Understanding employees’ perceptions towards

advancing the Sustainable Development Goals

(SDGs) in an organizational context

A study of Small and Medium Enterprise (SME) employees in Cape Town,

South Africa

Chinomnso Onwunta

Berend Casper

Main field of study – Leadership and Organization

Degree of Master of Arts (60 credits) with a Major in Leadership and Organization

Master Thesis with a focus on Leadership and Organization for Sustainability (OL646E), 15 credits Spring 2020

Abstract

Since the introduction of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015, by the United Nations, several academic works have mainly sought to understand how larger organizations and governmental agencies are working towards advancing these goals. However, there is limited research on how Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) are working towards these goals, especially in developing countries such as South Africa. The organizational incorporation of the SDGs is seen as part of the successful achievement of the goals. Given that employees are organizations’ primary internal stakeholders, this study seeks to understand the perceptions of SME employees towards the advancement of these goals - within an organizational setting. Using a qualitative inductive approach, the study utilizes semi-structured interviews as the primary source of data collection. The findings suggest that: (a) there is a multiplicity in the manner in which employees acquire their knowledge of the SDGs (b) even though no explicit information exists about the SDGs within organizations, SMEs are inherently working towards the SDGs but the efforts are insufficient (c) implementing the SDGs is filled with diversity of challenges (d) there is no clear consensus on which actor is responsible for driving SDG implementation in organizations. Without the SDGs being an organizational priority, implementation will always be secondary. There are several theoretical and practical implications of the study, which helps gain understanding of what is required for SMEs to contribute towards advancing the SDG. The study limitations are also presented, leading to recommendations for future studies.

Keywords: Employees, Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), Organizations, Small and Medium

Enterprises (SMEs), and Sustainability

Abbreviations:

BRICS – Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa

BRIICS – Brazil, Russia, India, Indonesia, China, South Africa CCB – Compulsory Citizenship Behaviour

CSR – Corporate Social Responsibility LMX – Leader-Member Exchange

OCB – Organizational Citizenship Behavior SA – South Africa

SCSR – Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility SDGs – Sustainable Development Goals

SME – Small and Medium Enterprises UN – United Nations

Acknowledgement

We would like to extend our gratitude to Dr. Hope Witmer, our supervisor, for the guidance and assistance throughout the process of writing the thesis. We would also like to thank the respondents of this study, without whom the study would not have been possible. Thank you to our family and friends for the continuous reassurance and affirmation. Finally, we would like to acknowledge Malmö University SALSU Masters class of 2019/2020 for the support and valuable feedback sessions. And to all others who played a part in one way or the other, your contribution is not forgotten – we say a big Thank You.

Table of Contents

1.INTRODUCTION ... 1

1.1

BACKGROUND ... 1

1.2

RESEARCH PROBLEM ... 3

1.3

PURPOSE ... 3

1.4

RESEARCH QUESTIONS ... 3

1.5

DEFINING THE SCOPE ... 3

1.6

OUTLINE ... 4

2.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK ... 5

2.1

ORGANIZATIONAL PERSPECTIVE ... 5

2.1.1

Stakeholder theory and business sustainability ... 5

2.1.2

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) ... 6

2.2

LEADERSHIP THEORIES ... 7

2.2.1

Systems thinking in complexity and sustainability leadership ... 7

2.2.2

Leader Member Exchange (LMX) and sustainability ... 8

2.3

EMPLOYEE PERSPECTIVE ... 8

2.3.1

Organizational citizenship behaviour (OCB) ... 8

3.

PREVIOUS RESEARCH ... 11

3.1

ORGANIZATIONS AND THE SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS (SDGS) ... 11

3.2

CHALLENGES FOR SUSTAINABILITY IN ORGANIZATIONS ... 13

3.3

SMALL AND MEDIUM ENTERPRISES (SMES) ... 14

3.3.1

The characteristics of SMEs ... 14

3.3.2

SME contribution to economies ... 15

3.3.3

SME-specific challenges ... 15

3.3.4

SMEs in Developing vs. Developed countries ... 16

3.4

SOUTH AFRICAN SMES AND THE SDGS ... 17

4.

METHODOLOGY ... 19

4.1

ONTOLOGY AND EPISTEMOLOGY ... 19

4.2

RESEARCH APPROACH AND METHODS ... 19

4.2.1

Data collection methods ... 19

4.2.2

Sampling ... 20

4.2.3

Data analysis methods ... 20

4.3

RELIABILITY AND VALIDITY ... 21

4.4

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS ... 21

4.5

LIMITATIONS ... 22

5.

INTRODUCTION OF INTERVIEWEES/RESPONDENTS ... 23

6.

STUDY FINDINGS AND ANALYSIS ... 24

6.1

MULTIPLICITY OF KNOWLEDGE ... 24

6.2

PERCEIVED SDG IMPLEMENTATION ... 25

6.3

DIVERSITY OF CHALLENGES AND FACTORS ... 28

6.3.1

Awareness, knowledge and education ... 28

6.3.2

Organizational priority and management ... 29

6.3.3

Incentives, reporting and enforcement ... 31

6.4

OWNERSHIP OF THE GOALS ... 32

7.

DISCUSSION ... 35

7.1

ORGANIZATIONS AND SOCIETAL MANDATE ... 35

7.2

FINGER POINTING ... 37

7.3

ORGANIZATIONAL ALLEGIANCE OVER GLOBAL CITIZENSHIP ... 38

8.

CONCLUSION AND IMPLICATIONS ... 40

8.1

LIMITATIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH ... 41

REFERENCES ... I

APPENDIX A – SME CLASSIFICATION IN SOUTH AFRICA ... IX

APPENDIX B – INTERVIEW PROTOCOL ... X

APPENDIX C – RESPONDENT #5 TRANSCRIPTION ... XI

APPENDIX D – RESPONDENT #8 TRANSCRIPTION ... XVIII

List of figures Figure 3-1: Graphic of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): Retrieved from United Nations Website (United Nations, 2015) ... 11

List of tables Table 3-1: Mapping the UN Global Compact against the SDGs - Adapted from (Malan, 2016) .. 12

Table 5-1: Details of respondents interviewed for the study ... 23

1. Introduction

Following the introduction of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by the United Nations (United Nations, 2015), there is limited knowledge of the extent to which businesses, especially Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs), understand and move towards achieving these goals (Rubio-Mozos, García-Muiña & Fuentes-Moraleda, 2019). The organizational implementation of the SDGs is a complex challenge, which requires a multi-stakeholder effort to be successful (Fourie, 2018). SMEs constitute a dominant majority of firms both in the developed and developing world (Asah, Fatoki & Rungani, 2015); nevertheless, the limited research on the SDGs within firms mainly focuses on bigger organizations and multinationals or directed towards governmental institutions. There is scant research on exactly how SMEs contribute to the SDGs. Moreover, the limited literature on SMEs available denotes a higher level of SDG application within SMEs in developed countries; yet minimal literature is available when it comes to developing countries, especially in Africa. Asah et al. (2015) state that in South Africa, SMEs contribute in a significant way to poverty alleviation, employment, innovation and technological advancement (all aspects of the SDGs); even though there is a high failure rate of SMEs in the country, constituting between 70 – 80%. This statistic is rather alarming because these organizations play a critical role in the national economic growth and the advancement of the SDGs – many of which are directed towards tackling social issues. Given that SME employees as primary internal stakeholders (Fassin, 2009) are fundamental for organizational success (Baker, 2007; Uhl-Bien et al., 2014), coupled with the vital role SMEs play in various national economies - including South Africa (Fatoki, 2018a) – this research seeks to gain insights on employee perceptions towards SDG advancement within SMEs.

