Corporate Social Responsibility in

the Fashion Industry

Challenges for Swedish Entrepreneurs

Master thesis within Managing in a Global Context

Authors: Annemiek Rian Kooi

Frauke Dietrich

Tutor: Anna Blombäck

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our supervisor Anna Blombäck for her great support and guidance during the process of developing our master thesis. Further we would like to thank our fel-low students for their constructive feedback during the seminars.

The completion of this thesis would not have been possible without the contribution of all involved entrepreneurs. We would like to thank them for their time as well as the trust and interest shown in our thesis.

Master Thesis in Managing in a Global Context

Title: Corporate Social Responsibility in the Fashion Industry – Challenges for Swedish Entrepreneurs

Author: Annemiek Rian Kooi

Frauke Dietrich

Tutor: Anna Blombäck

Date: 2015-05-08

Subject terms: Corporate Social Responsibility, fashion industry, Swedish entre-preneurs

Abstract

Background: Nowadays companies are facing an increased need to adopt Corporate

Social Responsibility (CSR) in their business strategy. This pressure is especially high in industries which cause a great environmental impact and are also highly exposed to the public. Recent scandals raised ethical discussions in the fashion industry, which demonstrates the need for more CSR in this sector. In response to these developments of ethical concern in the fashion industry, several entrepreneurial companies have entered the market with an alternative sustainable approach.

Problem: CSR and its chances are widely discussed in the existing literature. However, its challenges, especially those that entrepreneurs are facing, have so far been neglected. But due to their innovative power, entrepreneurs could drive the fashion industry into a more sustainable direction. Therefore, this thesis aims to explore whether entrepreneurs in Sweden with a sustainable orientation perceive particular challenges with regard to their CSR activities. By finding out what specific challenges Swedish entrepreneurs are facing, it will be revealed what needs to be done in order to ease the path for sustainable entrepreneurs in the fash-ion industry.

Method: In order to answer the research question a qualitative study was

conducted using a narrative inspired approach. Hence, five Swedish entrepreneurs were interviewed that are active in the fashion industry with a sustainable business orientation. The researchers aimed to investigate the stories of the interviewed entrepreneurs in order to find out if they are facing any challenges regarding CSR with their sustainable business approach. The interviews were conducted both by telephone and email.

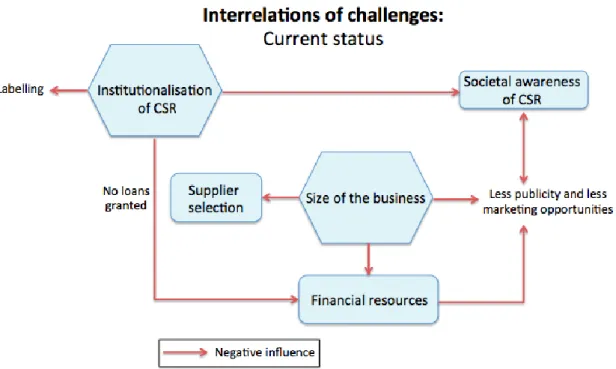

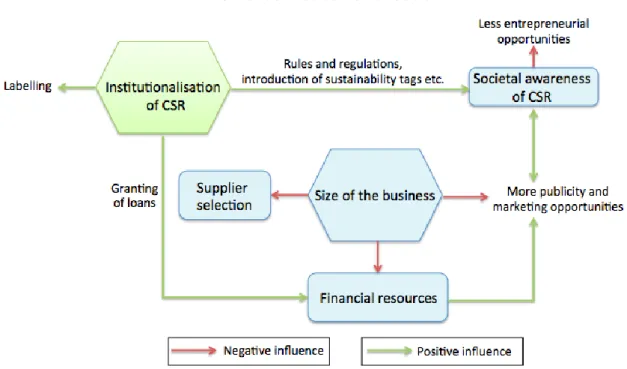

Conclusion: It was identified that the entrepreneurs were facing different kinds of challenges regarding the size of the business, financial resources, the awareness of the need for CSR, supplier selection and a lack of institutionalisation. Furthermore a model was developed which demonstrates the interrelations of challenges and which also shows the positive influences that an increased institutionalisation in the fashion industry would have. It was noticed that the fashion industry is currently undergoing a transformation towards more CSR and this thesis shall serve as a contribution towards a more sustainable fashion industry.

Table of Contents

1

Introduction ... 1

1.1 Background ... 1 1.2 Problem discussion ... 2 1.3 Outline ... 32

Theoretical Framework ... 4

2.1 Corporate Social Responsibility ... 4

2.1.1 The need for Corporate Social Responsibility ... 4

2.1.2 Defining Corporate Social Responsibility ... 4

2.1.3 Corporate Social Responsibility vs. Sustainability ... 5

2.1.4 Chances and challenges of Corporate Social Responsibility ... 6

2.1.5 Sustainability in Sweden ... 7

2.2 Fashion Industry ... 8

2.2.1 Supply chains and market conditions ... 8

2.2.2 Corporate Social Responsibility in the fashion industry ... 9

2.2.3 Institutionalisation of Corporate Social Responsibility ... 11

2.3 Sustainable entrepreneurship in the fashion industry ... 12

2.3.1 Entrepreneurs in the fashion industry ... 12

2.3.2 Sustainable entrepreneurs ... 13 2.4 Summary ... 14

3

Methodology ... 15

3.1 Research design ... 15 3.1.1 Qualitative study ... 15 3.1.2 Narrative analysis ... 15 3.2 Data collection ... 16 3.2.1 Choice of entrepreneurs ... 16 3.2.2 Interview settings ... 17 3.2.3 Interview method ... 18 3.3 Data analysis ... 18 3.4 Limitations: Trustworthiness ... 194

Empirical Studies ... 21

4.1 Just Africa ... 21 4.1.1 Company presentation ... 21 4.1.2 Interview findings ... 21 4.2 Uma Bazaar ... 23 4.2.1 Company presentation ... 23 4.2.2 Interview findings ... 23 4.3 ELSA AND ME ... 25 4.3.1 Company presentation ... 25 4.3.2 Interview findings ... 25 4.4 Nerdy by Nerds ... 27 4.4.1 Company presentation ... 27 4.4.2 Interview findings ... 274.5 Mini Rodini ... 29

4.5.1 Company presentation ... 29

4.5.2 Interview findings ... 29

5

Analysis & Results ... 31

5.1 Types of challenges ... 31

5.1.1 Size of the business ... 31

5.1.2 Financial resources ... 31

5.1.3 Awareness of the need for Corporate Social Responsibility ... 32 5.1.4 Supplier selection ... 32 5.1.5 Institutionalisation ... 33 5.2 Interrelations of challenges ... 34

6

Conclusion ... 37

7

Discussion ... 38

7.1 Authors reflections ... 387.2 Suggestions for further research ... 38

Figures

Figure I: Interrelations of challenges: Current status ... 34 Figure II: Interrelations of challenges: Towards institutionalisation ... 35

Tables

Table I: Participants of this study ... 17

Appendix

1Introduction

1.1

Background

Clothing has always been a basic human need (Schaltegger & Hansen, 2013). Even though the purpose of fulfilling this basic need remains unchanged, fashion trends itself change constantly. Sustainability on the contrary has to do with a long-term perspective. Since the production and use of fashion cause a significant amount of waste, one would assume that fashion constraints sustainability. Despite this contradiction, fashion should not inevitably lead to a conflict with ethical principles as stated by Gardetti and Torres (2013).

