Department of English Bachelor Degree Project English Linguistics

Spring/Autumn 2019

Which Foot Forward?

An analysis of footing in the Dungeons &

Dragons stream Critical Role

Which foot forward?

An analysis of footing in the Dungeons & Dragons stream Critical

Role

Emma Lindhagen

Abstract

Tabletop roleplaying games are a type of social, narrative game driven by a group conversation in which a narrative which is co-created by the participants and propelled forward by some mechanical component (for example dice rolls used to determine the narrative outcomes of actions). As mode of spontaneous conversation that has a unique set of specific characteristics, it might be fair to claim that TTRPGs constitute a unique oral genre (or, in conversation analytic terms, a unique speech-exchange system). One of the most notable characteristics of TTRPGs as conversations is the intensive use of footing shifts. As the players alternate between orienting toward the conversation as players of a game with mechanical components and as co-creators of a joint narrative, various different resources are used to signal what footing a particular turn-at-talk is produced from. Using video from Critical Role, a live-streamed Dungeons & Dragons show, this paper examines the use of footing in TTRPGs and what resources are used to signal these.

The results of the study showed that several different types of footing were used in this material, with a large amount of overlap between them. Though it was possible to identify the primary resources for signalling some of them, for others it was not clear.

Keywords

Conversation analysis, tabletop roleplaying games, dungeons and dragons, footing, footing shifts, conversation, gaming

Contents

1. Introduction ... 2

2. Background ... 2

2.1 Table-top Roleplaying Games ... 2

2.1.1 Dungeons & Dragons ... 3

2.1.2 Critical Role ... 4

2.1.3 Academic Studies of Table-top Roleplaying Games ... 4

2.2 Footing ... 5

3. Materials and method ... 6

3.1 Materials ... 6 3.1.1 Material selection ... 6 2.2 Material Description ... 7 3.2 Conversation Analysis ... 8 3.3 Method ... 9 4. Results ... 9 4.1 Footing ... 9 4.1.1 Player Footing ... 11 4.1.2 Narrative Footing ... 13 4.1.3 Character Footing ... 15 4.1.4 Arbiter Footing ... 17 4.1.5 Exposition Footing ... 18 4.1.6 Social Footing ... 19 4. Discussion ... 20 References ... 22

Stockholms universitet 106 91 Stockholm Telefon: 08–16 20 00 www.su.se

1. Introduction

In recent years, tabletop roleplaying games (TTRPGs) have become more popular, the rise in streaming as a medium has allowed such games to become a spectator sport (Brodeur, 2018). Through live streamed shows on the web, viewers from across the globe are able to familiarize themselves with different game systems through watching others play or simply use such streams as entertainment to supplement or replace more traditional forms of media. In addition, these live broadcasts and the resulting video material allow for easy access to large quantities of data to study.

TTRPG are, in the most basic of definitions, a type of social, narrative game driven by a group conversation in which a narrative is co-created by the participants and usually propelled forward and otherwise affected by mechanical components (for example, dice rolls are commonly used to determine the outcome of actions attempted in-narrative). As a mode of spontaneous conversation with a unique set of specific characteristics, it could be claimed that TTRPGs constitute a unique oral genre (or, in conversation analytic terms, a unique speech-exchange system). Despite this, though studies have been done on table-top roleplaying games in a few different fields, little attention has been paid to them from a linguistic or otherwise interactional perspective.

This study will attempt to answer the questions:

- What footings are found in TTRPGs, and what are these used for? - What sort of resources are used to signal what footing a player is using?

To answer these questions, an episode of the streamed TTRPG show Critical Role will be analysed using conversation analysis as a framework.

2. Background

2.1 Table-top Roleplaying Games

The term roleplaying game covers a wide range of different types of games in which players assume the role of a character in a fictional setting and then make choices to take that character through the events of the game. This ranges from electronic games like video roleplaying games (where players alone or in groups play through a mostly pre-set

narrative while advancing their characters) to highly physical experiences like live action roleplaying games or LARPs (where players physically perform their characters’ actions, often in costume).

Table-top roleplaying games, sometimes also called pen-and-paper roleplaying games, are

closer to LARPs on this spectrum but the embodiment of the player characters is generally limited to speech only, while other actions taken by the characters are conceptualized in a joint narrative space sometimes referred to as "the theater of the mind". The narrative is co-created by an ongoing conversation, through which the players determine how their

characters interact with the fictional world and the other characters. Mechanical elements of the game are used to progress the narrative and determine the outcomes of in-character

actions. Though some props, such as maps and other physical aids, may be used these generally do not extend to costumes or life-sized equipment as those used in LARPs. Though there is a lot of variation in the rules and mechanics between different role-playing games, usually the main mechanics involve using dice to determine success and failure of actions as well as one player filling a special role (often called the Game Master or GM) which frequently involves being in charge of the setting and being the arbiter of the rules of the game. Originally these games were played with a pen and paper, in person, and at a table (hence the name). Nowadays, using tablets or computers instead of pen and paper or even playing the game over the internet using microphones and webcams is becoming more and more common. Additionally, with the rise of platforms like YouTube and Twitch, which enable easy distribution of pre-recorded or live broadcast videos, some groups have taken to sharing their games with an audience which has the side-effect of making the material available for study.

2.1.1 Dungeons & Dragons

The most widely known table-top roleplaying game is Dungeons & Dragons (D&D), a fantasy-themed game thematically and mechanically focused on exploration, fighting monsters and finding treasures. The game was first published in 1974 and has had several new versions made with overhauled rules, the current edition being the 5th.