1.1 Background

In developing economies, SMEs contribute in different ways to economic growth and development, but also face numerous social, economic, and environmental challenges. A major challenge SMEs usually face in the developing context is that of financial strain which affects their ability to focus on anything else beyond economic survival (Abisuga-Oyekunle, Patra & Muchie, 2019). Thus, SMEs regard the SDGs as an additional factor that impact on resource usage. Regardless, these organizations still provide a large amount of goods and services and have many employees who are tasked with doing the day-to-day activities necessary for economic survival. Effective development of SMEs contribute to a creation of national economic growth thereby enhancing the communities in which they operate (Auemsuvarn, 2019). Numerous researches have indicated the role of government in facilitating the development of SMEs and the implementation of sustainable development, and the understanding of the SDGs have primarily been hinged on governmental policies and how they impact and affect the SMEs’ contribution to the SDGs (Abisuga-Oyekunle et al., 2019). Nonetheless, the onus is not only up to government, and a top-down approach should not necessarily be the approach for achieving the SDGs (Ali, Hussain, Zhang, Nurunnabi, & Li, 2018). Cant and Wiid (2013) note that SMEs need to be aware of their environment, and any changes that occur, which have an effect on their operations. The introduction of the SDGs can be said to have a significant impact on SMEs as the goals are considered additional factors necessary to take into consideration during operation of the organization. The limited literature on understanding of the SDGs within the SMEs in developing contexts, such as South Africa, suggests that it is either not a priority (meaning that there are other pressing issues to worry about) or that the message does not resonate well within such contexts (Ali et al., 2018).

Studies suggest that society and diverse stakeholders are increasingly putting pressure on organizations to consider their climate impact, and are willing to patronize organizations that adopt sustainable practices (Darus, Mohd & Yusoff, 2019). So then, it is of great importance that SMEs find new ways to add value to society, implement and operationalize sustainable development (Masocha & Fatoki, 2018a). According to Masocha and Fatoki, (2018a), there is an increasing call for research into how organizations, including SMEs, can incorporate a uniform

sustainable development mandate. One way to adopt this mandate is using a standard guiding mechanism or framework, which is this case, is the SDGs. The SDGs cover the three recognized pillars of sustainable development (social, economic and environmental) and these pillars constitute the fundamental areas in which an organization can affect its operating environment (Masocha & Fatoki, 2018a). The role of leadership is important to the extent of which these pillars are balanced within the organization (Bayle-Cordier, Mirvis & Moingeon, 2012); yet SMEs continue to report a lack of knowledge within the management level (OECD, 2019). Consequently, it can be argued that the responsibility is not solely that of management to increase employee level of understanding of the SDGs, therefore that beckons the question as to how employees perceive these goals and what role they have to play in fulfilling these goals within their organization?

In Sub-Saharan Africa, SMEs account for 95% of companies (Abisuga-Oyekunle et al., 2019). In South Africa, SMEs contribute between 35% - 45% of the gross domestic product (GDP) and account for between 50% - 60% of the employment (Nieuwenhuizen, 2019; Fatoki, 2018a). Therefore, the importance of this sector cannot be overstated in such a context. South Africa is one of the biggest economies in Africa (Kasekende, Mlambo, Murinde & Zhao, 2009), so, the country’s successful achievement of the SDGs could provide an indication that the message trickles down to different sized economies, regardless of the level of development. Even though there are many challenges faced by SMEs in South Africa, these businesses also have to take into consideration the SDGs if the SDGs are to be achieved in South Africa (Malan, 2016; Masocha & Fatoki, 2018b). After five years of the initiation of the SDGs, there is a measured expectation from the authors of this study that the organizations being studied have heard of SDGs. Based on literature, several organizations might not be actively working towards these goals (Darus et al., 2019) since there is a level of ignorance regarding the full value added to the organization, and a view that implementation could potentially consume too many resources (Masocha & Fatoki, 2018b) .

Furthermore, organizations are perhaps willing to work towards these goals but are more focused on the economic viability of the organization (Masocha & Fatoki, 2018b). Given that SMEs employ a large percentage of South Africa’s workforce (Fatoki, 2018a), with Cape Town being the 2nd biggest economic hub, it is important for members of organizations (employees) who carry out the work to understand the SDGs for achievement to be a reality. South Africa is part of the BRIICS (Brazil, Russian Federation, India, Indonesia, People’s Republic of China, South Africa), which is a group of emerging economies that share a similar growth and economic interests (OECD, 2019). The development of SMEs in these parts of the world is vital to promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all, noted as SDG-8 in the UN SDGs (United Nations, 2015). This is one of the SDGs that relates directly to for-profit SMEs, but a lot of SMEs keep failing for several reasons (Bushe, 2019), resulting in employees losing their jobs.

This failure of SMEs draws attention to the overall sustainability of SMEs. The puzzle is whether SMEs cater for the wrong needs, by mainly focusing on the financial and economic aspect of sustainability, therefore leading to failure. On the other hand, if these entities mainly focus on the environment and the social aspect, there might not be enough support from the government and other financial agencies to finance them. This in turn might mean that these organizations are viewed as a social innovation/entrepreneurship, which does not have much traction or establishment in the context. Going through multiple websites of businesses in the Cape Town region, one does not find any information pertaining to the SDGs on organization’s websites. A search through several organizations’ websites within the region shows limited to zero information about the SDGs. None of the organizations of the employees/respondents had any information about any SDGs being targeted. Four of the organizations had a section on how they addressed some element of green and social issues. That begs the question as to whether these SDGs are fully understood and if they resonate within the context of South Africa, or if

societal issues to be addressed in South Africa, more knowledge is required to understand the furtherance of these goals within SMEs and what possible role employees play in achieving them, if any.

1.2 Research problem

Research indicates that SMEs play a vital role in world economies, contributing vastly to employment and other economic growth. The international, unanimous agreement on the adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) was a way to tackle the pressing global sustainability issues (Malan, 2016). Studies also suggest that SMEs have a role to play in the achievement of the SDGs. Nevertheless, despite the importance and significance in SMEs advancing the SDGs, limited information exists on how employees of these organizations perceive and understand the SDGs and its applicability to their organizations. In addition, there is limited knowledge on the perceived role that employees play in the advancement of these goals within organizations.

