Exploring a

future where

the Internet

is God

byNina Cecilie Højholdt May 2018

Thesis project

Interaction Design Master at K3 / Malmö University / Sweden

Supervisor : Henrik Svarrer Larsen Examination on May 29th 2018 Examiner : Per Linde

2. edition

Abstract

This research project seeks to create an encounter with the internet which nourishes the user’s relationship to the technology and celebrates it for its positive ideals. In order to do this, it draws on a speculative design approach, and explores which artefacts and rituals might exist in a possible future where the internet has taken on the role of technology today. Aspects from rituals and religious practice are used in order to create an experience that can be engaging, reflective and tranquil. The outcome of the project is an interactive shrine for the home, where the owner might practice their devotions to the internet through a designed ritual, as well as an accompanying narrative in the form of a sacred text. The design was the center of a focus group in which the participants collaboratively discussed, speculated about- and made meaning of issues surrounding the internet and religion. The research highlights the importance of the body, branching into the whole sensory apparatus, in religious practice, and makes an argument for the importance of the interplay between mind and body in interaction design.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my supervisor Henrik Svarrer Larsen for inspiring and intellectually stimulating conversations. Thank you for asking challenging questions throughout the process.

A big thank you to my fellow students at Malmö University, with whom I had exciting debates, thorough feedback sessions and great critique on my design work.

To the people who participated in my focus group, who allowed me to ask them abstract and provocative questions and in turn provided me with intriguing perspectives and opinions.

And lastly, thank you to all the people who offered their inputs and perspectives on my work, both on request and unsolicited.

Abstract 3

Acknowledgements 3

1. Introduction 6

1.1 Problem space 6

1.2 Presentation of the final concept 7

1.3 Related work 9

1.4 Ethics 11

2. Theoretical grounding 12

2.1 Artefacts as Mediators (What Things Do) 12

2.2 Embodied interaction 13

3. Methodology 16

3.1 Research through Design 16

3.2 Speculative Design 17

3.3 Doing design work 19

4. Rituals 21

4.1 Designing new rituals 22

5. Early experiments and inquiries 23

5.1 Talking to people about religion 23

5.2 Experiencing religion and spirituality 24

5.3 Constructing rituals 25

6. A shrine for the internet 27

6.1 Shrines and prayer beads 28

6.2 Analysis of common elements in rituals 32

6.3 Developing The Shrine 34

7. Focus group 40

7.1 Selection of respondents 40

7.2 Overview 40

7.3 Notable findings 41

8. Discussion and research outcomes 42

8.1 A speculative artefact 43

8.3 Learning from religion 45

9. Conclusion 47 References 48 Appendix A 52 Appendix B 54 Appendix C 56

1. Introduction

Few would dispute the fact that computation, and especially the internet, is increasingly moving into the uttermost intimate parts of our lives. Not only is it helping us solve problems and be more effective at work, we use it to communicate with loved ones, sharing secrets, getting medical help, keeping track of our health (everything from eating habits to our menstrual cycles), knowing where to be and how to get there, and so on. To put it briefly, the internet mediates an immense part of our daily lives. However, as our lives are becoming increasingly intertwined with this internet, nurturing our relationship with the technology itself should be important. This project seeks to use interaction design as a way to create an encounter with technology (namely the internet), not just through technology. As such, the focus is on creating an experience that serves a reflective purpose, rather than using the internet as a mediating utility.

As the internet develops and grows, so does its misuse. The technology can become abusive, discriminative and disturbing. Privacy and surveillance concerns, social engineering, persuasive design for addiction, and stress, are all issues that have increased over the recent years (Center for Humane Technology, n.d.). This is an unfortunate development. This research project departs in a belief that the internet is inherently good. Its foundations are good. If we look at the original ideals of the internet (namely the www), we see values such as “open”, “free”, “collaborative” and “creativity” (Solon, 2017). I therefore believe in the importance of creating experiences with the internet

emphasizing on the positive opportunities, and taking responsibility as a designer, by creating things that do good. Whether this be through concepts, products or experiences that embody these ideals, or through a more critical design practice.

1.1 Problem space

To sum up, this research project focuses on creating a positive experience with the internet, and through this, inviting the user to reflect on their relationship with it as more than a utilitarian entity. In order to achieve this, I will seek to examine how one might draw on elements of religious and ritualistic practice, using their perceived potential for creating engaging, serene and meaningful experiences. At first sight, this combination of religion and interaction design might seem like an ill-matched couple, and indeed, it has twisted some brows throughout the study. However, as written by philosopher Alain de Botton, it is possible, from a non-religious point of view, to find religion “sporadically useful, interesting and consoling – and be curious as to the possibilities of importing certain of their ideas and practices into the secular realm” (2012, p. 11-12). And as this paper will show, interaction design and religious practice share more similarities than first anticipated, and it has indeed been a particularly interesting lens through which to explore our relation with the internet.

This thesis is framed as a speculative design project. Using this approach, the project seeks to create a narrative wherein the internet has taken on the role of religion in today’s/past society. When people engage with the artefacts constituting the narrative, it seeks to create an experience where they can have a tranquil, positive and reflective experience not only through technology but also with technology. Distilling this framing into concise questions guiding the research then becomes:

What kind of interactive artefact might exist in a possible future where the internet has taken the role of religion today?

How could the process of designing and assessing such an artefact take shape?

What similarities exist between interaction design and religious practice, and what can interaction design learn from religious practice?

1.2 Presentation of the final concept

Having explored the above mentioned problem space through research and designerly practice, a final concept and prototype has been produced. The creation of this artefact can be seen as both a way of obtaining knowledge throughout the process, as well as an implicit theoretical contribution itself.

Imagine a future where the internet is something we actively celebrate, praise, trust in and devote ourselves to. A future where we see it for the immense power of connecting the world, transcending borders and breaking down barriers. With this project, the hope is for a future where the internet will be celebrated for its utopian foundations, not this increasingly dystopian reality. To quote Dunne & Raby (2007/2008), this object is created in anticipation of that time.

Figure 1. The Shrine

The Shrine is a home altar where the owner can practice their daily devotions towards the internet, the all knowing God. By interacting with The Shrine, they are able to have a tranquil experience with their beloved technology, opening up a positive space for reflection.

The Shrine is focused around a set of artefacts and accompanying ritual, and by engaging with the ritual a manifestation of the deity (the internet) will appear. By doing the sequence prescribed by the ritual, the owner will experience a range of activities, engaging most of the senses and their body, which in turn makes the spirit change and sounds play. The ritual is designed to provide a

ceremonial feeling, but also leaves time for the user’s personal agenda; whether they wish to reflect on the values of the internet or pray for a better connection to Netflix is completely up to them. Furthermore, they are welcome to explore The Shrine outside of the ritual, making their own meaning.

The Shrine and the designed ritual can be seen in the concept video found here.

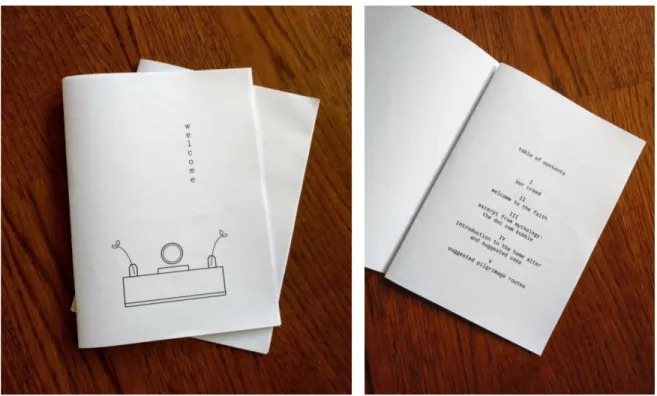

The Shrine is accompanied by a set of sacred texts, The Book of Clouds, introducing new owners to The Shrine’s capabilities, as well as core beliefs, central stories and myths, suggested pilgrimage routes, and so on.