The pressure on ethical principles is especially high in industries which cause a great envi-ronmental impact and high visibility in the public perception (Seuring, Sarkis, Muller & Rao, 2008). Recent scandals like the breakdown of a fashion manufactory in Bangladesh in April 2013 raised ethical discussions and demonstrated that the fashion industry is highly exposed to the public (Caniato, Caridi, Crippa & Moretto, 2012). Fashion companies are not only held responsible for environmental and social problems they cause themselves, but also for those created by their suppliers (Koplin, 2005). As explained by Caniato et al. (2012), companies in the fashion industry make use of suppliers located across the world by sourcing raw materials like fibres and leather from distant locations and by subcontracting diverse production activities like dyeing, cutting and sewing to different external partners. Another ethical concern they mention, which arises in connection with the fashion produc-tion, is its high environmental impact. Intensive use is made of chemical products and natural resources during the production process, especially in the phases of dyeing, drying and finishing (De Brito, Carbone & Blanquart, 2008). Fashion companies often have their goods produced in low-labour-cost countries from where they need to be shipped to con-sumers in Europe and the US, which results in further environmental impacts due to the transportation process (Abecassis-Moedas, 2006; Borghesi and Vercelli, 2003). Schaltegger and Hansen (2013) state as a reason for this outsourcing of parts of the clothing produc-tion processes the pursuit of comparative cost advantage due to the high price pressure which the fashion industry has been facing for the last few decades. They further state that this development is accompanied by ethical problems with suppliers concerning working conditions and environmental pollution.

As response to these recent developments of ethical concern in the fashion industry, a number of entrepreneurial companies have entered the market with an alternative value creation approach, which aims to cause less of the above mentioned impacts on environ-ment and society (Schaltegger & Hansen, 2013). These new kind of entrepreneurs usually show a high level of environmental and social performance, which attracts consumers who are particularly concerned about sustainability and ethical issues (Hockerts & Wüstenhagen, 2010). According to Schumpeter (1987), a sustainable entrepreneur sees unsustainable con-ditions as reasons for creating new and more sustainable products and services. However, sustainability-oriented innovations do not only include products, services and production processes, but can also become focus of the core business and revenue model and there-fore it represents a central element of the company’s role in shaping society (Hansen, Große-Dunker & Reichwald, 2009). During the first decade of the 21st century, an

increas-ing number of young entrepreneurs considered sustainable fashion as the foundation for their business and not a new selling point (The Guardian, 2013).

As stated by Schaltegger and Hansen (2013), a sustainable orientation can create competi-tive advantages for entrepreneurs, like value generation through healthy products. The

in-troduction of organic textiles for example can represent additional customer benefits, when there is a high level of health awareness among customers. Also, entrepreneurs who act ethically can avoid the reputational risk of scandals which accompany conventional fashion production procedures. The increasing importance of sustainable development therefore creates new opportunities for businesses but can also represent challenges for the entrepre-neurs that can be caused by for example costly sustainable actions (Hockerts & Wüstenha-gen, 2010). Especially since there have always been tensions in businesses between ethics and profits, private gain and public good, capitalism and moral beliefs, it is of relevance to investigate both in the chances as well as the challenges embedded in ethical behaviour (Vyakarnam, Bailey, Myers & Burnett, 1997).

1.2

Problem discussion

In the recent literature and also in business practices, much attention has been paid to the need for sustainable development (Brundtland, 1987), while the focus is traditionally laid on larger firms and their sustainable activities. However, due to the innovative power of entrepreneurship, newly established businesses have got the potential to work as the engine of sustainable development which can lead into a more sustainable future and thus should not be neglected in the literature anymore (Pacheco, Dean & Payne, 2010). What differen-tiates sustainable entrepreneurs from other start-up companies is their distinct value-based approach and their intention to generate social and environmental changes in society (Hockerts & Wüstenhagen, 2010). In this thesis these kind of entrepreneurs are referred to as sustainable entrepreneurs. Moreover, in this context entrepreneurs are considered as newly established companies. Entrepreneurial activities in already existing companies are not considered. Furthermore, due to their status as newcomers, entrepreneurial companies are more credible when claiming to be part of the solution rather than the problems, which are caused by the incumbents and their larger impacts on the environment (Hockerts, 2006). As a result, entrepreneurial companies are more likely to engage in sustainable en-trepreneurship than market incumbents as stated by Hockerts and Wüstenhagen (2010). This trend to focus on sustainability-related entrepreneurs is perhaps an adequate counter-trend towards the focus on large firms in existing literature on ethical behaviour and sus-tainable activities.

Despite the growing interest and enthusiasm about the positive impacts that entrepreneurs can create on sustainable development, Pacheco et al. (2010) remark that they may also be facing challenges and limitations in this approach. They state that even though sustainable business models can contribute to the collective benefit of the society, entrepreneurs them-selves may face disadvantages through acting ethically, especially if their competitors do not dedicate themselves to these high ethical standards. Also, pursuing a sustainable orientation is likely to be more difficult due to the smaller size and newcomer status of entrepreneurial companies. These might entail limited resources, a smaller network, less economies of scale and possibly less experience then well-established companies can profit from. This other side of the coin, the challenges and also the efforts and struggles to behave ethically, are usually neglected in existing research.

As stated above, the fashion industry is particularly of interest in this matter due to its large impact on society and sustainability. Also, in this industry an outspoken sustainable orienta-tion is especially relevant because of the high public visibility of the industry’s actors and their conduct with regard to sustainability. One country, which is leading in sustainability approaches in the fashion industry, is Sweden since one of the pioneers in sustainable fash-ion originates from here (The Swedish Institute, 2013). This is why Swedish entrepreneurs

in the fashion industry will be in the focus of this thesis.

This thesis aims to explore whether entrepreneurs in Sweden with a sustainable orientation perceive particular challenges with regard to their CSR activities. By finding out what spe-cific challenges Swedish entrepreneurs are facing, it will be revealed what needs to be done in order to ease the path for sustainable entrepreneurs in the fashion industry. Finally, this research might help to drive the fashion industry into a more sustainable direction by tell-ing the stories of Swedish entrepreneurs so that followers can learn from their challenges. The research is focussed on entrepreneurs which are active in the fashion industry as de-signers and retailers. In order to elaborate on these issues, interviews following a narrative inspired approach with Swedish entrepreneurs will be conducted to find out what their ex-periences are in having a sustainable orientation in the fashion industry and if they are fac-ing any challenges.

1.3

Outline

Chapter 1 Introduction: In this chapter the background of ethical behaviour

among entrepreneurs is presented and the special relevance of the fashion industry in this context is highlighted. It is followed by the problem discussion, which leads to the research question and the purpose of the thesis.