In D&D, the GM (also called Dungeon Master or DM in D&D contexts) is given a position of high authority within the game. They have authority over the fictional world, describing (or sometimes even creating) the setting and any events in it that are external to the player characters as well as embodying non-player characters or NPCs. Additionally, they are usually expected to have a decent grasp of the sometimes quite intricate rules and to make calls about how to interpret the rules. Socially, DMs are also often expected to keep the other players on-task and making sure the conversation doesn't veer too far from the narrative, though there is also a good amount of variation between different gaming groups on all these points.

Though the rules of D&D include a lot of precise details specifying the exact parameters of various spells and abilities, the basic mechanics are relatively simple. As the player

characters are created, they are assigned a range of ability modifiers determining their competency level when it comes to six basic abilities (Strength, Dexterity, Constitution, Wisdom, Intelligence and Charisma). These are further modified by various choices made when constructing the character, and other skills, abilities and traits are also determined during this time. Once the narrative has been set into motion, the players decide how their characters will interact with the fictional world. Any in-character action that the DM determines to be difficult will trigger a roll of a 20-sided die, and the result will then be modified by the character's ability modifier in the relevant ability. For example, when an action using the Strength ability is taken, a character built to be strong will get a positive modifier to the result of the roll, while a character who has a low Strength modifier might have no modifier or even a negative modifier. As such, how a character is built will increase or decrease their chances of succeeding at particular types of actions. Other sizes of die are also occasionally rolled, though they are mainly used to determine the amount of damage caused by a combat action or the amount of health restored by a healing spell.

The bulk of mechanical gameplay is centered around combat, although dice rolls are also used to determine the outcomes of non-combat actions at the DM's discretion. For example, a player trying to convince an NPC to take a course of action maybe be asked to make a Charisma-based roll and one trying to pick a lock may be asked to make a Dexterity-based one. Apart from these occasionally prompted rolls actual roleplay is fairly free-form and percentage of a game session spent on roleplaying as opposed to more mechanical activities varies greatly between groups. Games that are streamed online and watched by large

audiences often lean toward being focused on the narrative and the roleplayed interactions. Combat is usually but not always the propelling force for character advancement or

leveling, which allows characters to gain new abilities or improve existing ones as the game

advances.

2.1.2 Critical Role

Critical Role is a D&D show that premiered in March 2015 and has since then aired a new episode nearly every Thursday, with the current episode count inching close to 200. The game started as a home game among friends, and partway into the initial campaign (a term often used in TTRPGs to signify an adventure or a set of consecutive adventures played by the same group of players, using the same rules set, setting and, typically, the same

characters) they began streaming it for an audience. The show was met with enthusiasm and today it is one of the most popular live-streamed roleplaying shows.

The main cast is comprised of 8 people: Laura Bailey, Taliesin Jaffe, Marisha Ray, Travis Willingham, Sam Reigel, Liam O'Brien, Ashley Johnson and DM Matt Mercer; however, Johnson has been absent from large parts of the second campaign so far, including the episode analyzed in this study. All cast members are professionally active in the

entertainment field and particularly in voice acting. Their interest in acting and storytelling leads the show to be very roleplaying heavy, and the game is played in a homemade world of Mercer's own creation.

2.1.3 Academic Studies of Table-top Roleplaying Games

In general, only a few academic studies have been done on TTRPGs, mostly in the fields of psychology, pedagogy and communication.

The earliest papers on the topic tend to be in the field of psychology and often involved trying to determine whether players of table-top roleplaying games are different from a control group in terms of various psychological tendencies. For example, Carter & Lester (1998) found no difference in the rates of depression, suicidal ideation, psychoticism, extraversion, or neuroticism between D&D-players and "unselected undergraduates", while Abyeta & Forest (1991) found no correlation between playing D&D and self-reported criminal behavior. Meanwhile DeRenard & Kline (1990), in a survey of 35 players and 35 non-players, found that more players expressed feelings of cultural estrangement but fewer expressed feelings of meaninglessness, compared to non-players. It may be that these studies came about as a response to a period in the 80s and 90s when there was fairly wide-spread concern (chiefly among parents of players) that D&D and similar games could lead to violent behavior or even encourage devil-worship. According to Waldron (2005), the various consequences of this moral panic (which included the game being banned at

schools and young players being harassed) actually led to an increased sense of community and shared identity among those who played TTRPGs.

In recent years, a small number of papers have been published on the potential pedagogical usefulness of table-top roleplaying games. Cheville (2016) speculates around ways in which academic curricula could draw on such games to create curricular structures that are more engaging and stimulating to university students while allowing for a greater degree of narrative agency. Meanwhile, Carter (2011) describes a D&D-inspired game design project which seemed to lead to positive outcomes both in terms of academic performance,

enthusiasm and involvement for the students of a third-grade class, particularly those struggling academically.

Walden (2015) conducted an online survey of players of Dungeons & Dragons to explore the importance and appeal of the game to players. However, while this paper is concerned with communication in the wide sense, it does not examine it in the technical sense nor take an interest in linguistics.

Although some Conversation Analysis (CA) studies have been done on gaming, these have generally focused on analyzing conversation that occurs while the interlocutors are playing electronic games on a computer or video game console. Piirainen-Marsh (2010), analysing the interaction of Finnish L1-speakers playing an English-language video game, found that code-switching emerged as a key resource for a number of activities, including managing transitions between different activity types and co-constructing affect while playing. Some studies have also looked at conversations occurring while children play games. For

example, Björk-Willén & Aronsson (2014) explored how Swedish preschoolers interacted with each other and the game while playing video games, and found that they tended to animate the characters in the game, responding to them as if they were real, and that they reconfigured single-player games into multiplayer experiences by coordinating improvised responses to the game characters.