Figure 2. The Book of Clouds

1.3 Related work

This section will present a series of works that are related to the endeavours of this project. They are divided into two categories: Work related to technology and religion, and work related to interaction design and religion. In the first category, two newer religious movements will be presented;

Syntheism and Kopimism.

The second category highlights two selected projects of relevance within interaction design and HCI. When surveying the internet and library for examples, the selection was not abundant, however, as the following will show, some interesting articles and projects were found.

1.3.1 Syntheism and Kopimism

This project is certainly not the first to create a religious movement around technology, although the ambitions here might differ from Syntheism and Kopimism. However, they both offered some interesting, as well as provocative ideas.

Syntheism is a movement striving to offer the same kinds of feelings to atheists and pantheists that religion offers religious people. It does not have a single source, but here I will focus on Bard’s (2013) interpretation of it. He argues that the God is something we ourselves can create, a representation of

all humanity’s hopes and dreams. He then proceeds to conceptualize four gods (arguing that four are better than one), where one of them is the internet.

The Missionary Church of Kopimism, on the other hand, has a more practical purpose and ideology; they believe that the search for knowledge is sacred, and that all information should be open and free. As quoted from their website they “believe that copying and the sharing of information is the best and most beautiful that is.” (Det Missionerande Kopimistsamfundet, n.d.).

1.3.2 Mixing Technology and Religion

In the article Sabbath Day Home Automation: “It’s Like Mixing Technology and Religion” Woodruff, Augustin & Foucault (2007) describe the use of technology, in particular smart home systems, in orthodox jewish households during sabbath.

While not the main focus of the article, I believe it makes a compelling argument for how religion and technology can co-exist and how technology does not have to be kept out of everything sacred. In jewish faith, the Sabbath is a time of peace, relaxation and reflection, and therefore a number of activities are proscribed. As society has evolved, so have the prohibited activities, which now include turning electrical devices on or off. But by using home automation systems, the jewish families interviewed were able to use technology to perform mundane activities such as turning on and off the lights in their home. While it might seem curious at first, this was done in order to support their religious practice and spiritual experience, and was, according to the article, “enhancing” the Sabbath experience.

1.3.3 A digital butsudan

Through two related, but separate projects, Uriu & Okude and Urui & Odom explored the creation of interactive Japanese Buddhist family altars (butsudan) for supporting domestic practices of

memorialization. ThanatoFenestra: Photographic Family Altar Supporting a Ritual to Pray for the Deceased (Uriu & Okude, 2010) was the initial project, wherein the authors discussed the creation of a new Japanese ritual for the dead. Six years later, more thorough work on a second edition was published, this time under the name Fenestra, in Designing for Domestic Memorialization and Remembrance: A Field Study of Fenestra in Japan (Uriu & Odom, 2016).

The work is highly inspiring, as it showcases a well-designed example of an interactive take on a religious artefact and accompanying ritual. The work took departure in the traditional butsudan, a home shrine for one’s ancestors, but by adding interactive elements and new rituals, were able to create an engaging and meaningful way of venerating the dead.

One important takeaway from the second version of the project, is the sensitivity needed when designing for religious contexts, especially surrounding something as delicate as passed loved ones. The authors described how some undesirable encounters with the technology had occured during their field studies, when the IR sensor in the artefact had unintentionally been triggered. This would

show the participants pictures of their deceased loved ones, without them themselves having initiated the ritual. Understandably, this was unsettling to some.

However, this project also provided inspiration on a conceptual and executional level. For example, the authors described how they used mirror glass in the installation in order to potentially evoke contemplation, by seeing one’s own reflection in the piece.

1.4 Ethics

While a designer should always consider the ethical aspects of their projects, some topics call for more attention than others. This is perhaps one of them.

Throughout the project, it has been important to be sensitive towards the implications that working with technology and religion might cause. For some (especially here in Scandinavia (Bard, 2013)), religion is a delicate and uncomfortable topic to discuss. And as I am not a religious or spiritual person myself, I have sought to provide extra attention to the tensions that might arise from the discussion of- and designing with religious elements. As mentioned, the Fenestra project (Uriu & Odom, 2016) detailed how their project created some undesirable encounters, as their technology failed to work precisely as expected.

In continuation hereof, it is also important to consider my role as a white, western designer, when bringing in elements from various cultures and religions. I acknowledge that there are many things about the cultures I include that I don’t know, and I hope that my investigations, analysis and applications are seen as respectful and rich.

2. Theoretical grounding

This chapter will cover the theory laying the ground for this project, as well as my general practice as an interaction designer. It explains the foundations from which I understand the world, how it can be shaped through design, and what to keep in mind when doing so.

It will first go through Verbeek’s (2005) writing on the mediating role of technology and artefacts. From that, the concept of embodied interaction will be explained, based on Dourish (2004), as well as the field of tangible interaction.

2.1 Artefacts as Mediators (What Things Do)

In the book What Things Do, Verbeek (2005) philosophises on the role of technology in our lives, and how it mediates and shapes our actions and perceptions. Verbeek challenges the idea of technology as a dominating force, and instead makes a case for describing technology “in a more nuanced light than the terms of the classical philosophy of technology allowed” (p. 203). However, I will not begin to describe Verbeek’s break with classical philosophy of technology (i.e. Heidegger). Instead, I will examine how Verbeek sees technological artefacts as something shaping our world, and how this is important in interaction design practice. Verbeek himself focuses on industrial design, “because this discipline concerns artifacts that play a large role in everyday social life” (p. 204). However, I would argue that with the advancement in technology and the growth of interaction design, many of these ideas apply to our field as well.

Verbeek describes how products have a functional value (what they do) and a meaning or sign-value (what they express on a social/cultural level). Furthermore, in virtue of their design, products have semiotic functions; their form shape their meaning. Two types of semiotic functions are classified, their denotative functions (what it is and how to use it, which could be seen as related to Norman’s interpretation of affordances) and their connotative functions (their symbolic function, e.g. the lifestyle they appeal to). The secondary (symbolic) functions of products also refer to the culture they represent, e.g. the owner of the artefacts' values, that are represented in the object. Verbeek’s post-phenomenological perspective however, takes this a step further and also addresses how culture is shaped by the objects we experience the world through. Whereas the semiotic perspective deals with how objects refer to a specific social order, the post-phenomenological approach focuses on how objects shape this social order.

This, Verbeek argues, is not another function of the product, but rather a byproduct of its

functionality; a phenomenon that arises from the product's functionality. “In fulfilling their functions, artifacts do more than function - they shape a relation between human beings and their world” (p. 208). This mediating role is not consciously experienced by people, it takes place on a sensory level; “perceptions and actions always have an aspect of sensorial contact with reality, which is precisely

the point of application for mediation by material artifacts” (p. 209). In other words, this is what we, as designers, should be aware of.

