Exploration of Danish

orthotists perceptions on

AFOs in early post-stroke

management

BACHELOR THESIS 15 CREDITS FIELD WITHIN: Prosthetics & Orthotics

AUTHOR: Rikke Højhus Jensen & Sarah Bugge Larsen SUPERVISOR: Nerrolyn Ramstrand

JÖNKÖPING May 2021

2

Resumé

Titel: Udforskelse af danske bandagister meninger af AFO’er i tidlig post-stroke rehabilitering - Et kvalitativt studie

Baggrund: Tidligere videnskabelig litteratur vedrørende tidlig post-stroke ortose behandling er næsten ikke eksisterende. I Danmark, findes der ingen nationale retningslinjer omhandlende AFO’er i tidlig post-stroke rehabilitering eller den rolle bandagister spiller i denne fase. Apopleksi/post-stroke er den tredje mest almindelige dødsårsag i højindkomstlande og en ud af syv i Danmark vil opleve en stroke i løbet af deres liv. Formål: Dette studie har til formål at beskrive den nuværende situation relateret til brugen af AFO’er, bandagistens rolle i tidlig stroke behandling og at udforske danske bandagisters synsvinkel på brugen af ankel-fod-ortoser i den tidlige fase af rehabilitering efter stroke.

Metode: Seks danske bandagister blev rekrutteret til at deltage i et individuelt interview med semi-strukturerede åbne spørgsmål. Interviewet blev transskriberet og analyseret ved brug af indholdsanalyse. Resultater: Tre temaer i dette studie: (1) Barriere relateret til brugen af AFO’er i tidlig post-stroke rehabilitering, (2) Utilfredshed blandt bandagister omkring deres rolle i post-stroke rehabilitering, and (3) Facilitatorer til brugen af AFO’er i tidlig post-stroke rehabilitering.

Konklusion: De genererede temaer fra dataen kan hovedsageligt opdeles i facilitatorer og barrierer i relation til brugen af AFO’er som behandling tidligt efter stroke. Danske bandagister opfattede ikke at de var inkluderet i de multidisciplinære teams som en del af den tidlige behandling efter stroke. Dette studie giver indsigt i de faktorer som muligvis påvirker brugen af ortoser tidligt i behandlingen efter stroke, hvilke mulige effekter AFO’er kan have på patienten, og funktionen af et multidisciplinært team, fra seks danske bandagisters perspektiv.

3

Abstract

Background: Previous scientific literature regarding orthotic treatment as early post-stroke management is almost non-existing. In Denmark, no national guidelines exist regarding the use of AFOs in early post-stroke management, nor the role of the CPOs within the phase. Stroke is the third most common cause of death in high income countries and one in seven in Denmark will experience a stroke during their lifetime. Aim: This study aimed to describe the current situation related to use of AFOs, and role of orthotists, in early post-stroke management and to explore the perceptions of Danish orthotists regarding the use of AFOs in early post-stroke management.

Method: Six Danish orthotists were recruited to participate in individual interviews using semi-structured, open-ended questions. The interviews were transcribed and analyzed using content analysis.

Results: Three themes emerged within this study: (1) Barriers to the use of AFO in early post-stroke rehabilitation, (2) Dissatisfaction amongst CPOs with their role in post-stroke rehabilitation, and (3) Facilitators to the use of AFOs in early post-stroke rehabilitation.

Conclusion: The generated themes from the data were mainly divided into facilitators and barriers in relation to the use of AFOs in early post-stroke management. The Danish orthotists did not perceived themselves as included into the early post-stroke rehabilitation multidisciplinary team. This study gives an insight into factors that might affect the use of orthoses in early post-stroke management, what a possible effect of early application of AFOs could be for the patient and the functions of multidisciplinary teams, from the perspective of six Danish orthotists.

4

Table of contents

Index of terminology ... 6 Introduction ... 7 Background ... 7 Stroke ... 7Stroke management in the acute-, subacute, and chronic phases ... 8

Orthotic management of stroke in rehabilitation ... 9

National guidelines regarding AFO treatment post-stroke ... 10

Aim: ... 10 Methods ... 10 Design ... 10 Participants ... 11 Data collection ... 11 Analysis of interview ... 12

Early post-stroke definition ... 12

Ethical considerations ... 12

Results ... 13

Barriers to the use of AFOs in early post-stroke rehabilitation ... 15

Health policies... 15

The process of the application ... 17

Financing of devices ... 18

Physiotherapists are not supportive ... 19

Non-existing multidisciplinary teams ... 19

Patient noncompliance ... 22

Other healthcare professionals lack general understanding of AFOs ... 23

Psychosocial factors related to the patient ... 23

Dissatisfaction amongst CPOs with their role in post-stroke rehabilitation ... 24

AFO treatment not handled by CPOs in early rehabilitation ... 24

The potential inclusion of CPOs in multidisciplinary teams ... 25

Facilitators to the use of AFOs in early post-stroke rehabilitation ... 25

Investments in temporary AFOs ... 26

CPOs opinion regarding the role of AFOs ... 26

The patient related benefits of AFOs early post-stroke ... 27

Healthcare professionals in neurorehabilitation ... 27

5

Discussion ... 28

Method discussion... 28

Data analysis ... 30

Result discussion ... 31

Current practices regarding AFO use post-stroke ... 31

What are Danish orthotists perceptions of the role AFOs, and orthotists should play in early post-stroke management? ... 34

Conclusion: ... 36

Limitations ... 36

Further research ... 37

Funding ... 37

Declaration of Conflicting Interests ... 37

Acknowledgements ... 37 References: ... 38 Appendix ... 42 Appendix 1 ... 42 Appendix 1.2 ... 44 Appendix 2 ... 46 Appendix 3 ... 47 Appendix 4 ... 48

6

Index of terminology

Intext: CPO instead of orthotists In Denmark you are certified educated in both orthotics and prosthetics, embraced under one definition (in Danish: bandagist). This means that they are not only orthotists. To cover this linguistic contrast and difference in technical terms between English and Danish, while encapsulating the meaning of the Danish term, they are cited as Certified Prosthetists and Orthotists (CPOs) within this study.

Funding application

In Denmark, patients are entitled to write an application, stating the patient needs and which type of assistive device, to send to the municipality. This could also have been named the prescription process, but as the participants mainly used “application” this was decided to stay as close to the transcriptions as possible.

Grant

Receiving an assistive device/orthosis, post application, prescription and approval of this. “Snitfladekatalog” - index catalog for rehabilitation of brain injuries

A catalogue obtaining written guidelines for the planning of the rehabilitation and training of specific injuries in relation to guidelines of rehabilitation, which is to be planned by the municipalities and thereby addresses these.