Additionally, a couple of CA studies have focused specifically on massive multiplayer online roleplaying games (MMORPGs), games designed to allow a very large number of players to play together in the same virtual world. Moore, R., Ducheneaut, N., & Nickell (2007) explore how the absence of resources such as real-time turns-at-talk, eye gaze and observable embodied activities hamper conversation in such games, while, Bennerstedt & Ivarsson (2010) showed that MMORPG players use completely different resources, such as the movement of virtual avatars or interactions with certain in-game objects, for projection of next actions.

However, all these studies have focused on gaming situations that are considerably

different from that of an TTRPG, where the conversation constitutes the bulk of the gaming experience. Overall, papers discussing TTRPGs from the perspective of linguistics, or which explore such games as being a distinct form of conversation or communication, appear largely absent at the present time.

2.2 Footing

The concept of footing was first established by sociologist Erving Goffman, who took an interest in the study of human communication. Specifically, Goffman (1981) defines footing as "the alignment of an individual to a particular utterance" either as speaker or as hearer (p. 227). Participants change footing over the course of a conversation as the way

they orient themselves toward the ongoing conversation changes. This change can be subtle or abrupt and may involve code switching or other linguistic markers like "pitch, volume, rhythm, stress, [and] tonal quality" (Goffman, 1981, p. 128). These shifts can be initiated by the speakers or triggered by a co-interlocutor.

Though not specifically linguistic, the concept has been used by various researchers to study how footing is used in different avenues of communication, for example in sign language interpretation. White (2014) shows that ASL interpreters make use of a sort of blended footing, which combines their own alignment as interpreters with that of the author whose speech they are interpreting, rather than shift clearly between footings. Later, Sterby (2018) did not find such a blended footing in the work of Swedish sign language

interpreters, but rather identified four distinct footings between which they switch. Footing switches occur frequently in informal (and formal) speech, though not always consciously. For this reason, it is particularly interesting to study footing shifts in table-top roleplaying games, since in this speech-exchange system there is at least a partially

conscious awareness of the existence of different footings. In fact, players know that some of the time they are speaking as their characters, and some of the time as themselves. Furthermore, they are aware that some artifacts that are relevant to the mechanical side of the game (such as dice) are absent from the narrative.

3. Materials and method

3.1 Materials3.1.1 Material selection

When selecting which streamed D&D show to study, I had a few practical criteria, the primary one being that the recording be of high audio and video quality. Games played over video calls introduce factors (such as delays and other connectivity issues) that may affect the way the conversation unfolds but that would be difficult to account for (or perhaps even notice) in an analysis. Therefore, games where the players are all in the same physical space were prioritized when selecting the material for this study. Additionally, some streamed games include a certain amount of editing and other production features like sound effects, props and sets. While it is difficult to say to what extent these elements affect the game talk, a game with less invasive production avoids those hypothetical complicating factors and as such a show with a simpler setup was preferred.

The selection of Critical Role as the subject of study was based partly on the criteria above, and partly on the existence of Critical Role Transcripts, a managed website with fan-generated transcripts made in order to provide the episodes with subtitling. Though not academic or linguistic in nature, the transcripts found there are nevertheless of high quality thanks to a thorough system of proofreading and editing put in place by those who run the site. As such, they can be used as a basis for study and for more technical transcription in order to save time.

Critical Role has close to 200 episodes at the time of writing, split over two different campaigns, each with its own set of characters, and 20-odd one-off episodes unrelated to the main campaigns. Due to the runtime of the episodes (usually 3.5 to 5 hours, with

around 30 minutes dedicated to announcements, pre-game chatter and a mid-point break) and the limited scope of this study, a single episode was chosen for analysis.

A few different factors went into the choice of which episode to analyze. Firstly, it had to be an episode with full fan-transcripts available online. Additionally, I wanted to use an episode that was a good representation of what is standard for the show. That meant

excluding episodes where members of the standard cast were missing or guest players were present, and episodes that deviated from the main narrative such as one-off side stories or holiday specials. Finally, I did not want to use one of the earlier episodes of the second campaign as I know from experience as a D&D player that it takes players a little while to settle into new characters. It is difficult to say whether these factors would result in the overarching conversation functioning differently, but in order to ensure the episode chosen was as representative as possible I thought it was best to avoid them.

Even after excluding episodes according to all the criteria above, over 100 episodes

remained. As there was no particular reason to choose one of these episodes over any other one, an arbitrary selection was made and the most recent fully transcribed episode as of April 2019 was chosen to serve as material for this study.

2.2 Material Description

The episode selected for this study was episode 42 of Campaign 2 of Critical Role, titled "A Hole in The Plan". In this episode, the player characters have found themselves pressured into joining the crew of a pirate ship and consequently become stranded on a pirate island. As they explore the island, they attempt to spy on the pirate captain they now serve in order to glean the location of a mysterious temple as well as gather information they could use to incriminate said captain in the eyes of those ruling the pirate island and thus facilitate their own escape from the captain's control. The part of the episode that consisted of actual gameplay was approximately 3.5 hours long.

The episode, like all Critical Role episodes, consists of an audio-and-video recording with cameras set up to provide a good view of all of the players, as seen in the screenshot below. The centerpiece of the set is a large square table, and the players sit along two sides of the table with the DM facing them. They retain the same seating arrangements throughout the campaign except possible when there are guest players. The center of the table is

sometimes used to display battle maps, which are visual aids used to keep track of where all the characters as well as enemies are during a combat encounter.

Figure 1. Sscreenshot from episode 42 of Campaign 2 of Critical Role, titled "A Hole in The Plan".

In figure 1 above Matt, the DM of the game, is seen in the top left. The top panel to the right features (from left to right) players Travis, Marisha and Liam and the bottom Sam, Laura and Taliesin. Occasionally, the camera crew will switch to alternative display modes either to show a subset of the players more closely or in order to show the audience what is happening on a battle map when relevant. However, no battle maps were used during this episode.

