Exploring voice interactions in an

open world video game

environment

Robin Harnesk

Harnesk@gmail.com Interaktionsdesign Bachelor 22.5HP Spring 2019Acknowledgements

I want to thank my supervisor Henrik Svarrer for all his support throughout this degree project.

A tremendous thank you to all people attending interviews, observations and user testing.

Finally, I would like to thank my fiancée for putting up with me during the period of writing this essay.

Abstract

The use of voice interactions in home voice assistants are becoming mainstream and it’s being used to everything from information seeking to personal management. Even though games utilising voice has been praised for its innovation it has never been anything other than a novelty and research has been scarce. This study explores how a voice user interface (VUI) can be designed to reduce in-game interruptions in an open world video game environment. Through literature research, interviews, observations and prototypes aimed towards people playing video games and users of VUIs, this thesis proposes a set of design qualities for future implementation. The findings show that designing for voice interactions in an open world video game is, among other things, a matter of providing context-based triggers together with a compressed and modular approach that does not require the user to shift their attention from the video game.

Keywords: Voice User Interface, Open World Video Game, Peripheral Interaction, Home Voice Assistant, Interaction Design

1 Introduction ... 6

1.1 Purpose ... 6

1.2 Delimitations ... 7

1.3 Target group ... 7

2 Background ... 7

2.1 What are voice user interfaces? ... 7

2.2 Open world games ... 7

2.3 Voice interactions in video games ... 8

2.4 Theory and related work ... 9

3 Methods ... 11 3.1 Design process ... 11 3.2 Literature studies ... 13 3.3 Ethical considerations ... 13 3.4 Semi-structured interviews ... 14 3.5 Observations ... 14

3.6 Brainstorming and Bodystorming ... 15

3.7 Prototyping ... 15 4 Design Process ... 16 4.1 Semi-structured interviews ... 16 4.2 Observations ... 19 4.3 Design opportunity ... 22 4.4 Brainstorming ... 22 4.5 Bodystorming ... 24

4.6 “Wizard of Oz” - Prototyping ... 25

5 Discussion ... 32

5.1 Self-evaluation ... 34

6 Conclusion ... 34

Figure list

Figure 1: Implementation of voice interactions in Google Stadia ... 11

Figure 2: Illustration of Double Diamond Model ... 12

Figure 3: Double diamond with integrated design process ... 16

Figure 4: Affinity diagram clustering insights from interviews ... 18

Figure 5: Participant playing Red Dead Redemption 2 ... 20

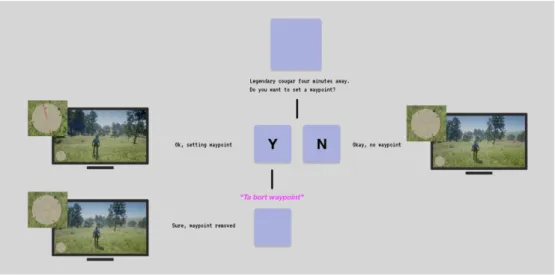

Figure 6: The journey of interactions to set a waypoint in-game. ... 21

Figure 7: Part of the ideas generated during brainstorming session ... 23

Figure 8: Illustration showing order of interactions and its end goal ... 25

Figure 9: Back-end view of one of three commands of the prototype. ... 27

Figure 10: Synergy between user (1) and researcher (2) ... 27

Figure 11: Icon appearing in the bottom left indicating that voice interactions are available ... 28

Figure 12: Illustration showing video output for the player and researcher controlling video output by interacting with video software. ... 29

Figure 13: Annotation sketch of the in-game player view ... 30

Figure 14: Flow of interaction for setting a waypoint ... 31

1 Introduction

Home voice assistants are becoming more mainstream and the last ten years have seen a substantial rise of this technology in everyday life (Myers, Furqan, Nebolsky, Caro and Zhu, 2018). It is being used to everything from information seeking to personal management and Helft (2016) reports that a total of 20% of all Google searches are done using voice interactions and Canalys (2018) reports that global smart speaker shipments increased with 187% in the second quarter of 2018. Despite this data showing an increase in use of voice interactions, the amount of empirical research within the field of human-computer interaction (HCI) has been scarce in terms of usage in everyday situations.

4 in 10 have gaming as an interest and 86% of internet users play games on a gaming console at least once a month (GlobalWebIndex, 2019). Video games implementing speech recognition have been praised for its innovation but never moved past the novelty aspect, and the advances in voice recognition technology in consumer products like Microsoft Kinect have seen a rise during the last ten years (Globalme, 2018). This has led to player-to-player voice interactions receiving notable attention in the field of HCI but voice interactions in games where the voice is used an input, has not. (Carter, Allison, Downs & Gibbs, 2015).

Open world video games is characterised by its non-linear gameplay and freedom to explore. This makes the genre among the most popular genres in gaming (Invision Game Community, 2019). It also has its fair share of menus the user has to navigate through next to their main gaming activity. It is essential that these menus are efficient and provide no interruptions for the user during gameplay (Kulshreshth & LaViola, 2014).

1.1 Purpose

The aim of this study is to explore how voice interactions can be used to reduce in-game interruptions in an open world video game environment and understand how voice interactions in video games are perceived as an input by the intended target group. Through practice of design methods grounded in interaction design, seek to get an understanding of the experience when using a voice user interface and playing open world video games. The study aims to contribute to designers within the field of HCI that seek to gain a better understanding of how to design for voice interactions in a video game environment.

1.1.1 Research question

How can voice user interfaces be designed to reduce in-game interruptions in an open world video game?

1.2 Delimitations

This thesis work will not go into extensive research regarding the technical aspects of speech recognition but rather focus on the value of upcoming and future design of voice user interfaces for voice interactions in video games. It will set out to look deeper into the player experiences that go beyond examining speech recognition technology. This study will be targeting open world video games as it blends qualities of multiple genres into one. There is no intention of having the design solutions being implemented but they will work as a foundation and discussion for future design with focus on the user experience. The research for this thesis is limited to potential users located in Sweden, due the need of having field research and testing done in person. Additionally, one might need to take into account that Sweden is a country of early adopters and users in this study might have a different relationship to new technology compared to other countries. This allows for research with people who already have an idea of what the technology can do.

1.3 Target group

The target group for this study includes people who play video games and want to add another layer of interactivity to their games. Even though users of home voice assistants is included in the research they are not part of final target group. This study is aimed to work with new and experienced gamers but the research in this study has mostly been focused on experienced players due to their knowledge within the field.

