Colorism in Zanzibar

A

Qualitative Field Study on The Effects of Colorism on

Women’s Identity and Ethnicity Construction

Feven Tekie

Department of Global Political Studies

International Migration and Ethnic Relations (IMER) Two-Year Master’s Thesis, 30 Credits, January 2020 Supervisor: Margareta Popoola

ii

Abstract

This paper is a by-product of a minor field study conducted in Zanzibar, Tanzania during eight consecutive weeks in early 2019. The purpose of the study was to examine how colorism affects women’s identity and ethnicity construction through the research questions; how do women in Zanzibar experience colorism in their daily lives and; how does colorism affect their self-perception? The data was collected through seven semi-structured interviews with women in Zanzibar and observations. The concepts of identity and ethnicity saturated the study and the identity process theory (IPT) was used as a theoretical framework to analyze the inquiry. The findings suggest that colorist ideals were dominant in society as light and medium colors were more valued than dark. This was demonstrated by associating light and medium skin color, as well as relaxed and straight hair to “good” and “beautiful”. However, colorism proved to impact women in their daily lives to various degrees. Informants who grew up on the mainland admitted to being more affected and expressed feelings of unworthiness or praise, depending on skin color. Whereas women born and raised on Zanzibar, felt colorism affected their lives minimally, but nevertheless acknowledged the existing problems for many women of e.g. skin bleaching. According to the IPT, a strong sense of distinctiveness from mainlanders, a continuity in past and present identity and a high self-efficacy seemed to guard self-esteem against existing colorist ideals. Furthermore, inclusion to the Zanzibari ethnic identity proved not to be affected by colorism, as color was not a prerequisite factor to ethnicity but rather, shared land, religion, and history. Keywords: Colorism, Zanzibar, Tanzania, Identity, Ethnicity, Skin Color Bias, Internalized Racism, Identity Process Theory

iii

Acknowledgements

There are many people involved in this journey whom I would like to thank. To begin with, I am forever grateful to the Swedish International Development and Cooperation Agency (SIDA) and Malmö University for granting me this Minor Field Study (MFS) scholarship. Without it, this research project would not have been feasible. To all the women I interviewed who so kindly devoted me their time, and the staff at The State University of Zanzibar who helped me in all my endeavors, I would like to give the biggest ‘thank you’. I also want to show gratitude to all of the people I have met along the way who has sent me articles, raised my awareness and enriched me with knowledge on colorism. Your help and insights have been irreplaceable. To my supervisor, Margareta Popoola, thank you for the many interesting conversations that have flourished, your guidance and your devotion.

iv

Table of Contents

1. INTRODUCTION ... 1

AIM AND RESEARCH QUESTIONS ... 1

DELIMITATIONS ... 2

CLARIFICATIONS ... 2

STRUCTURE OF THE THESIS ... 3

2. CONTEXTUAL BACKGROUND ... 4

CONCEPTUALIZING COLORISM ... 4

RESEARCH LOCATION:ZANZIBAR ... 6

3. LITERATURE REVIEW ... 8

MAIN FINDINGS ... 8

RESEARCH GAP AND CONTRIBUTION ... 12

4. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK ... 13

IDENTITY PROCESS THEORY ... 13

IDENTITY ... 15

ETHNICITY AND ETHNIC IDENTIFICATION ... 15

5. METHODOLOGY ... 17 PHILOSOPHICAL POSITION ... 17 RESEARCH DESIGN ... 17 INTERVIEWS ... 18 OBSERVATIONS ... 20 DATA ANALYSIS ... 21

VALIDITY AND RELIABILITY ... 22

RESEARCHER POSITIONALITY ... 23

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS ... 24

6. FINDINGS ... 25

7. DISCUSSION ... 43

COLORISM AS A THREAT ... 43

COLORISM’S EFFECTS ON THE ‘SELF’ ... 44

COPING METHODS ... 50

8. CONCLUSION ... 53

CONCLUDING REMARKS ... 53

SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER RESEARCH ... 54

9. REFERENCE LIST ... 55

APPENDIX I ... 62

APPENDIX II ... 68

1

1. Introduction

Some scholars have argued that colorism is one of the decade’s most intense manifestations of ‘racial’ inequality (Burton, 2010: 443). As a global phenomenon that has persisted over centuries, expressions of colorism can today be seen worldwide among various cultures and nations. From booming skin bleaching industries in Asia, Africa, and the Caribbean, to the entertainment industry in the US and small-scale households globally. In countries throughout Africa, such as Nigeria and Zambia, statistics show that over half of the female population use skin bleaching products (Blay, 2011: 5; World Health Organization). American actress Zendaya expressed that she held a privilege by being light-skinned in American popular culture and stated “I am Hollywood’s, I guess you could say, acceptable version of a Black girl, and that has to change (Danielle, 2018). When winning ‘Miss Algeria 2019’, Khadija Ben Hamou, endured massive racist criticism, including from Algerians, for her facial features and being ‘too dark’ (BBC, 2019b; Morocco World News, 2019). Kenyan Oscar-winning actress, Lupita Nyong’o, shared that her experiences of colorism brought her to feeling unworthy as a child, because of her darker skin color (BBC, 2019a).

After dissecting a lack of existing academic research of the effects on identity construction, as a consequence of the above-mentioned acts of internalized racism, the idea for this study came into effect. This master’s thesis was partially conducted in Zanzibar, Tanzania where the data collection took place in early 2019. Although more known for its’ turquoise waters, paradise beaches and as the birthplace of Freddie Mercury, Zanzibar holds a rich history with inhabitants originating from various corners of the world. As a former colony and slave-trade hub in the region, colorism in Zanzibar becomes particularly significant to study, as colorist ideas relate strongly to both colonization and slavery (Haywood, 2017: 762).

Aim and Research Questions

The research paper aims to explore how colorism is experienced by women in Zanzibar and how it affects their identity and ethnicity construction. To achieve this aim, the following research questions will guide the inquiry; how do women in Zanzibar experience colorism in their daily lives and; how does colorism affect their self-perception? To answer these questions, semi-structured interviews were conducted

2 with seven women in Zanzibar and observations were done as a complementary method with the scope of giving an overall perspective of how colorism manifests itself in Zanzibar.

Delimitations

To narrow down the scope of this study, while considering the shortage of time, some delimitations had to be made. Firstly, this paper only focused on the experiences of women and not men. Even though men are also affected by colorism, women have been shown to be more affected (Chen et al., 2018: 257; Hunter, 2016: 55). Secondly, due to convenience when sampling, all the informants had some kind of academic background, were young, spoke English fairly well and lived in the capital Stone Town or the outskirts. Therefore, this might affect the results of the research as their experiences of colorism and opinions might differ from other Zanzibari women with diverse backgrounds. Thirdly, as studies of colorism can be of importance in many nations and cultures, the interviews all took place in Zanzibar and the choice of location will be described in Research Location: Zanzibar. Therefore, the study can only account for some women’s experiences on this particular island, which limits its’ generalizability.

Clarifications

Black – Many of the people in Zanzibar used the word ‘Black’ to describe a person with dark skin color (concerning people and the context in Zanzibar). Therefore, the word Black will not be applied in terms of ‘race’ as it is usually in American discourse to describe African Americans or persons of African descent.

