Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour

amongst Millennials in Online Communities

The role of information and goal-frames on Instagram

Karin Drozd

Vanessa Trager

Main field of study – Leadership and Organisation

Degree of Master of Arts (60 credits) with a Major in Leadership and Organisation Master Thesis with a focus on Leadership and Organisation for Sustainability, 15 credits Spring 2019

Abstract

With the aim to reduce the effects of anthropocentric climate change and achieve a more sustainable future, promotion of sustainable individual behaviour is just as essential as driving political and economic change. As social media are experiencing growth in popularity, online communities in which influencers act as opinion leaders are a promising tool to influence behaviour. The objective of this paper was to examine the role of individuals’ pre-existing value structures and the effectiveness of encouraging pro-environmental behaviour amongst the millennial generation on Instagram. The study design is based on the extended version of goal-frame theory, The Integrated Framework for Encouraging Pro-environmental Behaviour.

An experiment survey has been developed to measure current pro-environmental behaviour, value structure and goal-frame, test preferred Instagram posts, and measure intentions to act pro-environmentally in the future. Survey respondents were randomly assigned to a control group, which was not shown any Instagram posts. The experiment tested whether the provision of Instagram posts, which are framed in line with one’s goal-frame, creates a more effective message subsequently leading to an increase in future intentions to act pro-environmentally. The results of the analyses indicated that framing of an Instagram post based on pre-existing goal-frames does create a more effective message but does not lead to an increase in future intentions to act pro-environmentally. The differences in intentions to start acting pro-environmentally were not significantly different between the experiment and control group.

Further analysis revealed that the strongest predictor to increase intentions to act in line with the environment is a combination of high accessibility to a normative goal-frame (biospheric and altruistic values), low accessibility to a gain goal-frame (egoistic values) and university education. Additionally, it was detected that females are more likely to engage in pro-environmental behaviour, to have higher intentions to adjust their lifestyle as well as accessibility to a normative goal-frame. Implications of this study can be applied to future research as well as help organizations and governments to develop more targeted sustainable consumption campaign and policies.

Keywords: Pro-environmental behaviour, Online communities, the Integrated Framework for

Acknowledgements

Firstly, we would like to thank our supervisor Chiara Vitrano for her encouraging words, valuable advice and feedback. Also, we would like to express gratitude for the SALSU class of 2019. It is unique to see a group of students with such solidarity, positivity and support. Lastly, we are particularly grateful for the love, support and continuous encouragement of our families and close friends during the process of finishing this master thesis.

The authors, Karin and Vanessa

Glossary

Based on the Integrated Framework for Encouraging Pro-environmental Behaviour by Steg, Bolderdijk, Keizer and Perlaviciute (2014):

Self-transcendent values:

acting with collective interests in mind

Normative goals:

focus on morality and appropriateness of actions

Biospheric values:

key concern with nature and the environment

Altruistic values:

key concern with the welfare of others

Self-enhancement values:

acting with one’s individual interests in mind

Hedonic goals:

focus on direct pleasure and excitement

Hedonic values:

key concern with one’s feelings and enjoyment

Gain goals:

focus on money and status

Egoistic values:

key concern with safeguarding or increasing one’s resources and status

Environmental self-identity the extent to which we see ourselves as an environmentally friendly person Respondent A person who completed the survey

Participant A follower of an online community on social media

List of Abbreviations

PEB Pro-environmental behaviour IFB Intentions for future behaviour

IFEP The Integrated Framework for Encouraging Pro-environmental Behaviour NAM Norm activation model

VBN Value-belief-norm theory TRA Theory of reasoned action TPB Theory of planned behaviour

Table of Contents

Chapter 1: Introduction ... 1 1.1 Background ... 1 1.2 Research Gap ... 2 1.3 Research Objective ... 2 1.4 Layout ... 3

Chapter 2: Theoretical Framework ... 4

2.1 Defining Pro-environmental Behaviour ... 4

2.2 Online Communities and Social Power ... 9

Chapter 3: Methodology ... 12

3.1 Epistemological Position ... 12

3.2 Quantitative Survey Research ... 12

3.3 Research Design ... 12

3.4 Survey Development and Pre-study ... 12

3.5 Reliability and Validity ... 15

3.6 Sample and data collection ... 16

3.7 Ethical Considerations ... 16

3.8 Limitations ... 17

Chapter 4: Data Analysis ... 19

4.1 Initial Data Inspection ... 19

4.2 Survey Section Comparisons ... 25

4.3 Answering of the Research questions ... 27

Chapter 5: Discussion and Conclusion ... 35

5.1 Discussion ... 35

5.2 Conclusion ... 37

List of References ... i

Appendix A: Demographic data overview ... vii

Appendix B: Independent samples t-test summaries ... viii

Appendix C: Overview of sections Current PEB and Intentions for future behaviour ... x

List of Tables

Table 1. Examples of pro-environmental behaviour. Adapted from Derckx (2015), European Commission (2016),

Wynes and Nicholas (2017), EPA (2017) ... 5

Table 2. Overview of pro-environmental behaviour theories. (Authors mentioned in the first row of the table.) ... 7

Table 3. 17-E-PVQ by Bouman, Steg and Kiers (2018) ... 14

Table 4. Connection among survey sections (current PEB, message intervention, intentions for future behaviour) ... 15

Table 5. Demographic data summary ... 19

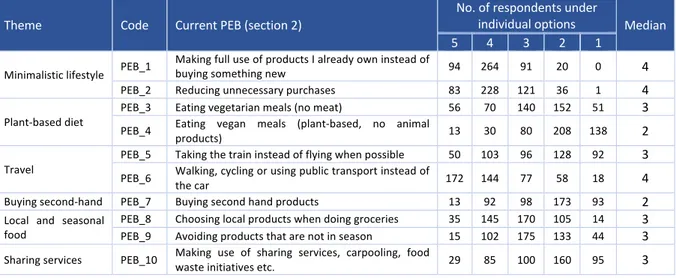

Table 6. Frequency table for responses in section Current PEB ... 21

Table 7. Current PEB - score interpretation ... 21

Table 8. Internal consistency of value types statements ... 22

Table 9. Frequency table for responses in section Intentions for future behaviour ... 24

Table 10. Intentions for future behaviour - score interpretation ... 24

Table 11. Pearson correlation coefficients for goal-frames and message intervention ... 28

Table 12. Summary of multiple regression analysis for goal-frames, dependent variable: message intervention . 28 Table 13. Chi-Square test of independence for match between goal-frame with message intervention and increase in future behaviour intentions ... 29

Table 14. Moderation analysis – overview of variables ... 30

Table 15. Summary of moderation analysis, dependent variable: intentions for future behaviour ... 31

Table 16. Summary of simple linear regression for current PEB and normative goal-frame, dependent variable: intentions for future behaviour ... 32

Table 17. Summary of Complete hierarchical regression analysis, dependent var.: intentions for future behaviour ... 34

List of Figures

Figure 1. The Integrated Framework for Encouraging Pro-Environmental Behaviour (IFEP). Adapted from Steg, Bolderdijk, Keizer and Perlaviciute (2014). ... 8Figure 2. Survey structure ... 13

Figure 3. Respondents’ goal-frames assessment ... 22

Figure 4. Message intervention – responses assessment ... 23

Figure 5. Visual diagram of change between current PEB and intentions for future behaviour ... 26

Figure 6. Illustration of H2 ... 29

Figure 7. Conceptual moderation diagram after Hayes (2017; p.221) ... 30

Figure 8. Statistical moderation diagram after Hayes (2017; p.227) ... 30

Figure 9. Message intervention as a moderator between gain goal-frame and future behaviour intentions ... 31

Figure 10. Current PEB as a predictor of future behaviour intentions in linear regression analysis ... 32

Figure 11. Normative goal-frame as a predictor of future behaviour intentions in linear regression analysis ... 33

Chapter 1: Introduction

“...It is time to re-examine and change our individual behaviours, including limiting our own reproduction (ideally to replacement level at most) and drastically diminishing our per capita -consumption of fossil fuels, meat, and other resources.”