2 Background

2.1 What are voice user interfaces?

Voice user interfaces allow people to control computers and other devices through speech recognition (Interaction Design Foundation, 2017). The feedback can be anything from setting a timer or adding a calendar event, to playing a favourite song on Spotify or show a movie on Netflix. The technology offers hands-free interactions with devices such as Google Home and Amazon Alexa. These products are not per definition VUIs by themselves but rather products that incorporate speech technology that makes VUIs possible. Voice user interfaces do not need to have a visual interface and can rely solely on auditory or haptic output.

2.2 Open world games

In an open world game, players are presented with the opportunity to explore and pursue gameplay objectives autonomously within an expansive virtual

world. This open-ended design can help permit non-linear play and give an illusion of a living breathing world. In an open world game, players are free to explore with their own goals as motivation and are not prescribed to a linear set of challenges orchestrated by the game designer. Players are free to experiment with the mechanics and consequences of the game’s open-ended level design (Squire, 2008).

2.2.1 Red Dead Redemption 2

Red Dead Redemption 2 is a western open-world video game developed and published by Rockstar Games and will be the game representing the genre throughout this thesis. It is a prequel to the 2010 game Red Dead Redemption and set in the same game world (Vulture, 2018). Red Dead Redemption 2 broke several records when released and had the second biggest launch in the history of entertainment, generating 725 million US dollars in its opening weekend (Quartz, 2018).

The game is set in 1899 in a fictional version of western United States with the story centered around Arthur Morgan, an outlaw trying to survive against rival gangs, government forces and other enemies. The open-world aspect of the game allows the player to freely roam the game’s interactive open world and take on missions in any order they want (Vulture, 2018).

2.2.2 In-game interruptions

For the purpose of this thesis, In-game interruptions are defined by actions taken when not in direct control of the main character of the game. This is when the player stops controlling the character to interact with the graphical user interface (GUI) of the game.

2.3 Voice interactions in video games

One of the earliest examples of using voice interactions in video games were on PCs, with the game Command: Aces of the Deep released in 1995 being one of the first (Carter, et al., 2015). This was a submarine simulator that enabled the player to control certain parts of the submarine’s movement using voice interactions. Another example of a game using voice interaction was Bot Colony.

This game was built around voice interactions and Bot Colony were one of the first experimenting with a fully voice-driven gaming experience (Globalme, 2018). Bot Colony is a game where the player explores a sci-fi world where robots have become helpers in human society. The idea was that players would command robots using voice interactions but the technology failed in understanding the commands and gameplay showed to be more fruitful when using the keyboard to type the commands.

Seaman is another example of an early attempt to create an experience with

voice commands. A game where the player took care of a virtual pet with the goal of guiding its evolution from water to land.

Since then, voice interactions in video games has been heavily shaped by the evolution of console hardware development (Carter, et al., 2015). Nintendo released a unit for its Nintendo 64 console that supported voice interactions. Only two games were released and one of those being Hey You, Pikachu! that allowed for simple voice commands to control the main character in the game. The upcoming console generation in the early 2000s introduced online components which allowed for player-to-player interactions. Several games in the tactical combat genre allowed for communication between players but

Rainbow Six was one of the first that let players give order to AI teammates

using voice commands.

2.4 Theory and related work

This following theory section contains research in areas relevant to the design of voice user interfaces in a video game environment. With the help of research looking at how to design for voice interactions together with theories discussing voice in game design, it will provide information that will help towards a more fruitful exploration in how voice interactions can designed to reduce in-game interruptions.

2.4.1 Designing voice user interfaces

Pearl (2016) presents four areas where voice user interfaces have some advantages; Speed, Hands-free, Intuitiveness and Empathy.

Using voice interactions are faster for text messages even though one might be an expert in using traditional input such as typing or touch input. It also provides a hands-free experience that lets users engage in other activities whilst interacting with the device. Voice interactions also allow people that are less familiar with technology to interact with it without actively having to think about its presence. Voice has the potential to hold information that gets lost in text messages. It can include, tone, volume, intonation and rate of speech which makes it easier for the user to understand the tone of voice in a message.

Pearl (2016) also presents cases where VUIs are not always the best solution; Public spaces, Discomfort speaking computers, Personal preferences and Privacy.

A lot of people work in open-plan office spaces and using voice in such environments might be troublesome. Imagine a space where all computers can be controlled using voice, the number of voice commands would make the office a loud environment to work in. There will also be users that always prefer texting as their main method of communication and they might not want to shift to voice. Privacy is also a main concern when talking about voice

interactions. It’s not only what the user says to the system but also the potential privacy violations the system could put the user in e.g. reading a text message out loud when having a group of people over for dinner.

2.4.2 Peripheral Interaction

With computers becoming more and more ubiquitous there’s a lot of different technologies that are fighting for the users’ attention. Peripheral interactions makes it possible to have the technology work in the periphery of the attention but can shift to the centre of attention when the user wants to. By pushing the attention to the periphery of one’s vision, few mental resources are needed and an example of a peripheral interaction could be turning on the lights whilst watching a TV show (Bakker, 2016)

Peripheral interactions address a dual task scenario, primary and secondary tasks. The Primary task being the scenario that captures the main attentional focus and the secondary task only demands minimal attention (Hausen, Loehmann & Lehmann, 2014).

Not all interactions are suitable for peripheral interactions, some work best in the centre of attention. Tasks that demand great precision are not suitable to work in the background of one’s attention. Writing a thesis for example, will always need be in the centre of attention.

2.4.3 The role of voice interactions in video games

Carter, et al. (2015) discusses the implementation of voice interactions in four major game titles and they argue that a successful integration of voice in video games has to do with the virtually embodied experience. When voice interactions is not related to that experience, it causes a conflict between the user and the character, thus having voice interaction affecting how the game is being perceived. They argue that video games needs to take player identity into account when designing for a successful voice user interface.

Google however, choose to take another approach when presenting their new platform Google Stadia. Stadia is a gaming platform capable of streaming games up to 4k via the internet, with added support for the Google voice assistant (Google LLC. 2019). They take the approach of using voice as a way to overcome obstacles in video games by letting the assistant show them how to complete a certain level of a game (see Figure [1]). They achieve this by having a button on the game controller which is dedicated to the use of their digital assistant. The player can press the button and ask how to beat the level their playing and the assistant will pause the current gameplay session and show a video layer on top of the game.

Figure 1: Implementation of voice interactions in Google Stadia (Google LLC. 2019)

3 Methods

The methods used in this project are from the field of interaction design and are aimed to gain an understanding of the experience using VUIs when playing an open-world video game. Having two different domains to work with when conducting this project, it was important to distinguish relevant from irrelevant methods. The design work in this thesis will be having a Human-Centered Design (HCD) approach and the methods will be chosen to accommodate the field of interaction design.

