Creativity and maturity in team-based innovation

- a model for assessment of interaction quality in relation to task characteristics

Author: Bengt Köping Olsson, Department of Innovation management, Mälardalen UniversityAbstract

This paper deals with group creativity, i.e. production of originality through combination of differences, and suggests a model for assessment of innovation maturity, i.e. group maturity, in relation to work task characteristics vis-a-vi a shared content, i.e. group ideas. The process of generating original ideas and develop that kind of ideas in work group is defined as a complex activity, i.e. the co-operation of several mutually deviant factors such as combination of different knowledge areas, intensity of idea exchange and critical evaluation.

This research is conducted from the perspective of a team paradigm which means that group creativity and group dynamics are studied in the team's day-to-day work setting in order to develop an understanding of the competence and abilities at group level in relation to the tasks characteristic. In line with that perspective we propose that the team’s innovation quality should be understood and described in relation to the shared content evolving from team member’s interaction, i.e. the group idea. Furthermore, by taking a complex systems perspective, the team can be understood as an entity that can develop certain traits as well as inter-subjective competences.

Results from a questionnaire study, conducted in the framework of an ongoing evaluation and research project in the public sector in Sweden, with 80 respondents form the initial basis for the development and evaluation of a model for the assessment of maturity for team-based innovation.

The analysis of questionnaire data confirms the positive relationship between group performance, i.e. the production and development of creative ideas on the one hand and the quest for originality combined with critical analysis and evaluation on the other hand. Analysis of data from two of the four working groups also show that encouraging climate and extrinsic motivation, often considered to have major importance for creative performance, do not necessarily have that effect on idea generation and idea development.

Keywords: team interaction, group creativity, innovation maturity, competence

Background

Studies on group creativity are traditionally based on criteria for the individual level of creativity. We need to better understand what creativity implies on a group level, such as what conditions and skills are required to establish and maintain group creativity. We also need to increase our understanding of how the team's ability to establish interaction and dialogue can be trained and mature in order to function as container and processor of divergent perspectives and fruitful dialogue. Thus, we need to connect such research areas as group creativity and team development with interaction maturity and performance. To be engaged in a group interaction is a genuinely social activity where the borders between individuals and the collective are diffuse as well as changing. Hargadon and Sutton (1996) found that when groups address complex problems, many individuals contribute to the process, and (that) it is difficult to assign credit to any one individual for the design outcome. Therefore, social acts, as interaction in a group, should not be regarded as individual initiatives with a social application. Our research analyzes to what extent the group interplay accommodate one or several competence dualities and the quality of interaction is correlated with group members notion of evolving group ideas. The analysis of data has the perspective on the group level meaning that learning and maturity, competence and skills, are regarded as social and inter-subjective phenomena. This understanding of group level construction of meaningful content and acting strategies has the characteristics of circularity between group members and the evolving content. The notion of circularity have been described by Follett (1918), Buber (1923/1954) as well as Ludwig Fleck (1935). In particular, Flecks concept ‘thought collective’ describes how content and understanding develops through group interaction over time.

The study of group creativity

Creativity is typically defined as the ability to produce work that is novel, original or unexpected; and also appropriate, useful, of high quality, or otherwise meets task constraints (Sternberg, Lubart, Kaufman, & Pretz, 2005). This type of definition emphasizes the radically new and large breakthroughs which could detract from the creativity of everyday and organizational situations. A more nuanced and in our view more appropriate definition of creativity is Scott Isaksen & Harald Treffingers:

“Creativity is the making and communicating of meaningful new connections to help us think in many

possibilities; to help us think and experience in varied ways and using different points of view; to help us think of new and unusual possibilities; and to guide us in generating and selecting alternatives. These new connections and possibilities must result in something of value for the individual, group, organization, or society” (Isaksen & Treffinger, 1985).

Thus, creativity is ongoing in workplaces and not just a crucial dimension in the early front front end of development processes. Thompson & Choi (2006) makes a distinction between two research traditions, the group paradigm and the team paradigm. Research on nominal groups with face-to-face interaction shows that the interaction tends to limit the creative potential whereas research on innovation team has focused on how different context, individuals´ background characteristics and process factors improves performance and innovation (ibid). We need to consider these differences when concepts and findings from both paradigm is integrated. It does not necessarily mean that it is contrary and that combination of concepts from both paradigms should be avoided, instead, we argue that they should be integrated with prudence for continued

development of the research field. In addition, research on creativity often emanates from the researcher's understanding of the relationship between creativity and knowledge. It can be roughly divided into those who believe that knowledge is problematic for creativity (the tension perspective) and those who believe that knowledge rather is a prerequisite for creativity (the positive perspective) (Weisberg, 2006). In this field of tension between knowledge and creativity Weisberg argues that creativity essentially is about combining knowledge and motivation (Ibid). This notion of research on creativity, and of knowledge relation to creative production of valuable originality, corresponds well with the research presented in this paper.

Characteristics of team performance and team effectiveness

To collaborate in teams can often present challenges in several ways, both in terms of efficiency (outcomes) and work methods (performance) (i.e. Drazin et al. 1999; Salas, et al., 2005; Thompson & Choi, 2006). In spite of the difficulties in organizing teamwork with high performance and value of outcomes continues organizations in all types of business sectors to use small groups of employees to accomplish important tasks. Often enough, difficulties in cooperating or inefficient usage of group members competence and time becomes issues to deal with. Research on small groups has increased our understanding of how groups develop (see table No. 1).

