Apparel returns

A design concept proposal for reducing the amount of

apparel returns

Linda Sheqi

lindasheqi@hotmail.com Interaktionsdesign Bachelor 22.5HP Spring/2019Abstract

Apparel returns of online purchases are painful for retailers as they waste resources in form of money and labour. They also have an impact on the environment. This project examined how the number of returns of apparel goods bought online can be reduced. By doing literature- and field studies, the purchase- and return motivations of consumers of B2C retailers were identified. The research revealed that the main issues of purchasing clothing online is assessing the fit of garments. Three design concepts were generated in order to discuss possible solutions to the problem of assessing fit of garments on distance.

Table of Contents

Abstract ... 2 1 Introduction ... 4 1.1 Aim ... 4 1.2 Research question ... 4 1.3 Target group ... 5 1.4 Ethics ... 5 1.5 Delimitation ... 5 2 Background ... 6 2.1 B2C retailers ... 6 2.2 Consumption ... 6 2.3 Return rates ... 72.4 Benefits of reducing apparel return rates ... 9

2.5 Apparel retail websites ... 9

2.6 Related work ... 12 3 Methods ... 15 3.1 Literature study ... 15 3.2 Interviews ... 15 3.3 Observations ... 15 3.4 Co-design workshop ... 16 3.5 Sketching ... 16 3.6 Focus group ... 16 4 Design Process ... 17

4.1 Interviews and observations ... 17

4.2 Co-design workshop ... 23

4.3 Sketching on concepts ... 28

4.4 Focus group ... 31

5 Discussion ... 32

5.1 Implementation of methods and theories ... 32

5.2 Main findings ... 34

5.3 Concept ... 34

5.4 Future work ... 35

6 Conclusion ... 36

1 Introduction

E-commerce allows consumers to purchase goods from the comfort of their own homes, on the go and from other countries. Crowds of people and long queues can be avoided, and when needed, online shopping can easily be paused and continued another time.

One of the prominent pains of e-commerce is the challenge consumers face to judge a product’s experiential information. E-commerce businesses are working hard on bridging this gap that is making physical- and online stores differ so much. A commonly embraced solution has been to offer consumers clear and lenient return policies. This way, consumers get a chance to examine or try out what they have bought without being bound to their purchases. The perceived risk of buying goods online consequently reduces, making consumers more inclined to place orders in the first place.

Having a lenient return policy is a great way to ensure consumers that they can change their minds, but it does not provide richer experiential knowledge about the product before purchase. The insecurity over a product’s experiential information before purchase and lenient return policies have evoked a behaviour amongst some people in which a return is an obvious part of the online shopping process. For example, some people intentionally buy two examples of an item knowing that they will return at least one, because they are unsure of what size to get, what colour to choose, to get a feel for a material, or even to reach the total price needed to obtain free shipping. From an environmental point of view, this devours and wastes resources in the form of product packaging and transportation fuels. It also exhausts a company’s labour.

1.1 Aim

The aim of this project is to investigate how interaction design can help reduce the number of apparels returns of online purchases. Examining return reasons, consumption behaviours, attitudes and motivations, as well as what tools online apparel retailers offer to support their customers is an approach to inform a possible design concept for decreasing the number of returned garments of online purchases. The reduction is envisioned to cut return costs for companies, increase the probability of customer satisfaction with a service or a product, and lessen the emissions of online apparel retailers.

1.2 Research question

How can interaction design contribute to the prevention and reduction of apparel returns of online purchases?

1.3 Target group

The primary target group of this research is young women aged 18-29. In the Nordics, women buy apparel to a greater extent and make more returns than men. More specifically, it is young women aged 18-29 who stand for the highest return rate of all groups (PostNord, 2018c). Consequently, they are the ideal target group of this research.

1.4 Ethics

Before participating in interviews, observations, a co-design workshop and a focus group, participants were informed about the project and its purpose. They were also informed of why they were invited to be a part of the project, how they were expected to contribute and that their contribution would be treated anonymously. Further, they were informed that materials gathered from the sessions would be used for research purposes and could be viewed by the public at a later point. The participants of the co-design workshop were asked to sign consent forms accepting or declining being recorded and photographed during the session.

1.5 Delimitation

There are many reasons as to why people return apparel purchased online. Some reasons include fraudulent behaviours such as wardrobing, while other derive from product defects, companies shipping the wrong product, or that a product arrives too late and is not needed anymore (PostNord, 2018a). This project did not consider the return reasons just described in order to limit the scope of the project to a manageable field within the timeframe. Most of the insights were also limited to consumers from Sweden since the participants involved in the project were from there. Another motive for limiting the research to Swedish consumers was that shopping motives and behaviours are likely to be different among various countries due to different socioeconomic backgrounds, consumption behaviours and cultural trends.

2 Background

This chapter aims to inform about the area of online retailing and returns, and to outline the theoretical perspectives that are applicable to the research problem.

It presents the business to consumer (B2C) model along with a theoretical framework which highlights the differences between in-store purchases and remote purchases, as well as the implications of the later. The chapter also captures peoples’ consumption behaviours - why and how people purchase online, which explains a portion of product returns. Continuing, return rates are given further explanation, as well as why they should be reduced. Finally, four retailing websites and related work are examined.

2.1 B2C retailers

B2C is one of the four main types of electronic commerce (e-commerce) models that describe transactions occurring over the internet. B2C retailers in e-commerce are defined as retailers who sell goods or services to consumers over the internet (Shopify, n.d). Traditionally, retailers have established relations with their customers through physical stores. However, with the success of internet, many retailers have found that being available online enables them to reach out to more consumers and petition against other retailers (Soop and Johansson, 2016).

2.1.1 Remote purchase – a two stage decision process

A purchase made by a consumer from an online retailer is considered to be a remote purchase, which is argued to differ from traditional bricks-and-mortar purchases. In-store retailers allow consumers to experience and examine products hands-on. When customers make the decisions to purchase, they usually have already gained experiential information and intend to keep the product. Remote purchases, however, can typically be viewed as consisting of two stages, where the first refers to a consumer’s decision to order an item (purchase decision) while the other refers to their decision to keep or return the item (keep/return decision). A period of time separates the two, making experiential information mostly only available after the purchase decision, as the purchased item has been received (Wood, 2001).