3.1 Design process

Human-centered design is the process of designing with people’s needs in mind, making the product usable and that it accomplishes the desired user task, leaving the user with a positive experience (Norman, 2013). This approach will play a major part in the work done in this thesis but will work more as a way of thinking rather than an actual design methodology. Always make sure to focus on the people and remind myself that “I’m not the user” to gain insights based on the users perceptions and not my own desires and needs.

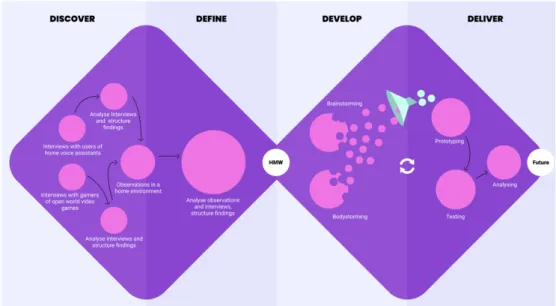

3.1.1 Double Diamond

In this thesis, the design process was conducted with the Double Diamond

Model as the main source. This model was introduced by the British Design

Council (2005) and works as the foundation of this project. The double diamond model is divided into four phases: “Discover”, “Define”, “Develop” and “Deliver” with the phases either diverging or converging (see Figure [2]). A diverging phase is about opening up to as many ideas as possible without limiting the quantity of these ideas. In contrast, the converging phase

is about trying to refine the ideas generated in the diverging phase and narrowing down to the core ones. In the double diamond this happens twice: Once to confirm the design opportunity and once to find a solution to that opportunity (Design Council, 2015).

Figure 2: Illustration of Double Diamond Model (Design Council, 2015)

3.1.1.1 Discover

The first quarter of the double diamond is constructed to help the designer understand the context and needs of its users. In this step, divergent

thinking is practised which allows designers to notice new things and gather

insights previously unknown to the researcher. This is where it’s crucial to empathise with the user and understand all fundamental problems to find the “right” problem later on. In a human-centered design approach it is crucial to put emphasis on understanding the user to make sure people’s needs are met (Norman, 2013). This phase of the design work relied heavily on the involvement of people using VUIs and people playing open-world video games with a focus on understanding their frustrations, desires and needs to identify relevant themes before heading into the define phase.

3.1.1.2 Define

The second quarter of the process is the definition stage and this is where to make sense of the findings. This is when to start synthesising the data gathered in the previous discover phase, thus entering the first converging stage of the double diamond. By doing this, one or several “How-might-we”

questions (HMW) will be generated and work as the foundation when

heading into the develop phase.

3.1.1.3 Develop

The third quarter of the double diamond is the develop phase which is the second diverging phase of the model. This marks the halfway point of the

process and here the designer explores potential design solutions to the generated HMW-question(s). During this phase, the designer should keep an open mind and avoid limitations – there are no bad ideas. The first half of the phase should be focused on the quantity of ideas rather than quality. At the end of the developing phase, the designer evaluates the ideas and a selection of the most interesting ones need to be made before heading into the deliver phase.

3.1.1.4 Deliver

The fourth stage of the process and the second convergent phase of the Double Diamond model is the deliver phase. In this last step, the designer focus on what to deliver to the end user and this is where the prototype is built, tested and iterated. The final prototype will be tested and developed in conjunction with the intended user group to make sure previously mentioned HCD-approach is followed.

3.2 Literature studies

Before involving the users of voice user interfaces and people who play open world video games, a deeper understanding of voice user interfaces and open world video games were necessary. The goal of these studies was to get a deeper insight into the history of voice user interfaces and how voice has been used in the field of HCI before the rising popularity of home assistants. In terms of open world video games, the goal was to understand what defines an open world video game and how voice has been used in video games previously. Studies relating to the experience of using VUIs and playing video games were also included and included as a foundation for the field studies. ACM Digital Library, Google Scholar and Libsearch has been used to gather academic material correlating to the research question. Course literature has been used as a foundation for writing this essay and understand academic texts.

3.3 Ethical considerations

Doing research and testing in a home environment was going to be privacy-infringing no matter the purpose, and this made it important that the consent form sent to the participants was well worked through. One part of collecting data through voice that might be seen as uncomfortable is the fact that Google can keep data to personalise voice search results. We are used to having our digital cookies stored but having our voice available to service providers is not yet as common. This should not be a problem in this thesis since no voice data will be stored. I also needed to make sure that my research methods were executed with the intention of exploration to find non-biased insights and not lead the subjects to my desired conclusions.

The involved stakeholder in this study were informed about the project before participating and they were aware that the gathered information was used in research purposes only.

3.4 Semi-structured interviews

To complement the quantitative data gathered from the literature research, semi-structured interviews were made to understand what motivates users in a specific context. Semi-structured interviews are used to gather information about a set of central topics and also allowing for exploration when new topics emerge (Wilson, 2013).

This was the first contact with users of home voice assistants and gamers playing open world video games. The interviews were split into two user groups to get an understanding of the experience of each domain. When approaching the users of home voice assistants, the goal was to figure out what it felt like using the voice to interact with a machine and the pros and cons of that experience. When interviewing users playing open world video games, the focus was on what makes for a good experience and what elements inside the game that they feel breaks that experience.

3.5 Observations

Getting to fully understand the users, just asking them what they want can give misleading information since people often idealise their needs and desires. To fully understand people’s experiences, we have to see them for ourselves. (Goodman, Kuniavsky, & Moed, 2012). Using observations will allow to produce insights about the way people act when using voice interactions and playing open world video games. The observations were conducted in the home of the participants and their goal was simply to play the game as they would without anyone present. In the end of the observation, the participants were asked to use their voice to interact with the game. This was a way to pinpoint what segments of the game they felt voice would be most appropriate. To get as good of an understanding as possible,

contextual inquiry followed the observation together with questions based on

their behaviour.

3.5.1 Contextual Inquiry

Presented by Saffer (2010) as a form of shadowing where the designer asks questions about the participant’s behaviour in a certain situation. This method was used during a longer observation of people playing Red Dead Redemption 2 and interacting with its world.

The participants did not know the observations would be followed up by this active observation technique. The reasoning behind not telling the participants was to get genuine answers based on their feelings during that

specific moment and not to get a well formulated answer potentially constructed to please the aim of the study.