3.2 Conversation Analysis

Conversation Analysis (CA) is a research tradition chiefly concerned with studying naturally occurring conversation and particularly with trying to understand the structural underpinnings of such communication (Sidnell & Stivers, p. 2). CA was first developed in the 1960s by Harvey Sachs and Emanuel Schegloff as an offshoot of ethnomethodology. While it has influences from a range of different fields ranging from ethnology and anthropology to sociology, including Goffman’s notions of footing and participation frameworks, as well as philosophy and linguistics, it has very much grown to be a distinct academic field with an active research community. CA takes an interest only in the micro-level of interaction, focusing on how participants make sense of each other's actions and utterances rather than the wider social contexts in which these occur or theories these can be interpreted by. As such, it constitutes a radically emic (participant-relevant) approach to analyzing data and shies away from etic (researcher-relevant) approaches.

CA is concerned only with primary data in the form of naturally occurring conversations that are (usually video) recorded. CA thus works with primary data rather than self-reported data, such as recollected or invented material. There are several reasons for this methodological choice. First, constructed or prompted speech, even of a sophisticated variety, lacks much of the complexity found in naturally produced talk (Sidnell, 2010, p.

21). As such, studying such material would show a simplified picture that is not actually comparable to real-world interaction. Additionally, materials constructed for the purpose of being studied would no doubt be biased by the pre-conceptions about “how people really speak” held by whoever constructed the material. Furthermore, recorded materials can be studied again and again, and even shared among different researchers interested in different aspects of the data (Sidnell, 2010, p. 22).

Once the data have been recorded, multiple viewings of the recordings are done, until a specific interactional phenomenon emerges to the analyst’s attention. Focal excerpts presenting instances of the target phenomenon are then painstakingly transcribed using a complex transcription convention system (Jefferson, 2004) that aims at reproducing the talk itself (including disfluencies) and the prosodic features of its delivery (such as intonation and pace), under the premise that nothing is uninteresting a priori. The transcript is important not only as material to study, but in that the process of producing it allows the researcher to make detailed observations about the material. Only once these observations have been made does theorizing enter the picture.

3.3 Method

The video material was viewed alongside the fan-generated transcript. While viewing, light edits were made to the transcript to, for example, add back turns-at-talk that had been removed from the original transcripts (presumably in order to make the subtitles the transcripts were made for more legible and less confusing). The transcript was then color-coded, each turn-at-talk marked by what footing the speaker assumed, and notes were made about the signals used, the contexts in which they were used and more. Ambiguities were also marked.

As the material was examined and re-examined, a clearer view of the ways the different footings were used and signaled emerged (see section X.X - Footing), adjustments were made to how the material was marked and notes had to be revised.

Finally, some illustrative extracts were selected and transcribed according to CA transcription conventions. Only those extracts used in the paper were transcribed to this level of detail, due to time constraints, making this in one sense a study only partially employing CA methodology.

4. Results

4.1 FootingAs a semi-experienced D&D-player and long-time watcher of Critical Role and other TTRPG shows, I came into this project with some vague expectations of what types of footing I would be likely to find and how these would relate to one another. I had conceptualized these expectations as a sort of spectrum ranging from full to absent immersion in the narrative of the game. On one end would be utterances displaying direct embodiment of one's roleplaying personage, through direct speech as one's character, while utterances that are neither relevant to the mechanical nor the narrative aspects of the game (so called "table talk", social talk at the gaming table) would exist on the opposite. Between these would be points on the spectrum partial immersion in the narrative (indirectly

describing the actions of your character) and emerging from the immersion to orient toward the mechanical rather than narrative aspects of the game (such as dice rolling) would occur (see figure 2).

Figure 2. Illustration of author's conceptualization of footings in the material at the beginning of the study.

However, once the material began to be examined, I realized that this conceptualization was far too linear and did not sufficiently account for areas of nuance and overlap.

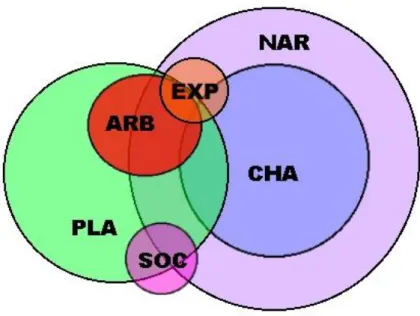

Figure 3. Rough conceptualization of footings and their relation to one-another, as found in the material.

Key for figure 3

PLA = Player footing NAR = Narrative footing CHA = Character footing ARB = Arbiter footing EXP = Exposition footing SOC = Social footing

As the above illustrates, several different types of footing were observed in the material (labeled with abbreviations above to make the graphic representation more legible). They will be briefly defined here, and then examined in more detail below. Two primary

footings, with considerable of overlap between them, could be identified: orienting toward the conversation as a player of a game, and orienting towards it as a co-creator of the narrative. The embodiment of a character through direct speech may be considered a subset of the footing orienting towards co-creation of the narrative, but nevertheless is prevalent and distinct enough to warrant being examined separately. The remaining three footings in the diagram are: orienting toward the conversation as arbiter of the rules of the game, as a member of a social group and finally as source of some pertinent bit of information (exposition).

Overall, footing work within the material was very dynamic with frequent shifts between them. Additionally, shifts into some a certain footing (particularly character footing, see below) by one player seems to frequently trigger shifts into that same footing by other players.

Below, each type of footing will be described, and a few examples1 will be given both of how they are used and of what types of resources are used to signal them. The examples will generally constitute clear cases, as there is too much material and too little space to cover all the nuances and ambiguities here.

