Communication for Development One-year master

15 Credits

Spring 2019 (Submitted March 2019) Supervisor: Kersti Wissenbach

Communicating Antibiotic Resistance to the Public

How effective was Public Health England’s 2018 ‘Keep Antibiotics Working’ campaign TV advertisement at increasing public understanding of antibiotic resistance and

motivating a change in antibiotic seeking behaviours?

Abstract

Antibiotic resistance is one of the greatest global threats we face today. Human overuse of antibiotics is a contributing factor and major behaviour change around antibiotic consumption is needed, but several challenges exist in communicating antibiotic resistance to the public. In 2018 the UK Government relaunched a national television advertisement as part of the ‘Keep Antibiotics Working’ campaign which aimed to raise awareness of antibiotic resistance and reduce public demand for antibiotics. This study evaluates what role the framing of antibiotic resistance in the advertisement played in increasing public understanding of antibiotic resistance and motivating behaviour change. The study is grounded in behaviour change and health communication theory from the field of Communication for Development, and health and social psychology theory, reflecting the need for multidisciplinary approaches to addressing antibiotic resistance. A textual analysis identified how the issue was framed in the advertisement and surveys and interviews were conducted with members of the target audience groups to analyse what effect the advertisement had on their understanding of, and attitude towards antibiotic resistance. The findings show that the framing of antibiotic resistance in the TV advertisement led to an increase in misunderstandings of what becomes resistant to antibiotics. The advertisement was helpful in highlighting the vulnerability of antibiotics and for creating a new social norm around being a responsible antibiotic user, however was interpreted as childish by participants. It did not communicate the severity of antibiotic resistance or specific risk of antibiotic overuse to the audience, or accurately reflect the audience’s existing knowledge of antibiotic resistance and current behaviours. As the severity of antibiotic resistance was not conveyed, the advertisement did not motivate a change in antibiotic seeking behaviours or attitude amongst the majority of participants. The findings did highlight knowledge gaps amongst study participants including the importance of completing a course of antibiotics as prescribed, and that it is the bacteria itself, not the person, that develops resistance, and hopes this research can inform the development of future campaigns.

Key words: Antibiotic resistance, health communication, behaviour change, Communication

Table of Contents

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ... 5

-1. INTRODUCTION ... 6

-2. BACKGROUND CHAPTER ... 9

-2.1 DEFINING THE ISSUE OF ANTIBIOTIC RESISTANCE ...-9

-2.2 GLOBAL RESPONSE TO RISING ANTIBIOTIC RESISTANCE ...-11

-2.3 CHALLENGES OF COMMUNICATING ANTIBIOTIC RESISTANCE ...-11

-3. UK CASE STUDY SELECTION ... 13

-3.1 ‘KEEP ANTIBIOTICS WORKING’CAMPAIGN ...-14

-3.2 CASE STUDY SELECTION ...-15

-4. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK ... 16

-4.1 HEALTH COMMUNICATION ...-16

-4.2 MASS MEDIA CAMPAIGNS ...-17

-4.3 BEHAVIOUR CHANGE COMMUNICATION ...-18

-4.4 CRITICISMS OF BEHAVIOUR CHANGE COMMUNICATIONS...-19

-4.5 HEALTH BELIEF MODEL ...-20

-4.6 THE USE OF FEAR IN HEALTH COMMUNICATION ...-20

-5. RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODOLOGY ... 21

-5.1 STUDY INDICATORS ...-21

-5.2 SAMPLING ...-22

-5.3 TEXTUAL ANALYSIS ...-24

-5.4 SURVEY RESEARCH ...-25

-5.5 SURVEY DATA CATEGORIZATION ...-26

-5.6 SEMI-STRUCTURED INTERVIEWS ...-26

-5.7 THEMATIC ANALYSIS OF INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPTS ...-27

-5.8 STUDY LIMITATIONS ...-27

-6. ANALYSIS AND DISCUSSION OF FINDINGS ... 28

-6.1 HOW ARE THE CAUSES, CONSEQUENCES OF, AND SOLUTIONS TO ANTIBIOTIC RESISTANCE BEING COMMUNICATED TO THE PUBLIC IN THE TV ADVERTISEMENT TO CHANGE ANTIBIOTIC SEEKING BEHAVIOURS? ...-28

-6.1.1 Findings on audience reaction to the framing of antibiotic resistance in the TV advertisement ... 29

-6.1.2 Findings on the narrative of antibiotics conveyed in the advertisement ... 30

-6.1.3 Findings on the level of information communicated in the TV advertisement ... 30

-6.2 WHAT EFFECT DOES THE TV ADVERTISEMENT HAVE ON MEMBERS OF THE TARGET AUDIENCE’S ATTITUDES TOWARDS, AND UNDERSTANDING OF ANTIBIOTIC RESISTANCE? ...-31

-6.2.1 Findings on how the TV advertisement promoted a social norm of responsible antibiotic usage 31 -6.2.2 Findings on audience reaction to how the risks of antibiotic resistance were communicated in the TV advertisement ... 32

-6.2.3 Findings on the level of fear the TV advertisement incited in the audience ... 33

-6.2.4 Findings on the TV advertisement’s engagement with the audience’s current behaviours - 34 -6.3 DOES THE TV ADVERTISEMENT CHALLENGE OR REINFORCE MISUNDERSTANDINGS ABOUT ANTIBIOTIC RESISTANCE? ...-36

-6.3.1 Findings on the TV advertisement’s reinforcement of misunderstandings of AMR ... 36

-7.1 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH ... -39

REFERENCES ... 40

APPENDIX 1: SELECTION OF CATEGORIZED SURVEY RESPONSES... 46

APPENDIX 2: SELECTION OF CODED INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPTS ... 50

-Abbreviations and Acronyms

AMR Antimicrobial Resistance

APUA Alliance for the Prudent Use of Antibiotics

BCC Behaviour Change Communication

C4D Communication for Development

CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

DOH Department of Health

ECDC European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control

EU European Union

GAPAR Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance

GP General Practitioner

HBM Health Belief Model

HC Health Communication

HIC High Income Countries

KAW Keep Antibiotics Working

LMIC Low and Middle-Income Countries

MEP Measure Evaluation Project

NHS National Health Service

PHE Public Health England

SBCC Social and Behaviour Change Communication

STI Sexually Transmitted Infection

TB Tuberculosis

UK United Kingdom

UN United Nations

UNICEF United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund

USAID United States Agency for International Development

1. Introduction

“Antimicrobial resistance poses a catastrophic threat. If we don’t act now, any one of us could go into hospital in 20 years for minor surgery and die because of an ordinary infection that can’t be treated by antibiotics.”

-Dame Sally Davies, England’s Chief Medical Officer, 20131

The World Health Organization (WHO, 2018a) has declared that antibiotic resistance is ‘one of the biggest threats to global health, food security, and development today’. Antibiotic resistance occurs when a bacteria is able to resist the effects of an antibiotic designed to control or kill it, causing the bacteria to continue to multiply and grow. Resistance to antibiotics is present in every country globally (WHO, 2018b), and it’s estimated that drug-resistant ‘superbugs’ could cause ten million deaths a year by 2050 (Kraker et al, 2016, p.1). Antibiotic resistance has the potential to undermine modern medicine (WHO, 2018a), and in 2017 we witnessed the death of a women in Nevada, USA, after developing a bacterial infection that was resistant to 26 types of available antibiotics (McCarthy, 2017).