3.6 Brainstorming and Bodystorming

Brainstorming is the art of creating concepts and the idea of this method is to generate many concepts as possible, not to find the perfect design. Ideas that might seem out-of-place is much welcomed here (Saffer, 2010). Bodystorming is an ideation method where the designer physically guides the user through situations they want to innovate within (Interaction Design Foundation, 2019). The idea of using bodystorming as one of the selected ideation techniques was to get an actual hands with the users and see what problems they encounter when interaction with the game through voice and not only theorising about the scenario. Bodystorming may include using different props and setting up an entire space dedicated to the bodystorming session. The idea behind the bodystorming session was that the participants were supposed to elaborate on each other’s ideas. Much like the method of

Brainwriting, where each participant write down ideas for other participants

to elaborate upon (Interaction Design Foundation, 2019).

3.7 Prototyping

Houde and Hill (1997) describes prototypes as a way for the designer to examine design problems and evaluating its solutions and Saffer (2010) define prototypes as a way to express the interaction designer’s vison of the design. The model introduced by Houde and Hill (1997) represents a three dimensional space which corresponds to the most important aspects of a design. This model will be used to evaluate the purpose of the design and from that, create a discussion about the prototype that leads into new insights that helps form the next iteration.

With focus on exploring how voice interactions can be used in open world video games, the prototyping methods used was intended to explore the role and “look and feel” of the prototype rather than the “implementation” of it. Houde and Hill (1997) defines “Role” as being the questions about what function the product will serve in the user’s life. The “Look and feel”-dimension is more focused on the sensory experiences and “Implementation” refers to how the artefact will actually work.

By using low fidelity prototypes, it allowed for a quick way to explore multiple design ideas and gather information from the reactions of the participants.

3.7.1 Wizard of oz

Using the method of Wizard of oz allows for interactivity with a prototype that are not, or only somewhat interactive (Saffer, 2010). This method allows the user to interact with the design as if they were interacting with a functional prototype but when in reality its controlled by another person. The

designer could make the prototype seem interactive e.g. by changing the visuals when the user initiates a certain interaction. This technique provides possibilities that might have been hard to implement, expensive or not technically attainable. It also allows me to evaluate the feasibility and value of a prototype in its early stage without having to spend a lot of time on developing a functional hi-fi prototype. This method was used during both the initial testing phase and the final usability stage of the project but with two different intentions. Using Wizard of oz in the first stages of the testing as a mean to let the users quickly understand the concept and express ideas used for further iteration. The focus of using Wizard of oz in the latter parts of the project was evaluate to conceptual value of the design rather than focusing on how voice interactions implemented.

4 Design Process

To reach a final concept in the end of this design process, seven participants were chosen to be a part of the process. They were split in two groups, four participants being users of home voice assistants and the three participants were gamers with experience playing open world video games. To get a better understanding of the design process, an overview is presented as an integrated part of the previous mentioned double diamond model (see Figure [3]).

Figure 3: Double diamond model with integrated design process

4.1 Semi-structured interviews

The aim of this project was to explore how the use of voice interactions in open world video games can be designed to reduce in-game interruptions. In

order to achieve this, the discovery phase started with semi-structured interviews to learn more about the user groups of each domain.

4.1.1 Purpose

The interviews were conducted in the home of each participant and the purpose of having the interviews conducted in a home environment was to make the participants feel as comfortable as possible. Since home voice assistants and console gaming occur in the users’ own homes, it was a conscious decision to conduct the interviews in their natural environment. Placing the participant in the context of what’s being researched might help them generate ideas about what they like and dislike about the product. In order understand how to design for voice interactions in open world video games, it was crucial to get an understanding of its users since it would not be satisfactory to only identify the issues of VUI’s and have that in mind when designing a VUI for the game. It was also needed to gain knowledge about the attitude towards using voice when interacting with an open world video game. What kind of usage does voice interactions afford for gamers and how does that differentiate itself from how user of voice assistant express their feelings toward voice interactions? It was important to identify what kind of interruption tends to break the experience of playing the game in order to explore if voice can be implemented to reduce those interruptions. The interviews were used as a way to identify what gamers believe takes them out of the experience and affect the gameplay negatively.

4.1.2 Execution

The interviews were conducted with open-ended questions and the main focus was on making the interviewees answer the questions based on their own experiences. The questions were formulated so that the participants answered them from their own perspective, and not if it could be of value for someone else.

“When we try to put ourselves into others’ shoes, we idealize and simplify.”

(Kuniavsky et al, 2010, p. 132)

The interviewees were introduced to the project without going into much detail about it and information was intentionally left out during the briefing of the project to stay as neutral as possible. The information shared by the interviewees should be as untainted as possible and by going into too much detail about the project might cause them to answer some question according to what they think the designer wants to hear. This is described by Kuniavsky et al. (2012) as a common problem when conducting interviews and the information shared was therefore limited to its essentials.

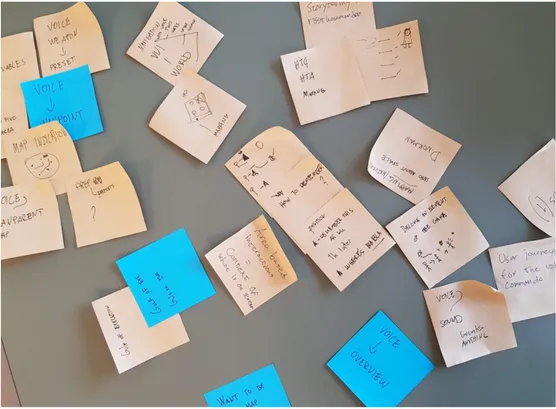

Another important aspect during the interviews was to get the participants as comfortable as possible in the situation with the goal of creating an atmosphere where they felt like they could share anything during the interviews. The data gathered during the interviews were later collected and sorted into clusters by the use of an affinity diagram (see Figure [4]).

Figure 4: Affinity diagram clustering insights from interviews

4.1.3 Findings

When interviewing users of home voice assistants, they expressed true emotions and had no problem in communicating their feelings about the device, negative or positive.

They all used Google Home as their voice assistant and the general thoughts about the system was that it works well but that it held great potential. This might have explain their excitement during the interviews and even though they might not have reflected upon it, the participants showed passion for their systems.

The main issue when using voice as a way to interact with the devices was that they felt like the speech recognition technology felt lacking. The majority of the interviewees expressed that the system quite often did not understand what they were saying to it and that they had to repeat themselves in order for the device to initiate an action. Similar comments were made when talking to gamers and the use of voice in video games. One participant expressed that:

“I play Red Dead Redemption to experience a good story and to be part of its world and if voice interactions would be a possibility and the game would have me repeat what

I’ve just said, I would never do it again”

The concern of failing technology in both user groups was expressed both implicitly and explicitly. Users of Google Home expressed that they prefer to use shorter commands when interacting with the device. I see this as something that could point to their disbelief in how well the device can

understand them and might be a way to make sure they leave as little room as possible for interpretation to maximise success rate.

