MASTER THESIS WITHIN: Business Administration NUMBER OF CREDITS: 30 ECTS

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: Civilekonom SUPERVISOR: Timur Uman

AUTHORS: Oskar Johansson

Johan Ljungberg

JÖNKÖPING: May 2020

How auditors and family

firms co-create value

Master Thesis in Business Administration Authors

Oskar Johansson Johan Ljungberg Title

How auditors and family firms co-create value Supervisor

Timur Uman Date

2020-05-18 Abstract

Background: The relationship between family firms and auditors is not a topic that is very well examined. This is also a relationship that is extraordinary because they have different aims with the relationship. Since the family firms seek for long and close relationships while the auditor needs to maintain their independence. There have also been several scandals in the past between family firms and their auditor where the relationship has become to close.

Purpose: The purpose of this paper is to examine the auditor’s role in family firms, how value is co-created and what value that is co-created when they interact with each other.

Method: To answer the research question the data in this study is collected through semi-structured interviews. The interviews were performed and inspired by previous studies which we developed a framework on to have as a guideline during the interviews. The participants in the study were three family firms and their respective auditor and the participants were located in the same geographical area.

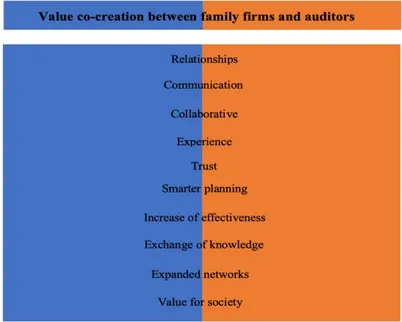

Findings: In this study, we have focused on how and what value family firms and auditors co-create when they interact with each other. The study suggests important aspects of the family firm and auditor relation to facilitating the value co-creation process. The aspects that were revealed as important were the relationship, communication, collaborative, trust, and experience from the auditor. The study also investigated which values family firms and auditors

co-create, these were smarter planning, increase of effectiveness, exchange of knowledge, expanded networks, and value for society.

Keywords

Family firms, Audit firms, Auditor, Socioemotional wealth, Profession theory, Co-creation, Value.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank our supervisor Timur Uman during this master thesis. Without him would this master thesis not been possible, we have appreciated his guidance and support during this study. His engagement, critique and encouragement have helped us with our research, and we are very grateful for that.

We also want to thank all participants included in our study. All the representatives from the family firms and their auditors that gave their time for an interview that generated us valuable information and insights for this study.

Finally, we would like to thank our families and friends who have supported us during the whole process.

Jönköping, 18/05/2020

Oskar Johansson Johan Ljungberg

TABLE OF CONTENT

1. INTRODUCTION ... 1 1.1BACKGROUND ... 1 1.2PROBLEMATIZATION ... 5 1.3PURPOSE ... 9 1.4RESEARCH QUESTION ... 9 2. LITERATURE REVIEW ... 102.1VALUE FOR FAMILY FIRMS ... 10

2.1.1 The socioemotional wealth theory ... 10

2.1.2 A fit between goals, resources and governance structures ... 11

2.2VALUE FOR AUDITORS ... 12

2.2.1 Profession theory ... 12

2.2.2 Auditor independence ... 14

2.2.3 Client satisfaction ... 15

2.3HOW THE AUDITOR CREATES VALUE FOR THE FAMILY FIRM ... 18

2.3.1 The auditor’s role for the firm ... 18

2.3.2 The auditor’s role for the family firm and added value ... 20

2.4HOW THE FAMILY FIRM CREATES VALUE FOR THE AUDITOR ... 22

2.4.1The auditor-client relationship ... 22

2.5CO-CREATION ... 24 2.5.1 Service logic ... 25 2.5.2 Framework ... 26 3. METHOD ... 27 3.1RESEARCH PHILOSOPHY ... 27 3.2RESEARCH APPROACH ... 27 3.3CHOICE OF THEORY ... 28 3.4CRITICISMS OF SOURCES ... 29

3.5RESEARCH STRATEGY:INTERVIEWS ... 30

3.6DATA COLLECTION ... 31

3.7INTERVIEW GUIDE ... 31

3.7.1 Questions asked to the family firms ... 32

3.7.2 Questions asked to the auditors ... 33

3.8SAMPLE SELECTION ... 35 3.9DATA ANALYSIS ... 36 3.10RESEARCH QUALITY ... 37 3.10.1 Credibility ... 37 3.10.2 Transferability ... 37 3.10.3 Dependability ... 38 3.10.4 Confirmability ... 38 3.11ETHICAL CONSIDERATION ... 38 4. EMPIRICAL FINDINGS ... 40