From the depths of the Amazon, to the suburbs of London, antibiotic resistance poses a risk to every person on the planet, as it’s the bacteria that becomes resistant to antibiotics and this resistant bacteria can pass between people (Alliance for the Prudent Use of Antibiotics, n.d.). Therefore, even if an individual uses antibiotics correctly, they are still at risk of contracting an infection that is antibiotic resistant, particularly in a globalized world where people and infectious diseases are able to travel great distances quickly (Smith and Coast, 2002, p.126). This makes antibiotic resistance a priority for every nation, and a coordinated global response is required as ‘no country acting on its own can adequately protect the health of its population against AMR’ (Ibid.).

If antibiotic overuse is not halted, we could be propelled into a post-antibiotic era in which minor infections could lead to death. High Income Countries (HICs) are still the biggest consumers of antibiotics (Klein et al., 2018), and human overuse is a leading contributor to rising resistance. Increasing public understanding of the issue and changing antibiotic using behaviours is crucial to avoiding the continued rise of antibiotic resistance (WHO, 2015b, p.4). We are in a global ‘race against time’, and ensuring that health communication aimed at promoting behavioural change and increasing knowledge of antibiotics is effective is crucial. This is supported by evidence collected by the EU Eurobarometer 2016 survey, a survey exploring European public reaction to a subject, which shows that consumption of antibiotics decreases as knowledge of AMR increases (Barber and Swaden-Lewis, 2017, p.21).

Major behaviour change around antibiotics is needed, and the UN has recognized public awareness of the issue as key to achieving change. A 2018 WHO report (WHO, 2018d, p. 12)

1England’s Chief Medical Officer Professor Dame Sally Davies cited in a press release on the 2013 Department

of Health and Social Care Annual Report available at: <

highlighted that ‘most countries have not yet launched nationwide, government supported campaigns on AMR awareness in human health’, and researchers note that even nations that have implemented campaigns have had limited success (Littmann, 2015, p 215). Although much research exists on implementing health campaigns in general, little research has been conducted into mass media campaigns focused specifically on antibiotic resistance, and few evaluations exist of the effectiveness of messaging in campaigns to understand what is, and crucially, what is not, working.

In recent years the UK has played a leading role in the fight against antibiotic resistance. In 2018 the national ‘Keep Antibiotics Working’ (KAW) campaign, led by Public Health England (PHE), a government agency which aims to protect Britain’s health, relaunched between October and December 2018 (PHE, 2018c) with the aim of addressing public lack of understanding of antibiotic resistance and reducing antibiotic seeking behaviours. A key campaign material was a TV advertisement which was shown on national television and was chosen as the focus of this study due to its visibility to a large audience. How an issue is framed can have a significant effect on audience reaction to a topic, and evaluation of mass media campaigns is core to behaviour change communications (BCC) (Tull, 2017, p.6), therefore, it’s important to evaluate whether the framing of antibiotic resistance in the advertisement was effective in achieving the campaign’s aims.

In January 2019 the UK government released a five year National Action Plan and report to address antibiotic resistance which outlines an ambition as to engage the public on the issue and develop societal advocacy by identifying ‘the most effective communication channels to fully engage the public on all aspects of antimicrobial resistance’ (HM Government, 2019a, p.11). The plan outlines actions which include ‘survey public attitudes to and awareness of AMR and self-reported behaviours […] to assess the impact of national public health campaigns’ (HM Government, 2019b, p.34). This makes this study highly topical as it has surveyed public attitudes to antibiotic resistance and self-reported behaviours, and evaluated the effectiveness of the 2018 KAW campaign’s TV advertisement in engaging the public on antibiotic resistance and motivating behaviour change.

The field of Communication for Development (C4D) has moved away from only focusing on the Global South, towards recognizing the global interrelatedness of inequalities. Antibiotic resistance is a health issue affecting every nation and requires mass action. Strands of C4D including health communication and behaviour change theory provide a framework for promoting and evaluating behaviour change amongst populations, therefore a study focused on antibiotic resistance communications, grounded in BCC theory is an appropriate area of study within C4D. Furthermore, in 2018, extreme poverty levels in the UK were investigated in a UN inquiry.2 A link has been proven between poverty and rates of AMR3 and rising

2 In November 2018 Professor Philip Alston, United Nations Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and

human rights, gave a statement on his visit to the UK which highlighted that ‘a fifth of the population, live in poverty.’ The full statement can be found here:

<https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=23881&LangID=E >. (Accessed 13th January 2019

3 On 24th January 2019 the UK Government released a report outlining a 20 year vision for antimicrobial

resistance. The report notes that the World Bank estimates ‘an additional 28 million people could be forced into extreme poverty by 2050, through shortfalls in economic output, unless resistance is contained’ (UK Government, 2019a, p.4), highlighting the importance of this link between poverty and AMR

antibiotic resistance in the UK could have devastating effects on the nation’s poorest, making the KAW TV advertisement a relevant C4D case study with recognition that development issues are not confined to the ‘developing’ world.

This study aims to contribute to the field by exploring how to effectively communicate antibiotic resistance to the public in a way that can increase knowledge and awareness of the issue and promote behaviour change around antibiotic consumption. This study is not concerned with campaigner intent, but with the effect the advertisement had on the target audience. The theoretical framework adopts a multidisciplinary perspective combining health and behaviour change theory with social psychology theory, reflecting the need for multidisciplinary approaches to addressing antibiotic resistance. In particular, this study evaluates public reaction to the framing of antibiotic resistance in the TV advertisement and what effect it had on members of the target audience in increasing knowledge and reducing antibiotic seeking behaviours. This study will centre on the following research question:

What role does the framing of antibiotic resistance in Public Health England’s 2018 TV advertisement, part of the ‘Keep Antibiotics Working’ campaign, play in increasing understanding of antibiotic resistance and encouraging behaviour change amongst the target audience?

Additional questions guiding this research are:

1. How are the causes, consequences of, and solutions to antibiotic resistance being communicated to the public in the TV advertisement to change antibiotic seeking behaviours?

2. What effect does the TV advertisement have on members of the target audience’s attitudes towards, and understanding of antibiotic resistance?

3. Does the TV advertisement challenge or reinforce misunderstandings about antibiotic resistance?

The crux of this research was to evaluate if participants demonstrated a change in knowledge and awareness of antibiotic resistance and intent to change antibiotic seeking behaviours after seeing the advertisement. The study incorporates interviews, survey research and a textual analysis. Interviews and surveys were conducted with members of the campaign’s target audience to understand their interpretation of the TV advertisement, and the advertisement’s effectiveness in achieving its aims. A textual analysis of the advertisement showed how antibiotic resistance was framed in the advertisement.

This paper is structured into seven chapters. Following the introductory chapter, chapter two gives background information on antibiotic resistance. Chapter three discusses why a UK focus was chosen and introduces the case study. Chapter four outlines the theoretical framework in which this study is grounded, whilst chapter five describes the research design and methodology. Chapter six discusses the study findings and chapter seven, concludes with a summary of the study findings and suggestions for future research.

2. Background Chapter

This chapter outlines the background information that informs the study and highlights why it’s crucial to ensure health communication addressing antibiotic resistance is effective, by exploring the spread and consequences of resistance, communication challenges, and global response.

2.1 Defining the Issue of Antibiotic Resistance

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is ‘the ability of a microorganism (like bacteria, viruses, and some parasites) to stop an antimicrobial (such as antibiotics, antivirals and antimalarials) from working against it’ (WHO, 2018b). Antibiotic resistance relates specifically to antibiotic effectiveness in the prevention and treatment of bacterial infections, with resistance occurring ‘when bacteria change in response to the use of these medicines’ (WHO, 2018a). This can lead to the bacteria developing the ability to combat the antibiotics designed to kill them, meaning the bacteria can multiply (CDC, n.d.). Although some bacteria have a natural resistance to certain antibiotics, bacteria become resistant to antibiotics either via rare genetic mutation, or, as outlined by the Alliance for the Prudent Use of Antibiotics (APUA), by getting resistance from another bacteria (APUA, n.d.). It’s the bacteria itself, not the human or animal taking the medicine that becomes resistant to the antibiotics and when an antibiotic attacks a bacterial infection, there is a risk that some antibiotic resistant bacteria will survive the treatment, grow, and multiply, free from competition from other bacteria for resources. Therefore resistance increases with the quantity of antibiotics used as the amounts of antibiotics to which bacteria is exposed increases the amount of drug-resistant bacteria (CDC, n.d.).