Mzungu – Referring to a person who is a foreigner (Swahili direct translation: wanderer) to the land. Most of the time, this implies the person being White.

Skin color – A way to refer to a person’s skin color. Whilst skin tone and skin complexion also can imply the color of one’s skin, they can also refer to other elements of a person’s appearance such as skin texture or cool/warm skin tones. This way of referring to one’s skin color is also exempt from any racial connotations and color-based race labels (Chen et al., 2018: 256).

3 Swahili people – A common way for people in Zanzibar with African origin to refer to themselves.

Tanzania – Zanzibar works as a semi-autonomous state within the country of Tanzania and when Tanzania or Mainland is written in this text, reference is to the mainland. White – Frequently, many of the informants stated the word to describe a Zanzibari/Tanzanian with lighter skin color. On a few occasions, the word was used to describe a foreigner, e.g. European who is White. To ensure clarity, the word will refer to the first meaning of a Zanzibari or Tanzanian person with lighter (brown/lighter brown) skin color.

Zanzibari – inhabitants of Zanzibar who claim to be Zanzibaris. This does not include non-residents, foreigners who stay here for shorter periods or Tanzanians who identify as mainlanders.

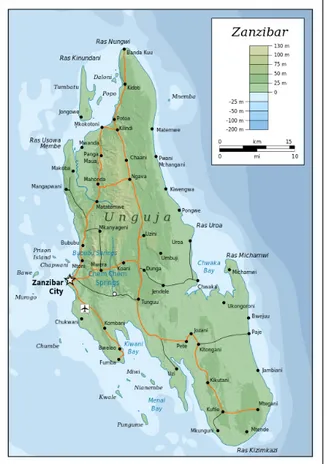

Zanzibar – When referring to Zanzibar in this paper, the island of Pemba or other small surrounding islands, are not taken into consideration as the study has not been conducted there. Unguja is the most known island to refer to as Zanzibar. Besides, when simply stating “the island” throughout the text, the reference is to the island of Unguja (view: Figure 1 and Figure 2 in Appendix I).

Structure of the Thesis

This paper is structured into eight chapters. In Chapter 1 the scope of the research has been introduced to the reader. Chapter 2 will provide a brief contextual background to the topic of colorism and also the cultural context in which this field study was conducted. In Chapter 3 a literature review will follow that lists some of the previous findings related to the research topic. Chapter 4 will outline the theoretical framework and in Chapter 5 the methodology will be described more in-depth. Following in Chapter 6, the findings of the interviews and observations will unfold. In Chapter 7 a discussion of the findings in relation to the literature review and theoretical framework will take place. Finally, Chapter 8 will conclude with responding to the research aim and also propose some suggestions for further research in the field.

4

2. Contextual Background

This chapter sets out to familiarize the reader with colorism, through both a present and a historical perspective. To get an insight into the country and culture in which this study was carried out, a brief introduction to Zanzibar is presented as well as the motivations behind selecting this place as the research location.

”Colorism is born of racism. It is the daughter of racism”. - Lupita Nyong’o (BBC, 2019a). Conceptualizing Colorism

The term ‘colorism’ was first coined by Alice Walker in 1983, where she stated that it was; “prejudicial or preferential treatment of same-race people based solely on their color” (Walker, 1983: 290). In some contexts, colorism can also be referred to as shadism, skin tone bias, color complex or pigmentocracy (Gabriel, 2007: 5). It stands for both the privilege and discrimination a person experiences depending on the degree of lightness in a person’s skin color. The prejudice, perceptions of beauty and stereotyping occur both within and between ‘racial’ groups (ibid; Hochschild and Weaver, 2007: 646). Margaret Hunter, one of the most eminent scholars within the academic field of colorism, defines colorism as; “a process that privileges light-skinned people of color over dark in areas such as income, education, housing, and the marriage market”, and thus affecting more than just beauty standards, as colorism is commonly associated to (2007: 237). The skin-color bias, although a form of racism common in many fields and institutions, does not necessarily coincide with individuals being racist per se, as it oftentimes in unconscious (Hunter, 2016: 55).

Even though the term is fairly new, the ideology of colorism and the practices are not (Jones, 2000: 1489). Whilst some argue that colorism evolved through Europeans giving preferential treatment to individuals and groups in places like Africa, Asia and Latin America who had more Eurocentric physical appearances (Keith and Monroe, 2016: 8), others have found that colorist practices were occurring before ages of colonization. For instance, in ancient Egypt, the intermixing of Africans and Asians led to the darkest Egyptians being pushed down the social ladder and the mixed gaining social, political and economic control (Gabriel, 2007: 9). Dahan Kalev stated that the

5 discourse about colorism in Israel started in 1882 with the birth of the Zionist movement and that globally, the desire to have lighter skin can be traced back to ancient times (2018: 2102-2103). Hyein was also of that idea and underlined that people in Korea would apply rice powder on their skin to lighten it before any contact with the ‘western world’ (2016: 45).

During the sixteenth century, the English had already asserted negative connotations to the word “black”. It was seen as dirty, evil, deadly, devilish and ugly, while its’ opposite, “white” was equated to be beautiful, good, godly and clean. (Gabriel, 2007: 6). Christian and Manichean ideologies have been endorsing an idea of dualism that many claim to have influenced the institution of colorism. By depicting Christ as White and associating whiteness to godliness, good, and “the light”, blackness has in contrast been representative of the dark, evil and immoral (Blay, 2011: 8). The Manichean ideology was also held by philosophers such as Descartes, Hume, and Kant, who all became notable devotees of this philosophical standpoint (ibid: 9). According to Blay, the biggest impact the Manichean ideology had, was on the construction of identities making White the superior one and Black inferior (ibid: 10). In many languages today, sayings such as “white Christmas”, “white lie”, “blackmail” and “black market” are all influenced by the Manichean worldview (ibid).

However, most of the scholars today argue that modern-day colorism stems from slavery and European colonization (Haywood, 2017: 762). In the age of slavery in the US, lighter-skinned slaves, who often were the result of slave-owners raping enslaved women, would be treated better and become house slaves whilst their darker-skinned counterparts, would be forced to the fields. Also, for a slave owner to buy a lighter-skinned black female with long hair and white phenotypical features, entailed a higher social status for the slaveholder (Jordan, 2018: 250; Gasman and Abiola, 2016: 40-41). Perpetual degradation of black bodies and white supremacy have been key drivers of linking lightness to something desirable (Keith and Monroe, 2016: 5). Although, the divide between lighter and darker-skinned Blacks did not only show through the White slave owners. It also manifested itself within Black communities through marriage preferences, blue vein societies and fraternal organizations where the brown paper bag was used to distinguish those of lighter (ibid: 41).

