Academic skills centres

in multilingual university settings in Sweden

Daniel Egil Yencken, MA, MTESOL Kathrin Kaufhold, PhD Academic Writing Service Department of English Room 159, Studenthuset B Room 810, E House

Stockholm University Stockholm University

1

Academic skills centres in multilingual university settings in Sweden

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Josefin Hellman, head of Studie- och språkverkstaden at Stockholm University, for her generous support and advice on designing the survey. We would like to thank Kristina Schött and Arlette Huguenin Dumittan for reading drafts of the report. We would also like to thank all the learning developers1 across Swedish universities who participated in the survey for their time and willingness to share their insights.

Stockholm, November 2020 Daniel Egil Yencken and Kathrin Kaufhold

Table of Contents

1. Introduction 2

2. Survey design 2

3. Survey results 3

3.1 The institutional setting of the work 3

3.2 Awareness of university language policy 3

3.3 Language use with colleagues and students 4

3.4 Strategies described for cases 4

3.4.1 Consultation strategies 5

3.4.2 Learning strategies 6

3.5. Internationalization and widening participation 7

4. Questions arising from the survey 8

References 9

Appendix I 11

Appendix II 17

1 There are many terms for this profession in Swedish (e.g. handledare, pedagog, pedagogisk konsult). We opted for “learning developer” because this seems to be broad enough to cover the different aspects of the profession.

2

1. Introduction

This report presents initial results from a survey aimed at learning developers working in academic skills centres2 at Swedish universities. The overall purpose of the survey was to gain insights into their perspectives on their work with multilingual students and in relation to higher education institutions as multilingual settings.

This report comes at a time of the sectors’ increasing professionalisation and consolidation. There have been a range of reports and studies in the past decade that testify to this development (e.g., Bjernhager & Grönvall Fransson, 2018; Nodén, 2019; Lennartson-Hokkanen, 2016). At the same time, higher education institutions have heightened their ambitions of internationalization and widening participation. These processes arguably contribute to an increased diversity in the educational and language backgrounds of students and staff. The Nordic Council of Ministers (Gregersen et al., 2018, p. 27) acknowledges this multilingual reality: “universities are more multilingual than ever“.

In the past decades, discussions around language use in Swedish higher education focused mainly on the relation between the national language (Swedish) and English as the academic lingua franca in terms of parallel language use. Current debates extend the concept and consider other languages used at universities (e.g., Kuteeva, Kaufhold & Hynninen, 2020). Despite the central role of academic skills centres to support academic writing development in multilingual settings, relatively little attention has been paid to these centres in terms of language policy implications. They are seen as essential in documents on widening participation (e.g., Swedish Council for Higher Education, 2016), which includes students with diverse language backgrounds. However, they seem to be merely subsumed under language, academic writing and pedagogic services in documents on language policy and

internationalization (e.g., Gregersen et al., 2018).

This report contributes perspectives from learning developers themselves to these debates. It

illuminates how learning developers perceive their work within Swedish higher education institutions as multilingual settings in the light of processes of internationalization and widening participation. The report constitutes a starting point for our ongoing study.

The report is structured as follows. After briefly outlining the questionnaire design, we present initial results with special focus on reported teaching strategies. These results raise a range of questions, with which we conclude the report. This report can only give a general account of the descriptions and reflections that have been shared by the study participants. We hope that presenting these results and raising these questions can contribute to the continuing professionalisation in the sector.

2. Survey design

The survey aimed at gathering learning developers’ perspectives on their work in multilingual university settings in Sweden. Because of this explorative aim, the majority of items in the survey are open questions. The questions are listed in Appendix I.

The questions focused on the following themes:

1) Background information on the institutional setting of the work 2) Language use with colleagues and students

2 These units cover a broad range of services and have a range of names in Sweden and internationally. It was

therefore difficult to find a simple term to cover all aspects of their work. In this report, we opt for academic skills centres as a term of reference.

3

3) Cases of consultation situations for Swedish or English text production to elicit tutoring strategies based on concrete examples

4) Perspectives on internationalisation and widening participation 5) Demographic information

The survey was introduced at a network event and an email reminder was sent directly to the academic skills centres. It was administered online using Google Forms. In line with good research practice, completion of the survey was anonymous and participation was voluntary. Participants were asked to avoid including any personal information.