In a globalized era the threat of antibiotic resistance is heightened as it’s easier for drug resistant bacteria to be transmitted between people (APUA, n.d.). For example, if a person from the UK has a bacterial infection that is treated with antibiotics, some of the bacteria will be susceptible to antibiotics, but others may be drug-resistant. If this person travels overseas, they could carry this resistant bacteria with them and spread this bacteria to other people through ways such as coughing. Another person who comes into contact with this antibiotic resistant bacteria may develop a drug-resistant infection. Martin et al. (2015, p. 2409) have shown that around 80% of USA antibiotic sales are for use in animal agriculture. Antibiotic resistant bacteria in animals can be passed onto humans in ways including when these antibiotics enter the environment as waste (Ibid.). Antibiotic resistance is therefore a multifaceted problem that requires a ‘One Health’ approach involving multiples sectors working together (WHO, 2017a).

In recent years there has been a dramatic global rise in antibiotic usage. Research shows that between 2000 and 2005 global antibiotic consumption increased by 65%, and by 78% in Low and Middle Income Countries (LMICs) (Klein et al., 2018), where higher levels of drug-resistance has also been found (Alvarez-Uria et al, 2016, p. 61). The researchers however recognizes that average antibiotic consumption rate in LMICs are still far below HICs and relates this increase in antibiotic consumption to the fact that LMICs represent larger populations and suffer a higher burden of infectious diseases (Klein et al., 2018). As noted by

the ReAct group (2018), this increase is ‘partly due to a previous lack of affordable access to essential lifesaving antibiotics and […] underuse in these countries.’ A challenge therefore lies in simultaneously increasing access to antibiotics where needed and reducing consumption of antibiotics in settings where they are overused.

There is also a link between inequality and AMR in Europe as research conducted by the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) found that an increase in income inequality was correlated with increased rates of AMR and infectious diseases (Kirby and Herbert, 2013, p.1), meaning those of lower economic status in Europe will be more affected by increasing AMR. Social determinants such as income and living conditions have been shown to influence social and health inequalities, which increase vulnerability to infectious disease (ECDC, 2013, p.5).

In the UK and nations where antibiotics are only available by prescription, factors feeding resistance are the overprescribing of antibiotics, poor knowledge and attitude towards drugs, patients demanding antibiotics unnecessarily (for example for viral infections, against which antibiotics are ineffective), sharing antibiotics and failing to complete a course of antibiotics as advised. In countries where antibiotics are available without prescription, including many LMICs (Chang et al., 2017), a key issue is a lack of surveillance and regulation around antibiotics, and access to qualified healthcare professionals. In countries where pharmaceutical industries are less regulated, counterfeit antibiotics are often available and may be sold by unlicensed providers (Morgan et al., 2011), and factors feeding resistance include poor infection control measures and self- medicating with antibiotics without advice from a qualified healthcare provider.

In 2015 the WHO (2015b, p.2) conducted a global public awareness survey across 12 WHO member states to assess knowledge and understanding of antibiotic resistance. The survey revealed that globally knowledge levels are mixed, with many showing awareness of AMR but not fully understanding the issue. A prevalent misconception identified is that it’s the person taking antibiotics that becomes resistant which led to many respondents stating that antibiotic resistance is only a problem for people taking antibiotics regularly (Ibid), presenting a challenge in AMR communications as antibiotic resistance may be considered as ‘someone else’s problem’. 43% of respondents believed it was fine to request the same antibiotics from a healthcare professional if antibiotics helped when they previously displayed similar symptoms, and a third of respondents thought that it was fine to not complete a full course of antibiotics, with 64% believing that viruses are treatable with antibiotics (Ibid., p. 1 and 2). More than half of respondents did not understand their role in efforts to address antibiotic resistance, believing there was not much they could do (Ibid., p.2).

Antibiotic resistance is a public health emergency and already we are witnessing a marked rise in drug-resistant bacteria and ‘superbugs’ such as MRSA. It’s estimated that globally 700,000 deaths each year are caused by drug resistant infections, including HIV, Malaria and Tuberculosis (TB) (The Review on Antimicrobial Resistance, n.d.), to whom 490,000 people developed multi drug resistance in 2016 (WHO, 2018c). Patients with antibiotic resistant infections are harder and more expensive to treat, with an increased risk of the infection spreading. The WHO have estimated that the economic cost of AMR could be devastating and lost global production by 2050 could be up to US$ 100 trillion (WHO, 2017b). A continued

increase in drug-resistant infections would also impact lifestyle as measures may be taken to reduce the prevalence of minor injuries if contracting a minor infection could have serious consequences.

2.2 Global Response to Rising Antibiotic Resistance

The WHO (2018a) recognizes ‘without behaviour change, antibiotic resistance will remain a major threat ’and over the past 40 years only two new classes of antibiotic drugs have been developed as many pharmaceuticals companies have stopped researching new antibiotics as it’s not economically lucrative. (Antibiotic Research UK, n.d.) New antibiotics that are being developed (WHO, 2018a) will also have little impact if overuse continues and global efforts have therefore focused heavily on preventing the rise and spread of drug-resistant bacteria. In 2015 the WHO (2015a) endorsed a Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance (GAPAR) to centralize a response to the crisis with five strategic objectives to address AMR, one of which is ‘improve awareness and understanding of antimicrobial resistance through effective communication, education and training.’ Whilst many HICs have implemented national strategies to combat AMR, it’s still not on the agenda for many LMICs (Gelband and Delahoy, 2014, p.4). When the WHO member states endorsed the 2015 GAPAR, they committed to the target of ‘developing a multisectoral national action plan within two years’ (WHO, 2015a), yet by May 2017 only 60.4% of the majority of the WHO member states had developed a national action plan on AMR (WHO, 2018d, pp. 5 and 7).

With specific regards to objective one of the GAPAR, which aims to increase awareness and understanding of AMR, action is outlined to be taken at national and secretariat level. The actions outlined for member states include increasing ‘national awareness of antimicrobial resistance through public communication programmes that target the different audiences in human health’ and providing the public media with core information to reinforce key messages (WHO, 2015a).

2.3 Challenges of Communicating Antibiotic Resistance

Although the WHO (2017c p.5) recognize that increased knowledge of antibiotic resistance alone does not lead to behaviour change, effective communications campaigns can help the public understand the issue and encourage behaviour change around antibiotic usage,4 and

campaigns can encourage the public to support policy change which could influence aid budget spending (Scott, 2014, p.173). Kodish (2018, p.755) argues that crucial to effective communications campaigns is the narrative conveyed as narratives can move populations to act in a particular way. (Ibid, p. 754). Kodish argues the current master narrative around antibiotics is tied to their status as ‘omnipotent medications’, a narrative that is deeply ingrained and difficult to change (Ibid., p.755), and that key to addressing AMR is the development of a new narrative that challenges the notion of antibiotics as all-powerful medications (Ibid.).

4A 2010 comprehensive study examining the outcomes of 22 HIC campaigns around antibiotics resistance found

that the campaigns did appear to reduce antibiotic usage and encourage more careful use of antibiotics in countries with high levels of prescribing (Huttner et al. cited in Kodish, 2018, p.748).

