Design impulses: Artefacts, Contexts and Modes of

Activities

Mette Agger Eriksen

Arts and Communication, Malmø University, Sweden [mette.agger2k3.mah.se]

Per Linde

Arts and Communication, Malmø University, Sweden [per.linde@k3.mah.se]

Keywords:

Artefacts, contexts and modes of activities – interdisciplinary, participatory design

Abstract

Design-artefacts are not interpreted in isolation but in various contexts and as part of various modes of activities. This paper aims to provide a broad methodological framework

emphasizing careful combinations of artefact, context and mode of activity to create powerful design impulses in interdisciplinary it-design research teams. Critical evaluation of examples from the project PalCom: A new perspective on ambient computing serve to illustrate the effects and dynamics as well as challenges generated through such careful interventions. We focus on interdisciplinary and participatory design in the domain of hand surgery

rehabilitation, which is used to inform and challenge the overall design of an open software architecture for ‘palpable computing’ within the PalCom project. Four typical design artefacts – ‘Native’ artefacts, Fieldcards, Mock-ups and Prototypes – and their use in different contexts as part of different modes of activities are discussed to draw out the design impulses they provided for the ongoing design work in the project. The paper concludes by discussing the possibilities and difficulties of providing constructive design impulses by carefully manipulating combinations of artefacts, contexts and modes of activities.

1 Introduction

Artefacts drive design. Sketches, props, samples, mock-ups, prototypes, objet-trouvé – capture and embody ideas; they represent, translate, inspire, and shape the often evasive artefact-under-design; they facilitate interdisciplinary collaboration by both, fostering collective imaginations and giving concrete form or anchors to flighty and highly complex ideas; they help communicate the outcomes of design efforts. But artefacts must be brought to life in concrete situations, and where and how material artefacts are used matter.

Artefacts-in-context highlight the inseparability of social, cultural and material practices and the objects we design and design with. Architect, industrial designer or software developer – all designers must anticipate and design for future use. Design is an inescapably socio-material, moral as well as aesthetic activity. Emplacing artefacts in different contexts and changing the mode of engagement with them enables conscious, multimodal, analytic, reflective, and creative engagement with multiple dimensions of innovation. However, as we show some artefacts are more easily emplaced than others, and we argue that careful interventions and combinations of Artefacts, Contexts and Modes of activities can provide strong design impulses.

After a summary of our background, we introduce and position a methodological framework, before we ‘exhibit’ a series of examples from our work, practically exemplifying use of the framework. In the examples three different types of artefacts (Fieldcards, Mock-ups and Prototypes) have been used in different contexts and exposed to different modes of activities. In the Discussion we make five statements based on an evaluation and comparison of the examples, which describe the effects of these manipulations and for example highlight the importance of carrying out some of the design work in the physical settings, where the technologies being designing, are intended to be used. Through these statements we discuss the main rewards and challenges of encouraging interdisciplinary collaborative design and

interpretation of artefacts through careful combinations of artefact, context and mode of activity.

2 Background

The authors combine interaction design expertise with an ethnographic perspective and have worked as researchers/designers in several large and small European long-term IT design and research projects. We are currently collaborating with colleagues in twelve different institutions and commercial organizations from six different countries in a project called PalCom: A new perspective on ambient computing. The ca 60 person strong team is highly interdisciplinary. There are many areas of expertise, many different ways of working, and many participants are not designers by trade but computer scientists, ethnographers, or sociologists. The project has a strong participatory design (PD) approach and involve future users throughout the design process (landscape architects, medical staff, women and their families and friends from a maternity ward, personnel and patients at a hand surgery

rehabilitation clinic, and emergency services staff). (e.g. see Kyng et al, 1991; Bødker, 2004) In this paper we discuss examples from our collaboration with staff and patients at a hand surgery clinic at Malmö University Hospital in Sweden.

The PalCom project is concerned with the design of an open software architecture that supports the use of ambient computing. (e.g. see Aarts, 2003)Ambient computing refers to the fact that computation is increasingly embedded in small and large devices (bio-monitors, mobile telephones, cars) and dependent on digital services and resources (connectivity, storage, location tracking, sensors) embedded in environments. However, while computing is becoming increasingly ubiquitous, its ‘immateriality’ makes it hard for people to utilize its potential. Palpable computing is a new design initiative that envisages ubiquitous

technologies whose affordances are clearly available to the human senses, or ‘palpable’, and therefore more easily appropriated. Palpable computing will support the practices people use to notice and understand how machines ‘sense’ their context, help them intervene if machine ‘decisions’ are inappropriate, and allow them to perceive, creatively exploit and combine the affordances of computing technologies. (PalCom: www.ist-palcom.org)

This infrastructural and futuristic design brief poses a number of additional design challenges. Most importantly, to design an open software architecture that productively anticipates future practice, prospective users and designers need some hands-on experience of future services and devices that will run on it. Since these do not exist, the PalCom team needs to design them. This in itself requires a participatory design process and is difficult. To engage the imagination and practical creativity of the everyday users – landscape architects, healthcare personnel and patients – in the design of the architecture, enough functionality and ‘realism’ for the services and devices running on it has to be achieved. Yet, because these services and devices are mainly a means to the ‘bigger’ end of designing the software architecture, this ‘traditional’ participatory design process has to be embedded in the primary –

infrastructurally oriented – participatory design process (Büscher et al., forthcoming). As a result, several activities run in parallel: Architectural design, design of services and devices to exemplify use of and run on the software architecture (henceforth referred to as ‘application prototype design’), analysis, emergence, and ‘design’ of future practices as well as

conceptual framings of palpable computing.