6 In Latin America, conquest and colonization resulted in a large population mixed with European, African and Indigenous ancestry (Keith and Monroe, 2016: 7). The term “mejorar la raza” is common and refers to marrying someone White to increase or better one’s racial status (Haywood, 2017: 762). Colonialists in the Americas not only enforced the thought of a particular language, religion and culture as being superior, but they also brought ideas of bodily aesthetics that they viewed as superior, such as blonde hair, pale skin, and blue eyes. This eventually led to the colonized internalizing the dominant ideology of the Europeans (Hunter, 2016: 55). Many of Afro-Latinos today tend to have to explain that they are both Latino and Black due to the historical narrative that constructed Latino as being distant from being Black (Haywood, 2017: 765).

Research Location: Zanzibar

In 1963, the islands in the Zanzibar archipelago gained its’ independence, to then one year later, merge with the mainland of Tanganyika and form what we now know as the United Republic of Tanzania. Today, Zanzibar has a population of 1, 3 million spread mainly in the bigger islands of Unguja and Pemba and works as a semi-autonomous region of Tanzania with its’ government and parliament (Globalis, 2018; World Population Review, 2019). The capital of Zanzibar is Zanzibar City, which is located in Unguja with its’ historical center and World Heritage Site, Stone Town (Tanzania Tourist Board). Contrary to the mainland, the inhabitants of Zanzibar (99%) and coastal Tanzania mostly adhere to Islam. The official languages of Zanzibar are Swahili and English but Arabic also has a stronghold in the society (Globalis, 2018). The island was long known as ‘the spice island’ and in particular, the island became the largest clove exporter in the world. Nevertheless, today the spice trade has seen a decline and the island is more known for its’ tourism and ‘paradise beaches’ (Aljazeera, 2016). The tourism industry today stands for a major income source in Zanzibar and is the largest source of foreign exchange in Zanzibar (World Bank, 2019: 14).

The people said to have settled first on Zanzibar were Bantu-speaking Africans. For 200 years it was ruled by the Portuguese to then be dominated by Omanis in the 17th century. In 1832, the Sultan of Oman moved the capital from Muscat to Zanzibar, which by that time was a key slave-trading center (Aljazeera, 2016). People were brought in as slaves mainly from the Democratic Republic of Congo and what today

7 consists of mainland Tanzania. They were auctioned off to countries in Asia such as Persia, India and Arab countries (Tanzania UNESCO, 2006). The slave-trade on Zanzibar was one of the world’s last slave markets and was run by Arab traders until the’ abolishment (Smith, 2010). Even after it’s’ abolishment in 1873 by the British, it secretly continued for years (Tanzania UNESCO, 2006). The Omani rule, Asian merchants and traders who accompanied the Omanis in their endeavors with slave auctions, simultaneously created a hierarchical system where the Arabs were considered superior to the Africans. Consequently, proximity to Arab ancestry became sought-after. Following, the Pan-Africanist movement, anti-colonialism and Revolution in 1964 emerged, sparking what we now know as Zanzibari identity (Keshodkar, 2013: 3-4). The language of Swahili and the religion of Islam emerged as markers for the united Zanzibari identity (Keshodkar, 2013: 5,26).

Zanzibar was the selected location for numerous reasons. The island has a rich history and since the early 1st century, Zanzibar served as a gateway for Arab, British, European, Indian and Persian tradesmen (Revolutionary Government of Zanzibar). This influx of people from all corners of the world, together with the massive slave-trade on the island, contributed to Zanzibar becoming a multi-ethnic melting pot (Chiteji et al.). When studying colorism, this was seen as an advantage as it could allow access to different people’s experiences with the implications of their skin color. Additionally, as colorism is linked to colonization, it seemed relevant and appropriate to conduct the study in a historical place that experienced decades of colonialism like Zanzibar.

However, Zanzibar is not only of interest when studying ‘ethnic’ and ‘racial’ issues from a historical lens but also from a modern-day perspective as immigration to the island, especially from the mainland and countries both in Africa and the ‘Western hemisphere’, is grand. Also, the major tourism-boom that the island has experienced in the past 20 years has led to the presence of a lot of white and light-skinned people on the island. This was also viewed as valuable to the study because it allows for having a frame of reference when discussing whiteness. Zanzibar was also optimal as a research location due to practical reasons. The island has a lot of interactions with tourists and is therefore accustomed to foreigners and many also speak English fairly well.

8

3. Literature Review

Although significant studies relating colorism to identity and ethnicity construction are scarce, this chapter seeks to dissect the main findings within the study of colorism and themes connected to it such as skin color bias, whiteness, skin bleaching, and ethnic identification.

Main Findings

An abundance of the existing research produced in the US, show that African Americans, Asians and Latinx in the US with lighter colors do comparably well to their ethnic-racial group (Keith and Monroe, 2016: 4; Vasquez, 2011: 439-440). On the contrary, people of darker skin are negatively affected both in educational outcomes, wages, finding an occupation and romantic options (Gabriel, 2007: 1; Keith and Monroe, 2016: 5). Hunter found in her study of colorism and education, that students of color felt the effects of white racism among their race and community, even if there was no presence of white students (2016: 57). Even though much of the research suggests that people of darker skin are more affected, Hunter found that lighter-skinned persons can be disadvantaged when it comes to ethnic legitimacy. Darker skin tones are in many ethnic communities perceived as being more ethnically authentic and as a consequence, many lighter-skinned and biracial can feel abandoned or left out of their co-ethnic groups (2007: 244).

The concept of social capital indicates that people can possess social advantages, transmitted by generations. Coleman, a prominent theorist within this paradigm argued that if the capital is not renewed, it risks being extinct (Cherti, 2008: 32-38). Many studies on colorism have been geared towards studying its’ connection to marriage homogamy, in this context; that similar color is a determinant when choosing a partner. According to Reece (2018: 19) and Bodenhorn (2006: 256, 259), this can be explained by the fact that marriage acts as a mechanism for transmitting certain social advantages. Light skin color then, just as economic or financial capital, acts as capital according to Dahan Kalev (2018: 2102) and Margaret Hunter (2016: 57). Using bleaching creams and getting cosmetic surgery can thus be seen as a way of acquiring racial capital (Hunter, 2016: 57). Hence, during the times of slavery in the US, lighter-skinned

9 parents could pass on educational advantages generationally due to the advantages held as house slaves, such as literacy (Gasman and Abiola, 2016: 41).

Characteristics such as the width of the nose, the fullness of the lips and the texture of hair and in particular, skin color, have been used as mechanisms to designate people into different racial groups (Jones, 2000:1493-1494). Although skin color has played a huge part in the categorization of people into different racial groups in the US, it has not been the sole determinant. If, for example, a person who appears to be White, have ancestors that are Black, that peculiarity becomes a criterion to be categorized in the ‘Black’ category. Here, ancestry becomes the primary characteristic rather than appearance (ibid: 1495-1496). In the American context, this can be explained by ‘the one-drop rule’ which was a way for White people to assign people to the ‘Black category’ if they had a “drop of Black ancestry”. The system of slavery was built on the assumption that White was the superior race and therefore they could not become slaves. The drop-rule then justified the enslavement of ‘multi-racial’ slaves and hence, the emergence of the one-drop rule (Jordan, 2018: 250; Khanna, 2018: 96-98).