3. Survey results

A total of 43 responses were recorded. We estimate the total number of practicing learning developers to be around 126 based on the number of members of the Sprak-och-textverkstader mailing list. Since the survey was anonymous, we cannot say how many academic skills centres are represented. 28 respondents commented on the example cases for Swedish-language consultations, and 15 commented on the example cases for English-language consultations.

3.1 The institutional setting of the work

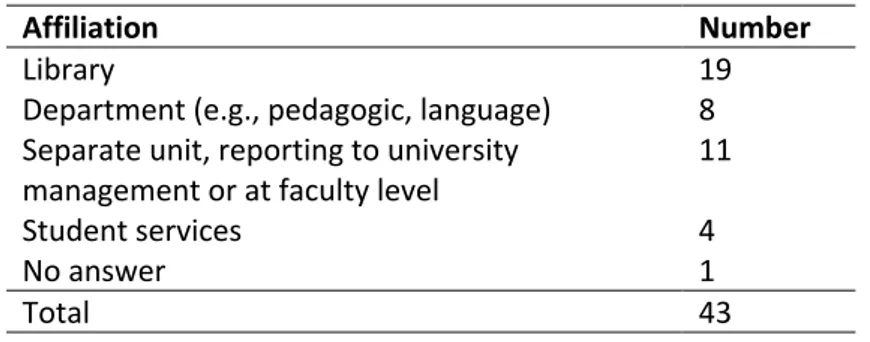

As expected (see Bjernhager & Grönvall Fransson, 2018), the reported institutional affiliation of the centres proved to be diverse (see Table 1).

Table 1 Affiliation

Affiliation Number

Library 19

Department (e.g., pedagogic, language) 8 Separate unit, reporting to university

management or at faculty level

11

Student services 4

No answer 1

Total 43

3.2 Awareness of university language policy

Karlsson (2017) states that in 2016, 21 of 47 higher education institutions had some form of written university language policy in place. Due to national language legislation, we can assume that in 2020 more institutions have a written language policy. The awareness of such a policy remains, however, low amongst university staff and students in Sweden.

In the survey, 29 respondents reported that their institutions had a language policy, five reported that their institution did not have a language policy, and the remainder selected ‘don’t know’. Of the 29 who responded positively, 19 suggested that this policy influenced their work, ten denied such an influence. The influences mentioned related especially to the use of Swedish and English in all areas of the

university (teaching, research, administration). This was described at an institutional level in which some saw the existence of the centre as a consequence of the language policy and its requirement to support students and staff in developing their academic Swedish and English. Others described it from a personal perspective, considering their regular use of both Swedish and English in their workplace. Some also

4

mentioned that the policy influenced the unit’s marketing in terms of providing information in both Swedish and English.

Those who denied an influence, suggested that the policy was too general to be applied, that it was not discussed at the centre and therefore did not have a direct impact, or that students had decided which language to use before they came to the centre.

3.3 Language use with colleagues and students

The focus on Swedish and English was also evident in replies to the questions on language use with colleagues and students. With colleagues, Swedish and English were the only reported languages. Responses to the questions about language use by and with students also focused mainly on Swedish and English. Besides these two languages, respondents referred to using some phrases in other mainly European languages (e.g. French, German, Latin, Norwegian and Spanish). The main reason for this use of languages other than the target language was to explain something or compare language systems (especially English and Swedish). Other languages were also used to build rapport. In the responses to the cases, additional reasons were given for using different languages (see esp. Section 3.4.2).

3.4 Strategies described for cases

The cases used in the survey were constructed in collaboration with learning developers at Stockholm University. The aim of including these cases was to provide concrete scenarios to respond to. The disadvantage of such scenarios is that they provide simplifications, as some of the respondents also observed in their responses. Certain aspects of the case descriptions beyond the multilingualism of the students might also have triggered specific responses, e.g. a focus on grammar teaching from the second Swedish-language case (see below). Taken together, however, the responses provide some insights into strategies that seem to be accepted within the community.