Verbeek argues that there is a certain one-sidedness in aesthetics of design, in that the visual aesthetics are in focus. Rather, he argues, that aesthetics should be extended to the whole sensory apparatus, as the things we design are often meant to be more than looked at. If mediation arises from the functionality of a product, and therefore through its use, the aesthetics of design can be extended to how products shape the world, not just how they look and what lifestyle they represent. This is indeed relevant to interaction design, and especially the subfield of tangible interaction (which will be described in the following section). When we design artifacts that have a certain physicality or tactile dimension (as opposed to “just” screen-based interactions), we much consider the aesthetics of the touch, sound, and so on, just as we consider the visual qualities. Furthermore, Verbeek’s perspectives of technology and artefacts as mediators might apply to all areas of interaction design. When we create something, be it a product, an experience or a service, it is important to be aware of how these artefacts will shape the experienced world of the humans engaging with it.

2.2 Embodied interaction

Where Verbeek focuses on the philosophy of technology in general, Paul Dourish in his book Where the Action Is - The Foundations of Embodied Interaction (2001), targets Human-Computer

Interaction. Based on phenomenology, Dourish focuses on the term embodiment and establishes the concept of embodied interaction. This form of interaction is seen in tangible- and social computing which both rely on similar scientific theoretical approaches.

To Dourish, embodiment is a foundational out of which meaning and action arise, and a central concept in phenomenology. He takes departure in philosophers such as Husserl, Heidegger and Merleau-Ponty (who’s theories are beyond the scope of this project) and extends the concept to HCI. As he explains, “Embodied phenomena are ones we encounter directly rather than abstractly. [...] we, and our actions, are embodied elements of the everyday world.” (p. 100). As such, embodied

phenomena are those occurring in real time and space and grounded in everyday experiences. Embodiment does not merely mean having physical properties, but rather it is a relationship between action and meaning (p. 126).

Embodied Interaction is then “the creation, manipulation, and sharing of meaning through engaged interaction with artifacts” (p. 126). These computational artefacts inhabit the same physical and social world as us, and this is capitalized on in the interaction.

2.2.1 Tangible Interaction

Along with social computing, which this paper will not discuss, Dourish explains tangible computing in relation to embodied interaction. Tangible interaction is a wide term which has been explored by

many, but can generally be defined as computation that goes beyond the traditional interfaces of personal computers and move into the environment which we inhabit. As such, it is related to ubiquitous computing. Much work in the realm of tangible computing has been done since Dourish’ book - the Tangible Media Group at MIT for example, are continuously expanding the practice, now also working with what they call ‘Radical Atoms’ - a vision for the future where the physical material itself can change form based on interaction (Tangible Media Group, n.d.). However, this project will focus on the more current world of tangible computing.

In his paper from a little over ten years later, Epilogue: Where the Action Was, Wasn’t, Should Have Been, and Might Yet Be (2013), Dourish stresses that embodied interaction is not exclusively found in tangible computing, but rather it is a fruitful place to explore the notion.

Dourish (2001) explains how tangible interaction capitalizes on our familiarity with the everyday world, or rather, “the way we experience the everyday world” (p. 17) - which is through direct interaction. It can take a wide range of forms, both inhabiting familiar objects or entirely new

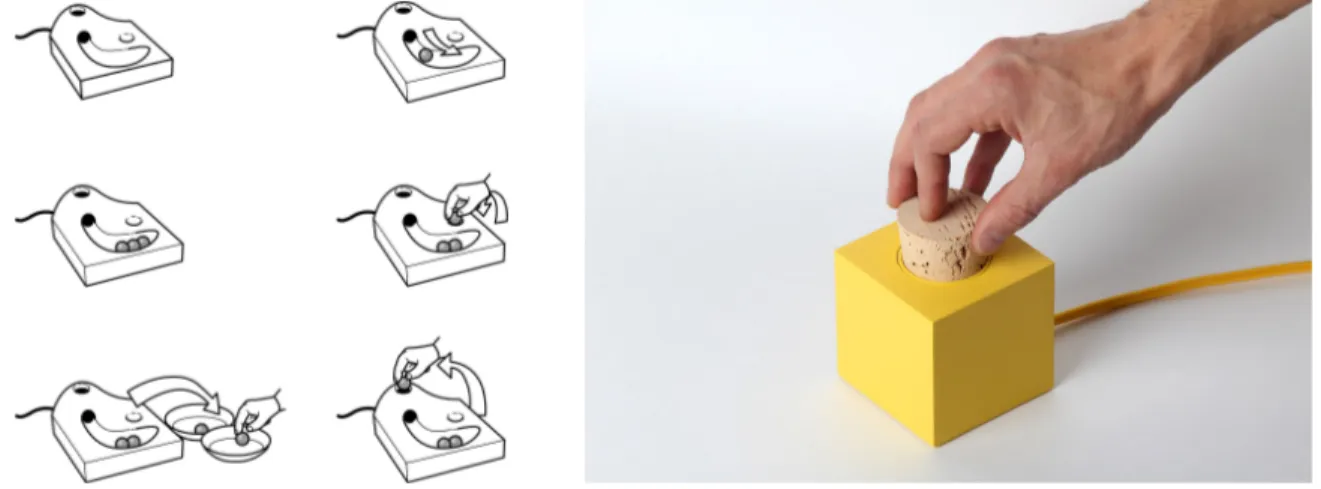

artifacts. A canonical example of a familiar object is Bishop’s Marble Answering Machine (Figure 3A), also mentioned by Dourish. A more recent example is the Plugg radio by Norwegian design studio Skrekkøgle (Figure 3B). The interaction with the radio is much simpler than the Marble Answering Machine, but it is still a tangible user interface; in order to turn the radio on, the user simply has to remove the cork plug from the radio’s speaker. When the cork is plugged back in, the radio turns off.

Figure 3A and 3B. The Marble Answering Machine (Bishop, n.d.) and Plugg Radio (Skrekkøgle, 2012).

In the category of completely new products, an example could be Thero by spanish designers Román Torre and Ángeles Angulo (2017). The artefact, an access point, allows its owner to physically manage their privacy settings on the network. By rotating the lid of the artefact, users may choose between 4 privacy settings, from completely open to complete blackout (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Thero (Torre, 2017)

Moving away from the familiar boundaries of the screen and into the world of tangible artefacts obviously poses new challenges. However, the solution to these issues are found in the nature of the physicality of the new interfaces themselves. In tangible computing, the physical properties of the artefact suggest how it might be used, just as in product design for example. This is similar to the semiotic denotative functions as described by Verbeek (2005). As an interaction designer, however, this also means that one must carefully consider the formgiving when designing tangible

computational artefacts.

3. Methodology

This chapter will describe the scientific method for this thesis, and the use of programmatic design research and speculative design as the major methodical approaches.

3.1 Research through Design

Like many other (Löwgren, 2007; Löwgren, Larsen & Hobye, 2013), I see interaction design as a design discipline, and myself as a designer. My research is therefore not based on a positivist approach, but rather design research, and the growing tradition of Research through Design (RtD). That is, “a research approach that employs methods and processes from design practice as a legitimate method of inquiry” (Zimmerman, Stolterman & Forlizzi, 2010, p. 310). Design research and RtD takes designerly practice as central to engaging with- and creating knowledge about the issue at hand. It concerns itself with research of the future, and the artefact resulting from the designerly engagement can itself be seen as an implicit knowledge contribution (Zimmerman, Stolterman & Forlizzi, 2010; Löwgren, 2007)

3.1.1 Programmatic Design Research

In my practice, I am very much inspired by programmatic design research (Löwgren, Larsen & Hobye, 2013; Hobye, 2014; Larsen, 2015) and the ideology permeating it. For a number of reasons, however, I have not directly adopted the way of programmatic design research in this project. Firstly, it was not until quite late in the process that I opened my eyes for the possibilities of the approach, which regrettably made the adaption futile. Secondly, it is questionable how fitting programmatic design research could have been, even if applied from day one, as it seems more appropriate for longer processes; keep in mind that this thesis project lasted just nine weeks. And lastly, I am aware that this approach is quite young, and might not prove suitable for all endeavours.