White supremacy is characterized by a system of maintenance and ideology. As such, it is maintained by many Whites, but not only, as many non-whites also unknowingly or purposely adheres to and practices the ideology. White supremacy is viewed to be upheld by e.g. colorist thoughts and practices. Even though people who bleach their skin don’t necessarily want to become or strive for absolute whiteness, they are striving to access a privilege that has throughout history been awarded those who approximate whiteness the most and therefore endorsing the superiority of whiteness (Blay, 2011: 7-8). The practice of bleaching one’s skin, therefore, becomes a way of empowering oneself and approximating a white ideal (ibid: 37). Blay explains that skin bleaching and other forms of altering one’s appearance such as straightening hair and undergoing surgery to obtain aquiline features is an attempt to reach the white ideal and consequently, get access to a social status that throughout history have been reserved for Whites (ibid: 4). Renowned psychiatrist and philosopher Frantz Fanon also asserted this when stating that women in Martinique were keen on marrying into whiteness or the seemingly least Black man, in an attempt of ‘moving up’ the social ladder 1952: 33).

10 Vasquez stated that “the perceptions of people of color about themselves and others with colorism is a powerful mitigating factor in the development of racial/ethnic identity, acculturation, language identity, and its impact on the perceptions of gender throughout these processes” (2014: 440). On the same note, Chen et al. stated that values and culture-based meaning put on skin color, could influence an individual’s self-evaluation, perception of one’s body image and attitude (2018: 256; Vasquez, 2011: 439). Jacobs et al. argue that the usage of skin bleaching creams can partially stem from a deeply rooted emotional and cognitive evaluation of one’s worth, in other words, self-esteem (2016: 69). In a study done in Tanzania, the women who used products with skin whitening agents, among many motives claimed they wanted to be more beautiful, remove pimples and rashes, look more European and attract the opposite sex (Blay, 2011: 22). In South Africa, the legacy of apartheid along with western beauty standards creates the desire to lighten the skin to overcome color stigma but also institutional forms of discrimination (Jacobs et al., 2016: 67).

According to medical experts, skin bleaching is “one of the most common forms of harmful body modification practices” (Jacobs et al., 2016: 67). Yet, the skin bleaching industry is thriving and the number of people using skin lightening products is increasing rapidly. Many of the scholars interested in colorism and how it manifests itself have been geared towards studying the practice of skin bleaching (Blay, 2011: 5). In India, the fairness cosmetics industry is estimated to be worth about US$180 million (Nagar, 2018: 1). Estimates also show that 35 % of South African women have used or are using skin lightening products. In Bamako, Mali the number is 25 %, in Dakar, Senegal 27% and in Lagos, Nigeria, 77% (World Health Organization). In the Ivory Coast, the estimates show that 80 % of women who are seemingly fair in their color use skin lightening products regularly. In Ghana, more than 30% of the population, both male and female, are reportedly using bleaching creams regularly. In Zambia, 60% of all women are estimated to use products with skin lightening components (Blay, 2011: 5). The World Health Organization estimated that 40 % of women in China, the Philippines, Korea, and Malaysia have in some period of their life used skin lightening products (Hyein, 2016: 45). Most of the skin lightening products are produced in European and Asian countries and exported to Africa and other places in the world. Blay states that this is yet another exemplification that Black bodies are being exploited whilst upholding the ideal of whiteness in the world. Meanwhile, the White body is

11 being exempt and protected from the harmful practice, as skin lightening products were banned in Europe after the reign of Elizabeth I when it was discovered to be affecting people’s health as early as 1724 (2011: 24-25).

However, colorism, as mentioned previously, does not only manifest itself in the desire to have lighter skin. It also entails the wish to have more “Caucasian features”. Statistics show that in Korea, one of five women have undergone some plastic surgery to achieve more “White features” (Hyein, 2016: 45). Snell explains that these measures are not taken to ‘pass’ for White, but rather appearing more approachable to a larger White populous (2017: 206). Reece also highlighted that colorism is not necessarily the desire to become White, but more so of approaching whiteness by stating that colorism is “the process by which people of color are awarded advantages based on their phenotypical proximity to whiteness” (2018: 5).

In the 1920’s the trend of fair skin and white-powdered faces became outdated. This due to the discovery of benefits of vitamin D generated by the sun, a changed mindset that no longer viewed fairer skin and indoor work as a token of social class and famous people like Coco Chanel proclaiming the golden tan as a ‘chic look’ (Chen et al., 2018: 256). Some claim that the current and future sought-after color, by Whites and non-Whites alike, seem to be a middle-way color; ‘beige’ (Snell, 2017: 205). Even though there seems to be a preference for lighter or ‘beige’ skin colors around the world, there is no evidence in science that confirms that specific skin colors are traits humans are attracted to biologically (Currie and Little, 2009: 409). However, numerous scientific evidence links attractiveness to traits such as symmetry in the face, volume-to-height index and waist-to-hip ratio. The latter ones have been some of the biggest indicators of attraction when humans choose a female partner. Reasons for this being that they signal female reproductive health such as fertility, for the opposite sex (ibid: 410; Dural et al., 2015: 232-233).

12 Research Gap and Contribution

After reviewing the previous literature on colorism, it appears that most of the existing research has been conducted in the US. As a result, the academic contribution has mainly emphasized the implications of colorism and its’ correlation to ‘race’, in various intersectional ways. Many scholars have in particular investigated the outcomes of darker-skinned vs. lighter-skinned people within various racial groups in the marriage market, education, and incarceration. Much of the research has also addressed the beauty industry and the excessive usage of bleaching products in various countries around the world. However, little has been researched on the effects of colorism on people’s identity and/or ethnicity construction. Beyond this, the little research on colorism that has been produced in African countries has largely been centered on post-apartheid South Africa.

The contribution this research project aims to make is threefold. Firstly, this thesis aims to fill the research gap within the academic field of colorism by bringing light to effects on identity formation and bringing perspectives from an East-African country. Secondly, as colorism relates significantly to the concepts of identity and ethnicity, the study hopes to contribute to the ER part of the master’s program, IMER (International Migration and Ethnic Relations). Thirdly, upon request, this paper will also be shared with the Ministry of Culture in Zanzibar, who confirmed that a similar study has not been done in Zanzibar prior to this. For this reason, another aim is that the humble findings of this study, hopefully, can spark interesting discussions amongst people and authorities in Zanzibar.

13

4. Theoretical Framework

“What is this thing – this identity – which people are supposed to carry around with them?” - (Billig, 1995: 7). In order for the study not to lack precision, a key step in the initial stages becomes to thoroughly conceptualize the terms that will saturate the study (6 and Bellamy, 2012: 131). This chapter will, therefore, explain how the identity process theory, identity, and ethnicity are intended to be used in this paper. The main theory will first be introduced and then followed by definitions of the concepts that constitute the aim of this study. Identity Process Theory

The identity process theory (hereinafter: IPT) was developed by Glynis Breakwell in 1986 with the intention to “achieve a better understanding of how people seek to cope with experiences that they find threatening to their identity” (Breakwell, 2014: 21). Later, the theory has been used to assess four identity principles: distinctiveness, continuity, self-esteem and self-efficacy and how the motive of protecting these principles shape the identity structure (Vignoles et al., 2006: 308). IPT argues that self-identity should be viewed in terms of two universal processes; assimilation-accommodation and evaluation. The first process treats the handling of new information to the identity structure, whilst the latter one refers to the value that gets put on the contents of identity (Jaspal, 2013: 4).