7

Introduction

In Denmark, more than 230.000 are estimated to have suffered from a brain injury

(Hjerneskadeforeningen, n.d.), and each day, brain damage hospitalizes 71 adults and four children. The Danish Data Health Board (Sundhedsdatastyrelsen, 2019) has estimated that the amount of Danish citizens experiencing and/or living with all types of brain damages is expected to increase by 4.000 people each year, corresponding to an increase of 25% in those registered in Denmark between 2011-2017. Of the total number of registered brain injuries, only 60.000 are not caused by stroke (Hjerneskadeforeningen, n.d.), thus cementing that stroke is the main cause of brain damage in Denmark and one in seven people will experience a stroke. According to Union of Brain Damage (Hjerneskadeforeningen, n.d.), consequences of brain injuries include communication problems, mental disturbances and physical disabilities. Physical disabilities experienced are mostly a decrease in balance as a result of dizziness, fatigue, hemiparesis or drop foot. To treat this, ankle-foot-orthoses (AFO) can be applied (Shin et al., 2019) and this treatment is commonly managed by an orthotist. In Denmark, however, orthotists are not described as a part of the post-stroke rehabilitation team, as this is managed by healthcare professions such as physiotherapists, occupational therapists, neuro doctors and speech therapists (Sundhedsstyrelsen, 2014).

The purpose of this study was to explore the current and desired role of orthotists and the use of AFOs during early post-stroke treatment as perceived by the Danish orthotists. This was considered relevant as little scientific literature has previously focused on early post-stroke orthotic treatment. The Danish perspective was interesting as orthosis and Danish orthotists were discovered unmentioned in any Danish guidelines regarding post-stroke management.

This study aimed to describe the current situation related to use of AFOs, and role of orthotists, in early post-stroke management and to explore the perceptions of Danish orthotists regarding the use of AFOs in early post-stroke management.

Background

Stroke

Stroke is a result of a lack of blood supply to the brain and can cause death of the affected cells in the brain. The two types of stroke are ischemic stroke, caused by thrombosis (blood cloth) where vessels are blocked, and the subarachnoid- or intracerebral haemorrhage, which is increased pressure either within or around

8 the brain as a result of an arterial bleeding. The bleedings can either be caused by aneurysm bursts or ruptures along the arteria (Wilkinson & Lennox, 2005).

The most common limitation caused by stroke is related to gait and posture (Patterson et al., 2010). Stroke also leads to neurological damage. When one side of the brain is affected, neurological problems will appear on the opposite side of the body (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020).

One of the most frequent consequences of stroke is hemiparesis (Hatano 1976), of which the most commonly linked affliction is drop foot. This is usually due to plantarflexor stiffness, dorsiflexor weakness, or increased spasticity (Shin et al., 2019). Patterson et al. (2010) found a relationship between decreased gait symmetry and post-stroke patients and found the gait pattern of these patients to be increasingly asymmetric as time progressed. They concluded that quality of gait seemed to worsen over the years for post-stroke patients.

The World Health Organization [WHO] (2020) found strokes to be the third most common cause of death in high income countries, including Denmark. According to The Danish Health Board (Sundhedsstyrrelsen) in collaboration with The Danish board of Resuscitation (Sundhedsstyrelsen & Dansk Råd for Genoplivning, 2020), stroke hospitalizes 12.000 Danish citizens each year and one in seven Danes will experience a stroke during their lifetime. In Denmark, the economic cost of stroke in 2015 was 2,6 billion Danish Kroner in both treatment and lost work ability costs (Flachs, 2015).

Stroke management in the acute-, subacute, and chronic phases

Stroke management has been described under into three phases (Bernhardt et al., 2017): the acute (0-7 days)-, subacute (1 week - 6 months)- and chronic (>6 months) phases. For each phase the neurological state differs, requiring different management- and treatment plans.

The overall aim of rehabilitation post-stroke is to maintain as much function as possible and minimize impairments using a multidisciplinary approach to treatment. The focus of treatment in the acute phase is to control damage to the brain in accordance with the type of stroke, and to then either control the bleeding or decrease brain pressure (Tsagaankhuu et al., 2016).

Within the first month post-stroke, the neural plasticity has the greatest possibility for change and it is recommended that training should be initiated at this time (Bernhardt et al., 2017). For post-stroke

rehabilitation during the subacute phase, the restoration of motor function conducted through training and physical activity is possible although many patients will ultimately still suffer long term disabilities (Dimyan

9 & Cohen, 2011). Interestingly, in both the subacute and chronic phase, the application of Ankle-Foot-Orthoses (AFO) have been found to be superior to non-orthotic treatment (Pongpipatpaiboon et al., 2018; Yamamota et al., 2018; Nikamp et al., 2019). However, almost no scientific literature has explored the effect of AFOs within the acute phase or within the initial/early stage besides Nikamp et al. (2017). The orthotic management of stroke in rehabilitation varies according to different national clinical guidelines. In Scotland, according to the NHS Quality Improvement Scotland (2009), early orthotic

treatment in combination with physiotherapy should be a part of the rehabilitation and treatment of stroke patients. In the United States, orthotic use is recommended when it can increase the patient’s

independence after stroke (Winstein et al., 2016).

Orthotic management of stroke in rehabilitation

The goal of AFOs in post-stroke management can provide support during both stance- and/or swing phases of gait, depending on the goal of gait. In stance, medial-lateral stability of the ankle should be obtained, and in swing, toe-clearance should be ensured to improve walking mobility (Nikamp et al., 2017; Ota et al., 2017; Pongpipatpaiboon et al., 2018). AFO’s can be applied when the patient has a drop foot caused by either spasticity or muscle weakness of the plantar- and dorsiflexor muscles of the foot (Shin et al., 2019). The opinions regarding use of orthosisdiffer between different healthcare professions, as some do not encourage use of orthosis which they believe prevent or delay muscle recovery (Tyson et al., 2013). Current guidelines, such as that from the Royal College of Physicians (2016), do, however, encourage the use of AFOs to provide stroke patients the ability to walk independently during rehabilitation.

In 2018, Tyson et al. published a controversial article questioning the effect of orthosis on post-stroke patients, mentally and physically, which lead to “Letter to the Editor” (Kirker and Tylor, 2018). Responses to the authors suppositions, argue against the applicability of the study and demonstrate the conflict in opinions between different healthcare professions regarding the application and effect of AFOs.

In contrast to Tyson et al. (2018), others support the use of lower limb orthosis post-stroke (Nikamp et al., 2017; Pongpipatpaiboon et al., 2018; Ota et al., 2019; Yamamota et al., 2018). These and other studies have found AFO use post-stroke to be superior to non-orthotic treatment (Ramstrand et al., 2021).

10

National guidelines regarding AFO treatment post-stroke

The NHS Quality Improvement Scotland (2009) underlined the importance of the orthotists’ role within early post-stroke rehabilitation and the importance of early orthotic treatment. Contrary to Scottish guidelines, Denmark lacks similar structure, and the role of the orthotist has not been properly defined. In Denmark, post-stroke patients have the right to rehabilitation assistance through physiotherapy and occupational therapy training in accordance with guidelines set by Sundhedsstyrelsen (2014). In the case of dropfoot, paresis or spastic limbs, no guidelines regarding orthotic treatment are mentioned.

In Denmark, there is a lack in in-depth knowledge in relation to which type of AFO is applicable at what time within the post-stroke treatment. Furthermore, the national guidelines regarding post-stroke patients and orthotic management remain an area in desperate need of further exploration. This study aimed to describe the current situation related to use of AFOs, and role of orthotists, in early post-stroke

management and to explore the perceptions of Danish orthotists regarding the use of AFOs in early post-stroke management. Therefore, the phenomenon of interest in this study is the perceptions of Danish orthotists regarding orthotic management early post-stroke.