This, however, has not stopped me from adopting some of the qualities that I find the most appealing, as they are much in agreement with my own designerly practice.

Programmatic design research stands as a frame for exploration (Hobye, 2014) and embrace a holistic perspective, where experiments, experiences, openness, complexity of the designerly process, tacit knowledge and serendipity all are of value. It does not have any hopes of being able to define an end-goal at the beginning of the process; the outcome matures with the obtaining of new knowledge, fueled by the designer’s engagements. For this project, it has meant making a virtue out of this ongoing process of redefining my problem space; as we gain new insights into our topic (be it from literature, inquiries or doing design), it seems inevitable that our understanding, and therefore framing, of the problem at hand changes and matures. This does not mean jumping from topic to topic without a clear goal, but rather embracing the fact that new knowledge (especially in such an explorative topic as mine) will flavor the problem space.

A phenomenological perspective

Programmatic design research also ties in well with the phenomenological (and

post-phenomenological) worldview as much of the theory in Section 2 is based on. This also goes for my chosen research topic, as spiritual practice is indeed a very subjective matter, and so are rituals as noted by Levy (2015). While the discussion of phenomenology in interaction design could be (and undoubtedly has been) a whole phd worthy, I will draw on my understanding, although highly limited, of the theory as a guiding philosophy. Phenomenology is about exploring human experience, and the research following this philosophy will thus be guided by different ideals than the positivist research approaches. Stienstra (2015) writes that in order to embrace the complexity, holistic and continuous context that comes with phenomenology, we need to break with the paradigm of generalizability and objectivity in contemporary science.

3.2 Speculative Design

Research through Design is, as noted by Zimmerman et al. (2010), research of the future. “This focus on the future and the focus on concretely defining a preferred state allows researchers to become more active and intentional constructors of the world they desire.” (p. 310)

However, how the designer chooses to explore these futures vary greatly. One approach, which I have undertaken in this project, is that of speculative design. Here the word approach should be stressed, as speculative design should not be seen as a general method for this project. Speculative design seeks to “create spaces for discussion and debate about alternative ways of being, and to inspire and encourage people’s imaginations to flow freely” (Dunne & Raby, 2013, p. 2). This is done through a design practice that asks “what if” questions and seeks to open up a space for debate about the future; what is desirable and what is not?

For this, Dunne & Raby (2013) uses a diagram illustrating different kinds of potential futures (see Figure 5). The scope goes from the probable to the possible, and in between we find the plausible, as well as what Dunne & Raby calls the preferable future, intersecting between the probable and the plausible. In this project, this approach is used to speculate on a future where the internet is celebrated for its positive values, rather than focusing on the abusive and damagining uses of the technology that currently saturate the technology. This is my approach to designing for preferable future.

Figure 5. Adopted from Dunne & Raby (2013)

My approach to using speculative design is also one based on fiction. By creating a fictional narrative as a part of the design work, the design can be set free of the current norms, predictions and trends, and thereby be free to explore social and ethical issues. Using a level of fiction in one’s design “requires viewers to suspend their disbelief and allow their imaginations to wander, to momentarily forget how things are now, and wonder about how things could be” (Dunne & Raby, 2013, p. 3).

Furthermore, this project’s use of speculative design also steps into the realm of conceptual design. This is design that is about ideas, but also ideals, that allow designers to stimulate their imagination and open up for new possibilities in technology, materials and manufacturing. It is not necessarily useful or feasible designs for the market, but rather “hypothetical or, more accurately, fictional products to explore possible technological futures” (Dunne & Raby, 2013, p. 14). By being presented as real products, people are able to explore ethical and social issues with these concepts in the context of normal life.

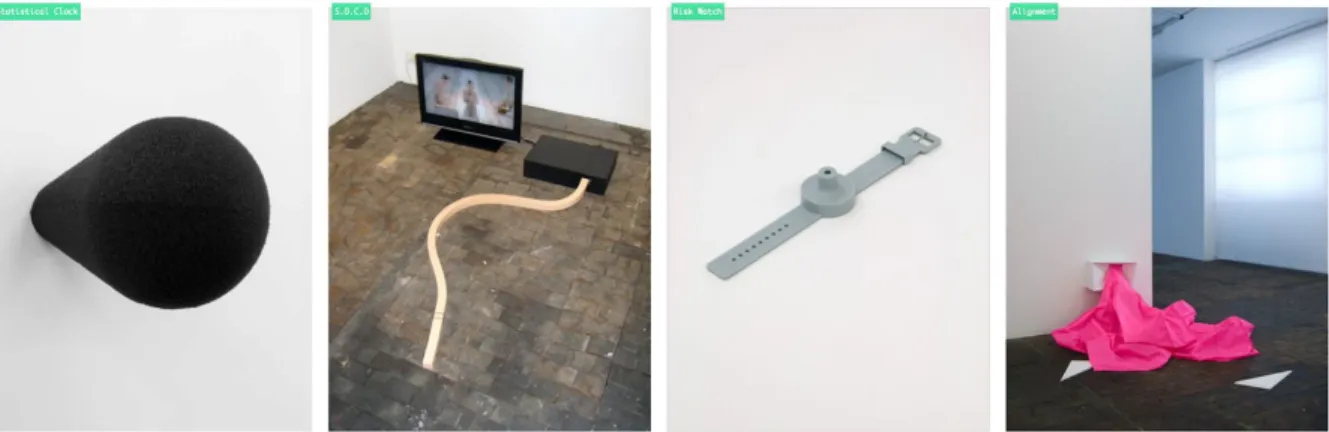

3.2.1 Do You Want To Replace The Existing Normal?

One example of Speculative Design that I will draw on as inspiration for this project is Do You Want to Replace the Existing Normal? by Dunne & Raby themselves (2007-2008). Through four artefacts they explore human needs and desires and speculate how these might be more complex and subtle in the future. As they write “In this project we are hoping for a time when we will have more complex and subtle everyday needs than we do today. These objects are designed in anticipation of that time. Patiently waiting. Maybe they are utopian.” (Dunne & Raby, n.d.)

Figure 6. Do You Want to Replace the Existing Normal? (Dunne & Raby, 2007-2008)

The quote above displays the design ideals for this project. Just like one might not see any need for a device informing you of the political stability of the country you are currently located in (which is the ‘function’ of one of the pieces in Dunne & Raby’s project above), this design project does not aim to create something that provides a ‘necessary’ function or experience. However, the point of

speculative artefacts like these is not to provide a solution to a problem or providing you with a valuable service. Rather, they seek to open up a curious space for questioning, wonderment and reflection. Much in line with the speculative design approach of asking questions, rather than answering them, the designs do not solve problems, they create them. Do You Want to Replace the Existing Normal? does this in a very poetic way. The artefacts are subtle, simple in form and function, but curious and sometimes unsettling. It is the discussions and reflections, both internally and with other people, that make them valuable, their strangeness forcing people to consider possibilities and futures they might not have imagined otherwise.

3.3 Doing design work

To wrap up this chapter, here follows a short section on the methods applied when doing design work. As mentioned in the first section, I see myself as a designer, and reflecting on one’s designerly practice is therefore important too.

