Multimedia Students:

Engaging across platforms

–

An Investigation of Student Engagement in the Media and

Communication Master Programme at Malmö University

by

Hanna Meyer zu Hörste & Joelle Vanderbeke

(15 ECTS credits)Master of Arts in Media and Communication Studies:

Culture, Collaborative Media, and the Creative Industries (Two-Year Master) Faculty of Culture and Society, School of Arts and Communication,

Malmö University, Malmö, Sweden Supervisor: Pille Pruulmann-Vengerfeldt

Examiner: Tobias Denskus Spring 2018

2

Abstract

This thesis investigates student engagement in the Media and Communication Programme at Malmö University through the lens of audience- as well as learning theories. It has two main aims: Building a systematized theoretical framework to distinguish different nuances of audience activity in a cross-mediatic learning environment, and exploring factors influencing student engagement in our Media and Communication Master Programme (MCS). Constructivist Grounded Theory (Charmaz 2006) with a multi-method approach for data collection is applied to gather rich data and analyse it accordingly through coding processes and constant comparison. Following social constructivism, it argues that each student, actively constructing knowledge, has her own subjective learning preference. This thesis takes a non-normative stand on the subject.

A matrix of audience activity, grounded in audience theories and developed through the collected data, is established. In a second step this is used to illustrate the concepts participation, engagement and collaboration and then further employed to examine factors influencing student engagement. Thereby, the matrix is tested, refined and further developed. Through this approach eight states a student might be situated in while studying as well as possible barriers for student engagement were identified. Factors influencing student engagement this study found are the personal situation of the student, the access Hyflex education allows, possibilities and challenges of physical and virtual learning spaces, the interaction between teachers and students, the structure of the programme and how students are connected with each other. By looking at student engagement in a media rich environment from an audience- as well as education-angle this thesis expands existing research. It presents influencing factors for student engagement. More importantly the theoretical model is a useful tool to investigate different kinds of student activities and to develop educational media tools. It could also be transferred to research other audiences.

Keywords: student engagement, HyFlex learning, cross-media learning, online learning, constructivist grounded theory, audience studies

3

Table of Content

1 INTRODUCTION 6

2 CONTEXT 8

2.1DISTANCE AND ONLINE LEARNING 8

2.2MEDIA AND COMMUNICATION MASTER PROGRAMME MALMÖ UNIVERSITY 9

3 GROUNDED THEORY 14

4 THEORIZING AUDIENCES 15

4.1STUDYING AUDIENCES 15

4.2ACTIVE AUDIENCES 16

4.3AUDIENCE PARTICIPATION WITHIN MEDIA STUDIES 17

4.4POSITIONING THE INVESTIGATION 18

5 METHODOLOGY 21

5.1DATA COLLECTION 21

5.1.1AUTOETHNOGRAPHY 22

5.1.2EXTANT AND ELICITED TEXTS 22

5.1.3INTERVIEWS 23

5.2DATA ANALYSIS 26

5.3RESEARCH QUALITY AND ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS 27

6 MATRIX OF STUDENT ACTIVITY & CENTRAL CONCEPTS 30

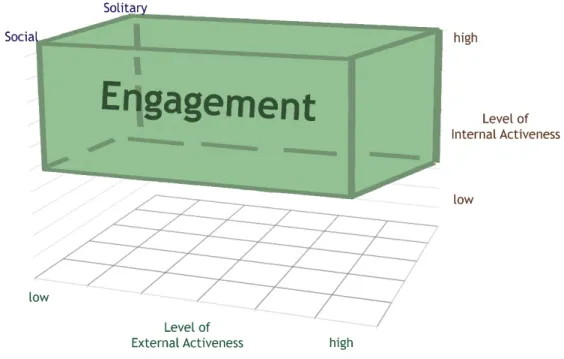

6.1.MATRIX OF STUDENT ACTIVITY 30

6.1.1DIMENSION A:INTERNAL ACTIVENESS 31

6.1.2DIMENSION B:EXTERNAL ACTIVENESS 32

6.1.3DIMENSION C:SOCIAL FACTOR OF ACTIONS 32

6.1.4CONNECTIONS TO THE PREVIOUS MODEL 33

6.1.5THE PURPOSE OF LEARNING 34

6.1.6THE CONNECTIONS BETWEEN THE THREE DIMENSIONS 35

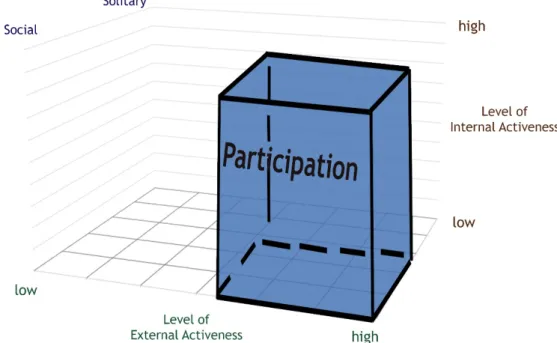

6.2SITUATING CONCEPTS IN THE MATRIX 37

6.2.1STUDENT PARTICIPATION 37

6.2.2STUDENT ENGAGEMENT 40

6.2.3COLLABORATION 45

7 FACTORS INFLUENCING STUDENT ENGAGEMENT IN THE MASTER PROGRAMME 49 7.1PERSONAL SITUATION 49 7.1.1MOTIVATION 49 7.1.2PRIORITIES 50 7.1.3PREFERENCES 51 7.2ACCESS 52 7.2.1DIVERSITY 52

