performative quality in inspiring related works, I found that a good precedent to look at was Sarah Homewood's second year Malmö University Master's Thesis entitled Turned on/ Turned off:

Investigating the Interaction Design Implications of the Contraceptive Microchip. In it, Homewood used performance-based speculative

design methods to “bring futuristic concepts into the present so that they were tangible and critizable". (Homewood, 2016) Similarly, what I was doing was revealing the vulnerabilities in current scenarios, in order to render them tangible and critizable, through performance-based seamful design methods.

Additionally Homewood states "within interaction design, performance is a strong method to use when understanding interactions where emotional shifts and internal processes are at the focus point"

Through Homewood, I also found performance studies scholar Richard Schechner's thoughts on opening up performance to not only belong on a stage, but in our everyday lives as well. He states that we effectively perform our entire lives (Schechner, 2003 [1988]). This applies to this second design prototyping phase, as I am inserting myself into a process as a performer situated in every day life activity, surfing the web on my laptop. Eric Dishman stating that “tools of situated, embodied criticism

enable us to release, albeit temporarily and in limited ways, the shackles of our current subjectivities" (Dishman, 2002, p.244) also appears of relevance when inserting my bodily data into this process, performing different roles from different perspectives.

Fig 4.2.1. When surfing to the Malmö University website during the Upside Down Internet HITM attack I experienced that all requests for images were being intercepted by an attacker (also me) running a script actively flipping all images upside down. Videos did not flip.

22 23

opens a lot of opportunities to interpret, use, imagine, and consider the physical space in different ways" (Jacucci, 2015, p. 350) supports designing for awareness of a seam, when defined as a space where physical and virtual worlds meet in terms of bodily data, and our capability for awareness and deliberate action or non-action in this space. 4.2.3 Materials

-Kali/Linux virtual machine

-MITMf, a python Man-in-the-middle framework by Marcello Salvati (byt3bl33d3r, 2018)

-Mac Laptop

-Wireless network at my apartment -Router

-Smart phone (used as camera) -My body

-Digital images of myself 4.2.4 Implementation

Hen-in-the-middle, took place at my apartment using my laptop and my home network.

Fig. 4.2.4 HITM (Virtual machine as active attacker) inserted on home network

I installed a Kali/Linux virtual machine onto my Mac laptop along with a python tool called MITMf(byt3bl33d3r, 2018) made specifically for MITM attacks. The plan was to perform an active Hen-in-the-middle attack on myself, using the python tool from the virtual machine. After I set up the virtual machine I started browsing online, using my Mac Laptop, on my local wireless network (Fig 4.2.4). I performed multiple types of attacks on myself. Shown below are two types of these HITM attacks I performed: (1) Upside-down Internet

In this attack the requested website images are intercepted and flipped upside down. I.e. the attacker runs a script which takes all web image requests from the website the victim is browsing to and actively flips the images upside down in the network stream. (Fig 4.2.1-4.2.2) (2) Html injection

Here the HITM is actively manipulating the images shown to victim. When the victim surfs to a website and said website requests images, other images of choice are injected in their place. In the experiment I injected images from a folder of a series of randomly selected images of my body in different locations, positions and emotional states. (Fig 4.2.3) Example images (Fig 4.2.5 - 4.2.8) show what I experienced

when browsing with the laptop to various websites. Note that the requested website images were actively swapped out, Fig 4.2.3 Series of images of my body which were html injected through an active Hen-in-the-middle (HITM) attack.