14 Distinctiveness (1) entails the need to preserve personal distinctiveness and uniqueness. In research regarding settlement and community identity, this principle has been seen to associate to distinctiveness in terms of lifestyle and connection to one’s land and environment. Breakwell suggests that the preservation of one’s self-concept throughout time and situation depends largely on continuity (2). This means that past and present

definitions of self are not jeopardized by threats to the self. Self-esteem (3) refers to a

person’s positive evaluation of its and its group identity’s worth and social value. This has been regarded as a central part of the ‘self’ (Twigger-Ross and Uzzell, 1996: 207-208). On the other hand, self-efficacy (4) is a later added principle that entails the

individual maintaining and enhancing feelings of control and confidence in their capabilities (Vignoles et al., 2006: 309). This principle relates highly to personal agency (Twigger-Ross and Uzzell, 1996: 207-208).

The perception of what a threat is can be explained in terms of the very coping processes set to deal with these threats. They are only significant in social contexts as they, and the coping methods need to be understood through dominant beliefs and expectations in the society (Breakwell, 1986: 7, 49). Breakwell reinforces that “the individual learns their social worth through interaction in the context of dominant ideologies” (ibid: 98). However, she also highlights the differences between a threat to a sudden change as e.g. being fired, to being in a state of threatening position due to unemployment (ibid: 75-77). Nevertheless, if the principles are threatened, the person will use strategies to cope with the posed threat (Jaspal, 2013: 5).

But then, what constitutes a coping method? Breakwell states: “any thought or action which succeeds in eliminating or ameliorating threat can be considered as a coping strategy, whether it is consciously recognized as intentional or not” (1986: 79). She argues that although a person might not admit or be aware of using a coping method, the observer may dissect a threatening position and the used coping methods. For instance, if denial is the used coping method of an individual, this person will not claim that a denial strategy is being implemented to cope with the threat (ibid). The coping strategies can be manifested at three levels; intrapsychic deals with cognition, values, and emotions such as denial or salience. Interpersonal focuses on action and negotiation with other people and intergroup describe group strategies such as self-help groups or social movements (Jaspal, 2013: 5; Breakwell, 1986: 77-105).

15 Identity

Even though most people seem to have a clear understanding of what identity is, a precise definition can be troublesome to pin down (Lawler, 2014: 1). The word ‘identity’ and ‘identical’ stems from the Latin word idem, meaning ‘same’. This then presupposes that humans have a ‘shared identity’ by simply being humans and other categorizations based on gender, nationality, etc. Simultaneously, there is also an aspect of identity that suggests a difference from others and argues for uniqueness (Lawler, 2014: 10). Two influential people on studies of identity, Barth and Tajfel, both described identity and identification as a process. While Barth regarded identification as a by-product due to an individual’s interests, Tajfel argued that identification was based on group membership that generates different behavior in favoritism and discrimination, based on membership (Jenkins, 2008: 7).

Sociologist Richard Jenkins defines the essential meaning of identity as knowing “who is who” and thus also, what is what (2008: 5). This then implies us knowing who we ourselves are, who others are and others knowing who we are. His understanding of identity is that it is characterized by relationships based on similarity and/or difference, which individuals and collectivities have with other individuals and collectivities (Jenkins, 2008: 17-19). He also makes a distinction between collective identity and individual identity, stating that the two are separate phenomena. The collective identity he describes as emphasizing similarity whilst individual identity emphasize difference (ibid: 37-38). Identification makes sense because of interactions and relationships with other people, and because of this, hierarchies exist socially and interactionally. Because of these relationships, hierarchies of scales of preference, ambivalence, competition, hostility and, partnership occur (ibid: 5-6). This study will apply Jenkins understanding of identity.

Ethnicity and Ethnic Identification

The word ‘ethnicity’ derives from the Greek word ethnos which today, many refer to as ‘people’ or ‘nation’ (Jenkins, 1997: 10). In its’ essence, ethnicity can be described as a question of ‘peoplehood’ (ibid). Baumann argued that the term ‘ethnic’ could be distinguished in two separate ways (1996: 17). The first one is connected to ‘race’ or ‘descent’, i.e. biologic criteria. The departing point of this paper, Baumann, as well as many other social scientists, neglects this biological argument and rather view these

16 criteria as social constructs (ibid: 17-18; Jaspal and Cinnirella, 2011: 508). The second one, which will be applied in this study, is judgment that ethnic division simply arises and develop from collectives feeling a sense of distinctiveness from other groups (Baumann, 1996: 18). ‘Ethnicity’, as a social construction, derived from Weber and Barth who defined ethnicity as “a subset of people whose members share common national, ancestral, cultural, immigration or religious characteristics that distinguish them from other groups” (Burton, 2010: 440-445).

Stemming from the workings of Durkheim and Mauss, the study of classification has been of pivotal relevance in anthropology. The central idea is that humans are classifying beings by nature, who create classes of different phenomena to make symbolic orders, often power asymmetries (Eriksen, 1993: 72). Jaspal and Cinnirella argued that a prerequisite for ethnic identity construction is for it to be validated by ‘genealogical facts’. They can be either common cultural characteristics, religion, language or physical similarities. While ethnic can entail belonging and togetherness, it is also a way to differentiate people from other groups depending on e.g. kinship, race, culture, religion, and customs. The sense of distinctiveness can lead to the in-group perceiving themselves as distinct from the out-in-group, in a positive way (2011: 504, 508-510). Hence, ethnicity in itself always indicates a collective identification. Group identities thus evolve through a mutual contact, by people who view themselves as being diverse from members of other groups (Eriksen, 1993: 1, 15-16). As membership in a social community or identity exists in relation to others, it is also exclusive, therefore not everyone can take part (Eriksen, 1993: 73-74). These ethnic boundaries are drawn depending on context and various criterions (Baumann, 1996: 18). Jenkins argues that ethnic identification can be regarded in the light of both individual and collective. Individual in the sense that it internalizes in self-identification and collective as it is externalized in various interactions with others as well as categorization (1997: 14).

17

5. Methodology

In this chapter, the methodological approach of the study will be presented in various sub-chapters. After declaring the philosophical stands upon which this study rests on, the research design and data collection will be presented. Following that, discussions will prevail on validity, reliability, ethics and researcher positionality.

“Reality is socially defined. But the definitions are always embodied, that is, concrete individuals and groups of individuals serve as definers of reality”

- (Berger and Luckmann in Guess, 2006: 656). Philosophical Position

In the social sciences, the outcome of the study can vary tremendously depending on which philosophical stand the researcher has, and because of this, it is important if not crucial, to declare one’s philosophical position (Rosenberg. 2012: 3). This paper departs from a constructivist point of view that sees societies as social constructions maintained by individuals and their actions. Social institutions and norms, contrary to natural phenomena, therefore exist as social constructs because of human beliefs and desires (ibid: 130-133). Therefore, when ‘race’, ‘ethnicity’ or ‘skin color bias’ appears in this paper, it is not discussed from an essentialist perspective but rather as useful tools to discuss social constructions that have been formed and upheld by humans. This ontological position sees that social actors not only produce phenomena and certain categories but that these are constantly changing, which means that the results are not definitive (Bryman, 2016: 29). In this paper, human action will outline the criterion for producing meaning, i.e. an interpretivism approach will be applied where the experiences of the informants form what is epistemologically true (Hill Collins, 2000: 258; Bryman, 2016: 26).

