“I DO NOT GET THE WORDS OUT,

IT ALL JUST SOUNDS WRONG.”

A qualitative study of the causes of language anxiety among upper secondary EFL students in Sweden,

and their teachers’ strategies to decrease it

SUSANNE BARAKAT

School of Education, Culture and Communication Supervisor: Elisabeth Wulff-Sahlén

Degree project ENA314 Examiner: Thorsten Schröter

ABSTRACT

This study examined the possible causes of language anxiety among three upper secondary school students in Sweden. In addition, the study explored the strategies used by said students’ English teachers to decrease language anxiety in their students. The data was collected by using semi-structured interviews and analysed through content analysis. The analysis showed that the main causes of language anxiety were four significant factors: communication apprehension, test anxiety, fear of negative evaluation, and classroom

environment. In particular, the study showed that all the students felt more anxious when they were uncomfortable with their surroundings and when they felt under pressure to perform. Negative evaluation from other students affected their confidence level, which was another crucial cause of anxiety. All the students expressed that the teacher's approach had a significant effect on their anxiety level, and all the teachers claimed to adapt their English-speaking activities to each student’s needs. A general conclusion is that the students’ anxiety varies depending on the English-speaking activity and their teacher’s approach, which was acknowledged by the teachers.

Keywords: English, language anxiety, strategies, EFL students, willingness to communicate,

Table of contents

1 Introduction ... 1

1.1 Aim and research questions ... 2

2 Background ... 2

2.1 The Swedish curriculum for upper secondary school ... 2

2.2 Language anxiety ... 3

2.3 Causes of language anxiety ... 4

2.3.1 Communication apprehension ... 4

2.3.2 Test anxiety ... 5

2.3.3 Fear of negative evaluation ... 5

2.3.4 Classroom environment ... 5

2.4 Willingness and unwillingness to communicate ... 7

2.5 Code-switching ... 7 2.6 Teachers’ strategies ... 8 3 Method ... 9 3.1 The participants ... 10 3.2 Data collection ... 11 3.3 Data analysis ... 12 3.4 Ethical considerations ... 13 4 Results ... 13

4.1 Self-esteem and Self-confidence ... 13

4.1.1 The students’ perceptions of self-esteem and self-confidence ... 13

4.1.2 The teachers’ perception of students’ self-esteem and self-confidence ... 15

4.2 The students’ opinions of speaking in class and in groups ... 15

4.3 The students’ opinion on the English teacher’s role in the classroom ... 18

4.4 The teachers’ strategies to reduce language anxiety among their students ... 19

5 Discussion ... 23

6 Conclusion ... 25

6.1 Future research ... 26

Reference list ... 27

Appendix 1: Interview questions for the teachers ... 29

Appendix 2: Interview questions for the students ... 31

Acknowledgments

Firstly, I would like to thank my supervisor Elisabeth Wulff-Sahlén and examiner Thorsten Schröter whom I have received a great deal of valuable feedback and assistance from. I would also like to give a huge thank you to my family that has supported me throughout this essay. Finally, I would like to say that I could not have completed this essay without the support and love of my dear friends Merve and Antonette, who have been there for me during all the ups and downs throughout the writing process of this essay.

1 Introduction

The English language plays an increasingly significant role in Swedish society and is often used in education and working life. According to Bolton and Meierkord (2013), the increased influence of English comes from television, the internet, and other mass media, and Swedish people are often exposed to it (p. 93). The increased use of English in Swedish society is also reflected in the curriculum. For instance, in the Swedish curriculum, the first section

regarding the English subject states that “knowledge of English increases the individual's opportunities to participate in different social and cultural contexts, as well as in global studies and working life” (Skolverket, 2011, p. 53). Therefore, “students should be given the opportunity, through the use of language in functional and meaningful contexts, to develop all-round communicative skills” (Skolverket, 2011, p. 53). This means that the teaching of English must cover all four abilities, i.e., listening, reading, writing, and speaking (Skolverket, 2011, p. 53). Moreover, it is the teachers' role to makesure that each English as a foreign language (EFL) student can further develop their English abilities in each respect.

However, during my three teaching placement periods in a Swedish upper secondary school, I observed that speaking skills were not practiced as much during class in comparison to

listening, writing and reading abilities. Many students never spoke English, neither with the teacher nor their classmates. Although the teacher approached each student in English, they responded in Swedish. The English teachers I encountered during my teaching periods were unanimous in their perception that they themselves only speak English during class. Some of the teachers claimed that the stricter they were about speaking English, the more the students would improve their speaking abilities and develop the desire to orally communicate in English as well. However, some students might experience issues in expressing themselves in spoken English, which can lead to some of them developing anxiety with regard to the

English language.

Horwitz (2001) explains that anxiety is a subjective feeling, often related to tension and nervousness, and that language anxiety is defined as emotions being negatively affected by a second or a foreign language (Horwitz, 2001, p. 113).Against this background, EFL students who experience anxiety regarding the English language must be provided withthe

opportunity, from the teacher, to reduce their level of anxiety. There is no question that the teachers are the ones in the classroom who can increase or decrease language anxiety among

their students (Kráľová, 2016, p. 49). However, each student’sneeds must be considered individually, and teachers are obligated to develop different solutions for their students, depending on their needs (Skolverket, 2011, p. 6).

1.1 Aim and research questions

Gaining a greater understanding of the different causes of language anxiety could be beneficial for future teachers, as this might help teachers adapt their teaching to meet the needs of every student. Moreover, in parallel to exploring the students’ perspective, learning more about some teachers’ strategies to decrease their students’ anxiety level will also be educational for both future and certified teachers, which is why both students and teachers have been interviewed in the present study. More specifically, this study aims to address the following research questions:

1. What are the causes of language anxiety in the English subject, as reported by three Swedish upper secondary school students?

2. According to three Swedish upper secondary school students, what is the most beneficial approach and attitude a teacher can have to decrease the students' anxiety level with regard to the English language?

3. What strategies do three Swedish upper secondary school teachers use to decrease their students' language anxiety in the English subject?

2 Background

2.1 The Swedish curriculum for upper secondary school

To fully understand why it is important for students to speak English during class, we can take a look at the Swedish curriculum for the upper secondary school (Skolverket, 2011). The Swedish curriculum states, among other things that the aim for the English subject is to develop the students’ English language abilities, so that they can use the language in “diverse areas as politics, education and economics” (p. 53). That is to say, the primary purpose of learning English in Swedish upper secondary school is to be able to communicate. For a student to achieve a passing grade in the first upper secondary English course called English 5, they need to be able to “show an understanding by giving an overview of, discussing, and commenting on content and details […] choose and with some certainty use strategies to utilize and to critically review the content of spoken and written English” (Skolverket, 2011,

p. 55). With this, the curriculum indicates that it is expected from the students to communicate orally during class activities and discussions.