4

7.2.2FURTHER ADVANTAGES OF ONLINE LEARNING 53

7.2.3ACCESS VS.STUDENT ENGAGEMENT 53

7.3PHYSICAL AND VIRTUAL SPACES 54

7.4STUDENT AND TEACHER INTERACTIONS 58

7.5BARRIERS 61

7.5.1THE TECHNICAL BARRIER 61

7.5.2THE EXPRESSIVE BARRIER 63

7.5.3THE STRUCTURAL BARRIER 66

7.6COMMUNITY 68

8 STATES OF STUDENT ACTIVITY 72

9 DISCUSSION 76 10 CONCLUSION 79 BIBLIOGRAPHY 80 DATA 90 OTHER SOURCES 92 APPENDIX 93

1. AUTOETHNOGRAPHIC-ESSAY HANNA MEYER ZU HÖRSTE 93

2. AUTOETHNOGRAPHIC-ESSAY JOELLE VANDERBEKE 97

3. ESSAY GUIDELINES FOR STUDENTS 101

4. INTERVIEW GUIDELINES 103

5. INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPTS 107

6. CODING CATEGORIES 200

5

List of Figures and Tables

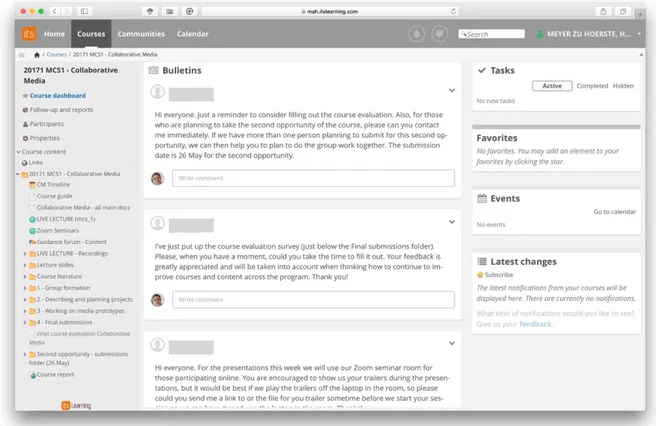

Figure 1: Screenshot of Online Platform Itslearning 10

Figure 2 & 3: Pictures of the Glocal Classroom 11

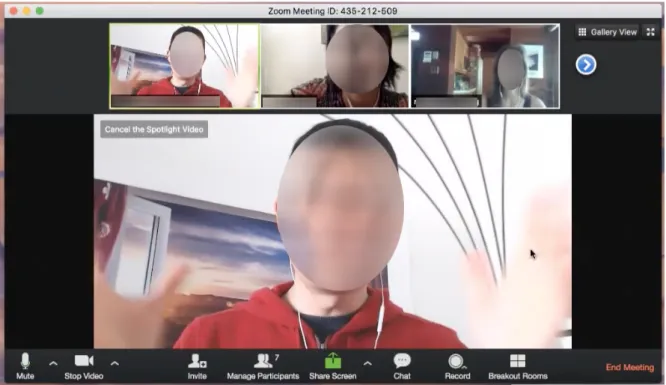

Figure 4 & 5: Screenshot of Live-Lecture 12

Figure 6: Screenshot Zoom Videoconference (Kao 2017) 13

Figure 7: Situating our Research with References to Audience Research 20

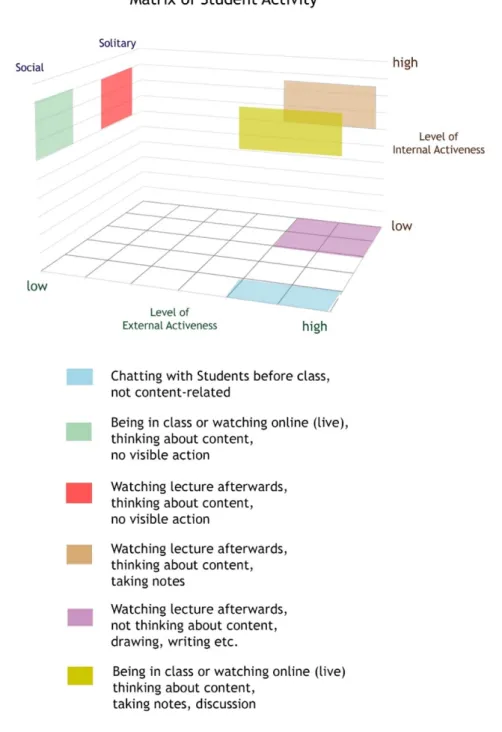

Figure 8: Matrix of Student Activity 31

Figure 9: Matrix of Student Activity combined with Livingstone (2004) 34 Figure 10: Matrix of Student Activity with possible student actions 36

Figure 11: Matrix of Student Activity / Participation 38

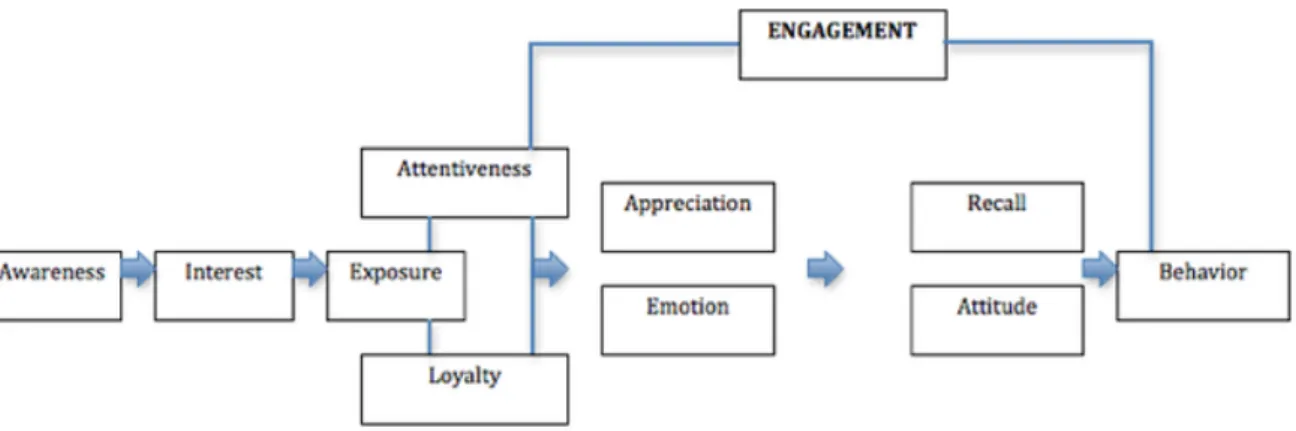

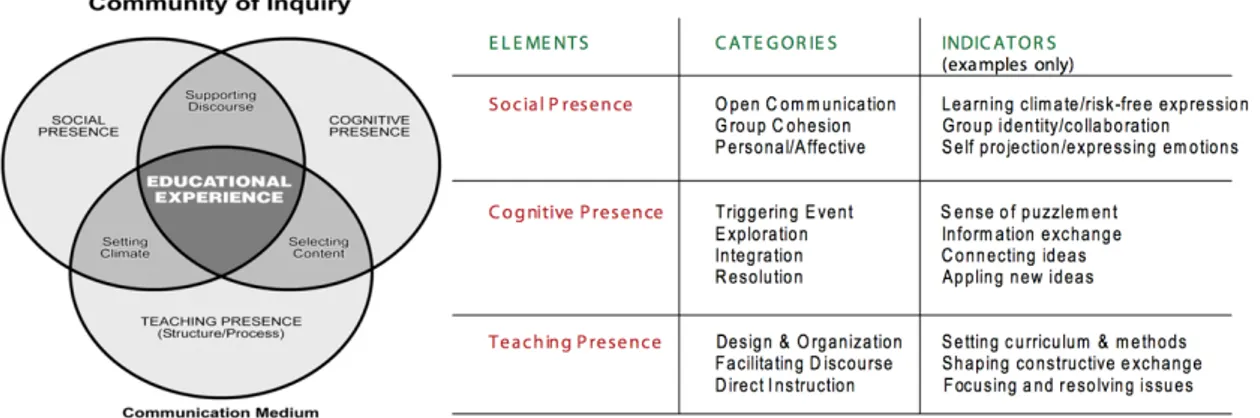

Figure 12: Audience Dimensions (Napoli 2012, p.86) 41

Figure 13 & 14: Community of Inquiry framework 42

Figure 15: Matrix of Student Activity / Engagement 43

Figure 16: Matrix of Student Activity / Collaboration 48

Figure 17: Matrix of Student Activity / Technical Barrier 63 Figure 18: Matrix of Student Activity / Expressive Barrier 65 Figure 19: Matrix of Student Activity / Structural Barrier 68 Figure 20: Matrix of Student Activity / Key Community Actors 71 Figure 21: Matrix of Student Activity / States of Student Activity 73 Figure 22: Matrix of Student Activity / Comparison Concepts & States of Activity 75

Table 1: Summary of collected Data 25

6

1 Introduction

Two years ago, both of us started studying the Media and Communication Master Programme at Malmö University. This programme makes use of a variety of media tools and the lectures are broadcasted live, recorded and uploaded for on-demand watching. This enables three different modes of study: on-campus, online synchronous and asynchronous. One of us moved to Sweden from the beginning, started on-campus but drifted more and more into studying online. The other stayed in Hamburg during the first year and then moved to Malmö to attend most courses on-campus. Both of us, on our own terms, discovered how many different students are brought together by the programme and how it is situated in different media spaces. Processes of globalisation as well as new technological possibilities have influenced the educational landscape, our course being a great example of this development. Through digital technologies, students from all over the world are able to attend courses and interact with peers and teachers. The cross-mediatic approach1 of the programme and the many possibilities this offers to students interested us from the beginning. Following this curiosity, we started a research project about influences this educational environment and its media tools had on students. Hereby, we approach student engagement from an audience reception studies’ angle, where students are treated as audiences. Students in this programme are „thinking across media platforms” (Jenkins 2010, p. 943) and are interacting with each other through a variety of online tools. Through the three different study modes, the programme also has three different audiences of learning media: a classic on-campus audience watching the lecture unmediated but being filmed, a live online audience watching the lecture remotely and an on-demand online audience, independent of space and time. The modes are not fixed hence students can switch back and forth between them. One of audience researcher’s key questions is how the audience engages with media content (ibid, p.944). In this thesis, we want to investigate how students of the different study modes engage with the course content and each other in the cross-mediatic learning environment.