World Scientists’ Warning to Humanity: A Second Notice (Ripple et al. 2017)

1.1 Background

In quest of limiting global warming to 1.5 °C, everybody has to do their part; governments to approve laws regulating the emission levels of the industries, businesses to act responsibly along their supply chains and developing further coping mechanisms; individual citizens to readjust their lifestyle choices. As stated by the European Environment Agency (EEA, 2018), households are the third highest greenhouse gas emitting sector (19%) after the energy sector (27%) and consumer goods industry (26%), followed by the agriculture (12%) and transport (11%). Reduction of household energy consumption is necessary to achieve a low carbon future and to meet the Paris Agreement as well as The Seventh European Environment Action Programme (7th EAP). In the long run, the environmental impact of households will be also contingent on the shift in individual behaviours, consumption patterns and lifestyle choices (Doyle, 2011; EEA, 2018; Fernandez, Piccolo, Maynard, Wippoo, Meili & Alani, 2016). Despite the obvious implications of individual behaviour on climate change, many people do not realize the connections and underrate their power to make an influence, withdrawing from the issue and passing the responsibility towards governments and businesses (Fernandez et al. 2016). While 10 years ago, the political and public scene lacked the acceptance of the situation, nowadays, the real gap is related to the transformation of the action-oriented knowledge for mitigation and adaptation. Most environmental problems, including anthropocentric climate change, caused by human behaviour, could be significantly reduced if people would engage in pro-environmental actions more consistently (Vlek & Steg, 2007).

Based on the Carbon Majors Report (2017), just 100 companies in the world are responsible for as much as 71% global emissions since 1988. Moreover, climate change is a planetary-scale threat and calls for reforms, which can only be imposed by the world’s governments. Political leaders and businesses must take immediate action to comply with the Paris Agreement and 7th EAP, while the behaviour of individual citizens, which can significantly minimize greenhouse gas emissions, is not sufficiently encouraged. We, the authors, acknowledge that great responsibility for combating climate change lies with the businesses and policy-makers. However, following Roberts (2018), we believe the individuals need to exercise their rights both as citizens and consumers to put their governments and businesses under pressure to make systemic transitions. Even though each individual action is not sufficient in itself to make a difference, the cumulative impact of many individual behaviours might be able to influence more sustainable methods. With the aim to raise awareness on the positive effects individual behaviour change can have in tackling climate change, number of organizations launch multiple pro-environmental campaigns, often via social media. Especially for non-profit organizations, communication takes a central role in their mission to preserve the environment. To the extent of our knowledge, these efforts are not taking advantage of existing theories from environmental psychology to effectively encourage pro-environmental behaviour (Fernandez et al., 2016). Moreover, social media initiatives with the aim to encourage pro-environmental behaviour are difficult to apply in practical settings. Challenges arise when it comes to how such initiatives are perceived by viewers and which viewers were finally encouraged to act pro-environmentally.

Adequyi and Adefemi (2016) argue that social media can be effectively used for communication purposes with the aim to influence behaviour, however, the use of the platforms must be done strategically, posts developed appropriately towards the audience, and effectively evaluated. In many ways, content mediated by organizations that aims to encourage pro-environmental action through social media can be improved. New styles and information are required, because they allow for a modern, inexpensive and unlimited way of communication progress towards sustainability (De Leo, Gravili & Miglietta 2016). In the last decade, social media became an integral part of many people’s lives. The

emergence of many social media platforms also introduced a new dimension for communication. Social media have the potential for extensive reach and widespread public engagement while being the most cost effective and fastest way to connect with the desired audience (Adewuyi & Adefemi, 2016). Research on social media has been conducted mainly on written words. Text-based social media platforms, such as Facebook or Twitter, may increase efforts to eliminate unhealthy behaviours like smoking cigarettes or drinking alcohol (Russmann & Svenson, 2016; Sucala, 2018). However, the biggest growth are experiencing platforms predominantly focused on images. The frontrunner of such platforms is Instagram, which has been repeatedly reported as the fastest growing social media platform in terms of both the overall users and time spent on the platform (Russmann & Svenson, 2016). Several studies already proved Instagram’s positive influence on food choices and physical exercise (Sharma & Choudhury, 2015; Fernandes, 2018).

Among online communities on Instagram, influencers provide great opportunities for behavioural change. A community of ethical influencers and participants has evolved. In this community, the influencers function as opinion leaders and encourage sustainable behaviour amongst their followers. A content analysis of this specific subset of online community has shown that mostly normative aspects, the ones reflecting exemplary behaviour, are mediated (Trager, 2018). Moreover, participants with a normative goal-frame, which focuses on appropriateness of actions, are more likely to become part of such a community. What the current literature is missing is how people with a more hedonic (seeking pleasure) and gain (safeguarding status and resources) goal-frames can be better targeted to behave more sustainably.

1.2 Research Gap

A few scholars have collected data on how pro-environmental behaviour is currently encouraged on social media by either organization, private individual’s celebrity activists or commercial influencers (Fernandez et al., 2016; Johnstone & Lindh, 2018). Specifically, the ethical influencer community on Instagram remains under-researched. Moreover, findings by Steg et al., (2014), Fernandez et al. (2018) and Trager (2018) have shown that initiatives of both organizations and influencers are mostly targeted at people with high biospheric and altruistic values and therefore a normative goal-frame, meaning people who are more likely to engage in sustainable lifestyle choices already. It is not clear which information and values were efficiently mediated when different goal-frames are dominant. Also, it is unclear how this data can be used to not only improve communication but also affect pro-environmental lifestyle changes (Fernandez et al., 2016).

1.3 Research Objective

We aim to fill the research gap by examining the role of individuals’ pre-existing goal-frames based on the Integrated Framework for Encouraging Pro-Environmental Behaviour (IFEP) by Steg, Bolderdijk, Keizer and Perlaviciute (2014) and the effectiveness of encouraging pro-environmental behaviour on Instagram. The objective of the study is to explore whether the provision of specific images and textual information on Instagram about pro-environmental behaviour can influence intentions and behavioural change of the recipients depending on their pre-existing goal-frames (normative, hedonic, gain). By looking at the semantics of mediated information and which goal-frames are targeted in that context, we can investigate efficacy of environmental communication on people’s intentions towards a more environmentally conscious lifestyle. This study targets millennial generation, those born between 1981 and 1996 (Dimock, 2019), which matches the main portion of Instagram users. In 2019, the 71% of them were between 18-34 years old (Statista, 2019).