Sketching and prototyping are naturally part of how a concept is ideated and developed. In 2006 Holmquist wrote the article Sketching in Hardware where he argued “Whereas the graphic designer can sketch on paper, and the product designer can make mock-ups in wood or clay, a sketch of an interactive product has to express not only the static look of an interface, but also its dynamic properties.” (p. 47). The article ended with a hope for a future where sketching in hardware was not only possible in virtue of the tools available, but also an integrated part of design education

such as Arduino, Processing, Wekinator and also techniques such as laser cutting, it is possible to quickly create interactive sketches, adding temporal and transformative properties to the traditionally static technique. In my practice, I use hardware and software sketching on the same level as the ones in pen and paper. Hardware and software sketching allows for whole new levels of the mind - sketch conversation as proposed by Buxton (2010), or Schön’s idea of seeing-moving-seeing (1992). While a hardware or software sketch might take initially more work than simple strokes of a pen on paper, they open up for whole new possibilities. As an example, one is able to transform the whole expression of the sketch by changing one variable or adding a simple line of code. Furthermore, just as Buxton (2010) describes the strength in ambiguity of one’s sketches, as it allows for fruitful (mis)interpretations, software and hardware sketches can lead to interesting mistakes. Sometimes the code you write will not do as intended, but instead offer a surprising new encounter.

4. Rituals

In order to create a positive, and conceivably engaging and reflective experience with the internet, I draw on ritualistic practice. The study of ritual is a vast field, and as such, the ambition of this section is humble. It seeks only to convey the theory that has been used as a guiding principle for this project. The interest in coupling technology and religion came long before any idea had formed, and for a long time, the focus lay on mythology, rather than ritual. However, as the project formed and my interest in the bodily and sensory aspects of religion increased (as will be eminent in the design process in chapter 6), so did the focus on ritual. Rituals are not exclusive to religion, but they are among some of the most obvious ones (Petrelli & Light, 2014)

Levy (2015) write that rituals “are not rigid procedures, but as described from a phenomenological perspective, a seemingly established series of actions or activities from which experiential meaning emerges” (p. 1). Rituals can exist in a myriad of forms and contexts, and according to Bell (1997) even a handshake can be considered a ritual. Levy (2015) and Levy & Hengevel (2016) differentiate rituals from routines in that they focus on the quality of the process, rather than the quality of the outcome. As such, engagement is seen as vital to ritual. Furthermore, they make a distinction between everyday rituals and ceremonial rituals, where ceremonial rituals have shared practice within a community, as well as a higher degree of formality . 1

Bell (1997) define six categories of ritual action (“a pragmatic compromise between completeness and simplicity” (p. 94)). These are rites of passage, calendrical and commemorative rites; rites of exchange and communion; rites of affliction; rites of feasting, fasting, and festivals; and political rituals. She also offers a perspective on ritual-like activities, which illustrate that ritualization can be more flexible, and are able to shine a light on the activities of more classic rituals. According to her, we, in Western culture, “tend to think of ritual as a matter of special activities inherently different from daily routine action and closely linked to the sacralities of tradition and organized religion” (p. 138). However, many activities can contain levels of ritual aspects, such as formalism and sacral symbolism.

What is particularly interesting here, is how she notes the importance of the body in these activities and its moving in space and time. This extends into classic examples of rituals too, however, due to the emphasis on tradition and the enactment of codified or standardized actions, it can be hard to see, as we take much for granted when considering ritualistic acts. The environment of the ritual is created and organized by means of how bodies act within it, rather than the bodily acts being a response to the environment (p. 139).

4.1 Designing new rituals

Petrelli & Light (2014) write that the idea that rituals are a “given” and are unchanged with remote origins is a common misconception. There are many examples of rituals being constructed, both in newer and older times. As such, it is also possible for new rituals to arise, for example by

formalization, or by repetition. Bell (1997) for example describe a system of invented rituals in the soviet union, “for the explicit purpose of social control and political indoctrination, a dimension that most citizens clearly understood” (p. 225). An example here is the ritual of initiation into the working class, where factory workers would stage an elaborate ritual, a kind of rite of passage, to welcome new workers into the factory.

By the extent that rituals have been invented throughout history, as Levy (2015) and Levy & Henveld (2016) also argue, it must be possible to also design them.

Petrelli & Light (2014) provide three core concepts of rituals as cultural performance. Cultural performance is an approach to studying rituals, which sees their symbolic content as a mean for communication. Furthermore, it looks at the semantics of the ritual, i.e. the values expressed (p. 16:6). These three core concepts might be useful when seeking to design a new ritual. They are:

● a ritual is an event that expresses cultural values and affects people’s perception; ● participants are active, and the sensorial aspect of taking part is important; ● ritual performances are “framed” in some ways to contrast with everyday life

The rituals are implemented through multisensorial expressions, which is important as it triggers both physical and emotional engagement. Lastly, they stand outside of the mundane, maintaining a clear separation between that and the exceptional (p. 16:8)

Based on previous research, Levy & Hengeveld (2016) argue that there are two starting points for designing rituals; actions and artefacts. One might either start with a set of artefacts and through those explore the sequence of actions composing the ritual. Or one might use an already existing sequence of actions, in order to enhance the experience by reconsidering the artefacts (p. 3)

5. Early experiments and inquiries

In this chapter, I will explain some of the preliminary activities that helped shape my problem space, bring direction to the project, and laid a foundation for my future design work. The first section outlines some of the initial conversations I had with people about my topic, the second provides insights from a field trip to a protestant church at Easter service, and the third describe a small workshop carried out with two colleagues on the construction of a funeral ritual for a smartphone.

5.1 Talking to people about religion

Throughout my process, I have had many conversations about my topic with people, both

spontaneous and more structured. I have talked to colleagues, friends and family, and their varied perspectives on both technology and religion has provided valuable insights and ideas. Most of these have been in occurances of casual conversation, and as such, they are not correctly documented. In some cases, I have taken notes during the conversation, which can be found in Appendix A. However, because of the limited documentation, I am aware of how they affect the project’s criticizability, and I therefore use the insights as inspiration and as a way to gain new perspectives, not as generalizable scientific data.

5.1.1 Religion Envy

In his TED Talk, What if the Internet is God?, Alexander Bard (2013) talks about “religion envy” - a feeling of jealousy on religious people that a non-believer can experience, which I questioned a few people about. Two friends both voiced that they certainly felt religion envy at times. One said that she felt it the most in hard times; it would be comforting to have something to project one’s frustration onto, and believe that one was not necessarily in control of what $was happening. The other emphasized the community often surrounding a religion as her main source of envy; she thought that the kinship existing for example in a church must be nice. From an analytical

perspective, it seemed that these two friends both envied the perceived comfort of religion highly. In addition to the above mentioned friends, a family member was also questioned about religion envy. She proved somewhat more cynical however, and mainly saw religion as a form of escapism; as a way of disclaim responsibility in times of hardship, for example. However, she did note that she saw comfort in that, and could see how that would be attractive to many people.

These perspectives encouraged further investigation of a religious take on engaging with technology. Would it in any way be possible to help fill the void of religion envy?

5.2 Experiencing religion and spirituality

One of the personal major challenges of this project, is being a non-religious and non-spiritual person. In addition to my reading and designerly activities around these topics, I have searched for ways of encountering religious and spiritual experiences.

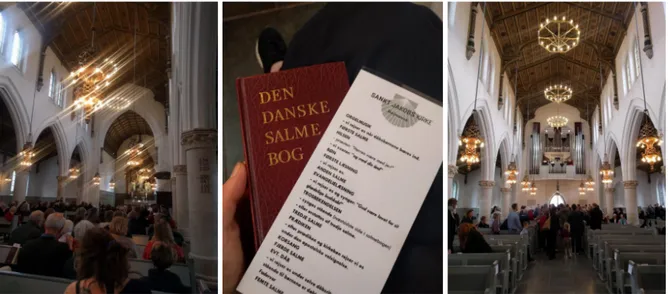

One inquiry was going to a church service on Easter sunday. By living in a mainly Christian country, the Protestant church was the most familiar, and I therefore hoped it would be able to provide insights without a high “barrier of entry”. Furthermore, the Easter sunday sermon is one of the most important events in christianity, so this day was chosen in order to get the “full experience”.