We coded the responses distinguishing broadly between consultation strategies and learning strategies (see Appendix II).

The cases for Swedish-language consultations where: 1. En flerspråkig student med en akademisk examen från ett annat land, på ett annat språk än svenska, kommer till dig för handledning. Hen vill ha hjälp med stavning, grammatik och ordval. Hen beskriver att skrivandet är en utmaning, att det tar lång tid att hitta de rätta formuleringarna och att hen vill lära sig att skriva korrekt akademisk svenska. Hen använder ordböcker, men tycker att det är svårt att hitta de rätta uttrycken i dem.

2. Inför handledningen skickar studenten du ska träffa in en text med grammatik och meningsbyggnad som inte

motsvarar skriftspråksnormen. Hen vill ha hjälp att klara en tenta som hen misslyckats med flera gånger. Handledningen börjar med att studenten förklarar att hen inte förstår vad som är fel i texten. Det visar sig också att studenten inte har kunskap om grammatiska termer eller annat metaspråk. The cases for English-language consultations where:

5

1. A student who uses English as an additional language comes to your one-to-one tutorial and wants help with ‘academic English’. The student explains that s/he is new to academic writing in English, that it takes a lot of time to find the right formulations, and that s/he is unsure if their text has been written using correct academic language. S/he would like you to check the text for them.

2. A masters student who uses English as an additional language comes to your one-to-one tutorial and requests help with the structure of a particular assignment. The student explains that s/he has not written this kind of text previously. S/he is unsure about what should have been included in different sections of the text and if the ideas in the text have been presented clearly.

3.4.1 Consultation strategies

The strategies coded as consultation strategies are those that centre on the actions of the learning developer as a teacher or on their approaches to consultation sessions or consultations in general. These included general strategies for teaching aspects of language and grammar, references to the use of different languages, modes or registers, and choosing to focus on global or text-level issues in the students’ texts. It also included references to motivating students and asking them about their backgrounds, referring the students to other courses or services, and recommending further

consultations. These strategies are presented in the order of their frequency in the survey responses. Teaching strategies were mentioned in 26 responses. Most of these were strategies for explaining grammar or mistakes in the student’s text and all were mentioned in response to the Swedish-language cases. As mentioned previously, this emphasis on teaching grammar for the Swedish cases is possibly the result of the way the Swedish-language cases were formulated. A number of responses suggested using everyday terms to explain grammar or avoiding grammatical terms completely. Other responses, however, explicitly proposed helping students to develop knowledge of grammatical metalanguage or metalanguage relating to features of academic texts. Not all of these strategies were described in detail. A focus on global (e.g. structure, content, audience) or text-level issues (e.g. grammar, word choice, style), or a strategy of moving from global to text-level issues, was also identified in many of the responses. We note, however, that the choice of focus might again have been made in response to the way the cases were formulated. We also note that the distinction between the categories global and text-level was not always clear, for example when respondents referenced working with topic sentences or transition signals, which might relate to both global and text-level concerns. We identified 19

examples of a text-level focus, mostly in response to the Swedish-language cases, and 15 examples of a global focus, mostly in response to the English-language cases. In five responses, the respondents proposed starting with a global focus and moving to text-level issues afterwards.

A number of respondents suggested that the student seek further support and referred the student to courses or support services, or recommended further consultations. Nine respondents suggested that the student enrol in language or academic writing courses, and one respondent suggested that students with ongoing difficulties should speak to a study and careers counsellor. Nine respondents also

suggested that the student return for further consultations, including through booked appointments and visits to drop-in services.

6

Asking about the student’s language, study or writing background was mentioned by a number of respondents as a way of starting a consultation. Seven respondents referred to discussions about students’ backgrounds, including their previous study, previous experience of academic writing, their other languages, and their strategies for reading, writing and editing texts. Eight respondents

additionally suggested trying to motivate students by, for example, listening to them, encouraging them to be patient, explaining that the development of language or writing skills takes time, and encouraging them not to give up.