Aim:

This study aimed to describe the current situation related to use of AFOs, and role of orthotists, in early post-stroke management and to explore the perceptions of Danish orthotists regarding the use of AFOs in early post-stroke management.

Methods

Design

This qualitative study gathered perceptions from Danish orthotists related to early post-stroke orthotic management. The questions were open-ended, semi-structured questions (Roulston & Choi, 2018) and developed from previously published literature (Tyson et al., 2013; P. Charlton, personal communication, February, 2021). The questions were then reviewed in cooperation with both a clinical orthotist and an academic orthotist involved in stroke research. Additionally, demographic questions were asked during the interview (clinical experience in years, education institution, and previous and current workplace) to establish respondent backgrounds.

11

Participants

The inclusion criteria for recruiting participants for this study was that the participants were Danish Certified Prosthetists and Orthotists (CPO), was located in Denmark and spoke Danish and/or English. The exclusion criteria were if participants were students, who haven't received their certification yet or retired CPOs. The participants of interest were therefore certified Danish CPOs and prosthetists, sampled

purposively. Participants were invited to volunteer through written and verbal information. Firstly, they were invited to participate in the study via an e-mail sent through the organization representing them, the Danish certified prosthetists and orthotists (Danske Bandagister). The participants were invited to

volunteer as participants via a letter (see appendix 1). This did not result in any responses and therefore phone calls to all Danish companies were made. One company chose to re-send the letter to all their employees, which sampled three participants. The remaining three were sampled through the other follow-up phone-calls to other companies and an altered version of the letter of information was sent immediately after this (appendix 1.2), as well as the consent.

This study aimed to describe the current situation related to use of AFOs, and role of orthotists, in early post-stroke management and to explore the perceptions of Danish orthotists regarding the use of AFOs in early post-stroke management.

Data collection

By wanting to explore the Danish orthotist perceptions regarding orthotic management early post-stroke, a phenomenon which has not yet been explored. Follow-up questions were asked either to ensure a more in depth- and fluent conversation with the participant, or to describe their previous statements in more detail. The semi-structured questions established a framework for the interview and facilitated a more natural flow to the conversation. The interviews were conducted and analyzed in Danish and the interview questions can be found in appendix 2 in both Danish and English.

The interviews were conducted through Zoom due to the Covid-19 situation and recorded both on Zoom and on a mobile phone. The interviews themselves were conducted by two female prosthetic and orthotic students as a part of their bachelor thesis.

The interview recordings were transcribed by the researchers and compared to the recordings to safeguard the collected data before starting the process of data analysis. Both researchers transcribed three

12

Analysis of interview

The collected data was analyzed using an inductive approach and method to investigate different cases and identify statements (Kennedy, 2018) related to early post-stroke management using orthoses. As the research aimed to present the perceptions of orthotists’, a neutral perspective needed to be taken by researchers to ensure that data was not mis interpreted or construed differently than what the interviewee intended. Content analysis was used to allow creation of general themes from the data, using a

methodology suggested by Graneheim and Lundman (2004). Five steps of content analysis were followed to create categories and themes from the interviews. The first step was to identify meaning units arising from statements in the interviews. The second step was to create condensed meaning units, in other words, a description close to the data. The third step was an interpretation of underlying meanings units from within the interviews, also known as codes. The fourth step was to create subcategories, where codes are gathered in groups in relation to one another. Common categories were then found, and themes created, forming the fifth and final step.

The researchers conducted all data analysis together and continued to analyze data until no new themes emerged. This was done to make sure that all relevant data for the purpose of this study was included and no data lost. If one researcher did not agree on the meaning or coding of a particular set of data,

differences were discussed until an agreement was reached between both parties. If an agreement could not be reached, a third and neutral part would then be included to decide the outcome.

Early post-stroke definition

To specify the period of interest, the researchers choose to define early post-stroke within the first 2 months after the occurrence of the stroke. This was found necessary to narrow down the time period of interest to specify the answers from the participants during the data analysis.

Ethical considerations

Before conducting this study it was reviewed by The Research Ethics Committee at Jönköping University (see appendix 3). The comments on the study from The Research Ethics Committee was mainly concerning the information letter to the participants (see appendix 1). The letter, sent out through the organization representing Danish certified prosthetists and orthotists (Danske Bandagister), was sent before receiving feedback from The Ethics Committee, therefore it was not possible to alter the letter to the participants at that time.

13 As a qualitative interview was used to gather the collected data participants can not be anonymized as they will be participating face-to-face with the interviews. However, patients and their statements will be anonymized and can not be traced.

No harm, no physical or psychological violation was applied to the participants or clinics participating. The aim and purpose of this study and the interviews was presented both in written and verbal form to the participants. The consent and all information were written in Danish and all communication was conducted in Danish.

Before conducting the interviews, participants were informed that they were allowed to withdraw

participation in the study at any time, were allowed to not answer questions during the interview and that their identity was kept anonymous within this study. Only the participants and the interviewers had access to all data, which was stored on a computer with password protection. The recordings will be stored on a safe computer on the School of Health and Welfare at Jönköping University.

Results

Six Danish CPOs volunteered to participate in the study. Their level of experience within the field of orthotics ranged from 1-36 years (average = 18.2 years). Details of participants are presented in table 1.

Participant

number Gender Working experience (years)

1 Female 1 year 2 Female 25 years 3 Male 31 years 4 Female 36 years 5 Male 10 years 6 Female 6 years

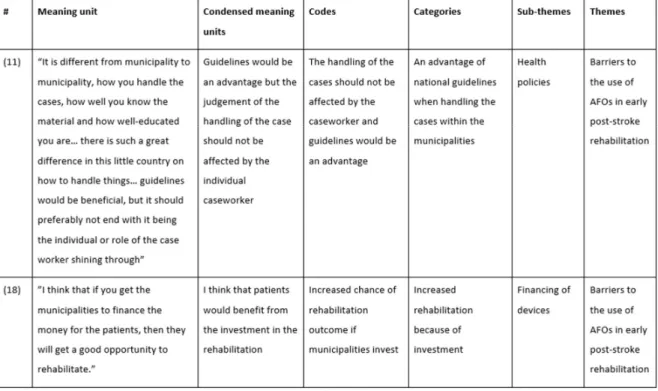

14 The meaning units were identified within the transcriptions and the researcher condensed these. The condensed meaning units were then coded and categorized, and through that, the sub-themes was determined. The sub-themes were then gathered into themes as demonstrated below in table 2.

Table 2. Table with examples of data analysis and coding

During the data analysis the following three themes emerged: (1) Barriers to the use of AFO in early post-stroke rehabilitation, (2) Dissatisfaction amongst CPOs with their role in post-post-stroke rehabilitation, and (3) Facilitators to the use of AFOs in early post-stroke rehabilitation. From within each sub-theme, themes were afterwards created. Each theme and its derived sub-themes are presented below (table 3). Quotations from interviews are denoted to correlate the data, sub-themes and themes.