To achieve this goal, teachers are expected to provide the studentswith “the opportunity to interact in speech and writing, and to produce spoken language and texts of different kinds, both on their own and together with others” (Skolverket, 2011, p. 53). However, each student experiencesdifferent difficulties when it comes to the English subject, and therefore the teaching must be adapted to each “individual student’s needs, circumstances, experiences and thinking”, so as to “strengthen each student’s self-confidence, willingness and ability to learn” (Skolverket, 2011, p. 10).

The core content in the English subject is a guideline for teachers to create a successful process for students to develop their language abilities (Skolverket, 2011, pp. 54-55). It also provides different categories of abilities in the English subject that the students must aim to achieve. When it comes to “reception” and “production and interaction”, the focus is on oral aspects. For instance, the students need to develop speaking strategies to contribute to discussions regarding society and working life (Skolverket, 2011, p. 55). This is relevant to consider since students who experience language anxiety will most likely find these aspects problematic to encounter during class. Moreover, Skolverket (2011) states that oral

production in the English subject is an opportunity for students to communicate orally about their reflection and to express themselves in English (Skolverket, 2011, p. 53).

“Teaching of English should aim at helping students to develop knowledge of language and the surrounding world so that they have the ability, desire and confidence to use English in different situations and for different purposes” (Skolverket, 2011, p. 53). The formulation “ability, desire and confidence to use English” seems to suggest that speaking in another language is potentially problematic for students. Therefore, it is beneficial for students to participate in communicative situations that encourages them to take risks when it comes to speaking in English. That in turn, means that it is important for teachers to establish classroom situations that motivate their students to actually communicate orally in English.

2.2 Language anxiety

Horwitz et al. (1986) define anxiety as being associated with the “autonomic nervous system”, meaning that someone might experience emotions such as nervousness and being worried in various situations. Anxiety concerning a second language is, in psychological terms, a

“specific anxiety reaction,” which only activates the emotions of anxiety in certain situations (Horwitz, Horwitz & Cope, 1986, p. 125). According to Krashen, the feeling of anxiety creates an “affective filter” for the students that becomes a hinder to any type of language input, that is to say that they will not be receptive to a foreign language (as cited in Horwitz et al., 1986, p. 127). Therefore, the students will not communicate orally in a foreign language because of its negative association, which in turn prevents them from developing fluency in the language. Horwitz et al. (1986) further explain that because of language anxiety some students fail to perform orally in class and do not produce the required output, which leads to the teacher assessing the students incorrectly (p. 127). Moreover, students who experience language anxiety in the English subject can sometimes have a so-called "mental block against learning a foreign language", even though the same individuals might not otherwise have any issues with speaking (Horwitz, Horwitz & Cope, 1998, p. 125).

To differentiate general anxiety from language anxiety, Kráľová (2016) discusses Horwitz and Young’s two approaches to identify foreign language anxiety: the transfer approach and the unique approach (2016, p. 4). The transfer approach discusses anxiety as being a general emotion that is triggered by other or previous anxiety, meaning that a person might generally feel anxious over several things that can then extend to new factors, such as performing in a foreign language. By contrast, the unique approach views anxiety as being only affected by a specific factor and can only be aroused when in contact to that factor, such as speaking in a foreign language (Kráľová, 2016, p. 4).

2.3 Causes of language anxiety

Language anxiety is an example of the unique approach, i.e., a focused anxiety that only appears when a person is in contact with the foreign language. Horwitz et al. (1986) introduce three factors associated with language anxiety: communication apprehension, test anxiety, and

fear of negative evaluation (p. 127). In addition to these, the classroom environment is

another significant factor that is crucial to discuss in relation to language anxiety (Hashemi, 2011, p. 1813)

2.3.1 Communication apprehension

Communication apprehension is a combination of fear and shyness to communicate orally in groups or in a general conversation. It is not uncommon that people who experience

language (Horwitz et al. 1986, p. 127). Communication apprehension can be divided into two types: production apprehension and reception apprehension. Production apprehension applies to speaking, if the student needs to produce speech in front of others, whereas reception apprehension relates to the student’s ability to understand other (Kráľová, 2016, p. 11).

2.3.2 Test anxiety

In most foreign language classes, students are aware that their language is being monitored and, in some situations, assessed by the teacher. This awareness might cause test anxiety among students, which develops from a fear of failing to perform well. Horwitz et al. (1986) argue that it is common among students to have unrealistic beliefs and high expectations regarding their own foreign language performance (p. 127). Students who put this type of pressure on themselves often decides not to participate orally in the foreign language, unless they feel confident that they will pronounce the words correctly (Horwitz et al. 1986, p. 127). This type of attitude is often a result of students comparing themselves with their classmates. According to Bailey, a competitive nature can lead to anxiety if and when students begin to believe that their performance is not as good as that of their classmates (as cited in Kráľová, 2016, p. 13).

2.3.3 Fear of negative evaluation

Unlike test anxiety, which is related to formally assessed performances, fear of negative evaluation occurs when students are afraid that others will view their performance negatively in any kind of situation (Wörde, as cited in Kráľová, 2016, pp. 11-12). Students suffering from such fears tend to believe that their surroundings, such as classmates and teacher, will judge their performance negatively all the time. This often goes hand in hand with low self-confidence. Anxious students tend to have a “negative perception of both their scholastic competence and their self-worth.” (Onwuegbuzie, Bailey, & Daley, as cited in Kráľová, 2016, p. 14) In general, many students who look down upon themselves and their performance often believe that they are not capable of achieving a specific goal, which causes their negative self-perception to develop into anxiety.

2.3.4 Classroom environment

A student’s perspective of negative evaluations can be changed depending on the classroom environment. In a classroom situation, many students tend to direct their “attention between self-awareness of their fear and worries and class activities themselves” (Aida, 1994, p. 157).

Hence, they persuade themselves with negative thoughts, e.g., that they will mispronounce a word, or that the teacher is ready to correct any mistakes in front of the class. Significantly, the students become “distracted and anxious during class,” which results in them failing to participate (Aida, 1994, p. 157). Yashima, MacIntyre and Ikeda, 's (2018) study showed that by repeating topics, the students would develop more confidence in their knowledge of the topic and their proficiency, which leads to them being more willing to participate in oral communication (Yashima, MacIntyre & Ikeda, 2018 p. 126).

Some students are also affected by their surroundings, such as classmates and their teacher, and tend to believe that others will judge their performance (see 2.3.3). Moreover, the general learning environment may cause language anxiety. In his study, Hashemi (2011) found that Iranian students blamed the “strict and formal classroom environment as a significant cause of their language anxiety” (p. 1813). Hashemi (2011) argues that these types of responses from students should be a wake-up call for the teachers to reflect upon their own classroom environment and how they can reduce language anxiety among their students (p. 1813). Similarly, research by Ningsih, Narahara & Mulyono (2018) showed that EFL students who experience language anxiety found it difficult to speak English due to an uncomfortable classroom environment, the unrelatable topics during discussions, group size, and the lack of support from the teachers (p. 812).

