1

Understanding and Facilitating Creative Group Processes: The GroPro Model

Tomas Backström Mälardalens Högskola

Abstract

Collaborating individuals can often find better solutions, still individual creativity is in focus both among managers and academics. There is a need for theorizing about groups’ creativity. The GroPro model, described in this article, uses a process ontology to support increased group creativity. GroPro is based on theories about group dynamics, actor-structure processes, human interaction, and leadership. It was developed as a sub-task in several research projects about the group and its first line manager. The GroPro model integrates all phenomena relevant to group creativity, is complex enough to consider individual and collective interdependences, and examples of how GroPro has been employed show its potential use as a practical guide in one’s own creative group processes.

Keywords: creativity, group, innovation, actor-structure, emergence

Introduction

Owing to the synergetic potential of mixing diverse knowledge, collaborating

individuals can often find better solutions for complex situations (Rubenson & Runco, 1995). Consequently, the team has become the basic organizational unit of development and

innovation work (Burke, Stagl, Salas, Pierce, & Kendall, 2006; Huang, 2009; Kozlowski & Bell, 2003; Kratzer, Leenders, & van Engelen, 2006; Rubenson & Runco, 1995; H. K. Tang, 1998). Still, individual creativity is often the focus, both among managers (Bissola &

Imperatori, 2011) and academics (Kurtzberg & Amabile, 2001; Paulus & Nijstad, 2003; West & Wallace, 1991), which consequently leads to an additive understanding of collaborative creativity. However, both theories (Nijstad & Paulus, 2003; Rubenson & Runco, 1995; Woodman, Sawyer, & Griffin, 1993) and empirical research (Bissola & Imperatori, 2011; Saad, Cleveland, & Ho, 2015) point to group creativity as being more than the sum of the group members’ creativity. This article will present a model of group creativity that explains how a group can be more creative than its members and give support to people that intent to study or facilitate the creativity of groups.

The need for theorizing and theory-driven studies is one of the key themes for future research suggested in a state-of-the-science review on innovation and creativity (Anderson, Potocnik, & Zhou, 2014). The authors were “struck by the relative lack of theoretical advances across the creativity and innovation literatures in the past decades” and recognized that “the most valuable avenues we consider will be to proffer…models and theoretical propositions to explain cross-level and multilevel innovation” (p. 1,318). This article aims to answer that call.

The Group Process (GroPro) model will be described in this article. It is intended to be detailed and complex enough for researchers studying group creativity, but also simple and practical enough for practitioners to use in their work to enable and affect group creativity. GroPro is able to integrate the different antecedents of group creativity according to empirical research. Most research thus far has used variances to find antecedents to group creativity; that is, to produce knowledge about what is or what works. Instead, by using a process ontology (Langley, Smallman, Tsoukas, & van de Ven, 2013), GroPro aims to produce

2

knowledge about how to increase group creativity. From a process ontology perspective group dynamics and emergence are two central concepts. Group dynamics is central as the process of group creativity includes both the production of new ideas and the stability to be able to integrate them into a solution or an innovation. Emergence, then, is the most

important aspect of the development part of group dynamics (Cronin, Weingart, & Todorova, 2011). Emergence will thus be used to both understand the relationship between group

members and the group itself (Archer, 1995), and to define group creativity as emerging from the interactions among group members (Backström & Söderberg, 2016).

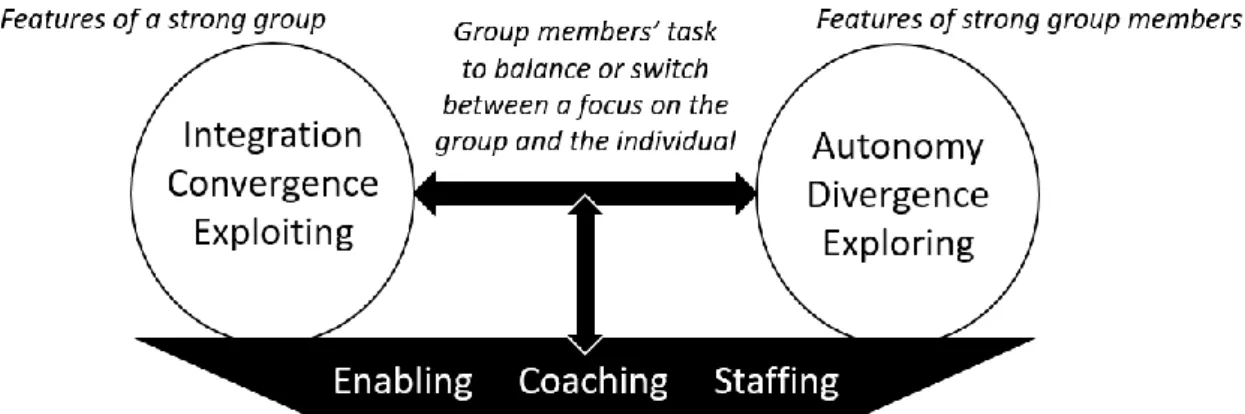

Figure 1. The different parts of the GroPro model. Three features of a strong group, three features of strong group members, and three tasks of the facilitator.

Figure 1 presents a simplified description of practitioners. The GroPro model consists of three tasks given to the manager and six assigned to the group members. The manager has to staff the group in a good way, enable its creativity, and coach the group’s work in the right direction. On the one hand, the members must lead each other to be strong individuals, developing divergent information by having an autonomous relationship to the group and the task, and by exploring new information and experiences. On the other hand, the group must integrate into a strong collective around its task to ensure that information converges into a common understanding among the members, and to exploit the group’s resources for a solid solution.

The work of managers is often described as containing two tasks: performance-oriented, with a focus on production and adaptation to the current situation; and development-oriented, with a focus on generating new knowledge and solutions (McGill, W. & Lei, 1992; Minzberg, 2009; Wallo, Ellström, & Kock, 2013). This division into two tasks is comparable to classical exploitation and exploration duality, coined by March (1991). By including the individual and group levels, GroPro points at a third managerial task: team coaching oriented, with a focus on enabling and affecting emergence and self-organization in groups of subordinates. This is also a way to reach both performance/exploitation and development/exploration at the same time (Backström, 2017).

The term group is defined as at least two people that recurrently interact to solve a common task. Recurrent interaction is needed for convergence into a common understanding, which is

3

the basis for integration into a group and the ability to exploit its resources in a self-organized way. The upper limit of how many members a group can have is dependent on the

self-organization competence of the members and the time they have to self-organize.

The GroPro model was developed over a period of ten years as a sub-task in several research projects with different objectives: increased sustainability (Backström, 2004; Backström & Söderberg, 2007; Backström, Hagström, & Göransson, 2013), increased group competence (Backström, Moström Åberg, Köping Olsson, Wilhelmson, & Åteg, 2013; Wilhelmson, Åberg, Backström, Olsson, & Åteg, 2015), and increased group creativity (Backström & Söderberg, 2016), and to include innovation in quality management (Fundin, Backström, & Johansson, 2018). Common denominators of these projects are a focus on the group with its first line manager, and the use of emergence and complex adaptive system theories to understand and affect the research subjects. In recent years, the model has been used to train employees and managers in organizations, as well as university students. Furthermore, it has been used to design self-assessments of the organizational climate for creativity (Cedergren, Backström, Blackwater, Johansson, & Wikström, 2017). This article will provide a short summary of our earlier findings from using the GroPro model. Moreover, the GroPro model will be used to integrate outcomes of research about antecedents into group creativity. The GroPro model is non-commercial; thus, it is for anyone who wishes to use it. The author is happy to support testing if needed and looks forward to receiving user feedback regarding the use of GroPro.