But it could also be an effect of the actions you want the device to perform. If the goal is to make the device perform a concrete task for the user such as “setting a timer” or “adding a calendar-event”, there might be no motivation to use a longer voice interaction.

The most common ways to use voice interactions was to give commands that asks for a specific task to be performed. The majority of commands used showed a trend of using voice interactions as a “productivity” tool rather than asking it for information or having small talk. Productivity relates to activities that are tied to managing tasks such as; calendar, adding items on a shopping list or setting a timer.

When talking to gamers with experience in playing open world video games, they expressed that they felt separated from the game when using the in-game map. The map is something that is used as a main mechanic of the game as a tool for navigating the world. When talking more about the experience of using the map in Red Dead Redemption 2 it was evident that the map itself provided features that was appreciated but the way it was used broke the flow of the gameplay.

4.2 Observations

Interviews made it possible for the participants to express their opinions about voice interactions and open world video games but to truly understand the context of using voice in open world video games, observations were made. As mentioned earlier in the essay, Kuniavsky et al. (2012) describes how people often assume that the know what they want and communicates that during the interviews. By having observations it allows me to focus on what the users actually are doing, as opposed to what they say they do.

4.2.1 Purpose

The purpose of using observations was to gain insights about contextual information in a certain context. Observations was used to get information about the environment of the participants and how they acted in it. This method was used to identify what was valuable for the participants without having them explicitly communicate it. As previously mentioned when talking about the interviews, having the participants feeling comfortable in the situation was one of the key factors when conducting the observations to get natural reactions from them.

4.2.2 Execution

The observations followed a certain routine to fully understand the user in their context and how the use of voice impacted the gameplay of the

participant. The observations were split into 4 phases to see how they acted in different scenarios.

Figure 5: Participant playing Red Dead Redemption 2

The first phase of the observations started with having the user playing Red Dead Redemption 2 with me sitting next to them and observing their actions (see Figure [5]). The focus was on identifying the main activities in the game context and study how they interacted with the game. The observations mainly consisted of this phase.

The second phase of the observations involved me initiating a conversation with the participant and asking questions regarding their activities, also described earlier as contextual inquiry (Saffer, 2010). This was made in to see how they reacted to voice when playing a video game. Both from the perspective of having the participant receiving auditory information whilst playing. But also as a way to see how well voice works as a peripheral interaction when having the participant communicate back.

During the third phase of the observations the focus was entirely on voice interactions with the game. They were given a task of trying to communicate with the game using voice however they wanted.

The fourth and final phase consisted of a follow-up interview based on previous phase. Questions were asked about how they felt about using voice whilst in the game and the reasoning for choosing to use voice during certain aspects of the game. The attention was mainly put on what they did in the game and how they felt about using voice when playing the game.

4.2.3 Findings

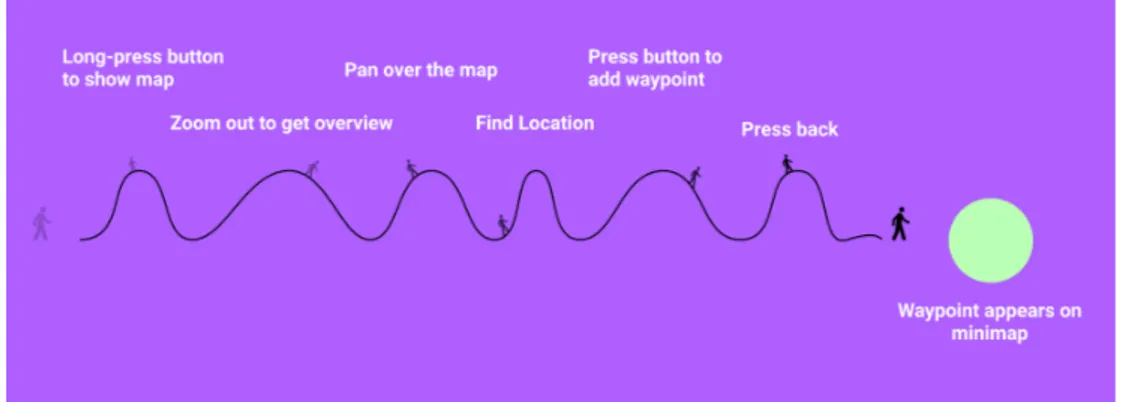

The first thing noticed when observing participants playing Red Dead Redemption 2 was the consistent use of the in-game map. The in-game map was expressed in the interviews as something being in the way of experiencing the game but also something they felt was useful when looking for something to do. The features the map consists was valuable enough for them to use it constantly when playing the game. It acted as a main tool for setting waypoints to destinations containing game missions. This left them out of the main game activity for a substantial amount of time doing productivity related tasks . They knew what they wanted to do before heading into the map but still, they had to use multiple interactions to place a waypoint to a selected area (see Figure [6]).

Figure 6: The journey of interactions to set a waypoint in-game.

When asking about where they were heading, the answer was in line with “to the next mission”, “going back to base”, “to (main character)”. This indicates that not much time was given reading about the mission but the goal seemed to be about finding a mission and setting a waypoint.

During the observations, participants had no problem talking to me whilst doing complex in-game actions. Similarly, they had no problem talking about their actions and feelings whilst playing the game. These conversations were not a part of the second phase of the observations but initiated by the participants themselves, even though I communicated that the idea of the first phase was for me to observe them whilst playing. This leads me to believe that voice interactions cannot be forced into the game, it has to be a naturally generated.

When letting the participants communicate with the game using voice interactions the majority of interactions were focusing on replacing the different menus in the game. Much like the insights when conducting interviews with users of home voice assistants, the players used voice as a productivity tool rather than trying to use their voice to communicate with in-game characters. Furthermore, the participants started by communicating with longer sentences but these became shorter for each iteration of the interactions.

4.3 Design opportunity

After the research phase presented in previous chapter a number of areas were found to be valuable for the participants when playing Red Dead Redemption 2. There was one area that proved the be more important than the other areas and that stood out as the main interruption when playing open world video games was the navigation through different in-game menus and more specifically setting waypoints. It was something the players did multiple times during the observations and also something that they expressed during the interviews as taking them out of the gaming experience. In order to use voice interactions to reduce time spent in elements of the game that takes the user out of the main activity, we need to know when and

how it can be used. I realised during the observation sessions that it’s not just

about making voice interactions is available for the user. It needs to be communicated properly when and how it can be used without itself adding another element that takes the user out of the experience.