1.3 Purpose

Since literature suggests that SMEs have a major role to play in the advancement of the SDGs, and the employees are important resource for organizational success, this research thus seeks to understand how members of these organizations perceive these goals. The method used to gain insights is by semi-structured interviews with respondents in Cape Town area. By conducting this research, the goal is to add to the existing body of literature related to the understanding of the SDGs in an organizational context, with a focus on SME employees. It also looks to explore the under-researched gap of the role of employees in advancing the SDGs. This is achieved by answering the research questions stipulated in the next section.

1.4 Research questions

Ø How do Cape Town SME employees perceive their organizations’ contribution towards advancing the SDGs?

• What are employees’ perceived challenges to advancing the SDGs within SMEs? • How do employees perceive their organizational role in advancing the SDGs?

1.5 Defining the scope

The study was conducted with SME employees in the Cape Town region. The criteria for SMEs in European Union (EU) are organisations with less than 250 employees and annual turnover less than 50million euros (European Commission, 2003). In South Africa, SMEs are classified having less than 250 employees with varying annual revenues based on their respective industry (see Appendix A) (Asah et al., 2015). For the purpose of the research, only firms with less than 250 personnel were considered regardless of the revenue of the organization, due to difficulty in obtaining financial records, deemed confidential. Employees who work for firms with larger than 250 employees were not considered for the study, as it is not part of the scope of the study as numerous studies have been conducted on larger firms (Masocha & Fatoki, 2018b). This is because larger organizations have formalised processes in dealing with development and human resource matters (Stoffers et al., 2019). There is empirical evidence that leadership heavily influences the success and failures of organizations in tackling wicked problems (Stoffers et al., 2019; Newman-Storen, 2014; Schilling, 2009). Therefore, one employee who assumed a leadership role was also considered for this study to get a diversity of view.

1.6 Outline

The chapter outline of the research is as follows:

• Chapter 1: Introduction – This chapter gave an overview of the central research problem. A brief background introduces the context of the study. It also highlighted the importance and significance of conducting the research. The purpose as well as the research questions was stipulated in this chapter.

• Chapter 2: Theoretical framework – provides the main theories of concepts applied to this study, which are important to understand the analysis and the theoretical application of the study.

• Chapter 3: Previous research – This chapter deals with previous research in relation to the key concepts of this study detailing the integration of theory in relation to the context of sustainable development.

• Chapter 4: Methodology – specifies the research process (data collection and methods of collection) in a thorough and detailed manner, acknowledging the potential challenges, limitations and considerations for the process.

• Chapter 5: Introduction of study respondents – This chapter presents information on the respondents interviewed for the study. The responses of these interviewees are the primary source of data and contribute substantially to the data collection required for analysis.

• Chapter 6: Study Findings and analysis – In this chapter meaning is extracted from the collected data, putting them into themes and workable concepts to provide a clear, coherent and insightful findings. These findings are supplemented by the secondary source of data, obtained through literature.

• Chapter 7: Discussion – The findings from the research are presented in this chapter, providing an analysis of what is discovered in relation to the research questions.

• Chapter 8: Conclusion - encompasses a brief summary of the study. Implications, limitations and recommendations are provided for future studies.

2. Theoretical framework

This chapter details theories and concepts that are vital to the research, which help to gain better understanding of the research.

2.1 Organizational perspective

This section details the different organizational theories that apply to this study. 2.1.1 Stakeholder theory and business sustainability

Organizations require holistic approach in all projects to deal with the mounting challenges faced by society (Schaltegger & Wagner, 2011; Silvius & Schipper, 2014). Some scholars advocating for greater consideration of the impact of business on the environment (Darus et al., 2019). In essence, these viewpoints mean that it is no longer business as usual for businesses. Husted and Salazar (2006) indicate that while it is not easy for many organizations to balance profit maximization, social value creation and environmental consideration, more and more companies are moving towards that. However, this transition is mainly from a strategic viewpoint because it makes business sense as the firm can be fined or shutdown (Husted & Salazar, 2006).

A stakeholder perspective by Freeman (1984) suggests that organizations are mandated to serve a purpose and that is to manage and serve their stakeholders (Harrison, Freeman & Cavalcanti Sa de Abreu, 2015). Werther and Chandler (2010) define a stakeholder as any entity that has the ability to affect or is affected by the organization’s goals or objectives. This implies that employees are central to organizations as they are part of the internal stakeholders that affect and are affected by what is done within the organization (Dentchev, 2009; Fassin, 2009; Baker, 2007). The effective management of stakeholders, creates a heightened level of positivity, engagement, understanding and organizational involvement (Harrison et al., 2015). However, it is not clear that organizations manage employee stakeholders well, therefore leaving room for grave apathy and several misunderstandings. Harrison et al. (2015) also purport there is a link with this line of doing business, good management and financial benefit. The argument is that this approach to business precepts sustainability of the firm in all aspects and not only financially (Freeman & Harrison, 1999)

Given the understanding that stakeholder approach is relevant and a means to achieve sustainability within firms and also accrue greater engagement of variety of stakeholders, yet many firms still don’t adopt this perspective. This is due in part to stakeholder theory being vague, often too simplistic, idealistic and ambiguous (Fassin, 2009; Dentchev, 2009). Another perspective of this theory is the difficulty in defining exactly where the boundaries of the firms exist and therefore a distinction as to who or what is a stakeholder or not (Waxenberger & Spence, 2003). Nonetheless, Waxenberger and Spence (2003) agree that despite all imperfections, stakeholder theory is a necessary means by which organizations can manage economic, social and environmental aspects relating to the firm.

Research on corporate and business approach to sustainability has gained traction over the past 25 years (Johnson & Schaltegger, 2016). A way to define sustainability is by using the “triple bottom line” (TBL) or “people, profit, planet” coined by Elkington (1998), depicting the connection between social, economic and environmental aspects taken into account in conducting business or running projects (Armenia et al., 2019). Although Freeman and Harrison (1999) highlight the importance of managing stakeholders for the sustainability of the organization, Elkington (1998) lays emphasis on the environmental aspect of sustainability, because this agenda is high on the list of younger generations, especially in Europe (Elkington, 1998). The upcoming generation are not only interested in how organizations perform financially, but also have a high interest on how organizations are working towards minimizing environmental and climate impact in addition to social value creation (Borim-de-Souza et al., 2019). It is estimated that SMEs have a huge substantial environmental impact contributing about

70% of global pollution collectively (Johnson & Schaltegger, 2016) and many organizations consider environmental impact reduction as recycling and waste management (Fatoki, 2018b). Organizations are facing increased pressure to assess social, environmental and economic stakeholders and their respective contribution towards sustainable development (Zhang, Hassan and Iqbal, 2020).