Research Design

The nature of this research will lean towards an inductive approach rather than a deductive approach even if it can be difficult to strictly use one of the approaches as they often overlap (6 and Perri, 2012: 76). The usage of an inductive approach is favorable over a deductive approach when there is a scarce range in previous research in the field (ibid: 77), as is the case in this study. Additionally, qualitative research, which focuses on words rather than quantification, tend to use an inductive approach

18 in the structure between theory and research (Bryman, 2016: 33). The theoretical framework has therefore been applied to analyze the data and not act as a template to form the interview guide or direct the nature of the interviews.

Interviews

Severn semi-structured interviews were the primary source of data collection. These interviews rest on an ontological stand where people’s experiences and interpretations are some of the main focuses (Lewis-Beck et al., 2004: 1021). The method was chosen because the open and interactive nature of the interview is designed to generate the participant’s perspectives, understandings, and experiences, as was the motive of this study. The usage of semi-structured interviews also allows the researcher to discover events and meanings important to the participants, that were not anticipated in the early stages. For instance, the interviews came to focus a lot on the practice of skin-bleaching and outside influences from the mainland, which was not intended but later turned out to be relatable and comprehensible topics in the context. Nonetheless, the same questions in the interview guide (view: Appendix II) was formulated to all of the informants in the same manner to avoid different interpretations of the questions and the risk of expanding too much on themes that are not relevant for the aim (Bryman, 2008: 202; Lewis-Beck et al., 2004: 1021). Furthermore, when outlining the interview questions, Coyle and Murtagh highlights the problematics of asking direct questions when assessing e.g. confidence, as this remains someone’s subjective evaluation (2014: 43-47). In this context, questions such as “how did colorism affect your self-esteem during your childhood” were avoided and instead, general questions were posed with follow-up questions such as “how did that make you feel” or “how did you handle those situations?”.

Selection Criteria

As this study wants to explore experiences of colorism by different women, a variation of skin colors among the participants would have been to prefer. Although, due to difficulty in measuring skin color (as ethical complications), this was not chosen as a criterion. Some earlier studies used the ranges of very light, light, medium, medium-dark, and dark to categorize skin color and during the interviews, all of the informants were asked where they felt they fit in. Furthermore, the motive was to understand the ordinary woman’s experiences with colorism in Zanzibar, and therefore was no

19 particular target group within the category of ‘women’ when sampling. However, it was of importance that they had Tanzanian or Zanzibari roots and some type of relation to Zanzibar to understand and have a conversation about the location. In the end, seven interviews were conducted with women from the ages of 23-33 who considered themselves to range between light, medium and medium-dark. Two of the women were born in Unguja, two in Pemba and three of the women were born on the mainland. All of the informants were residents of Zanzibar except for one who lived on the mainland but due to work spent a lot of time in Zanzibar.

Sampling Process

Doing the interviews in the last weeks allowed for getting to know the culture more, expanding my network and learning some Swahili. Through my network, a staff member at The State University of Zanzibar (hereinafter: SUZA) spread information forward to some classes about my study and four women showed their interest in participating. One of the informants I met in a restaurant, another informant I met when she was traveling for leisure and another I met in the reception at SUZA. Thus, a convenience sampling was employed, meaning what is most accessible to the researcher by virtue. This way of sampling can become problematic for the generalizability because it rarely exemplifies a representative sample (Bryman, 2008: 183). As the objective was to interview the everyday woman in Zanzibar, this was not seen as a disadvantage.

To a certain extent, purposive sampling (Bryman, 2016: 410) was applied as my contact at SUZA approached classes of students who had a fairly high level of English. I am aware of the fact that purposive sampling can have affected my results. I explained the purpose of my study to my contact and she forwarded this information to some classes. Because I was not present in these classes when the information was shared with the students, I am not sure what values or emphasis of the information I gave, have been communicated simultaneously. There were many shared opinions between the students that offered to participate which I will discuss more in the Discussion chapter. Nonetheless, with this in mind, the contribution of the women is seen as valuable to the study and I believe that the assistance of the contact was of great help.

20 Interview Setting

The interviews took place in Stone Town between the 29th of March 2019 and the 4th of April 2019. Two of the interviews took place in an accommodation in Stone Town, one at the informant’s workplace and the remaining four at the facilities at SUZA.All of the interviews were recorded, upon the consent of the informants. The duration of the interviews varied, the longest being 1 h and 13 min and the shortest 19 minutes. The interviews were held in English, even though not all informants were completely fluent and English not being the mother tongue for neither me nor the informants. In one interview where the informant struggled to express herself, we used some basic Swahili vocabulary and in some instances, google translate. To avoid the language barrier from affecting the results, I avoided giving examples to not affect the validity and instead used synonyms to the words the informant did not understand. This might have affected the results in a way that I could not get in-depth with some issues with one informant.

Presentation of Informants

Below follows a short presentation of the women who participated in the interviews. The names are written in pseudonyms to ensure anonymity.

Informant Birthplace Occupation Self-identified skin color Duration

Tishala Mainland Student Medium 31 min

Abby Mainland Tourist guide Medium-dark 1 h 13 min Sofia Mainland Waitress Medium (also referred to herself

as light in the interview)

40 min

Halima Pemba Student Medium 19 min

Kamara Unguja Student Medium 43 min

Neema Unguja Student Medium-dark 26 min

Adia Pemba Student Medium 34 min

Observations

The secondary method of data collection used in this paper was observations. This method was chosen because observations can exemplify ‘real-life’ happenings in the field we are studying (6 and Bellamy, 2012: 75). Certainly, the two months I spent doing observations in Zanzibar cannot account for any broad generalizations about colorism in the society. Instead, it can act as a complement to the interviews. When

21 making observations, it is important to know that not all of what is observable is simply ‘naturalistic’. I, as a researcher, can choose where I want to go, what I pay attention to and therefore, what I see (ibid: 74). As such, I acknowledge that the surroundings in which the observations have taken place, cannot count as a representation of Zanzibar. Most of the locations I navigated around were under the influence of my privilege as a European, my network and where I lived. I came across predominantly mainlanders and Zanzibaris that work in the tourism sector and people from the academic world. I mostly moved around the center of Stone Town and in the touristic northern part of the island. As such, I did not have many encounters with people living on the outskirts of ST or people who work in other fields than tourism or academia.