There were only five explicit references to the use of other languages as a teaching or consultation strategy. Of these, three related to the contrastive use of another language to better understand language structure or academic language in Swedish. One respondent suggested investigating the possibility of submitting work in English rather than Swedish, if English was the stronger language. The changing of modes or register was also suggested, however, as a strategy for teaching or raising awareness through contrasts. Five responses suggested reading texts aloud in order to help students perceive mistakes. Five responses also suggested discussing the differences between different registers, mostly with reference to the difference between spoken and written language, but also more generally in relation to academic style.

3.4.2 Learning strategies

The strategies coded as learning strategies were the strategies that were recommended to the students, or for which the students had responsibility. These included recommendations to read extensively or use materials in other modes to gain exposure to the target language, and recommendations to make use of human resources, such as peers, friends and supervisors. Learning strategies also included making use of different languages, registers or modes at different stages in the writing process, and discussion of the task and the reader. Also included in this category are recommendations for students to make use of digital or physical tools or resources.

The most commonly recommended learning strategy (33 examples) was further reading in the target language. Some respondents simply recommended reading widely, while others recommended reading specific types of literature. The majority recommended reading academic and scientific texts, texts in the student’s field of study and course literature, while a smaller number of respondents recommended reading other kinds of texts, such as popular science articles, newspapers and fiction. One of the most commonly given reasons for further reading was to develop knowledge of vocabulary by paying

attention to words, terms and expressions in the reading materials. Other reasons included exposure to model grammar, structure and style. A number of respondents recommended gaining further exposure to the target language by accessing different modes, for example by listening to radio or watching television or films.

While there were again few explicit references to the use of different languages, many more respondents suggested changes in mode or register as a learning strategy. Three respondents

mentioned the use of different languages during the writing process, two of them suggesting the use of a first or stronger language for writing drafts or brainstorming, and one suggesting the mixing of languages in drafts. 10 respondents mentioned a strategy of changing register, which included

suggesting that students explain their ideas verbally, express themselves in their own words, write using simpler language, or learn the difference between spoken and written language. 10 respondents

additionally mentioned a strategy of changing modes by reading texts aloud, or having texts read by text-to-speech software. In the majority of these responses, the suggestion was for students to hear their own texts so they could more easily identify language errors. All of the references to the use of

7

different languages, modes or registers as learning strategies were made in response to the Swedish-language cases.

Eleven respondents suggested drawing on classmates, friends or lecturers for help with language and with understanding writing tasks. In the majority of these responses the suggestion was to have classmates, or friends or family, read the text in order to receive feedback or discuss language issues in the text. In two cases the respondent suggested that this take place through study or writing groups. Contact with lecturers or supervisors was suggested by three respondents, in order to ask questions about assignments or recurring language issues. Two respondents suggested making contact with native speakers or joining language cafés as a strategy for developing competence in the target language more generally.

Further strategies identified in the responses were discussion of the writing task and consideration of the reader. 10 respondents suggested discussing the task with the student, with the emphasis generally being on the student explaining their understanding of the task, their approach to the task or their interpretation of task requirements. Seven respondents suggested discussing the reader of the text. Here, the emphasis was mostly on discussing textual features, such as signposting, structure and topic sentences, that might help ‘guide’ the reader through the text. One respondent suggested a discussion of the teacher/lecturer’s expectations. Both discussion of tasks and of the reader were suggested more frequently in response to the English-language cases. It is possible that references to the task, however, were made in response to the formulation of the second English-language case.

The use of different digital and physical tools and resources was a common recommendation and was identified in 43 responses. The most frequently recommended digital tools were dictionary apps or websites such as svenska.se (mentioned in 12 responses). Other frequently recommended digital tools and resources included text-to-speech applications such as TorTalk (9 responses), spelling or grammar checkers such as Stava Rex (8 responses), and online phrasebanks such as Karolinska Institutet’s Frasbank (8 responses). Other references to digital tools and resources included references to corpus websites, grammar websites and online resources hosted by the respondent’s academic skills centre. There were fewer references to physical resources (12 responses) and these included recommendations to consult grammar books (5 responses) or use other textual resources such as writing guides,

dictionaries, and handouts.