Research suggests that the teachers are crucial to the students’ experience of language anxiety or lack thereof, both in terms of personality and in terms of how they approach their students (Al-Saraj, 2011, pp. 200-201). For example, some teachers might follow a traditional learning system that focuses on an audio-lingual language teaching method. The audio-lingual

language teaching method is based on teaching through listening and speaking before writing and reading. In a traditional learning system, the students must perform the same task several times until they have learned the abilities. A classroom that follows the traditional learning system creates a stressful environment, where the students constantly feel that they must perform correctly in their foreign language, which can result in the students becoming more anxious. By contrast, a classroom that invites “collaborative activities among the students” resulted in reduced anxiety (Hashemi, 2011, p. 1813). Through activities that invite a positive attitude regarding oral communication with others, a student will be more likely to be willing to participate without feeling anxious.

2.4 Willingness and unwillingness to communicate

Language anxiety is related to students’ willingness to communicate (WTC) or lack thereof. According to Brown (2007), WTC is related to the concepts of confidence and risk-taking (p. 73), while Ningsih, Narahara, and Mulyono (2018) briefly mention a few factors that affect EFL students’ WTC, such as the teacher or the conversational partner (pp. 812- 813).

Furthermore, Ningsih et al. (2018) claim that students’ WTC relies on the teachers’ patience, attitudes, chosen topic, and encouragement (p. 813). To create an environment where students are willing to communicate, the teacher must establish an interest in communication during class, and this should be reflected in the tasks and activities (Ningsih, Narahara & Mulyono, 2018, p. 813). However, Syed and Kuzborska’s (2018) study showed that the students’ WTC also depended on if they were comfortable, familiar, or friendly with their classmates (p. 8). For instance, a student commented that they rather remained quiet instead of interacting with a classmate whom they suspected would respond negatively (Syed & Kuzborska, 2018, p. 9). Furthermore, when asked how willing they were at taking risks to communicate in English during class, many students responded that they were unwilling to do so if they were unsure of the answers or their pronunciation (Ningsih, Narahara & Mulyono, 2018, p. 817).

Similarly, lack of vocabulary is another aspect of proficiency that can affect the students’ WTC (Syed & Kuzborska, 2018, p. 12).

Jackson and Lius' (2008) study showed that in many situations, there is a correlation between unwillingness to communicate and language anxiety (pp. 78-79). Some of the students in their study who did not participate in conversations in class experienced the fear of being

negatively evaluated, which caused them to be apprehensive about speaking (p. 82).

2.5 Code-switching

Many students who are unwilling to communicate in a foreign language often choose to speak in a language that they are more comfortable with. However, Skolverket (2011) states that English classes should as far as possible be conducted in English (2011, p. 53). In some situations, which can include classrooms, people, including students and even teachers, tend to communicate in two or sometimes even three languages; this process is called code-switching (Cahyani et al. 2018, p. 466). Code-code-switching is defined as a “systematic alternate use of two or more languages in a single utterance or conversational exchange for

communicative purposes.” (Cahyani et al. 2018, p. 466) In a classroom environment, students who speak a second language (L2) often shift to their first language (L1), which in most

situations is the language they are most comfortable with. According to Moore (2002), code-switching can in fact help develop students’ language learning. For instance, code-code-switching can be beneficial when explaining the meaning of an L2 word by using the L1 as a tool. However, if a teacher uses this type of strategy too often, the students might create a habit of using the L1 in an L2 conversation. Moreover, Moore (2002) explains that using

code-switching in a classroom environment can, in some situations, result in misunderstanding. For instance, a teacher might use their L1 to explain a word in L2; however, if the teacher uses similar words that have different meanings in each language, there may be confusion. Therefore, a teacher must know how and when to use code-switching in the classroom (Moore, 2002, p. 289). On the other hand, using code-switching at the early stages of an EFL education can be beneficial for students in that it helps them develop their language

proficiency (Moore, 2002, p. 291) – and thus perhaps reduces their language anxiety.

Code-switching can be helpful when the foreign language is beyond the students’ ability and certain adaptations need to be made (Ahmad & Jusoff, 2009, p. 49). However, Moore (2002) claims that students should try to solve their communicative issues and develop their language abilities for any type of situation. Hence, the teacher’s role is to reduce the unsettling feeling of speaking in a foreign language and to instead help them understand how to adapt the language to different speaking situations (Moore, 2002, p. 281). The author discusses code-switching strategies used by teachers to provide the assistance needed by their students. For instance, the teacher can choose not to comment on language choice in a conversation, meaning that a student is allowed to shift between L1 and L2; however, the teacher should be prepared to fill in the student’s missing L2 words (Moore, 2002, p. 286).

2.6 Teachers’ strategies

In the previous section, code-switching was discussed as a possible strategy to use in the classroom. This section reports on the conclusions from previous studies regarding additional strategies an English teacher can use to prevent language anxiety among EFL students.

According to Kráľová (2016), a teacher ought to remain friendly and give the impression of being patient and helpful. However, the most crucial aspect for a teacher is to pay attention to signs of anxiety radiating from students (Kráľová, 2016, p. 49). According to the author, one major mistake a teacher can make is to unexpectedly request a specific student's response during class, which might shock the student and cause them anxiety. Instead, a strategy to use

in class is to call out students in a predictable order, so that each student can prepare themselves to answer, which causes less anxiety to speak (Kráľová, 2016, p. 50).

Brown (2007) lists four important strategies to use in a classroom environment with students who have limited willingness to communicate, which are: giving assurance, positive

feedback, teachers attitude and risk-taking (p. 74). According to Brown (2007), it is important

to give students verbal and nonverbal assurances regarding their ability, thereby promoting a feeling of hope and success. Hence, the students will focus on solving their issues instead of fearing them. Similarly, Brown (2007) states that the teachers’ responses to their students should be based on positive feedback and include praising the students’ attempts to communicate, thereby creating an emotional state of success and satisfaction. Only then should language mistakes be discussed in a calm and concrete fashion (Brown, 2007, p. 74).

The third of Brown’s (2007) strategies implies that the teacher should have a willing attitude to create a safe and welcoming environment for students to express themselves in English (p. 74). Kráľová (2016) argues that this type of atmosphere can quickly be established through small steps, such as not directly correcting the students’ grammar mistakes and instead be subtle when giving feedback (p. 45). By initiating a continuous dialogue with their students about their worries and emotions regarding the oral aspects of the English subject, teachers can help them overcome their worries (Kráľová, 2016, p. 46). During these dialogues, teachers must also encourage their students’ WTC and decrease the stigma of making mistakes. Therefore, the last strategy emphasizes the importance of making the students understand what calculating risk-taking is and that they must dare to take the risk to speak in order to develop their language proficiency (Brown, 2007, p. 74). In conclusion, different types of strategies can be used to help students decrease their anxiety with regard to the English language.