Research conducted by the Wellcome Trust (2015) with members of the UK public highlighted several issues to be considered when communicating the issue of AMR to the public. The survey unveiled that participants found it hard to relate to information highlighting the global scope of the issue, and it was only when the impact of AMR was described at a personal level that they began to take note (Ibid., p.30). The survey highlighted mixed understandings as to how antibiotics work, with many participants stating they would not complete a course of antibiotics to minimize the impact on the body (Ibid., p.13) and that they themselves are able to recognize when antibiotics are needed, and have considered this before visiting the doctor, shaping their expectations for the appointment (Ibid., p.6). This was linked to patients taking actions to ensure they received antibiotics, including exaggerating symptoms.

The survey also found it was only when the effects of antibiotic resistance on specific superbugs such as MRSA were explained that people began to listen (Ibid., p.27), however sensationalist language has lost its impact (Ibid, p.33) highlighting a need for simple language focused on ‘illness and implications’ (Ibid., p.36). Many participants were suspicious of AMR, believing it could be a way for the government to save money (Ibid., p.17), yet had faith that scientists will fix the problem (Ibid., p. 18) and felt that newspaper headlines highlighting the impact of AMR were simply ‘scaremongering’. Public health communications on AMR must therefore seek to mitigate any ‘scaremongering’ doubts whilst simultaneously communicating the consequences of antibiotic misuse. This is crucial, as highlighted by Pinder et al. (2015, p. 48) who states that ‘without a clearer understanding of the consequences of unnecessary antibiotic consumption it’s unlikely that a new social norm for antibiotics […] can be established.’

Health promotion researchers Sixsmith et al. (2014, p.9) note the importance of recognizing potential adverse consequences of health communication campaigns. They refer specifically to a case study of campaigns in England between 1997 and 2005 on the rational use of antibiotics, which resulted in increased hospital admissions for Pneumonia due to decreased use of antibiotics. Campaigns can have damaging effects as how they communicate the issue to the audience could lead to unintended reactions. Some of these evidence-based unintended consequences of health campaigns can be found below:

Figure 1: Table showing the potential unintended effects of health communication campaigns (Sixsmith et al., 2014, p.9)

Sixsmith et al. (Ibid., p.10) state that to avoid these unintended effects campaigns should be grounded in health and behaviour change theory, with attention paid to audience, channel and message.

Antibiotic resistance is a multi-sectoral public health issue fuelled by human overuse of antibiotics and requiring mass behaviour change to be addressed. It’s a global issue that will have the most dire effects on the world’s poorest, although HICs currently consume the most antibiotics. The issue must therefore be addressed in the Global North to prevent catastrophic effects in the Global South, and the next chapter will outline the selection of a UK case study for this study.

3. UK Case Study Selection

The UK has played a key role in tackling antibiotic resistance globally (Department of Health [DOH], 2013, p.13)5, and has implemented a national strategy to address AMR, including a

nationwide mass media campaign. The UK is a high user of antibiotics in comparison to other European nations with a third of the British population taking antibiotics at least once per year (HM Government, 2019, p.6). AMR is already having significant effects in the UK, with PHE (2018a) stating that drug resistant blood stream infections, including Septicaemia, rose by 35% in England between 2013 and 2017. There has been an increase in drug-resistant TB in the UK (Ibid., p.4) and PHE (2018d, p.3) have noted a correlation between TB and social inequality with the UK’s most socially deprived having higher rates of TB infection. STI rates

5The UK has played a key role in tackling antibiotic resistance globally, helping to ‘shape thinking on the issue

and helping develop an international framework of action’(Department of Health, 2013, p.13). in 2014 the UK also launched an independent review board for global action against AMR. The final report was released in 2016 and contained 10 key recommendations for tackling AMR across the globe.

are also more prevalent in economically deprived urban zones, particularly Gonorrhoea6 and

HIV, which have both shown drug resistance (WHO, 2018b), meaning AMR could significantly impact Britain’s most vulnerable.

The UK developed a Five Year Antimicrobial Resistance Strategy 2013 to 2018 outlining actions to address AMR which outlined three key aims, one of which was ‘improve the knowledge and understanding of AMR’ (DOH, 2013, p.7). A key stated action to meeting this objective is ‘improve professional education, training, and public engagement to improve clinical practice and promote wider understanding of the need for more sustainable use of antibiotics’ (Ibid., p.15) and the report recognizes the role of the public, stating, ‘everyone has a responsibility and a role to play’ (Ibid., p.7). Since the strategy launched, several initiatives to engage the public in AMR have been instigated7. In October 2017, PHE launched

one of these initiatives, the KAW campaign, in support of ‘the government’s ambition to halve inappropriate prescribing of antibiotics in the UK by 2020 by reducing public pressure on GPs to prescribe’ (PHE, 2017a, p.25). The 2017 campaign ran for eight weeks (PHE, n.d, p.11) and was relaunched in October 2018.

3.1 ‘Keep Antibiotics Working’ Campaign

The 2018 KAW campaign was a nationwide multi-channel campaign which ran from 23rd October to 16th December 2018 (PHE, 201e). The campaign featured advertising TV, radio social media, and PR channels, and resources included a television advert, printed leaflets, posters to be displayed in healthcare settings, social media campaign, and outdoor posters (Gwynn, 2017), centring on the messaging that ‘taking antibiotics when you don’t need them puts your family at risk’ (PHE, 2018b). Prior to its 2017 launch the campaign was piloted in the North-West of England, and PHE (2017b, p. 25) state the campaign had a demonstrated impact during its pilot phase, with less people reporting that they would request antibiotics from their GP following the campaign. Several researchers however have noted that public awareness of antibiotic resistance in the year following the launch remained low (Price et al., 2018: McParland et al., 2018: Mason et el., 2018). Two other initiatives have been launched in the UK to engage the public in antibiotic resistance, an ‘Antibiotic Guardian’ pledge scheme and a health education programme for children (Barber and Swaden-Lewis, 2017, p.24), however The KAW campaign had a wider reach than other initiatives.

PHE (2018b) state that public knowledge of antibiotic resistance is low, and although legally antibiotics are only available by prescription from a healthcare professional in the UK, a key issue in inappropriate prescribing is patients demanding antibiotics, even when they are not effective for an illness. (Ibid.) The KAW campaign focused on reducing patient expectation and demand for antibiotics, following healthcare provider advice, and increasing understanding of the fact that antibiotics cannot treat viruses (Ibid.). The campaign’s three key aims (Ibid.) were:

6Drug resistance in ‘Super Gonorrhoea’ was acquired in the UK in early 2019. Super Gonorrhoea refers to strains

of Gonorrhoea that are resistant to the standard drug treatment. There is growing concern that these strains may also become resistant to the alternative drug treatment and be significantly harder to treat.

7 Often initiatives and activities are promoted around European Antibiotic Awareness Day (18th November) and

1) Alert and inform the public to the issue of AMR in a way that they understand in a manner which they understand and increase recognition of personal risk of inappropriate usage.

2) Reduce public demand for antibiotics by increasing understanding amongst patients about why they might not be given antibiotics.

3) Support healthcare providers change by boosting support for alternatives to prescription.

PHE state the messaging for the campaign focuses on increasing public understanding that ‘taking antibiotics when you don’t need them means they are less likely to work for you in the future and to trust their doctors’ advice regarding the best appropriate treatment’ (Ibid.). The campaign was aimed at all adults but had a specific focus on groups with the greatest likelihood of using antibiotics, ‘women aged 20-45 who tend to have primary responsibility for family health […] [and] older men and women aged 50+’ (Ibid.).