The purpose of this paper, however, is to provide a broad methodological framework, supporting complex design processes like the one outlined above. The overall framework is also based on other previous work e.g. carried through within the two European disappearing-computer projects, WorkSpace and Atelier. (WorkSpace & Atelier). To make the framework concrete we are drawing on a few, tentative examples from one application prototype design thread of the first two years in the PalCom project – the design thread of supporting hand surgery rehabilitation.

3 Methodological Framework: Artefact, Context and

Mode of Activity

The methodological framework introduced in this section emphasizes careful integration of both Artefact, Context and Mode of Activity as important parts of creating a fruitful

Interdisciplinary collaborative design practice.

The three terms in Figure 1 carry the following meanings:

‘Artefact’ covers the physical design materials and resources used to support and inform interdisciplinary collaborative design work – our examples are quite typical for IT- and interaction-design: ‘Native’ artefacts (e.g. ‘old’ technologies), Fieldcards, Mock-ups and Prototypes. ‘Context’ covers the physical space or environment in which interdisciplinary activities take place.

It also includes people - the participants of different professions.

‘Mode of Activity’ covers the social as well as practical awareness of participants about the aim of a session as well as the practical methods by which to achieve it.

Figure 1 - Artefacts, Contexts and Modes of Activities in interdisciplinary collaborative design practice.

Within Participatory Design and related design fields, a range of methods of utilizing artefacts have been devised to support interdisciplinary collaboration. (e.g. Kyng et al, 1991; Bødker, 2004). Some of these practical methods will be mentioned in relation to the examples presented below.

More generally the use of physical materials and representations e.g. called

Hands-on-the-future (Ehn et al, 1991), Probes (Gaver et al, 1999), MAKE-tools (Sanders et al,1999), Things-to-think-with (Brandt, 2001), Material Catalysts (Capjon, 2005) also show that it is

widely accepted within design-oriented (research) fields that design Artefacts play an important role, foster and encourage engagment in interdisciplinary dialogue and collaboration, and help inform design in an ongoing process.

Several of the authors mentioned above refer to Ehn’s notion of ‘language games’, based on the concept introduced by Ludwig Wittgenstein (Ehn, 1988), and Star’s notion of ‘boundary

objects’. (Star, 1989), and the framework provided here also relate to these concepts.

The concept of boundary object cover Artefacts (in a broad sense) that work as common points of reference between different communities of practice, helping them to build a shared understanding and shared interests. The different communities interpret the artefacts or boundary objects differently, and it is an acknowledgement and discussion of these differences that enables the shaping of a shared understanding. It should for example be clear why a physical model or a piece of fieldwork may serve as boundary objects, or why some are only boundary objects for more specialized professional communities. Furthermore the Artefacts should be plastic and adjustable to serve as objects of translation satisfying various concerns at the same time and over time.

The idea of language-games (or overlapping communities of practice) focuses on how we discover and construct our world, and language as action is understood as our use of it. Again different communities of practice have different language-games, and artefacts or objects often play a fundamental role in such language-game.

In participatory and interdisciplinary design users and designers of different original professions get related via shared experiences in common design language-games, where design artefacts like Fieldcards, Mock-ups and Prototypes can get the role as ‘boundary objects’. An important competence of the designer is the ability to prepare for this shared design language-game that makes sense to all participants, making the interaction and mediation between different language-games possible.

The two concepts are important for understanding the role of artefacts in a socio-material perspective also in interdisciplinary collaborative design practice, but they do not have a strong emphasis on the role of the physical context. To explore this circle of the framework, a recent literature search on the role of the ‘context’ in it-related publications, indicate that the contexts explored and described very often refer to the specific ones of end-users or the settings or network in which e.g. a proposed system or mobile device is to be working and integrated. However, in recent years several authors have started to emphasise the role of the context more generally – e.g. Haraway’s ‘Situated Knowledge’ (Haraway, 1999) and Dourish’s ‘Where the Action is…’ (Dourish, 2001) which also are interesting in the

interpretation of the role of different types of contexts of design work, which is the focus of this paper. In some of our previous work e.g. within a former it-research project called Atelier (Atelier), we for example introduced the role of ‘place-making’ and ‘setting the scene’ as integrated parts of doing design work. These concepts also include considerations and attention to the ‘mode of the activities’ taking place in the interdisciplinary collaborative design practice, so the framework introduced in this paper, builds onto that work. (e.g. Ehn et al., forthcoming)

Based on work in another previous it-research project called WorkSpace (WorkSpace), we have also worked with a similar methodological framework like the one provided here. (Büscher et al, 2004) That framework include a triangular illustration relating ‘Means’ with ‘Environments’ with ‘Job-at-Hand’ via peoples ‘Practices’ in the middle.