Model Stages and components in group development Dimension

The FIRO-model, Schutz, (1958)

inclusion (belonging) - control (role search) - affection/openness (fellow feeling) climate or temperament Tuckman

(1965) Forming: rules are formulated and the members starts to know each others. Storming: structures grow up and interaction patterns emerge

Norming: members team roles becomes clear, a fellow feeling exists, the function of leadership is accepted

Performing: team structures are clear, the working approach has reached a degree of maturity, all members are focused on goal realization

structure Katzenbach & Smith (1993) ladder of team performance

high-performance team: Meets all the conditions of ‘real teams’ but are also deeply committed to one another’s personal growth.

real team: Have a clear purpose, goal and working approach for which they hold themselves mutually accountable for.

potential team: Strive for collective performance but is unable to establish goals and common working approach

pseudo-team: Everyone are ‘playing-safe’, the sum of the whole is less than the potential each member possess.

working group: Members have nothing in common, they rely on individual initiatives.

performance

Irving Janis,

1972 group cohesion performance

Wekselberg

et al (1997) regard group maturity as a multi-facetted phenomenon and analyze it as a relation between congruence of members´ attitude at the one side and congruence of group goal and members goals

performance

Moreland and Levine (1988)

investigation, socialization, maintenance, resocialization, remembrance). socialization Drazin et al.

(1999)

change, evolution and responsiveness outcome

Salas et al.

(2005) team leadership, mutual performance monitoring, backup behaviour, adaptability, and team orientation performance McGrath

(1991) Mode 1: Inception and acceptance of a project (goal choice), Mode 2: Solution of technical issues (means choice), Mode 3: Resolution of conflict, that is, of political issues (policy choice), Mode 4: Execution of the performance requirements of the project (goal

attainment).

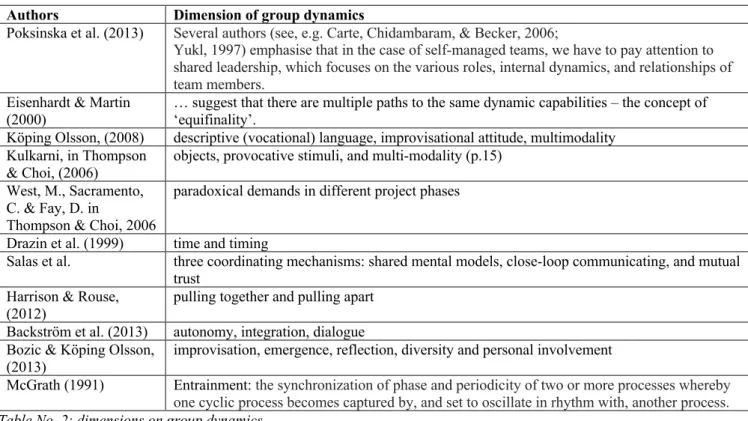

Research on small groups have also studied how group dynamic processes establishes different types of work climate (see table No. 2) and what are the important factors that enables works groups performance and efficiency, such as leadership and competence (Backström, et al. forthcoming).

Authors Dimension of group dynamics

Poksinska et al. (2013) Several authors (see, e.g. Carte, Chidambaram, & Becker, 2006;

Yukl, 1997) emphasise that in the case of self-managed teams, we have to pay attention to shared leadership, which focuses on the various roles, internal dynamics, and relationships of team members.

Eisenhardt & Martin

(2000) … suggest that there are multiple paths to the same dynamic capabilities – the concept of ‘equifinality’. Köping Olsson, (2008) descriptive (vocational) language, improvisational attitude, multimodality

Kulkarni, in Thompson

& Choi, (2006) objects, provocative stimuli, and multi-modality (p.15) West, M., Sacramento,

C. & Fay, D. in

Thompson & Choi, 2006

paradoxical demands in different project phases Drazin et al. (1999) time and timing

Salas et al. three coordinating mechanisms: shared mental models, close-loop communicating, and mutual trust

Harrison & Rouse,

(2012) pulling together and pulling apart Backström et al. (2013) autonomy, integration, dialogue Bozic & Köping Olsson,

(2013) improvisation, emergence, reflection, diversity and personal involvement

McGrath (1991) Entrainment: the synchronization of phase and periodicity of two or more processes whereby one cyclic process becomes captured by, and set to oscillate in rhythm with, another process. Table No. 2: dimensions on group dynamics

The research activities concerned with group creativity is to a large part engage in understanding conditions necessary to make differences interact in fruitful ways (Paulus and Nijstad, 2003; Page, 2007). The notion that collective reconsideration is crucial for quality and durability emphasizes the importance of social interaction (Olsson, 2008). In addition, rules of thumb and principles have been compiled by practitioners, some of them have been further developed and complemented by research on group creativity (see table No. 3). These efforts strive to establish conditions under which divergent opinions (i.e.

disassociated and deviating from each other) could be combined and interact constructively so that sustainable ideas may be developed.

Situation/

process Rules, principles or guidelines Author

Brainstorm • Don’t criticize! • Free wheeling!

• Quantity breeds quality! • Improve through combination!