The KAW campaign cost £2million and the TV advertisement was created by advertising agency M&C Saatchi (Gwynn, 2017). Mitchell (cited in Gwynn, 2017), PHE’s Marketing Director, stated of the TV advert:

‘changing behaviour meant appealing to them [people] on an individual level […] Is there more intelligent coverage about it [antibiotic resistance]? Yes, absolutely. But is that landing with Mum on a Friday afternoon with a screaming child – not necessarily. We’ve got to appeal to the individual before the collective.’

Mitchell (Ibid.) stated that initially PHE tested another TV advertisement which featured ‘a reassuring healthcare professional telling people about the dangers’ but this was ineffective as ‘if it was a GP [delivering the message], that was being interpreted as part of NHS cost-cutting exercises.’ Mitchell (cited in Burne-James, 2017) explains that in the campaign material it was therefore key to balance highlighting the threat of AMR with making a consumer-appropriate TV advertisement.

3.2 Case Study Selection

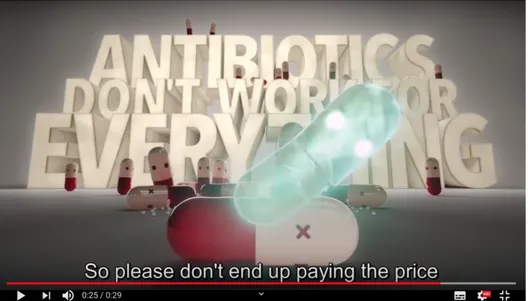

The case study for this thesis is the 2018 KAW campaign TV advertisement. Initially the study intended to analyse a selection of the 228 KAW 2018 campaign texts including two posters,

but it became apparent in early interviews that interviewees had highly different reactions to the content of the individual materials, even though they contained similar messaging. Interviewees found the TV advertisement problematic compared to the posters and the TV advertisement had a wider reach. Several participants had seen the 29 second long advertisement which aired on national television between 23rd October to 16th December

2018 (PHE, 2018c) but few had seen the posters. the TV advertisement’s accompanying song9

8 As of 8th January 2019

9 The lyrics of the TV advertisement’s song are: ‘Antibiotics - we're wonderful pills. But don't ever think we'll

cure all of your ills. So every time you feel a bit under the weather, don't always think that we can make you better. Take us for the wrong thing, that's dangerous to do, when you really need us we could stop working for you. So please don't end up paying the price, always take your doctor’s advice.’

was also played on the radio, and the advertisement was uploaded to the PHE YouTube channel10 and the channels of several regional NHS bodies. I decided to focus the study solely

on the TV advertisement, allowing for in-depth insight into the text.

Figure 2: Screenshot from the Keep Antibiotics Working campaign TV advertisement uploaded to YouTube (Public Health England, 2017b)

Due to the global interconnectedness of AMR, the actions taken by the UK will have a direct impact on tackling AMR globally. Mitchell (cited in Goodfellow, 2016) states the KAW campaign has ‘potential to create a blueprint for behaviour change campaigns in the developed world’ and an evaluation of public reaction to the framing of the advertisement can contribute to informing the development of future AMR communication activities. The next chapter will introduce the theories of behaviour change, health communication and health and social psychology that informed the analysis and research design.

4. Theoretical Framework

This chapter will define and discuss the theories of health and behaviour change communication (BCC) which have shaped this study and informed the research design. Through engaging with these approaches I situate this study within the field of Communication for Development (C4D) whilst also engaging with health psychology theories. Davis et al. (2017, p.8) note ‘new research approaches are called for that critically scrutinise the relations between public and science and the related AMR communications challenges which lie ahead.’ A multidisciplinary theoretical approach to this study was chosen to reflect with the wider need for multidisciplinary approaches to tackling AMR.

4.1 Health Communication

10 The TV advertisement can be found on PHEs YouTube channel at:

Health communication (HC) is a ‘branch’ of the broader field of Communication for Development (C4D). Over the years, definitions of HC have evolved, but at its core it’s concerned with ‘influencing, supporting, and empowering individuals, communities, health care professionals, policymakers, or special groups to adopt and sustain a behaviour or a social, organizational, and policy change that will ultimately improve individual, community, and public health outcomes’ (Schiavo, 2013, p.3). The KAW television advertisement aims to inform the audience about AMR, and reduce public expectation for antibiotics. By changing antibiotic seeking behaviours this reduces overall demand for the drugs, improving public health outcomes.

Within C4D work there is an overarching tension between diffusion and participatory models of work. Participatory models involve bottom up initiatives centred on participation and dialogue, whereas the diffusion model centres on the idea that social and development problems stem from a lack of information (Waisbord, 2001: Tufte, 2017, p.22) and the solution is the linear transmission of information via methods including mass media campaigns (Waisbord, 2001, p.2). Key differences between the two approaches can be seen below:

Figure 3: Table showing the key distinctions between diffusion and participatory Development Communication approaches (Rhodin, 2018, p.22)

4.2 Mass Media Campaigns

The KAW campaign TV advertisement is part of a mass media campaign which takes a diffusion approach to delivering information. Both the diffusion approach and mass media campaigns have faced much criticism from C4D researchers. Researchers argue that even perfectly designed mass HC campaigns, whilst they may increase public awareness of an issue, cannot significantly impact health behaviours as they target homogenous population groups,

but behaviours are entwined with different cultural beliefs, knowledge and attitudes (Snehendu et al., 2001, p. 337). Obregon and Waisbord (2012, p.19) highlight how mass communication campaigns cannot even be considered ‘communication’ and is rather mass information dissemination, calling for an approach to HC that recognize the importance of social context in challenging health issues. The diffusion model has also received criticism for ‘blaming the victim’ and failing to recognize social contexts which facilitate unhealthy behaviours (Waisbord, 2001, p. 11). This is pertinent to the KAW campaign which links increasing antibiotic resistance to the consumer in the key campaign message ‘taking antibiotics when you don’t need them puts you and your family at risk’ (PHE, 2018b).

As noted by Pirio (cited in Obregon and Waisbord, 2012, p.427), mass media can have huge influence noting how in the case of HIV/Aids, globally the majority of people’s knowledge comes from mass media channels. Mass media campaigns can incite behaviour change in a population by raising knowledge and awareness of an issue, shaping ideas, raising awareness of the benefits of behavioural changes, demonstrating how changes can be made, and emphasising new social practices as mass media can influence how an audience perceives social norms, which ‘supports people’s efforts to change behavior’ (AIDSCAP Behaviour Change Communication Unit, nd., p. 5-7).

4.3 Behaviour Change Communication

Behaviour Change Communication (BCC) is the branch of HC specifically concerned with addressing ‘gaps in knowledge, attitudes and behaviours amongst a target audience’ (Singhal cited in Dagron and Tufte, 2006, p.722). Whilst several models of BCC exist, they often have mixed outcomes as health behaviour change is complex to achieve (Ibid). Although definitions are used interchangeably, BCC approaches generally adopt a diffusion approach and have been criticised for suggesting that individuals are in control of their behaviours and make health decisions rationally (Ibid.), not recognising the social, cultural and political contexts affecting health. Within C4D a distinction has therefore been made between BCC and Social and Behaviour change Communication (SBCC) initiatives11 that call for participatory

approaches incorporating a focus on social determinants of health (Wilkins et al, 2014, p. 289).

BCC programmes are often comprised of a variety of interventions, and three overarching categories under which they generally fall are outlined by the Measure Evaluation Project (MEP, n.d.), a USAID funded project with SBCC expertise, as:

• Mass media (radio, television, billboards, print material, the internet) • Interpersonal communication

• Community mobilization

11Although a distinction has been made between BCC and SBCC initiatives, and SBCC is considered a

breakthrough in health communication as it lays more emphasis on social context, the terminology is often used interchangeably. Further information on this can be found at:

<https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5bad0421ed915d25a0587a15/181_BCC_on_health_related_i ssues.pdf> and

BCC and SBCC activities seek different results (Obregon and Waisbord, 2012, p.97) and mass media campaigns are able to reach a broad audience and are often quicker to implement, crucial in the case of AMR as there is an urgency to addressing it. Furthermore, mass media campaigns are able to communicate a highly focused and consistent message to a wide audience and targeted segments of a population over a specific period of time, and are often more cost effective than participatory focused HC interventions (AIDSCAP Behaviour Change Communication Unit, nd: Wakefield et al., 2014).