3 Method

In order to answer the research questions about the causes of language anxiety according to three Swedish upper secondary school students, and what approaches, attitudes and strategies their English teachers adopt to reduce the students’ level of anxiety, a qualitative method was used for this study. This section provides further details about the participants, data

3.1 The participants

To gain some insight into how language anxiety can be experienced and possibly reduced in Swedish upper secondary school, I interviewed three formally certified English teachers at three different upper secondary schools in Sweden. Each of the teachers also introduced me to one Swedish EFL student who was willing to be interviewed by me, thus bringing the total number of participants to six. All of the students were attending the course English 6, whereas one also studied advanced English in the second year of upper secondary school.

The gender of the participants is of no interest for this study and will not be mentioned. Henceforth, I will refer to the participants by the pronouns they/them, as well as by the labels Teacher/Student A, B and C. The gender-specific references used by the participants in the direct quotes included in the results section below will be replaced by gender-neutral

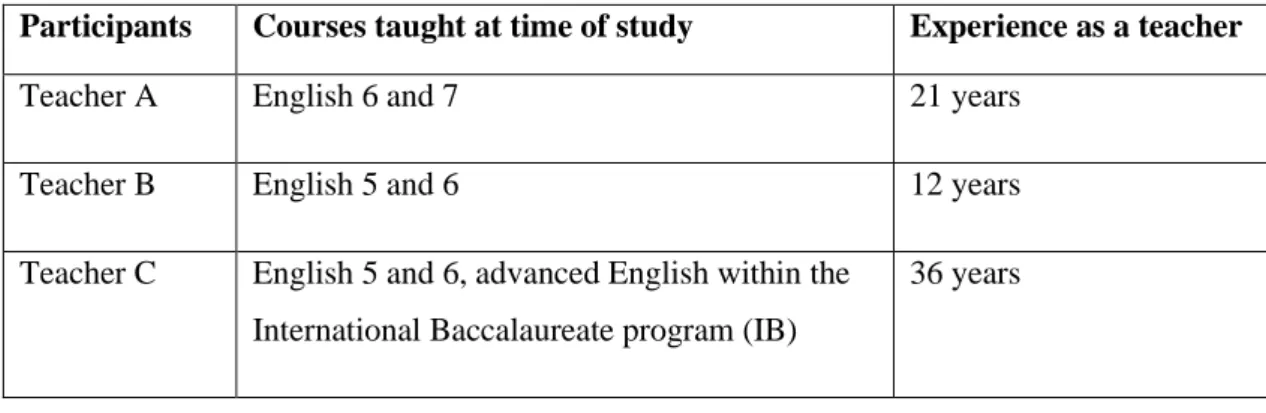

pronouns in square brackets. An overview of the participating teachers is provided in Table 1.

Table 1: General information about the teachers.

Participants Courses taught at time of study Experience as a teacher

Teacher A English 6 and 7 21 years

Teacher B English 5 and 6 12 years

Teacher C English 5 and 6, advanced English within the International Baccalaureate program (IB)

36 years

I began to search for English teachers in Sweden via Google and found several email

addresses. After contacting them, I asked the teachers to forward a letter written as a request for students to participate in this study. However, the letter was not a success, and no student contacted me. Due to the Covid-19 pandemic that was going on during the project, I requested the teachers to forward my email to their colleagues in purpose of not to physically meet. This process was continued until six participants were found. This so-called snowball effect proved to be a suitable way to collect participants (cf. Alvehus, 2019, p. 72). One disadvantage of this method is that relying on a network of people knowing each other carries an increased risk of receiving similar answers and points of view on the subject in question.

When it comes to the participating students, the most valid way to assure that the participants experienced language anxiety was to turn to the teachers and ask them to help me contact

students fitting that description. When one of the original student participants chose to no longer take part in this study, the snowball effect was a quick way to find a replacement by asking the teacher once again.

3.2 Data collection

The data for this study were collected using semi-structured interviews that included open-ended questions, allowing the participants to express their opinions and further develop their answers, if desired. All the interviews were conducted individually to ensure that the

participants' responses were not influenced by each other. I also chose to be more active in listening than speaking, since creating a discussion during the interviews might result in changing the participant’s original answer (Alvehus, 2019, p. 87). It is also worth mentioning that due to the pandemic and the social distancing restrictions, all the interviews were

conducted via the digital video communication tool Zoom.

In consideration of the students who are experiencing language anxiety, I chose to conduct the interviews in Swedish in order to make the situation as comfortable for them as possible. (However, the interview questions were translated from Swedish into English in appendix 2, for the benefit of international readers.) I also sent the interview questions beforehand to the students for them to get an understanding of the topic. Preparing the participants for the coming topic is according to Saldaña (2011), a way to avoid nervousness, which is a factor that could affect the participants’ responses (p. 35). When constructing the interview guide for the students, I chose to divide the questions into three categories based on aspects mentioned in the core content of the Swedish curriculum (Skolverket, 2011, p. 53). By relating the interview questions to the Swedish curriculum, I could maintain coherence throughout the interview and cover all the oral aspects of the English subject (see appendix 2 for more details). The three categories are Production apprehension, Reception apprehension, and The

role of the teacher (Skolverket, 2011, p. 53). The first category primarily focuses on the

students’ experiences of speaking in a foreign language during whole-class discussions, in smaller groups, and when giving an oral presentation in front of an audience. The second category paid attention to the students’ general view of their understanding and use of the English language in relation to their surroundings. The questions also address the students’ perception of receiving spoken English input. The third category contains questions that focus on the role of the teacher in the classroom and how the students experience the teacher’s approach and attitudes in relation to their language anxiety.

Unlike the students’ interviews that were conducted in Swedish, the teachers’ interviews were carried out in English. The interview questions for the students were taken into consideration when creating the teachers’ questions, to consider similar themes from both perspectives. As in the student interviews, the questions for the teachers were divided into categories: Speaking

in the classroom, Language anxiety among students, the physical environment, and Teacher strategies to decrease language anxiety (see appendix 1 for more details). The first category,

speaking in the classroom, consisted of questions regarding the students’ willingness to communicate in English during class. The second category included the different types of causes of language anxiety and the teachers experiences with their students. The third category focused on the physical environment, while the fourth and last category discusses what teaching strategies are most beneficial for students with language anxiety.

3.3 Data analysis

The data for this study were analysed using content analysis, following an established four-stages process: the decontextualization, the recontextualization, the categorisation, and the

compilation (Bengtson, 2016, p. 11).

The first stage, the decontextualization, consists of transcribing the interviews verbatim. The teachers’ interviews were carried out in English and thereafter transcribed. The students’ interviews were conducted in Swedish, transcribed into that language, and then translated into English. To avoid any misunderstanding in the transcription process, I listened to the recorded interviews repeatedly to validate the information. (In the passages quoted in the results section below, minor grammar mistakes made by the participants were corrected and occasional clarifications added in square brackets.) In the next step, the transcriptions were coded, which means that words or phrases that are related were highlighted in distinct colours. The second stage, the recontextualization, allowed me once again read the original text and to make sure that topics and information that do not answer my research questions are excluded. Thereafter, the third stage, the categorisation, included combining codes into broader themes that

corresponds to this essay’s research questions, such as self-esteem and self-confidence,

speaking environment, and the teachers’ role in relation to language anxiety. The themes

were also compared across both groups of participants, the students and teachers, in order to find differences and similarities in the participants’ views on language anxiety. Some similarities, such as the importance of the teachers’ approach and attitude, were a recurring

topic of conversation among all the participants. The final step, complication, is the presentation of this study and is shown in the result section.