15 Table 3. Table of themes and sub-themes

All citations can be found in their original language (Danish) in appendix 4.

Barriers to the use of AFOs in early post-stroke rehabilitation

Participants described several factors which prevented the use of orthoses in the early rehabilitation post-stroke. Eight specific barriers were identified within the data. These included current health policy, the process of the grant, financing of devices, physiotherapists are not supportive, non-existing

multidisciplinary teams, other healthcare professionals lack the general understanding of AFOs, patient noncompliance, and psychosocial factors related to the patient.

Health policies

Participants specifically mentioned paragraph §112 of the Danish legislation as a major roadblock in managing early post-stroke treatment. Almost all participants [5] addressed how the legislation states that patients are not entitled to an assistive device if the patient is not at a physically stable state which early post-stroke patients are not. This directly impacts and affects stroke patients, and all CPOs raised concerns with how municipalities reject early applications, due to how it conflicts with potential physical

16 municipalities are responsible for the provision of assistive technologies to patients with decreased

functional levels.

(1) “... in order to receive an assistive device, it has to increase the functional abilities… It must not be anything wearable pain relieving… Because it will be rejected [by the municipality].” (participant 4) (2) “I think that paragraph 112 is the primary [problem] but there is actually one more, but it’s said

that if it can increase their functional level, it should be prescribed” (participant 1)

(3) “...and before it is established how permanent this is, well, then there are some municipalities that might reject the application of an assistive device, and that is clearly a problem.” (participant 5) (4) “...they do not prescribe early AFO’s, it might be because it actually would be to shoot people in

the foot, meaning they will not receive it again… Even though I find the arguments to be fair regarding the change of situation as of today.” (participant 2)

As a result of lack of guidelines, each municipality can therefore freely decide on how long of a proceeding is required for a patient to be reviewed and potentially granted an assistive device. The participants reported significantly different time ranges, anywhere from two to sixteen weeks in processing.

Furthermore, a third of the participants [2] voiced concerns related to varying rehabilitation procedures post-hospitalization, as municipalities also have the same freedom to decide between these, resulting in even greater variations across Denmark.

(5) “...it may take up to 16 weeks for them when it is a first time application” (participant 3) (6) “When the patients are discharged from the hospital, they commonly end out in municipality

sphere, and then, it depends on what the offer is in the specific municipality” (participant 5) The great variety in handling the above-mentioned areas, conjoined with educational standards and knowledge within the employees at the municipalities can directly affect the outcome of each case and application. As there are no national guidelines or laws embracing the post-stroke patient within the rehabilitation, according to more than two of the participants [3], each case then becomes individual,

17 guaranteeing no common ground from which to develop or share experience, or create a new national standard.

(7) “...we have 98 municipalities, and we also have 98 ways of doing things” (participant 4)

(8) “It is different from municipality to municipality, how you [the caseworker] handle the cases, how well you know the material and how well-educated you are… there is such a great difference in this little country on how to handle things… guidelines would be beneficial, but it should preferably not end with it being the individual or role of the case worker shining through” (participant 3)

The process of the application

Before applying for funding for an AFO, three participants explained patients who obtained a referral from their doctor or other health professionals tied to their care, would greatly increase the odds of getting their application approved. This specifically illustrates the significant role that the general Practitioner has in the general healthcare system, as municipalities rely on, and place great trust in, their assessment of each patient.

(9) “Well, when a customer arrives, a patient, who has had a stroke, a doctor written statement it is necessary regarding that they have a drop foot or a pes equinus foot and needs a drop foot orthosis” (participant 1)

Barriers related to processing times were expressed by half of the participants [3] as a hurdle which adversely affected the patient physically. At present there are no guidelines suggesting how long the patient should have to wait for an answer from the municipality, and during that time, he or she does not receive an orthosis and has to manage without.

(10) “The handling time of cases is a great issue in some municipalities and if you are in a process where you need something and have to wait up to 16 weeks on a decision, it is hopeless [the waiting time]. The waiting time is a great problem. Other municipalities can handle the cases from day to day.” (participant 3)

18 (11) “I see that it is a fine idea to wait to enter the process and prescribe a permanent helping aid. But

many will have a need requiring an assistive device and if they will receive it that late, then they have actually lost some function in all the time they have walked around waiting.” (participant 3)

Financing of devices

Financing AFOs in the early rehabilitation depends on patient’s location, available health professionals at local hospitals, or caseworkers within the municipality. When the patient transfers between hospital and municipal rehabilitation, they risk getting stuck in a financial grey-zone. This was identified as a problem in relation to early post-stroke rehabilitation by all the participants [6]. Payment related issues could also occur later in the process, once the patient had completed their rehabilitation within the municipality, if the rehabilitation team had not then referred the patient to a CPO.

(12) “...the patient ends in the financial grey-zone… it can occur when they [patients] end somewhere where they have to train and there is nothing [orthosis] to train with.” (participant 4)

(13) “We always have the problem about what is a part of the treatment and what is a permanent assistive device because it is distinguished really hard between these two things, because if it is a permanent assistive device, the municipalities would have to pay, and as a part of the treatment it is the hospital or the region. Some end up being pinched there.” (participant 5)

Almost all [5] of the CPOs suggested that the municipalities should prioritize and grant CPOs time to try out AFOs for those in need during early post-stroke rehabilitation. They also expressed a common desire that all municipalities would invest in temporary orthoses which could be stored at the municipal rehabilitation centers, as the need of orthoses can change over time for the post-stroke patient.

(14) “It must be that it [orthosis] is being tested and that there is time for the individual, so you find out what they need and then gets what they need the most. That would be the optimal.” (participant 3) (15) “I think that if you get the municipalities to finance the money for the patients, then they will get a

19 Physiotherapists are not supportive

CPOs felt a general lack of support towards the use of AFOs by physiotherapists for different reasons. Three of six participants expressed that most of the physiotherapists they met previously had opinions regarding the potential muscular recovery of post-stroke patients and discouraged the use of orthosis which might felt limited and immobilized joints, possibly delaying, or preventing muscle recovery.

(16) “...physiotherapists have actually not ended them [patients], and they should not, but they have not reached their… personal conclusion regarding that it [muscular dysfunction] can’t be trained anymore.” (participant 2)

(17) “The physiotherapists have some kind of “pocket philosophy”, thinking they can train these drop feet away.” (participant 2)

(18) “The physiotherapists preferably don’t want to have anything on.” (participant 6)

(19) “When the physios know that you are fixating a joint, that you are limiting the muscular movement of the bodywork, some thinks that it works against the muscular strength they are trying to achieve.” (participant 5)

Half of the CPOs [3] indicated that physiotherapists lacked knowledge of the functions of an AFO and specific instructions within the field, which they felt could explain why physiotherapists were and are so averse to using AFOs.

(20) “You can experience that physiotherapists are slightly against orthosis.” (participant 5)

(21) “If there is a profession, it is the physiotherapists that do not support it [orthosis] and do not speak about it in the same amount that you could wish for.” (participant 2)

(22) “...they [physiotherapists] unfortunately know too little if I am to be honest.” (participant 6)

Non-existing multidisciplinary teams

CPOs are currently not included in most of the early post-stroke rehabilitation, except under rare

20 these are accessible. The issue regarding non-inclusion of CPOs early post-stroke was directly addressed by many participants [4] during the interviews. The CPO usually only meets the patient much later in post-stroke treatment, when the patient has already completed rehabilitation and physiotherapy has ended, unless the physiotherapist has enough experience regarding the need and use of orthosis and can see the need for CPO involvement earlier in the process than what is commonly practiced.