There are clear overlaps between ‘Means’ and ‘Artefact’, likewise ‘Environments’ and ‘Context’, as well as ‘Mode of Activity’ and ‘Job-at-hand’ both surrounding ‘Practice’ and ‘Interdisciplinary collaborative design practice’ in the middle of the illustrations. However, the aim of that paper was to discuss practical ‘Ways of grounding imagination…’ in a Participatory Design It-research project for the purpose of developing and changing the work Practice of the specific use domain – in that case landscape architects. This was done through the presentation of three different PD methods/approaches (Bricolage, Prototyping experiments in-situ and Future Laboratories) discussed and compared through different specific examples where one of the three corners (Means – Environments – Job-at-hand) were ‘fixed’ for the purpose of exploring the others.

With the changing focus on the different corners the use of the Grounding-imagination-framework is slightly different, compared to what we do here, as we take different types of design Artefacts as our main focus and starting-points and examine them in some detail, for the purpose of exploring, exemplifying and reflecting upon the careful combinations of all the three outer circles for the purpose of affecting the middle of ‘Interdisciplinary collaborative design practice’. Furthermore we finalize by discussing the qualities and challenges of these different types of design Artefacts as part of the provided methodological framework.

4 Examples from the PalCom project

The following examples from the PalCom project are meant to illustrate various practical perspectives on the provided methodological framework.

To connect the different design levels within PalCom (practice, application prototypes, architecture, conceptual design), we are collaborating with professionals from a variety of different use sites and develop a range of application prototypes. The examples we exhibit below are from the design process around an application prototype for hand surgery rehabilitation, which involves interdisciplinary collaboration with staff and patients at the rehabilitation unit at the hand surgery clinic at Malmö University Hospital, led by the PalCom team at K3, Malmö University in Sweden.

4.1 ‘Native’ artefacts

We begin by considering the use of ‘native’ artefacts, that is existing tools and technologies in the rehabilitation process. The application prototypes designed within PalCom may replace some of the functions of these artefacts, but more likely will need to support people’s continuing engagement with them in the evolving ‘ecology’ of practices and artefacts. The main actors in the rehabilitation process are the patient, family and friends, employers and work colleagues, fellow patients, physiotherapists and occupational therapists, and the physicians assigned to the patient. Apart from environments in the clinic, rehabilitation takes place in many ‘everyday’ locations, including the home and at some point the workplace. (Sokoler, n.d.) During the first weeks after surgery, the patient typically wears a plaster cast. S/he meets physiotherapists and occupational therapists in the rehabilitation ward to start training and, when the cast comes off, the medical staff and the patient assess the physical status of the hand and delineate the chances for recovery.

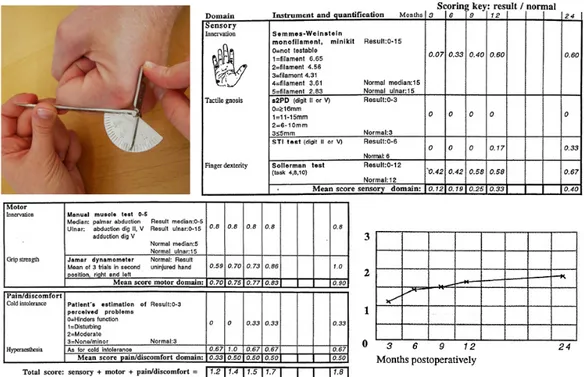

The hand is an extremely complex physical ‘tool’ and recovery of flexibility and even basic functionality can be extremely slow. In severe cases, it can take years of strict adherence to tedious exercise regimes. A number of artefacts are used to assess and monitor the flexibility of fingers, grip strength, tactile sensitivity, and pain. (Figure 2) They also serve to make progress visible, which can otherwise be almost imperceptible to the patient.

Figure 2 - A ‘Native Artefact’. One example out of many: A goniometer– used to measure the degree of flexibility in the joints. The values noted in the status forms allow for the monitoring of progress. The figures shown are results of a 49-year-old man with median nerve repair. (Source: http://www.hand.mas.lu.se/Clinic.html)

Rehabilitation involves medical aids such as splints, exercise regimes with and without exercise tools, and training to cope with everyday life with an injured hand. Some exercises, like the ones described in Figure 3 have to be performed once every hour, 7 days a week, for months, even years. Precise technique is crucial and often complex instructions must be followed carefully. This can make it difficult to stay motivated, especially since progress is often slow and hard to notice.

Figure 3 - Hand rehabilitation exercises as described in paper hand-outs.

However, it is the responsibility of the patient him/herself to get to a good result after the process of rehabilitation – so to a large extend the staff members see themselves not as a medical authority but as a resource supporting the patients in doing this. The PalCom application prototypes build for the domain of surgical rehabilitation also aim to support and develop this practice.

4.2 Fieldcards

Analysis of various types of fieldwork observations at the hand surgery clinic, interviews with staff and patients and a series of user workshops, produced an in-depth understanding of the social, cultural and material practices of using existing artefacts. Most of the insights gained were resumed and translated into ‘Fieldcards’, which then entered into different physical contexts where they were used as part of different modes of activities in the design process.