Increased knowledge in a population following campaign exposure is dependent on the persuasiveness of the message, message exposure and evaluation of the activity (Tull, 2017, p.6). BCC initiatives can therefore have an effect on individuals, but also on social systems as a whole by influencing social norms around a health issue (UNICEF, n.d, p30).The use of mass media campaigns is often only one component of a wider BCC strategy and it’s widely recognized that alone they will have limited influence on behaviour change, but are most effective when they incite dialogue around an issue and are combined with interpersonal communication (Ibid.).

Evaluation is a crucial part of BCC initiatives as it allows for assessment of the impact and outcomes of the initiative on the target group against specific objectives, measured by core indicators which include change in intention, knowledge and attitude (MEP, n.d.). UNICEF (n.d) define evaluation in terms of C4D programmes, including BCC initiatives, as a systematic method of evidence collection to assess what changes occurred in the target population and whether the intended results were achieved, with a focus on whether changes can be attributed to the activity being evaluated. Short-term and medium- outcomes can be evaluated with short term outcomes noted as ‘the changes in awareness, knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, self- and collective- efficacy, skills, intentions and motivations’ and medium- term as ‘changes in the behaviours, practices, decision-making processes, power relations, policies and social norms’ (Ibid., p47), which generally taking longer to manifest.

4.4 Criticisms of Behaviour Change Communications

Behaviour change approaches to HC have faced criticism, and their effectiveness remains unclear with some researchers debating whether health promotion initiatives should completely abandon the notion of behaviour (Laverack, 2017: Den Broucke, 2014). Critics argue that targeting a specific risky health behaviour has minimal impact on the determinants that contribute to poor health (Ibid.), particularly for at-risk groups. This can reversely heighten health inequalities by not paying attention to the factors leading to poor health and behavioural risks, and can stigmatize vulnerable groups12 (Laverack, 2017, p.2 and 3).

Laverack (Ibid.) notes that BCC initiatives often over-rely on paternalistic didactic communication approaches and have ‘inadequate audience segmentation, [and] inappropriate message content’, stating that a focus on empowering the audience to make healthy choices would be more effective with attention paid to audience perception of the

12 As noted by Guttman (2001, p.118) health communications often play on ideas of morality and ‘health

recommendations linked to […] responsible behaviours may insinuate moral indignation if not adopted’, which could heightened the stigmatization of those not following the recommended actions of a health campaign.

importance of a health issue. Critics highlight that BCC initiatives frequently equate behaviour change with increased knowledge of a health issue assuming the audience lack information on a health issue, yet often audiences do have knowledge, therefore initiatives should instead centre on barriers to behaviour change (Barnes, 2015, p.432). Barnes (Ibid.) also notes a criticism of BCC as often grounded in gendered assumptions of women as caregivers, which can inadvertently place blame and responsibility for risky health behaviours on women.

4.5 Health Belief Model

The Health Belief Model (HBM) is a widely used theory in informing behaviour change interventions. Several theoretical models for understanding health communication exist, but most relevant to this study is the Health Belief Model (HBM) which focuses on health motivation (UNICEF/Ohio University C4D (2011, p.1) and is grounded in the notion that individual actions are controlled by personal beliefs, attitudes and feelings (Servaes, 2008, p.258). Other theories of behaviour change overlap with the HBM, however vary in focus. For example, the Stages Of Change model centres on behaviour change as a process and is circular and focused on long term change, therefore not suitable for this study as the KAW campaign had a defined time period and set of aims.

The HBM suggests that BCC initiatives will be most effective if they successfully engage with a set of variables focused on audience perceived susceptibility to the health threat, severity of a health issue, and perceived benefits of, and ability to, change behaviours (UNICEF/Ohio University C4D, 2011: Champion and Skinner, 2008). Under the HBM, mass media campaigns can act as a cue to action (Glanz et al, 2002, p. 52), highlighting the importance of a health issue to the audience and stimulating behaviour change. Critics of the HBM suggest that the model needs to include additional variables such as consideration of future consequences of behaviour, self-identity, concern for how others will perceive their behaviour and perceived importance of a health behaviour (Orji et al., 2012). As noted by Avis (2016, p.2), these variables are important as ‘relationships with partners, families and the community […] can substantially determine how we behave.’ In an age of social media, health behaviours such as smoking are also visible through our online profiles thus concern for how others view behaviours could increasingly influence attitudes towards health issues.

4.6 The Use of Fear in Health Communication

In HC fear is often used as a tool to promote behaviour change as appealing to the audience’s anxieties can persuade the audience to follow a recommended health message (Witte cited in Simpson 2017, p.1). Managing fear is crucial to successful BCC campaigns as understanding the fears of the audience can ensure campaigns can achieve the desired outcome (Obregon and Waisbord, 2012, p. 274). Expert opinion on the effectiveness of campaigns that use fear inducing tactics is mixed, however many theorists agree that they can be highly effective if implemented correctly, but could backfire if implemented incorrectly (Sixsmith et al, 2014). According to Witte and Allen (2000, p. 594), ‘the more individuals believe they are susceptible to a serious threat, the more motivated they are to begin […] an evaluation of the efficacy of the recommended response. If the threat is perceived as irrelevant […] people simply ignore the fear appeal.’ However, if a threat is perceived to be serious, individuals develop fear, and this fear motivates the viewer to take action to mitigate their fear, if they believe they are

able to perform the recommended response. Leading theorists (Witte and Alan, ibid: Soames Job’s, 1988, p.163 and 601) acknowledge that the effectiveness of fear appeals depend on the levels of fear they induce in the viewer, arguing that the stronger the fear aroused, the more effective the appeal.

This chapter has outlines the theoretical framework that has shaped this study, and guided results analysis. The next chapter will describe the research design and methodology, showing how the research design supported the overall research intention, and was influenced by concepts discussed in the theoretical framework.

5. Research Design and Methodology

The research design and methodology of this study centred on incorporating questions to measure changes in participant’s knowledge of antibiotic resistance and motivation to change behaviours both prior to, and directly after, viewing the TV advertisement. The study took a post-structuralist approach with ‘the hypothesis of an ‘active audience’ that interprets, makes sense, and decodes […] texts’ (Raftpoulou, 2007, pg. 14). The primary research methodology was surveys supported by interviews with members of the KAW campaign’s focus audience groups to measure the short term outcomes of the campaign, and a lightweight textual analysis to analyse the framing of antibiotic resistance in the TV advertisement. Combining these methods allowed me to triangulate findings and further validate the study. The chosen methodologies were selected as tools to answer the sub research questions, which combined addressed the overall research question:

What role does the framing of antibiotic resistance in Public Health England’s 2018 TV advertisement, part of the ‘Keep Antibiotics Working’ campaign, play in increasing understanding of antibiotic resistance and encouraging behaviour change amongst the target audience?