(23) “It is much more when they [patients] get out into the municipality sphere that we as CPO’s enters.” (participant 1)

(24) “It is often that we [CPOs] don’t see the patient until further in the process where the municipality has not contacted the CPO at all. They are training within the municipality sphere with the

physiotherapist… and then we hear nothing until later in the process and that can also be a problem.” (participant 3)

(25) “It is not in the way that we [CPOs] are called in to a follow-up meeting with the physiotherapist.” (participant 5)

Some [2] blamed the blatant disregard of CPOs in early post-stroke treatment on the amount of different health professions involved or overlapping each other during the evaluation and rehabilitation of the patient. Early involvement would require those responsible for the rehabilitation assessment to include the CPO perspective and thereby prioritizes the asymmetric gait during treatment. In Denmark once a patient has left the hospital and been referred to out-patient care at a rehabilitation center by the GP, the doctors are no longer in the picture, and subsequently also no longer a part of the process in determining the proper rehabilitation strategy.

(26) “It is rare that you see them with a physio.” (participant 2)

(27) “It differs whether they [patients] have even talked or heard about it [orthosis], because how much does the gait mean for the patient? Perhaps being able to eat means a lot more, and then you [CPOs] aren’t prioritized.” (participant 1)

One of the consequences of excluding the CPO from the early rehabilitation, indicated by the participants, was that the multidisciplinary team does not adequately inform patients of the potential need for orthoses,

21 according to their view. If the rehabilitation clinic frequently by the patient does not focus on the role of orthoses, the patient is left to seeks out relevant information by his or herself or hear about it elsewhere and identify how it relates to their own needs. Half of the participants were discovered to have

experienced several common situations in their dealings with post-stroke patients, as seen in these excerpts:

(28) “... from family members they have heart something called an AFO’s exists or have heard from someone else who has an AFO… I think their own doctor can’t even catch them.” (participant 2) (29) “It is a permanent disability, where the municipality can choose to grant [assistive devices], when

there is a permanent disability. While your physical and mental status is accounted for in rehabilitation, you don’t know how big the need is.” (participant 4)

(30) “If it is not clear [physical state] in the beginning it is not sure that someone guides them in the correct direction, as it is the fewest that takes the initiative to apply for an assistive device or takes contact to a CPO if they aren’t encouraged to.” (participant 5)

The identification of the need for orthosis must be spotted by the CPO, according to one of the

participants, as it otherwise might be missed by those outside of the specialized rehabilitation clinics. The need for an orthosis is sometimes hard to identify in the initial and early rehabilitation and can therefore easily be overlooked by unaccustomed eyes.

(31) “Some visit a specialized department where a doctor will immediately write that the person needs an AFO in the referral which they bring and then we start from there. Others might come years later as they are to visit the CPO for other reasons.” (participant 3)

One participant found that sometimes the involvement of the CPOs was an improper result of a

coincidental encounter at a rehabilitation center, and not part of a preferred organized treatment process. The participant had often experienced being at rehabilitation clinics to meet with new amputees and spotting a post-stroke patient months into his or her rehabilitation with dire need of an AFO. This

exemplifies how the CPOs are not currently directly involved in the post-stroke rehabilitation, leaving it up to coincidence and happenstance.

22 (32) “It’s coincidental you [CPOs] are being involved. That is, of course, inappropriate.” (participant 3)

Patient noncompliance

Patients are sometimes themselves another barrier in using AFOs during the early rehabilitation process, as stroke can radically change the patient mentally as well as physically.

Tree participants addressed how the patient mentally needs to have adapted and accepted the physical change that they have experienced as a result of the stroke, and their potential need for an orthosis to be able to safely ambulate. This can be harder for some patients to come to terms with, as an orthosis is a clearly visible assistive device, and some might feel embarrassed about how they may appear when having to wear an orthosis.

(33) “... and they don’t think that they need an AFO. It is also about needing and depending on an AFO, a visual assistive device, and mentally it is a huge step, and many [patients] say no when they see an AFO because it is big and visible.” (participant 3)

(34) “...it is also a question about getting used to the thought of the citizens themself.” (participant 2) Patients may have specific preferences or even prejudiced beliefs towards the appearance of the AFO according to some of the participants [2]. These are sometimes manifested from earlier attempts and/or experiences during rehabilitation, where a physiotherapist may have presented them with whatever available AFO they had in their arsenal. Oftentimes, these mostly ill-fitted AFOs would have been presented to the patient as the only option to choose between, and thereby left the patient with an incorrect

perception of AFOs in general. This can lead to reluctance from the patient against orthoses in general, further complicating the work of the CPO, according to three of the participants.

(35) The resistance is also from the citizens...maybe because they have prejudiced beliefs about AFOs. They have seen the AFO before and think to themselves “I absolutely don’t want that””.

(participant 2)

(36) “Perhaps they have already tried on multiple solutions which can help express what that person prefers.” (participant 5)

23 Other healthcare professionals lack general understanding of AFOs

Three participants expressed the opinion that other health professionals do not have the same amount of knowledge and understanding related to AFOs within post-stroke patients as CPOs. Other professions may have had trouble understanding how minor AFOs, e.g., a Dictus, could limit the musculature and how AFOs should support, but not overtake the function of the muscles. CPOs identified this lack of understanding and knowledge in AFOs as a call for further education of other health professions, or at least the involvement of the CPO within early rehabilitation.

(37) “...and there must be some ignorance about minor helping aids such as a Dictus or Boxia you attach to the shoe. I have a pretty hard time understanding that they can decrease the musculature around the ankle.” (participant 4)

(38) “...If it is a hospital with orthopedic departments it, perhaps, has more economical space as the orthopedic surgeons would understand it [orthotic need]. But yes, as soon as it is within the hospitals, and a doctor would have to prescribe it, it can be a little tougher depending on where you are.” (participant 1)

(39) “I see that there are different opinions on how to use an assistive device and, like with the doctors, there is also an opinion that if the patient needs it or if the patient can’t recover more, without the assistive device being a disservice to the patient nor taking over the physical function.” (participant 3)

Psychosocial factors related to the patient

Psychological and physical challenges related to post-stroke patients were described by half of the participants as barriers in the use of AFOs during the early rehabilitation process.

A stroke patient may have physical barriers, such as spasticity or hemiparesis, which could contribute to why they might reject an orthosis, as this type of functional deficit might challenge donning of the orthosis for the patient. Furthermore, a common sequelae of stroke is cognitive difficulties, which might impede an otherwise straight forward orthotic treatment.