3.5. Internationalization and widening participation

The vast majority of respondents (37 of 43) agreed that universities’ aims of internationalization and widening participation (breddad rekrytering) influence their daily work. Respondents explained their answers by pointing to the increased heterogeneity of staff and students’ educational and language backgrounds. Some also suggested that these groups have diverse cultural expectations of education. One respondent mentioned that these aims and their implications are regularly part of discussions at staff meetings to develop the centre’s work.

Widening participation is considered to be one of the reasons for establishing academic skills centres in the first place. This means that learning developers meet students who might not have been sufficiently socialized into academic ways of working, or who have special needs, such as dyslexia. One respondent summarized the implications of this heterogeneity for their centre’s work as follows:

Framför allt genomsyras vår verksamhet av en ambition att synliggöra de ofta osynliga krav och förväntningar som ställs på studenter rörande till exempel akademiskt skrivande och som kan vara extra svåra att greppa om man inte är insocialiserad i den akademiska miljön.

8

According to this response, learning developers need to make the tacit knowledge of academic work explicit so that the students can understand what is expected from them.

In terms of internationalization, respondents mentioned that there are more students and staff who need to use academic English. On a personal level, respondents mentioned that they use English with colleagues and students and take part in international exchange programmes.

Five respondents suggested that the aims of internationalization and widening participation do not influence their work. Their explanations suggest that these aims do not have any practical implications for their work.

4. Questions arising from the survey

The survey provides a range of perspectives on the work of learning developers at multilingual Swedish universities. The results underline the spread of using both Swedish and English in education and administration across universities. Researchers, lecturers, learning developers and students need to be able to use either or both of these languages in various genres, both written and spoken. The two languages are not only used in parallel, i.e. for separate tasks, but also in complementary ways. For instance, some Swedish is used to talk about writing in English and vice versa. The use of other languages is also mentioned and in the case responses we find a few instances where the use of other languages or registers is suggested as a deliberate strategy in the writing process (e.g. for

conceptualization, note taking, drafting). The responses suggest that using a different language or register facilitates the understanding of information and development of ideas.

The responses to the cases demonstrate that learning developers use a broad range of tools and strategies. As mentioned above, these responses need to be seen in the context of the hypothetical scenarios. Nevertheless, the recurrence and frequency of the strategies indicate that there is a large pool of shared pedagogical knowledge, which in turn points to the ongoing professionalisation of the sector in Sweden.

There are a number of questions arising from the survey, for instance:

1. The last decades have seen an increase in student numbers and study programmes at universities and university colleges in Sweden. This development entails an increase in the diversity of students’ educational and language backgrounds. Nodén (2019, p. 12) observes:

I propositionen Den öppna högskolan (Prop. 2001/02:15) slås fast att mångfald har en positiv inverkan på utbildningarnas kvalitet men också att en heterogen studentgrupp kräver mer av lärosätet. Dessa krav yttrar sig som behov av anpassning av utbildningarna. Inte i form av sänkta krav, utan i undervisning som hjälper studenterna att uppfylla utbildningarnas krav.

If this is the case, what does this mean for the work of learning developers and the further professionalisation of the sector?

2. How can limited resources best be used to support heterogeneous groups of students? Or how can institutions be convinced of the need for more resources and how should such resources be used? 3. Higher education policy and universities themselves often commend diversity and multilingualism.

In policy documents, multilingualism is often described as a resource. What does this mean in practice for academic skills centres?

9

In the responses to the cases, there were only few explicit references to using different languages in the consultations. Is this a general tendency and if so, is there a potential to develop practice? What are possibilities and obstacles?

The use of different registers, i.e. letting a student explain what they mean or understand in more colloquial terms before they write it in a more academic genre, seems to indicate the usefulness of using different language varieties for meaning making. Can this practice provide insights for multilingual pedagogical approaches?

4. The survey points to the variety of linguistic competences of the learning developers. In what ways can these linguistic resources be used and developed to support academic writing in multilingual settings?

5. The responses suggest that there might be a preference for slightly different strategies and teaching models in Swedish-language and English-language consultations. This might of course be due to the formulation of the specific cases. If there are different orientations beyond these cases, however, what are the reasons for these (different traditions, different professional backgrounds of the learning developers, the different academic levels of the students (with English-language consultation being often connected to advanced-level students))? What are the implications for the continuous professional development of learning developers? Is there a sharing of knowledge and competences between learning developers working in Swedish and English, or is there potential for further sharing?