Findings of our study are expected to provide recommendations for organizations and governments on how to make environmental communication via social media more effective.

After reviewing the existing body of literature on pro-environmental behaviour, social media and online communities, several hypotheses evolved.

Main Research Question:

What role does the individual goal-frame play in influencing intentions towards pro-environmental behaviour on Instagram amongst millennials?

RQ1: Does framing an Instagram post towards pre-existing goal-frames of an individual create a more effective message (H1a), subsequently leading to positive change in intentions to act pro-environmentally (H1b)?

H1a: The normative message will align with those individuals who possess altruistic and biospheric values (normative goal-frame). The hedonic message will align with those individuals who possess hedonic values (hedonic goal-frame). The gain message will align with those individuals who possess egoistic values (gain goal-frame).

H1b: A positive change in intentions to act pro-environmentally will occur when the Instagram post frame aligns with individual’s dominant goal-frame.

RQ2: How does the provision of Instagram posts about sustainability concerns change intentions to act pro-environmentally, in comparison to a control group?

H2: The provision of Instagram posts will increase intentions to act pro-environmentally because of greater knowledge about specific issues of sustainability (minimalistic lifestyles, plant-based diet, travel, buying second-hand products, eating local and seasonal food, and sharing services).

1.4 Layout

The first chapter (Chapter 1: Introduction) provided a context of the researched problem in a given background and presented research questions of the study.

The second chapter (Chapter 2: Theoretical framework) presents an in-depth review of the existing body of literature on encouraging environmental behaviour. The chapter starts by defining pro-environmental behaviour, reviews well established theories from the field of pro-environmental psychology and provides an explanation for selection of the theoretical framework this study is based on. The last section of the second chapter presents the power of online communities in encouraging pro-environmental behaviour and ethical influencers, which function as opinion leaders in those communities.

The third chapter (Chapter 3: Methodology) outlines the approach of the research, research design, data collection and survey development. This chapter also provides information about the sample of the survey, ethical considerations during and addresses limitations of the chosen methods.

The fourth chapter (Chapter 4: Data Analysis) is divided into three main parts, initial data inspection of individual survey sections, analysis of the data across sections, and answering of the research questions. The performed statistical analysis is explained in individual parts, describing the assumptions of each test and preseting the results.

The final chapter (Chapter 5: Discussion and Conclusion) interprets the results of the study with theoretical and practical implications and summarizes the key findings from the study while providing final remarks and laying out avenues for future research.

Chapter 2: Theoretical Framework

The following chapter provides an in-depth overview of the existing literature on pro-environmental behaviour and ethical online communities. Firstly, pro-environmental behaviour along with high and low impact examples will be defined. The second paragraph introduces the reader to the Integrated Framework for Encouraging Pro-environmental Behaviour (IFEP), the main theoretical framework of this thesis. There are two main reasons why this framework was selected. Mainly, the IFEP’s strong standing in the field of environmental psychology. Secondly, the study builds on a previous research by one of the authors, which put forward the use of a quantitative approach for testing this framework. The last paragraph explains the role of ethical online communities in the context of encouraging pro-environmental behaviour. Also, the role of the ethical influencer as an opinion leader is discussed.

2.1 Defining Pro-environmental Behaviour

Throughout history, the impact of human actions on the environment has been caused by the desire for, among others, physical comfort, mobility, enjoyment and personal security (Stern, 2000). The protection of our environment became one of the main drivers for our decision-making in the last century. Pro-environmental behaviour (PEB) was defined by a number of researchers throughout the years. Following Stern (2000), in this study, we define pro-environmental behaviour as all actions that “change the availability of materials or energy from the environment or alter the structure and dynamics of ecosystems or the biosphere itself” (p. 408).

In order to minimise anthropogenic climate change caused by mankind, it is essential to identify specific actionable types of PEB. The approach adopted in our study focuses on environmental protection in terms of reducing pollution, use of resources and waste. In addition, the study targets specific actions performed by individuals. Table 1. presents an overview of PEB collected from a number of sources (Derckx, 2015; European Commission, 2016; Wynes & Nicholas, 2017; EPA, 2017). The overview of the specific behaviours can be classified into the following categories: electricity, water, transportation, food, materials, waste, biodiversity and civic actions. Each individual behaviour is placed into the category where it has the biggest impact, even though it affects other categories as well (e.g. action ‘avoiding washing dishes by hand if having a dishwasher’ has an impact on both water and electricity). All of the actions mentioned in the table below can have direct environmental consequences and even though, the final impact may be small, the independent behaviour occurring regularly by many individuals becomes significant (Stern, 2000; Derckx, 2015). Moreover, the behaviours with the biggest impact (high and moderate impact actions) are highlighted following the research study by Wynes and Nicholas (2017), which calculated potential to reduce greenhouse gas emissions of these behaviours. The studies investigated individual and household impacts of human behaviour on environmental footprint. Scenarios included planting trees, dietary choices and transport. The authors state that these actions have great potential to contribute to systemic change and substantially decrease personal emissions. The highest impact action according to Wynes and Nicholas (2017), having one fewer child, was excluded due to focus on behaviours within the eating habits, purchase, use and disposal of personal and household items.

Table 1. Examples of pro-environmental behaviour. Adapted from Derckx (2015), European Commission (2016), Wynes and Nicholas (2017), EPA (2017)

Electricity

- Buying energy efficient products

- Filling up a washing machine, choosing the lowest temperature and skipping a pre-wash cycle - Good wall insulation

- Hang drying clothing instead of using tumble dryer - Lowering the heating when leaving the house - Purchasing green energy

- Putting on a sweater instead of turning on the heating - Turning off the laptop when not needed

- Turning off the light in rooms that are not in use - Using less light in rooms

Water

- Avoiding washing dishes by hand if having a dishwasher, but only using when filled up and on ‘eco’ mode - Closing the tap during tooth brushing

- Flushing the toilet with rain water - Refilling water bottles

- Taking a short shower

- Washing the car by hand instead of using a water hose - Washing the fruits and vegetables in a bowl rather than

under a running tap

- Watering the garden only when it has not rained in days Transportation

- Avoiding flying

- Buying electric car or car with good fuel economy - Eliminating unnecessary travel

- Using car sharing or carpooling services when possible - Using public transport instead of the car

- Using the bicycle when doing groceries instead of the car Food

- Avoiding products that are not in season - Buying organic fruit and vegetables - Eating less meat

- Eating local

- Not buying meat or fish of rare species - Plant-based diet

- Reusing food waste/leftovers Materials

- Avoiding use of paper (e.g. printing)

- Bringing own reusable bag when doing groceries - Buying clothes of a pro-environmental brands - Buying rechargeable batteries