4.1.1 Player Footing

Orienting toward the conversation as a player of a game that has certain set rules, lingo and mechanics constitutes stepping into what might be called "player footing". Player footing can be quite easy to identify, as it often makes explicit reference to items (for example, the character sheets that store the mechanical information about the characters) and concepts which do not conceptually exist within the narrative portion of the game. The most

concrete example of this is referring to the dice. While the dice are used to determine how a player action will be resolved within the narrative, the dice themselves do not exist inside the story being co-created. Yet they are frequently relevant to the overall conversation due to their mechanical importance.

Excerpt 1

In Excerpt 1 above, Sam and Laura have declared that their characters are trying to hide from some NPCs while sneaking across the deck of a ship and Matt, the DM, requests that they make a "stealth check" (that is, roll based on their "stealth" skill to determine how successful they are at hiding). Sam signals his move into player footing by issuing a direct response to Matt's request and then rolling his die in line 02. Laura, watching Sam roll, assumes player footing by reminding him that a mechanical effect (a spell called Pass Without a Trace, which gives players a +10 modifier on stealth rolls) is still in effect, prompting him to adjust his result upwards once he declares it in line 05. In line 08 and 09, Matt transfers the results of the rolls into the joint narrative by narrating the consequences (or, in this case, lack of consequences as the characters successfully move across the deck while remaining hidden). Though it is sometimes explicitly declared whether a roll has succeeded or failed, other times this is only implicitly indicated by what happens in the narrative.

1 Note that the examples have, per CA convention, been inserted into the document as image files in order to preserve

While player footing often involves explicit reference to game mechanics or features, this is not always the case and it may be signaled through more indirect means:

Excerpt 2

In Excerpt 2, the player characters (PCs) are observing a group of NPCs who are participating in a toast honoring a demigod worshiped by the pirate captain. Matt has

described the ambiance and general demeanor of the group, providing only information that would be immediately available to the PCs upon watching the scene. In line 01 Taliesin makes a request for additional information about the NPCs. In order to establish what his character Caduceus can glean from what he is observing, Matt prompts him to make a roll using the skill Insight, which is used for discerning things from people's behavior such as whether someone is lying or what their motivation is. Caduceus is known having an uncommonly high modifier in the Insight skill, which means that he is likely to succeed at this roll. In line 04, Travis joins in on the exchange through ironically suggesting Taliesin is "no good" at those. In doing so, he takes a player footing by signaling, albeit through irony, his familiarity with both the mechanics of this type of roll and with his co-player's chances of success, without directly referencing the mechanics of the game. The

assessment "no good" is upgraded, also through irony, by Taliesin in line 05 to "terrible". It is then further upgraded in line 07 where Travis demonstrates his belief that Taliesin will succeed at this roll through hyperbole, implying that he may be able to discern information that is not actually possible to discern with the naked eye (that is, the blood type of the NPCs). In line 13, Matt determines that this roll was high enough, and in line 15 he begins to give a lengthy answer on the topic (of which only the beginning is transcribed above). In both Excerpt 1 and Excerpt 2, it is the content of the utterance more than anything else that signals the footing being taken, and this appears to be the most common way to signal this footing overall. This can be done by directly referring to mechanics or rules as in Excerpt. 1, or more indirectly through displaying your familiarity with mechanics or rules without direct reference to them as in Excerpt 2. Other ways to indirectly signal that you are orienting toward the conversation as a player of the game might be by displaying your understanding of the consequences of a roll before they have been realized in the narrative, asking question about rules and mechanics, or otherwise demonstrating your

comprehension of some aspect of the mechanics. Additionally, player footing might be used to ask for clarification on a rule, or by asking the DM for permission to make a particular kind of roll.

4.1.2 Narrative Footing

For the bulk of the material observed, the conversational focus was either on the mechanical components of the game, as exemplified in the section above, or on the fictional narrative that is co-created by the participants. Although the narrative and the world it takes place in is imaginary, nevertheless it is oriented towards as a concrete entity, which they as players (and particularly Matt as the DM) have access to encyclopedic knowledge about and are able to interact with. That is, although the narrative is explicitly fictional, there are still things that are true or false within it and it has its own boundaries of what is possible and impossible. Additionally, it also has its own past, consisting of

previous sessions as well as autobiographical information decided prior to the game. While a lot of flexibility exists within these boundaries in terms of improvisation and "filling in the gaps", the narrative "reality" is never directly contradicted or broken.

Narrative footing is employed for a number of tasks, the most concrete of these being adding narrative details by describing whatever aspects of the narrative you have narrative authority over. For Matt, this includes the NPCs, the setting and the fictional world at large (including things like weather), and for the others this is generally confined to the direct actions of their characters and perhaps small details in their immediate vicinity.

Usually turns-at-talk such as these are produced in the present tense, in the 3rd person for Matt and the 1st person for the other players, and this grammatical form in combination with describing things happening in the narrative may be considered a signal for the narrative footing. Additionally, this describing use of the narrative footing often involves miming actions and other embodied actions like changes in posture and gesticulating. Excerpt 3

In the excerpt above, Marisha's character Beau has just palmed a note to a NPC. After providing a brief description of the NPC's general appearance and demeanor, Matt describes her reaction to this action in line 01, using mimed action as part of his

description. In line 07 Marisha responds to this reaction by describing Beau's subsequent actions, and in the next turn Matt continues describing those of the NPC. Using narrative footing to build on each others' turns, frequently combined with shifting into character footing (see next section), allows the players to create unfolding action spontaneously. In line 11, Liam demonstrates another way to use of the narrative footing, namely through providing assessments of the unfolding narrative, in this case by commenting on the actions of an NPC. Assessments and other commentary such as making comparisons with cultural references or joking about what is going on is a common way for the players to participate

in the co-creation of the narrative even when they don't have much narrative authority outside of their own actions.