The two main takeaways in regards to what spiked my interest was the actions and rituals being performed, and the feeling of serenity and solemnity.

In his TED Talk “Atheism 2.0” de Botton (2011) observes the importance of the body in religious practice; “The other thing that religions know is we're not just brains, we are also bodies. [...] a physical action backs up a philosophical idea. We don't tend to do that. Our ideas are in one area and our behavior with our bodies is in another. Religions are fascinating in the way they try and combine the two." Having taken particular interest in the bodily aspect of religion, I paid specific attention to the actions one had to perform during the service. The continuous act of standing up and sitting down provided structure to the sermon and served as a way of engaging the congregation. By knowing what and when to do the actions, a sense of comfort was achieved; there were no uncertainties. It also encouraged togetherness in congregation by doing these actions in unison. Another interesting aspect was the Eucharist. Here, the congregation went up to the altar where they kneeled and received the bread and wine. In addition to the bodily action of kneeling, the sense of taste was also engaged, providing another dimension to the experience.

The mere act of entering the church provided a sense of serenity and sacredness. The architecture, history, number of people gathered and the rituals themselves all heightened this feeling. This set the experience of the service much outside the mundanity of everyday life, and provided room for thoughts and reflections which one might not encounter usually.

Figure 7. Images from the church service

5.3 Constructing rituals

In order to gain some insights and inspiration for potential rituals related to computational technology, I held a small workshop experience with two colleagues. Having spent a lot of time researching rituals, and in relation to that coming up with a lot of interesting possible connections and designs for a possible future, I wanted to talk about these ideas with outsiders and gain new perspectives, ideas and angles.

Furthermore, structuring an experiment about this forced me to concretize the knowledge I had gained so far. The findings made about rituals would have to be translated into something outsiders could work with in the experiment.

The two colleagues participating both knew the major details about my research project, but did not have specific knowledge about it. This proved very fitting, as I did not have to spend time explaining the project, but could get designerly insights and fresh perspectives.

The workshop was centered around constructing a funeral ritual for a smartphone. The example was chosen as funeral rites exist in most (if not all) cultures and times, and often carry strong

connotations to that culture’s worldview, tradition, cultural practice, etc. The smartphone was chosen as it’s a good example of a piece of computation that everyone can relate to and hold dear.

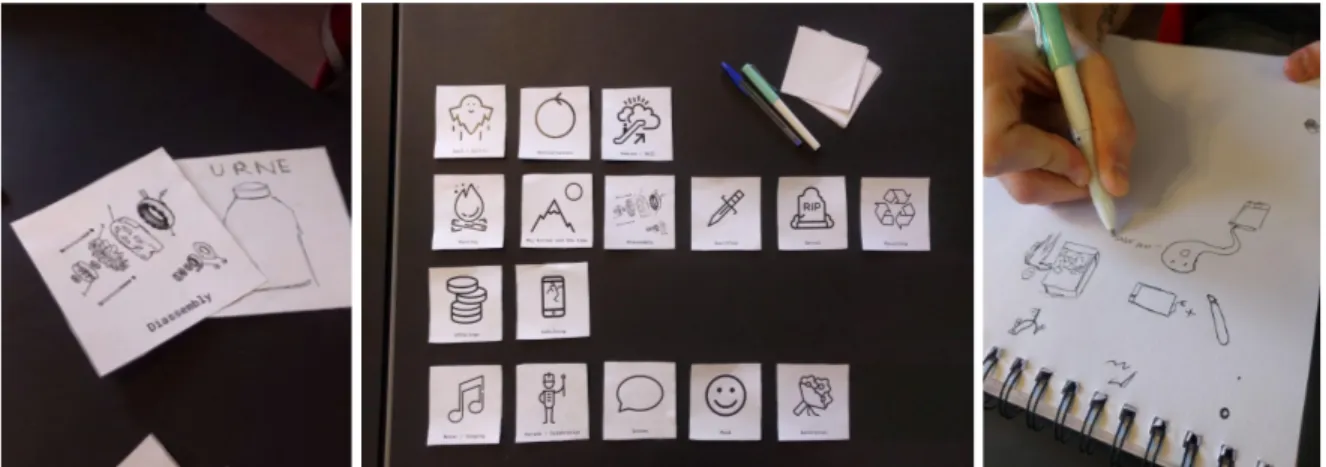

To stimulate the conversation, I made conversation-starter cards, illustrating various elements of typical funeral rites (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Constructing rituals workshop

The workshop was in practice the three of us talking, with me guiding the conversation by the use of the cards and examples from many different cultures. When making up the rites, we would group the related cards together. If the conversation mentioned elements not existing on any of the cards, I would draw a new one.

Many of the insights gained were very specific to the funeral topic, which was not worked on further, so they will not be mentioned here. However, some interesting conversation about the life and death of technology emerged. If a smartphone has a soul, what is it then? Is it in the cloud, able to

reincarnate and wander from hardware body to hardware body? If your phone knows everything about its owner, and its data is its soul, is it just a copy of its owner then?

It was also discussed that the components or specifications of the phone would not be important; it was about your relationship to it. As such there was no doubt that one could have a substantial relationship to one’s phone. Both participants agreed that what you have with technology today is a relationship, not just something you use.

6. A shrine for the internet

Having now explained the some of the early experiments in the process, this chapter will present the design process, rationale and work that is the continuation hereof and led me to the final concept. The general focus throughout the design process was designing one or more artefacts that would support a ritual for a positive experience with the internet.

The process was a bricolage of all the knowledge gained from early inquiries, theory read, backtalk from sketches and prototypes, feedback from colleagues, and everything in between. It was more like the squiggle in Figure 9, than say, the double diamond model or Buxton’s (2010) design funnel.

Figure 9. An illustration of the Design Process

However, for ease of reading it has been divided into iterations, all containing one or more

experiments which lead to the final concept. Furthermore, a number of key insights will be noted in brief, which is an attempt at synthesizing some of the knowledge gained at certain points in the process, and which drove the designing forward. The first one stems from the initial research, and is therefore presented here.

KEY INSIGHT 1: Religion and the body

Religion recognizes the importance of the interplay between mind and body. Through bodily actions, the philosophy of the religion is backed up and taught (de Botton, 2011). One example is the mikveh in Judaism, where the physical action of taking a bath supports the idea of cleansing and forgiveness. Others could be in meditation, where the stillness of the body supports the stillness of the mind, metaphorically and physically, or the act of kneeling in the Christian church, to show submission in front of God.

This relationship between body and mind lead the project towards the focus on embodied interaction.

6.1 Shrines and prayer beads

While numerous sketches on all kinds of ideas were made in the initial phases of the project, this section begins with two ideas that were more concrete and stemmed from the knowledge gained from theories and inquiries at the time.

The bodily aspect of religious practice (see Key Insight 1) quickly formed as a focal point of the project. This did not necessarily mean involving the whole body in grandios movements, but rather keeping in mind that we experience the world with more than our eyes, ears and the tapping of fingers on a mouse or screen.