The ‘Fieldcards’ were created by the two field-working researchers in the Swedish team. They were paper-based and cut out in approximately 7x15 cm with an image on the left and a corresponding story on the right. (Figure 4) All together about 60 cards in different categories were created. The cards were taken back into the real work environment and discussed with staff from the

rehabilitation clinic – a first ‘emplacing’ that produced a range of further insights into the delicacies of everyday practice.

The method of communica-ting field insights through Fieldcards was inspired by previous engaging

experiences of working with so called ‘FieldPacks’ (Agger Eriksen et al, 2003) and participatory design activities of playing design games with field-related cards/video clips (e.g. Iversen et al, 2002, Brandt, 2006). However, our cards were not part of a game with pre-defined game rules but meant as attractive

Figure 4 - 3 examples of Fieldcards.

summaries for communication with colleagues in the design team, who had not been to the rehabilitation unit. - for example by supporting the creation of various

combinations as part of an analysis and the creation of possible scenarios. Below, we describe three examples of use.

To exemplify and discuss the methodological framework provided, the three following examples illustrate how design artefacts such as ‘Fieldcards’ are made part of three different physical contexts and exposed to different modes of activities.

Figure 5 - Fieldstorming.

Participants: local interdisciplinary design team of six interaction design researchers including two field-working researchers.

Fieldstorming.

The Swedish field-working researchers met with the other design members of the local team in their project working area. The aim of the day was twofold: to generate a shared understanding of rehabilitation work, and to generate design ideas sensitive to the practical reality of this work. The field-working researchers put the cards on the table with a brief introduction. They had hoped that the other participants would pick up the cards and start exploring the field insights. However, with the time pressure of the day, it turned out that the two field-working researchers, who produced the cards, used the cards to compose combinations to presented key stories and explain their insights. This use of the cards emerged along the way. In the subsequent idea generation phase of the fieldstorm, The insights captured in the Fieldcards associated with the stories told , worked quite well as inputs informing the following generation of future design scenarios.

Figure 6 - Communicating field insights.

Participants: The local design team and members from Palcom design teams in other countries and institutions

Communicating field insights and ideas.

The ’Fieldcards’ and scenarios became part of a presentation made by the field-working researchers at a workshop for colleagues from other partners in the PalCom project, sitting around the local meeting table. Based on the previous experiences, the use of the cards was strongly facilitated, so they were on the table, but some particularly important ones were also passed around as they

appeared in digital formats in a

PowerPoint presentation. This guided path through the cards suggested a way of interpreting the insights for the design tasks addressed in the workshop, and provided valuable input for the discussion of scenarios and design ideas. However the open character of the cards also allowed for participants’ own

interpretations and cross-fertilization with field insights and design ideas from other domains of use within the project, represented by members from the wider PalCom team.

Figure 7 - Plenary project meeting.

Participants: about 50 project members from across the whole interdisciplinary it-research project team.

Plenary project meeting.

Finally the Fieldcards were brought to a plenary project meeting where people from a variety of professions from the whole research project met. The cards were arranged on a large board supposed to work as inspirational field insights. However, the board was displayed on a pin board at the back of the meeting room (indicated by a green box in Figure 7). It almost drowned in the large space. Furthermore the FieldCards were not integrated into any of the activities on the agenda and did not play a significant role in this context.

A brief analysis of the three examples above highlights a simple, but important lesson. Artefacts like the Fieldcards, which allow many open-ended interpretations and uses, do not work by themselves, and it is not enough to bring them to different contexts. They require animation and facilitation, and work with them needs to be a scheduled and integrated part of the activity, to be seriously utilized to inform and inspire interdisciplinary collaborative design work.

4.3 Mock-ups

Working with mock-ups is a widely used industrial design method, which has been broadly adopted within interaction design and IT-research to help make design proposals concrete and support communication in interdisciplinary design teams also including end users. (e.g. Ehn et al, 1991) Furthermore e.g. Capjon argue for continuously working with different versions of the proposed solution, to refine the concept and detailed design by explicitly comparing use qualities, aesthetic, interaction features, etc. (Capjon, 2005)

Figure 8 - 2 x mock-up design proposals for supporting surgical rehabilitation processes.

At the point in the project when these two different mock-ups were developed, it had been decided to focus on working with video-imagery, and the mock-up examples discussed here, both combining the same functionalities of integrating personal handheld mobile devices, a ‘video-recording-docking-station’ and a ‘sharing-media-bowl’ (‘activated’ when up side down). Furthermore both proposals include a lamp working as a metaphor for an ‘adjustable video-camera’. (see Figure 8). Both are meant to support and develop the everyday practice described in the Background section. The aim is to develop the work of instructing, understanding and following rehabilitation exercise instructions, by allowing therapists and patients to record, play-back and share audio-visual notes during a consultation, at home, at work or in patient group session.

The ‘mock-ups’ were created by the local Swedish team developing the application prototypes for hand surgery rehabilitation within the PalCom project. The mock-up design proposals were based on fieldwork and more general ideas of interaction principles, and they were

supplemented by detailed illustrated, paper-based use scenarios.