3.4 Ethical considerations

This study's ethical considerations were based on the aspects mentioned in Good Research

Practice, published by the Swedish Research Council (2017). I informed the participants that

their choice to participate in the study was entirely voluntary and that they could at any point stop the interview if they wished to withdraw their participation. They were also informed that they would remain fully anonymous, meaningthat the identification of any participant would be prevented. The participants were also informed that the collected data would not be used for anything other than this study (Swedish Research Council, 2017, pp. 40-41). Permission to record the participants was given by them before each interview.

4 Results

This section presents the five major themes that were found in all of the teachers and the students’ interviews, which are self-esteem and self-confidence, speaking in class or groups,

the teacher’s role, strategies to reduce language anxiety and adaptation. The first part of the

result section (4.1-4.3) answers the first and the second research question, with a focus on the themes related to the students. The second part (4.4-4.5) focuses on answering the third research question, with themes found in the teachers’ interviews.

4.1 Self-esteem and Self-confidence

4.1.1 The students’ perceptions of self-esteem and self-confidence

By asking how the students felt about oral presentations and discussions in English during class, I could gain an insight into their experiences regarding language anxiety. The students agreed that any type of speaking activity that included them expressing themselves in English caused nervousness and anxiety. Throughout the interviews, the students elaborated on the topic of what causes them to feel anxious and nervous when placed in a position where they must speak English. The primary cause of their anxiety was related to their self-esteem or self-confidence, and this emerged also in the interviews with the teachers. To clarify the difference between the two concepts: Self-esteem relates to how a person views and feels about themselves. That is to say, if a person has low self-esteem they tend to believe that their

abilities are low in general, regardless of the aspect or situation. By contrast, a person who has low self-confidence will mostly believe that their abilities lack in a specific aspect or

situation.

Student A stated that they in general have low self-esteem, which affects their performance in speaking English. Moreover, the student mentioned that they in general view all of their abilities and performance quite low and therefore, also believe that their pronunciation of English words is not good enough for them to speak. Student A explained, “I know I am not good at English, especially when it comes to pronunciation. There is a lot to think about. I do not get the words out. It all just sounds wrong.” Unlike the two previous students, Student A expresses having negative self-beliefs that have developed into an anxiety for speaking in English.

In contrast to Student A who claimed to perform poorly in general and therefore would do so in English, too, Student B considered not having low self-esteem and instead argued that “I don’t feel confident enough to speak English”, explaining that their lack of confidence is caused by the fear of mispronunciation. Mispronunciation was also mentioned by Student C, who claimed that the fear of being judged in this regard was the reason for why they did not participate in English-speaking activities, “I don’t want to speak because I am afraid to say the words wrong and then people will judge me.” The topic of pronunciation was a recurring theme that was mentioned by all the students as a factor that impacts their confidence level.

The lack of confidence in speaking English during group or whole-class activities caused the students to code-switch between Swedish and English. Student A mentioned that “I try to speak English with the teacher as often as I can, but [when I am] in groups with my classmates, it happens that I switch back to Swedish.” When asked why this student only speaks English with their teacher and not with their classmates, the response was that the teacher was the one that graded their English knowledge. Therefore, the student felt pressure to perform, while speaking Swedish with classmates felt safer even when the teacher was present during the conversation. Similarly, Student B also used code-switching, who said, “I usually speak Swedish with my classmates when I get stuck [in a conversation]. It's more comfortable [to speak Swedish] than trying to explain in English.” Likewise, as the other students, Student C stated that, “even though I study a program in advanced English, I sometimes still switch to Swedish [when speaking during English class], and I do that when I'm not sure of my pronunciation in English.” In summary, the results show that the students’

lack of confidence in their English pronunciation often results in them shifting into speaking Swedish, with which they feel more comfortable, and only use English when they are being graded.

4.1.2 The teachers’ perception of students’ self-esteem and self-confidence

As for the question of how common language anxiety is among their students, Teacher A and Teacher B responded that it is very common, whereas Teacher C answered that it varied from class to class. When asked what they experienced or believed were the causes of language anxiety, the teachers' responses correlated to the students’ answers. For instance, Teacher A discussed that Student A puts pressure on themselves regarding their English proficiency, adding that

There are several factors that go with that question, but this student has anxiety in general as well as language anxiety. [They] put a lot of pressure on [themselves], [they] want it to be perfect so when it comes to the moment of doing or saying something, [they] know it, but [they] can’t get it out.

Although there are multiple causes of language anxiety, the lack of confidence in their own knowledge was the main reason the teachers saw in their students “they might feel like they don’t know English that well, everybody else speaks much better, they don’t trust their own knowledge level.” Teacher C argued that from their experiences, one major factor causing language anxiety is when students have exceptionally low confidence in their English skills.

Teacher B and C also mentioned that students who suffer from language anxiety lack practice in oral communication, and that the reason for that is fear of speaking. According to teacher B, “They [students] are afraid of speaking English; they don’t dare to do so. Especially when they know they are speaking English to someone who also speaks Swedish [classmates or teacher]. They don’t want to say it [the words and/or answer] wrong.” Like the students, the teachers also claimed that the lack of self-confidence is partly due to the fear of

mispronouncing words.

4.2 The students’ opinions of speaking in class and in groups

The students’ confidence level regarding their performance in English may change depending on the environment and the situations around them. In order to measure this, the students were asked to place themselves on a scale from 1-5 regarding their confidence level in different English-speaking activities. Level 1 on the scale implies very low confidence, while 5

Figure 1

signifies high confidence. The speaking situations are speaking in front of the whole class,

speaking in front of half the class, and speaking in smaller groups (see appendix 2). Figure 1

presents how the students have ranked themselves with regard to the above-mentioned speaking situations.

As can be seen in figure 1, the students partly felt the same way when it came to speaking in front of the whole class and half of the class. However, the students were unanimous in their view of speaking in smaller groups and felt more confidence then. When asked to explain their rating, Student A answered “I feel uneasy speaking [in front of the whole class], I will be judged by others for my bad English.” Student A continued to explain that if they did have to perform in front of the whole class, they need to have support cards, “When I have my

support cards, I feel a little bit comfort because I know if I get lost in words, I can just look at my cards”. Similarly, Student B responded that the fear of being judged by their mistakes regarding their language abilities was the reason why they chose level 2 on the scale.