4.1THE FAMILY FIRM PERSPECTIVE ... 40

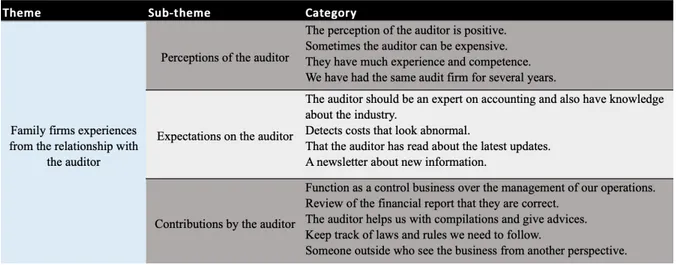

4.1.1 Theme: Family firms experiences from the relationship with the auditor ... 40

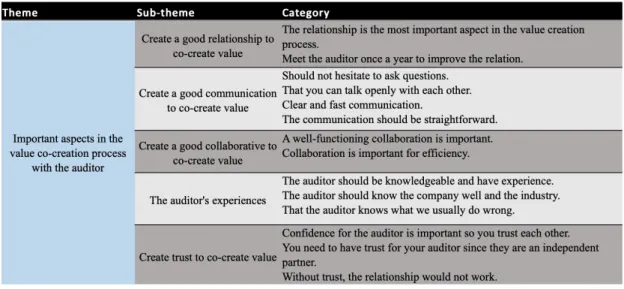

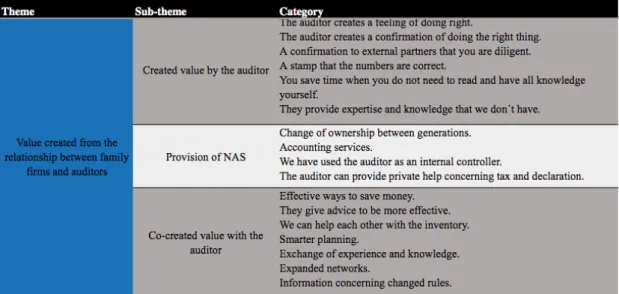

4.1.3 Theme: Value created from the relationship between family firms and auditors ... 45

4.2THE AUDITOR PERSPECTIVE ... 48

4.2.1 Theme: The auditor’s relationship with family firms ... 48

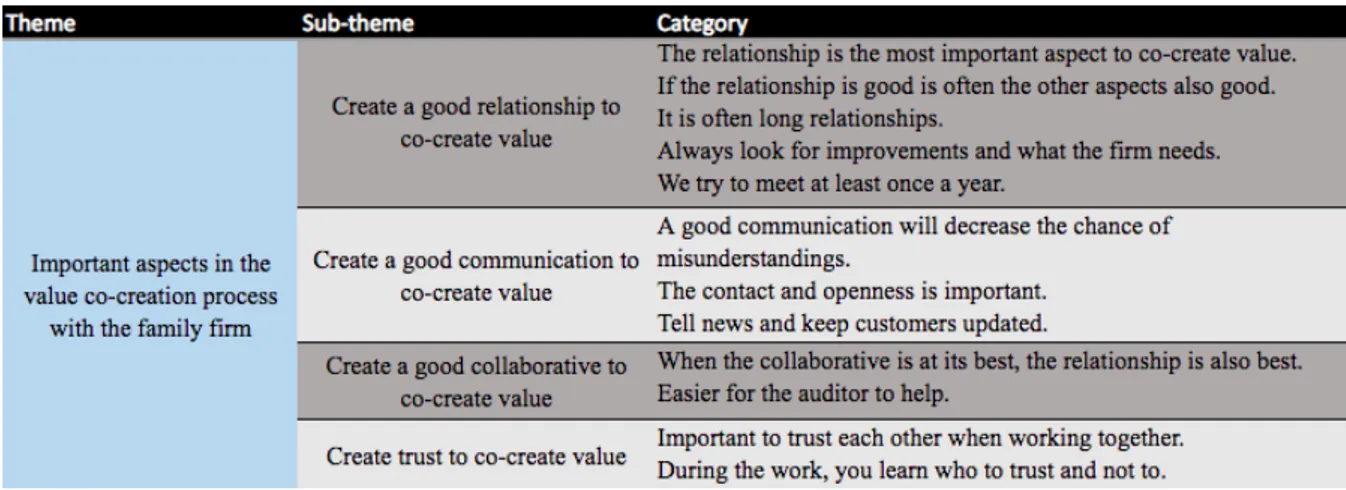

4.2.2 Theme: Important aspects in the value co-creation process with the family firm ... 51

4.2.3 Theme: Value created from the relationship between family firms and auditors ... 53

5. ANALYSIS ... 58

5.1NEW FRAMEWORK ... 62

6. CONCLUSION ... 63

6.1THEORETICAL CONTRIBUTIONS ... 64

6.2PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS ... 65

6.3LIMITATIONS/CRITICAL REFLECTIONS ... 66

6.4FUTURE RESEARCH ... 67

7. REFERENCE LIST ... 68

8. APPENDIX ... 81

8.1INTERVIEW GUIDE ... 81

8.1.1 Questions asked to the family firms ... 81

8.1.2 Questions asked to the auditors ... 81

8.2INFORMED CONSENT ... 82

Figures

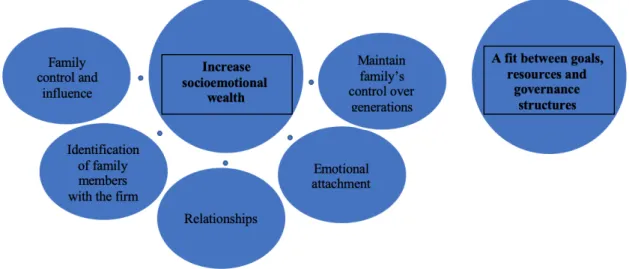

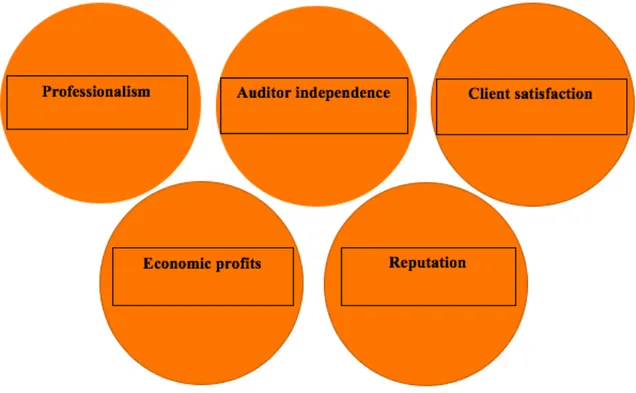

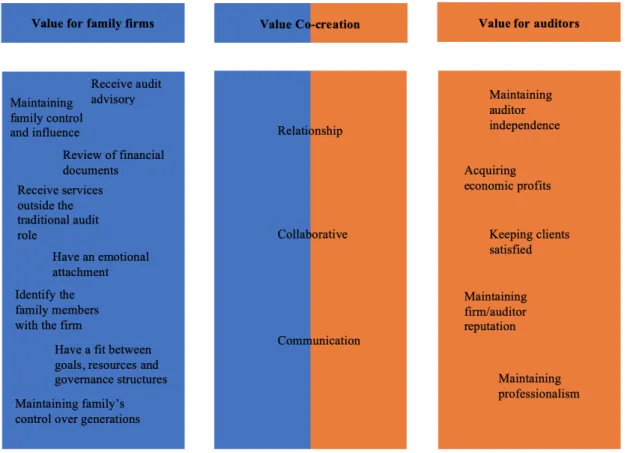

Figure 1: Value for family firms ... 12Figure 2: Value for auditors ... 18

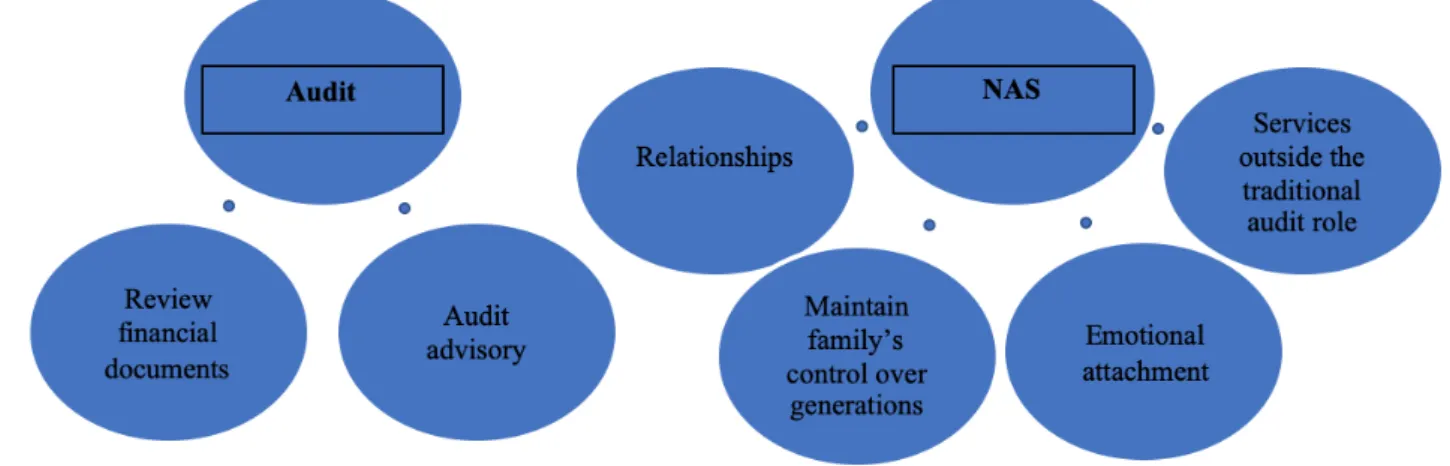

Figure 3: Value auditors create for family firms ... 22

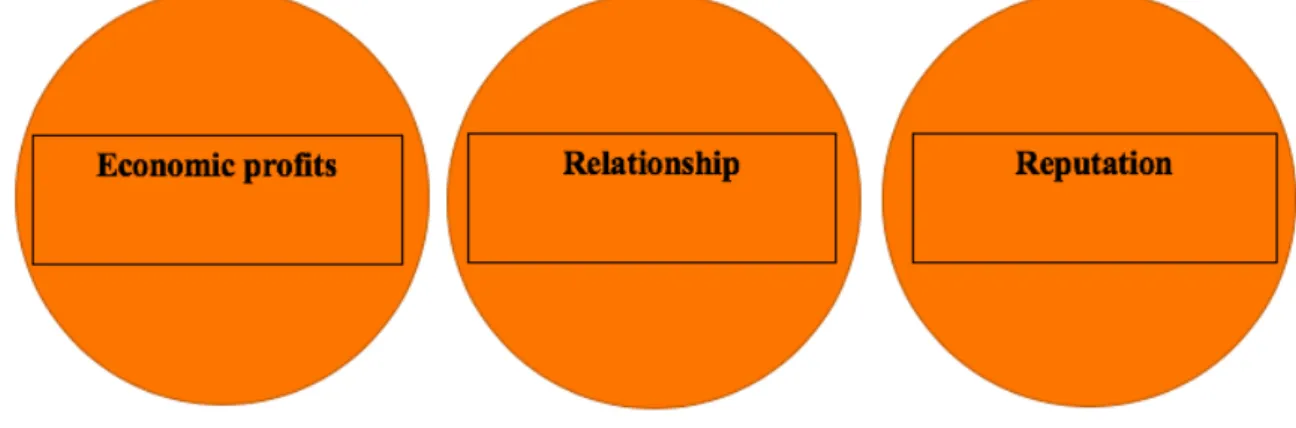

Figure 4: Value family firms create for auditors ... 24

Figure 5: Family firms and auditors value co-creation ... 26

Figure 6: Family firms experiences from the relationship with the auditor ... 43

Figure 7: Important aspects in the value co-creation process with the auditor ... 45