- Reducing materialistic consumption - Repairing materials

- Swapping, selling or donating clothes, furniture and household items that are no longer needed Waste

- Avoiding products in plastic packaging - Avoiding use of ‘throw away’ materials - Buying second hand products

- Only boiling as much water as needed in a kettle - Recycling

- Separating waste Biodiversity

- Avoiding use of pesticides

- Feeding birds in the winter - Planting trees and flowers

Civic Actions

- Influencing employer’s actions - Spreading awareness

The provision of information about sustainability-related issues is a critical part of changing an individual’s behaviour. A lack of understanding about an environmental issue can pose a barrier to change, as individuals are often not aware of the effects their behaviour has. Schultz (2002) argues that there is a causal relationship between behaviour and knowledge. Individuals must be provided with information about how and why there should make adjustments, in this context pro-environmental action they should engage in and why. The relationships between cause and action of environmental problems are complex and have only recently received attention on the media. While the environmental literacy is important, environmental education should, among others, advocate benefits for society as well as the individual. According to Ritchie (2017), simple information provision is often not enough to encourage pro-environmental behaviour. It must be targeted and strategically designed taking into consideration moral and normative aspects, but also emotions and contextual factors. Environmental psychology is dedicated to understanding of these aspects. Hence, the theories from this field were examined to find the best for our research.

2.1.1 Theories of pro-environmental behaviour (PEB)

In the field of environmental psychology, several researchers addressed the motivations behind pro-environmental behaviour. Thøgersen (1996) argues that pro-pro-environmental behaviour is mainly dependent on individuals’ morality, on a person’s environmental concern and evaluation about what is right or wrong. Stern (2000) agrees on the importance of normative concerns but believes that there are multiple interacting factors affecting a person’s behaviour, such as convenience, enjoyment or price. The view of multiple factors is acknowledged by a number of scholars (e.g. Gollwitzer & Bargh, 1996;

Bamberg & Schmidt, 2003; Harland, Staats & Wilke, 1999). However, the theories and models, which have received the most attention consider only one major motivational factor, e.g. the norm activation model (NAM) stresses person’s moral obligation; theories of affect emphasize hedonic aspects of environmental behaviour; the theory of planned behaviour (TPB) focuses on self-interests, which make people act in line with the environment.

The norm activation model (Schwartz, 1977; Schwartz & Howard, 1981) focuses on altruistic environmentally-friendly behaviour. Based on the NAM, personal norms, such as moral obligation, are the main triggers to engage in pro-environmental behaviour. The activation of the normative concern occurs when individuals are aware of the consequences of a certain action and believe that they could be averted. The NAM has later been advanced into the value-belief-norm theory of environmental behaviour (VBN; Stern, 2000), which elaborates on human-environment relations and value structures influencing individual’s awareness of consequences and ascription of responsibility. By contrast, the theory of reasoned action (TRA; Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980) and its extended version the theory of planned behaviour (Ajzen, 1985, 1991) suggest that individuals are solely behaving for their own benefit, self-interest motivation, e.g. money, status. According to TBP, the individual’s behaviour depends on the intention, which results from the attitude towards the specific behaviour, social norms and perceived behavioural control (Ajzen, 1991).

A number of researchers suggest the role of affect in environmental behaviour. Theories on affect see the emotions, energy level and arousal as decisive to engage in pro-environmental behaviour (Pelletier, Tuson, Green-Demers, Noels & Beaton, 1998; De Young, 2000). However, the affect in connection to environmental behaviour has been addressed only in a few studies. The research by Pelletier, Tuson, Green-Demers, Noels and Beaton (1998), measures an individual’s level of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation for environmental behaviours using the Motivation Toward the Environment Scale (MTES). The findings indicate that people are less likely to act pro-environmentally because of the morality of the act and more likely because of the derived pleasure and satisfaction (Pelletier et al.,1998). Similarly, De Young (2000) assures that certain environmental behaviours “are worth engaging in because of the personal, internal contentment that engaging in these behaviours provides” (p. 515).

The aforementioned theories study the motivational factors in isolation, rather than between themselves, which may hide other interrelated and interdependent elements. Therefore, they have been proven to be successful in explaining different situations while failing to interpret others. For example, NAM and VBN are proven to be successful in low-cost environmental behaviour, such as willingness to change (Steg, Dreijerink & Abrahamse, 2005), TBP in meat consumption (Graham & Abrahamse, 2017), and affect theories in car-use (Nilsson & Küller, 2000).

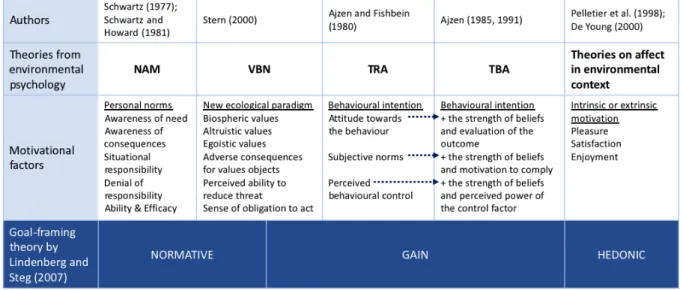

Unlike the aforementioned theories, goal-framing theory proposed by Lindenberg and Steg (2007) is based on multiple motives (goals) encouraging or preventing pro-environmental behaviour. The theory further examines the interaction between different goals, which influence person’s actions in a given situation, so-called ‘frame’. Moreover, the goal-framing theory has emerged from the preceding theories and further research in cognitive social psychology (Lindenberg & Steg, 2007). The theory suggests three goals, which motivate people’s environmental behaviour, hedonic goals, gain goals and normative goals (Lindenberg & Steg, 2007). People with a hedonic goal focus on their feelings, seeking pleasure and enjoyment. Gain goals lead people towards the most self-beneficial actions, especially related to their status or resources, e.g. money, time. Normative goals prompt individuals to consider the appropriateness, such as showing exemplary behaviour and acting as they think they ought to (Lindenberg & Steg, 2007). According to Lindenberg and Steg (2007), people’s behaviour is governed by more than one goal in any given time, but one of the goals often dominates in a specific situation, the focal goal. The leverage of the focal goal may be reinforced by the sub goals, however, more frequently are the goals in conflict. The resulting behaviour is then dependent on the strength of the focal goal, which usually triggers selective attention to processes, i.e. the framing effect (Lindenberg & Steg, 2007). Lindenberg and Steg’s goal-framing theory (2007) coincide with the other theories and models from the environmental psychology. Table 2. below depicts the corresponding factors emphasized by individual theories. NAM and VBN theories focus mainly on normative concerns, which is comparable with normative goals in goal-framing theory. Although, VBN theory, as advanced version of NAM also

considers egoistic values perceived in a gain goal-frame. TRA and TBA focus on factors explained in goal-framing theory as gain goals, since they consider self-interest as the major influence for individual’s behaviour and also the norms are discussed in relation to subjectively perceived positive and negative outcome. The theories on affect in environmental context stress the role of emotions in influencing the behaviour as people are likely to engage in pro-environmental behaviour when they expect some kind of satisfaction or enjoyment. These theories correspond with the hedonic goals of goal-framing theory.