4.3.1 How Might We

Based on previous design opportunities two HMW-questions were composed;

How might we make transitioning between the main activity and interacting with the map a coherent experience?

How might we communicate the possibilities of a VUI in a video game environment?

4.4 Brainstorming

With previous insights from the interviews and observations, a brainstorming session was conducted. The purpose of the brainstorming was to generate as many concepts as possible based on previous insights. It was important not to become obsessed with one or two ideas but to allow for multiple ideas surrounding the two HMW-questions.

4.4.1 Execution

This session was conducted together with one participant from the home voice assistant-interviews and one from the gaming observation. During the session, the participants wrote one post-it note per idea in order not to spend too much time on perfecting one idea but to move forward and generate new ones (See Figure [7]). All ideas were welcomed and the HMW-questions was the starting point of the brainstorming sessions. If they generated an idea that was not directly tied to the HMW-question, it was still allowed and considered when heading into prototyping. Even the ideas that felt out of place or irrelevant was included in the brainstorming session due to its capability to spawn new ideas.

“Even crazy ideas, often obviously wrong, can contain creative insights that can be later extracted and put to

good use in the final idea selection.” (Norman, 2013, p. 266)

During the brainstorming session I questioned everything the participants created. This was inspired by Norman (2013) and his fondness of “stupid” questions. He explains that what we see as obvious is merely a product of something we have always done a certain way, and it’s not until it’s questioned we realise why we do it. One example could for be to question why they want to use words when communicating with the game. This could then lead to them explain thoroughly why words is of significance when communicating with a device, starting a conversation about other possible means of communication with the game.

Figure 7: Part of the ideas generated during brainstorming session

4.4.2 Findings

By questioning everything during the brainstorming session it allowed me to get a deeper understanding of how voice is relevant in a gaming environment. It allowed me to generate ideas that was not directly related to voice communication with words, but rather how we could use sounds as a way to communicate with the game. Not only did the brainstorming session provide ideas of how interaction through voice could be applied to reduce in-game interruptions but also how we can use in-game context to signify the usage of

voice interactions inside the game. Signifiers, as described by Norman (2013) determines where an action should take place to make the user understand the product they wish to use. He presents signifiers as clues that indicates the interactions possible in a digital system. Applying this to my project will be more concentrated on making the availability of using voice interactions apparent for the user.

4.5 Bodystorming

The purpose of having bodystorming as one of the ideation methods was to see how the participants would act when physically enacting a made-up voice interaction scenario when playing an open world video game. Not only this, but another purpose was to examine if there’s any value in seeing the participants trying to iterate on each other’s voice commands.

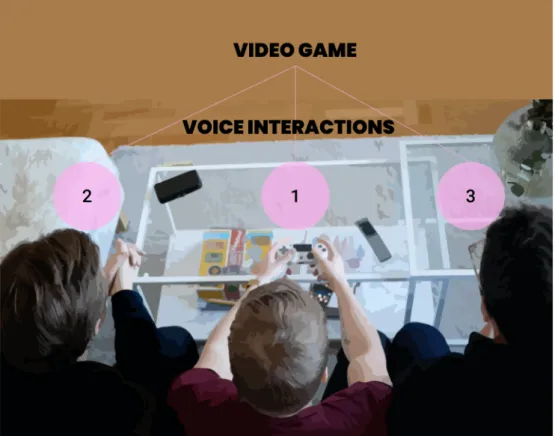

4.5.1 Execution

Two of the participants also present in the observations phase was invited to this bodystorming session. Six different voice/sound commands were pre-written for the session, all with focus on moving game menu-interactions to one single voice command. The written voice interactions had two emphases, both based on previous mentioned research and ideation methods. The first set of interactions were constructed into sentences asking the game to execute a specific action whilst the second set of interactions focused on making sounds to interact with the game. The second set of interactions still had the same focus on having the game execute a certain action in the game, but using sound allowed me to explore what sounds they felt fitting for a specific action. The process started with having the person that was playing the game speak the first command with the other participants following with iterated versions of it (see Figure [8]). The reason for having people iterate quickly was to give them no chance of providing a well-formulated and constructed response, thus giving me the chance to identify how they subconsciously frame the voice interaction.

Figure 8: Illustration showing order of interactions and its end goal

4.5.2 Findings

The bodystorming session showed that the participants shortened the sentences for each iteration and used a conversational approach to the interactions, similar to the findings of the observations. They also tended to change the voice commands from being a descriptive sentence into a command focusing on goal-oriented tasks. Instead of e.g. expressing exactly what mission they wanted to navigate to, they focused on the distance to the mission, not what the mission contained. Even though only one of the participants were playing the game at the time, using voice as an interaction method whilst focusing on a main task showed great potential. None of the participants showed any signs of losing focus on the game, and the voice interactions were spoken without any loss in focus on main activity.

4.6 “Wizard of Oz” - Prototyping

The findings from the research and ideation session led to the design of three Wizard of Oz-prototypes, all exploring different ways to interact with the in-game map without having to use controller input. The in-in-game map showed to be the main element of the game that led to most frustration and interruptions when gaming. To see how to best implement voice interactions to reduce in-game interruption, following considerations were made when creating the prototypes.

Exploring different input approaches to using voice when interacting with the game has shown to be of importance during the research and is therefore experimented with when building the prototypes. It has also been shown that to create a prototype exploring new functionalities, the user has to know

when and how to use it, thus focusing on adding some kind of signifier to the

prototype. Lastly, the prototypes explored different approaches to feedback from the game system to the user.

Prototype 1 and Prototype 2 was designed simultaneously in order to explore

the different approaches of voice user interface design.

The first prototype being more focused on providing auditory feedback, not adding any visual layer on top of the game but rather a providing a set of pre-written voice commands to the user.

The second prototype however, removed the pre-written commands and focused more on exploring how a context-based signifier would affect the voice interactions. The second prototype also removed auditory feedback to the commands and replaced it with updated visuals inside the game.

Prototype 3 is presented as the final prototype and is an iterated version

based on the insights gathered in prototype 1 and prototype 2.

4.6.1 Prototype 1

The first out of three prototypes explored auditory feedback when interacting with the game through voice. The prototype relied on a synergy of artefacts seemingly working together to create value for the users. The tool used for playback of voice was Adobe XD, a prototyping tool from Adobe Inc. (Adobe Inc. 2019) together with commands written on post-it-notes. When the users initiated a command, the software was used to decide what they would hear after the voice input. I was acting as the system and decided what audio to play for the users, making the margin of error in the voice interaction entirely decided by me. The commands available for the users was written in a conversational style and focused on questions surrounding waypoints to commonly visited areas in the game and they were limited to a pre-set of three voice commands. The reasoning for limiting the users to a set of commands were based on previous insights were the users felt an insecurity when giving total freedom of their interactions with the game. All three commands had its matching set of answers played back to them through a separate speaker placed next to the television, having the speaker connected to a computer with Adobe XD running on it. All voice interactions had an option for follow-up questions, but these were not communicated to the users as being available. The idea was to see if they wanted to add to previous voice interactions or if they felt like a single command was sufficient enough to cover their needs.