A universally accepted definition for sustainable development is that of the Brundtland Report, Our Common Future: defining sustainable development as “…development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development, 1987). Vallance, Perkins and Dixon (2011) in the paper titled “What is social sustainability: A clarification of concepts” suggest that the implication of this definition is that all aspects of sustainability are to be taken into account when conducting any kind of business activity, therefore necessitating a holistic view of business impact. This view was assumed even though the paper was focused on social sustainability. Westman, McKensie and Burch (2020) mention in their research that focus on business sustainability has always been on larger corporations and the role of SMEs have been missing in research. How organizations choose to affect their surroundings differs and the path chosen goes a long way to determine successful operations within the context.

2.1.2 Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)

When it comes to responsibilities of organizations, Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) is often mentioned. This is a term coined by Howard Bowen in 1953 in his work Social

Responsibilities of the Businessman and re-established in the new edition of the book (Bowen,

2013). When organizations interact with their surroundings in order to pursue common goals, societal resources are inherently tapped. The extent to which organizations adhere to these exploitative activities defines whether an organization performs CSR. CSR is defined as: “A view

of the corporation and its role in society that assumes a responsibility among firms to pursue goals in addition to profit maximization and a responsibility among a firm’s stakeholders to hold the firm accountable for its actions’’ (Werther & Chandler, 2010, p. 52). This means that businesses that

perform CSR go beyond their financial and legislative duties to adhere to societal and environmental demands. Werther and Chandler (2010) go on to discuss the difference between CSR, and SCSR (Strategic CSR). Literature also critiques these concepts, as often lacking substance, yet the general consensus is that CSR is beneficial to society and the environment. When it comes to South Africa, CSR activities are often argued as being a part of the apartheid spectrum and therefore rarely transcends beyond race and equality (Sampong et al., 2018). In developing countries, especially in South Africa, communities are disadvantaged into pressuring firms to engage in CSR due to the lack of resources and government requirements (Corrigan, 2019). Community perspectives and values are often not included and lead to an intrinsic feedback loop where organizations only answer to stakeholders within the organization rather than a broader society encompassing holistic approach (Corrigan, 2019). SCSR stipulates incorporation of CSR in a strategic context that will eventually lead to superior economic performance (Bocquet, Le Bas, Mothe and Poussing, 2019). Ezeoha, Uche and Ujunwa, (2020) mention that strategic CSR operates as a tool for self-interest and profit maximization, often within the African context. The moral legitimacy of strategic CSR is also questioned by Falkenberg and Brunsæl (2011), where the argument is made if firms engage in SCSR from an altruistic perspective or from a profit maximization perspective.

Stakeholders expect certain activities by organizations to have a positive effect on stakeholders and the environment. And even though publicly traded companies often disclose CSR activities in their Sustainability Reports (Sampong et al., 2018), SMEs are often overlooked. This notion is reaffirmed by Bocquet et al. (2019) whereby they stress the lack of research on SMEs and their CSR strategies. In addition, when it comes to CSR in developing countries there is a lack of CSR research (Jamali, 2007).

2.2 Leadership theories

The failure of business is often explained and attributed to the lack of knowledge and leadership acumen required to be successful (Urban & Naidoo, 2012). With the growing pressure for organizations to be sustainable (Borim-de-Souza et al., 2019), leadership is required to steer the organization in a sustainable direction. Going by the stakeholder theory of Freeman and Harrison, (1999), means that leadership and management must view the organization from a broader angle and not just in a narrow scope. The employees as part of the internal stakeholders have a contributing role to play in the sustainability success of the organization (Baker, 2007) as the employees carry out the day-to-day activities of the organization. Therefore, of importance is the perspective that employees are to be aware of implications for sustainability. Nonetheless, Urban and Naidoo (2012), emphasize that the onus lies on the owner or leader of the organization. Several leadership theories apply in relation to SMEs and sustainability.

2.2.1 Systems thinking in complexity and sustainability leadership

Rodrigues and Franco (2019) indicate that organizations have a vital role to play in the advancement of sustainability because organizations represent a productive part of economy’s resources. These resources vary from economic, infrastructure and human resource, which includes employees, yet many organizations have not incorporated sustainability in the management strategy of their organizations (Rodrigues & Franco, 2019). Hence, it becomes difficult to relay a sustainability message if the message does not come from the top. Several researches have looked into how this process of sustainability can be enhanced from a leadership aspect but limited research exist on the understanding of the employees or insights of the employees regarding this issue. (Uhl-Bien & Arena, 2017) posit that one way for leadership to tackle the transition towards sustainability is by adopting complexity leadership, primarily centred on adaptation. Complexity leadership enables effective organizational transition with the times and the societal demands, incorporating employee by elevating their level of understanding. This viewpoint involves looking at the organization and its challenges as part of the broader system (Senge et al., 2015), hence adopting mechanisms to tackle the problem as such. Although this theoretical standing looks plausible, it could be challenging to implement because this leadership perspective is a new field and has not been widely adopted by organizational leaders. To tackle complexity of the issues at hand, one has to apply systems thinking obtaining a comprehensive picture (Senge, 2006; Mella, 2008). Even though systems thinking can be defined seen as “…the ability to represent and assess dynamic complexity” (Arnold & Wade, 2015 p. 4), at the same time, this concept is vague and there is still no clear consensus on the definition of systems thinking.

Complexity recognises that the organization is part of a wider system and seeks the proactive involvement from employees for successful organizational change towards sustainability (Metcalf & Benn, 2013). This is particularly vital when one considers the SDGs are part of a universal, international agreement and the argument is made that these goals are to be viewed as such. However, on the contrary, without local implementation the goals are bound to fail (Malan, 2016). According to Quinn and Dalton (2009), leadership in guiding the organization’s move towards sustainability must reform, redesign and restructure their organizations to minimize negative impact. This might be the case for larger organizations with vast resources and a global footprint, but it is possible that the leaders at the helm of smaller organizations have neither interest nor capability in reforming, hence maintaining the status quo in organization’s operations. In this case, ideas for internal re-aligning do not necessarily come from leaders but possibly from employees from all levels that have a desire to change the direction of the organization (Quinn & Dalton, 2009).

Ferdig (2007) adopts the view that sustainability leadership is necessary but taking on a slightly different approach to the concept. Although acknowledging that sustainability leadership is required as stated by Metcalf and Benn (2013) and Quinn and Dalton (2009), Ferdig (2007) maintains that the leadership responsibilities does not only rest on specific leaders rather,

anyone within the organization has the capability to become a sustainability leader. This means that employees share the responsibility of rising to the challenge of helping solve the sustainability challenges faced in society. This is echoed in the statement that “instead of looking to others for guidance and solutions, we are called to look to the leader within ourselves.” (Ferdig, 2007 p. 26). However, Quinn and Dalton (2009) indicate that leadership is obligated to educate the employees on sustainability and also communicate the message effectively. In the same light, sustainability practices are to be incorporated in the day-to-day activities of the employees. This creates a tension between purported responsibilities of leaders and employees when it comes to advancing sustainability practices within organizations because leadership dictates the direction of the organization, but at the same time employees are charged with carrying out the objectives of the organization. Sustainability is a complex issue and its complexity is not to be underestimated. Therefore, leadership is to view employees are to be seen as assets, treated well and rewarded for their continuous progression towards sustainability (Quinn & Dalton, 2009).