Figure 8: Value created from the relationship between family firms and auditors ... 48

Figure 9: The auditor’s relationship with family firms ... 51

Figure 10: Important aspects in the value co-creation process with the family firm ... 53

Figure 11: Value created from the relationship between family firms and auditors ... 57

1

1. Introduction

In this chapter, the background of family firms and auditors will be presented and their relationship to each other. Additionally, we will present the problem and purpose of this thesis, what we aim to explore, and why it deserves to be researched.

1.1 Background

The development of auditing as a profession started to shape in the middle of the nineteenth century in Sweden. In 1848 the Companies Act established a new way to raise capital, which was through external investors. The investors needed some security that the capital they invested was handled in a convenient way, which led to the first type of auditing completely without guidelines of how it should be performed. The creation of the auditor profession can be linked to the separation of investors and managers, in other words, ownership, and control (Schön, 2012). In 1895 the Companies Act determined that limited companies must appoint at least one auditor. Shortly after this in 1899 the Swedish Association of Auditors (Svenska Revisorssamfundet, SRS) was founded. In 1912 SRS decided that auditors should be authorized (SRSa, Protocol 9/10 1900, §3; “En återblick på de 25 gångna åren” [A look back on the past 25 years], 1925, pp.164–5). These authorized auditors created their own association in Sweden 1923, the Swedish Institute of Authorized Public Accountants ( Föreningen Auktoriserade Revisorer, FAR (FARa, Protocol 22/1 1931). As a result of events such as the Kreuger crash, it highlighted the importance of auditor independence and standards with minimum requirements to follow for auditors. This together with ethical rules was created in the middle of the twenty centuries (FAR 75 år – en rapsodisk skildring av utvecklingen 1923– 98 [The Swedish Institute of Authorized Public Accountants 75 years – a rhapsodic story of the development 1923– 98], 1998, p.17).

It took a long time before SRS and FAR started their cooperation in the 1970s. Because of many foreign-owned subsidiaries that came to Sweden during the 1970s, the Swedish accounting firms were forced to contact international accounting firms in order to perform their audits correctly. Simultaneously FAR was forced to take inspiration from outside Sweden to catch up with international auditing practices (FAR, Protocol 23/2 1970). The inspiration from foreign countries led to a shift from the old audit model with item-to-item checking to a more modern approach with a focus on responsibility, established rules and systematically arranged accounting systems (FAR 75 år – en rapsodisk skildring av utvecklingen 1923–98 [The Swedish Institute of Authorized Public Accountants 75 years – a rhapsodic story of the

2

development 1923– 98], 1998, p.16). Later in 1975, the workload increased for auditors because of a newly released Company Act that required annual reports to be examined in line with Generally Accepted Auditing Standards (Öhman, Häckner, Jansson & Tschudi, 2006). Because of different economic crimes in firms, it became mandatory for limited companies to have a minimum of one authorized auditor in 1978. During the 1980s corporate scandals occurred which resulted in that auditors being forced to inform the government if they had serious suspicions about a company, such as exports of unlawful war equipment (Larsson, 2005).

In 2012 a proposal was established which changed the audit obligation in Sweden. This change involved approximately 250 000 companies, which corresponded to around 70 % of the private limited companies in Sweden. The reason behind the decision was that companies themselves should decide which consultants they have a need for. Those who came up with the proposal believed that many companies wanted to continue having an auditor since they often can add value beyond the audit (Prop. 2009/10:204). Carrington (2010) argues that the decision also was made to facilitate for small limited companies to help them reduce their costs. The principal rule after the amendment is that all firms which are limited companies should have an auditor. For all public entities, it is mandatory to have an auditor, but for private entities there are exceptions. A company needs to fulfill at least two of the following three requirements for not having an auditor. The company must have no more than three employees, the total turnover should not exceed three million SEK and the assets should be below 1,5 million SEK (Bolagsverket, 2020). After the audit obligation was abolished in Sweden the number of companies that have an auditor has decreased, which has reduced the auditor’s traditional audit work (Brännström, 2014).

The auditor’s traditional role is to review and secure information in companies, it also includes giving advice to the firm related to the review process (Öhman, 2007). For instance, advice means that the auditor informs the company about misstatements to secure that the information that is stated in the annual report is correct (Svanström, 2004). The auditor needs to be independent, if an auditor is not truly independent the auditor’s opinions on the financial statement will be of no value. In that case, it will lead to stakeholders have less confidence in financial statements and lead to more uncertainty in the capital market (Firth, 1980). An audit firm can also provide the company with other supplementary advice such as separate services that are called a non-audit service (NAS) which is more common today. When the auditor performs any NAS for a company it could provide a real or perceived threat against the

3

auditor’s independence (Beattie & Fearnley, 2003). The auditor is seen to have an important role for micro, small and medium-sized companies and their survival and development. Depending on different corporate governance sets the role of the auditor can be different and more important in family firms since their need for advice often is larger. Other roles that an auditor can have for a family firm than the traditional role as a reviewer can be to mediate, a person to ask questions and get different advice from and handle different conflicts in the firm, but also roles as advisor and conveyer (Collin, Ahlberg, Broberg, Berg & Karlsson, 2017). This means that the auditor in some cases steps outside their traditional role and the risk of not being independent is threatened when creating any NAS to the family firm. It can be problematic since it is important for the auditor to always be independent (Lai & Krishnan, 2009; Fontaine, Letaifa & Herda, 2013). This makes the auditor more influential in family firms. From the family firm’s perspective, there are seen to be many advantages of having an auditor (Barbera & Hasso, 2013). Since family firms often expect that the audit firm performs any NAS for the company which generates some added value that the client does not pay for (Jaffe, Lane, Dashew & Bork, 1997).

The biggest part of the companies in Sweden is family firms. In 2010 a study was made that showed almost 90% of the engaged companies are family firms in Sweden. Where different business forms were included such as limited companies, sole traders, trading companies, and limited liability companies. Since family firms have that big part of the market, they are important since a big part of the population has work because of the family firms and they contribute much to the Swedish GDP (Andersson, Karlsson & Poldahl, 2017). Family firms often have different objectives and characterizes compared with non-family firms (Collin & Ahlberg, 2012; San Martin-Reyna & Duran-Encalada, 2012).

The objective of a family firm is that the company should be managed through family members and it can be through different generations and the purpose is to increase the profit for the family members. A family is described as individuals with common ancestry, a marriage with someone outside the common ancestry or adoption (Collin & Ahlberg, 2012; Stewart, 2003). To be defined as a family firm the family needs to have control of the firm, be the majority owner, and have the majority of the votes (Villalonga & Amit, 2006; San Martin-Reyna & Duran-Encalada, 2012). The board and the different management positions are dominated by family members, often are these positions monopolized by only family members (Lane, Astrachan, Keyt & McMillan, 2006).