Table 2. Overview of pro-environmental behaviour theories. (Authors mentioned in the first row of the table.)

Goal-framing theory was later advanced to the Integrated Framework for Encouraging Pro-Environmental Behaviour (IFEP) by Steg, Bolderdijk, Keizer and Perlaviciute (2014). The relative power of the three goals, hedonic, gain and normative, manages what information a person perceives, what knowledge the individual finds the most reasonable and how the individual acts in a specific situation (Steg et al., 2014). The IFEP draws on the three discussed goals and adds four underlying values influencing accessibility to these goals as illustrated in Figure 1 below. Hedonic values reflect an individual’s main interest in enjoyment and effort reduction. Egoistic values make a person safeguard his or her own resources. Altruistic values disclose a concern with the well-being and welfare of others, such as equality. Biospheric values reflect the main consideration for nature and the environment, e.g. preventing pollution. Moreover, hedonic and egoistic values are considered self-enhancement values, which reflect a person’s key consideration about his or her own interests; while altruistic and biospheric values are considered self-transcendent values revealing a person’s key consideration about collective interests. An individual possesses all of the values in varying intensities while being influenced by the situational cues and perceived norms. The intensity of specific values then influences accessibility to a certain goal-frame. The hedonic values influence accessibility to hedonic goal, egoistic values to gain goals, and altruistic and biospheric values influence accessibility to normative goals.

Steg et al. (2014), argue that sympathizing pro-environmental behaviour is a crucial, yet difficult task, especially as most people want to live their life’s in a convenient way. For example, commuting by car takes for less time than commuting by public transport and may, therefore, be prioritized. Even individuals with highly normative behaviour would not act pro-environmentally if expenses are too high, leading them to focus on hedonic and gain goals. Only targeting hedonic and gain goals is not recommended by Steg et al., (2014) as it could result in people only acting pro-environmentally when it is most attractive and convenient (Thogersen & Crompton, 2009).

Lindenberg and Steg (2013a; 2013b) argue that moral hypocrisy arises, when hedonic and gain goals are targeted. Batson, Thompson, Seuferling, Whitney and Strongman (1999) define moral hypocrisy as appearing moral without acting based on those morals, so saying one thing but doing another. Individuals then feel the need to appear as morally acceptable, satisfying their need to be seen as a good person, even though their action might not be as ethical. However, Lindenberg and Steg (2013a; 2013b)

found that moral hypocrisy is more likely when hedonic and gain goals are stronger than the normative goal. In an experiment, normative goals were intentionally strengthened by reminding individuals of their previous pro-environmental actions or letting them observe others to behave pro-environmentally, which lead participants to engage in high-priced pro-environmental behaviour (Lindenberg & Steg, 2013a). Furthermore, participants showed strict moral values and justified their behaviour. The effect of experiments, which focused on hedonic or gain goals in encouraging pro-environmental behaviour was very rather momentary. Therefore, Steg et al. (2014) propose that all three goals are important in encouraging pro-environmental behaviour, however, it is important to target normative goal to make pro-environmental actions sustainable. This argument is supported by other studies, which argue that normative goals can be supported by the hedonic and gain goals in the background (De Young, 2000; Carrus, Passafora & Bonnes, 2008, Bolderdijk, Steg, Geller, Lehman & Postmes, 2012).

As already mentioned, the idea of substantial pro-environmental behaviour builds on values. Central is the value that humanity only has one planet that should be maintained as a healthy and supportive environment. Pro-environmental behaviour concerning food consumption, personal waste management exert a catalytic impact on the well-being of individuals and the future of this planet (Bokova, 2015). Steg et al. (2014) indicate that the strength of normative goals is contagious on particular values and situational cues. Individuals who possess supporting values are especially prone to environmental behaviour when values are paired with situational cues. Some situational factors harmonize with biosphere values (valuing the planet and nature), while others hinder pro-environmental behaviour, even though people are environmentally conscious.

Situational cues are cues which indicate individuals to act and respond in a certain way (Carlston, 2013). Subsequently, they can influence the goal frame, by pushing normative, gain or hedonic goals in the cognitive foreground. Therefore, they are either norm-violating or norm-supporting. Moreover, Steg et al. (2014) argue that the so-called environmental self-identity affects pro-environmental behaviour. One’s environmental self-identity reflects how pro-environmentally an individual sees itself. Notably, several studies have shown that females possess a higher environmental self-identity and are more likely to engage in pro-environmental behaviour (Stern, Dietz & Kalof, 1993; Hunter, Hatch & Johnson, 2004). Thanks to its comprehensive nature, we believe the extended version goal-framing theory, the IFEP, is the most suitable for further exploration of encouraging pro-environmental behaviour within the underexplored context of online communities.

Figure 1. The Integrated Framework for Encouraging Pro-Environmental Behaviour (IFEP). Adapted from Steg, Bolderdijk, Keizer and Perlaviciute (2014).

2.2 Online Communities and Social Power

In the context of encouraging pro-environmental behaviour, online communities can provide a place for the exchange of common interest and values, on which problem like climate change and unsustainable consumption can be addressed and discussed. Subsequently, social media offer a broad spectrum of possibilities as platforms like Instagram combine public and personal communication (Meikle, 2016). Ways of communication converge and the barriers between public media and personal communication fade. “Public messages – news stories, advertisements, political speeches, – are copied and circulated, repositioned and re-contextualized every day by hundreds of millions of users of Facebook and Twitter, Google and YouTube, Instagram and Pinterest” (Meikle, 2016, p.12). Social media became a source of news and political reasoning for many millennials.

Individuals’ values and beliefs are influenced through social media and individuals who often play political roles in social movements. According to Fuchs (2017), the reality is built by the media, which therefore wields a social power. This power is dependent on values and meanings understood by society as moral, pressing and simply worth debating about (Fuchs, 2017). Such platforms are not just mediating symbolic power, but socio-material spaces where structures of “symbolic, economic, political, and social power manifest” (Fuchs, 2017, p.93). Social and environmental issues are discussed, stressed and shared in order to raise awareness and call for action.

Fuchs (2017) argues that the unequal distribution of cultural resources, meaning reputation, allow elites to have more influence, control and power over social media. Whereas this is true to some degree, social movements have been started by individuals who do not possess a great deal of financial or cultural resources. Individuals can start a movement by doing something irregular and sharing their unpolished, direct opinion on a certain issue i.e. climate activist Greta Thunberg. Participants in an online community can have explanatory power which specifically speaks to a young and powerful group of consumers on social media (Johnstone & Lindh, 2018; Bucic et al., 2012). Instagram and organizational change communication.