2.2 Consumption

In 2018 in the Nordics, 61% of the residents shopped online in an average month, spending a total of EUR 22.4 billion. In general, Swedish consumers mostly shop from domestic web shops and their most popular product category to buy from is apparel and footwear (PostNord, 2018b).

2.2.1 Online shopping motivations and behaviours

Socioeconomic shifts such as dual-income households, active and recreational lifestyles as well as increased transportation possibilities are supporting a culture in which time rather than money is becoming a valuable commodity. As a result, consumers strive to make their shopping patterns more efficient. In contrast to physical stores, e-commerce is available around the clock and typically accessible through stationary and mobile devices, allowing people to visit retailers anywhere at any time.

The accessibility of online retailers drives different visiting and purchasing motivations, some of which can be sorted into four groups. Directed buyers are goal-directed in their search behaviour and have their minds set on a specific product category. They are devoted to product-level information and exhibit a significantly low interest in product category variation. Search

visitors exhibit goal-directed search behaviour as well; however, to identify

the desired product, they have to explore options within a category of interest. Therefore, product purchase may occur at a later time, as they have narrowed down their options. Hedonic browsers typically do not have a product or product category in mind, and also do not involve in heavy deliberation on particular items. Purchases made by hedonic browsers may be observed as impulsive. Finally, knowledge-building visitors have no purchase intentions. Instead, they are visiting the store to gather product information available (Moe, 2003).

2.2.2 Trends

Globalization has made the production of cheap clothes possible, so to the extent that consumers consider clothing as being disposable. This phenomenon is called “fast fashion”. Affordable apparel and must-haves created by fashion magazines provoke a behaviour which makes people consume more (Claudio, 2007). New apparel collections are created continuously and quick to replace the previous ones.

2.3 Return rates

A survey by PostNord (2018c) with over 89.000 respondents showed that just over one in ten e-commerce consumers in the Nordics had returned at least one item purchased online in the last month. Because size and fit are difficult to assess online and often vary between brands, apparel and footwear make up the highest return rate of e-commerce returns.

2.3.1 Experiential information

Difficulty in assessing the size and fit of a garment are only some reasons that contribute to consumer returns. As remote purchases hinder direct examination of products, the quality of information about sensory attributes becomes inferior. Consumers must wait for delivery of the products to assemble their experiential information (Wood, 2001). The sensory

attributes can be referred to as colour, design, fabric and fit (Kim and Knight, 2007).

2.3.2 Return policy leniency

To atone for the lack of initial experiential attribute information of a product and to minimize the consumer risk, retailers have adopted the practice of offering lenient return policies. Since the cost of reversing a poor purchase decision reduces for consumers when faced with a lenient return policy, they become more inclined to purchase in the first place. However, the deliberation during the purchase decision stage becomes sparse, and the time devoted to it reduces, making the keep/return decision more critical.

Another benefit of providing mild policy conditions is that the products offered are perceived by consumers to be of higher quality, both before purchase and after receipt, while restrictive policy conditions signal lower product quality (Wood, 2001). D. Bahn and Boyd (2014) however, claim that their research findings contradict those found in the existing marketing literature. Rather than imposing that restrictive return policies signal low quality of products and increased purchase risk; they argue that consumers’ information processing strategies triggered by the different return policies need to be supported by retailers. They argue that lenient return policies trigger heuristic information processing, making consumers shopping under lenient policies more attracted to products that accommodate heuristic information processing. The heuristic processing strategy entails seeking cues and using little cognitive effort in the evaluation of assortments. Restrictive return policies, on the other hand, typically trigger systematic processing, making consumers shopping under restrictive policies more attracted to products that accommodate systematic information processing. The systematic processing strategy entails higher cognitive effort and more attentive deliberation of the information provided.

A popular managerial theory amongst retailers discloses that a product which is easy to return is more probable to be returned, and an increase in sales should only increase profits if return rates do not rise significantly (Wood, 2001). According to Soop and Johansson (2016), the large e-commerce retailer Zalando has been reported having up to 50% returns. The number is not insignificant; however, retailers still see lenient return policies as a powerful competitive weapon. Consumers who face equivalent alternatives from different retailers are more motivated to select the retailer with a more lenient return policy (Wood, 2001). Free returns are also essential for capturing fashion consumers (PostNord, 2018c). Additionally, the restrictiveness of return policies influences consumer trial of new products (D. Bahn and Boyd, 2014).

2.4 Benefits of reducing apparel return rates

Although lenient return policies prove to have many benefits, the return rates cannot be neglected. There are several sectors that would benefit from a reduction of apparel returns.

2.4.1 Company labour and money

Apparel returns cost retailers and manufacturers money in terms of having to handle, transport and process the products that are returned. In addition to administration and management, product returns need to be converted into productive assets (Meyer, 1999). Reducing the number of returns would consequently entail less time and money spent from companies on product returns.

2.4.2 Relational outcome

It has been demonstrated that product returns have a negative impact on customer satisfaction with retailers, the customers’ trust toward the retailer and the word-of-mouth (Walsh and Brylla, 2016). In order to sustain apparel customers and keep a positive relational outcome, retailers need to find novel ways to reduce the return rates without sacrificing their lenient return policies.

2.4.3 Environmental footprint

Studies on different types of retails have revealed diverse environmental footprints. The footprints varied depending on shipping distances, return rates, shopping allocations, population density, amount of packaging, and form of transport. Although some studies have shown an opportunity to reduce energy consumption and emissions related to for example transportations of online grocery shopping, they have also emphasized that indirect effects such as change of shopping habits might play a significant role on the overall environmental impact. In the end, comparing traditional and e-commerce retailers however does not appear to be of main relevance. Instead, developing methods to improve the environmental performance of each value chain is suggested as an alternative approach (Fichter, 2002). Still, the issues regarding environmental footprint of apparel returns should not be discarded. Up to 25% of returned items end up in landfills without ever having been used (Bold Metrics, 2019). Not only do apparel returns emit pollution as they are being transported to and from consumers, but also as the garments are being produced. The excessive production of apparel may not be justified even in those cases when garments have been used; however, when a garment is destroyed, all energy used to manufacture and transport it goes to waste.

2.5 Apparel retail websites

An inspection of methods and functions that websites provide to help consumers attain experiential attributes of garments was made. The websites

used for the inspection were Asos (2019a), Nelly (n.d), Zalando (n.da) and Boozt (2019).