Still, to research student engagement in-depth and to gain a broader perspective, our investigation also includes learning theories. Since audience reception studies are seeing the audience as actively creating meaning and are thus grounded in social constructivism, we will be using learning theories in the same paradigm, where the focus is on knowledge construction of the learner. Meyer (2015) also notes that „constructivism is dependent upon engagement,

1 Cross-media describes „integrated experiences across multiple media” (Davidson 2010, p. 6) and often

7

and perhaps all engagement research implies a belief in constructivist learning theory” (p.26). We consider the student as audience who is actively involved in meaning-making processes through interaction between herself and her environment (Collins 2010). With this audience and education research approach we are following suggestions of more interdisciplinarity within audience studies (Livingstone & Das 2009).

Methodologically, this study is based on the constructivist approach to grounded theory (Charmaz 2006), which assumes that theories are not merely discovered but also constructed by interactions and relations between researcher(s) and the participants and the field. Consequently, the overarching theme of the thesis and the research paradigm we will follow is

social constructivism.

The aims of our thesis are twofold, theoretical and empirical. Firstly, we will use grounded theory to distinguish different nuances of audience activity and build a systematized theoretical framework. Our empirical aim is to use this framework – a matrix of student activity – to explore factors that influence student engagement in our media and communication Master Programme. The research questions we want to answer are:

1. How can nuances of audience activity in a learning environment be systematized in a theoretical model?

2. How is student engagement in the cross-mediatic learning environment of the Media and Communication Master Programme at Malmö University influenced?

This paper will not take a normative stand on student engagement. Meaning is constructed individually by each learner and subjective. Just as audience reception researchers do not want to investigate the effectiveness of media, we don’t want to research the effectiveness of learning nor compare successes in online or on-campus learning. We also want to note that this research project is by no means meant to criticize the Master Programme or its teachers. It is rather a possibility to work on a practical project that is hopefully not just relevant to us.

As we are employing grounded theory, this thesis will follow a somewhat untypical structure. Firstly, it will look at the context of online learning and introduce our media-rich Master Programme. Following this, our usage of grounded theory is explained. Chapter 4 presents audience theories positions our theoretical investigation. Afterwards, our methodology, containing a multi-method approach to data collection and initial as well as focussed coding, is explained. A focussed literature review (Charmaz 2006) was performed, which is integrated in the following chapters. Chapter 6 documents our developed matrix of student activity, explains

8

the dimensions and their relations and further situates key concepts, namely participation, engagement and collaboration, within the matrix. Afterwards, we turn to the empirical research question and examine factors that influence student engagement in the Master programme. Here, our matrix is used to explain relations between influencing factors and the afore situated concepts. In chapter 8 we will advance our matrix through the analysis of our empirical data and further connect our findings to previous media and education research. These sections will be completed with a discussion of the relevance of our model for further research and ends with a discussion of the paper’s limitations. Lastly, our key findings will be reviewed in the conclusion.

2 Context

2.1 Distance and online learning

Providing a background for our study we will start out by clarifying important terms, provide information on online and HyFlex learning and about the Media and Communication Master Program of Malmö University.

Distance education can be described as teaching and learning, where students and teachers are

separated by space and/or time. It originated in the early 18th century and evolved through five generations: correspondence study, learning through broadcast radio & television, Open Universities (integration of audio/video and correspondence), interactive teleconferencing and computer and internet-based courses. (Moore & Kearsley, 2004). Distance student’s enrolments have been growing steadily over the last decade. 2

Online learning (also called e-learning) is a form of distance education which is completely

delivered via the internet. Students and teachers are not required to be at the same place and if studied asynchronous also not at the same time. (Siemens et al. 2015)

Blended or hybrid learning refers to a combination of traditional face-to-face teaching with

online learning. Students and teachers have to be at the same place for a certain amount of time (Siemens et al 2015).

2 In the USA over thirty percent of higher education students are taking at least one distance education course.

9

HyFlex (hybrid and flexible) learning combines online and face-to-face learning and teaching,

and students can choose whether to attend online or on-campus. HyFlex Programmes involve diverse media technologies to combine both approaches. (Beatty 2013, Leijon & Lundgren 2016).

Our Master Programme belongs to the latter category. Since this type of studies is not widespread and under-researched we will review literature and theories on synchronous and asynchronous online learning. In comparison to traditional distance education, which was focused on autonomy and instruction based, online learning is a turning point enabling interaction between students and teachers (Garrison 2011).

2.2 Media and Communication Master Programme Malmö University

The Media and Communication Studies: Culture, Collaborative Media, and Creative Industries, Master Programme (MCS) at Malmö University (MAU) was launched autumn 2015 and can be studied as one- (60 credits) or two-year (120 credits) option. It was based on the pedagogical and technological model of the Communication for Development (ComDev) Programme at MAU (Krona). MCS aims to advance the students’ theoretical knowledge and practical skillsets in new media landscapes. The main focus lies on the impartation of a strategic expertise, the ability to work methodologically and systematically and to produce media texts (Homepages MCS n.d). Students are encouraged to study synchronous – live – but lectures are recorded and can therefore be watched at the student’s convenience, which is especially important in regard to time differences and work life. Hence, this approach combines off- and online students from around the world in one cohort, which presents challenges and benefits at the same time. This way of teaching is implemented through different means of infrastructure, which will be explained in the following.

1. Online Platform Itslearning

The programme - as well as other programmes at MAU - is structured and hosted through a learning management system (LMS). Each course has its own page where schedules, teaching materials as well as student assignments and projects are uploaded. It is also the major communication tool for teachers and students with different possibilities to communicate with each other. Teachers can give updates to the whole cohort on the dashboard of the course page, students can ask questions as comments or in the course forums, additionally direct messages

10

can be written. During the time of our study, the platform Itslearning was used, but from autumn 2018 it will change to Canvas.

Figure 1: Screenshot of Online Platform Itslearning

2. Glocal Classroom and Live Lecture

Lectures are usually held in the Glocal Classroom situated at MAU3. The term glocal originates from the words global and local, which are both present in the room. Local because students and teachers can meet here locally and global because this classroom works similar to a TV studio, where lectures are recorded and broadcasted live for online students, no matter where they are situated. To screen the lectures and connect online students a self-designed (thelocal.se, 2017 & Rundberg) platform called Live-Lecture is used. It consists of a video screen, a chat function and a list of the people that are watching live. This way, online students can see and hear what is happening in the classroom, follow the lectures, participate via chat or talk to other students. In the classroom the chat is shown on a to the teachers, who can read and react to questions and comments. To manage Live-Lecture, a facilitator is present next to the teacher.