No visual signifier was added to the game environment. The users was free to issue any given command and received no indicator telling them voice interactions were available.

A total of three participants attended the user tests. During the user testing of the prototype, the participant was placed in the living room next to the television whilst I was in another room controlling the auditory output based on their voice interactions (see Figure [9] ).

Figure 9: Back-end view of one of three commands of the prototype.

The participants did not know the prototype was directly controlled by me which might have affected the way of communicating with the game. Voices were raised when giving voice interactions, maybe as a way of making sure that the game would hear them. Figure [10] shows the flow of the entire interaction, from the participant telling a command, to the auditory voice response.

What became evident during the testing of the prototype was that using voice as a way to set waypoints to new missions or areas in the game was frequently used compared to other actions available. The participant did not use any follow-up questions and did not express the need of doing so when talking to them after the usability testing. The participant was given the freedom to use voice to interact with the game at any time. This allowed for me to see in what context they were used and if a common denominator could be found. Findings showed that voice interactions was mainly used right before transportation or during it, never during a mission. Using voice as a way to place waypoints in the game was well received but the voice feedback was not. The participant expressed that the voice added a discrepancy between the player and the game world.

4.6.2 Prototype 2

The second prototype removed pre-written commands and added a signifier in the bottom left corner as a way of communicating that voice interactions is available during certain contexts in the game (see Figure [11]).

Figure 11: Icon appearing in the bottom left indicating that voice interactions are available A waypoint also appeared on the mini-map after the voice command was initiated as a way to explore visual feedback. Since I was not able to do any changes inside the game itself, two pre-recorded videos were stacked on top of each other with only one being displayed to the player. The two identical scenarios was recorded inside the game, one with a waypoint and the other without one. The visual signifier together with minor visual elements was added in the videos using Adobe Premier Pro (Adobe Inc. 2019). As with Prototype 1, I was acting as the system, switching the view for the participant (see Figure [12]).

Figure 12: Illustration showing video output for the player and researcher controlling video output by interacting with video software.

Since this prototype relied on pre-recorded material, there was no way for the player to directly interact with the game. The participants were briefed about the scenario and pretended to play the game as one would when travelling from one point to another.

When they issued a voice command, the videos instantly switch places as a way to simulate that a change had been made inside the game. The player was free to express whatever voice commands they wanted and was not forced to use a pre-determined set of commands.

Having a visual signifier appear based on the in-game context, showed potential in communicating the possibilities of using voice interactions to interact with the map and reduce time spent in menus. The majority of the interactions was related to functions that could be found in the map of the game. However, giving the participant the freedom to express whatever they wanted created an insecurity when using voice interactions. The signifier also created some confusion since the position did not match the structure of the game. When playing the tutorial of the game, the player learns that new functions gets implemented a certain way and by introducing a new functionality where they did not expect it, lead to some confusion.

Another aspect that became apparent was that even though the player felt that the auditory vocal output of Prototype 1 was annoying, the use of sound as confirmation could improve the player’s perception of something happening. Adding a change in the visuals of the game without any kind of animation or sound as confirmation left the participants partly insecure about what happened.

Before developing the final prototype, annotation of game elements were made to understand where to place information to afford a certain behaviour from the user (see Figure [13]). If the purpose of a design element is to

communicate new functionalities to the player, it should be placed where the player expects such information to appear.

Figure 13: Annotation sketch of the in-game player view

4.6.3 Final prototype

By extracting features from the previously developed prototypes, a final one was designed. This prototype explored a compressed conversational style of voice user interfaces as input, with auditory and visual confirmations. It was designed with a combination of edited wireframes together with edited videos of gameplay from Red Dead Redemption 2. The videos were stacked on top of each other and presented based on the voice interactions from the user. The voice user interface was designed with a set of pre-written sentences with the possibility to change only one word in the sentence. This would allow the player to focus on the end-goal of the voice command rather than trying to remember how to speak it. Text was also added to indicate that voice interactions is a feature of the game. The text “voice interactions available” was a way to make the user understand that it’s a mechanic of the game and not only something available at that specific time. The visual signifier was used once again but this time with the text next to it in order for the user to connect it to the possibilities of using voice interactions (see Figure [13]).

Figure 13: Pre-written voice interaction with exchangeable destination

The goal was to introduce a VUI that was scaled down in terms of the amount of words and instead allowing for flexibility with one exchangeable highlighted word. The vocal feedback from Prototype 1 was replaced with a

short sound effect indicating that the game understood the command and acted on it. An animation was added to the mini-map of the game and triggered together with the audio. Figure [14] below shows the flow of the interaction which contains the following steps: (1) Player whistles for the horse, (2) game identifies whistle as a context trigger and provides the player with a signifier with information about voice interactions, (3) the player interacts with the game by speaking the given phrase and gets a confirmation through visuals and sound, and (4) waypoint appears on the mini-map.

Figure 14: Flow of interaction for setting a waypoint

During the usability testing the participants were informed about the context of the upcoming gameplay section but not given any information about the possibility to interact with the game through voice. This was a conscious decision made to test if such a feature could be presented and well understood without the knowledge of previous research and design work.

The voice interactions were used to a greater degree compared to previous prototypes and a variety of voice commands was used. By adding a short animation to the mini-map together with a short sound effect, it replaced the need of having a voice confirming the action. Context-based triggers together with adding text as a signifier showed to be an appreciated combination when presenting new functionality to the user. This removed the uncertainty they felt when letting them say whatever they wanted, but enough flexibility to make it a valuable feature to smoothen the transition between main activity and the in-game map, reducing some of the in-game interruptions. This prototype allowed for a better use of voice interactions as a peripheral

interaction compared to previous iterations due to its straight forward

approach in delivering a VUI with limited amount of words that can be quickly read and acted upon. By having the new visual information appear where they expected it from previous experiences with the game, its role became more apparent for the player.

As mentioned when analysing the findings of the observations, the users had to use a multiple set of interactions to place a waypoint in the game. But voice interactions has proven to provide a condensed more goal-oriented way of using the in-game map. There is no need to tell the game each step it has to take to reach the end-goal, but rather communicate the goal of the interactions (see Figure [15]).