Position in the Field of Creativity, and How to Define and Measure Group Creativity Creativity is generally conceptualized as the production of ideas that are novel as well as useful (Anderson et al., 2014). The focus may be on creative output (Amabile, 1982), the creative process (Stein, 1953), or creative capacity (Torrance, 1971). Definitions of creativity have a social dimension, since the degree of novelty and usefulness is something others have to judge (Csikszentmihalyi, 1996).

Individual creativity is often the focus, but empirical research shows that group creativity is more than the sum of the different individuals’ creativity. For example, in an experiment comparing creativity in groups composed of individualistic Canadian and collectivistic Taiwanese participants, respectively, the Canadians scored higher in terms of individual creativity, while the Taiwanese scored higher on group creativity (Saad et al., 2015). In an experiment that tested over 1,000 people, the groups with relatively uncreative members produced creative results more often (54%) than the groups with creative members (42%) (Bissola & Imperatori, 2011). It seems as though the emergence of unique collaborative creativity crystallizes first at the social level (Jiang & Zhang, 2014; Sonnenburg, 2004). It is possible to distinguish at least two perspectives on group creativity (Anderson et al., 2014; Glăveanu, 2010). Firstly, in componential theories used in variance studies of creativity, the environment has an impact on creativity by affecting components that

contribute to creativity (for example, the KEYS instrument; Amabile, Conti, Coon, Lazenby, & Herron, 1996). Here, the other members of the group are seen as an external environment relative to the individual, a set of stimulations that facilitate or constrain the creative act. The three major components contributing to small group creativity according to this perspective are expertise, creative-thinking skills, and intrinsic motivation (Anderson et al., 2014). Secondly, with process theories, creativity results from a collective process. The focus is on interactions (Woodman et al., 1993), sensemaking (Drazin, Glynn, & Kazanjian, 1999), or procedures (Hargadon & Bechky, 2006). Here, creativity is a complex interaction between

4

the individual and his/her situation, and there is interdependence between the individual and the others in the group. According to this perspective, the major aspects leading to increased group creativity are individual creative behavior, interactions between group members, group characteristics, group processes, and contextual influences (Anderson et al., 2014). GroPro uses a process perspective, with emergence as a core idea.

Emergence, the most important feature of group creativity dynamics (Cronin et al., 2011, Jiang & Zhang, 2014), is a phenomenon that is explored in complex systems theory. It deals with the link between the individual and the group (Sawyer, 2005) and sees this connection as a circular causality (Haken, 1996). At the collective level, organizing structures emerge through interactions between individuals. At the same time, these collective structures influence the interactions between individuals. The emergent collective structures thus self-organize the group. The causal links in the process of emergence will be further developed below using critical realism.

We define group creativity as the extent to which group members suggest and promote novel ideas that the group recognizes and uses. Creative output is commonly measured by the number of ideas and the uniqueness of the final result (estimated by experts using, for example, the Consensual Assessment Technique, or CAT; Amabile, 1982). In addition, we suggest two measures that have to do with the flow of ideas. It is possible to distinguish threads in the interaction, which is when an idea attract the attention of other group members and is developed interactively into a group idea including contributions from several

members (Olsson, 2007). Group ideas start with a novel idea, an idea that is not built on ideas mentioned earlier in the interaction, which becomes shared within the group through

interaction (cf. also the concept connectivity Losada & Heaphy, 2004). Several possible variables to measure group creativity are found in this definition:

1. The number of group ideas (i.e., novel ideas that attract the attention of other group members).

2. The number of individual ideas produced in an interaction tread belonging to a group idea.

3. The number of group members engaged in the group idea. 4. The level of promotion and use of a new idea:

a. The idea is ignored by other group members.

b. Group members encourage or criticize the novel idea. c. The novel idea is also used to produce further new ideas. d. The group idea is also used in the final solution or innovation.

The Central Theories behind the GroPro Model

This article uses a process theory and formulates the GroPro model, which integrates former research on group creativity according to this perspective. Hence, it must include influences on the group from the context, the characteristics of the group’s members, and the

interactions between group members, including consequential emergence. Several theories have to be combined to reach this.

The central theories behind GroPro will be presented in three passages.

1. The Process: Interacting Agents and Emerging Structures deals with how to understand and describe dynamics associated with the social process, where emergence will be modeled as two kinds of alternating time periods

a. Time periods with interacting actors.

5

interaction in the next time period. Three kinds of structures will be highlighted.

i.External structures. ii.Internal structures. iii.Cognitive structures.

2. The Interaction: Three Aspects and Two Perspectives involves an analytical separation into three different aspects of importance for the time periods with interacting actors (1a above).

a. Relationships b. Information flow c. Action

Each of these aspects have a duality of perspectives, one for the actors and one for the group.

3. The Management: How to Facilitate Creative Group Processes covers management and leadership, where three tasks for managers or facilitators of creative groups are distinguished.

a. Staffing. b. Enabling. c. Coaching.

The Process: Interacting Agents and Emerging Structures

McGrath, Arrow, and Berdahl (2000) criticized most studies of groups for using chain-like, unidirectional, cause-effect relationships. They describe group dynamics as including three levels of dynamics: group member level, group level and contextual level. Hence, “to study dynamics one must consider multilevel influence relationships” (Cronin et al., 2011). There are scarcely any contributions of multilevel approaches to organizational creativity, not only among componential approaches, but even process theories of group creativity “neglect to examine the link between individual creative capability and the level of collective creativity” (Bissola & Imperatori, 2011, p. 79). Using this strict definition of dynamics, group dynamics is rarely explored in the general study of groups (Cronin et al., 2011; Kozlowski & Bell, 2003; McGrath & Argote, 2001; McGrath et al., 2000). We need to “better distinguish the individual and the collective level and the emergence of team coordination” (Kozlowski & Bell, 2003, p. 366).

Cronin, et al. (2011) suggested a model for the study of group dynamics, which includes three dynamic profiles of phenomena: contextual, cumulative, and emergent. The contextual constructs apply to group properties that are imposed on the group by external forces. The cumulative ones are based on stable individual properties, which come about when the group members are assigned. The emergent constructs are group level phenomena that emerge over time in the interactions between group members. The cumulative construct is similar to staffing in the GroPro model, and the contextual construct is similar to enabling. Both active management (such as staffing and enabling) and self-regulatory processes (such as emerging) are required for group creativity (Bledow, Frese, Anderson, Erez, & Farr, 2009). The staffing and enabling set the stage for what Cronin et.al. describe as the most dynamic part of the model: the emergent constructs (Cronin et al., 2011). Staffing and enabling will be dealt with under the heading “The Management: How to Facilitate Creative Group Processes.” Here, the focus is on the emergence that occurs inside this container of external structures.