(40) “You could also provide a posterior shell plastic AFO as it has the abilities of a shoehorn, getting the foot into it. But they do not have the power [strength] to use it. It is extremely difficult to get the foot correctly into it [shoe and othosis] with only one arm.” (participant 2)

24 (41) “In the early phase it is difficult to say where the foot ends in regard to spasticity.” (participant 1) (42) “...within the stroke patients a lot has cognitive problems” (participant 4)

Dissatisfaction amongst CPOs with their role in post-stroke rehabilitation

The different perceptions on the role of CPOs in early post-stroke rehabilitation was addressed throughout the interviews. They questioned their role as CPO’s if they should or should not have, which competences CPOs can provide to a multidisciplinary team, and if they should be included in the early post-stroke rehabilitation multidisciplinary team.

AFO treatment not handled by CPOs in early rehabilitation

Regardless of the experience and knowledge regarding AFO's within early post-stroke rehabilitation teams, CPOs are only involved in severe cases where physiotherapists have not themselves been able to

adequately train and treat the functional deficit. This current approach has led to at least one case of a participant questioning their role as a CPO, they had been subjects to instances where physiotherapists had taken over the full early orthotic management, implying that their skills as an orthotist were not needed. Other participants [4] addressed similar instances regarding the relevance of the CPO in treatments, as other healthcare professionals are gradually increasing their active role in guiding the selection of orthosis, overriding the biomechanical knowledge that CPOs could have contributed with.

(43) “Only if the physiotherapist needed advice or guidance in relation to training with an AFO. Now that they have the AFOs, how should we then contribute?” (participant 4)

(44) It’s about the reform of rehabilitation, if they [healthcare professionals in rehabilitation] have knowledge about all the different assistive devices… it’s a completely different group of healthcare professionals?... It would be hard, in this way, to find a better solution, if those guiding don't know all the products. And for good reasons they don’t.” (participant 3)

(45) “The doctor has written, for example, what he sees and sometimes suggested the type of assistive device.” (participant 6)

25 The potential inclusion of CPOs in multidisciplinary teams

Other healthcare professionals are currently solely responsible for early orthotic management and

treatment plans. Almost all participants expressed a desire to be included in the early rehabilitation of post-stroke patients on a regular basis. Two of the participants identified the need for an orthosis to be

administered during the acute- and very early in the subacute phases when the patient is first hospitalized or brought out of bed for the first time post-stroke. More than two [3] of the participants had a suggestion related to the potential of a rehabilitation team, where a CPO, physiotherapist or occupational therapist should be in charge, and where the main focus of this multidisciplinary team should be on the most optimal patient related outcome. One of the participants emphasized that the CPO would have a greater

understanding of the biomechanical effect of the AFO than physiotherapists, and that this could greatly contribute to the outcome of a multidisciplinary collaboration.

(46) “...[leaders to the] rehabilitation team, whether it should be a CPO, a physio or an occupational therapist… One can wonder and ask oneself why there isn’t… There is a clear potential anyway.” (participant 2)

(47) “There is no regularly scheduled procedures and meetings within that part of the rehabilitation plan, and it would have been nice if there was.” (participant 5)

(48) “I think that we should enter rehabilitation from the moment that the physiotherapist brings them out of bed and identifies “oh, I can’t train with the person without an AFO”.” (participant 4) (49) “We could be much more involved, and it could have been fun to be a part of the rehabilitation.”

(participant 6)

(50) “When the knee is unstable… many have a tendency to hyperextend and I'm thinking that the biomechanical knowledge we have about an AFO can support the knee joint as well.” (participant 1)

Facilitators to the use of AFOs in early post-stroke rehabilitation

The CPOs identified facilitators in AFO usage during the early post stroke phase, including the widespread opinion that if implemented quickly, AFOs could assist in stabilizing unstable joints, a physical result of the stroke. Some private companies have chosen to invest in AFOs for the rehabilitation clinics, which allows

26 these clinics to use them alongside other rehabilitation training, as well as temporary independent AFOs, most likely improving the rehabilitation outcome of the patient regardless of their cause of treatment combined.

Two participants mentioned that physiotherapists at these neurorehabilitation clinics and/or centers were more supportive towards the use of AFOs in early post-stroke rehabilitation, and that the CPOs were often more included in the multidisciplinary team at these clinics when needed, than otherwise experienced in the public sector.

Investments in temporary AFOs

Four of the CPOs described how very few private companies and municipalities have invested in buying temporary orthoses for the rehabilitation centers. The disparity of temporary orthoses is even starker in the public sector, as, once again, it is left to the municipality to determine based on their assessment of needs, and the financial cost, to determine the necessity for an investment in orthoses in general.

(51) “...It helps a lot if we support them [patients] around the ankle… even though it does not cross the knee joint. Not all physios’ understands that.” (participant 1)

(52) “Sometimes there are temporary AFOs in the municipalities.” (participant 3)

CPOs opinion regarding the role of AFOs

In general, the early implementation of AFOs post-stroke was largely encouraged and suggested by all the CPOs. Some suggested that AFOs should be implemented within the early post-stroke training phase, as it would allow for physiotherapy and AFOs to collaborate throughout the whole rehabilitation, without either one excluding the other during the process. The AFO should serve as a training tool, helping and supporting the patient. More than half of the participants found making the post-stroke patients walk around without orthoses to be a bad idea, as they would not be able to ambulate safely, lacked the necessary stability, and suffer from an unwanted increase in energy consumption during gait with potential consequences for further recuperation.

(53) “...It has to be pretty early as they [physiotherapists] can not get them [patients] up and mobilize them unless they are stabilized.” (participant 4)

27 (54) “I don’t think that it [orthosis] can be replaced, physiotherapy and orthoses would have to go hand

in hand.” (participant 5)

(55) “...in the start I would think of it as an assistive device...” (participant 1)

The patient related benefits of AFOs early post-stroke

Most of the participants [4] were found to have a substantiated opinion about how an AFO could benefit the physical function of a patient, and how potentially increasing its implementation throughout

rehabilitation, could lead to change in orthotic needs in patients.

(56) “It is the stabilization. If they [patients] are not stabilized, they can’t stand and walk. To wear an orthosis makes good sense.” (participant 4)

(57) “It is hard to say if it [AFOs] should be involved in early rehabilitation or if you should wait and see how much help is required… Perhaps you [patient] get sufficiently good at walking and therefore not need it, but if it is not present during rehabilitation you will never find out.” (participant 3) The relevance of the orthotic need should be thoroughly and continuously evaluated to avoid the

treatment exceeding the patient’s needs. One CPO stressed the importance that they not excessively treat the patient if the need for treatment is not present.

(58) “I think that if there is a need then something should be applied, and I am not supporting excessive treatment if there is no need for treatment.” (participant 5)

Healthcare professionals in neurorehabilitation

Less than half of the participants [2] acknowledged the support that the multidisciplinary team at the neurorehabilitation showed towards the use of AFO in the early post-stroke rehabilitation. They highlighted that physiotherapists at those locations were not avoiding using AFOs when needed and that the existing teamwork included the CPO.

(59) "Those neuro physiotherapists at the rehabilitation centers… I think they’re good...They don’t have the perception that AFOs should be avoided at any cost.” (participant 4)

28 (60) “Many of the places we visit it is a collaboration with the physiotherapist at that specific location

on what would be good.” (participant 1)

Saturation

For this qualitative study, saturation was reached after the analysis of the data from the 4th interview, as no new themes emerged from the data after this (Schreier, 2014).