Fig 4.2.5. Visiting the Acne studios website, seeing a HITM html injection

through HITM html injection, with my previously mentioned image folder of choice, containing images of my body. 4.2.5 Design takeaways/ reflection

For the Upside-down Internet HITM attacks, there is a performativity within embodied interaction present. Disorientation is an embodied quality. Here, the data is disoriented and I am accessing it, this disorientation, through the body. There is a performative parallel disorientation. I am feeling disoriented and the data is disoriented. My body is in the middle of what is going on with the visuals. With the Html Injection HITM attacks there was a similar embodied disorientation. It was jarring to see how such well known sites, such as e.g. the BBC, IKEA and local public service transportation service Skånetrafiken, allowed me to inject other visual content so easily with readily available tools. Most of the injected photos landed in a rotated fashion, which was disorienting and in a way simply made it clearer that they did not belong there. Landscape format photos would have produced a more subtle swap. Nevertheless, I found that experimenting with actively changing the content and inserting myself into the process makes the possibilities and vulnerabilities of a HITM attack easier to understand. As mentioned earlier these were just two HITM variants, the tool offered even more options. Still, these attacks retain a level of abstraction when experienced flatly on the screen. Further iteration of this prototyping could be to tie tangible and embodied interaction and performative interactions or interventions to these HITM attacks. What if you had a tangible ‘thing’, e.g. a large square box, which when

24 25 Fig 4.2.6 Visiting the BBC website, experiencing a HITM html injection

you turned it over, would activate an Upside Down Internet HITM attack on your local network? Or what if one side of this block featured a photo, which when placed a certain way would perform a HITM Html Injection of that photo on the network? This may be an avenue worthwhile to further explore to push a HITM attack towards being more concrete and allow people to become more aware of vulnerable interactions as technology seams and feel the vulnerability of their (bodily) data. Because of HITM's gender neutrality, and this concept being aimed at a wide public, further work could possibly give a nod to Shaowen Bardzell's work on Feminist Utopianism (Bardzell, 2018, p. 20),

specifically 'to the tactic to attend to the bodies of who we are concerned

(ibid.)'. Incorporating these tactics is beyond the scope of this thesis project, however further work in this direction may be of interest.

Fig 4.2.7 Visiting the IKEA website, experiencing a HITM html injection

26 27 Phase 3

4.3 Interviewing Nikita Mazurov

To ground this thesis project ethnographically, an InfoSec practitioner/ Post doc researcher, Nikita Mazurov, was interviewed. Where InfoSec specialists commonly have a background in computer science, Mazurov's background in critical theory and culture studies coupled with practical InfoSec knowledge offers a unique, more holistic perspective. The aim was to investigate what current topics Mazurov would find relevant to engage with, where one finds sources on these topics and their view on how interaction design possibly could contribute to InfoSec. 4.3.1 Method

A casual, semi-structured interview was deemed suitable. The interviewer had a clear general agenda to touch on the topics above, but the

discussions were left open-ended enough for the interviewee to express themselves in their own way and lead the conversation in any direction. 4.3.2. Materials

-smart phone (to record)

-transcribing app (to control speed of sound) -laptop (to transcribe)

4.3.3 Implementation

The 75 minute interview took place at Malmö University. It was recorded on a smart phone and manually transcribed afterwards with the help of a transcription software, to more easily sync the speed of typing with the recorded conversation. Time stamps were inserted at times when the material was deemed especially rich in regards to the thesis project. 4.3.4 Design takeaways/ reflection

This interview (see Appendix A) helped deepen ideas for the proceeding design prototyping phases:

-Privacy is a collective notion rooted in the community standing united from the bottom up in safeguarding the rights of the disadvantaged from the advantaged -Using the analogy of second hand smoking to illustrate how privacy is embodied—your lungs are intruded upon—social, and affects everyone around you.

-Small interventions to make up for the fact that there is no accountability -Thin slices — to not overwhelm yourself or

others with information overload -Speaking for accessibility and openness -Speaking against victim-blaming in InfoSec

-A need for a privacy settings icon and to bring privacy settings to the fore -An idea for a tangible email encryption workshop

-The 'don't care mentality' as a manufactured top

down construct serving the powers at be -Google Dorking as a research method

Phase 4

4.4 Tangible email encryption workshop

The two last phases of the design process involved a workshop and probe (section 4.4 and 4.5) and were temporally combined. The workshop (section 4.4) aimed to spark a debate with the participants on the topic of privacy and data encryption in order to set the stage for the probe (section 4.5). 4.4.1 Concept