6 Figure 2. Three constructs of a group’s dynamic.

Emergence can be described by a combination of the refined transformational model of social action (Bahskar, 1989) and the morphogenetic/static cycle (Archer, 1995), approaches based on critical realism. In her model of morphogenesis (from the Greek morphê, which means “shape” and genesis, which means “creation”) Archer (1995) describes the process that causes a system to develop its structures. Social structures are seen as inseparable from their human components, transformable (without any settled or even preferred state) through human actions, and affecting human actions. The approach has two levels (structures and social interaction) and a time dimension, with four times (T1–T4). At time T1, there are

pre-existing structures (outcomes of prior cycles). At T2, these structures condition the social

interaction. At T3, the social interaction will either reproduce the pre-existing structures

(morphostatis) or transform them (morphogenesis), and at T4, the structures conditioning the

next monogenetic cycle will either be the same as before or different.

The GroPro model is based on the idea that structures are either reproduced or transformed, or as we say either “reinforced” or “modified” to better fit with our understanding of

dynamics. The time steps are also kept, but for simplicity’s sake, the start and end points of the interaction (T2 and T3) are combined into one, including all interactions at that point in

time (T2). Furthermore, two extra levels are added to the model of morphogenesis from the

model of group dynamics. The external structures form the container for emergence (see figure 2). The actors, the members of the group, are explicitly added with their individual properties and cognitive structures.

Figure 3 illustrates the basic building blocks for understanding dynamics in a social process. This is both the smallest possible description of the dynamic process, and the only necessary building block to describe the dynamics (Fundin, Backström, & Johansson, 2018). The building block is an analytical form for describing dynamics, and has to be filled with different content depending on the system studied. Here, as it is used at the group level of an organization in work life, the three kinds of structures at T1, can be described as:

External structures (for example, the formal allocation of responsibilities, task formulations, standards, and the technical system) are like a container defining the context within which the group works.

7

things, and institutionalized habits) emerge in the interactions between group members.

Cognitive structures (for example knowledge, understanding, and experiences) are the individual basis for the actions of the people included in the group.

An interaction occurs between people with their cognitive structures, organized by the internal and external structures at the next point in time, T2. They interact while performing

their task. There will be variances introduced in the interaction from the working material, the equipment, the task, and from the interacting people.

The three kinds of structures lie at T3. The external structures are, by definition, not changed

by this interaction, but the other two are either reinforced or modified. A modified cognitive structure is equal to individual learning, and a modified internal structure can be called group learning. The structures of T3 form the starting point for the following building block, the

next interaction between people at T4.

Figure 3. The basic building block in the model of dynamics in social processes

Human interactions can be studied and enabled from both the individual and

collective perspectives. The two perspectives can be described as two sides of the same coin: a duality between individual details and plurality on one side, and the collective structure and unity on the other. Both sides are always there and depend on one another. It is common to try to suppress one side of the duality, only to see the individuals and ignore the group as part of the context, or vice versa (Fundin, Backström, & Johansson, 2018). However, the

presented model of dynamics in the social process transcends this duality, and models how the individual and the collective are complementary and interwoven (Lewis, 2000). This is also true for our model of interaction, which we will discuss next.

The Interaction: Three Aspects and Two Perspectives

8

aspect has to do with the relationships to other group members and the group’s task. Another aspect has to do with how the members interact; the information flows in, for example, in meetings. The third aspect involves the external actions of the group members. All three have both an individual and a collective perspective.

1. Relationships. At each point in time, group members have a choice between two perspectives: Identifying oneself as autonomous or integrated in relation to the group and its task.

2. Information flow. At each point in time, group members have a choice between giving divergent information during the interaction, or to take part in a process of convergence and form shared values and understandings.

3. Action. At each point in time, group members have a choice between

exploring and experimenting to find new information, or to coordinate with the group, exploiting its resources to fulfill its task.

This is based on the human interaction dynamics (HID) model (Hazy & Backström, 2013), a normative model that illustrates that a good dynamic balance between these aspects and perspectives will lead to self-organization, as well as the ability to adapt and transform when necessary, and thus to high fitness and long term sustainability as a system. The six outposts of the HID model can be used to describe the interactions underlying emergence in all kinds of complex systems. In the GroPro model, we use the HID model to understand the emergent part of group creativity and integrate it into the model of dynamics in social processes. Information flow will greatly affect the outcome of interactions at T2. If only convergence

occurs, then the internal and cognitive structures will be reinforced at T3. If divergent

statements occur, and are used as a basis for collective reflection and a process of convergence towards a modified understanding, then both the internal and cognitive structures will be modified at T3.

Relationships first act as a base for the individual to choose a divergent or convergent perspective in the interaction. From the perspective of being autonomous, it is easier to find and use divergent ways to understand things, which are needed to modify structures at T3. In

contrast, when a group member identifies him/herself as an integrated part of the group, it is easier to take part in a process of convergence. Secondly, relationships affect the structures that the actor will use. When the group member takes an autonomous perspective in the interaction at T2, he/she uses more of his/her own cognitive structures at T1. However, when

he/she takes an integrated perspective at T2, he/she uses more of the internal and external

structures of the group at T1.

For action, exploiting perspective is ideally the group’s goal; that is, to use its resources to perform its task. On the other hand, exploration offers the possibility to develop better divergent information to use at T2, when a group member is unsatisfied with the existing

structures at T1 and wishes to change them at T3. Exploration can be seen as an interaction

with people outside the group or even with physical objects. Thus, interactions during T2

might also include an apartness, where group members interact outside of the group. Such external interactions may modify the cognitive structures of the interacting person, but for the group’s internal structures to be modified, this new, divergent information must be presented in a group interaction, and convergence must be reached regarding it.

In the creative group process, an oscillation between collective togetherness and individual apartness may be preferable. One important consequence of letting group members work

9

individually part of the time is that everyone is lured and forced into becoming more active during the collective phases; hence, the risk of group think and social loafing is reduced. The increased activity in collective phases occurs partly because people have prepared things to present, and partly because others expect everyone to present their new information and ideas (Döös & Backström, 1997). Research on the human brain function provides an additional reason to facilitate both the individual and collective parts of the creative process. The human brain works in two competing, mutually exclusive ways: one is associated with mechanical reasoning, while the other involves social reasoning (Jack et al., 2013). Therefore, when there is a need to reason about physical objects, it is good for a group working on a task to take breaks from collaborating with others and to use the brain network for social reasoning; this helps them use their brain network for mechanical reasoning as well.

In sum, there are three aspects, with an individual and a group perspective for each giving a total of six outposts. Three outposts use an individual perspective: autonomy, divergence, and exploration; these are especially important for modification of structures, and thus learning, adaptation, and transformation. The other three outposts involve a group perspective: integration, convergence, and exploitation; these are critical for reinforcement of structures and thus stability. If the group perspective stops being used, the group will disintegrate, and if the individual perspective is not utilized, stagnation will ensue. How to use the model to describe and facilitate different dynamics in a production system is further developed in Fundin, Backström, & Johansson (2018). These six outposts are to be complemented by three tasks performed by the managers.