To exemplify and discuss the methodological framework provided, the three following examples illustrate how design artefacts such as ‘Mock-ups’ are made part of three different physical contexts and exposed to different modes of activities.

Figure 9 - Video prototyping with mock-ups.

Participants: Three local interaction design researchers with one also being a field-working researcher.

Video prototyping with mock-ups.

For this particular activity the normal local meeting space of the Malmö design team, was configured to be a setting for role-playing scenarios of use with the full scale mock-ups for the purpose of producing video prototypes. Video-prototypes are video-recorded role-plays illustrating and communicating a possible future situation of use in some detail. From an end-user perspective it captures the interaction flow, and the story is often carried by an everyday-like dialogue between the actors. (Mackay, 1988). The role-playing required all participants to be in a mode of acting out and refleting upon detailed interaction with the artefact in play and the situation at hand, revealing different interpretations as well as many unexpected difficulties and opportunities – for example the design proposals supporting or making it cumbersome to share and see alignment of what is imagined to be happening on the displays of the mobile devices.

Figure 10 - Scenario and technology design meeting. Participants: interaction design researchers with one also being a field-working researcher and a group of software developers from the larger it-research project.

Scenario and technology design meeting.

The mock-ups were brought to a different physical context - a meeting-space at one of the projects’ commercial partners’ head quarters. New role-plays were enacted with the same mock-ups to communicate, share and further explore the possible use scenarios and design proposals hands-on with more technical and software oriented project members, who knew only very little of the use site and situations of surgical rehabilitation. This was also supported by illustrated and written paper scenarios. Exploring the mock-ups and scenarios was a bit more cumbersome, as the ‘adjustable camera lamp’ was replaced by a less flexible overhead projector, but the activity still inspired the software architects to identify architecturally interesting challenges and opportunities e.g. ‘short-lived assemblies’ with very diverse and changing resource demands. Another goal and outcome was to decide which use scenarios and application prototype to focus on in the following development process.

Figure 11 - Hospital – user/co-designer workshop. Participants: interaction design researchers with one also being a field-working researcher, software developers, sociologists, etc from the larger it-research project and three rehabilitation staff members (a physiotherapist, an

occupational therapist and the manager of the department).

Hospital – user/co-designer workshop.

Next, the mock-ups were brought to the real world use environment of the hand surgery rehabilitation clinic, where the participants were divided in two groups working in parallel in two different meeting rooms each with one of the two ‘Mock-up’ design proposals. The future use situations were introduced to the staff and new project members by the Malmö design team. This happened partly through verbal explanations and written scenarios, both setting the scene for short role-plays with the mock-ups. In the role-plays staff members played their usual roles and one or more researchers acted as patients, however, it quickly drifted into more general and overall modes of discussion of the current ideas. Towards the end, in plenum experiences and insights from the two groups were compared and listed in keywords on a board, which worked as input for continuous work the following day.

Generally analysis of the experiences described above, show that artefacts like these ‘mock-ups’ help make the interdisciplinary exploration and interpretation of ideas concrete. Setting the scene for role-playing, the two specific uses (video-recording and sharing-media) could be enacted in a variety of contexts as the only really necessary additional artefacts apart from the collection of ‘mock-ups’ were actors (some participants), a surface and chairs. However, going to the different places (contexts) together with different groups of people also meant going into different modes of activities as the expected outcomes based on the role-playing with the ‘mock.ups’ and the disciplinary perspectives and expertise brought to the

engagement with the artefacts differed.

Based on previous successful experiences (e.g. Büscher et al, 2004) one could have imagined that bringing the ‘mock-ups’ to the real world use context like in the last example, could have added something over and above evaluative discussion because the realism of rehabilitation staff enacting real world work with (mock-ups of) future technologies and ‘mock-patients’ could open up an opportunity for the emergence of embodied future socio-technical practices - something crucial for the design but hard to imagine and appreciate discursively. However, in retrospect, partly because we used meeting rooms as the physical context of interpretation rather than the real consultation rooms, this did not really happen. Moreover, with ‘mock-ups’ like these, which were not very detailed and therefore very open for

interpretation, to be understood and used as intended by new participants, setting the scene by the researchers who were part of designing the mock-ups was necessary (in the last two examples). This was done both by verbal introductory stories framing the setting and through detailed written and illustrated scenarios – which especially in the two last examples also worked as central design-artefacts. However, the detailed written and illustrated scenarios were somewhat prescriptive, especially in the last example, where they impeded emergent and more creative use of the ‘mock-ups’ although this was a stated purpose of the activity. While the evaluative discussion was useful, genuine evaluation was not really possible, because the ‘mock-ups’ were too simple, as they e.g. had no real functionality, no indications of feedback on interactions, which left the discussions at quite general levels (also see Brandt, 2005).

4.4 Prototype

Working with technically functioning prototypes (often a mixture of hard- and software) is a widely used approach within interaction design and IT-development and research, as making design proposals concrete supports the process of detailing and the dialogue, exploration and interpretation within interdisciplinary and participatory design teams. (e.g. Büscher et al, 2004). Among others e.g. Kramp also argues for quickly moving from mock-ups to functioning prototypes. (Kramp, 2006).