A. Osborn, 1957

Brainstorm • maintaining focus

• do not tell stories or explain

• maintaining the brainstorming process • return to previous categories

Paulus, Nakui & Putman, in Thompson & Choi, 2006 Synectics • listening empathic

• support the good in a bad/weak idea • use analogical thinking to move forward • take a holiday (excursion) from the problem…

Prince, 1970

When

sparks fly • resist "the urge to merge ' • encourage deviant ideas

• place value on questioning (minority idea is perhaps better)

Leonard & Swap, 1999

Directing Leadership

• train the group’s dialogue competence • train the group’s improvisational attitude • ensure that leaders understand group creativity

Backstrom et al., 2013

Temporary

teams • high cognitive ability • openness to experience • clear structure interaction

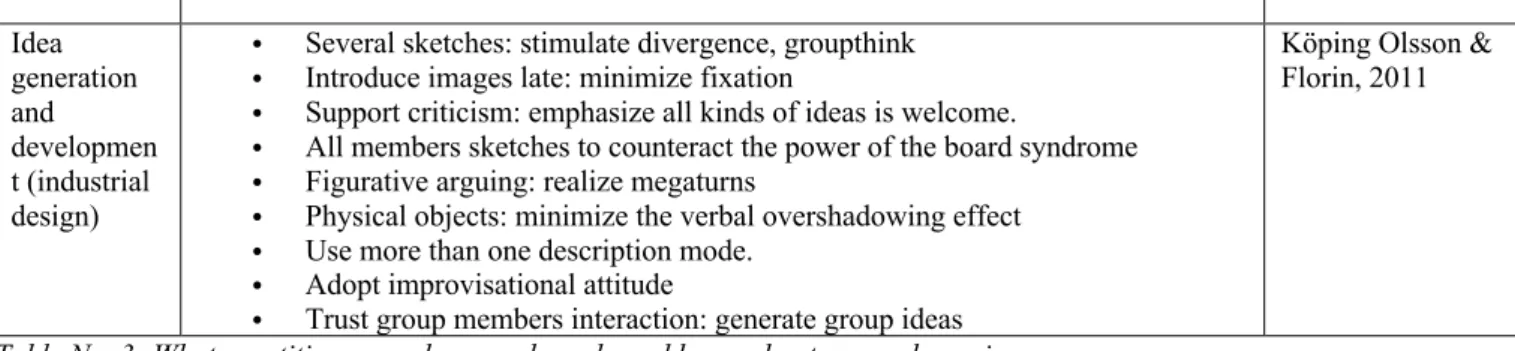

Idea generation and developmen t (industrial design)

• Several sketches: stimulate divergence, groupthink • Introduce images late: minimize fixation

• Support criticism: emphasize all kinds of ideas is welcome.

• All members sketches to counteract the power of the board syndrome • Figurative arguing: realize megaturns

• Physical objects: minimize the verbal overshadowing effect • Use more than one description mode.

• Adopt improvisational attitude

• Trust group members interaction: generate group ideas

Köping Olsson & Florin, 2011

Table No. 3: What practitioners and researchers do and know about group dynamics

Morgans et al. (1986) studies show that teams becomes increasingly proficient in their taskwork as members learn to work together. Several models of team development suggest that teams go through stages towards more complex relationship building and interaction (Salas et al., 2005). For instance, Katzenbach & Smith (1993) construct a ladder of team performance with five steps from working group to high-performance team and Tuckman (1965) argue that the development of

interpersonal relationships is a necessity for team members when going through the four stages forming, storming, norming and finally to successful performing. Moreland and Levine (1988) research focus on the socialization process through which a group member proceeds (investigation, socialization, maintenance, resocialization, remembrance).

Salas et al. (2005) state that team performance accounts for the outcomes of the team’s actions regardless of how the team may have accomplished the task and that team effectiveness takes a more holistic perspective in considering not only whether the team performed (e.g., completed the team task) but also how the team interacted (i.e., team processes, teamwork) to achieve the team outcome. In their effort to focus on group level performance Salas et al. (2005) put forward five core components of teamwork including team leadership, mutual performance monitoring, backup behavior, adaptability, and team orientation as well as three coordinating mechanisms shared mental models, close-loop communicating, and mutual trust. This approach, the “Big Five” of teamwork, is especially interesting for its efforts to focus on the group level, however, this still does not explain what skills and competencies the team needs to train and develop for these components to be established in the group. Moreover, they do not account for group creativity and the conditions it needs.

Petrovsky (1979) showed that groups differ qualitatively, and these differences affected almost every domain of group

behavior. For example, for highly developed groups, a positive relationship existed between the quality of relationships and the quality or quantity of performance, but for the less-developed groups, the same relationship was negative. Petrovsky (1983) also found that the addition of new members lowered productivity for less-developed groups but increased it for highly developed groups. The third problem involved group cohesion, introduced by Festinger et al. (1950) and was used, for example, by Janis (1972) as a measure of group quality in his groupthink research. Currently, group cohesion is still seen as an unproven attempt to describe group quality with a single variable but Wekselberg et al. (1997) argue that group maturity can be measured through different group characteristics such as 1) congruence of attitudes, 2) congruence of group goals and individual goals, 3) agreement on group goals and 4) group cohesion (Ibid).

Lack of knowledge regarding what kinds of conditions the work group should have in order to function creatively, that is, how all members differences contribute and are combined, could be a fundamental problem/challenge to begin with. Another dimension is the maturity of interaction, that is, the collective quality of acting as an entity. Wekselberg et al (1997) regard group maturity as a multi-facetted phenomenon and analyze it as a relation between congruence of members´ attitude at the one side and congruence of group goal and members goals in contrast with Irving Janis (1972) single variable group cohesion as a measure of group quality. Group cohesion is still seen as an unproven attempt to describe group quality with a single variable.