The Management: How to Facilitate Creative Group Processes

To be able to use the GroPro as a support in the creative group process, the group members must be informed about the six outposts described above and receive training to use them. For example, through harnessing the model to analyze and improve managerial meetings by asking questions such as: Do we have a balance between divergence and convergence in our utterances? If there is too much convergence, ask people to autonomously use their individual knowledge and experiences, and to explore new knowledge in time for the next meeting. If there is too much divergence, integrate the participants by reminding them about the group’s vision, norms, and values. Then, remind them of the meeting’s importance in terms of reaching a result that can be exploited in the work. More examples on how to organize for integrated autonomy and an interaction including both divergence and convergence is given by Backström (2013).

In addition to the training, GroPro includes three managerial tasks, but before describing them, some words on leadership are needed. A common way to differentiate between management and leadership is to say that the manager’s job is to plan, organize and

coordinate, while the leader’s job is to inspire and motivate. This implies that a manager can be external to the group, while a leader has to interact more closely with it. This article will use this discovery as a key difference: managers are external to the group, while leaders are internal. Of course, a manager may also be a member of a group and exercise leadership over parts of the group’s work.

The definition of leadership in complexity leadership theory is an interactive event in which knowledge and behavior change; thus, leadership is something that every member of a group can do (Lichtenstein et al., 2006). Hence, group members may take turns leading the

interaction, supported by the model with six outposts. The two drivers for leadership in the complexity leadership theory are the formation of a collective identity, and generating tension for individuals through which novel information can emerge. This distinction between the collective (unity and wholeness) and the individual (plurality and many parts) is central to the

10

understanding of emergence. This is in line with the six outposts from the model of interaction, including an individual and a group perspective, as explained above. The work of managers is often described as to plan, organize, and coordinate with a performance-oriented focus on production and adaptation to the current situation, and a development-oriented focus on generating new knowledge and solutions (McGill et al., 1992; Minzberg, 2009; Wallo et al., 2013). In this article, this plan-control type of management work is complemented by a team coaching oriented focus on enabling and affecting emergence and self-organization in groups of subordinates.

The team coaching oriented work of managers includes staffing (i.e., to assign group

members) and enabling (i.e., to give resources to the group and formulate external structures that organize the group’s work). Enabling is the managers’ construction of a container of external structures within which emergence occurs while the group is working. Furthermore, there is a possibility for managers to coach (i.e., to affect the group’s work from the outside). In this article, coaching does not refer to a kind of leadership, but rather a managerial task, since a non-member of the group may perform it.

These three managerial tasks are staffing, enabling, and coaching, together with the six outposts earlier described they form the GroPro model, as seen in Figure 1. In the next section these nine concepts will be used to integrate creativity research. This will also further develop the meaning of the concepts.

Integrating Creativity Research into the GroPro Model

The GroPro model is not a linear process model. It includes three tasks for the management: staffing, enabling, and coaching. Staffing and enabling start the group’s creative process, and may stay constant after that. Still, it is probably good for management to recurrently get in contact with the group to coach its work and see if improvements in staffing and enabling are necessary. Further, the model includes six outposts for the group to be creative: autonomy, integration, divergence, convergence, exploring, and exploiting. All of these are needed most of the time; sometimes one is more important, sometimes another. It is part of the group members’ self-leadership to discern when there is a need to focus on a certain outpost to increase it. The three tasks and six outposts of the GroPro model are all important for the group’s creativity, as shown in Figure 1. Let us look at what earlier creativity research has to say about each part of the model.

Staffing

Relatively stable individual properties of the members, such as expertise and

creative-thinking skills, are key to the group’s creativity, as shown by research using the componential perspective. Yet from the process perspective, used in this article, they are of less importance than the interactions between the members leading to emergence and the consequent

structural changes. An empirical study including nearly 500 individuals showed group creativity to be significantly correlated with both aggregated, individual creativity as well as group creativity-relevant processes, but a low incidence of group creativity-relevant

processes neutralizes the effect of a group high in creativity (Taggar, 2002). For example, the existence of creative groups alongside uncreative members in the experiment mentioned above (Bissola & Imperatori, 2011) is explained by a work process characterized by time awareness, goal orientation, task-oriented leadership, and effective communication. Job-relevant diversity is the only significant antecedent of team-level creativity and

innovation in the workplace that has to do with staffing according to a meta-analysis of 104 independent empirical research studies (Hülsheger, Anderson, & Salgado, 2009). Two different kinds of diversity have been examined. Job-relevant diversity has a slightly positive

11

significance for group creativity, probably due to the greater amount of skills and knowledge available in the process. On the other hand, background diversity (age, gender, and ethnicity) presents a slightly negative significance in the meta-study, perhaps because of

communication problems, which makes it harder to reach consensus.

Reaching consensus is vital to creating and implementing new group ideas. Thus, individual interpersonal competencies are probably important for group creativity; for example, the abilities of: active listening, empathy, sharing knowledge, experiences and ideas,

participating in generative dialogue, improvising in groups, and giving and receiving feedback (Yams, 2017).

Enabling

Enabling refers to the context: external structures imposed on the group by external forces. Managers must create structures that enable the group’s creativity (Peschl & Fundneider, 2014). For instance, managers decide the size of the group, may formulate tasks in a goal interdependent way, and they may give support to the group.

These three contextual variables have been significantly correlated with group creativity in a meta-analysis (Hülsheger et al., 2009). Team size decreases individual creativity, probably due to social loafing, but group creativity rises slightly. In general, larger groups have a greater amount of skills and knowledge to use in the creative process. Goal interdependence refers to the extent to which team members’ goals and rewards are related in such a way that each team member can only reach his/her goal if other team members also reach theirs. The importance of goal interdependence for group creativity may be due to it influencing interactions between team members, such that they become more cooperative and helpful (ibid.). Support for innovation includes expectations, approval, and practical aid for attempts to innovate.

The model of group dynamics used in this article distinguishes between enabling (the creation of external structures by the context or people outside of the group), and emerging (internal structures emerging in the interactions between group members). Vision, one of the more significant antecedents of team-level creativity in the meta-analysis by Hülsheger et al. (2009), is probably partly created and partly emergent. Vision is defined as “the extent to which team members have a common understanding of objectives and display high commitment to those team goals” (ibid., p. 1,131). For example, Hoegl, Gibbert, and Mazursky (2008) studied enabling and vision. They stated that a clearly specified and

inherently exciting project goal would foster innovation team performance and help the team to overcome barriers of will in the creative process. Further, managers may formulate

“aggressive goals” that are impossible to reach without radical innovation, and without interactions between different personnel categories (Yamamoto, 2017). Such desire to change the game formulated by managers can be highly motivating for creative groups.

Managers may also organize the group’s interactions. Three principally different

organizations have been distinguished in a study on the creative process of virtual teams (Nemiro, 2002). In the star-formed network, everyone is in contact with a key person (the hub or broker), but not with the other group members. This network structure has a negative effect on creativity (Leenders & Gabbay, 1999). The modular approach, whereby the work is divided up or distributed among group members, resulted from the reduced need for

interaction between team members, a negative influence on creativity. Lastly, the iterative approach seems best for creativity, whereby members “worked a little, presented those results to the team, got feedback, worked a little more, presented those results, got more feedback, and so on” (Nemiro, 2002, p. 79).