However, Student C believed that they were closer to the middle of the scale and chose level 3, claiming that “I do not usually have a problem speaking in front of the class, but when it comes to English class, I need to gather the courage before I speak.” Although Student C had no speaking issues in general, they still felt that they needed to think of the words when speaking English. In comparison, Student B described having low confidence in their pronunciation and therefore found speaking stressful. In conclusion, because of the fear of being judged by their classmates, all the students worried about pronouncing and speaking correctly in English. 2 3 4 2 3 4 3 3 4 0 1 2 3 4 5

In front of the whole

class In front of half class Smaller groups

con fide nc e le ve l Speaking situations

Students' confidence level in different

speaking situations

As could be seen in Figure 1, when they were asked if they would place themselves differently on the scale if they were to speak in front of half the class, Students A and B ranked themselves one step higher and chose level 3, while it made no difference for Student C. Student A argued that “It is easier [to speak in front of half the class] because there are not as many people, and it makes it less stressful.” Similarly, Student B also mentioned that fewer classmates made them feel less anxious, “I feel like I could say things I would not say in a whole class.”

Lastly, the students were asked to rank themselves on how confident they feel when speaking English in small groups. Like the others, Student A positioned themselves as a 4 on the scale, argued that “the best situation is in a smaller group, but with someone I know, then it is more like a four [level on the scale].” In fact, all three students reported that they dare to

mispronounce words if they are in a smaller group with people they feel comfortable with. Student B explained that the “dream scenario” for an oral presentation in English is when the teacher divides the class into smaller groups where they can be with friends they feel most comfortable with.

The results from the previous question regarding their confidence level when speaking in smaller groups, showed that students felt more confident and dared to speak more English in smaller groups. This is reflected in the students’ answers to the question, “in what

situation/environment in school do you feel the most comfortable or confident enough to speak English?” All the students shared similar desires and mentioned that the preferable speaking situation that scarcely makes them feel anxiety was in smaller groups with their friends. For instance, Student C stated, “I feel less anxious if I am with my friends, in smaller groups.” Likewise, Student A and B also expressed that they felt more confident and less anxious if the speaking environment included them speaking in a smaller group.

The overall impression is that the students’ confidence depended on their comfort level and whom they spoke to. Some students expressed that they experienced more doubts regarding their pronunciation when speaking to people they are not comfortable with, which made them less confident. For instance, according to student B, “[in groups with friends] I am more confident. You feel more secure, and it does not matter if you say stuff wrong.” Student A responded similarly by stating that, “You are not as afraid to say things wrong [in a group of friends], you could like laugh it off.” This indicates that the students relate comfort to

confidence, meaning that the more comfortable they feel, the more confident they are speaking English.

4.3 The students’ opinion on the English teacher’s role in the classroom

According to the students, the teacher’s approach adopted in the classroom played asignificant role for their anxiety level in relation to different English-speaking activities. Student A explained that they felt the most anxious when they must perform in front of an audience. However, the teacher allowed their students to use keyword/support cards during a presentation as an aid. Student A alleged that “keyword/support card makes me want to speak more because I feel more comfortable.” Even when the students had to present orally in front of half the class, they still felt less anxious when allowed to have cards with keywords.

Student B argued that the idea of being graded by the teacher increases their anxiety level and, therefore, makes it hard to perform in English. Student B further explained that the teacher is “not only grading what we do in class, such as assignments, but, for example, also assesses a normal dialogue with them; that makes me feel like the teacher is judging me and it can affect my anxiety level.”

How teachers approach students with language anxiety is crucial to how they will participate in English-speaking activities. Student A confirmed this by claiming that “I do not feel so nervous with my teacher because [they] are understanding, [they] know that I do not speak English well, so [they] do not stress me.” Furthermore, Student A explained that their teacher approached each student with patience regarding their language abilities and actively listened to what they said. Student A praised this approach highly and emphasized that through this approach, the teacher influences students to speak. Likewise, Student C discussed that it is the teacher's responsibility to create an inviting “non-judgemental” speaking environment for every student to be willing to communicate orally in English. Student C developed their argument by stating:

It is important for the teacher to not show much authority in the classroom who decides everything; they should instead work with us [students] and be more helpful.

By this Student C argued that, although the teacher does have authority in the classroom, they should not have an attitude that separates the teachers from the students. By this Student C means that a teacher should have a positive attitude that endures willingness to collaborate

with students and to become a guide to help student develop a WTC and reduce anxiety. The student further explained that:

[the teacher must have] patience when listening [to their students], to not interrupt any of the students when they are speaking [and also] to create an environment [in the classroom] where everyone is respecting each other’s way of speaking.

Moreover, Student C claimed that the most beneficial approach from the teacher is to have an understanding approach to each student’s experiences in the English language. Such an approach would make the students feel that they do not have to perform perfectly, and could instead communicate based on their own ability.

In summary, the students’ responses suggest that the teachers play a major role in creating an environment that feels safe and comfortable enough for the students to express themselves in the foreign language.

4.4 The teachers’ strategies to reduce language anxiety among their

students

It is now understood that the students consider the teacher to affect the rate of their anxiety. Turning now to the teachers who were asked what strategies they believed are beneficial to reduce their students’ language anxiety. While they partly mentioned similar strategies as the students, e.g., the use of keyword/support cards during an oral presentation, they also

discussed other essential strategies.

Teacher A believes that language anxiety can be decreased by continuously practicing speaking English during every class, adding “At the start of every class we watch the news and then we have a group discussion about what is going on around the world…I purposely put them in standard ‘table groups,’ which means that they always sit with the same people” (Teacher A). Through this, the students practice and form a habit of speaking to one another in a casual conversation in English. Teacher A’s strategy suggests that by practicing speaking English during casual conversation, the students will eventually feel more confident in

speaking, thus decreasing anxiety for the language. Therefore, Teacher A’s approach was to create an environment where speaking English is not something to fear. According to Teacher A, the best way for a student to achieve a state where speaking English is less intimidating is through cognitive training, which means that the students’ practice performing in English, step by step. Ultimately, they will thus be able to take risks in communication and willingly

participate in speaking activities. Regarding small group presentations and activities, Teacher A discussed the pros and cons, “Even though smaller groups are the most comfortable

environment for the student [with language anxiety], [they] tend to speak Swedish quite often with each other, so I try to be around and mix the groups up” (Teacher A). To clarify, Teacher A means that although using smaller groups decreases the students’ anxiety, it does not automatically help them to develop their language abilities. Instead, the students should be encouraged to take risks and speak up in order to reduce anxiety and develop their English proficiency.

Teacher B did not have as many discussion activities during class as Teacher A, and instead claimed that “we do shorter speaking activities, it could be in the beginning of a class. For example, like a game to get the students started [to speak].” Teacher B did not share the same opinion regarding practicing English as often as possible and instead argued that the students’ comfort is more important than forcing them into speaking. Moreover, Teacher B focused on strategies that increase the students’ confidence level instead of encouraging them to present in front of an audience, arguing that “with increased confidence, the students themselves will eventually feel comfortable and confident enough to present before an audience.” To make the student feel comfortable enough to speak Teacher B chooses to divide the class into smaller groups for both oral presentations and activities, explaining that “smaller groups are the best situation for a student with language anxiety, so I try to spread them outside of the classroom where the students get some privacy.”