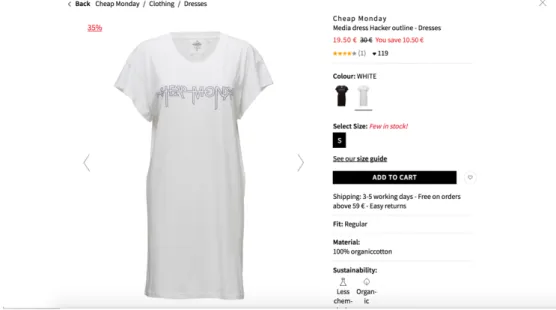

2.5.1 Images

All websites use images to showcase garments that are available to purchase. The garments are worn by models on most of the websites, while Boozt (2019) mostly showcase their garments without models. By having models wear the garments, customers can get an idea of the garments’ proportions. To exemplify, Figure 1 and Figure 2 showcase the same dress. In Figure 1, it is clear that the dress ends above the knees and the sleeves end slightly above the elbows on the model, meanwhile, in Figure 2 it is much more challenging to assess this information. Combined with other information such as the height of the model, the proportions of the dress displayed on the model might be comprehensible for customers who have the same height as the model. For others, the information might not be as easily assessed.

Typically, the front and the back of the garments are photographed. Some retailers also include close up images of the garments. To further help customers see details, the images or parts of the images can be magnified. This allows a better assessment of materials and other details such as buttons and stitches.

Figure 2. Cheap Monday dress on Boozt (2019).

2.5.2 Videos

In addition to images, some of the websites provide videos of models wearing the garments. The videos typically offer slightly different lightning than the images, which might help provide an idea of how the garments react to different lights and what their colours might look like when received. As the models move around, the movement of the materials can be seen and might help indicate if the material is stiff or soft. Since the models turn around to show the back of the garments that they are wearing, customers can view all angles of garments, including the sides, which might eliminate some surprises upon product arrival.

2.5.3 360º

Nelly (n.d) offers a 360º view of some of the garments that they sell. The 360º view allows customers to view clothing from all sides.

2.5.4 Text descriptions

All the websites use text descriptions that typically consist of product information explaining the garments’ pattern, form, style and other details. They also provide specifics of garment materials such as fabric type and percentage. Some websites also describe how the fabric behaves and moves. Retailers that use models to display their garments include the height of the model and the size of the garment that the model is wearing. Zalando (n.da) further describes the fit, length and sleeve length of some garments.

2.5.5 Customer reviews

Nelly (n.d) and Zalando (n.da) provide customer reviews allowing customers to write about their experiences with the garments that they have purchased. Reviewers can insert their names or stay anonymous, rate the garments using up to five stars and write comments about the garment. As the reviews are

published, they can be read by other customers. The amount of reviews varies among the garments and some comments highlight the fit, material and durability of the garment while other comments seek to request a stock fill. The customer reviews at Nelly (n.d) are placed at the bottom of the page above the page footer while at Zalando (n.da), they are placed right under the images of the garments.

2.5.6 Size charts

Asos (2019a) has a size guide that can be viewed in centimetre and inches. For each size, the appropriate measurements for bust, waist and low hip are available. They also include a converter that converts sizes from UK, USA, EU, IT, AU and RU. To help customers know how to measure their bodies, they provide a guide that explains where and how to measure in order to extract measurements. When the garment on the product page selected is produced by another brand, the size guide is not displayed. This is because the brands’ sizing differs from Asos’. On some product pages, a Fit Assistant is provided, asking about the customers’ height, age and weight to recommend a size. It also considers previous orders that the customer has placed through the website (Asos, 2019b).

Zalando (n.da) and Boozt (2019) have similar size guides as Asos (2019a); however, Zalando points out that the guide is only a general guide and that sizes can vary between brands and models (Zalando, n.db). Boozt (2019) does not provide any guide which explains how to measure in order to extract the specific measurements.

Nelly (n.d) also include size guides on their product pages. Their size guides are divided into four sections; “clothing”, “trousers”, “shoes” and “bra’s”. It is not clear if the measurements apply to all brands and garments.

2.6 Related work

Work that relates to the research question by either aiming to reduce the number of product returns or to assess experiential information about apparels is presented in this section.

2.6.1 Volumental

Volumental offers a 3D foot scanner (Figure 3) and an AI-driven footwear recommendation software to help retailers offer the best matching products to their customers. The Volumental 3D foot scanner scans a pair of feet and creates a 3D model of them based on ten separate measurements. The 3D model is shown on a UI (Figure 4) allowing retailers to help shoppers find the right shoes. The algorithm combines historical purchase data with scanned foot data and shopper preferences. The product is claimed to reduce the number of shoe returns by 25% (Volumental, n.d).

Figure 3. Volumental 3D foot scanner (Volumental, n.d).

Figure 4. Volumental user interface (Volumental, n.d).

2.6.2 Virtusize

Virtusize is a product that online apparel retailers can implement on their websites to help their customers choose the right size. By comparing a garment that the customer wants to buy to a previous purchase or a garment from home, the buyer gets an idea of what size to select (Figure 5). The solution only requires two to four pivotal measurements (Virtusize, n.d).

Figure 5. Virtusize (Virtusize, n.d).

2.6.3 Impact of prechoice process on product returns

Bechwati and Siegal (2005) investigate how consumers’ pre-decisional stage affect their post-purchase behaviours. The aim is to identify what makes consumers likely to return products. Their research finds that consumers who have been presented to alternative options in the pre-purchase stage and are later faced with disconfirming information favouring a new brand are less likely to return a product than consumers who have been exposed solely to positive information about the selected brand at the pre-purchase stage.

3 Methods

This chapter presents the methods used to carry out the project and why they were used.

The project mainly adopted the methods and principles of a user-centred design process. In a user-centred design process, the user is spoken for using data collected through primary or secondary sources. The data collected is translated to design criteria, which are then interpreted and used in the development of an artefact. The goal is to ensure that the artefact meets the users’ needs (Sanders, 2002). In this project, people from the target group were used as the primary sources, while literature studies were used as secondary sources.

3.1 Literature study

A review of existing literature was conducted to gain insight into e-commerce, consumption behaviours and return rates as well as to identify areas needing further research. Literature reviews help to inform on the state of knowledge within the area of interest and outline theoretical perspectives that might be relevant and applicable to the research problem (Muratovski, 2016).