2.2.2 Leader Member Exchange (LMX) and sustainability

Leader member exchange (LMX) focuses on the quality of relationship between employee and employer making the dyadic relationship between these parties the focal point of the process (Northouse, 2016; Stoffers et al., 2019). The understanding is that if the employers have a quality relationship with the employees, both actors feel empowered and motivated to suggest ideas (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995), thus producing desirable organizational outcomes (Story et al., 2013), which in this case are sustainability measures within the organization. Stoffers, Hendrikx, Habets and van der Heijden (2019) in their study of SME employees in Netherlands and Belgium posit that the theory of LMX is critical method to facilitate and enhance employee initiative and innovation within organizations (Jandhyala & Phene, 2015). This concept has an element of focus on the employees, but it is still very leader-centric and means that the privileges of the relationship is bestowed on the leader to grant influence to the employee (Uhl-Bien et al., 2014). In many organizations, employees look to leadership for support, guidance and encouragement to carry out assigned duties (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995), however, members in the organization who do not have a quality relationship with the leader might be side-lined together with their ideas. Hooper and Martin (2008) point out that while LMX has positive organizational effect, it is also possible the differentiation between relationships causes disharmony and inequality within the organization. This is to say that some employees, who are driven and able to contribute to sustainable practices within the organization, might not get the opportunity to do so because of their low-quality relationship with the leadership (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995); or such ideas are deemed to not be a priority for the leadership within the organization. This potentially causes friction between leadership and several employees, also between employees who enjoy and do not enjoy the quality relationship with the leadership (Hooper & Martin, 2008). The authors of this study posit that in a smaller organization, it is easier to build high quality relationships with most employees because the leader-employee dyad (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995), is not as expansive as in larger organizations. Thus, the leadership has an opportunity to create an environment whereby employees feel empowered to initiate sustainable practices, but the question is at what cost to the organization and the primary and formal duty of the employee.

2.3 Employee perspective

This section takes a look into the theory of organizational citizenship behaviour (OCB) and its relation to employees.

2.3.1 Organizational citizenship behaviour (OCB)

Employees are important stakeholders in any organization when it comes to advancing sustainability practices, especially related to the environment (Han, Wang and Yan, 2019). Employees and followers are essential to effective leadership but little attention has been paid to researching these actors due to the lack of understanding that leadership is a process of

influence with social, interactive relationships between people (Uhl-Bien et al., 2014). Given the numerous complex sustainability challenges faced by society, and the understanding that organizations are being looked upon to provide solutions, it is thus important to examine the role of employees in solution-creation. This is because solving the challenges requires a consolidated effort from all stakeholders within organizations and society at-large. Numerous researches have been conducted on the theory of organizational citizenship behaviour (OCB) and its relation to employees. Organizational citizenship behaviour, first identified by Bateman and Organ (1983) centres on actions of employees of an organization that go beyond their stipulated job requirements, which benefits the organization in a positive manner (Grego-Planer, 2019). Organ (1988) in his book defined OCB as “…work-related activities performed by employees that are discretionary, not directly or explicitly recognized by scope of job descriptions, contractual sanction, or formal reward system, and in the aggregate promotes the efficient and effective functioning of the organization” (p. 4). Farrell and Oczkowski (2012) conclude that research views OCB to have a positive impact on perceptions on service quality. Han et al. (2019) and Luu (2019) go on to examine the role and importance of employees as drivers of organizational green practices in line with environmental protection behaviour. The authors initiate the term organizational citizenship behaviour directed towards the environment (OCBE), stipulating actions of employees such as saving paper, decreasing energy consumption and making environmentally friendly recommendations to management. But, for the employees to engage in OCBE, there needs to be an element of responsible leadership, described as leadership that focuses on “the environment, sustainable value creation and positive change” (Han et al., 2019, p. 2), because this kind of leadership increases autonomous motivation. This form of leadership can also increase external motivation of employees via rewards and incentives for environmentally responsible behaviour, however this behaviour is more likely amongst employees who identify strongly with the leader and values of the organization (Farrell & Oczkowski, 2012).

Research has shown that organizational citizenship behaviour is both beneficial for the employee as well as the employee’s organization (Bateman & Organ, 1983), and this sort of behaviour partly deviates from the norms since it is not mandatory for the employee (Tuliao, Chen, Wu, 2020). The idea that this behaviour is not mandatory is a critical point of contention for various scholars. Zhao, Peng and Chen (2014) posit that although this behaviour is not mandatory, it is often expected of employees to engage in such behaviour thus putting unwarranted pressure on the employees. OCB can be a double-edge sword, especially in the case of SMEs where an employee could have multiple formal and informal roles leading to what becomes a “compulsory citizenship behaviour” (Zhao et al., 2014). In their study focused on understanding OCB of employees in the Philippines, Tuliao, Chen and Wu (2020) mention that one of the motivations of their study is that most studies of OCB have been conducted in the western context and limited research conducted in the developing context. A key element of the study is the idea that employee’s perceived institutional influence enhances their OCB, and this influence differs from context to context. This means that factors such as education, family, socio-emotional support have an impact on employee level of engagement in the organization. Nonetheless, there is a responsibility for the organization to remind the employees of the goals and the objectives of the organization for successful achievement (Tuliao et al., 2020). This is to say that for any sustainable practices and changes to be made, requires an explicit mention or discussion of such changes for greater engagement of employees, while being cognisant of the personal and contextual aspects. On the contrary, such explicit information might not be necessary, because sustainable practices might be carried out within organizations’ employees without explicit mention of it.

Grego-Planer (2019) stipulates OCB has two dimensions – frequency and intensity. As it relates to sustainability, the frequency is the number of employees that engage in sustainable practices and how many times they do so. The intensity is the quality of engagement and the degree or depth to which employees engage. Employees’ engagement in OCB can be seen as medium of

advancing knowledge-sharing within the organization (Grego-Planer, 2019) and spurs resource innovation (Jehanzeb & Mohanty, 2019). However, a challenge for organizations is that it is difficult to stimulate the occurrence of these behaviour given that it is voluntary (Moorman & Blakely, 1995), thus, leaving the responsibility up to the individual to advance such behaviour, that is otherwise not enforceable. Yet, these acts are informally recognized, implicitly implied within the organization, with no formal reward, and impacts on the personal lives of employees beyond the organization (Banwo & Du, 2020). Banwo and Du (2020) also state that OCB often feels obligated and could lead to increased stress. They found that especially among developing countries, forced OCB leads to an increase in perceived job stress, low work safety and poor work-life balance. Zhao et al. (2014) posit that the informal additional tasks outside the scope of employees’ regular activities may lead to negative reactions, especially when there are no formal rewards. Thus, for continuous OCB to occur, a certain level of employee psychological empowerment is required, and this empowerment is created by the quality leader-member exchange within the organization (Morton et al., 2019; Uhl-Bien et al., 2014). Another factor is that a level of trust (Ohemeng et al., 2019) and autonomy for the employees to take initiatives in creating a sustainable change (Morton et al., 2019). Even then, despite all these internal factors being present, there could still be external factors beyond the organizational setting that enable or inhibit the ability for employees to engage in sustainable initiatives.