For eight consecutive weeks, I lived mainly in Stone Town. I conducted observations in open spaces such as restaurants, markets, the beach, social events and in general when making conversations with people I met daily. I usually carried my phone and took notes. In cases where this was not possible, I wrote down the observations during the evening at my accommodation. As a part of my observation, few pictures were taken that will be included as supporting data. Respecting the culture and the integrity of the people, the pictures do not reflect any individuals. To ensure that the observations implied significance for the research, I had some guidelines. In everyday conversations, I paid attention to keywords such as color, beautiful, hair or anything to do with ethnicity, nationality or race. Moreover, my observations also consisted of noting how my surroundings reacted to my ethnicity, my appearance and what consequences that could have for my self-perception. However, this is not an extensive ethnographic study where the observations can be assumed to affect the researcher radically. Nevertheless, a reflection on the researcher’s identity principles with regards to the new terrain can show indications of how colorism possibly affects identity construction.

Data Analysis

The processing of the data begun with transcribing the interviews with great attention. The quotations were consciously left as they were, without any grammatical adjustments for the sake of transparency and to avoid affecting the data. The transcriptions were then re-read several times, to manually focalize and get a sense of what the central themes were. Bryman argued that the handling of qualitative interviews and field notes, once it is gathered, can be baffling for many and that creates

22 a risk of becoming “a mere mouthpiece” (2016: 570, 584). Although it is important to serve informants justice with what they have put forward, it is also important to interpret and understand the findings and categorize them according to the focus of the study (ibid: 584). In this case, the data collected was large and a lot had to be screened away. A thematic analysis approach was applied where the main themes from the data acted as categories. Coyle and Murtagh highlighted the dangers of applying the IPT without clear definitions of concepts and words (2014: 42). For instance, the possibility of categorizing statements of ‘self-efficacy’ into ‘self-esteem’ can have major misleading effects for the study (Vignoles et al., 2006: 311). For transparency, an illustration showing the categorization of principles is provided (view: Appendix III). The observations, on the other hand, had been compiled in a separate document for the entirety of the stay and parts were then included in these categories. The findings were consciously listed in one chapter for the results to be compared to each other.

Validity and Reliability

Validity refers to whether or not the conclusions drawn from the findings are sound. Bryman argues that this is the most important criterion of research (2008: 32). To determine ways in which colorism affects identity construction, empirical research is essential (Rosenberg, 2012: 56). Therefore, it is of importance to state ‘what’ is being studied and that the conclusions drawn correspond to the aim and research questions. To increase the validity in this study, concepts have been thoroughly defined and a list of clarifications was introduced in the beginning. Ensuring conclusion and internal validity has been prioritized through transparency, by providing citations throughout the findings that support the conclusions and an interview guide that allows for the reader to see what has been discussed (but not limited to) (6 and Bellamy, 2012: 22). This study focalized on the island of Zanzibar, although, one of the informants lived on the mainland and came to Zanzibar often for work and leisure purposes. To not affect the validity, the data generated from the informant and other informants’ experiences from the mainland were analyzed with great precaution and mainly served in distinguishing differences between the mainland and the island.

One of the biggest limitations of this study has been that I do not possess sufficient language competencies in Kiswahili. This made it difficult when searching for informants as the majority of the people in Zanzibar do not speak English and the

23 women to an even lesser degree. Another limitation due to the language barrier was that I only spoke to fairly educated women as all of them had attended some kind of higher education. Because of this, I did not get the opportunity to speak to women in different strands of life. This could indeed have affected the reliability of the study. Moreover, the emphasis has been put on the qualitative nature of this study and the factors that can have affected the results such as sampling and the language barrier have been discussed. This makes for the external validity and reliability, which scope is for the study to be repeatable in another study or situation (Bryman, 2008: 31-32) to be low in this study. On the other hand, this is not seen as negative as some trade-offs when conducting research, are inevitable. In this particular case, causality has been prioritized over generality (6 and Bellamy, 2012: 290).

Researcher Positionality

When researching humans, the researcher is a participant in the social field that is being studied (Rosenberg, 2012: 21). In this context, I, as a researcher, am a Swedish citizen of Eritrean descent, conducting research in Zanzibar. I have chosen to do research on colorism, being no stranger to it and I also hold strong opinions on internalized forms of racism. It is therefore incorrect to state that I am oblivious to the matter. On the contrary, I had to consider my role whilst conducting the research to prevent eventual biases and to pay attention to how my positionality could affect the results. I made a conscious effort to read up on the culture of Zanzibar, talk to people about colorism, ask for their opinions and not let my prejudices prevail during the interviews, observations and when writing the paper.

To avoid conducting the interviews with no comprehension of customs or the Zanzibari culture, I conducted all of the interviews at the end of my journey. This enabled me to get a feel for how colorism played out in everyday life, according to my experiences on the island and in discussions and interactions with others. I then had a solid ground to create an interview guide that confronted the topic of colorism in an objective, easygoing and palpable way. Additionally, when doing observations questions such as ‘why’, ‘what’ and ‘where’ become relevant to ask oneself. Why a specific situation is noteworthy to observe de facto becomes subjective. To ensure that my observations were objective, I made a conscious effort to react to and notice situations where skin color, hair and any other connotations to colorism was mentioned. Another thing that

24 is of importance to mention is that I do believe that the nature of the interviews could have had another outcome if the researcher was an NPOC (non-person of color), where colorism could have been a more delicate topic to discuss. On the contrary, if the researcher was Tanzanian or Zanzibari, the interviews could probably have been able to go more into depth, seeing there is a profound understanding of the shared culture. Ethical Considerations

Taking moral considerations when studying humans is crucial (Rosenberg, 2012: 253). To avoid causing harm to the informants in any way, several ethical measures were taken. Anonymity and confidentiality were guaranteed by using fictional names and not exposing personal information of the informants. With the consent of all informants, the interviews were recorded with audio and will be deleted after the thesis is finalized. At the beginning of the interviews, the informants were also informed that they at any time, during or after the interview, could end the interview and/or demand the audio recordings to be deleted. I made sure the informants were comfortable, by asking them during the interview if they felt it was okay to continue and paying attention to any discomfort and body language. Since the topic of colorism can be a sensitive one to discuss, I excluded questions that could have been too profound. Moreover, doing a semi-structured interview often leads to a power relationship between the researcher and informant to be equalized (Lewis-Beck et al., 2004: 1021), as such this might have strengthened the ethical nature of the interview. The informants were given space to expand on matters important to them and the interviews leaned more towards a discussion.

In line with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the guidelines provided by Malmö University, the handling of personal data was registered on the University’s online registry for students using personal data for research purposes. Following regulations in Zanzibar regarding foreigners conducting research on the island, a research permit was obtained at the Ministry of Culture to be able to carry out interviews and use the collected data for the research project.

25

6.

Findings

This chapter presents the findings from both the interviews and observations simultaneously. The results are based on different categories covering the most reoccurring themes; Differences between Zanzibar and the mainland, Skin bleaching, Opinions on skin color, Mistreatment due to skin color, Opportunities due to skin color, Hair, Ethnic groups, Family relations.

Differences between Zanzibar and the mainland

One of the most frequent arguments that emerged when speaking to locals on the island was that Zanzibar and the mainland differed in culture, traditions, and norms. Many self-identified Zanzibaris viewed skin color bias as a non-issue on the island and, on the contrary, expressed that it was highly prevalent on the mainland. In conversations, especially with elderly men and women, the revolution and unification of the people of Zanzibar were often brought up as a reason why people no longer had colorist thoughts. Congruently, all four of the Zanzibar-born informants; Halima, Kamara, Neema and, Adia believed that practices of skin bleaching were imported influences from the mainland that did not belong to the culture in Zanzibar.