We define maturity as a group level capacity to deal with different types of dual opposites like divergent visavi convergent processes or usefulness visavi originality or susceptibility for originality visavi persistency against change. Ordinary teams could develop ability to work in convergent processes, look for and stop search when they come across a useful idea or strive to establish stability as soon as possible. In addition, the groups´ capacity to make quick shifts such as shifting between different group ideas is also an indicator for the level of group interaction maturity. The third dimension is the group members understanding of and relating to the evolving group idea. The notion of group ideas is important for several reasons to be described in the following, for now we define it as the background from which group members different acting is given meaning for the group members.

Quality of interaction vis-a-vis task characteristics

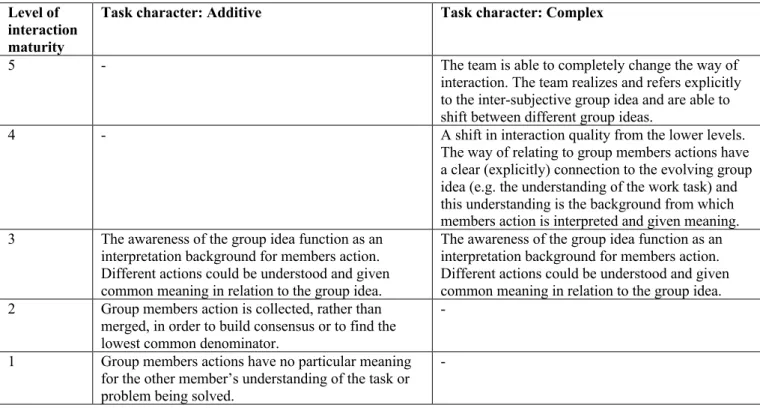

According to Sawyer there is a superficial distinction on group interaction, one is additive and the other is complex (Sawyer, 2007). Sawyer argues that we tend to use groups in wrong ways and not make use of the potential of interaction, and that the quality of interaction should correspond to the task or problem the group are supposed to solve. There are different types of tasks and there are different levels of interaction maturity as well. According to Sawyer (2007) a work task complexity is defined in terms of how many operations that team members are required to work on together face-to-face, while a

non-complex task can be performed more linearly without interacting face-to-face, such as via mail contact where each performs his part and sends to the next team member to add their part in the whole. An additive interaction characteristic is when every single group members contribution is collected and put together to find out similar and deviant opinions in order to reach consensus. That is, something that all members can agree upon – which often tends to be the lowest common denominator. But, to develop content through the pool of interaction and results or solutions based in all members continuous contribution is not an additive process. And, from a group-creativity point of view the evolving content, the result, will probably be both new, unexpected, and useful as well as created from genuine combination. Thus, it thereby meet all aspects in general definitions of creativity.

Level of interaction maturity

Task character: Additive Task character: Complex

5 - The team is able to completely change the way of

interaction. The team realizes and refers explicitly to the inter-subjective group idea and are able to shift between different group ideas.

4 - A shift in interaction quality from the lower levels.

The way of relating to group members actions have a clear (explicitly) connection to the evolving group idea (e.g. the understanding of the work task) and this understanding is the background from which members action is interpreted and given meaning. 3 The awareness of the group idea function as an

interpretation background for members action. Different actions could be understood and given common meaning in relation to the group idea.

The awareness of the group idea function as an interpretation background for members action. Different actions could be understood and given common meaning in relation to the group idea. 2 Group members action is collected, rather than

merged, in order to build consensus or to find the lowest common denominator.

- 1 Group members actions have no particular meaning

for the other member’s understanding of the task or problem being solved.

-

Table No. 4: Five levels of group interaction maturity in relation to work task characteristics

To act deviant in relation to the norms and values usually said to require courage and this is one of the four strongest standards for team-based innovation (Caldwell & O'Reilly, 2003). In the evaluation and selection of creative ideas to develop further, it is the lack of precisely this that makes the creative ideas with high potential for innovation is deselected in the early phases. On the one hand, originality is one of the criteria for the assessment of creativity, on the other hand tend analysts to not have the courage to explore more original proposal (Lonergan, Scott & Mumford, 2004).

We argue that in order to develop our understanding of team based innovation, creativity research needs to relate two dimensions and analyze them in correlation to each other. One dimension (variable) is social interaction, i.e. the interplay between group members. This is the essence of group. The other dimension is the content, i.e. the group idea - a shared and commonly developed thought formation. This legitimatizes and authorizes the existence of the work group. Thus, the purpose of our research is to understand the relation between different interaction qualities at group level and the emerging content (i.e. group ideas). We consider that two dimensions needs to be developed as well as related to each other in order for team based innovation to be achieved. One dimension is the development and training of group level skills and competencies supporting group creativity, the other dimension that needs to be related is the level of group maturity. We suggest four competences supporting group creativity:

1) Susceptibility for originality. To act deviant in relation to the standards and values is require courage. This is one of the four strongest standards for teambased innovation (Caldwell & O'Reilly, 2003). In the evaluation and selection of creative ideas to develop further is the shortage of this that makes the creative ideas with high potential for innovation are rejected in the early phases.

2) Persistency against change. Originality is one of the criteria in the assessment of creativity, on the other hand tend analysts to not have the courage to explore more original proposal (Lonergan, Scott & Mumford, 2010).

3) Combination readiness. Combination readiness is the group's tendency to establish relations between differences (Hargadon & Sutton, 1997), the ability for analogical thinking and understanding at the group idea level (Ratkic', 2006; Olsson, 2008). In terms of group interactions, this is the capability to understand group members' various actions as expressions of the same or related knowledge content (Lubaktin, Florin & Lane, 2001).