3.2 Interviews

In order to gather qualitative data, people mainly from the target group were interviewed. The interviews were divided into two parts, where the first part consisted of semi-structured in-depth questions to identify the individuals’ shopping- and return-behaviours, what their reasons for returning products had been in the past, as well as how, when and why they shop for certain products. Semi-structured interviews allow for questions emerging from the session to be discussed, while individual in-depth interviews allow discussions of more social and personal matters (DiCicco-Bloom and Crabtree, 2006).

The second part of the interviews was semi-structured as well, but the participants were provided with tools to further express their knowledge, experiences and attitudes towards experiential attributes that had been identified through the literature review. The intention was for their contributions to guide the project and be used to identify areas of interest for further investigation.

3.3 Observations

Observations were conducted to find out what kind of sensory information the participants looked for and how they received it when shopping for apparel online. When asking people about their behaviours, people may alter the accounts of their behaviours to benefit the interviewer or to match cultural expectations. Sometimes it can also be difficult for them to put their

activities into words. Doing observations is a way to distinguish what people say from what they do. Combining observations with interviewing techniques allows the observer to ask questions about what the participant is doing (Schuler and Namioka, 1993), and therefore not only observe what the participant is doing but also to get an idea of why.

3.4 Co-design workshop

A co-design workshop was held with the aim to, collaboratively with people from the target group, generate novel approaches which would help online shoppers to assess the fit of garments. Not only would the participants be useful in generating ideas, but also in giving an indication of what solutions they would welcome. The co-design workshop adopted the methods and principles of participatory design, making the target group play a central role in the design process. Participatory design (PD) refers to the approach that encourages users of a system to assist in knowledge development and in designing the system. As users are assumed to be experts of their own experiences - what they do and what they need, they become central to the design process. People affected by decisions or events should be able to influence them (Schuler and Namioka, 1993), and by providing tools, the researcher supports the users to ideate and express themselves (Sanders and Stappers, 2012). Rather than adapting the exact design ideas that PD approaches result in, the results need to be reinterpreted in order to understand the users’ needs and values (Lim, Stolterman and Tenenberg, 2008).

3.5 Sketching

In this project, sketches were created to visualise ideas and as a means to get feedback on various concepts from people of the target group. Sketches should be quick to make or give the impression that they are. This invites suggestions, criticism, and change. Sketches become valuable as they stimulate desired and appropriate behaviours, discussions and interactions (Buxton, 2010).

3.6 Focus group

In order to receive feedback on the concepts generated after the co-design workshop, a focus group was held. A focus group is an assembling of a group of people who engage in a discussion about a topic and can be used to receive feedback on the topic from the participants (Krueger, 2014).

4 Design Process

This chapter describes the design process of this project. The purpose and execution of each moment are described, along with the findings. After each session, the findings are analysed and sorted to identify the next steps in the design process.

4.1 Interviews and observations

Interviews and observations were held in one session with the participants engaging individually in each session. Although women make up most of the returns, both women and men were involved in the interviews and observations. The idea was to gain insight into how they shop and return clothes online and finally design to reduce returns made by all genders. Three women aged 20-29 and two males aged 22 and 39 participated. All five sessions were organized and took about 45-60 minutes each.

4.1.1 Interviews: general questions

The first part of the interviews aimed to elicit information about the participants’ occupations, motives for and habits of buying apparel online as well as reasons for previously returning clothing purchased online. Additionally, they were asked to describe how they judged if they were going to buy a garment or not.

Interviewees reported similar reasons for purchasing apparel online. For the full-time employee and a parent of young children, online shopping is considered to be time efficient. When life is hectic, and work and other responsibilities take up much time, online retailers allow for a shopping experience in a calm and private environment. It also allows for late night purchases. Further, e-commerce provides a more significant range and variety of products, more possibilities to sort through them, and makes it easier to find similar products. Simultaneously, online shopping has its restraints. Participants reported worrying about the fit of the purchased product, one of them saying: “I’m never 100% [confident] that I will receive what I purchased”. Also, buying too many products seems to become effortless. Weighty baskets typically signal the extent of garments collected in stores; however, this physical response is lacking when shopping online. One of the participants reported the activity of exploring apparel in store as being more fun because of the physical feedback it allows. Touching and smelling materials enhances the experience of a product and makes it easy to explore its material properties such as transparency and texture.

Most of the previous returns that participants had made were due to poor fit. In one case, an interviewee had used the model wearing a specific product as a reference when choosing his size. By looking at the model’s height, estimating the model’s proportions, and comparing it with his body type and height, he selected a size which he thought would fit. When the product

arrived, he discovered that the garment was too small, explaining it by saying “I believe that my shoulders were wider than the model’s.”

Other reasons for apparel returns included product material looking and feeling different than expected. For example, an interviewee described being disappointed in the material of a jumpsuit being ribbed, which had not been clear when she had purchased it. The garment had also been perceived as “too revealing” which did not feel appropriate for the occasion it was meant to be worn. Material and fit were also elements that could evoke feelings such as irritation because of a too tight fit or a material absorbing odours.

The interviewees' attitudes toward returns varied somewhat. One thought of it as a time- and energy-draining process, while one said that "they should know that they are selling bad products," followed by "I have the right to return [products]."

4.1.2 Interviews: experiential attributes

In the second part of the interviews, the objective was to explore and discuss what experiential elements participants found to be important when examining a garment. The participants were given four pieces of paper with the attributes material, fit, colour, and design separately written on them (Figure 6). They were then asked to write down words of experiential elements that they thought matched the attributes. When going through the notes together with the participants, their attitudes towards and importance of the elements when purchasing apparel online were discussed.

Material evoked words that refer to different types of materials such as

polyester, silk, viscose and cotton. Viscose and cotton were almost exclusively associated with being soft and comfortable, while polyester was associated with being unpleasant. For one of the participants, selecting vegan materials was crucial when shopping for clothes. Additionally, the thickness, structure, tightness, stretch, maintenance, durability and environmental impact of the material were brought up as being qualities that occasionally matter.

Fit was associated with words such as tight, loose, short, long and big. Having

previous experience from the brands of the garments they examined typically helped estimating what size to get when purchasing their products. Checking measurement guides was mentioned, but not commonly used among the interviewees. Further, one participant mentioned reading product reviews as a helping tool when considering what size to get.

Colour generated a multitude of answers emphasizing the convenience of the

colour black which would typically go with everything, while other colours such as white could be inconvenient for example when being a parent of small children. One interviewee explicitly preferred colourful apparel, while others sometimes worried if certain colours and nuances of colours would suit them.