2.2.1 Shared leadership and influencers as opinion leaders towards sustainability

In online communities, influencers and participants create a culture of online experts by which they attract new followers (Bakshy, Hofmann, Mason & Watts, 2011). Social media hold power over the minds of individuals, particularly young individuals, who are actively picking up on the latest news and trends (Djafarova & Rushworth, 2017). In recent years, influencers have gained popularity in online communities. They are an integral part of the community, are in a leading position, enjoy trust amongst the participants and share credible and actionable information. In the context of online communities and also in this paper, participants are referred to as those who actively or inactively participate in the online community (Kozinets, De Valck, Wojnicki & Wilner, 2010). Those are the social media users, who consume content and, in some cases, repost, like and comment. Influencers are private individuals, who mainly share information on personal values and practices, make a living through company cooperation’s, paid advertisements and other communication incentives. Whereas today, ‘influencers’ have the call to be wanting to sell materialistic goods, other influencers focus on mediating political issues and engagement in societal and environmental issues. Instead of being sponsored by large fast-moving consumer good companies, those “ethical Influencers” are supported by government organizations, ethical brands and non-profits.

Sustainability is no longer just a technological and scientific issue but became a social and cultural opportunity to lead and drive sustainable change (Wright & Nyberg, 2015). Ethical influencers can function as change agents. There seems to be a sense of belonging to an online community that functions as a social system, a part of a culture, which is connected by the influencer (Johnstone & Lindh, 2018). Thus, the influencer exists only because of their followers. Consumers seek ‘social proof’, by which they act on knowledge and lifestyles of others (Amblee & Bui, 2011). Basically, young individuals, millennials in specific, are influenced by crucial considerations related to social issues, where they seek credible information from sources they trust (Burke, Eckert & Davis, 2014). Gathering such credible information becomes a natural and integral part of a millennial’s life, which are caused by an individual’s identity and value structures. This process is psychological and may not be explicitly

transferrable to sustainability issues. However, there is something particular about this process of normalized or incidental learning, that can help to translate environmental concern into pro-environmental action (Newton, Tsarenko, Ferraro & Sands, 2015).

Pro-environmental behaviour is a research area which needs further practical suggestions tailored to upcoming generations. Essentially, “sustainability must be tackled beyond the lens of managerial focus, we must recognize what communication is” (McDonagh & Prothero, 2014, p. 1202). Previous research on leadership in online communities has focussed on the small share of people in online communities that hold a leadership role. However, in Online Communities on Instagram, the concept of shared leadership emerges. Not only individuals in higher level positions have a say, but every member of the community can show leadership behaviour. An individual may use a different type of leadership like e.g.. transactional and their influence largely depends on their legitimacy (Huffacy, 2010). Casalo, Flavian and Ibanez-Sanchez (2018) analysed data from 808 Instagram followers and found that followers are mostly influenced by originality and uniqueness of the leader. The influencer, who in this case is the leader, uses opinion leadership and serves as a source of advice for participants of online communities. Findings have shown that this form of opinion leadership on Instagram influences behavioural intentions (Flavian & Ibanez-Sanchez, 2018). Finally, if the account matches the individual’s values, individuals are more prone to follow the opinions and advice given. This study particularly focused on fashion but the results could be meaningful for the ethical online community. A study by Zhu, Kraut and Kittur (2012) on the effectiveness of shared leadership in online communities are congruent with the finding that legitimate leaders were more influential than regular peer leaders. Moreover, any leadership behaviour performed by leaders at all levels influenced participants motivation. In conclusion, the means through which leadership is established and maintained are high communication activity, the credibility of the influencer, network centrality and the use of effective, assertive and linguistic variance in posts that were made (Huffaker, 2010). Ethical influencers mediate personal values and lifestyles that reflect high impact sustainability action such as a plant-based lifestyle, reducing unnecessary purchases and adequate waste management. Such behaviour is framed in terms like minimalism and zero waste. Also, ethical influencers aim to provide detailed information from credible sources like academic publications and official government information. Such credible information builds trust in the community. Also, ethical influencers try to be authentic (Trager, 2018). They encourage users to do their best and not aim to be perfect in their efforts.

When looking at the influence ethical online communities exert on millennials, the question as to how consciously this process happens might arise. Influencers in ethical online communities have long been an under-researched area. In 2018, Johnstone and Lindh (2018) published their paper on Sustainable Influencers and described the power of cognitive change by means of the theory of unplanned behaviour. The authors use a mixed methods approach, including a survey, focus groups and interviews to explore the relationship of Influencers sustainability and the millennial subset. The paper is built on the theory of planned behaviour (mentioned in subparagraph 2.1.1), which suggests that behaviour is learned after a sequential series of stages, which are linked to one’s values and attitudes (Ajzen, 1991). The “decision balance scale” is used to weigh decisions against each other until a critical point is reached and pro-environmental behaviour occurs. Theoretically, beliefs presuppose attitudes, attitudes form intentions, which turn into action (Carrington, Neville & Whitwell, 2010). Even though the theory of planned behaviour is widely used, other behavioural, moral and situational factors move in the cognitive foreground of younger generations (Kumar, Manrai & Manrai, 2017). In the study about sustainable influencers, Johnstone and Lindh (2018) argue that both intentions and behaviour were affected by Ethical Influencers. The authors argue that millennials give a high degree of value to social media and influencers as motivators, rather than the cause of the problem. The influencer and other participants in the ethical online community naturally serve as proof-point for millennials actions and beliefs.

Further, attitude and value forming are preconditions to behavioural change and must be considered for the millennial subset of individuals who often have hedonistic values and are subject to peer pressure and other socialization processes (Alexander & Sysko, 2012). For other millennials, sustainable behaviour is egoistic, causing some to remain ignorant and unopen to PEB on purpose (Davies & Gutsche, 2016). Burke et al. (2014) argue that accidental circumstances can translate into sustainable

consumption practices. However, in this study, we focus on the IFEP, in which hedonic, gain and normative goal-frames exist in an individual’s mind, however one is focal in a given situation.

2.2.2 A critical view on social media

Social media should be enablers of freedom. Freedom of expression should enable equal opportunities and allow individuals to better understand their lives (De Croo, 2015). This phenomenon is changing due to regulations in data protection laws and shifts of power on the media. Individuals use the information they consume on social media as a base to justify their behaviour (Pariser, 2011). Pariser (2011) frames a “filter bubble” as a state in which web results are showing personalized content based on an algorithm that considers individual preferences. The filter bubble effect can reach a stage in which the individual is unaware of anything outside their bubble. In this stage, contradicting news, opinions and other information do not reach the media user any longer. Users, therefore, are less likely to get exposed to conflicting aspects and as a result are isolated in their “filter bubble” (Osburg & Lohmann, 2017). What the filter bubble contains is largely determined by the pre-existing preferences of the user. In order for the content to change, the user must actively look for content that varies from its current stance. Companies already use paid advertisement and collaborations to make users aware of new trends and products. There is tremendous potential for organizations wishing to encourage pro-environmental behaviour online to bring in critical information in a millennials filter bubble that would eventually lead to more pro-environmental action. Social movements can also be started by companies and campaigns with the aim to encourage pro-environmental behaviour must be personalized. Behavioural change is a complex research field, which however offers tremendous potential if combined with opportunities social networking sites offer.