3 It is named Glocal „[...] to distinguish it from the many Global Classroom projects around the world, but

mostly because the glocal is a more adapt term to characterize the process of globalization, which has made the global-local dichotomy irrelevant”. (Hemer n.d.)

11

The lectures are filmed with three cameras with different angles, which makes it possible to not only show the teacher but the whole room with attending students as well. A green-screen ist used to be able to morph the teacher into the lecture slides or combine teacher and students in one frame. Each lecture is recorded and available online on the platform Bambuser for on-demand watching or review. However this approach and the Glocal Classroom are not new creations for the MCS. They have been used, tested and improved for 15 years in MAU’s ComDev Master Program (Rundberg). The room and equipment are shared by various programmes of the faculty. Since Bambuser is limiting their service, it will not be possible to use Live-Lecture shortly. Instead Zoom Webinar will be used as software from autumn 2018.

12 Figure 4 & 5: Screenshots of Live-Lecture

13 3. Zoom Videoconference & Skype

For seminars in smaller groups, feedback sessions, supervision and presentations Skype was used first, but quickly changed to a conference software called Zoom4. In Zoom, every

participant has the possibility to take part with camera and audio. Additionally, everyone’s screen can be shared, and a chat is available. The default interface shows a stripe of all attendees, the one who is talking on a larger central screen. This virtual setup enables teachers and students to talk and listen to all of the participants „face-to-face” and to have direct discussions.

Figure 6: Screenshot zoom videoconference (Kao 2017)

4. Student Facebook group and other tools

At the beginning of the program the students were encouraged to form their own facebook group to connect and communicate with each other. This recommendation came from good experiences of the former cohort. During the course of the studies the students are encouraged to use further communication and collaboration tools like Slack, Trello etc.

4 Zoom Videoconference and Zoom Webinar are different tools for different purposes and should not be

14

3 Grounded Theory

This thesis will investigate the concept of audience engagement and develop a model which will add to its theoretical understanding. Grounded theory based on Charmaz (2006) school is the overarching research approach. A defining component of grounded theory is to advance theory building in each step of data collection and analysis and to challenge the division between theory and empirical research (Charmaz 2006, p.5f.), which is reflected in our research design and process.

The initial method of grounded theory stems from Glaser and Strauss’ work (1965, 1967) and was followed by disputes between Strauss and his Co-writer Corbin (Corbin and Strauss 1990) and Glaser (1992) over the degree of formalisation in the research process. The decision to use constructivist grounded theory was made, because it takes in critique about positivist assumption within grounded theory (Charmaz 2006, p.9) and describes the researcher as a co-constructor of meaning. We „construct our grounded theories through our past and present involvements and interactions with people, perspectives, and research practices” (ibid, p.10). This notion of Charmaz’ work is especially important with regard to our involvement in the studied field – our Master programme – and our autoethnographic starting point. Furthermore, we appreciate Charmaz’ systematic but flexible guidelines for data collection and coding and still staying open for constant comparison.

Another essential principle of grounded theory is the parallel collection and analysis of data (ibid, p.5), as well as the data driven, abductive theory formation. For this reason, this thesis will not follow a traditional structure, where data collection, results and analysis follow theoretical examinations and literature review. Contrarily, we give a short theoretical overview to acknowledge basic concepts in audience research. In combination with the interests derived from observations, these sensitizing concepts were used as points of departure for data collection and analysis (ibid, p.17). To remain as open-minded as possible, we chose to focus first on collecting and analysing data and only then proceeded to review literature and further theoretical concepts to include in our comparative analysis. Hence, the paper’s structure reflects our research design and emphasises the development of our understanding of audience engagement through our data (Gibbs 2013).

15

4 Theorizing Audiences

Audience engagement itself is seldom theorized within the field of media and communication. Thus, this chapter will look at the starting point of engagement: active audiences. Due to a changing, decentralised media sphere, the idea of an active audiences is intertwined with the concept of participation. In the history of audience studies, especially the traditions of political theory, participation is linked to the concepts of power and decision-making (Carpentier 2016). To be able to integrate the term into our systematization of audience engagement we will use the term predominantly without a political dimension.

4.1 Studying Audiences

McQuail (1997) suggests defining audiences as „those who are reached by (or brought into contact with) a given communication medium“ (ibid, p.148). Communication medium is defined as „any organizational form or device that is designed to facilitate the giving, taking, sharing, exchanging, or storing of meaning“ (ibid). In the MCS, students engage with content through a variety of different media, which they actively use to facilitate meaning-making. Also, within the cross-mediatic landscape, they are interacting with each other and the teachers in various ways. This thesis does not focus on producing one overarching definition for audiences. Instead, it agrees with Livingstone (1998b), who concludes that how audiences are defined is not the prevalent question, but rather how they relate and interact with different forms of media (ibid, p.251).

Within the scope of this thesis project, we will investigate audiences at the micro level. Grand theories about mass media and the democratization of the public will be excluded from this paper. Instead, we will look at audiences in a sense that suggests some form of group identity, using the notion of „audience as community” (Carpentier 2011a, p.71). Avoiding the risk of describing audiences as just one entity, our research is in line with „the articulation of audiences as social, virtual and interpretative communities“ (ibid, p.72). This definition also describes the students in the MCS, which we will investigate. Furthermore, active meaning-making processes that are central for audience reception studies are a focus point of a variety of educational theories. Thus, learning and audience theories relate and allow us to apply insights from audience studies to student engagement.

16

4.2 Active Audiences

When talking about engagement, audience activity is essential. But the audience was not always seen as active in audience studies. There is a long history of modelling audiences as passive receivers in a one-way communication. The first researchers to approach „the human subject as an active carrier of meaning” (Carpentier 2011b, p.519) were Eco (1979 [1972]) with his aberrant decoding theory, Hall’s (1980) encoding/decoding model and – elaborating on Hall – Fiske’s (1987) concept of the active, interpreting audience that negotiates meaning. Another model relying on the concept of the active audience is Katz et al.’s (1974) theory of uses and gratifications, which describes how media is sought out by an audience that wants to achieve certain gratification. Wherein the former concepts refer to audience engagement in the sense of meaning-making, interpretation and or contextualization the latter examines the questions of how and why audiences engage with media - both central questions when researching student audiences.

Looking at more recent research on active audiences we turn to Sonia Livingstone. Her research started by exploring television audiences (1990) and she is recently investigating audiences within the „increasing mediation and digitalization of all dimensions of modern societies“ (2015, p.439). Studying television audience receptions, Livingstone (2004) emphasises the role of the audience in the meaning-making process:

[…] [a]udiences work to make sense of media content before, during and after viewing, they are themselves heterogeneous in their interpretations, even, at times, resistant to the dominant meanings encoded into a text. Viewers’ interpretations diverge depending on the symbolic resources associated with their socioeconomic position, gender, ethnicity and so forth […]. In short, engaging with symbolic texts rests on a range of analytic competencies, social practices and material circumstances. (p.79)

Livingstone and Das (2009) raise the question if people’s engagement with today’s media environment can be analysed through the conceptual frameworks developed by former audience studies (p.4). They argue that „in relation to people’s engagement with media and, more importantly, in relation to people’s engagement with each other through media, the changes are indeed noteworthy […]” (ibid), but that this does not mean that new frameworks must be used. Consequently, they emphasise how the key insights of audience reception studies still address the overall concerns of media studies:

1. Meaning, there is no singular underlying meaning of media texts as audiences' readings and receptions cannot be predicted from the media text alone (even if the text cannot be disregarded in meaning-making processes),

17

2. Context, as the audiences' readings are diverse and based on interpretations situated in a specific, structuring social context and

3. Agency, as audiences' everyday practices also „reshape and remediate media texts and technologies […], challenging top-down, often universalising accounts of diffusion and effects.” (ibid.)