3. Previous research

This chapter presents the previous research done on the key topics pertinent to this study and details the integration of theory in relation to the context of sustainable development. The chapter addresses the research on the sustainable development goals in relation to organizations and also diverse aspects of small and medium enterprises.

3.1 Organizations and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

In September 2015 at the UN headquarters in New York, nations met and committed to the United Nations (2015) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which constituted 17 global goals with 169 targets (Stafford-Smith et al., 2017). The UN considered these goals, as its largest and complex consultation process in its history. This might be the case but the achievement of these goals will be fruitless if it not universally implemented by governments, businesses, non-profit and several other actors involved. The goals give a platform for a comprehensive insight into tackling the complex challenges faced by society. These challenges include poverty, climate issues, health, infrastructure issues and so on. As seen in the figure, the goals deal with a wide range of issues and calls for collaborative effort for success, in the form of partnerships, indicated by goal 17.

Figure 3-1: Graphic of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): Retrieved from United Nations Website (United Nations, 2015)

These goals are considered to a large extent, an extension of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), which were crafted in the year 2000 in a United Nations meeting with 189 countries and various stakeholders (Ani, 2020). The MDGs were also put in place to tackle the challenges facing society of which a main focus was poverty. Ani (2020) mentions that a fundamental focus of the MDGs was to inhabit a world whereby no one was living under $1.25 dollar a day, yet achieving that was far from reality before the introduction of the SDGs in 2015. Having not achieved the MDGs; the argument is that the foundation is weak to achieve the SDGs, especially in developing countries (Ani, 2020).

Further, the SDGs provide a profound link to the social, economic and environmental aspects of sustainability (Stafford-Smith et al., 2017) and requires a holistic consideration by all actors and stakeholders during their operations. Ani, (2020) and Abisuga-Oyekunle et al. (2019) observe that the balance of the goals are nuanced and mostly embraced in developed countries. Looking at SDG 10 (reduced inequalities) this goal ironically aims at bridging the gap between the rich and the poor and in the global context, this is between the developed and the developing

countries. The rational is also applicable for large organizations and SMEs, the latter of which consider financial resource as one major challenge and skewed towards the larger organizations (Botha et al., 2020). Stafford-Smith et al. (2017), concur with this rationale but focus on Goal 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure) stating that within the realms of technology and innovation in the industry, the narrative is mainly on transfer of knowledge from developed to developing contexts thereby hindering the progression and opportunities for lower income countries to create and develop their technological pathways. Despite this view, Abisuga-Oyekunle et al. (2019) observe that there is no apparent advantage of size of a firm when it comes to innovation but rather innovation takes the practise of internationally available technologies and thus SMEs have to engage in a process of continuous innovation (Abisuga-Oyekunle et al., 2019). SMEs are constantly required to adapt to the current situation and their surroundings if they are to ensure sustainability.

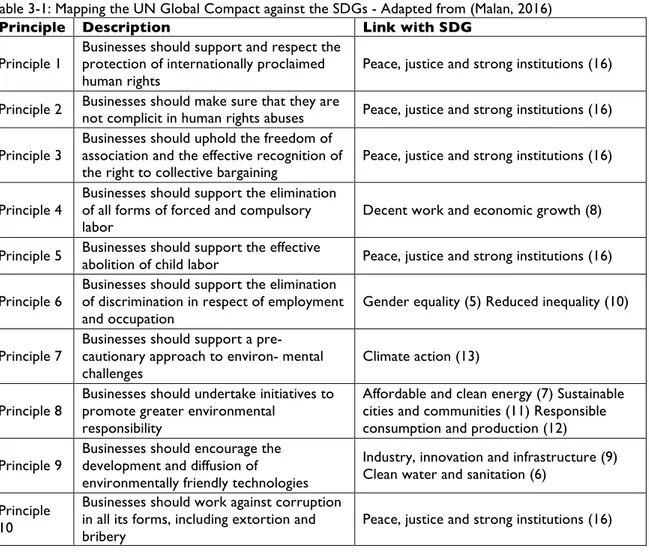

The role of National governments is well documented in that they play a vital role in implementing the SDGs, because policy is required for the integration of these goals on the national and local discourse level (Botha et al., 2020); better still companies are urged to adopt these goals in a show of their support for the goals (Malan, 2016). This show of support is encouraged through imbedding the SDGs in organizational core operations and reporting on these goals. Malan, (2016) also states that the SDGs cannot be discussed from a corporate perspective without mentioning the UN global compact. This compact is a set of 10 principles voluntarily adopted by big business organizations to implement sustainability and support the SDGs (Malan, 2016), but small and medium businesses make up a large workforce, therefore their alignment of these principles are also of important.

Table 3-1: Mapping the UN Global Compact against the SDGs - Adapted from (Malan, 2016)

Principle Description Link with SDG

Principle 1 Businesses should support and respect the protection of internationally proclaimed

human rights Peace, justice and strong institutions (16)

Principle 2 Businesses should make sure that they are not complicit in human rights abuses Peace, justice and strong institutions (16) Principle 3

Businesses should uphold the freedom of association and the effective recognition of

the right to collective bargaining Peace, justice and strong institutions (16) Principle 4 Businesses should support the elimination of all forms of forced and compulsory

labor Decent work and economic growth (8)

Principle 5 Businesses should support the effective abolition of child labor Peace, justice and strong institutions (16) Principle 6 Businesses should support the elimination of discrimination in respect of employment

and occupation Gender equality (5) Reduced inequality (10)

Principle 7

Businesses should support a pre- cautionary approach to environ- mental

challenges Climate action (13)

Principle 8 Businesses should undertake initiatives to promote greater environmental responsibility

Affordable and clean energy (7) Sustainable cities and communities (11) Responsible consumption and production (12) Principle 9 Businesses should encourage the development and diffusion of

environmentally friendly technologies

Industry, innovation and infrastructure (9) Clean water and sanitation (6)

Principle 10

Businesses should work against corruption in all its forms, including extortion and

The SDGs as a global initiative is important but it requires local integration to be effective and successful (Malan, 2016). Local infrastructure is needed to enable the advancement of the goals. The broadness of the goals also leaves room for misinterpretation and pursuance of private interest and agendas. The authors of this study posit that the SDG that directly relates to business and SMEs in particular is SDG 8 (decent work and economic growth). The implementation of best business practises is a primary way in which organizations can contribute to advancing the SDGs especially as it relates to economic sustainability. This particular goal can easily be implemented and understood by most businesses and SMEs are seen as a major contributing part to the advancement of this goal. SMEs constitute a major part of economic activity in most nations (Westman et al., 2020), and their contribution, and significance in the advancement of the SDGs, both in developed and developing countries requires scrutiny.