With more control in the form of e.g. paid advertisements, algorithms, big data and bots on the internet, people become increasingly concerned that their privacy will diminish (Osburg & Lohmann, 2017). Trust in an organization can influence this concern. Whereas data usage offers opportunities for a digital society, technologies should be aligned with social expectations. There is a specific demographic that tends to trust social media and technological development more than others. These are the informed public, who consist of university graduates that follow the media and have income in the top 25%. Those who understand the challenges of today’s society are more willing to adapt to and trust recent developments (Edelmann, 2016). Based on Edelmann’s annual Trust barometer (2015), individuals trust mostly occurs when it comes to technology and business growth targets. Individuals were less concerned with the aspects of improving people’s lives and making the world a better place (Edelmann, 2015). In conclusion, to enable social sustainability and societal acceptance, trust is needed. Trust in data, algorithms, and bots is the deciding factor in whether a society can function (Edelmann, 2017).

Chapter 3: Methodology

The methodology chapter outlines the approach used in this study and research design, followed by explanations of the survey structure, research sample, ethical considerations and acknowledgments of limitations of the chosen methodology.

3.1 Epistemological Position

This paper uses a quantitative approach to answer the stated research questions. The research process was focused on establishing new truths through empirical methods. Truths about reality can only be known in an imperfect fashion, which is also referred to as post-positivism (Creswell, 2012). Post-positivists accept that theories, background, knowledge, and values of the researcher can influence the design and objective of the research. We do not exclude that the selection was to some degree determined by the researchers’ personal interest. Post-positivism emphasizes meanings and seeks to clarify social concerns. Ryan (2006) describes post-positivism as broad, combining theory and practice, allowing room and acceptance for the researcher’s commitment to the topic, noting that there are several correct techniques to answer the research question. The idea of positivism, which emphasizes rationalism and empirical knowledge remains the standard of modernism. Post-positivism, however, tries to understand the world by means of numeric measurements to asses’ theories and explain certain phenomena (Creswell, 2012).

3.2 Quantitative Survey Research

To understand phenomena in a postpositivist manner, quantities of certain behaviour need to be measured. Survey research is a way in which this can be achieved. Survey research is defined as “the collection of information from a sample of individuals through their response to questions” (Check & Schutt, 2012, p. 160). It is an adequate method to explore human behaviour and therefore often used in social and psychological science (Singleton & Straits, 2009). In order to ensure high-quality research outcomes, we follow certain research strategies; a representative sample of a subgroup, a survey method and strategies to reduce nonresponse error, which we elaborate on in the following (Ponto, 2015).

3.3 Research Design

This study aimed to explore the influence of information provision on individuals’ perception and their intended behaviour. An online survey experiment was used for data collection, enabling the researchers to compare the respondents’ intentions to act pro-environmentally before and after a message intervention (Guterbock, 2010). This message intervention will consist of Instagram posts, which will be shown to a randomly assigned experiment group. The best scenario is an even 50:50 split between experiment and control group (White, 2019). However, research involves trade-offs and the decision on how many people of the sample to allocate to which group can be challenged. According to White (2019), statistically speaking, very minimal differences occur when we decrease the control group size to 40%, 30% is an acceptable compromise. Based on the validated control group sizes used by Powers et al., (2005), Katz et al., (2011), Keihner et al., (2011#) and McCarthy et al., (2012), we have decided to opt for the 60:40 split. Remaining 40% of respondents, control group, will not be provided with any further information before answering the questions about their intended behaviour. The initial approach will be deductive by using the existing theories and developing hypotheses to be tested in an online survey. The findings of the research will be approached inductively, exploring the data and developing a theoretical explanation. The research is focused on empirical data collection, meaning that results from the survey are primary data.

3.4 Survey Development and Pre-study

The survey development process will be explained in this chapter. The survey was conducted using the platform SoSci, which is freely accessible if users can verify non-profit academic use. To adjust the

order and features of the survey, the researchers used PHP programming. A pilot study was conducted to see if people easily understood the framing of the questions and if the survey results give answers to the main research question.

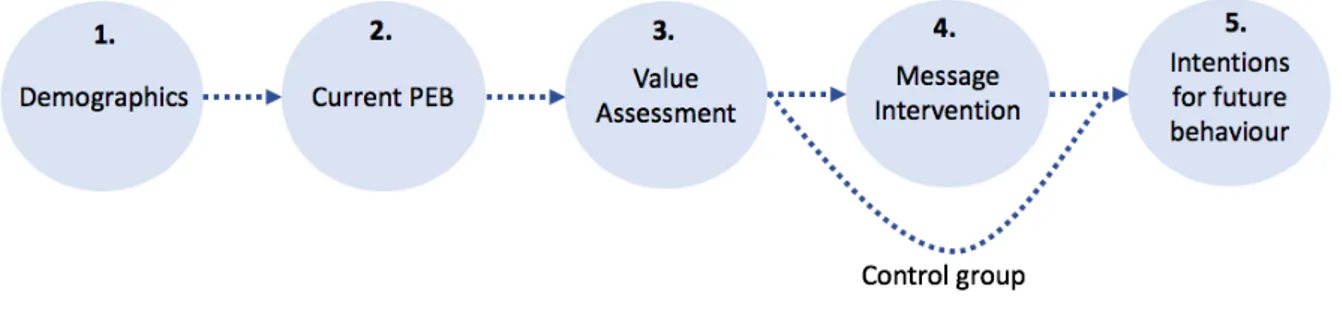

The survey was categorized into five sections (see Figure 2.). The first section asked questions about participant demographics. The second assessed current pro-environmental behaviour. The third part included a value assessment based on a validated survey adapted for environmental research, E-PVQ. Message intervention, section four, was shown only to an experiment group (60%), which was randomly assigned at the beginning of the survey using PHP programming. Final section, asked respondents about their intentions to behave pro-environmentally in the near future. Due to the limited scope of this study, we will not be able to asses actual future pro-environmental behaviour and therefore measuring intentions. For the full survey used in the research, refer to Appendix D.

Figure 2. Survey structure

The demographics section included questions about personal characteristics essential to establish respondents’ attributes for further analysis and outcome interpretations. The questions included age range, having an Instagram account, ethnicity, gender, geographical location, education, income and having children. For ethical reasons, income and ethnicity were excluded after pre-testing of the survey. Moreover, the participant consent agreement was displayed in the beginning. If respondents selected “don’t agree” the survey ended.

The question about age was asked at the beginning of the survey to assess individual’s suitability for the study (the target group is further explained in paragraph 3.6). If person was not eligible for the study, the survey was redirected to page expressing appreciation for the interest in the study with an explanation about the target group.

Second section, Current PEB, was built on the literature on high-impact pro-environmental actions reviewed in paragraph 2.1. The statements for this section were developed in accordance with the most influential behaviours to reduce greenhouse gas emissions (high and moderate impact actions from Table 1.). In total were developed ten statements in six themes, which depict Table 4. The themes were minimalistic lifestyle, plant-based diet, travel, buying second-hand products, eating local and seasonal food, and sharing services. The study primarily focuses on behaviours that any individual can generally perform. With this in mind, it was decided to omit some of the influential behaviours (e.g. purchasing green energy or buying electric car).