The significance of these insights for learning audiences and student engagement will be picked up and discussed throughout this thesis.

Accompanying the debate surrounding the relevance of audience studies in the new media landscape is the question, if the concept „audience”, even if active, should make way for the 'modern' and highly participating 'user' or even 'produser' (Bruns 2008). Of course, the availability of new technologies with an increased possibility of interaction is a novelty that facilitates a new audience autonomy. The word 'user' gained popularity „because of its capacity to emphasize online audience activity, where people were seen to ‘use’ media technologies and content more actively“ (Carpentier 2011b, p.524). In fact, the 'active user' often seems to outshine the, in comparison, 'passive audience' (Livingstone 2013, p.3). Even if this thesis does not wish to undermine the need of concepts to describe transformed relations between humans and media environments, it complies with the critique against allegations of completely unique and unfamiliar 'audiencing' practices through new technologies (Carpentier 2011b, p.517). It follows Carpentier’s (2011b) and Livingstone’s (2015) call to a rediscovery of audience theories to investigate today’s media use. The paper will investigate several layers of audience activity and engagement sticking to the term 'audiences' instead of 'user'.

4.3 Audience Participation within Media Studies

Audiences are becoming more participatory (Livingstone 2013, p.23) and a growing interest among audience researchers is how participation is enabled. New media, especially social media, adds new dimensions of self-representation, as well as content-related and structural participation. Thus, Livingstone suggests the emergence of a participation paradigm in audience studies (ibid, p.21). Her approach in defining participation is through the word participate: (actively) taking part in something (ibid, p.24). She is concerned with the question of what the

audience is taking part in, though, implying the social role of a participatory audience that takes

18

When looking at audience participation, major works stem from Nico Carpentier, who wrote excessively about this concept with a focus on processes of democratization in society (2011b). He addresses the issue that „there is hardly a consensus on how participation should be theorised, or even defined” (2016, p.70). To establish more clarity in academic dialogues, he distinguishes two main approaches of participation: a sociological and a political. The sociological approach is more extensive than the political and describes participation similarly to Livingstone’s initial definition: „taking part in particular social processes” (ibid, p.71). It thus includes a vast variety of interactions with humans, text and technologies. Melucci (1989) points out participation’s double meaning: „It means both taking part, that is, acting so as to promote the interests and the needs of an actor as well as belonging to a system, identifying with the ‘general interests’ of the community” (p.174). Because of its broad definition and use in different fields (e.g. sports, culture, education), participation in sociology does not have a singular meaning. In contrast to the political approach, which is deeply rooted in theories concerning the emergence and maintenance of power structures in decision-making processes (Carpentier 2016), the sociological approach is more pragmatic and free of normative connotations (Schäfer in Allen et. al. 2014, p.1141). Carpentier (2016) who follows the political approach, notes that because of its more restrictive use of the term ‘participation’, there is also a better demarcation towards other related concepts like engagement. He further criticises that in the sociological approach those related concepts are often used interchangeably.

Since our field of research is the learning environment of our Master programme, which is more of sociological nature than political, we find the broader sociological approach to participation more suitable for our further investigation. Moreover, we want to dissociate ourselves from any normative notions. The differentiation of concepts related to engagement, including participation, will be a major part of our thesis. Hence, we will elaborate further on different notions and uses of participation later on. In the following chapter we continue our investigation with a first systematisation of above mentioned relevant concepts.

4.4 Positioning the Investigation

Even though different degrees and forms of audience activity are discussed within audience research, this thesis wants to contribute to a more detailed systematisation. Livingstone and Das (2009) specify that there is an urgent need for theorizing how people engage with, now also participatory, media texts (ibid, p.4) and that „meaning, agency, resistance, participation, conversation, interaction, and many others are still the pressing concern of new media

19

researchers“ (ibid, p.3). Furthermore, Livingstone (1998) suggested a higher specificity in audience research (ibid, p.247). Where participation is often used as a vague description for all kinds of audience activity, our model inspired by empirical investigation aims to highlight the nuances between degrees of activeness, engagement, participation and other related concepts. It will not take a normative stand on engagement or participation and avoid „the trap that being active is always best for the audience” (Höijer 1999, p.191).

The thesis is grounded in Livingstone’s and Das’ (2009) thoughts about audience activity. Also, closely related is the concept of participation, which will be applied here through the sociological approach. Furthermore, Carpentier’s work (2011a & 2011b) will be contemplated, since his research and especially the „Participatory dimensions of audience activity”-model with the three dimensions participation in media production, participation in society through

the media and interaction with media content (ibid, p.70) is seminal in audience research.

However, his focus on participation as a democratic process to change society marks the endpoint of our investigation; these processes are not our focus within the learning environment. We are interested in the intermediated stages between a ‘passive’ and active audience with regard to engagement, which are not yet covered and systematized.

The central concept of our initial model are Livingstone’s and Das’ (2009) three key insights, which are tied to audience engagement: meaning, context and agency. When engaging with media and its content the student audience actively creates meaning, for instance, when making sense of course literature. Through a greater or lesser degree of engagement with others, the students then contextualize and update the meaning, a key principle in constructivism (Dewey 1908). Through reshaping and remediating media texts the students engage actively and might also take part in their community. Students are influencing other students, e.g by discussing and expressing their thoughts on the literature. Thereby the degree of ‘socialness’ increases going from active to participatory (Livingstone 2013). From actively reading by themselves, to actively listening to a teacher and to finally expressing their thoughts in a discussion with other students. The programme community thus can be seen as the system the students are belonging to, as described by Melucci (1989).

20

Figure 7: Situating our Research with References to Audience Research

Additionally, we decided to include the dimension of a passive audience in this first draft, even though it was argued against by Livingstone (2013, p.24f.). Referring to the notion of 'audiencing' (Fiske 1992) in a mediatized world, being an audience at all times (Livingstone & Das 2009), a continuous active engagement with all media content seems impossible. This leads to the assumption that passive moments without textual interpretations indeed occur, especially at the simultaneous consumption of more than one media output. An example is the usage of a second screen (e.g. mobile phone) while watching television. Especially in the online learning environment, which we want to investigate, this notion seems crucial.

We are aware, that our initial model draft is a simplified illustration of student activities. However, it serves as a good starting point and connection of audience and student engagement. In the following we will focus on our collected data and examine this model further. Subsequently we will also include theoretical works from other fields in our investigation (see chapter 6).

Active Audience Participatory Audience

Pa ss iv e Aud ience

solitary actions increasing social factor in actions

community / group actions

interaction with (media) content

interaction with

others (through media)

Meaning Context Agency

Livingstone (2013)

Livingstone & Das (2009) Melucci (1989) Carpentier (2016) Active Audience Sociological Participation Concepts:

21

5 Methodology

In this master thesis we will follow an empirical approach and use grounded theory to develop a better understanding of audience engagement. In our research design, we did not follow the linear structure of data collection and analysis this chapter indicates. The collection, coding and analysis of data happened simultaneously and cyclically. Thus, we were able to modify our data gathering through adapting questions, our choice of interview partners and the inclusion of newly occurring themes (Gibbs 2013). Putting emphasis on the comparative method, we compared data with data, data with emerging categories and categories with concepts (Charmaz 2006, p.23). However, to ease the readability, we chose to present our methodology in a structure that is more recognized in a traditional research context.