12 Coaching

The manager is here defined as external to the group. Still, there is often a need for the manager to get in contact with the group; for example, to make sure that the task is understood and to communicate changes about it. This is a delicate undertaking since emergent processes are very sensitive for external control. It is easy for group members to hand over the responsibility to a manager if there is an opportunity to do so. The concept of coaching is used here to describe the job of managers – to affect the group without taking over its task – since coaching seems to be a managerial style close to what is needed. A literature review of coaching, by McCarthy and Milner (2012), uses the definition of the Worldwide Association of Business Coaches (2007): “Business coaching is the process of engaging in meaningful communication with individuals in businesses, organizations, institutions or governments, with the goal of promoting success at all levels of the

organisation by affecting the actions of those individuals.” The review lists several issues for coaching managers, which is also vital for the GroPro task of coaching: a strong relationship, authentic listening, asking questions that prompt reflection, a strong focus on goal setting, constructive feedback, as low a degree of stress on positional power as possible, and confidentiality.

There has not been much research on coaching and creativity. A literature review on coaching and employee effectiveness by Shinde and Bachhav (2017) only revealed one reference. Mulec and Roth (2005) discovered that when managers coached their teams using forms of inquiry and guided questioning, this improved teams’ efficiency and creativity. Some studies with a process perspective have described how the facilitator may act to preserve the group’s creative work. In the book Group Genius: The Creative Power of Collaboration, Keith Sawyer uses the concept of “group flow” to describe when a group realizes its full creative potential and lists ten conditions for this to occur. Several of the conditions are in line with the issues for coaching managers, mentioned above; for example, an emphasis on goal setting by “establishing a goal that provides a focus of the team…but one that is open-ended enough for problem-finding creativity to emerge” (Sawyer, 2007, p. 45). The importance of close listening “when everyone is fully engaged – what improvisers call ‘deep listening’” in which members of the group “don’t plan ahead what [they are] going to say, but [their] statements are genuinely unplanned responses to what [they] hear” (ibid., p. 46).

Another condition to reach group flow is the need for the facilitator to leave control up to the group. For example, “People get into flow when they’re in control of their actions and their environment” and “Many studies have found that team autonomy is the top predictor of team performance.” (ibid., p. 49). Furthermore, equal participation of all members in the

interaction is important. “Group flow is more likely to occur when all participants play an equal role in the collective creation of the final performance. Group flow is blocked if…one person dominates.” (ibid., p. 50).

Relationships: A Duality of Autonomy and Integration

The autonomy-integration duality has to do with the group members’ relationship to the group and its task. Autonomy means that group members are able to, know how to, and are willing to think and act freely in relation to it, while integration means that group members submit to the collective and its task. Autonomy-integration is a complex structure that is present when the group exists; members always have a relationship to the group and the task. Autonomy-integration partially has to do with identity. In different situations one might identify more with an individualistic and autonomous style, or a team-oriented and integrated

13

approach. Both the individualistic (Goncalo & Staw, 2006; Janssen & Huang, 2008) and team orientations (Hirst, van Dick, & van Knippenberg, 2009) have been associated with

creativity.

When a group member is mostly in the autonomous outpost, he/she fulfills the assumptions of the componential theory. The link between creativity and an individual factor is often complex because it is shaped by the contextual variables, and different parts of the creative process have different antecedents (Anderson et al., 2014). However, research has shown that creativity is connected to self-esteem or self-efficacy, especially creative self-efficacy

(Tierney & Farmer, 2002) and motivation, and a combination between intrinsic and prosocial motivation in particular (Grant & Berry, 2011).

Cohesion, which is close to integration, is one of the most studied team characteristics, and is significantly related to group creativity according to a meta-analysis by Hülsheger et al. (2009). It refers to the group members’ commitment to the group and their desire to maintain group membership. Strong personal attraction among members creates a safe climate to be autonomous and challenge the structures of the collective (West & Wallace, 1991). Several studies have demonstrated that participative safety (the combination of participation in decision-making and intragroup safety) has a significant relationship to creativity (Hülsheger et al., 2009). A supportive cooperative work atmosphere, where group members help one another and collaborate, increases group creativity (Amabile et al., 1996; Keller, Julian, & Kedia, 1996). Furthermore, integration into the task (a commitment to the objectives of the group) is associated with creativity (West & Anderson, 1996). Task orientation (a shared concern for high-quality task performance) is one of the significant antecedents in the meta-analysis by Hülsheger et al. (2009).

Information Flow: A Duality of Divergence and Convergence

The divergence and convergence duality has to do with the information flow in the group, which is the process of sharing information, ideas, knowledge, and experiences. Divergence stands for ambiguity, and the inflow of new information and ideas into the group interaction. Divergence is based on different group members having distinct information, expertise, and experiences to share, as well as a willingness to share the information. Convergence implies a process whereby divergent information is correlated in interactions between group members so that they come to have an increasingly shared understanding, a dominant interpretation, or at least an understanding of each other’s information. The American psychologist Joy Paul Guilford created one of the earliest models of creativity, and distinguished between

convergent and divergent thinking (Guilford, 1956). According to him, convergent thinking usually leads a person to arrive at one conclusion or answer that is regarded as unique, and thinking is channeled or controlled in the direction of that answer. In divergent thinking, on the other hand, there is much searching or going off in various directions. For instance, in problem-solving, there must be – and usually is – some divergent thinking or searching, as well as ultimate convergence toward a solution.

Divergence is so central to creativity that it is sometimes measured by the amount and degree of novelty of ideas. The potential for divergence is formed by job-relevant diversity

(staffing), thinking autonomously (autonomy), being motivated and feeling safe to share new ideas with the group (integration), and scouting for new information (exploring). Individual brainstorming is an example of a common process to receive a lot of divergence. Interaction with other group members is critical for diversity; research has shown that the amount of new notions produced by one member increases when he/she has access to other members’ ideas (Nijstad & Stroebe, 2006).

14

The extent to which group members share information, ideas, knowledge, and experiences with each other, possibly a combination of divergence and convergence, is important for group creativity. Hülsheger et al. (2009) demonstrated that internal communication is a significant antecedent. For example, team reflection was the strongest antecedent to team innovation in a study of 136 primary care teams (Somech, 2006). In an investigation of 100 teams, team reflexivity was significantly correlated with rated innovativeness (Tjosvold, Tang, & West, 2004). Moreover, groups that engage in interactions between members to integrate knowledge have an increased ability to adaptively improve their work (Okhuysen & Eisenhardt, 2002).

An action research project aiming at increased team competence found that internal

communication resulted in increased creativity (Backström, Moström Åberg, et al., 2013). In this study, supervisors were trained in three theories about internal communication: balanced communication (Losada & Heaphy, 2004), dialogue competence (Wilhelmson, 2006), and improvisation (Johnstone, 1979). In particular dialogue competence, characterized by the following four abilities (Backström, Moström Åberg, et al., 2013, p 22), closely resembles convergence (2 and 3 in the list) and divergence (1 and 4):

1. Closeness to the individual perspective: The ability to contribute to knowledge formation by speaking in one’s own voice and asserting reflected experiences relevant to the topic under discussion.