5.1 Study Indicators

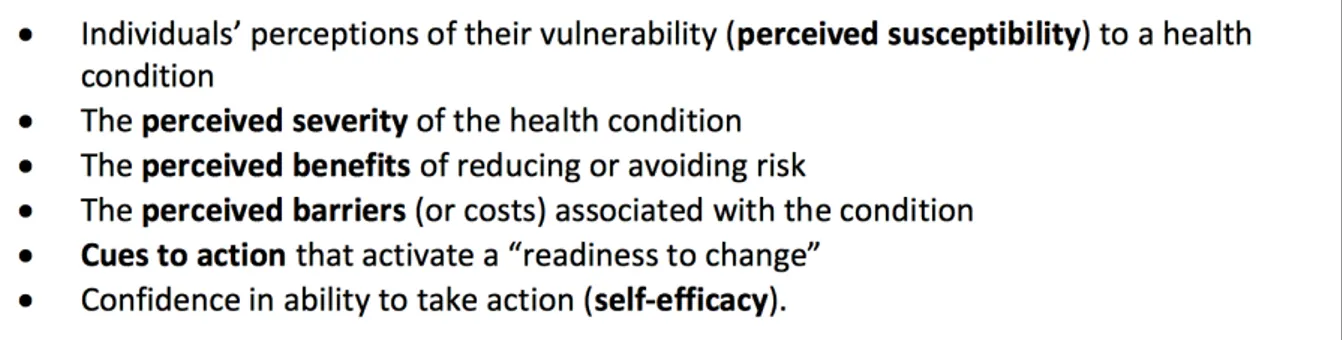

Indicators through which health communication is analysed under the HBM model can be seen in the table below:

Figure 4: Table showing indicators which form the framework through which health communication is analysed under the HBM model (UNICEF/Ohio University C4D, 2011, p.1)

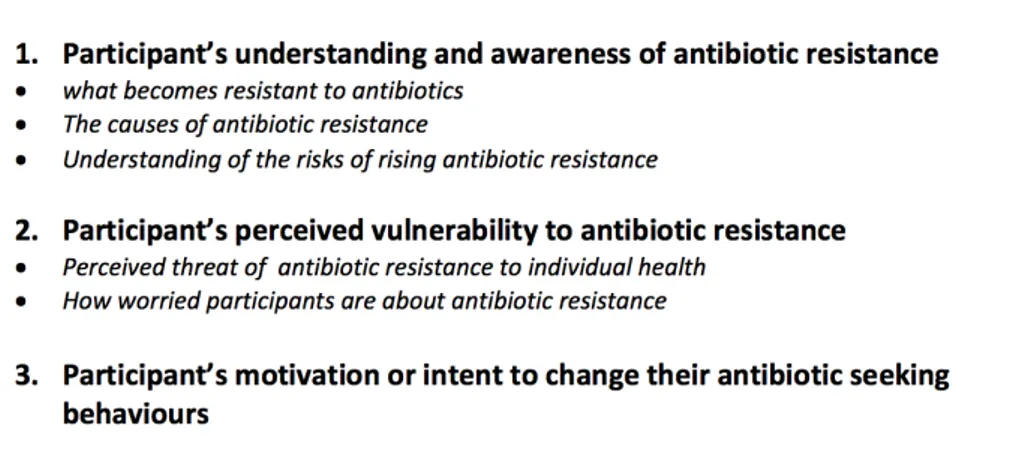

These informed the development of the specific indicators against which questions were formulated, and data analysed. Indicators of knowledge and awareness of antibiotic resistance were developed to ensure all changes post seeing the TV advertisement were measurable and these indicators centred around the aims of the KAW campaign to allow an evaluation of the results against these aims. The specific study indicators developed were:

Figure 5: Indicators developed for the study

An issue in mass media campaign evaluation is the lack of a control group that has not been exposed to the campaign, and would serve to establish that behaviour change occurred as a direct result of the campaign (MEP, n.d.). The MEP (Ibid.) outline conditions for inferring causal attribution which influenced research design as:

1. Observation of a change or difference in the population of interest

2. Correlation between exposure to the intervention and the intended outcome 3. Evidence that exposure to the intervention occurred before change in the outcome 4. Control or removal of confounding factors (or spurious effects).

As government statistics confirming the impact of the 2018 KAW campaign on antibiotic seeking behaviours were unavailable, questions were formulated around the above mentioned indicators to assess whether a change in understanding of antibiotic resistance or antibiotic seeking behaviours led to higher levels of motivation to change antibiotic seeking behaviours amongst participants directly after seeing the TV advertisement. The study recognizes that concrete changes in behaviour may not yet be apparent so focuses on whether the participant had intent to change antibiotic seeking behaviours.

5.2 Sampling

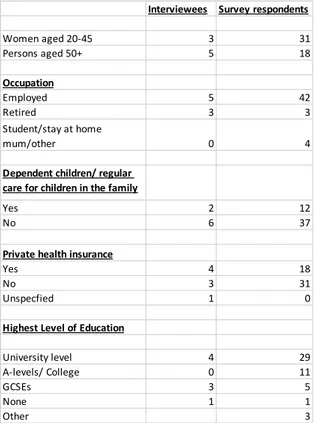

Although the KAW campaign was aimed at all adults in England, it was designed to be most effective in achieving its aims amongst specified focus groups. These groups were females aged 20-45 and men and women aged 50+, groups most likely to consume antibiotics as women aged 20-45 often primarily lead on family health, and those aged 50+ have higher levels of contact with the GP, specifically those with recurrent conditions (PHE, 2018b). The study sample incorporates women aged 20-45 and anyone aged 50+, regardless of whether they had children and family responsibilities, or had regular interaction with the GP, to allow insight into how the advertisement was received by different members of these broad focus

groups. In total eight interviews were conducted and the survey had 49 respondents. Due to the relatively small sample size the study is not considered representative of the views of all members of the campaign’s target groups, but instead is indicative of members of the target groups reaction to the TV advertisement, and supported by the textual analysis.

A survey was created on Google Forms and shared online over a nine day time period via Facebook at which point it had 49 responses, and sufficient data for patterns to identified amongst a diverse sample of respondents. The survey specified in the description that it was aimed at these focus groups, and all respondents stated which of these groups they fall under and where they live in England. Personal contacts, whom I was aware represented different segments of these focus groups, such as those with dependent children and those who form part of the aged 55+ audience were contacted and asked to share the survey via their networks to allow for a wider range of respondent outside of my personal network. This was successful in diversifying responses as the survey was shared amongst a group of young mothers and older persons. Eight interviewees who represented a diversity of backgrounds and situations were identified in my personal networks, contacted about participating in the study and selected according to availability and suitability.

A criticism of mass media campaigns is that they don’t pay enough attention to the social context of the audience, so study participants were incorporated from a diverse range of geographical and social contexts within the parameters of the target groups, to understand if the campaign material was interpreted differently according to factors such as familial status, employment status, location, health insurance status and education level. These parameters were chosen as they have potential to influence antibiotic consuming behaviours, and exposure to information on AMR. For example, a person with children may have more interaction with a GP than a person without children. This also allowed me to avoid data bias from only including participants from similar backgrounds, however a limitation of this study is that study participants were sourced via my personal networks which could have a bearing on the data. For example, the majority of study respondents were employed and educated to degree level therefore a limitation of the study is that it may not be fully indicative of the views of those of lower economic status who may interpret the campaign differently.

Participants who had specialist knowledge of antibiotic resistance gained through employment were not included to ensure the data was not biased by professional knowledge of AMR. Eight respondents stated that either they or close friends or relatives had specialist knowledge of antibiotic resistance. As each of these respondents listed their occupation and it was not related to antibiotic resistance, it was decided that this would not bias the data and they were included in the study. 38% of participants stated they had private health insurance. Given that the survey was focused on the TV advertisement, not the posters which were displayed in public healthcare settings, this was not considered a problem. Figures showing examples of the diversity of respondents can be seen below.