We achieved triangulation concerning our data collection, which combines interviews, written evaluations and student essays with an autoethnographic approach as a starting point of the research. Thus, a fuller picture of different viewpoints and facets of various actors (Denscombe 2010, p. 345ff) within the context of the master programme was considered. This chapter closes with considerations regarding the quality as well as ethics of our research.

5.1 Data Collection

Following a qualitative research design, the collected data consists of two autoethnographic essays from the researchers, eleven student essays with five complimentary student interviews, six expert interviews and the anonymous course feedback of eight courses. According to Flick (2007), qualitative research does not attempt to reduce complexity, but to illustrate it in the specific research area (ibid, p.124). Charmaz (2006) highlights the importance of gathering „sufficient data to fit your task and to give you as full a picture of the topic as possible within the parameters of this task“ (p.18). Where in qualitative research saturation is commonly seen as reached by reoccurring themes and patterns, saturation in theoretical sampling is reached when „gathering fresh data no longer sparks new theoretical insights, nor reveals new properties of your core theoretical categories” (p.113). Since the aim of this thesis is two-fold, theoretical and empirical, we made sure to reach both saturation points with our sample.

22

5.1.1 Autoethnography

According to Charmaz (2006) all grounded theory starts with data (p.3). Furthermore, qualitative data is often joined with ethnographic data. Since the idea for this research project came from our experiences and observations from almost two years of studying in the programme, we found autoethnographic data to be a good starting point for our inquiry. To channel our thoughts and perceptions, each of us wrote an essay (Appendix 1 & 2). Ricci (2003) describes autoethnography to be more about „discovering“ than „telling“ (p.590). He sees this method as „the practice of attempting to discover the culture of self, or of others through self“ (p.593) and illustrates how researchers cannot „write about 'other' without revealing something about 'self'„ (p.595). Following in the footsteps of Ricci, our essays were written and used to identify our own point of view and experience on engagement in MCS and served as a point of departure to explore other viewpoints and experiences. Another reason to open the research process with our own essays was being able to capture our perspective unbiased of other collected material. This subjectivity is seen as autoethnography’s strong limitation. However, this can also be regarded as this method’s strength, as it challenges the positivist stance of one objective reality or truth that needs to be uncovered and rather takes in the notion of multiple, local realities and self-reflectivity (p.593ff.). In our text, we treated our essays as we treated other data; references and direct quotes can be found.

5.1.2 Extant and Elicited Texts

To achieve a rich data collection (Charmaz 2006, p.13), we combined these autoethnographic essays with other methods of data collection. Both, extant (researchers did not affect their construction) as well as elicited texts (grounded in guidelines constructed by the researchers) (p.36f.) were used in our investigation. Extant texts were provided through an access to the anonymous course feedback given by students on a voluntary basis via the platform Itslearning after each completed course (available upon request). The surveys are created by the course lecturers to gather evaluations, opinions and detect possibilities for improvement. We collected feedback surveys throughout eight different courses and all three cohorts the programme had so far. These surveys provided an independent and supplementary source of data to further research materials (p.38). Moreover, the research literature we used throughout our project can also be considered extant texts, as Glaser (2002) and Charmaz (2006) express: „All is data”.

23

Furthermore, students of the programme were asked to produce essays. Given the opportunity to follow the researchers guidelines (Appendix 3) or to write freely, eleven students reflected on their experiences with the programme related to engagement (available upon request). We ensured that a wide range of people with different perspectives were included: students, male-female, online and on-campus, from all three years (Denscombe 2010, p.35). This paper does not attempt a representation of the whole population participating in the master programme, , we rather strived for diverse perspectives. However, due to our own involvement in the programme and relationships to other students, we gathered more data from female, second year, on-campus students than from any other group.

Through this practice we gathered accounts that do not only represent our point of view, but also include other beliefs and realities (Collins 2011, p.142). The stories we identified in essays and feedback brought in personal experience that differs from ours. We recognise that the texts do not stand as objective knowledge or facts, but as part of the research and constructed through participants and the guidelines. When analysing, we kept in mind the context in which the texts were produced and for whose eyes they were intended (Charmaz 2006 p.37). The hierarchy between lecturers and students, for instance, could have influenced the course feedback, even if anonymous. Also, the students who authored essays might have not given a full account of their experiences of the programme and possible critique (ibid, p.36), as we asked them in a non-anonymous setting.

5.1.3 Interviews

The essays were complemented with five5 semi-structured student interviews to gather more focussed data. The group of interviewed students consisted of both, those who handed in essays before and newly contacted persons. Participants were asked clarifying questions about their essays but newly discovered topics in our research were discussed as well. To allow our interview-partners to talk freely while also focussing the conversation on our research, we drafted open-ended interview guides (Appendix 4) for each participant. The guidelines were adapted according to the development of the interview, while still ensuring that most of our questions and topics were covered. We paid attention to create open ended, non-judgemental and non-leading questions, on „guard against forcing interview data into preconceived categories“ (Charmaz 2006, p.32).

24

In addition, six expert interviews with lecturers and technical staff of MCS were conducted. This gave us the opportunity to explore questions on student engagement from another important perspective and compare it to a students’ point of view. Expert interviews were conducted with Prof. Bo Reimer and Michael Krona, both founders of the programme and teaching staff from the beginning. These voices were especially interesting when exploring the motivations and thoughts behind the programme. Other interviews were held with lecturers Erin Cory and Jakob Svensson, who started working with the programme in 2017. Through them we gained insights about experiences as lecturers in a cross-media learning environment. Since this is based and depended on the use of various technologies (recording and livestreaming of the lectures with Live Lecture or Zoom etc.), we also wanted to explore this component further. Consequently, we included interviews with Mikael Rundberg, interaction designer and e-learning consultant responsible for the technical set-up of the course, and Daniel Strömgren, a technical assistant.

All in all, we included opinions of 14 students (ourselves excluded), 6 teachers and the course feedback. The total sample of our work is summarised in the following table 1. Since we knew that our sample would be relatively small for reasons of feasibility, we chose our participants according to their relevance, knowledge and experience of our topic. It must be noted that the data collection was conducted over a longer period of time. Our autoethnographic-essays were the starting point6, followed by the course feedback which we received in February. The student essays were send to us in the beginning of April. From that point on also interviews were conducted until the end of the month. While we were analysing previously collected data, we focussed and refined our research interest. Therefore, the choice of interview partners as well as the range of interview topics were adjusted accordingly at each stage of the process to gather more specific data: „The grounded theory approach of simultaneous data collection and analysis helps us to keep pursuing these emphases as we shape our data collection to inform our emerging analysis“ (Charmaz 2006 p.20).

25 Table 1: Summary of collected Data

Student1

former 3rd year student,

studied on- and offline 9th April 2018

Oral Interview Essay

Student2

2nd year student, on- and

offline 10th April 2018

Skype Interview, Essay

Student3 2nd year student, offline 16th April

Oral Interview, Essay

Student4 2nd year student, offline 16th April Oral Interview Student5

3rd year student, on- and

offline 18th April Oral Interview

Student6 2nd year student, online 21st April Skype Interview

Student7 1st year student, online Apr 18 Essay

Student8

former 2nd year student,

online Apr 18 Essay

Student9

2nd year student, on- and

offline Apr 18 Essay

Student10 1st year student, offline Apr 18 Essay Student11

former 2nd year student,

studied on- and offline Apr 18 Essay Student12 2nd year student, online Apr 18 Essay Student13

2nd year student, on- and

offline Apr 18 Essay

26

5.2 Data Analysis

To analyse our data, we started with qualitative coding, constantly comparing data with data and concepts, reaching higher levels of abstraction directly from the data (Charmaz 2006, p.3, Appendix 6). We used two types of coding found in grounded theory: initial line-by-line and focussed coding (ibid, p.11). During the whole research process, we engaged in memo-writing to „elaborate categories, specify their properties, define relationships between categories, and identify gaps“ (ibid, p.5). This helped us to develop and share our ideas, as both researchers had access to each other’s memos.