4

The characterizes of family firms are that they often are built upon and dependent on trust, reputation and to have long relationships (San Martin-Reyna & Duran-Encalada, 2012). It is also described that family firms have a different relation to their auditor compared with non-family firms. A difference between non-family firms and non-non-family firms is that non-family firms are seeking for more long-term financial results and investments (Miller & Le Breton-Miller, 2006; San Martin-Reyna & Duran-Encalada, 2012). Based on this, it is also expected that the relationship with the auditor will be deeper and over a long period of time (Salvato & Moores, 2010; Collin et al., 2017).

The relationship between auditors and family firms can to some extent be different from the relationship between auditors and non-family firms. According to Wan Ismail & Kamarudin (2012), auditors have a higher risk of not being independent in family firms. The meaning of an auditor having a higher risk is that auditor’s independence has a greater chance of being threatened when working with family firms. Independence is one important part of the auditor profession and something valuable for them, it is important for the auditor’s reputation, a good reputation is necessary for both the auditor and the family firm. But it is stated when NAS exists, the risk is higher that the auditor independence is threatened (Boyd, 2004). The expectations of reporting an error in the audit can be an indication of lower independence and are expected to be less if the NAS has a positive impact on the audit firm (Collin et al., 2017). In the past there have been some scandals were the relationship between the auditor and the family firm has been to close. This is not a unique scenario for Sweden, it is a global phenomenon which can lead to scandals (c.f., Gates, Lowe & Reckers, 2006). One example of a scandal was between auditors on KPMG and companies owned by the Gupta family in South Africa. The auditors on KPMG had, for instance, missed serious things classified as red flags in their audit of one company owned by the Gupta family. In emails that were leaked between the KPMG office in South Africa and the company Linkway Trading owned by the Gupta family, it was revealed that they allowed the company to place the costs for a wedding as a business expense in the company. The consequences of this were that KPMG lost contracts with several audit clients. They were also reviewed by the South African regulatory body IRBA, where they risked being removed from the audit register in South Africa (Shoaib, 2017). One of the reasons for this scandal could be that KPMG had audited companies owned by the Gupta family for 15 years, which may have affected the auditor independence because of a to

5

close relationship between them. In order to counteract this kind of situation, new regulations have been released which might be of special interest for family firms. To minimize the risk of a to close relationship between the auditors and the audit clients have rules been created concerning mandatory audit rotation, however not only valid for family firms. In 2006 the European Union released a directive to ensure that all member states need to change their key audit partners within a period of maximum seven years in public interest entities (European Parliament and of the Council, 2006). Later in 2014, a new directive was released which included a new statutory audit framework. This directive changed the earlier rotation period of key audit partners from seven to ten years in public interest entities (European Parliament and of the Council, 2014). These regulations might have the potential to solve the higher risk auditors have to threaten their independence in family firms according to Wan Ismail & Kamarudin (2012).

Another well-known scandal is the “Enron” scandal. Enron was not a family firm, but it is an example of where the relationship between the audit firm and the company was to close, which resulted in a scandal. It is stated that the accounting firm Arthur Andersen LLP that oversaw Enron’s accounts was a major player in the Enron scandal and that they had a close relation to each other. At that time, they were one of the five biggest accounting firms in the United States and they were well known for high standards and quality risk management. During that time Enron had very poor accounting practices but Arthur Andersen offered its stamp of approval despite this in many years and signed the corporate reports. But in 2001 started a couple of analysts to see the big problems in Enron’s results and in the entity’s transparency. Arthur Andersen was in June 2002 found guilty for obstructing justice for hiding and destroying thousands of important documentations related to Enron to conceal it from the Securities and Exchange Commission (Investopedia, 2019). During the years it was also shown that Enron was paying very high fees to Arthur Andersen (Los Angeles Times, 2002).

1.2 Problematization

Value is something that can be created in many different ways and it can also have different meanings. Value can be defined as the monetary, material, or assessed valuation of either an asset, good, or service. Value is also attached to other concepts such as shareholder value, fair value, book value, and the value of the firm (Investopedia, 2020). It is also important to understand that value is defined differently in family firms and audit firms. In the problematization, we will look at what represents value for family firms and for audit firms independent from each other and then in relation to each other. When auditors perform audits

6

on family firms, they add value to the company through different services. The family firm also creates value for the audit firm in some different ways. Auditors and family firms can also create value together when they interact with each other, called value co-creation (Prahalad & Ramaswamy, 2004).

When looking at what represents value for a family firm, the socioemotional wealth theory is appropriate to take in the act. Value for family firms is to pursue non-financial goals that provide the family firm with socioemotional wealth. To provide socioemotional wealth to the family firm the firm needs to be controlled by the family. It is supposed that socioemotional wealth increase with the extent of current control, duration of control, and the idea for transgenerational control (Zellweger, Kellermanns, Chrisman & Chua, 2011). The owners of the family firm pick up socioemotional wealth from different sources. The owners feel that they are linked to the firm and that creates an emotional bond to the firm. This emotional bond has a big impact on how the family owners run the firm. The owners feel identified to the family firm and therefore they value the public image that the firm has since it reflects on the

family (Kalm & Gomez-Mejia, 2016). According to Gomez-Mejia, Cruz, Berrone & De Castro

(2011), family firms value their reputation and image of the firm more than short term advantages of accounting practices that have the chance to decrease socioemotional wealth. Another aspect that is valuable for family firms is that they like to have long and close relationships. For instance, it can be mutually important for the family firm and the audit firm to have a long and good relationship with each other. Since they can perform additional value to each other and the auditor is of much value for the family firm since it can influence the family firm’s survival (Collin et al., 2017).

When looking at what creates value for family firms, prior research has mostly been focusing on one single perspective. According to Drazin & Van de Ven (1985), they explain to not only look on one perspective and instead try to combine the importance of the fit between different

perspectives. For instance, Kammerlander, Sieger, Voordeckers & Zellweger (2015) propose

this prior research can be divided into three different perspectives: family-influenced goals, resources, and governance. In family firms, value creation can be created throughout a fit between goals, resources, and governance structures where most probably all these three aspects are affected by the family. If there is a misfit between the goals the family firm has, and the firm’s output produced by the resources within the governance structure the family firm has, then the value that is created will not be valuable value for the family firm (Kammerlander et al., 2015).

7

In audit firms, the definition of value differs from the one in family firms. Auditors are in their profession classified as professionals (Brante, 1988). It is therefore valuable for auditors to keep their professionalism by following the laws and rules they have (Brante, 2009). A part of the auditor’s professionalism is to be independent in their work. The auditor should be professional and objective in their review and assessment (Ponemon & Gabhart, 1990). It is auditor’s independence that has been argued to have a risk of being threatened when auditors interact and perform services for family firms. Auditor independence is important for the auditor’s reputation and something valuable for them and their audit firms (Wan Ismail & Kamarudin, 2012). Another aspect of value in audit firms is customer satisfaction. In auditor’s role as professionals have value creation for their clients becomes an important part of their work. The reason for this is that globalization of the audit profession has made it more competitive, this has made auditors more service orientated in order to maintain a high audit quality (Clow, Stevens, McConkey & Loudon, 2009). The abolishing of the audit duty has also influenced why auditors became more service orientated since they got less to do in their traditional role (Brännström, 2014). This has contributed to the commercialization in the audit profession where new services have been developed. Authors have argued that auditors, therefore, have become more interested in making economic profits from services outside the traditional auditor role (Kaplan, 1987).

When the auditor performs the audit, the family firm is the client that the auditor generates value for. According to Smith and Colgate (2007) value can be described as what they receive relatively to what they give up. This means that the value for the family firm emerges when the benefit from the audit is more worth than the cost for it. According to Løwendahl, Revang & Fosstenløkken (2001), audit firms exist in order to create value for their clients by using the company’s resources to be able to solve problems and perform tasks. They argue that professional service firms can create value in two different ways. The first one is by creating value for their client and the other one is by creating value for the client’s shareholders. The services that auditors perform can be categorized into three parts, services connected to the traditional audit service, NAS, and advice. The traditional audit service means that the auditor should review and secure information in companies, this role also includes giving advice to the firm concerning things that were found during the review process (Öhman, 2004). For example, advice means that the auditor informs the company about misstatements to secure that the information is correct (Svanström, 2004). In addition to these three services, there are some

8

further roles that the auditor can have as mediating and conveying which can be seen as value for the family firm.