Chapter 2 Theoretical framework: This chapter provides the theoretical

background of ethical behaviour in the fashion industry as well as information on sustainable entrepreneurship. These theories are based on prior literature studies.

Chapter 3 Methodology: The third chapter presents the method which has

been used to collect data for this research. Moreover, the selection of interview partners is presented, and a description has been given how the interviews were prepared and conducted. Eventually the methods used for data analysis are described.

Chapter 4 Empirical studies: In this chapter, first the respective companies

are described and thereafter the findings derived from the empirical research are presented. The results of the interviews are presented separately for every entrepreneur.

Chapter 5 Analysis and results: Within this chapter, the interviews are

ana-lysed. Moreover, possible connections between the outcomes of the interviews are made. Conclusions were drawn based on terpretations of the outcomes.

Chapter 6 Conclusion: In chapter six the results of the research are

pre-sented, which are utilised to answer the stated problem question in the introduction.

Chapter 7 Discussion: The last chapter of this master thesis includes the

au-thors’ reflection about the thesis as well as limitations of the con-ducted research. Moreover, future research directions are addressed.

2

Theoretical Framework

2.1

Corporate Social Responsibility

2.1.1 The need for Corporate Social Responsibility

One of the greatest challenges which all businesses are facing today is the need to develop a business model that includes ethical leadership, sustainability and social responsibility with-out sacrificing profitability, revenue-growth and other measures of financial performance (Fry & Slocum, 2008; Stubbs, 2010).

Whereas in earlier times this way of business performance was only an option, it is now a must for companies to act in a socially responsible manner and to combine financial aims with caring about the environment, their employees and the local community. In order to ensure that businesses align with these rules of conduct, different international institutions have even set certain guidelines and standards during the last years as explained by Cramer (2006). Certain companies, however, go beyond what is legally required by them and en-gage in socially responsible activities not only due to rules and regulations, but also for purely ethical reasons, because it is “the right thing to do” or for instrumental reasons, be-cause it enhances their business profitability (Heal, 2010; Garriga & Melé, 2004).

Nowadays, Cramer (2006) remarks that a company cannot afford anymore to be publicly criticised due to poor working conditions, the violation of human rights or damages of the environment. Such scandals can have a major impact on the company’s image and can in-fluence the company’s perception of both external and internal stakeholders. Cramer (2006) concludes that this could result in the loss of customers and decreasing sales figures as well as the refusal of collaboration of suppliers and it could also influence the employ-ees’ loyalty. Some companies have taken this new responsibility as an opportunity and pre-sent themselves now as socially responsible actors. They make use of their socially respon-sible performance by increasing their market share, achieving cost advantages and motivat-ing their staff etc.

The ambition of combining the original financial business goals and also considering the needs of the environment and the company’s stakeholders is Corporate Social Responsibil-ity (CSR) (Cramer, 2006). This concept will be further defined in the following chapter.

2.1.2 Defining Corporate Social Responsibility

CSR is a term which has been defined in various ways in the existing literature. These varia-tions originate from the different assumpvaria-tions about what CSR implies, which varies from minor legal and economic obligations to broader responsibilities to the wider society (Ja-mali, 2008). In this thesis the view of Cramer (2006) of CSR is adopted: Companies that adopt CSR in their business practice look ahead and determine for themselves which measures of social and environmental importance they are willing and able to take. They take account for what society asks of them and choose measures which match with their own business strategy and vision. However, the entrepreneurs which are looked at in this thesis are marked by showing a more proactive approach when it comes to their CSR ac-tivities. They do not only act sustainably to an extend that is asked for by society, but their CSR performance goes beyond these expectations. Another aspect of CSR is the open communication of the company’s business practices with internal and external stake-holders.

As stated by Cramer (2006), socially responsible companies aim to find a balance between people (social well-being), planet (ecological quality) and profit (economic prosperity):

People in this context refers to both internal and external social policies. The internal

so-cial policy involves the nature of employment, such as: labour and management relation-ships, health and safety, training and education as well as diversity. The external social pol-icy includes three different categories:

1. Humans rights, such as non-discrimination, freedom of association and collective bargaining, forced labour, child labour, disciplinary practices and indigenous rights. 2. Society, which includes competing and pricing, bribery and corruption and

com-munity activities.

3. Product responsibility, which means consumer health and safety, advertising as well as the respect of personal privacy.

Planet represents the environmental impact which the company’s production activities

leave. This includes the use of scarce goods, like fuel, water or other raw materials and also the environmental impact of the supply chain, such as the transportation of goods.

Profit in the widest sense means the company’s contribution to economic prosperity, both

in a direct and indirect way. The direct impact resembles the money flow between a com-pany and its key stakeholders and also the economic impact of the comcom-pany on these stakeholders. The indirect impact means the side effects of the company’s activities due to innovation and its contribution to the gross domestic product or national competitiveness. Cramer (2006) further states that the actions a company takes with regard to these three aspects, people, plant and profit, are dependent on the company’s strategy and vision. However, the view of the outside world also plays a major role for the company’s CSR ac-tivities. Since issues such as human rights and caring for the environment are experienced differently in a global context, tensions about how the company’s actions are perceived might come up. Cramer (2006) explains that CSR does not only concern large and multina-tional companies, but is also increasingly considered by smaller companies due to the eco-nomic globalisation. Within this global network, even small companies are more and more held accountable for their actions and their supply chains. Acting in a socially responsible manner is also of importance with regard to the supply chains, which the company oper-ates in, especially if these are international relations. Companies need to consider how their supply chains can be organised in a responsible way and also who is involved in it. These questions play a role both in large and smaller companies due to the increasing internation-alisation of supply chains.

2.1.3 Corporate Social Responsibility vs. Sustainability

The concept of “doing well by doing good’’ by integrating economically relevant social and environmental issues into the company’s strategy is not only the meaning of CSR, but also resembles common definitions of a sustainable orientation (Ionescu-Somers, 2010). While some researchers restrict the term sustainability to environmental issues, others even use it as a synonym for CSR (Bansal & DesJardine, 2014).

According to James (2001) sustainable development is defined in three pillars, which cover the same topics as Cramer’s definition of CSR. The first pillar consists of “economic de-velopment”, which means the generation of wealth and is equivalent to the above stated “profit”. The pillar “environmental protection” demonstrates, just as the “planet” perspec-tive, the avoidance of environmental damage. Lastly, the third pillar “social inclusion”

re-sembles the “people” perspective, as its aim is to avoid gross inequalities of wealth, health and life chances. Also the European Commission interprets CSR as “a corporate contribu-tion to sustainable development” (Kleine & Von Hauff, 2009).

Given these common definitions of CSR and a sustainable orientation as stated above, these two terms are used synonymously within this thesis and cover both the social, the en-vironmental and the economic perspective.