This performative tangible encrypted email workshop sprung from the interviewing phase with Nikita Mazurov ( see full transcript: Appendix A, p.40). This workshop could be considered a variation of the second prototyping phase. It involves a performative Hen-in-the-middle (HITM) attack, with the aim of getting people to physically grapple with the issues of encrypted vs. plaintext messages and an embodied HITM attack. 4.4.2 Method

This workshop employed performance-based seamful design, inspired by performance-based speculative design as introduced by Sara Homewood in her second year Malmö University Master's thesis project (Homewood, 2015, p.43). Homewood used

"performance-based speculative design to creative future use scenarios"— I use it to reveal vulnerabilities in current scenarios. The workshop was also inspired by how Ann Light uses

performative methods to democratize design of technology (Light, 2011). Instead, I am using performance to allow for agency and for people to take control of their own data. Additionally this session drew on how Eric Dishman exercises performance "in order to counteract this hype-driven tendency to focus on the technological props at the expense of the social actors who are supposed to use them. Performative ways of knowing, thinking, and critiquing provide counteractions to the global

28 29 Fig 4.4.1 Mailbox, two 'plaintext'

letters,'encrypted' letter with lock and keys.

visions imposed upon us" (Dishman, 2002, p.235) as this workshop questions why we are not sending encrypted messages by default. Materials -A4 paper -C5 envelopes - cardboard mailbox - googly eye - pen

- plastic pouch with zipper -metal lock with 3 keys 4.4.3 Implementation

Six participants were recruited for this workshop + probe. They were three interaction design students, two computer engineering students and one illustrator. All were current or former classmates of the author, except for one, who was a significant other of one of the participants. This short tangible encrypted email session workshop session was run by the author acting as moderator/performer. The participants were divided into two groups. Half of the participants were asked to volunteer to write a letter (using a pen, an A4 paper and an envelope)and half of the participants were meant to act as recipients of these letters. Two people would write 'regular' letters and one person would write an 'encrypted' letter involving locking the letter into a plastic pouch with a physical lock, and handing a key to the recipient. To keep focus a 5 minute alarm was set. The 'writers' were told to drop their finished letters in a mailbox (Fig 4.4.1), which was marked 'contents will not be read by anyone'. Once five minutes had passed, the moderator/performer opened up the mailbox, took out and opened the two unencrypted 'plaintext' letters, photographed them and projected them on the wall, one at a time for all to read, saying

'Sure, it says that no one will read it, but I did it anyway, because who is going to stop me?'

The 'encrypted' letter was not opened as the moderator/performer stated that although it was possible to open, it seemed like a hassle to get the lock opened or to find something to cut the plastic pouch. All this to get the participants thinking about who gets to see what data and their comfort levels regarding this.

Following this, a discussion session was held, for feedback on how to improve the workshop and to discuss email encryption in general. 4.4.4 Design takeaways/ reflection

It was remarkable how uncomfortable the participants initially were with writing a letter using pen and paper. Or perhaps not remarkable at all. Seeking to make something tangible how much of a rarity it is to write a handwritten letter with pen and paper had not been considered. Additionally the participants with the 'plaintext' letters did not seal or address their envelopes before placing them in the mailbox. This resulted in the performance being much less dramatic when the moderator/performer opened, read and posted the letters than planned. It also revealed that the letter writers seemingly had no issues with someone reading what they wrote. One of them also seemed to have missed that the letter was supposed to be written to a person in the room, with the aim to allow all participants

to feel involved. One letter was written to a generic 'Bud'. The 'encrypted' letter was locked up, but the participant did not address it to anyone in the room. Instead it was simply titled 'secret' in capital letters (Fig 4.4.1). The participant also did not share the key to the encrypted letter with anyone in the room. It appeared as if the participant was making a statement by locking up the letter and not sharing the key even with the moderator/performer. Later, when asked about the key, the participant stated they had meant to give the keys to the author after the session, but simply forgot the keys in their pocket. If anything this points to the complexities of key management, an vulnerable area within encryption worth further explorations. Because the session did not run as planned in many ways, I asked for feedback on how to improve the workshop. Interestingly this group thought that a chat being logged and projected would be more relevant to their everyday. Email was apparently not used by them much. They also mentioned that if the contents had been more sensitive, they would have felt more violated. The session successfully provoked a discussion of data privacy and encryption. It served as a lead in to stage and introduce the Placebo Sleeve Inversion probe.