According to Broberg (2013), auditors describe high-quality auditing as when they create value for the auditee in addition to monitoring. Not necessarily by providing NAS to the firm, giving advice, and making proposals for improvement can also be a part of the audit task. This is advice that has nothing to do with the review process, it can be seen as a separate service. The result from Fontaine & Pilote (2012) showed that the majority of the companies investigated wanted the auditor to contribute with essential information and services in addition to the audit. Studies have also shown that family firms have a larger need for guidance than non-family firms (Barbera & Hasso, 2013). This could indicate that family firms have a need for NAS, even if it can threaten the auditor independence (Svanström & Sundgren, 2011). All services which are not related to the audit is defined as NAS, it could be services related to tax, consultancy, and valuation. The NAS is also more favorable for auditors in Sweden to perform compared with auditors in the European Union. Since the Parliament and the council of the European Union released a directive in 2014 which mentioned some NAS as not appropriate to perform (European Parliament and of the Council, 2014). While the Swedish auditor law has some exceptions when it comes to NAS, in paragraph 21b§ auditors get permission to under some conditions perform NAS which was mentioned as inappropriate to provide by the European Parliament. When the audit firm performs services for the family firm, they also

receive value from the family firm through the payments from the executed services (Carcello,

Hermanson, Neal, & Riley, 2002).

When the family firm interacts with the auditor there is a value that also can be created through co-creation. Since the family firm and auditor can have similar parts that represent value for them, given the empirical evidence for a closer relationship between the auditor and family firms (Fontaine & Pilote, 2012). The definition of value co-creation is that both the provider and the customer perform actions, which means that both the auditor and family firm contribute in the process of value creation. The value that is co-created from a business-to-business perspective is a topic that has a lack of prior research (Grönroos & Voima, 2013). The literature that exists about co-creation states that the important parts in the value co-creation process are the quality of the interaction, the collaborative and effective communication between the involved parts which in this case is the family firm and the audit firm (Lenka, Parida & Wincent, 2016; Knechel, Thomas & Driskill, 2015; Vargo & Lusch, 2004. Nguyen, Kohda, Umemoto & Nguyen (2015) have developed a framework for how value can be created through

9

co-creation in auditing. The framework consists of the interplay between four factors in the auditing process, the auditors, clients, professionals, and the client’s stakeholders. All four components are involved or have an interest in the auditing process. The audit is about the intersection between these four factors, it is the balance between them which creates value. The family firm has a view about what value they and the audit firm bring during the process and the audit firm has another or similar view about what value they and the family firm bring during the process. Here it exists an expectation gap between the family firm and the audit firm. We will investigate how value is co-created in the relationship between family firms and auditors and what value that is co-created.

1.3 Purpose

The purpose of this paper is to examine the auditor’s role in family firms, how value is co-created and what value that is co-co-created when they interact with each other.

1.4 Research question

10

2. Literature Review

In this chapter is a review of existing literature presented where we discuss value for family firms, value for auditors, how the auditor creates value for the family firm, how the family firm creates value for the auditor and co-creation. Finally, we come up with a framework where values for family firms, value co-creation, and values for auditors are presented. This is identified from the existing literature and it will be the basis of our empirical data collection.

2.1 Value for family firms

2.1.1 The socioemotional wealth theory

The socioemotional wealth theory represents what value is for family firms. According to Gomez-Mejia, Haynes, Nuñez-Nickel, Jacobson & Moyano-Fuentes (2007), socioemotional wealth is defined as “non-financial aspects of the firm that meet the family’s affective needs, such as identity, the ability to exercise family influence, and the perpetuation of the family dynasty”. From the socioemotional wealth perspective, we can see that family owners need to take a lot of important decisions that will have an effect on their socioemotional wealth and they need to assess how these decisions will impact the socioemotional wealth (Berrone, Cruz, Gomez-Mejia & Larraza-Kintana, 2010). For family firms it is important to preserve the socioemotional wealth for the family owners, the family owners’ strategic choices are often influenced by the preserved logic in the socioemotional wealth (e.g., Gomez-Mejia et al., 2007; Berrone et al., 2010). The socioemotional wealth perspective proposes that family firms mostly are inspired and committed to maintaining their socioemotional wealth. When announces are framed negatively by the family owners and it generates a loss in the socioemotional wealth, the family owners often prefer to choose risky economic actions to maintain the socioemotional wealth (Berrone, Cruz & Gomez-Mejia, 2012).

Berrone et al., (2012) have developed five dimensions that socioemotional wealth can be divided into that show different values in family firms. It is said that these five dimensions will have different power on the family firms depending on the family owners’ priorities. The five dimensions Berrone et al., (2012) have come up with are 1. family control and influence; 2. identification of family members with the firm; 3. relationships; 4. emotional attachment; and 5. renewal of family bonds to the firm through dynastic succession. The first dimension is about the influence and control the family members have on the firm. To continue to have the preserved socioemotional wealth and create value, the family members need to have the influence and control of the family firm (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2007). One element that differs

11

between different family firms is the members exert control in different strategic decisions (Chua, Chrisman & Sharma, 1999; Schulze, Lubatkin, & Dino, 2003b). The control can be held for instance by the CEO or the chairman of the board in direct control or more subtly, like choosing top management teams. In a family firm, it is normal that a family member has more than one role and position in order to have more control over the firm (Mustakallio, Autio & Zahra, 2003). The second dimension is about the close relationship between the family and the firm. Prior research shows that the connection between the family and firm leads to a unique identity in the family firm. Therefore, the image and reputation are valuable for how they are being seen since it reflects on the family (Berrone et al., 2010; Dyer & Whetten, 2006). The third dimension is about family firms’ social relations that are valuable for them. Prior research made by Cruz, Justo & De Castro (2012) shows that family firms like to evolve relationships that can bring collective advantages that are made in close networks, collective social capital, and relational trust (Berrone et al., 2012). The fourth dimension is about the role the emotions have within the family firm. The emotional bond between the family and firm will influence how they run the firm and make different decisions depending on what they prefer in different strategic decisions (Berrone et al., 2012). The fifth and last dimension that is very valuable is to let the business move on for future generations in the family to continue to be operative in the long term which also increases the socioemotional wealth. It is valuable and a goal for the owning family to let it move on to the next generation and not only be seen as a heritage and an asset that can be sold (Berrone et al., 2012).

These five dimensions of socioemotional wealth show what value is in family firms. All these five different dimensions show how socioemotional wealth can influence different decisions to create value and increase the socioemotional wealth.

2.1.2 A fit between goals, resources and governance structures

According to Kammerlander et al. (2015), value creation in family firms can be created throughout a fit between goals, resources, and governance structures where most probably all these three aspects are affected by the family. The goals are influenced by the family and affect the way the organization behaves and creates value (Tagiuri & Davis, 1996). The second aspect that prior research has focused on is resources. The resources make it possible for family firms to create value. Researchers have stated that competitive advantages are created by the family’s engagement (Habbershon & Williams, 1999: 1). Examples of these competitive advantages in the family firms are the social capital (Pearson, Carr & Shaw, 2008), human capital (Sharma, 2008) and it can also be reputational capital (Sieger, Zellweger, Nason & Clinton, 2011). The

12

third aspect of value creation is depending on the governance structure within and around the company (Kammerlander et al., 2015). Because most probably is the family affecting the organizational structure (Corbetta & Salvato, 2004) and executive compensation (Gomez-Mejia, Larraza-Kintana, & Makri, 2003), that have been seen to affect the efficiency of the organization.