2.1.4 Chances and challenges of Corporate Social Responsibility

When it comes to implementing measures of CSR in the company, it is of importance to evaluate the costs and benefits that these measures have for the company. This is of special relevance in view of the seemingly incompatible tensions between ethics and profit, private gain and the public good (Vyakarnam, Bailey, Myers & Burnett, 1997). Companies have to consider, if the often costly implementation of their sustainable orientation pays off in the end or if acting in a socially responsible way even increases sales and if there is no trade-off at all. The question is, if there necessarily needs to be a conflict between private gain and public good.

The common belief is that maximising the company’s profit does not lead to social good (Heal, 2010). This raises the question on the other hand, if achieving the social good leads to an increased profit, even though this can imply a significant consumption of the com-pany’s resources, as stated above. However, sustainability should not oppose the financial performance of the company; social and environmental goals should rather be set in addi-tion and with the aim to reach all goals together (Nita & Stefea, 2014). In the following, ways how companies can find business value in measures of CSR are discussed.

Thorpe and Prakash-Mani (2003) name as one major opportunity of adopting CSR in the company’s strategy cost savings by the reduction of the company’s environmental impact. Enhancing environmental improvements can have an immediate impact on the company’s financial performance. These savings can be generated directly by for example using less energy and materials. Thorpe and Prakash-Mani (2003) further state that another way of cost cutting are lower pollution costs in form of charges for waste handling and disposal or fines which the company needs to bear for breaking environmental regulations. Also, a re-organisation of the production processes and material flows can lead to a higher productiv-ity if for example waste volumes and the necessary labour and machine use of waste han-dling are reduced. However, Hart and Ahuja (1996) state on the contrary that in some cases a reduction of the environmental impact can only be achieved by the installation of new production systems or equipment. This often goes hand in hand with a consumption of major financial resources of the company and the question is if and when these costs will be made up for by the energy savings or increased productivity.

Another opportunity of reducing costs and increasing productivity is a responsible Human Resources Management, since this has positive impacts on the employee motivation, reten-tion and recruiting (Marin, Ruiz & Rubio, 2009). Treating employees well by implementing measures such as fair loans, a safe and clean working environment and health and educa-tional measures can enhance the employees’ motivation and productivity. Moreover, com-panies safe costs for recruitment and the training of new employees if they alter their at-tractiveness as an employer for existing employees (Thorpe & Prakash-Mani, 2003). Thorpe and Prakash-Mani (2003) further explain that companies can also increase their turnover and profit from public relations benefits by helping to develop local economies

and supporting local communities with measures such as local recruitment and local pro-duction.

CSR activities have a major impact on the company’s reputation in the eyes of consumers and regulators, which is an intangible asset, that can help the company to increase sales and attract both business partners as well as employees (Heal, 2010; Thorpe & Prakash-Mani, 2003). Even though the measurement of reputation is not as precisely possible as for other aspects of the company’s success, previous studies have shown that CSR leads to reputa-tional gains, of which the strongest component is the improvement of environmental proc-esses. The positive influence of the company’s sustainable orientation on the consumer be-haviour can be demonstrated by an example as stated by Heal (2010): Experimenters in a department store in Manhattan used two competing ranges of towels. Both were produced of organic cotton in developing countries under fair trade conditions. Despite their exem-plary degree of social responsibility, it was not labelled on the towel packages in the store. The experimenters labelled one of the towel ranges as sustainably produced products. The effects on sale of the labelled product were dramatic and sales rose over those of the com-petitors. Even when the price of the labelled products was increased by 10 %, sales contin-ued to rise. Only when the price was raised by 20 %, sales started to drop to the original level. The example demonstrates that consumers clearly favour sustainable products and are even willing to accept higher prices to a certain extent. Therefore, the sustainable orien-tation of a company can and should be used in marketing their products.

Despite the above stated opportunities, which are provided by acting in a socially responsi-ble way, sustainability does not automatically imply an increased business success as Thorpe and Prakash-Mani (2003) explain. It can contribute to the company’s success, but it can naturally not compensate a poor business practice or poor decisions with regard to marketing, production, finance or the like. Every CSR activity must be evaluated in terms of costs and benefits just like other business activities. The authors explain that it can also be the case, that minimal requirements with regard to sustainability can be the maximal ef-fort which the company is willing and able to include in its strategy. But the more CSR is integrated into the business management and its processes, the better chances and limita-tions will be understood and managed.

In existing research the portrayed companies and their efforts with regard to CSR are gen-erally large and established companies (Nybakk & Panwar, 2015), which possess enough re-sources in any kind to adapt measures of CSR. The above mentioned chances and chal-lenges therefore do not consider the company’s size or status of establishment. However, the prerequisites for entrepreneurs are quite different from those of large firms, since they generally possess less (financial) resources, produce in smaller quantities and therefore ex-perience less economies of scale, possess a smaller network of stakeholders and exex-perience less public perception, only to name a few differences. This raises the question, which role CSR plays for entrepreneurs and newly established businesses and in how far these can benefit from engaging in business in a responsible way. Before further explaining the role of CSR for entrepreneurs, sustainability will be addressed on a nationwide level for Sweden.

2.1.5 Sustainability in Sweden

As early as at the end of the 19th century, Sweden was one of the countries that developed several philosophies regarding sustainability according to Sweden’s Ministry of the Envi-ronment (2002). In the second half of the 20th century, the striving for social and eco-nomic development made place for an striving for ecologically sustainable development. Until today, Sweden’s national sustainable development strategy is based on a broad

ap-proach and contains social, economic and environmental priorities (Ministry of the Envi-ronment, 2002). Over the years, Sweden has carried out several methods to accomplish the country’s sustainable strategy. For example, more than 99 % of all household waste is recy-cled (The Swedish Institute, 2014). As they stated, Sweden has gone through a recycling revolution in the last decades, due to the fact that in 1975 only 38 % of household waste was recycled. Not surprisingly, Sweden has been voted the most sustainable country in the world in 2013 (Environmental Leader, 2013).

Also with regard to the fashion industry, Sweden undertook several steps to contribute to sustainability. In 2008 the Sustainable Fashion Academy (SFA) was founded in Sweden in response to the complex sustainability changes that the industry is facing nowadays. Know-ing that the apparel industry is very influential and that it can lead the way to a sustainable society, SFA’s vision is to help create happier people, stronger communities and a resilient planet. Therefore, SFA aims to enhance industry innovations that help realise their goal by providing knowledge and tools to leaders and entrepreneurs at different levels within the fashion industry. The founding member of SFA is H&M, supported by other leading Swedish fashion retailers like Lindex, KappAhl or Filippa K (The Sustainable Fashion Academy, 2015).