The survey did not gather information about the professional background of the learning developers. It might be worth considering this factor to understand the use or preference of different strategies. It might also open up possibilities for the sharing of knowledge and competences.

References

Bjernhager, L. & Grönvall Fransson, C. (2018). Studieverkstäder vid svenska lärosäten 2017: En kartläggning. Available online: https://padlet-uploads.storage.googleapis.com/98627135/

e0ddad45c017d83773b5793141a0651f/Studieverkst_der_vid_svenska_l_ros_ten__En_kartl_ggning__Bj ernhager___Gr_nvall_2018__Slutpublicering.pdf

Gregersen, F., Josephson, O., Kristoffersen, G., Östman, J.-O., Londen, M., and Holmen, A. et al. (2018). More parallel, please! Best practice of parallel language use at Nordic Universities: 11 recommendations. Copenhagen: Nordic Council of Ministers.

Karlsson, S. (2017). Språkpolitik vid svenska universitet och högskolor. Rapporter från Språkrådet 8. Språkrådet. Available online: https://www.isof.se/download/18.48d75a5715c7c21d71d9505/

1529494206314/Spr%C3%A5kpolitik%20vid%20svenska%20universitet%20och%20h%C3%B6gskolor.pdf Kuteeva, M., Kaufhold, K., & Hynninen, N. (eds.) (2020). Language perceptions and practices in

multilingual universities. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Lennartson-Hokkanen, I. (2016). Organisation, attityder, lärandepotential: Ett skrivpedagogiskt

samarbete mellan en akademisk utbildning och en språkverkstad. Doctoral Dissertation. Department of Swedish Language and Multilingualism, Stockholm University.

10

Swedish Council for Higher Education. (2016). Can excellence be achieved in homogeneous student groups? Available online: https://www.uhr.se/globalassets/_uhr.se/publikationer/2016/uhr-can-excellence-be-achieved-in-homogeneous-student-groups.pdf

11

Appendix I

Språkverkstäder och flerspråkighet i Sverige

Denna enkät syftar till att samla in perspektiv på universitetet som en flerspråkig miljö från dig

som arbetar på en språkverkstad. Enkäten görs inom ramen för en undersökning av Studie- och

språkverkstaden och Engelska institutionen vid Stockholms universitet.

Ditt deltagande är värdefullt för oss och att besvara enkäten tar omkring femton minuter. Med

hjälp av den information vi samlar in hoppas vi kunna bidra till kunskapen om

språkverkstäder.

Du är anonym när du besvarar enkäten och inga personuppgifter som faller under

dataskyddslagen GDPR registreras (se Datainspektionen:

https://www.datainspektionen.se/lagar--regler/dataskyddsforordningen). Lämna inga

personuppgifter eller uppgifter om din institution i fritextsvaren.

Vi hoppas kunna analysera den data som samlas in och använda denna i vetenskapliga

publikationer och presentationer. Genom att besvara enkäten godkänner du att vi använder

informationen för dessa syften.

Om du önskar få ta del av resultatet från studien, lämna gärna din mejladress genom länken i

slutet av enkäten. Din mejladress kommer inte att kopplas samman med dina svar i enkäten.

Kontakta os gärna för mer information:

Egil Yencken MA, MTESOL

Studie- och språkverkstaden

Stockholms universitet

daniel.yencken@su.se

Kathrin Kaufhold, PhD

Engelska institutionen

Stockholms universitet

kathrin.kaufhold@english.su.se

Bakgrundsinformation

1. Vilken del av universitetet tillhör din språkverkstad? □ Biblioteket

□ Studentavdelningen □ Other:

12

2. Finns det en språkpolicy på universitetet/högskolan där du arbetar? □ Ja

□ Nej □ Vet ej

3. Påverkar den ditt arbete? □ Ja

□ Nej

4. Om ja, på vilket sätt?

5. Om nej, varför inte?

Samarbeten

6. Hur samarbetar du med andra undervisande personal från olika institutioner? Bocka för alla alternativ som stämmer överens på dig.