If the family firm only focuses on one of the three aspects or if there is a misfit between the goals the family firm have and the firm’s output produced by the resources within the governance structure the family firm has, then the value that is created will not be valuable value for the family firm. They need to fit each other otherwise it will not be positive, for instance, if a company has built up likely with resources and if these resources do not fulfill the conditions of the company’s context the value created will be unlikely. Depending on different family firms, they have different strategies and prioritize different between goals, resources,and governance structures (Kammerlander et al., 2015).

To summarize what value is for a family firm it can be categorized into two main categories: 1. To increase socioemotional wealth that is divided into five different parts and 2. To have a fit between goals, resources and governance structure that is affected by the family.

Figure 1: Value for family firms 2.2 Value for auditors 2.2.1 Profession theory

The profession theory can be used to explain what value is for auditors. Auditors can be classified as professionals. Professionals are people that have an important role in society and bases their authority on scientific knowledge. Professionals have together the most integrative

13

functions in society and have the leading role when it comes to innovations in economics among other things (Brante, 1988). For instance, auditors, teachers, and lawyers are examples of professions (Broberg, Umans & Gerlofstig, 2013). New professions can be created because the development of what is classified as a profession is steered by changes in society (Agevall & Jonnergård, 2013). The boundary between professions and non-professions is not clearly defined according to Artsberg (2003). But it exists guidelines for what the basis of a profession is, Agevall & Jonnergård (2013) means that professions need to have trust from the community in the work and judging they perform. A presumption for this is that people outside the profession should not be able to assess the quality of the work performed, this should only the professionals be able to do. However, when it comes to assessing the audit quality the traditional professional values have been jeopardized because of the increasing focus on market orientation. This has made auditors in their role as professionals to have a larger focus on how they treat and are perceived by clients (Broberg, Umans, Skog & Theodorsson, 2018). Value creation for clients is one way for auditors to increase the audit quality and customer satisfaction (Fontaine & Pilote, 2012; Herda & Lavelle, 2013)

Researchers about professions have struggled to define which characteristics people in a profession need to have (Brante, 2009). Most of the modern definitions of profession characteristics are the connection to higher formal education since the university generates a diploma which is seen as the way into a profession. One often-used definition of professions and their characteristics is the one by Millerson (1964) which includes certain steps.

1. Use of skills based on theoretical knowledge 2. Education and training in these skills

3. Professional skills are guaranteed through exams 4. An action ethic that guarantees professional integrity 5. Provision of services for the public good

6. A professional association that organizes members

7. The members have a sense of identity and share common values

The audit profession corresponds with this characteristic to be classified as a profession. Auditors are considered to be neutral representatives with a high level of knowledge and skills from a formalized education (Artsberg, 2003). Furthermore, to be an authorized auditor, an additional specific auditor test is mandatory to implement together with several years of work experience (FAR, 2019). Auditors also have rules and frameworks that they are expected to

14

follow which corresponds with the profession theory (Brante, 2009). Auditors have rules to follow created by FAR which has to do with ethics in the relation they have with clients and society. The state licensing of the audit profession is an important thing that makes the auditors to be considered as professions. The auditors themselves believe that the most important thing for why they are considered as professionals is because they have unwritten action norms (Artsberg, 2003). It is important that auditors follow the laws and rules within the profession to maintain their professionalism and to retain the audit profession’s status (Brante, 2009). Since the audit profession corresponds with these steps, the profession theory can be used to explain what value is for auditors. Because auditors want to keep their professionalism when they perform their work. One part of the professionalism is to be independent in the work the auditor performs (Ponemon & Gabhart 1990).

2.2.2 Auditor independence

Auditor independence is a big part of auditor’s work and professionalism. Auditor independence implies that the auditor should be objective when they perform their review and assessment of companies (Ponemon & Gabhart, 1990). The Swedish auditor act 20§ define auditor independence as “An auditor shall carry out his or her audit business assignments with independence and be objective in his or her opinions. The audit business shall be so organized that the auditor’s impartiality, independence, and objectivity are ensured”. In order to maintain independence, the auditor is not allowed to have any financial interest in the company they audit or a close relationship with the client (Auditor act 21§). Auditor independence is important to maintain, so the auditor ensures that the company’s information is reliable since stakeholders are interested in this information (Carrington, 2010). It exists several studies that imply that this independence can be threatened (e.g., Fontaine & Pilote, 2012; DeAngelo, 1981; Svanström & Sundgren, 2011). Especially in family firms do the auditor has a higher risk of not being independent (Wan Ismail & Kamarudin, 2012). The provision of NAS is one situation where the auditor’s independence can be threatened (Svanström & Sundgren, 2011). Because the provision of NAS can be seen as a financial interest in the client because the audit firm receives non-audit fees that can make them financially dependent on the client (DeAngelo, 1981). The effect could be that the auditor’s willingness of finding misstatements in a client’s financial statement is reduced and that the audit opinion is not completely accurate (Kinney, Palmrose & Scholz, 2004).

According to Fontaine & Pilote (2012) do clients often have a demand for services that create value for them and close and long relationships. According to Bamber & Iyer (2007) do the

15

probability of the auditor risking their independence increase when the relationship is close with the client and it decreases when the affiliation is strong with the profession. So, the auditor must be careful when performing services outside the review, so they do not end up in situations where they feel a stronger affinity with the client than the audit firm (Warren & Alzola, 2009). There has been evidence that longer relations between the auditor and the client will lead to more value created by the auditor. But if the relationship between the auditor and client becomes to close and they have a lot of trust for each other can the auditor’s professionalism be questioned (Rennie, Kopp & Lemon, 2010). Therefore, have EU directives regarding statuary audit rotation been released to reduce the risk of the auditor threatening their independence and professionalism (European Parliament and of the Council, 2014).

However, the auditor’s review cannot be made without any kind of relationship with people responsible for financial documents at the client. Some studies show that it exists some benefits with some kind of relationship between the auditor and the client. For instance, the audit could be performed more effective which will reduce the audit fee and it can also be performed with more expertise (Firth, 1980). The auditor independence is one of the most important fundamental principles in the auditor’s work. The consequence of the auditor not being independent is that the audit opinion will be of no value and the users of the financial statement will feel less confident which will result in more insecurity in the capital market. The auditor’s independence is one of the major principles within the audit profession (Firth, 1980). It is important for auditor’s reputation and it is seen as value for auditors and audit firms (Wan Ismail & Kamarudin, 2012).

2.2.3 Client satisfaction

Commercialization is a relevant topic when it comes to the auditing profession and explaining the term client satisfaction within the profession. Commercialization is about the process of producing a new service or product to offer the market (Investopedia, 2019). Consultancy and NAS have been two important services for the development and growth of audit firms, for several audit firms, these services stand for more than 50% of their revenues (Copeland, 2010). According to Broberg et al. (2018), commercialization in the audit profession can be assignable to the Enron scandal. The consequences of the Enron scandal were that the relationship between audit firms and commercial orientation got a negative view. Prior research had also shown that auditing and commercialization were two activities that could not be combined since auditors should focus on their obligations instead of activities connected to business development (Kotler & Connor, 1977). Before the Enron scandal, studies shown that auditor’s independence

16

against their clients could be threatened when they perform activities outside the audit. This could also trigger them to focus on financial profits (Humphrey and Moizer, 1990; Chesser, Moore & Conway, 1994). After the Enron scandal, the impact of commercialization in the audit profession was a well-investigated topic. The results from the studies showed evidence that commercialization within the audit profession may result in unethical behavior, reduced auditor independence, and also reduced audit quality (Sharma & Sidhu, 2001; Citron, 2003; Carter, Spence & Muzio, 2015).