The ‘Prototype’ discussed here (Figure 12 & 13) is a ‘palpable’, intuitive rehabilitation video-recording service to be used during consultations at a hand surgery rehabilitation clinic, for capturing e.g. instructions for training exercises as they are given by a physiotherapist or occupational therapist and executed by the patient him/herself. The point is that both get a copy, and the patient can play back the instructions in any given context at any given time when needing to recall or demonstrate how to do different rehabilitation exercises.

The ‘docking-station’ is connected to the ‘adjustable light/video-(web)camera’ capturing the video stream, and it can hold, align and ‘colour’ two handheld mobile devices in the dedicated slots – one being the staff’s handheld working tool (e.g. a personal digital assistant) the other being the patients device (e.g. a mobile phone or i-pod), both augmented to work with this service and to become record/stop interfaces.

The prototype was designed by the interdisciplinary design team developing application prototypes for the domain of hand surgery rehabilitation within the PalCom project. It was based on the fieldwork and use scenarios mentioned above, as well as intentions of working with the concept of ‘explicit interaction’, as a principle challenging the software

technology developments in the overall project. Other technical challenges e.g. included. the creation of ‘short-lived assemblies’ and a need for live video-streaming to the two aligned wireless devices.

To exemplify and discuss the methodological framework provided, the two following examples illustrate how design artefacts such as ‘Prototypes’ are made part of two different physical contexts and exposed to two different modes of activities.

Figure 12 - Preparing Demo-presentation.

Participants: hand surgery rehabilitation physiotherapist and interaction design researcher/work package leader

Preparing Demo-presentation.

The prototype was brought to the physical context of the PalCom project laboratory where the annual project review was to take place. Previously posters and a large background banner had been produced and hung up to set the scene for the demo-presentation for the external reviewers. The context was new to the physiotherapist, who also had brought different current everyday working tools (‘native artefacts’) to spice the setting and treat the patient (the interaction design researcher/ work package leader). However, without an explicit predefined mode of the activity apart from preparing the demo-presentation, this setup was also an opportunity for the two participants to explore the current state of the prototype in detail by partly role-playing this future work situation of the physiotherapist and partly discussing also with others how to integrate and interpret the work in corresponddence with the other technological developments in the overall PalCom project e.g. challenging the design of the open software architecture through a mixed-media interface and a resource and contingency perspective.

Figure 13 - Future Application Integration at Hospital. Participants: Interdisciplinary team of interaction design researchers and 6 hand surgery rehabilitation staff members (Three physiotherapists / Three occupational therapists)

Future Application Integration at Hospital.

The prototype was brought to the real world use context of the hand surgery rehabilitation clinic, where it is intended to be used. During this session the design team of researchers moved around with the ‘Prototype’, to meet four different future users (two

physiotherapists and two occupational therapists) in their different everyday work places where they usually consult their patients. The mode of the activity had been decided beforehand – to try out the detailed interaction and to evaluate in qualitative ways what had been made and how it could become part of future work practice. One of the researchers facilitated this activity. These evaluations emphasised a point already noted during the field studies: that the material and social characteristics of the four work places into which the design should fit differ substantially. For example,

physiotherapists work in one or two person offices (left - Figure 13), while occupational therapists work in open spaces with other staff and patients constantly moving around and also needing the top of the table for other purposes than training consultations e.g. for creating splints (right - Figure 13). However, except for including a small extra table in the one-person office, it was managed to ‘craft’ the prototype into the current work contexts, and generally the feedback was positive.

The experience with combinations of artefacts, contexts and modes of activities in these two examples suggests that artefacts like these (partly) functioning prototypes help significantly to communicate ideas and facilitate interdisciplinary evaluation, interpretation and dialogue not least by making change concrete, context-relevant, explorable through embodied

engagement, in other words, ‘experiencable’.

As discussed with the mock-ups, setting the scene can be a valuable activity, not least for the practitioners – the rehabilitation therapists in the hand surgery clinic of Malmö University hospital. To explore their everyday work practice in their own context, made different through the insertion or ‘crafting in’ of a new technology, allowed for embodied ‘practical creativity’, a pre-requisite for the emergence of viable future practices. Of course, working in a

participatory design project and in continuous collaboration with the hospital personnel, not all of their experiences and feedback came as surprises (luckily) as the team of researchers already was quite familiar with the place and current practices. Also, it was no surprise that the personnel who knew and, had in fact, co-created the prototype, provided more detailed feedback than the ones for whom it was new.

However, a valuable example of a new insight did show. It was initially envisaged that staff would ‘stage’ the recording as and when it was imminent during the consultation, and through this explicit interaction move encourage patients to do the same, while also allowing

colleagues to see that now they should not be disturbed. Technically this act would also ‘tell’ the software architecture and the assembly of devices that it should now become a stable and non-shareable entity. However, when acted out under ‘realistic’ conditions, staff placed the mobile devices in the docking station at the beginning of a consultation, and then used the record/stop button when needed.

Experiences like these also allow different disciplinary perspectives and reflections to be brought to socio-technical evaluation and innovation. The real world use context with its socio-material details thus facilitates invaluable practical experience and practical, embodied creativity for the participatory design team.