Phase 5

4.5 Placebo Sleeve Inversion

4.5.1 ConceptThis fifth prototyping phase involved a variation on the sketching of first prototyping phase and revisits the questions generated from the Privacy Rapist sketching:

What are we not willing to share and how do different contexts allow for different levels of (un)willingness to share?

Relating back to the Privacy Rapist, this phase aims to dig deeper into what people do not want to share in their everyday lives. This relates to the idea of designing to support action or non-action. 4.5.2 Method

This prototyping phase is drawing on sketching and the performativity, still contributing to the overall approach of seamful design. A combined placebo and cultural probe, the Embodied Imagination method (Hansen & Kozel, 2007) was selected for how it allows "for an elastic performance space containing participants, their lived lives, the analogue object and us (the researchers) allowed for the embodied imagination to flow (ibid.)". This space, public dreaming, is a term from performance studies coined by Richard Schechner. It is the state that occurs at the cross-sections of the domains of "the public, the private and the secret." (Schechner, 2003, p.265) With this method the project space is brought to the participants , as opposed to the participants being in controlled surrounding. It builds on the cultural probe method (Gaver & Palenti,1999) and the designed and staged qualities of the Placebo Project (Dunne & Raby, 2001,p.75). Bringing the project space to the participants results in the design inserting itself into a participant's life, making the participant a performer

30 31 Fig 4.5.2 Participant playing with googly eye after it popped off the notebook band (left). Participant wearing their selected sleeve (middle) The

instructions were an exact copy of the Placebo Sleeve (Hansen & Kozel, 2007) but negated by inserting the words non and not (right). in their own life. This with the premise that 'the merging of technologies and bodies need not be on a spectacular or dramatic level, it can occur on a pedestrian, daily level which emphasizes not just the practice of everyday life, but the performativity of every day life', (Hansen & Kozel, 2007, referring to Amin & Thrift , 2002 and de Certeau(2011[1984]). 4.5.3 Materials

- Fabric

- Sewing machine - Scissors

- Needles & thread - Foam packing material - Googley eyes - Glue - Paper notebooks - Rubber bands - Pens 4.5.4 Implementation

Fabric was sourced from scrap piles in the author's social circle. Materials used for the sleeves were selected based on softness, stretch and to provide some variety in color for participants to choose from. Twelve sleeves of varying lengths (3-20 cm) were sewn using the different fabrics using a sewing machine. The aim was to allow the participants a chance to select a sleeve more to their own liking, rather than being handed a generic version. Echoing the original Placebo Sleeve, a small lump made of a piece of squishy foam packing material was inserted into a little pocket and sewn onto the sleeves to symbolize technology, maybe a button or a tiny extended bodypart. In the interview with Nikita Mazurov (Appendix A), he mentioned that privacy settings and icons tend to be too deeply buried. Therefore an eye icon was placed prominently on both the sleeve and on a rubberband wrapped around the accompanying notebook. This was done to signal Fig 4.5.1 Materials involved

![Fig. 3.2 Words of a Middle Man (Volker, Steinlehner & Teuteberg, 2012) [video still] source: http://middleman.cube2.de/](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/5dokorg/3969835.77763/16.892.76.295.110.667/words-middle-volker-steinlehner-teuteberg-video-source-middleman.webp)

![Fig 3.4.2. Data Dealer online game [video still] source: https://datadealer.com](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/5dokorg/3969835.77763/18.892.106.322.106.283/fig-data-dealer-online-video-source-https-datadealer.webp)