2. Closeness to the perspectives of others: The ability to listen carefully and with curiosity to others’ narratives while earnestly trying to understand what is meant. 3. Distance from the individual perspective: The ability to think of one’s own truths as eventually being prejudiced, as well as to critically reflect on

self-perceptions.

4. Distance from the perspectives of others: The ability to critically reflect with integrity on assertions made by others based on one’s own experience and knowledge. The outcomes of processes of convergence are correlated with creativity. For example, Hülsheger et al. (2009) showed that vision (a common understanding of objectives and a display of high commitment to these goals) is a significant antecedent; the understanding of and commitment to the vision emerge in interactions between group members as a

convergent process, at least partially. Furthermore, shared mental models were significantly associated with creativity in a study of 161 teams (Santos, Uitdewilligen, & Passos, 2015).

Action: A Duality of Exploring and Exploiting

The exploring and exploiting duality has to do with the external actions of the group and its members that go beyond the group. Exploring is the search for opportunities, knowledge, and information to use in the creative processes; for instance, to explore ideas or solutions from other contexts or to experiment, test, and try out different ideas. Exploiting implies

harnessing the group’s resources to create value; that is, to present, argue for, and implement solutions formed during the creative process.

Hülsheger et al. (2009) revealed that external communication is a significant antecedent of team creativity; it includes communication with people outside of the group (Ancona & Caldwell, 1992; Keller, 2001), communication with partners (Wong, Tjosvold, & Su, 2007), the use of external knowledge sources (McAdam, O’Hare, & Moffet, 2008), and the

formation of networks of communication (Perry-Smith & Shalley, 2003).

15

ideas on the elements that are important for exploiting: mutual performance monitoring (whereby group members keep track of fellow members to ensure that everything is running as expected) and back-up behavior (which provides other members with resources when it is apparent that a member is failing to reach the goals).

Results from the Use of Earlier Versions of GroPro

The GroPro model, with its different parts, has been under development for almost ten years. The assumption that an internal structure will emerge in interactions between employees has been tested. Groups of interacting employees can develop work goals of their own that are common to group members, but divergent to the goals suggested by the organization

(Backström & Olsson, 2010). The concept of “organizing talk” was coined and used, both as a goal and as the principle notion in the design process, in a successful intervention where a pharmacy was re-engineered to enable organizing talk while working (Backström &

Söderberg, 2007).

One study posited that a dynamic balance between autonomy and integration is good for sustainability (Backström, 2004). Integrated autonomy was coined to describe an

organization where employees simultaneously integrated into their work group and were allowed to autonomously make decisions about a lot of their work. An intervention study (Backström, Moström Åberg, et al., 2013; Wilhelmson et al., 2015) was designed based on the concepts of organizing talk and integrating autonomy; the findings revealed that the intervention increased the attractiveness of the workplace significantly.

Re-analyzing this intervention from the perspective of human interaction dynamics

(Backström, 2013) was one of the inputs behind the HID-model (Hazy & Backström, 2013), which is the basis for the six outposts of GroPro. These six outposts have provided the structure with a new, more appreciated way of obtaining feedback results from an Innovation Management Self Audit Tool (Cedergren et al., 2017). The six outposts have also been tested in a quasi-experimental design and lead to increased group creativity (Backström &

Söderberg, 2016). In this experiment half of the groups used GroPro and half did not. The mean value difference of promotion and use of ideas was significantly higher in the GroPro groups, which implies that ideas were more often observed and used by other members of these groups. Of the 260 ideas in the GroPro groups, 87% were observed and used by others, compared with 79% of the 344 ideas in the free groups.

In recent years, the GroPro model has been used in training in innovation management to reveal a hierarchical slice of municipalities and local governments, in creativity among candidate students, and in entrepreneurship for doctoral students. Several action research projects have used questionnaires developed according to the six outposts of the GroPro model for process evaluation (Berglund, Backström, & Bellgran, In work; Blackbright, Johansson, Backström, Cedergren, & Schaeffer, In work; Olsson, 2015; Schaeffer, Backström, Johansson, Cedergren, & Blackbright, June 2017).

Discussion

“Against the ruin of the world, there is only one defense – the creative act”

This quote from the American poet Kenneth Rexroth highlights the importance of creativity to find solutions to the challenges that threaten the world of today. The GroPro model is designed to have relevance for both academy and practitioners in their work to understand and increase group creativity, as mentioned in the introduction of this article. For

practitioners it describes a way to enable and facilitate group creativity. Experiences so far indicates that GroPro is simple and practical enough for practitioners to use in their work. The structure of the model, see figure 1, with three tasks for managers, three tasks to

16 in mind and use while working on a creative task.

For academics it is detailed and broad enough to integrate creativity research. The model make it possible to understand why variables shown to increase group creativity do so. All antecedents to group creativity found in literature while working with the article can be categorized using the model, as is done under the heading Integrating Creativity Research into the GroPro Model. Further, it complex enough to include both the individuals and the group, and their dynamic relations, which is unusual and asked for (Anderson et al., 2014, Cronin et al., 2011), and which make it possible to understand why the creativity of the group can be both more and less than the sum of the creativity of its members.

Models Similar to GroPro

The connection to GroPro and theories like the model for the study of group dynamics of Cronin, et al. (2011), the model of morphogenesis (Archer, 1995), the human interaction dynamics model (Hazy & Backström, 2013), and the complexity leadership theory (Lichtenstein et al., 2006) have already been described under the heading The Central Theories behind the GroPro Model. This section will highlight some models of group’s creativity, which have similarities to the GroPro model.

A model formulated by Jiang and Zhang (2014) is somewhat similar to GroPro in that it is stresses emergence as the most important feature of the group creativity system, in relation to theories of complex systems. They also divided individual actions and the emergent

collective organizing structures into three levels: creative thinking, creative action, and creative outcomes. Two of the levels are similar to those of GroPro: creative thinking and information flow, respectively creative action and action. But the creative outcomes are not part of the GroPro model, which instead sees relationships of the group members as too important for the social dynamic to be ignored. Relationships are included in another model with similarities to GroPro, formulated by Tang et al. (C. Y. Tang, 2014; Shang, Naumann, & von Zedtwitz, 2014). As is the case with autonomy, they discuss ego identification (the extent to which individual group members see themselves as different from the other members in their thoughts, feelings and behavior). Likewise, with integration, Tang et al. (2014) used the concept of team identification (the perception of belonging to a group). Similar to divergence and convergence, Tang et al. (2014) stated that knowledge sharing occurs in two ways: by combining pieces of existing knowledge, and through the exchange of knowledge and information. Furthermore, divergence (generating options) and convergence (selecting options and creating solution) are important steps in models of creativity (Guilford, 1956) and the group’s creative process (Leonard and Swap, 1999).

Conclusion

The GroPro model has advantages compared to other ones. It integrates all phenomena relevant to group creativity, it is complex enough to consider the relationships between the individual and the collective, and it is simple enough to easily explain it to others and use as a practical guide in one’s own interactions with others. However, the model is still young and has to be further evaluated and tested in different situations.

The goal, which is to design a model detailed and complex enough for researchers studying group creativity, but also simple and practical enough for practitioners to use in their work to enable and affect group creativity, seems to be fulfilled, as shown by the previously

mentioned examples of how GroPro has been employed so far.