There are two ways of describing commercialization in audit firms. The first one is the provision of NAS and the second one is audit firms marketing activities. NAS can be described as consultancy services such as accounting and tax advisory which is outside the auditor’s traditional audit role. The introduction of NAS was due to an increased demand for this type of service (Clow et al., 2009). The second indicator of commercialization in audit firms is activities that involve marketing and advertising. According to Clow et al. (2009) have marketing activities increased among audit firms. The reason for this is to get a competitive advantage by both retaining current customers and to reach out and attract new customers (Hodges & Young, 2009). Broberg et al. (2013) also indicate that the increased focus on marketing is because the audit firms intend to develop and expand their customer base but also the markets that they are active in. Western scholars have argued that lack of competition could lead to a large concentration to the Big 4 audit firms when it comes to choosing auditor which can reduce the audit quality. This implies that commercialization is something that can benefit auditing as a profession because it increases the competition between audit firms which leads to higher audit quality (Debates, 2010). It exists some similarities between the two approaches described. In the first NAS approach the commercialization initiate because of customer demand for business services from clients. Which makes audit firms adapt to customer orientation in order to fulfill this demand. This is different from the client-orientated approach where the focus is on the public interest instead of commercial gains (Öhman, 2007). The adaption that audit firms do based on the demand for services strengthens the idea that introducing more services could lead to an increase in financial gains. In order to take advantage of the demand and the possible financial gains are audit firms forced to develop new structures that are different from the traditional structures in a professional firm (Hill & Hoskinsson, 1987). One reason for the commercialization in the audit profession is globalization which has resulted in increased competition between audit firms (Sori, Karbhari & Mohamad, 2010).

17

There is a conflict between professionalism and commercialization in audit firms (Gendron, 2002). The main objective of professionals is to serve the public and make decisions without being affected by external pressure (Sikka & Willmott, 1995, p. 554). Commercialization is the opposite of professionalism on several points. For instance, they want to make profits on audit activities. This means that they try to satisfy the company they audit through favoring their interest. This is the case because they want to be appreciated by the company’s management to receive audit renewal and consulting engagements (Kaplan, 1987). The government has restricted how much the audit firm can gain from consultancy services, this amount depends on how much they gain from the traditional audit of a client. The reason for this is that audit firms should not become financially dependent on a client and restrict the sales of these services (Prop. 2015/16:162). There is a lot of prior research showing that consultancy services are problematic because the risk of reduced independence from the auditor and a to close relationship with the client (Brandon, Crabtree & Maher, 2004). It also exists a concern from the public that the auditor, therefore, acts with less objectivity (Sori et al., 2010). The consultancy services can also do that the auditor is not enough critical against their clients since they are scared to lose incomes to the audit firm (Sharma & Sidhu, 2001). Broberg (2013) contradicts this and instead claims that it does not influence the auditor’s work since they have rules to follow to keep a high audit quality and professionalism. The principal rule is that the auditor that performs the audit does not perform other services in order to retain objectivity (Broberg, 2013). So, the problem is that people outside see that the involved people are from the same audit firm and think it is a problematic situation. This affects the public’s perception of auditors, but the services are separated so the auditors act with independence (Glazer & Jaenicke, 2002).

The commercialization shows that the auditing profession has moved to have a larger focus on the client, where client satisfaction is a big part of it. Client satisfaction originates from the customer satisfaction concept in the marketing literature (Oliver, 1996). Client satisfaction is important in the auditing profession since audit firms afford their services to companies that are audit clients (Behn, Carcello, Hermanson & Hermanson, 1999). According to DeAngelo (1988) do audit clients base their level of satisfaction on their own desire. There is evidence that demonstrates that auditors sometimes make accounting decisions based on the client’s opinion and accept financial statements that do not comply with accounting principles and laws (Beattie, Brandt & Fearnley, 2001; Westerdahl, 2005). One important aspect of client satisfaction is that it could function as a starting point for selling additional services to the client

18

(GAO, 2003). This means that it can generate increased economic profits for an audit firm in the future. It can also generate a good reputation which can have several valuable impacts on the audit firm (Herda & Lavelle, 2013). This can be strengthened by similar thoughts in commercialization, with a larger focus on meeting customer demands and economic profits (Clow et al., 2009).

What represents value for auditors can be based on this divided into certain categories. The two first categories are that auditors want to retain their professionalism and independence when they work. Auditors also see a value in client satisfaction, since it can have positive effects on the audit firm in the future. Economic profits are another aspect that has grown and is seen as value for some auditors. Furthermore, is also a good reputation important for auditors. The last three categories, client satisfaction, economic profits, and reputation have a clear connection and affect each other.

Figure 2: Value for auditors

2.3 How the auditor creates value for the family firm 2.3.1 The auditor’s role for the firm

FAR explains that the auditor profession consists of two primary roles: one as a reviewer and another as an advisory regarding the review process. As a reviewer should the auditor review the business’s annual reports, accounting, and the boards and CEO’s management, and make a

19

statement that the financial documents show the right picture over the firm’s financial situation. This is important and gives reliability and comparability to investors and stakeholders. The information is also seen as more trustworthy and of more quality after it is reviewed by the auditor that is independent (Öhman, 2004). During the review process should the auditor address misstatements (ISA 200, 2009) to protect the stakeholders from wrong information in the role as an audit advisor (Öhman, 2004). Concerning the advisory role, it is important to separate the audit advisory regarding the review process and other advisories that can be seen as a consultancy service. The audit advisory contains advice that the auditor has come up with during the review process and it is advice that the auditor needs to give. For instance, the auditor informs the company about misstatements found during the review process to secure that information is correct (Svanström, 2004). It can also be other advice such as tax advice that is not charged in addition to the audit itself (Gooderham, Tobiassen, Døving & Nordhaug, 2004). All the advice during the audit is valuable for the company since the company receives things to improve in order to increase profitability and efficiency (Svanström, 2004). It is mostly smaller companies that have the demand for audit advisory since they do not have the same opportunities and competence as larger companies have (Gooderham et al., 2004).

There are numerous studies showings that there exists an expectation from clients that the auditor should contribute with other services than those within the traditional profession (e.g., Fontantine et al., 2013; Broberg, 2012; Herda & Lavelle, 2013). Advice that is not covered by the audit advisory is a consultancy service and also a NAS. These services are not based on any material of the review process from the audit, instead, this role is depending on specific situations in the company (Svanström, 2004). The study performed by Fontantine & Pilotes (2012) showed that the biggest part of the companies investigated wanted the auditor to perform additional services than the audit, which implies that they want NAS. For instance, the audit firm takes an audit fee by the client and in some cases, the auditor needs to deliver NAS and create value to satisfy and to keep the client (Paterson & Valencia, 2011). As already mentioned, is several NAS allowed to perform in Sweden according to paragraph 21b§ in the Swedish auditor act that has been mentioned as inappropriate to perform by the European Parliament (European Parliament and of the Council, 2014). But the auditor cannot make all types of services for the company that they audit and have as a client. The most important part in the auditor’s work is to be independent in the work they perform (Öhman, 2007; ISA 200, 2009). According to Svanström (2008), it exists a risk that the audit services can have an impact on the audit quality and that the auditor’s independence is more threatened in smaller firms

20

since they often have a closer relation to each other. It is explained that auditors who have worked with a client for a long time want to bring more value to that client than other clients. That together with the threat of losing the client can lead to that the auditor threat their independence and professional way of working (Warren & Alzola, 2009).

2.3.2 The auditor’s role for the family firm and added value

As an auditor in a family firm, you will meet a company governed by a family, that could be driven by a family and the goal to increase the socioemotional wealth (Collin et al., 2017). Regarding family firms, it is shown that roles and relations often will be in long terms (Miller & Le Breton-Miller, 2006). Financial advisory is more popular in small and middle large companies to strengthen their position, growth, and survival, and it is even more common in family firms (Barbera & Hasso, 2013). It is also shown that the auditor generates added value for the company that is audited, and even more usual if it exists a longer relationship between the auditor and the family firm (Fontaine & Pilote, 2012; Collin et al., 2017). This indicates that auditor’s and family firms often have a closer relationship between each other and that the auditor in some way need to generate added value for the family firm to strengthen their position with the company, otherwise the family firm may want to change auditor (Fontaine et al., 2013). In addition, family firms expect that some NAS should be included outside the traditional auditing by the audit firm (Herda & Lavelle, 2013). There are also studies that have shown evidence that family firms have a larger need for guidance than non-family firms. The added values the auditors bring to the family firms and the roles the auditor has is called differently in various papers. Collin et al. (2017) call the auditor for Consigliere and that they have roles as advising, mediating, and conveying. In other studies, have roles such as strategic planner, “ball board” and conflict manager been described (Brunstedt, 2008; Theander, 2011). These are roles outside the two primary roles that the auditor has as a reviewer and audit advisory that the company actually pays the audit firm to do independently. This means that the company gets some added value which they do not pay extra for. It does not mean that these added roles make the auditor not independent, but it cannot be excluded.