3.2 Challenges for sustainability in organizations

A drastic transformation in human behaviour is required to translate the idea of sustainability into tangible action (Ferdig, 2007). The first step for transformation towards sustainability is recognizing that we are facing a sustainability challenge. The phenomenon of sustainable development is such that it challenges all firms including SMEs (Masocha & Fatoki, 2018b). Masocha and Fatoki (2018b) also posit that one of the major challenges for fully embracing sustainability in firms is the lack of understanding of the issues and also the incapability to devise strategies to tackle them. This idea is seconded by Johnson and Schaltegger (2016) in stating that SMEs face internal and external shortcomings. They go on to state that lack of awareness of sustainability issues, and the absence of knowledge and expertise are some of the major internal challenges firms face. The point is driven home by Rodrigues and Franco (2019) in noting that the management of organizations do not have the necessary knowledge of what is required of them in relation to sustainability. Even though organizations provide sustainability report, still there is no added value when the reports are scrutinized (Rodrigues & Franco, 2019). However, organizations can also use sustainability to improve their image and reputation but this might not be a true reflection of the organizational mandate. Lack of government support is some countries is seen as a challenge to implementing sustainability, particularly in some sub-Saharan countries (Luken et al., 2019).

Organizations struggle to find the direction and the incentives to implement sustainability, as there is neither sufficient external incentives for doing so nor repercussion for not doing so (Johnson & Schaltegger, 2016). The implication therein is that many organizations perceive sustainability as an extra, unnecessary hassle and rather focus more on meeting the minimum required effort prescribed by the governing entity of the country of operation. Coetzee, Barac and Seligmann (2019) consider an ever-growing change in client and customer demand as a challenge to implementing sustainability but at the same time indicate that organizations, especially SMEs, need to cater for this demand to stay relevant. Although many organizations, SMEs in particular, still fail to grasp the comprehensive added value to sustainability, opportunities abound for those willing to take to bold step into the incorporating sustainable practices. A point of contention is that the internationally designed standards do no translate locally thereby making it difficult and adding to the complexity of implementation. Yet, incorporating sustainability management tools enables and foster innovation within the organization (Johnson & Schaltegger, 2016; Schaltegger & Wagner, 2011), and this is especially the case for SMEs which operate under highly dynamic business ecosystem (Šebestová & Sroka, 2020). Opportunities abound for firms to distinguish their business practice and to become the trendsetter for others to follow. One way of doing that is the by incorporating the sustainable development goals in their core business (Malan, 2016). It is of importance for all national governments, business and non-governmental entities to incorporate the SDGs (a universally accepted sustainability framework) to strive towards sustainable development (Malan, 2016).

3.3 Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs)

3.3.1 The characteristics of SMEs

Small and medium enterprises (SMEs) are defined according to the European Commission as: “Enterprises which employ fewer than 250 persons and which have an annual turnover not exceeding EUR 50 million, and/or an annual balance sheet total not exceeding EUR 43 million” (European Commission, 2015). In South Africa, the classification of SMEs is different per industry. It includes micro-enterprises (see Appendix A), and one can readily find the various industries and the classification that belongs to a particular size (Zulu, 2019). Micro enterprises fall under the umbrella of small enterprises in Europe; therefore, even though there are more classifications in South Africa the term SME encompasses approximately the same division of firms. SMEs play an essential role in the economies of many countries (Olawale & Garwe, 2010). In South Africa, SMEs contribute to 56% of the private sector employment, and to compare; in Belgium SMEs contribute to 69%, in the Netherlands SMEs contribute to 64% of employment (Stoffers et al., 2019). In Nigeria SMEs account for 60% of job opportunities (Nwokocha & Nwankwo, 2019) and Japan 70% (Asgary et al., 2020). Moreover, 91% of all registered businesses are SME’s (van Scheers, 2016). SMEs are responsible for 36% of South Africa’s GDP (Olawale & Garwe, 2010). Yet other articles report a 51-57% contribution to GDP (van Scheers, 2016). South Africa had a GDP of 348 billion dollars in 2019 (International Monetary Fund, 2020) which means that a total contribution of around 125 -198 billion dollars comes from SMEs.

Beneke et al. (2016) emphasize the limited amount of organizational resources SMEs possess, noting that SMEs usually lack the money, the workforce and the network that bigger firms do have and therefore are less resilient. SMEs have a higher failure rate, and in South Africa up to 60% of SMEs fail within the first two years of operations and up to 70% within the first 7 years of operation (Bushe, 2019). This percentage failure rate increases by at least 25% after major disaster such as pandemics (Asgary et al., 2020). In a Global Entrepreneurship Monitor report by Herrington, Kew and Mwanga (2017) it is stated that SMEs consist of three phases; the start-up phase (0-3 months), the growth phase (04-42 months) and the ‘’established phase’’ (>42 months) (Grater, Parry, and Viviers 2017). This means that between 60-90% fails before it even reaches the ‘’established phase’’, this number is confirmed by (van Scheers, 2016). However, it also noted that compared to larger organizations, SMEs are more resilient, flexible and can adapt quicker to challenges (Kossyva et al., 2014).

Even though literature mentions the approximate time period in which an SME are relatively safe from defaulting or crumbling, there is also a significant variety in literature pertaining to the different characteristics that determine whether an SME is in financially safer waters. The vast scope of descriptions in literature therefore cannot pinpoint the exact time when an SME becomes successful. Even though, there is consensus that the first few years are the most uncertain, Urban and Naidoo (2012) argue that an SME should not only be financially sustainable but should also be looking for expansion of their infrastructure and increasing the number of staff (Urban & Naidoo, 2012); thus adding to the complexity of the SMEs’ existence. In the same study the number of staff in SMEs was analysed and it turned out that the majority (64%) of SMEs have less than 5 employees while only 12% of SMEs employs more than 35 employees. The small odds of survival are also made know in that only 1% of SMEs make it even past the micro phase (Rogerson, 2000). Even though there is a high failure rate, new enterprises are continuously created and Schumpeter (1934) is one of the first scholars to argue that ‘’creative destruction’’ as he calls it leads to an enriched economy (Block et al., 2017). Despite the significance of SME contribution, often times the dismal percentage of SME survival in South Africa is not caused by being outcompeted by other enterprises or failing to meet the demand of the market. There are a multitude of other factors that lead to the demise of SMEs and these factors are discussed in subsequent sections.