Furthermore it seems that when design-artefacts like his Prototype are approaching real-world products and services, then an explicit mode of activity is not as important as with more open-for-interpretation artefacts like the Fieldcards and Mock-ups discussed above.

5 Discussion

To make the provided methodological framework concrete, the eight examples presented and discussed above (Figures 5-7, 9-11,12-13) are meant to illustrate practical examples of inter-relations between the exploration and interpretation of artefacts with the role of different contexts and not least with awareness to the mode of the activity taking place.

All the examples show different quite intense activities, where an interdisciplinary design research team met for the duration of 2 hours to a day. These activities have all created different design impulses for the design team, and hence have played different roles in driving the design processes forward. However, like shown, such activities or events are not

successful by default, but our experiences are, that they do work as strong internal deadlines and shared experiences to refer to (e.g. Brandt, 2001) . Furthermore we are, of course, aware that such events are not the only means to inform the design as e.g. detailing work,

interpretations and re-representations (Agger Eriksen, 2006) also has to be done to drive the design process forward in between such interdisciplinary collaborative design-oriented activities. However, there is no doubt that they can work as design impulses in practical interdisciplinary and participatory design research.

Based on the initial reflections after each collection of examples above, in the following all the examples will be further compared and discussed to illustrate the statements made. The purpose of all the statements is to highlight issues to be aware of when referring to the framework of carefully combining artefact – context – mode of activity, for the purpose of supporting fruitful, interdisciplinary, collaborative design work and practice .

5.1 Five statements

> Deliberately changing mode of activity in the same physical context can add new insights.

Even though it happened over a longer period of time, two of the exemplified design activities took place in exactly the same physical context, ‘The PalCom Shelf’, but with different artefacts (Fieldcards and Mock-ups) combined with different modes of activities (fieldstorming for the purpose of generating design ideas and video-prototyping for the purpose of

communicating such ideas). As both types of artefacts could easily (just) be exposed to verbal discussions, deliberately changing the artefacts and mode of activity in the everyday project work context seemed productive, to change perspectives and encourage new interpretations of the design at hand. (e.g. Figures 5 & 9)

> Setting the scene in different contexts w/ different people also call for awareness of the overall mode of the activity to identify new insights.

In the examples with Mock-ups, these artefacts were used in different yet kind of similar meeting-room contexts to help set the scene for interpretation of the artefacts. In those examples the artefacts were also partly included in similar modes of activities – activities of role-playing with the Mock-ups to encourage hands-on exploration and interpretation of the current state of the design. Likewise the Prototype was exposed to some activities of setting the scene for role-playing to explore its intended use. However, the purpose of those staging-activities differed, so it was primarily a part of the identified modes of staging-activities (e.g.

communicating ideas, identifying technical challenges, comparing different design proposals and exploring emerging future practice), which ensured that the insights from the sessions were as expected and thus drove the interdisciplinary collaborative design. (e.g. Figures 9, 10, 11 & 12)

> The real world use context is an important part of the palette of contexts of design interpretation and exploration of future practice.

The socio-material details and characteristics of the real world use context (in this case the hand surgery rehabilitation clinic) can unfold new insights around the artefacts in play (e.g. Mock-up & Prototype), which are difficult to discover elsewhere. However, to make the most of this context the current state of the design should be intervening everyday work practice and not just be worked with in meeting rooms in the environment – which happened in one of the examples described. However, the purpose and modes of the two activities exemplified in the real world use context did differ (comparing two interaction ideas and design proposals & evaluating functionality and emerging future use practice), which of course also affected to use of the context for interpreting the artefacts. (e.g. Figures 11 & 13)

> Design-artefacts generally need to be part of the official mode of activity to get into play.

Some design-artefacts (e.g. open-ended ones like the Fieldcards) drowned in the context in which they were intended to be used, or they were difficult to just initially comprehend, so to get into play, such artefacts need to be part of the agenda and the mode of at least some of the activities during the whole event. This can be initiated either by collaborative agreement of how to do things or by quite strong facilitation by the people who produced the artefacts – in these examples the field-working design researchers.

(e.g. Figures 5, 6 & 7)

> Different types of artefacts call for different levels of attention to context and mode of activity.

It is not enough to just bring artefacts to a specific context, if the people participating in that context are not sure whether to e.g. evaluate the artefacts in detail or imagine other possible future uses. The characteristics of various types of design-artefacts differ. The ones closely simulating real products and services e.g. functioning Prototypes seem quite intuitive to engage with and interpret not least in real world and real world simulated (setting the scene) contexts, whereas other more open-ended artefacts such as the Fieldcards, are less

dependent on the context in which they are being used and interpreted, but more importantly call for a clear mode of activity including a level of facilitation. Artefacts like the Mock-ups can be viewed as being in between – at least at the level of detail of the ones exemplified in this paper. They were still quite open-ended for various interpretations and integration in various modes of activities e.g. setting the scene for various purposes in different context, so these purposes need to be made clear to not just drift into more general and overall discussions and

interpretations which does not necessarily drive the design forward. (e.g. Figures 5-7, 9-11 & 12-13)

5.2 Concluding summary and Future work

To summarize the provided methodological framework has been exemplified through a few design methods including different types of design Artefacts, which have been described quite tentatively in the different examples. Like mentioned in the end of the Background section the framework is also based on overall previous experiences from other related it-research projects, but in the future it could very well be refined by also inserting and critically examining other design methods in detail.