□ Inte alls

□ Genom personlig kontakt

□ Genom att ge skräddarsydda föreläsningar/workshoppar på (andra) institutioner □ Genom att undervisa på specifika kurser

□ Genom att undervisa tillsammans □ Sambedömning

□ Other

7. Vilka språk använder du tillsammans med annan undervisande personal?

8. Vilka språk använder du då du undervisar studenterna i dessa samarbeten?

Språkanvändning

9. Vilket/vilka språk använder du på regelbunden basis tillsammans med studenter och kollegor?

13

10. Använder du något annat språk på regelbunden basis utanför arbetet?

□ Ja □ Nej

11. Om ja, vilket/vilka?

Studentstöd

12. Vilket/vilka språk använder studenterna som kommer till din språkverkstad för handledning och andra aktiviteter?

13. Ger du stöd i akademiskt skrivande på svenska?

□ Ja □ Nej

Handledning på svenska

14. Använder du någonsin andra språk än svenska i handledning med studenter?

□ Ja □ Nej

15. Om ja, vilket/vilka språk använder du? Skriv ner samtliga språk du använder, även om det bara är ett uttryck på ett annat språk.

16. I vilket syfte använder du detta/dessa språk?

Case 1

Läs igenom caset nedan och svara sedan det som först kommer för dig. Ge så många detaljer som möjligt.

En flerspråkig student med en akademisk examen från ett annat land, på ett annat språk än svenska, kommer till dig för handledning. Hen vill ha hjälp med stavning, grammatik och ordval. Hen beskriver att skrivandet är en utmaning, att det tar lång tid att hitta de rätta formuleringarna och att hen vill lära sig att skriva korrekt akademisk svenska. Hen använder ordböcker, men tycker att det är svårt att hitta de rätta uttrycken i dem.

17. Vad skulle du ge för råd till studenten?

14

Läs igenom caset nedan och svara sedan det som först kommer för dig. Ge så många detaljer som möjligt.

Inför handledningen skickar studenten du ska träffa in en text med grammatik och meningsbyggnad som inte motsvarar skriftspråksnormen. Hen vill ha hjälp att klara en tenta som hen misslyckats med flera gånger. Handledningen börjar med att studenten förklarar att hen inte förstår vad som är fel i texten. Det visar sig också att studenten inte har kunskap om grammatiska termer eller annat metaspråk.

18. Hur skulle du fortsätta handledningen?

19. Ger du också stöd i akademiskt skrivande på engelska?

□ Ja □ Nej

20. Använder du någonsin andra språk än engelska i handledning med studenter?

□ Ja □ Nej

21. Om ja, vilket/vilka språk använder du? Skriv ner samtliga språk du använder, även om det bara är ett uttryck på ett annat språk.

22. I vilket syfte använder du detta/dessa språk? Case 1

Consider the following cases and write down your immediate response. Please give as much detail as possible.

A student who uses English as an additional language comes to your one-to-one tutorial and wants help with 'academic English'. The student explains that s/he is new to academic writing in English, that it takes a lot of time to find the right formulations, and that s/he is unsure if their text has been written using correct academic language. S/he would like you to check the text for them.

23. What would your advice be to the student? Responses can be given in Swedish or English. Case 2

15

Consider the following cases and write down your immediate response. Please give as much detail as possible.

A masters student who uses English as an additional language comes to your one-to-one tutorial and requests help with the structure of a particular assignment. The student explains that s/he has not written this kind of text previously. S/he is unsure about what should have been included in different sections of the text and if the ideas in the text have been presented clearly.