One thing is for certain: an organization wastes effort by only examining individual

creativity, since individuals normally have to do their creative work in groups. When group processes fail, it does not matter how creative the individual members are. With a good

17

collective process, any group can be creative. The author encourages both academics and practitioners to focus more on the group process.

References

Amabile, T. M. (1982). Social psychology of creativity: A consensual assessment technique. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43(5), 997–1013. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.43.5.997

Amabile, T. M., Conti, R., Coon, H., Lazenby, J., & Herron, M. (1996). Assessing the work environment for creativity. Academy of Management Journal, 39(5), 1154–1184. doi:10.2307/256995

Ancona, D. G., & Caldwell, D. F. (1992). Demography and design: Predictors of new product team performance. Organization Science, 3(3), 321–341. doi:10.1287/orsc.3.3.321

Anderson, N., Potocnik, K., & Zhou, J. (2014). Innovation and creativity in organizations: A state-of-the-science review, prospective commentary, and guiding framework. Journal of Management, 40(5), 1297–1333. doi:10.1177/0149206314527128

Archer, M. S. (1995). Realist social theory: The morphogenic approach. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Backström, T. (2004). Collective learning: A way over the ridge to a new organizational attractor. The Learning Organization, 11(6), 466–477. doi:10.1108/09696470410548827 Backström, T. (2013). Managerial rein control and the Rheo task of leadership. Emergence:

Complexity & Organization, 15(4), 76–90.

doi:10.emerg/10.17357.7d3a4e1969b456a504da2f4158706f05

Backström, T. (2017). Solving the quality dilemma: Emergent quality management. In T. Backström, A. Fundin, & P. E. Johansson (Eds.), Innovative quality improvements in operations: Introducing emergent quality management (pp. 151-166). New York: Springer International Publishing.

Backström, T., Hagström, T., & Göransson, S. (2013). Communication as a mechanism for cultural integration. Nonlinear Dynamics, Psychology, and Life Sciences, 17(1), 87–106. Backström, T., Moström Åberg, M., Köping Olsson, B., Wilhelmson, L., & Åteg, M. (2013).

Manager’s task to support integrated autonomy at the workplace: Results from an intervention. International Journal of Business and Management, 8(22), 20–31. doi:10.5539/ijbm.v8n22p20

Backström, T., & Olsson, B. K. (2010). Den hållbara och kreativa organisationen. In A. Härenstam & E. Beijerot (Eds.), Sociala relationer i arbetslivet (pp. 133-156). Lund: Glerups.

Backström, T., & Söderberg, I. (2007). Organiseringens samtal - om hållbar utformning av organisation och rum. Arbetsliv i omvandling, 6, 1–33.

Backström, T., & Söderberg, T. (2016). Self-organisation and group creativity. Journal of Creativity and Business Innovation, 2, 65–79.

Bahskar, R. (1989). Reclaiming reality: A critical introduction to contemporary philosophy. London: Verso.

Berglund, R., Backström, T., & Bellgran, M. (In work). Psychosocial risk reduction by engineers and technicians in a manufacturing company. In work.

Bissola, R., & Imperatori, B. (2011). Organizing individual and collective creativity: Flying in the face of creativity clichés. Creativity and Innovation Management, 20(2), 77–89. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8691.2011.00597.x

Blackbright, H., Johansson, P. E., Backström, T., Cedergren, S., & Schaeffer, J. (In work). The discontinuity effect on IMA's use and utilization.

Bledow, R., Frese, M., Anderson, N., Erez, M., & Farr, J. (2009). Extending and refining the dialectic perspective on innovation: There is nothing as practical as a good theory; nothing

18

as theoretical as a good practice. Industrial and Organizational Psychology: Perspectives on Science and Practice, 2(3), 363–373. doi:10.1111/j.1754-9434.2009.01161.x

Burke, C. S., Stagl, K. C., Salas, E., Pierce, L., & Kendall, D. (2006). Understanding team adaptation: A conceptual analysis and model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(6), 1189– 1207. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.91.6.1189

Cedergren, S., Backström, T., Blackwater, H., Johansson, P., & Wikström, A. (2017, June). A new survey instrument for assessing the innovation climate. Paper presented at the ISPIM’17, Vienna, Austria.

Cronin, M. A., Weingart, L. R., & Todorova, G. (2011). Dynamics in groups: Are we there yet? The Academy of Management Annals, 5(1), 571–612. doi:10.1080/19416520.2011.590297

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). Creativity. New York: Harper Collins Publishers.

Drazin, R., Glynn, M. A., & Kazanjian, R. K. (1999). Multilevel theorizing about creativity in organizations: A sensemaking perspective. Academy of Management Review, 24(2), 286– 307. doi:10.2307/259083

Döös, M., & Backström, T. (1997). The RIV Method: A participative risk analysis method and its application. NEW SOLUTIONS: A Journal of Environmental and Occupational Health Policy, 7(3), 53–61. doi:10.2190/ns7.3.i

Fundin, A., Backström, T., & Johansson, P. E. (2018). Exploring the emergent quality management paradigm. Paper presented at the Excellence summit, Gothenburg, Sweden. Glăveanu, V. P. (2010). Paradigms in the study of creativity: Introducing the perspective of

cultural psychology. New Ideas in Psychology, 28(1), 79–93. doi:10.1016/j.newideapsych.2009.07.007

Goncalo, J. A., & Staw, B. M. (2006). Individualism-collectivism and group creativity. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Process, 100(1), 96–109. doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2005.11.003

Grant, A. M., & Berry, J. W. (2011). The necessity of others is the mother of invention: Intrinsic and prosocial motivations, perspective taking, and creativity. Academy of Management Journal, 54(1), 73–96. doi:10.5465/amj.2011.59215085

Guilford, J. P. (1956). The structure of intellect. Psychological Bulletin, 53(4), 267–293. Haken, H. (1996). Principles of brain functioning. A synergetic approach to brain activity,

behavior and cognition. Berlin: Springer.

Hargadon, A. B., & Bechky, B. A. (2006). When collections of creatives become creative collectives: A field study of problem solving at work. Organization Science, 17(4), 484– 500. doi:10.1287/orsc.1060.0200

Hazy, J. K., & Backström, T. (2013). Human interaction dynamics (HID) – An emerging paradigm for management research. Emergence: Complexity & Organization, 15(4), I–ix. Hirst, G., van Dick, R., & van Knippenberg, D. (2009). A social identity perspective on

leadership and employee creativity. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 30(7), 963–982. doi:10.1002/job.600

Hoegl, M., Gibbert, M., & Mazursky, D. (2008). Financial constraints in innovation projects: When is less more? Research Policy, 37(8), 1382–1391. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2008.04.018 Huang, C. C. (2009). Knowledge sharing and group cohesivness on performance: An empirical

study of technology R&D teams in Taiwan. Technovation, 29(11), 786–797. doi:10.1016/j.technovation.2009.04.003

Hülsheger, U. R., Anderson, N., & Salgado, J. F. (2009). Team-level predictors of inovation at work: A comprehensive meta-analysis spanning three decades of research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(5), 1128–1145. doi:10.1037/a0015978

Jack, A. I., Dawson, A. J., Begany, K. L., Leckie, R. L., Barry, K. P., Cicca, A. H., & Snyder, A. Z. (2013). fMRI reveals reciprocal inhibition between social and physical cognitive

19

domains. NeuroImage, 66, 385–401. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.10.061

Janssen, O., & Huang, X. (2008). Us and me: Team identification and individual differentiation as complementory drivers of team members citizenships and creative behaviors. Journal of Management, 34(1), 69–88. doi:10.1177/0149206307309263

Jiang, H., & Zhang, Q.-p. (2014). Development and validation of team creativity measures: A complex systems perspective. Creativity and Innovation Management, 23(3), 264– 275. doi:10.1111/caim.12078

Johnstone, K. (1979). Impro, improvisation and the theatre. London: Faber and Faber.