Teacher C also argued that smaller groups are the most appropriate strategy for students who experience language anxiety. However, Teacher C discussed the importance of knowing their students’ needs and, therefore, focused on positive encouragement and feedback:

Show the students that it is not that bad to take the risk to speak English... In order to make the student realize it was not that scary as you [referring to the students] thought it might be, and whenever you say something, I’m just going to give you feedback in a positive sense, and I am going to support you, make you go forward, and make you speak English to me. That is what my aim is.

In comparison to the other participating teachers, Teacher C endeavours to achieve the same goal for all their students, which is to at least once in each English course present before an audience. According to Teacher C, they have achieved this aim with every student through positive encouragement. Furthermore, Teacher C explained that the students have the choice

to present in front of an audience whenever they want, as long as they do it. The type of encouragement they give the student is, for example, to say “You [the student] have options, I am not going to force you into anything, I want you to feel comfortable. But the main aim is that one day, you are going to stand in front of this class [to present orally], and I know you will do it.” However, Teacher C was fully aware that this type of attitude might intimidate a student who experiences language anxiety. Therefore, Teacher C approaches students with language anxiety more carefully with consistent communication. Teacher C further explained that they encourage speaking English on a daily basis, which creates an environment where the students can feel comfortable enough to express themselves orally. Thereafter, the process to develop the students’ oral performance must be done step by step at their pace, thus

achieving the primary goal. Teacher C continued by saying that a teacher must show

dedication and awareness of the students’ anxiety throughout the process. This process is, of course, done with the students’ consent.

The most beneficial and appreciated strategy that all the participants mentioned was

adaptation, which is why it is considered a theme on its own and will be further developed in the next section.

4.5 The teachers’ and students’ attitudes regarding adaptation

Adaptation is not an unknown strategy in the teaching profession; however, it is challenging to individually adapt the teaching to each student with language anxiety. From experience, Teacher A stated that students with language anxiety also tend to be shy and therefore are not the first to approach the teacher with information about their anxiety. Hence, Teacher A claimed that “you can tell by their [the students] body language that they are uncomfortable. So I don’t choose them [to answer questions out loud].” Having experience of language anxiety among their students, Teacher A could identify students who were experiencing oral activities as uncomfortable by observing them. The teacher further explained that this is usually the first step, and thereafter the teacher must initiate an open dialogue with the students regarding their language anxiety. As mentioned before, one example of adaptation that Teacher A does is allowing keywords/support cards during a spoken presentation. This is also an example of how dialogues between the students and the teacher can establish a

temporary solution to avoid language anxiety. Students with quite severe language anxiety tend to avoid doing an oral presentation in front of anyone; therefore, the teacher will adapt the assignment to the student. Teacher A gives the example of an adaptation of an assignment

they made when a student was not willing present orally in front of an audience, therefore the teacher allowed the student to video record themselves instead. The teacher further explained that during a regular class they also try to trigger casual conversations by asking students several questions with the purpose of getting the students to speak English:

Normally I use a lot of the cooperative strategies… we talk about how does this feel, how does this look like, how does this smell like etc.…it [the questions] is very personal you do not have to perform, [the students] just [have to] say what you think...I have a lot of questions where you cannot get a wrong answer.

According to Teacher A, by asking questions that do not require a single correct answer creates a situation that feels inviting for the students to take risks to speak without having to worry about correctness.

Teacher B stated that “every student has their own needs, and I am here to listen to them, make them feel heard no matter what experience they have with the English language.” Similar to the other teachers, Teacher B also has an open communication with their students, and by this, the teachers can achieve more concrete individual adaptation. For instance, the teacher allowed their students to request classmates they wish to be in a smaller group with, which places the students in a comfortable position. However, Teacher B argued that students who experience language anxiety need to take their time and be encouraged to present in front of the class, or to participate in group discussion. Furthermore, Teacher B, for instance, let the student choose a group of friends to present in front of and then exchange their friends with other classmates. Eventually, the students will, on their own, take the risk to give an oral presentation in front of the class.

Finally, Teacher C mentioned that they have regular development meetings with their

students. During the meetings, Teacher C informs the students about their progress regarding their English abilities. On the basis of that, the teacher and the student together agree on creating new goals to achieve, such as to present in front of a bigger group of people. The meetings are partly intended to be tools for the teacher to create an adaptation for each student and understand each student’s needs. When it comes to what the teacher did to help students with language anxiety specifically, Teacher C said that they focus on each student’s needs and make the student aware that the teacher is willing to work with them to overcome their

anxiety. Teacher C further explained, “I have individual talks on a regular basis. One to One, we talk about this [oral communication]. I ask, ‘how do you feel now, do you feel like you

made any process?’” Student C needed an environment that allowed them to feel comfortable enough to express themselves orally. An example of this type of adaptation was shown when the teacher allowed their students to take their time to speak without rushing them in the conversation, and did not correct their language mistakes directly. Teacher C’s approach was confirmed to be working by Student C, who claimed that the teacher never pressures their students into conversation and does not interrupt them when speaking. Teacher C claimed that working together with each student and adapting the speaking activities their needs, is the most successful strategy to use for the students who experience language anxiety.

5 Discussion

The findings of this study are consistent with those of Ningsih, Narahara, and Mulyono (2018), who claim that WTC is often correlated to language anxiety. Also, the same study showed that the students’ WTC seemed to depend on the situation and their self-confidence or self-esteem. Similarly, in this study, the students themselves discussed the importance of having good self-confidence to be willing to communicate. However, the results of this study also showed that the students’ WTC often depended on the environment and the situation, rather than their self-esteem. For instance, all the students mentioned that they felt less anxious when communicating in small groups with people they felt comfortable with.

One significant cause of language anxiety was pronunciation and the students’ fear of being judged by their classmates, thus leading to an unwillingness to communicate orally and risk mispronouncing English words. This is supported by Kráľová (2016), who argues that pronunciation is a significant factor for language anxiety, and that this is related to one’s self-confidence and identity (p. 36). The present study, too, confirms that the students’ level of anxiety is associated with their level of confidence. For instance, Student A mentioned that they felt less anxious when placed in groups with classmates they felt comfortable with and did not fear being judged for their English proficiency. Even though this study did not focus on the students’ English identity, some of their utterances reflected Kráľová’s (2016) claim that language is related to one’s personality and identity, because when a person is orally communicating, they are also risking mispronouncing words, and therefore put their identity on display for judgment. The students in the present study were fully aware that their anxiety levels increased when put in a situation where mispronunciations might occur, which also caused fear of being judged by their teacher or classmates. However, the teacher can prevent discomfort among their students when it comes to English-speaking activities.