In some of the examples described above one of the two (Context – Mode of activity) can be viewed as more dominant than the other in the interpretation of design Artefacts, but based on a view of all the practical examples, generally it is argued that integration and careful combinations and changes of both Artefact – Context – Mode of activity can help challenge interpretations and is worth aiming for to create design impulses in interdisciplinary

collaborative design (research) practice.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to our colleagues from the PalCom research project and the personnel from the hand surgery rehabilitation clinic at Malmö University Hospital in Sweden.

The research presented in this paper has been funded by the European 6th. Framework Programme, Information Society Technologies, Disappearing Computer II, project 002057 > PalCom: Palpable Computing – A new perspective on Ambient Computing.

References

Aarts, E. & Marzano, S. (2003) The New Everyday View on Ambient Intelligence. Philips Design. 010 Publishers. Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

Agger Eriksen, M. (2006) Material Means…’Re-Representing’- Important Explicit Design

Activity. Exploratory paper in Proceedings of the ninth conference on Participatory Design -

PDC2006, pp. 89-92. Trento, Italy.

Agger Eriksen, M. & Büscher, M. (2003) Grounded Imagination: Challenge, Paradox and

inspiration. DC Success Stories, Proceedings of the Tales of the Disappearing Computer – in

Print, Greece.

Atelier: http://atelier.k3.mah.se/home/

Brandt, E. (2006) Designing Exploratory Design Games: A Framework for Participation in

Participatory Design?. Proceedings of the ninth conference on Participatory Design -

PDC2006, pp. 57-66, Trento, Italy.

Brandt, E. (2005) How tangible mock-ups support design collaboration. Nordes 2005, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Brandt, E. (2001) Event-Driven Product Development: Collaboration and Learning. Ph.d. Dissertation. Dept. Of Manufacturing Engineering and Management, DTU, Denmark.

Büscher, M., Agger E., M., Kristensen, J. F., Mogensen, P. (2004) Ways of grounding

imagination… Proceedings of the eighth conference on Participatory Design – PDC2004, pp.

193-203, Toronto, Canada.

Büscher, M., Christensen, M., Hansen, K.M., Mogensen, P., Shapiro, D. (forthcoming - Accepted for publication.). Bottom-up, top-down? Connecting software architecture design

with use. In: Hartswood et al. Configuring user-designer relations: Interdisciplinary

Bødker, K., Kensing, F. & Simonsen, J. (2004) Participatory IT Design. Designing for

Business and Workplace Realities. MIT Press.

Capjon, J. (2005) Engaged Collaborative Ideation supported through Material Catalysation. Nordes 2005, Denmark.

Dourish, P. (2001) Where the action is - The Foundations of Embodied Interaction. The MIT Press, London.

Ehn, P. et al. (forthcoming) Opening the digital box for design work – supporting performative

interactions, using inspirational materials and configuring of place In: Selected papers from

projects of the Disappearing Computer Initiative (working title)

Ehn, P. & Kyng, M. (1991) Cardboard Computers: Mocking-it-up or Hands-on the future. Design at Work s. 169-196., Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Ehn, P. (1988) Work-oriented design of computer artifacts. Falköping: Arbetslivscentrum/ Almqvist & Wiksell International, Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Gaver, B., Dunne, T. & Pacenti, E. (1999) Cultural Probes. Interactions, p. 21-29.

Haraway, D. (1999) Situated Knowledge: the science question in feminism and the privilege

of partial perspective. In: ‘Simians, Cyborgs, and Women’. By D. Haraway. New York,

Routledge, pp 183-201.

Iversen, O. & Buur, J. (2002) Design is a Game: Developing Design Competence in a Game

Setting. Proceedings of the seventh conference on Participatory Design – PDC2002. Malmö,

Sweden.

Kramp, G. (2006) Bridging communication gaps with High Fidelity prototypes. D2B conference, Shanghai, China.

Kyng, M., Greenbaum, J. (ed.) (1991) Design at Work, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc., Mahwah, NJ.

Mackay, W.E. (1988) Video Prototyping: A Technique for developing hypermedia systems. In Conference Companion of ACM CHI 88 Human Factors in Computing Systems, Washington DC. ACM/SIGCHI.

PalCom: A new perspective on ambient computing. http://www.ist-palcom.org/

Sanders, E. & Dandavate, U. (1999) Designing for Experiencing: New Tools. Proceedings of the first international Conference on Design & Emotion, Holland.

Sokoler, T., Löwgren, J., Eriksen, M.A., Linde, P., Olofsson, S. (n.d.) Explicit interaction for

surgical rehabilitation. Manuscript, submitted for publication.

Star, S. (1989) The structure of ill-structured solutions: boundary objects and heterogeneous

distributed problem solving. Distributed Artificial Intelligence (Vol. 2), p. 37 – 54, Morgan

Kaufmann Publishers Inc., USA.