Design closely correlated with fit, colour and material. It was also associated

with a variety of words such as brand, logotype, minimalism, stitching and uniqueness.

In common for all attributes was that participants exhibited having preferences and frequently relied on previous experiences with materials, brands and garments when searching for and purchasing apparel online.

Figure 6. Interviewee defining experiential attributes.

4.1.3 Observations

In the third and last part of the sessions, the objective was to find out what kind of sensory information the participants looked for and how they received it. Prior to starting, participants were asked if there was anything that they were considering purchasing. All except from one had either a specific product or a product category in mind. They were asked to visit a to them well known online apparel store and either find the specific product they were thinking about or search for a product that they liked, and at the same time think aloud (Figure 7). Navigating through the websites, they described what they saw, what they were looking for as well as their attitudes towards the tools provided by the websites for them to judge the clothes that they were looking at. Since the tools varied among the websites, participants were also asked about ones from the website analysis that did not exist on the website they had chosen.

As the participants searched for a product or product category, filters were frequently used to narrow down the range of products. They were for example filtered by colour or type of product. Sequentially, participants looked at product images and headers to distinguish the products from each other. After selecting a specific product, it was common to look through the images and videos that were available. The range of images typically provided a variety of angles of the product which in turn allowed greater examination

and details helping to eliminate undesirable products. The zooming tool provided helped in examining details such as zippers and the structure of materials. However, images would also generate feelings of insecurity. The participants reported worrying if the garments had been manipulated with clips behind the models’ backs. One interviewee shared that she sometimes copied the name of the product and googled it to search for alternative images of the product uploaded by the public to get a better sense of its fit and colour on other people and in other lights.

Videos of models wearing the garments were perceived to be more trustworthy than images. In videos, lightning would feel more authentic, less likely to be edited and the probability of the fit of the garment on the model being manipulated would feel minimal. The movement of the material could also be captured and give an indication of how the garment would adapt to the body.

Product descriptions helped confirm information such as material of garment and other details like number of pockets, while model height and size became a reference when choosing size. When discussing size charts, they were perceived as not being reliable and because different brands have the same sizes but different measurements, sizing would become difficult when ordering from new brands.

Product reviews were also used by some to validate products. Positive product reviews were expressed to motivate purchase, while negative reviews deterred purchases. Mixed reviews would feel conflicting but not exclusively deter purchase. By purchasing a product despite its negative reviews, a participant stated that he could try the product out for himself. He added that by knowing that the product can be returned makes the purchase feel less risky.

Reviews on garment sizes were approached with caution by some. One interviewee avoided reading comments on sizing as she feared that some people might have a false perception of their bodies and therefore order the wrong sizes. Some further acknowledged that they sometimes ordered two different sizes of the same garment with the intention to return one of them. This way, they could try the clothes out before deciding on what size to keep. The participant who did not have a specific product or product category in mind imagined occasions when the garments would be good to own. She for example chose a bikini that she liked and talked about how it would be perfect for a future vacation. She then admitted that she frequently makes up situations where she convinces herself that she will need the garment that she is looking at. After ordering it however, she typically forgets that she has made the purchase and is surprised when the package arrives. Because of inconveniences, she tries to avoid returning those purchases, but at the same time feels like this behaviour makes her apparel consumption abundant.

Figure 7. Participant visiting Zalando during observation.

4.1.4 Analysis of interviews and observations

After all interviews and observations had been conducted, the results were analysed. In hindsight, it became clear that by asking the participants to browse for a product that they had been thinking of purchasing, they were directed to become directed buyers and search visitors. On the contrary, the final interviewee who had no specific visiting goal became a hedonic browser and shed light on the waiting process (the period between purchase and product arrival) which the other participants barely touched upon. The sessions were also unintentionally constructed to examine the waiting process the least. The questions asked during the first part of the interviews slightly touched upon all stages, while the second part of the interviews and observations investigated the purchase decision and the searching process (the period prior to purchase) more profoundly.

Nonetheless, the sessions and the progression of the project lead to two separate paths that were possible to proceed with. One could entail examining hedonic browsers and the waiting process, and the other could entail further examination of directed buyers, search visitors and experiential information. It should not be excluded that the waiting process of directed buyers and search visitors might look similar as the waiting process of hedonic browsers. Further, hedonic browsers might approach experiential information differently than directed buyers and search visitors, however, this was not prominent in the results of the sessions and that is most likely because of how they were constructed.

The project proceeded the direction of exploring directed buyers, search visitors and experiential information since the sessions previously conducted had already started exploring these factors and generated insights about them. In order to sort the insights from all five sessions, they were categorized through affinity diagrams. The first affinity diagram (Figure 8) sorted the insights into seven categories; advantages and disadvantages of shopping online, returns, consumption, emotions, tools and methods, preferences and insecurities. Since the insights were plenty and too much to consider all at once, a second affinity diagram (Figure 9) was created focusing on the main reasons that participants reported returning apparel, their thoughts on and use of the functions provided by retailing websites, as well as their search- and purchase habits.

Because videos and images are not completely within the realm of interaction design, they were disregarded moving forward. What stood out was not only the amount of functions and tools available to assess the fit of a garment but also the ways that these were used and trusted. Therefore, the project shifted its focus to improving how online retailers can help customers assess the right fit of garments through their websites.

Figure 9. Second affinity diagram of interviews and observations.

4.2 Co-design workshop

After the interviews and observations had been conducted and analysed, a co-design workshop was held. The aim of the co-co-design workshop was to generate new approaches for helping online buyers assess the fit of apparel on distance. Since the workshop would entail talking about the body and different features of the body, only women were invited to participate. The co-design workshop was held in the afternoon and took two hours. Five women from the main target group were involved. The participants were between the ages of 20-29, two of whom had previously participated in the interviews and observations.