3.3.2 SME contribution to economies

When one considers an SME failure rate of 60% within two years, the question becomes whether SMEs are burdens or benefits to society. A high failure rate consequently leads to the loss of jobs. However, literature is rather united when it comes to the benefits that SMEs have on society. Even though there is a large percentage of SMEs that go out of business, SMEs are also very important for the prosperity of a country (Abisuga-Oyekunle et al., 2019). Bushe (2019) argues that SMEs lead to numerous societal advantages on a regional and national scale thereby impacting government, cities, as well as the households. These advantages are often displayed through the creation of employment and livelihood, more tax income for municipalities and governments and a higher gross domestic product, which in turn positively affects government budgets. These advantages linked to SMEs have considerable societal impacts and alleviate the burden on society by contributing to a more stable economy and counter the chances of stagnation or recession of the country/countries in which they operate (Bushe, 2019).

Not only do SMEs contribute to the economic stability of a country, it also contributes to the innovative environment. As mentioned before, Schumpeter (1934) coined the term ‘’creative destruction’’, and almost a century later this train of thought still holds and is widely discussed within SME literature. As stated by Abisuga-Oyekunle et al. (2019) increased entrepreneurship and competition lead to efficiency of the organization and innovation within the industry. Moreover, in the same article by Abisuga-Oyekunle et al. (2019) it is argued that the productivity and level of innovation surpasses that of bigger organizations, however SMEs are more fragile, hence the high failure rate. Also, government investment in SMEs can lead to a national decrease in unemployment and poverty (Abisuga-Oyekunle et al., 2019). Grater, Parry and Viviers (2017) add that SMEs can contribute to using the available labour force in such a way that talent is not going to waste, therefore resulting in slowing down the poverty cycle due to the right allocation of human resources and organizational education. Urban and Naidoo (2012) stress the importance of upgrading the levels of expertise within SMEs in order to achieve more economic growth and an increase in employment. This includes finding ways to educate staff in a way that works to enhance their collective literacy (Urban & Naidoo, 2012).

Evidently, SMEs hold a particular importance to society and the impact of SMEs is small on an individual level but together this sector has significant impact, both environmentally as well as socio-economically (Westman et al., 2020; Schaper, 2002). However it is also notable is that that their impact is harder to measure and this is especially the case with SMEs in South Africa (Grater et al., 2017). In their study on realising the potential of SMEs in developing countries, Grater et al. (2017) discovered that there are numerous unregistered SMEs in South Africa, therefore the total number and impact is unknown and could economically be even greater than currently measured. The contribution of SMEs however does often fail to reach the political level discourse level and Grater et al. (2017) denote that SMEs are subdued when it comes to lobbying. Moreover, smaller organizations often do not often appear on the radar of big buyers or contractors, such as government contracts, because they lack the network that bigger organizations have (Beneke et al., 2016).

3.3.3 SME-specific challenges

As previously noted, SMEs contribute significantly to a nations’ socio-economic wellbeing, however, they also face a lot of challenges that can impair survival (Grater et al., 2017). Literature is expansive when it comes to the amount of challenges that SMEs face in comparison to larger organizations, stipulating the different types of challenges that SMEs can come across, and this may have to do with different socio-cultural contexts in each country (Asgary et al., 2020). This means that every country or region has different factors that may lead to challenges, and at the same time different sectors within the country or region face different challenges (Rogerson, 2000). Some countries face increased environmental risks, others may face more legislative risks (Coetzee et al., 2019). All these challenges cause SMEs to be exposed to variables that impair growth and even existence.

Even though these challenges are obstacles for SMEs, they inherently exist within societies regardless of the existence of the enterprises (Bushe, 2019). Therefore, it can be argued that new SMEs already enter a rough environment rather than them being exposed by challenges due to managerial decisions (Olawale & Garwe, 2010). Olawale and Garwe (2010) researched the ranking of obstacles and found out that a third of the obstacles were intrinsic, owner induced obstacles, and two-thirds were environmental factors. From a macro-economic perspective there are various scholars who reached consensus on the most common challenge among SMEs. There is a pilage literature when it comes to the challenges SMEs face. Olawale and Garwe (2010) name high interest rates, high taxes, and recession as the most challenging factors that impair survival of SMEs. van Scheers (2016) adds unemployment and income equality. In an article by Asgary et al. (2020), high inflation is mentioned as a risk factor for SMEs, while Nieuwenhuizen (2019) mentions the regulatory and legislative environment of a country or municipality as causing challenges for SMEs.

On an organizational level there is an abundance of challenges, which could be seen as obstacles for SMEs. Literature describes a lack of an owners’ managerial skills and their experience as entrepreneurs in a new organization to manage and train staff as well as a lack of credit/credit history as catalysts for failure (van Scheers, 2016). The inability to downscale, due to the small size of especially small enterprises in order to save costs, combined with their brittle financial structure, where they often rely on credit, decreases resilience (Arzeni, 2009). A changing network of suppliers, operational costs, networks and inconsistent productivity impair the likelihood of survival of SMEs (Urban & Naidoo, 2012). There are various organizational challenges that impair survival of SMEs and even when the above-mentioned risks are mitigated, survival is not a guarantee.

Environmental challenges can bankrupt any organization regardless of their organizational performance (Asgary et al., 2020). When it comes to environmental challenges the geographical region an SME operates in, is important. Not all SMEs face the same environmental challenges. This adds to the complexity of the SME industry. Asgary et al. (2020) mention that almost half of the United States SMEs shut their doors within the first two years after a disaster has struck. Also SMEs in developing and underdeveloped countries don’t have the resources to tackle potential external influences on their business. Though, it varies widely on the region in which SMEs operate. Japan for example faces floods and earthquakes that impair the survival of business and in Turkey only 30% of SMEs invests in insurance for natural disaster-induced damages (Asgary et al., 2020). Droughts in Australia lead to damage of infrastructures (Linnenluecke & Griffiths, 2010) which according to Olawale and Garwe (2010) is also a major representation of obstacles to the growth of SMEs.

3.3.4 SMEs in Developing vs. Developed countries

The statistics of SMEs worldwide indicate that SMEs contribute to all nations’ prosperity, when one looks at the amount of SMEs that are present in a country, the percentage of GDP and the level of employment contribution. The challenges that developing countries face compared to developed countries are different. The main difference lies in the macro economic structure of a country and the level of organizational professionalism since natural disasters happen in both developed as developing countries (Mahul & Ghesquiere, 2010). Yet, macro-economic and organizational structures vary throughout the world (Nieuwenhuizen, 2019). As Asgary et al. (2020) state, Australia, Japan and Turkey are all casualties of natural disasters yet in Turkey not all SMEs insure themselves against natural disaster-induced damages and consequently are also the most underinsured sectors (Asgary et al., 2020). Even though natural disasters happen globally, the level of economic advancement does not decrease the likelihood of being subject to damages by natural disasters. The rate at which SMEs recover has therefore more to do with the macro-economic structure and the organizational expertise (Linnenluecke & Griffiths, 2010). Some differences between the challenges for SMEs in underdeveloped/developing countries and