4) Expert knowledge. This is the group's capacity to house each team member's expertise so that it will be possible to express ideas or “springboards” in their own terms in their professional language (Olsson, 2008).

The second dimension in the assessment of team-based innovation is the group's innovation maturity level. Wekselberg et al. (1997) defines group maturity as a combination of several interrelated factors: the group's understanding of objective and the attitude to other team members, the concept of group cohesion is in their research measured as the extent to which group members' attitudes correspond with each other. The development models mentioned above (i.e. Katzenbach & Smith, 1993; Tuckman, 1965) and the group's Big Five components (Salas et al., 2005) can be used in assessing the groups' developmental level. However, group maturity should rather be evaluated as a relation between the degree of complex tasks (situation) and the production and development of creative ideas. Traditionally the variety of initiatives and flow of activity is considered to raise the quality of the creative processes. In addition, since Sawyers’ (2007) definition of complex tasks is based on the degree of exchange between group members, group maturity in team-based innovation be manifested by the way people interact, i.e. interaction quality. For creativity at group level, we propose that this criterion corresponds to the intensity of the interaction and exchange between group members. The groups´ capacity to manage intensity is important to consider in the assessment of its creativity and innovation potential.

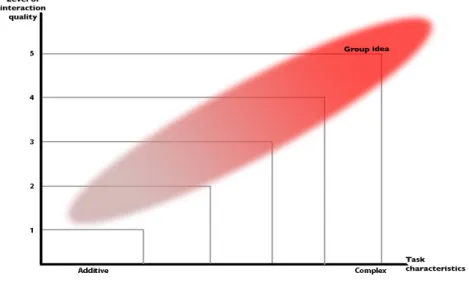

Assessment of teambased innovation maturity - interaction quality visavi work task characteristics

Our hypothesis regarding group maturity is formulated as follows: A high level of group interaction maturity is conditional for dealing with coexisting dualities and shifts of group ideas. The indicators in the assessment of teams innovation maturity level is to analyze the following three dimensions in relation to each other:

1) to what extent the group deals with complex work tasks described above. 2) to what extent all team members relate each member’s initiatives to a group idea. 3) the frequency of exchange of ideas and shifts between different group ideas.

Inspired of Dreyfuss & Dreyfuss (1986) five levels of competence from Novice to Expert is constructed. Our model for group level interaction maturity is described as follows:

First level - the Novice: Group members actions have no particular meaning for the other members understanding of the task or problem being solved.

Second level- the Beginner: Group members action is collected in order to build consensus or to find the lowest common denominator.

Third level - the Experienced: The awareness of the group idea function as an interpretation background for members action. Different actions could be understood and given common meaning in relation to the group idea.

Fourth level- the Competent: A shift in interaction quality from the lower levels. The way of relating to (attitude) group members actions have a clear (explicitly) connection to the evolving group idea (the understanding of the work task) and this understanding is the background from which members action is interpreted and given meaning.

Fifth level - the Expert: The team is able to completely change the way of interaction (in correspondence with intended duality-dimension). The team realizes and refers explicitly to the inter-subjective group idea and are able to shift between different the group ideas.

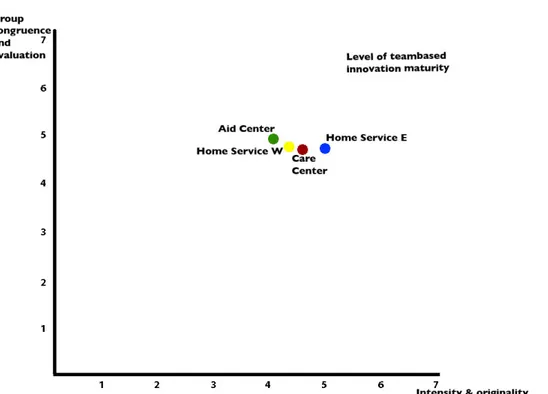

Figure No. 1: A model for the assessment of groups' innovation maturity by interaction quality and maturity in relation to the tasks characteristic.

Validation of this model remains to be done, we are going to use working groups within various sectors and work tasks. In this paper, data from a study of four work groups in the public health care sector is presented and empirical data from this study will be used to assess the groups' innovation maturity by the model described above (figure no.1).

Presentation of empirical data from four workplaces in the public health care sector.

In an ongoing evaluation and research project at a county council in Sweden studied a process for idea generation and idea development called The KINVO-model. Four workplaces have implemented The KINVO model over a period of eight months. A central method in the KINVO-process is called idea café intended to capture and develop employees' ideas. It is organized and led by an employee who have completed a four-day idécoach training. All employees in the work group are invited to participate in these cafés, to come up with their own ideas and improve them or by providing suggestions for the development of the ideas of others. There were two work groups in home service, and one work group providing assistive devices and one work group at a medical center. A total of 119 employees have in some way been concerned by the process of the KINVO model (see Table No. 5). The educational level of employees is high, i.e. more than half of employees with post secondary education, at two work groups and low, i.e. less than a quarter of employees with post secondary education at two work groups. The experience level is measured by the number of years employed in the profession.