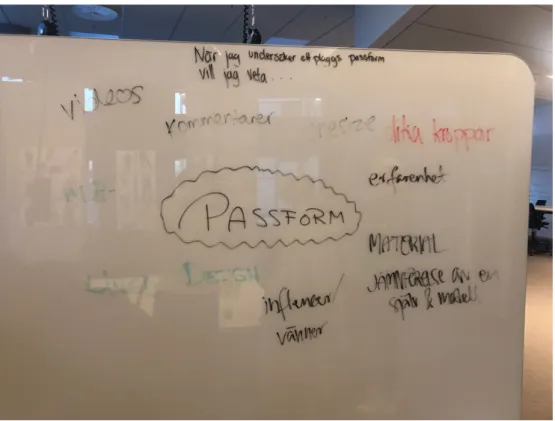

4.2.1 Mind map

The first assignment intended to start a conversation between the participants and served as a warm up. The participants were asked to collaboratively create a mind map (Figure 10) over factors that they consider when assessing the fit of a garment when shopping online. Images of models wearing different clothing were printed out and pinned to boards so that the participants would have something to reference to. Much like in the previous interviews and observations, the participants reported considering the length of clothes, the size of the model, the form of the garment and looking at videos, images and reading reviews amongst other things. However, they also reported asking friends about what sizes they had chosen and how they had experienced products prior to purchasing themselves. Since models that are used to showcase garments are typically tall and skinny, not everybody can relate to their looks and bodies. Furthermore, how the models are styled also

affect how people relate to the garments that the retailers are trying to sell. For example, one of the participants pointed out that a dress styled with heels might not look the same when styled with sneakers. She was trying to convey the struggle of imagining a garment in an alternative style which could make the product more or less appealing.

Figure 10. Mind map from co-design workshop.

4.2.2 Sketching freely

The second assignment entailed that each participant would select one or several keywords from the mind map and sketch (Figure 11) how they would design for better assessment of that word without any restrictions.

The first sketch aimed to prompt a more inclusive fashion industry. Having models that vary in height, size, skin- and hair colours and including models with disabilities would allow more people to relate to the models and “find themselves” on the website. By showing images and reviews uploaded by customers, the garment could be viewed in different environments, lights and positions. It would also offer more transparency in how the garment actually is. The participant stated that “if the products suck then everybody will see it”, referring to how implementing customer reviews and images would help other customers make a decision prior to purchasing a product.

The second sketch aimed to show garments on models that are the same height and size as the consumer. By inserting information about height, size, weight and shoe size, the customer is presented to a model with similar features. Clicking through the different sizes, the customer can see how all of them look on the model and choose the fit that is the most appealing.

The third sketch presented a concept which consists of three steps. In the first step, customers insert measurements from height, chest, waist, hips, thighs, arms and other measurements that could be of importance. The data produces a visual representation of the inserted measurements. In the second step, customers are presented to a couple of images and asked to select the styles that speak to them the most. The third and last step aims to allow customers to specify details such as if they wish to have a short t-shirt or loose jeans for example. Finally, customers are matched with certain outfits and sizes.

The fourth sketch proposed to implement a machine that could scan bodies and extract measurements and volumes. Alternatively, the measurements could be inserted manually. Depending on the material of the garment, the customer size and shape of body and if the garment should have a tight or loose fit, a suitable size is recommended to fit the customer’s requests. One of the participants had trouble thinking of and sketching a possible solution, thus only four concepts were presented.

Figure 11. Two of the participants sketching freely in the co-design workshop.

4.2.3 Re-designing size charts and customer reviews

The third assignment aimed to let the participants re-design size charts and customer reviews. These had been identified as needing some alteration through the interviews and observations. Screenshots of a size chart and customer reviews from Nelly.com were printed out for the participants to re-design (Figure 12). The participants were divided into groups of two and three. They were given three sets of cards each which aimed to act as tools to help generate ideas (Figure 13). The cards consisted of three categories;

customer reviews, size charts and the body. Each category had a subset of cards with keywords stemming from and generated after the interviews and observations.

This time, the participants had not sketched their solutions to the same extent as they had done in the first part of the workshop. Instead, they had created lists with criteria for their proposed solutions. The criteria presented for the size guide from the first group were that customers should be able to upload images of themselves wearing the garments. Size guides should also display measurements of other body parts such as length of arms and other measurements that might be relevant for the garment. The size guides should also display more information about the materials of the garment because if consumers do not know anything about materials they will not know if the garment will stretch or fit tight. Finally, they wanted a size guide where they could insert their own measurements and consequently avoid having to compare different size guides from different brands.

Their criteria for customer reviews were to incorporate statistics on how people had experienced a garment, for example its durability and its stretchiness. To make people leave reviews, retailers could send out an e-mail about a month after purchase asking the customer to leave a review. However, the reviews should be able to be written anonymously and should not be complicated to carry out.

Finally, they presented thoughts about the last category which aimed to examine how to represent different body shapes. Their discussion ended up being about what terms retailers use to talk about the body, sizes and fits. They were sceptical of a certain word used in the fashion industry. One of the participants said; "The word “standard” should not be included, it is a bad word. Every time that the word standard is used it means that everything else is not standard, which means that some things are normal, and other things are abnormal. This means that one normalizes one type of body and not the other.”. The group perceived “tall” and “petite” as being more neutral and helpful to people with different heights.

The second group suggested providing customers some sort of reward for writing reviews. One type of reward could be collecting points for every review that the customer writes, which could later be converted to money or a discount. They continued by discussing the downside of giving out rewards this way because of the possibility of attracting people who would misuse the system and leave fabricated reviews simply for the profits.

Figure 12. Participants examining the size guide and customer reviews.

Figure 13. Using cards to generate ideas.

4.2.4 Analysis of co-design workshop

After the co-design workshop, the discussions and design ideas of the participants were reinterpreted to their needs and values. The material generated pointed toward a longing for representations of peoples’ own

bodies and styles, since not everybody can use the heights and sizes of the models as reference when selecting a size. Because the participants had different preferences and ideas of what a “perfect” or “standard” fit was, they would need a more nuanced way of assessing the fit of a garment. Displaying a greater range of measurements that are relevant for the garment would further help in selecting a size that matches the personal preferences.

Receiving information about a material can also affect what size a customer selects. However, people who are not knowledgeable about materials might need further assistance in knowing how the material will affect what size to select.

Finally, the wish for the ability of inserting measurements to be recommended a size is a sign of the wish to use less cognitive effort when selecting a size.

4.3 Sketching on concepts

The findings from the interviews, observations and co-design workshop served as a foundation for the concept ideation phase.

The first concept (Figure 14) was an iteration of a concept that the participants from the co-design workshop had suggested and was aiming to address the issue of not knowing what sizes the people leaving reviews had purchased and what size they typically wore. The concept is a re-design of customer reviews and allows customers to leave reviews on products that they have purchased and that have been delivered to them. The review concept has inputs for name, height, weight, the size that the customer typically purchases, the size that the customer selected when purchasing the garment that the review is regarding, what they liked about the fit of the garment, what they disliked about the fit of the garment, and a final input for other comments. The information is then added as a review and presented to other consumers that visit the product page.