Another initiative that demonstrates that Sweden contributes to a more sustainable fashion industry is the introduction of a new research programme, joined by people from both the business sector and research community, is called Mistra Future Fashion (MISTRA, 2010). This programme’s aim is to contribute to a more sustainable society and give the Swedish fashion industry greater competitiveness and sustainable skills. Furthermore, innovative so-lutions to solve the challenges faced by the fashion industry and the society have been en-couraged. According to MISTRA (2010), fashion is becoming a cohesive programme that focuses on the following four areas: changing markets and business models, design proc-esses and innovative materials, sustainable consumption and consumer behaviour and lastly policy instruments. Moreover, the programme wants to show an industry that is facing big global and environmental challenges but is simultaneously highly creative and innovative. Outside the fashion capitals, such as Paris, London or New York, the Swedish fashion in-dustry has developed into a more and more competitive export inin-dustry in the recent years according to Hauge, Malmberg and Power (2009). Due to the fact that Sweden is a high-cost location, outsourcing to low-high-cost countries plays an important role in the Swedish fashion industry, which is known to be knowledge-based and innovation-focused. There-fore, the creation of value and profitability originates from innovative designs, brand value, efficient marketing channels as well as logistics and distribution for fashion firms in Swe-den.

2.2

Fashion Industry

2.2.1 Supply chains and market conditions

Traditionally, a distinction has been made between the fashion industry, which produces high fashion, and the apparel industry, which makes ordinary clothes or mass fashion (Ma-jor, 2013). However, by the 1970s this distinction has faded. When one refers to fashion industry in this thesis, no distinction will be made between the original meaning of the fashion industry and apparel industry and thus these terms are used equivalently.

The fashion industry is an industry exposed to several challenges, since it is characterised by short product life cycles, unpredictable demand, huge varieties in products and long and

inflexible supply chains. Therefore, an efficient supply chain management can mean the difference between either success or failure (Sen, 2008). For a long time, the fashion indus-try has reached the attention of researchers in the field of operations and supply chain management (Lowson, King & Hunter, 1999; Christopher, Lowson & Peck, 2004; Bruce, Daly & Towers, 2004), due to increasing complexity and dynamics (Brun & Castelli, 2008). Especially on the retail side the competition is strong (Newman & Cullen, 2002). For ex-ample, the scale and power of major retail buyers, the nature of sourcing and supply chain decisions which are more global in nature have contributed to this complexity (Brun & Castelli, 2008). Due to rapid changes within the fashion market, the success or failure of a company is largely based on the organisation’s flexibility and responsiveness (Christopher et al., 2004). The road towards competitiveness passes through the management of the en-tire supply chain network and thus competitive sustainable advantages through low cost or high differentiation are only reached by managing the interconnections among the actors within the supply chain (Schnetzler, Sennheiser & Schonsleben, 2007).

The supply chain of the fashion industry consists of several production segments, which were demonstrated by Sen (2008): At the top of the supply chain, fibre and yarn are pro-duced by fibre producers using natural or synthetic materials. In the second segment of the chain, fibre production takes place: raw fibres are spun, woven or knitted into fabric. The third segment of the fashion supply chain consists of the apparel manufacturers of indus-trial textile products. These manufacturers start with the design of the garment to be made. Pattern components are made from the designs, which then are used to cut the fabric. The cut fabric will then be assembled into garments, which will be labelled and shipped. Sen (2008) explains that of all segments within the fashion supply chain, the apparel segment is the most labour-intensive and fragmented. The last segment of the fashion supply chain are the retailers, who offer the apparel and other textile products to the customers. Sen (2008) also mentions that a strategic question every apparel producer asks itself is where to carry out the manufacturing operations. According to Sen (2008), many fashion producers decide on lower-cost off-shore production in for example Asia and Latin America. If the order lead time is long, retailers need to order high quantities in advance of the season’s start when little is known about customer demand (Sen, 2008). The lead time for Asian produc-tion for example can be up to several months and depends on the specific product and the place where the product is produced (Hauge, 2007).

The necessity for lower production costs and shorter lead times is driven by the ongoing trend in the industry towards a distinction between slow fashion and fast fashion. Whereas fast fashion has been characterised by the transformation of trendy design into products that can be purchased by the masses and enables through-away articles (Sull & Turconi, 2008), slow fashion encompasses slow production and consumption (Jung & Jin, 2014). Due to the strong globalisation and the increased international competition that comes along with it, companies in the fast fashion industry want to guarantee low prices, even though this requires decreasing production costs and pressure on the manufacturers. Many developing economies aim to get their share of the world’s fashion markets, even if this means lower wages and poor working conditions (Turker & Altantas, 2014). This devel-opment raises the questions to what extent fashion retailers are able to control their supply chains and guarantee sustainability.

2.2.2 Corporate Social Responsibility in the fashion industry

Over the past decade, CSR and ethical behaviour started to matter in the fashion industry (Emberley, 1998; Moisander & Personen, 2002). Sustainable development and CSR have increasingly been incorporated in governmental policy and corporate strategy (De Brito,

Carbone & Meunier Blanquart, 2008). Companies have realised that affordable and trend-sensitive fashion, while at the same time being highly profitable, also raises ethical issues (Aspers & Skov, 2006).

Due to the given characteristics of the supply chain and some specific trends the fashion industry is particularly sensitive to CSR in various ways. A high environmental impact is generated through the production process, which is marked by the intense use of chemical products and also natural resources as De Brito et al. (2008) explain. To state an example, the production of an average cotton-shirt leads to the consumption of about 2,700 litres of water (WWF, 2015). Especially the use of fibres and wool requires big amounts of water and pesticides. Synthetic fibres on the other hand are generated from non-renewable re-sources and its production requires a considerable amount of energy (Myers & Stolton, 1999). These factors are not only harmful for the environment, but the use of chemicals can also have an influence on the consumer’s health.

The search for lower production costs has furthermore led to a significant relocation of production sites to developing countries (Bonacich, Cheng, Chinchilla, Hamilton & Ong, 1994). Around 70 % of the clothes that have been imported to the EU originate from de-veloping countries (Laudal, 2010). According to De Brito et al. (2008) it has even led to the disappearance of traditional European industry, like the spinning and weaving, which led to a loss of employment in the European fashion industry. In developing countries however, low-skilled workers could easily be employed in this industry, but they are facing poor working conditions (Rosen, 2003). These poor working conditions are even enhanced by the constant price pressure that the industry is facing and that is passed on through the dif-ferent production stages as described above.

Another impact globalisation has on sustainability are the increased transport distances, which is the reason why the fashion industry accounts for 4 % of the worldwide exports (World Trade Organization, 2008). Goods need to be shipped all over the world until they have undergone all production stages, which entails an immense consumption of fossil-fuels. Due to different trends in the fashion industry, short product life-cycles and the im-portance of responsiveness, which lead to smaller quantities of deliveries and shorter deliv-ery times, this impact on transportation has even increased (De Brito et al., 2008).

Obviously, companies are aware of their responsibility to society: they have recognised the importance of their supply chain partners in managing the environment (Vachon, 2007; Bai & Sarkis, 2010). Consumers and the society ask for a greater level of responsibility and transparency in the way products are produced, distributed and sourced (MacCarthy & Jayarathne, 2012). Public pressure on companies to act responsibly increases both socially and environmentally (McKinsey, 2008). Therefore, fashion companies increasingly focus on sustainability and have the aim to ensure sound working and production conditions through their supply chains. Increased attention to sustainability has been caused by eco-nomic, social and environmental problems in developing countries (Turker & Altantas, 2014). As they stated, the tension in the exchange of resources between developing and de-veloped countries lies at the heart of sustainable activities.