24. What would your advice be to the student? Responses can be given in Swedish or English.

Internationalisering, breddad rekrytering och flerspråkighet

25. Universiteten strävar mot både internationalisering och breddad rekrytering. Påverkar detta ditt dagliga arbete?

□ Ja □ Nej

26. Om ja, på vilket sätt? 27. Om nej, varför inte?

Demografisk information

28. Genus □ Man

□ Kvinna □ Annat

□ Vill inte uppge

29. Åldersgrupp □ 18-30

□ 31-40 □ 41-50 □ 51-60

16 □ >60

17

Appendix II

Coding scheme

Category Code Explanation Example

Consultation

strategy (CS) Strategy for the consultation session or for consultations in general, including teaching strategies global to local Strategy to focus on global issues first and local issues

afterwards “Fokusera först på det övergripande innehållet och strukturen, först därefter mer lokala nivåer i texten.” text level Focus on text level, e.g. word choice, grammar,

spelling “Jag skulle markera olika typer av grammatiska fel som förekommer i studentens text och noga gå igenom vad som är rätt.“

global level Talk about global text issues, e.g. content, structure,

paragraph, cohesion, argument “global-level feedback (e.g., overall narrative, section/paragraph structure, cohesion, signposting, etc.)” multilingual Encourage student to compare (e.g. grammatical

forms) between TL and other languages, advice to change language for entire text (often English) or in parts

“Jag skulle först fråga studenten om hen talar ett annat språk bättre (och kontrollera om hen på detta språk kan se vad som är rätt och fel). Om studenten kan detta jämför jag/förklarar motsvarande i svenskan.”

“Beroende på program/kurs kan jag höra om det kan vara möjligt för hen att skriva sitt arbete på engelska, om engelskan är bättre”

18 register Use comparison of (spoken/written) genres to

elucidate academic writing norms/style “Jag skulle prata lite allmänt om skillnaden mellan skriftspråk och talspråk, och den akademiska stilen.” mode Consultant changing mode, for example in order to

help student understand text level or grammatical issues (in contrast to LS mode)

“Jag skulle också läsa högt för studenten för att se om hen hörde problemen.“

motivation Talk about motivating student “I would listen and bekräfta the student”

background Ask about learning, language background “Jag skulle fråga om studentens bakgrund, hur tidigare studier sett ut och om hen har ett annat förstaspråk än svenska som hen behärskar bättre.”

further

consultation Suggest another consultation, often as follow-up “Vi skulle boka in en ny tid då följer upp”

referral Refer student to other service or course “eventuellt kan en termin på förberedande akademisk kurs hjälpa till”

teaching Strategies of consultant as a teacher, e.g. explanations

of abstract dimensions of language/writing/grammar “Jag skulle förklara fel på ett så enkelt och "ogrammatiskt" sätt som möjligt.”

Learning

strategy (LS) Learning strategy recommended to the student, student has responsibility multilingual Description of using different languages in a text or at

19

svenska. Om det finns en svårighet att ens finna innehållet i det hen vill säga, kan man ev. råda till att tänka och

tankeskriva på sitt bästa språk innan man tar itu med de svenska formuleringarna”

register Strategy to use own words, written and/or spoken to

understand content or ‘get at’ student’s knowledge “Besvara frågeställningen genom att sammanfatta det som är relevant i källorna med egna ord. Formulera först muntligt högt för dig själv om det underlättar.”

mode Use different modes at same time or change modes as a LS (in contrast to CS), often reading out loud of own or others texts

“Om det är svårt att hitta rätt när du skriver, prova att säga det i stället. Det är ofta lättare att hitta rätt när du talar”

audience Suggestion to think about the ‘reader’ “I would also talk about different strategies for guiding the reader through the text and make the structure clear to the reader”

human

resources Strategy to make use of contact with teachers/peers for learning, also of the material available through these interactions

“Låta kompis/student läsa och ge feedback på just det som studenten vill och behöver.”

read Strategies to learn about text structure and vocab through reading or through other modes, immersion idea

“jag råda hen att läsa något sådant och annars svensk vetenskaplig text i ämnet”

task Talk about understanding the task, e.g. have the student explain the task, highlight keywords. Includes discussion of marking criteria.

“Jag skulle vilja läsa uppgiftsbeskrivningen ihop med

studenten och be hen förklara hur hen uppfattat vad hen ska göra”

20

tools Digital or physical tools that were suggested “Använd tillförlitliga ordböcker som SO på svenska.se” “Ta hjälp av ordbehandlingsprogrammetall och ev tilläggsprogram StavaRex.”