Figure 14. Sketch of the first concept.

The second concept (Figure 15) was trying to address the issue of consumers purchasing two different sizes of the same garment. The idea is that as customers have added two different sizes to their shopping basket, they are directed to reviews of the garment in order to help them select the size that is likely to fit the best. It might also make the customer think twice prior to purchasing two sizes of the same product when they intend to return one.

The third concept (Figure 17) was a bit more complex and aimed to provide more details about the fit and the material of the garment. It also aimed to match the customer with feedback from other customers who have similar body measurements. First, the customers create profiles by inserting measurements of their own bodies such as the length and circumference of body parts like arms, legs, neck, waist, hip, bust and other relevant measurements. The measurements inserted create a visual representation of the body.

As a review is created, the reviewer is asked to rate how the garment fit on specific body parts that are of relevance depending on the garment. The answers are compiled and displayed to people with similar measurements as the reviewers.

Figure 16. Sketch of the third concept.

4.4 Focus group

A focus group session was held to gather feedback on what elements of the concepts were liked and disliked and why. Three females attended the focus group, two of whom had participated in the co-design workshop. All three sketches of the concepts were presented before the discussion started. Commenting on the first concept, one of the participants said that she would rather see what type of body the reviewer has than seeing their weight. Just because someone weighs as much as you, it does not mean that their body type is the same as yours. She also said that if she was to write a review, she would probably not like to write much because it takes time and energy to think of what to write and how to write it. Another participant felt like describing the fit with the words “tight” or “loose” would be too broad. She said, “what is perceived as tight by someone might be perceived as too loose for me”.

For the second concept, the participants did not have much feedback. Two of them felt like if they were provided with information about the stretch of the garment, they would more likely consider purchasing the smaller size. The third participant would appreciate a size guide if it was specifically designed for the garment. If the size guide shown is applicable to all shirts, she would not feel confident in using it and spend time on measuring herself. However, she felt like the pop-up could possibly make her check the reviews one more time and become more confident about selecting only one size.

The participants were positive towards the third concept. They liked that leaving a review would be much more effortless by using the semantic differential scales. One of the participants however pointed out that she would never have the energy to measure herself. She could also imagine getting anxiety from measuring herself. She suggested providing a range of models that the reviewer or reviewee could select among that would match the own body type. She hypothesized that by seeing an image of a model that represents your own body type would also make it easier to fill in the semantic differential scales correctly. The third participant liked the ability to be matched with reviews relevant for the own size but would still like the possibility to see how other people of other sizes had felt about the garment. She would also want to be guided through the measuring process.

5 Discussion

This chapter discusses the implementation of the methods and theories, as well as the findings generated through the design process. It also discusses the concept and future work.

5.1 Implementation of methods and theories

5.1.1 Theories

With the research question as a starting point, the literature study, interviews and observations occurred during the diverging phase of the project. The literature study provided insights to a great variety of reasons as to why consumers make apparel returns, mainly outlining returns occurring due to the lack of experiential information of garments. It also presented theories that could be applied to and investigated in the project and such as the two-stage decision process and the four types of visitors.

Initially, one of the intentions with the interviews and observations was to identify problem areas within the various types of visitors and the two-stage decision process. However, the project ended up investigating directed buyers and search visitors in the searching process the most. This was due to poor planning and anticipation of how the questions and structure of the interviews and observations would target each type of visitor and the different stages before, during and after the two-stage decision process. Even though the interviews and observations generated noteworthy insights, they did not cover all that was intended.

Since the insights about the directed buyers and search visitors in the searching process were plenty and valuable, it was obvious to continue investigating those in the converging phase. However, had the questions and the structure of the interviews and observations been better planned and anticipated, it is possible that the project could have proceeded another direction.

5.1.2 Interviews

Interviews allow discussion of more social and personal matters; however, it can be “dangerous” to assume and wait for participants to talk about what matter to them. What might be just as important is getting them to talk about for example tools that they don’t use in the situation that is being studied and why. Understanding what they discard and why might lead to insights that might actually point to the need to improve certain tools. Therefore, the participants were explicitly asked about thoughts and experiences of images, videos, product reviews, size guides and model sizes if they did not mention it themselves. In one of the interviews for example, the choice of asking about a function that the interviewee never mentioned led to the interesting finding that customer reviews are not always used to assess the fit of a garment because there is a lack of trust to the reviewer.

5.1.3 Observations

One of the benefits of conducting observations is because alterations can be avoided. In this project, the observations were conducted to find out what kind of sensory information the participants looked for and how they received it when shopping for apparel online. Using the think aloud method was an approach to better understand what the participants were doing, why and what they thought of what they saw. However, this approach might have made the participants aware and cautious of what they were doing, ultimately altering their output according to what they believe was the right thing to say, do or provide to the researcher. It is difficult to say if this happened during the observations and affected the outcome, however, it might be relevant for other designers to consider in the future.

5.1.4 Co-design workshop

The co-design workshop was a means to involve people from the target group in designing a concept and through that generate further insights into their needs and values. The decision to only invite females to the co-design workshop aimed to make people feel comfortable in sharing their experiences and thoughts about their bodies. Having males and females participate in the same workshop could make each party feel uncomfortable in sharing their experiences. Because females make up most of the return rates and to eliminate insecurities that could occur from involving both males and females, only females were invited. However, simply inviting females to participate does not guarantee that they will feel comfortable talking about their bodies in general. Many people are aware of their bodies and how they stand in relation to the society’s ideal body.

Furthermore, sketching is a method that promotes the visualisation of ideas. Visualising an idea instead of explaining it with words not only changes the way that the communication takes form but is also likely to change what is communicated. In the co-design workshop, the plan was that participants would communicate their ideas through sketches. This was anticipated to help them express themselves and help others understand what they were trying to convey. In the end, the participants did not draw to the same extent as expected. Even though they were encouraged to draw using stick figures, most of them expressed a feeling of angst. Even though sketching has been advocated as a great tool amongst and for designers, it is probable that there is a general fear of drawing amongst people who are not used to it or perhaps do not understand the motivation of it. Either way, some of the criteria that the participants in the co-design session generated were difficult to interpret because they had written them down as bullet points. To exemplify, they had expressed the desire to be provided with a customer review function that would be simple to fill out. When evaluating the criteria after the co-design workshop, one of the main problems was understanding how customer reviews could be designed in a way that the participants would consider to be simple to fill out.