The upcoming globalisation entails more trade-offs for the industry: the global network of retailers, wholesalers, agents, contractors and sub-contractors makes the fashion supply chain extremely complex and difficult to control (Emmelhainz & Adams, 1999; Giesen, 2008; MISTRA, 2010). According to Langhelle, Blindheim, Laudal, Blomgren and Fitjar (2009), the fashion industry is questionably known for having supply chains that are diffi-cult to keep track of. The longer the supply chain is, the harder it will be for the retailer to

ensure and take responsibility that all production processes are in line with their CSR stan-dards.

Due to the outsourcing of processes to developing countries across the world, fashion brands and retailers are at risk of losing track of the channels in their fashion supply chain. Transparency and traceability could provide another way to large-scale sustainability, which allows the consumer to easily see where their fashion is really from and compare the sus-tainability of different brands (The Guardian, 2013). In order to enhance the desirable visi-bility of their sustainable orientation, fashion retailers start focusing on eco-labels and other sustainable approaches. Fashion companies are aware of the critical eye of the public upon their activities, and thus they can benefit from this critical overview by carrying out new strategies as eco-labels and standards, environmental and social audits, partnering, commu-nities of practice, fair trade and clean transport modes (De Brito et al., 2008). Several com-panies have introduced a variety of initiatives in order to deal with the negative social and environmental impact of fashion, for example by promoting fair trade cotton, launching traceability programmes in the supply chain and introducing labelling schemes for envi-ronmentally friendly laundry and drying (DEFRA, 2010). Other ways of ensuring ethical conduct are labels that commit to minimum labour standards and fashion made from recy-cled material (Domeisen, 2006).

2.2.3 Institutionalisation of Corporate Social Responsibility

Institutional pressures play a critical role in explaining the establishment of CSR in organi-sations facing social and environmental demands from a variety of stakeholders, like gov-ernment authorities, industry organisations and non-govgov-ernmental organisations (Bitzer & Glasbergen, 2010; Campbell, 2007; Hoffman, 2001; Joyner & Payne, 2002; Matten & Moon, 2008; Quazi, 2003; Wright, Smith & Wright, 2007). Institutional pressures are de-fined as social, legal and cultural forces outside the organisation that exert influence on how the companies perceive the environment and how they eventually determine strategic actions (Menguc, Auh & Ozanne, 2010). Furthermore, many new labels, certifications, guidelines and multi-stakeholder initiatives have also contributed to an infrastructure of CSR that puts pressure on organisations to address the impact of their activities on society (Waddock, 2008).

For entrepreneurs, this trend towards an institutionalisation of sustainability may entail both chances but also disadvantages. On the one hand, it might bring the advantage that competitors are now forced to engage in CSR activities. On the other hand, a sustainable orientation in certain aspects of the business can result in higher costs for e. g. cleaner pro-duction methods, which can be a challenge for an entrepreneur who does not possess the same amount of resources as a large and well-established company has. An institutionalisa-tion of sustainability could also be realised by granting entrepreneurs loans and subsidies when they start their business with a sustainable approach. This could serve as an incentive to increase CSR in the industry.

Since the world is facing the devastating impact of climate change and an increasing atten-tion towards corporate sustainability develops, the world needs innovators that lead the way towards more sustainable solutions (United Nations Global Compact, 2012). Accord-ing to the United Nations (UN) Global Compact, the fashion industry has the potential to be such an innovator, working proactively to address critical social, environmental and ethical challenges on a global scale. The UN Global Compact is a strategic policy initiative for companies that are committed to aligning their operations and strategies with ten prin-ciples which are universally accepted in the area of human rights, environment, labour and

anti-corruption. In order to make the fashion industry a leading innovator on sustainability, the UN and the Nordic Initiative Clean and Ethical have combined forces in order to en-sure that the fashion industry will be the first-ever sector-specific initiative under the UN Global Compact (Pedersen & Gwozdz, 2014). The Nordic Initiative Clean and Ethical (NICE) is a joint venture by the fashion industry in the Nordic countries, which is led by the Nordic Fashion Association and targets the global fashion community. The main goal of the Nordic Initiative Clean and Ethical is raising awareness and promoting business practices which are sustainable and responsible, as stated in the UN Global Compact (2012). The strong alliance between the fashion industry (which is represented by the net-work organisation Danish Fashion Institute with its Nordic partners) and the UN enables one the of largest industries in the world to move towards a more sustainable future (United Nations Global Compact, 2012).

Another organisation which is driving the change towards a more responsible treatment of human and labour rights, also in the fashion industry, is the International Labour Organiza-tion (ILO). The aim of ILO (2015) is the promoOrganiza-tion of social justice and internaOrganiza-tionally recognised human and labour rights. They help to enhance the establishment of decent work and working conditions, thereby contributing to lasting peace, prosperity and pro-gress for working and business people. In Bangladesh, the breakdown of a garment factory in April 2013 led to a range of local institutionalisation in this industry as demonstrated by Miller (2014). After the breakdown of the garment factory, several mainly European retail chains changed their approach of purchasing products which were produced under unsafe working conditions and signed a legally-binding agreement, the so-called Accord on Fire and Building Safety, in order to enhance the work safety in the manufactories.

2.3

Sustainable entrepreneurship in the fashion industry

2.3.1 Entrepreneurs in the fashion industry

The fashion industry is a dynamic and demanding sector that is marked by a high level of competition. Therefore the existing literature on entrepreneurship assumes that entrepre-neurs in the fashion industry need a high level of innovativeness in order to create a com-petitive advantage, as stated by Ünay and Zehir (2012). They remark that innovation is a continuous and nearly infinite process in the fashion industry, since the market is always in need for new products. This gradual process is also applicable to the start-up of a new fash-ion business according to Mills (2011). Often entrepreneurs who have just started their business generate their first sales to friends and family and so their business only evolves slowly over time from this point. This is due to the fact that the advertisement and promo-tion of their clothes takes time, money and a certain set of skills. Also, the beginning of a newly started business is commonly marked by a lack of visibility of the designers or retail-ers and their labels. Entrepreneurs often invest their usually scarce resources rather in the creation of design or purchasing materials and equipment and they possess a less developed network than established firms in the industry.

According to Ünay and Zehir (2012) the innovative perspective of entrepreneuring in the fashion industry can be classified into the “product innovation” and the “business opera-tions” dimension. Product innovation is related to creating a strong brand and innovative and competitive products. Future trends in the fashion industry are more and more focus-sing on the benefits of smart clothing solutions from technological, human and competi-tion perspectives. Also at the Swedish School of Textile at the University of Borås re-searchers are working on smart textiles, where the main focus is to explore and develop

new expressions, new materials and constructions in textile design (University of Borås, 2012). Such cases of knowledge-intensive innovations, as Ünay and Zehir (2012) mention, include for example bio-monitoring clothing that supervises the wearer’s bodily functions. The innovation of such smart clothes have the power to evoke worldwide trends, methods and strategies. The second dimension, business operations, is concerned with innovative processes within the company, like marketing techniques, but also the management of the supply chain. Integrating CSR activities into the business operations and making the busi-ness more sustainable is another way of innovation. By recognising this opportunity, entre-preneurs in the fashion industry can find their niche and innovative business model which makes them unique and serves as their competitive advantage.