In this study, both the teachers and the students agreed that the teachers’ approach and attitudes towards the students’ needs affected the students’ anxiety and WTC. The students will begin to view their language abilities more positively if the teacher has a positive and patient attitude towards them. Teacher C mentioned that the approach should always include positive encouragement since that will lead to the students building up more confidence in the language. This type of strategy is also discussed by Brown (2007), who argues that by giving verbal and nonverbal assurance of the students’ abilities, they will start to feel hope and success regarding their English knowledge. Conversely, the combination of negative

responses from their surroundings and the students' inner pressure to perform well in English are most likely to create anxiety regarding the language (Kráľová, 2016, p. 13). The students in the present study viewed their abilities as very low compared to their desired English proficiency, which created problems for them. When it came to self-confidence and the courage to speak, the teachers argued that positive feedback significantly affects students’ language anxiety. As mentioned by Brown (2007), a teacher must praise the students' attempts in communication orally and to discuss their language mistakes. Also, the teacher must be patient and give structured positive feedback, as well as encourage the students to take risks in communication. For instance, Teacher C uses positive feedback to encourage their students to orally communicate and argued that positive feedback is a key factor when it comes to having students present in front of the whole class.

In addition, Student C emphasized that their WTC depends on how the teacher establishes the classroom’s speaking environment, which is in line with the curriculum stating that the teachers are to create an inviting classroom environment that motivates students into wanting to speak, and to take the risk of communicating in the target language (Skolverket, 2011, p. 11). The teachers’ approach and attitude are fundamental to establishing a classroom environment that allows students to feel comfortable and confident enough to express themselves. According to Hashemi (2011), students tend to feel stressed in a traditional learning system, if they are expected to continuously perform correctly in class (p. 1813). By contrast, a classroom that includes “collaborative activities among the students” makes them feel less anxious (Hashemi, 2011, p. 1813). In the present study, Teacher A claimed that by adding a discussion activity at the beginning of each English class, the aspect of speaking English will eventually be less dramatic.

This study lends support to the idea that the most beneficial approach is a collaborative relationship between students and teacher. Although the Swedish curriculum suggests that

opportunities for students to communicate orally in various speaking situations must be provided during the English course (Skolverket, 2011, p. 53), it does not specify how exactly this should be achieved, leaving the teacher some liberty in this respect. However, one important piece of advice is not to place students in English-speaking activities where they might feel uncomfortable, as this will most likely increase their language anxiety. As

mentioned by all the teachers, continuous communication with their students is a strategic tool to understand their needs and adapt the English-speaking activities for the students who experience language anxiety. This finding corresponds with a conclusion drawn by Kráľová (2016), who claimed that a teacher should initiate a dialogue with their students to find ways to overcome their anxiety regarding the English language.

6 Conclusion

Through interviews with Swedish upper secondary school students and English teachers, this study provided some insight, from different perspectives, on language anxiety. Overall, the results showed that the main causes of language anxiety derived from the students’ ideas of their ability to perform well, notably not having enough confidence in their pronunciation of English words. In addition, this research has convinced me that the issue of language anxiety affects the students’ ability to reach the learning objectives in the curriculum. The students argued that the teacher has an important role in relation to their language anxiety and the teachers themselves discussed that they do use strategies, such as adaptation of assignments or oral presentations in the English subject, to help reduce anxiety among their students.

The first research question addressed the causes of language anxiety among three Swedish upper secondary school students. The participating students in this study all emphasized low self-confidence or self-esteem and the fear of being judged by their surroundings as the two major causes of language anxiety. On the other hand, the students’ responses also indicated that their level of confidence changes depending on the situation and their surroundings. The students argued that they are more willing to communicate if they feel comfortable.

The second research question aimed to find out what the most beneficial approaches and attitudes a teacher could have towards students with language anxiety, according to the

students themselves. The general results suggest that the most beneficial approach for teachers is to create a habit of having a positive continuous open dialogue with their students. By being patient and making the students feel acknowledged by allowing them to participate in their

teaching process, the students became more willing to communicate during English-speaking activities. For instance, Student A felt more comfortable and less anxious if they could use support cards with keywords when presenting in front of an audience. By contrast, Student B and C explained that being in small groups with people they are comfortable with increased their confidence level and resulted in reduced anxiety.

The focus of the final research question was to understand what strategies English teachers used to decrease language anxiety among their students. By understanding what causes anxiety among the students, the teachers could establish strategies accordingly. For instance, Teacher A uses group activities during English class to abolish the fear of speaking, and all teachers aim to create an environment where the students develop their willingness to communicate orally in English. The result thus confirms that the teacher’s role in the classroom is crucial to students who experience language anxiety, and it suggests that EFL teachers and students ought to work together to decrease language anxiety.

6.1 Future research

Being limited to only six participants, this study could not provide generalizable results; therefore, it would be interesting to further investigate the topic with a wider variety of participating teachers or/and students. Future investigations might even focus on participants from different countries for a comparison of the respective perspectives and strategies regarding language anxiety. In this way teachers in e.g. Sweden might develop new ideas, approaches and strategies. In addition, it would be interesting to conduct the same kind of study with teachers and students from both practical and theoretical upper secondary school programs, and again to compare the results. The general prejudice that students in practical programs tend to be low achievers compared to those in theoretical programs might have an effect on the number of students experiencing language anxiety and how this is addressed.

Reference list

Ahmad, B, H., & Jusoff, K. (2009). Teachers' Code-Switching in Classroom Instructions for Low English Proficient Learners. English Language Teaching, 2(2), 49-55.

DOI:10.5539/elt.v2n2p49

Aida, Y. (1994). Examination of Horwitz, Horwitz, and Cope's Construct of Foreign Language Anxiety: The Case of Students of Japanese. The Modern Language Journal,

78(2),155-168. DOI:10.2307/329005

Al-Saraj, T. M. (2011). Exploring foreign language anxiety in Saudi Arabia: a study of female

English as foreign language college students.[Doctor thesis/University of London].

https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10020618/1/AL-SARAJ,%20T.M.pdf

Alvehus, J. (2019). Skriva uppsats med kvalitativ metod: en handbok (2nd. ed.). Liber.

Bengtsson, M. (2016). How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis.

NursingPlus open, 2, 8-14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.npls.2016.01.001

Bolton, M., & Meierkord. (2013). English in contemporary Sweden: Perceptions, policies, and narrated practices. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 17(1), 93–117.

https://doi.org/10.1111/josl.12014

Brown, H. (2007). Principles of language learning and teaching (5th. ed.). Longman. Cahyani, H., de Courcy, M., & Barnett, J. (2018). Teachers’ code-switching in bilingual classrooms: exploring pedagogical and sociocultural functions. International Journal of

Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 21(4), 465–479.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2016.1189509

Hashemi, M. (2011). Language Stress and Anxiety Among the English Language Learners.

Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 30, 1811-1816.

DOI:10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.10.349

Horwitz, E., Horwitz, M., & Cope, J. (1986). Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety. The