Figure 10. “How the computer sees us” (Igoe & O’Sullivan, 2004)

As a result, working within the field of tangible interaction (see Section 2.2.1) seemed obvious, and the sketching commenced. The ideas ranged from very speculative, to something that could easily exist in today’s society. Many concepts were idealized and discarded, but two stuck and were selected for further development, which I will outline in the following.

6.1.1 Prayer beads

The first concept was a set of augmented prayer beads, that would support a user in their religious practice (towards the internet). Prayer beads exist in a wide range of religions (the rosary in the Catholic church, malas in Buddhism and Hinduism, misbahas in Islam), as a way to guide one’s practice and make sure the correct number of prayers, mantras or tasbihs are recited.

The concept of prayer beads was interesting, as they offer a tactile dimension to a believers devotions; the act of rotating the beads in one’s hand is directly related to the prayer being carried out. This would fit well within the context of embodied interaction and tangible computing.

Figure 11. Hardware and paper sketches of the prayer beads

Numerous ideas with the augmented prayer beads were sketched, including ideas of a vibration reminding the user of their daily prayers, color changing based on events on the internet, an accompanying display in the home (or perhaps even an app on your phone), and so on.

One of the main challenges of the prayer beads would be the technical dimension, in regards to the size. Usually prayer beads are not very large, as they have to be able to be counted with one hand. While the prototype would be doable, although perhaps awkward in size, realizing a final prototype of higher fidelity would come with greater difficulties. One example of this, would be the project by Ou et al. (2015), in where they sought to embed a GPS tracking device in prayer beads, in order to detect early-stage dementia. While the project is clearly more focused on the engineering than the design of the prayer beads, it is a good example of the difficulties in embedding a microcomputer into something as delicate as prayer beads, especially in an elegant way.

Figure 12. Prayer beads with GPS device embedded (Ou et al., 2015)

It should be noted that at the time of writing, I have become aware of a “smart” prayer bead product by Acer, designed to assist Taiwanese Buddhist in their prayer, which is indeed very elegant . 2

2

https://www.theverge.com/2018/3/5/17081574/acer-smart-beads-count-buddhist-mantras-taiwan-r eligious (Accessed 18th May, 2018)

6.1.2 The shrine

The second major idea, was an altar or shrine, that one could keep in their home and use for daily spiritual practice. Like the prayer beads, home altars and shrines exist in many religions and cultures, and are especially prevalent in eastern religions. Examples include house shrines for the daily hindu puja and the Japanese butsudan and kamidana (the first being for spirits of the dead, the second for gods (Nakamaki, 1983)).

While not directly related to the bodily aspect, The Shrine had appeal for three reasons. Firstly, it could work almost as a platform, allowing multiple ideas to form within it, in regards to the artefacts and tools placed in and on The Shrine. Home shrines and altars typically have a wide range of items placed around it, used to assist the daily worship and spiritual practice (e.g. bells, candles, incense). These artefacts could be computational and as such compose the tangible interface.

Secondly, by placing it in the context of the home, it might be able to provide a comfortable environment for spiritual engagement. While churches and temples have the power of setting itself outside of everyday life, it could be interesting to create a dedicated space to spiritual practice in the mundane setting of the home. Would it be possible to transfer the serene and ceremonial feeling I experienced at the church service (Section 5.2) into one’s living room?

Lastly, it would be feasible to make a working final prototype of a shrine, as its larger form could accommodate embedded electronics easily.

Figure 13. Home altars/shrines from Catholicism, Hinduism and Shinto

Some very inspirational concepts from readings were the yorishiro and shintai in Japanese Shinto religion. These are symbolic material objects wherein a kami (god) settles, and it is through these objects that people can communicate with the gods (Nakamaki, 1983). The yorishiro must regularly be the focus of ritual performance, and in Japanese tradition, they can exist in all kinds of objects, from rocks and trees, to man-made things such as paper decorations and even the toilet (Nakamaki, 1983). The kamidana, the altar used for home rites, has an important shintai, often in the form of a round mirror.

Figure 14. A Japanese kamidana. Note the round mirror acting as the shintai.

One idea for the shintai or object of worship (e.g. a murti (image or statue of a deity) in Hinduism or the Buddha Shakyamuni in Buddhism), was using the home router. While not the object of praise itself, it could be a representative or manifestation of a god in one’s home.

Another was to make The Shrine more like the Japanese Buddhist butsudan and use it to praise technology that had passed away, e.g. one’s old iPod or the smartphone that could no longer turn on. Here, one could keep representations of the passed, and I could experiment with making urns or spirit tablets (Southeast Asian plates, used in memorial of passed ancestors), and creating a ritual for the veneration of the “dead”.

Figure 15. Sketches of the router as a representation of God

6.1.3 Feedback session

With the two concepts (prayer beads and shrine), I conducted a feedback session with two

colleagues, in order to gain qualified critique on the relevance, feasibility and substance of the ideas. The concepts were presented in paper and hardware sketches.

While I had initially hoped to realize both concepts, perhaps even adding a third one, in order to make a trinity of artefacts, both colleagues agreed that the idea of the shrine carried the most essence and potential. They argued that the shrine itself could support a myriad of interactions and sub-concepts, and that focusing on the one would have a positive influence on the future design process, both in terms of time restrictions and conceptual boundaries. Furthermore, the reasons that the prayer beads would be harder to realize, not only from a technical perspective, but also because they would come with other challenges such as the ergonomic dimension.

This feedback was much valued. As a designer, it can be hard to discard ideas, especially ones you see great potential in. However, the points they made were sensible, and it was decided to let go of the prayer beads, and focus completely on the shrine.

KEY INSIGHT 2: Rituals

While the attention to the body is present in much religious practice, it is especially prominent in rituals, where it is an integral part of the performance. Here one might again mention the mikveh, or the Muslim bowing, ruku and sujud.

Furthermore, rituals often incorporate a number of ceremonial artefacts, “utilized as a means for establishing or maintaining communication between the sacred (the transcendent, or supernatural, realm) and the profane (the realm of time, space, and cause and effect).” (Auboyer, n.d., n.p.) These artefacts can contain properties necessary for the worship and can take a myriad of shapes and meanings.

This combination of bodily aspects and artefacts makes for a compelling framing of rituals as the central focus of exploring technology from a religious perspective. It also supports the approach of tangible interaction.

6.2 Analysis of common elements in rituals

As the shrine was decided to be the concept of further development, more inspiration for what to include in the shrine was sought for. In order to gain this, an analysis of artefacts and elements in various religious was made. The analysis is obviously not exhaustive and may have overlooked important parts of some religions. The elements examined are for example mostly limited to

Buddhism, Hinduism, Shinto, Judaism and Christianity. However, populating the dataset provided a large bank of inspiration and a greater understand of the vast topic of religious rituals and artefacts.

Figure 16. Affinity Clustering of ritualistic elements

Throughout the process, extensive reading about religions and rituals have been carried out, and each time a new ritual or ritualistic element or artefact was encountered, it was written down. The first step of the analysis was to gather all of these and write them down on individual sticky notes. Some were highly specific, like the atang food offerings in the Philippines or the Hindu ghanta bell. Others were more general, like incense sticks or prayer beads, both of which exist in many religions. After writing all the elements down, and further researching more, affinity clustering was performed, in order to group the elements into more general themes. Here, the senses quickly emerged as a general theme. Other groupings would definitely have been interesting too; e.g. who or what this element is directed at (a deity, an ancestor, oneself), what purpose the element serves (praising a deity or spirit, making offerings, self-reflection), and so on. However, the categorization related to the senses proved interesting and provided great insight. The final categories were Sound, Taste, Smell, Gestures & Movements and Offerings.