2.3.2 Sustainable entrepreneurs

The term entrepreneurship is marked by a wide range of existing definitions in the litera-ture. One aspect of its definition, which is of relevance within this thesis is the creation of a new enterprise as stated by Low and MacMillan (1988). In contrast to entrepreneurial proc-esses, which take place in already existing companies through for example new product in-novations, the entrepreneurs examined in this thesis are the founders of their own busi-nesses. Shane (2003) mentions another facet, which is the discovery of opportunity. Ac-cording to his definition, entrepreneurship means to discover, evaluate and exploit oppor-tunities with the purpose of introducing new goods and services, processes or a whole new market. The recognition of new opportunities can also be applied to the inclusion of CSR in the companies’ strategy and is therefore of relevance for understanding of entrepreneur-ship in this thesis.

While most of the existing literature on sustainability and CSR is focused on existing busi-nesses, a significant element of moving towards a sustainable future is the establishment of businesses by entrepreneurs, which adopt a sustainable orientation right from the founda-tion of the company (Walley & Taylor, 2002). These entrepreneurs who engage in CSR ac-tivities shall in the following be called “sustainable entrepreneurs”, as this term is widely used in the existing literature. Within this thesis, the definition of sustainable entrepreneurs as stated by Cohen and Winn (2007) is adopted. They characterise a sustainable entrepre-neur as seeking to understand how opportunities can be discovered, created and exploited to bring into existence future goods and services, while at the same time considering eco-nomic, social and environmental consequences. This also corresponds to Schumpeter’s (1987) approach of a sustainable entrepreneur seeing unsustainable conditions as occasions of creating new products and services. These entrepreneurs are motivated by their own personal values and the intention to cause social and environmental changes in the society (Schaltegger & Hansen 2013; Hockerts & Wüstenhagen, 2010). According to Hockerts and Wüstenhagen (2010) sustainable entrepreneurs even have the power of initiating the trans-formation of an entire industry into a more sustainable state and they observed that more and more sustainable businesses are founded, when an industry is under increasing pressure of adopting a sustainable orientation. These entrepreneurs are therefore often seen as the engines of sustainable development due to their innovative power and ability of discover-ing of opportunities (Pacheco et al., 2010). Within this thesis, the studied entrepreneurs do not necessarily follow a complete sustainable approach in every aspect of their business. However, all of them engage in certain CSR activities and can therefore share valuable ex-periences with their sustainable orientation and regarding challenges they perceive while adopting and following this orientation.

kind of organisation, entrepreneurs have a higher tendency of adopting these. This is due to the fact that different dynamics are established within businesses, depending on if it is in the hands of one person which is guided by his or her beliefs, or if a company is run by managers who do not own the business and therefore have less personal influence (Vya-karnam et al., 1997). As argued by Buchholz and Rosenthal (2005), entrepreneurship and an ethical orientation are closely connected, since successful entrepreneurship requires skills such as imagination, creativity, novelty and sensibility, which are also considered as relevant for ethical decision-making.

Despite their innovative and positive standing in the sustainable development of industries, sustainable entrepreneurs are also facing challenges and limitations in their CSR activities. Even though they attract a number of customers who care about sustainability issues, these entrepreneurs often fail to reach a broader mass market as explained by Hockerts and Wüstenhagen (2010). Sometimes they do not even have the intention to grow and rather remain a niche in their industry. The authors explain that this decision can be made upon the idealistic reason to keep their high environmental and social standards or to prevent bigger incumbents, who could easily outspend the entrepreneurs in their CSR activities from entering their niche. A challenge sustainable entrepreneurs may also face is that a sus-tainable business model may serve a collective benefit but can become an obstacle for the entrepreneurs themselves, when they have to bear costs for their CSR activities which are not borne by their competitors (Pacheco et al., 2010). This pursuit of a sustainable orienta-tion can also become a drawback when the entrepreneur becomes obsessed with one sus-tainable issue and invests the limited resources into optimising only one social or environ-mental issue (Hockerts & Wüstenhagen, 2010).

2.4

Summary

As displayed in the previous chapters, the fashion industry is underlying several influences that have increased the need for CSR. Supply chains are becoming more and more complex due to the ongoing globalisation and an increased price pressure. This all does not only have an impact on society, but also on the environment. Recent incidents have led to more institutionalisation of CSR within the fashion industry, but it is still a long way to go until all companies will have to include CSR in their business activities. All these latest develop-ments in the fashion industry show that nowadays CSR activities in the fashion industry have become inevitable. However, not all companies have adopted a sustainable orientation yet. As explained above, the innovative power of entrepreneurs can provide an opportunity to be the changing force in the fashion industry towards more CSR.

The chances of a sustainable orientation have been thoroughly discussed in the existing lit-erature and it is without doubt that not only the environment and society can benefit from a sustainable orientation of companies in the fashion industry, but also the businesses themselves. Few research however is available on the challenges that companies are facing when they adopt a sustainable approach with their business. Further examination can there-fore help to reveal if entrepreneurs in Sweden with a sustainable approach are facing any challenges. By investigating entrepreneurs’ stories and their experiences, the thesis can help new entrepreneurs that want to start their business with a sustainable orientation to be bet-ter prepared for this kind business approach. Also, it may serve to drive the fashion indus-try into a more sustainable direction.

3

Methodology

3.1

Research design

3.1.1 Qualitative study

The study is of exploratory nature and it aims to find out what is happening in the fashion industry in Sweden with regard to CSR, to seek new insights in this topic and to assess the phenomenon of CSR in the fashion industry in a new light. Furthermore the thesis intends to also find out why something is happening and to gain an understanding of the meanings that humans attach to certain events (Saunders, Lewis & Thornhill, 2009). An exploratory research was compared to the activities of a traveller or explorer by Adams and Schvane-veldt (1991) due to this investigative character. The advantage of a qualitative research is the flexibility and adaptability to a change of direction in case new results of data appear and new insights occur (Saunders, Lewis & Thornhill, 2009). Within this thesis an interpre-tivist view on reality is adopted. As Saunders et al. (2009) state, this implies that reality is socially constructed and subjective. Social phenomena are created from the perceptions and consequent actions of social actors, which were explored within this thesis. When conduct-ing a research the most crucial step is to decide on the research methods that are used for the study. The thesis aims to investigate the challenges that Swedish sustainable neurs are facing in the fashion industry. Therefore, the experiences of Swedish entrepre-neurs were analysed. To do so, a qualitative research approach was chosen to capture the stories of the entrepreneurs, since a qualitative study gives the opportunity to explore a subject in a manner that is very close to reality (Robson, 2002). The reality here means the subjective experiences of the entrepreneurs following their sustainable business approach.