The value assessment section was based on an existing and validated Environmental Portrait Value Questionnaire (E-PVQ) by Bouman, Steg and Kiers (2018). E-PVQ is adapted version of the widely validated and cited The Portrait Value Questionnaire (PVQ; Schwartz, Melech, Lehmann, Burgess, Harris & Owens, 2001) for the use in environmental behaviour research. The questionnaire includes 17 statements for measuring 4 values consistent with the IFEP (see Figure 1.). The full E-PVQ exhibits Table 3. below. Respondents were asked to read brief descriptions of different people and indicate how much this person is like them on a 5-point scale. The order of individual statements was randomized not to disclose the cluster to each item belongs as advised by Bouman et al. (2018). Also, using PHP programming, the object pronouns in each value statement changed based on the respondent’s gender specified at the beginning of the survey. If the respondent selected male gender, the statement read ‘him’, female gender showed object pronoun ‘her’. Finally, if person selected other gender, the object pronoun read ‘they’. The singular form of ‘they’ for other gender option is not included in the original

E-PVQ and was added to the survey for gender-neutral meaning. The value assessment section subsequently led to goal-frame assessment as the intensity of different values (biospheric, altruistic, hedonic, egoistic) influence accessibility to individual goal-frames as explained in the subparagraph 2.1.1.

Table 3. 17-E-PVQ by Bouman, Steg and Kiers (2018) Biospheric value

Bio1 Bio2 Bio3 Bio4

It is important to [him/her/them] to prevent environmental pollution. It is important to [him/her/them] to protect the environment. It is important to [him/her/them] to respect nature.

It is important to [him/her/them] to be in unity with nature.

Altruistic value Alt1 Alt2 Alt3 Alt4 Alt5

It is important to [him/her/them] that every person has equal opportunities. It is important to [him/her/them] to take care of those who are worse off. It is important to [him/her/them] that every person is treated justly. It is important to [him/her/them] that there is no war or conflict. It is important to [him/her/them] to be helpful to others.

Hedonic value

Hed1 Hed2 Hed3

It is important to [him/her/them] to have fun.

It is important to [him/her/them] to enjoy the life’s pleasures. It is important to [him/her/them] to do things [he/she/they] enjoy/s.

Egoistic value Ego1 Ego2 Ego3 Ego4 Ego5

It is important to [him/her/them] to have control over others’ actions. It is important to [him/her/them] to have authority over others. It is important to [him/her/them] to be influential.

It is important to [him/her/them] to have money and possessions. It is important to [him/her/them] to work hard and be ambitious.

Section four included the message intervention, consisting of the provision of environmental information formulated in an actionable way. Each respondent, who was randomly assigned to an experiment group, was shown six themes of Instagram posts. The posts were randomized to ensure respondents wouldn’t detect a pattern of the three types of posts. The themes were the same as in the second section. Each theme included three posts constructed according with the three goal-frames, one normative, one hedonic and one gain. The respondent was asked to select the one, which speaks to him/her/they the most. As each picture was aligned to a different goal-frame, it promoted different aspect of the theme. For example, the theme buying second-hand products encouraged to buy second-hand to help the environment (normative goal-frame), to find unique pieces (hedonic goal-frame) and to save money (gain goal-frame). All posts included an image and detailed description based on credible academic sources. The images under the same theme featured similar layout to decrease the bias of selecting solely by visual attraction. The posts in this experiment were created by the authors of this paper to ensure consistency and fit.

The last part of the survey aimed to assess the respondent’s intentions for future behaviour. The sentences replicated the statements in current PEB (section 2), but in this section were formulated in a future tense to determine individual’s intentions to start acting more pro-environmentally.

Table 4. Connection among survey sections (current PEB, message intervention, intentions for future behaviour) High-impact PEB

(from Table 1.) Current PEB (section 2) Message Intervention (section 4) Intentions for future behaviour (section 5)

Reducing materialistic consumption

Making full use of products I already own instead of buying

something new Minimalistic lifestyle

I aim to make full use of products I already own instead of buying something new

Reducing materialistic

consumption Reducing unnecessary purchases Minimalistic lifestyle I aim to reduce unnecessary purchases Plant-based diet;

Eating less red meat Eating vegetarian meals (no meat) Plant-based diet I aim to eat vegetarian meals (no meat) Plant-based diet;

Eating less red meat Eating vegan meals (plant-based, no animal products) Plant-based diet I aim to eat vegan meals (no animal products) Avoiding flying;

Using public transport instead of the car

Taking the train instead of

flying when possible Travel I aim to take the train instead of flying when possible Avoiding flying;

Using public transport instead of the car

Walking, cycling or using public

transport instead of the car Travel I aim to walk, cycle or use public transport instead of the car Buying second hand

products Buying second hand products Buying second-hand products I aim to buy second hand products Eating local Choosing local products when doing groceries Local and seasonal food I aim to choose local products when doing groceries Avoiding products that

are not in season Avoiding products that are not in season Local and seasonal food I aim to avoid products that are not in season Using car sharing

services when possible; Reusing food waste

Making use of sharing services, carpooling, food waste

initiatives etc. Sharing services

I aim to make use of sharing services, carpooling, food waste initiatives etc.

The pilot study was performed online using the feedback and testing function provided by SoSci software tool. Two more feedback sessions were accompanied by a researcher so that the respondent could directly express any ambiguity. After the pilot study, questions in the section “current PEB” and “intentions for future behaviour” were formulated clearer. Also, the images in the message intervention were tested for comprehension, clarity and some of them adjusted. Moreover, before launching the survey, a technical test that aimed to detect errors in the coding of the survey was conducted.

3.5 Reliability and Validity

The reliability of the study was estimated by testing internal consistency of the survey sections. Interconnectedness of the statements in ‘current PEB’ (section two) and ‘intentions for future behaviour’ (section five) as suggest Table 4. was estimated by calculating average inter-item correlation of connected statements, e.g. ‘buying second hand products’ (PEB_7) and ‘I am to buy second hand products’ (IFB_7). The result of the inter-item correlation is mentioned in Appendix C. The internal consistency of value statements (section three) of E-PVQ was estimated by computing Cronbach’s alpha coefficient as discussed in subparagraph 4.1.3). The results from these survey sections are considered replicable. The internal consistency of message intervention (section four) can be estimated by correlation with the individual goal-frames (section two) as depicts Table 11.

In order to increase the content validity of the survey, the statements in sections ‘current PEB’ (section two) and ‘intentions for future behaviour (section five) were based on the recently published studies presented in Table 1. Value assessment (section three) was based on the validated questionnaire adapted for environmental research, E-PVQ (discussed in paragraph 3.4). However, the message intervention might minimize content validity as the experimental part was created by the authors and entailed some challenges, particularly with the consistency of the Instagram posts.

To increase the construct validity of the study, the homogeneity of different groups was assessed. The comparison of the experiment and control groups as well as respondents with and without Instagram account was discussed in subparagraph 4.1.1. Moreover, Heale and Tqycross (2015) suggest theory