Discussion

Method discussion

A qualitative study with an inductive approach was used to address the aim of the study. The participants of this study were recruited through phone calls to all Danish companies. There is no right way of sampling participants in qualitative research and a common mistake, also found within this study, was the lacking amount of participants willing to participate and underestimation of the time needed to recruit these (Archibald and Munce, 2015). However, during the follow-up phone calls the researchers paid attention to their choice of words as they aimed to be objective and not persuade possible participants. This was done to keep in mind the comments from the review by The Research Ethics Committee at Jönköping University of this study. As the researchers were Danish and the reviewing letter was in Swedish, the researchers asked for an English version and focused on what they were able to translate and understand. Upon this, changes in the letter of information were done, ensuring that the last three participants received a reviewed version.

In total, six participants were recruited and interviewed with semi-structured, open-ended questions, to allow participants to express their opinions and examples without being interrupted, which allowed the researchers to gain a deeper understanding of the phenomenon of interest. Furthermore, the participant was given the opportunity to express themself fully during individual interviews. Another type of method which could have been used was with focus groups, in which participants with relevance to the purpose of the study would have been gathered to discuss their opinions. An advantage of focus groups interviews is that many different opinions and feelings are addressed. A possible disadvantage using a focus group is that someone can feel the need to suppress their opinions or feel overruled (Morgan and Hoffman, 2018). After a thorough discussion between the researchers, and due to Covid-19, the researchers decided to use individual interviews as their data collection method. The validity of this study could be considered low as the interview questions used were not validated (H.I.L. Brink, 1993). To address this the interview questions

29 were reviewed by Nerrolyn Ramstrand and Paul Charlton. The researchers chose not to include validated interview questions, as these questions did not address the aim of this study satisfyingly.

A sample size of six participants was considered to be sufficient to describe the current situations related to use of AFOs, and role of orthotists, in early post-stroke management and to explore perceptions of Danish orthotists regarding the use of AFOs in early post-stroke management, fulfilling the goal of this research, and to conclude upon these findings (Schreier, 2018). This as data saturation was reached after analyzing only four interviews.

The geographic spread in the participant sampling is a limitation of this study, as half of the participants were from the same region of Denmark. However, this also could be a problem regarding the results of this study, as it may miss important perspectives and the results can’t be generalized, as all participants were found to share similar experiences related to the phenomenon, possibly due to their geographical proximities. Nonetheless, a larger spread in geographics of the participants would have been preferred by the researchers, as they wanted to use a maximum variation of sampling (Guest, Namey and Mitchell, 2013).

All interviews were recorded over Zoom as Covid-19 restricted face-to-face interviews. This resulted in some complications related to internet connection and at times, troubles hearing each other during the interviews. Internet problems also caused awkward pauses between the interviewers and the participants, as conversational delays occurred. Furthermore, these delays also resulted on occasion in interviewers and participants speaking at the same time. This sometimes made the participant stop talking about possible relevant information and may have compromised the quality of the interview. The interviewers may be perceived as poor listeners, which may have been viewed as disrespectful by the participants (Roulston & Choi, 2018).

Recordings were also subject to missing sections or sudden changes in the speed of participants' speech. When this was found to have occurred in the recordings, both researchers sat down together and re-listened thoroughly to the affected parts of the interview. This was done to ensure the highest level of data possible was able to be included in the transcriptions.

During one of the interviews, one of the researchers was not available and this interviewer only attended five out of the six interviews. On this occasion the interviewer was at a disadvantage, as they had to manage technical requirements and the interview at the same time, both with some difficulty. For the

non-30 participating researcher, this resulted in the need for increased time for familiarization with the collected data, as familiarization with the data is crucial to increase credibility (Graneheim & Lundman, 2004).

Data analysis

An inductive content analysis was chosen as this study aimed to describe the current situation related to use of AFOs, and role of orthotists, in early post-stroke management and to explore the perceptions of Danish orthotists regarding the use of AFOs in early post-stroke management, where no previous literature was found to be existing, as the inductive method allowed for new knowledge to arise during the data analysis within a previously unexplored field. This is done through the identification of patterns, creating new knowledge, emerging from the collected data, while ensuring that the researchers stay close to the text (Kennedy, 2018). Furthermore, the researcher found alternative methods to build on already existing theories, or investigate the truth of these, and did thereby not find them to answer the aim of the study. Content analysis and its five steps were presented in the methodology. The analysis method was chosen as it allowed the researchers to describe and present the phenomenon of interest objectively within the scope of their work. That being said, there exists a potential risk in the exploration of data by the researchers, where they could wind up drawing conclusions on derived meanings that are not actually substantiated (Graneheim and Lundman, 2004). To decrease the risk of exploration and misinterpretations, and to increase the credibility, the researchers chose to familiarize themselves with the data in this manner, taking the time to re-read the interviews in an effort to gain a deeper understanding and knowledge of subjects discussed within the collected data. Appropriate meaning units in relation to the purpose of this study were then selected with the intention of increasing credibility and thereby the trustworthiness of the study (Elo et al., 2014).

The researchers went through the coding of data at different times on multiple occasions, without noticing changes within the analysis and coding, thereby they would confirm their initial dataset, ultimately

increasing the reliability of the coding of the data (H.I.L. Brink, 1993).

Due to mishaps during the first dataset analysis showed that the researchers were very homogenized in their analysis process, as they had ended up creating almost identical codes, categories and sub-themes whilst working independently. The fact that the researchers were agreeing from the beginning have been identified as a strength for this study and is the reason why they subsequently chose to stay this course for the remainder of their study. Add to that, their lack of needs for a natural third party to resolve

31 disagreement, it must be concluded that the research and this study is dependable and trustworthy, moving forwards.

Result discussion

The aim of this study was to present the perceptions of Danish orthotists regarding AFO use early post-stroke management and furthermore to describe the current situation related to use of AFOs, and role of orthotists, in early post-stroke management. Throughout the interviews that were conducted, the most common statements were in relation to the barriers and facilitators related to the use of AFOs early post-stroke.

Current practices regarding AFO use post-stroke

Orthotists reported that they were rarely involved in post stroke management and, in most cases, only became involved in stroke management after the patient's condition had stabilized and their initial rehabilitation had ceased. A number of barriers to AFO use early post stroke were identified including health policies and how this affects the process of the grant, the attitude of the municipalities towards CPOs, a financial grey-zone, non-supportive physiotherapists towards early post-stroke orthotic management, and non-involvement in multidisciplinary teams and the effects on the patient.