27

In our initial line-by-line coding, which is a nuanced investigation modelled closely along the data (ibid, p.50), we remained open-minded to possible theoretical directions our data was leading us (ibid, p.47). This coding is highlighted as especially fitting for identifying gaps in collected data which further interviews can be based upon (ibid, p.50). The codes we identified in this initial coding had an extensive range. Therefore, a phase of focussed coding followed, where our initial codes served as a basis to analytically categorize and condense our data (ibid, p.57ff). After developing the first focussed codes they were compared to data and other codes and further refined (ibid, p.59f.). As well as the data collection, coding was not a linear process. We rather went back and forth between data sets and categories and adapted further data gathering (ibid, p.46). Using the constant comparative method (ibid, p.54), we compared our own experiences and essays with the student feedback and other student essays. Subsequently the essays were compared with follow-up interviews and interviews with new participants. The interviews were further compared with expert interviews and, again, arising concepts with newly but also previously collected data.

As some of the concepts we explored in this thesis, like engagement, participation and interaction, are charged with underlying assumptions from our participants, we referred to them as in vivo codes (ibid, p.55). During the coding phase, we tried to stick closely to the actions our participants described and not to get lost in the big concepts we wish to investigate. These codes were useful to decipher underlying meanings in their usage, as everybody knows these words, but their definition differs among participants.

5.3 Research Quality and Ethical Considerations

Ethical considerations in this paper concern the anonymity of our student research participants as well as their representation in our study. Since our programme consists of a manageable number of students who are in contact with each other and the lecturers, we paid attention to anonymise their accounts. Due to the existing hierarchy between lecturers/examiners and students, this thesis must guarantee that the participants insights and opinions do not have any damaging effects on their future studies. Our sample consists of three consecutive years of students, so it is broadened, and the possible recognition minimized. Still, to add another degree of anonymity, the essays as well as student interview-transcripts are not included in the appendix. To ensure transparency for readers of our thesis, they are available upon request. Also, the anonymous course feedback will not be quoted directly but mediated through the researchers, as the participants did not agree to appear in a research context or knew

28

they ever would. The surveys are also available upon request. Ethical considerations regarding the usage of interview material from the expert interviews are limited, since all our interviewees gave their verbal consent to be interviewed and to appear in this thesis by name. However, their accounts could have an influence later on that they were unaware of at the time. All our participants are mediated through us, the researchers. We see this thesis as an interesting research project with the opportunity for constructive feedback towards our programme, rather than criticism. Our overarching aim is the development of a non-normative model that allows for a systematisation of audience activity which goes beyond the immediate environment of the programme.

The other issue is the representation of our research data. As Collins (op cit.) explains when using storytelling (here essays) as a method, it is important not to prioritize the researchers view over the participants (ibid, p.143). To tackle this problem, we complimented our autoethnographic-essays with other participants accounts and interpreted our own accounts as possible experiences in the context of the programme. Collins furthermore warns not to regard research using the narrative approach as „pluralistic, multi-vocal, non-discriminatory and non-privileging“ (ibid, p.144). Even if we included other actor's voices, they are interpreted and coded through us (ibid.). We, as well as our participants, have pre-assumptions and construct the research project and the represented truth. „[N]evertheless, researchers, not participants, are obligated to be reflexive about what we bring to the scene, what we see, and how we see it“ (Charmaz op cit., p.15). We are part of the construction of codes, therefore they never fully represent empirical reality (ibid, p.47). We understand that our deep-rooted perspective as white, female, educated researchers undoubtedly influences our research as well as „western standpoints on capitalism, individualism and competition“ (ibid, p.67). Especially with the autoethnographic approach and hence being part of the study ourselves, it was beneficial to work in a research team of two, to be able to reflect the research process. Steinke (2008) introduced a number of possible key criteria for qualitative research, but also specifies that not all of them have to be met (ibid, p.322 ff.). The quality of this thesis shall be examined on the basis of the following criteria:

- Intersubjective traceability (Transparency); „the degree to which the way the researcher comes to his or her conclusions is made transparent to others and hence open for evaluation” (Demuth 2013, p.36),

- Grounding of the Interpretation (Empirical Support); „the degree to which interpretations are sufficiently grounded in the data” (ibid),

29

- Credibility; „the degree to which the findings reflect the actual Lebenswelt („lived experience”) of the participants” (ibid)

- Systematic Proceeding; „the degree to which analysis has been conducted in a systematic way and is based on accepted procedures for analysis and has correctly applied the relevant analytical steps of a specific procedure” (ibid, p.38)

- Reflection of a Researcher’s Subjectivity; the degree to which the researcher’s subjectivity has been reflected in the analysis” (ibid.)

The intersubjective traceability, or transparency, of our research is achieved by the documentation of the methodological and analytical steps we undertook throughout the research. Our methods also become transparent through revealing our interview guidelines and coding categories (Appendix 4 & 6). Our research has empirical support: Initial and focussed coding, as well as complimentary data collection was used. Also, sufficient data references are given to demonstrate the building of our categories. We tried to achieve high credibility by designing our research as non-intrusively as possible, by focussing on building a trustworthy atmosphere in our interviews and general contact with our participants (Demuth 2013, p.36). We conducted our analysis in a systematic way, based on constructivist grounded theory. Finally, we reflected on our subjectivity and the researchers influence on the theory building throughout our research. Concerning this we also see it as an advantage to work in a team: we coded the transcribed material independently, comparing our codes and developed categories later on. We had another chance to reflect and discuss our thoughts, underlying assumptions and together, developed the key concepts our suggestion and this thesis is modelled on (Mayring 2010).

30

6 Matrix of Student Activity & Central Concepts

6.1. Matrix of Student Activity

In this chapter, we will present a revision of our previous scale of audience activity, which was developed through the analysis and constant comparison of the data as well as the integration of interdisciplinary literature. Subsequently, our model – a matrix of student activity (figure 8) – will be used to situate and discuss important concepts (participation, engagement and collaboration) connected to student engagement.

Following grounded theory, we stayed close to the material and coded actions and processes (Charmaz 2006). Our lead question was: how does the audience describe their actions relating to the master programme? Analysing our data and comparing our developed categories to our previous model (chapter 4.4.), we noticed three major points:

1. We will not be able to show all discovered audience actions on a linear scale; more dimensions are needed to represent the depth of possible actions.

2. Due to their various meanings, the use of theoretically laden terms can be misleading. 3. Activeness and being social do not necessarily have an interdependency.

Focusing on our data and taking a step back from our starting point in audience theories, we discovered that there were two different groups of actions: internal and external actions, as will be explained in the next chapter. Contrarily to our previous model, these actions will be separated. Internal- does not depend on external activeness. Rather they are two very different ways of interacting with one’s surroundings that can be carried out more or less actively. As a result of investigating a learning environment that takes place on-campus as well as online, another dominant factor in our data was the social dimension. This dimension describes if actions take place solitary or in a social setting and could already be found in the previous model.

31 Figure 8: Matrix of student activity

To develop the different axes, we mainly drew on basic actions that are carried out in a classroom and which we observed studying the programme. Also, the exemplary actions we situate in the matrix are basic actions many of our participants mentioned and we ourselves experienced; they stem from key situations of being an online or on-campus student.