Workplace Employee in

Idea café Survey respondents Education level Work experience, year >15 8-15 4-7 1-3 < 1

Care center 21 18 High 10 2 2 5 2

Aid center 20 19 High 5 6 6 2 1

Home-help

service W 43 27 Low 14 10 12 4 3

Home-help

service E 35 16 Low 10 13 8 2 2

Table 5: Number of employees of the participating work units in the implementation of The KINVO model, their level of education and number of years employed in the profession. High educational level represents more than half of employees with post secondary education and low levels of education equivalent to less than a quarter of employees with post secondary education.

When the work with implementing the KINVO-model had been going on for eight months, a questionnaire survey was answered by 80 out of total 119 employees, the respondents were requested to respond to 44 statements on a seven-point likert scale. Some of the results from this survey are presented in the table no. 7 below.

The measurement of outcome from work group performance is based on the amount of ideas being developed in the idea cafe process during eight months (table no. 6). Three categories of ideas were developed. Despite that the project encouraged development of physical products is there a significant difference between the working groups. The working groups within the Care center and the group working with auxiliary equipment for the disabled generated, almost exclusively developed ideas for improving the group's working methods, while the working groups in Home-service mostly focused on the development of physical products.

Work group Amount & type of ideas

Product Service Work routine

new improved new improved new improved

Care center 0 0 0 0 0 10

Aid center 5 0 0 0 0 15

Home-service W 2 0 0 0 0 0

Home-service E 6 10 1 0 0 4

Table No. 6: The amount and type of ideas produced at four work groups in the public healthcare sector during a period of 8 months.

Measurement of team members innovation competence

A) Members striving for originality: the quest for originality is measured by the following three dimensions. 1) group member's willingness to work together with people who do not think or act the same way, 2) not being afraid to present different ideas, 3) breaking the habitual behavior or make mistakes. This way of relating to the group's tasks and interact with members of the group is consistent with Caldwell & O'Reilly (2003) norms for team-based innovation.

B) Members interaction intensity and combination: measured through the following three dimensions. 1) if you often talk to members of the group about ideas and innovations, 2) to come up with new ideas by establishing new combinations, 3) if one is willing to try to understand group members' ideas and keen to build on them. These dimensions correspond with Sawyer's (2007) definition of complex tasks. But is also clearly linked to creativity by Osborn's principles for effective brainstorming session that emphasizes the ability to combine (to associate) as well as the amount of ideas exchanged.

Measurement of the group’s innovation maturity

C) The group's ability to maintain quality and learning in the work has been measured through two dimensions: 1) the extent to which the group aside time to evaluate their working methods, 2) to what extent the group routinely talk about their mistakes so that the whole group can learn from them.

D) The level of group congruence, i.e. members' attitude to the group have been measured through two dimensions: 1) the extent to which the team member considers that the team works well, 2) the extent to which the exchange of ideas and knowledge aimed at improving the way the group is working.

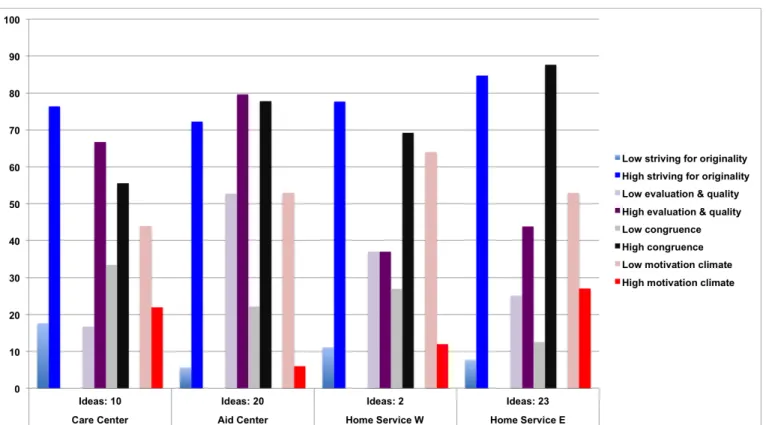

Table No. 7: The percentage level of group members high and low preference (striving) for originality respectively and estimation of the work groups’ motivational climate, members attitude regarding the groups quality and evaluation processes and group congruence. These dimensions are related to the amount of ideas developed during a period of 8 month at four workplaces in the health care sector.

As presented in Table No. 7 the analysis of survey data gave the following four dimensions of preferences; striving for originality, evaluation and quality, group congruence, and motivational climate, i.e. reward and recognition. The low and high values respectively are intended to show the spread between the members within the workgroup. Of the respondents' answers to a seven-point Likert scale respondents with value 1 to 3 are here reported as low and those who responded to the value 5-7 are here reported as high.

The level of members striving for originality is rather high at all four workplaces (Care Center: 76%, Aid Center: 72%, Home Service W: 78% and Home Service E: 85%) and the proportion of members who responded with low values are relatively few (17%, 6% 11% and 8%).

The level of evaluation and quality varies between the working groups, high values at Care Center: 67%, Aid Center: 80%, Home Service W: 37% and Home Service E: 44%. Low values Care Center: 17%, Aid Center: 53%, Home Service W: 37% and Home Service E: 25%. In the working group that produced the least number of ideas (Home Service W) is the proportion of members who do not consider that their group works with evaluation to improve the quality of work as high as the proportion who says that they do it. In the working groups which produced 10 to 20 ideas considers a significantly larger proportion of members that the group evaluates and improve their working methods than the proportion of members who think that happens very rarely. This relation suggests that analyzing and evaluating new ideas or ways of working could contribute positively to idea development at the workplace when those abilities also are combined with high levels of originality. The level of group congruence, i.e. group members' attitude regarding the group's ability to manage their tasks through efficient cooperation. The proportion of members giving high values at Care Center: 56%, Aid Center: 78%, Home Service W: 70% and Home Service E: 88% and low values; Care Center: 33%, Aid Center: 22%, Home Service W: 27% and Home Service E: 12%.