Orthotists involved in this study indicated that they were rarely involved in management of stroke in the early phases of rehabilitation mainly due to the Danish health legislation and policies. Patients seeking an assistive device in Denmark are required, according to Danish health legislation, to fulfill at least one of the three requirements of paragraph §112 (Danske love, n.d.), of which nearly all participants highlighted the first of the three requirements. These are:

1) that it can significantly, relieve a permanently decreased functional level, 2) that it can significantly, ease daily life at home or

3) is necessary for the individual to obtain a job

The current law also stipulates that the physical state of the patient must be stable. As a result of

paragraph §112, post-stroke patients are not eligible for an AFO, or any other assistive devices during the early rehabilitation period, as they will not be classified as physically stable. Paragraph §112 was

highlighted by all participants during the interviews to be the most significant limiting factor in terms of preventing the early implementation of AFOs in rehabilitation. For this same reason, participants have

32 mainly only been able to hypothesize how an AFO could support the recovery of post-stroke patients when applied in the early stages of rehabilitation as all participants felt that AFOs would have a positive effect. In Denmark, municipalities are in charge of planning the rehabilitation process and economically decide how to prioritize treatment. One participant voiced concern that municipalities had a hard time comprehending and accepting the natural change in orthotic needs amongst post-stroke patients as they recovered. Furthermore, the participant argued that the current structure would actually decrease chances of a second grant, if this was applied for within a short period of time after the first. This concern seemed to be supported by the other participants, who also argued that it might be linked to the educational level and specialized knowledge of the individual case workers handling AFO funding application cases within the municipalities. It seemed like the participants, despite the possible and hypothesized increased functional benefits that could occur if approved, found it overwhelmingly impossible to argue against paragraph §112 rulings with the municipalities regarding AFO grants.

A doctor's referral or written statement is not a required part of the assistive device funding application. Interestingly, however, a written statement by the doctor was found by half of the participants to significantly increase the chances of getting an assistive device approval prescribed. This appeared as though some municipalities question the professional knowledge of the CPOs, according to the researchers, by requiring a validation of their assessment in form of a written statement regarding the functional deficit to prescribe an assistive device by a medical professional they trust. The prevalence of this assertion has not been investigated within this study but was noted with curiosity by both researchers.

Participants described how patients who were transferred between the hospital and municipalities might end up in what the CPOs called a financial grey-zone (Danish: betalingshul). They addressed this as a problem as the patient would end up without an orthosis until this was solved. To the researchers, this seemed like a flaw in the rehabilitation process. The participants described how patients were dropped due to either problems regarding the financing of the assistive device, a rejection of the funding application of an assistive device as their physical state is not stable or were unaware of one’s own needs as a result of lack of information. Nevertheless, this was found by the researchers to at least call for acknowledgement of AFOs in early post-stroke rehabilitation.

All but one participant addressed the dilemma related to physiotherapists and their lack of support for the use of AFO’s early post-stroke. This one participant who did not raise the issue had no direct cooperation with physiotherapists in the field, and did not work at, or visit, the rehabilitation clinics. Physiotherapists

33 were commonly described as discouraging use of AFOs for training or dissuading the patient from wearing an orthosis after the end of rehabilitation. Tyson (2018) suggested that there was a decreased clinically proven benefit of using AFOs with this category of patients. That article's content, however, was questioned by Kirker and Tylor (2018) who used scientific evidence to demonstrate how an AFO indeed could give higher clinical benefits within post-stroke patients. They argued against Tysons’ conclusions, ultimately questioning her understanding of AFOs. Half of the participants suggested that the

physiotherapists might discourage the use of orthosis early post stroke as they would rather train without orthosis, as they were found to think that orthosis works against their muscular rehabilitation, as these are possibly limiting and immobilizing joints. The physiotherapist seemed to, according to the participants, ignore the clinical benefits that AFOs have been proven to have on post-stroke patients, probably due to their education and understanding of these, possibly hindering them in seeing the advantages of orthosis within rehabilitation, which was also addressed by the participants. This issue was also addressed by Kirker and Tylor (2018) towards Tyson (2018), validating this assumption further. Nonetheless, the stabilizing effect of AFOs was found to be superior to barefoot walking in post-stroke gait (Pongpipatpaiboon et al., 2018; Kesikburun et al., 2017).

All participants described a common feeling of not belonging to, or feeling detached from an otherwise multidisciplinary team, as CPO involvement was limited to after the patient’s rehabilitation phase has concluded. According to Jorge (2019), a multidisciplinary team should be able to treat and manage patients with neurological and/or physical impairments. The skills and knowledge of each member in the

multidisciplinary team should maximize the rehabilitation and patient management. Results of this study suggests that the CPOs are currently not involved in early post-stroke rehabilitation, as no other health professional acknowledge their role and importance to the team, and thereby may oversee the need for the correction and support needed to accommodate for the decrease symmetric gait that patients might have. Furthermore, the participants found that the physiotherapists were managing the early post-stroke orthotic treatment, which the researchers identified could possibly compromise with the adequate and required orthotic treatment. Epstein et al. (2010) suggested how a multidisciplinary team should consist of well-coordinated healthcare professionals. One single healthcare professional can not encounter the skills of an entire team, neither should he or she, but the expertise of each member is crucial for the patient's care. The participants found professionals already acting within the multidisciplinary teams might have different focuses on the rehabilitation process, according to their own profession and expertise, supported by Epstein et al. (2010) and Jorge (2019). Currently, as the multidisciplinary team is solely responsible for the planning and scheduling of the patient’s rehabilitation, leaves a potential risk that they may overlook

34 the need for CPO skills and abilities, eliminating the chance for a CPO to get in contact with the patient. This may be viewed as a critical flaw in the rehabilitation process, as the patient would then have to hear about orthosis elsewhere, and subsequently have a potentially hard time coming to terms with the need for AFOs. This was the strongest motivational factor in urging for the implementation of CPOs in multidisciplinary teams according to the participants.

What are Danish orthotists perceptions of the role AFOs, and orthotists should play in early post-stroke management?

Orthotists in this study reported that they found that the patient would benefit from their involvement at a much earlier phase. They felt that their provision of an AFO during the early stages would stabilize the patient and decrease the energy consumption of the post-stroke patient during ambulation. To facilitate early orthotic management, participants suggested national guidelines, where orthosis and training should be used in combination, as a result of the collaboration between physiotherapists and CPOs within a multidisciplinary team.

Currently, within the “Snitfladekatalog” (in English: index catalog for rehabilitation of brain injuries) (Region Hovedstaden, 2014), the involvement of CPOs is not included for the rehabilitation of brain damage and the early post-stroke orthotic management in Denmark is managed exclusively by other healthcare

professionals. Each municipality is afterwards allowed to base their economical prioritizations and decisions regarding rehabilitation upon these catalogues and are allowed to limit their decisions to what is presented in the guidelines. This allows for great variance within the rehabilitation across the country as a whole. Some of the participants suggested that to ensure equal treatment for all patients would require either the creation of national standardized guidelines, that the state and municipalities reprioritize economically within the rehabilitation, or a change in the use of “Snitfladekataloger”. If indeed, changes were to be made to the current treatment process, Denmark could draw inspiration from countries such as Scotland, United States and the United Kingdom. National guidelines such as the Royal College of Physicians (2016), the NHS Quality Improvement Scotland (2009), and Winstein et al. (2016), have orthotists enrolled in early post-stroke management and rehabilitation, where they are used to provide AFOs early post-stroke when needed, alongside the other medical professionals.

Although the participating CPOs in this study did not directly address how their specific role should be in early post-stroke rehabilitation, the literature suggested that the skills of each health profession should not be handled by other professions (Epstein et al., 2010; Jorge, 2019), indication that the role of the CPO in