The matrix is not intended to measure degrees of internal/external activeness or social involvement, rather it shows general tendencies. It is an abstraction that cannot reflect exact propositions. A student that is taking part in a discussion is not necessarily more internally active than a student that is only listening. Moreover, the matrix can only display a simplified version of student actions. To determine where an action is situated, we used our participants explanations of internal or external processes and related them to other situations they described, as well as using our own experiences. The factors that are building the basis of our new matrix of student activity will be outlined in the following.

6.1.1 Dimension A: Internal Activeness

Internal activeness entails processes that take place inside a student’s mind and cannot be observed by the researcher. Of course, it can be argued that some activity can be found inside

32

a person’s mind at all times (Jensen 2005). However, not any internal activeness is depicted on this scale. To make sure the matrix shows student activity in connection to learning, internal activeness that is not course related is situated on the zero-point of our scale (thinking about how to improve your mother’s cake recipe while watching a lecture). Internal activeness describes actions like listening to lectures and other students, thinking, processing, making sense of the course literature, reflecting on or transferring the content of the programme. This dimension is not limited to the classroom or the timespan of the lecture but can also take place preparing or following-up lectures.

6.1.2 Dimension B: External Activeness

External activeness consists of visible processes and can be observed by the researcher. It includes writing, reading, creating things and talking or discussing with other people. Differently to internal activeness, all processes of external activeness show up on our scale, not only course-related. Of course, this thesis will mainly focus on those that happen in connection to the programme. They do not necessarily have to happen immediately or in a social surrounding, though. Taking notes when watching a lecture afterwards and searching for further material, for instance, also describe external activeness. At this point, it can be argued that all living things are inevitably externally active, even just by breathing. This is why values on this axis never reach the zero-point. As already mentioned though, we do not intend to accurately measure degrees of specific forms of external activeness through our matrix.

6.1.3 Dimension C: Social Factor of Actions

This dimension describes the social setting a person is in. The determining factors of socialness are the social affordances an environment offers (Gibson 1979; Norman 2013). Affordances „refer to the potential actions that are possible” (Norman 2013, p.145). Important, however, is that they need to be perceived by the actor as a possibility of (inter-)action (ibid.). Sitting in the

Glocal Classroom surrounded by fellow students or going out for a coffee with friends appear

high on the spectrum, as the perceived possibility for interaction is high in these situations. Another core issue of this dimension are digital spaces as social settings. The distance student sitting home alone and watching the lecture live could be situated high on the spectrum as the affordance for immediate interaction through the chat is given. Watching a lecture afterwards is considered to be on the lower end of the scale, because the possibilities for immediate

33

interaction are not as manifold. Of course, as we are living in a more and more connected world, the zero point of the scale is seldom reached. The connection through smartphones, for instance, is almost constantly present in our everyday lives. But this thesis will more so look at affordances of interaction that are also related to acquiring content-related knowledge about the master programme.

6.1.4 Connections to the Previous Model

The dimension of internal activeness is closely connected to meaning-making processes. Livingstone (2004) describes: an audience that actively decodes, makes sense of and interprets media texts (p.79). These processes are seen as crucial to gain a long-term understanding of the material (Cory) and the possibility to engage with, for example, literature, as the basis for developing knowledge and engagement.

Of course, the reading material, additional links posted on Itslearning, the [PowerPoint] slides from lecturers, assignment guidelines and course handbooks provided further possibilities or foundations of engagement […]. I noticed how much better my engagement and understanding became when I read all literature until the class. (Student 13)

Relations to the material are build and connections to previous knowledge made (Student 5). We see student engagement as deeply rooted in this dimension, as we will explain later on. Furthermore, we see Livingstone’s considerations about the context the audience is situated in (2004, p.79) reflected in our matrix, namely in dimension C, the social factor of actions. Of course, this axis only shows the social context the student is in at a specific time and does not reflect other notions, for instance her cultural background. However, the social context in which a person engages with course material is crucial to the overall learning experience, as well as deeply connected to meaning making processes. In a social context with students, teachers or outside actors that share their perspectives, a student is able to contextualize the acquired knowledge. This is often needed to gain a deeper understanding of the course material. Developing knowledge with and through other actors was also mentioned as especially important by our participants:

The most important part of education is that you are interested in a topic and are able to develop that during the discussions with other students in many different types of settings. Developing your interests and developing your ideas […] in interaction with others. (Svensson)

The last dimension Livingstone described is audience agency (2004, p.79). This dimension cannot be directly translated to our matrix. Even though the student is also taking part in

34

reshaping media, for example through collaborative project work, the last axis of external activeness also describes actions that do not necessarily have to challenge or transform existing media texts. It is much closer to everyday, non-normative practices – visible actions students

do.

Figure 9: Matrix of Student Activity combined with Livingstone (2004)

Different from the previous model, we did not include a passive dimension. If a student is distracted or not content-related internally active, it is represented by the zero point of the scale. A passive audience is not included, as being not active at all is almost impossible, as noted before.

6.1.5 The Purpose of Learning

Throughout our research we uncovered a question closely linked to the notion of student engagement, namely what the purpose of learning within the university setting is. Here, university courses as a tool for information gathering were contrasted with an open space for critical discussion and the joint development of knowledge with other students (Student 1). Garrison et. al (2010) define critical thinking as „the ultimate goal of higher education” (p.6).

35

The MCS websites further state the aim to teach students how to approach media „from a critical perspective” (Homepages MCS, n.d.).

These positions lead back to a position of constructivism. Acquiring knowledge is not equal to gathering as much information as possible, but to actively make meaning of the learnt and to construct knowledge by linking new information to prior experiences and the social environment. By listening to a discussion of other students, for instance, one actively constructs knowledge by relating the heard to previous information. This again shows the importance of contextualisation, which is an interplay between a student’s internal activeness and the social setting she is in. In the following chapter, we will explain the matrix more thoroughly by relating example actions and placing them along the three dimensions to describe further connections between them.

6.1.6 The Connections between the Three Dimensions

As noted in the introduction to the chapter, the actions we use stem from basic student experiences. There is no interdependency between internal and external activeness on our matrix.7 Even if a student’s external activeness is high and she is writing or drawing while watching a lecture it can still mean that her (content-related) internal activeness is low. This is the case when her mind is occupied with other things going on in her life and her drawings are not related to the course content. Other „audiencing” (Fiske 1992) activities that might take place while being involved in a learning environment (like checking the phone or executing other online activities) show up as externally active but are equally separated from internal activeness if they are not content-related. Moreover, the internal activeness dimension is not directly linked to the social dimension. Chatting with fellow students before the lecture about your daily life or going for a beer afterwards appears on the social dimension but with no internal activeness. Doing the same while discussing course related content or transferring knowledge heightens the degree of internal activeness. In this case all three dimensions are elevated. Even if it is tempting to draw an interdependency between the social dimension and the external activeness dimension, this is not the case. A student can watch a recorded lecture at home alone, where the affordances to interact with other students are lower than in a live

7 We recognize findings in the field of neuroscience concluding that „all external behaviors somehow correlate to

the brain’s internal processes” (Jensen 2005, p.107), but will not discuss student engagement on a level of this neuroscientific depth.

36

setting (even if connections via the internet etc. remain) but can also actively take notes and thus be externally active. Certainly, often there is also a tight interplay between the three axes. Internal activeness, for instance, often triggers external activeness. Another example that can be brought up at this point is communication, where internal activeness (e.g. listening to the other person), external activeness (e.g. answering) and of course the social dimension work together. Further connections between the axes will be explained in depth when investigating student engagement.

Figure 10: Matrix of student activity with possible student actions8