“It (practice of bleaching skin) is common most in mainland. People who live here in

Zanzibar maybe imitates them. The source is mainland”. – Kamara

“I think it’s more common in mainland. Many actresses in the mainland use skin

bleach. So lets say they inspire others. More in mainland. Here, people are just mixed. Maybe Arabians and some other tribes, they have medium skin. But for mainland many are black”. – Neema

“In Pemba and Zanzibar it is not common. (…) Mainland and Zanzibar are different.

When you live here, a lot of time you see the difference. A lot of people in mainland they bleach their skin, a lot of people. When you see someone you become surprised, when you look in the face they are light, when you look at the hands it’s black. So you’re surprised”. – Adia

“You know that, here we are Islam, Islamic religion here, so also we have culture here

Zanzibar”. – Adia

Some of the informants also pointed to tribalism in Tanzania, as being something foreign to Zanzibar.

26 “No tribalism in Zanzibar.. but Unguja and Pemba. Here there is Unguja and Pemba so

sometimes Pemba they don’t like Unguja. Here it’s not tribe, lakini (but) lets say like a group or society which is maybe ‘makunduchi’, here we call it shamba, it’s like the origin of you. There’s people from Kusini, from kazkazini. (villages). So sometimes it’s difficult for them to associate to each other. Sometimes there is and sometimes there isn’t”. – Neema

“In Tanzania I don’t think so. Because in Zanzibar we don’t have different kinds of tribes,

tribalism, we don’t have that in Zanzibar. But in mainland they have tribalism, there are many tribes there, so I know that until now, people are, even though they are fighting for their level best, because of that, education, different kind of knowledge, but until now people get married they consider their tribe there. You can see that this tribe cannot get married with this tribe. ‘Nyakyusa’ cannot get married to ‘Makonde’, something like that. But here in Zanzibar we don’t have that. I can say we are more united just because of that”. – Halima

Whilst the informants born in Zanzibar often marked the differences between the islands and the mainland, the mainland-born informants Abby, Sofia, and Tishala, frequently referred to Zanzibar and the mainland as being ‘the same’.

“In Tanzania girls want to change color, maybe to lotion, to mixing to change color, me I

don’t like. They (friends) say Tishala change color, you look so nice after you change. (…)

(Hometown in mainland), Zanzibar, everywhere. Because all Tanzania to like white color”.

– Tishala

My observations also confirmed a sort of “apathy” for mainlanders. For instance, when I reported one of my belongings as stolen to the police, many immediately assumed that the person was from the mainland because they were considered as “thieves” and “scams”. Moreover, I was advised to be careful when interacting with mainlanders and was told that ‘they’ did not respect the culture in Zanzibar and that they brought “bad influences” to the island such as drugs, alcohol, immodest clothing and criminality. Likewise, when I discussed colorist issues, many claimed that practices such as skin bleaching occurred within groups of mainlanders and that it was yet another “bad” thing being brought to the island.

Skin bleaching

Many of the interviews came to consist of in-depth discussions about skin bleaching. The informants were all in agreement that the usage of skin bleaching products was bad and harmful. Common opinions were that one should be happy with their appearance and love their color. Though, some also saw practical issues with bleaching such as a vicious cycle that makes it hard to stop and the impaired results, in comparison

27 to the first application. Two informants also affirmed that ‘good’ results were hard to obtain, as the knuckles are difficult to lighten and many neglect parts such as the ears, which made spotting bleached skin unmistakable.

“Anybody (should) love their color. This is Tanzanian color, (should) not change it in

to mzungu color”. – Tishala

“I hate it (skin bleaching) for real. Once they take it off, it won't come back again. It

takes 5-6 years to get the skin back. My color they can get it anytime, but their color I can't get it”. – Sofia

“You will be a slave to your own skin, because you have to use it every day just to make

you, you know?” – Abby

With the exception of Adia, all informants knew at least someone who bleached their skin regularly. Sofia and Abby also stated that many girls used to bleach their skin when they went to school. In Abby’s high school class, around half of the girls bleached their skin.

“Most of my friends from Tanzania, they are supposed to be like me, like medium dark,

but they change *giggles*, they bleach. And they are becoming lighter”. – Abby “My mom use cream. Now is white my mom. Before is black, now is white. Also my cousin, my grandmother”. – Tishala

“Yes, just 5 friends. And their color is not good. Different to the first time they put the

cream. For example, one people they have three color on their body”. – Kamara

“I think every chemical is damaging. (…) It’s something we use and this is a chemical

and this is a problem in our life in general”. – Adia

Sofia in particular had a younger sister who started lightening her skin from the age of 16. Sofia also expressed that she used to be lighter than her sister but that her sister was now the lightest in the household. When I asked about her sister’s purpose for bleaching her skin, she responded:

“Because of the slogan we have here in Tanzania; Beautiful is light. So every woman

feels beautiful when she is light. She started using it since she was young, 16 maybe. But, she can't stop because people who know her now don't know she is dark. So she can't go back”. – Sofia

28 She then went on to say that her youngest sister also wanted to start but that the family stopped her. I asked if it was because of her young age and she responded:

“No, because her skin is good. She's like my daddy, she's not much light and not dark.

She has that soft oil skin which yeah. So we want her to be like she is (…) My grand mum is super super light. My grandfather is super super light. Light in our family, it's there, but they want to be lighter”.

Even though the informants expressed aversion for skin bleaching, Kamara and Sofia also held opinions such as some products being high in quality and that some achieve good results in the beginning.

“But there are some advantages, not many. But there are some. People look good when

they make cream, in the beginning. The way you look is good. (…) I have one sister that use skin bleach. She’s about 40 years. She started it when she married. Because within a marriage a woman prefer to be more smooth. But myself, I don’t like. Even when I marry I cannot make cream. She only does when she goes to weddings. She makes kidogo (a little). Just 5 minutes. It comes from Oman. It’s to make smoother and brighter”. – Kamara

“We called the people fanta and coca cola because if you put fanta and coca cola and

you don't mix there will be two colors in there and one people will have to colors. Some chemicals came in which even the government got rid of. It was very quick and very dangerous. Even young ladies were using it. Now they use good lotions, like my sister now is using good lotion which make the skin soft and it remains as it is. She is using good quality and its quite expensive and it maintains the skin color (lightness). She never got burned, but some chemicals don't give results so you have to change”. – Sofia

To the question of why people bleach their skin, various reasons were presented. Influences from artists who collaborate with companies on social media and promote their products were frequently listed. Additionally, influences from the family and mothers who bleached were also mentioned. The most common reason, however, was that women want to find a partner more easily and that people simply think it’s more beautiful to have lighter skin. Halima, Kamara, Adia, and Neema also stated that the practice was inspired by the mainland.

“Root cause we can say inspiration. Maybe she saw someone and she think she is more

beautiful than her. And for some other reason maybe having a boyfriend. (…)” –

Neema

“In my home I see some of my neighbors just change their skin from black to white. I