5.1.5 Focus group

The focus group was used as a way to receive feedback on the concepts that were sketched after the co-design session. Receiving feedback on the concepts was a way to ensure that the needs and values of the target group had been interpreted correctly. Because only three people engaged in the focus group, their feedback needed to be considered with moderation. It also became evident that one of the participants had very strong opinions and was very certain of how she would modify the concepts. It is possible that this affected the other participants who became a bit guarded in expressing their opinions. It also raises the question of whom to listen and learn from and who’s’ opinion is the most valuable.

5.2 Main findings

The literature research and field work revealed that poor fit was a common reason for apparel returns. Despite a great range of methods and functions available on retailers’ websites aiming to help consumers assess the right fit, they do not seem to do the job too well. The methods and functions are failing in communicating how the different sizes of the garments respond to the consumers’ bodies and preferences. The variety of consumers’ preferences open up a discussion about what a “standard”, “normal”, “perfect”, or the “right” fit means. Finding a fit that suits the customer’s preferences does not seem to be about finding a size that goes on the body, but rather about how the form, size and material of the garment responds to various body parts and the customer’s preferences. A size does not automatically convey how the garment will fit, which is what retailers need to consider when trying to help consumers assess the fit of garments.

This project did not explicitly investigate if the directed buyers and search visitors engaged in systematic or heuristic information processing strategies. However, it suggested that the participants engaged in a systematic information processing strategy during the search process, as they were trying to assess the fit of a garment.

5.3 Concept

The third design concept generated (Figure 17) reflects a possible solution to consumers’ issue of not being able to assess how a garment will fit them. By giving consumers an idea of how the garment will fit on different body parts of relevance in a certain size, they are given more control over selecting a size that matches their preference of fit.

The concept also responds to the minimal cognitive effort that the participants would aspire to spend if they were to write reviews themselves. By implementing a semantic differential scale, the reviewers can spend less time and cognitive effort in determining how to express themselves. Retailers can also be more specific about what they want to elicit from the reviewers.

Ultimately, dealing with and storing measurements of peoples’ bodies give rise to data privacy issues. In today’s society, people have become more aware of data privacy issues due to companies storing, selling and profiting from data about people and their activities.

The fast creation of new apparel collections might also be an issue for the success of this concept. Gathering enough data and feedback to display reviews concerning the various bodies and sizes before the collections are replaced or removed might be an obstacle.

5.4 Future work

For the concept to be beneficial in the future, retailers might need to investigate how to make their customers leave reviews for the garments purchased. As the participants expressed, retailers could send out e-mails asking their customers to leave reviews after purchase, and perhaps offer something in return that could be converted to a discount. However, the downside of sending out e-mails is that customers could end up feeling bothered.

This project has mainly involved young women, and because of difficulties in recruiting participants, the variety of body types was limited. For the concept to be applicable and useful for all consumers of B2C apparel retailers, designers would need to involve consumers of all genders, body types and ages in future research.

Volumental, which measures and creates a 3D-scan of peoples’ feet, might disclose how the concept could advance in the future. By giving consumers the option to scan their bodies to extract measurements, the worry of extracting the wrong measurements could be avoided. However, people might gain or lose weight over time, resulting in the need to update their measurements every now and then. This needs to be considered even if the measurements are not extracted through a 3D-scanner.

Furthermore, this project has generated many findings that have not been elaborated on. It has become clear that discarding lenient return policies is not an option for many retailers, and therefore the future research needs to focus on how to minimize apparel returns without restricting the return policies. The literature study and field work has also disclosed that retailers could benefit from understanding the purchase and return behaviours of hedonic browsers. More specifically, there is a great potential in investigating how the waiting process of hedonic browsers can be managed in order to make consumers remember and perhaps create some sort of relation to the garments that they have purchased.

The experiential attributes used to discover pain points causing apparel returns of online purchases have also disclosed that novel ways of assessing material and colour of apparel online need to be studied and developed.

6 Conclusion

The aim of this project was to examine how the number of returns of apparel goods bought online can be reduced. Through a user-centred design approach, the project used literature studies, interviews, observations, a co-design workshop and a focus group to research the purchase and return motivations of B2C online apparel shoppers. The theoretical perspectives and knowledge provided by the literature study were used to frame the field for research. The research mainly involved young females aged 20-29 and explored directed buyers and search visitors in the stage before making a purchase.

The literature studies and field research revealed that one of the main issues of purchasing clothing online is assessing the fit of garments on distance. More specifically, consumers showed an interest in knowing how the different sizes of the garments respond to their preferences of fit.

7 References

Arvola, M. (2014). Interaktionsdesign och UX: om att skapa en god användarupplevelse. Studentlitteratur AB.

Asos. (2019a). Retrieved from https://www.asos.com/se/kvinna/

Asos. (2019b). Where can I find your size guide and care instructions? Retrieved 2019-05-04, from https://www.asos.com/customer-

service/customer-care/help/?help=/app/answers/detail/a_id/7102/country/gb

Bahn, K. D., & Boyd, E. (2014). Information and its impact on consumers׳ reactions to restrictive return policies. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 21(4), 415-423.

Bechwati, N. N., & Siegal, W. S. (2005). The impact of the prechoice process on product returns. Journal of Marketing Research, 42(3), 358-367.

Bold Metrics. (2019, April 22). A $500bn Opportunity Awaits - How Fit Technology Will Make The Fashion Industry More Sustainable. [Blog post]. Retrieved 2019-03-04, from http://blog.boldmetrics.com/a-500bn- opportunity-awaits-how-fit-technology-will-make-the-fashion-industry-more-sustainable/

Boozt. (2019). Retrieved from https://www.boozt.com/eu/en/women

Buxton, B. (2010). Sketching user experiences: getting the design right and

the right design. Morgan kaufmann.

Claudio, L. (2007). Waste couture: Environmental impact of the clothing industry.

DiCicco-Bloom, B., & Crabtree, B. F. (2006). The qualitative research interview. Medical education, 40(4), 314-321.

Fichter, K. (2002). E-commerce: Sorting out the environmental consequences. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 6(2), 25-41.