Keller, R. T. (2001). Cross-functional project groups in research and new product development: Diversity, communicatons, job stress, and outcomes. Academy of Management Journal, 44(3), 547–555. doi:10.5465/3069369

Keller, R. T., Julian, S. D., & Kedia, B. L. (1996). A multinational study of work climate, job satisfaction, and the productivity of R&D teams. !EEE Transactions in Engineering Management, 43(1), 48–55. doi:10.1109/17.491268

Kozlowski, S. W. J., & Bell, B. S. (2003). Work groups and teams in organizations. In W. C. Borman, D. R. Ilgen, & R. J. Klimoski (Eds.), Handbook of psychology: Industrial and organizational psychology. London: Wiley.

Kratzer, J., Leenders, R. T. A. J., & van Engelen, J. M. L. (2006). Managing creative team performance in virtual environments: An empirical study in 44 R&D teams. Technovation, 26(1), 42–49. doi:10.1016/j.technovation.2004.07.016

Kurtzberg, T. R., & Amabile, T. M. (2001). From Guilford to creative synergy: Opening the black box of team-level creativity. Creativity Research Journal, 13(3-4), 285–294. doi:10.1207/s15326934crj1334_06

Langley, A., Smallman, C., Tsoukas, H., & van de Ven, A. H. (2013). Process studies of change in organization and management: Unveiling temporality, activity, and flow. Academy of Management Journal, 56(1), 1–13. doi:10.5465/amj.2013.4001

Leenders, R. T. A. J., & Gabbay, S. M. (1999). CSC: An agenda for the future. In R. T. A. J. Leenders & S. M. Gabbay (Eds.), Corporate social capital and liability (pp. 483– 494). Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Leonard, D. A., & Swap, W. C. (1999). When sparks fly: Igniting creativity in groups. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Lewis, M. W. (2000). Exploring paradox: Toward a more comprehensive guide. Academy of Management Review, 25(4), 760–776. doi:10.2307/259204

Lichtenstein, B. B., Uhl-Bien, M., Marion, R., Seers, A., Orton, J. D., & Schreiber, C. (2006). Complex leadership theory: An interactive perspecive om leading in complex adaptive systems. Emergence: Complexity & Organization, 8(4), 2-12.

Losada, M., & Heaphy, E. (2004). The role of positivity and connectivity in the performance of business teams. American Behavioral Scientist, 47(6), 740–765. doi:10.1177/0002764203260208

March, J. G. (1991). Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organization Science, 2(1), 71–87. doi:10.1287/orsc.2.1.71

McAdam, R., O'Hare, T., & Moffet, S. (2008). Collaborative knowledge sharing in composite knew product development: An aerospace study. Technovation, 28(5), 245–256. doi:10.1016/j.technovation.2007.07.003

McCarthy, G., & Milner, J. (2012). Managerial coaching: challenges, opportunities and training. Journal of Management Development, 32(7), 768–779. doi:10.1108/jmd-11-2011-0113

McGill, M. E., W, S. J., & Lei, D. (1992). Management practicies in learning organizations. Organizational Dynamics, 21(1), 5–17. doi:10.1016/0090-2616(92)90082-X

20

Hogg & T. S. Tindale (Eds.), Blackwell handbook of social psychology: Group processes. Oxford: Blackwell.

McGrath, J. E., Arrow, H., & Berdahl, J. L. (2000). The study of groups: Past, present and future. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 4(1), 95–105. doi:10.1207/S15327957PSPR0401_8

Minzberg, H. (2009). Managing. San Francisco CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc.

Mulec, K., & Roth, J. (2005). Action, reflection, and learning coaching in order to enhance the performance of drug development project management teams. R&D Management, 35(5), 483–491. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9310.2005.00405.x

Nemiro, J. E. (2002). The creative process in virtual teams. Creativity Research Journal, 14(1), 69–83. doi:10.1207/s15326934crj1401_6

Nijstad, B. A., & Paulus, P. B. (2003). Group creativity: Common themes and future directions. In P. B. Paulus & B. A. Nijstad (Eds.), Group creativity: Innovation through collaboration (pp. 326-340). New York: Oxford University Press.

Nijstad, B. A., & Stroebe, W. (2006). How the group affects the mind: A cognitive model of idea generation in groups. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10(3), 186–214. doi:10.1207/s15327957pspr1003_1

Okhuysen, G. A., & Eisenhardt, K. M. (2002). Integrating knowledge in groups: How formal interventions enable flexibility. Organization Science, 13(4), 370–386. doi:10.1287/orsc.13.4.370.2947

Olsson, B. (2007). Languages for creative interaction: Descriptive language in heterogeneous Groups. Paper presented at the The 10th European conference on creativity and innovation, ECCI-X, Copenhagen.

Olsson, B. K. (2015). Innovation Pleasure in Sörmland County-opportunity for individuals, businesses and society A Follow-up research project during implementation of The Katrineholms Innovationsmodell, KINVO: Evaluative Final Report.

Paulus, P. B., & Nijstad, B. A. (2003). Group creativity: An introduction. In P. B. Paulus & B. A. Nijstad (Eds.), Group creativity: Innovation through collaboration (pp. 3-11). New York: Oxford University Press.

Perry-Smith, J. E., & Shalley, C. E. (2003). The social side of creativity: A static and dynamic social network perspective. Academy of Management Review, 28(), 89–106. doi:10.2307/30040691

Peschl, M. F., & Fundneider, T. (2014). Designing and enabling spaces for collaborative knowledge creation and innovation: From managing to enabling innovation as socio-epistemological technology. Computers in Human Behavior, 37, 346–359. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2012.05.027

Rubenson, D. L., & Runco, M. A. (1995). The psycheconomic view of creative work in groups and organizations. Creativity and Innovation Management, 4(4), 232–241. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8691.1995.tb00228.x

Saad, G., Cleveland, M., & Ho, L. (2015). Individualism-collectivism and the quantity versus quality dimensions of individual and group creative performance. Journal of Business Research, 68(3), 578–586. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.09.004

Santos, C. M., Uitdewilligen, S., & Passos, A. M. (2015). Why is your team more creative than mine? The influence of shared mental models on intra-group conflict, team creativity and effectiveness. Creativity and Innovation Management, 24(4), 645–658. doi:10.1111/caim.12129

Sawyer, R. K. (2005). Social emergence: Societies as complex systems. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sawyer, R. K. (2007). Group genius. The creative power of collaboration. New York: Basic Books.