Figure 6: Table showing diversity of study participants

Figure 7: Chart showing the location of survey respondents

5.3 Textual Analysis

The textual analysis was conducted to systematically identify how antibiotic resistance was framed in the advertisement, addressing the sub research question:

• How are the causes, consequences of, and solutions to antibiotic resistance being communicated to the public in the TV advertisement to change antibiotic seeking behaviours?

Interviewees Survey respondents

Women aged 20-45 3 31 Persons aged 50+ 5 18 Occupation Employed 5 42 Retired 3 3 Student/stay at home mum/other 0 4

Dependent children/ regular care for children in the family

Yes 2 12

No 6 37

Private health insurance

Yes 4 18

No 3 31

Unspecfied 1 0

Highest Level of Education

University level 4 29 A-levels/ College 0 11 GCSEs 3 5 None 1 1 Other 3 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 Be nf le et Bi sh op A uc kl an d Bo re ha m w oo d Br is to l Bu ck fa st le ig h De rb y Do rk in g Du ns ta bl e Ea st bo ur ne Ev es ha m Ex et er Ha sl em er e He an or Le ic es te r Lo nd on Ne w ca st le Ot he r Ox fo rd Re ad in g St ev en ag e Sc un th or pe Ta un to n To rq ua y We st S us se x Wo rc es te r Ye ov il

The textual analysis of the TV advertisement focused on three elements: 1) Song lyric

2) Visual storyline

3) Signs and symbols in the text.

The focus was to identify these elements, rather than analyse their significance, as this study was not concerned with campaigner intent, but the effect that the texts are having on the audience. This is why a lightweight textual analysis focused on identifying the above elements of the campaign was considered a more suitable research method than discourse or narrative analysis. The textual analysis combined several methods to deconstruct the advertisement’s content, examine meaning and structure, and identify what, and how meaning is being produced. This is key as how campaign material is ‘read’ can affect whether viewers are motivated to change behaviours. The textual analysis drew on a range of theories including semiotic and visual to explore how AMR had been communicated to the audience. Textual analysis has been criticized for ‘neglecting the importance of the […] reader in the construction of meaning’ (Lockyer, 2012, p.865) thus was combined with interviewing and surveying to compare how members of the target audience themselves interpreted the campaign material.

The textual analysis was conducted in stages and first involved watching the advertisement three times, with each viewing focusing on one of the above listed elements noting how antibiotic resistance and the campaign’s key message were communicated via each element. The second stage involved viewing the advertisement focusing on how the lyrics, storyline and symbols of the advertisement interact in communicating the issue of antibiotic resistance. The final stage involved viewing the advertisement three more times, focusing on how 1) the consequences 2) the causes and 3) the solutions to antibiotic resistance were communicated. The findings were collated and analysed via identifying key semiotic, visual and narrative elements of the text to give an overall understanding of how antibiotic resistance was framed in the advertisement.

5.4 Survey Research

Surveys were conducted to evaluate the impact of the advertisement on the target audiences, addressing the sub research questions:

• What effect does the TV advertisement have on members of the target audience’s attitudes towards, and understanding of antibiotic resistance? • Does the TV advertisement challenge or reinforce misunderstandings

about antibiotic resistance?

Surveying was chosen as the primary research method as it allowed me to reach a larger sample size, and to formulate questions in a way that incorporated key indicators allowing for focused qualitative and quantitative responses. The survey contained a mix of open and closed ended questions and an explanation of the survey, including consent.

Core to this study was question sequencing to ensure the core indicators and changes in attitude and knowledge could be measured before and after seeing the TV advertisement. The TV advertisement was placed in the middle of the survey and a message was displayed asking the participant to watch the video before answering the following questions. To increase data validity, and assess this change some questions were repeated post seeing the TV advertisement. This allowed for the effects of the advertisement on the respondents to be attributed to the text and for information to be gathered on respondent understanding of antibiotic resistance both prior to and post seeing the advertisement, and analyse if after watching the advertisement any misunderstandings of antibiotic resistance were challenged, or reinforced. The survey can be found in the appendices. A key strength of the survey was that it was completed anonymously which assisted in getting more honest answers, however a weakness is also noted as the question wording which may have oversimplified the issue discussed.

5.5 Survey Data Categorization

When analysing the survey data, attention was paid to the responses individually and collectively. Closed ended question responses were analysed quantitatively and open ended responses were categorized with similar responses grouped together. The development of categories allowed for trends in the data, based on the study’s key indicators, to be identified, and a selection of categorized data can be found in the appendices. The process of category development was an iterative process and involved identifying overt themes in the data with a focus on surface level responses, rather than identifying underlying meaning in the responses. Although categorizing data can be highly subjective, focusing on surface level responses meant less room for researcher views to bias the data. Many of the questions were formulated to assess whether the respondent demonstrated correct knowledge of an issue such as what becomes resistant to antibiotics, and what is the aim of the advertisement and responses were categorized according to their level of correctness. This allowed me to concretely ‘measure’ the data against the key indicators, and further validated the data set as categorization was not subjective but based on factual correctness of the responses.

5.6 Semi-structured Interviews

Interviewing was selected as a research method as it allowed in-depth insight from interviewees and provided a secondary data set to support survey findings. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with a mix of open-ended and closed questions to ensure specific topics were covered in the interviews, but also that the interviews were able to flow in directions not anticipated beforehand (Cook, 2008: Brinkmann, 2008, p.470). Interviews were conducted either by phone, face to face, or via Skype, and were recorded and transcribed. Questions were altered throughout the process of interviewing to account for issues not previously anticipated and a selection of transcribed interviews can be found in the appendices. The core interview questions were formulated in relation to the study’s key indicators, but the semi-structured nature allowed me to seek participant clarification around points of interest that arose.

5.7 Thematic Analysis of Interview Transcripts

A thematic analysis was conducted on the interview transcripts to identify patterns in the individual and collective transcripts. Thematic analysis is an approach to analysing qualitative data centred on coding data according to themes identified in texts and analysing the results through identifying ‘commonalties, relationships, overarching patterns, theoretical constructs, or explanatory principles’ (Lapadat, 2012, p.926). Although critics argue that through the process of deconstructing texts to identify themes overall narrative contextuality can be fractured, given that the transcripts consisted of responses to set questions, it was useful to identifying overarching themes amongst the interview transcripts.

Theme identification was guided by the study’s key indicators, and involved several readings of the text to identify themes present in the responses, and then considering the overall data set to identify overarching common themes. Triangulation of the interview allowed me to avoid data bias that may have arisen during the process, for example from my role as a researcher with pre-set ideas about what themes may arise. The transcripts were colour- coded according to these themes and a selection of colour coded transcripts can be found in the appendices, coded in accordance with the themes below:

Categories

Understanding of what becomes resistant to antibiotics Understanding of the causes of antibiotic resistance Risks of antibiotic resistance/perceived level of the threat Levels of fear of antibiotic resistance

identifying as a responsible antibiotic user

Knowledge of antibiotic effectiveness against colds and flu Criticisms of the TV advertisement

5.8 Study Limitations

As a researcher I recognize I have professional knowledge of AMR that may have influenced data analysis, particularly in the textual analysis, as audience interpretation of a text varies greatly between persons (Lockyer, 2012), and when categorizing data. I conducted the textual analysis first to ensure the analysis was not biased by insight from participants. When formulating questions I was conscious of ensuring that my own views on the advertisement were not reflected in the wording and the process of data categorization was iterative, to ensure that I was not simply ‘fitting’ data into pre-set categories. Data was also triangulated to further validate category creation.

Initially I had not planned to conduct survey research, and planned on conducting 25 interviews however it became clear during initial interviews that 25 participants would not reflect the diversity of the target audience groups and it was challenging to get interviewee to focus their answers. it was more pertinent to the study to combine fewer interviews with surveys, allowing me to engage with a larger sample of respondent. Although a relatively