However, the proportion of group members who consider that the motivational climate, i.e. to be encouraged by rewards and recognition are generally low in all four working groups. High values at Care Center: 22%, Aid Center: 6%, Home Service W: 12% and Home Service E: 27%, while the proportion who consider that the work climate does not encourage creative

Figure No. 2: This diagram shows assessment of four work groups level of team-based innovation maturity measured from a compilation of mean value on group congruence and evaluation dimensions and members striving for originality and intensity of idea exchange respectively.

Discussion

Previous research have shown that teams can be the source of motivation and consequently of innovation when they pull advantages of different abilities and competences when developing ideas and preserved creative initiatives (Drach-Zahay & Somey, 2001; Cohen & Bailey, 1997). Dunbar (1995) have studied several research teams and found that a key factor to their achievements is situated in the group processes. The successful teams dealt with contradictory results, had some form of diversity in the composition and were engaged in the common reasoning.

This paper have, from the perspective of group creativity, presented a model for measurement and assessment of the groups' interaction quality and innovation maturity in relation to their work tasks characteristic. The reason for this is that activities that can be characterized as creative, such as the development of ideas in groups, requires the ability to manage several mutually incompatible yet necessary activities and knowledge areas more or less simultaneously. To be able to perform this type of complex work the group members are required to develop certain levels of quality in the way they interact and

creativity competence that drives creativity such as striving for originality and readiness for combination of deviant factors. At the group level the team also needs to develop certain capabilities such processes for evaluation and quality development and the ability to house each team member’s expertise and attitudes efficiently, i.e. group congruence.

Wekselberg et al. have defined group maturity as a combination between group members’ attitude regarding their capacity and the extent to which their perceptions of group goals are consistent, i.e. group cohesion. We suggest that group innovation maturity level should rather be evaluated as a relation between the complexity degree of tasks characteristics and the groups’ capability to house processes for evaluation and quality in combination with members striving for originality.

Results from a study on four work groups in public health care sector working with idea generation and idea development, shows that the working groups that both seek originality and at the same time do not hesitate to question, analyze, and evaluate their own and colleagues' creative ideas also produces more developed ideas. Analysis of empirical data shows that a high proportion of group members striving for originality is not enough to generate and develop creative ideas, this ability also needs to co-operate with a high degree of analysis and evaluation of ideas. Thus, the balance between both a high proportion of group members who strive for originality and a high level of team's ability to evaluate those ideas, which contributes to higher group performance, i.e. the duality of originality - criticism. In addition, the pursuit to combine differences in meaningful ways is also necessary in the team in order to be successful in this type of complex work tasks.

References

Backström, T., Moström Åberg, M., Köping Olsson, B., Wilhelmson, L., and Åteg, M. (2013). Manager’s Task to Support Integrated Autonomy at the Workplace: Results from An Intervention. International Journal of Business and

Management; Vol. 8, No. 22.

Backström, T., Bozic, N., Johansson, P.E., Olsson, B. K., Schaeffer, J., and Tjernberg, M. (forthcoming). The six delta model of innovation competence.

Bozic, N., and Olsson, B. K. (2013). Culture for Radical Innovation: What can business learn from creative processes of contemporary dancers?, Organizational Aesthetics: Vol. 2: Iss. 1, 59-83.

Buber, M. (1923/1994). Ich und du. I swedish: Jag och du, Ludvika: Dualis.

Caldwell, D. F. & O’Reilly. (2003). The determinants of team-based innovation in organizations: The Role of social influence. Small Group Research, Vil. 34: 497-517.

Cohen, S. G., & Bailey, D. E. (1997). What makes teams work: Group effectiveness research from the shop floor to the executive suite. Journal of Management, 23, 239-290.

Drach-Zahavy, A., & Somech, E. (2001). Understanding team innovation: The role of team processes and structure. Group Dynamics, 5, 111-123.

Drazin, R., Glynn, M A., and Robert K. Kazanjian. (1999). Multilevel Theorizing about Creativity in Organizations: A Sensemaking Perspective. The Academy of Management Review, Vol. 24, No. 2 (Apr., 1999), pp. 286-307.

Dreyfus, H. L. & Dreyfus, S. E. (1986). Mind over Machine. The Power of Human Intuition and Expertise in the Era of the Computer. London: Blackwell.

Dunbar, K. (1995). How do scientists really reason: Scientific reasoning in real-world laboratories. In R. J. Sternberg & J. E. Davidson (Eds.), The nature of insight (pp. 365–396). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Eisenhardt, K. M. & Martin, J. A. (2000). Dynamic capabilities: What are they? Strategic Management Journal. Vol 21: 1105-1121.

Festinger, L., Schachter, S., and Back, K., (1950). The spatial ecology of group formation." In L. Festinger, S. Schachter, & K. Back (Eds.), Social Pressures in Informal Groups: A Study of Human Factors in Housing. Stanford University Press. Fleck, L. (1935). Entstehung und entwicklung einer wissenschaftlichen tatsache: Einfu rung in die lehre von denkstil und

denkkollektiv. In translation: Fleck, L. (1997). Uppkomsten och utvecklingen av ett vetenskapligt faktum. Inledning till läran om tankestil och tankekollektiv. Stockholm: Symposion.