The issue of who has the narrative authority to create certain actions within the narrative is a complex one and would require further study to untangle. Although it is clear that Matt is deferred to for any larger details of the fictional world and the NPCs within it, nevertheless the other players appear to have some amount of freedom to add things to the fiction outside of their characters immediate actions:

Excerpt 4

Excerpt 4 takes place in a rowdy tavern. In line 01, Matt is checking in to see what Laura's character Jester has been doing while another scene has just played out in the proceeding talk (something which he does relatively frequently over the course of the game with all of the PCs). In her response in line 02, Laura takes the narrative footing and states that Jester, who does not drink alcohol, has ordered some milk and that this milk is "disgusting". It should be noted that due to the distribution of narrative authority in this group, if Matt were to respond to her turn-in-talk by saying, for example, that the tavern did not sell milk or by requesting that she make a Persuasion roll to see whether the barkeep is willing to comply with such an unusual request, that would likely not be oriented towards as problematic. Additionally, he could have used her addition to the narrative to start a scene with her or further develop this new information. Instead, it is Liam who, in line 04 and 05, takes the opportunity to start an exchange by assuming character footing (see next section) and having his character Caleb comment on the milk, which leads to a conversation in the subsequent lines.

Apart from contributing to or supporting the co-created narrative, narrative footing is also used to ascertain one's understanding of the unfolding action, or eliciting more information about the narrative circumstance by asking questions:

Excerpt 5

In this excerpt, Taliesen's characters has just brought up a rather private topic, and in line 01 Travis appears to be on the verge of answering him in character footing, then thinks better of it and addresses Matt to ask if anyone can hear them. Although Matt could have asked Travis to make a Perception roll to get the answer, in this instance he simply

may also ask each other for details about their characters' actions or demeanor and Matt may use similar questions to ascertain his understanding of where everyone is or what they are doing within the narrative.

It should be noted that there is a great deal of overlap between player footing and narrative footing. While some conversation relevant entities only exist as a mechanical game element (such as dice or character sheets) and others exist only as narrative elements (such as the color of an NPCs clothing or other narrative detail), a large portion of the elements relevant to the conversation, perhaps the majority, exist both in the mechanical and narrative sphere, in varying degrees of concreteness.

For example, the spell Eldritch Blast, frequently used by Travis' character Fjord, exists in the narrative as a magical spell which causes a beam of crackling energy that impacts an enemy and injures them, while also being a mechanical move requiring the player to make an attack roll using their spell ability modifier (which varies depending on what class the character is, i.e. how the character is built mechanically) and deals 1d10 of force damage. Conversely, a narrative detail like the patrolling schedule for the guards in a particular town may become mechanically relevant depending on the actions of the players; if the PCs are trying to break into a building unnoticed, the difficulty of the rolls made to carry that out may be affected (at the discretion of the DM) by said patrolling schedule.

Planning sequences, where decisions are made about how to approach an upcoming combat sequence or other challenging endeavor, seem particularly prone to a great deal of blending between these footings, as both mechanical and narrative aspects are given consideration without sharp lines drawn between them. Occasionally, attempts are made to mitigate the blurring of the lines between player and narrative footing by redressing mechanical effects in narrative terms, but most of the time this blended footing is oriented toward as being unproblematic.

4.1.3 Character Footing

When playing D&D, as part of co-creating the narrative of the game, players also embody their character through direct speech. As such, this embodiment can be considered a subset of the narrative footing, however it is nevertheless distinct enough to warrant separate consideration.

The most noticeable signal for the character footing is the use of an idiolect distinct from the player's own, namely that of the embodied character. What signifies this character idiolect will differ from one character to the other, but may involve changes in speech speed, register, intonation, word-choice and phonology, including the approximation of regional dialects. For example, Taliesin embodying Caduceus involves, among other things, speaking more slowly and in a deeper register, while Liam uses a light German accent to embody Caleb. Due to the experience these particular players have with voice work, it is usually easy to hear whether the player or the character is speaking, although ambiguities do still occur particularly in cases where the two idiolects are fairly close, as is the case with Marisha and her character Beau.

Character footing can be assumed both within a turn and between two turns that are interposed by one or several turns by other players:

Excerpt 6

In line 01 of the excerpt above, Travis orients himself toward the narrative by asking Taliesin where his character is and Taliesin answers in line 03, both in their regular idiolects. Once the turn returns to Travis, after Matt has checked what some of the other characters are doing, he shifts from narrative to character footing in line 13 and switches into his character's idiolect partway through his turn. Taliesin begins his turn in line 17 already in his character's idiolect, taking the character footing too. Character footing is often shifted into sequentially like this, by one character including another in a nested conversation within the overall conversation of the game. In line 19, Travis shifts back into narrative footing to describe Fjord's actions, returning to his normal idiolect.

When a player makes an intra-turn shift from narrative to character footing, occasionally an explicit speech tag, such as "I say" or "I go", will be used:

Excerpt 7

In the above, Marisha's character Beau is talking to a guard (an NPC played by Matt). As Matt describes the guard's physical behavior in line 07, he then explicitly signals that he's shifting into character footing by using the phrase "[he] goes". Explicit lexical signaling

like this appears to only occur when a player is shifting from narrative footing to character footing in the middle of a turn. Since such intra-turn footing shifts are not very common and since it does not occur in all such turns (as we can see in excerpt 6 above), explicit signaling like this is fairly rare.

Of the footings observed in the material, character footing was the footing that was maintained the longest by the group without interruption, with segments of up to 2-3 minutes of sustained character footing occurring a few times in the episode. The other footings are rarely sustained for longer than a minute, and in most of the material footing shifts were far more frequent than that. Just as narrative footing and player footing can blend together in for example planning sequences, as discussed above, so can character and player footing blend together, with mechanical considerations being brought up even while character idiolects are still used. Likewise, as character footing is a subset of narrative footing, some moves that are usually done in narrative footing, such as asking questions about the setting, may sometimes be done in the character idiolect.