Figure 15: The journey of voice interactions to set an in-game waypoint

5 Discussion

This thesis aimed to explore and find ways how to design a voice user interface to reduce in-game interruptions for open world video games and the user tests showed that using voice as a way to reduce in-game interruptions could work when designed with certain aspects in mind. The discussion will highlight these insights and provide arguments for what needs to be taken into account when designing voice user interfaces to reduce in-game interruption in open world video games.

The user tests showed that voice interactions can be used to reduce in-game interruptions but that it has to move into the peripheral attention to do so. When the information presented required users to allocate more mental resources to the voice commands than the gameplay itself it added an interruption in their gameplay. It was not until later parts of the user testing when the participants became more used to voice interactions when it became more part of the gameplay rather than another layer added on top of it. Designing for peripheral interactions has shown to be personal and it can only become peripheral once the user get used to the voice interactions. Bakker (2016) also discusses this and claims that interactive systems may shift to the periphery of attention for some users, while this does not happen as easily for others. But what this thesis work has shown is that voice interactions can become a peripheral interaction once the player have gotten

used to using voice as an input method. What it might require from the user is that they unlearn old habits to make place for new functionality. Even though voice interactions initially might not act as a peripheral action, it could always become one (Bakker, 2016).

With the current state of how in-game maps work today, the main focus is on the UI. No matter how well one know the UI, it can never be pushed to the peripheral of ones attention since it will always demand the player’s main focus. The user tests of this project has shown that the level of experience of players using voice interactions needs to be taken into account when designing voice user interfaces but that everyone can learn to use it successfully. This indicates that the use of voice user interfaces in open world video games can help reduce in-game interruptions when placing the information for how to use them, becomes a peripheral activity.

Thinking is usually not seen as an activity one might refer to as an interruption but when exploring voice interaction in an open world video game environment, it became one. Users had to think before issuing a voice command but when the activity was placed into the periphery of their attention, it did not appear to be a central cognitive activity. This resembles the way owners of home voice assistants expressed that the use of voice interactions worked best together with another main activity. This was also brought up by Pearl (2016) as being one of the benefits of having a VUI providing a hands-free experience that allows users to engage in other activities whilst interacting with the device.

The context-based approach showed to be necessary when designing for voice interactions in video games. It showed that if the VUI does not take the context into account, it was harder for the player to understand what to act upon. Similar to how research showed that users of home voice assistants interact with their devices. Setting a timer when cooking, or add a reminder when their out of milk act as a peripheral interaction that adds additional value to their main activity. The results of the user testing showed that the context in which voice interactions is used, needs to be taken into account when designing to make the transitioning between the main activity and interacting with the map a coherent experience.

The work by Carter et al. (2015) argues that voice interactions in games need to take the game character in account for a voice user interface to be relevant and that voice interactions has to correlate to something the character would say or do in the game. But this thesis has identified a need for gamers to use voice similar to how users of home voice assistants interact with their product, to productivity related tasks. This argue for a future in which voice interactions in HCI are used as a form of relieving users of non-prioritised productivity related tasks rather than only voice as a form of personal communication.

Having voice interactions locked to a set of commands with limited modularity allowed for the users more easily remember the command and focus on having one word that could be changed. This possibility lead users to remember the command to a greater extent in comparison to having entire sequences swapped.

5.1 Self-evaluation

Presented as a part of the results from the prototypes was the fact that users could not play the game as they usually did due to the lack of interactivity in two of the prototypes. Building the prototypes on top of the original game with high fidelity visuals made the users initially believe that they were going to play the game with implemented voice elements. This lead to me having to explain that they were limited to the interactions of using voice.

Usability tests were only made with experienced gamers which might have affected the data in ways that better cater for a certain group of people. Even though this allowed for more specific questions in how to implement voice as a way to reduce in-game interruptions, questions regarding the feeling of using voice as an interaction method might have been different. Users not used to playing video games could possibly have provided med with insights related to the role of voice in video games more than experienced gamers. An experienced gamer have more knowledge about in-game functions but that might have blinded them by the value of removing boring processes inside the game and might have already been positive towards the concept. A non-experienced gamer might have been more critical towards it due to the lack of previous experiences with in-game maps. Furthermore, testing the final prototype with a larger population would be preferred to confirm that voice interactions is a credible way to reduce in-game interruptions.

6 Conclusion

This project explored how voice user interfaces could be designed to reduce in-game interruptions in open world video games. The design process was carried out with a human-centered design approach containing two major phases, the research phase and the design phase.

The research phase contained quantitative and qualitative user research methods such as semi-structured interviews, observations and literature studies. Based on the research phase, two design opportunities were identified and how-might-we questions were constructed. The two main HMW-questions were; “How might we make transitioning between the

“How might we communicate the possibilities of a VUI in a video game

environment?”.

After a set of ideation sessions with selected participants, two prototypes were designed and user tested. The insights from these two prototypes lead to the design of a final prototype made to explore how a design with the purpose of reducing in-game interruptions could be designed. The final prototype made it clear that there is three qualities one might need to think about when designing a voice user interface to reduce in-game interruptions.

Voice as peripheral interaction shows that in order for a voice user interface

to be implemented next to the activity of gaming, it needs to act in the periphery of one’s attention.

Context-based triggers provides an understanding of how voice interactions

are relevant to the main gaming activity. If the purpose of a design element is to communicate new functionalities to the player, it needs to be placed in a context where the player expects such information.

Compressed & modular voice interactions showed to be most efficient when

communicating the possibilities of a VUI in the video game environment. Having a phrase that is always expressed together with modular parts that can be changed.

In addition to the previously mentioned qualities, this study has shown two emerging themes of thinking to when designing voice interactions in a video game environment.

Using voice as a productivity tool has shown to be the preferred way of using voice when designing for voice in an open world environment.

Thinking as an interruption has to be another element to think about when

designing for voice interactions with the purpose of reducing interruptions or streamlining gameplay.

The results of this study have shown how certain ways of thinking about voice interactions together with a set of design qualities can help when designing voice user interfaces with the intention of reducing in-game interruptions.

6.1.1 Future research

The next step in moving forward with designing voice user interfaces might be to explore whether or not this is applicable to other genres of games and how one would implement voice in those scenarios. To explore if the value of using voice shows similar potential when applied to games that does not use an in-game user interface as a way for the player to navigate through the game. Using voice as a productivity tool is one of the more interesting approaches presented in this thesis and could be applied and tested in different parts of society. Questioning what a productivity related task within a certain context is, and how a voice user interface be designed to streamline such an experience.