Follett, M.P. (1918). The New State: Group Organization. The Solution of Popular Government. New York: Longman, Green and Co.

Hargadon, A. & Sutton, R. I. (1996) Brainstorming groups in context: Effectiveness in a product design firm.

Administrative Science Quarterly, 41, 1996; 685-718.

Harrison, S. H., & Rouse, E. D. (2014). Let’s dance! Elastic coordination in creative group work: a qualitative study of modern dancers. Academy of Management Journal Vol. 57, No. 5, 1256–1283.

Isaksen, S. G. & Treffinger, D. J. (1985). Creative problem solving: The basic course.Buffalo, NY: Bearly Limited. Janis, I. (1972). Victims of groupthink: a psychological study of foreign-policy decisions and fiascoes. Boston: Houghton

Mifflin.

Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. T. (1999). Learning together and alone: Cooperative, competitive, and individualistic kaniing. Needham Heights, Mk Allyn and Bacon.

Katzenbach, J. R. & Smith, D. K. (1993). The Wisdom of teams: Creating the high-performance organization. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Leonard, D. & Swap, W. (1999). When sparks fly: Harnessing the power of group creativity. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Lonergan, D. C., Scott, G. M. and Mumford, M. D.(2004) 'Evaluative Aspects of Creative Thought: Effects of Appraisal and Revision Standards', Creativity Research Journal, 16: 2, 231 — 246.

Losada, M. and Heaphy, E. (2004). The Role of Positivity and Connectivity in the Performance of Business Teams: A Nonlinear Dynamics Model. American Behavioral Scientist 2004; 47; 740.

Lubaktin, M., Florin, J. and Lane. P. (2001). Learning together and apart: A model of reciprocal interfirm learning. Human

Relations, 54(10): 1353–1382.

McGrath, J. E. (1991). Time, interaction, and performance (TIP): A theory of groups. Small Group Research, 22(2), 147-174. McLaughlin, P., Bessant, J. and Smart, P. (2008). Developing an organisation culture to facilitate radical innovation. Int. J.

Technology Management, Vol. 44, Nos. 3/4, pp.298–323.

McGrath (ed), The social psychology of time: new perspectives (pp 151-81). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Morgan, B. B., Glickman, A. S., Woodard, E. A., Blaiwes, A. S., and Salas, E. (1986). Measurement of team behavior in a Navy training environment. (Tech. Rep. TR-.‐86-.‐014). Orlando, FL: Naval Training Systems Center, Human Factors Division.

Olsson, B. 2007, Languages for creative interaction: descriptive language in heterogeneous groups. Proceedings of The 10th European Conference on Creativity and Innovation, ECCI-X, Copenhagen 14 – 17 October, 2007.

Olsson, B. Descriptive languages in and for creative practice: Idea development during group sessions. In Swedish Beskrivningsspråk i och för kreativ praxis: Idéutveckling under gruppsession, Doctoral Dissertation 1651-4238; 68. Mälardalen University Press, Västerås, Sweden, 2008.

Osborn, A. F. (1957). Applied imagination: principles and procedures of creative thinking. New York: Charles Scribner. Paulus, P. B. & Nijstad, B. A. (Ed.) (2003). Group creativity: Innovation through collaboration. New York: Oxford University

Press.

Petrovsky, A. V. (1979). Psychological theory of collective. Moscow: Pedagogika. In In Wekselberg et al. (2006).

Petrovsky, A. V. (1983). Toward the construction of a social psychological theory of the collective. Soviet Psychology, 21, 3-21. In Wekselberg et al. (2006).

Poksinska, B., Swartling, D., & Drotz, E. (2013). The daily work of Lean leaders – lessons from manufacturing and healthcare. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 24:7-8, 886-898.

Ratkic´, A. (2006). The Dialogue seminar research environment. Doctoral dissertation at The Institution for Industrial Economics and Organization, Royal Institute of Technology, KTH. Stockholm: Dialoger

Reid, F. J. M., & Reed, S. (2000). Cognitive entrainment in engineering design teams. Small group research vol. 31 no. 3, pp. 354-382.

Prince, G. M. (1970). The practice of creativity. New York: Harper.

Salas, E., Sims, D. E., and Burke C. S. (2005). Is there a ''Big Five'' in Teamwork? Small Group Research, Vol. 36 No. 5, 555-599.

Sawyer, K. (2007). Group genius: the power of collaboration. New York: Basic Books.

Schutz, W.C. (1958). FIRO: A Three Dimensional Theory of Interpersonal Behavior. New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart, & Winston.

Smialek, T. and Boburka, R. R. (2006). The Effect of Cooperative Listening Exercises on the Critical Listening - Skills of College Music-Appreciation Students. Journal of Research in Music Education 2006 54: 57.

Sternberg, R. J., Lubart, T. I., Kaufman, J. C., & Pretz, J. E. (2005). Creativity. In K. J. Holyoak & R. G. Morrison (Eds.), Cambridge handbook of thinking and reasoning (pp. 351–370). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Thompson, L. & Choi, S. H. (Eds.) (2006). Creativity and innovation in organizational teams. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Tuckman, B. (1965). Developmental sequence in small groups. Psychological Bulletin, 63 (6): 384-99.

Weisberg, R. W. (2006). Creativity: understanding innovation in problem solving, science, invention, and the arts. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Wekselberg, V., Goggin, W. C., and Collings, T. J. (1997). A Multifaceted concept of group maturity and its measurement and relationship to group performance. Small Group Research 1997 28: 3