Advising

Advice that is not included in the traditional audit can be called a consultancy service and this advice are not connected to any material of the review process from the audit, instead, it can be advice about things that the client wonder, for example about situations that the company encounters or other general questions (Svanström, 2004). It can be advice to the company

21

concerning investment opportunities (Strike, 2013). It can also be advice to the family members about their personal tax situation and regarding dividend (Gersick, Davis, McCollom Hampton &Lansberg, 1997). Since family firms prefer to have long and close relationships can the auditor bring the firm’s history through different generations when the firm’s ownership is changed (Salvato &Moores, 2010).

Mediating

It is showed that in almost all firms it exists some sorts of conflicts. People in the family can have different opinions or interests in what is best for the business (Collin et al., 2017). According to Collin et al. (2017), do family firms have intentions to use the auditor as a person to solve conflicts between the family members when they have different opinions and interests since the auditor should be independent and not choose someone’s side. When it exists different opinions or it is a chance of it, the auditor can give their objective view of it and without emotions and self-interest. During the audits, the auditor has gained a lot of experience about the business and the family and at the same time is the auditor outside the family. The auditor has no winning of gaining any family member and the auditor can, therefore, be trusted on their knowledge and competence when trying to solve conflicts and giving advice. From the family firm’s perspective, this can be seen as helpful and generate value for them (Collin et al., 2017). Conveying

Another role the auditor can have in firms is as a conveying. As said before it can sometimes be conflicts within the family that is sensitive to talk about or other issues that make it hard to transport information or not willing to mediate the information. In that case, can the auditor take the role and convey the information to the right person. Since the auditor is independent and with no interest can the auditor be trusted to give the right information and not distort the information within the family (Collin et al., 2017). That the auditor contributes with advising, mediating, and conveying beyond the traditional auditing can, therefore, be valuable to the family firm.

The values auditors and audit firms bring to family firms are summarized and showed in the figure below. One value that auditors create to family firms is through the traditional audit, which brings value when they ensure that the financial documents are accurate and that the firm shows a trustworthy picture over the company which also is appreciated by stakeholders. Also, advice regarding the review process is value auditors create since it can be advice that makes the company more efficient and profitable. Another category that is important and

22

valuable for family firms is that the audit firm brings NAS to the company which also strengthens the audit firm’s position in the family firm. Family firms like to build long-term relationships with others that can help and bring value to the family firm, the relationship with the audit firm is one relationship that is valuable and important for the firm. Since the family firm likes to have long and close relationships with the audit firm it is possible for the audit firm to bring the history of the family firm through different generations in the family that is valuable for the family. There is an emotional bond between the firm and family that have an impact on how different decisions are taken, the audit firm can have an impact on this emotional bond. For instance, conflicts between family members can arise and the auditor can help to solve conflicts as an independent auditor. For family firms are services outside the traditional role valuable as advising, mediating and conveying since it creates added value for them.

Figure 3: Value auditors create for family firms

2.4 How the family firm creates value for the auditor 2.4.1The auditor-client relationship

The auditor also receives value from the family firm during the audit. The auditor is employed by the client to review the financial documents against a fee. This fee is often expensive for companies and in return is the client expecting a review of the financial documents and other types of value that compensate the audit fee (Fontaine & Pilote, 2012). Clients to audit firms appreciate different types of advice that could be about internal control and general advice about taxes for example. These types of advice are impacted by the client and the audit relationship. It is the auditors that decide how well they will respond to the clients’ demands and, in that way, can the auditor use the client and auditor relationship to strengthen their role in the company (Manson et al., 2001). Both the client and the auditor need to have trust for each other to bring out a reliable and effective audit. This is important since the auditor’s work

23

is about the client’s financial documents, the financial numbers need to be correct when doing the audit (Rennie et al., 2010). This is also others interested in such as shareholders and stakeholders. In that way is also the external parties impacted by how the client and auditor relationship look like since they are interested in the auditor’s work. The client and auditor relationship makes it easier for the auditor to understand the client’s business and what type of advice that is most valuable for them. In a similar way need the client to have trust for the auditor so they do not need to evaluate the auditor that often, this decreases the client’s chance of changing auditor which is of much value for the auditor. Therefore, it is important for booth parts to establish a long and trustable relationship that will generate payments and work for the auditor in the future (Fontaine & Pilote, 2012).

To get a good relationship between the auditor and the client it must be a fair treatment between the clients to have a well-working relation. The client can improve their relationship through positive attitudes against the auditor when they have meetings or contact through electronic devices (Golen, Catanach Jr., & Moeckel, 1997). The client needs to be accommodating, by providing the information that the auditor needs to review the client’s different financial documents, the client should also provide the auditor with a pleasant environment when the auditor is visiting the firm and be patient when the auditor has questions (Rennie et al., 2010). This makes it more effective and easier for the auditor to do their job which is appreciated and when the family firm is happy with their auditor and feels that they receive the value they can generate positive attitudes to the auditor and talk good about them to others which benefit their reputation. This increases the chance for the auditor to retain their current clients and to get new valuable clients. The clients that have a bad attitude, do not like questions, and show that they do not like the contact with the auditor is often treated worse than others. It is also because of the bad relationship they have, the auditor cannot give services and advice that generate added value in the same way to clients with bad attitudes compared with others with good attitudes since they are more cooperative. This return from the auditors is the basis of what the client’s perception is of the auditors added value. That shows that the client and auditor relation need to be mutual (Herda & Lavelle, 2013).

The value that the family firm creates for the auditor can be summarized into three categories. The first one is economic profits that the family firm creates for the auditor by paying audit fees and fees for other services they receive. A good relationship is another way for how the family firm creates value for the auditor. Since a good relationship between them can facilitate the auditor’s work and increase the quality of it. The family firm can also create value for the

24

auditor by spreading a good reputation about the auditor. A good reputation has several future potential benefits for the auditor, by both retaining current clients and receiving new clients.

Figure 4: Value family firms create for auditors 2.5 Co-creation

When the auditor and the family firm interact with each other will value be created that is co-created. According to Prahalad & Ramaswamy (2004) is the definition of co-creation, a value that has been jointly created, which in this case is between the auditor and the family firm. Both parts need to implement actions if the value should be able to be defined as co-created. As already mentioned, is co-creation between auditors and their clients a topic with a lack of prior research (Grönroos & Voima, 2013). In the existing literature about co-creation is the quality of the interaction between the provider and the customer an important part of the value creation (Grönroos, 2011). Knechel et al., (2015) strengthen this by highlighting the importance of collaborative between the auditor and auditee in the co-creation process. The co-creation emerges when the resources and competencies are integrated between them (Grönroos & Voima, 2013). Another part that has an impact on the co-creation is how good the communication is between the service provider and customer which also is related to the quality of the interaction and collaborative (Vargo & Lusch, 2004). There is one framework developed that explains how co-creation of value in auditing works. According to this framework is it a balance between four factors in the auditing process that contribute to the co-creation of value. The four factors are auditors, clients, professionals, and the client’s stakeholders. All these factors are involved or have an interest in the auditing process, it is a balance between all four which will lead to co-creation of value (Nguyen et al., 2015).