4.1.4 Arbiter Footing

Arbiter footing refers to footing that orients strongly toward being an arbiter of the rules of the game and, perhaps, also the internal truths of the narrative. As such, the footing is usually assumed after a roll has been made and used to decide whether the action that the roll represents has succeeded or failed. The arbiter footing may include an explicit

arbitration, such as "it hits" or "that misses", but the arbitration may also be implicit and the consequences of the roll presented directly in narrative footing:

Excerpt 8

In the above, Sam's character Nott is trying to open a locked drawer while poisonous gas is filling the room she's in and consequently Matt asks for a "lockpicking check" (a roll to determine whether the lock is successfully picked) in line 01. While Sam makes his roll, some of the other members use the narrative footing to assess the tenseness of the situation. In line 06 and 07, Matt enters arbiter footing obliquely, by miming trying to pick a lock that won't open. The subsequent statement "it's not opening" is ambiguous between an explicit arbiter footing and narrative footing showing the consequences of the roll.

Though Matt uses arbiter footing more than the other players, the footing is not unique to DMs as there are mechanical details about their own character that the other players are likely to have more awareness of and that they can therefor orient towards being an

authority on. Additionally, in some situations a player may remember a particular rule more clearly or quickly than Matt does and pre-empt him in entering arbiter footing, however this is not terribly common.

It is possible that arbiter footing may also be used to arbitrate on narrative rather than mechanical issues, functioning perhaps as a narrative footing which orients more strongly toward the narrative authority that the player possesses. For example, occasionally a use of the narrative footing by one of the other players will be explicitly rejected by Matt:

Excerpt 9

Before this exchange, the group have been informed of the contents of a notebook that they have stolen from a pirate captain. After Matt uses a turn-in-talk to tell them that the final note in the notebook mentions a member of their group, Fjord, who had become intimately entangled with the pirate captain, Sam jokingly provides an addition to the narrative in line 01. Although this turn-at-talk is facetious and solicits laughter form the other players, including Matt, Matt still explicitly rejects the utterance in line 02. Such narrative

arbitration is rare but does occur, and there are a lot of cases that may be considered either arbiter footing or plain narrative footing. Although no such case was found in this material, it is conceivable that narrative arbitration may be done by the other players too, on topics over which they have narrative authority such as the actions or backstory of their

characters.

Aside from arbitrations of rules or narrative, arbiter footing may be used to request that a mechanical action (such as making a roll) be taken and to manage the macro-level of the narrative such as by interrupt an attempted scene by another player and signalling the beginning and end of the game. It is not clear what the primary signal which sets arbiter footing apart from other footings is, or if perhaps the act of arbitrating is itself the primary signal.

4.1.5 Exposition Footing

Exposition footing refers to a subset of narrative footing wherein the speaker orients less toward co-creation of a narrative and more toward simply divulging information to the other players. It can be used for a range of things, such as describing a setting or an NPC, giving background information on a topic or depicting a short series of events with limited player interaction. Exposition footing may be entered spontaneously, for example when the characters have arrived at a new setting which needs to be described. However, it can also come as a result of a roll, as in the case of the Insight roll from Excerpt 2 above, where Matt enters exposition footing in line 15.

Although only Matt uses the exposition footing in the episode, it is theoretically possible for other players to do the same when sharing information about something they have narrative authority over. Additionally, exposition footing is distinct in that it is much more likely than other footings to include non-spontaneous materials such as pre-prepared setting descriptions or worldbuilding materials like for example, as was the case in this episode, a sea shanty.

The most notable thing about exposition footing is that it involves one person being the speaker for several consecutive turns with minimal interruptions. If other players produce a

turn-at-talk before the footing has been abandoned by Matt, it is generally at a lower volume and often entirely overlapped by Matt. If an interruption succeeds, the exposition footing is often resumed with added emphasis. This absence of narrative cooperation is particularly noticeable when the exposition footing is taken to describe something that is happening to or near the PCs (as opposed to a more stationary setting description or piece of background information), as in the excerpt below:

Excerpt 10

Here, Matt spontaneously takes the exposition footing as the PCs are leaving a tavern. Although he uses an NPC to explicitly interact with Laura's character Jester, no interaction, outside of reactions embodied through facial expressions, occurs before he has moved the NPC out of the scene in line 27.

Although Matt's manner of speaking appears to be a little more emphatic in exposition footing than in other footings, it is not entirely clear what it is that signals to the other players the current turn-at-talk is information they should pay attention to but not necessarily interact with.

4.1.6 Social Footing

Social footing refers to footing that does not orient toward the game mechanically or narratively, but rather toward the social bonds between the players. This may include mentions of shared experiences or shared cultural references, and displays of familiarity with each other’s personalities, tastes and preferences.

At the beginning of the study, I was expecting this footing to be very frequent in the material on account of how common teasing and social banter is between the players, but as the analysis progressed I realized it rarely occurs on its own and is usually blended with either narrative or player footing. When social footing did occur without significant

blending, it primarily consisted of commentary on some aspect of the physical setting, as below:

Excerpt 11

In this excerpt, a misunderstanding about the name of a recently introduced NPC, which Sam and Travis are joking about in lines 01 and 06 respectively, have prompted Marisha to update some information in her notebook. Laura, who has previously participated in the discussion about the name, notices Marisha's pen and shifts into social footing in line 03 to comment on it. Lines 08-11 maintain this footing by continuing to provide assessments on the pen, before Sam assumes character footing in line 12 and prompts Marisha to do the same by addressing her character directly.