3.1.2 Narrative analysis

As Fisher (1987) remarks, life is experienced and interpreted through a series of ongoing narratives, which contain conflicts and characters and consist of beginnings, middles and ends. The language that is produced during interview can be taken as stories, which display interpretations of certain aspects in the world, which occur in a specific time and are shaped by history, culture and character (Fisher, 1995). Narratives are a qualitative research approach, which has in recent times been used to enhance our understanding of entrepre-neurial processes and experiences (Steyaert & Hjorth, 2003).

This thesis is inspired by a narrative approach, which means that the stories behind the en-trepreneurs were investigated in order to gain in-depth insights into the topic of CSR in the fashion industry. The entrepreneurs were asked regarding their experiences in having a sus-tainable orientation in the fashion industry in order to find out if they are facing any chal-lenges with their sustainable approach. Through the structure and the conceptual content of the entrepreneurs’ stories, their sense of reality was revealed, showing who they think they are and their notions of purposeful activity (O’Connor, 2002). By capturing their nar-ratives, the writers of the thesis did not only gain access to the chronology of actions the entrepreneurs took, but also the context in which they occurred and their reasons for en-gaging in them, as well as the sense which was made of the resultant experiences (Søder-berg, 2006). Entrepreneurs as smaller players in this large industry might be facing different challenges than larger companies when they aim to include CSR into their business model, which makes them an interesting subject to explore. Therefore the thesis intends to re-search the movement in the fashion industry towards a more sustainable approach from the point of view of these businesspeople. To investigate the topic profoundly and to learn

more about their experiences, different case studies of Swedish entrepreneurs were con-ducted.

According to Coffey and Atkinson (1996), a narrative can be broadly defined as an account of an experience which is told in a sequenced way. It indicates a flow of events, which all together are of significance for the storyteller and are supposed to transmit a meaning to the researcher. Understanding and meaning are thereby conveyed through analysing data in their originally told form rather than fragmenting them through developed codes or catego-ries as explained by Saunders et al. (2009). However, it is still possible to further group nar-ratives. It was also stated by Clandinin and Connelly (2000), that experiences are the key when it comes to narrative inquiries, highlighting the meaning of continuity, which comes up when experiences grow out of other experiences and so forth. This means the creation of a coherent story from the collected interview-data. A narrative therefore allows to main-tain the participants’ engagement, events, actions they took and consequences that followed within the narrative flow while at the same time considering the social and organisational context within the events took place (Saunders et al., 2009). This implies that the partici-pants’ stories and the ways in which they tell these with their subjective interpretations is based on the constructions of the social world in which they live, which must be taken into account when analysing the interviews. The data of narratives is usually collected through semi- or unstructured interviews and the participant are encouraged to tell their story in their own way, explaining why it took the form it did, while leaving them free from any structured set of questions (Mills, 2011). The requirements for accuracy are often consid-ered as less important than the experiences that are told, what they symbolise and how they display particular issues of for example organisational politics, culture and change (Gabriel & Griffiths, 2004).

3.2

Data collection

3.2.1 Choice of entrepreneurs

In the fashion industry, Sweden has been leading in sustainable approaches. One of the pioneers of sustainable fashion in Sweden is Gudrun Sjödén, who launched her company Gudrun Sjödén in 1976 (The Swedish Institute, 2013). Gudrun Sjödén’s business idea was to produce colourful home textiles and clothes in natural materials and thus environmental thinking was part of all collections she made. More generally, sustainable fashion is impor-tant to many fashion designers in Sweden (The Swedish Institute, 2013). Due to the fact that sustainability has been considered by many fashion designers in Sweden, the focus of this research is both Swedish entrepreneurs that have started their fashion production with a sustainable approach and Swedish entrepreneurs who retail sustainable fashion.

The selection of participants was of purposive nature, meaning that the judgement of the writers of the thesis had been used to select the cases that make up the sample (Saunders et al., 2009). This way it could be ensured that the participants could contribute to the fulfil-ment of the purpose of the thesis. Since this research focuses on the challenges faced by Swedish entrepreneurs, both entrepreneurs having a sustainable production approach with regard to fashion as well as those who retail sustainable fashion, research has been done about potential Swedish entrepreneurs. Several sources have been consulted in order to se-lect applicable candidates for this research, for example the Swedish Entreprenör magazine, contacts established with entrepreneurs during previous courses have been exploited, and the internet was used to find suiting participants. While searching for candidates, several criteria were taken into consideration. One criteria was the sustainable focus of the com-pany, for example the use of natural materials, recycled materials, the durable quality of

clothes and the focus on good working conditions. As mentioned before, in this thesis en-trepreneurs are considered as newly established companies. According to Hauge (2007), fashion companies which are considered as relative newcomers to the market, range from having two till fifteen years in the business. Therefore, the timeframe that was considered as relevant for this research with regard to the existence of the fashion business, has been defined from zero till fifteen years. These criteria have led to the selection of several entre-preneurs wherein the below mentioned companies have participated.

Table I: Participants of this study Name of

interviewee Company Type of business Year of foundation Number of employees Date Interview method Selection cri-teria

Lotta

Spykman Just Africa Retailer 2001 3 01.04.2015 Email Fair trade Elisabeth

Gudmundson Uma Bazaar Retailer 2005 4 01.04.2015 Telephone Organic mate-rials, fair trade Maja

Svensson ELSA AND ME Designer 2012 3 06.04.2015 Telephone Sustainable cotton, work-ing conditions Klara

Gardtman Mini Rodini Retailer 2006 51 28.04.2015 Email Sustainable materials Peter Arneryd Nerdy by

Nerds Designer 2011 5 10.04.2015 Telephone Social aspect, durable mate-rial

3.2.2 Interview settings

In order to align with the exploratory purpose of this research, the execution of face-to-face interviews was intended. However, face-to-face-to-face-to-face interviews turned out not to be feasi-ble due to time and location restrictions. In an exploratory study, in-depth interviews can be a useful tool to find out what is happening and to understand the context (Saunders et al., 2009). As they state, in unstructured interviews there is no predetermined list of ques-tions to work through during the interview, although one needs to have an idea about which aspect you want to explore. Moreover, the interviewee gets the opportunity to talk freely about events, behaviour and beliefs in relation to the topic area. Therefore, this un-structured interview setting corresponds perfectly with the narrative inspired approach of this research. As face-to-face interviews turned out not to be feasible, it was decided to fo-cus on telephone interviews, where email interviews have been considered sufficient in case participants could not arrange a telephone interview. As stated by Carr and Worth (2001), phone interviews permit researchers to take notes discretely, whereby conversations could take place more naturally. Moreover, “qualitative telephone data have been judged to be rich, vivid, detailed, and of high quality’’ as defined by Novik (2008, p. 393).

As mentioned before, in some cases participants took part in email interviews, due to time limitations. Here, the participants received a full range of interview questions, where only questions applicable to their business have been answered. As stated by Morgan and Sy-mon (2004), email communication may last for some weeks since there is a delay between a question being asked and the question being answered. As they state, this can be advanta-geous as it allows both the interviewer and interviewee to reflect on the questions and