The observant reader might see that Touch and Sight are missing, and that Offerings is the odd one out. However, rather than using “touch” as a category, Gestures & Movements seemed to

encapsulate the data better, as many rituals include specific patterns of kinesis. An example from this category would be the raka and sujud from Muslim prayer, which entails bowing and pressing the nose and forehead to the ground. Here we see the whole body being engaged in the ritual. Offerings is indeed not a sense either, however, it encapsulated many interesting concepts in ritualistic practice, for example the burning of spirit money (also known as joss paper) in China. Spirit money is paper, which is “usually burned in order to solicit favors from the gods, provide the dead with the cash they need to take care of business in the courts and hells of the underworld, bribe celestial bureaucrats, and placate offending demons or interfering ghosts.” (Bell, 1997, p. 110). Unsurprisingly, some elements also fell between categories. As an example, the Shinto concept of kashiwade, clapping ones hands before a shrine, was categorized between Gestures & Movements and Sound. The act, used to capture the deity’s attention, is a bodily gesture, but the sound arising from the gesture is also interesting, as it engages the outside world in the ritual as well. Other

examples of sound in ritual practice include bells, which exist in many religions, hereunder the suzu, again from Shinto.

In the Taste category are the Christian ritual of Eucharist, here referring to the bread and wine that is consumed, and the eumbok which is a part of the Korean jesa memorial, where everyone partakes in the consumption of the food offerings. As noted by Bell (1997) “Shared participation in a food feast is a common ritual means for defining and reaffirming the full extent of the human and cosmic

community” (p.123)

Incense is widely used in religious ritual practice, and the most dominating practice in the Smell category. It is often seen in the form of sticks (Hinduism, Buddhism, Shinto), or in a thurible in Christian denominations. Another interesting element in this category, is the act of smelling in the Jewish havdalah ritual; here, a container of fragrant spices is passed around for everyone to smell.

For a list of each element in the analysis and the following clustering, see Appendix B.

As mentioned before, this analysis provided the design process with a large bank of elements for inspiration, as well as a deeper understanding of elements across religions and cultures. In the following iteration, it will be seen that the analysis proved a starting point for trying to engage all the senses in the final shrine.

KEY INSIGHT 3: The whole sensory apparatus

As evident from the analysis, religious rituals have a way of engaging the body that extends into the whole sensory apparatus. While gestures and movements are important, the body in all of its richness is brought into the ritual, through multisensorial expressions, triggering both physical and emotional engagement (Petrelli & Light, 2014)

This might be connected with Verbeek’s (2007) notion that aesthetics should be extended beyond that of the visual, into the realm of the sensuous, as “perceptions and actions always have an aspect of sensorial contact with reality, which is precisely the point of application for mediation by material artifacts” (p. 209).

6.3 Developing The Shrine

Following the analysis of common artefacts in rituals, a longer sketching-prototyping-sketching period followed, where I sought to explore how the shrine could take form, what ritual it might contain and what artefacts might support this.

The form ended up going in the direction of the aforementioned Shinto kamidana, more than e.g. a butsudan or Catholic home altar. A kamidana “has the religious function of endowing space with

purity, sanctity and security” (Nakamaki, 1983, p. 76), and it being the place of worship for many kinds of deities (rather than just one’s ancestors or a specific prophet). A myriad of tools were experimented with, seeking to engage as many senses as possible in the ritual. Some ideas were discarded because of their inability to enchant or inspire, while others sadly had to go because of technical challenges.

Figure 17. Cardboard and wood Prototypes of The Shrine

6.3.1 Elements and ritual

Designing the artefacts and ritual was a constant negotiation. For example, an idea for a ritualistic action would inspire an artefact, or an artefact’s technical challenges would limit the creation of an action, or the other way around. However, the big picture, the ritual designed was one of exchange and communion according to Bell’s (1997) categorization. These rituals “appear to invoke very complex relations of mutual interdependence between the human and the divine.” (p. 109), and fitted well within the context of The Shrine. The puja as earlier mentioned is an example of this kind of ritual.

Figure 18. Sketches of possible elements in The Shrine

The Shrine contains two kinds of interactions; direct and indirect. The direct interactions are those openly traceable by the user, the kind of elements that have a cause and effect. The indirect are those developing over time, that might be more peripheral. In the final prototype the latter are

(unfortunately) the ones that suffered the time constrictions the most, but they include elements such as sounds playing, slight changes in the representation of the spirit and flickering in the lights on The Shrine. The more direct interactions and elements are described in the following.

The yorishiro

In the evaluation in Section 6.1.3, the idea of an interactive yorishiro or shintai was presented. The idea was much supported, and having an object for the spirit to manifest itself in at the center of The Shrine was therefore the object of much sketching and prototyping. Various ideas for a

non-traditional display and manifestations were contemplated, but a screen with a graphical

representation of the spirit was chosen for a number of reasons. Firstly, this allowed to work with the metaphor of the traditional shintai; a small round mirror that the deity manifests itself in. Using elements of existing ritualistic practice, but in novel ways seemed compelling. Secondly, the mirror itself offered possibilities. With inspiration from the Fenestra project (Uriu & Odem, 2016), mirror glass was placed in front of a display, so that one could see both the screen and one’s reflection. Seeing one’s own face when reflected in the manifestation of the spirit when looking at the display then could perhaps evoke feelings of contemplation.

Figure 19. Software sketches of the representation of the spirit

The access point

In order for the ritual to start and the “spirit” to be summoned, some kind of action from the user should be required. One idea that persisted for a long time was the idea of a touch on The Shrine itself. This interaction, for example with a LED candle, could be seen as an intimate and tranquil way of commencing the ritual. However, it came with more technical challenges than first anticipated. Capacitive sensing was explored thoroughly, but proved to be too unstable. The same was the case for using an LDR sensor. It was therefore regretfully decided to abandon interaction with mere touch. Instead, an older idea of a wireless access point in The Shrine was brought forward, which proved to have some very interesting perspectives in regards to symbolism (this will be discussed in the next session). To commence the ritual, the user connects their phone to the wifi emitted by The Shrine,

which then sets the rest of the ritual in motion. The network is not connected to the www, but in a further development of the project, it would be interesting to explore having a network for all the people currently using their shrines.

Welcoming gesture

Following the summoning of the spirit, it would only be fitting to bid it welcome. Gesture-based interactions are very common in how we communicate with technology today, so it would be interesting to explore this bodily mode of interaction in The Shrine too. Here, a Leap Motion controller, capable of reading hand movements, was prototyped with. Many gestures were experimented with, for example swipes and taps. However, these did not feel quite respectful enough. A sort of “rising” movement with the hand was then tried out, which evoked a more appropriate feeling of honoring.

However, despite of the use of machine learning to recognize the gesture, the gesture recognizing proved too unstable. A simple distance sensor was experimented with instead, and through a serendipitous encounter, the act of bowing in front of The Shrine was adopted as the welcoming gesture.

Figure 20. Sketching and prototyping with Leap Motion and distance sensor

Offerings

In rites of exchange and communion a form of sacrifice or offering is often seen. This was also a recurring element in the analysis in Section 6.2. Various ideas for offerings were contemplated; what would the internet spirit approve of? The donation of electricity was considered, either through blowing on a fan or plugging in a cord. Some smartphones have the ability to charge other devices, which would indeed be very symbolic. Taking some power from your own device and donating it to The Shrine. However, in the end, a more traditional offering was decided upon; water. In cultures across the world you see earthly gifts for the gods. Fruit, rice, wine, sweets, even cigarettes. Water then, could symbolize the act of co-creating the internet, a metaphor for contributing to the spring of