4. Discussion

This study explores the types of footing found in an episode of the D&D show Critical

Role, from the perspective that intensive footing work is one of the most notable features of

TTRPGs as communicative events, as well as how these footings were signaled. The analysis carried out revealed that several different footings are found in the material, and that these footings overlap considerably with one another.

The two most expansive and central footings are player footing, which orients toward the mechanical aspects of the game, and narrative footing, which orients toward the co-creation of the narrative. Additionally, character footing is a frequently used subset of narrative footing which involves the direct embodiment of a character. Two more restrictive footings were also found, namely arbiter footing and exposition footing, both of which present as being less collaborative, more authoritative footings that focus on making arbitrations about the mechanics or narrative, and delivering information to the other players in a non-cooperative manner respectively. Finally, social footing orients toward being a member of a social group and primarily consists of joking or referencing joint experiences.

Although an attempt was made to use clear examples in the result section above, a large portion of the studied material could not be said to fit into only one footing. Blended footings were found to be very common, which somewhat goes along with the findings about the footing use of ASL interpreters in White (2014).

The types of resources used to signal a particular footing varied between footings, as did the degree to which a footing was consistently signaled in the same way. Character footing was the most consistent in its signaling, with the activation of the character's idiolect being the primary signal. Player footing was generally signalled by making explicit or implicit reference to the mechanical aspects of the game. Narrative footing seemed to use a variety of signals, the clearest of which being using the 1st or 3rd person and present tense.

However, this signal was only used when describing a character’s actions, and the signals used at other times were not clear. Arbiter footing appears to primarily be signaled by the act of arbitrating itself, while social footing was mainly signalled by references to the physical space or the shared past experiences, however this footing rarely occurred on its own. It is unclear what the primary signal for exposition footing is.

References

Abyeta, S., & Forest, J. (1991). Relationship of Role-Playing Games to Self-Reported Criminal Behaviour. Psychological Reports, 69(3_suppl), 1187–1192.

https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1991.69.3f.1187

Bennerstedt, U. & Ivarsson, J. (2010). Knowing the Way. Managing Epistemic Topologies in Virtual Game Worlds. Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW). 19 (2), pp. 201-230. Doi: https://doi-org.ezp.sub.su.se/10.1007/s10606-010-9109-8

Björk-Willén, P & Aronsson, K (2014) Preschoolers’ “Animation” of Computer Games, Mind, Culture, and Activity, 21(4), 318-336, DOI: 10.1080/10749039.2014.952314

Blackmon, W. D. (1994). Dungeons and dragons: The use of a fantasy game in the

psychotherapeutic treatment of a young adult. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 48(4), 624– 632. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.1994.48.4.624

Brodeur, N. (2018, May 4). Behind the scenes of the making of Dungeons & Dragons. The Seattle Times. Retrieved from https://www.seattletimes.com/life/lifestyle/behind-the-scenes-of-the-making-of-dungeons-dragons/

Carter A. (2011) Using Dungeons and Dragons to Integrate Curricula in an Elementary Classroom. In: Ma M., Oikonomou A., Jain L. (eds) Serious Games and Edutainment Applications.

Springer, London

Carter, R., & Lester, D. (1998). Personalities of Players of Dungeons and Dragons. Psychological Reports, 82(1), 182–182. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1998.82.1.182

Cheville, R. (2016) ‘Linking capabilities to functionings: adapting narrative forms from role-playing games to education’, Higher Education (00181560), 71(6), pp. 805–818. doi: 10.1007/s10734-015-9957-8.

Davidson, C. (2012). When “Yes” turns to “No”: Young Children’s Disputes during Computer Game Playing in the Home in Danby, S., & Theobald, M. (Eds.). Disputes in everyday life : Social and moral orders of children and young people. Pp. 355- 376. Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited.

DeRenard, L. A., & Kline, L. M. (1990). Alienation and the Game Dungeons and Dragons. Psychological Reports, 66(3_suppl), 1219–1222. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1990.66.3c.1219

Goffman, E. (1981). Forms of talk. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press. Jefferson, G. (2004). Glossary of transcript symbols with an introduction. In G. H. Lerner (Ed.),

Conversation analysis: Studies from the first generation (pp. 13–31). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Moore, R., Ducheneaut, N., & Nickell, E. (2007). Doing Virtually Nothing: Awareness and Accountability in Massively Multiplayer Online Worlds. Computer Supported Cooperative Work: The Journal of Collaborative Computing, 16(3), 265–305.

Piirainen-Marsh, A. (2010), Bilingual practices and the social organisation of video gaming activities. Journal of Pragmatics 42 (11), pp. 3012-3030. Doi:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2010.04.020

Sidnell, J. & Stivers, T. (Eds.), The handbook of conversation analysis, Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

Sidnell, J. (2010). Conversation analysis: an introduction. Chichester, U.K., Wiley-Blackwell. Sterby, P. (2018). Fotombyte i teckenspråkstolkning : Erfarna tolkars koordineringsarbete på

diskursnivå (Dissertation). Retrieved from http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:su:diva-160874

Walden, C. R.. (2015). "A Living and Breathing World...": examining participatory practices within Dungeons & Dragons. (MCS Thesis). Auckland University of Technology, Auckland, New Zealand.

Waldron, D. (2005). Role-Playing Games and the Christian Right: Community Formation in Response to a Moral Panic. Journal of Religion and Popular Culture. Volume 9. Accessed through the Wayback Machine on 15/5-2019:

https://web.archive.org/web/20130104131941/http://www.usask.ca/relst/jrpc/art9-roleplaying-print.html

White, J. A. (2014) ‘Cognitive spaces: Expanding participation framework by looking at signed language interpreters’ discourse and conceptual blending’, Translation & Interpreting, 6(1), pp. 144–157. doi: 106201.2014.a08.